#catuvellauni

Text

The legacy of the enigmatic Catuvellauni tribe shaped the very fabric of Iron Age Britain, from the heart of ancient Britannia to their clashes with the formidable Roman Empire.

At the core of Catuvellaunian society, chieftains commanded political and military authority, while druids played pivotal roles as spiritual leaders, shaping beliefs and rituals. Their mastery in craftsmanship, evident in intricate jewelry and pottery, not only served practical needs but also symbolized cultural identity and status within the tribe, leaving a timeless legacy of ancient British art.

The tales of the Catuvellauni tell of the Great "War Chiefs" whose stronghold near modern-day St. Albans, was a beacon of power and resilience against the tides of history. Their valorous defiance against the Roman invaders echoed through the annals of history. From the charismatic leadership of Cassivellaunus to the poignant plea of Caratacus, their story encapsulates the resilience and bravery of a tribe unwilling to yield to foreign domination.

Their heritage lives on as a testament to the indomitable spirit of a people who shaped the course of ancient British history.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Full-length Portrait of King Cassivellaunus (Cymbeline), King of the Catuvellauni, Ancient Briton & Chieftain commanding against Roman Emperor Julius Cesar.

Learn more / Daha fazlası

Cassivellaunus https://www.archaeologs.com/w/cassivellaunus/

#archaeologs#archaeological#dictionary#history#cassivellaunus#cymbeline#catuvellauni#ancient briton#britons#chieftain#roman empire#julius cesar#commander#illustration#art#united kingdom#arkeoloji#tarih

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Britain's Oldest Gold Coin Hoard Discovered

The oldest hoard of gold coins in Britain, dating back 2,173 years, was discovered by a metal detectorist.

The 12 Iron Age artifacts were discovered by Stephen Eldridge while scouring fields in Buckinghamshire.

They were built in 150 BC by a tribe in what is now Picardy, France, according to experts at the British Museum.

According to speculation, the coins were likely transferred to Britain in return for Celtic mercenaries who were sent to Gaul in western Europe to fight the Romans.

A hoard from this date is extremely uncommon, even though individual gold coins from this era have been discovered before.

The coins will now likely sell for £30,000 when they are put up for auction at London's Spink & Son.

In November 2019, Mr. Eldridge, 68, discovered the coins in the Buckinghamshire community of Ashley Green.

The Catuvellauni tribe first settled in the region about 150 BC, and during the ensuing century they grew to become the most dominant tribe in Britain.

Mr. Eldridge has put the coins up for auction with London-based coin specialists Spink after going through the treasure process.

The coins' roughly 75% gold content with an alloy of silver and copper was validated by scientific x-ray fluorescence analysis, indicating the economy in which Britain's first gold coinage were circulating.

The coins are now expected to sell for £30,000 when they go under the hammer at London auctioneers Spink & Son

Gregory Edmund, of Spink & Son, said: “Whilst individual gold coins of this period have been recorded across south east England, it is incredibly rare for a trove of this size or date to be uncovered. Contemporary local coinage was simply cast base metal issues called 'potins'. Whoever successfully imported this trove of gold coins would have undoubtedly wielded influence in the region.

They would have been exported, probably in exchange for mercenaries, equipment and hunting dogs to fight the Romans or other tribes in Belgium. Twenty or thirty years after they were deposited we started to get the first British coins in the same style. These coins were in the wealthiest part of the English kingdom. A hoard of this size and period is unprecedented in the archaeological record. There was one other hoard from this period of three coins found. These coins have been well used, it is very clear they are not fresh when they are put in the ground, but still retain remarkable details of a seldom-seen Iron Age art form.

It is often speculated that the portraiture of this coinage was deliberately androgynous despite being modelled on the classical male god Apollo. The feminine styling is probably a reflection of the political significance of women in Iron Age society, that enabled such historical figures as Cartimandua and Boudicca to rise to prominence and our now national folklore. It is incredibly satisfying to assist in the proper recording, academic analysis and now sale of these prestigious prehistoric relics.”

Following the coroner's inquest, the British Museum made the decision to disclaim the coins, which means they now belong to the finder.

The landowner will receive a portion of Mr. Eldridge's earnings.

