#Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie

Photo

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie (Peter Kuran, 1995).

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Oppenheimer, starring Cillian Murphy, as J. Robert Oppenheimer, has been getting a lot of buzz this summer for its subject (The Manhattan Project) and its close premiere date with The Barbie movie. Long before Oppenheimer, there have been many movies created about The Manhattan Project, J. Robert Oppenheimer, or the terrors of the atomic bomb.

We searched Reddit to discover what movies and documentaries Redditors recommend to watch before Oppenheimer. From Fat Man and Little Boy to Trinity and Beyond - The Atomic Bomb Movie, there are many different options for documentary lovers, classic film enthusiasts, and even sci-fi fans.

10 'Fat Man and Little Boy' (1989)

Fat Man and Little Boy, directed by Roland Joffé, is a dramatic interpretation of the events and people surrounding The Manhattan Project. General Groves enlists the help of a team of scientists, including Oppenheimer, to develop atomic bombs. Politics and technical issues delay and cause the team to clash with each other as they get closer to creating Fat Man, a heavy plutonium bomb, and Little Boy, a smaller plutonium bomb. The movie brings together an all-star cast, including Paul Newman (General Leslie R. Groves), Dwight Schultz (J. Robert Oppenheimer), John Cusack (Michael Merriman), Laura Dern (Kathleen Robinson), and Bonnie Bedelia (Kitty Oppenheimer).

Critics weren't too excited about Fat Man and Little Boy when it came out, but Reddit doesn't seem to mind the dramatization of The Manhattan Project. Reddit user Beatle7 commented that "Fat Man and Little Boy does cover it [The Manhattan Project], and it's OK..." Another user Spies87 also mentions Fat Man and Little Boy as a recommendation. This movie will provide Oppenheimer moviegoers with a base for what direction a fictionalized movie can take, but it won't provide a good basis for facts about The Manhattan Project.

9 'Infinity' (1996)

Infinity is kind of indirectly related to The Manhattan Project. Matthew Broderick stars as Richard Feynman, a physician known for his work on The Manhattan Project. Infinity doesn't focus too much on the science or what goes on with atomic bombs. Instead, the film's plot dives into the romantic chemistry between Richard and Arline, his love interest who is played by Patricia Arquette.

While Oppenheimer isn't a romance, movie fans should consider giving Infinity a watch before they head to the theater to see Christopher Nolan's thriller unfold. Richard Feynman is depicted by Jack Quaid in Oppenheimer. Infinity gives a peak into Richard Feynman's life outside the lab and how he met his future wife, Arline. "There's a great movie of Matthew Broderick's (produced and acted in) called Infinity in which he's playing the physicist Richard Feynman, who was instrumental in the Manhattan Project. He was newly married when he worked there, and it's a big part of the movie," wrote Reddit user Beatle7.

8 'The Manhattan Project' (1986)

Despite its name, The Manhattan Project, directed by Marshall Brickman, isn't actually about the atomic bomb experiment in New Mexico. However, this film does involve an atomic bomb. Paul, a smart young teenager played by Christopher Collet, decides to create an atomic bomb for his school science project after he is inspired by a visit to scientist John Mathewson's lab. Paul must steal radioactive materials to build his project and to help his aspiring journalist girlfriend, Jenny, who wants to expose the company that John works for.

The Manhattan Project and Oppenheimer are very different movies, but they both are thrillers. A viewing of The Manhattan Project will help Oppenheimer moviegoers in the right state of mind to watch the fast-paced action and intrigue. One of the main reasons to watch The Manhattan Project is Lithgow's portrayal of scientist John Mathewson. Reddit user castlebravomedia commented that the film is alright, but John Lithgow is always fun to watch.

7 'The Beginning of The End' (1957)

The Beginning of The End, directed by Bert I. Gordon, is another sci-fi movie that doesn't involve anything about The Manhattan Project, but it deals atomic horror. The film stars Peggy Castle as Audrey Ames, a journalist who must work with Dr. Ed Wainwright, a scientist, to stop giant grasshoppers (whose size happened due to consuming radioactive tomatoes) from destroying Chicago.

Redditor mike_sean recommended watching The Beginning of The End to a Reddit user who asked for suggestions on movies that depict The Manhattan Project. Giant monster movies, also known as kaiju films, are a cultural aftereffect of people's fear of nuclear war and atomic bombs. Like other giant monster movies, The Beginning of The End depicts this fear in the metaphor of giant grasshoppers. The film was made ten years after The Manhattan Project ended, and shows how it had lasting impact on the American subconscious.

6 'Day One' (1989)

Day One, directed by Joseph Sargent, is an Emmy-award winning TV movie about the creation of the atomic bomb. This docudrama portrays the dynamics (good and bad) between General Groves (Brian Dennehy) and The Manhattan Project team, including J. Robert Oppenheimer (David Strathairn) and Leo Szilard (Michael Tucker).

Day One fans say that this is a solid adaptation of the novel, One Day by Peter Wyden. Many fans also commend David Strathairn's performance as Oppenheimer and Brian Dennehy's portrayal of General Groves. Reddit user mike_sean suggested this movie to their fellow Redditor who was looking for recommendations for movies related to The Manhattan Project.

5 'Countdown to Zero' (2010)

Countdown to Zero, is a documentary directed by Lucy Walker, about the atomic bomb and nuclear arms race. It's an intense analysis at how the possibility of nuclear weapons being unleashed has risen due to factors such as terrorism and lack of legislation.

This documentary doesn't dive into The Manhattan Project. However, there are moments of in the film which show Oppenheimer. Reddit user Summerbrau recommended Countdown to Zero to a Redditor who was looking for documentaries about The Manhattan Project. They commented: "Not specifically the Manhattan Project but has a lot of Oppenheimer footage from the day. Countdown to Zero by Lucy Walker."

4 'The Day After Trinity' (1981)

The Day After Trinity is a documentary directed by Jon H. Else. The documentary's name refers to a famous quote said by Oppenheimer. The Day After Trinity examines the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer and his work associated with The Manhattan Project. While the film does include information about the early days of The Manhattan Project, it also extensively covers the aftermath of the Trinity event.

What is the most interesting thing about The Day After Trinity is that it just doesn't talk about J. Robert Oppenheimer. The film features several interviews with people who worked on The Manhattan Project. As a bonus, the documentary also has declassified government footage. One Reddit user wrote: "The Day after Trinity" - this one is great. It has a lot of interviews."

3 'The Atomic Cafe' (1982)

The Atomic Cafe, directed by Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty, is a documentary-like film of archival footage from the 1930s and 1940s. The editing together of U.S. propaganda about atomic bombs creates an oftentimes funny, but mostly terrifying depiction of atomic bombs.

From the obscure music to its tongue-in-cheek humor, critics and fans absolutely love this documentary. The Atomic Cafe sends its viewers a message about atomic bombs with only footage and no narration. This makes it a prime candidate for being a classic documentary. Reddit user mi-16evil calls The Atomic Cafe a "classic about nuclear paranoia."

2 'The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer' (2008)

The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer, directed by David Grubin and narrated by Campbell Scott, is a made of TV documentary which follows the life of Oppenheimer from his childhood to his time as a scientist on The Manhattan Project. This film is part of The American Experience series from PBS and WGBH Boston.

Reddit user TepidShark recommended The Trails of J. Robert Oppenheimer to a Redditor who wanted to know any movies or TV shows they should look into before they see Oppenheimer. This documentary takes a biographical look into Oppenheimer's life with archival footage, but it also includes reenactments of the Oppenheimer security hearing. In their comment, Redditor TepidShark mentions that the documentary "features recreations of a trial Oppenheimer was involved in, that feature David Strathairn as Oppenheimer."

