#chatham square

Text

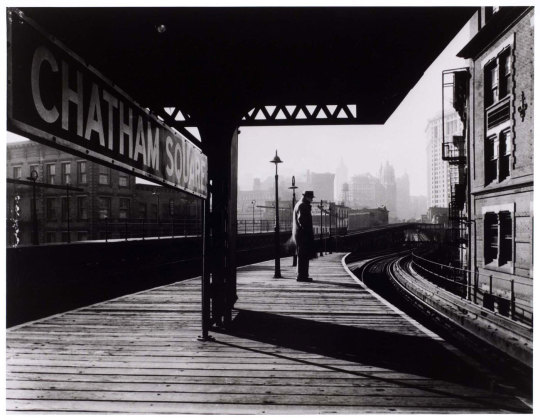

Arnold Eagle - Chatham Square Platform, New York

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chatham Square Platform, New York City. c. 1939

Photo: Arnold Eagle

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

New York Elevated Railroad

Circa 1949: A train on the Third Avenue 'El', or elevated railway, in New York City, on its way to Wall Street, past fire-escapes.

Looking south from Franklin Square station (under Brooklyn Bridge) The northbound train coming from South Ferry could be 2nd or 3rd Ave EL, local or express, they all used the same 2 tracks south of Chatham Square.

Why did they take down the Third Avenue El?

Pressure to scrap the El increased because of the postwar construction boom in the city, with sections of the Third Avenue line running from South Ferry to Chatham Square closed beginning in 1950. The main part of the line — from Chatham Square to East 149th Street in The Bronx ceased operations on May 12, 1955.

Why were elevated trains removed from NYC?

Partly because of the politically untouchable nickel fare, the competing transit systems struggled financially even in the best of times. Changing economics and evolving public needs motivated policymakers to remove elevated lines and replace them with subways, which continued to burgeon.

Read also - View of the Chrysler Building

#elevated railroad#wall street#third avenue#brooklyn#chatham square#john street#New York City#new york#newyork#New-York#nyc#ny#urban#city#visit-new-york.tumblr.com

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking up #East_Broadway from Chatham Square, #Manhattan.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

homelinearch.com

This free-standing Greek Revival Townhouse, typical to Savannah was built in 1859 for William H. Bradley on Chatham Square.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chatham Square Platform - New York City - 1939

Photo de Arnold Eagle

#et pendant ce temps-là#photographie#photography#photographie de rue#street photography#métro#subway#chatham square#arnold eagle#new york city#états-unis#USA#1939

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jon Gibson, Visitations, LP 12, Chatham Square Productions, 1973 [then New Tone Records, 1996; Superior Viaduct, 2015] [Saint-Martin Bookshop, Bruselles-Brussel]

#graphic design#typography#art#music#music album#vinyl#cover#back cover#jon gibson#chatham square productions#new tone records#superior viaduct#1970s#1990s#2010s

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

New York Public Library Archives, The New York Public Library. "Chatham Square Branch, New York Public Library (old rented building)" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1902. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-e53f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

#New York Public Library Archives#childhood studies#indoor plants#plantsinlibraries#books & plants#childrenslibraries#plants#archives#dissertation#phd stuff#interiors#built environment

0 notes

Text

National Rainbow Week of Action in Canada

In this post I have compiled all the information I could find regarding upcoming events for the Rainbow Week of Action. There are two online events, and dozens on in-person events across the country.

"Within the Rainbow Week of Action, we are pushing governments and elected officials at every level to take action for Rainbow Equality and address rising anti-2SLGBTQIA+ hate. As such, we have identified calls to action for every level of government. These calls to action can be reviewed here."

Event list below:

Events are listed in date order, provinces in general west-to-east order. I have included as much detail as possible, please reference the links at the bottom of the post. At this time, there are no events in N.W.T. and Nova Scotia. Last updated: May 14th, 9:53pm PDT. Please note that I am not officially affiliated with / an organizer of these events, I have simply compiled all the dates to share on tumblr. Original post content.

