#also his grief reminds me of Macbeth’s when Lady M dies

Text

Today I am thinking about the fact that when Romeo receives the news of Juliet’s death (“death”) he just shuts down. The words on the page almost seem cold and empty; they have none of his usual flair or fire. And you’re almost tempted to ask “does he even . . . care?” and then you realize that he can’t hold a thought in his head to its conclusion, that he can’t focus on one thing at a time, that he speaks in short fits and starts because he’s utterly wrapped in a dark fog of despair, the likes of which he’s never known before. He can’t be dramatic because he’s ALWAYS dramatic; this hits and hurts him so much more profoundly than anything he’s ever known and words are truly not enough to express the depths of his sorrow or despair. And so he clings to blind and violent action as his instant recourse.

And it’s masterful (and gutting) the way that Shakespeare turns his usual eloquence on its head like that and takes away his ability to put into words what he’s losing. It’s transformative, and not for the better or the more beautiful. In an awful way, Juliet’s death hardens Romeo instantly into a man not a boy: a man of action, violence, and despair. Grief alone has been able to transform him into the kind of man Verona and this feud have expected him and pressured and raised him to be: a man whose only response is violence. He uses all his remaining wits and strength and purpose to go to her tomb. And there is something about his journey to her that is that of the bird flying home to its nest because there is still something about Romeo that is a boy (only the love twisting into grief in his heart) but there is also something about his journey that is that of a man running straight off a cliff into a pit of snakes, into the arms of violent destruction, because love itself has finally died and nothing else remains.

#romeo and juliet#this is. TOO MUCH FOR ME#and obviously Romeo is not RIGHT#but if Juliet is dead he is right that love is dead#no one else in the PLAY knows what love is like she does#because the families (and as Maria said yesterday even the Prince!!!) have been steeped in violence so long#also his grief reminds me of Macbeth’s when Lady M dies#at first you’re like ‘really? that’s all you have to say?’ and then you realize#anyway I am CRYINg In this Chili’s tonight

459 notes

·

View notes

Photo

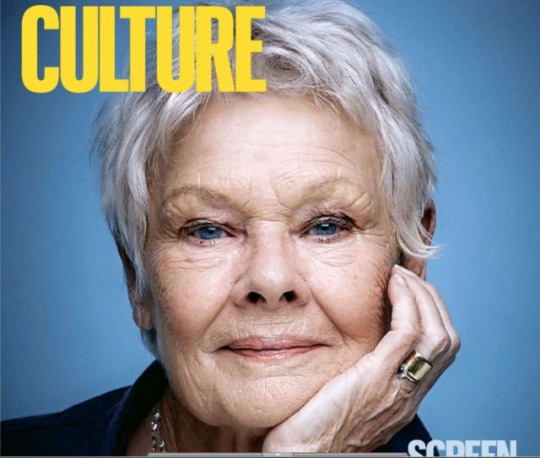

it’s only a partial screenshot - but it’s a gorgeous photo. if you can lay your hands on the culture section of today’s times you’ll see the whole picture in all her glory.

Judi Dench on playing Victoria again

The diamond dame is celebrating 60 years in the acting biz with a second pop at playing the queen on film. This time with a rather beautiful young man — ‘Who wouldn’t?’ By Louis Wise

It was on September 9, 1957 that Judi Dench made her debut as Ophelia in the Old Vic’s Hamlet. Over the six decades since, she has taken hundreds more roles, won dozens of awards and plaudits, and become embedded in the national psyche. What is the greatest misconception about her? A pause. “‘National treasure,’” she purrs, in that distinctive Denchian croak. “F****** ‘national treasure’!”

We are sitting in the library of the Covent Garden Hotel, in London, where she is doing promotional duties for her latest effort, Victoria and Abdul. At 82, she looks gorgeous, if a little shaky: the rattle of the bangles on her arms is complemented by a persistent cough, accompanied by streaming eyes. (She dismisses the suggestion that it’s hay fever, but isn’t sure what it is instead.) She is dressed in the expected boho-Denchy pale linen and has tiny feet, her toenails painted scarlet. Will she celebrate her 60 years in the biz? “Oh, I doubt it, no.” A small pause. “I might have an extra glass of champagne that day.”

Dench is, as you’d probably expect, both warm and brisk from the off, but the first time she gets properly animated is when I mention the “n******* t*******” tag. We know she hates it, she says it all the time, but I only bring it up to ask whether it’s an albatross when she’s looking for roles. As soon as the phrase even looms, though: “Oh, please don’t say that! Everyone says it, everyone. It’s horrible, it’s awful. I hate it.” So, yes, it’s the biggest misconception about her. She later qualifies her answer. “I’d like much more to be the Notes on a Scandal woman than the Marigold Hotel woman, do you know what I mean?”

