#and Arts relation to exploitation and spectacle and human suffering

Text

Antlers Holst’s dedication to getting The Best Possible shot at the expense of his own life and potentially Angel’s and the Haywood’s (I don’t believe he wanted to endanger them on purpose but his lack of consideration toward their safety is very telling), seems to be driven by dedication to the Art of it. He didn’t want to do it for money or fame, he knew he would die, he seems to resent his place in the spotlight, and it’s likely the footage he shot won’t see the light of day either. He just wanted to get the best possible film of the best possible predator because that was his artistic fascination, as we can see from the scene where he is just watching videos of predators making kills.

And like, okay, on the surface that’s more sympathetic than say, the TMZ guy, or the Hollywood folks at the start of the film, or depending on how you slice it, even Jupe, who wanted to remain relevant. Because True Art is meaningful, right? It’s worth more than people.

Talented painters and directors can abuse their partners and subjects and actors, and well, the art is still good though, sometimes the abuse makes the art “better”. Artists can work themselves into an early grave and that’s valorized, the artist should say thank you for having the privilege to destroy their body in that fashion. The suffering made the art better.

(There’s been pushback on these ideas recently, but only recently, and they’re hard to unlearn. As an artist myself, the impulse to destroy my body and health in the name of my own work is one I still fight.)

Antlers just wanted to create the best form of his art, but that was not a good thing. He died horribly. Angel nearly died horribly. OJ might have died horribly. Emerald could have lost everything, and the Haywoods are left with a photo that is ENOUGH to get them through,but have most likely completely lost a much more impressive video, one that fully demonstrated OJ’s skill as an animal handler, too. In the quest for The Best Possible Thing he not only endangered others, he lost something that was perfectly good.

(I think the power dynamic alluded to here, too, with Antlers being a white male director, is very intentional as well. Who do we allow to hurt others in the name of Art? Who is allowed to be hurt? Did he learn the rules for that during film school, during his career?)

His Art ate him and hurt the people around him, just the same as Jupe’s spectacle did, as spectacle does throughout the whole film. When you put your Art before human lives, before others, and before yourself, it can be just as destructive and exploitative a force. No product is worth human blood. It’s pain all the way down.

#nope 2022#nope spoilers#nope analysis#SWEAR TO GOD I OPENED TEXT TO JUST TO WRITE A SHORT SILLY LITTLE POST AND THIS CAME OUT HELP#I know that some ppl think he was hoping for jj to spit out the camera unharmed so the haywoods could have the shot#that’s A reading but it’s not my reading. I think he was just possessed his fascinations and he felt like he Had to do it#anyway sorry to talk about antlers. i just had thoughts on the films relationship to capital-A Art#and Arts relation to exploitation and spectacle and human suffering#a thing I think about very much as I try to develop a healthier relationship to my work#nope is such a good movie. instead of brain there is nope.#long post#nope movie

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4 - Cultural Appropriation

1. How does Mbebe differentiate between “person” & “slave”? (2001: p. 235)

A slave is a person who’s body can be exploited and used for the profit of an organisation they're completely detached to. The slave is completely disregarded and given no repayment for their work - they are not a person, but a ‘thing’ (a belonging).

2. How does Mbebe relate the ‘colonized individual’ to the animal? Do you think this an effective analogy? (Mbebe, 2001: p.236)

He clarifies that the native IS a human; has bones, muscles and features that make him a human being. But as the coloniser holds a higher power, he is able to relegate the native to a state of animality. In simpler terms, the native is under the power of the coloniser and becomes nothing more than a belonging (like a pet). To me, this is an effective analogy because slaves were sold and traded as a commodity to help heighten the wealth of the colonisers. Although, i think they were treated worse than animals in some cases, slaves were abused and punished on the regular when I’m sure the colonisers had pets living in better conditions.