B.C. EVENTS:

15th: Fernie; Fernie Seniors Drop-In Centre, 572 3rd Avenue, 6:00PM. (Letter writing and Potluck)

17th: Vancouver; šxʷƛ̓ənəq Xwtl'e7énḵ Square - Vancouver Art Gallery North Plaza, 750 Hornby St, 5:30PM. (Rally)

19th, Sunday: Abbotsford; Jubilee Park, 5:00PM. (Rally)

ALBERTA EVENTS:

15th: Lethbridge; McKillop United Church, 2329 15th Ave S, 12:00-1:00PM (letter writing)

17th, Friday: Calgary; Central Memorial Park, 1221 2 St SW, 5:30PM. (Rally)

17th: Edmonton; Wilbert McIntyre Park, 8331 104 St NW, 6:00PM. (Rally)

SASKATCHEWAN EVENTS:

17th: Saskatoon; Vimy Memorial Park, 500 Spadina Crescent E, 5:30PM. (Rally)

17th: Regina; Legislative Grounds, 2405 Legislative Dr, 6:30PM. (Rally)

May 18th: Saskatoon; Grovenor Park United Church, 407 Cumberland Ave S, 6:00PM. (Art event)

MANITOBA EVENTS:

16th: Carman; Paul's Place, 20 1 Ave SW, 7:00-9:00PM. (Letter writing)

19th: Winnipeg; Manitoba Legislature, 450 Broadway, 12:00PM. (Rally)

ONTARIO EVENTS:

15th: Barrie; UPlift Black, 12 Dunlop St E, 6:00-7:30PM. (Letter writing)

15th: Chatham; CK Gay Pride Association, 48 Centre St, 5:00-6:30PM. (Letter writing)

15th: Peterborough; Trinity Community Centre, 360 Reid St, 12:00-3:00PM. (Letter writing)

16th: Midland; Midland Public Library, 4:30-7:30PM. (Letter writing and pizza)

16th: Ottawa; Impact Hub, 123 Slater Street, 2:00PM. (Letter writing)

16th: Toronto; Barbara Hall Park, 519 Church St, 11:30AM. (Rally)

17th, Friday: Barrie; City Hall, 70 Collier St, 6:00PM. (Rally)

17th: Cornwall; 167 Pitt St, 5:30PM. (Rally)

17th: Essex; St. Paul's Anglican Church, 92 St. Paul St, 6:00-8:00PM. (Letter writing and pizza)

17th: Hamilton; City Hall, 71 Main St W, 6:00PM. (Rally)

17th: Kitchener; City Hall, 200 King St W, 6:00PM. (Rally)

17th: London; City Hall, 300 Dufferin Ave, 6:00PM. (Rally)

17th: Sarnia; City Hall, 255 Christina St N, 1:00PM. (Rally)

17th: Sault Ste Marie; City Hall, 99 Foster Dr, 11:30AM. (Rally)

17th: Ottawa; Confederation Park, Elgin St, 5:30PM. (Rally)

22nd: Renfrew; 161 Raglan St. South, 7:00PM. (Letter writing, fashion and makeup event, and pizza)

QUEBEC EVENTS:

May 15th: Lachute; CDC Lachute, 57, rue Harriet, 12:30PM. (Letter writing event)

NEW BRUNSWICK EVENTS:

17th: Woodstock; Citizen's Square, Chapel St, Next to the L.P. Fisher Public Library, 12:00-1:00PM. (rally)

17th: Saint John; City Hall, 15 Market Square, 12:30PM. (Rally, flag raising)

18th, Saturday: Fredericton; Legislative Grounds, 706 Queen Street, 1:00PM. (Rally)

NOVA SCOTIA EVENTS:

May 17th: Middleton; NSCC AVC RM 121, 6:30-8:30PM (letter writing and pizza)

P.E.I. EVENTS:

May 15th: Charlottetown; Peers Alliance Office, 250B Queen Street, 6:00-8:00PM. (Adult drop-in)

May 16th: Charlottetown, Peers Alliance Office, 250B Queen Street, 6:00-7:00PM.

