#Palantir Technologies

Text

Down but Far From Out: 3 Artificial Intelligence (AI) Stocks to Buy and Hold Forever

Is artificial intelligence (AI) all hype? After a lackluster few weeks for AI stocks, some investors are asking that question — and getting nervous.

This week, three Motley Fool contributors examine Palantir Technologies (NYSE: PLTR), Snowflake (NYSE: SNOW), and Nvidia (NASDAQ: NVDA) to explain why they think these stocks are down from recent highs — but are far from out.

Image source: Getty…

View On WordPress

#artificial intelligence#cloud platform#data cloud#Motley Fool#Nvidia#Palantir stock#Palantir Technologies#Sridhar Ramaswamy

0 notes

Text

Photo-Illustration By TIME

How Tech Giants Turned Ukraine Into An Artificial Intelligence (AI) War Lab

— By Vera Bergengruen | Kyiv, Ukraine | February 8, 2024

Early On The Morning of June 1, 2022, Alex Karp, the CEO of the data-analytics firm Palantir Technologies, crossed the border between Poland and Ukraine on foot, with five colleagues in tow. A pair of beaten-up Toyota Land Cruisers awaited on the other side. Chauffeured by armed guards, they sped down empty highways toward Kyiv, past bombed-out buildings, bridges damaged by artillery, the remnants of burned trucks.

They arrived in the capital before the wartime curfew. The next day, Karp was escorted into the fortified bunker of the presidential palace, becoming the first leader of a major Western company to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky since Russia’s invasion three months earlier. Over a round of espressos, Karp told Zelensky that he was ready to open an office in Kyiv and deploy Palantir’s data and artificial-intelligence software to support Ukraine’s defense. Karp believed they could team up “in ways that allow David to beat a modern-day Goliath.”,

In the stratosphere of top tech CEOs, Karp is an unusual figure. At 56, he is a lanky tai chi aficionado with a cloud of wiry gray curls that gives him the air of an eccentric scientist. He has a Ph.D. in Philosophy from a German University, where he studied under the famous Social Theorist Jürgen Habermas, and a law degree from Stanford, where he became friends with the controversial venture capitalist and Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel. After Palantir became tech’s most secretive unicorn, Karp moved the company to Denver to escape Silicon Valley’s “Monoculture,” though he typically works out of a barn in New Hampshire when he’s not traveling.

The Ukrainians weren’t sure what to think of the man making grandiose promises across the ornate wooden table. But they were familiar with the company’s reputation, recalls Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation, who was in that first meeting. Named after the mystical seeing stones in The Lord of the Rings, Palantir sells the same aura of omniscience. Seeded in part by an investment from the CIA’s venture-capital arm, it built its business providing data-analytics software to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the FBI, the Department of Defense, and a host of foreign-intelligence agencies. “They are the AI arms dealer of the 21st century,” says Jacob Helberg, a national-security expert who serves as an outside-policy adviser to Karp. In Ukraine, Karp tells me, he saw the opportunity to fulfill Palantir’s mission to “defend the West” and to “scare the f-ck out of our enemies.”

TIME Illustration. Palantir Ukraine Time Magazine Cover

Ukraine saw an opportunity too. At first it was driven by desperation, says Fedorov, 33. With the Russians threatening to topple Zelensky’s democratically elected government and occupy the country, Kyiv needed all the help it could get. But soon, government officials realized they had a chance to develop the country’s own tech sector. From European capitals to Silicon Valley, Fedorov and his deputies began marketing the battlefields of Ukraine as laboratories for the latest military technologies. “Our big mission is to make Ukraine the world’s tech R&D lab,” Fedorov says.

The progress has been striking. In the year and a half since Karp’s initial meeting with Zelensky, Palantir has embedded itself in the day-to-day work of a wartime foreign government in an unprecedented way. More than half a dozen Ukrainian agencies, including its Ministries of Defense, Economy, and Education, are using the company’s products. Palantir’s software, which uses AI to analyze satellite imagery, open-source data, drone footage, and reports from the ground to present commanders with military options, is “responsible for most of the targeting in Ukraine,” according to Karp. Ukrainian officials told me they are using the company’s data analytics for projects that go far beyond battlefield intelligence, including collecting evidence of war crimes, clearing land mines, resettling displaced refugees, and rooting out corruption. Palantir was so keen to showcase its capabilities that it provided them to Ukraine free of charge.

It is far from the only tech company assisting the Ukrainian war effort. Giants like Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Starlink have worked to protect Ukraine from Russian cyberattacks, migrate critical government data to the cloud, and keep the country connected, committing hundreds of millions of dollars to the nation’s defense. The controversial U.S. facial-recognition company Clearview AI has provided its tools to more than 1,500 Ukrainian officials, who have used it to identify more than 230,000 Russians on their soil as well as Ukrainian collaborators. Smaller American and European companies, many focused on autonomous drones, have set up shop in Kyiv too, leading young Ukrainians to dub some of the city’s crowded co-working spaces “Mil-Tech Valley."

War has always driven innovation, from the crossbow to the internet, and in the modern era private industry has made key contributions to breakthroughs like the atom bomb. But the collaboration between foreign tech companies and the Ukrainian armed forces, who say they have a software engineer deployed with each battalion, is driving a new kind of experimentation in military AI. The result is an acceleration of “the most significant fundamental change in the character of war ever recorded in history,” General Mark Milley, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters in Washington last year.

