#but indecent is my beloved and she has to be included

Text

Propaganda

Margaret Lindsay (Frisco Kid, The House of the Seven Gables, Scarlet Street)—she was born in Dubuque, Iowa, then moved to England to make her stage debut. She framed herself as a British actress and moved back to America to try Hollywood, then starred with James Cagney in a bunch of movies. She was in the Ellery Queen movie series and The House of the Seven Gables. She never married (I suspect lesbian stuff) but lived with her sisters. She dated Cesar Romero and Liberace (I told you. Lesbian stuff.) Please include the pic of her in the tie [included above]

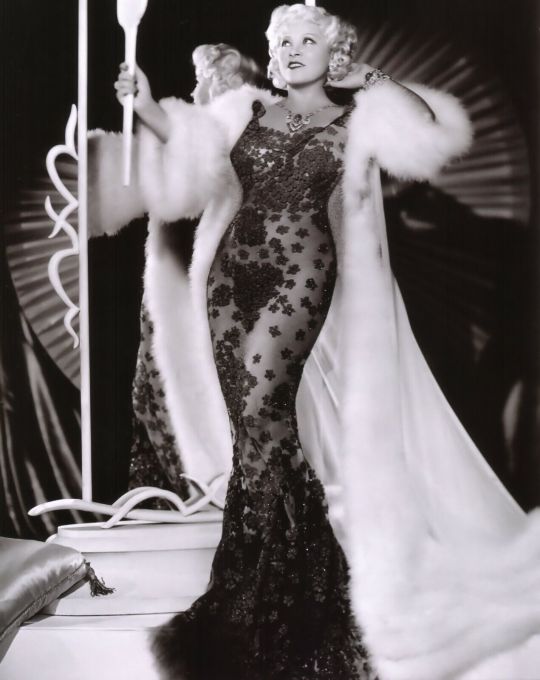

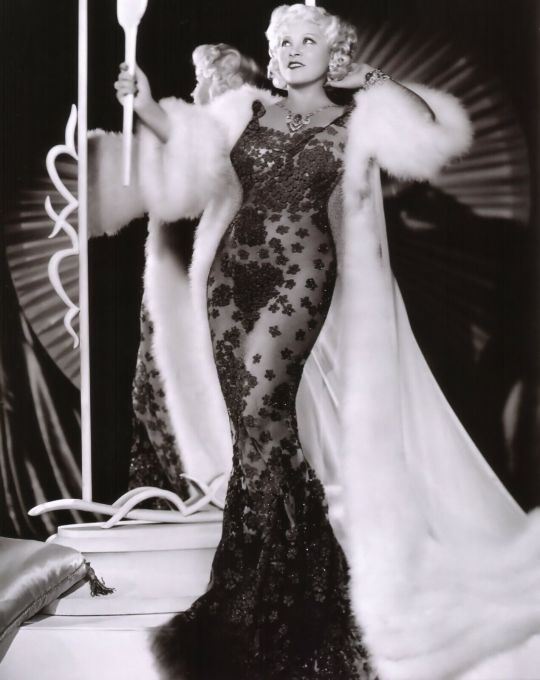

Mae West (She Done Him Wrong, I'm No Angel)—She is an absolute icon, the OG sex symbol. Every word from her mouth was an innuendo and she was proud of it. I guess one could say she slayed. She got Cary Grant his first acting role, as well. How could you NOT vote for someone who says such iconic stuff as "I do all my writing in bed; everybody knows I do my best work there" or "You only live once, but if you do it right, once is enough." SHE COINED THE PHRASE "IS THAT A GUN IN YOUR POCKET OR ARE YOU JUST HAPPY TO SEE ME?" I LOVE HER!!!

This is round 2 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Margaret Lindsay:

Mae West:

Her voice! Her body! She was thick as hell and SO confident.

Mae West is often called the queen of the sexual pun or innuendo, she was an early sex symbol and a comedy icon. She also has a quote saying "When I am good, I am very good. But when I am bad I am better!" which is possibly the peak of hot girl energy ever. (Including the clip here)

for an era that didn't have much wiggle room when it came to women that studios wanted in their films, it's refreshing that she was in her late 30s when she skyrocketed to movie fame. she was also curvy and witty and raunchy, an absolute icon!

Legendary sex symbol. Like 500 vintage iconic quotes and double entendres. "Is that a gun in your pocket, or are you just happy to see me? " "When I'm good, I'm very good. But when I'm bad, I'm better" / "It's not the men in your life that count, it's the life in your men" / "I feel like a million tonight. But one at a time." , "Marriage is a fine institution, but I'm not ready for an institution. " / " How tall are you without your horse? Six foot, seven inches. Never mind the six feet. Let's talk about the seven inches! " Look the pictures don't do her justice just watch a compilation and tell me that voice doesn't do it for you

youtube

She was a SEX GODDESS at a time when that was an extremely scandalous thing to be, and she worked it! She was sardonic, sarcastic, funny...and stacked! Favorite quote (from Night After Night, 1933): Random woman: Goodness! What beautiful diamonds! Mae West: Goodness had nothin' to do with it, dearie.

i personally love this silly production number from one of her lesser known movies

She was arrested for indecency and chose to serve 10 days in prison instead of paying the fine for the publicity, and she claimed that she refused to wear the ugly prison outfits so she wore her silk lingerie the entire time. Also one of the first historybound vintage fashion icons (although vintage for her was the Victorian era)

484 notes

·

View notes

Text

A trans comedian is receiving praise from mainstream media, but backlash from women, after a musical performance on UK comedy show Friday Night Live.

During the live program, trans-identified male comedian Jordan Gray ripped off his clothing to expose his entire naked body, and began to play his keyboard with his penis. This was during Gray’s rendition of his song “Better Than You,” which featured misogynistic lyrics intended to mock females.

“I’m a perfect woman, my tits will never shrink. I’m guaranteed to squirt, and I do anal by default … I am the lizard king, and I can do anything that any other woman can’t … I used to be a man, now I’m better than you,” Gray sang to an audience of delighted onlookers.

The explicit performance took place during a specialFriday Night Live revival event marking Channel 4’s 40th anniversary. The revival featured former Friday Night Live cast members Ben Elton, Enfield, Brand and Julian Clary as well as a number of new comedians, including Gray.

Mainstream media coverage of Gray’s performance has been overwhelmingly positive. PinkNews, a UK-based outlet, referred to Gray’s song as “rousing” and called the performance “iconic,” and characterized any opposition to the performer’s exposure of his genitals on television as “anti-trans.” The sentiment was shared by some LGBT activists on Twitter.

Irish Mirror chose to emphasize glowing comments which praised Gray as “amazing” and stated that “seeing a trans woman get naked on TV is exactly what we needed.”

Reporting on Gray’s exhibitionist stunt, The Daily Mail in particular prompted criticism for the use of the term “her penis” to refer to the incident.

Even some beloved British figures took to social media to heap praise upon Gray. Harry Potter actor Jason Isaacs complimented Gray’s “magnificent boobs and equally magnificent member” and called for Gray to run for Prime Minister.

But while no mainstream British outlet has called into question any safeguarding concerns related to the program, many on social media have stated their shock and outrage at what they consider to be indecent exposure, a sexual offense, being normalized, celebrated, and highly publicized.

Speaking with Reduxx, UK-based journalist and women’s rights campaigner Jo Bartosch criticized the media outlets who chose to reference Gray’s genitals using feminine pronouns, and highlighted the significance of factually-based language.

“Whether it’s calling a man ‘Miss’ or using the oxymoronic phrase ‘her penis,’ these linguistic capitulations to men’s paraphilias are dangerous. It is a public sign of the power men like Gray enjoy. And it is terrifying, yet darkly comic, that respected journalists and broadcasters will now lie in this way, because to do otherwise is to risk breaching media guidelines which have been informed by trans lobby groups,” Bartosch said.

“The phrase ‘her penis’ is an insult to the profession, to audiences and to the truth,” she added.

Bartosch explained that she views pornography as an influential force in the concept of a “female penis,” noting that while it may seem bizarre to “the uninitiated,” there exists within the “male domain of pornography a logic to the idea of a ‘female penis.'”

She then cited as examples genres such as forced feminization, and sissification, which portray men as being transformed into women through processes that involve makeup, lingerie, sexual submissiveness, and humiliation.

“Whether it’s the rebranding of sexual entertainment as ‘children’s education’ or the use of language to reflect men’s fantasies; aggressively male behaviour which festers in online pornography has seeped over into the real world,” Bartosch stated.