May 17th: Charlottetown; PEI Legislative Assembly, 165 Richmond St, 12:00PM. (Rally)

YUKON EVENTS:

16th: Whitehorse; The Cache, 4230 4 Ave, 2:00-7:00PM. (Letter writing)

NUNAVUT EVENTS:

May 16th, Thursday: Iqaluit; Four Corners, 922 Niaqunngusiariaq St, 5:00PM. (Letter writing)

Reference links:

About the Rainbow Week of Action.

Website letter writing events list (does not include all events)

General events website list (does not include all events)

Instagram general events image list

Instagram letter writing / pizza party image list

#rainbow week of action#lgbt#cdnpoli#lgbtq#canada#alberta#british columbia#saskatchewan#manitoba#new brunswick#newfoundland and labrador#yukon#nunavut#prince edward island#ontario#quebec#nova scotia

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock & Co Locations

Location, location, location. Are you like me and not a native Londoner? Are you also like me wondering how to visualize a place or, perhaps more importantly, how long does it take to get from 221B to the various locations and how much they're spending on tube fare?

Well then look no further! This is my masterpost with links to each location described in detail in each post made on those locations. Each post gives a bit about how far from 221B it's located (depending on travel method), how much it likely cost them to get there, photos of the location, and a bit of the location's history.

Every time we get a new locale I'll add a post and link it here. :) Lmk if I miss any and I'll add them. If you see a location and it has no link then either the link broke or I haven't made the post yet, but logged the location.

Cheers!

The Criterion Bar

221B Baker Street

Brixton

The Volunteer Pub & Restaurant

Regent's Park

Hampstead

Thor Bridge (Upney Ln)

Walthamstow (Morgue)

King George's Hospital

Barking/North Barking

Fortnum & Mason

Paddington Station

Hilton Green/Chatham

Berlin (John's Vacay Spot with The Boys)

Heathrow Airport

Hotel Cosmopolitan

Bailey's Street

Shoreditch

King's Road

Chelsey

44 Cross St., Croydon

Chiswick Flyover

The Fox (the swinger's pub)

Hanwell/Ealing/West London

Islington Tunnel

Eltham

Blackheath Common

"GAIL'S Bakery"

The Strand

'Saxe-Coburg Square'

Pinewood Studios

Embankment

Charing Cross

Opera House (?)

Barking Station

Walthamstow

Waterloo Bridge

Bank of England Museum

Camden Town

Living Room Club Cafe

'Gloria Scott' (Oil Rigs)

Ramack/Kosovo

St Dunstan

Little Venice

Satalfields

Brick Lane

Neal's Yard

South Kensington (Ice Rink)

#sherlock & co#sherlock and co#sherlock & co locations#goalhanger podcasts#goalhanger#meta#I think#masterlist#uh just realized there's probably spoilers in having this list lol#so consider yourself warned#sh&co spoilers

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Judith Miller

Last fall, Egypt was on the brink of economic collapse. A decade of debt-fueled spending on a pharaonic-scale had emptied its Central Bank coffers. By February, Cairo’s public debt was 89% of its gross domestic product. External debt had soared to 46% of GDP. The pound, its currency, was one of the world’s worst performing. Unable to import supplies and repatriate profits, foreign companies were leaving, or threatening to leave Egypt in droves. Annual inflation was over 35%, and double that for some food staples. Egypt seemed on the verge of a sovereign default—its first ever.

Then came Oct. 7.

Officials, businessmen, and financial analysts say that however horrific the war has been for Israelis and for Palestinians in Gaza, Oct. 7 has helped save Egypt from economic ruin and growing political unrest. To be sure, Egypt is paying heavily for the ongoing Israel-Hamas war on its border. Its three main sources of revenue—hard currency from the Suez Canal, tourism, and remittances from Egyptian workers abroad—have plummeted by between 30% and 40%. But without Hamas’ horrific massacre, which killed 1,200 people and took another 240 hostage, and Israel’s much criticized retaliation in Gaza, Egypt would probably not have gotten the international financial lifeline that has rescued it yet again from economic ruin, just in time.

