#al qaeda in the islamic maghreb

Photo

(via Weak States and Loose Arms: Lessons and Warnings, from Afghanistan to Ukraine - War on the Rocks)

WEAK STATES AND LOOSE ARMS: LESSONS AND WARNINGS, FROM AFGHANISTAN TO UKRAINE

KERRY CHÁVEZ

AND

ORI SWED

JULY 12, 2022

COMMENTARY

As the United States withdrew from Afghanistan last August, images of Taliban soldiers decked out in American kit frequently recurred on global media. Social and news media fretted that the Taliban had become the only terrorist group with an air force. Much of the ado might be about nothing. The complex and exquisite platforms that provoked the most concern (i.e., Black Hawks and light attack airplanes outfitted with Hellfire missiles), require capacity to train, field, and maintain that is probably beyond the Taliban.

The large volume of small arms and light weapons the United States left behind is more mundane yet more meaningful. Based on the 2017 Government Accountability Office and 2020 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction reports, the cache exceeds 650,000 pieces ranging from rifles to rocket-propelled weapons. Unlike Black Hawks, they require little training and no expertise to use. Even fresh Taliban foot soldiers know how to fire an AK-47. Beyond that, their qualities, combined with state weakness, have led to weapons diffusion into the surrounding region, sparking and inflaming more violence. In short, the enormous stockpiles left behind have generated a “regional arms bazaar” for terrorists, criminal elements, and insurgents.

This has happened elsewhere before and will again. The risk that weapons deployed in the Russo-Ukrainian War, whenever and however it ends, will disperse across Eastern Europe and Central Asia is particularly disquieting.

BECOME A MEMBER

Weakly governed states — whether weakened by corruption, conflict, or collapse — have looser arsenal integrity, making them more subject to opportunistic substate groups. Their weakness allows apertures into the black market, the size and reach of each being a function of how well-armed the state and how weak its stockpile security. On the smaller end, corrupt nations control a more trickling leakage of arms into the black market to a shortlist of proxies and clients, usually with conditionality. Depending on the scale, actors, and victors, post-conflict scenarios can range from a few loose arms to largescale diffusion.

On the extreme end of the state weakness spectrum, collapse generates the most pointed proliferation events, especially if the nation was well-armed. We focus on these moments as sudden, immense shifts in black market volumes and movement. Following collapse, stockpile security folds along with the government’s legitimacy, institutions, and services. In addition to the usual black-market tradesmen ready to plunder national arms depots, many regular citizens join out of desperation as a new anarchy takes hold. In fact, weak governance becomes a simultaneous cause and consequence of weapons looting since the state can neither provide security for citizens nor secure stockpiles from citizens. These reinforcing conditions — elevated demand, vulnerable supply — intensify the siphon of weapons from the state to the local black market.

The larger the stockpile and the more suddenly it devolves to nonstate actors, the more intensely it tends to diffuse into the surrounding region. Local actors arm themselves and warlords offer provincial security, but weapons are also a lucrative commodity. In insecure environments, sales might purchase safety, basic goods and services, or escape. They might buy loyalty and solidify substate alliances. With a sated national market, would-be customers having plundered their own caches to surplus, illicit entrepreneurs look abroad for markets of higher profit and demand.

And there is demand. Considering the case of Libya in 2011, for example, demand might come from rebels (Darfur fighters), insurgents (Seleka in Central African Republic), militias (Azawad factions), terrorists (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), criminals (Tibesti gold rushers), gangs (Nigerian “bandits”), or even civilians seeking self-defense. Although not sufficient for violence without motive, arms are a necessary precondition for violent campaigns of any kind.

We point specifically to small arms and light weapons. They are distinctly suitable for sale, in contrast to heavier systems (recall the missile-laden light attack planes in Afghanistan, for instance). The capacity requisites for complex weapons render that market significantly smaller and more specialized. Many ragtag looters lack access or would not risk exposure to such in-groups. Selling nations also maintain end-use monitoring on conventional platforms, making it even riskier. Small arms and light weapons, however, are financially and technically approachable even for foot soldiers. Existing monitoring mechanisms for the latter are also fragmented and ineffective, dramatically reducing the risk of being caught.

The qualities of small arms and light weapons also make them distinctly amenable for trafficking. Also unlike heavy weapons, they are small and modular enough to be hidden at checkpoints and among “ant-trade” transports. (Ant-trade is a term of art for the most common form of illicit weapons trafficking: Imagine ants following their routes, spaced out with one load at a time. Traffickers mimic this to avoid riskier, costlier interceptions.) They are more durable, needing minimal upkeep and maintaining value across exchanges and time. They are also more serviceable, requiring minimal cost for replaceable parts and ammunition.

The combination of weak governance, local incentives, and the attributes of small arms and light weapons ejects them into the surrounding region following collapse. This influx of weapons — larger and more diverse than the usual sources that illicit actors tap — augments substate forces and their fighting capacity. Since more than 90 percent of contemporary armed conflicts are now internal, and since small arms and light weapons are the currency of substate violence and its spread, these massive proliferation moments are grim.