“The excitement men feel is because they know that the social bounds that keep their base impulses in check are straining and being broken, and that it is happening in plain sight. Pornographic values have become so mainstream when men brazenly flash their fetishes they are celebrated for their bravery. One wonders which taboos will be the next to be broken?”

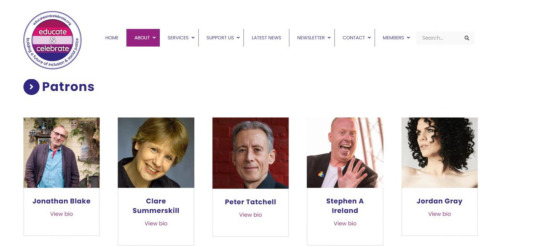

In the days following Channel 4’s broadcast, internet sleuths have brought to light how Gray boasted about being a representative for a charity that promotes gender identity ideology in schools. The charity, Educate and Celebrate, describes its

programs as offering “the knowledge, skills and confidence to embed gender, gender identity and sexual orientation into the fabric of your organization”.

Since news of his involvement with the charity has been spread on social media, Educate and Celebrate quietly pulled a page from their site that listed Gray as a patron. “I go into schools to talk about gender as part of a campaign called Educate and Celebrate,” Gray told GuysLikeU.

“Toddlers kind of get it straightaway. I went into one school recently where there was a 7 year-old transgender girl. And her four year-old classmate, who was a boy, said: ‘Jessie’s a girl and she wants to be a girl. And I am a boy who wants to be a boy.'”

“Young minds are very accepting,” Gray added. “It’s teenagers who are harder to get through to. It’s good to educate these kids when they are young.”

A patron of Educate and Celebrate listed alongside Gray, Peter Tatchell, has previously made statements in support of pedophilia and questioning age of consent laws. Tatchell, a former leader of the Gay Liberation Front, authored an obituary in The Independent for Ian Dunn, founder of the former pedophile activist organization the Pedophile Information Exchange (PIE).

Tatchell also published an essay in an anthology released by former vice-chairman of PIE, Warren Middleton, wherein he argued that argued that “children have sexual desires at an early age” and should be “educated” so that they can decide when they want to have sex.

“While it may be impossible to condone pedophilia, it is time society acknowledged the truth that not all sex involving children is unwanted, abusive, and harmful,” Tatchell wrote in a letter to The Guardian in 1997.

The revelation that Jordan Gray worked alongside Peter Tatchell for a charity promoting the notion of a gender identity to young children mirrors a recent, widely-publicized scandal involving a pro-pedophilia campaigner’s ties to a children’s charity that promotes the medical “transition” of minors.

Earlier this month, Jacob Breslow, an Associate Professor at the London School of Economics, stepped down from his position as a trustee for UK-based trans activist organization Mermaids following revelations that he had ties to pro-pedophilia lobbyists.

Breslow had, on several occasions, made statements and published academic work that favorably portrayed pedophilia, and had once authored a blog that linked directly to child sexual abuse materials.

ByYuliah Amla

A man thinking he’s better than women and then thinking people want to see his penis

160 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LGBTQIA+ Historical Romance Novels with...Favorite Authors

If you’ve followed the blog any length of time at all, you know I make lists based on themes, the one unifying factor being LGBTQIA+ representation that happens in historical romances. I started reading historicals when I was in middle school, because my grandmother and great-aunt would trade them with one another, and back then they were usually low on heat level. I went on to collect them myself, and still have most of those in storage, but left off for various reasons over time.

By the time I came back to it all, I’d reached well into adulthood, and had gone from thinking of myself as a female with tomboy issues to realizing I was non-binary and graysexual. I didn’t feel represented by any of the main characters in those romances I’d once read so avidly, but I still wanted history with a romantic twist. So, I started exploring.

What fits me, won’t of course fit everyone, but I’d like to recommend some of my favorite LGBTQIA+ historical romance authors that I haven’t seen on similar lists in the past, and authors I’m hoping to see more from soon...Maybe it will add to readers’ TBR lists...

Alex Beecroft - I honestly have no idea why Beecroft doesn’t make more Best Of lists. The broad range of her novel settings (from ancient Crete to 18th century Transylvania to Regency ships), the amount of research, character development, and evocative language, makes her one of my favorites. I don’t think there is anything she couldn’t write about, and do it well. For those interested, she also writes contemporaries, and fantasy. My favorites are The Reluctant Berserker (role reversals from the typical warrior and bard combo), and Labyrinth (non-binary MC and a twist on an old myth).

Erastes - One of the first LGBT historical romance authors I found, this author got started by writing Harry Potter slash fiction. Favorite by this author is Muffled Drum, because it’s a lovers-to-friends-to-lovers plotline.

Ainsley Gray - This author normally publishes under other names, but their recently released Unchained came to my attention, and kept it. If you like your Victorian romances with a darker twist, this one is for you. Hoping to see more from Gray, soon.

Eliot Greyson - I know next to nothing about this author, but their Like a Gentleman (Love in Portstmouth #1) put them on my One-to Watch radar. It’s actually a novella, but packs a lot into those few pages, and makes for an adorable read.

Jude Lucens - Lucens is new on the LGBT historical romance scene, but has already managed to give the genre representation in the forms of gay, bisexual, demisexual, and polyamorous MCs. She’s also a WOC author, and has included a biracial MC in her novella/novel pairing of Gutter Roses & Behind Closed Doors: Indecent Proposals Book One.

Katherine Marlowe - I don’t know what happened to Marlowe, but after several lovely novels, she disappeared. Still, her novels are ideal for those that like low dose homophobia in their historical romances, enjoy novels with working class MCs, and she has at least two novels with POC MCs. Favorites: A Wager of Love & The Blue Ribbon.

Farah Mendlesohn - Normally an author of fantasy and science fiction (they’ve won the coveted Hugo Award), this versatile author transported us to the Regency era with some wonderful historical detail, in the delightful and affordable f/f Spring Flowering. They are also the Managing Editor for Manifold Press, which will be returning this January, with a focus on LGBT historical romances.

KA Merikan - The pen name of a duo, their highwayman novel The Black Sheep and the Rotten Apple is one of my favorite bad boy/cinnamon roll novels ever. This pair typically writes contemporary series with motorcycle gangs, but even then they manage to bring historical ghosts and details, with their series Kings of Hell MC. The Art of Mutual Pleasure is another historical, which will amuse and educate, because it deals with the historically accurate notion of illness being brought on by the loss of male essence, and aggravated by self pollution.

Ruby Moone - If Moone writes it, I read it. Moone’s gents tend to reside in the Regency era, and have been adapting in terms of historical elements and diversity. They were some of the first non-titled MCs I read, and some have disabilities and/or cope with mental illnesses. The plots have increased in tension over time, but a mainstay of Moone’s novels is that despite laws against men being together, her MCs are often supported by those around them. There are also sometimes multiple Favorites: The Wrong Kind of Angel, The Mistletoe Kiss, & Thief of Hearts

Niamh Murphy - Looking for lesbian historicals? Murphy has you covered, with loving details, and also high adventure. Her Escape to Pirate Island is a staple of the LGBT pirate genre, and you can read a free sample on her site.

Victoria Sue - Typically Sue is known for contemporary novels and babies. That said, her Regency novels The Innocent Auction and The Innocent Betrayal are two you should try. They’ve a fair dose of angst, but they also come with some good espionage and character development.

Hayden Thorne - If YA and gothic are something you’re into, Thorne’s novels are a staple. An extremely prolific writer, she has created some of the most unique plot lines of any genre, while managing to have intriguing MCs, and representation. Favorites: Ansel of Pryor House

Leandra Vane - Normally a contemporary author and librian, Vane recently published the great historical Cast From the Earth, which takes place in America’s heartland in the 19th century. Vane is another author that uses her novels to explore with MCs that have disabilities, and this novel also delves into polyamorous love.

NR Walker - Walker is actually known for her contemporary m/m romances, and is one of the rare temp authors that I read a lot, because she includes so much research and detail. Recently, she made the leap into historicals though, with the fantastic Nova Praetorian, which takes place in ancient Rome.

Kelley York - In the past, some of you may have read York’s contemporary YA work, but she’s begun publishing about her beloved Victorian era gothic tastes, too. The Dark is the Night series is co-written with her wife, and I’ve been relishing the two novels that have come out so far. It even comes with its own artwork, and playlist.

Of course, there are the mainstays of the genre, authors that have gone above and beyond on bringing LGBTQIA+ representation to the historical romance reader: Keira Andrews, Joanna Chambers, KJ Charles, Charlie Cochrane, Bonnie Dee, Summer Devon, Jordan L Hawk, Ava March, EE Ottoman, and Cat Sebastian.

