#O.W. Gurley

Text

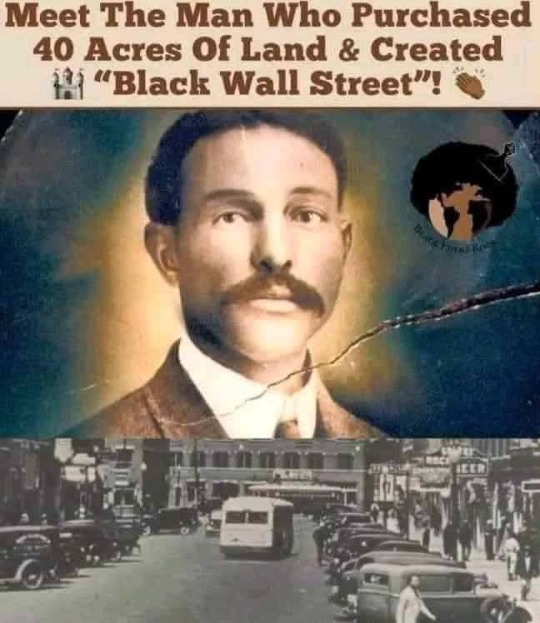

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

#Queued#Black Wall Street#O.W. Gurley#Ottowa Gurley#Gurley#Tulsa#North Tulsa#Greenwood Avenue#Greenwood#Tuskegee#Booker T. Washington#Booker T Washington#Vernon AME Church#Black History Month#Black History

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

Source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/o-w-gurley-1868-1935/

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

Source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/o-w-gurley-1868-1935/

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

O. W. GURLEY (1868-1935) Ottowa or O.W. Gurley is remembered as one of the wealthiest Men in Tulsa, Oklahoma before the 1921 Tulsa Massacre destroyed his property & forced him to flee. Ottowa Gurley was born on Christmas Day in 1868 to freed slaves in Huntsville, Alabama, Gurley grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. He was self-educated & eventually married his childhood sweetheart, Emma. After a brief time as a teacher, he worked for the U.S. Postal Service. 1893, Gurley participated in the Cherokee Outlet Land Rush in Indian Territory & staked a claim in Perry, Noble County. Gurley ran unsuccessfully for treasurer of Noble County but later became principal of the town’s school and operated a general store in the community. 1905, Gurley & his wife sold their property in Noble County & moved 80mi to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa & established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Ave. He subdivided his plot into residential & commercial lots & eventually opened a grocery store. As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910-1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2k to nearly 9k in a city with a total population of 72k. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, & other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington. Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards & theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ci-dJkNOcXh5B0qAH6CFjKW6Q4XEYeHb4JNUv00/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Photo

John the Baptist (J.B.) Stradford (September 10, 1861 - December 22, 1935) was born a free man in Versailles, KY. His father, J.C. Stradford was a former slave who had been emancipated and was living in Stradford, Ontario. Not much is known about his early life before he graduates from Oberlin College and Indiana Law School. He was a shrewd businessman. While living in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, and St. Louis, he ran pool halls, bathhouses, shoeshine parlors, and boarding houses. He migrated to Tulsa with his wife Augusta, becoming one of the most prominent individuals. He got involved in the building of the all-black Greenwood section of Tulsa with O.W. Gurley, as they both built fortunes in real estate and rental units. By WWI, Greenwood had become the “Black Wall Street of America”. He became a civil rights activist. He filed a lawsuit against St. Louis and San Francisco Railway company for failing to provide proper accommodations for African American travelers, and he publicly opposed lynching and many of the new Jim Crow laws enacted when Oklahoma became a state. He opened the luxurious fifty-four-room Stradford Hotel. It was the largest African American-owned and operated hotel in Oklahoma and one of the few African American-owned hotels in the US. It had a dining hall, a gambling room, a saloon, and a large hall for events such as live music. He had become the richest African American man in Tulsa, owning over fifteen rental properties and an apartment building. When the Tulsa Massacre began on June 1, 1921, he stood in front of his hotel armed with a rifle until he was overwhelmed by the white mobs. The entire black commercial district was destroyed. He and twenty other African Americans were indicted for inciting a riot. His son, attorney C.F. Stradford posted bail, and he escaped to Independence, Kansas before settling in Chicago. They fought his extradition. He formed a group of investors to build a new luxury hotel but the project ran out of money. He own a candy store, barbershop, and a pool hall but he never duplicated his success. A Tulsa jury acquitted him of all charges relating to the Tulsa Race Riot. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CiU4xZJLh8QZV6EroALkK9HczYpBqsJDJKZNMs0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