It’s bizarre to define Dench’s career in terms of two roles, considering this is a woman who has been Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, Lady Macbeth, M from the Bond films and, yes, Queen Victoria, but you can see what she’s getting at. In 2007’s Notes on a Scandal, Dench was exceptional as the tortured, torturing Barbara Covett, unhealthily obsessed with her younger colleague (played by Cate Blanchett); in 2011’s The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, she had a far more fragrant, floaty time in the silver-surfers drama set in India. It’s the former that she hungers for, even now. “Oh, I loved it! I loved every second. That’s the part I’m always looking for.”

Furious old lesbian roles not being more forthcoming, though, she is back to playing the queen-empress for a second time, after Mrs Brown. Would she have liked to play any other crowned heads? “No, I don’t particularly want to play queens. You don’t actually think of Cleopatra [‘Cleoparrtra’] as a queen. You just think of her as somebody who behaves rather badly, now and again. But — if there’s a queen that behaves really badly...” She mulls it over. “You know, I long to find this film where this woman walks a tightrope and turns into a dragon. If that part is around, and she happens to be a queen, that’s fine, too.”

Sadly, perhaps, Victoria and Abdul does not require this of her. It’s another anniversary of sorts, since Mrs Brown dates from 1997, and it was this that launched her surprising, late-blooming Hollywood career. (It was a TV movie for the BBC until Harvey Weinstein snapped it up and put it in cinemas, earning Dench the first of seven Oscar nominations in the process.) “Is it 20 years since I did Mrs Brown?” she asks. Yes, isn’t it odd? It seems only about 12 years to me. “It seems like 40 to me.”

The role is not the only similarity. Like Mrs Brown, Victoria and Abdul charts the unusual relationship the monarch had with a man in her long years of widowhood. Whereas the first film concentrated on her intimacy with John Brown, roughly covering the 1860s to the 1880s, the second starts up in the late 1880s, when Victoria, even older, even grumpier and even more alone, is suddenly taken with a young Indian servant, Abdul Karim (played by the Bollywood cutie Ali Fazal), who has been brought over from Agra. Victoria makes him join her private household and he becomes a favourite, educating her on the country of which she is empress; she designates him her “Munshi”, an Urdu word for “teacher”.

All lovely, but of course this goes down like a lead balloon with the monarch’s stiff inner circle, for reasons of class and colour, and things get tricky and sour. The film, directed by Stephen Frears and scripted by Lee Hall, is a game of two halves: naughtily funny to start, achingly sad at the close, as Victoria reaches the end of her life and their friendship reaches its limits. Dench says she had “no intention” of ever returning to Victoria, but that the script won her over.

“I thought it just gave another huge insight into her life. The whole episode with John Brown was strange, but I thought it was totally understandable, which I believe that this relationship was, too. [Here was] somebody that she found, and she could just talk to him, and he talk to her, and she could ask questions and learn something.”

How much of Victoria’s rapport with Karim is an echo of the John Brown episode? “I think the need is the echo,” she replies. After Prince Albert’s sudden death, Victoria was left alone, without a man she could be utterly devoted to. “Yes, she liked a chap around,” Dench nods — which, with the lusty Victoria, is an understatement.

No hint of sex here, but certainly romance: a man “with whom she could actually relax, all formal protocol cancelled. A real, proper relationship, being able to speak her mind to somebody — I think that’s what it was. Apart from the fact that he was an extremely beautiful young man. Who wouldn’t?” She smiles gleefully. “If Ali [Fazal] walked in now, you wouldn’t recognise me. I’d be a spring chicken, all over the place. So beautiful.”

As she says, she is not quite a spring chicken today, but she fires on nearly all cylinders. The main thing that strikes me is how funny she is, specifically her timing and delivery; she can make all sorts of lines work. It reminds me that my first experience of Dench wasn’t as the great Hollywood matriarch, but on a much cosier and smaller scale, in the BBC sitcom As Time Goes By.

Time has indeed gone by, though she doesn’t want to moan about it. There are, of course, her eyes: for years now, her eyesight has steadily gone, as she suffers from macular degeneration. It’s always bad, but it’s getting worse. She says she’s finally going to tackle audiobooks, as she can’t read novels any more. I am politely surprised — I would have thought she had fathomed that a long time ago. “Yes, but you know, you think you can struggle on. But last week we ran over the only pair of glasses of mine that remotely worked.”

Television, though, she still tries at. ���We’ve been watching Poldark, which for me is Pol-very-very-dark. I keep going, ‘Who is that speaking?’ I remember Robin Ellis doing the original all those years ago. You don’t remember,” she says, appraising me. “You were in short trousers then.” I wasn’t even born, I’m afraid. “You weren’t born? Oh, thanks so much. Thank you so much.”

If she can laugh about it, there are sadder sides, too. Recently her eldest brother, to whom she was close, died. She was close to her whole family, with whom she had a “glorious” time. “I’ve thought a lot about it recently. I keep wanting to refer back, and there’s no one to do that with. It is hard when that happens.”

