#Pope Boniface IX

Photo

A 14th-Century Papal Bull Discovered in Poland

A lead seal found in northwestern Poland has been identified as a rare papal bull from the reign of Pope Boniface IX (1350-1404). It was discovered in 2021 north of a former cemetery in the village of Budzistowo by metal detectorists with the PARSĘTA Exploration and Search Group. Dirt and corrosion made it difficult to identify at first. Specialists in Kraków cleaned and conserved it, revealing the inscription that marks it as the seal of Boniface IX.

Bullae were round seals, usually made of lead, that were hung on silk strings affixed to the parchments of official proclamations and documents. They were legally valid and highly recognizable signatures. Metallurgic analysis found that this one was made of pure lead derived from galenite deposits in Cyprus, Sardinia, Greece and Spain. This composition indicates the bull is original, not a later copy.

The reverse inscription reads: BONI/FATIUS/PP:VIIII. The obverse features the images of Saint Peter and Saint Paul identified by the inscription SPASPE above their heads.

In the 9th century, what is now Budzistowo was founded by Pomeranian tribes as the fortified settlement of Kołobrzeg. The settlement was on the Parsęta River 2.5 miles from its mouth on the Baltic Sea, and was rich in salt, fish, iron ore and arable land. The Polish Piast dynasty conquered the area in the 10th century, and Kołobrzeg grew into a regional center of the trade in salt and salt-cured fish.

It became a seat of a bishopric in 1000, but the area would only become thoroughly Christianized in the 12th century. St Mary’s church was built at that time. It was converted into an abbey in the 13th century when German settlers founded a new town of Kołobrzeg on the Baltic and the former Pomeranian stronghold was renamed Old Kołobrzeg. A monastery for Benedictine nuns was then built in Old Kołobrzeg.

Historians hypothesize that the bull was kept at the Benedictine monastery, based on a reference in the comprehensive history of Kołobrzeg written by the 18th century Pastor Johann Friedrich Wachsen. He recorded that in 1397, Boniface issued a letter of indulgence for the Benedictine nuns. It guaranteed a full indulgence to anyone who visited the local church.

With no relic relating to the monastery surviving to this day, [Dr Robert Dziemba, the head of the Kołobrzeg History Department,] says that if it is proved that this bull is the same one referenced by Wachsen it would be nothing short of “a historical revelation”. […]

Dziemba speculates that this particular papal bull may have been lost in the 16th century.

“After the 1534 congress in Trzebiatów introduced Lutheranism to Pomerania, the document simply lost its value,” he said. “Maybe the bull was thrown out when the duchy took control of the monastery as a result of this congress – but maybe it was lost centuries later. We will probably never know when and why it was discarded.”

The conserved bull has gone on display in the Museum of Arms in Kołobrzeg.

#A 14th-Century Papal Bull Discovered in Poland#Pope Boniface IX#lead seal#metal detecting#archeology#archeolgst#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#medieval history#middle ages#dark ages

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

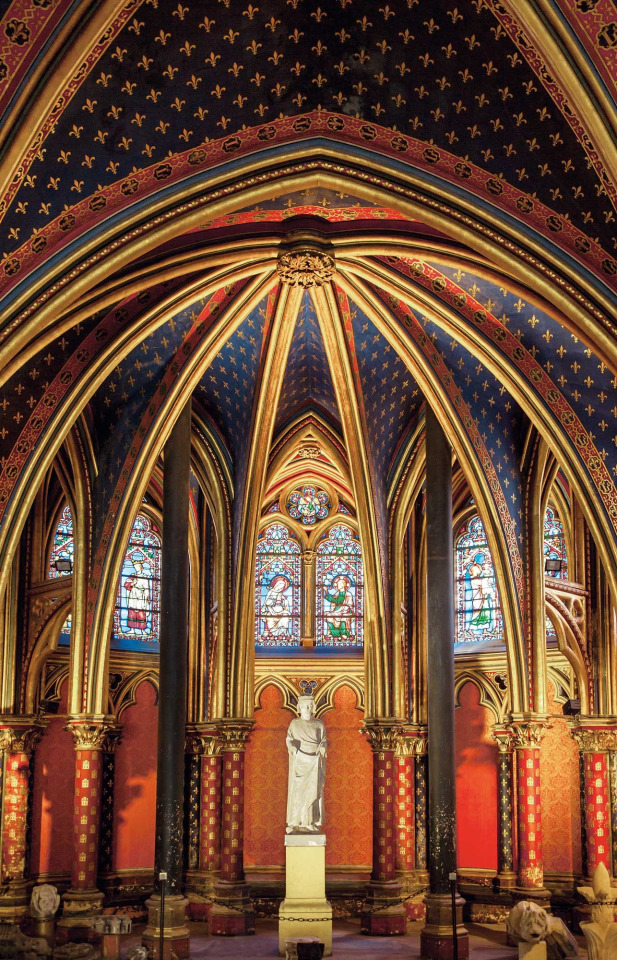

Sainte-Chapelle, the jewel of the Gothic.

