#cartesdhistoire

Photo

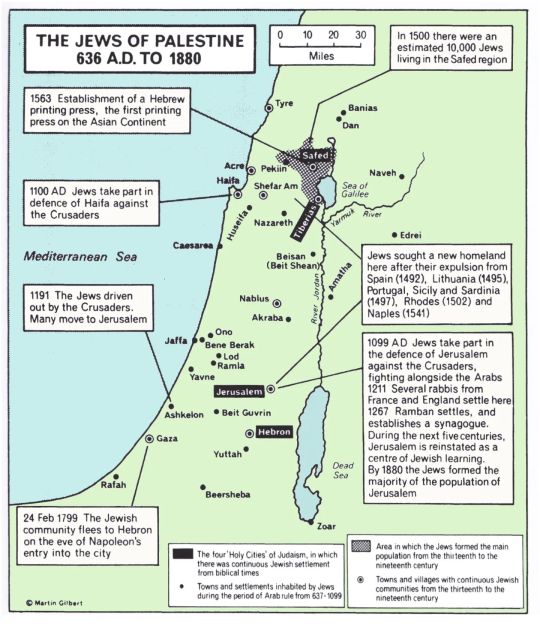

Jews in Palestine from the 7th century to the 19th century.

From “Atlas of Jewish History”, Martin Gilbert, Routledge, 1969, 2010

via cartesdhistoire

In 636, at the Battle of Yarmouk, the Arabs captured Tiberias and Galilee. Then they besieged and took Jerusalem and Caesarea before completing their conquest in 641 with the capture of Ascalon.

From the 8th century, the largest Jewish community was found in Ramleh, then, at the time of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1291), the most important Jewish communities were those on the coast: Tyre, Acre and Ascalon.

Between 1260 and 1516, relations between the Jews and the Mamluk power, fanatical and intolerant, were bad. The most important communities are in the interior (the ports were evacuated in the 13th century for fear of invasions): Jerusalem especially, Safed, Gaza, Hebron, a few villages in Upper Galilee. Pilgrimage to Jewish holy places – the “ziara” – is already very widespread there.

The Turks conquered Palestine in 1516. The community of Safed experienced great expansion with the cultural and technical contribution of Judeo-Iberian refugees.

But throughout the 19th century, Muslim populations also settled in Palestine: some 20,000 Egyptians during the conquests of Mehemet-Ali (in Gaza, Jaffa and Jericho), then several tens of thousands of Muslims, coming from the former Ottoman territories of the Balkans and the Caucasus. The sultan grants them land on favorable terms in Galilee and the coastal plain of Sharon. The accounts of European travelers in Palestine attest to the existence of numerous villages where Arabic is not spoken.

From 1840, the Jewish population of Jerusalem grew at a much faster rate than that of other communities, reaching 11,000 people in 1870, or half of the total population, and this before the major movements of Jewish immigration which began. from the 1880s; the Jewish population has since retained its majority status.

In 1872, the Palestinian population (Bedouins excluded) was 381,954 inhabitants (85% Muslims, 11% Christians and 4% Jews).

202 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Habsburg Empire, 16th-17th centuries

« Atlas historique », Nathan, 1982

by cartesdhistoire

In 1519, Charles Quint found himself virtually the master of Europe. However, instead of viewing his role as a spiritual mission, he felt a deep sense of duty to his lineage. This obligation drove him to perpetuate, and if possible, enhance, what he had inherited for his successors. This principle, deeply ingrained in the tradition of the House of Burgundy, became a cornerstone of Habsburg governance, with each possession managed as if he were the sole monarch of each one.

In 1556, Philippe II inherited the ancient estates of Burgundy, the Spanish Monarchy (including its Italian dependencies), and the Duchy of Milan. Throughout his foreign policy, the sense of dynasty always took precedence: the Dutch were treated more as rebels than heretics; the incorporation of Portugal in 1580 was driven by the defense of succession rights rather than expansionism. Similarly, interventions in the French civil war and the Armada against England in 1588 aimed more at defending the integrity of heritage than pursuing a crusade.