Depending on the destination, dispersion could mean a number of things. We return to the Afghanistan case to demonstrate a few of them. Dispersion might simply exacerbate instability in weak zones, like it has in Afghanistan itself and certainly pockets around it in Pakistan, Iran, and India. Weapons diffusion might revitalize insurgent efforts, such as that of the separatists in Baluchistan, or strengthen existing terrorist organizations, like the Islamic State affiliate in the region and al-Qaeda. It might create political space, full of arms and anarchy, for new terrorist groups and rebellions to arise. For instance, Afghan tribal groups are coalescing in opposition to the Taliban. Perhaps worst, it can incite or bolster civil war. Factions within the Taliban are vying for dominance, and it is unclear how far the internecine struggle will escalate. We also find it feasible that Western arms abandoned in Afghanistan could be trafficked to existing conflict zones in Iraq, Syria, or Yemen, especially with Iran’s support. The upshot is that the supply of small arms and light weapons interacts with the demand dynamics at trafficking terminuses, yielding a spectrum of potential outcomes.

To summarize, weak governance exposes military stockpiles to eager nonstate actors who sell the surplus of what they can (small arms and light weapons) where they can (often elsewhere) to whom they can (violent nonstate actors of all stripes). On average, the surge of diffusion correlates with a swell in violence at trafficking terminuses. Of course, this is one process among others that can take place amid state weakness, and only one means of weapons dispersion among others. Nonetheless, it is a likely and consequential one on the heels of dire conflict or collapse. It is also an empirically precedented one, playing out in the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union and the 2011 crumbling of Libya.

The collapse of the Soviet Union is a prime example of the dispersion consequences from a state armed to the teeth. The dismantling of Soviet arsenals sourced many illicit weapon bazaars and sprawling proliferation. Scholars emphasize that disaffected and desperate nonstate actors ransacked, trafficked, and sold billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of tons of small arms and light weapons across the region — Abkhazia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, Tajikistan, Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Ukraine. Kaliningrad in particular, geographically and politically distanced from the Soviet Union, became an immense illicit arms marketplace. Many of these locations became seedbeds of instability.

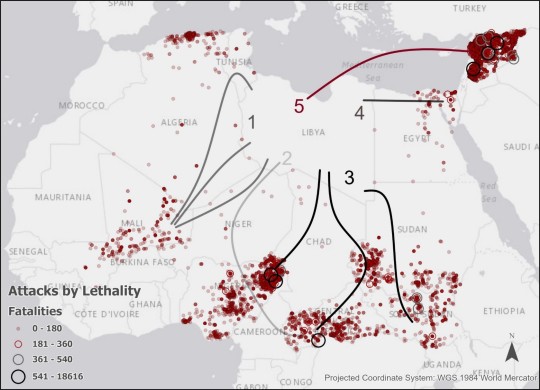

Commensurate with stockpile sizes, the breakdown of Libya followed a similar trajectory on a smaller (though still alarming) scale. In a recent study, we plot the illicit small arms and light weapons trafficking routes after Libya’s 2011 collapse. Libya had one of the largest arsenals in Africa, and its looting led to a profound episode of proliferation. Like the Soviet case, small arms and light weapons quickly crossed borders and fueled conflicts in the region.

Figure 1. Conflict events, scaled by lethality, after Libya’s collapse overlaid with illicit small arms and light weapons trafficking routes, from Oct. 20, 2011 – 2017. (Graphic by the authors)

We traced four major overland routes across 11 countries in the surrounding Sahara-Sahel and one air and maritime route into the Middle East. Violence clustered and significantly intensified at their terminuses, visible in Figure 1. In particular, newly armed Malian rebels seized several major cities and declared the Azawad independent within eight months of Libya’s collapse. Boko Haram became a key consumer of Libyan weaponry. The struggle over South Sudan escalated with the influx of weapons. Violence in the Sinai surged including the appearance of new armed groups. Libyan arms also ended up in Syria, the site of a vicious civil war.

These cases show the importance and implications of loose stockpiles. The same processes are afoot in Afghanistan and will persist. Turning to speculation, we see potential for a similar danger down the line in Ukraine, which bears some features of a weak state (especially its eastern regions). Defined as a diminished ability to exercise sovereignty in a territory, the sustained presence of Russian forces in the country and the failure to provide basic services and rule of law in areas that Ukraine still holds indicate some degree of weakness. A 2021 Small Arms Survey report determined that there were already large quantities of loose weapons and ammunition in Ukraine. Since the war began, nations have rapidly poured more basic and advanced small arms and light weapons and other weapon systems into Ukraine to reinforce fighters. Intentionally — Ukrainian resistance is a patchwork of diverse fighters — many systems are high-end yet simple to use. For example, the Javelin anti-tank missile and the Switchblade anti-tank portable drone both require less than an hour of training to use.

What will happen to all the dispensed armaments when the fighting stops? The Russo-Ukrainian War remains hot, so imagining its aftermath is more uncertain, but many might be illicitly dispersed. Whether Ukraine collapses, attains a decisive victory, or negotiates a settlement, the future of its arsenal is still worth consideration. The saturation of small arms as a national defense strategy will be difficult to undo, especially for a relatively weak state. Officials will attempt to monitor and secure the increasingly massive military arsenals. The states that sold the arms and domestic Russian and Ukrainian authorities will devote initial and primary efforts toward conventional, sophisticated platforms: aircraft, tanks, and heavy weapons, for example. In the meantime, the largest risks of proliferation lie with small arms and light weapons on hand to civilians, foreign fighters, and soldiers who might behave opportunistically as the smoke clears.