⚖️#ArtIsAWeapon 101 years ago today (May 31, 1921) #TulsaMassacre #NeverForget

Artist @ajamu

Black Blood, No.14: In the spirit of O.W. and Emma Gurley

2021

Mischtechnik on linen canvas.

"'Black Wall Street: A Case for Reparations' is @ajamu's ongoing series of large-scale paintings that capture the imagined lives of Black professionals in the #GreenwoodDistrict before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The portraits present a spiritually uplifting dedication to the people who called Greenwood their home over a century ago." www.ajamukojo.com

•

•

Reposted from @nmaahc #OnThisDay in 1921, the deadliest racial massacre in U.S. history began in the thriving Greenwood African American community of Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was one in a series of actions of racist violence that convulsed the United States in towns and cities beginning with the period of Reconstruction in the late 19th century.

In Tulsa--as in all of these massacres--white mobs destroyed Black communities, property, and lives. More than century after the riot, the people of Tulsa and the nation continue to struggle to reckon with the massacre’s multiple legacies.

Our collection materials help fill the silences in our nation’s memory around events such as the Tulsa Race Massacre and its reverberations, preserving and sharing wider stories of Black communities in Oklahoma, and centering the testimonies of survivors and their descendants.

Swipe to see two of these objects -- pennies charred during the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and view & learn more at the link in our bio. #APeoplesJourney #ANationsStory

📸 Images 2 & 3 - Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Cassandra P. Johnson Smith

Image 4 - Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Scott Ellsworth

#Tulsa #Reparations #AmericanHistory #DomesticTerrorists #WhiteSupremacy #KKK #BlackWallStreet #TulsaRaceRiots #WatchmenHBO #LovecraftCountry #TulsaRaceMassacre #BlackArtists

0 notes

Photo

THIS IS A PIVOTING POINT IN HISTORY

IT SHOW WHAT A BLACK COMMUNITY CAN DO GIVEN THE CHANCE

AND

WHAT A WHITE COMMUNITY CAN DO GIVEN A CHANCE

WE MUST LEARN FROM HISTORY AND ACT ON THE KNOWLEGE TO IMPROVE OR CONTINUE TO LIVE WITH THE DAMAGES IN THE WORST WAY.

One hundred years ago on May 31, 1921, and into the next day, a white mob destroyed Tulsa’s burgeoning Greenwood District, known as the “Black Wall Street,” in what experts call the single-most horrific incident of racial terrorism since slavery.

HOW BLACK WALL STREET STARTED

A BLACK MAN’S DREAM WHO UNDERSTOOD THE POWER OF THE BLACK DOLLAR IN A BLACK COMMUNITY-

IT WAS BLACK ON BLACK DIME NOT CRIME

O.W. Gurley, a wealthy Black landowner, purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa in 1906 and named the area Greenwood. Its population stemmed largely from formerly enslaved Black people and sharecroppers who relocated to the area fleeing the racial terror they experienced in other areas.

O. W. Gurley (born Ottaway W. Gurley; December 25, 1867 – August 6, 1935) was once one of the wealthiest Black men and a founder of the Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as "Black Wall Street"

Gurley was born in Huntsville, Alabama to John and Rosanna Gurley, formerly enslaved persons, and grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. After attending public schools and self-educating he worked as a teacher and in the postal service. While living in Pine Bluff, Gurley married Emma Wells, on November 6, 1889. They had no children.