Under Philippe III (1598-1621), signs of decline began to emerge within the Hispanic monarchy. The reign of Philippe IV (1621-1665) was marked by continual unrest, with no respite for a year of peace. Involvement in the Thirty Years War strained the Castilian Treasury, leading to economic crises in the 1630s and subsequent anti-tax revolts. The dissatisfaction of peripheral elites culminated in secessionist revolts in Catalonia and Portugal in 1640, while nobles conspired against the Crown. In Italy, revolts in Naples and Sicily in 1647 further exacerbated the crisis. Amid internal opposition, economic depression, and military setbacks, the Hispanic Monarchy struggled for survival, with only the Portuguese secession achieving success.

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy & King of England (1066-1087)

Map published in “L’Histoire” n°424 (June 2016); included in the “World Historical Atlas” by Christian Grataloup, Les Arènes/L’Histoire, 2019

by cartesdhistoire

In 1066, the victory at Hastings linked England to the continent for several centuries, despite the difficult conquest of the North and Cornwall. In about ten years, William extended Norman power from the Scottish marches to Maine. He stitched the territory with castles, took control of the administration and avoided the creation of vast vassal fiefdoms, apart from the counties facing Wales and Scotland. The duke-king, upon his death in 1087, was in a position to compete with the king of France.

1035: On the death of his father, William becomes Duke of Normandy at the age of 8.

1047: Battle of Val-ès-Dunes. William, allied with the French king Henry I, defeats a coalition of rebel Norman barons.

1051: Edward the Confessor, King of England, asks William to succeed him.

1052: Breakdown of the alliance between William and Henry I.

Around 1053: Marriage of William and Mathilde of Flanders.

1063: Harold is taken prisoner by Gui de Ponthieu. William had him released and demanded that he undertake to recognize him as king of England upon Edward's death.

1066, October 14: Battle of Hastings.

1066, December 25: William crowned king of England.

1069-1070: Rebellion in northern England and its suppression.

1083: Death of Queen Mathilde. She is buried in the Abbaye aux Dames de Caen, which she founded.

1085-1086: Census for the completion of the Domesday Book.

1087: Death of William. He is buried in the Men's Abbey of Caen, which he founded. His eldest son, Robert Courteheuse, succeeded him as Duke of Normandy; his third son William II Roux becomes king of England.

1204: Philippe Auguste, king of France, defeats John Lackland and conquers Normandy. It is the end of the cross-Channel empire created by William.

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Germany and Austria in 1925

« Atlas des peuples d’Europe occidentale », Jean et André Sellier, La Découverte, 1995

by cartesdhistoire

From the summer of 1918, the German offensive in the West was an absolute failure. However, in Berlin, civil authorities continued to believe that Germany had the upper hand. On October 2, the General Staff informed the parties in the Reichstag of the urgent need to end the fighting swiftly, as the situation risked deteriorating decisively. The parliamentarians were shocked and dismayed. At 5 a.m. on November 11, the armistice was signed in Rethondes.

Yet, the Germans did not tangibly feel their defeat or experience it in their daily lives, except in the Rhineland. The country remained physically intact, its infrastructure undamaged, and no decisive battle led to the rout of the German army. The victory on the Eastern Front was also significant. The General Staff managed to conceal the army's disintegration by repatriating regiments in good order whenever possible, to the cheers of the crowds. Consequently, defeat for the Germans became an abstract notion that could be denied. How could a stable peace be established with a defeated opponent who refused to acknowledge their defeat?