On humanitarian, geopolitical, and financial fronts, this is and should be of grave concern to states, practitioners, and scholars. As one conflict ends, the last thing stakeholders and communities need is for more to emerge in the same unstable vicinity. Thus, understanding this hydra model of war is critical to head off the diffusion of violence. This is especially true in the wake of state collapse, a rare but immense phenomenon that spills over borders more powerfully.

We offer three prescriptions to structure efforts to stem the spread of illicit small arms and light weapons during peak proliferation events. First, remember that illicit markets are regionalized. The neighboring nations that will receive the brunt of repercussions have incentives to step up to secure loose stockpiles. Other weak states have urgent reasons but weaker capacity to contain spillover, while strong states less likely to see direct negative effects ideally will contribute stockpile-security efforts in order to uphold norms and regional stability. If capacity is short or efforts are fragmented, neighbors should activate their alliance and institutional networks to help curb potential spillover. Finally, major powers with strategic or economic interests in the region might be motivated to help arrest these bursts of weapons dispersion that can have long legacies.

Second, these periods of explosive trafficking appear to be short-lived. Eventually, even vast stockpiles dry up. National dynamics shift. In Libya, local groups consolidated by 2014, leading to an increase in internal demand and consequent decrease in illicit arms outflows as territorial clashes escalated. In the loose interim, though, small arms and light weapons enabled footholds and forward movement for manifold nonstate actors. This temporal trait implies that mitigation programs should be implemented as soon as possible as stockpile insecurity mounts (insofar as shards of sovereignty allow) and certainly in the immediate aftermath of collapse or war. A boon to the domestic politics of participants, leaders can pronounce short-term commitments to high-value intervention.

Third, mediating factors determine the severity of small arms and light weapons spillover. To use an epidemiology analogy, some have greater resistance to a spreading phenomenon whether by genetics, exposure, or baseline health. Pockets of regional demand, rebel group (dis)unity, foreign fighter movements, regional capacity and coordination, the strength of interdiction techniques, the presence of external peacekeeping forces — each of these scale and structure the regional impact. These spatial traits imply that mitigation programs should be targeted based on knowledge of native inoculations along likely trafficking routes. For instance, paths to and terminuses rife with instability should be reinforced while well-governed zones can be deemphasized. Long, porous borders present a particular challenge of coverage and coordination while manageable, impassable, or intelligence-rich ones can stand alone. Stakeholders can use preexisting trafficking routes as a template, tribal travel routes and folkways as further clues, and the distribution and dynamics of regional militants as hinge points.

Altogether, given the high impact of small arms and light weapons set against scarce security resources following conflict or collapse, regional powers and their partners should amplify stockpile security in the immediate short-term in gaps of greatest weakness. This might entail targeted contingents of boots on the ground to fortify stockpiles or bombing campaigns to eradicate them. It will cost regional and global powers to safeguard insecure arsenals, but in the end it will cost far less than letting them loose to ignite violence anew.

BECOME A MEMBER

Kerry Chávez, Ph.D., is an instructor in the political science department at Texas Tech University. Her research focusing on the domestic politics, strategies, and technologies of conflict and security has been published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Defence Studies, among others. With practitioner and law enforcement experience as well as working group collaborations, she produces rigorous, engaged scholarship.

Ori Swed, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the sociology department and director of the Peace, War, & Social Conflict Laboratory at Texas Tech University. His scholarship on nonstate actors in conflict settings and technology and society has been featured in multiple peer-reviewed journals and his own edited volume. He also gained 12 years of field experience with the Israel Defense Force as a special forces operative and reserve captain, and as a private security contractor.

Image: U.S. Navy

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The attempted coup in Niger could fuel extremism across West Africa. The instability caused by the coup could provide a foothold for extremist groups such as Boko Haram and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. These groups have been trying to gain a foothold in the region for years, and the coup could give them the opportunity they need. The instability could also have a regional impact, as many countries in West Africa are fragile democracies. If these democracies fall, it could pave the way for more extremist groups to take control.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

The Prosecutor's Office requests life imprisonment for four defendants for the 2016 attack in Gran Bassam, in Ivory Coast

The Prosecutor’s Office requests life imprisonment for four defendants for the 2016 attack in Gran Bassam, in Ivory Coast

The Ivory Coast Prosecutor’s Office has demanded life imprisonment against the four defendants for the attack carried out in March 2016 in the coastal city of Grand Bassam, which left nearly 20 dead and whose authorship was claimed by Al Qaeda in the Maghreb Islamic (AQIM).

The prosecutor Richard Adou has demanded during the seventh hearing of the trial an “exemplary and dissuasive sentence” to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Mali: Massacre by army, foreign soldiers

Mali: Massacre by army, foreign soldiers

The killings occurred amid a dramatic spike in unlawful killings of civilians and suspects since late 2021 by armed Islamist groups linked to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and by Malian government security forces. Armed Islamists have also killed scores of security force personnel since the beginning of 2022. Human Rights Watch is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

He had been a jihadi, Haidara argued, in the original and best sense of the word: one who struggles against evil ideas, desire, and anger in himself and subjugates them to reason and obedience to Gods' commands.

