#Rhus glabra

Text

Rhus glabra / Smooth Sumac at the Sarah P. Duke Gardens at Duke University in Durham, NC

#Rhus glabra#Rhus#Smooth Sumac#Sumac#Native plants#Edible plants#Foliage#Nature photography#photographers on tumblr#Sarah P. Duke Gardens#Duke Gardens#Duke University#Durham#Durham NC#North Carolina

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scientific Name: Rhus glabra

Common Name(s): Smooth sumac

Family: Anacardiaceae (cashew)

Life Cycle: Perennial

Leaf Retention: Deciduous

Habit: Shrub

USDA L48 Native Status: Native

Location: Allen, Texas

Season(s): Winter

After the leaves drop, flame-shaped clusters of red fruit remain on the ends of bare branches and make these colony-forming shrubs appear as if they’re collections of gnarled candelabra. Since the fruits stay on the plant throughout winter, they become important sources of nourishment for wildlife when other foods become scarce. From a distance, smooth sumac and staghorn sumac (R. typhina) may be difficult to tell apart, but up close we can observe the fine hairs on a staghorn sumac’s branches — resembling deer antlers “in velvet” and giving rise to its common name — which are absent on smooth sumac. Both of these can be distinguished from poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), which has white fruit.

#Rhus glabra#smooth sumac#Anacardiaceae#perennial#deciduous#shrub#native#Allen#Texas#winter#fruit#red#sumac#edible plants#plantblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An App Does Not a Master Naturalist Make

Originally posted on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com/app-not-master-naturalist/ - I had written this as an op-ed and sent it to WaPo, but they had no interest, so you get to read it here instead!

I have mixed feelings about Michael Coren’s April 25 Washington Post article, “These 4 free apps can help you identify every flower, plant and tree around you.” His ebullience at exploring some of the diverse ecological community around him made me grin, because I know exactly what it feels like. There’s nothing like that sense of wonder and belonging when you go outside and are surrounded by neighbors of many species, instead of a monotonous wall of green, and that is a big part of what led me to become a Master Naturalist.

When I moved from the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest in 2006, I felt lost because I didn’t recognize many of the animals or plants in my new home. So I set about systematically learning every species that crossed my path. Later, I began teaching community-level classes on nature identification to help other people learn skills and tools for exploring their local flora, fauna, and fungi.

Threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata)

Let me be clear: I love apps. I use Merlin routinely to identify unknown bird songs, and iNaturalist is my absolute favorite ID app, period. But these tools are not 100% flawless.

For one thing, they’re only as good as the data you provide them. iNaturalist’s algorithms, for example, rely on a combination of photos (visual data), date and time (seasonal data), and GPS coordinates (location data) to make initial identification suggestions. These algorithms sift through the 135-million-plus observations uploaded to date, finding observations that have similar visual, seasonal, and location data to yours.

There have been many times over the years where iNaturalist isn’t so sure. Take this photo of a rather nondescript clump of grass. Without seed heads to provide extra clues, the algorithms offer an unrelated assortment of species, with only one grass. I’ve gotten that “We’re not confident enough to make a recommendation” message countless times over my years of using the app, often suggesting species that are clearly not what I’m looking at in real life.

Because iNaturalist usually offers up multiple options, you have to decide which one is the best fit. Sometimes it’s the first species listed, but sometimes it’s not. This becomes trickier if all the species that are suggested look alike. Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), smooth sumac (Rhus glabra) and eastern black walnut (Juglans nigra) all have pinnately compound, lanceolate leaves, and young plants of these three species can appear quite similar. If all you know how to do is point and click your phone’s camera, you aren’t going to be able to confidently choose which of the three plants is the right one.

Coren correctly points out that both iNaturalist and Pl@ntNet do offer more information on suggested species—if people are willing to take the time to look. Too many assume ID apps will give an easy, instant answer. In watching my students use the app in person almost everyone just picks the first species in the list. It’s not until I demonstrate how to access the additional content for each species offered that anyone thinks to question the algorithms’ suggestions.

While iNaturalist is one of the tools I incorporate into my classes, I emphasize that apps in general are not to be used alone, but in conjunction with field guides, websites, and other resources. Nature identification, even on a casual level, requires critical thinking and observation skills if you want to make sure you’re correct. Coren’s assertion that you only need a few apps demonstrates a misunderstanding of a skill that takes time and practice to develop properly—and accurately.