It Can Be Hard To See That From Afar. By all accounts, the war in Ukraine has settled into a stalemate, with both sides hammering away with 20th century weapons like artillery and tanks. Some view the claims of high-tech breakthroughs with skepticism, arguing that the grinding war of attrition is little affected by the deployment of AI tools. But Ukraine and its private-sector allies say they are playing a longer game: creating a war lab for the future. Ukraine “is the best test ground for all the newest tech,” Fedorov says, “because here you can test them in real-life conditions.” Says Karp: “There are things that we can do on the battlefield that we could not do in a domestic context.”

If the future of warfare is being beta tested on the ground in Ukraine, the results will have global ramifications. In conflicts waged with software and AI, where more military decisions are likely to be handed off to algorithms, tech companies stand to wield outsize power as independent actors. The ones willing to move fast and flout legal, ethical, or regulatory norms could make the biggest breakthroughs. National-security officials and experts warn these new tools risk falling into the hands of adversaries. “The prospects for proliferation are crazy,” says Rita Konaev of Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. “Most companies operating in Ukraine right now say they align with U.S. national-security goals—but what happens when they don’t? What happens the day after?”

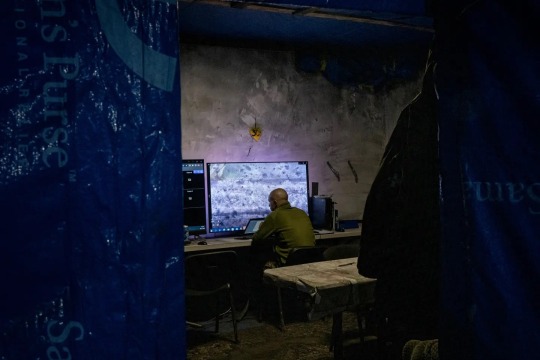

A Ukrainian military analyst reviews videos obtained by drone operators near Bakhmut in January 2023. Nicole Tung—The New York Times/Redux

In the months since Karp’s cloak-and-dagger first meeting with Zelensky, Palantir brass have fallen into a familiar routine on their frequent trips into Ukraine. In October, I met a London-based Palantir employee at the airport in Krakow, Poland. We were picked up in two armored cars, handed emergency medical kits “just in case,” and driven to the border with Ukraine. Gone was what one executive described to me as the “Kalashnikov-between-the-knees vibe.” We zipped through the border checkpoint, where young Ukrainian recruits dozed in the light rain. After dozens of these journeys, Palantir employees have their favorite gas-station snacks on the long road to Kyiv; their favorite drivers (a hulking former soldier for the Polish special forces who goes by Horse got us there with terrifying speed); and their favorite specialty coffee shops around the capital. These days, the lobbies of Kyiv’s five-star hotels are full of security details trying to inconspicuously sip beers while waiting for foreign-defense, tech, and government executives.

Much of Palantir’s work there is conducted in stylish co-working spaces by a team of fewer than a dozen local employees who work directly with Ukrainian officials. When I visited one such office in October, three men with close-cropped hair and cargo pants stood out against the trendy crowd of 20-somethings before they disappeared to meet with Palantir employees in a room booked under a fake name. “It often feels like a tech-startup vibe: let’s see what we can do with two old cameras and a drone flying around,” says Vic, an engineer who left their job at a U.S. tech giant to work for Palantir in Kyiv after the invasion, and asked to be identified by a pseudonym for security reasons. “Except we’re in the middle of a war."

With a few clicks, a Ukrainian Palantir engineer showed me how they could mine a dizzying array of battlefield data that, until recently, would have taken hundreds of humans to analyze. Palantir’s software processes raw intelligence from sources including drones, satellites, and Ukrainians on the ground, as well as radar that can see through clouds and thermal images that can detect troop movements and artillery fire. AI-enabled models can then present military officials with the most effective options to target and enemy positions. The models learn and improve with each strike, according to Palantir.

When the company first started working with the Ukrainian government in the summer of 2022, “it was just a question of pure survival,” says Louis Mosley, Palantir’s executive vice president for U.K. and Europe. Palantir hired Ukrainian engineers who could adapt its software for the war effort, while also serving as interlocutors between the tech company and Ukraine’s sclerotic bureaucracy. Government officials were trained to use a Palantir tool called MetaConstellation, which uses commercial data, including satellite imagery, to give a near real-time picture of a given battle space. Palantir’s software integrates that information with commercial and classified government data, including from allies, which allows military officials to communicate enemy positions to commanders on the ground or decide to strike a target. This is part of what Karp calls a digital “kill chain.”

Karp with Zelensky and Fedorov (far left) in June 2, 2022. Courtesy Digital Ministry of Ukraine

Drones awaiting deployment to the front lines in July 2023. Drones awaiting deployment to the front lines in July 2023.Libkos—AP

Although recent earnings data from the company indicates that partner countries have chipped in tens of millions to offset Palantir’s investment, Ukraine has not paid Palantir for its tools and services. The company's motivations in Ukraine have little to do with short-term profit. In recent years, Palantir has sought to shed its reputation as a shadowy data-mining spy contractor as it expands its list of commercial clients. Its tools have played a role in uncovering the financial fraud carried out by Bernie Madoff, rooting out Chinese spyware installed on the Dalai Lama’s computer, and allegedly aiding in the hunt for Osama bin Laden—a long-standing rumor the company has been careful not to dispute. More recently it has highlighted its work with the U.N. World Food Programme and the use of its software to track COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution.