1 'Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie' (1995)

Trinity and Beyond - The Atomic Bomb Movie, directed by Peter Kuran, is a documentary about the history of nuclear weapons. The documentary, narrated by William Shatner, uses restored archival footage to explore how nuclear technology was developed. The film includes clips of weapons being tested, including the Trinity site test to the test of the Nike Hercules defense missile.

Fans of Trinity and Beyond praise it for being informative and haunting. The film is also popular for its score by the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Redditor user mi-16evil suggests that people interested in seeing Oppenheimer should watch this movie because it is a "pretty good straight up documentary about the nuclear arms race."'

#Oppenheimer#Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie#The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer#The Atomic Cafe#The Day After Trinity#Countdown to Zero#Infinity#Fat Man and Little Boy#The Manhattan Project#Jack Quaid#Richard Feynman#The Beginning of The End#Day One#Matthew Broderick#Cillian Murphy#Paul Newman#John Cusack#Laura Dern#William Shatner

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

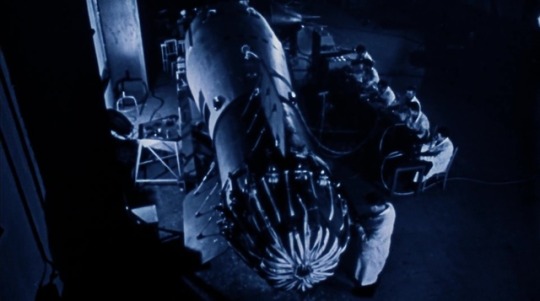

The End of Evangelion, dir. Hideaki Anno, 1997 || Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie, dir. Peter Kuran, 1995

#the end of evangelion#eoe#hideaki anno#trinity and beyond the atomic bomb movie#peter kuran#castle bravo#third impact#rei ayanami#terrifying

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amid a desert landscape a visionary unveils an invention that will forever change the world as we know it.

That’s the climactic scene of the Christopher Nolan biopic Oppenheimer, about the eponymous J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb.” It’s also the opening scene of the Barbie movie, directed and co-written by indie auteur Greta Gerwig, which opened on the same day as Oppenheimer.

Despite the two films’ radically different subject matter and tone—one a dramatic examination of man’s hubris and the threat of nuclear apocalypse and the other a neon-drenched romp about Mattel’s iconic fashion doll—they have far more in common than just their release date. Both movies consider the complicated legacies of two American icons and how to grapple with and perhaps even atone for them.

In Oppenheimer, the desert scene depicts the Trinity test, the world’s first detonation of a nuclear bomb near Los Alamos, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. A brilliant but flawed theoretical physicist and the rest of his team work frantically to develop the weapon for the United States before the Nazis can beat them to the punch; they then gather on bleak, lunar-white sands near their secret laboratory to test the terrifying creation.

The countdown timer ticks to 00:00:00, the proverbial big red button is pushed, and a blast ignites the sky—a blinding white flash that quickly morphs into a towering inferno. Everything goes silent as Oppenheimer stares in awe from behind a makeshift protective barrier at what he has created.

Suddenly, he begins experiencing flashes of a different kind, premonitions of the human horror and suffering his weapon will wreak. Nolan is unambiguously signaling to the audience that this is a pivotal moment for the world, and for Oppenheimer personally, as what was once merely a theoretical idea has become monstrously real. The fallout, both literally and figuratively, will be out of Oppenheimer’s control.

Barbie’s critical desert scene comes not at the film’s climax but at its very beginning. The movie opens with a parody of the famous “The Dawn of Man” scene from Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1968 science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. As a red-orange sunrise breaks across a rocky desert landscape, a voiceover (from none other than Dame Helen Mirren) begins: “Since the beginning of time, since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls. But the dolls were always and forever baby dolls.” On screen, underscored by the ominous notes of Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” little girls sit amid dusty canyon walls playing with baby dolls.

“Until…” Mirren says. And then comes the reveal: The little girls look up to see a massive, monolith-sized Margot Robbie, dressed in the black and white-striped swimsuit of the very first Barbie doll. She lifts her sunglasses and winks. The little girls are stunned—and, like the apes in the classic sci-fi movie, they begin to angrily dash their baby dolls against the ground.

This is Barbie’s mythic origin story: Once upon a time, little girls could only play with baby dolls meant to socialize them into wanting to be good wives and, eventually, mothers. Then came Ruth Handler, who in 1959 decided to create a doll with an adult woman’s body, adult women’s fashions, and adult women’s careers so that little girls could dream of being more than just wives and mothers. And the rest is history. Thanks to such iterations as doctor Barbie, chef Barbie, scientist Barbie, professional violinist Barbie, and beyond, Barbie opened up young girls to a world of possibilities and, Mirren says, “All problems of feminism and equal rights [were] solved.”

Well, not so fast: Mirren adds one final, snarky beat: “At least,” she says, “that’s what the Barbies think.”

Thus Gerwig introduces the central tension that animates the movie: Handler set out to create a feminist toy to empower and inspire young girls. But we sitting in the audience in 2023 know that things worked out a little differently. In the intervening years, Barbie would come under fire from feminists and other critics for a whole host of sins: encouraging unrealistic and harmful beauty standards that contribute to negative body image issues, eating disorders, and depression among pre-adolescent girls; lacking diversity and perpetuating white supremacy, ableism, and heteronormativity; objectifying women; promoting consumerism and capitalism; and even contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

And here is the core parallel between Barbie and Oppenheimer: Two iconic American creators who ostensibly meant well but whose creations caused irreparable harm. And two iconic American directors (Nolan is British-American) who set out to tell their stories from a very modern perspective, humanizing them while also addressing their harmful legacies.

But while Nolan obviously had the much harder task—no matter how much harm you think Barbie has done to the psyches of young girls over the years, there’s simply no comparison to the human toll of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the environmental impact of decades of nuclear testing, or the cost of the nuclear arms race—oddly enough, it’s Gerwig who ends up taking her job of atonement far more seriously.

As its opening scene shows, the Barbie movie lets the audience know right from the start that it’s self-aware. It knows that Barbie is problematic. And it’s going to go there.

And it does—almost to the point of overkill. The basic plot of the movie is this: Barbie is living happily in Barbie Land, a perfect pink plastic world where she and her fellow Barbies run everything from the White House to the Supreme Court and have everything they could ever want, from dream houses to dream cars to dreamy boyfriends (Ken)—the last of which they treat as little more than accessories.

But suddenly, things start to go wrong in Barbie’s happy feminist utopia, and to fix it, she is forced to journey into the real world—our world—accompanied by Ken, who insists on going with her. When she does, she realizes that contrary to what she believed (as Mirren told us in the opening scene), the invention of Barbies didn’t solve gender inequality in the real world. In the real world, Barbie is confronted not only with the dominance of the patriarchy (she discovers, for instance, that Mattel’s CEO is a man, played by Will Ferrell), but also with the fact that young girls seem to hate her.

In a crucial early scene, Robbie’s Barbie encounters ultracool Gen-Z teen Sasha (played by Ariana Greenblatt), who delivers a scathing monologue about everything that’s wrong with Barbie, the doll and cultural symbol—basically a checklist of all the criticisms lobbed at Barbie over the years, from promoting unrealistic beauty standards to destroying the planet with rampant capitalism. Barbie is crestfallen.

Meanwhile, there’s a subplot involving Ken’s parallel discovery of patriarchy, and how awesome and different it seems to be from his subjugated life in Barbie Land. Ken proceeds to go full men’s rights, heading back to Barbie Land and seizing power. He transforms Barbie’s dream house into Ken’s Mojo Dojo Casa House, where Barbies serve men and “every night is boys’ night!”

