#blanca ii of navarre

Text

In order to prevent Blanca (II of Navarre) from opposing the terms of the treaty and her disinheritance, it was decided to send her north on the pretext of marrying Charles, Duke of Berri and brother of Magdalena and Louis XI. When Blanca rejected the idea of the match and refused to leave Navarre, she was taken by force. By April 23, she had reached the monastery of Roncesvalles, where she wrote a lengthy missive, protesting about her abduction, claiming “my father took me by force and contrary to my will.” In this document, Blanca repeatedly refers to herself as “the firstborn [eldest] and queen regnant and Lady and heiress of the said kingdom,” which she noted came to her through “the maternal line.” The princess castigated her father for his treatment of the Principe de Viana, claiming Juan had “forgotten the love and paternal duty” that he owed his eldest son. Blanca also blamed her sister and brother-in-law’s ambition to rule Navarre for her plight; “The said Count of Foix and his wife, my sister, are taking me to exile me and to disinherit me of my kingdom of Navarre.”

Blanca became increasingly desperate as she was taken further north, drafting appeals for help to her former husband, the King of Castile, her cousin the Count of Armagnac and the head of her Beaumont supporters. By April 30, she gave up her brave defense of her position as the rightful queen and attempted to donate her right to the crown to her ex-husband, Enrique of Castile, rather than see the kingdom go to her younger sister. Once Blanca reached the northern frontier of Navarre, she was transferred to the custody of the Captal de Buch and imprisoned in the castle of Orthez, a stronghold that belonged to her brother-in-law, Gaston of Foix.

Blanca’s removal did not quiet her supporters or end the struggle over the succession of the realm. Civil war still raged between the Beaumonts, who championed Blanca, and their rivals, the Agramonts, and matters had been made worse by Enrique of Castile’s decision to invade Navarre to press the claim to the throne that his ex-wife had bestowed on him. The Bishop of Pamplona attempted to resolve the situation with the Accord of Tafalla in late November 1464, which called for Blanca’s return to Navarre in order to settle the matter of the succession. Unfortunately, Blanca was unable to respond to the summons as she died, rather suspiciously, shortly afterward on December 2, 1464. Her sister Leonor has been repeatedly accused by chroniclers, historians, novelists, and other writers of being involved in Blanca’s death, although there is little definitive evidence to support this allegation. There is no doubt that Leonor had a motive for her sister’s murder, but Courteault has argued that given that only ten days lapsed between the ratification of the agreement and the death of the princess, it is difficult to claim that Blanca was killed specifically in response to the drafting of the accord. The eighteenth-century historian Enrique Flórez accurately summed up Blanca’s difficult position: “because [she] did not have the strength to maintain the right to the crown, she lost not only the kingdom, but her freedom and her life.

-Elena Woodacre, "The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512"

#💔#Juan the Faithless is one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about#he was beyond awful#he destroyed his son's life as well#Juana of Castile was his granddaughter and was treated just as badly by HER father (Juan the Faithless's son Ferdinand II of Aragon)#i guess this is where he learnt it from#historicwomendaily#blanca ii of navarre#blanche ii of navarre#15th century#my post

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

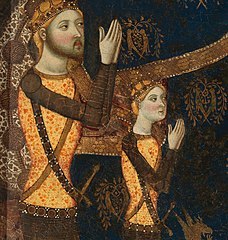

1) Henry II of Castile ( 1334 – 1379), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán; and his son with Juana Manuel de Villena, John I of Castile (1358 – 1390)

2) His wife, Juana Manuel de Villena (1339 – 1381), daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena and his wife Blanca de la Cerda y Lara; with their daughter, Eleanor of Castile (1363 – 1415/1416)

3) His father, Alfonso XI of Castile (1311 – 1350), son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal

4) His mother, Leonor de Guzmán y Ponce de León (1310–1351), daughter of Pedro Núñez de Guzmán and his wife Beatriz Ponce de León

5) His brother, Tello Alfonso of Castile (1337–1370), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

6) His brother, Sancho Alfonso of Castile (1343–1375), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

7) Daughters in law:

I. Eleonor of Aragon (20 February 1358 – 13 August 1382), daughter of Peter IV of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Sicily; John I of Castile's first wife

II. Beatrice of Portugal (1373 – c. 1420) daughter of Ferdinand I of Portugal and his wife Leonor Teles de Meneses; John I of Castile's second wife

Son in law:

III. Charles III of Navarre (1361 –1425), son of Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois; Eleanor of Castile's huband

8) His brother, Peter I of Castile (1334 – 1369), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Mary of Portugal

9) His niece, Isabella of Castile (1355 – 1392), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

10) His niece, Constance of Castile (1354 – 1394), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#henry ii of castile#john i of castile#juana manuel de villena#eleanor of castile#alfonso xi of castile#leonor de guzmán#tello alfonso of castile#sancho alfonso of castile#peter i of castile#constance of castile#isabella of castile#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#eleanor of aragon#beatrice of portugal#charles iii of navarre#canonjonsnow

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

AU House of York:Children Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville.

Richard(1473 - 1540). Duke of York. Husband of Anne Mowbray and father of 10 children: John, Eleanor, Jane, Humphrey, Ursula, Geoffrey, James, Elizabeth, Joan and Anne. Regularly quarreled with his elder brother over his politics, for which he was banished from court. After his nephew's accession to the throne he was forgiven.

Anne(1475 - 1540). Queen of Navarre. Wife of Jean III of Navarre. Mother of 6 children: Louise, Henry II, Madalena, Arnaud, Gerard and Francoise. The marriage of Anne and Jean was not a happy one as the king had love affairs on the side. Because of her soft character, Anne had to put up with her husband's infidelities. She also did not settle at court because she was a foreigner.

George(1477 - 1546). Duke of Bedford. Husband of Elizabeth Howard and father of 13 children: Elizabeth, Edward, Catherine, Marcella, Dorothy, Charles, Edmund, Agnes, Douglas, Ralph, Jasper, Emma, Lionel. He had a sociable nature and loved jokes, and in his spare time wrote poetry. George and Elizabeth's marriage was a happy one.

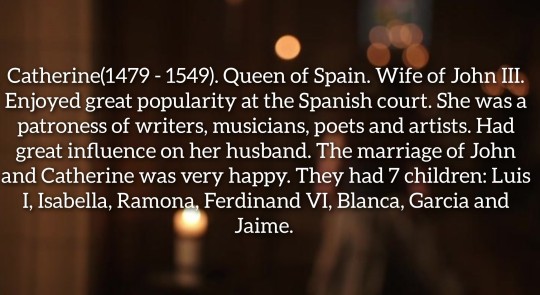

Catherine(1479 - 1549). Queen of Spain. Wife of John III. Enjoyed great popularity at the Spanish court. She was a patroness of writers, musicians, poets and artists. Had great influence on her husband. The marriage of John and Catherine was very happy. They had 7 children: Luis I, Isabella, Ramona, Ferdinand VI, Blanca, Garcia and Jaime.

Briget(1480 - 1550). Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. Wife of Philip I of Austria and mother of 9 children: Maximilian II, Frederick, Mary, Rudolf, Elizabeth, Eleanor, Philip, Margaret, Albrecht. She exercised great influence not only on her husband but also on her son Maximilian II. Under her, the imperial court became the center of European culture.

AU: Дети Эдуарда IV и Елизаветы Вудвилл.