Louis IX of France nicknamed the Saint, son of Blanca de Castilla (in turn daughter of Alfonso VIII and Eleanor de Plantagenet) and Louis VIII, has been considered the ideal of the medieval Christian monarch, a very devout king who dedicated his life to prayer, charity and asceticism... in addition to being the last European king to participate in the last two crusades: the Seventh between 1248 and 1254 and the Eighth in 1270, he took Saint Louis to Tunis and there he would die of the plague at the age of 56 and 40 of reign. In 1297 he will be canonized by Pope Boniface VIII.

His devotion and religiosity led him to acquire numerous relics and among them the coveted crown of thorns of Christ. Brought to France from Constantinople, Louis IX decided to organize a sacred place to keep and protect the holy collection. Thus in 1242 the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle would begin, which was consecrated in 1248. Little is known about the authorship of the chapel, it has been attributed to Pierre de Montreuil, master of the radiant Gothic and main architect of the reign of Saint Louis.

The enclosure was conceived as a reliquary or jewelry box where to deposit the precious and holy relics of the Passion of Christ. The chapel is 36 m long, 17 m wide and over 42 m high.

Its walls covered with precious stained glass windows, 15 in total, have representations, among other themes, of the Old Testament as well as the transfer of the crown of thorns to Paris.

These large openings filter the light, causing it to break down into different colors, symbolizing divine power and turning the place into a sacred and spiritual space. It is a large glass urn whose slender ribbed vaults, 20 m high, rise as if bringing us closer to God. In 1630 it went up in flames, a great fire destroyed it to a large extent and during the French Revolution its relics were stolen and many destroyed by the revolutionaries. Some were saved and are now kept in the treasury of Notre Dame Cathedral. In the S. XIX was the object of an extraordinary restoration, but preserving the spirit, fidelity and medieval beauty that it had in its origin.

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Christian History

Today is Monday, September 18th, 2023. It is the 261st day of the year (262nd in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar; 104 days remain until the end of the year.

1519: Death of John Colet, English scholar, Catholic reformer, and friend of Erasmus.

1634: Anne Hutchinson (pictured above) arrives from England to Boston, Massachusetts, where she will rouse controversy and eventually be banished.

1639: Connecticut observes its first annual thanksgiving day as a colony, following heated debate whether or not setting aside a specific day will prompt people to neglect thanking God on other days.

1860: Pope Pius IX’s army, attempting to defend the papal states from takeover by secular Italian forces, suffers defeat at Castelfidardo. The pope loses lands the papacy has mismanaged for centuries.

1884: Death of Jerry McAuley, founder of New York’s Water Street Mission, a pioneer among American rescue missions.

1895: Booker T. Washington delivers his “Atlanta Compromise” address.

1905: Death of Scottish clergyman George MacDonald who wrote novels to support himself. MacDonald’s writings will capture C. S. Lewis’s imagination, convincing him that true Christianity is not uninteresting.

1950: Bishop Makarios is elected the Orthodox Archbishop and Ethnarch of Cyprus. He will quickly move to the forefront of efforts to end British rule in Cyprus and eventually will be exiled by the British government. In 1959, he will negotiate a compromise agreement for an independent Cypriot republic and will be elected the first president of the Republic of Cyprus. However his situation will prove so difficult that the Greeks will attempt to assassinate him and Turkey will eventually invade the island (in 1974), seizing 40% of its territory.

1964: Congolese rebels ransack a missionary hospital at Wasolo. They murder two of the Congolese nurses—Constant Kokembe and Boniface Bomba—and take missionary doctor Paul Carlson hostage.

1975: For the first time in Chile’s history, its annual Te Deum prayer service that commemorates national independence, is led not by the Roman Catholic Church but by the Methodist Pentecostal Church.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (July 23)

Today, July 23, the Church celebrates the feast day of St. Bridget of Sweden.

Bridget received visions of Christ’s suffering many times throughout her life and went on to found the Order of the Most Holy Savior.

Daughter of Birger Persson, the governor and provincial judge of Uppland, and of Ingeborg Bengtsdotter, Bridget was born in Sweden in 1303.

From the time she was a child, she was greatly devoted to the passion of Jesus.

When she was only ten, it is recorded that she had a vision of Jesus on the cross and heard him say, “Look at me, my daughter."

"Who has treated you like this?" cried little Bridget.

Jesus answered, "Those who despise me and refuse my love for them.”

From that moment on, Bridget tried to stop people from offending Jesus.

When she was 14, Bridget married an 18-year old man named Ulf. Like Bridget, Ulf had set his heart on serving God.

They had eight children, including St. Catherine of Sweden.

Bridget and Ulf also served the Swedish court. Bridget was the queen's personal maid.

Bridget tried to help King Magnus and Queen Blanche lead better lives, however, for the most part, they did not listen to her.

All her life, Bridget had marvelous visions and received special messages from God.

In obedience to them, she visited many rulers and important people in the Church. She explained humbly what God expected of them.

After her husband died, Bridget put away her rich clothes and lived as a poor nun.

Later, in 1346, she began the Order of the Most Holy Savior, also known as Bridgettines.

She still kept up her own busy life, traveling about doing good everywhere she went.

And through all this activity, Jesus continued to reveal many secrets to her, which she received without the least bit of pride.

Shortly before she died, the saint went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. At the shrines there, she had visions of what Jesus had said and done in each place.