Pétain and Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, had initially wanted to continue the Allied offensive against a crumbling German army and advance to the Rhine to make the Germans understand and admit the extent of their defeat. However, after four years of war, this proved to be politically and morally impossible, a fact that Clemenceau and Foch fully understood.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, was the best possible outcome at the time of its negotiation. However, it also sparked controversy among the victorious camp when Keynes published "The Economic Consequences of the Peace." This book, which became immensely popular, was used in Germany to justify opposition to the treaty and simultaneously created a myth in Anglo-Saxon countries that Germany was being unfairly treated.

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

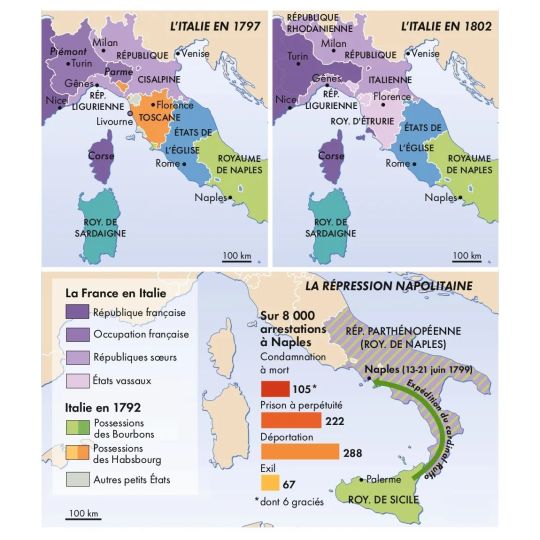

Italy from 1796 to 1805

Cartes 1-4 & 6 : « Atlas de la révolution française », Beaurepaire & Marzagalli, Autrement, 2016

Carte 5 : « Atlas de l’empire napoléonien », Chappey & Gainot, Autrement, 2e éd., 2015

by cartesdhistoire

The incursion of Bonaparte's army into Italy in the spring of 1796 was primarily a diversion to relieve pressure on the Rhine front. However, its success quickly opened up new possibilities: French support and the activism of local patriots led to the establishment of sister republics. Over three years (1796-1799), known as the Triennio, the political landscape and institutions of the peninsula underwent significant changes. This period, marked by reforms and democratic achievements, as well as the involvement of individuals previously excluded from public affairs, is crucial for understanding how the Triennio influenced the attitudes of both elites and the general populace during and after the Napoleonic era.

However, the sister republics collapsed in the spring of 1799 in the face of the successes of the Austro-Russian armies of the Second Coalition and the armed uprisings of peasants incited by the clergy and angered by French abuses. Naples surrendered in June 1799, and the repression there was severe.

The political landscape of the peninsula was once again reshaped by France following the Second Italian Campaign, which began in 1800. The Cisalpine Republic, reinstated after the Battle of Marengo and expanded during the Peace of Lunéville, gave way to the Italian Republic in 1802, then became a kingdom in 1805. The kingdom's territory expanded to include Veneto and Istria (1805), the Marche region (1808), and South Tyrol (1810). Thanks to the Vice-President of the Italian Republic, Francesco Melzi d'Eril, the political efforts during these years resulted in the establishment of a modern state and significant reforms in administration, justice, and the military.

The Napoleonic experience helped to politically educate the Italian elites, providing them with a shared institutional and legal framework, as well as standardized administrative practices, which made the idea of unity feasible.

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

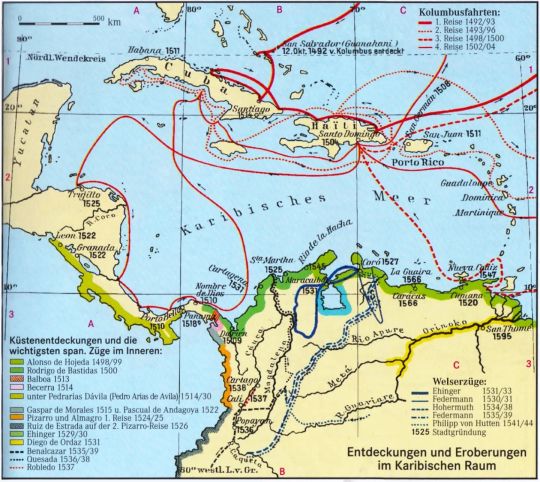

Discovery and conquest of the Caribbean Sea by the Spanish, 1492-1595.