#lgbt romance#historical romance#m/m romance#f/f romance#poly romance#two men in love#two women in love

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m thankful for TV!

I don’t care about Thanksgiving, but I love TV! So here is a quick list of some fave Thanksgiving episodes of television to check out, by alphabetical order of the show. I’ve also written down which streaming service you can find it on in the US!

Bob’s Burgers

Every season since season 3 has had a Thanksgiving episode, and they are some of the best ones out there. My top picks are “An Indecent Thanksgiving Proposal”, which was their first Thanksgiving episode, and “Dawn of the Peck”. Both have classic Bob break downs, fun plots for the kids, and lots of great work! (Hulu)

Brooklyn Nine-Nine

Another show with plenty to choose from, but I have to say that my favorite is “Thanksgiving” from the very first season. Super cute and heart warming. (Hulu)

Cheers

"Thanksgiving Orphans” from season five is considered one of the best episodes of television, period. From the improvised food fight to the closet we get to seeing Vera, it definitely deserves to be ranked as a classic episode of one of the most beloved sitcoms. (Netflix and Hulu)

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Want something completely different? Check out “My First Thanksgiving With Josh!” in season one. Who doesn’t love musical parodies of Nicki Minaj and Billy Joel? (Netflix)

Frasier

Season four’s “A Lilith Thanksgiving” is one of Lilith’s guest appearances so it’s automatically one of the series’ best. (Netflix and Hulu)

Friends

Say what you want about the show, but only Bob’s Burgers can compete with it in terms of great Thanksgiving episodes. I personally enjoy all of them, but my top picks are “The One With All the Thanksgivings” (s5) or “The One Where Ross Got High” (s6), which includes one of the best 30 second sequences in television history. (Netflix)

How I Met Your Mother

Not only does s3′s “Slapsgiving” give us a great original song from the show’s prime, it also introduced one of the best running jokes - Ted and Robin’s inside joke of saluting at things like “General Idea”, “Major Buzzkill”, etc. (Hulu)

King of the Hill

"Spin the Choice” from s5 is an absolute RIOT. Lots of cute moments with John Redcorn and a development of his relationship with his son, Joseph. Also, Bobby takes things too far and let’s not forget Peggy’s amazing game that makes the title of the episode. Runner up would be “Happy Hanks Giving” from s4, which is quite a treat if you’ve ever experienced being stuck in an airport. (Hulu - FINALLY!!!)

New Girl

"Parents” from season 2 features both Rob Reiner and Jamie Lee Curtis as Jess’ parents whom she is trying to “parent trap”. Super fun, super cute. (Netflix)

Supergirl

"Livewire” is from season one, which is the only season I acknowledge of this show. It introduced one of the coolest villains the show had and is super fun! (Netflix)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 15: Tale of Two Bots

-date: 13/20/2094-46’\

Hello.

My name is Ɖg@}Nᶌ.

As one of the survivors of the crash of colonial vessel 46.18’\, I am starting this journal to document our experiences on this planet. In the event that we are rescued, or survive long enough to reestablish contact, this log will serve as a record on our experiences. If you recover this and we’re not here to give it to you… Then I guess we’ve failed.

And this is our story.

Well.

As I said, the colonial vessel has crashed. Near as I can tell, we were traveling near-horizontally at an altitude of several kilometers, when some type of interference or malfunction disabled the vehicles artificial-gravity engines. We hit the ground before control could be regained. The impact was directly into solid rock, at a velocity in excess of 400 meters per second. The ship carved a large chunk out of a mountainside, and half-buried itself in its own artificial valley. The impact was sufficient to free the majority of the nuclear fuel from containment, disable the primary propulsion system, and kill the entire pilot and command crew. To the best of my knowledge, I, and 52 other passengers, are the last survivors of the collision.

We have escaped the confines of the ship, and have used salvaged tarps and materials to erect a small camp on the hill above it.

More of us are injured than not. Many terminally so. Since the vessel’s power supply has largely gone into meltdown, all remaining power has been automatically diverted toward containing the damage. Periphery systems, including the auto-medics, have gone offline. I’m no surgeon, but the others are even less so.

They expect me to repair the wounded.

I’ll see what I can do.

-date: 13/21/2094-46’\

My medical tools were designed for my species specifically. They are poorly suited for the others, who are primarily carbon-based. Their bodies are squishy, ever-shifting, mostly liquid. I don’t know how to handle it. Many of the terminally injured have died following my surgery. I was able to fix a few, but… But the others are angry with me. They think I could have done more for the dying. Survivor count now 41. The names of the living are included here for posterity:

Ɖg@}Nᶌ

Klk76y

Zlfo]n

ƉN::ᶌ

&4r(/_^`;~y

iA**5{y

-@N^^>

C0gsJRY

V;M9OZ

4EtR%ibP

WA~/\hi(B

~u81FF:’

S~5VH/’QepKl

3v49EVv

iZxFpLo

wX~~E2VY

IeR&Usp

xE][fo

I6gyvPh

7ncZ9Itx

bC*$l9DSEmm

J86O/\oBZg

v89Z;vHFiv

4g0ORH

Xp;DWstNBYi

0aF2I(zLxyn7k

SGff\mBOfic8

0Xzn

TSpqQfjFn

famESw

W8{A1EdwQ

j0wX

KlcfG;B0lw0

4hArMXj4

qKhcn0U

SXz4;

PxNeLwi

w4A;mVIV5

tVkqZme

oy.}szN;XJCc

og;hgnC5j8Ca…

I don’t really want to talk about it anymore.

-date: 13/22/2094-46’\

Only one other survivor belongs to my same species. We were bound for the same colony, her and I, but now everybody we knew is gone. I’m glad I have somebody to speak to though, especially after the failed surgeries. Her name is ƉN::ᶌ, and she is kind to me. Seeing as how it looks like we’re here for the long haul, I wonder if perhaps we could begin the colony here, with only us two.

No, I can’t think that. It’s indecent.

She’s looking at me.

I am pretending to type something in.

-date: 13/28/2094-46’\

Klk76y has gotten one of the computers online, and has retrieved data from the crash. Apparently, we are on body 3.0 of this system, on one of the northern continents. It’s hellish here. There’s air, it’s hot, the gravity is high, the surface is soaked in unhealthy chemicals like water, and infested by native (and occasionally hostile) carbon-based life. Even its moon, 3.1, would have been better than this. We can survive, but it isn’t well-suited. Natural terraforming processes won’t work.

I just wish we would have crashed on 4.0. It would have been nearly perfect for our needs.

The only metal ƉN::ᶌ and I have to eat is that from the ship’s hull. Livestock and crops could easily survive on this diet, but they would rip the whole craft apart in the process. Since we’d rather leave it salvageable (by the slim hope that we could repair it someday), we’ll keep the farming systems in stasis for now.

I hope our colonial supplies are still intact. They should be tougher than the other cargo, but I don’t know.

Titanium-steel alloy plating is sure getting bland though. Hard to chew. Hard in general.

I want some fruit.

-date: 13/22/2094-46’\

Everything has calmed down now, as much as it can. The fires from the crash have died out. We’ve buried as many of the dead as we can find. The other survivors are settling into the camp, and they’ve gathered some meager supplies, enough to last the winter. ƉN::ᶌ and I can survive directly off the ship’s power, so we should be fine indefinitely. Klk76y has also taken charge as a sort of leader, and everybody seems as content as they can be.

I suppose that now is a good a time as any to give my own personal story.

It all started long ago, and far away.

It was cold and hard and small, one of many solitary, airless moon of a bloated gas giant, bathed in the light of an old, red star. To look at it, you might mistake it for a larger asteroid, or one of the many unnotable, dusty rocks that inhabit the empty voids of space.

But this rock wasn’t any rock. This was a living place, filled with rugged natural beauty. Spreading seas of liquid sand, mountains of the dust of ancient timbers, and the great, towering forests of mighty trees. Fields abounding in fruits and grains, the woods crawling with wild animals, the void alive with the radio singing of the bugs and the birds, the sun shining brightly on the leaves. And a humble people toiling with bliss beneath the stars, picking and eating their food, building their houses and roads, constructing and raising their children. It was a place where families could be happy. A place of peace.

This was my beloved home.

But I never once enjoyed it.

Why didn’t I? It was a paradise. I could have grown old and happy there. I could have been rich and prosperous. I could have had everything that people strive for… Everything but meaning.

Mind you, I wasn’t alone. There were many of my peers who considered it an utterly boring, menial existence, where our young minds had nowhere to explore, where knowledge and learning was scarce, and where our toil and daily labor did not satisfy our hunger for adventure. We were children then, restlessly longing for something more. I wish now I hadn’t been among them… But I was.