#Britain's Oldest Gold Coin Hoard Discovered#Buckinghamshire#The Catuvellauni tribe#treasure#gold#gold coins#ancient gold coiins#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#metal detecting#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#iron age

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

NAME. Caradoc

AGE & BIRTH DATE. 2,013 & September 16th, 10 AD

GENDER & PRONOUNS. Male & He/Him

SPECIES. Demon ( Familiar )

OCCUPATION. Unemployed

FACE CLAIM. Douglas Booth

biography

( trigger warnings: death ) The harsh land of Ancient Britain was simply up for the taking when it came to the Romans. The Catuvellauni tribe had gained their own fame within Britain, the tribe of “war-chiefs” that pushed them to the top in the southeast of the island. This was the culture that Caradoc was born into. Friends of the druids who held mystical power, the tribes of Britain warred amongst themselves over the land that was provided to them, with the help of the druids that were stationed within each. Caradoc was born into freedom, in the midst of a Roman expansion. His brother was older, wiser – but brash and ambitious. Caradoc figured he must’ve got some cunning from his mother, a lowly woman who’d come to power beside his chieftain father.

History was set to repeat itself as Caradoc grew up among the green hills and forests of Britain, fighting and learning what it meant to be diplomatic. The Romans began expanding, targeting the druids amongst the tribes of Britain to wipe out as many as possible. There was always speak of rebirth when it came to druids, but Caradoc knew what that meant – it was an excuse to be absent. War was beginning to rage on, and Caradoc simply wished to survive. His personal life was nothing to be excited about – he’d flitted amongst men and women within the tribe, never settling and claiming that it was the wild spirit within him. He prayed to the Morrigan for strength, to the All Mother for peace – but nothing was ever answered.

In time, Caradoc learned to take what he wanted. That’s what their tribe had done for centuries, anyway, and the only person standing in his way was his brother. Caradoc didn’t have to do much, not in the sense that some would think. He won the hearts of the tribe; of the men and women warriors who took up arms against the Romans. If anyone were to be victorious, it would’ve been him. Revenge, he’d whisper amongst the people. He’d speak of how his brother was too hardheaded, that he would never lead them well. It’s what caused the mantle of leadership to pass to Caradoc, a ruler once more, loved and revered by the tribes that he’d convinced to join them in their cause against the Romans.

Even the death of his brother did not stop him. Caradoc could see his future – to gain enough glory that would get him to Rome, to leave the hills of Britain and the tribes that did not know gold, did not know power. But that didn’t mean he wouldn’t do everything he could to make his name known. The governor of Rome had it out for him, the barbarian that had fought back time and time again. During one of his last stands, Caradoc found himself in chains. His army was decimated, it would retreat into the hills of Britain, be taken over by Boudicca, but that’s where Caradoc’s story ended.

At least, it ended in Britain. He’d thrown away who he’d used to be when he was carted to Rome, as the governor paraded him around in chains. A barbarian, he’d claimed, but while he knew what would happen to those he’d convinced to continue fighting in his homeland, there was something else for Caradoc in Rome: infamy. His wit was something to be envied, where his biting words of how he’d die a martyr like Vercingetorix convinced the Roman governor to show mercy. His chains were broken, and he was set free. Caradoc, however, was far too eager to remain in the city of stone – any kin left behind forgotten about immediately. His greatest vice was to want – he lusted for fame, for little gleaming trinkets that he could hold in his hand and covet. Every now and then he wanted to love and be loved, in some strange twist of fate that always ended poorly because of something he did wrong.

His life was more or less whatever he wanted in Rome, where he got what he wanted and passed away among all his trinkets and fame. None of that was taken to the inferno with him, where the winds buffeted him at all times – storms cracked above him. It was a deep and meaningless place, muted and without color to someone who had always seen things in brilliant shades. It’s the want that drove Caradoc mad. There was nothing for those who pushed people for vengeance, who tainted hearts black like his own and sent them forward in a righteous quest when all Caradoc had ever wanted became his. The expense of others was something that he didn’t consider, never had.