Karp has long dismissed widespread criticism that Palantir’s tools enable intrusive government surveillance. Amnesty International has accused the company of seeking to “deflect and minimize its responsibility to protect human rights,” and said Palantir’s tools have allowed government agencies to track and identify migrants and asylum seekers to carry out arrests and workplace raids. The CEO says he sees a moral imperative to supply Western governments with the best emerging technology, calling for “more intimate collaboration between the state and the technology sector” that he believes will allow the West to maintain its edge over global adversaries.

In Ukraine, Palantir had found an opportunity to put this mission into practice while burnishing its reputation. “People often have preconceived notions about Palantir, but our products work,” says vice president Josh Harris. “When it’s existential, and when it needs to work, you take off your blinders, you take out all the politics.” And in Ukraine’s leaders, the company found a group of young, tech-savvy officials who could help them with more than just PR.

Karp, Palantir’s CEO, casts his company’s mission as using cutting-edge technology to defend the West against global adversariesAaron M. Sprecher—Bloomberg/Getty Images

When I Visited Last Fall, the stately avenue that leads to Ukraine’s cabinet building in downtown Kyiv was lined with rusted antitank barricades and checkpoints manned by rifle-toting soldiers. The windows of the imposing Soviet-era building that houses most of Zelensky’s government were covered by sandbags. Government workers wove through the darkened hallways, using their phones to light the way.

Fedorov’s sixth-floor office was illuminated by neon lamps. A treadmill, boxing gloves, and an exercise bike made up a small gym in one corner. At a conference table flanked by large screens, a stone sculpture of an alien wore a Biden-Harris 2020 cap. A neat stack of fanned-out magazines near the doorway bore a message to the world: "Ukraine: Open for Business."

For the past 18 months, Fedorov and his deputies have brought that message to tech CEOs, defense conferences, and business summits. The former digital-marketing entrepreneur, who is the youngest member of Zelensky’s cabinet, has framed the battlefields of Ukraine and its modern wartime society as the best possible testing ground for cutting-edge innovation. “The tech sector will be the main engine of our future growth,” Fedorov told me. On the day we spoke in his office, Fedorov had just finished one of his regular calls with leaders at Microsoft and was due to meet with Google executives visiting Kyiv. He has been on the cover of Wired magazine and spoken about Ukraine’s tech achievements in wartime at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. It’s a striking turnaround from when I first interviewed Fedorov in March 2022. Back then, he was speaking into Airpods from a darkened bunker with an erratic video connection, and his team was resorting to Twitter to lobby and shame the world’s largest tech companies to block their services in Russia.

In the first months of the war, Ukrainian officials accepted whatever help was offered. They took cyber and cloud services from Microsoft, Amazon, and Google; Starlink terminals from Elon Musk; facial-recognition software from Clearview AI; and a host of experimental drones, cameras, and jamming kits from large defense companies and startups alike. Fedorov rallied an “IT Army” of 400,000 volunteer hackers to help protect critical infrastructure and counter Russian cyberattacks. “In the beginning there was no process. There was chaos,” says Alex Bornyakov, Fedorov’s 41-year-old deputy. By that summer, he adds, “we had to calm ourselves down and say, ‘We can’t go on this way. We need a strategy for the long term.’”

The solution they landed on was to build a tech sector that could not just help win the war but also serve as a pillar of Ukraine’s economy when it was over. Israel, a hotbed for tech startups, was a model. Ukraine’s 300,000 tech workers, many employed by American companies before the war, were eager to contribute to the fight by working for the multiplying number of domestic military startups. “We decided, let’s send a message that it’s not about donations,” says Bornyakov. “The best way to help Ukraine is to invest in Ukraine.”

They first tested the new pitch at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland, that July. The response was swift. Silicon Valley investors launched the Blue and Yellow Heritage Fund to invest in Ukrainian startups. “It is not a charity,” founding partner John Frankel said at the time. “It’s our way of contributing, but also getting what we think will be a high return on capital.”

Fedorov and Bornyakov set up incentives, expanding special tax breaks to defense-tech companies to entice them to come to Kyiv. They launched “trade missions” to conferences in London, San Francisco, Toronto, Brussels, Davos, and Dubai. By early 2023, the road show was almost going too well. “We were bombarded with so much military defense stuff from [startups] saying, ‘I have this idea of how to win the war,’” says Bornyakov. He and Fedorov launched a digital platform called Brave1, through which defense-tech companies, startups, and ordinary Ukrainians can pitch their products. It has received more than 1,145 submissions, hundreds of which are being tested on the battlefield, according to Fedorov’s office. This includes drones, AI-transcription software that could decipher Russian military jargon, radios that prevent Russian jamming, patches for cyber vulnerabilities, and demining equipment.

In meetings with more than a dozen Ukrainian officials, I was given demos of how many of these tools work—and how they’re used for tasks beyond the battlefield. Dmytro Zavgorodnii, a digital official at the Ministry of Education and Science, showed me dashboards with satellite maps tracking schools affected by air-raid alerts or power outages, the condition of roads, and estimates for how long it would take students to access shelters with wi-fi. This software, provided by Palantir, will help the ministry determine how to keep schools open, provide laptops and connectivity in conflict zones, and conduct national testing with minimal disruption. “It’s like a superpower,” Zavgorodnii explained.