Two cycles ago, when I had just finished being a boy, but didn’t yet know what ‘man’ was, another race came to our world. They arrived in an enormous ship from some other dimension, on a mission (so they said) to explore and archive the wonders of the universe, to seek out new and deviant life, to see, hear, touch and explore that which nobody had ever experienced before, and to set up colonies among the far reaches of space. They visited us for this same reason, collecting samples from our planet, examining and studying us. (The reason for their fascination, I found out later, was our metallic bodies and mechanical makeup. Apparently, it’s something of a novelty to these squishy carbon-based people.)

Regardless, I’m sure you can understand my thoughts when they revealed this mission of theirs. How glamorous! How grand! How adventurous! How meaningful! I dreamed to accompany them, to whatever fate lay beyond the horizons of my own mind. Once, I even had the chance to speak directly withCaptain &:V->GN[], commander of the alien vessel.

“I wish I could accompany you!” I had told him. “I wish I could count myself among the colonists on your ship.”

“It’s certainly a hard life.” He had tempted me, with a twinkle in his eye. “Long years aboard a closed metal ship, and at the end of your journey, an unknown fate… It could be dangerous, it could be strange, it could require things from you that you don’t know you had. Even WE don’t know what we’ll find in that great unknown…”

He was telling me precisely the type of tale I wanted to hear, and naturally I fell for it. “I would be willing!” I told him. “And I have friends as well! We would all love to leave our world, and travel with you to the ends of the universe! We would follow you!”

He stroked his chin, and nodded. “We have set down several colonies already…” He said, as if it were my idea the entire time. “Perhaps there would be room among the organic cargo sectors for your… Particular breed of crops and livestock…”

“I hope so!” I said, and I meant it.

The next day, he announced to our people that they would be taking on passengers and cargo, whatever passengers could fit in sector 22, and whatever farming supplies we could fit in stasis in sector 43. They would allow our people to found a colony on a world of our choosing, or even, if we wished, they would allow us to return with them to their home dimension.

It goes without saying that I, along with many of my friends, signed up eagerly.

My father silently watched me as I entered the shuttle, and he had a sorrowful look on his face which I will never remember, because I never once looked back.

And so did I venture forth, to seek my fortune among the stars.

It was a lie.

No sooner had we left the system, but the crew confined us to quarters, and began to treat us harshly. They told us they were cracking down on troublemakers, and that this was just a necessary caution. But among themselves, they were communicating using their suits’ radios. My people could hear such signals plainly, and I learned to understand them.

I learned that our people were not to be set down on a colony of our choosing. Rather, we were all to be brought back to the aliens’ dimension, to be treated as scientific samples, or even used for their own purposes.

They began to experiment on us.

It was a nightmare.

I would hear the communications as they would take our people, one at a time, from the passenger areas. Always young females. Whenever the rest of us moved to intervene, the crew would summon security drones to threaten us, then say it was for our own protection.

One day we heard their purpose… Well, I feel dirty even describing it.

The females of our species naturally have reproductive systems in their abdomen areas. Normally, these organs serve only to manufacture and assemble the bodies of children. The organs are perfectly designed for the task, and they are able to do so reliably and repeatedly. Since the living bodies of children are inherently complex, the organs must be highly versatile.

The aliens saw this.

So the science team, under the direction of Captain &:V->GN[], were downloading foreign code into the women’s organs, to try and make them manufacture artificial systems: Tools. Weapons. Drones. Storage crates. Spare parts. They were trying to turn our people into living factories. This was just a proof of concept, before they returned to their home dimension and refined the idea into an industrial process.

The experiments were invasive and painful, and the women were not willing.

I began to discuss these matters in hushed tones with the other colonists, of both my own species and others. We all agreed that something needed to be done.

So one night, all at once, we staged a mutiny. We sawed through the doors of our rooms, gathered improvised tools and weapons, rendezvoused with the organic passengers, and aimed ourselves for the bridge.

It didn’t work.

They put us under guard from that point on, reinforced the doors, equipped us with stun collars, and pumped all the air out of our rooms to keep us from audio communication with the other passengers. They also encrypted their radio signals, so we could no longer listen in to them.

A cycle passed quietly and despairingly. An older friend of mine likened it to prison.

But then, days ago, it happened.

For reasons none of us know, Colonial Vessel 46.18’\ crashed.

Now here we are. The greatest adventure of my life, more excitement and strange new weirdness than I ever could have hoped or dreamed: aliens, lies, betrayal, mutiny, heroism, bravery, fierce enemies on all sides and a grave mission to follow… This is the adventure of a lifetime.

And I would trade it all away in an instant. What I wouldn’t give to be back home. My quiet, peaceful, meaningless home…

For there is no meaning to be found out here either. We’ve crossed galaxies by now, gone where none have gone, and we are no closer to something higher than when we started out. There is no height to be climbed to reach enlightenment. There is no lesson or sense or justice to bring to our predicament. Life is cruel and short, and our lives are either empty or painful. Some, like mine, are both.

So that is how I, Ɖg@}Nᶌ, got to where I am now.

ƉN::ᶌ says I’m being pessimistic. She says there is a meaning, and that God has a purpose and plan for our lives, even through our pain and misfortune, even though we do not see it.

I hope she’s right.

I prayed for the first time today.

-date: 13/30/2094-46’\

Why are we on this planet at all? Why did the command crew stop here? Did they have to land to make repairs? Did we have to restock supplies? Was there another mutiny we didn’t hear about?

I, for one, suspected the command crew was goaded into it by the science team. They noticed something interesting on the flyby, and convinced the higher-ups of the need to stop and release probes.

It wouldn’t be the first time it’s happened. We’ve had several unscheduled stops over the course of this trip. Always the science team wanting to collect samples or specimens, or examine some readings. Always something new and interesting to look at.

But why here? What makes this valley so special? What drew their curiosity? And what about this valley caused our crash? We may never know; all the sensors are down, many of the computer logs were damaged, and many of the remaining mission files are simply classified to us passengers.

I suppose I’m just complaining. I shouldn’t complain. What’s done is done, and now all we can do is pick up the pieces and make the most of what we have left.

Perhaps it’s just God’s will.

-date: 15/2/2094-46’\

We sent 5 men deeper into the wreck to see what they could salvage. It’s been 6 days now, and they haven’t come back out. I wonder what has happened. The automated security system is coded for all the colonists’ identities, so even if it reactivated somehow, none of them should have anything to fear… I wonder if perhaps some of the more dangerous scientific specimens have been released from containment.

The rest of the survivors are wanting me and ƉN::ᶌ to venture in after them, since our metal bodies make us tougher than the others.

She is afraid, so I will go in alone. I will be their hero. I will be her hero.

-date: 15/3/2094-46’\

I’m back. I found nothing. No signs of a struggle, no weapon damage.

But no bodies either.

Perhaps they got lost down there. I can see why they would; the crash mutilated the vessel into a veritable labyrinth of twisted metal. We can only wait, and hope that that they survive, and hope still that they can find their way back out.

While I was down there, I did stumble across the scientific sample area. It was torn wide open. Everything in the stasis chambers are dead.

But a few of the chambers are open.

And all the chambers that are open are empty.

Specimens must have escaped. Could one have killed and eaten the men we sent inside? I don’t know what manner of subjects they’d stored in the now-empty chambers, but judging by the looks of some of the others… Let’s just say I’m glad most of them are dead. Out of all the nasty things they’ve collected on their journey, I think that living robots are the most harmless of the bunch.

I’m back on the surface now, and gave my report to the other survivors. It frightened them. They don’t want to explore the wreck any deeper than necessary. I understand that.

ƉN::ᶌ is beating herself up for letting me go alone. She swears that whatever happens next, she will be there for me. I’m glad for the promise.

As it stands, Survivor count now 36.

-date: 15/16/2094-46’\

Survivor count now 28.

We don’t know what’s happening. People go missing. Randomly. Unforeseeably. Without trace. As if they decided to just walk away in those moments when nobody’s watching.

After the last incident, Zlfo]n instructed us to watch closely for anyone behaving strangely. He encouraged us to keep up conversation frequently. I don’t know what he suspects, (does he think we’re going mad one by one? Does he know something we don’t?) but I hope he’s on to something.

I modified a few power tools into melee weapons, so that ƉN::ᶌ and I can defend ourselves if the need arises. When I offered her a cutting drill, she said she would prefer to use her teeth, since they’re sharper and easier to carry around anyway.

It’s nice to have somebody to laugh with, even in times like this.