Barbie enlists the help of Sasha and her mom (played by America Ferrera)—a Mattel employee who secretly dreams up ideas for new, more realistic Barbies such as anxiety Barbie—to unseat Ken and restore female power in Barbie Land. Along the way, Ferrera’s character delivers the film’s other major feminist monologue, about how hard it is being a woman in the real world.

The monologues are unsubtle, as are the repeated mentions of concepts like the patriarchy. In every scene and nearly every line, the movie hits the audience over the head with the pro-feminism message. Gerwig knows what her job is—to atone for Barbie’s sins (and, yes, help Mattel sell more dolls)—and she makes sure everyone knows that she has fully understood the assignment.

But it’s in the film’s quieter, more tender moments that Gerwig’s background as an indie filmmaker and her true talent shine through, and where she’s able to communicate the message in a subtler, but ultimately more impactful, way. The scene where Barbie in the real world sees an elderly woman for the first time (old people and wrinkles don’t exist in Barbie Land, obviously) and is stunned at how beautiful she is, wrinkles and all. Or the scenes where Barbie talks quietly with her deceased creator, an elderly Handler (played by Rhea Perlman), who explains that the name Barbie was an homage to Handler’s daughter, Barbara, who inspired her to make the doll.

The overall result is a movie that, even if a bit ham-fisted in its over-the-top messaging, doesn’t shy away from the uglier parts of Barbie’s legacy. It looks them right in the face, wrinkles and all.

I said above that the Trinity test scene is the climactic scene in Oppenheimer, but that’s not really the case. For a movie about the complicated life and legacy of the man credited with creating the world’s most destructive weapon, it should be the climax. You might imagine it would follow with a denouement of the inventor confronting the reality that his creation is used to kill tens of thousands of Japanese civilians and sparks an arms race that threatens to destroy all of humanity.

These scenes are in there, but they are given short shrift next to the other story Nolan wants to tell: that of how Oppenheimer, once considered an American hero, was mistreated by his country in the postwar years. As McCarthy-era fears of communist infiltration grip the country, Oppenheimer’s previous ties to the Communist Party (he never joined the party himself, but he had close family members and friends who were members, and he supported various left-wing causes) are mysteriously brought to the FBI’s attention despite already being well documented. His security clearance is revoked, and his career working with the U.S. government on nuclear issues ends.

It is this storyline—not the apocalyptic destruction of two Japanese cities—that is given the most pathos. Much of the movie’s three-hour run time—and nearly all of its third act—centers on what we are clearly meant to see as the great evil that was done to this man who did so much for his country. The real climax of the film is not the Trinity test, nor even the bombings of Japan (which are not even shown in the movie), but rather the moment we learn who betrayed Oppenheimer by handing over his security file to the FBI.

This is the shocking revelation that is meant to induce gasps in the audience, not the images of charred and irradiated bodies. In fact, those images aren’t even shown to us, the viewers. In the scene where Oppenheimer and his team are shown photos of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the camera stays tight on Oppenheimer’s face as he reacts to the images—a reaction that consists of him putting his head down to avoid seeing them.

It is an act of cowardice on Oppenheimer’s part, yes, but also on Nolan’s. Indeed, the only glimpses we get of the macabre effects of the atom bomb take place in Oppenheimer’s fevered imagination, and even then, they are brief flashes used for shock value: skin flapping off the beautiful face of an admiring female colleague; the charred, faceless husk of a child’s body Oppenheimer accidentally steps on; a male colleague vomiting from the effects of radiation. Of the Japanese victims, there is nothing. They remain theoretical, faceless.

Nolan has said that he chose not to depict the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not to sanitize them but because the film’s events are shown from Oppenheimer’s point of view. “We know so much more than he did at the time,” Nolan said at a screening of the movie in New York. “He learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio, the same as the rest of the world.”

But in reading the numerous interviews he’s given about the movie, it’s also clear that Nolan fundamentally sees Oppenheimer as a tragic hero—Nolan has repeatedly called Oppenheimer “the most important person who ever lived”—and Oppenheimer’s story as a distinctly American one. “I believe you see in the Oppenheimer story all that is great and all that is terrible about America’s uniquely modern power in the world,” he told the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “It’s a very, very American story.”

That Nolan’s film devotes so much runtime to Oppenheimer’s point of view and how he was tragically betrayed by his country is partly due to the fact that the film is not an original story but rather an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the great scientist, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. That book also places Oppenheimer being stripped of his security clearance at its center. But that didn’t mean Nolan had to do the same in his adaptation. That was a choice. And the end result is what military technology writer Kelsey Atherton aptly described as “a 3 hour long argument that the greatest victim of atomic weaponry was Oppenheimer’s clearance.”

At a time when Americans are struggling to reckon with their country’s past and how it has shaped the present—from fights over how (or even whether) to teach children about the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow; to debates, including in these very pages, over the role (or lack thereof) of NATO expansion in Russia’s decision to wage war on Ukraine; to retrospectives on the myriad failures of the U.S. war in Afghanistan; and beyond—the fact that the two biggest films in theaters right now are attempting to confront the legacies of two American icons, the nuclear bomb and Barbie, is understandable and perhaps even impressive.

But the impulse to look away from the ugliest parts of those legacies remains strong, and Oppenheimer never fully faces them.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

My 2 Favorite Movies of Summer 2023

I watched a bunch of movies from June to July of this year, and I've come to the conclusion that my two favorite movies this summer are Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse and Oppenheimer.

While Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One was enjoyable and Transformers: Rise of the Beasts was fun (especially as a Transformers fan), Across the Spider-Verse and Oppenheimer are two movies that have stuck with me since I've watched them.

So, this is not really a review per se but just an unfocused dumping of my thoughts about them.

SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE

I had been anticipating this movie since early this year, as did a lot of people. I was blown away by the animation and style that was shown by the trailers, so by the time it hit theaters I was hyped as hell. I initially wanted to see it with friends but their agendas didn't line up with when I wanted to so I ended up watching with my family much to my chagrin.

Anyway, I had such a blast watching the movie. I ended up watching it for a second time though I missed the intro sequence (embarrassing) but I still had a good time. Most of what I'm writing are much the same as other people so I'm going to be quick.

The animation was amazing (no pun intended), I love how the different universes are depicted in different art styles. I love the writing, how the characters and plot are written and the themes and it being kind of a commentary on your typical Spider-Man story. That ending sequence gave me chills, like, it was almost like the movie became a horror movie. It's clear that the movie was made with love, passion and care for art, animation and Spider-Man.

Overall, this movie was spectacular and it's likely that it'll be held as the new standard for animated movies in the future. That is until Beyond the Spider-Verse comes out and blows this movie out of the water like this movie did with Into.

It's such a shame this movie was produced under such abysmal conditions. Justice for the animation industry! It deserves so much better, man.

OPPENHEIMER

TW: Discussion of nuclear devastation

To be honest with you, I didn't much care about this movie before I watched it. I remember being ambivalent about it when the movie was first revealed. Later, out of the blue my dad suggested to my family that we go watch it and I joined mostly because I was like, "Eh, what the hell."

The movie was not what I expected.

For one thing, it didn't glorify the atomic bomb like I thought, even though it didn't show the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the impact it had on the people of Japan. And, forgive me if I wrote out of turn, I don't think it needed to. For Oppenheimer (the character), the devastation was far away but just like during the Trinity nuclear test, he could still feel its effects even from far away.

Anyway, enough with the tangent. Let's talk about the actual goddamn movie.