In 1889, he came to what was then known as Indian Territory to participate in the Oklahoma Land Rush, staking a claim in what would be known as Perry, Oklahoma. The young entrepreneur had just resigned from an appointment under president Grover Cleveland in order to strike out on his own. In Perry he rose quickly, running unsuccessfully for treasurer of Noble County at first, but later becoming principal at the town’s school and eventually starting and operating a general store for 10 years.

Greenwood District

In 1905, Gurley sold his store and land in Perry and moved with his wife, Emma, to the oil boomtown of Tulsa, where he purchased 40 acres of land which was "only to be sold to colored. The first law passed in the new State of Oklahoma, 33 days after statehood, set in place a Jim Crow system of legally enforced segregation, and required blacks and whites to live in separate areas.

However, Oklahoma was considered a significant economic and social opportunity by Gurley, politician Edward P. McCabe and others, leading to the establishment of 50 all-black towns and settlements, among the highest of any state or territory.

Among Gurley's first businesses was a rooming house which was located on a dusty trail near the railroad tracks. This road was given the name Greenwood Avenue, named for a city in Mississippi. The area became very popular among black migrants fleeing the oppression in Mississippi.

They would find refuge in Gurley's building, as the racial persecution from the south was non-existent on Greenwood Avenue. On the contrary, Greenwood was later dubbed Black Wall Street as it became increasingly self-sustained and catered to upwardly mobile Black people] Gurley also provided monetary loans to Black people wanting to start their own businesses.

In addition to his rooming house, Gurley built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre (32 ha) farm in Rogers County. Gurley also founded what is today Vernon AME Church He also helped build a black Masonic lodge and an employment agency.

This implementation of "colored" segregation set the Greenwood boundaries of separation that still exist:

PART 1 OF 3

BLACK PARAPHERNALIA DISCLAIMER

IMAGES FROM GOOGLE IMAGE

Gurley formed an informal partnership with another Black American entrepreneur, J.B. Stradford, who arrived in Tulsa in 1899, and they developed Greenwood in concert. In 1914, Gurley's net worth was reported to be $150,000 (about $3 million in 2018 dollars). And he was made a sheriff's deputy by the city of Tulsa to police Greenwood's residents, which resulted in some viewing him with suspicion.

By 1921, Gurley owned more than one hundred properties in Greenwood and had an estimated net worth between $500,000 and $1 million (between $6.8 million and $13.6 million in 2018 dollars). Gurley's prominence and wealth were short lived, and his position as a sheriff's deputy did not protect him during the race massacre. In a matter of moments, he lost everything

During the race massacre, The Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood, the street's first commercial enterprise as well as the Gurley family home, valued at $55,000, was lost, and with it Brunswick Billiard Parlor and Dock Eastmand & Hughes Cafe. Gurley also owned a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood. It housed Carter's Barbershop, Hardy Rooms, a pool hall, and cigar store. All were reduced to ruins. By his account and court records, he lost nearly $200,000 in the 1921 race massacre

Because of his leadership role in creating this self-sustaining exclusive black "enclave," it has been rumored that Gurley was lynched by a white mob and buried in an unmarked grave. However, according to the memoirs of Greenwood pioneer, B.C. Franklin, Gurley left Greenwood for Los Angeles, California.

O.W Gurley and his wife, Emma, moved to a 4-bedroom home in South Los Angeles and ran a small hotel. Gurley died from arteriosclerosis and a cerebral hemorrhage, in Los Angeles, California, on August 6, 1935, at the age of 67. His widow Emma passed away three years later, in 1938. (Source: Wikipedia)

BLACK PARAPHERNALIA DISCLAIMER

IMAGES FROM GOOGLE IMAGE

#black paraphernalia#black wall street#O.W. Gurley#black wealth#how greenwood got started#did you know