Huddled around a laptop, Ukrainian Economy Minister Yulia Svyrydenko showed me how Palantir’s software has made it possible to aggregate dozens of previously siloed data streams to help officials clear the country of land mines. Ukraine has become the most heavily mined country in the world, with unexploded ordnance endangering more than 6 million civilians and making vast swathes of farmland unusable. The ministry works with Palantir to develop models to determine where demining efforts could have the biggest impact, helping Svyrydenko devise a plan to bring 80% of contaminated land back into economic use within 10 years. In an interview at a Kyiv hotel, Ukraine’s Attorney General Andriy Kostin told me how his agency employs Palantir’s software in its effort to prosecute alleged Russian war crimes—using its analysis of vast troves of data to link allegations of war crimes to pieces of evidence, including satellite imagery, troop movements, and open-source data like photos and videos uploaded by Ukrainians on social media.

Other tech companies have also been supplying the Ukrainian government with products to help win the war. One of the most successful has been Clearview, which Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs Leonid Tymchenko described to me as the country’s “secret weapon” against invading Russian troops. It’s being used by 1,500 officials across 18 Ukrainian agencies, and has helped identify more than 230,000 Russian soldiers who have participated in the military invasion, making it possible to link them to evidence of alleged war crimes, according to Ukrainian officials. Clearview is reaping the benefits too. Ukrainian engineers have “definitely made our product a lot better,” its CEO Hoan Ton-That says.

A Short Drive From Downtown Kyiv sits a bustling high-tech “innovation park” called Unit City. It’s a sprawling campus of ultramodern offices built on the grounds of an old Soviet factory that produced knockoffs of German motorcycles. Unit City is the epicenter of Ukraine’s efforts to turn its tech industry “into the main innovation hub in Europe,” says partner Kirill Bondar. Since the start of the war, U.S. and European government officials have visited Unit City; so have tech executives and luminaries like Vitalik Buterin, a creator of the Ethereum cryptocurrency blockchain.

Among the businesses based here is a Ukrainian military startup accelerator called D3 (Dare to Defend Democracy). High-profile foreign investors, including former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, have pumped more than $10 million into D3. In trips to Ukraine, Schmidt says, he became convinced that the country’s front lines would produce breakthroughs in the use of AI and drones. “There’s simply so much volume, there’s so many players, there’s so much innovation,” Schmidt says. “It’s really impressive.”

Schmidt is among an array of prominent foreign investors attracted to the nascent promise of Ukraine’s tech sector. German drone manufacturer Quantum Systems recently announced it would open a research and development center in Kyiv. The Japanese tech giant Rakuten also announced its plan to open an office in the capital. Turkish drone maker Baykar has invested nearly $100 million to build a research and manufacturing center in Ukraine by 2025. At a recent European defense conference, “no one would even look at a product unless it had Tested in Ukraine stamped on it,” Deborah Fairlamb, the co-founder of Green Flag Ventures, a new fund dedicated to investing in Ukrainian startups, told me.

While encouraging the investment, the Ukrainian government is also seeking to preserve valuable battlefield data for its own budding defense industry. Officials told me they intend to export the innovations coming out of the conflict to address a variety of global crises beyond war, from disruptive blackouts to natural disasters. Over time, Kyiv has become much more selective about who they allow to access their front lines to refine their products. “There has been a change in the message,” a senior Palantir executive told me as he left a meeting with officials in Kyiv. “Now it seems they’re saying, ‘You know, you’re lucky to be here.’”

Outside Its Borders, there are signs that Ukraine’s war lab has helped establish it as a major player on the global tech scene. At Web Summit, the world’s largest tech conference, which took place in Lisbon in November, Ukraine’s pavilion loomed over other exhibits in the cavernous arena. Two years earlier, its presence had been limited to a corner booth. Now 25 Ukrainian startups had set up kiosks, and dozens of young workers in yellow Team Ukraine shirts handed out promotional booklets. “The best time to invest in Ukraine is NOW, not after the war,” its marketing materials read.

Some of the lessons learned on Ukraine’s battlefields have already gone global. Citing Ukraine as a blueprint, Taiwan has recruited commercial drone makers and aerospace firms to embed within the military to build up its drone program amid rising tensions with China. Last month, the White House hosted Palantir and a handful of other defense companies to discuss battlefield technologies used against Russia in the war. The battle-tested in Ukraine stamp seems to be working.

So is Palantir’s campaign to rehabilitate its reputation. In early January, amid the ongoing war against Hamas, Israel’s Defense Ministry struck a deal with the company to “harness Palantir’s advanced technology in support of war-related missions.” To Palantir executives, the demand for their tools from one of the world’s most technologically advanced militaries spoke for itself. But they were surprised when the usually discreet Israelis allowed the partnership to be made public, “almost as if the relationship itself would act as a military deterrence,” according to a person familiar with the discussions.

The next generation of AI warfare remains in its early stages. Some U.S. officials are skeptical that it will contribute to a military victory for Ukraine. As the war enters its third year, the Ukrainian counteroffensive has continued to stall. “The tech bros aren’t helping us too much,” Bill LaPlante, the U.S. Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, told a defense conference in November. “We’re not fighting in Ukraine with Silicon Valley right now, even though they’re going to try to take credit for it.”

Ukraine’s use of tools provided by companies like Palantir and Clearview also raises complicated questions about when and how invasive technology should be used in wartime, as well as how far privacy rights should extend. Clearview CEO Ton-That contends that, like many new tools in this conflict, his facial-recognition software is “a technology that shines and only really is appreciated in times of crisis.” But alarmed human-rights groups and privacy advocates warn that unchecked access to his tool, which has been accused of violating privacy laws in Europe, could lead to mass surveillance or other abuses.

