#and we saw similar flower pieces like the one depicted throughout the museum

Text

Michiel van Musscher, Allegorical Portrait of an Artist in Her Studio, circa 1675-1685, oil on canvas

#ncma#omg this was really cool because it also had an interactive part to it#so like there was a recreation with a touch screen and you could press on things like the dogs and the statues and flowers and art#and it was so cool to learn more about it and to drag your finger to find it#and id love to sit down and really further deeper analyze this painting because there are so many miniscule details#i think its just so interesting that the identity of hte artist depiscted is a mystery#but i like the interpereation taht she represents an alegorical figure of painting#like shes so me#also it was funnt how the dogs were lunging at the two monkeys#but my mom brought up a great point that proportionately the cavalier king charles spaniel was signifincalty smaller and didnt see righgt#but like i loved the little angels and also that athena was in it#i love paintings within paintings so much#and we saw similar flower pieces like the one depicted throughout the museum#alos the grapes in the bottom lefthand corner look like a good artist break snack

0 notes

Text

Mental Health Art History: 5 Artworks Depicting Asylums

Yard with Lunatics (cropped) by Francisco Goya

There is such a cliche about artists and madness. Perhaps there’s a bit of truth to it: people who struggle sometimes see the world creatively; creative people may struggle to fit into the boxes that define the norm. It’s tempting to simplify this, but it’s a mistake. Many people living with mental health issues aren’t able to create at all, despite desperately wanting to. Illness takes over. And yet, there are some amazing people who persevere and create magnificent works of art despite their challenges.

In fact, a surprising number of works from famous artists were created while those people recovered in asylums, at mental health retreats, or other inpatient care. Some were created afterwards, but depicted what the artists saw in those places. If you’ve ever seen One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest then you know that art can depict those places in the most horrifying of ways. We may even want to look away. But looking at those challenging pieces can help us better understand some of the darkest times an artist has gone through.

Here are five works that specifically depict the asylum / hospital experience.

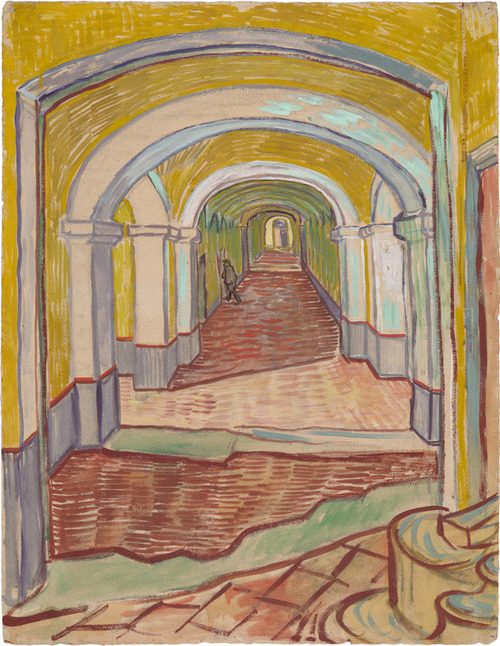

1. Corridor in the Asylum by Vincent Van Gogh

Corridor in the Asylum by Vincent Van Gogh, The Met Museum

Vincent Van Gogh created magical works of art depicting nature. His flowers, wheat fields, trees, and seascapes continue to inspire the imagination of viewers today. The painted-in-detail film "Loving Vincent" is only one of many recent examples of how artists continue to draw from his work.

The artist painted what he saw. Not all of his life was spent soaking in the beauty of landscapes bathed in natural light. He spent one terrible year of his life in the Saint-Paul de Mausole asylum. What he saw was the empty, seemingly-endless hallway represented in Corridor in the Asylum.

His letters at this time indicate that there were more than two dozen empty rooms in this corridor. He was relieved that the patients who were there didn’t harass him about his work or seem to judge his finished paintings. Still, he wasn’t exactly thrilled to have this as his inspiration. He only did a couple of other paintings of the asylum’s interior and he strictly avoided depicting what his own room there looked like, despite sharing paintings of his personal bedroom from when he was not at the asylum.