It's definitely a Christopher Nolan movie featuring a non-linear story structure and epic and grand scope and presentation, with an extensive cast of actors, who I think did great with their portrayals. I could tell that every part of this movie was carefully crafted, everything from the casting, cinematography, production design, and special effects and visual effects, etc. are all executed with astonishing results. They recreated the Trinity bomb test with PRACTICAL EFFECTS I think that's fucking crazy.

This movie was so good, the ending, for the first time in a long time, left me with an actual fear of a nuclear holocaust, like, good g-d. If you want to talk about the politics of this movie, I'll tell you that it's clearly an anti-war film.

Unfortunately, I didn't get to see Barbie so I didn't participate in the Barbenheimer craze.

Overall, Oppenheimer is an excellent film. I don't think I have much more to write.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thanks for indulging me during this trainwreck of a Tumblr post. I just wanted to talk about these two movies.

#across the spiderverse#spider man: across the spider verse#spider verse#oppenheimer#oppenheimer movie#review (kinda)#movies#film#please don't fight with me over the politics of oppenheimer#this post is kinda badly worded in places forgive me#thought dump

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've now seen Barbie twice and Oppenheimer once. They both left me with a lot of thoughts. It's also interesting how this cultural moment has got us comparing them due to releasing on the same day despite how different they are.

But not for the reasons we thought!!!

And I have my own thoughts!

I mean, yes, I knew going into Oppenheimer I was going to leave feeling heavy. I'm no expert on World War II history (I focused my history studies on the Cold War, and specifically Central/Eastern Europe), but we know the US bombed Japan, changing Japan forever. I've also watched the original Godzilla film in Japanese, Grave of the Fireflies, and plenty of other films focused on Japan's response to that traumatic and horrible experience. I can't shake all of that going into Oppenheimer.

I've seen some responses that the biopic goes too easy on Oppenheimer and the US, and while I never expected the film to have a specific anti-war bent (that would have been at odds with the person the film this is centering), it really effectively communicates the weight of the US possessing weapons of mass destruction. The pounding of the auditorium steps after the successful Trinity test, the shots of Oppenheimer imagining the audience dying as well as him stepping onto and breaking a charred body, the cacophony of cheers and terrified screams and stomping, and just...it was so, so much. I felt myself folding into myself, just so overwhelmed. It's such a good scene that carries through that emotional weight for the rest of the movie as Oppenheimer transitions into strongly advising against creating the hydrogen bomb in a race with the USSR. Not to mention all of the tension that underlies all US politics post-WWII in the era of McCarthyism, which still influences us today. Oppenheimer is not an easy film to watch.

But it's also strangely dreamy. Oppenheimer was a man who was wrapped more in ideas than in people themselves, and there are so many unreal, beautiful shots of particles, ripples on water, etc. There are also plenty of awesome (in the old sense of the word) shots of violence and impact from the atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer as a film is both complicated in how it portrays a complicated man, but it's also pretty straightforward in its morals and messaging, whereas Barbie hit me in ways I wasn't really expecting.

Barbie starts off incredibly dreamlike, and it sells the fantasy of Barbieland very well. The willingness to commit to the bit is one of the film's strengths in how it depicts that world (and then Kendom). But the movie, in my opinion, becomes less about Gender and more about our place in the world. Yeah, you can look at that through a gendered lens (both for the Barbies and for the Kens), but it's Margot Robbie's Barbie who decides to become a Creator, a Dreamer and not the Idea that others make. There's actually something very powerful about being an idea, but people will always be more complicated than ideas (maybe that's Oppenheimer the character's issue with women?). On her first foray into the Real World, Barbie sees that things are nowhere near as sunny as she expected. Women are of course not treated well, but even beyond that, from her spot at the bus stop, she sees a couple fighting, kids playing, two men laughing together in joy, and a person in intense concentration, ambiguous to me as to whether he's reading something and focusing or grappling with a heavy decision internally. The complexity of the world hits her as a tear rolls down her cheek (and mine!!!).

When I talk to people about Barbie, we all have such different thoughts on the film--especially for us women, nonbinary people, and both trans men and trans women. The doll is such a huge part of our culture and impacted us in different ways. Barbie has a complicated history that Greta Gerwig actually does a pretty good job of addressing. The Oppenheimer movie does not particularly look at the atomic bomb and its history with the same level of complexity; rather, Oppenheimer himself pivots from singlemindedly leading the research and creation of the bomb "for science" to then later singlemindedly protesting the hydrogen bomb. Yes, it shows him as a human capable of changing his mind, but doesn't get into the more specific nuances of it. He's first very for the atomic bomb and then very against the hydrogen bomb. Barbie, on the other hand, represents SO MUCH. Femininity both as power and as critique. Being everything (all of the different Barbies as a group) vs being one thing (Barbie as an individual, the character; made for a specific idea). Barbie as the trappings of gender roles vs. Barbie as uplifting. Barbie is everything, good and bad.

Yeah, there are issues with both films. Oppenheimer has some very weak dialogue, and Oppenheimer himself is, uh...problematic, as we say? Barbie has pretty paper thin Feminism 101. It never gets into how capitalism specifically impacts feminism and seeks to uphold gender roles and gendered expectations. It's definitely not Marxist, h aha. (But I also never expected it to tackle that. After all, it's still produced by Warner Bros and Mattel.)

I didn't expect Oppenheimer to be so dreamlike. And I definitely didn't expect Barbie to give me so many emotions about mothers and daughters and becoming your own person, going beyond the story made for you. That's what made me cry in Barbie during the final montage of childhood memories from all the staff/cast members on the project.

#rose rambles#rose reviews#I guess we're making that a tag now for me to ramble about stuff I watch and play#not so much a review-review as it is just my rambley thoughts#oppenheimer#barbie

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppenheimer

"Oppenheimer": Christopher Nolan's Upcoming Epic Film on the Father of the Atomic Bomb

The name J. Robert Oppenheimer is synonymous with the dawn of the atomic age and the complex ethical and scientific questions that came with it. Now, acclaimed director Christopher Nolan is set to bring this enigmatic figure to life in his upcoming epic film, "Oppenheimer." With a stellar cast, a visionary director, and a fascinating historical backdrop, this movie is poised to be a cinematic masterpiece that delves into the life of one of the 20th century's most influential scientists.

The Man Behind the Bomb:

J. Robert Oppenheimer, often referred to as the "father of the atomic bomb," was an American theoretical physicist. He played a pivotal role in the development of the atomic bomb during World War II as part of the Manhattan Project. His work on the bomb's design and the successful testing of the first atomic bomb at the Trinity test site in New Mexico marked a turning point in human history.

Christopher Nolan's Ambitious Project:

Director Christopher Nolan is known for his ambitious and visually stunning films, such as "Inception," "Interstellar," and "Dunkirk." "Oppenheimer" is set to be another grand cinematic endeavor for the director, exploring the life and times of this complex historical figure.

The Cast:

The film boasts a star-studded cast, with Academy Award-winning actor Cillian Murphy set to play the titular role of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Murphy's collaboration with Christopher Nolan in films like "Inception" and "The Dark Knight" trilogy has been critically acclaimed, making him an ideal choice to portray the brilliant yet conflicted physicist.

Other notable cast members include Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, and Robert Downey Jr., adding depth and talent to an already impressive ensemble.

Exploring Ethical Dilemmas:

The story of Oppenheimer is not just one of scientific achievement but also of profound ethical dilemmas. The development and use of the atomic bomb raised questions about the moral responsibility of scientists and the devastating consequences of their creations. This film is expected to delve into these issues, providing a thought-provoking narrative that goes beyond the historical events.

Historical Accuracy:

"Oppenheimer" is expected to meticulously capture the historical details of the Manhattan Project, the complexities of Oppenheimer's personal and professional life, and the political climate of the time. The film promises to offer viewers a glimpse into the tension, secrecy, and urgency of the wartime scientific community.