Ричард(1473 - 1540). Герцог Йоркский. Муж Анны Моубрей и отец 10 детей: Джон, Элеонора, Джейн, Хамфри, Урсула, Джеффри, Джеймс, Елизавета, Джоан и Анна. Регулярно ссорился со своим старшим братом из за его политики, за это был изгнан со двора. После восшествия племянника на трон был прощен.

Анна(1475 - 1540). Королева Наварры. Жена Жана III Наваррского. Мать детей 6 детей: Луиза, Генрих II, Мадалена, Арно, Жерар и Франсуаза. Брак Анны и Жана был не счастливым так как у короля были любовные связи на стороне. Из-за мягкого характера Анне пришлось смириться с изменами мужа. При дворе она тоже не прижилась, потому что была чужеземкой.

Джордж(1477 - 1546). Герцог Бедфорд. Муж Элизабет Говард и отец 13 детей: Елизавета, Эдуард, Екатерина, Марселла, Дороти, Чарльз, Эдмунд, Агнес, Дуглас, Ральф, Джаспер, Эмма, Лайонел. Обладал общительным характером и любил шутки,а в свободное время писал стихи. Брак Джорджа и Элизабет был счастливым.

Кэтрин(1479 - 1549). Королева Испании. Жена Хауна III. Пользовалась огромной популярностью при испанском дворе. Была покровительницей писателей, музыкантов, поэтов и художников. Имела большое влияние на своего мужа. Брак Хуана и Екатерины был очень счастливым. У них родилось 7 детей: Луис I, Изабелла, Рамона, Фердинанд VI, Бланка, Гарсиа и Хайме.

Бриджитт(1480 - 1550). Императрица Священной римской империи. Жена Филиппа I Австрийского и мать 9 детей: Максимилиан II, Фридрих, Мария, Рудольф, Елизавета, Элеонора, Филипп, Маргарита, Альбрехт. Пользовалась большим влиянием не только на супруга, но и на своего сына Максимилиана II. При ней императорский двор стал центром европейской культуры.

Part 2.

#history#history au#royal family#royalty#english#english history#history of england#england#englisch#elizabeth of york#Elizabeth of Woodville#british#british royalty#british royal family#house of york#house of tudor#english royalty#henry vii of england#au#Royals#Royal

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Virdimura was a XIVth century Sicilian Jew living in Catania and married to Pasquale, himself a Jew and physician (“Virdimuram ludeam uxorem pascalis de medico de cathania ludei servi camere nostre”). Even though news about Virdimura’s life are very scarce (we don’t know, for instance, when she was born or died), it can be claimed she was the first woman to be officially authorized to practice the medical profession in Sicily (“licenciam praticandi in sciencia medicine circa curas phisicas corporum humanorum”). It wasn’t, in fact, uncommon during the Middle Ages that a woman (wife or daughter or sister) learnt medicine from their male relatives and were often asked to unofficially perform medications and prepare medicaments off secret family recipes, to the point we can talk about actual medical dynasties. Until the middle of the XVth century, Jewish doctors made up the majority of the Sicilian medical personnel since many Sicilian Christian doctors had migrated towards Salerno and other Northern Italy cities. Sicilian Jews could speak Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Arabic and this ability facilitated them in the study of medical treatises. Starting XIII-XIV women were able to attend universities courses, and (talking about the Kingdom of Sicily) were welcomed at the Schola Medica Salernitana and the University of Naples. The only thing that distinguished a woman from her male Christian colleagues was that she couldn’t boast the title of doctor since (according to Christian jurists) nor women nor Jews possessed the dignitas, such as the legal capacity to exercise autorictas. That meant they could practice medicine (and reached the level of magister), but not teach it. Moreover, according to the Sicilian constitution of 1310, Jewish doctors couldn’t treat Christian patients lest they would be sentenced to a year in jail and forced on bread and water, while the patient’s detention would last three months (although some of these Jewish doctors became court physicians and treated sovereigns and even Popes and members of the clergy).

Back in 1134 and 1140, Ruggero II of Sicily had regulated that nobody could practice the medical profession without authorization and in 1224 Federico II decreed that the candidate needed to be previously authorized by an official commission of doctors of the Schola Medica Salernitana before practising medicine. An official document dated November 7th 1376 attests that Virdimura, was indeed tested by the Chief Physician of Sicily (the Dienchelele), who awarded her the medical licence, which she could practice in the entire territory of the Kingdom of Sicily (“ubique locorum dicti regni nostri Sicilie”). The document states that, even before passing the medical test, Virdimura was already universally praised (“qui eamdem virdimuram previa examinadone predicta. ac suadente fama laudabili”) and that she used to treat those people who couldn’t afford to pay doctor’s high fees (“maxime pauperum quibus dificile censetur immensa phisicorum et medicorum salaria solvere”).

Despite being a rather unknown historical figure, Virdimura is still nowadays celebrated with the creation of a “Virdimura Award”. Created in Catania in 2013, this international award honours all those women who, aside from practising medicine, have devoted their lives to helping their neighbours.

Bella di Paija was a XVth century Sicilian Jew living in Mineo (nearby Catania), home to one of the most active Sicilian Giudeccas between the XIV-XVth centuries. Like for Virdimura, news about Bella’s life are pretty much nonexistent. We know though that she was married and had unofficially practised medicine for decades before being officially licensed to perform surgeries.

Unlike Virdimura, who had to petition to be judged by the committee to receive her permission (“Cum ad humilem supplicacionem factam novicer excellencie nostre”), Bella was personally licensed through a royal decree on September 6th 1414 by the Regent Blanca of Navarre, who had been informed by trusted persons about Bella’s long and successful career (“havi patricatu et exerzuta l’arti di la celurgia in la quali si havi ben portatu, cum sanitati di li pacienti”). Bella could now officially practice surgery (“in qualsivoglia infirmitati di celurgia”) in all the territories part of the Camera Reginale (the dowry Sicilian Queen consorts received upon marrying and consisting on the fieffs of Paternò, Mineo, Vizzini, Castiglione di Sicilia, Francavilla di Sicilia, Siracusa, Lentini, Avola, the village of Santo Stefano di Briga, the island of Pantelleria, and Castle of Maniace in Siracusa). Another difference between the two physicians was that, differently from Virdimura, Bella and her husband were exempted from paying taxes and shouldn’t suffer any kind of harrassment (“liberi et exempti di omni angaria, perangaria, collecti, imposicioni”). Female Jewish physicians (licensed or not) were particularly appreciated, especially by their fellow female patients (who made up the majority of their clientele) and were considered experts in obstetrics and in general all those diseases and issues which concerned the female body. Apart from treating broken bones, sewing up wounds and perform small operations, these medichesse were very often asked to restore through plastic surgery the virginity of those Jewish women who had had sexual intercourses prior the marriage and were afraid to be repudiated once their future husbands had discovered they were no longer virgins. They also gave advices concerning birth control and assisted their patients in case of abortion, or during their pregnancy and at the moment of the birth. It must be pointed out that, unlike their Christian colleagues, since XIIth century Jewish physicians stressed the importance of washing their hands before treating a patient, anticipating thus the discovery of XIXth Hungarian physician Semmelweis.