��Just after the attack, the government began strategizing, successfully it’s turned out, about how to use the crisis to secure a bailout,” said Ahmed Aboudouh, an Egyptian expert at Chatham House, a London-based think tank. “Oct. 7 helped save Egypt’s economy, at least temporarily.”

Last February, the Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADQ), Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, unveiled plans to develop a city by the sea on part of the 65-square-mile peninsula of Ras el-Hekma, one of the few undeveloped areas on the Mediterranean coast, part of a sale worth $35 billion in investment and debt relief, the largest foreign direct investment deal in Egyptian history. Egypt will retain a 35% stake in the project. Since Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed al-Nahyan, the chairman of ADQ, is Emirati President Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan’s brother and the UAE’s national security adviser, the Ras el-Hekma purchase was far more than a financial transaction. It was part of an Egyptian bailout.

Egyptians bristle at the loss of their nation’s diplomatic clout. By reviving its regional profile, Oct. 7 has bestowed another gift on Egypt.

Then in March, Cairo secured a critical $8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, with strong American support. The IMF infusion, in turn, opened other foreign faucets. The European Union promptly agreed to provide another $8 billion in grants and loans, ostensibly to help Egypt’s economy, but in reality, to assure Egypt’s help in preventing Arab and African migrants from reaching European shores. In total, the IMF, Europe, and the Gulf have now poured well over $50 billion of foreign currency into Egypt’s cash-strapped coffers. “The U.S., Europe, and the Gulf clearly agreed that the Sissi government could not be permitted to fail,” said Steven Cook, an expert on Egypt at the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations. “Geopolitics has taken over.”

Only months before, the IMF had not completed the review of Egypt’s loan agreement approved in December 2022, thereby withholding a tranche of the $3 billion rescue package, as the government had failed to deliver on agreed benchmarks. While the fund attributed its about-face in March to the increasing damage being done to Egypt’s economy by the Israel-Hamas war—or what it euphemistically called a “more challenging external environment”—absent American pressure on the fund and on Egypt to agree belatedly to financial reforms it had previously rejected, the IMF loan and even the Ras el-Hekma deal would not have gone through. Since Washington is the fund’s largest shareholder with a 16.5% stake, it holds sway over its key lending decisions.

The Biden administration, too, was obviously unwilling to risk the economic collapse and political destabilization of the Arab Middle East’s largest country and the first Arab state to make peace with neighboring Israel in the midst of one of the region’s deadliest wars in modern history and with other conflicts around it still raging—especially since Egyptian mediation with Hamas was crucial to White House policy. “Egypt has proven, yet again,” said Aboudouh, “that it is, as its elite believes, too big to fail.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The first public reference to Klan activity in Canada appeared in the Montreal Daily Star, which announced the organization of a branch of ‘the famous Ku Klux Klan’ in Montreal in 1921, and reported that ‘a band of masked, hooded and silent men’ had gathered in the northwest part of the city behind the Mountain. In 1921, the Klan set up an office in West Vancouver, and British Columbia newspapers began to publish solicitations for Klan membership. KKK crosses were sighted burning across New Brunswick: in Fredericton, Saint John, Marysville, York, Carleton, Sunbury, Kings, Woodstock, and Albert. James S. Lord, the sitting member of the New Brunswick legislature for Charlotte County, becamea highly publicized convert. Later the Klan would infiltrate Nova Scotia, burning ‘fiery crosses’ on the lawn of the Mount Saint Vincent Convent, and in front of St John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church at Melville Cove near Halifax’s North-West Arm.

Reports of Klan activities surfaced in Ontario as well, where white American organizer W.L. Higgitt began a tour in Toronto in 1923. In the summer of 1924, a huge Klan gathering took place in a large wooded area near Dorchester. Cross-burning, designed to intimidate the village’s few Black residents, was carried out with great pomp and ceremony. In Hamilton in 1924, police arrested a white American named Almond Charles Monteith in the act of administering initiation rites to two would-be Klanswomen. Monteith was later charged with carrying a loaded revolver. Along with the revolver, police confiscated a list of thirty-two new members (‘some of them prominent citizens’), correspondence regarding thirty-six white robes and hoods, and a $200 invoice for expenses for ‘two fiery crosses.’ Monteith denied any involvement in recent cross-burnings on Hamilton Mountain, and was convicted on the weapons charge. The day after Monteith’s conviction, the arresting officer received a letter bearing a terse message: ‘Beware. Your days are numbered. KKK.’ Monteith’s conviction did nothing to put a crimp in the Klan’s membership drive. Between four hundred and five hundred members paraded through Hamilton in a KKK demonstration in the fall of 1929.