Anticipation and Expectations:

With Christopher Nolan at the helm and a cast of this caliber, "Oppenheimer" has generated considerable excitement among film enthusiasts and history buffs alike. It promises to be a compelling blend of historical drama, ethical exploration, and Nolan's signature cinematic flair.

Conclusion:

"Oppenheimer" is poised to be a cinematic event that not only entertains but also prompts audiences to ponder the profound ethical questions surrounding scientific progress and the responsibilities of those who shape it. With an iconic director, an exceptional cast, and a captivating subject, the film has the potential to be a milestone in the portrayal of historical events on the big screen. As we eagerly await its release, "Oppenheimer" is already generating buzz as a movie that will challenge and captivate viewers in equal measure.

0 notes

Text

LONG POST

Justin Chang on Oppie not showing Japan.

LATimes (Refrigerator Magnet): ‘Oppenheimer’ doesn’t show us Hiroshima and Nagasaki. That’s an act of rigor, not erasure

By Justin Chang, Film Critic Aug. 11, 2023

The key word in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is “compartmentalization.” It’s a security strategy, introduced and repeatedly enforced by Col. Leslie R. Groves (Matt Damon) in his capacity as director of the Manhattan Project, which is racing to build a weapon mighty enough to bring World War II to an end. In Groves’ mind, keeping his various teams walled off from one another will help ensure the strictest secrecy. But J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the brilliant theoretical physicist he’s hired to run the project laboratory in Los Alamos, N.M., knows that compartmentalization has its limits. The success of their mission will hinge not on isolation but on an extraordinary collaborative synthesis — of physics and chemistry, theory and practice, science and the military, the professional and the personal.

In the weeks since “Oppenheimer” opened to much critical acclaim and commercial success, Groves’ key word has taken on an unsettling new meaning. Compartmentalization, after all, is a pretty good synonym for rationalization, the act of setting aside, or even tucking away, whatever we find morally troubling. And for its toughest critics, many of them interviewed for a recent Times piece by Emily Zemler, “Oppenheimer” compartmentalizes to an outrageous degree: In not depicting the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they argue, the movie submits to a historical blindness that it risks passing on to its audience. Nolan, known for crafting fastidiously well-organized narratives in which nothing appears by accident, has been taken to task for what he chooses not to show.

Most of those decisions, of course, flow directly from his source material, “American Prometheus,” Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s authoritative 2005 Oppenheimer biography. With the exception of one key narrative thread, everything onscreen is framed, per biopic convention, through its subject’s eyes. And so you see Oppenheimer as an excitable young physics student, and you behold his eerie, captivating visions of the subatomic world. You see him become one of America’s leading physicists, take a major role in the secret race to the A-bomb and, together with his recruits, devise and build the world’s first nuclear weapons. You see his shock and awe when the Trinity test proves successful, lighting up the desert sky and landscape with a blinding flash of white and a 40,000-foot pillar of fire and smoke.

What you don’t see — because Oppenheimer doesn’t see them either — are the bomb’s first victims: the thousands of New Mexicans, most of them Native American and Hispanic, who dwell within a 50-mile radius of the Trinity test site and whose exposure to radiation will have deadly health consequences for generations. You don’t see the bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; you don’t see the lethal conflagrations and ash-covered rubble, and you don’t see the bodies of Japanese victims burned beyond recognition, or hear the screams and wails of survivors. (Estimates place the eventual death toll at close to 200,000.)

In refusing to visualize these horrors, is Nolan showing admirable dramatic restraint or committing unforgivable sins of omission? Is he merely sticking to his subject’s perspective or conveniently dodging the kind of imagery that would trouble Oppenheimer’s conscience?

As it happens, the scientist does in fact see that imagery, and his conscience is duly troubled. In one key scene, the camera studies Oppenheimer and his colleagues as they watch disturbing footage of the bombings’ aftermath. An offscreen speaker describes how thousands of Japanese civilians were incinerated in an instant, while thousands more died excruciating deaths from radiation poisoning. You see Oppenheimer recoil, even if what he recoils from is left pointedly out of frame.

These are not the only images of WWII that the movie withholds. It’s a measure of the formal and structural rigor of “Oppenheimer” that we see nothing of the Pacific theater conflict, and nothing of the European theater conflict, either — not even when Oppenheimer fears that the Nazis might be building a nuclear weapon of their own. Nolan, who always trusts us to keep up with his elaborately constructed puzzle-box narratives, also trusts us to know a thing or two about history. And crucially, he wants to open up a different perspective on the war, to show how some of its most crucial tactics and maneuvers played out not on battlefields but in classrooms and laboratories — and, finally, in the theater of Oppenheimer’s mind.

We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure.

It’s a brilliant mind, to say the least. It’s also ill prepared for the terrifying, world-altering reality that it ushers into being. Oppenheimer may see footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but images are a poor substitute for reality; he will never walk among the ruins, witness the despair of the survivors or behold the devastation up close. Nolan knows that we can’t either. What’s more, he clearly believes that we shouldn’t be able to.

Seen in this light, the director’s refusal to thrust his camera onto Japanese soil, far from being an act of historical vagueness or obliviousness, instead represents a carefully thought-out, rigorously executed solution to the problem of how to represent history. And his solution speaks not to his insensitivity but his integrity, his refusal to exploit or trivialize Japanese suffering by re-enacting it for the camera. Nolan lays the groundwork in one of his most revealing scenes, shortly before the decision is made to target Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As Oppenheimer looks on, U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (James Remar) removes Kyoto from the list of potential targets, citing the city’s cultural and historical significance and fondly recalling that he and his wife honeymooned there years earlier.

Before the bombings have even taken place, Nolan, in this one scene, indicts the arbitrary callousness of a U.S. war machine that cloaks its destructive intentions in cultural high-mindedness and rank sentimentality. It’s an appalling moment, and Stimson unambiguously solicits Oppenheimer’s contempt as well as the viewer’s; watch that scene in a packed house and you’ll hear the audience scoff as one. You might also begin to suspect, if you haven’t already, that Nolan isn’t going to dramatize the bombings in straightforward fashion, if he means to dramatize them at all.

Nolan has never been turned on by spectacles of violence. Even “Dunkirk,” a harrowing if ultimately optimistic World War II bookend of sorts to “Oppenheimer’s” apocalyptic despair, is a combat picture far more driven by ideas than by carnage. Violence certainly plays its part in Nolan’s movies, but seldom is it an end in itself. Reviewing “Oppenheimer” in the New York Times, Manohla Dargis noted, “There are no documentary images of the dead or panoramas of cities in ashes, decisions that read as [Nolan’s] ethical absolutes.” And in a recent Decider essay, the critic Glenn Kenny shrewdly examined “Oppenheimer” alongside Alain Resnais’ elliptical 1959 masterpiece, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” itself a powerful commentary on the futility of trying to represent the unrepresentable. “Had Nolan chosen to somehow ‘recreate’ the bombing of Hiroshima,” Kenny writes, “we, the viewers, would really see nothing.”

Japanese filmmakers, of course, have been powerfully evoking and re-creating the bombings for decades: Kaneto Shindo’s “Children of Hiroshima” (1952) and especially Shohei Imamura’s devastating “Black Rain” (1989) are just two well-known examples. Over the past few weeks, social media users have circulated clips of Mori Masaki’s 1983 anime “Barefoot Gen,” an adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa’s manga series of the same title. It contains what is surely one of the cinema’s most upsetting, unsparingly graphic depictions of the atomic blast and its casualties. It’s one of several animated films, including Renzo and Sayoko Kinoshita’s 1978 short “Pica-don” and Sunao Katabuchi’s “In This Corner of the World” (2016), that have confronted the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with a boldness and artistry that live-action cinema can be hard-pressed to match.