Sources:

- BELFIORE G., Le medichesse, l’importante ruolo delle ebree in Sicilia;

- FASANO G., L’incredibile storia di Virdimura e delle altre medichesse siciliane;

- FRISCIA V., Bella de Paija e Virdimura de Medico: due medichesse catanesi;

- LAGUMINA G. - LAGUMINA B., Codice diplomatico dei giudei di Sicilia, vol. I-part I;

- LEONE A., Medici e Medichesse ebrei nella Sicilia del 1400;

- POTTINO P., Virdimura, la “dutturissa” che sfidò i preconcetti nella Sicilia medievale;

- PRECOPI LOMBARDO A., Virdimura, dottoressa ebrea del Medio Evo siciliano;

- SANTORO D., La cura delle donne. Ruoli e pratiche femminili tra XIV e XVII secolo in Memoria, storia e identità. Scritti per Laura Sciascia;

- STRANGES P., Premio Virdimura a Corinne Devin, da Miss Stati Uniti ai Marines;

- TAITZ E. - HENRY S. - TALLAN C., Jps Guide to Jewish Women;

- VENTURA D., Medici Ebrei a Catania

#women#history#history of women#women in history#historical women#virdimura#bella di paija#province of Catania#catania#mineo#aragonese-spanish sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aragonese infantas aesthetic, part II

Maria, señora de Cameros. Daughter of Jaume II and Blanche d’Anjou. Mother of Blanca de Castilla.

Elisabet, Königin des Heiligen Römischen Reichs. Daughter of Jaume II and Blanche d’Anjou. Mother of Anna von Habsburg, Herzogin von Bayern.

Constança, reina de Mallorca. Daughter of Alfons IV and Teresa d’Entença. Mother of Elisabet de Mallorca, marchesa di Monferrato.

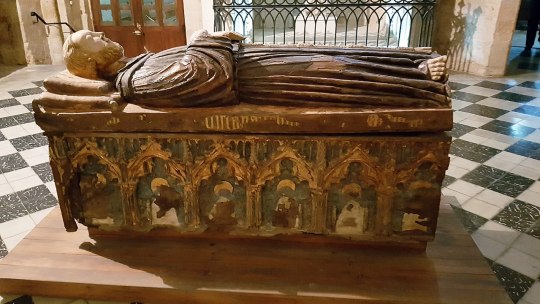

Constança, regina di Sicilia. Daughter of Pere IV and Marie de Navarre. Mother of Maria, regina de Sicilia.

Elionor, reina de Castilla. Daughter of Pere IV and Elionor de Sicília. Grandmother of María de Castilla, reina d’Aragó; Catalina de Castilla, duquesa de Villena; Maria d’Aragó, reina de Castilla; and Elionor d’Aragó, rainha de Portugal.

Elisabet, comtessa d’Urgell. Daughter of Pere IV and Sibilla de Fortià. Mother of Elisabet d’Urgell, duquesa de Coimbra.

Joana, comtessa de Fois. Daughter of Joan I and Marta d’Armanhac.

Violant, duchesse d’Anjou and regina di Napoli. Daughter of Joan I and Yolande de Bar. Mother of Marie d’Anjou, reine de France. Grandmother of Isabelle d’Anjou, duchesse de Lorraine; Marguerite d’Anjou, Queen of England; Radegonde de France; Catherine de France, comtesse de Charolais; Yolande de France, duchessa di Savoia; Jehanne de France, duchesse de Bourbon; and Madeleine de France, Vianako printzesa.

Maria, reina de Castilla. Daughter of Ferran I and Leonor Urraca de Castilla, condesa de Alburquerque. Grandmother of Juana la Beltraneja de Castilla.

Elionor, rainha de Portugal. Daughter of Ferran I and Leonor Urraca de Castilla, condesa de Alburquerque. Mother of Leonor de Portugal, Sacri Romani Imperatrix; Catarina de Portugal; and Joana de Portugal, reina de Castilla. Grandmother of Santa Joana de Portugal; Leonor de Viseu, rainha de Portugal; Isabel de Viseu, duquesa de Bragança; Kunigunde von Österreich, Herzogin von Bayern-München; and Juana la Beltraneja.

#house of barcelona#medieval#house of trastamara#historyedit#spanish history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#royalty aesthetic

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isabella of Castile, the Catholic, was born on April 22nd in 1451, on Maundy Thursday, at the so-called royal palace of the village of Madrigal, called de las Altas Torres. At the moment the most important source about the birth is the letter sent by John II to the city of Segovia, on April 26th, 1451, informing them of such happy event:

’I let you know that, by the grace of our Lord, past Thursday the Queen doña Isabel, my very dear and very beloved wife, gave birth to an infanta, which I let you know so you would give many thanks to God for the liberation of the said Queen, my wife, and for the birth of the said infanta, because of which I ordered Johan de Busto to go to you, who carries the present.’

That <<past Thursday>> coincided with Maundy Thursday hence could not be more important in religious Christian life, and she took responsibility to celebrate it during her whole life with her family and with her court. The chronicler Doctor Toledo will specify that she was born in Madrigal, on Thursday, on April 22nd, at 4:30 pm. Thanks to both sources, we have established the day and hour of birth.

The same can be said about the birthplace, the cradle of the future Queen. It was at the royal palace of Madrigal, not a monumental building which was not for these places of residence, but a temporal residence in the itinerant life of the king and the court. Thus, its simplicity is understandable and its austere mudejár style can be recorded. It seems that house captivated the Portuguese (Isabella’s mother). The palace and the entire village were hers. She would go there to take refuge during decades, when her psychosis intensified, and there she would pass away.

The newborn was not fed by her mother; it’s certain that Isabella’s wet-nurse was María López, wife of Juan de Molina, whom the queen will recall on March 3, 1495, granting her 10.000 maravedíes <<because the said María López gave her Highness her milk>>. This fact appears in las Cuentas (household accounts) and is indubitable.

- “Isabel la Católica: vida y reinado”, Tarsicio de Azcona

Isabel was born far inland, behind the lofty walls of Madrigal de las Altas Torres—Madrigal of the High Towers—in the heart of the meseta, the flat tableland at the heart of Castile. The forty-eight altas torres rising along the forty-foot-high walls ringing the town spoke of safety in a world geared to war, particularly war between Christian inhabitants and Muslim raiders. But those walls also spoke of paradox: made of brick and rubble, materials typical to mudéjar construction, they revealed an origin or an inspiration unequivocably Arabic. Madrigal, like other places on Spain’s central plateau, had been alternately occupied by Christians and Muslims until well into the eleventh century, and it was home to some inhabitants of Muslim culture afterward. In Madrigal too, in the great house abutting those walls called the royal palace, Isabel toddled under intricately worked wooden ceilings, artesonados, carved by mudéjares, Muslim subjects of Castile’s king. And tradition has it that she was baptized in Madrigal’s church of San Nicolás, in its baptismal font thickly encrusted with gold from Muslim Africa.

Only an occasional reference sheds light on Isabel’s childhood. At seventeen, she wrote to her half-brother, the king Enrique IV, accusing him of having treated her badly, representing herself as a semi-orphan raised in obscurity and kept in want by him. Her court chronicler, Hernando del Pulgar, was to state that her early years were spent ‘in extreme lack of necessary things,’ and that she was without a father and ‘we can even say a mother.’

Isabel was three when her father, Juan II of Castile, died. He had doted on her mother, Isabel of Portugal, his young second wife, and, rumor had it, come to resent the control exerted over him by his longtime mentor, Alvaro de Luna, who sought to regulate the king’s conjugal visits to his queen. What is indisputable is that shortly after Isabel’s birth, Luna was beheaded at Juan’s order. Within a year, Juan, whether through regret or because Luna’s restraining hand was gone, grew immoderate, it was said, in the pleasures of love and table, fell ill of quartanary fevers, and although believing prophecies that he would live to be ninety, died on July 21,1454, and the crown passed to his elder son, Enrique. Juan was forty-nine years old, the longest-lived king of his dynasty in five generations.