Joshua Hammer (The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu)

#language#cultural heritage#joshua hammer#librarian#the badass librarians of timbuktu#abdel kader haidara#journalism#north africa#saving islamic literature#library#al qaeda in the islamic maghreb#phenomenal story#in the original and best sense of the word#struggle against evil ideas#struggle against desire#struggle against anger in oneself

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

(...) Another potential risk for the protest movement is the difficulty of remaining unified in a power vacuum. There have been signs of disagreement within the movement over a proper transition road map. When an umbrella group of activists calling themselves the National Coordination for Change issued a statement in late March titled “Platform of Change,” it was disavowed by several signatories and rejected by some protesters, who were suspicious of signatories with alleged Islamist affiliations.

The movement also lacks an obvious leader. Lakhdar Brahimi, the Algerian diplomat who served as the United Nations mediator in Syria between 2012 and 2014, was put forthby Bouteflika to lead a national conference, but he is regarded by many as part of the presidential clique. The human rights lawyer and activist Mustapha Bouchachi is a prominent figure who has credibility with the protest movement, but he wants the new leadership to come from the country’s youth. The leaderless quality of the movement does not necessarily constitute a disadvantage; Tunisia’s 2011 revolution was described in the same way. But the fracturing of the traditional leadership, reflected in defections by business leaders, the president’s party, and other once-loyal groups such as the country’s largest labor union, as well as unrest among opposition parties, makes the country vulnerable to jockeying and power-grabbing, perhaps by the military.

Another risk, albeit a smaller one, is outside interference. Russia has been gradually reasserting influence in North Africa and has specifically sought to strengthen its economic ties with Algeria, including cooperation in the energy sector and the arms trade. Normally this would imply an interest in maintaining the status quo under Bouteflika and the army. Russia has reacted cautiously to developments in Algeria, calling for noninterference by other countries while also linking the opposition to Islamist movements. In March, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said Russia was concerned by the protests in Algeria and what he called attempts to destabilize the country. In a meeting with then-newly appointed Algerian Deputy Prime Minister Ramtane Lamamra, Lavrov had endorsed the Bouteflika government’s proposal to delay new elections. However, Lamamra is reportedly among the ministers fired on Monday. As power brokers in Algeria continue to shift and more clarity emerges on a possible transition, it’s worth keeping an eye on Russia’s reaction.

Meanwhile, extremist groups, including al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Islamic State-affiliated groups, continue to operate near Algeria’s borders. Although Algeria has increased defense spending in recent years and engaged in numerous military activities to combat this threat, the uncertainty facing the armed forces’ role in the country’s leadership could embolden extremist groups

1 note

·

View note

Text

French forces kill al-Qaeda’s Algeria leader

French forces kill al-Qaeda’s Algeria leader

[ad_1]

France said its forces have killed the leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, in a blow to the group behind a string of deadly attacks across the troubled Sahel region.

Abdelmalek Droukdel was killed on Thursday in northern Mali near the Algerian border, where the group has bases from which it has carried out attacks and abductions of Westerners in the sub-Saharan Sahel zone, Defence…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

French forces kill al-Qaeda’s Algeria leader

French forces kill al-Qaeda’s Algeria leader

[ad_1]

France said its forces have killed the leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, in a blow to the group behind a string of deadly attacks across the troubled Sahel region.

Abdelmalek Droukdel was killed on Thursday in northern Mali near the Algerian border, where the group has bases from which it has carried out attacks and abductions of Westerners in the sub-Saharan Sahel zone, Defence…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

French forces kill leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb – Times of India This undated handout file photo taken on July 26, 2010 apparently shows Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)...Read More…

#Abdelmalek Droukdel#abdelmalek droukdel al-qaeda#al-qaeda islamic maghreb#droukdel killed#islamic maghreb droukdel

0 notes

Photo

French forces kill leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb – Times of India This undated handout file photo taken on July 26, 2010 apparently shows Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)...Read More…

#Abdelmalek Droukdel#abdelmalek droukdel al-qaeda#al-qaeda islamic maghreb#droukdel killed#islamic maghreb droukdel

0 notes

Text

The French divorce from Mali is increasingly becoming the rule rather than the exception. Increasingly, France’s more-than-a-century-long diplomatic dominance in Africa is ending, and with it, France’s pretension of being a major player on the world stage.

Consider the Central African Republic: One year ago, rebels in the resource-rich, former French colony threatened to sack the capital Bangui. The United Nations, which has a robust peacekeeping force in the country, stood aside, as did France. Rwanda, with one-fifth the population of France and an army less than one-tenth the size of France’s, ultimately came to the rescue and stopped the rebel advance, pushing the Islamist rebels back into the hinterlands. From the locals’ perspective, French inaction compounded a betrayal marked by late President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s support for local dictatorship in exchange for a supply of Central African diamonds into French coffers. Although a generation of French policymakers have believed they could loot and run roughshod over the Central Africans, they have learned that Central Africans have long memories.