All revelations of St. Bridget on the sufferings of Jesus were published after her death.

St. Bridget died in Rome on 23 July 1373. She was proclaimed a saint by Pope Boniface IX on 7 October 1391.

On 1 October 1999, Pope John Paul II named Saint Bridget a patron saint of Europe.

Her feast day is celebrated on July 23, the day of her death.

"True wisdom, then, consists in works, not in great talents, which the world admires; for the wise in the world's estimation . . . are the foolish who set at naught the will of God, and know not how to control their passions."

— Saint Bridget of Sweden

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On November 8th 1308 Scholar and philosopher John Duns Scotus died.

Described as a humble man, John Duns Scotus has been one of the most influential Franciscans through the centuries. Born at Duns in the Scottish Borders, John was descended from a wealthy farming family. In later years, he was identified as John Duns Scotus to indicate the land of his birth; Scotia being the Latin name for our country.

John received the habit of the Friars Minor at Dumfries, where his uncle Elias Duns was superior. After he took vows he studied at Oxford and Paris and was fully ordained in 1291. More studies in Paris followed until 1297, when he returned to lecture at Oxford and Cambridge. Four years later, he returned to Paris to teach and complete the requirements for the doctorate.

In an age when many people adopted whole systems of thought without qualification, John pointed out the richness of the Augustinian-Franciscan tradition, appreciated the wisdom of Aquinas, Aristotle, and the Muslim philosophers—and still managed to be an independent thinker. That quality was proven in 1303, when King Philip the Fair tried to enlist the University of Paris on his side in a dispute with Pope Boniface VIII. John Duns Scotus dissented, and was given three days to leave France.

During his era, some philosophers held that people are basically determined by forces outside themselves. Free will is an illusion, they argued. An ever-practical man, Scotus said that if he started beating someone who denied free will, the person would immediately tell him to stop. But if Scotus didn’t really have a free will, how could he stop?

After a short stay in Oxford, Scotus returned to Paris, where he received the doctorate in 1305. He continued teaching there and in 1307 so ably defended the Immaculate Conception of Mary that the university officially adopted his position. That same year the minister general assigned him to the Franciscan school in Cologne where he died on this day in 1308. He is buried in the Franciscan church near the famous Cologne cathedral.

His work was still talked about centuries later In 1854, drawing on the work of John Duns Scotus, Pope Pius IX solemnly defined the Immaculate Conception of Mary. John Duns Scotus, the “Subtle Doctor,” was beatified in 1993, this is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven.

You can find a lot more on the man here https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/life-of-blessed-john-duns-scotus-5809

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

tell them about the three popes who all excommunicated each other bc that one's actually funny and not horrifying

ik, centre of attention at another dance at diavolo’s castle: so there was urban vi in rome, who people didn’t like so they appointed a new guy called clement vii in avignon, and they declared each other excommunicated - basically they kicked each other out of the church - and then they both died

[demon crowd around her titters]

ik: so they got replaced by boniface ix and benedict xiii, and boniface was replaced by innocent vii and then gregory xii. so there was benedict and gregory, and a council was employed to just pick one pope from the two they had. but instead they picked a third guy called alexander v

[scattered chuckles from demon crowd]

ik: alexander got succeeded by john xxiii, who convened a council that had him and gregory resign, and benedict got excommunicated for not stepping down, and then the council elected a new guy called martin v. also did you know that these days the pope goes around in a car called the popemobile?

[demon crowd erupts into uproarious laughter like an audience at a pantomime]

#i've looked this up before and some websites say that john benedict and gregory excommunicated each other#but most say that john and greg resigned and then just benedict was excommunicated#but since urban and clement excommunicated each other (at least i assume that's correct) that's still three in total right??#i'm sorry this response isn't very funny but i didn't know what else to do with it#i just really liked the idea of a crowd of giant demons losing their shit over the word 'popemobile'#answering asks#anon asks

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ferdinand of Arragon

It may surprise some readers to treat the thirteenth century as the virtual close of the Middle Ages, an epoch which is usually placed in the latter half of the fifteenth century, in the age of Louis xi., Henry VII., and Ferdinand of Arragon. But the true spirit of Feudalism, the living soul of Catholicism, which together make up the compound type of society we call mediaeval, were, in point of fact, waning all through the thirteenth century. The hurly-burly of the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth centuries was merely one long and cruel death agony. Nay, the inner soul of Catholic Feudalism quite ended in the first generation of the thirteenth century — with St. Dominic, St. Francis, Innocent in., Philip Augustus, and Otto iv., Stephen Langton, and William, Earl Mareschal.

The truly characteristic period of mediaeval- ism is in the twelfth, rather than the thirteenth, century, the period covered by the first three Crusades from 1094, the date of the Council of Clermont, to 1192, when Coeur- de-Lion withdrew from the Holy Land. Or, if we put it a little wider in limits, we may date true mediaevalism from the rise of Hildebrand, about 1070, to the death of Innocent HI. in 1216, or just about a century and a half. St. Louis himself, as we read Joinville’s Memoirs, seems to us a man belated, born too late, and almost an anachronism in the second half of the thirteenth century sofia city tour.