Much of this evidence has been marshaled in Nolan’s defense: Surely this is Japan’s story to tell, not his. I’m reluctant to embrace that particular stay-in-your-lane logic, which is ultimately deadening to the cause of art and empathy. As Clint Eastwood demonstrated in “Letters From Iwo Jima,” it is not beyond a white Hollywood filmmaker’s ability to enter persuasively and movingly into the mindset of a wartime enemy. Even so, that clearly isn’t the story Nolan is telling. And with such a wealth and variety of Japanese fiction and nonfiction filmmaking on the atomic bombings already, why should “Oppenheimer” bear the responsibility of representing events and experiences that fall outside its subject’s perspective?

Some would rebut that “Oppenheimer,” being a Hollywood blockbuster with serious global reach (whether it will play Japanese theaters remains uncertain), will be many audiences’ only exposure to the events in question and thus might “create a limit on public consciousness and concern,” as the poet, writer and professor Brandon Shimoda told The Times. A corollary of this argument: The crimes committed against the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were so unspeakable, so outsized in their impact, that Oppenheimer’s perspective does and should dwindle into insignificance by comparison. For Nolan to focus so exclusively on an American physicist’s story, some insist, ultimately diminishes history and humanity, even as it reinforces the Hollywood hegemony of the great-man biopic and of white men’s narratives in general.

I get those complaints. I also think they betray an inherent disrespect for the audience’s intelligence and curiosity, as well as a fundamental misunderstanding of how movies operate. It’s telling that few of these criticisms of perspective were leveled at “American Prometheus” when it was published in 2005, that no one begrudged Bird and Sherwin for offering a meticulously researched, morally ambivalent portrait of their subject’s life and consigning the destruction of two Japanese cities to a few pages. That’s because books are books, the argument goes, and movies are movies — and this perceived difference, it must be said, reveals a pernicious double standard.

Because they seldom achieve the narrative penetration and richness of detail of, say, a 700-page biography, movies, especially those about history, often are hailed as achievements of breadth over depth, emotion over intellect. They are assumed to be fundamentally shallow experiences, distillations of real life rather than sharply angled explorations of it, propelled by broad brushstrokes and easy expository shortcuts, and beholden to the audience’s presumably voracious appetite for thrilling, traumatizing spectacle. And because movies offer a visual immediacy and narrative immersion that books don’t, they are expected to be sweeping if not omniscient in their narrative scope, to reach for a comprehensive, even definitive vantage.

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

A film like “Oppenheimer” offers a welcome challenge to these assumptions. Like nearly all Nolan’s movies, from “Memento” to “Dunkirk,” it’s a crafty exercise in radical subjectivity and narrative misdirection, in which the most significant subjects — lost memories, lost time, lost loves — often are invisible and all the more powerful for it. We can certainly imagine a version of “Oppenheimer” that tossed in a few startling but desultory minutes of Japanese destruction footage. Such a version might have flirted with kitsch, but it might well have satisfied the representational completists in the audience. It also would have reduced Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a piddling afterthought; Nolan treats them instead as a profound absence, an indictment by silence.

That’s true even in one of the movie’s most powerful and contested sequences. Not long after news of Hiroshima’s destruction arrives, Oppenheimer gives a would-be-triumphant speech to a euphoric Los Alamos crowd, only for his words to turn to dust in his mouth. For a moment, Nolan abandons realism altogether — but not, crucially, Oppenheimer’s perspective — to embrace a hallucinatory horror-movie expressionism. A piercing scream erupts in the crowd; a woman’s face crumples and flutters, like a paper mask about to disintegrate. The crowd is there and then suddenly, with much sonic rumbling, image blurring and an obliterating flash of white light, it is not.

For “Oppenheimer’s” detractors, this sequence constitutes its most grievous act of erasure: Even in the movie’s one evocation of nuclear disaster, the true victims have been obscured and whitewashed. The absence of Japanese faces and bodies in these visions is indeed striking. It’s also consistent with Nolan’s strict representational parameters, and it produces a tension, even a contradiction, that the movie wants us to recognize and wrestle with. Is Oppenheimer trying (and failing) to imagine the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians murdered by the weapon he devised? Or is he envisioning some hypothetical doomsday scenario still to come?

I think the answer is a blur of both, and also something more: In this moment, one of the movie’s most abstract, Nolan advances a longer view of his protagonist’s history and his future. Oppenheimer’s blindness to Japanese victims and survivors foreshadows his own stubborn inability to confront the consequences of his actions in years to come. He will speak out against nuclear weaponry, but he will never apologize for the atomic bombings of Japan — not even when he visits Tokyo and Osaka in 1960 and is questioned by a reporter about his perspective now. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he will respond. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Talk about compartmentalization. That episode, by the way, doesn’t find its way into “Oppenheimer,” which knows better than to offer itself up as the last word on anything. To the end, Nolan trusts us to seek out and think about history for ourselves. If we elect not to, that’s on us.

(Photo) Cillian Murphy plays the title role in the movie “Oppenheimer.”

(Universal Pictures) #EducationalPurposesOnly

0 notes

Text

Assistir Filme Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie Online fácil

Assistir Filme Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie Online Fácil é só aqui: https://filmesonlinefacil.com/filme/trinity-and-beyond-the-atomic-bomb-movie/

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie - Filmes Online Fácil

"Trinity and Beyond" é um documentário inquietante, mas visualmente fascinante, apresentando a história do desenvolvimento de armas nucleares e testes entre 1945-1963. Narrado por William Shatner e apresentando uma pontuação original realizada pela Orquestra Sinfônica de Moscou, este documentário premiado revela imagens governamentais não relacionadas anteriormente e classificadas de vários países.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Castle Bravo, detonated on February 28, 1954 at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific, was the largest nuclear device ever detonated by America, possessing a yield equivalent of 15 megatons of TNT. The blast was 2.5 times more powerful than the planned 6 megatons, due to unforeseen reactions between the lithium deuteride booster and the hydrogen fuel core, which led to extensive radioactive contamination not only of Bikini Atoll (whose residents had been relocated in 1946 by the US military for its use in nuclear tests) but also of neighboring Rongelap and Utirik atolls, which were still inhabited.

The residents of these atolls were not evacuated until several days after the blast, and were exposed to high levels of radiation and suffered severe radiation sickness. They were treated after evacuation, and in 1956 began receiving compensation from the US government relative to how much contamination was received. In 1957 the Atomic Energy Commission deemed Rongelap Atoll safe to return to, and allowed 82 inhabitants to move back to the island. Upon their return, however, they found that their previous staple foods, such as arrowroot and fish, had either disappeared or gave them illness, and they were again removed. Ultimately, 15 islands and atolls in the Marshall Islands were contaminated by Castle Bravo, and in the decades that followed residents of the fallout zone suffered high numbers of thyroid tumors and birth defects, as well as other illnesses.

Film clip from the 1995 documentary “Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie”

Music composed by William T. Stromberg and performed by the Moscow Symphony Orchestra conducted by Stromberg himself.

#Castle Bravo#Bikini Atoll#Trinity and Beyond#Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie#1950s#Cold War#Nuclear Testing#historical#US history

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

364. Trinity And Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie (Peter Kuran, USA, 1995)

#trinity and beyond#trinity and beyond: the atomic bomb movie#peter kuran#usa#1995#1990s#documentary#william shatner#nuclear war#nuclear weapons#trinity test#tsar bomba

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie (Peter Kuran, 1995).