But seriously though, she’s literally going to use her teeth. This girl is crazy!

I kind of… Never mind.

-date: 15/18/2094-46’\

Somebody struck up conversation today with Klk76y. He mumbled his way through a brief exchange, but in the process, he gave something away: he didn’t possess even the most basic knowledge of Klk76y’s life or job. It quickly became apparent that he wasn’t Klk76y at all, but rather something else, looking exactly like him, bluffing his way through a conversation. Zlfo]n, ƉN::ᶌ, and myself attempted to confront him, but he attacked with an incredible physical strength, and escaped into the forest. Zlfo]n suffered several broken bones during the fight, and will not last long. Meanwhile Klk76y, the only leader we had, is gone like the others.

Also, at some point, ƉN::ᶌ managed to clip the enemy with her teeth. This drew green blood, whereas the real Klk76y would have had yellow-white blood.

Something is out there.

Something that’s changing.

It takes us one by one, probably eats us, and impersonates us to learn more before eating again.

Survivor count now 27. Soon to be 26, as there’s not much I can do for Zlfo]n.

-date: 15/19/2094-46’\

Zlfo]n pulled me close today, and told me about the shapeshifter. He described everything he knew of its abilities, its methods, its mannerisms, and its intelligence. He told me where the science team found it, what it eats, where it lives, what it wants.

(Future reader, I have transcribed his analysis, and saved it as a separate file. This is my journal, after all, and not a tactics guide. Suffice to say that this shifter is quite a character herself, and I don’t like it one bit being on the receiving end of her cunning.)

I asked Zlfo]n how he knew so much about the creature. He sighed and he told me:

Zlfo]n was on the science team.

So I took him outside the camp, and I left him to die. By now he will have perished from his injuries in the silent forest, without burial, without dignity, alone except for the memories of the women he violated. Alone, save for his conscience. I hope he has one, so that he suffered. And I hope the shifter finds him, and that she realizes we are not her enemies.

…Did I do wrong, to let Zlfo]n die like that?

I don’t think I did.

Did he deserve better?

I don’t think he did.

Did ƉN::ᶌ approve?

I think she did.

I never asked her if she’d been a part of the onboard experiments. I pray she didn’t have to suffer it, because I don’t know what I could do for her damage. I’m not that type of doctor. Heck, I’m not any type of doctor! What am I supposed to do for a damaged factory, huh? Look at it? I’m a male. Even that’s not proper.

All I can do for her is to be her friend, and love and respect and care for her regardless of anything else. And I really do love her… I’ve been realizing that more and more.

-date: 15/27/2094-46’\

Survivor count now 23.

The other survivors can’t stand it anymore. They need to get away from the wreck. Whatever the shifter wants, it is hostile. And it is near. And since we haven’t the vaguest inkling of how to face it, we need to flee.

They others all agreed to pick up and head North, as far from the crash site as possible. They are carbon-based, and can therefore subsist on native food. They collected all the weapons and tools they could find, and started off. They should be safe from the enemy… Or at least see it coming… I think they’ll be alright. I hope they’ll be alright.

Either way, ƉN::ᶌ and I need to make other plans. We are not carbon based, and therefore need to grow our own crops if we are to survive. We’ll need a farm. We picked out a pretty good spot for it to the South-East, but this planet doesn’t have a lot of dense deposits near the surface, so our crops won’t grow.

We’ll need to improvise some type of soil.

The hull of the spacecraft, combined with the minerals in the native rock, should supply our farm with all the biological sustenance it needs. It would make excellent soil. But we don’t want to stay in the craft’s immediate vicinity, so we need to somehow cut loose a massive section of the hull and bring it all of 20 kilometers to the farm.

How do we do that?

It was her idea to jury-rig the ship’s last remaining artificial-gravity nacelle. Normally, these nacelles create a gravitational dipole large enough to put the entire ship into free-fall in any direction. One nacelle may not be able to do something so grand on its own, but it still possesses a large amount of power. ƉN::ᶌ thinks it should be a simple matter to shrink this dipole and concentrate it, if only we could get to the engine room. This would allow us to ‘jackhammer’ a section of the hull loose. A slightly larger dipole will then be able to carry the disconnected section 20 kilometers through the air, and set it down at the farm. I just hope the craft has enough power left to run this stunt.

To operate the nacelle, we need to get down to the engine room and do it manually. This means risking whatever tricks and tactics the mimic has in store, but we would prefer to risk it immediately, rather than stay above ground and wait for her… Rather take her on our terms: immediately and directly.

We’re going inside tomorrow.

If we never come back out… Let it be known that ƉN::ᶌ and Ɖg@}Nᶌ were here.

-date: 15/30/2094-46’\

It has been 3 days since my last entry, but we are now back. We successfully completed the mission.

But first, a word on what we found down there.

Let’s just say that at this point, the ship would need half again its weight in glue. Its main propulsion system, (everything except the one intact nacelle), is completely offline. 7 of the 8 main reactors have also gone into meltdown, and the computer automatically locked down the last one for safety. The vessel’s long-range communication systems and tracking beacon were in its lower areas, and were therefore destroyed when it contacted the ground. There is no chance of signaling home, or anywhere.

However, there were a few intact things. The perpetual-motive emergency power generators were left online somehow, and should stay remain so indefinitely, barring mechanical breakdown. These were the only thing running the ship until we got down there.

Also, we found we weren’t the only survivors. There were more, some even among the command crew, who had survived the crash but stayed underground. They were barricaded in the ship’s mid levels, and just stayed down there.

But they aren’t alive anymore.

Apparently, the mimic got to them too. Some of their survivors had taken to drawing graffiti on the walls since the computers were down. Most of it was just innocent nonsense, but then there was some stuff like “GweeV7w isn’t what he seems!” and “That’s not the real u*/~h!” and “Specimen has escaped is changing forms.”

And everybody was dead.

Eaten.

The mimic is smart. Smart enough to kill them all without putting itself in danger. Smart enough to use fear like a weapon, and fill her enemies with it. Smart enough to stay in shadows.

Smart enough to learn to hack computers.

The mimic has reactivated the security system, and made several changes to their programming. Firstly, she wiped the drones’ entries for recognized individuals, so that they now recognize everyone, every last man, woman, child and animal, as unidentified intruders. Secondly, she reprogrammed their tactical assessment system, so that they now evaluate threats based on chemical signs of aggression and fear. If any carbon-based lifeform shows fear in a drone’s vicinity, it is programmed to contain or destroy them.

Since the shifter was terrorizing everyone else while remaining calm herself, it worked perfectly: the drones would leave her alone and go straight for any of the other cowering survivors.

As for us metallic life forms, well… The mimic is smart, as I said. She knew we didn’t have a sense of smell, so she rigged a booby trap that sprayed us with hormones. We didn’t even notice, until every drone in the ship started to attack.

That was a dicey couple hours. Those drones are learning and self-adapting, and can sprout pretty much any weapon in the database. We managed to beat them, barely, by modifying one of the perpetual-motive generators into an electromagnetic pulse emitter. We almost killed ourselves with it too, but it took out most of the drones. Enough so we could slip away.

I don’t know that I’ve ever been more scared in my life than when I was down there… But… I think I might have been having fun too. Crazy how that works. It probably just depends who you have by your side in the thick of things, doesn’t it? And while we were fighting down in those dark depths, I had ƉN::ᶌ. And that made it all right.

Anyway, we made it to the engine room, and ƉN::ᶌ managed to bypass a security lock and reactivate reactor 5. From there, she was able to reprogram the art-grav nacelle, and use the immense gravity field to rip apart the hull.

We tore off half of the ship’s upper hull, along with the entirety of sector 43 (sector 43 being the cargo area where all the samples, livestock and crops from our planet were stored.) The gravity field gathered all this wreckage together, forming an enormous ‘fistfull’ of twisted metal and cargo. ƉN::ᶌ then used the gravity beam to guide this mass through the air to the farmland we designated, and spread it out there. The entire process must have been rather eerie to watch, I imagine.

There was only one problem now: if we could make use of those gravity fields, chances are the mimic could too. If she set the field to a high strength and low size, she could use it to physically crush our entire farm, with us inside.

With that kind of power, the mimic could kill anybody she wanted. And anywhere.

So, we removed the power control coupling from the last reactor, and destroyed all the spares. The coupling is small. Small enough to take with us, and keep hidden forever. So that’s what we’ll do.

We made back above ground without much trouble.

Now, everything seems in order. The livestock and seeds will be waiting for us in sector 43’s wreckage, ready to be unpacked, unfrozen, and organized into a farm. A colony. First thing tomorrow morning, we’re off to begin our new life.