We know that in the slow evolution of society the social brilliancy of a movement is seldom visible, and is almost never ripe for poetic and artistic idealisation until the energy of the movement itself is waning, or even it may be, is demonstrably spent. Shakespeare prolonged the Renascence of the fifteenth century, the Renascence of Leonardo and Raphael, into the seventeenth century, when Puritanism was in full career; and Shakespeare — it is deeply significant — died on the day when Oliver Cromwell entered college at Cambridge. And so, when Dante, in his Vision of 1300, saw the heights and the depths of Catholic Feudalism, he was looking back over great movements which were mighty forces a hundred years earlier. Just so, though the thirteenth century contained within its bosom the plainest proofs that the mediaeval world was ending, the flower, the brilliancy, the variety, the poetry, the soul of the mediaeval world, were never seen in so rich a glow as in the thirteenth century, its last great effort.

Thirteenth century as a whole

In a brief review of each of the dominant movements which give so profound a character to the thirteenth century as a whole, one begins naturally with the central movement of all — the Church. The thirteenth century was the era of the culmination, the over-straining, and then the shameful defeat of the claim made by the Church of Rome to a moral and spiritual autocracy in Christendom. There are at least five Popes in that one hundred years — Innocent HI., Gregory ix., Innocent iv., Gregory x., and Boniface vm.—whose characters impress us with a sense of power or of astounding desire of power, whose lives are romances and dreams, and whose careers are amongst the most instructive in history. He who would understand the Middle Ages must study from beginning to end the long and crowded Pontificate of Innocent HI. In genius, in commanding nature, in intensity of character, in universal energy, in aspiring designs, Innocent HI. has few rivals in the fourteenth centuries of the Roman Pontiffs, and few superiors in any age on any throne in the world.

His eighteen years of rule, from 1198 to 1216, were one long effort, for the moment successful, and in part deserving success, to enforce on the kings and peoples of Europe a higher morality, respect for the spiritual mission of the Church, and a sense of their common civilisation. We feel that he is truly a great man with a noble cause, when the Pope forces Philip Augustus to take back the wife he had so insolently cast off, when the Pope forces John to respect the rights of all his subjects, laymen or churchmen, when the Pope gives to England the best of her Primates, Stephen Langton, the principal author of our Great Charter, when the Pope accepts the potent enthusiasm of the New Friars and sends them forth on their mission of revivalism.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers Saint William of Perth (died c. 1201 AD), also known as Saint William of Rochester.

Ora pro nobis,

William was a Scottish saint, born in Perth, Scotland, in the 12th c. AD, who was martyred in England while on pilgrimage. He is the patron saint of adopted children.

Life

Practically most that is known of William comes from the Nova Legenda Anglie, and that is little. He was born in Perth, at that time one of the principal towns of Scotland. In youth, he had been somewhat wild, but on reaching manhood he devoted himself wholly to the service of God. A baker by trade (some sources say he was a fisherman), he was accustomed to setting aside every tenth loaf for the poor.

He went to Mass daily, and one morning, before it was light, found on the threshold of the church an abandoned child, whom he adopted and to whom he taught his trade. Later he took a vow to visit the Holy Places, and, having received the consecrated wallet and staff as a Palmer, set out with his adopted son, whose name is given as "Cockermay Doucri", which is said to be Scots for "David the Foundling". They stayed three days at Rochester, and purposed to proceed next day to Canterbury (and perhaps thence to Jerusalem), but instead David wilfully misled his benefactor on a short-cut and, with robbery in view, felled him with a blow on the head and cut his throat.

The body was discovered by a mad woman, who plaited a garland of honeysuckle and placed it first on the head of the corpse and then her own, whereupon the madness left her. On learning her tale the monks of Rochester carried the body to the cathedral and there buried it. He was honoured as a martyr because he was on a pilgrimage to holy places. As a result of the miracle involving the madwoman as well as other miracles wrought at his intercession after death, he was acclaimed a saint by the people.

Veneration

In 1256 AD, Lawrence of St Martin, Bishop of Rochester, obtained the canonisation of William from Pope Alexander IV. A beginning was at once made with his shrine, which was situated first in the crypt, then in the northeast transept, and attracted crowds of pilgrims. At the same time a small chapel was built at the place of the murder, which was thereafter called Palmersdene. Remains of this chapel are still to be seen near the site of the old St William's Hospital, on the road leading by Horsted Farm to Maidstone.

The shrine of St William of Perth became a place of pilgrimage second only to Canterbury's shrine of Saint Thomas Becket, bringing many thousands of medieval pilgrims to the cathedral. Their footsteps wore down the original stone Pilgrim Steps, and nowadays they are covered with wooden steps.[4] Margaret Darcy, of Essex, in her will, expressed the wish that her servant, Margaret Staunford, should go on a pilgrimage to "Seint Willyam of Rowchester".

On 18 and 19 February 1300 AD, King Edward I gave two donations of seven shillings to the shrine. Offerings at the shrine were also recorded for Queen Philippa (1352). On 29 November 1399, Pope Boniface IX granted an indulgence to those who visited and gave alms to the shrine on certain specified days. The local people continued to make bequests through the 15th and 16th centuries.