« Westermann Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte », 1997

by cartesdhistoire

On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus reached San Salvador in what is now the Bahamas archipelago, then he discovered the northeast coast of Cuba and Haiti (La Española). During a second expedition, he discovered Dominica and Guadeloupe, then he explored the south coast of Cuba and discovered Jamaica (Santiago). His brother Bartolomé founded Santo Domingo in 1498. In 1508, Ponce de León named a harbor on the island Puerto Rico, which took its name, then he founded San Juan in 1511.

During his third voyage, in 1498, Columbus reached the island of Trinidad and discovered the mouths of the Orinoco River: the flow of the river indicated that the hinterland was much larger than the islands previously discovered. So, the idea of “mainland” began to emerge. In 1499, Alonso de Ojeda, accompanied by Amerigo Vespucci, explored the coast from east to west, starting from Guyana. On the shores of Lake Maracaibo, upon seeing Indians living in huts on stilts, he named this region “Venezuela”, meaning little Venice.

Rodrigo de Bastidas discovered the mouth of the Magdalena River and was the first to land on the Isthmus of Panama in 1500. During his fourth voyage, Columbus sailed along the coast of the isthmus from present-day Honduras (1502). Vasco Nuñez de Balboa founded Santa María la Antigua del Darién in 1510, the first permanent colony on the mainland, then he discovered the “South Sea” in 1513. Pedrarias Dávila founded Panama in 1519.

In 1528, Charles V granted the exploitation of Venezuela to Augsburg bankers, the Welsers. The expedition of Nicolás de Federmán reached the land of the Muiscas in the Andes in 1539.

The first European to ascend the Orinoco was Diego de Ordaz in 1531 (he was also the first European to reach the summit of the Popocatépetl volcano in Mexico). Where the Orinoco narrows the most, Antonio de Berrío founded the town of Santo Tomás de Guayana in 1595.

In the Andes, Benalcázar founded the Spanish Quito in 1534, then Popayán in 1537, and Jiménez de Quesada founded Santa Fe de Bogotá in 1538.

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Medieval Brittany, 9th-14th century

« Atlas historique de la France », Les Arènes, 2020

by cartesdhistoire

The Brittany peninsula experienced an influx of people in the 6th century, including invaders from England. An independent Brittany emerged amidst the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and Viking raids. Nominoë, appointed representative of the emperor, established his sovereignty after defeating Charles the Bald at the Battle of Ballon in 845. His son, Erispoë, became king of Brittany in 851. Armorica became a duchy in 939 but remained de facto autonomous, under the influence of the Plantagenets (1148-1203) and then the Capetians (1203-1341). Brittany became a duchy-peerage of the Kingdom of France in 1239. In 1491, Duchess Anne married King Charles VIII of France, initiating a process that culminated in the Edict of Union definitively attaching Brittany to the kingdom in 1532.

Breton is spoken west of a Plouha-Loudéac-La Roche-Bernard-Batz line, which has remained relatively stable over time. From the 9th century, the entire eastern area of Brittany spoke Gallo, an Oïl dialect related to Norman and Angevin. This region includes Dol, the seat of the archbishopric until 1199, and cities such as Nantes and Rennes, where the States of Brittany convened from 1352.

The administrative language of Brittany was not Breton but Latin. French began to appear in the 1240s and became widely used between 1250 and 1280, a trend observed in other French regions during the same period. From the mid-13th century, counts of Champagne favored French for their feudal affairs. The Count of Blois definitively abandoned Latin in favor of French from 1267. The Dukes of Burgundy extensively used the vernacular language during the second half of the 13th century, with French becoming their exclusive language from Duke Eudes (1315-1349). Paradoxically, French only became the dominant language of the Chancellery of the kings of France later, under Philip VI (1328-1350).