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

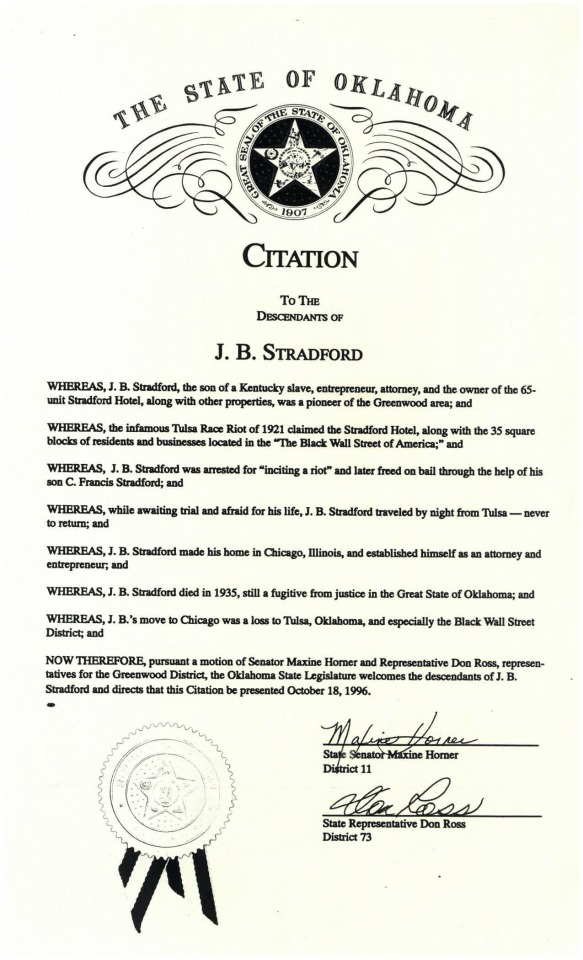

Black History Month Spotlight: J.B. Stradford

John B. Stradford (J.B.) was born in 1861 in Versailles, Kentucky to J.C. Stradford, a former slave. J.B. attended the Oberlin Preparatory Department (much like a modern day high school or secondary school) from 1882-85 and did not graduate. He went on to attend the Indianapolis School of Law, graduating in 1899.

Soon after receiving his law degree, J.B. Stradford had multiple interests in the social growth of Black Americans and Native Americans, real estate, and the oil boom in America. This led him to Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was admitted to the Oklahoma bar after arriving around 1899.

Not long after Stradford made his way to Tulsa, O.W. Gurley began developing an area in Tulsa for Black owned businesses, naming the main avenue “Greenwood.” Greenwood would soon be known as Black Wall Street, allowing Black citizens to participate in the American dream and grow their businesses and their wealth.

Stradford’s interest in real estate led him to build an over 50 room hotel on Greenwood Ave. in Tulsa, and it was the largest Black owned and Black operated hotel at the time. Stradford also owned the Stradford Library and the Stradford Building in the Greenwood area.

Unfortunately, racial tensions were growing in the south and struck Tulsa on May 30, 1921, when a Black man was accused of assaulting a white woman. This accusation has never been proven, but was enough for a fight to break out that evening. On June 1, white mobs descended on Greenwood, burning buildings and even dropping bombs from airplanes. Stradford’s businesses and real estate were destroyed, along with most of the Greenwood area.

Stradford was arrested for inciting violence during the race riots, and his son, C.F. Stradford (Oberlin College A.B. 1912) filed a writ for his release. J.B., fearing for his life, never paid bail upon release and escaped, eventually settling in Chicago and never returning to Tulsa. He died in 1935

Thanks to the efforts of J.B. Stradford’s family, including his granddaughter Jewel (Stradford) LaFontant-MANkarious (Oberlin College A.B. 1943), a Tulsa jury found Stradford innocent of all charges for inciting a riot, and Oklahoma governor Frank Keating gave Stradford a posthumous executive pardon in 1996.