The coat of arms of the Bishop of Rochester consists of Saint Andrew's cross with a scallop shell in its centre, which is said to represent William; Andrew being the patron saint of Scotland and scallops being the symbol of pilgrimage. St. William is represented in a wall-painting, which was discovered in 1883 in Frindsbury church, near Rochester, which is supposed to have been painted about 1256–1266.

Almighty and everlasting God, who kindled the flame of your love in the heart of your holy martyr Willian. Grant to us, your humble servants, a like faith and power of love, that we who rejoice in her triumph may profit by her example; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#jesus#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#god#salvation#peace#martyrs#faith#pilgrim#pilgrimage

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.20 (before 1920)

1303 – The Sapienza University of Rome is instituted by a bull of Pope Boniface VIII.

1653 – Oliver Cromwell dissolves England's Rump Parliament.

1657 – English Admiral Robert Blake destroys a Spanish silver fleet, under heavy fire from the shore, at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

1657 – Freedom of religion is granted to the Jews of New Amsterdam (later New York City).

1752 – Start of Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War, a new phase in the Burmese Civil War (1740–57).

1770 – The Georgian king, Erekle II, abandoned by his Russian ally Count Totleben, wins a victory over Ottoman forces at Aspindza.

1775 – American Revolutionary War: The Siege of Boston begins, following the battles at Lexington and Concord.

1789 – George Washington arrives at Grays Ferry, Philadelphia, while en route to Manhattan for his inauguration.

1792 – France declares war against the "King of Hungary and Bohemia", the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars.

1800 – The Septinsular Republic is established.

1809 – Two Austrian army corps in Bavaria are defeated by a First French Empire army led by Napoleon at the Battle of Abensberg on the second day of a four-day campaign that ended in a French victory.

1828 – René Caillié becomes the second non-Muslim to enter Timbuktu, following Major Gordon Laing. He would also be the first to return alive.

1836 – U.S. Congress passes an act creating the Wisconsin Territory.

1859 – Daniel E. Sickles, a New York Congressman, is acquitted of the murder of Philip Barton Key on grounds of temporary insanity. The case marked the first successful use of the "temporary insanity" legal defense.

1861 – American Civil War: Robert E. Lee resigns his commission in the United States Army in order to command the forces of the state of Virginia.

1861 – Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, attempting to display the value of balloons, makes record journey, flying 900 miles from Cincinnati to South Carolina.

1862 – Louis Pasteur and Claude Bernard complete the experiment disproving the theory of spontaneous generation.

1865 – Astronomer Angelo Secchi demonstrates the Secchi disk, which measures water clarity, aboard Pope Pius IX's yacht, the L'Immaculata Concezion.

1876 – The April Uprising begins. Its suppression shocks European opinion, and Bulgarian independence becomes a condition for ending the Russo-Turkish War.

1884 – Pope Leo XIII publishes the encyclical Humanum genus, condemning Freemasonry.

1898 – U.S. President William McKinley signs a joint resolution to Congress for declaration of war against Spain, beginning the Spanish–American War.

1902 – Pierre and Marie Curie refine radium chloride.

1908 – Opening day of competition in the New South Wales Rugby League.

1914 – Nineteen men, women, and children participating in a strike are killed in the Ludlow Massacre during the Colorado Coalfield War.

1918 – Manfred von Richthofen, a.k.a. The Red Baron, shoots down his 79th and 80th victims, his final victories before his death the following day.

0 notes

Text

“It became common for universities to bring their grievances to the pope in Rome.1 On several occasions, the pope even intervened to force university authorities to pay professors their salaries; Popes Boniface VIII, Clement V, Clement VI, and Gregory IX all had to take such measures.2 Little wonder, then, that one historian has declared that the universities' "most consistent and greatest protector was the Pope of Rome. He it was who granted, increased, and protected their privileged status in a world of often conflicting jurisdictions.3”

- Thomas E. Woods Jr., Ph.D., “The Church and the University,” How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization

1 & 2. Universities" Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913. The universticsthat lacked charters had come into being spontaneously ex consuetudine.

3. Lowrie J. Daly, The Medieval University, 1200-1400 (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961), 202.

0 notes

Text

All Saints’ Church is located in Wittenberg, Germany. The first chapel on this site was built in 1340 and consecrated in 1346. The church was considered Wittenberg’s main church by Pope Boniface IX in 1400. There was an old Ascanian Castle on the site, but it was demolished to make room for a new Gothic structure in 1490-1511. The church, built into the castle, is a long basilica with an eastern apse encompassing the north wing of the three-winged complex. The tower of the church stands over the fortress-like estate. The church served as residences for the dukes of Saxe-Wittenberg as well as serving as the University of Wittenberg. The chapel and university developed into an important academic and worship center. All Saints’ Church houses the preserved tombs of reformers Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, as well as the dukes of Saxe-Wittenberg. All Saints’ Church is world-famous for being the site where Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the main door on October 31, 1517. Luther’s theses attacked papal abuses and the sale of indulgences. In 1520, Pope Leo X declared Luther’s theses to be heretical and he was excommunicated. In 1883, the church was restored in the Neo-Gothic style. A Lutheran Church was established on the site in 1949. In 1983, a series of 12 stained glass windows were installed, each honoring a student of Luther. Today, the structure still serves as a place of worship. It also houses the town’s historical archives, the Riemer Museum, and a youth hostel.