Speaking of oversimplification, apps are not a Master Naturalist in your pocket, and that statement —while meant as a compliment–does a disservice to the thousands of Master Naturalists across the country. While the training curricula vary from state to state, they are generally based in learning how organisms interact within habitats and ecosystems, often drawing on a synthesis of biology, geology, hydrology, climatology, and other natural sciences. A Master Naturalist could tell you not only what species you’re looking at, but how it fits into this ecosystem, how its adaptations are different from a related species in another ecoregion, and so forth.

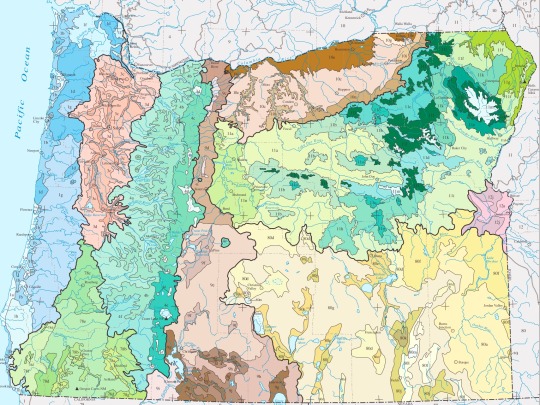

Map showing Level III and IV ecoregions of Oregon, the basis of my training as an Oregon Master Naturalist.

In spite of my criticisms, I do think that Coren was absolutely onto something when he described the effects of using the apps. Seeing the landscape around you turn from a green background to a vibrant community of living beings makes going outside a more exciting, personal experience. I and my fellow nature nerds share an intense curiosity about the world around us. And that passion, more than any app or other tool, is fundamental to becoming a citizen naturalist, Master or otherwise.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#iNaturalist#plant apps#Seek#Merlin#nature#wildlife#plant identification#apps#botany#biology#science#scicomm#science communication#Google Lens#naturalist#Master Naturalist#conservation#environment

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre aniline:

Until 1856, dyeing was only done with natural pigments. Plants, lichen, fungi and insects were all used in recipes to make good dyes. Anything that stains easily (see grass), generally doesn’t make good dye material. Mordents (look into more), bonded dye to fabric. This could also change the color, which made more varied shades available. Dye recipes were closely guarded (practical for them, annoying for researchers)

Yellow and tan dyes were pretty common. Sources for the new world (possible contenders are smooth sumac, rhus glabra, roots, and young cottonwood leaf buds) were easier to use than the European weld plant.

European woad was the main source of blue until indigofera was imported from tropical regions. Indigo actually produces a yellow color, until exposed to oxygen. To get dark blue, repeated dips into the dye bath and exposure to oxygen are needed.

Green dye was pretty much nonexistent. Chlorophyll doesn’t convert to dye. Some shades can be made, but deep green fabric would need to be yellow and then blue.

Cochineal insects from Mexico made Spaniards rich. Ground cochineal was vibrant, colorfast, and extremely popular.

Aniline:

In 1856, English chemist revolutionized dyeing. His dyes were made from synthesized coal tar, which came to be known as aniline. He first developed a mauve (purple), but other synthetic dyes for more hues were discovered. This allowed dyeing to be industrialized, no longer relying on expensive natural pigments. With dyes becoming more available, bright colors were much more explored.

@field-mouse-queen this gives more of a history than going into chemistry, especially for aniline dyes, but I’m tired so this’ll have to suffice.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Citheronia splendens, feasting on Rhus glabra. Old video but I think it might be cool to share some of these guys while they’re in diapause rn

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apothecary jars.

Rhus Glabra, ik, I looked it up -

Parts of smooth sumac have been used by various Native American tribes as an antiemetic, antidiarrheal, antihemorrhagic, blister treatment, cold remedy, emetic, mouthwash, asthma treatment, tuberculosis remedy, sore throat treatment, ear medicine, eye medicine, astringent, heart medicine, venereal aid, ulcer treatment, and to treat rashes. Staghorn sumac parts were used in similar medicinal remedies. The Natchez used the root of fragrant sumac to treat boils. The Ojibwa took a decoction of fragrant sumac root to stop diarrhea. The berries, roots, inner bark, and leaves of smooth and staghorn sumac were used to make dyes of various colors. The leaves of fragrant, staghorn and smooth sumac were mixed with tobacco and smoked by many tribes of the plains region.