3. “Colonization as an enterprise of domestication includes at least three factors: the appropriation of the animal (the native) by the human (the colonist); the familiarization of man (the colonist) and the animal (the native); the utilization of the animal (the native) by the human (the colonist). One may think such a process as arbitrary as it was one-dimensional, but that would be to forget that neither the colonist nor the colonized people emerge from the circle unharmed. To this extent, the act of colonizing was as much an act of conviviality as an act of venality” (Mbebe, 2001: p.237). What do you understand by this? How could it be used to explain the ways in which ideas of culture are appropriated by global fashion systems?

It suggests that global fashion systems utilise and appropriate the culture of minority groups and use them for their own benefit, despite the harm caused to them.

4. “The colonized individual – the object and the subject of venality –introduced himself into the colonial relationship by a specific art, that of doubling and the simulacrum…” (Mbebe, 2001: p.237) Referring back to last week’s lecture on postmodernity and thinking of the idea of the ‘simulacrum’ specifically – what do you understand by Mbebe’s argument here?

I think he means that

5. Mbebe asks, “Can we really talk of moving beyond Colonialism?” (Mbebe, 2001: p.237). What do you think?

6. What does Mbebe mean by “The Process of Becoming Savage?” (Mbebe, 2001: p. 238)

I think he means the process by which the natives are animalised and how the colonisers become the ‘savage’.

7. Mbebe writes that the age of unhappiness was also a “noisy age of disguise..” (Mbebe, 2001: p.238). What do you understand by this, especially in terms of postmodernity and post colonialism?

8. How do you understand Mbebe’s phrase, “The spectacle of a world marked by unbridled license”? (Mbebe, 2001: p.239)

9.“In fact, both in the light of the advancing world and in everyday interactions with life, Africa appears as simultaneously a diabolical discover, an inanimate image, and a living sign” (Mbebe, 2001: p. 240). What do you understand by this idea and do you agree? (Think of postmodernity and semiotics particularly). How do depictions of Africa in fashion contribute to your understanding of Mbebe’s idea?

It acts as a living sign that poverty still exists, an inanimate image because most people in the first world will never suffer in this way and cannot relate and a diabolical discover because when people are educated on Africa, they are disgusted but will not take action. In the fashion industry, greenwashing and charity collaborations (such as Vivienne Westwood) just act as a middle class panacea for guilt and make us feel like we are helping.

10. Mbebe writes, “Thus we must speak of Africa only as a chimera on which we all work blindly, a nightmare we produce and from which we make a living – and which we sometimes enjoy, but which somewhere deeply repels us, to the point that we may evince toward it the kind of disgust we feel on seeing a cadaver…” (Mbebe, 2001: p.241) – What do you understand by this?

That as consumers we are feeding this inequality (here described as a fire breathing monster) by appropriating and using natives as a source of income, but we don’t like to be reminded of the harm caused, so we turn a blind eye

11. How does Mbebe suggest we understand the term, “Africa” (Mbebe, 2001: p. 242)? Do you agree? How does this relate to the ways in which you believe “Africa” is communicated in contemporary Fashion?

He suggests that Africa is not a culture, but a superficial aesthetic built inside our minds that abandons all meaning and history of the word. It isn’t a geographical place, its simply a collection of colours, patterns and symbols that we see every day in fashion, which we associate with Africa.

0 notes

Link

TITLES:

Are Prisons Obsolete? By Angela Davis

“Artists Grapple with America’s Prison System” By Sabine Heinlein

Video: “Mass Incarceration, Visualized” By The Atlantic

SUMMARIZE & REFLECT:

In Chapter 1 of Angela Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete, Davis clearly and directly outlines the rise of the prison industrial complex in the United States. She offers a rather interesting comparison regarding the difference in public opinion and outcry between efforts to abolish the death penalty and efforts to abolish the broader american prison system, and highlights the level of complacency and silence that surrounds the general U.S. public in relation to prison reform. Much of the information she discusses I have heard over and over throughout these five weeks, but I still rest in disbelief—they continue to give me chills. What I found to be really most fascinating in her initial chapter was her point regarding geography in California regarding where and how these facilities are being built. She quotes geographer Ruth Gilmore, who states:

“California’s new prisons are sited on devalued rural land, most, in fact on formerly irrigated a cultural acres … The State bought land sold by big landowners. And the State assured the small, depressed towns now shadowed by prisons that the new, recession-proof, non-polluting industry would jump-start local redevelopment.”