79 notes

·

View notes

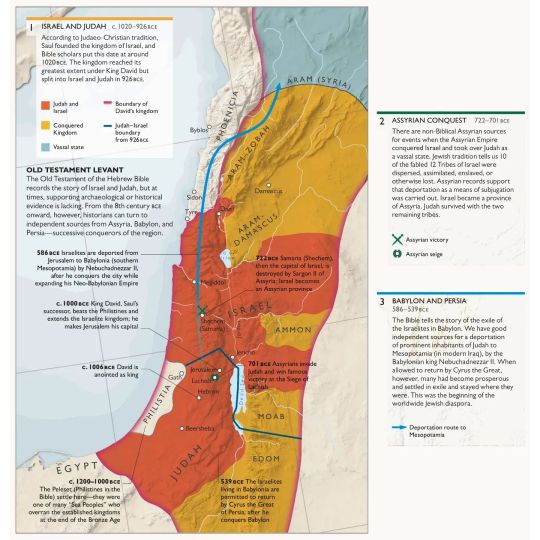

Photo

Ancient Palestine

“History of the world map by map”, Dorling Kindersley, 2018

by cartesdhistoire

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolts and revolutions in Italy under the Restoration

“Atlante storico”, Garzanti, 1966

by cartesdhistoire

The Congress of Vienna divided Italy into ten largely reactionary states, against which the secret society of Charbonnage, originating in the Kingdom of Naples in 1807, opposed itself. The "Carbonari," mainly from the middle classes, whose growth had been favored by French domination, claimed inspiration from the constitution of Cádiz promulgated by the Spanish parliament with Napoleon's agreement in 1812.

Revolutionary movements erupted first in Naples in the summer of 1820, followed by Palermo, which became the scene of a genuine civil war. The insurrection spread to Piedmont from March 1821; the insurgents were defeated in Novara on April 8, with Austrian assistance, leading to ruthless repression until October. Order on the peninsula was only fully restored in early 1822 by the Austrian army. Severe anti-liberal repression was felt in Modena, the Papal State, and Milan. At least 3,000 patriots went into exile between 1821 and 1823.

Echoing the Parisian revolution of 1830, which had a profound impact in Italy, an uprising erupted in early 1831 in Modena, Parma, and Bologna. On March 4, the Austrian army entered the Duchy of Modena, and on the 29th, the last remnants of the insurgent army capitulated. Fierce repression followed.

Patriots were divided into two models: revolutionary and democratic or liberal and moderate. The latter, itself subdivided into two currents, one advocating unification under the pope's auspices and the other under the leadership of the House of Savoy. The revolutionary model, predominant until 1848, found its embodiment in Giuseppe Mazzini, who envisioned a popular insurrection to overcome resistance from princes and local particularisms, leading to a republic. Mazzini's activism played a significant role in shaping the Italian people's national consciousness, but the utopian nature of the insurrectional path ultimately led to a deadlock.

70 notes

·

View notes

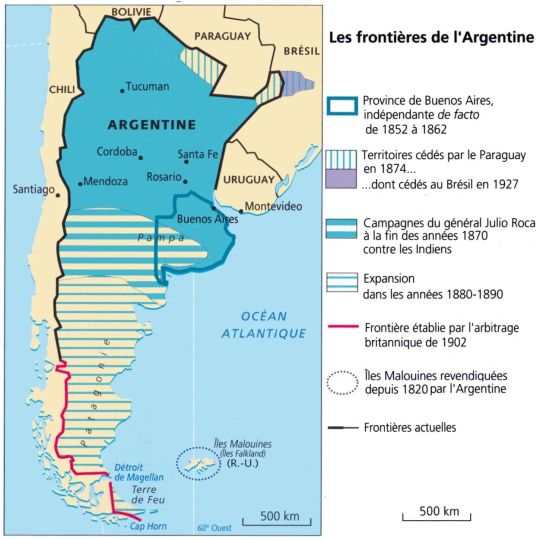

Photo

Argentina's borders

« Atlas des peuples d’Amérique », Jean Sellier, La Découverte, 2006

by cartesdhistoire

In 1853, Argentina adopted a constitution modeled after that of the United States, which combined federalism with presidential governance. However, Buenos Aires did not ratify this constitution and seceded until 1862. It did not become the federal capital until 1880, following its separation from the province.