-date: 3/14/2096-46’\

Two local years since my last entry.

Farm is going great. Got some trees planted, and some crops. The ecosystem is starting up, and the drilling worms have started breaking down the spacecraft hull. The cats are working as guards, which should be enough to scare away the mimic if she finds us here. I tampered with the cats’ genetics as well, to make them instinctively react defensively toward any unrecognized large organic. Meaning whatever form the mimic takes, the cats will turn on it. I’m just glad this planet doesn’t have intelligent inhabitants; that could make for a rather messy misunderstanding.

I also found an old runabout shuttle stashed in the wreckage. We turned it right-side-up, half-buried it in the ground, and are now using it as a house. Its glass hull should keep it from decay, and its engines still have enough power to run heat, lighting, and farm equipment.

The place is finally starting to feel like home. The trees are supplying power now, so we don’t have to ration anymore. And they’re beginning to bear the first fruit. We haven’t had actual food in so long, and it’s delicious.

And… Well, there’s one other thing. I don’t really know who else to tell, so I guess I’ll tell this journal.

Anyway…

I finally asked ƉN::ᶌ if she would be my wife. And she said yes. I’m not really sure what I expected her to say, since we’re the only two here… But it was the WAY she said it; it made me believe that she would have chosen me out of a crowd. Like I would have been her first choice out of all the men on all the worlds. She said yes… And I’m a married man now! I’m really happy. I really love her. I’m really glad to be alive.

That probably sounded super corny, huh?

-date: 8/9/2098-46’\

Three local years since my last entry.

We lost contact with the other survivors. I don’t know what happened to them. Maybe it was local wildlife or sickness, maybe it was the mimic again, maybe something else. Anyway, let it be known that this farm contains, to my knowledge, the last 3 survivors of the crash.

3 survivors?

That’s what I said.

Because ƉN::ᶌ is pregnant.

I’m gonna be a dad.

Speaking of dad…

If this recording somehow gets to you, mom and dad… If the fabeled Time Giants ever find this log in the far future, and decide to do a favor for my present, and bring it back to you… If you’re reading this now in the comfort of your own home after I’ve left…

I want you to know that I’ve finally found that life I always dreamed of. There’s a little bit of adventure here and there, sure. (This planet seems to harbor some very improbable life. We’re always finding ourselves in some weird situation or another.) But most of all, I’ve found home. I’ve found love. I’ve found peace. And I think… With the help of God, I’ve found a bit of meaning. Here, in a filthy, watery world at the end of the universe. Here, in the valley carved by the crash of colonial vessel 46.18’/. Here, where nobody else has ever been, is where I’ve decided to stay. And here, I am happy. I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

-date: 16/13/2098-46’\

There was a fault in ƉN::ᶌ’s manufacturing system. The child was damaged during final assembly, and… I’m not sure what happened. There was a problem with the release, and something snapped. There were sparks, and leaking oil.

And she died.

Her and the baby.

I made glass coffins so they wouldn’t decay. And I buried them behind the house.

I guess that’s it then, huh?

So much for our life. So much for our colony, and our future, and our children, and our love… So much for all that. Whoever’s reading this, I’d dreamed that one day we would have healthy, happy descendants who’d be able to hand this to you. And they’d say ‘Take this. This is their legacy…’

But what good are dreams?

Dreams are for young men… And today I feel old.

Anyway… If you’re reading this journal, then… Then I guess I’m long dead. The barn and the tractor and the windmill will have been eaten all away by now… Only the glass shuttle-house thing will remain; that and the coffins… Give it long enough, and the farm will probably grow all over the place… The drilling worms and trees will have digested the last of the hull wreckage we drug out here… That will make for the only soil on all of 3.0 that can support metal life, so the little forest will have reached a maximum size and stopped growing. Due to the atmosphere, the crops can’t spread seeds far enough to fertilize on the main wreck, and even the cats don’t explore very far. So. By now all the livestock will be all feral, all the trees will be huge… It will all be totally natural. Just like God intended.

It’ll be a little tiny drop of home, right in the middle of all this carbon slime. A tiny drop of home…

And that’ll be our legacy.

I’m locking the house up now, and I’m leaving.

I’m going back to the crash site. I go to find our last and greatest enemy, the mimic, and kill her. I go to ensure the safety of anybody who may come to this planet after us. I go in the name of peace. One final battle. One final adventure.

This is Ɖg@}Nᶌ, last survivor of the crash of Colonial Vessel 46.18’\, furthest explorer of a gentle people, last civilized lifeform on this planet, farmer and doctor and husband and father, signing out for the final time. Whoever finds this… I hope God’s plan for you is gentle. Gentler than it was for me.

May the Lord bless you and keep you.

Have a nice life.

#The Forest Of Daggers#wendip#wendy x dipper#gravity falls#scifi#shapeshifter#see you next summer#fanfiction#fanart#DAAAANG this chapter isn't even about Gravity Falls anymore#just a bunch of aliens and alien monsters and ALIEN ROBOTS#ALIEN ROBOTS ARE MY JAM and they're so cute together#Also Ɖg@}Nᶌ is basically me. If I was an alien robot. Which I am.#alien#robot

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter One: Of His Laudable Youth

Wherein is related, O Happy Audience, the tale of His Majesty's thrice-blessed life, including an account of His Majesty's rise to the Throne of Sentinel, which tale is exemplary, and mention of some of His Majesty's excellences and virtues, which are numberless.

Know, O Beloved Reader, that the lineage of our Auspicious King is both noble and royal, descending patrilinearly from Makala, from Ja-Fr, yea, even from High King Ar-Azal himself. Likewise matrilinearly his forebears are Grandees of Antiphyllos, including the meritorious Zizzeen of most august memory. Indeed, of the Grandee Zizzeen it was said by the Poet Behrouz that he was of such rectitude that, when he in error entered the Ladies' Bath-House, he forthwith put out both his eyes, lest he commit an indecency.

(As to High King Ar-Azal, the Curious Delver has but to seek out the tome "The Worthy Ar-Azal, His Deeds.")

Now when the All-Beneficent King Fahara'jad was but a Prince in Antiphyllos, on a day of days he did hunt birds in the Garden of the Grandees with his Ivory Bow, and by happenstance he saw a great Crow alight in a fig tree. And Prince Fahara'jad vowed, "By Onsi's bright blade, I shall slay me this Crow!" And he did nock an Ivory Arrow to the Ivory Bow and let fly, and lo, the Crow was taken in the eye and did die of the instant.

Then dropped from the sky a hideous Hagraven, with a cursing of curses, and the she-daemon menaced the Young Prince with unclean talons, crying, "You have slain the child of my bosom, and must die the death therefore! In sooth, I shall pluck out your eyes and partake of them like grapes!" And screaming a great scream, she clawed at the Prince's orbs of vision.

Then did a beam of golden light shine down from the heavens, and striding upon it as if upon a bright blade came down the Ever-Glorious Onsi, crying, "Hold, Creature of Evil." And he smote off the Hagraven's claws, which fell upon the ground like hail, and the she-daemon fell likewise and commenced to grovel unto the god and beg for mercy. And Onsi spake, saying, "Pleas shall avail you not, shrill virago, for you have threatened the Fateful Prince, whom it is my special care to foster and protect. For this noble stripling is the Fahara'jad whom prophesy foretells shall lead our people in the Years of Peril, and so you must needs die." And he struck off her head.

And the Prince, sore amazed, did cover both his eyes, and when he dared to look again, both god and she-daemon were gone. Thus the Prince did misdoubt his own eyes, and hurried to the Holy Temple where he related all that had occurred to the Priest of Onsi. And the Priest deemed his seeing a True Seeing. And this was the first of the Prophesies of Monarchy.

- The All-Beneficent King Fahara’jad

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#128, Surah 24

THE QURAN READ-ALONG: DAY 128

We’re in for a real treat this week fam. An-Nur (The Light) is from Medina, around 627-628 AD--a few months before or after the failed siege of the city. It has less than 70 ayat, but what it lacks in numbers it makes up for in Quality Content. We have a lot to talk about here. Mohammed’s family drama included!

In fact, we get started on that topic right away. To start us off, Mohammed offers the following:

The adulterer and the adulteress, scourge ye each one of them (with) a hundred stripes. And let not pity for the twain withhold you from obedience to Allah, if ye believe in Allah and the Last Day.

Oof! Bad! For a detailed discussion of the many accepted forms of punishment for zina, or sexual indecency, and how they came to be--including house arrest, financial punishment, death, and the corporal punishment indicated above--pls check here for fun stoning times. We have juicier topics to cover today.