This quote and the location of prisons is something I have interest digging deeper into—As our collaborative group this week decided to work with the theme of constellations, both in the way Davis uses the term, to describe a woven and intertwined system of separate objects or units working in tandem, as well as the way we generally think of the word, it is clear the location of prisons create their own invisible constellation—rooted in private dealing and false promises. Much like a constellation in the sky, the specific units at play are entirely invisible during the day, and many times only partially visible at night. Additionally, constellations are deeply rooted in history, with individual stories and background—however most of this information is not known by the general public—we just know they are there. The constellation I find is a fantastic symbol in describing both the negative complex inner workings of the prison system, as well as the need for a constellation of reform and activism—a interworking of creativity, positivity, outreach, and collaboration to make the invisible visible.

Ben Briggance

In the third chapter, “Imprisonment and Reform,” Angela Davis outlines the history of human incarceration, focusing on the influence of Enlightenment on traditional European forms of punishment. Davis navigates through punishments’ transformation from public spectacle to individual reflection and in light of shifting social ideologies shaped by capitalism and growing interest in personal rights. By analyzing how increased emphasis on the individual led to a method of punishment based on the assumption that solitary existence would be the most fruitful path towards cultivating progress, Davis proves that imprisonment is a form of punishment that grew out of a very specific historical context. She quotes Charles Dickens writing that instead, “[t]hose who have undergone this punishment MUST pass into society again morally unhealthy and diseased” (48). Her discussion of the cross-influence between Enlightenment, capitalism, racism, sexism, time constructs, mental health, surveillance, and labor exemplifies her underlying argument that an alternative system of reform will rely on a network of solutions.

The concept of a constellation visually incorporates the idea of a system or network; however, our creative connection used this relationship as a metaphor to explore other structures involved in the prison industrial complex, both positive and negative. In the third chapter, Davis’ notion of a web of solutions most closely relates to the isolation of incarceration, and the need for community infrastructure both to prevent imprisonment and assist with reintegration. Responding to Davis’ quote, “The body was placed in conditions of segregation and solitude in order to allow the soul to flourish” (49), we responded by creating an artwork that relied on support from our peers; our responses thrived on collaboration, not separation.

Alyssa Scott

The last chapter in Are Prisons Obsolete? Addresses the need for synergy and creativity in order to imagine and thus create a society where prisons are abolished. In order to imagine alternatives, we must understand the prison not as a single entity but rather “a set of relationships that comprise the prison industrial complex” (106).Historical mechanisms of oppression combined with moments in history that made “sense” only in that time and must be refigured. For instance, the association of crime and punishment has become something we take for granted and accept as part of society. However, to strive towards abolition we must as Davis puts it “disarticulate” crime and punishment as well as detangle the processes that allow for the punishment and criminalization of social identities.

Each decriminalization as a tool of decarceration should be thought of as a starting point to delve into the complexity of each issue. “Alternatives that fail to address racism, male dominance, homophobia, class bias, and other structures of domination will not, in the final analysis, lead to decarceration and will not advance the goal of abolition” (108).

Angela ends the book with the Biehl story to provide a powerful example of restorative justice and the Biehl family as an example of investment in improving society rather than incarceration, responding restoratively rather than retaliating. Our creative connection works to address the idea that bold and complex relationships are both inherent to the prison industrial complex thus must be intrinsic to a radical solution.

Gabrielle Sheerer

In order to create a prison-less society, Angela Davis suggests that “a constellation of alternative strategies and solutions” is essential. The New York Times article by Sabine Heinlein, titled “Artists Grapple with America’s Prison System,” proves the vitality and efficacy of this approach; the article lists twelve artists of varying mediums and demographics who have and/or are currently creating artwork critiquing America’s prison system. In recent years, major museums like the Whitney and Moma PS1 have been curating shows featuring these artworks. The prison industrial complex’s growth has spurred increased discourse, resulting in more mainstream museums promoting prison abolition/ anti-P.I.C. themes.