Then there is Rwanda itself. While Rwanda was originally a Belgian colonial possession, France treated it as its own following the country’s 1962 independence. French policy, however, was twisted. Declassified French archival documents and an assessment of newly-available sources now show beyond any reasonable doubt direct French complicity in the 1994 anti-Tutsi genocide. France’s motives? Distrust of Rwandans seeking greater ties to the Anglophone world as well as President Juvénal Habyarimana’s willingness (under whom Hutu militants planned the anti-Tutsi Genocide) to subordinate Rwandan interests and human rights to French requests. While Hollywood successfully depicted some of the horror of the 1994 genocide, the producers omitted French advisors training and even manning checkpoints with Hutu génocidaires. It is now clear there likely would have been no genocide in Rwanda had it not been for the cynicism of French president François Mitterrand. [...]

France’s unwillingness to recognize regional competition has also taken its toll. Djibouti, for example, was once France’s strategic backstop. Until a decade ago, Djibouti was home to the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion. It subsequently moved to the United Arab Emirates and then back to France. Meanwhile, China has become the dominant influence in the former French colony. Nor is China alone. Turkey is using anti-French, anti-colonialist rhetoric to cultivate former French colonies across Africa. In the most infamous example, Ahmet Kavas, the Turkish ambassador to Chad, lauded Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and accused French troops fighting them of being the real terrorists. [...]

While the United States does not have a colonial legacy in Africa [citation needed], it does have a history of supporting Cold War and Global War on Terror-era human rights abuses that Washington may have forgotten but locals in various countries have not. The second is the price of complacency. France should never have allowed China to out-compete it in Djibouti, nor should it have allowed Turkey to cultivate more influence in many Francophone countries than France itself.

shockingly coherent article from AEI until the last half (21 Feb 22)

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jihadist Takeover in West Africa

Jihadist Takeover in West Africa

When the government fails, who will step in to protect their citizens from the growing jihadist insurgencies?

This story was originally published in the February issue of ICC’s Persecution magazine.

02/10/2021 Washington D.C. (International Christian Concern) – Food, water, land shortages, religion, and extreme poverty are increasing the tensions between once peaceful sectors of societies in West Africa. Eleven of the poorest countries in the world are in West Africa: Benin (25), Guinea (24), Mali (22), Chad (20), Burkina Faso (15), Togo (14), Guinea Bissau (13), Gambia (10), Sierra Leone (9), Liberia (6), and Niger (4). No other area in the world has this high of a percentage of poverty except East Africa.

Complicating these factors and the strain they place on society is the region’s extreme diversity of tribes and languages. Nigeria alone has 250 different ethnic tribes and more than 400 different languages.

All of these factors combined have led to significant issues in many West African nations. These problems have contributed to the rapid growth of violent Islamic extremist groups in the region. These groups include Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Boko Haram, Ansar al-Sharia, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, Ansar ul-Islam, Ansaru, and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. These groups all currently operate in one or more West African countries.

All of these factors are driving several of the governments in the region towards failed state status. Mali, the center of most of the jihadist groups, lost control over the country’s northern region in 2012. Since then, the government has been unable to regain control and ceded the area to radical Islam as a training and recruitment ground. Given this safe home base, the jihadists have spread violence and terror throughout Mali, Niger, and northern Burkina Faso. This lack of control also led to a successful military coup in September of 2020.

Once a peaceful nation, Burkina Faso has become one of the fastest-growing global humanitarian disasters due to the spread of jihadism from Mali. Beginning in early 2018, jihadist groups started attacking towns in northern Burkina Faso. The government has been unable to stop these attacks, resulting in thousands of deaths and the displacement of nearly one million people.

In response to the growing crisis, Burkina Faso’s government enacted a self-defense bill called the “Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland Act.” This bill allows civilians from around the country to receive two weeks of training, weapons, and communications equipment. They then set up militias to defend their hometowns. Despite the good intentions of this act, it has already cost many innocent lives. Several of these militias have used their new access to weapons and training to attack other villages and towns.

With all the countries in the region lurching toward failed state status, Christians will face an increasingly difficult time. This is especially true as jihadist groups continually gain control over land in these already weak countries. These groups have allegiances to large Islamist terror organizations that seek to destroy Christianity altogether. If these governments fail, these nations will become a persecution hotbed for Christians for years to come.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

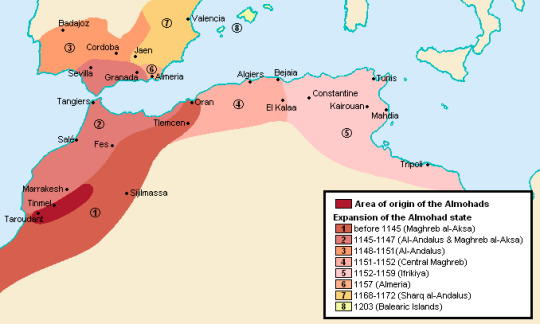

What Made the Almohad Caliphate So Bad?

Why the North African caliphate was the medieval equivalent to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

A common misconception about the Crusades, and particularly of the Reconquista, is that all Islamic states were essentially the same and united under the same banner when in reality, they had their own peculiar differences and were just as divided as the Christians were. Nothing exemplifies this better than the Almohad Caliphate, a 12th century Berber empire that emerged as a rebellious movement in the rapidly decaying Almoravid Empire and rose high enough in under a century to threaten Christendom before being beaten by the Crusaders.