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The key word in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is “compartmentalization.” It’s a security strategy, introduced and repeatedly enforced by Col. Leslie R. Groves (Matt Damon) in his capacity as director of the Manhattan Project, which is racing to build a weapon mighty enough to bring World War II to an end. In Groves’ mind, keeping his various teams walled off from one another will help ensure the strictest secrecy. But J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the brilliant theoretical physicist he’s hired to run the project laboratory in Los Alamos, N.M., knows that compartmentalization has its limits. The success of their mission will hinge not on isolation but on an extraordinary collaborative synthesis — of physics and chemistry, theory and practice, science and the military, the professional and the personal.

In the weeks since “Oppenheimer” opened to much critical acclaim and commercial success, Groves’ key word has taken on an unsettling new meaning. Compartmentalization, after all, is a pretty good synonym for rationalization, the act of setting aside, or even tucking away, whatever we find morally troubling. And for its toughest critics, many of them interviewed for a recent Times piece by Emily Zemler, “Oppenheimer” compartmentalizes to an outrageous degree: In not depicting the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they argue, the movie submits to a historical blindness that it risks passing on to its audience. Nolan, known for crafting fastidiously well-organized narratives in which nothing appears by accident, has been taken to task for what he chooses not to show.

Most of those decisions, of course, flow directly from his source material, “American Prometheus,” Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s authoritative 2005 Oppenheimer biography. With the exception of one key narrative thread, everything onscreen is framed, per biopic convention, through its subject’s eyes. And so you see Oppenheimer as an excitable young physics student, and you behold his eerie, captivating visions of the subatomic world. You see him become one of America’s leading physicists, take a major role in the secret race to the A-bomb and, together with his recruits, devise and build the world’s first nuclear weapons. You see his shock and awe when the Trinity test proves successful, lighting up the desert sky and landscape with a blinding flash of white and a 40,000-foot pillar of fire and smoke.

What you don’t see — because Oppenheimer doesn’t see them either — are the bomb’s first victims: the thousands of New Mexicans, most of them Native American and Hispanic, who dwell within a 50-mile radius of the Trinity test site and whose exposure to radiation will have deadly health consequences for generations. You don’t see the bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; you don’t see the lethal conflagrations and ash-covered rubble, and you don’t see the bodies of Japanese victims burned beyond recognition, or hear the screams and wails of survivors. (Estimates place the eventual death toll at close to 200,000.)

In refusing to visualize these horrors, is Nolan showing admirable dramatic restraint or committing unforgivable sins of omission? Is he merely sticking to his subject’s perspective or conveniently dodging the kind of imagery that would trouble Oppenheimer’s conscience?

As it happens, the scientist does in fact see that imagery, and his conscience is duly troubled. In one key scene, the camera studies Oppenheimer and his colleagues as they watch disturbing footage of the bombings’ aftermath. An offscreen speaker describes how thousands of Japanese civilians were incinerated in an instant, while thousands more died excruciating deaths from radiation poisoning. You see Oppenheimer recoil, even if what he recoils from is left pointedly out of frame.

These are not the only images of WWII that the movie withholds. It’s a measure of the formal and structural rigor of “Oppenheimer” that we see nothing of the Pacific theater conflict, and nothing of the European theater conflict, either — not even when Oppenheimer fears that the Nazis might be building a nuclear weapon of their own. Nolan, who always trusts us to keep up with his elaborately constructed puzzle-box narratives, also trusts us to know a thing or two about history. And crucially, he wants to open up a different perspective on the war, to show how some of its most crucial tactics and maneuvers played out not on battlefields but in classrooms and laboratories — and, finally, in the theater of Oppenheimer’s mind.

We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure.

It’s a brilliant mind, to say the least. It’s also ill prepared for the terrifying, world-altering reality that it ushers into being. Oppenheimer may see footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but images are a poor substitute for reality; he will never walk among the ruins, witness the despair of the survivors or behold the devastation up close. Nolan knows that we can’t either. What’s more, he clearly believes that we shouldn’t be able to.

Seen in this light, the director’s refusal to thrust his camera onto Japanese soil, far from being an act of historical vagueness or obliviousness, instead represents a carefully thought-out, rigorously executed solution to the problem of how to represent history. And his solution speaks not to his insensitivity but his integrity, his refusal to exploit or trivialize Japanese suffering by re-enacting it for the camera. Nolan lays the groundwork in one of his most revealing scenes, shortly before the decision is made to target Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As Oppenheimer looks on, U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (James Remar) removes Kyoto from the list of potential targets, citing the city’s cultural and historical significance and fondly recalling that he and his wife honeymooned there years earlier.

Before the bombings have even taken place, Nolan, in this one scene, indicts the arbitrary callousness of a U.S. war machine that cloaks its destructive intentions in cultural high-mindedness and rank sentimentality. It’s an appalling moment, and Stimson unambiguously solicits Oppenheimer’s contempt as well as the viewer’s; watch that scene in a packed house and you’ll hear the audience scoff as one. You might also begin to suspect, if you haven’t already, that Nolan isn’t going to dramatize the bombings in straightforward fashion, if he means to dramatize them at all.

Nolan has never been turned on by spectacles of violence. Even “Dunkirk,” a harrowing if ultimately optimistic World War II bookend of sorts to “Oppenheimer’s” apocalyptic despair, is a combat picture far more driven by ideas than by carnage. Violence certainly plays its part in Nolan’s movies, but seldom is it an end in itself. Reviewing “Oppenheimer” in the New York Times, Manohla Dargis noted, “There are no documentary images of the dead or panoramas of cities in ashes, decisions that read as [Nolan’s] ethical absolutes.” And in a recent Decider essay, the critic Glenn Kenny shrewdly examined “Oppenheimer” alongside Alain Resnais’ elliptical 1959 masterpiece, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” itself a powerful commentary on the futility of trying to represent the unrepresentable. “Had Nolan chosen to somehow ‘recreate’ the bombing of Hiroshima,” Kenny writes, “we, the viewers, would really see nothing.”

Japanese filmmakers, of course, have been powerfully evoking and re-creating the bombings for decades: Kaneto Shindo’s “Children of Hiroshima” (1952) and especially Shohei Imamura’s devastating “Black Rain” (1989) are just two well-known examples. Over the past few weeks, social media users have circulated clips of Mori Masaki’s 1983 anime “Barefoot Gen,” an adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa’s manga series of the same title. It contains what is surely one of the cinema’s most upsetting, unsparingly graphic depictions of the atomic blast and its casualties. It’s one of several animated films, including Renzo and Sayoko Kinoshita’s 1978 short “Pica-don” and Sunao Katabuchi’s “In This Corner of the World” (2016), that have confronted the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with a boldness and artistry that live-action cinema can be hard-pressed to match.

Much of this evidence has been marshaled in Nolan’s defense: Surely this is Japan’s story to tell, not his. I’m reluctant to embrace that particular stay-in-your-lane logic, which is ultimately deadening to the cause of art and empathy. As Clint Eastwood demonstrated in “Letters From Iwo Jima,” it is not beyond a white Hollywood filmmaker’s ability to enter persuasively and movingly into the mindset of a wartime enemy. Even so, that clearly isn’t the story Nolan is telling. And with such a wealth and variety of Japanese fiction and nonfiction filmmaking on the atomic bombings already, why should “Oppenheimer” bear the responsibility of representing events and experiences that fall outside its subject’s perspective?

Some would rebut that “Oppenheimer,” being a Hollywood blockbuster with serious global reach (whether it will play Japanese theaters remains uncertain), will be many audiences’ only exposure to the events in question and thus might “create a limit on public consciousness and concern,” as the poet, writer and professor Brandon Shimoda told The Times. A corollary of this argument: The crimes committed against the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were so unspeakable, so outsized in their impact, that Oppenheimer’s perspective does and should dwindle into insignificance by comparison. For Nolan to focus so exclusively on an American physicist’s story, some insist, ultimately diminishes history and humanity, even as it reinforces the Hollywood hegemony of the great-man biopic and of white men’s narratives in general.