In the northern regions, territorial expansion was fueled by the War of the Triple Alliance (involving Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay) against Paraguay between 1864 and 1870. Argentina occupied Misiones (located between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers) in 1868, as well as part of the Chaco (which is now the Argentine province of Formosa).

In the southern territories, expansion occurred at the expense of indigenous peoples who had never been subjugated by the Spaniards and who regularly raided the pampas (the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe). In 1878–1879, General Julio Roca decisively ended these raids by destroying both the summer camps and winter settlements of the indigenous peoples. This "conquest of the desert" led to the incorporation of 650,000 km² of arable land.

In Patagonia, resistance was not primarily from indigenous peoples, who were few in number, but rather from Chilean territorial ambitions. In 1884, Argentina established a foothold in Ushuaïa (Tierra del Fuego). A British arbitration took place in 1902, resulting in Argentina securing the Atlantic side and Chile obtaining control over the Pacific side.

In the South Atlantic, the Falkland Islands archipelago (which received its name from sailors from Saint-Malo) was uninhabited until 1764 when both the French and English undertook colonization efforts. The French departed the archipelago in 1770, followed by the English in 1774. However, after Argentina established a garrison there in 1820, the English protested, expelled the Argentines in 1832, and declared the islands a crown colony in 1833. By 1900, the archipelago had 2000 inhabitants of British origin. In April 1982, the Argentine armed forces attempted to seize the Falklands, but the English compelled them to surrender in June of the same year.

62 notes

·

View notes

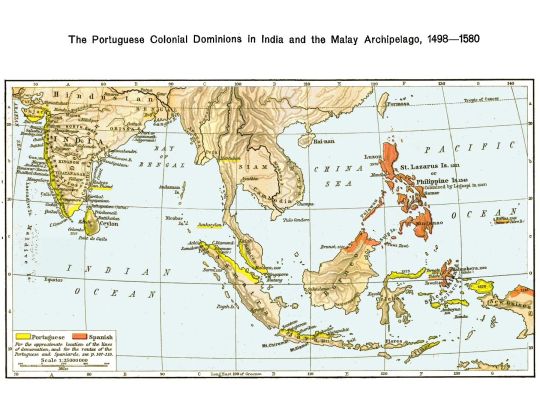

Photo

Spaniards and Portuguese in India and the Malay Archipelago, 1498-1580.

“Historical atlas”, William Shepherd, University of London Press, 3rd ed. 1924

by cartesdhistoire

Muslim merchants from Gujarat, based in Cambay, dominated maritime trade in the Indian Ocean in the 15th century, supported by Hindu and Jain financiers and an organized network of correspondents. The Malabar coast, a major pepper supplier, served as a hub for commercial interactions between Arab merchants from the Gulf of Aden or Oman and Chinese merchants – or their intermediaries – from Sumatra and Malacca. Muslim merchants primarily engaged in the spice trade.

The arrival of Vasco da Gama in Calicut in 1498 disrupted this system. In 1502, King Manuel entrusted him with commanding a second expedition aimed at eliminating all Muslim presence in the Indian Ocean. The Sultans of Gujarat and the Deccan sought assistance from a Mamluk fleet to counter the Portuguese, but it was defeated before Diu in 1509, paving the way for Portuguese conquests of Goa in 1510, Malacca in 1511, Hormuz in 1515, Diu in 1535, and Daman in 1539.