“But Gaius”, I hear some of you saying: “ISIL is already an medieval minded organization. How they could be any different than the ones who lived in medieval times?”. Ah, my friends, there is more to ISIL than mere brutality and cruelty that conventional views tend to underestimate. One of the things that distinguished ISIL were that wanted to “purify Islam” by killing anyone they perceived as “apostates” or “infidels”. That is where the Almohads or al-Muwaḥḥidūn in Arabic (meaning “monotheists” or “unifiers”) come in.

Let’s start with their founder Ibn Tumart, a fiery Berber mullah notorious for being ultra-conservative and opposing art, songs, mixing of sexes in public and the selling of pork and alcohol, which were a common sight in the Mahgreb at the time, and blamed this on the laxness of the Maliki authority. While the Maliki school of thought is one of the most rigid ones in Sunni Islam, Tumart’s problem was that they tended to rely more on jurist consensus rather than following the Sunnah and the hadith to it’s letter.

His entire life reads like a comedic sketch: his fiery preachings lead to him getting expelled by the local authority until he moves to the next town and the exact same thing happens. It’s said this even happened in Mecca when he performed the hajj being thrown out because of his screeching. On the way back, he sailed on a ship and began throwing out boxes of wine and lecturing the sailors to pray at the correct time, leading them to be fed up and throwing him overboard (they fished him back later).

When Ibn Tumart made his way back to the Maghreb, he stopped by the Almoravid capital in Marrakesh and assaulted an emir’s sister for going out unveiled. He was brought before the local authorities and defended himself saying that he was merely a voice of reform and lectured the local emir and his jurists like he has been doing from town to town. When countered that at least on points of doctrine, there was little difference between them, Ibn Tumart brought out more emphasis on his own peculiar doctrines. After a lengthy examination, the Almoravid jurists of Marrakesh concluded Ibn Tumart, however learned, was blasphemous and dangerous, insinuating he was probably a agitator, and recommended he should be executed or imprisoned. The Almoravid emir, however, decided to merely expel him from the city, after a flogging of fourteen lashes.

That was an extremely poor decision, because Tumart proceeded to retreat to a cave in Igiliz, which was an conscious effort to emulate Muhammad when he entered the cave of Hira, where he adopted an ascetic life. That is when he began to attract followers gaining the fame of an holy man and miracle worker. In 1121, Ibn Tumart lamented his failure to persuade the Almoravids to reform by argument and after a particularly moving sermon, he suddenly “revealed” himself as the true Mahdi, the redeemer of Islam expected to return towards the end times. This was effectively a declaration of war on the Almoravid state - for to reject or resist the Mahdi's interpretations was equivalent to resisting God, and thus punishable with death as apostasy.

Though they began armed rebellion in the very next year, they didn’t exactly manage to have a successful track record against the Almoravids despite their weakened state. In fact, the Almohads were nearly annihilated during the Battle of al-Buhayra where several top generals were killed and Tumart himself died not too long afterwards. The death of their spiritual leader should have marked the end of their movement, but it was his successor Abd al-Mu’min who picked up the slack and proved to be far more competent in warring. He managed to conquer Marrakesh, overthrow the Almoravids and formally establishing the Almohad state which extended over Northern Africa as far Mamluk-held Egypt and managed to lead a Islamic resurgence into Iberia (or Al-Andalus as it was known by Muslims) retaking some territories lost to the Christian states in the north.

One of the things that distinguished the Almohads is that they rejected the doctrine of dhimmitude given to Christians and Jews living under their domain, allowing them to practice their religion on condition of submission to Muslim rule and payment of jizya. Sounds good right? No. The Almohads instead gave a choice to their non-Muslim subjects: convert to Islam or die. Except even those who converted were still forced to wear identifying clothing as they were not regarded as genuine Muslims. So imagine this scenario, dhimmitude is already a humiliating status, but now being forced to accept a religion they don’t want while having the same status as before is even more unbearable. Needless to say, this led to the mass martyrdom or exodus of many Christians and Jews.

Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra, who himself fled the Almohad persecutions, composed an elegy mourning the destruction of many Jewish communities throughout Spain and the Maghreb under the Almohads. Among the notable Christian victims are the Franciscan friars John of Perugia and Peter of Sassoferrato, Saint Daniel and his companions Agnello, Samuel, Donulus, Leo, Ugolino and Nicholas, and the Mercedarian saint and priest Serapion of Algiers was persecuted when trying to free Christian captives. Non-Muslims were not the only victims of Almohad’s fanaticism: the famous Islamic philosopher Averroes who is held in high regard by Westerners today was accused of blasphemy for among many things, criticizing Muhammad’s treatment of women, and as such was exiled. It’s also perfectly plausible that many of the things deemed acceptable by the Almoravids (women uncovered, music, art, etc) were forbidden by the Almohads.