(Citation given to the Stradford family, recognizing J.B. Stradford’s achievements on the day of his executive pardon, October 18, 1996. From the Jewel LaFontant-MANkarious papers, Oberlin College Archives)

More information about the notable Stradford family can be found in the papers of Jewel LaFontant-MANkarious, held in the Oberlin College Archives. Jewel’s own career as a lawyer, United Nations Ambassador, and other United States government positions is well documented in the collection

#Oberlin#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Archives#Oberlin College Libraries#JB Stradford#Stradford Family#Black Wall Street#Tulsa#Greenwood#Archives#Oklahoma

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bombing of Black Wall Street

O.W. Gurley

On the night of May 13th, 1985, as Derek Davis has so eloquently documented in previous issues of The Chiseler, the Philadelphia Police Department dropped a packet of C4 explosives onto the West Philly house occupied by MOVE, a black radical group whose sociopolitical agenda was fuzzy at best. You should read Davis’ stories to more fully understand how and why this came to pass, but suffice it to say in the end eleven people in the house (including several children) were killed, and some sixty surrounding homes—an entire city block’s worth—were allowed to burn to the ground.

At noon on September sixteenth, 1920, a group of anarchists detonated a horse-drawn cart packed with explosives and shrapnel in the middle of Wall Street, killing thirty-eight capitalists and sending hundreds more to area hospitals.

Nine months after the Wall Street bombing and sixty-four years before MOVE, an incident which in a way echoed both events took place in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but with far more devastating results. The Bombing of Black Wall Street, as it was sometimes known, would go on to be just as forgotten, at least in white history books, as both the MOVE and Wall Street bombings.

In 1906, a wealthy black entrepreneur named O.W. Gurley moved from Arkansas to Tulsa, where he bought up forty acres of land on the northern outskirts of the predominately white town. He had a plan in mind, and would only sell parcels of the land to other African-Americans, especially those trying to escape the brutal economic conditions in Tennessee.

Within a decade, the resulting thirty-four square block community, which had been dubbed Greenwood, had evolved into one of the most affluent regions of the state, and certainly the wealthiest and most successful black-owned business district in the country. A few of the new residents had even struck it rich when oil was discovered nearby. Along with the grocery, clothing and hardware stores that lined the main commercial strip, Greenwood boasted its own schools, churches, doctors, banks, law offices, restaurants, movie theaters, a post office and a public transportation system. The houses had indoor plumbing, and, even that early in the history of aviation, six of the residents owned private airplanes. Thanks to Segregation laws which prohibited blacks from shopping in nearby Whites-Only stores, the African-American residents of Greenwood shopped at their own local stores, which kept money circulating in the community, only bolstering their economic strength.

By all accounts, the people who lived there were extremely proud of what they had forged, especially the school system, insisting each and every child of Greenwood receive a full and solid education.

Although generally referred to as “Little Africa” or “Niggertown” in the Tulsa Tribune, Tulsa World, and other local papers, the residents of Greenwood preferred to think of it as Black Wall Street, a nickname that has stuck to this day.

As you might imagine, the much poorer white residents in surrounding Tulsa resented the wealth and success of their black neighbors. This resentment was only fueled by the local papers, in particular the Tribune. Taking their lead from the local chapter of the Klan, more often than not the Tribune’s writers insisted, despite all evidence to the contrary, on caricaturing the residents of “Little Africa” as either stupid, shiftless, shuffling drunks or drug crazed, wild-eyed criminals and rapists running wild in the streets. Meanwhile, editorial writers over at the World even recommended conscripting the Klan to restore law and order to the community.

Combining the reality with the grotesque cartoon proved to be a poor white racist’s worst nightmare. Not only were those blacks in Greenwood subhuman, they were rich subhumans. Jesus God Almighty!

The simmering anger reached the boiling point on May 30th, 1921 when seventeen-year-old (and white) Sarah Page accused nineteen-year-old (and black) shoeshine man Dick Rowland of rape. Page worked as an elevator operator in Tulsa’s Drexel Building, and claimed Rowland attacked her while she was on the job. No one really knows to this day what happened in that elevator, but later investigators who’ve looked into the case genrtally agree there was no rape. Rowland would claim he either bumped into Page accidentally or stepped on her foot—he couldn’t remember. At the time it didn’t matter. The following morning’s Tribune ran a racially inflammatory, lurid account of the fictional crime in which they essentially declared Rowland guilty. A hearing was scheduled for that afternoon, and the paper further erroneously reported the gallows was already being built outside the courthouse for that night’s hanging.