By June 1925 there were estimates of eight thousand Klan members in Toronto; headquarters were installed in Toronto’s Excelsior Life Building. The summer of 1925 witnessed hundreds of crosses burned across Chatham, Dresden, Wallaceburg, Woodstock, St Thomas, Ingersoll, London, and Dorchester. A group of hooded Klansmen tried to proceed en masse through the chapel of a London church to show their appreciation of the anti-Catholic address that had been delivered to the congregation. At a rally of more than two hundred people at Federal Square in London, J.H. Hawkins, claiming to be the Klan’s ‘Imperial Klailiff,’ proclaimed:

‘We are a white man’s organization and we do not admit Jews and colored people to our ranks. [ … ] God did not intend to create any new race by the mingling of white and colored blood, and so we do not accept the colored races.’

More than one thousand showed up at a similar rally in Woodstock.

At what was billed as the ‘first open-air ceremony of the Klan’ in Canada, two hundred new members were initiated at the Dorchester Fairgrounds in October 1925, in front of more than one thousand avid participants. The ‘first Canadian Ku Klux burial’ took place in London the next year, as robed and hooded Klansmen, swords at their sides and fiery crosses at hand, showed up to perform a ritual at the graveside of one of the Drumbo Klan. Ontario chapters sprang up in Niagara Falls, Barrie, Sault Ste Marie, Belleville, Kingston, and Ottawa. New headquarters appeared in a Vancouver mansion in 1925, and local chapters called ‘Klaverns’ sprang into existence in New Westminster, Victoria, Nanaimo, Ladysmith, and Duncan. Klan bonfires lit up Kitsilano Point. By 1928, the Vancouver Klan was soliciting signatures for a petition to demand that Asian Canadians be banned from employment on government steamships. A ‘Great Konklave’ was held in June 1927 in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, where an estimated ten thousand people stood by as hooded Klansmen burned a sixty-foot cross and lectured to them on the risks of racial intermarriage. Demanding an immediate ban on marriage between white women and ‘Negroes, Chinese or Japanese,’ the Klan proclaimed: ‘one flag, one language, one race, one religion, race purity and moral rectitude.’ The Saskatchewan group would later disaffiliate from Eastern Canada, to create an entirely separate western wing that was credited with signing up 25,000 members. In Alberta, ‘Klaverns’ came into existence in Hanna, Stettler, Camrose, Forestburg, Jarrow, Erskine, Milo, Vulcan, Wetaskiwin, Red Deer, Ponoka, Irma, and Rosebud. Alberta membership peaked between 5,000 and 7,000, but the Klan newspaper, The Liberator, produced out of Edmonton, purported to maintain a circulation of 250,000.

Nor were the activities of the Klan restricted to rallies and cross-burnings. In 1922, the Klan was linked to a rash of torchings that wreaked more than $100,000 damage upon three Roman Catholic institutions: the Quebec Cathedral, the rest-house of the Sulpician order at Oka, Quebec, and the junior seminary of the Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament in Terrebonne. In 1922, threatening letters signed by the Klan were delivered to St Boniface College in Winnipeg. Before the year was out, the college burned to the ground, causing the death of ten students. In 1923, similar letters, signed by the Klan, were sent to local police and Roman Catholic authorities in Calgary.