Life at the asylum was anything but pleasant. He wrote of his experience, “one continually hears shouts and terrible howls as of animals in a menagerie.” The terrifying sounds must have echoed horribly in that corridor. One patient he shared space with had auditory hallucinations and Van Gogh wrote that he seemed to be responding aloud to sounds in the corridor that no one else could hear.

Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh, MoMA

Despite the need to paint some of his experience, Van Gogh did all that he could to paint the more pleasing landscapes he remembered from his life before the institution. Whenever possible, he would sit in the asylum’s gardens, painting what he saw there instead. He arguably even created some of his best work there, including Starry Night. He was forced to imagine better times alone since nobody ever came to visit him in the asylum.

2. The Madhouse by Francisco Goya

The Madhouse by Francisco Goya at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando

Not one to sugarcoat things with a pretty name, Goya aptly called this painting The Madhouse. A similar painting from the asylum is called Yard with Lunatics. It leaves little to the imagination in terms of what his experience there was like.

Goya actually painted two versions of The Madhouse, the first in a vertical format and the second as the horizontal image most people are familiar with. In both we see the chaos of the madhouse experience. Naked men grapple with each other or with invisible deities. Chiefs and kings represent authority figures that easily suggest the horrifying power dynamics in 18th century asylums.

Comparing the earlier and later images, the difference that stands out most is that the latter is even more chaotic than the first. It’s as though the setting was eating away at Goya’s mind and he had to change the painting to reflect the madness in an even more thorough way.

Although he may have been losing his own mind there, his work is representative of an important turn in art history as it relates to mental health. He was on the cutting edge of what would emerge in the nineteenth century as a fascination with the subject of madness in art. There was a shift in society; madness had been something people gawked at for entertainment and was now becoming something to hide away in asylums. The art of the time reflects a new interest in what it means to be a part of this shifting culture when you as an artist are coping with mental illness.

3. Creative Therapy by Jacob Lawrence

Creative Therapy by Jacob Lawrence, Cleveland Museum of Art

The asylum experience doesn’t have to be horrible. Some people check themselves into an institution to get treatment and get lucky - they’re there at the right time in society, with the right doctors, and they get the care that they need. Art therapy has been a part of many asylum stays, and certain artists have thrived thanks to that creative outlet.

Depression by Jacob Lawrence at the Whitney Museum of American Art

Jacob Lawrence painted his Hospital series depicting the experiences he had while dealing with depression in an institution. Most of the work from this time is dark, as one would expect from scenes of an asylum. One of the most well-known works is Depression, which describes not only his own experiences of that mental illness but the depressed experience of being in the institution. Likewise Sedation, featuring psychiatric pills, emphasizes that there’s a clear question about whether the illness or the “cure” is the problem.

Sedation by Jacob Lawrence, MoMA

However, Creative Therapy offers a more positive take on what can happen in the asylum, particularly in terms of healthy treatment. It depicts the artist participating in an art therapy group there, led by a psychiatrist, in which he explored different aspects of his art and used color and perspective in new ways. Art does have therapeutic value, and when artists are allowed to work with it in therapy it can make all the difference in whether their creative impulse shrivels or thrives.

In a fun twist that he may have appreciated, Lawrence’s paintings have served as important discussion starters among older adults in contemporary art therapy groups.

4.Henry Ford Hospital by Frida Kahlo

Henry Ford Hospital by Frida Kahlo at the Dolores Olmedo Museum

This one isn’t quite from the asylum but it might as well have been. Frida Kahlo had spent her pregnancy on bedrest only to suffer a miscarriage that required an abortion to complete the process. That horrifying experience happened at Henry Ford Hospital.

She went into a deep depression, which she tried to process through her art. Each stage of the miscarriage and hospital experience is depicted in this painting, which began as a sketch while she was still in the hospital. The viewer’s eyes don’t know where to look and may want to turn away altogether. It’s lonely, scary, desolate, and desperate.