That may well be the price of experimentation. “Ukraine is a living laboratory in which some of these AI-enabled systems can reach maturity through live experiments and constant, quick reiteration,” says Jorritt Kaminga, the director of global policy at RAIN, a research firm that specializes in defense AI. Yet much of the new power will reside in the hands of private companies, not governments accountable to their people. “This is the first time ever, in a war, that most of the critical technologies are not coming from federally funded research labs but commercial technologies off the shelf,” says Steve Blank, a tech veteran and co-founder of the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation at Stanford University. “And there’s a marketplace for this stuff. So the genie’s out of the bottle.”—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Simmone Shah/New York •

#Ukraine 🇺🇦#Tech Giants#Artificial intelligence (AI)#War Lab 🧫🧪 🥼#Vera Bergengruen#Palantir Technologies#Poland 🇵🇱#Russia 🇷🇺#Alex Karp | CEO | Palantir Technologies#Artificial-Intelligence Software#Modern-Day Goliath#Social Theorist | Jürgen Habermas#Monoculture

0 notes

Text

Maximize Your Trades. Trading Signals 13 October 2023 & Strategy Inside

Trading Signals 13 October 2023. Texas Instruments Incorporated, Apple, Boston Properties, Unity Software, Nexstar Media Group, Pepsico

#ADBE #NFLX #FB #NXST #PEP #VZ #PWR #RCL #UGI #PFE #RCL #GBLE #RKT #TTD #PLTR #OKE #MU #NEE #KHC #AAPL #AI #ALB #CTVA

Trading Signals 13 October 2023. Texas Instruments Incorporated, Apple, Boston Properties, Unity Software, Nexstar Media Group, Pepsico, Verizone, Pfizer, Rocket Companies, UGI Corporation, The Trade Desk, Netflix, Meta Platforms. Palantir Technologies, ONEOK, Starbucks, BILL Holdings, Micron Technology, NextEra Energy, Adobe, Quanta Services, The Kraft Heinz Company, C3 AI, Albemarle, Corteva,…

View On WordPress

#Adobe#Albemarle#BILL Holdings#C3 AI#Corteva#Meta Platforms#Micron Technology#Netflix#Nexstar Media Group#NextEra Energy Partners LP#NiSource#ONEOK#Palantir Technologies#PepsiCo#Quanta Services#Rocket Companies#Starbucks#The Kraft Heinz Company#The Trade Desk#Trading signals#Trading strategy#UGI Corporation#Unity Software#Verizone

0 notes

Text

Colorado's Palantir and Maxar play key roles in helping Ukraine battle Russia

Colorado’s Palantir and Maxar play key roles in helping Ukraine battle Russia

Alex Karp, co-founder and CEO of Palantir Technologies, visited Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Kyiv. Photo courtesy of Ukraine government

Two prominent Denver area companies are playing prominent roles in assisting Ukraine and U.S. interests in the battle against Russian forces.

What’s happening: Palantir Technologies’ CEO Alex Karp met with President Volodymyr Zelensky in Ukraine…

View On WordPress

#battle#Colorado#Colorados#Helping#Key#Maxar#News media#Palantir#Palantir Technologies#Play#Roles#Russia#russian invasion of ukraine#satellites#Ukraine#Volodymyr Zelensky

1 note

·

View note

Text

she is thinking and considering

#well she wouldn't really - saruman is a squatter who only got to where he is by way of numenorean technology (palantir) and imitating sauron#but it was too aesthetically pleasing not to screenshot it#fajar#lotro#lord of the rings online#my posts

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

tech workers need to unionize

#im ok and im not thinking about the soul crushing fact#that the us military and dod are so deeply intertwined with the past and present of computing technologies#modern internet? darpa. military project#spacex? military project#all social media companies? have already sold your data to law enforcement#ai predictive policing palantir amazon microsoft ICE etc etc etc#these arent just superficial ties they r the foundation of the industry#(just as imperialism is a foundation of the country)#and these connections arent going to break except under immense pressure#from outside AND inside the workplace#OH YEAH AND NOT EVEN VIDEO GAMES ARE INNOCENT#UR FAVORITE MAJOR 3D ENGINE HAS MILITARY CONTRACTS FOR DEVELOPING TRAINING SIMULATIONX#truly therr r just#tooooooooo many goddamn examples

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elon Musk - Tesla Bull - Investing Design - Bull Market Baby

by WigOutlet

Elon Musk - Tesla Bull - Investing Design

0 notes

Text

ElevenLabs' AI Voice Generator Can Fake Voices in 30 Languages

What’s become one of the internet’s go-to companies for creating realistic enough visual deepfakes now has the ability to clone your voice and force it to speak in a growing variety of tongues. ElevenLabs announced Tuesday its new voice cloning now supports 22 more languages than it did previously, including Ukrainian, Korean, Swedish, Arabic, and more.

ChatGPT’s Creator Buddies Up to Congress |…

View On WordPress

#Applications of artificial intelligence#artificial intelligence#Computer graphics#Culture#Deep learning#Draft:NoiseGPT#ElevenLabs#Entertainment#Gizmodo#Inflection AI#Internet#Mati Staniszewski#Mustafa Suleyman#PALANTIR#Paradox Interactive#Rutger Hauer#Speech synthesis#Technology

0 notes

Text

These claims of an extinction-level threat come from the very same groups creating the technology, and their warning cries about future dangers is drowning out stories on the harms already occurring. There is an abundance of research documenting how AI systems are being used to steal art, control workers, expand private surveillance, and seek greater profits by replacing workforces with algorithms and underpaid workers in the Global South.

