#Nunalleq

Photo

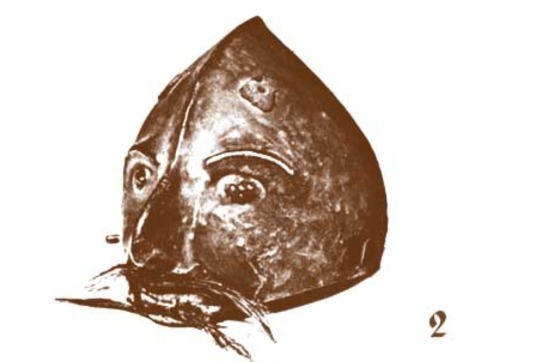

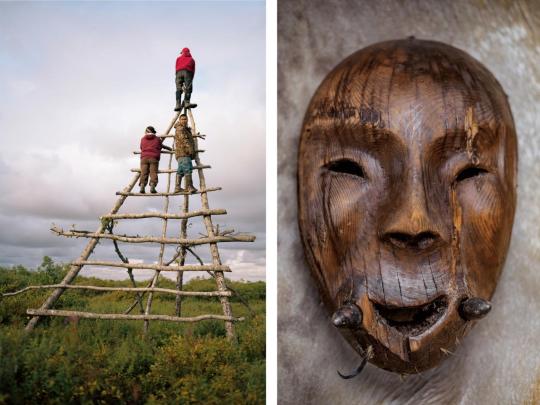

Frozen in time: Archaeologists have retrieved 100,000 artifacts from Nunalleq, in southwestern Alaska. Everything from ivory tattoo needles and a belt of caribou teeth to wooden ritual masks. Most artifacts are well-preserved, having been frozen underground since 1660. Now archaeological sites such as Nunalleq are threatened by climbing temperatures and rising seas. (Pictured above, Yup’ik masks depicting a half-human, half-walrus face, and one from the 19th century resembling an animal with a seal in its jaws.)

LEFT: ERIKA LARSEN/NG IMAGE COLLECTION;

RIGHT: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

#erika larsen#ng image collection#photographer#national museum of the american indian#smithsonian institution#history#culture#archeology#nunalleq#alaska#ritual masks#yup'ik masks#national geographic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Survive the Little Ice Age

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

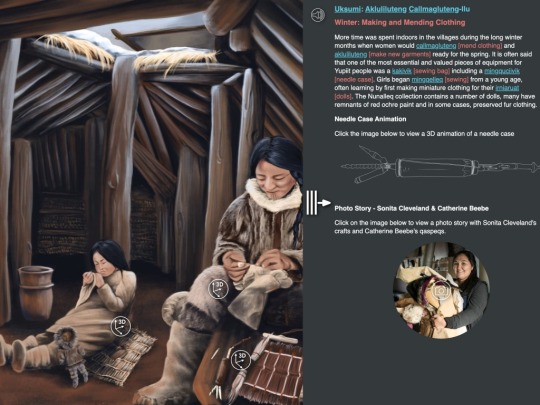

Digital Museum lets visitors explore Yup'ik life in the past with help from local community today

Extraordinary archaeological discoveries from a frozen 16th century Alaskan village on the shores of the Bering Sea can now be viewed online for the first time.

The Nunalleq Digital Museum and Catalogue features some 6,000 everyday objects found over a decade of excavations near Quinhagak in western Alaska, including dolls, ceremonial dance masks, jewellery, cooking utensils and sewing tools.

Meaning ‘the old village’ in Yup’ik, Nunalleq is a site dating from 1570-1675 AD. The permafrost has preserved tens of thousands of rarely seen artefacts from wood and other organic materials, and the collections ranks as one of the largest and best-preserved in the world.

Using artists reconstructions and 3D scans, the new resource brings to life Yup’ik life in the past, as told by the Quinhagak community in the present, with visitors able to cycle through the seasons and discover what village life was like before the Euro-American colonisation of Alaska.

The project is a collaboration between the University of Aberdeen, the 3DVisLab at the University of Dundee and Qanirtuuq Village Corporation in Quinhagak, Alaska. It has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Dr Charlotta Hillerdal, lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen, said: “The Digital Museum is the latest step in a long-term relationship between researchers and residents of the Native Alaskan village of Quinhagak who first contacted us in 2009 to carry out a rescue dig after seeing their coastline being washed away due to global warming.

“The physical collection of around 100,000 objects is housed in the village’s Nunalleq museum under the curatorial care of the descendant community but its remote location makes it accessible to only a limited number of visitors.

“This unique digital resource gives worldwide access to these important artefacts, alongside reconstructed scenes of life in the area in the 1600s which integrate the crucial Yup’ik perspective into the archaeological interpretations.”

#Nunalleq#museum#Alaska#history#university of aberdeen#aberdeenuni#universityofaberdeen#Archaeology#digital museum#artefacts

0 notes

Text

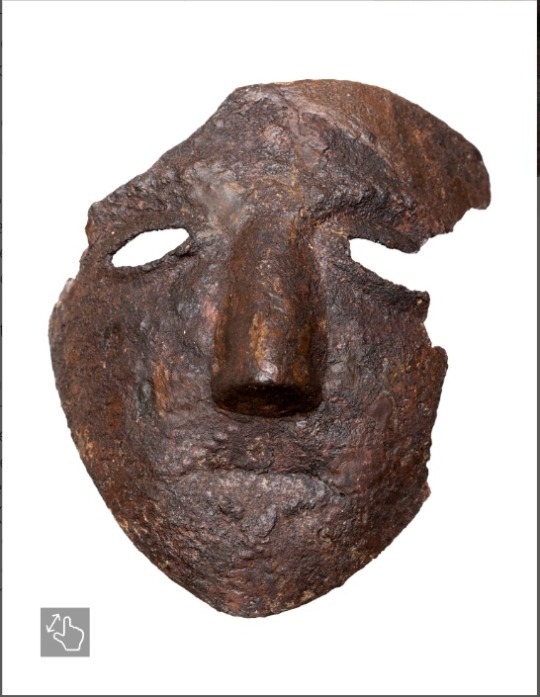

Everything that is not bare skull tends to be perceived as "grotesque" now, even funny. Now it's only functional, as a warning sign on the electric post. Although functionality can be a passion too.