In Thorold, Ontario, the KKK intervened in a local murder investigation in 1922, issuing a warning to the town mayor to arrest an Italian man suspected of the crime by a specified date or face the fury of the Klan. The letter continued: ’The clansmen of the Fiery Cross will take the initiative in the Thorold Italian section. Eighteen hundred armed men of the Scarlet Division are now secretly scouring this district and await the word to exterminate these rats.’ In 1922, the Mother Superior of a Roman Catholic orphanage in Fort William received a letter signed ‘K.K.K.’ threatening to ‘burn the orphanage.’ The mayor of Ottawa was mailed a vitriolic letter, demanding he pay more attention ‘to Protestant taxpayers’ or the Klan would take ‘concerted action.’ Two Klansmen stole and destroyed religious paraphernalia from the tabernacle of the St James Roman Catholic church near Sarnia. The Ancaster Klan attempted to intimidate the African Brotherhood of America from erecting a home for ‘colored children and aged colored folk.’

The Belleville Klan visited the office of the Belleville Intelligencer, demanding that the manager dismiss a Catholic printer employed by the paper. The Sault Ste Marie Klan launched a concerted campaign to force the big steel mills to fire their Italian workers. A rifle bullet was fired at George Devlin during a wedding reception in Sault Ste Marie, with a blazing cross left behind to claim responsibility for the act. In 1924, local Klansmen surrounded the Dorchester home of a white man believed to be married to a Black woman. Threats were made to burn a cross outside the house of a white Bryanstown resident reputed to be involved with a Black woman. In 1927, several crosses were burned on the lawn of a white family believed to be running a brothel in Sault Ste Marie. The family was forced to flee their home.

Klan activities were also responsible for the removal of a francophone Roman Catholic postmaster in Lafleche, Alberta. The Alberta Klan promoted boycotts of Catholic businesses. The Drumheller KKK, which boasted a membership embracing forty of the town’s most prominent businessmen and mine owners, burned a cross on the lawn of a local newspaper columnist after he wrote a satirical comment about the Klan. Alberta Klansmen used bullets and flaming crosses to try to intimidate members of the Mine Workers Union of Canada during their bitter labour dispute in the Crow’s Nest Pass. Lacombe Klansmen wrote to the editor of the Alberta Western Globe after he opposed the Klan, threatening ‘severe punishment including the burning of his house and business to the ground.’ The same group kidnapped, and tarred and feathered a local blacksmith.

Throughout these activities, white police and fire marshals stood by, often present at the incendiary meetings and cross-burnings, content to reassure themselves there was ‘no danger.’ Despite the widespread evidence of lawlessness, Klan authorities tended to claim official disengagement whenever there was property damage or personal injury. Eschewing responsibility, they insisted that their organization had nothing to do with such events. Remarkably, the authorities largely respected these assertions of innocence, concluding that, without definitive proof that would tie named Klan officials to specific threatening letters or violent deeds, nothing further could be ascertained. Apart from the arrest and conviction of Almond Charles Monteith for possessing an unauthorized revolver, the only Klan event that attracted legal attention was the dynamiting of St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Barrie, Ontario, in 1926.

On the evening of 10 June 1926, a stick of dynamite shattered the stained-glass windows and blasted a four-foot hole through the brick wall of Barrie’s St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church. Buffeted about by the explosion, Ku Klux Klan flyers were scattered throughout the street, strewn among the brick, glass, and wooden debris. Barrie was a major stronghold of Ku Klux Klan activity, and organizers had drawn a crowd of two thousand to watch hooded Klansmen conduct a ritual cross-burning on a hill outside of Barrie several weeks earlier. At that ceremony, thirty-year-old William Skelly, a shoemaker who had emigrated one year earlier from Ireland, swore fealty to the tenets of the Klan, to uphold Protestant Christianity and white supremacy. He was initiated as a member in good standing. It was Skelly whom the police arrested for the bombing days later.