The focus on the topic is wonderful; however, Ben Davis points out that “there is an icky history of using the suffering of the people at the bottom as a spectacle.” This statement is certainly true considering the potential for exploitation when artists collaborate or make works focused on incarcerated folk. The people locked inside are powerless to prevent their ideas from being misrepresented, appropriated, and stolen; therefore, it is the responsibility of the art community to ensure that a high level of artistic integrity is maintained as prison abolition movements expand.

We approached this creative connection initially looking to collaborate, and didn’t necessarily plan this format. However, it seemed appropriate that each of us could individually represent a star, making up a group constellation. The only parameter we set together was a rough estimate for a 1-2 minute video, so Ben and I approached the music with little predetermined ideas other than to create something with a mellow vibe - tying into the space theme of stars and constellations. Together, our four different mediums were meant to parallel the diversity of mediums in the NY Times article, and also the range of alternatives that Angela Davis suggests.

Ellington Peet

CONNECT:

“An abolitionist approach that seeks to answer questions such as these would require us to imagine a constellation of alternative strategies and institutions, with the ultimate aim of removing the prison from the social and ideological landscapes of our society.” (107)

Like all words, “constellation” holds multiple layers of meaning. On one level, it is the sublime and awe-inspiring: The stories of Andromeda and Pisces we have been taught since childhood. However, this narrative obscures the deeper reality of constellations as fiery stars: a violent and cruel spectacle that harms humans who approach without protection. Finally, a constellation cannot exist on it’s own – It is, by necessity, a collective arrangement.

Through these multiple meanings, and Davis’ consistent use of the word in her book, we discovered a deep resonance between constellations and incarceration. While politicians and citizens legitimize mass imprisonment through rhetorics of “safety,” we obscure a deeper reality of trauma and violence. Additionally, as Davis argues, in order to counter this mass trauma, we must act collectively: Individualism was the basis of Prison Reform, therefore it cannot be the primary basis for freedom.

For this reason, we decided to work collaboratively. Utilizing our distinct trainings – poetry, music, and dance – we hoped to make a video that speaks to this power of collectivity. Though important individually, each art form takes on a more nuanced set of meanings when viewed as a whole. Finally, we were inspired by films ability to effectively synthesize these disparate art forms, particularly after watching The Atlantic’s short film, “Mass Incarceration, Visualized.”

Colleen Hamilton-Lecky

0 notes

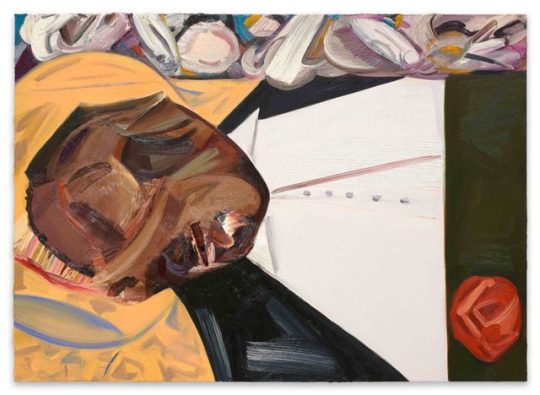

Photo

The controversy of Dana Schutz’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial and black death as spectacle

Hannah Black’s open letter “To the curators and staff of the Whitney Biennial”:

I am writing to ask you to remove Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.

As you know, this painting depicts the dead body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all. In brief: The painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.

Although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist—those non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.

Emmett Till’s name has circulated widely since his death. It has come to stand not only for Till himself but also for the mournability (to each other, if not to everyone) of people marked as disposable, for the weight so often given to a white woman’s word above a Black child’s comfort or survival, and for the injustice of anti-Black legal systems. Through his mother’s courage, Till was made available to Black people as an inspiration and warning. Non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture: The evidence of their collective lack of understanding is that Black people go on dying at the hands of white supremacists, that Black communities go on living in desperate poverty not far from the museum where this valuable painting hangs, that Black children are still denied childhood. Even if Schutz has not been gifted with any real sensitivity to history, if Black people are telling her that the painting has caused unnecessary hurt, she and you must accept the truth of this. The painting must go.