Whether or not a rape had occurred was, to be honest, irrelevant. It was simply the easiest and cheapest way to rile up the angry white masses. If the paper had run an article about economic disparity and racial class resentment turned on its head, all it would have encouraged its white readers to do is flip forward to the sports section.

The residents of Greenwood understood this, and on the 31st, the day of the hearing, a group of men, some of them armed, showed up outside the courthouse in hopes of protecting Rowland. When they arrived they found themselves facing off with the much larger (and better-armed) angry white mob, there to ensure Rowland was hanged, trial or no trial.

Words were exchanged and a few scuffles broke out. A white man reportedly approached an armed African-American WWI vet, and demanded he hand over his gun. When the vet refused and the white tried to wrest it from him, the gun went off, and the riot was underway.

Realizing they were outnumbered, the mob from Greenwood retreated towards home, only to be pursued by the white mob, both on foot and in pickups.

It’s worth noting that the confrontation outside the courthouse had gone on for several hours before the few cops onhand to keep the peace finally called for backup. When all hell broke loose after that gunshot, the cops quickly began deputizing whites on the fly, giving them the authority to make arrests. A few did, and an internment camp set up at the local fairgrounds quickly began to fill. Most of the new deputies didn’t bother, and just started shooting.

As the white mob entered Greenwood, they immediately began looting and torching every building they passed. For the next twelve hours they rampaged through the neighborhood, whooping and hooting as they smashed windows, kicked in doors, took potshots at fleeing residents, and set fire to anything that wasn’t already ablaze. Several eyewitness reports claim two small planes flying over the community started dropping what some believe were kerosene bombs and others believe was dynamite on the already raging inferno. Firemen who arrived on the scene to douse the fires were turned back at gunpoint by the rioters.

The number of white families from nearby neighborhoods—a lot of mothers and children—who gathered around the edges of Greenwood to watch the carnage has led some to believe the attack was planned well in advance, likely by the Klan. They were just waiting for an excuse.

The National Guard arrived shortly before noon on June 1st, but by then most of the rioters had gone home. Along with trying to control the flames, the Guardsmen also began arresting Greenwood’s residents. By the time the fires were put out, all thirty-four square blocks of Black Wall Street had been burned to the ground. An estimated three hundred had been killed, another eight hundred hospitalized, ten thousand were left homeless, six thousand were being held in the internment camp at the fairgrounds, and six hundred businesses had been destroyed. No whites were arrested or charged for their role in the massacre.

Some of the dead, it was reported, were buried in mass graves, others dumped in a nearby river, and still others dropped into the shafts of a local coal mine.

The coverage of the destruction of Black Wall Street in the following day’s Tulsa World included the headlines “Fear of Another Uprising” and “Difficult to Check Negroes.” To this day, white media outlets continue to refer to the incident as “The Tulsa Race Riot,” when they refer to it at all. The Tribune quietly removed the front page story about the alleged rape from all their bound editions, and all police and fire department files about the incident mysteriously vanished.

The day after the riot, all charges were dropped against Dick Rowland (who had been safely hidden away in a jail cell throughout it all), and upon his release he quickly and quietly left town.

Only one of Black Wall Street’s buildings was left standing, and those who survived vowed they would rebuild. They did, too, to an extent, but they were never able to fully reclaim the spirit and status the community once had. Making things more difficult, Greenwood was in a prime location in terms of business expansion. City politicians, anxious to reclaim that land, began devaluing Greenwood property, hoping they might encourage residents to sell out and move far away.

Ironically, the real death blow to Black Wall Street came when Segregation was overturned in Oklahoma in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and most Greenwood residents decided they were happy to take their business to formerly whites-only stores.

Seventy-five years after the massacre, the state of Oklahoma ordered an investigation into the events of May 31st-June 1st, 1921. When the investigation ended in 2001, it was suggested a scholarship fund be set up, and reparations be paid to the families of the victims. A few scholarships were handed out before the program was discontinued three years later, but no reparations were ever paid.

by Jim Knipfel

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

[May] sees the release of Across the Tracks, a graphic novel written by Alverne Ball & illustrated by Stacey Robinson. This non-fiction graphic novel tells of the founding of Greenwood, Oklahoma, a prosperous Black community, and how its business district became “The Black Wall Street” of America. This success story in Jim Crow America did not go unnoticed. From May 31 to June 1, 1921 a white mob murdered 300 Black men, women, and children and razed Greenwood to the ground.