And although the experience didn’t take place in a traditional asylum, one can imagine that in this hospital setting she experienced that similar combination of focus on her the weaknesses of her mental health combined with inattentive care to the horrible experience of loss and depression she underwent during her two week stay there.

Although this is perhaps the most famous work depicting Kahlo’s struggles with infertility, it’s not the only one. In fact, some argue that it’s a critical theme throughout her work. This was only one of three medically-necessary abortions she had, and she suffered other miscarriages as well. Undoubtedly, this affected her mental health. The hospital bed is symbolic of the inevitable tie between physical and mental health, though historically society has often chosen to ignore this important link.

5. The State Hospital by Edward Kienholz

The State Hospital by Edward Kienholz

Edward Kienholz wasn’t a patient at an asylum. He was part of the staff. It didn’t make him any less affected by the horrors that can happen when things don’t go well in an institutional setting. The State Hospital reflects those horrors in all of their gory detail. He created this piece in the 1960s, nearly two decades after his two year internship in the hospital, but the experience was seared into his memory.

He described the asylum in terms that include the words: prison, brutality, and dirty. He even said that One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest was a model asylum compared to what he saw where he worked. His installation includes a model who was in actuality about to die from cancer, so he expressed that living in the asylum was essentially like being dead. The cavernous spaces in the heads in this piece suggest minds atrophying.

For several years prior to this piece, Kienholz’s installations were designed to shed light on individual horrors including those afflicting people troubled by mental illness. This piece added a new element though; holding society accountable for the abuses these marginalized people endured.

This post is part of our series on Mental Health Art History. We’ve previously shared two posts on artists with depression, plus posts on bipolar artists, artists with schizophrenia, and the unique condition of Misere.

By: Kathryn Vercillo

#frida kahlo#edward kienholz#jacob lawrence#vincent van gogh#francisco goya#depression#history of art#art history#mental disorders#mental health art history#mental illness#mental health#serious art history#asylums#mental hospitals

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Institute of Chicago

I attended the Art Institute last Thursday, the 14th. I entered the museum and went directly into the Photography room. I chose to go here first, not because it was right in front of me, but because I have been so interested and in love with photography since high school. At first, it was overwhelming because it was much busier than I thought it would be for a week day, but after about five minutes or so I became adjusted to the crowd and found it relaxing to wander through the hectic atmosphere.

The first piece I was attracted to was Andy Warhol’s Mao (1972). I was attracted to these photos because of the vibrant colors used. Warhol used the same portrait of Mao Zedong and used different variations of color for the skin, shirt, and background. My first thought was wondering why he used the colors he did, but I found that the use of bright colors were most likely being used to catch the eye of its audience; it definitely worked.

The second piece that caught my attention was located in the second room we entered; Paperweights. I love nature, so not only did the nature aspect of it interest me, but the detailing did as well. If you look closely, you can see the bees in there, as well as the beehive and the flowers. This piece portrays the bees to be flying around the flowers and hive, with some even resting on them. Flowers are one of my favorite parts of nature, so I really enjoyed the color and detail of them. I found this piece to be my favorite in the room because, although the others were beautifully mesmerizing with their fine detail, this weight was the only one that related to nature. This piece was titled Honey Bee Swarm with Flowers and Fruit, 2012, by Paul Stankard. I also thought it was unique that they had a whole room dedicated to paperweights of all different sizes and incredible detail in each.

Finally, the third piece I found was in the Prints and Drawings room. I couldn't quite figure out the meaning of this drawing, but I related it back to our previous Discussion Board on the elements and principles of design. This drawing, Tenth Stone (1968), depicts both the elements and principles of design very clearly. There is the use of different shapes that show the contrast of light and dark shading, along with the pattern continuing around the outside. I was attracted to this drawing because it brought up many questions for me, and left me wondering what it symbolized. It allowed me to have an open mind and really think deeper into it to try and come up with my own conclusion of what it could be and what it meant.