Ongoing debates on the appropriation of Black culture by non-Black artists have highlighted the relation of these appropriations to the systematic oppression of Black communities in the US and worldwide, and, in a wider historical view, to the capitalist appropriation of the lives and bodies of Black people with which our present era began. Meanwhile, a similarly high-stakes conversation has been going on about the willingness of a largely non-Black media to share images and footage of Black people in torment and distress or even at the moment of death, evoking deeply shameful white American traditions such as public lynching. Although derided by many white and white-affiliated critics as trivial and naive, discussions of appropriation and representation go to the heart of the question of how we might seek to live in a reparative mode, with humility, clarity, humor, and hope, given the barbaric realities of racial and gendered violence on which our lives are founded. I see no more important foundational consideration for art than this question, which otherwise dissolves into empty formalism or irony, into a pastime or a therapy.

The curators of the Whitney Biennial surely agree, because they have staged a show in which Black life and anti-Black violence feature as themes, and been approvingly reviewed in major publications for doing so. Although it is possible that this inclusion means no more than that blackness is hot right now, driven into non-Black consciousness by prominent Black uprisings and struggles across the US and elsewhere, I choose to assume as much capacity for insight and sincerity in the biennial curators as I do in myself. Which is to say—we all make terrible mistakes sometimes, but through effort the more important thing could be how we move to make amends for them and what we learn in the process. The painting must go.

Thank you for reading,

Hannah Black

Artist/writer

Whitney Independent Studies Program 2013–14

The controversy according to artsy.net (by Antwaun Sargent)

The controversy according to artnet.com (by Lorena Muñoz-Alonso)

The controversy according to Afropunk (by Hari Ziyad)

A rejoinder by Coco Fusco:

I would never stand in the way of protest, particularly an informed one aimed at raising awareness of the politics of racial representation, a subject that I’ve tackled in various capacities for more than 30 years. A group of artists staging enraged spectatorship before an artwork in a museum strikes me as an entirely valid symbolic gesture. A reasoned conversation about how artists and curators of all backgrounds represent collective traumas and racial injustice would, in an ideal world, be a regular occurrence in art museums and schools. As an artist, curator, and teacher, I welcome strong reactions to artworks and have learned to expect them when challenging issues, forms, and substance are put before viewers. On many occasions I have had to contend with self-righteous people — of all of ethnic backgrounds — who have declared with conviction that this or that can’t be art or shouldn’t be seen. There is a deeply puritanical and anti-intellectual strain in American culture that expresses itself by putting moral judgment before aesthetic understanding. To take note of that is not equitable with defending whiteness, as critic Aruna D’Souza has suggested — it’s a defense of civil liberties and an appeal for civility.

I find it alarming and entirely wrongheaded to call for the censorship and destruction of an artwork, no matter what its content is or who made it. As artists and as human beings, we may encounter works we do not like and find offensive. We may understand artworks to be indicators of racial, gender, and class privilege — I do, often. But presuming that calls for censorship and destruction constitute a legitimate response to perceived injustice leads us down a very dark path. Hannah Black and company are placing themselves on the wrong side of history, together with Phalangists who burned books, authoritarian regimes that censor culture and imprison artists, and religious fundamentalists who ban artworks in the name of their god. I don’t buy the argument offered by a pair of writers in the New Republic that the call to destroy Schutz’s painting is really “a call for silence inside a church”; the vituperative tone of the letter hardly suggests a spiritual dimension — not to mention that the biblical allusion to silence in the church seems to come from a Corinthians passage about requiring women’s submission and obedience! I suspect that many of those endorsing the call have either forgotten or are unfamiliar with the ways Republicans, Christian Evangelicals, and black conservatives exploit the argument that audience offense justifies censorship in order to terminate public funding for art altogether and to perpetuate heterosexist values in black communities.

Read all of Fusco’s rejoinder.

#emmett till#black lives matter#black death#whitney biennial#Dana Schutz#hannah black#antwaun sargent#Lorena Muñoz-Alonso#hari ziyad#coco fusco

0 notes