It’s why when he met another tortured soul, one who had felt the same aspirations as he had once before, they’d collided in mutual understanding. It was something ridiculous, to find love in a pit that could torture souls until there was nothing left. Not for Caradoc, not one like him who understood what it was like to get what he wanted in the most ridiculous of circumstances. He also knew what it was like to sweet talk, what it was like to understand someone in a place where there was nothing but dull emptiness.

When the time came, when there was a witch calling for a familiar – it was the soul he’d fallen in love with that had gotten there first. Moments before exiting, moments before they were free – Caradoc a step behind. He called out to stop them, some ridiculous goodbye. He felt like the Caradoc of old, the one who’d loudly proclaimed and won the hearts of Roman citizens to procure his freedom instead of death. This was no different. Their defenses down, it was Caradoc who shoved them back and walked out victorious.

A young witch was awaiting him on the other side. Dark curls and bright hazel eyes. There was no fight to be had – it was a pact of blood between witch and familiar. Caradoc would bide his time in the mortal realm, stand at Raffaele’s side when he needed him. Rome apparently was calling him back, little remorse for the soul he’d left behind. Caradoc was on his third chance at this point, and well, who was he not to live his life to the fullest once more? All things glitter and gleam, and he’d take what he wanted.

personality

+ witty, loyal, ambitious

- dramatic, petty, violent

played by Lauren. est. she/her.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anaticula

Anaticula

https://ift.tt/URcDHxS

by smutandscotch

Alex is a High General’s Alpha son during the Invasion of Briton, Henry is the Omega son of a Catuvellauni War Chief whose castle has just fallen to the invading armies. They meet under less than ideal circumstances.

Words: 2372, Chapters: 1/?, Language: English

Fandoms: Red White & Royal Blue - Casey McQuiston, Red White & Royal Blue (2023)

Rating: Explicit

Warnings: Graphic Depictions Of Violence, Rape/Non-Con

Categories: F/F, F/M, M/M

Characters: Henry Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor, Alex Claremont-Diaz, Nora Holleran, Percy "Pez" Okonjo, Ellen Claremont, Beatrice Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor, Philip Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor

Relationships: Alex Claremont-Diaz/Henry Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor, June Claremont-Diaz/Nora Holleran/Percy "Pez" Okonjo, Liam/Spencer (Red White & Royal Blue)

Additional Tags: Attempted Rape/Non-Con, Rape/Non-con Elements, Angst and Hurt/Comfort, Enemies to Lovers, Alpha/Beta/Omega Dynamics, Alpha/Omega, Mpreg

via AO3 works tagged 'Alex Claremont-Diaz/Henry Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor' https://ift.tt/IHMkqW2

January 15, 2024 at 07:04PM

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Day 13: 30,225 words! As I suspected, working on something else gave me more power to work on this project, and while I didn't get much actual job work done, I did write another 4,000 words of RP backstory that will probably never be used. But it was fun, and it gave me a creative boost, and that's what matters, right?

Last line: “Kings and chiefs of the Trinovantes, the Corieltauvi, the Catuvellauni,” she said. “You say I have no victories, no stories, and no horse. I stand before you now, with my victory, my story, and, most importantly, my horse. So I ask you again, kings and chiefs: will you ride beside me into battle against Rome, the traitor, the usurper? Or shall I leave you behind to drown in your foolish pride? I ask you this now,” she finished, baring her teeth. She caught their eyes widening as they looked past her, and knew Avon was doing the same. “I will not ask you again.”

#more of a last paragraph#but i like it#and it's nice to end on a section break for once#i did write it at 3am#so it'll probably read terribly in the morning#but whatever :)#mayhaps a novel#boudica story#nanowrimo 2023

0 notes

Text

British Iron Age, CATUVELLAUNI, Cunobelin (8-41 AD), Stater, Linear type [class 2], ear of barley with five pairs of grains dividing [c]amv, rev. horse bounding right with ladder mane, branch and two pellets above, cv[n] below, 5.42g/12h (Sills 551; ABC 2774; VA 1925-1; S 281). Die break on obverse, good very fine, attractive rosy gold [Noonans auction April 2023]

From numismatic evidence, Cunobelin appears to have taken power after the death of his father Tasciovanus, and following the Roman defeat in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, Germania in AD 9, which possibly emboldened him to act against the Trinovantes capital at Camulodunem. The Trinovantes were a Roman ally whose independence was protected by a treaty they made with Julius Caesar in 54 BC, but problems in Germania severely discouraged Augustus's territorial ambitions and ability to defend allies in Britain. Cunobelin’s aggressive policy of expansion that involved members of his family eventually led to Roman concern over the extent of his power, Suetonius calling him ‘king of the Britons’. Following his death just prior to AD 43 the emperor Claudius took the decision to invade Britain, and the minting of tribal coins ceased shortly afterwards.