The Portuguese occupied the southwest coast of Ceylon from 1505 to access cinnamon, establishing a fort in Colombo in 1518. They controlled the north, west, and south coasts of the island, key areas for the cinnamon and precious stone trade.

The Moluccas were another target because the Banda Islands produced nutmeg, while Ternate and Tidore produced cloves. The Portuguese established privileged relations with the sultans of Ternate and Tidore, facilitating their settlement in Amboyna and Timor, despite the capture of Malacca from Sultan Mahmoud Shah.

The Portuguese monopoly endured until the emergence of the English East India Company and the Battle of Swally in 1612.

Meanwhile, Spain remained engaged in the spice race, aiming to connect America to the Moluccas and their spices. Following expeditions in 1525 (Loayza) and 1528 (Saavedra), Spain secured a definitive return route in 1565 (Urdaneta) and established settlements in the Philippines in 1571.

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Spanish Empire in 1600.

« Atlante storico », Geo-Mondadori, 2000

via cartesdhistoire

The Spanish West Indian Empire was centered in the north on the Viceroyalty of New Spain and in the south on the Viceroyalty of Peru. It was enriched with the Philippine Islands from 1565, after the Spaniards discovered routes enabling them to cross the Pacific Ocean. In 1571, the city of Manila was founded there.

From 1546, the Spanish exploited the mines of Potosi (Upper Peru), from which most of the world's silver was quickly extracted. From 1564, a convoy system of galleons loaded with silver crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach Spain. In the Pacific, once a year, the Manila Galleon transported silver from the New Spanish port of Acapulco to Manila in the Philippines. It made the return trip from the Philippines to Acapulco, carrying silk, porcelain, and Chinese lacquerware. From the 1590s, the value of this silver crossing the Pacific Ocean equaled all Atlantic trade combined.

74 notes

·

View notes

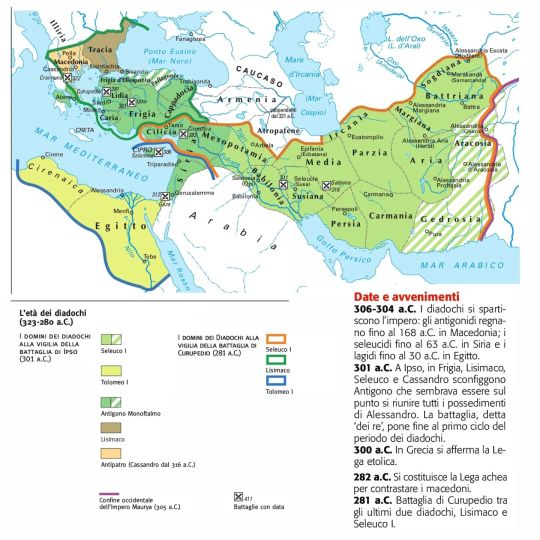

Photo

The Hellenistic world

"Atlante storico tascabile", Istituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara,1999

via cartesdhistoire

In 323 BC, Alexander died without heirs, possibly from the plague. His empire, already facing insurrectionary movements, did not outlive him. His generals, the Diadochi, began a protracted struggle for power: Antipater in Macedonia, Lysimachus in Thrace, Ptolemy in Egypt, Antigonus Monophthalmos in Asia Minor and Syria, and Seleucus in Babylon.

The first phase of the war among the Diadochi concluded at Ipsus in Phrygia in 301 BC, with the "battle of the kings." Lysimachus, Seleucus, and Cassander, son of Antipater, defeated Antigonus, who had been consistently victorious until then. Seleucus and Ptolemy, prudent rulers, founded dynasties destined for long endurance, even though they were not immune to the temptation of rebuilding Alexander's empire. The focal point of the conflict became Macedonia, and long wars ensued for its dominion.

The Epigones, successors of the Diadochi, instead supported the status quo. The kings of Egypt and Syria founded new cities, respecting the rights of existing poleis.