Unlike previous works, though, Across the Tracks spends most of its 60-some pages on what precipitated the massacre. The book is more concerned with naming the men and women who made Greenwood what it was: O.W. Gurley, John Wesley and Loula Tom Williams, and J.B. Stradford. In this way, Across the Tracks not only personalizes and therefore heightens the tragedy we know will come, but it also reframes that tragedy. Black perseverance and joy take center stage in a way it seldom does when discussing Greenwood. This story is about Greenwood, not Tulsa and the race massacre, a deliberate choice on Ball and Robinson's end.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Black Wall Street: History of Greenwood District Where 108 Black Business were established, including 2 newspapers, 41 groceries and meat markets, 30 cafes and restaurants

The Greenwood District located in Tulsa, Oklahoma became one the most prosperous Black communities in the U.S. during the early 1900s. The area was known as the “Negro Wall Street” by educator Booker T. Washington, this community had a population that included working class and a middle class of prosperous citizens.

Once the Civil War ended, majority of all-Black towns were located in Indian and Oklahoma Territories. Greenwood was established in 1906 by one of Tulsa’s earliest pioneers, O.W. Gurley, who had come from Arkansas to Oklahoma in the 1889 Land Rush. A Black educator and entrepreneur who gained wealth by speculating on land, Gurley was able to purchase forty acres on the northern outskirts of Tulsa. The land itself had been incorporated only eight years earlier in 1898. Gurley sold his land to African Americans who developed a small community. Tulsa would grow quickly because of the oil boom in the surrounding countryside and by 1910 annexed Greenwood.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Greenwood appealed to Black Americans who hoped of escaping the political, social and economic oppression in the deep south. There were 108 Black businesses, which included two newspapers, 41 groceries and meat markets, 30 cafes and restaurants according to 1920 directories.

According to 1920 city directories, there were 108 black business establishments, including 2 newspapers, 41 groceries and meat markets, 30 cafes and restaurants. There were offices for 33 professionals, including 15 physicians and attorneys in Tulsa’s all-Black community serving the approx. 10,000 residents. The afro mentioned Black wall street, Deep Greenwood had clothing stores, funeral parlors, billiard halls, hotels, barbershops, hairdressers, shoemakers, tailors, nightclubs, and two movie theaters. Because most white establishments refused to serve African Americans, black entrepreneurs held a captive market rich in pent-up demand.

By 1920 they had twenty-two churches and was a center for jazz and blues music. The schools in Greenwood were described as exceptional compared to those in the “white” areas of town. Greenwood, as it was now often called, was further advanced economically than some of the white areas of Tulsa.

On May 31, 1921 the Tulsa Riot started and estimated killed 300 black men, women, and children. While thousands were severely injured. Most of the thirty-five square blocks of Greenwood included businesses and residential neighborhoods were destroyed by white rioters and nearly 10,000 thousand African Americans, almost the entire black population of Tulsa, was left homeless.

After the riot the city of Tulsa denied aid to the survivors of the riot. However, the African-American businessmen and residents of Greenwood used their own resources and help sent from across the United States to rebuild the town. By the summer of 1922, more than eighty businesses were again up and running.

The Tulsa Riot of 1921, although a major setback for Greenwood, was not the event that caused the decline in Greenwood’s economy. The national Civil Rights movement 1960s which led to Civil Rights Act of 1964. As African Americans began to use businesses and accommodations throughout Tulsa and move throughout the city, the Greenwood businesses began to decline. Urban renewal and freeway construction in Tulsa in the 1960s and 1970s accelerated that process.