0 notes

Text

It is important to note that municipia were urban settlements that were created and governed by the Roman administration in Roman Britain, so there were no native municipia that were not urbanized by the Romans.

However, there were some native settlements that existed in Roman Britain that were not founded by the Romans and were not classified as municipia. These settlements may have had different forms of local government, such as tribal councils or chieftainships. Some examples of these settlements include:

Durotriges - a tribe located in what is now Dorset and surrounding areas.

Brigantes - a tribe located in what is now northern England, including the area around modern-day Yorkshire.

Iceni - a tribe located in what is now Norfolk and Suffolk.

Silures - a tribe located in what is now southeastern Wales.

Catuvellauni - a tribe located in what is now eastern England, including the area around modern-day Hertfordshire.

These settlements may have had different levels of interaction with the Romans and Romanized culture, but they were not established as municipia by the Romans.

0 notes

Text

History of the United Kingdom

England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.[1] The earliest evidence for early modern humans in Northwestern Europe, a jawbone discovered in Devon at Kents Cavern in 1927, was re-dated in 2011 to between 41,000 and 44,000 years old.[2] Continuous human habitation in England dates to around 13,000 years ago (see Creswellian), at the end of the Last Glacial Period. The region has numerous remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age, such as Stonehenge and Avebury. In the Iron Age, all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, was inhabited by the Celtic people known as the Britons, including some Belgic tribes (e.g. the Atrebates, the Catuvellauni, the Trinovantes, etc.) in the south east. In AD 43 the Roman conquest of Britain began; the Romans maintained control of their province of Britannia until the early 5th century.The end of Roman rule in Britain facilitated the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, which historians often regard as the origin of England and of the English people. The Anglo-Saxons, a collection of various Germanic peoples, established several kingdoms that became the primary powers in present-day England and parts of southern Scotland.[3] They introduced the Old English language, which largely displaced the previous Brittonic language. The Anglo-Saxons warred with British successor states in western Britain and the Hen Ogledd (Old North; the Brittonic-speaking parts of northern Britain), as well as with each other. Raids by Vikings became frequent after about AD 800, and the Norsemen settled in large parts of what is now England. During this period, several rulers attempted to unite the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, an effort that led to the emergence of the Kingdom of England by the 10th century.In 1066, a Norman expedition invaded and conquered England. The Norman dynasty, established by William the Conqueror, ruled England for over half a century before the period of succession crisis known as the Anarchy (1135–1154). Following the Anarchy, England came under the rule of the House of Plantagenet, a dynasty which later inherited claims to the Kingdom of France. During this period, Magna Carta was signed. A succession crisis in France led to the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), a series of conflicts involving the peoples of both nations. Following the Hundred Years' Wars, England became embroiled in its own succession wars. The Wars of the Roses pitted two branches of the House of Plantagenet against one another, the House of York and the House of Lancaster. The Lancastrian Henry Tudor ended the War of the Roses and established the Tudor dynasty in 1485.Under the Tudors and the later Stuart dynasty, England became a colonial power. During the rule of the Stuarts, the English Civil War took place between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists, which resulted in the execution of King Charles I (1649) and the establishment of a series of republican governments—first, a Parliamentary republic known as the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653), then a military dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell known as the Protectorate (1653–1659). The Stuarts returned to the restored throne in 1660, though continued questions over religion and power resulted in the deposition of another Stuart king, James II, in the Glorious Revolution (1688). England, which had subsumed Wales in the 16th century under Henry VIII, united with Scotland in 1707 to form a new sovereign state called Great Britain.[4][5][6] Following the Industrial Revolution, which started in England, Great Britain ruled a colonial Empire, the largest in recorded history. Following a process of decolonisation in the 20th century, mainly caused by the weakening of Great Britain's power in the two World Wars; almost all of the empire's overseas territories became independent countries.