The piece I was least attracted to was the Shino-glazed Flower Vase by Kato Yasukage. Although the piece held an interesting shape, I found it to be very bland and boring. However, it did bring me back to our unit “What is Art?”, and allowed me to view it from the perspective of art not being beautiful but still being art. The vase represents a modern piece of pottery and is coated in a glaze finish. If you look closely at the information card, it states, “The bowl appears to be moving or spinning and mixing the colors on the surface.” I found the shape to be interesting, the colors to be pretty, and well blended, but the piece itself didn’t interest me. There was no true history behind it, and I felt it could have been more unique to the culture rather than be considered a piece of modern pottery.

The second piece that I didn't find very interesting was the Statue of a Ram, restored by Italian sculptor/restorer Francesco Franzoni (Roman Art). Much like the vase above, this statue was very plain. However, I really enjoyed the history behind it. My senior year of high school, I learned a lot about the Greek and Roman Gods and how animals were very significant to them as a means of sacrifice. The statue is a marble piece with fantastic detail of its coat, horns, face, and hooves, but as a whole it wasn't very “eye-catching”. I feel that a piece very similar to this could be seen in more places than just a museum, and because of that I don’t find it to be very unique. I think artwork should have a “one of a kind” feel to it and this just didn’t bring that feeling to me. I definitely enjoyed the history and meaning behind it more than I did the piece itself.

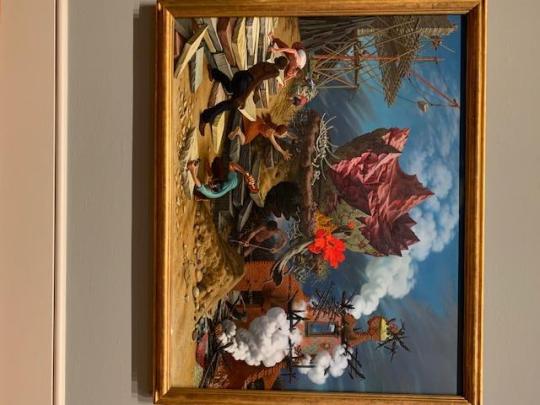

There were many pieces of artwork that brought an emotional reaction to me, but I found this one to bring me one in a different way. The Rock by Peter Blume shows about fourteen people working on a cite that seemed to have been through a major downfall. It shows the destruction of buildings and what looks to have been a boulder at one point. This reminded me of all the devastation the world has seen, from all the wars of past and present, the outcome of 9/11, and even all of the natural disasters. In this oil painting, you can see the people doing extreme manual labor and working hard to rebuild what has been destroyed. This brought a sense of sadness to me as I related this to all of the first responders that dedicate their lives to helping rebuild communities that have been effected by unfortunate events and those who risk their lives to serve our country. I found this piece to be absolutely beautiful and full of detail. I loved the realism of it and how it depicted devastation so greatly to show the true struggle people actually go through afterwards.

Responsive Time Exercise:

The piece I have chosen for my responsive time exercise was Marc Chagall’s The American Windows. This was hands down, one of the most beautiful pieces I saw throughout my time at the museum. I chose this piece because there was so much to look at and process, and felt it was the most appropriate choice for this part of the assignment. As I sat and observed the piece, I first noticed the variety and shades of color used. I loved the different shades of blue being incorporated with brighter colors such as yellow, red, and orange. The longer I sat, the more I noticed the smaller details. What caught my eye first was the person playing an instrument in the top left corner. The yellow color and black outline made it stand out the most. After I analyzed the first panel, I moved on to the next and noticed that there was mostly blue present. However, I loved the wheel of orange, yellow, and green squares bringing “life” to a darker place. The last panel below has lots of different detail. As you can see, there is a person holding a type of mask, the five lit candles, and even some sort of fairy-like image. This piece brought a sense of comfort the most I sat and analyzed it because it was located on a wall with very dim lighting but contained bright colors. I really enjoyed observing this piece because it seems as thought the more you sit and look at it, the more there is to see.