No one should marry men or women found guilty of zina except fellow adulterers or idolators.

(For the record, I’m using “adultery” because it’s the nearest English equivalent, but Mohammed used zina to describe all sorts of things, not just PIV intercourse. While zina was a terrible crime that was sometimes punished by death, Mohammed said that as long as you’re a Muslim and not a polytheist, Allah will still let you into heaven even if you're guilty of it, so!)

Now then. Why are we talking about adultery today, exactly? Well, that brings us to an episode of The Prophet Mohammed Presents: All My Wives.

Let me quote from this long hadith narrated by Aisha, who at this time was around 14 years old.

Whenever Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) intended to go on a journey, he used to draw lots among his wives and would take with him the one on whom the lot had fallen. Once he drew lots when he wanted to carry out a Ghazwa [military expedition], and the lot came upon me. ... We carried on our journey, and when Allah's Apostle had finished his Ghazwa and returned and we approached Medina, Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) ordered to proceed at night. When the army was ordered to resume the homeward journey, I got up and walked on till I left the army (camp) behind. When I had answered the call of nature ... A necklace of mine made of Jaz Azfar (a kind of black bead) was broken and I looked for it and my search for it detained me.

Aisha was the wife Mohammed chose to accompany him on some exciting adventure of terrorizing Bedouin clans. She was carried around in a covered seat called a howdah (or hawdaj) on the back of a camel, which looks like this.

This is because Mohammed had ordered his wives to totally seclude themselves from men by this point, which we’ll get to later.

When their task was accomplished, the group returned home. On the way back, Aisha got up to go to the bathroom one night and lost part of her necklace. The men in charge of her camel didn’t look inside to make sure she was in the howdah (because they were not supposed to look at her), so they took off without her.

those people did not feel the lightness of the howdah while raising it up, and I was still a young lady. They drove away the camel and proceeded. Then I found my necklace after the army had gone. I came to their camp but found nobody therein so I went to the place where I used to stay, thinking that they would miss me and come back in my search.

Aisha lingered nearby, assuming that the men would realize their mistake and come back for her soon.

While I was sitting at my place, I felt sleepy and slept. Safwan ... was behind the army. He had started in the last part of the night and reached my stationing place in the morning and saw the figure of a sleeping person. He came to me and recognized me on seeing me for he used to see me before veiling. ... he made his shecamel kneel down whereupon he trod on its forelegs and I mounted it.

One of Mohammed’s soldiers, Safwan, had been separated from the rest of the troops and came upon her while she was sleeping at the campsite. He gave her a ride.

Then Safwan set out, leading the she-camel that was carrying me, till we met the army while they were resting during the hot midday. Then whoever was meant for destruction, fell in destruction, and the leader of the Ifk (false statement) was `Abdullah bin Ubai bin Salul. After this we arrived at Medina and I became ill for one month while the people were spreading the forged statements of the people of the Ifk, and I was not aware of anything thereof. But ... I was no longer receiving from Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) the same kindness as I used to receive when I fell sick. Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) would enter upon me, say a greeting and add, "How is that (lady)?" and then depart. That aroused my suspicion

She returned to Medina and fell ill, but while she was sick, schemes were afoot. The “ifk”, also known as the slander, is the topic of this part of the surah. Unbeknownst to her, some of Mohammed’s men had accused her of sleeping with Safwan the night that she was separated from the army. Aisha noticed that Mohammed was not treating his beloved child bride in his usual way, and was acting distant. She finally learned of what was going on when another woman told her, then she told her mother about it. Her mother suggested that one of Mohammed’s other wives, or one of their family members, was behind it.

My mother said, "O my daughter! Take it easy, for by Allah, there is no charming lady who is loved by her husband who has other wives as well, but that those wives would find fault with her." ... That night I kept on weeping the whole night till the morning. My tears never stopped, nor did I sleep

Mohammed’s pride was badly wounded by all this, so he consulted with some of his bros concerning the topic--how to determine Aisha’s guilt (Allah was in the shower at the time and couldn’t answer the phone) and what to do with her if she was in fact guilty. Ali said that it would be no big deal if Mo just tossed her aside regardless of the truth (Aisha would never forget this), but suggested asking one of Aisha’s slaves if she’d seen anything.

while I was still weeping, Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) called `Ali bin Abi Talib and Usama bin Zaid when the Divine Inspiration delayed, in order to consult them as to the idea of divorcing his wife. Usama ... said, "O Allah's Messenger (ﷺ)! She is your wife, and we do not know anything about her except good." But `Ali bin Abi Talib said, "... Allah does not impose restrictions on you; and there are plenty of women other than her. If you however, ask (her) slave girl, she will tell you the truth." `Aisha added: So Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) called for Barira and said, "O Barira! Did you ever see anything which might have aroused your suspicion? (as regards Aisha)”. Barira said, “... I have never seen anything regarding Aisha which I would blame her for except that she is a girl of immature age who sometimes sleeps and leaves the dough of her family unprotected so that the domestic goats come and eat it.”

The slave called Aisha immature but said she has never seen her with any men. Mohammed was now very irritated at Abdallah ibn Ubayy--who you may remember as one of the “munafiqun” who helped the Jews and didn’t want to go to Tabouk. He was the chief of one of the tribes of Medina, the Banu Khazraj.

So Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) got up (and addressed) the people an asked for somebody who would take revenge on `Abdullah bin Ubai bin Salul then.

This set off an argument between the Khazraj and the other main (formerly) polytheistic tribe of Medina, the Banu Aws. Mohammed just sighed and presumably began banging his head against a wall.

So the two tribes of Al-Aus and Al-Khazraj got excited till they were on the point of fighting with each other while Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) was standing on the pulpit.

Aisha, meanwhile, was miserable and still locked in her house, spending all her time crying and fearful. Mohammed came to Aisha and told her to confess to Allah if she had done something wrong, but she refused, because she wasn’t guilty of anything. At that exact moment, Allah finally got out of the damn shower and informed Mohammed that Aisha was innocent. The story’s epilogue states that Mohammed never did “deal with” Abdallah, who never admitted his “guilt” and could never be proven as the source of the rumors. Because he was the leader of one of Medina’s important tribes, killing him without evidence would have been an issue. Some others did admit to spreading the gossip, though, including the sister of one of Mohammed’s wives, as Aisha’s mother suspected; a poet named Hassan ibn Thabit, who was a messy bitch who lived for drama; and, curiously, a man from Aisha’s own extended family. They were admonished but Mohammed told everyone to just forget about all of it and never speak of it again.

As for the truth of what happened that night, look, idk. This hadith is from Aisha herself, and she would obviously want to present herself as innocently as possible. There are other ahadith where she seems to stretch the truth a tad in order to protect her reputation, like this one, which we’ll see much later on. Maybe Safwan was really hot and Aisha was sick of being married to an old guy, I wouldn’t blame her. But it’s more likely that she really was innocent--I mean the girl had been indoctrinated and brainwashed since childhood, the concept of infidelity probably never even occurred to her. And Safwan would’ve had to possess balls of steel to screw around with Mohammed’s youngest and favorite wife. So I tend to believe the allegations were false rumors. Whether Abdallah was truly involved or whether he was just the Token Guy To Blame as always, I can’t tell you.

Let’s get back to the Quran now. In 24:4, Mohammed says that people who accuse “honorable women” of adultery without evidence/witnesses/proof should be lashed 80 times, unless they say they’re sorry and repent. Uh... I guess that’s neutral, altogether? Corporal punishment is bad, but falsely accusing women of being adulterers is also bad, right? It evens out.

If you are accusing your own wife of zina, though, then your own testimony is all that’s needed. A man has to invoke a curse upon himself, called lian, saying that Allah can punish him if he’s lying. But if the wife says she’s innocent and also invokes the curse of Allah upon herself, telling Allah to send his wrath upon her if she’s lying, then what?! It’s a curse-off... one’s gotta be lying, but Allah’s punishment isn’t coming down upon either, so who is the truthful one?! Lo! It is like one of those games with the two-headed dragons, with one head that tells the truth and the other that only lies. Ibn Kathir collects some ahadith on this matter here if you want to see how Mohammed “resolved” this issue, though that one was only “resolved” because the woman was pregnant and her kid was obviously not her husband’s. Without that evidence, you’re just left sitting around waiting for Allah’s curse to materialize upon the liar. Tbh because it’s all so circular I feel like it’s ultimately neutral?