Enrique IV was then thirty. He had had no children with his first wife, Blanca of Navarre, and his second, Juana of Portugal, would have none until Isabel was ten; until then Isabel grew up seeing her younger brother, Alfonso—born in November 1453 when she was two—as heir apparent to Castile’s crown and herself as second in line, as her father’s last will had stipulated. To the childless Enrique, the two children represented family and dynastic continuity, but also a potential threat. As for Isabel, after the death of her father, her circumstances were none too secure on several other counts she did not mention in that letter.

Her mother, the young dowager queen, Isabel of Portugal, who was twenty-seven years old at her husband’s death, then took the two children to live in Arévalo, a royal town consigned to her in Juan’s will. Shortly thereafter, according to the chronicler Alonso de Palencia, Enrique called on her accompanied by a favorite of his, Pedro Girón, the master of the military order of Calatrava; Girón immediately ‘made some indecent suggestions’ that shocked the recent widow. Palencia, who is generally vitriolic about both Enrique and Girón, went on to assert that the importuning by this overhasty, unwelcome (and, patently, not sufficiently noble) suitor threw Isabel of Portugal into a profound sadness and horror of the outside world, that she then ‘closed herself into a dark room, self-condemned to silence, and dominated by such depression that it degenerated into a form of madness.’

Another chronicler, who was more in touch with events at the time, confirms the reclusiveness of Isabel’s mother but dates it earlier, from her daughter’s birth. Whatever the cause or date, young Isabel grew up with a deeply disturbed mother. The child may well have dreaded becoming like her, and suffered tension between affection and fear. Surely too she was aware that her own birth was among the causes mentioned for her mother’s madness. It is tempting to conjecture that qualities that Isabel displayed as an adult—love of order and the striving for it; a no-nonsense, highly rational stance; and a sharply defined personality, were honed in reaction to her mother’s condition, and even to think that her desire for light in all its forms, and especially in its religious associations—her abhorrence of the forces of darkness, her determination to cleanse the body politic of impurities—was not unrelated to the circumstances of her childhood.

Isabel grew up, then, in several sorts of obscurity, her childhood a sort of purgatory and a test of moral fiber she passed magnificently. Such was long the accepted version of her early years; it was her own version. It is neither strictly accurate nor complete.

Arévalo, fifteen miles from Madrigal and like it a market town, is remembered as the best fortified of royal towns. There, her mother’s condition notwithstanding, Isabel spent her early years in great stability and familial warmth. For when she was two and her mother again pregnant, her widowed grandmother, Isabel de Barcelos, arrived from Portugal. Tellingly, when first mentioned in the chronicles Isabel de Barcelos is in her forties and sitting, at King Juan’s request, in his privy council. Contemporaries, among them the chronicler Diego de Valera, recognized in her ‘a notable woman of great counsel.’ Valera affirmed that after the death of the king, Isabel de Barcelos ‘was of great help and consolation to the widowed queen, her daughter’; and he commented that her death, in 1466, ‘was very harmful.’ Pulgar adds that Isabel missed her grandmother sorely. Surely Isabel de Barcelos ran her daughter’s household. And she it doubtlessly was whom the child Isabel took as model. It is revealing that later, as queen, Isabel of Castile enjoyed keeping about her elderly women of good repute and good family.

From all accounts, Isabel de Barcelos was a formidable lady of formidable lineage. She came of royal Portuguese stock with a history of going for the throne and of doing it with claims far weaker than would be those of her Castilian grandchild. Daughter of the first duke of Braganza, Portugal’s most powerful noble and an illegitimate son of the king, Joāo I, she had married her uncle, Prince Joāo, one of five sons Joāo I had with Philippa, his queen consort. Philippa too came of redoubtable stock. Her father was John of Gaunt, the English king-making duke of Lancaster, and her mother, Costanza, was a Castilian infanta. This lineage meant that young Isabel carried in her veins the royal blood of Castile, Portugal, and England. Doubtlessly too, she took dynastic pride in her own name, Isabel, repeated through seven generations of royal women and originating in her ancestor Saint Isabel, the thirteenth-century Portuguese queen canonized for her good works and miracles.

Isabel’s aya, or nurse-governess, in Arévalo was also Portuguese. She was Clara Alvarnáez, married to Gonzalo Chacón, to whom Juan II had consigned his children’s education. Chacón was also the dowager queen’s camerero, the administrator of her household. Oddly enough, Chacón had earlier filled the same post for Álvaro de Luna, Juan II’s former favorite. Even so, Chacón and Clara Alvarnáez remained close to Isabel throughout their lifetimes.

- „Isabel the Queen: Life and Times”, Peggy K. Liss

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In total, Leonor governed Navarre as lieutenant, with some minor hiatuses, from 1455 to 1479, making her the effective ruler of the realm for nearly twenty five years. Out of her female predecessors, only Juana I served a longer period; however, Juana I was detached from the governance of the realm and physically distant from Navarre. Leonor however, remained in the kingdom throughout her lieutenancy, making her the female sovereign with the highest record of residency in Navarre.

One of the enabling factors for Leonor’s constant presence in the realm was the “Divide and Conquer” power-sharing mechanism that she employed with her husband, Gaston of Foix. Blanca and Juan had a similar division of duties, but unlike her parents’ often contrary objectives, all of Leonor and Gaston’s actions can be seen to be working toward their joint goals of obtaining the Navarrese crown and politically dominating the Pyrenean region. In order to achieve their ambitions, the couple were adept at working as a team even when physically seperated or carrying out divergent duties.

Politically, it appears that they took on different areas of negotiatiion. Gaston was the designated emissary to the French court, which was entirely appropriate as one of the French king’s leading magnates. One important example of his involvement in negotiations of this type include Gaston’s visit to the French court in the winter of 1461–62 to negotiate the marriage between their heir and the French princess, Magdalena, which ensured Louis XI’s backing for Leonor’s promotion to primogenita. Gaston also conducted negotiations on behalf of his father-in-law, Juan of Aragon, with the King of France, with a successful outcome in the case of the Treaty of Olite in April 1462, which was intimately connected to the marriage that Gaston was orchestrating for his son and Magdalena of France.

Even though Gaston normally took on the role of intermediary with the French crown, there are two letters issued by Leonor during her marriage in December 1466 as lieutenant of Navarre that show her involvement in French affairs. These letters were written during a period of extreme crisis, when Juan II’s difficulties in Catalonia were matched with Leonor’s continuing struggle with the Peralta clan in Navarre. In these letters, Leonor was playing on her familial connection to Louis XI, in hopes of his aid and backing, asking him to “commend this poor kingdom and the said princess to him [Louis XI] as one who is of his house.” Moreover, these letters show Leonor’s independent interaction in crucial diplomatic negotiations with France, both in receiving embassies directly from Louis and in sending her own personal ambassador, Fernando de Baquedano, with detailed instructions on how to proceed.

Gaston appears to have been more engaged with marital negotiations for their numerous offspring than Leonor. However, this may be due to the fact that the couple overwhelmingly chose French marriages for their children. Only three of Leonor’s children did not contract a French betrothal: Pierre who became a cardinal, a daughter who died young, and Leonor’s youngest son, Jacques (or Jaime), who married into the Navarrese nobility. Given the fact that Gaston was more intimately connected to the French court and the nobility of the Midi, it seems reasonable that he would take on the role of chief negotiator for these matches. All of the marital arrangements for their children were made in order for Gaston and Leonor to achieve their joint goals, the acquisition of the throne of Navarre and the consolidation of their power and influence in the Pyrenean region.