Overall, the Art Institute was a fantastic experience. I feel that it brought me more knowledge on different types of artwork and I learned about the history of many pieces. It made me dig deeper into my thoughts and really get the experience of observing and analyzing artwork firsthand. I loved everything about it and would definitely go back on my own time just to learn more about different cultures and their artwork.

0 notes

Text

Reflections of Ourselves: Ron Mueck at MFAH

Ron Mueck, “Couple Under an Umbrella,” 2013.

Ron Mueck opened at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston this past weekend, an exhibition that’s been years in the making. Mueck’s work is known around the globe for its haunting and hyperrealist figures trapped in frozen moments of contemplation. His subjects hold an essence of displacement and discomfort, bringing the viewer in to explore these expressions. “Ever since I saw his show at the Brooklyn Museum his work has been under my skin. For almost 20 years I have been provoked and impressed by Ron Mueck’s balance of the real and unreal,” states Alison de Lima Greene, Contemporary curator at the MFAH. Mueck didn’t hit the ground running as a contemporary artist. The Australian born native began his early career working as the Creative Director for a children’s TV show, Shirl’s Neighbourhood, where he also made, voiced, and operated the puppets on the show. In TV and film he eventually began working as a creator and puppeteer with such greats as Jim Henson on projects including The Labyrinth and The Storyteller. It wasn’t until 1996 that Mueck began working as a fine artist and began collaborating with his mother-in-law Paula Rego. It was Rego that introduced him to Charles Saatchi, who immediately took a shining to his work and began commissioning and collecting his latest creations.

Mueck employs a very interesting process that compels me to his work. Surprisingly, he does not compose his pieces based on real people. Seeing his work and the attention to detail, you might think that he at least works from photographs of his subjects, but that’s not the case. His works spawn from drawings and contain no real ongoing narrative. The relationships to the figures are ambiguous. Mueck captures moments, while isolating himself from the world around him during creation, often times spending a year on a figure. The subjects tend to stand still in an ambiguous place in time, remaining in a limbo. His ever changing scale from large to small, small to large presents a disjunction while pushing unrealism to realism. I found myself as close as I could possibly get to the sculptures to investigate the features, the distressed facial expressions, the pores, the complections. The choice of size is not random and even the pedestals are mandated with specific heights as to lead the viewer to see as Mueck wants you to see. The pedestals are presented in such a way that although many are very close to walls, there is just enough space welcoming you to walk around them. Interestingly enough, even the lighting and wall color is chosen specifically for each show to ensure the proper element is set to appropriately display his works.

Ron Mueck, “Woman with Shopping,” 2013.

The exhibition lacks chronological order and not intended to be scene with a theme or story line. In fact, as de Lima Greene states, “The show is as satisfying walking in from the exit as it is entering from the front.” As you walk through the show you feel heavy, very much like the people Mueck presents. Many of them stare at the ground or with a thousand yard stare, unless the viewer breaks this site line, which only passes through them. There are only two of his 40 pieces that he has made that actually came from real life. One of his first pieces, entitled “Dead Dad,” was a miniature of the body of his deceased father, and even contained Mueck’s own hair, with this being the only piece to do so. “Women with Shopping” features a woman Mueck saw on the streets of London looking blankly waiting to cross the streets. She is loaded down with groceries and a child is stuffed into her jacket, with only the head popping out of the collar. Dressed monochromatically she is almost embedded, standing for an eternal amount of time. As individuals or pairs, they merely remain in a mystery of emotion.