1 note

·

View note

Text

CLAN CARRUTHERS: Caratacus of the Catuvellauni - was he a Carruthers?

CLAN CARRUTHERS: Caratacus of the Catuvellauni – was he a Carruthers?

Caratacus-Wiki

In the first century AD there lived a Chieftain, a king in his own right of a Celtic tribe called the Catuvellauni, whose name was Caratacus (The ancient Cumbric/Welsh form was Caradog/k).

Their lands covered a huge area in the south eastern aspect of the island and as such their influence, in what is now known as modern Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Berkshire,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Caractacus fue un rey tribal de los antiguos Bretones de la Edad del Hierro y gobernador de los Catuvellauni, una poderosa tribu británica. Era hijo del rey celta Cunobeline y gobernó Britania desde el año 43 d. C., hasta el 50 d. C.

0 notes

Text

CARATACUS - CLAN CARRUTHERS CCIS

CARATACUS – CLAN CARRUTHERS CCIS

CARATACUS OR COROTACUS

CARRUTHERS DNA ANCESTOR

Caractacus, sometimes known as Caratacus or Caradoc, was the son of the Celtic king, Cunobeline, was the king of the Catuvellauni tribe inhabited the Hertfordshire area. The Catuvellauni were an aggressive tribe, who extending their territory at the expense of nearby tribes like the Atrebates and had previously opposed the Romans under their…

View On WordPress

#Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan Society International#Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan Society International LLC#CAER CARADOC#CARATACUS#carruthers#Carruthers Clan#Carruthers history#CELTIC KING#Clan Carruthers#clan carruthers int society LLC#Clan Carruthers LLC#Clan Chief#COROTACUS#scotland#WARRIOR

0 notes

Photo

Catuvellauni “Hidden Faces” gold stater (Iron Age Britain). On the obverse are stylized crescents and wreaths with hidden faces; on the reverse is a Celtic warrior on horseback, carrying a carnyx.

This coin was minted during the reign of Tasciovanus, who became king around 20 BC. He ruled from Verlamion, which is the site of modern-day St. Albans.

#history#prehistory#numismatics#music#music history#iron age#britain#prehistoric britain#england#catuvellauni#hertfordshire#verlamion#st. albans#tasciovanus#carnyx

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

English History (Part 5): Iron Age

Iron Age (c. 800 – 43 AD)

From the beginning of the Iron Age, relations between the land and people were governed by an advanced concept of territoriality. This concept of territoriality had gained strength over the millennia – leaders & tribes were already firmly associated with specific regions, which can be seen in the boundaries and locations of settlements.

But this all intensified greatly during the Iron Age, and iron played a huge part in it. Gradually, new trade networks and forms of alliance were established. Ritual and ceremonial objects were made out of iron. The iron trade contributed to the eventual shape of England, as the various regions were becoming more intensely organized and controlled.

The hierarchical structure of societies also intensified. There were chieftains and sub-chieftains; warriors and priests; farmers and craftsmen; workers and slaves. Slave irons have been found near St. Albans (Hertfordshire), and a gang chain on Anglesey (an island off the north-west coast of Wales).

Meanwhile, funerary practices for the elite were becoming extremely elaborate. Iron Age chieftains were buried surrounded by molten silver, gold cloth, ivory, iron chainmail suits, and precious cups & bowls. One mortuary chamber was found to have trampled earth around its base, which suggests that people danced there.