The sleight-of-hand trick shifting the debate to existential threats is a marketing strategy, as Los Angeles Times technology columnist Brian Merchant has pointed out. This is an attempt to generate interest in certain products, dictate the terms of regulation, and protect incumbents as they develop more products or further integrate AI into existing ones. After all, if AI is really so dangerous, then why did Altman threaten to pull OpenAI out of the European Union if it moved ahead with regulation? And why, in the same breath, did Altman propose a system that just so happens to protect incumbents: Only tech firms with enough resources to invest in AI safety should be allowed to develop AI.

[...]

First, the industry represents the culmination of various lines of thought that are deeply hostile to democracy. Silicon Valley owes its existence to state intervention and subsidy, at different times working to capture various institutions or wither their ability to interfere with private control of computation. Firms like Facebook, for example, have argued that they are not only too large or complex to break up but that their size must actually be protected and integrated into a geopolitical rivalry with China.

Second, that hostility to democracy, more than a singular product like AI, is amplified by profit-seeking behavior that constructs increasingly larger threats to humanity. It’s Silicon Valley and its emulators worldwide, not AI, that create and finance harmful technologies aimed at surveilling, controlling, exploiting, and killing human beings with little to no room for the public to object. The search for profits and excessive returns, with state subsidy and intervention clearing the way of competition, has and will create a litany of immoral business models and empower brutal regimes alongside “existential” threats. At home, this may look like the surveillance firm and government contractor Palantir creating a deportation machine that terrorizes migrants. Abroad, this may look like the Israeli apartheid state exporting spyware and weapons it has tested on Palestinians.

Third, this combination of a deeply antidemocratic ethos and a desire to seek profits while externalizing costs can’t simply be regulated out of Silicon Valley. These are fundamental attributes of the industry that trace back to the beginning of computation. These origins in optimizing plantations and crushing worker uprisings prefigure the obsession with surveillance and social control that shape what we are told technological innovations are for.

Taken altogether, why should we worry about some far-flung threat of a superintelligent AI when its creators—an insular network of libertarians building digital plantations, surveillance platforms, and killing machines—exist here and now? Their Smaugian hoards, their fundamentalist beliefs about markets and states and democracy, and their track record should be impossible to ignore.

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximize Your Trades. Trading Signals 12 October 2023 & Strategy Inside

Trading Signals 12 October 2023. Texas Instruments Incorporated, Apple, Boston Properties, Unity Software, Nexstar Media Group,

#ADBE #NFLX #FB #NXST #PEP #VZ #PWR #RCL #UGI #PFE #RCL #GBLE #RKT #TTD #PLTR #OKE #MU #NEE #KHC #AAPL #AI #ALB #CTVA #NI

Trading Signals 12 October 2023. Texas Instruments Incorporated, Apple, Boston Properties, Unity Software, Nexstar Media Group, Pepsico, Verizone, Pfizer, Rocket Companies, UGI Corporation, The Trade Desk, Netflix, Meta Platforms. Palantir Technologies, ONEOK, Starbucks, BILL Holdings, Micron Technology, NextEra Energy, Adobe, Quanta Services, The Kraft Heinz Company, C3 AI, Albemarle, Corteva,…

View On WordPress

#Adobe#Albemarle#BILL Holdings#C3 AI#Corteva#Meta Platforms#Micron Technology#Netflix#Nexstar Media Group#NextEra Energy Partners LP#NiSource#ONEOK#Palantir Technologies#PepsiCo#Quanta Services#Rocket Companies#Starbucks#The Kraft Heinz Company#The Trade Desk#Trading signals#Trading strategy#UGI Corporation#Unity Software#Verizone

0 notes

Photo

Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else's opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.

- Oscar Wilde, De Profundis

It’s true that when people strongly desire something, such as a new item of clothing or a luxury good, they might feel like they ‘need’ it - but they don’t need it in the same way that they need water or food. Their survival isn’t at stake.

Desire (as opposed to need) is an intellectual appetite for things that you perceive to be good, but that you have no physical, instinctual basis for wanting - and that’s true whether those things are actually good or not.

Your intellectual appetites might include knowing the answer to a mathematics problem; the satisfaction of receiving a text from someone you have a crush on; or getting a coveted job offer. These things won’t necessarily cause physical pleasure. They might spill over into physical enjoyment, but they are not dependent on it. Rather, the pleasure is primarily intellectual.

The 13th Century philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas wrote that these intellectual appetites are part of what has traditionally been called the ‘will’. When a person wills something, they strive toward it. If they come to possess the object of their desire, their will finds rest in it - and they are able to experience joy, so long as they are able to rest in the object of their desire.

But, for most people, such joy is fleeting. There is always something else to strive for - and this keeps most of us in a constant, sometimes painful, state of never-satisfied striving. And that striving for something that we do not yet possess is called desire. Desire doesn’t bring us joy because it is, by definition, always for something we feel we lack. Understanding the mechanism by which desires take shape, though, can help us avoid living our lives in an endless merry-go-round of desire.

When it comes to understanding the mystery of desire, one contemporary thinker stands above all others: the French social theorist René Girard, a historian-turned-polymath who came to the United States shortly after the Second World War and taught at numerous US universities, including Johns Hopkins and Stanford. By the time he died in 2015, he had been named to the Académie Française and was considered one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.