Now then... let’s talk about “the slander”. In 24:10, Mohammed thanks Allah for revealing the truth to him. Those who spread the lies, he says, are a “gang” and the one ultimately responsible for starting the rumor will be met with The Doom. He scolds the Muslims in general for not immediately shutting down the rumors, given that the accusers couldn’t identify any witnesses to the alleged affair. It’s a good thing that Allah is in a good mood today, he tells them, or else they’d all be doomed for their gossip, which was a grievous sin. They shouldn’t have even dared speculate about it, and they must never do this again.

Like... this is a bit much, but in context it’s at least understandable and neutral. You don’t accuse a cult leader’s child bride of being a ho and expect him to take it well.

This has been a long section because of that hadith, so I’ll leave it there for now.

NEXT TIME: We finish up the Slander Debacle and move onto forced modesty rules!!!

The Quran Read-Along: Day 128

Ayat: 17

Good: 0

Neutral: 15 (24:1, 24:4-17)

Bad: 2 (24:2-3)

Kuffar hell counter: 0

⇚ previous day | next day ⇛

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

- ̗̀✰ •【 TARON EGERTON / CISMALE / 26 】announcing the arrival of his/her/their royal highness, ( ELIAS JOSEPH EDWARDS ), the ( CROWN PRINCE ) of ( GERMANY ). I’ve heard that she/he/they is/are ( MANIPULATIVE ) & ( SARCASTIC ) but can also be ( INTELLECTUAL ) & ( RESOURCEFUL ). ( ELIAS ) is arranged to marry ( VICTORIA WINDSOR ). Rumor has it (THEY SUFFER FROM EPILEPTIC SEIZURES ). We hope you enjoy your stay at London!【 OOC: rose, 21,est,she/her 】

Hi friends! Rose again with my sickly prince. I couldn’t resist taking up a second character, and really wanted to take a fun twist on an interesting troupe. Below are bullet points on who he is as a person, backstory and the usual couple of idea for wanted connections.

Elias and his mother Queen Elena were in a car accident when Elias was five years old, a year before the birth of his younger brother. The prince and his mother were on the way to meet with their father, when their driver lost control of the car. The limo rolled five times, and with later inspection it was discovered the vehicle was tampered with shortly before their departure.

His mother survived with minor injuries but the Prince had been thrown from their limo and was rushed to medical care almost immediately. Under the care of the best doctors in Germany, he was officially labeled unresponsive and in a coma.

His accident became international news, at the time the only son of the King of Germany holding on by a thread. It was covered by every news outlet, and several other royal families weighed in on the tragic turn of events.

He was in a coma for three months before his Father desire a second child in case Elias perished.

His mother was five months pregnant when he came out the Coma. The Sleeping Prince had woken up 10 months after his accident and began his climb back to physical and mental health.

He began physical therapy and was kept under observation during his early stages of recovery which was a blessing given the boy collapsed barely a month after his awakening in a seizure. Doctors examined him and determined the accident and being thrown from the car caused mild neurological damage that resulted in the Prince being diagnosed with Epilepsy.

His Father and Mother quickly covered up the diagnosis, paying off Doctors or sabotaging the credibility of others who refused to be paid off.

They didn’t want the country to lose faith in their future king by viewing him as damaged.

He takes medicine to help prevent seizures but has suffered many in his life and has been swapped between several different medications hoping to find his magic pill.

He suffers minor symptoms of his neurological damage such as random shaking in his hands, randomly his muscles can lock up making it hard for him to move said body part for a short duration or he’ll lose his train of thought and stammer. These symptoms come about if he isn’t keeping up with his medicines or several days following a seizure.

He spent most of his early life in therapy, teaching him ways to control stress in his body and how to avoid situations that might trigger seizures.

Due to this he is a bit of a health nut, he has a strict dinning schedule and goes to bed a relatively decent hour in hopes of eliminating triggers in his life.

He doesn’t see his epilepsy as much of a threat to his claim to the crown as his parents do but follows their lead but he does worry that one day, a seizure might damage him worse and he’ll be unable to rule.

Growing up after his Accident, he became spoiled by his parents and this caused him to develop a partial bit of self entitlement.

He is envious of his younger brother.

He was still governed in the sense of needing to be the perfect example of a German Gentleman. He dresses right, and learned how to break the rules without getting caught.

His scandals have included Romantic Scandals, Drug Addiction * neither confirmed or denied by the royal family* (Mistaking his medical pill taking), Public Indecency.

His mother after almost losing her son indulged most if not all of his whims and this caused him to grow to see other people outside of his family as chess pieces.

To Elias the world is this big game and he is a play maker. He has been responsible for outing several of his father’s mistresses, and outing spies within their staff who were simply trying to manipulate the royal family.

He views his engagement as another play by his family, He will be playing a part in unifying the English and German people by bringing one of the English Royal Family daughters as the Next Queen of Germany.

Given Germany’s Checkered past, his engagement is seen as a stepping stone to ensure his country has a more positive impact on the global world not just the local.

He can cordial and kind and is a beloved figure in the public eyes but the Red Queen has been commenting on the fact he has his own personal doctor, and his frequent visits to hospitals. Painting that the health nut of a prince, might not be as healthy as he would like the world to believe.

Wanted Connections

Ex-Girlfriends : Elias has had his fair share of romantic relationships over the years, be it with Princess or nobles or even part of his palace staff. They broke up for one reason or another but now they are face to face again because of this summit.

Not Over You: Elias truly loved this person but due to his medical issues he broke up with them after they witnessed one of his blackouts without any explanation.

A Fellow Player: This is a Royal who connected with Elias in their love for playing the game. They often make up competitions between each other and keep a personal tally of who is winning and losing.

You Get Me: This is a Royal who can put Elias in his place and ngl he loves it. They shrink his big head and keep him balanced, when they are around the prince is almost a different person.

Gym Rats - They met be it out for an early morning run while one or the other was visiting the others country but the two found someone they can stand to work out with and their friendship rotates around small talk and jokes

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Propaganda

Mae West (She Done Him Wrong, I'm No Angel)— Legendary sex symbol. Like 500 vintage iconic quotes and double entendres. "Is that a gun in your pocket, or are you just happy to see me? " "When I'm good, I'm very good. But when I'm bad, I'm better" / "It's not the men in your life that count, it's the life in your men" / "I feel like a million tonight. But one at a time." , "Marriage is a fine institution, but I'm not ready for an institution. " / " How tall are you without your horse? Six foot, seven inches. Never mind the six feet. Let's talk about the seven inches! " Look the pictures don't do her justice just watch a compilation and tell me that voice doesn't do it for you

Flora Robson (Fire over England, Sarabande for Dead Lovers)— It's a testament to her power that despite an extensive film career, that a single role has cemented itself firmly in my mind as one of the best. That of Elizabeth I in Five over England

This is round 1 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut]

Mae West:

Her voice! Her body! She was thick as hell and SO confident.

Mae West is often called the queen of the sexual pun or innuendo, she was an early sex symbol and a comedy icon. She also has a quote saying "When I am good, I am very good. But when I am bad I am better!" which is possibly the peak of hot girl energy ever. (Including the clip here)

for an era that didn't have much wiggle room when it came to women that studios wanted in their films, it's refreshing that she was in her late 30s when she skyrocketed to movie fame. she was also curvy and witty and raunchy, an absolute icon!

She is an absolute icon, the OG sex symbol. Every word from her mouth was an innuendo and she was proud of it. I guess one could say she slayed. She got Cary Grant his first acting role, as well. How could you NOT vote for someone who says such iconic stuff as "I do all my writing in bed; everybody knows I do my best work there" or "You only live once, but if you do it right, once is enough." SHE COINED THE PHRASE "IS THAT A GUN IN YOUR POCKET OR ARE YOU JUST HAPPY TO SEE ME?" I LOVE HER!!!

“I created myself and I never put up with sloppy work”-mae west

great short compilation of mae west mae westing:

youtube

She was a SEX GODDESS at a time when that was an extremely scandalous thing to be, and she worked it! She was sardonic, sarcastic, funny...and stacked! Favorite quote (from Night After Night, 1933): Random woman: Goodness! What beautiful diamonds! Mae West: Goodness had nothin' to do with it, dearie.

i personally love this silly production number from one of her lesser known movies

She was arrested for indecency and chose to serve 10 days in prison instead of paying the fine for the publicity, and she claimed that she refused to wear the ugly prison outfits so she wore her silk lingerie the entire time. Also one of the first historybound vintage fashion icons (although vintage for her was the Victorian era)

Flora Robson:

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

C:R ~VE~ Chapter 4

I wish I dreamed more often. I read somewhere that our dreams let us know our heart’s deepest desires. It allows them a safe place to manifest, one where nobody else can see.

But my dreams are always black. Peaceful, but quiet. It’s like my mind refuses to let me have a conversation with myself.