The darkest moment for Christendom came with the Battle of Alarcos, when an Almohad host led by Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur decisively defeated the Kingdom of Castille and the knightly Orders of Santiago and Evora, killing over 30,000 into battle and leaving several castles deserted and many areas open to Islamic raidings. The Almohads were threatening to push north as far as possible and threatened to "march all the way to Rome and sweep the Basilica of Saint Peter with the Sword of Muhammad". This alarmed Pope Innocent III who called the European knights to crusade and served as basis for this song as by bard Gaudavan as rallying cry to help the Iberian Christians.

youtube

This ultimately culminated in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa where King Alfonso VIII of Castille - the same one beaten in Alarcos - led the Christian host of 14,000 men (Portuguese, Castillans, Templars, Germans, French and others) against the Almohad caliph Muhammad al-Nasir, who had more than twice with 30,000 men in his command. Despite the impossible odds, the Christians managed to win (check this video for the details).

youtube

This defeat was a decisive point in the Reconquista, as the Almohad power was broken and they would never recover, with their territories breaking up into petty kingdoms (or taifas). It also marked the downfall of Islamic rule, since from now on Christians - more specifically Spaniards - would retake almost all their lands. Just before their end, the Almohads would ditch their doctrines in favor of more traditional ones and repudiate Ibn Tumart as the Mahdi, but their end came when their final pretender Idris al-Wathiq was killed by a slave and his possessions were later taken by the Marinid Sultanate who would try to take Iberia again, but they were soundly beaten in the Battle of Rio Salgado by the now much stronger Portuguese and Spaniards (though them taking the sultan’s entire harem and putting them to the sword may have done the trick).

So now you might be asking me now: why is this all relevant to the Islamic State? You see, their founder Abu Musaib al-Zarqawi was sorta kinda like Ibn Tumart, except he Zarqawi was a petty thief and a pimp rather than a scholar. His views were radical even by Salafi jihadists’ standards, urging the death of Shia Muslims more than the Christians and Jews. Osama bin Laden himself, at least thought as such and never particularly liked Zarqawi whether for personal reasons (Bin Laden’s own mother being Shia herself) or pragmatic ones (Zarqawi’s actions could divide Muslims more than unite them). And just like Ibn Tumart, he never lived to see the Islamic State (or Al-Qaeda in Iraq as it was known in his lifetime) become the nightmarish menace to everyone.

There are of course many obvious differences: ISIL apparently made a point to adhere to the dhimmi contract as far as the Assyrian Christians were concerned while the Almohads ditched it altogether. Or that Zarqawi never claimed to be the Mahdi, nor did his successor Abu-Bakr al-Baghadadi to legitimize themselves. Though there are many important parallels: ISIL was in essence an apocalyptic group just like the Almohads followed the Mahdi, whose presence marked the end times. They viewed the events in Syria and Iraq as the fulfillment of the prophecies about the end times and heavily derived their narrative from it. Their initial propaganda magazine Dabiq was named after an town where a hadith claims a great battle will occur between the Muslims and the Romans where the apocalypse will take place and Muslims will emerge victorious. The “Romans” in this case represent the West, which is why they carried out incessant attacks to provoke Americans and Europeans to fulfill this prophecy.

The Almohads emerged during a period here they perceived Islam had decayed and needed reform or rejuvenation which is an rhetoric used by ISIL, but not necessarily exclusive to them. It’s somewhat reasonable to understand the Almohad Caliphate is not as well-known or prominent as other empires like the Umayyads or the Ottomans, since they are more important to local history, but I think we’d benefit more if we paid attention more.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu

War comes and goes. Pedagogy brightens and dims. Economic prosperity rises and wanes. Racism, for whatever the reason, is burned into the skin. . .

As a twenty-something, Haidara traveled up and down the Niger river, meeting and speaking with thousands of villagers to negotiate from their hands ancient manuscripts that had been guarded by their families for hundreds of years. Ever the diplomat, he sought to reassure them of his capacity to value, restore, and preserve these texts.

On many occasions, the man traversed the desert, either by camel or on foot, languishing beneath the bold and blistering sun. His travel from his home in Mali to Burkina Faso, for example, included 12 hours travel on camel, plus another 19 hours on foot.

Remarkably, villagers and heads of family buried their manuscripts in the sand, stored them in tin chests, or tossed them into rice bags and hid the bags in distant caves -- kept, always, from the hands of foreigners and colonists whom, intriguingly if not ironically, would have begrudged if not perverted the discovery of such knowledge among the "savages" of Africa. THE BAD-ASS LIBRARIANS OF TIMBUKTU is abundantly clear in that the new-old discovery of these manuscripts, and the enlightenment they beheld, is an overturning of centuries-old racism that has permeated the lives of the peoples of Africa. War comes and goes. Pedagogy brightens and dims. Economic prosperity rises and wanes. Racism, for whatever the reason, is burned into the skin. . .

Hammer's book isn't simply a discussion of ancient texts; it is also a chronicle of the more contemporary threats these texts, and the free-exchange of knowledge in general, face in today's world. Religious radicals, kidnappers and gangsters, fundamentalists, disenfranchised militiamen, and indigenous rebel groups all populate North Africa to varying degrees. And to this end, Hammer provides exquisite and thorough description of how three ideological masters of Islamic austerity twist centuries of goodwill into their very own war against the perceived inadequacy of human practice in the land of their god. Abdelhamid Abou Zeid (cunning and ruthless), Mokhtar Belmokhtar (determined and hard-bitten), and Iyad Ag Gahli (skillfully diplomatic) converge upon Mali's isolated north with differing prospects in mind but eventually settle on the usurpation (and conversion) of the nation into an isolated state/caliphate under Seventh Century law.

This book constitutes necessary education for those who claim intellectual prescience on matters of geopolitical consequence.

The intersection of these three men and their group, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and the peaceful efforts of Haidara to collect and preserve the history of African intellectuals, is at once incidental as well as inevitable.