Girard realised one peculiar feature of desire: ‘We would like our desires to come from our deepest selves, our personal depths,’ he said, ‘but if it did, it would not be desire. Desire is always for something we feel we lack.’ Girard noted that desire is not, as we often imagine it, something that we ourselves fully control. It is not something that we can generate or manufacture on our own. It is largely the product of a social process.

‘Man is the creature who does not know what to desire,’ wrote Girard, ‘and he turns to others in order to make up his mind.’ He called this mimetic, or imitative, desire. Mimesis comes from the Greek word for ‘imitation’, which is the root of the English word ‘mimic’. Mimetic desires are the desires that we mimic from the people and culture around us. If I perceive some career or lifestyle or vacation as good, it’s because someone else has modelled it in such a way that it appears good to me. In other words, we copy other people because it’s low risk and we expect a safer return.

Girard had spent the last 14 years of his career as the Andrew B Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization, at Stanford, where he was the philosophical mentor of Peter Thiel, co-founder of the payments company PayPal and the intelligence company Palantir Technologies - a billionaire who was the first major investor in Facebook. Thiel has credited Girard with helping him see the power of Facebook before most others - and also for helping him escape an unfulfilling career in corporate law and finance. Once he was able to break free from the mimetic herd, he could start thinking more for himself and undertaking projects that were not merely the product of other people’s desires.

I began to realise that understanding mimetic desire was crucial if I wanted to break free from the cycle that I was stuck in. If, like me, you’d like to get a deeper understanding of your own wants and desires, and to take more control over them, then you need to read more from René Girard and especially his book ‘Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World’ (1978).

#wilde#oscar wilde#quote#mimicry#mimetic theory#rené girard#needs#desires#copying#society#sociology#human nature#human condition

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

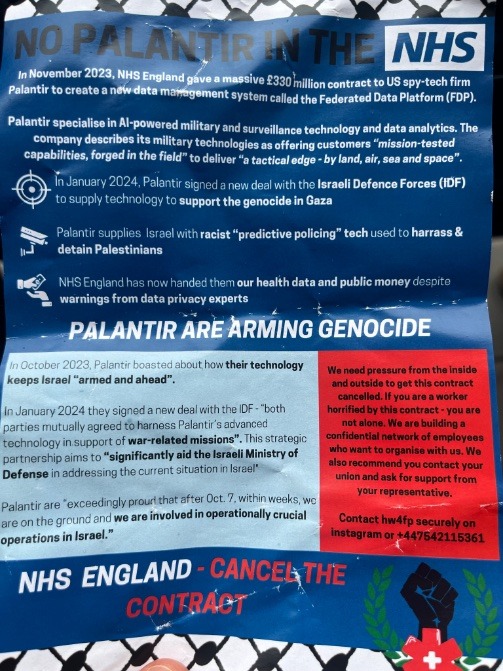

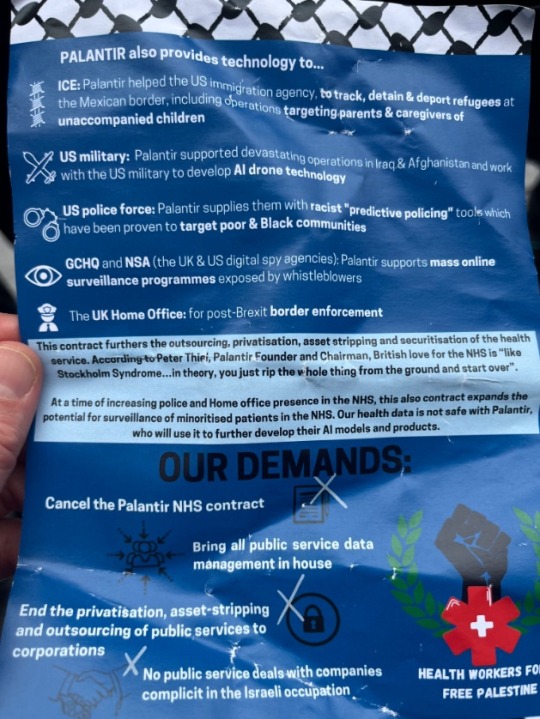

Hundreds of British healthcare workers blocked the entrance to NHS England’s headquarters in central London demanding the cancellation of business deals with American company Palantir citing Israel’s “war on hospitals”.

A statement from the group Health Workers for a Free Palestine accused Palantir of supplying “advanced technology to Israel’s military”.

NHS England awarded a 330 million pound ($415m) contract to Palantir in November. Healthcare staff are “shutting down access to NHS England protesting its contract” with a company “complicit in the systematic destruction of Gaza’s healthcare system”, it said.

Palantir’s CEO Alex Karp has said he’s “exceedingly proud” of the company’s involvement in “operationally crucial operations in Israel”.

The protest comes as Israel continues to target Gaza’s overwhelmed and destroyed hospitals with raids.

-- "UK healthcare workers protest against US company supplying Israel’s army" by Nils Adler and Farah Najjar for Al Jazeera, 3 Apr 2024 13:10 GMT

🇵🇸🚫No genocide enablers Palantir in NHS England!

📢 “Stop the war, stop the pain, never ever in our name”

Picketing since 7am! If you work for the NHS, join the campaign to end the contract with Palantir @Workers4Pal

-- Ewa Jasiewicz, 3 Apr 2024 6:29 AM EDT

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earlier this summer, I showed up uninvited at a midtown Manhattan music venue, where a startup named the Praxis Society was holding an event as part of a weeklong series to promote its flagship product: a free-market Mediterranean city-state the company hopes to build under the leadership of a CEO who, former employees said, is interested in fascist authors and occultism and has touted a book that argues Black people are intellectually inferior to whites.