Another area where Gaston necessarily played a more central role was militarily. Robin Harris acknowledges Gaston’s successful military career and notes that after his useful military service to the French crown, “the comte was permitted by the [French] king in the last years of his life to employ his military resources in order to further his family’s interests in Navarre.” Gaston also performed many military services for his father-in-law; the agreement of 1455 that promoted Leonor and Gaston to the successors of the realm required Gaston to go to Navarre on Juan’s behalf and retake those areas that had fallen to the rebels “for the honor of the King of Navarre as well as for his own interests and those of the princess his wife."

However, there is some evidence for Leonor’s involvement in one military foray. In the winter of 1471, Leonor took part in a daring attempt to seize the capital, Pamplona, from her opponents, the Beaumonts. Leonor participated in an attempt to storm one of the city gates with a group of armed supporters. Moret notes that “this surprise was reckless; for it exposed the person of the princess to obvious risk and was somewhat rash.” Moreover, the element of surprise was ruined by the cries of her supporters shouting “ Viva la Princesa !” which alerted the Beaumont troops to the threat, and Leonor and her supporters were swiftly ejected from the city.

Like her mother, the noted peacemaker, Leonor was also involved in moves to reduce the civil discord in the realm. Zurita credited Leonor with “making a great effort to resolve the differences of the parties and subdue the kingdom into union and calm.” Leonor represented her father in negotiations for a truce with the supporters of the Principe de Viana on March 27, 1458, at Sang ü esa. Zurita notes, “The princess Lady Leonor was there at that time in Sangüesa and signed the treaty with the power of the king her father.” Leonor was instrumental in the forging of another truce that was contracted in Sangüesa, in January 1473, and she was also present at a conference with her father and her half-brother Ferdinand in Vitoria in 1476 “accompanied by the nobility of Navarre to renew the treatties . . . and attempt to arrive at a stable peace.

Although both spouses were named to the lieutenancy of Navarre, the documentary evidence clearly demonstrates that Leonor appears to have taken on the bulk of the administration of the realm. This was entirely appropriate as it was Leonor, not Gaston, who had the hereditary right to the crown. Moreover, it was logical for Leonor to remain in Navarre so that her husband could look after his own patrimonial holdings and continue to serve as a military commander for the King of France.

Leonor was an active lieutenant but she struggled to implement her rule fully across the kingdom, as many areas were dominated by the Beaumont faction who were opposed to her and her father Juan of Aragon. This meant that at times, she had no control or access to certain key cities in the realm, including the capital, as mentioned previously. Her grandfather’s impressive seat at Olite was the center of her sister’s court, but Leonor eventually regained her hold on the castle and used it as one of her primary residences between 1467 and 1475. Sangüesa remained an important base for Leonor, and she was also associated with Tudela on the southern edge of the kingdom.

Leonor’s difficulty in implementing her rule across the whole of the kingdom is illustrated by a prolonged struggle between the lieutenant and the town of Tafalla, which consistently refused to send representatives when she called together meetings of the Cortes. Tafalla was a center of Beaumont strength, which had supported her brother Carlos in his struggle with Juan of Aragon and was thus bitterly opposed to her appointment to the lieutenancy. Between 1465 and 1475 there is a series of missives from Leonor both summoning representatives from the town and then expressing disappointment when they failed to arrive. During this period, Leonor appears to have called a meeting of the Cortes at least six times, but the town consistently refused to send envoys to the assembly. There is a sense of increasing exasperation and anger in these documents at the repeated failure to participate in these important events. At one point, in late 1471, Leonor personally came to the town to give advance notice of her intent to call another Cortes the following summer, perhaps to circumvent any excuse that the town did not have sufficient time to send representatives, but Tafalla still did not participate in the assembly.

As her authority was contested, Leonor was keen to stress her agency and her position in the documents that she issued. However, at times she even struggled with the chancery; between 1472–73, Juan de Beaumont retained the seals of the kingdom and refused to let Leonor have access to them. In 1475, she granted a reduction in taxes to the important city of Estella acknowledging the reduced capacity of the city to pay after the population had shrunk from the effects of war and flooding. In this document she stressed her efforts to assist all of the urban centers of the realm, to help them recover from the years of civil conflict and devastation, “the other good towns of the said realm have been refurbished by our certain knowledge, special grace, our own change and royal authority.

Leonor’s address clause drew on all of her family and marital ties as a means of establishing her authority:

“Lady Leonor, by the grace of God princess primogenita , heiress of Navarre, princess of Aragon and Sicily, Countess of Foix and Bigorre, Lady of Bearn, Lieutenant general for the most serene king, my most redoubtable lord and father in this his kingdom of Navarre.”

The signet that Leonor used for the majority of her lieutenancy as well as her sello secreto had heraldic devises that mirror her address clause, bearing the arms Navarre, her family dynasty of Evreux, her husband’s counties of Foix, Béarn, and Bigorre, and finally the Trast á mara connections to Aragon, Castile, and Léon.

To sum up, Gaston and Leonor’s ability to divide up roles and responsibilities demonstrates the couple’s effective partnership, using each partner in the most appropriate arena. Moreover, this division was entirely necessary as the couple’s widespread territorial holdings and the demands of balancing the complicated and difficult political situation both within Navarre and the Midi and between France, Castile, and Aragon meant that both partners needed to be fully engaged and active in order to achieve their mutual goals and further their dynastic interests.

Even though Leonor and Gaston generally employed this mode of “Divide and Conquer” that left Leonor primarily responsible for the administration of Navarre while Gaston oversaw his own sizable patrimony, the couple did work together as a unit whenever possible. Documentary evidence shows that Gaston came to stay with Leonor in Navarre for short periods, particularly during the autumn of 1469 and 1470. There is also some additional evidence to indicate an earlier reunion in 1464, which appears to indicate a desire on the part of the couple to be together. Gaston and his party were stuck in the mountain passes between Foix and Navarre on his way to visit Leonor. The princess issued a series of orders to dispatch men and pay for additional recruits and mules in the mountains in order to clear the passes and roads for Gaston, including one order for 300 men to be sent to help. Gaston’s death in 1472 took place on another journey to see his wife in Navarre; he died en route of natural causes in the Pyrenean town of Roncesvalles.

Overall, Gaston and Leonor worked together with the mutual goal of obtaining the crown of Navarre, throwing the weight of Gaston’s power, wealth, connection, and military forces behind Leonor’s hereditary rights and were willing to fight off opposition from their own family in order to succeed. They worked in partnership, with each partner taking on the most appropriate role; Leonor was responsible for the governance of Navarre, and Gaston supported her militarily and financially. They both worked on diplomatic efforts to achieve their ambitions; Gaston used his position as a powerful French vassal and general to gain support while Leonor negotiated with her Iberian relatives to maintain their rights.

[...] Tragically perhaps, Leonor hardly had a chance to enjoy the position of queen regnant when it finally came her way. Leonor’s death, only a few weeks after her father’s in February 1479, meant that her rule as queen lasted less than a month. Leonor changed her address clause to reflect her altered position as “Queen of Navarre, Princess of Aragon and Sicily, Duchess of Nemours, of Gandia, of Montblanc and Peñafiel, Countess of Bigorre and Ribagorza and Lady of Balaguer.” Ram í rez Vaquero points out that most of these titles were disputed; several were titles that should have come to her as part of her paternal inheritance from her father but in reality would have gone to her half-brother Ferdinand de Aragon. In addition, the French titles that Leonor had held as Gaston’s wife had already been passed to her grandson. It appears that Leonor had enough time to mount a formal coronation, on January 28, 1479, at Tudela, firmly establishing herself as Queen of Navarre, even if only for a brief moment. Moret remarked that “out of all the kings and queens of Navarre she was the one who reigned the shortest, although she may have been the one who desired [the crown] most.”