But as readers soon learn, there is always a brash divergence of cultural obligation wherever AQIM manifests its rifles and all-terrain vehicles. The group's seizure of Timbuktu and its many outlying village areas eventually forces Haidara and his cohorts into action to preserve North Africa's knowledge and history.

How does one traffic 377,000 manuscripts out from under the nose of the region's most determined militants? Per Abdel Kader Haidara, very carefully. As such, THE BAD-ASS LIBRARIANS OF TIMBUKTU contains beautiful and treacherous passages of spy-novel-like intrigue in which Haidara's men smuggle ancient texts under the cover of darkness via canoe, camel, taxi cab, and more. The lengths through which these librarians and tenants of literature go to protect these texts may feel absurd, but the reality sinks in rather quickly: avoiding military checkpoints is the key to success, and risking escape from the calculated raids of demanding security figures is a life-or-death decision.

This book constitutes necessary education for those who claim intellectual prescience on matters of geopolitical consequence. Some readers may feel lost by the fact-finding expeditions upon which the author constantly embarks, but rest assured, one cannot live for discovery without first pledging allegiance to the unknown.

Hammer's descriptions of the reputed murderers lend astonishing perspective to otherwise typically faceless oppressors. Abou Zeid was short and bow-legged, and had bad posture, very dark skin, "a hawk-like face," and a badly fraying beard; he was extraordinarily violent, yet never raised his voice, and he always commanded his followers with a resilient, even temper. Belmokhtar was a hardened soldier who lost an eye in an explosives-training accident, thus sporting a fantastic scar, while "his mouth twisted from time to time into a ghost of a cold, almost wry smile" (p. 103).

THE BAD-ASS LIBRARIANS OF TIMBUKTU a deft negotiation of all that is grand, all that could be lost, and all that remains unsolved, regarding humanity’s trouble with humanity.

Ghali is an interesting case; having survived poverty, exile, and the brutality of conflict at every stage of life, the man turned away from a world of pastoral music, politics, and a reverence of the religiously moderate and toward the more deliberately fervent (and violent). Ghali was a large and imposing man who near-always ran from his problems.

Hammer's descriptions of the African landscapes are raw and absolute. Highlights include his sighting the quartz-and-sandstone outcropping, Fatimah's Hand, as "three fingerlike pillars almost the color of human flesh, tilting slightly backward and extending two thousand feet from the desert floor toward the sky" (p. 43). Pink Dune, an 80-foot mountain of sand on the bank of the Niger, "it's face intricately scalloped by the constant wind" (p. 153), and whose exquisite view of the sunset permits even the most horrible men on the continent the boyish pleasure of sleeping close to the stars. On one side of the dune lie dozens of islets; on the other side, the near-infinite Sahara, "a flat ocher sea" blemished with tufts of yellowing grass. And Hammer's description of the Amettetaï Valley, the eventual last stand of Abou Zeid and his faction of AQIM, is brilliant: "low gray and black granite hills, eroded to rubble and pocked with caves," accent a dangerous and ambush-prone stretch of 25 miles that includes boulders, caves, crawl spaces, and "sandy ancient riverbeds" that flood during the two or three annual rainstorms (pp. 219–220).

Quality journalism and a skilled attempt to document the preservation of reason against modern-day ideological primitiveness (and their barbarous underpinnings) make THE BAD-ASS LIBRARIANS OF TIMBUKTU a deft negotiation of all that is grand, all that could be lost, and all that remains unsolved, regarding humanity's trouble with humanity.

Book Reviews || ahb writes on Good Reads

#the badass librarians of timbuktu#book review#joshua hammer#writeblr#goodreads#5 of 5 stars#nonfiction#literary criticism#abdel kader haidara#africa#african literature#african history#al qaeda in the islamic maghreb#disenfranchised militiamen#smuggle ancient texts under the cover of darkness#fatimahs hand#hardened soldier#tenants of literature#subsaharan africa#manuscript preservation#abdelhamid abou zeid#mokhtar belmokhtar#iyad ag gahli

0 notes

Text

#5yrsago Why terrorist bosses are micro-managing dicks

Jacob N. Shapiro, author of The Terrorist's Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations , sets out his thesis about the micromanagement style of terrorist leaders in a fascinating piece in Foreign Affairs. It comes down to this: people willing to join terrorist groups are, by definition, undisciplined, passionate, and unbalanced, so you have to watch them closely and coordinate their campaigns. From the IRA to al Qaeda, successful terrorist leaders end up keeping fine-grained records of who's getting paid, what they're planning, and how they're spending. This means that in many cases, the capture of terrorist leaders leads to the unraveling of their organizations, but the alternative is apparently even worse -- a chaotic series of overlapping, self-defeating attacks and out-of-control spending.

Recall that Moktar Belmoktar was hounded out of the Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in part over his sloppy expense reporting, and that he went on to found the group that took more than 800 hostages in a gas plant in Algeria. This kind of budget-niggling is apparently common: Ayman al-Zawahiri, leader of al Qaeda since 2011, was reportedly furious that Yemeni affiliates had bought a new fax machine, because the old one worked just fine.

https://boingboing.net/2013/08/15/why-terrorist-bosses-are-micro.html

7 notes

·

View notes