I get those complaints. I also think they betray an inherent disrespect for the audience’s intelligence and curiosity, as well as a fundamental misunderstanding of how movies operate. It’s telling that few of these criticisms of perspective were leveled at “American Prometheus” when it was published in 2005, that no one begrudged Bird and Sherwin for offering a meticulously researched, morally ambivalent portrait of their subject’s life and consigning the destruction of two Japanese cities to a few pages. That’s because books are books, the argument goes, and movies are movies — and this perceived difference, it must be said, reveals a pernicious double standard.

Because they seldom achieve the narrative penetration and richness of detail of, say, a 700-page biography, movies, especially those about history, often are hailed as achievements of breadth over depth, emotion over intellect. They are assumed to be fundamentally shallow experiences, distillations of real life rather than sharply angled explorations of it, propelled by broad brushstrokes and easy expository shortcuts, and beholden to the audience’s presumably voracious appetite for thrilling, traumatizing spectacle. And because movies offer a visual immediacy and narrative immersion that books don’t, they are expected to be sweeping if not omniscient in their narrative scope, to reach for a comprehensive, even definitive vantage.

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

A film like “Oppenheimer” offers a welcome challenge to these assumptions. Like nearly all Nolan’s movies, from “Memento” to “Dunkirk,” it’s a crafty exercise in radical subjectivity and narrative misdirection, in which the most significant subjects — lost memories, lost time, lost loves — often are invisible and all the more powerful for it. We can certainly imagine a version of “Oppenheimer” that tossed in a few startling but desultory minutes of Japanese destruction footage. Such a version might have flirted with kitsch, but it might well have satisfied the representational completists in the audience. It also would have reduced Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a piddling afterthought; Nolan treats them instead as a profound absence, an indictment by silence.

That’s true even in one of the movie’s most powerful and contested sequences. Not long after news of Hiroshima’s destruction arrives, Oppenheimer gives a would-be-triumphant speech to a euphoric Los Alamos crowd, only for his words to turn to dust in his mouth. For a moment, Nolan abandons realism altogether — but not, crucially, Oppenheimer’s perspective — to embrace a hallucinatory horror-movie expressionism. A piercing scream erupts in the crowd; a woman’s face crumples and flutters, like a paper mask about to disintegrate. The crowd is there and then suddenly, with much sonic rumbling, image blurring and an obliterating flash of white light, it is not.

For “Oppenheimer’s” detractors, this sequence constitutes its most grievous act of erasure: Even in the movie’s one evocation of nuclear disaster, the true victims have been obscured and whitewashed. The absence of Japanese faces and bodies in these visions is indeed striking. It’s also consistent with Nolan’s strict representational parameters, and it produces a tension, even a contradiction, that the movie wants us to recognize and wrestle with. Is Oppenheimer trying (and failing) to imagine the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians murdered by the weapon he devised? Or is he envisioning some hypothetical doomsday scenario still to come?

I think the answer is a blur of both, and also something more: In this moment, one of the movie’s most abstract, Nolan advances a longer view of his protagonist’s history and his future. Oppenheimer’s blindness to Japanese victims and survivors foreshadows his own stubborn inability to confront the consequences of his actions in years to come. He will speak out against nuclear weaponry, but he will never apologize for the atomic bombings of Japan — not even when he visits Tokyo and Osaka in 1960 and is questioned by a reporter about his perspective now. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he will respond. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Talk about compartmentalization. That episode, by the way, doesn’t find its way into “Oppenheimer,” which knows better than to offer itself up as the last word on anything. To the end, Nolan trusts us to seek out and think about history for ourselves. If we elect not to, that’s on us.'

#Christopher Nolan#Oppenheimer#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Cillian Murphy#Los Alamos#The Manhattan Project#Hiroshima#Nagasaki#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Hiroshima Mon Amour#Dunkirk#Letters from Iwo Jima#Clint Eastwood

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: it’s Friday night! What do you want to do?

Brain: we should do something rewarding.

Me: I know exactly what we should do!

Brain: me too! Let’s both say it on three. One! Two! Three!

Brain: WRITE!

Me: GET TOASTY AND WATCH THE ATOMIC BOMB MOVIE!

Brain: ...

Brain: ... what

Brain: how is that rewarding.

Me: *mumbles* your face is rewarding.

Me: not

Me: you’re ugly

Brain: I’m also you

Me: well we aren’t smart, and that’s YOUR fault

Brain: ...

Brain: fuck

Me: nothing like existential dread about a very real and growing fear I have! It’s the best

Brain: why are you oh. That’s me too. WHAT THE FUCK

#writing#writing is hard#friday nights#trinity and beyond#the atomic bomb movie#if you haven’t see that shit#why#why haven’t you?#whyyyyyy

3 notes

·

View notes

Audio

William T. Stromberg | Castle Bravo

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie (1995)

#William Stromberg#William T Stromberg#Castle Bravo#Trinity and Beyond#The Atomic Bomb Movie#music#films#soundtrack

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s some recommended books and movies from the last two pages of Interplay’s old Fallout TTRPG core book;

Books

Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank. Available from Harper Perennial, 1999.

Apocalypse Movies: End of the World Cinema by Kim Newman. Available from Griffin Trade Paperbacks, 1998.

Bangs and Whimpers: Stories About the End of the World, edited by James Frenkel. Available from Lowell House, 1999.

Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut. Available from Bantam-Doubleday Dell, 1963.

Danse Macabre by Stephen King. Available from Viking, 1981.

Earth by David Brin. Available from Bantam Books, 1990.

Earth Abides by George R. Stewart. Available from Fawcett Books, 1989.

The Effects of Nuclear Weapons: 3rd Edition (1977), edited by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan. Available from United States Department of Defense, 1977.

Lucifer’s Hammer by Larry Niven and Jerru Pournelle. Available from Fawcett Paperbacks, 1977.

The New Madrid Run by Michael Resig. Available from Clear Creek Press, 1998.

On the Beach by Nevil Shute. Available from Ballantine Mass Market Paperback, 1989.

The Postman by David Brin. Available from Bantam Books, 1997.

The Stand: Complete and Uncut by Stephen King. Available from the New American Library, 1991.

153 The Third World War: August 1985 by General Sir John Hackett, et al. Available from McMillan, 1979.

Movies

Atomic Journeys: Welcome to Ground Zero, 1999 documentary, directed by Peter Kuran.

The Atomic Café, 1983 documentary, directed by Jayne Loader and Kevin Rafferty.

A Boy and His Dog, 1975 post-nuclear action, directed by L.Q. Jones. Based on a novella by Harlan Ellison.

The Day After, 1983 made-for-television movie.

Mad Max, The Road Warrior, and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, 1979, 1981, and 1985 post-nuclear action.

Nukes in Space: The Rainbow Bombs, 2000 documentary, directed by Peter Kuran.

On the Beach, 1959 drama. On the Beach, 2000 drama (miniseries).

The Postman, 1997 post-nuclear action/drama/epic, directed by and starring Kevin Costner.

Stephen King’s The Stand, 1994 miniseries.

Threads, 1985 made-for-television movie.

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie, 1997 documentary, directed by Peter Kuran.

Waterworld, 1995 post-nuclear wet-n-wild action, directed by Kevin Reynolds.

#fallout#post-apoc#post-apocalypse#classic fallout#interplay#falloutfun#longpost#long post#fallout 1#fallout 2#fallout 3#fallout 4#fo1#fo2#fo3#fo4

383 notes

·

View notes