Nearly all Hellenistic kings surrounded themselves with scholars, artists, and scientists. Ptolemy I founded the largest library of antiquity in Alexandria, Egypt.

In 277 BC, the Galatians, of Celtic descent, settled in Asia Minor. Some provinces declared independence, including the kingdom of Pergamon, a city renowned for being built on terraces, distinguished by the splendor of its culture and art, exemplified by a library of 400,000 volumes.

The kingdom of Bactria, situated in the northern region of present-day Afghanistan, was also significant, representing the eastern extent of Hellenistic influence and serving as a crossroads between the cultures of the Mediterranean region and those of China and India.

Antiochus III, the greatest of the Seleucids, expanded the empire's territories. However, the invasion of Greece in 192 BC triggered a war with Rome. Following the war, the king was compelled to accept peace, marking the beginning of the inexorable decline of his empire.

84 notes

·

View notes

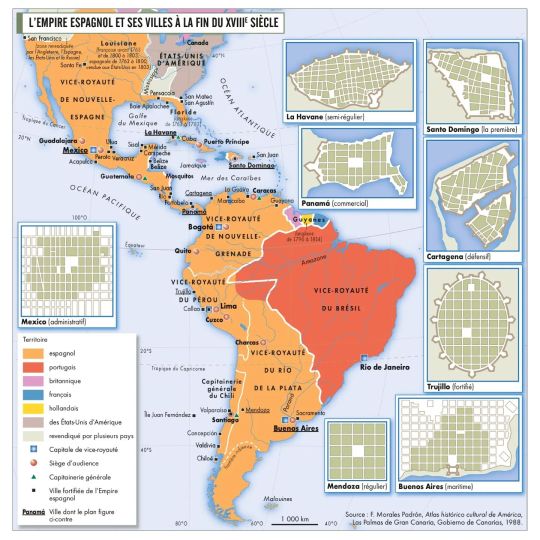

Photo

Spanish America

"Atlas des premières colonisations", Autrement, 2013

by cartesdhistoire

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

France after the Peace of Lunéville, 1801.

« Nouvel atlas de l’histoire de France », Cohen, Destemberg, Dusserre & Houte, Autrement, 2016

by cartesdhistoire

Belgium was annexed on October 1, 1795, after the United Provinces became a sister republic, theoretically independent (treaty of alliance of May 16).

In Italy, Bonaparte won dazzling victories, and between the spring and summer of 1797, he signed armistices, while Italian patriots took advantage of the offensive to proclaim the republic in Piedmont. The Peace of Campoformio (October 17, 1797) gave Austria the archbishopric of Salzburg and Veneto but confirmed the possession of Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine (from Alsace to Koblenz) to France, finalizing the birth of the Ligurian and Cisalpine Republics. In February 1798, French military intervention allowed Roman patriots to proclaim the Republic. These were allied states – with very formal independence.

In January 1799, the patriots led General Championnet to proclaim the ephemeral Neapolitan Republic which lasted only until June 24. However, after the occupation of Tuscany by French troops, all of Italy except Venice was occupied by the French, and most of it formed republics. The Italian unity desired by the patriots was possible, but the Directory took care, on the contrary, to prevent it definitively: from February 8 to 16, 1799, a referendum took place in Piedmont which gave a strong majority for annexation by France (effective on September 11, 1802).

On February 9, 1801, the Treaty of Lunéville was signed between France and Austria. It confirmed for France the possession of the Austrian Netherlands, the principality of Liège, and the left bank of the Rhine. Austria had to recognize the Batavian Republic and the Helvetic Republic. Additionally, Article 7 of the treaty provided for compensation to the dispossessed German princes, to whom territories would have to be redistributed, thus giving France the position of continental arbiter.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The German invasion & occupation of Northern France, 1870-1871

« Grand atlas de l’histoire de France », Autrement, 2011

via cartesdhistoire

64 notes

·

View notes