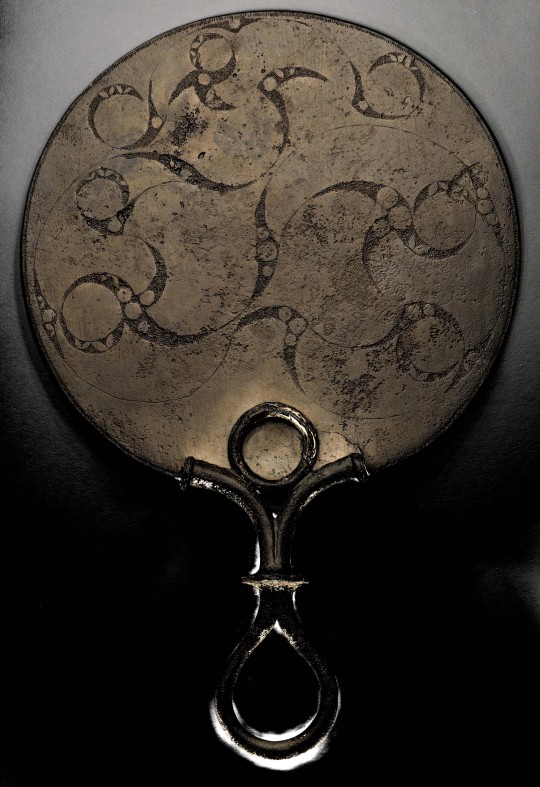

Elite women's graves contained many ornaments, including mirrors, brooches and bangles, bowls, beads and tweezers. On woman was buried with a large bronze bowl placed over her face.

The Oxfordshire Mirror, from the 00s BC.

Because of the increased sense of territoriality, regional identities were strong. This can be seen in the types of settlements in various regions of England:

Eastern England – undefended settlements (similar to villages) among open fields.

South-western England – small communities in defended homesteads, and unenclosed settlements at a distance. This was likely a division between the tribal leaders and the ordinary people.

North-eastern England – defended homesteads.

North-western England – round houses known as “beehive huts”.

Wessex Culture (Salisbury Plain) – a pattern of large territorial groupings based around hill forts.

There are variations upon these themes, such as the pit dwellings carved out of the chalk in Hampshire (a county on the southern coast); and the lake villages of Somerset (south-western England), with round huts built upon floating islands of logs.

The hill forts of Wessex show that this society was strongly hierarchical. They probably originated in the Cotswolds (south-central & south-western England), and then spread over the whole of south-central England. They were a symbol of elite ownership, as they demonstrated the mastery of land and resources.

The territory controlled by each fort was often marked out by linear earthworks that served as boundaries. The forts became more heavily-defended over the Iron Age, and some of them were occupied for centuries.

These hill forts served as towns, not just forts. They had clusters of building and streets, temples and storage facilities, and “zones” for separate industrial activities. The circular houses were made of upright posts, woven together with wattle and sticks of hazel. Their doors & porches faced east. The roofss were usually thatched with reeds or straw, which was held in place with a daub of dung, clay & straw. Soot from the peat fires was a valuable manure, so the dung mixture (and thatch?) was probably replaced each year. The people had small cupboards inside their houses to store weapons in.

The populations of these hill forts were small, from 20 to 200, but they were the beginning of urban English life. It is possible that London was once a hill fort, with its origins buried beneath the modern town.

British Camp, an Iron Age hill fort in Hertfordshire.

The many small tribes of this period lived in a state of constant alert against their rivals. There were cattle raids, conflicts between warriors, and even large-scale wars. Some hill forts were stormed and burned; bodies have been found in the ramparts, with their bones marked & hacked.

In this sort of a culture, heroic songs & tales would have been sung & told to celebrate the deeds of individual warriors and/or leaders. Early Irish epics have such tales, perhaps containing stories & refrains from the prehistoric Irish tribes. A comparison with the Iliad can be made.

These tribes & regional groupings did have network alliances and kinship ties, however. Many smaller clans were eventually integrated, and became larger territorial units (perhaps because of danger). These were the English tribes whom the Romans would confront later.

By the end of the Iron Age, some hill forts had become dominant, and took on the role of regional capitals. The population increased steadily, and so agriculture became even more intensive. People continued to clear woodland and forest. The thick clay soils were worked with heavy wheeled ploughs. This was the foundation for the agricultural economy of England. They grew wheat in Somerset and barley in Wiltshire, and they still do today.

In 325 BC, the Greek merchant & explorer Pytheas landed on England's shores. He named the island as Prettanike or Brettaniai, hence why we have the name “Britain” today. He gave the land of the Picts the diminutive name Pryden. He visited Cornwall, and watched people there work and purify the ore.

Pytheas wrote about the people worshipping various Greek gods, but he was simply projecting the Greek names onto the native Celtic gods. The Greeks saw all foreign gods in their own terms.