It’s apparent that in many pieces, things are not exactly as they appear. This can be seen in one of the anchor pieces, “Mask II,” an oversized self portrait of Mueck’s own face. Beautiful as it lays heavy and half squished for those to creep in uncomfortably close, like watching someone sleep inches from their face. The face remains unconscious and unaware of your presence. Walking around the piece you see an empty shell of a man’s head. There is no back to it and you as the viewer are to become aware of this. The mask, as it is called, is not just an ironic description of his face, but a literal one. With “Young Couple,” the work presents a teenage couple, standing close to each other, dressed ordinarily with almost pained faces. As no preset narrative is given to you, it appears the boy is consoling the young girl, as if they are both sharing this unpleasantry. The girl hangs her head with the boy, who is much taller, almost as to resting his head against hers or deciding whether to do so. The girl does not grasp or hug her partner, but has her hands dropped to her sides. When you decide to walk around the figures, you see the boy is grasping her forearm, although their bodies obstruct this fact. This made me feel immediately uncomfortable. It is as if seeing your friends from across the park engaged in a tantalizing conversation only to hear upon approach they are involved in a heated argument. One gets this feeling from many of the pieces in the show. The Mueck ‘people’ certainly wear the perfume of loneliness, but there is certainly a darkness with each piece. “Couple under an Umbrella” depicts two elderly beach goers lounging under the warm glow of a colorful umbrella. The woman sits with a slight hunch about her as her male counterpart lays flat on the floor with his head resting against her. He reclines with a clueless tranquility as she stares down upon him. As one approaches these large beach giants, you think, “oh well look at them having a nice holiday in the sun.” However, she isn’t beaming with joy. The both of them are not much of anything. Upon walking through the exhibition with London’s Charlie Clark, who has been a long time friend and has worked closely with Ron Mueck for years, he stated, “We don’t even know if they are together or if she cares for him at all.” So it comes not as a projection from myself, but from Mueck himself. There isn’t one smiling face in the collection. Its as if they have all just awoken from a deep sleep and they are taking that minute to get their bearings.

Ron Mueck, “Mask II,” 2001.

Moments of tranquility are present in a few of the works. By tranquility I mean the expressions are not entirely pained, but there certainly much to think about as you walk around with a furrowed brow. “Youth” displays an African American youth standing as he pulls up his shirt. Looking down, he peers at a wound in his abdomen. His shirt is slightly bloodied, but the wound is substantial. He stands barefoot and doesn’t seemed to be bothered by it at the moment. The didactic tells a story of resurrection and relation to Christ. Perhaps he is Christ after he arises and looks over his body only to see the laceration. Even the height of this pedestal is similar to that of a religious statue posted in a church or holy place. This may be one of the heaviest pieces in the show. It is also the only figure that is physically wounded. Maybe he has fallen off his bike or maybe the injury was inflicted upon him? There is more to ponder about, for instead of feeling an emotional pain as the others, you feel both physically and emotionally over his wound.

The entire collection of Mueck’s work has depth to it and doesn’t just rely on his ability to create lifelike people of the everyday. European art history flows strongly through the works giving moments of Lucien Freud and Albrecht Durer as you review his pieces. His work “Still Life,” an enormous featherless chicken, hangs lifeless as if about to be added into a Dutch painting surrounded with flowers, glasses of wine, and a strange looking feline. It’s clear there remains an embedded thought process with all the figures we see of Mueck’s creations. More than just the making process and welcoming our interpretations.

As you make the final conclusion through the exhibition and into the final room you are sent on your way by “Girl,” a room sized infant. The viewer is forced upon this piece and into the environment. The new child is still covered in blood and awaiting that slap on the back to bring air into the lungs. A few times around the child you take in all the details of this little-large body sprawled with its still-attached umbilical cord. Mueck provides a deep look into the time in between moments. Viewing his subjects not as objects of portraits but as a means of exposing an accurate in-depth window into human essence. Mueck’s figures are elaborate puzzles, each one with a different message to be uncovered. Within his reality, much like our own, first glances are deceiving and misguided. There are many instances of loneliness throughout the exhibition, but the individuals populating the show are far from still and alone. It’s the reflection of ourselves in the subjects that give them motion.

Ron Mueck will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through August 13, 2017.

Reflections of Ourselves: Ron Mueck at MFAH this is a repost

0 notes