-Elena Woodacre, "Leonor: Civil War and Sibling Strife", "The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512" (Queenship and Power)

#gotta love ruthless ambitious mutually devoted power couples 💅#(they can have a little fratricide. as a treat)#historicwomendaily#Leonor of Navarre#Gaston of Foix#aka the self-declared malewife#Navarre history#Leonor fighting and scheming and waiting for the throne for decades only to finally succeed and then die less than a month later#biggest of Ls honestly#I do wonder what she would have thought about that twist of fate#Was she bitter about the hollow victory of it all?#Or was there nothing but satisfaction that she died as the Queen of Navarre#a position she had fought for for so long#or...both?#(also let's get one loud 'BOO' for Juan the Faithless aka one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about)#(this is the guy who raised Ferdinand 'I'm going to lock up my own daughter' of Aragon btw. This is where he learned it from)

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Doña Blanca de Navarra

Óleo sobre lienzo, 250 x 181,5 cm

Hacia 1885

José Moreno Carbonero

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Doña Blanca de Navarra entregada al captal de Buch por mosén Pierres de Peralta

1869. Óleo sobre lienzo, 58 x 106 cm.

Eduardo Rosales Gallinas

Blanche II of Navarre (1424-1464). Queen of Navarre. Blanche of Navarre is delivered to the Captal of Buch, who orders imprison her into a castle.

Esta obra tuvo su origen en un encargo realizado por José Olea, coleccionista de obras de Rosales. El pintor la comenzó en Roma en 1868 y la terminó en Madrid al año siguiente. Junto con la Presentación de Don Juan de Austria al emperador Carlos V en Yuste es un buen ejemplo de la adecuación del cuadro de historia a un formato de menores dimensiones, más apropiado para residencias burguesas, y en el que el artista podía dejar ver de cerca la calidad de su pintura. La composición, como en aquella obra, es muy clara, en forma de friso que presenta en el centro a los principales personajes. Lo mismo que en aquella obra, para la que el artista había recurrido a un interior del palacio Chigi en Ariccia como punto de partida para representar una hipotética sala del monasterio de Yuste, Rosales ambientó la escena en un palacio italiano, en este caso el cortile del palacio del Podestá de Florencia. Esto le permitió ordenar la escena con su triple arcada y la escalera por la que descienden las damas de compañía de Doña Blanca, a quien Mosén Pierres de Peralta va a entregar, por orden de Juan II, padre de Doña Blanca, al captal del Buch para su traslado a prisión en castigo a su negativa a contraer matrimonio con Carlos, duque de Berry, hijo de Luis XI de Francia. (x)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ferdinand the Catholic was born on March 10th in 1452, on Friday at 2 p.m. in small Aragonese town, Sos. We know it thanks to original letter that is stored at the municipality of Alcira and which had been discovered by M. Gual Camarena. (I have no idea if the said letter is stored there at this point; the book I am using as a reference for that information was published in 1962)

His father John II of Aragon as a deputy of Valencia delivered such news to the Parliament of this city and his mother, Juana Enriquez, addressed directly the Cortes of Cataluña and the Cortes of the city of Barcelona for the same reason. Both messages arrived into respective places on March 27th. The Parliament of Valencia sent congratulations to John due to the birth of his second legitimate son, and decided to grant the messenger, Alfonso Pujalt, the gatekeeper of the king, the amount of 15 timbres of gold. The counselors of Barcelona, on the other hand, were more reluctant. The birth of Ferdinand wasn’t particularly celebrated there, given some problems the Parliament had to resolve at the moment.

It’s said his birth was surrounded by different legends. According to one of them, the arrival of the Aragonese prince into this world was announced by Carmelite monk who had appeared in front of Alfonso V of Aragon at Castillo Nuevo in Naples, and who told him that there, in Spain, an infante of his lineage had been born, the one who would be called the greatest of the Christian Princes. This symbolism clearly fit in with the Islamic triumph over Christianity, hence the belief the future ruler would hold back the intrusion of Muslims with the strength of his arm. According to other legend Ferdinand’s birth was announced by comets that had been circulating over the sky, moving from the lands of Aragon towards the lands of Castile and forward, towards the West. We can notice a reference to the later union between Aragon and Castile, and to the overseas expansion of The Catholic Monarchs. Such legends, clearly created by Ferdinand’s panegyrists, were rendered useless as historical sources.

But as a matter of fact, the fate of Ferdinand had been tied to warlike atmosphere since his birth. The place where he was born was in northern Aragon, close to the border with Navarre, where his father, John „the Great” was the king. Despite that, Ferdinand’s mother feeling she was about to give birth, left Navarre in a hurry, so the child could be born in Aragon. The prince’s birth coincided with the civil war in Navarre between John and his son by his first wife, Charles, The Prince of Viana.

John in 1420 married Blanca, the younger daughter of the king of Navarre, Charles III. Blanca became the heir apparent to the Navarrese throne after childless death of her older sister, Joan in 1413, and assumed the title of the Queen of Navarre in 1425, making John her consort. Meanwhile in 1421 John and Blanca had a son, the infante Charles, for whom, his grandfather Charles III created the duchy of Viana, located in the southwestern zone of the kingdom of Navarre, at the Castilian border.

A few years later, in 1433, Alfonso V passed the governorship of Aragon and Valencia over to his younger brother John, making him the regent of The Crown of Aragon and unofficial successor of his brother - who after settling himself in Naples once and for all, officially had entrusted his wife Maria with the policy of the Iberian Peninsula.

Blanca passed away in 1441, in her last will leaving the title of the King of Navarre to her husband, John, even though the said title lawfully belonged to their firstborn son, Charles. In 1447, John married Juana Enríquez the daughter of Fadrique, the Admiral of Castile. This way John had in his grasp the titles of the King of Navarre, the governor of Aragon and ensured his position in Castile. Ferdinand was the fruit of his marriage to Juana Enríquez. Even though the prince was born in Aragon, Castilian blood did flow through his veins; after his mother from the famous Enríquez family, and after his father who was the son of Ferdinand I from The House of Trastámara.

There is a tradition according to which the newborn baby was christened at the parish church of San Vicente and the ceremony was celebrated by the Bishop of Tarazona, Jorge de Bardaxí. The basin that allegedly the Catholic King was plunged into during his baptism is still being showed off as a kind of exhibit in Sos del Rey Católico. (It certainly was the case in 1962 when the book that I am using as a reference was published) However there is no documentation that would confirm this anecdote. On the other hand, a bunch of other circumstances refute it. The bishop of Tarazona would not have a chance to intervene in the alleged baptism in Sos; the prince was born in rather dramatic circumstances, given that at the time Villarroya and Villaluenga were taken by Gastón de la Cerda, the count of Medinaceli, on March 21th, in 1452. This resulted in a threat that he would reach Calatayud and the valley of Jalón; also a special committee had been appointed in order to face the Castilian invasion, the said committee consisted of forty members, including the said Jorge de Bardaxí, bishop of Tarazona. Also the febrile measures that had been taken by king John in order to destroy the plans of his enemies: the relocation of the prince of Vianna (Ferdinand’s half-brother) to the fortress of Mall��n, in Aragon (April 13th) and his (John’s) departure for Tudela and then for Calatayud (May/June) in order to reconquer Villarroya; and finally, his disagreements with the Aragonese over the war efforts which made that campaign sterile. We can be sure that in those circumstances John didn’t think about great religious ceremony.