#castles#churches#all saints church#andrea wittenberg#germany#castle church#reformation memorial church

0 notes

Text

15 Controversial Popes in History:

1. Pope Stephen VI (r. 896-897) - He was responsible for the infamous Cadaver Synod, in which he exhumed the corpse of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, put it on trial, found it guilty, and had it mutilated and thrown into the Tiber River.

2. Pope John XII (r. 955-964) - He was known for his scandalous behavior, including gambling, drinking, and engaging in sexual relations with women and men, as well as his political intrigues and corruption.

3. Pope Benedict IX (r. 1032-1044; 1045; 1047-1048) - He was known for his immoral behavior and corruption, including selling the papacy for money and engaging in various scandals and crimes.

4. Pope Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1303) - He was notorious for his conflicts with King Philip IV of France, including the Papal Bull Unam Sanctam, which asserted the Pope's supremacy over secular rulers.

5. Pope Alexander VI (r. 1492-1503) - He was known for his corrupt and scandalous behavior, including his numerous mistresses and children, as well as his involvement in the Spanish Inquisition and various political intrigues.

6. Pope Julius III (r. 1550-1555) - He was known for his scandalous behavior, including his sexual relationships with men and his nepotism in appointing family members to high positions in the Church.

7. Pope Urban VI (r. 1378-1389) - He was known for his aggressive and erratic behavior, including his mistreatment of cardinals and his persecution of those who opposed him.

8. Pope Leo X (r. 1513-1521) - He was known for his lavish spending and patronage of the arts, which contributed to the financial problems of the Catholic Church and helped to spark the Protestant Reformation.

9. Pope Clement VII (r. 1523-1534) - He was criticized for his indecisiveness and political maneuvering, including his involvement in the Sack of Rome and his failure to respond effectively to the Protestant Reformation.

10. Pope Paul IV (r. 1555-1559) - He was known for his authoritarian and intolerant behavior, including his persecution of Jews and his efforts to suppress Protestantism.

11. Pope Pius IX (r. 1846-1878) - He was criticized for his opposition to modernity and his rejection of liberal ideas, including his opposition to democracy, freedom of speech, and religious tolerance.

12. Pope Pius XII (r. 1939-1958) - He was criticized for his perceived silence during the Holocaust and his controversial actions during World War II, including his role in the ratlines that helped Nazis escape to South America.

13. Pope John Paul II (r. 1978-2005) - He was criticized for his opposition to contraception, abortion, and homosexuality, as well as his handling of the sexual abuse scandals in the Catholic Church.

14. Pope Benedict XVI (r. 2005-2013) - He was criticized for his conservative views on social issues, including his opposition to contraception, homosexuality, and the ordination of women, as well as his handling of the sexual abuse scandals in the Catholic Church.

15. Pope Francis (r. 2013-present) - He has been criticized by some for his perceived liberal views on social issues, including his support for environmentalism, social justice, and LGBT rights.

It is important to note that these criticisms are not universal, and many of these Popes have also been praised for their positive contributions to the Catholic Church and the world.

0 notes

Text

i think it's so funny when people say pope francis is the worst pope ever. look at pope benedict ix. look at pope boniface viii. at least pope francis has a prog rock album and his middle name is mario as opposed to possibly killing someone/being pope three separate times and also horrible as pope. at least he isn't leading the crusades! doesn't make him good but also. there is no way he could be the worst one

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Catholic Church in the Middle Ages

It is not necessary to enter on one of the most difficult problems in history to decide how far the development and organisation of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages were worth the price that civilisation paid in moral, intellectual, and in material loss. Still less can we attempt to justify such Crusades as that which established the Latin kingdom in Constantinople, or the Crusade to crush the revolt of the Albigensian heretics, and all the enormous assumptions of Innocent in things temporal and things spiritual. But before we decide that in the thirteenth century civilisation would have been the gainer, if there had been no central Church at all, let us count up all the great brains of the time, with Aquinas and Dante at their head, all the great statesmen, St. Louis, Blanche of Castile, in France; Simon de Montfort and Edward i., in England, and Ferdinand HI., in Spain; Frederick n. and Rudolph of Hapsburg, in the Empire,—who might in affairs of state often oppose Churchmen, but who felt that society itself reposed on a well-ordered Church.

Temporary expedient

If the great attempt failed in the hands of Innocent III, surely one of the finest brains and noblest natures that Rome ever sent forth — and fail it did on the whole, except as a temporary expedient — it could not succeed with smaller men, when every generation made the conditions of success more hopeless. The superhuman pride of Gregory IX., the venerable pontiff who for fourteen years defied the whole strength of the Emperor Frederick IL, seems to us to-day sofia city tour, in spite of his lofty spirit, but to parody that of Hildebrand, of Alexander HI., and Innocent HI. And when we come to Innocent iv. (1243-1264), the disturber of the peace of the Empire, he is almost a forecast of Boniface. And Boniface himself (1294-1303), though his words were more haughty than those of the mightiest of his predecessors, though insatiable ambition and audacious intrigue gave him some moments of triumph, ended after nine years of desperate struggle in what the poet calls ‘the mockery, the vinegar, the gall of a new crucifixion of the Vicar of Christ.’ Read Dante, and see all that a great spirit in the Middle Ages could still hope from the Church and its chiefs — all that made such dreams a mockery and a delusion.