Praxis, a for-profit corporation, was founded as Bluebook Cities in 2019 by Californian Dryden Brown and former Boston College wide receiver Charlie Callinan. They envisioned an autonomous enclave where the free-market dreams of Chicago and Austrian school economists would become reality, a place libertarians could settle without the tyranny of regulation. While the project draws inspiration from ancient Greece and Rome, Brown, the company’s CEO, said in a 2021 interview that its style would be “hero futurism” with a “neo-Gilded Age kind of aesthetic.”

If this sounds like fantasy, it probably is. But it’s one that’s captured the minds of real—and really rich—people. In 2021, the company’s seed round raised roughly $4 million, including from Pronomos Capital, a libertarian city-building fund started in 2019 with significant financial backing from Thiel. Other participants included Thiel’s close friend Balaji Srinivasan; Joe Lonsdale, who cofounded the analytics and intelligence company Palantir Technologies with Thiel; and Bedrock Capital, a fund launched by a former partner in Thiel’s Founders Fund. Praxis followed up several months later with a Series A round that brought in $15 million, much of it from cryptocurrency investors, including Three Arrows Capital and Sam Bankman-Fried’s Alameda Research, which both later spectacularly imploded. Emergent Ventures, another Thiel-backed fund led by economist Tyler Cowen and housed in George Mason University’s Koch-supported Mercatus Center, has also invested.

Brown and at least one other senior Praxis employee were interested in “this strange Nazi occultism,” one of those three ex-staff members said, citing the pair’s appreciation of Evola, who co-authored another book offering “instructions for developing psychic and magical powers,” according to its contemporary publisher. (Scholars have written about Nazi links to Ariosophy—an esoteric ideology blending mysticism, racism, nationalism, and antisemitism—and documented the SS’s fascination with Norse mythology and Eastern spiritual traditions. If you’ve seen Raiders of the Lost Ark, you know the Hollywood version.) Another of those former employees, also citing Evola, confirmed Brown’s interest in the occultist bent of the SS. An internal slideshow briefing staff on the company’s brand and philosophy presented Evola’s thinking on the four “functional classes” or castes, and suggested the categories should guide the company’s recruitment of new members and prospective residents, according to that former worker.

“When you’re hired,” one former employee said, “you get a welcome packet with 11 book recommendations. One of them is Bronze Age Mindset,” an openly racist and fascist book by the anonymous far-right influencer Bronze Age Pervert that warns of a coming struggle against the “enemies of Western man and the enemies of beauty.”

Part of the company’s strategy involves drawing participants in New York’s downtown scene to its events in the hope of bringing some on board. Succession actress Dasha Nekrasova, a leading light of the so–called Dimes Square set and a co-host of Red Scare—a once-socialist podcast that has taken a turn to the right—attended a June black-tie banquet at the Yale Club for current and prospective members. Thiel money has also directly funded downtown events attended by the arty set Praxis is trying to lure; in 2022, BuzzFeed News revealed the billionaire’s financial backing of the New People’s Cinema Club, which boasted of screening transgressive films without mind to political correctness. Jokes about sloshing “Thielbucks” among the anti-woke downtown set have become a meme.

In Brown’s vision, Thiel’s or his associates’ money wouldn’t just be going to film impresarios or their parties; it would go toward a city where both young neo-reactionaries and their post-left associates might have a hand in forging something tangible, something beyond a podcast or a Substack. Of course, Praxis hasn’t done anything tangible. But even if construction never starts, the company’s inroads with the scene are another vector for reactionary Silicon Valley perspectives to acquire cultural purchase.

The company has scoped a rotating set of possible sites for its city along the Mediterranean shore. Kunapuli told me they were trying to decide between Italy and Morocco. (I later heard Montenegro is in the mix.) “There’s tradeoffs,” Kunapuli acknowledged, as we looked at the renderings. Italy is more trusted by Westerners, a place where Praxis company leaders believe government and industry are more likely to come through on legal contracts, he explained, before conceding the same conditions would make it “harder to influence and change regulations and policies” than in Morocco.

A record-breaking heat wave and forest fires would end up hitting the Mediterranean a month later. As best as I could tell, Praxis didn’t have a plan to shield its new-Gilded Age city from such catastrophes. As it turns out, you can’t exit everything.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌼 & 🔮&⚙ for the asks? 👀

🌼 simbelmynë: You've got the opportunity to bring one character back to life, who is it?

Only One! boromir lives aus are always good, but. hmm. aw there are just. so many to choose from lol. i think dropping any first age elf in the shire would just be really funny for everyone involved. actually no, put beren in the shire to chill for awhile (luthien probably comes with just bc she's Like That. her interacting with hobbits would be very funny too)

🔮 palantír: you've found a palantir! Who are you hitting up in middle earth? What are you telling them?

hey. hey. earnur. do not. yeah i know it's the witch-king- yeah- yeah i know. but dude. Do Not

⚙ technology: everything is exactly the same but you can give one character a modern invention. Who is it and what are you giving them?

i think we should give saruman some scuba gear and see if he actually goes looking for the ring in the ocean. whether or not he actually believes it's there or is just keeping up appearances

#i just think it would be funny#actually that's my thought process for most of these#idk if earnur would pick up lol but yknow#there's a whole list of ppl you could palanskype to tell them Do Not; he's selected more or less at random from that#ask games#ty friend :D

4 notes

·

View notes