The family tradition rules out the village of Sos as a place of Ferdinand’s baptism. Ferdinand himself on one occasion claimed it was Saragossa where he had been baptised. Even though it may be surprising that he had had to wait almost eleven months before he was christened, his own words confirm that it was the case.

According to Zurita, who is the only source of the information at the moment, little Ferdinand was christened at the metropolitan church of San Salvador - on Sunday, February 11th in 1453. The baptism was conducted by Jorge de Bardaxí, bishop of Tarazona. Ramón de Castellón and Ciprés de Paternoy acted as his godfathers.

According to one of Ferdinand’s biographers, Jaime Vicens Vives, Ferdinand took more after his mother, both in looks and impulsive emotionality, however tenacious vigilance of his cold-tempered and calculative father, made him repress his emotions and passions under the responsibility of kingship.

About Ferdinand the Catholic:

Subsequent descriptions of Ferdinand verify that the prince was a vigorous and charming young man, who, if not exactly handsome by twentieth-century standards, was nevertheless quite attractive. An anonymous court historian later noted that Ferdinand had “marvelously beautiful, large slightly slanted eyes, thin eyebrows, a sharp nose that fit the shape and size of his face,” a slightly full, sensual mouth and lips that were “often laughing.” Although Ferdinand seems to have had a slight cast in his left eye, he had an attractive face framed by a high forehead. His well-shaped legs and an average height body were “most appropriate to elegant suits and the finest clothes.” Ferdinand was also an athlete, “a great rider of the bridle and the jennet, and a great lance thrower and other activities which he performed with a great skill and a grace.” The future king, Pulgar later observed, was also an excellent horseman who “jousted with ease and with so much skill that no one in his kingdom did it better…an avid sportsman and a man of good effort and much activity in war.” Ferdinand, like Isabella, was a compassionate individual who "felt sympathy for miserable people in unfortunate situations.” Naturally affable and gregarious, he had a “singular grace, to wit, that all who spoke with him at once loved him and wished to serve him.” Yet, despite his charm, Ferdinand was seemingly unflappable, a man in whom “neither anger nor pleasure could alter…very much.” His personal habits were similarly conservative and he exercised moderation in food and drink.

- Nancy Rubin Stuart. „Isabella of Castile: The First Renaissance Queen”

On the same day in 1503 Joanna I of Castile gave birth to her second son at the palace in Alcalá de Henares. The boy was named in honor of his maternal grandfather and became Ferdinand the Catholic’s favorite grandchild.

Ferdinand Habsburg arrived into this world in unpleasant circumstances. He was conceived during his parents stay in Spain, who had come to be sworn as the new heirs to the both kingdoms, since Juana’s older siblings and their respective offspring had passed away.

It seems that Juana and Philip had never been on good terms despite all the love she had for her husband. He had a great influence over her and didn’t show her any respect or tenderness, she basically suffered abuse at his hands, despite all this, they managed to produce children on regular basis.

Philip clearly didn’t like Spanish culture, cuisine and didn’t speak the language, and it seems like he was waiting for the occasion to run away and such occurred in October 1502, when he and his wife travelled to Saragossa to be sworn as the heirs to the kingdoms of Aragon, on October 27. On the same day when the ceremony was to take place, king Ferdinand received the news from Madrid that his wife had fallen gravely ill - in such circumstances he didn’t hesitate to leave everything and hurry to be by Isabella’s side. He named his son-in-law the deputy of the kingdom and abandoned his patrimonial realms, going to Castile. Philip was sworn as the general deputy on November 2, but the next day abandoned Saragossa, worsening the situation.

He left pregnant Juana behind, who a couple of days later decided to follow into his footsteps, most likely asking her paternal aunt Joanna (the younger sister of Ferdinand the Catholic) for taking care of everything. Despite of Isabella and Juana’s pleas Philip abandoned Spain, whereas Juana stayed with her parents.

It was a hard time for Juana who missed her beloved husband. After giving birth to her fourth child on March 10th, 1503 in Alcalá de Henares, where the princess and her parents had spent Christmas of 1502, her depression and frustration got even worse. She didn’t hesitate to do anything in her power to come back to Flanders, not taking little prince’s tender age into consideration.

Little Ferdinand was christened at San Justo (today known as Catedral de los Santos Niños Justo y Pastor de Alcalá de Henares), his grandmother Isabella donated 3.750 maravedies on this occasion.

Juana’s determination to leave Spain to be with Philip and three of their children whom she had left behind, worsened her relations with Isabella. The Queen would rather have her grandchildren brought to Spain, so they could be raised alongside their mother and their newborn brother. Juana kept crying and moaning, speaking gruffly to her beloved ones, and Isabella fell ill again due to those divergences with the heiress. The physicians of the Queen wrote a letter to king Ferdinand, who at the time was in Rosellón, on June 20th of the same year, to inform him that his wife was gravely ill once more, suffering from high fevers and they also touched upon the matter of Juana’s grave emotional state which, according to them, was the cause of deterioration in her mother’s health. Juana didn’t want to eat, couldn’t sleep and was showing signs of deep depression, being sad and gloomy, all the time missing her husband.

Isabella was afraid Juana would decide to act on her own and for her own safety had her placed at La Mota Castle in Medina del Campo. Juana couldn’t stand this fact and when she noticed the gate was closed, she refused to come back to her chambers despite the fact it all occurred in November, staying outside, even though the weather was cold. Isabella despite her poor health travelled from Segovia to Medina del Campo to comfort her daughter, who, it seems, had wanted to force her mother to pay attention to her demands. Isabella and Juana fell out during this meeting, given Juana’s behavior and the scandalous tone she used while speaking with her mother, which caused Isabella’s indignation.

Under such pressure the Queen eventually let her heiress go - the princess left Spain in spring of 1504, however given little Ferdinand was still a baby who shouldn’t participate in such voyage, it was agreed for him to be raised in Spain by his maternal grandparents.

About Ferdinand I in his youth:

In all aspects, such as nature, expression, and bearing, and all other things, he resembled the king, don Fernando, his grandfather. By nature he was predisposed to artistic things, such as painting and sculpting, and above all, to sculpting things from metal and doing gunpowder shots and throwing them. He enjoyed listening to chronicles and tales, and remembered everything (…) some of the things he said, when he was a five year old child, till nine or ten years of age, were so clever, so discreet, that everyone was amazed.

- Fray Álvaro de Osorio (x)

Sources:

“Historia Critica de La Vida y Reinado de Fernando II de Aragon”, Jaime Vicens Vives

“Między wojną a dyplomacją. Ferdynand Katolicki i polityka zagraniczna Hiszpanii w latach 1492-1516″, Filip Kubiaczyk

“Isabel la Católica: vida y reinado“, Tarsicio de Azcona

“Isabel the Queen: Life and Times”, Peggy K. Liss

“Isabella of Castile: The First Renaissance Queen”, Nancy Rubin Stuart

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#ferdinand ii of aragon#ferdinand the catholic#ferdinand i holy roman emperor#ferdinand i of habsburg

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

get to know me meme: favorite partnerships/relationships in history 3/? (1), (2)

John II of Aragon and Navarre & Juana Enríquez

Juan was the second son of Ferdinand I of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Alburquerque, and hence grandson of John I of Castile, and great-grandson of Henry II, the first Trastámara king on the Castilian throne.