When Dante wrote, the Popes were already settled at Avignon and the Church had entered upon one of its worst eras. And as we follow his scathing indignation, in the nineteenth canto of the Inferno, or in the twenty-seventh of the Pamdiso, we feel how utterly the vision of Peter had failed to be realised on earth.

But for one hundred years before, all through the thirteenth century, the writing on the wall may now be read, in letters of fire. When Saladin forced the allied kings of Europe to abandon the conquest of the Holy Sepulchre, and Lion-hearted Richard turned back in despair (1192), the Crusades, as military movements, ended. The later Crusades of the thirteenth century were splendid acts of folly, of anachronism, even crime. They were ‘magnificent, but not war’ — in any rational sense. It was Europe that had to be protected against the Moslem — not Asia or Africa that was to be conquered. All through the thirteenth century European civilisation was enjoying the vast material and intellectual results of the Crusades of the twelfth century. But to sail for Jerusalem, Egypt, or Tunis, had then become, as the wise Joinville told St. Louis, a cruel neglect of duty at home.

It was not merely in the exhaustion of the Crusading zeal that the waning of the Catholic fervour was shown. In the twelfth century there had been learned or ingenious heretics. But the mark of the thirteenth century is the rise of heretic sects, schismatic churches, religious reformations, spreading deep down amongst the roots of the people. We have the three distinct religious movements which began to sap the orthodox citadel, and which afterwards took such vast proportions — Puritanism, Mysticism, Scepticism. All of them take form in the thirteenth century — Waldenses, Albigenses, Petrobussians, Poor Men, Anti-Ritualists, Anti-Sacerdotalists, Manichaeans, Gospel Christians, Quietists, Flagellants, Pastoureaux, fanatics of all orders. All through the thirteenth century we have an intense ferment of the religious exaltation, culminating in the orthodox mysticism, the rivalries, the missions, the revivalism, of the new allies of the Church, the Franciscans and Dominicans, the Friars or Mendicant Orders.

0 notes

Photo

Catholic Church in the Middle Ages

It is not necessary to enter on one of the most difficult problems in history to decide how far the development and organisation of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages were worth the price that civilisation paid in moral, intellectual, and in material loss. Still less can we attempt to justify such Crusades as that which established the Latin kingdom in Constantinople, or the Crusade to crush the revolt of the Albigensian heretics, and all the enormous assumptions of Innocent in things temporal and things spiritual. But before we decide that in the thirteenth century civilisation would have been the gainer, if there had been no central Church at all, let us count up all the great brains of the time, with Aquinas and Dante at their head, all the great statesmen, St. Louis, Blanche of Castile, in France; Simon de Montfort and Edward i., in England, and Ferdinand HI., in Spain; Frederick n. and Rudolph of Hapsburg, in the Empire,—who might in affairs of state often oppose Churchmen, but who felt that society itself reposed on a well-ordered Church.

Temporary expedient

If the great attempt failed in the hands of Innocent III, surely one of the finest brains and noblest natures that Rome ever sent forth — and fail it did on the whole, except as a temporary expedient — it could not succeed with smaller men, when every generation made the conditions of success more hopeless. The superhuman pride of Gregory IX., the venerable pontiff who for fourteen years defied the whole strength of the Emperor Frederick IL, seems to us to-day sofia city tour, in spite of his lofty spirit, but to parody that of Hildebrand, of Alexander HI., and Innocent HI. And when we come to Innocent iv. (1243-1264), the disturber of the peace of the Empire, he is almost a forecast of Boniface. And Boniface himself (1294-1303), though his words were more haughty than those of the mightiest of his predecessors, though insatiable ambition and audacious intrigue gave him some moments of triumph, ended after nine years of desperate struggle in what the poet calls ‘the mockery, the vinegar, the gall of a new crucifixion of the Vicar of Christ.’ Read Dante, and see all that a great spirit in the Middle Ages could still hope from the Church and its chiefs — all that made such dreams a mockery and a delusion.

When Dante wrote, the Popes were already settled at Avignon and the Church had entered upon one of its worst eras. And as we follow his scathing indignation, in the nineteenth canto of the Inferno, or in the twenty-seventh of the Pamdiso, we feel how utterly the vision of Peter had failed to be realised on earth.

But for one hundred years before, all through the thirteenth century, the writing on the wall may now be read, in letters of fire. When Saladin forced the allied kings of Europe to abandon the conquest of the Holy Sepulchre, and Lion-hearted Richard turned back in despair (1192), the Crusades, as military movements, ended. The later Crusades of the thirteenth century were splendid acts of folly, of anachronism, even crime. They were ‘magnificent, but not war’ — in any rational sense. It was Europe that had to be protected against the Moslem — not Asia or Africa that was to be conquered. All through the thirteenth century European civilisation was enjoying the vast material and intellectual results of the Crusades of the twelfth century. But to sail for Jerusalem, Egypt, or Tunis, had then become, as the wise Joinville told St. Louis, a cruel neglect of duty at home.