Oleum Myrcie is the other. YOU look it up...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

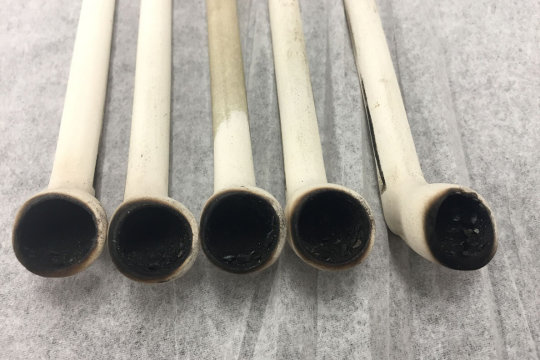

Non-tobacco plant identified in ancient pipe for first time

People in what is now Washington State were smoking Rhus glabra, a plant commonly known as smooth sumac, more than 1,400 years ago.

The discovery, made by a team of Washington State University researchers, marks the first-time scientists have identified residue from a non-tobacco plant in an archaeological pipe.

Unearthed in central Washington, the Native American pipe also contained residue from N. quadrivalvis, a species of tobacco not currently grown in the region but that is thought to have been widely cultivated in the past. Until now, the use of specific smoking plant mixtures by ancient people in the American Northwest had only been speculated about. Read more.

#archaeology#rhus glabra#archeology#washington state#native american#pipe#smoking#smooth sumac#tobacco

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Smooth sumac with a thick blanket of false aster

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lil baby pods in the park!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NEW PLANT IDENTIFIED IN 1,400-YEAR-OLD PIPE IN WASHINGTON

Rhus glabra, a herb commonly known as smooth sumac, was smoked by people in the Washington State more than 1.400 years ago.The finding was made by a team of researchers from the State University of Washington is the first time scientists in an archeological pipe have detected the remains of a non-tobacco plant. Read more...

#archaeology#usa#northamerica#old#pipes#washington#smoked#archaeological pipes#non-tobacco#plant#herb#rhus glabra

0 notes

Photo

Rhus glabra

Common name: Smooth Sumac

1 note

·

View note

Photo

RHUS GLABRA Smooth Sumach RHUS GLABRA Smooth Sumach Epistaxis and occipital headache. Fetid flatus. Ulceration of mouth. Dreams of flying through the air (Sticta).

0 notes

Photo

08.2020.

#photography#digital photography#original photography#photographers on tumblr#nature#sky#clouds#cloud#summer#august#rhus#rhus glabra laciniata#sumac#own#elisarde

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Problem Areas and Wild Weeds, ETC. Part 3...

Problem Areas and Wild Weeds, ETC. Part 3…

Torilis japonica (Japanese Hedge Parsley)…

Hello everyone! I hope this post finds you well. October is here once again and some of the wildflowers aren’t looking their best. There are a lot of insects and butterflies feeding right now. I have taken a lot of photos the last few days and I am getting behind. 🙂 I now have 655 observations posted on iNaturalist covering 343 species.

This saga of the…

View On WordPress

#Danaus plexippus (Monarch Butterfly)#Eleusine indica (Goosegrass)#Eupatorium altissimum (Tall Thoroughwort)#Eupatorium serotinum (Late Boneset)#Persicaria hydropiper (Water Pepper)#Persicaria pensylvanica (Pinkweed)#Rhus glabra (Smooth Sumac)#Symphyotrichum novae-angliae (New England Aster)#Torilis japonica (Upright/Japanese Hedge Parsley)#Vernonia missurica (Missouri Ironweed)#Xanthium strumarium (Rough Cocklebur)

0 notes

Text

Been going on outings recently so I decided I’d make some longer posts detailing observations and stuff I find while I’m out! This’ll be the first post of such a kind-

See these tall stocky stems? That’s Rhus glabra, and last year I used these plants to feed Citheronia splendens caterpillars I had purchased. Over the winter all their branches fell off which made me concerned if I had taken too many branches myself; but they seem to be regrowing! New leaves are growing in and there might even be tiny branches! I did find one dead plant which sucks, but thankfully the rest seem to be recovering. Potential food for if my C. splendens moths have a new generation of caterpillars.

A new friend I found! So, there’s this area near my house that has a TERRIBLE garlic mustard problem. It’s something I really want to address myself, so I started today by uprooting a few plants, and underneath the roots of one was this fella!

They’re a black soldier fly larva (Hermetia illucens) and the species plays a very important role in the ecosystem by eating just about anything, having rich frass (poop), and being a rich food source themselves. Wonderful feeder insect and an important little grubby.

CW. Decaying bugs

I took this individual home to try and raise them. I have a little cup with decaying superworms I think might be good food for them, so I’ll keep them around for a bit. Truth be told I’ll likely forget about them but if not watching its growth might be fun!

That’s it for today, but thank you if you read through this! There might be more later on other days.

1 note

·

View note