He is usually seen as a man who wanted to rule, having unsatisfied desire to wield power, insensitive to almost all the emotions, breaker of any pledge, if only it turned out to be obstacle on the way to achieve his goals. This made him known as Juan Sin Fe (John The Faithless), nickname he got from his ancient foes and recent adversaries. In reality, under this coarse mask, there is a different man. We don’t deny Juan was devious, which he showed many times, when it comes to both politics and diplomacy; but this trait was a fruit of the circumstances of his time, it was the only possibility to find one’s way through the national and international passions. We could find examples of such policy in Italy, France, England and Castile, as well, where the immoral pirouette was a way to float through the uneasy waters of those hazardous times. If Juan of Aragon had given up on the opportunities that were offered to him by this system of action, in which participated such men as Louis XI of France, Charles the Bold, Galeazzo Sforza, Ferrante I of Naples, Alfonso Carrillo, etc, he would have had the same small role on the political stage, as tenderhearted and sentimental Henry IV of Castile. There are other personal traits of Juan II that have not been taken into consideration until now. In the first place; his true religiousness, confirmed by thousand details throughout his active existence; religiousness that was compatible with immense sexual appetite. Then, there was a sense of honour of the royal word, that he broke only once, during the tragic event of December 2nd 1460, when he had his son, prince of Viana, arrested at Lérida. Our assertion is proved by his maintenance of the consistent policy throughout ten years of the Catalan civil war, and his attitude towards Louis XI, during the persistent struggle for Rosellón. In the third place, his personal value, close to heroism, during the culminating moments of the drama in his life, although never impulsive, nor ready to sacrifice it in the sterile outbreak of pure virility. These characteristics can make him likeable and explain the true devotion of his close friends and supporters. But, at the same time, other aspects of his nature did not let him be truly popular and did not allow him to overcome the difficult circumstances of his life and rule, with smile on his face. We refer to the usual coldness of his temperament, restrained in eating, meticulous when it comes to clothing, cautious during the discourse, calculating in action, tough in political struggle, unchangeable in his decisions. The documents prove his passion for hunting and games, when this cerebral and reserved spirit tried to relieve his tensions. Juan of Aragon never gave himself entirely, neither to his second wife, nor to his son Fernando. Only on a few occasions we can see the exclamation of humanity in his letters; but in general, he appears to be distant, unavailable to the popular masses.

Juana was the daughter of Fadrique Enríquez, the admiral of Castile, and she was most likely born in 1425. She descended from the same branch of the bastards, sired by Alfonso XI of Castile, although she belonged to the new branch, created by don Fadrique Alfonso, master of Santiago and twin brother of Henry II of Castile. Fadrique Alfonso fathered only bastard children, which explains the vitality of the two admirals of Castile; don Alfonso and don Fadrique, grandfather and father of doña Juana. The interests of this family were not less powerful than these of the cadet branch of the Trastámaras, represented by the infantes of Aragon (Juan II of Aragon and his brothers). The Enríquez also wanted to mean something in Castile. Hence their marriages. The first admiral of Castile married Juana de Mendoza, ferocious and rich woman from the notable Mendoza clan. The second, don Fadrique, count of Melgar, Rueda, lord of Medina de Rioseco and Mansilla, wedded doña Marina Fernández de Córdoba y Ayala de Toledo. Don Diego, his father-in-law, was blacksmith of Castile and had occupied important posts at the court of Henry III; his mother-in-law, doña Inés, had vast possessions in the region of Toledo, where her family (the Ayalas) exercised power alongside the Silvas.

The marriage of Juana and Juan of Aragon and Navarre was a political union, derived from the necessity to deepen the bond between the adversaries of powerful don Álvaro de Luna (who in fact ruled in Castile), who had come back in John II of Castile’s good graces. Having arranged the marriage and having obtained the consent of Alfonso V of Aragon (Juan’s older brother whom he would eventually succeed), the future spouses were betrothed – they took each other’s hands – at Torrelobatón, on September 1st 1444, in the presence of the kings of Castile and the prince of Asturias, future Henry IV.

The bridegroom was 46; the bride 19 years old. The difference of age indicated the political nature of the union. The wedding did not take place until 1447. There were two reasons behind this delay: the dispensation was required, becasue Juana and Juan were distant cousins, and then the disaster of the Battle of Olmedo (1445), which forced Juan and don Fadrique to run off to Navarre. The bride, who was already known as queen consort of Navarre, found herself under the custody of John II of Castile, who had taken over Medina de Rioseco. She recovered her liberty on May 1st 1446, thanks to the intercession of future Henry IV, but on condition that the wedding would not be celebrated without the consent of John II of Castile.

The fire in the village of Atienza, whch was supposed to be a part of Juana’s dowry, caused another delay of the plans of her father. Finally, Juan of Aragon obtained the permission and the young Castilian woman could receive the engagement ring from the hands of her mature, Aragonese suitor, on July 13th 1447, at Calatayud. Since then don Juan felt passionate affection for his second wife. According to her contemporaries, she was a beautiful, dauntless and intelligent woman. „Enchanter”, according to her adversary, Peter of Portugal, although in the pejorative sense of this word: not a charming but deceitful woman. It was enough to win the love of her husband, who also showed her paternal affection, given she could be his daughter. Don Juan always called her ‘my little girl’.

Juana aroused fervor and hatred. Her contemporaries called her either 'the satanic female’ or 'the royal lioness’. It seems she was intelligent, energetic, astute, brave, obstinate, decisive and ambitious. According to her biographer, Nuria Coll:

’Such commended diplomat and warrior would not obtain any resonant triumph in those fields; she was impulsive, attacked openly; was intelligent in her disputes with the Parliament, but never brilliant; obstinate, tough and brave, when being brave meant to face dangers, despite fearing them, and even failing in the process.’

These vigorous outlines bring closer a woman, who by her Castillian factions and the love for her son, could even lead her husband to make a terrible political mistake. Impulsive, wild, sentimental and vain – very feminine.

“Historia crítica de la vida y reinado de Fernando II de Aragón”, Jaime Vicens Vives

Fernando [Ferdinand II of Aragon] had grown up close to this strong, indeed headstrong mother, whom her much older husband—in 1452 she was twenty-eight, he was fifty-four—loved and indulged. She brought up her son to succeed to Aragón’s crown, beginning by putting off his baptism for nearly a year, until Juan was regent in Aragón and it could be held in the cathedral in Zaragoza. There, with royal magnificence, the child was named for his paternal grandfather, Fernando de Antequera, a king of Aragón who was as well the foremost Castilian hero of the wars against the Moors in recent memory.

„Isabel the Queen”, Peggy K. Liss

Throughout her marriage to Juan, Juana was one of his closest advisers and most valuable allies, traveling with him throughout Navarre and the Aragonese realms. Juan relied on her intelligence and discretion; her prodigious familial, financial and political connections in Castile; and her tenacious and formidable negotiating skills. Juana was nothing if not intrepid and, no newcomer to politics, she shrugged off personal attacks after the death of Carlos, Juan’s son with Blanca, and succeeded him as lieutenant-general. She took full advantage of the office of queen-lieutenant that was in no way diminished by Maria’s resignation. Like Maria, Juana maintained an extensive court with a separate chancery and treasurer. Amid widespread civil unrest, she suppressed opposition, negotiated treaties, presided over parliamentary assemblies and took the side of the peasants. Unlike the six Aragonese queen-lieutenants who preceded her, Juana is noted for her active military involvement; notably, the early campaigns of the ten-year civil war (1462—72).

“Queenship in Medieval Europe”, Theresa Earenfight

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#get to know me meme#juana enríquez#john ii of aragon#juan ii de aragón#merlin

50 notes

·

View notes