It was not merely in the exhaustion of the Crusading zeal that the waning of the Catholic fervour was shown. In the twelfth century there had been learned or ingenious heretics. But the mark of the thirteenth century is the rise of heretic sects, schismatic churches, religious reformations, spreading deep down amongst the roots of the people. We have the three distinct religious movements which began to sap the orthodox citadel, and which afterwards took such vast proportions — Puritanism, Mysticism, Scepticism. All of them take form in the thirteenth century — Waldenses, Albigenses, Petrobussians, Poor Men, Anti-Ritualists, Anti-Sacerdotalists, Manichaeans, Gospel Christians, Quietists, Flagellants, Pastoureaux, fanatics of all orders. All through the thirteenth century we have an intense ferment of the religious exaltation, culminating in the orthodox mysticism, the rivalries, the missions, the revivalism, of the new allies of the Church, the Franciscans and Dominicans, the Friars or Mendicant Orders.

0 notes

Photo

Special study of the thirteenth century

He who would understand the Middle Ages must make a special study of the thirteenth century — one of the landmarks between the ancient and the modern world, one of the most pregnant, most organic, most memorable, in the annals of mankind. It is an epoch (perhaps the last of the centuries of which this can be said) crowded with names illustrious in action, in thought, in art, in religion equally; which is big with those problems, intellectual, social, political, and spiritual that six succeeding centuries have in vain toiled to solve.

A ‘ Century ’ is, of course, a purely arbitrary limit of time. But for practical purposes we can only reckon by years and groups of years. And, as in the biography of a man, we speak of the happy years of a life, or a decade of great activity, so it is convenient to speak of a brilliant ‘ century,’ if we attach no mysterious value to our artificial measure of time. It happens, however, that the thirteenth century not only has a really distinctive character of its own, but that, near to its beginning and to its close, very typical events occurred. In 1198 took place the election of Innocent in tours sofia, the most successful, perhaps the most truly representative name, of all the mediaeval popes. In the year preceding (1197) we may see the Empire visibly beginning to change its spirit with the death of Henry vi., the ferocious son of Barbarossa. In the year following

1 Fortnightly Revieiv, vol. 50, N.s. September 1891. (1199) died Richard Lion-heart, the last of the Anglo- French sovereigns, and, we may say, the last of the genuine Crusader kings, to be succeeded by his brother John, who was happily forced to become an English king, and to found the Constitution of England by signing the Great Charter.

And at the end of the century, its last year (1300) is the date of the ominous ‘Jubilee’ of the Papacy — the year in which Dante places his great poem—a year which is one of the most convenient points in the memoria technical of modern history. Three years later died Boniface VIII., after the tremendous humiliation which marked the manifest decadence of the Papacy; eight years later began the ‘ Babylonish Captivity,’ the seventy years’ exile of the Papacy at Avignon; then came the ruin of the Templars throughout Europe, and all the tragedies and convulsions which mark the reigns of Philip the Fair in France, Edward I in England, and the confusion that overtook the Empire on the death of Henry of Luxembourg, that last hope of imperial ambition. Thus, taking the period between the election of Innocent 111., in 1198, and the removal of the Papacy to Avignon, in 1308, we find a very definite character in the thirteenth century. It would, of course, be necessary to fix the view on Europe as a whole, or rather on Latin Christendom, to obtain any unity of conception; and, obviously, the development and decay of the Church must be the central point, for this is at once the most general and the important element in the common life of Christendom.

Reformation in England and in Germany

Within the limits of the thirteenth century, so understood, a series of striking events and great names is crowded — the growth, culmination, extravagance, and then the humiliation of the Papal See; the eighteen years’ rule of Innocent HI., the fourteen years of Gregory ix., the twenty- one of Innocent IV.; the short revival of Gregory x.; the ambition, the pride, the degradation, and shame of Boniface VIII. The great experiment to organise Christendom under a single spiritual sovereign had been made by some of the most aspiring natures, and the most consummate politicians who ever wore mitre had been made and failed. When the Popes returned from Avignon to Rome in 1378, after the seventy years of exile from their capital, it was to find the Catholic world rent with schism, a series of anti-popes, heresy, and the seeds of the Reformation in England and in Germany. Thus the secession to Avignon in the opening of the fourteenth century was the beginning of the end of spiritual unity for Latin Christendom.

At the very opening of the thirteenth century, the diversion of the Crusade to the capture of Constantinople in 1204, and all the incidents of that unholy war, prove that, as a moral and spiritual movement, the era of Godfrey and Tancred, of Peter the Hermit and Bernard of Clair- vaux was ended; and though, for a century or two, kings took the Cross, like St. Louis and our Edward I., in the thirteenth century, or, like our Henry V., in the fifteenth century, talked of so doing, the hope of annihilating Islam was gone for ever, and Christendom, for four centuries, had enough to do to protect Europe itself from the Moslem.

And within a few years of this cynical prostitution of the Crusading enthusiasm in the conquest of Byzantium, the Crusading passion broke out in the dreadful persecution of the Albigenses and the Crusade against heresy of Simon de Montfort. And hardly was the unity of Christendom assured by blood and terror, when the spiritual Crusades of Francis and Dominic begin, and the contagious zeal of the Mendicant Friars restored the force of the Church, and gave it a new era of moral and social vitality.

0 notes