He wrote of seeing “a wonderful sacred precinct of Apollo and a celebrated temple festooned with many offerings”. This temple was “spherical in shape”. Close by there was a city “sacred to this god” who kings were called “Boreades” [the Greek god of the cold north wind].

Iron Age art (often called Celtic art) was very intricate, with a mastery of artificial form and linearity. It uses spirals and swastikas, curves and circles. Its patterns are related to the whorls, spirals & concentric circles carved upon Mesolithic passage graves several millennia earlier. This suggests a continuity of belief and worship.

The Battersea Shield (c. 350 - 50 BC), a decorative shield facing.

The religion of England was Druidism. There were certain sacred places, including caves and sacred groves. Druids congregated in these sacred groves, with ancient trees creating the setting for ritual practice.

In a barrow in Yorkshire, dating back to the early Bronze Age, drum-shaped idols made of chalk have been found. They have what seem to be human eyes & noses. 2,000 years later, the British writer Gildas (c. 500 – 570 AD) wrote of these “diabolical idols...of which we still see some mouldering away within or without the deserted temples, with the customary stiff and deformed features.” This shows that there was a long tradition of worship that may have had its roots in the Neolithic Period.

The image of the horned god Cernunnons has been found at Cirencester (Gloucestershire), and images of the horse goddess Epona in Wiltshire and Essex. In East Stoke (Nottinghamshire), a carving of the hammer god Sucellus has been found. The mysterious god Lud (or Nud) has his name in Ludgate Hill & Ludgate Circus (London).

There were religious sanctuaries all over the land, and even the smallest settlements probably had their own central shrines. They have been found in hill forts, within ditched enclosures, along boundaries, and above barrow graves. Often, Roman temples or early Christian churches were built atop them.

During the Iron Age, it was believed that the rooster served as a defence against thunderstorms. This is why we have weathercocks on church steeples.

Human sacrifice was practised, probably in order to sanctify the land. One man was bludgeoned to death and had his throat cut before being deposited in the marsh in Cheshire (north-western England). In southern England, many skeletons have been found in the bottom of bits, flexed into unnatural positions.

Severed heads, probably believed to be the site of the soul/spirit, were also important. Skulls have been found lined up in a row. Often the bodies of defeated enemies were beheaded, and their heads either buried or placed in running water. 300 skulls have been found in the Thames, dating from the Neolithic Period to the Iron Age.

According to Caesar, the Druids (high priests) created images of wicker-work, which they “fill with living men and, setting them on fire, the men are destroyed by the flames.” The Druid priests were the lawmakers of the land – they determined rewards & punishments; and settled disputes over boundaries & property.

Pliny wrote that the Druids “esteem nothing more sacred than the mistletoe”. The high priests “select groves of oak, and use the leaves of the mistletoe in all sacred rites.” They tied the sacrificial victim to an oak tree, and the killers wore chaplets (garlands/circlets worn on the head) made of oak leaves.

The Druids practised divination, astrology and magic. They believed that the soul was immortal, and was reincarnated. The Roman writers considered this belief to make clear the native English contempt for death.

The Druids worshipped the sun and moon, and this solar belief persisted even after their demise. In 1452, a butcher from Standon (Hertfordshire) was accused of proclaiming that there was no god except for the sun and moon. The Druids' power was retained by the Anglo-Saxon bishops, and the tonsures of early Christian monks may also have originated with the Druids. Thomas Hardy, in Tess of the d'Ubervilles, notes that “old customs” last longer on clay soils.

By 100 BC, there were 15 large tribes in England, and they were coming under the control of leaders who were now being called kings. In the years before the main Roman invasion, Suetonius named Cunobelis (leader of the Catuvellauni) as “rex Britannorum”. Cunobelis' capital was St. Albans (Hertfordshire, southern England), and he controlled a large area north of the Thames, including Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire and Oxfordshire. The Catuvellauni were a fully-formed elite culture of warriors and priests, and its traditions went back to the early Bronze Age. Cunobelis is the Cymbeline of Shakespeare's play of the same name.