Today due to Urban Renewal bulldozers much of Greenwood is flattened. However in 1965, Edward Goodwin Sr., founder of The Oklahoma Eagle newspaper, opted to purchase a few spared blocks of land in order to preserve some of Greenwood’s history. Goodwin would build the Greenwood Cultural Center and rehabilitating the block of land into cultural center.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

1:00 - “The creation of the powerful Black community known as Black Wall Street was intentional. In 1906, O.W. Gurley, a wealthy African-American from Arkansas, moved to Tulsa and purchased over 40 acres of land that he made sure was only sold to other African-Americans.”

1:42 - “Another important visionary who contributed to the success of Black Wall Street was Mr. J.B. Stratford. J.B. Stratford had graduated from Indiana University with a law degree and had moved to Greenwood to purchase various land vacancies in the area. After buying these vacant spaces, he would then sell them to African-American residents for redevelopment so that the empty spaces could be transformed into residential houses and profitable businesses.”

3:16 - “A dollar circulated 36 to 100 times, and remained in the Greenwood district almost a year before leaving. To this day, no other community has been able to duplicate that type of circulation.”

3:48 - “Although it [Greenwood] wasn’t the only one; there were prominent Black business districts in Durham, North Carolina, Richmond, Virginia and Rosewood, Florida, the people of Greenwood achieved a level of Black economic success and self-determination that had NEVER existed before in the United States, less than 60 years removed from slavery.”

4:03 - “Despite racial discrimination and Jim Crow segregation, the Greenwood district offered proof that Black entrepreneurs were capable of creating abundant wealth. WHEN LEFT ALONE, OUR ANCESTORS THRIVED.”

4:26 - “In the entire state of Oklahoma, there were only 2 airports, yet 6 Black families owned their own private planes in the Black Wall Street district.”

4:58 - “Many of the homes had indoor plumbing before those in the white area did...What made Black Wall Street special is that it was a place where an ordinary Black person could go and have a respectable life.”

6:06 - “The average income of Black families in the area EXCEEDED what the minimum wage is TODAY...Many of the residents lived in luxury,and had access to many luxuries that many whites in the same city did not.”

7:19 - “White people routinely borrowed money from Black banks, and this was even done during the Great Depression.”

#Black Wall Street#A Case for Segregation#Time for a BLEXIT#A Black exit from mainstream American society\#Which is an exit from our most longstanding oppressors--THE BRITISH#Black Liberation Struggle

1 note

·

View note

Text

Black History Month: Day 19 - Tulsa's Black Wall Street

Travelbox explores the story of Tulsa's Black Wall Street. Now available! #blackhistorymonth #THC

In the early 1900s, Tulsa Oklahoma was home to a prosperous African district known as Greenwood. This district was so successful that a dollar would stay within the district an estimated nineteen months before being spend elsewhere. Home to many successful black businesses, the “colored district” of Tulsa was much more prosperous than its white counterpart across the tracks prior to 1921.…

View On WordPress

#Archer#Black History Month#Black Wall Street#entrepreneurs#Gap Band#Greenwood#J.B. Stradford#James Henri Goodwin#O.W. Gurley#Oklahoma#Pine#professional#prosperity#racism#riot#Simon Berry#THC#Tulsa

0 notes

Photo

June 1st, 1921 will forever be remembered as a day of great loss and devastation. It was on this day that America experienced the deadliest race riot in the small town of Tulsa, Oklahoma. 97 years later, that neighborhood is still recognized as one of the most prosperous African American towns to date. In the early 1900s, many African Americans migrated from southern states hoping to escape the harsh racial tensions while profiting off of the oil industry. Yet even in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Jim Crow laws were at large, causing the town to be vastly segregated. From that segregation grew a Black entrepreneurial mecca that would affectionately be called “Black Wall Street”. The town was established in 1906 by entrepreneur O.W. Gurley, and by 1921 there were over 11,000 residents and hundreds of prosperous businesses, all owned and operated by Black Tulsans and patronized by both whites and Blacks. The attack that took place in 1921 (motivated largely by jealousy and an unconfirmed sexual assault accusation made by a white woman against a Black man) tore the community apart, claiming hundreds of lives and sending the once prosperous neighborhood up in smoke. Read more at: www.officialblackwallstreet.com/black-wall-street-story

503 notes

·

View notes