In many ways, though, she seems to have been very lucky: she had a blissfully happy 30-year marriage to the actor Michael Williams, who died in 2001, and with whom she had a daughter, Finty, who has provided her with a grandson, Sammy. I ask Dench when she was happiest in her life.

“Oh, I don’t know. I have a happy nature. I have been very, very unhappy, like everybody, but usually I have quite a sunny nature, which is something you don’t manufacture. It’s either something you’re born with, or you’re not. And I think that comes from my parents. They had great, great senses of humour.” Her childhood in Yorkshire sounds glorious: play-acting and cycling and going to the theatre (her parents were involved in am-dram), and when she went to boarding school nearby, that was “heaven”, too. So you didn’t even have a tricky adolescence?

“Well, I remember my mother saying to me when I was at art school, ‘You are without doubt the most intolerant person I’ve ever met.’ I think I found fault with everything. And I remember not being able to say anything back, and just looking out of the window. She said it to my back.” A pause. “It’s very good to be told that early.” Did you take it on board? “I hope so. Because I think I am quite tolerant now. To a certain extent.”

What can’t you tolerate? “I can’t tolerate the bastardisation of the English language,” she says with a cackle. “I’m always screaming at Sammy. He says, ‘I was laying there.’ And I say, ‘Hens lay — lying, lying!’” She also says that she doesn’t like it when an actor turns up to rehearsals unprepared: “It’s not up to you to take up another person’s time.” This is easy to visualise. She says often how much she loves working in an ensemble, but you can be sure that once she’s in one, the dame is very much a dame.

I ask who, of all the people she has met, she’d like to talk to again. “Oh, Gielgud. So funny! Terribly funny and irrelevant — I mean irreverent! Oh, he would send me up for that.” Also, she would like to meet Shakespeare, “to see if he had any more plays up his sleeve, or doublet”.

Lots of interviews dwell on Dench’s grief after losing Williams (and her new relationship with David Mills, whom she met at the opening of his squirrel sanctuary). But I was interested in how she and Williams met, and how it felt at the time. She met him in a pub on Drury Lane, in the early 1960s. Did she find him attractive at first?

“No, we just laughed a lot. And we went on meeting like that occasionally, and having a good laugh.” Things came to a head when he joined her on a theatrical tour in Australia, and he took it upon himself to propose; they finally wed in 1971. Had it been her ambition to be married? In the early 1970s, I’d assume mid-thirties was late for such a thing, especially for a woman wanting children.

“Oh, I wanted to be married and have six children! That’s a big regret in my life. But at least I have one divine girl, and a grandson.” But was she panicked at all about whether she’d settle down? You see, Judi, I’m 34 and single. “No, 34 is fine,” she says firmly. “It’s fine.” Yes, yes, but did you feel that way at the time?

“Oh, I know, but I was in love so, so much, all the time,” she replies dreamily. Before Michael? “Oh yeah. Mmm.” With varying levels of success? “Oh, hopeless.” Unrequited? “No!” She gives a cough, which for once might be a planned one. “No. Requited! It was just the most glorious time, a wonderful, wonderful time,” she says. “So don’t give up because you’re 34. Certainly don’t.”

The Munshi’s tale

Victoria and Abdul’s story began in 1887, her golden jubilee year. As part of the celebrations, she was presented with two Indian servants from Agra. Victoria took a shine to the more handsome of the two and integrated him into her household. For Abdul Karim, a humble clerk, this was a vertiginous elevation, though he balked at the menial work she demanded and asked to be sent home. The queen, 68, besotted with the 24-year-old, refused.

Very soon, she promoted him from simple manservant to “Munshi”, or teacher, asking him to give her lessons in Hindustani. The fruits of these labours are her Hindustani Journals, all 13 volumes of which are at Windsor Castle. They are a symbol of the empress-queen’s fervour for all things Indian, as encouraged by Karim — not least a good curry. Chicken and dal were her favourites.

Victoria’s family and entourage detested Karim. They railed and plotted against him, even threatening a mass walkout in 1897, but Victoria stood firm. When she died, however, retribution was swift. The new Edward VII ordered that all trace of Karim be removed; the king’s sister Beatrice excised all signs of him from her mother’s diary. Karim was sent back to India, where he would die eight years later in 1909, aged 46. Luckily, though, he left a diary with his relatives — a huge help to the journalist Shrabani Basu when she started researching his extraordinary story a few years ago. It’s on her book that Stephen Frears’s film is based.

A small trace of Karim survives at Victoria’s private retreat on the Isle of Wight, Osborne House. Two photographs hang in her dressing room, one on top of the other: one is of John Brown, the Scotsman who guided her through the darkest years of her widowhood; the other of her dear Munshi, who consoled her thereafter.

#It was on September 9 1957 that Judi Dench made her debut as Ophelia in the Old Vic’s Hamlet. Over the six decades since she has taken hundr#judi dench#gorgeous photo#1837#27aug2017

24 notes

·

View notes