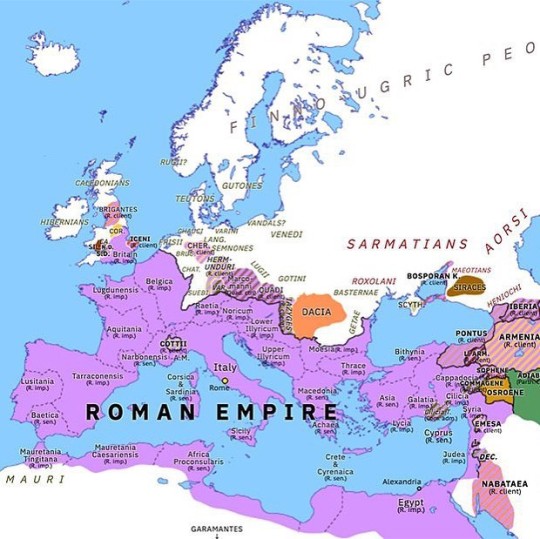

Territory of the Catuvellauni.

Territories of southern Britain’s Celtic tribes.

At some time during the 400s BC, members of the Parisii (a tribe from northern Gaul) settled in Yorkshire, where they created an archaeologically distinctive community. During the 00s BC, a tribe called the Belgae launched a small invasion, and eventually settled in Hampshire, Essex and Kent. The Roman name for Winchester was Venta Belgarum, meaning “the market of the Belgae”.

England's population during the late Iron Age was about 2 million, and by the time the Romans left, it would be 3 million. It was a flourishing, wealthy country, with a surplus of corn, which was why the Romans wanted to invade it.

The south of England was particularly well-off. In south-eastern and central southern England, there was a spread of settlements with extensive towns & villages, markets, industries, shrines, cemeteries and fields. Julius Caesar stated that “the population is very large, their homesteads thick on the ground and very much like those in Gaul, and the cattle numerous. As money they use either bronze or gold coins or iron bars with a fixed standard of weight.” The coins had the stamp of powerful leaders, and made trade easier between tribes.

The further north you went, the less there was of all this. This was because the southern tribes had been trading extensively with Rome and Romanized Gaul long before the Roman invasion. They loved certain foods and luxury goods, and were Romanized to a fair extent.

But they still had their ancient tribal ways as well. There was consistent warfare between tribes, and various leaders appealed to Rome for assistance. Large earthworks were built as boundaries. The warriors rode chariots to battle, and were naked, covering their bodies with blue woad, and having pierced tattoos. Caesar wrote: “They wear their hair long, and shave all their bodies with the exception of their heads and their upper lips.”

#book: the history of england#history#prehistory#classics#trade#economics#art#art history#bronze age#iron age#britain#ancient rome#prehistoric britain#iron age britain#bronze age britain#roman britain#england#wales#wessex culture#catuvellauni#parisii#belgae#hampshire#somerset#yorkshire#druidism#pytheas#julius caesar

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NEW MAP: Europe 47: Roman Conquest of Britain (30 Apr 47 AD) https://buff.ly/2yIPqW2 Following the capture of Camulodunon (43 AD), Claudius returned to the continent, leaving command in Britain to his general Aulus Plautius. Accepting the Iceni, Dobunni, and Brigantes as client states, Plautius consolidated the Roman hold in southern Britain by conquering the Catuvellauni heartland. Defeated, Caratacus, the last Catuvellauni king, fled to what is now Wales, where British tribes would continue to resist the invaders for several decades. #europe #history #welovehistory #map #ancienthistory #ancientworld #april #april30 #brigantes #catuvellauni #englishhistory #europeanhistory #iceni #parthia #romanempire #romans #roman #ancientrome #romanhistory #romanbritain #britishhistory #maps #newmap #historyteacher #historybuff #historygeek #historynerd #worldhistory #cartography #geopolitics (at Saint Albans) https://www.instagram.com/p/B06pbi6g8vo/?igshid=4flfsx81wgk4

#europe#history#welovehistory#map#ancienthistory#ancientworld#april#april30#brigantes#catuvellauni#englishhistory#europeanhistory#iceni#parthia#romanempire#romans#roman#ancientrome#romanhistory#romanbritain#britishhistory#maps#newmap#historyteacher#historybuff#historygeek#historynerd#worldhistory#cartography#geopolitics

13 notes

·

View notes