Skelly voluntarily admitted his Klan membership to the police, and confessed that, the night before the bombing, Klan members met to discuss ‘a job to be pulled off.’ There was a drawing of lots, and when Skelly drew the ‘Fiery Cross,’ he realized he was the designated man. Skelly claimed that he was intimidated by fellow Klansmen, who ‘made [him] drunk with dandelion wine and alcohol,’ and forced him to carry out the deed under threat of bodily harm. In fact, he told the police, he had joined the Klan in the first place only because he ‘had had considerable difficulty in securing steady work,’ and was told that, if he joined, the Klan ‘would look after him,’ finding him employment. Skelly also implicated two other Barrie Klan officials, Klan ‘Kleagle’ William Butler and Klan Secretary Clare Lee. Criminal charges of causing a dangerous explosion, attempting to destroy property with explosives, and possession of explosives were laid against all three white Klansmen.

This time the Ontario attorney general’s office issued an official statement that ‘no group can take into its own hands the administration of the law.’ The white deputy attorney general, Edward J. Bayly, became involved personally when he made arrangements for a leading white Toronto barrister, Peter White, KC, to prosecute the trio on behalf of the Crown. Skelly, Butler, and Lee were all found guilty at a jury trial in October, and sentenced to five, four, and three years, respectively. Officials from the Toronto headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan denied all responsibility, claiming throughout that Skelly ‘acted on his own initiative,’ despite all the evidence to the contrary."

- Constance Backhouse, Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999. pg. 183-193.

#canadian history#racism in canada#ku klux klan#racism#reign of terror#anglo canadians#antisemitism in canada#settler colonialism in canada#academic quote#reading 2024#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#thorold#belleville#sault ste. marie#vancouver#toronto#hamilton#drumheller#calgary#kingston ontario#montreal#barrie

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHATHAM SQUARE & MOTT STREET, NYC

(colorized, 1946) photo by Lee Sievan, Reddit

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1920 Chatham Square, New York City. From New York City History and Memories, FB.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buildings at #Chatham_Square, #Manhattan.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Miserables (2012) - Behind the scenes.

🎥 Video posted by Cinema Scope on YouTube

Les Misérables is a 2012 epic period musical film directed by Tom Hooper from a screenplay by William Nicholson, Alain Boublil, Claude-Michel Schönberg, and Herbert Kretzmer, based on the stage musical of the same name by Schönberg, Boublil, and Jean-Marc Natel, which in turn is based on the 1862 novel Les Misérables by Victor Hugo. The film stars an ensemble cast led by Hugh Jackman, Russell Crowe, Anne Hathaway, Eddie Redmayne, Amanda Seyfried, Helena Bonham Carter, and Sacha Baron Cohen.

Set in France during the early nineteenth century, the film tells the story of Jean Valjean who, while being hunted for decades by the ruthless policeman Javert after breaking parole, agrees to care for a factory worker's daughter. The story reaches a resolution against the background of the June Rebellion of 1832.

Following the release of the stage musical, a film adaptation was mired in development hell for over ten years, as the rights were passed on to several major studios, and various directors and actors were considered. In 2011, producer Cameron Mackintosh sold the film rights to Eric Fellner, who financed the film with Tim Bevan through their production company Working Title Films. In June 2011, production of the film officially began, with Hooper hired as director. The main characters were cast later that year. Principal photography began in March 2012 and ended in June. Filming took place on locations in Greenwich, London, Chatham, Winchester, Bath, and Portsmouth, England; in Gourdon, France; and on soundstages in Pinewood Studios.

Les Misérables premiered at the Odeon Luxe Leicester Square in London on 5 December 2012 and was released on 25 December in the United States and on 11 January 2013 in the United Kingdom, by Universal Pictures. The film received generally positive reviews from critics, with many praising the direction, production values, musical numbers, and ensemble cast, with Jackman, Hathaway, Redmayne, Seyfried, Aaron Tveit, and Samantha Barks being the most often singled out for praise. However, Crowe's performance as Javert and singing were met with criticism. It grossed over $442 million worldwide against a production budget of $61 million. The film was nominated for eight categories at the 85th Academy Awards, winning three, and received numerous other accolades. Since its release, it has been considered by many to be one of the most famous adaptations of the novel and one of the best musical films of the 2010s and the 21st century.

#my screenshots

#eddie redmayne#eddieredmayne#redmayne#les miserables#marius pontmercy#behind the scenes#december 2012

18 notes

·

View notes