But here the reasons and emotions might be less plain.

The forest where to live.

The face.

to see through the brows <>

[precontact Yup'ik, Nunalleq site (16th–17th century AD) near the village of Quinhagak, Alaska]

0 notes

Text

A Dart in a Boy's Eye May Have Unleashed This Legendary Massacre 350 Years Ago

Archaeologists have uncovered a 350-year-old massacre in Alaska that occurred during a war that may have started over a dart game. The discovery reveals the gruesome ways the people in a town were executed and confirms part of a legend that has been passed down over the centuries by the Yup'ik people.

A recent excavation in the town of Agaligmiut (which today is often called Nunalleq) has uncovered the remains of 28 people who died during the massacre and 60,000 well-preserved artifacts.

Agaligmiut had a large interconnected complex that was designed to make defense easier, said Rick Knecht and Charlotta Hillerdal, both archaeology lecturers at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland who are leading the team that is excavating the site. "We found that it had been burned down and the top was riddled with arrow points," Knecht told Live Science. Read more.

372 notes

·

View notes

Link

This small mask was found on a side room house floor. We think that this floor may be among the first deposited within this year’s excavation block. This year we have more than doubled the combined total of the masks recovered during the previous six field seasons.

Here is a complete kayak bow piece. It was found in the corner of the house and had been used as a gaming dart target. One gaming dart, complete with bone point was found next to it.

A hafted ground slate uluaq and a pendant made from a beluga tooth.

A fragment of what appears to be a bentwood visor, with a portion of the original surface painting still intact. Like many pieces from this level, the wood is still bright.

231 notes

·

View notes

Link

A huge collection of artefacts 'frozen in time' which offer a unique insight into the indigenous people of Alaska will be returned to the region by the University of Aberdeen.

Archaeologists from the Scottish University have spent more than seven years painstakingly recovering and preserving everyday objects that indigenous Yup’ik people used to survive and to celebrate life – in a race against the clock before melting ice and raging winter storms reclaim the Nunalleq archaeological site.

Dating back more than four centuries, their finds include wooden ritual masks, ivory tattoo needles, and even a belt of caribou teeth, all preserved in ‘extraordinary condition’.

Dr Rick Knecht, from the University of Aberdeen, is leading the project. He said: “The unique conditions in this arctic region mean artefacts which are more than four centuries old have retained an unbelievable level of detail.

“We have uncovered grass baskets and mats made when Shakespeare walked the earth but when we take them out of the ground the grass weaving still retains a trace of its green colour and we have been amazed by the variety and intricacy of the woven patterns.”

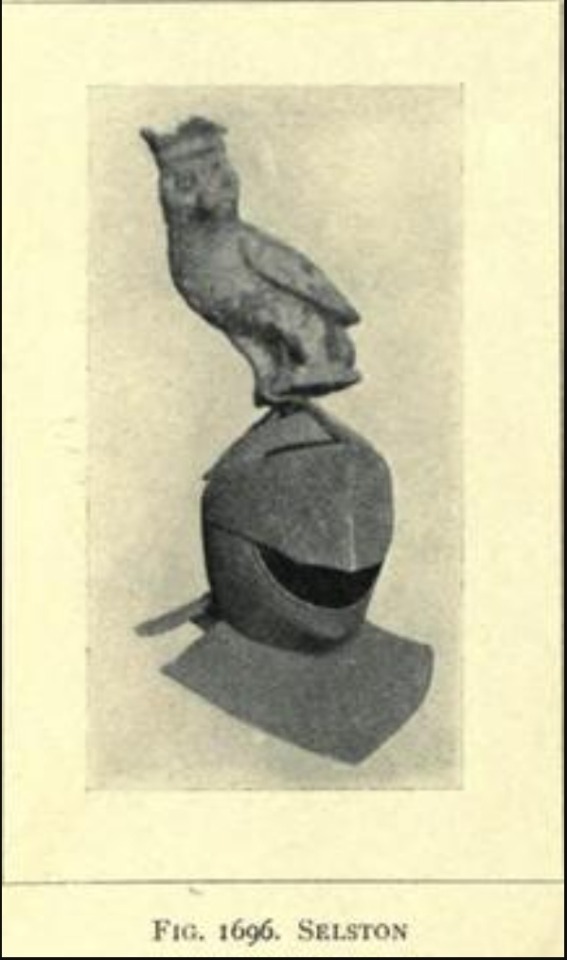

This owl figurine has ivory eyes

Once removed from the earth, however, the artefacts begin to deteriorate quickly and it is for this reason that Dr Knecht and his team have now transported more than 50,000 items to the University of Aberdeen, where professional conservators oversee preservation treatments on the items.

“When we began the project, it was impossible to conduct conservation work on site and the items recovered were transported, some still covered in earth, to Aberdeen.

“The long-term goal, however, has always been to return them to where they belong and that will become possible later this year with the opening of the new Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Research Center.

“We are now working in partnership with the local Qanirtuuq Corporation and the village of Quinhagak, located just two miles from the dig, to make arrangements for the safe return of the collection and as part of our work this season we will be training local people on the conservation techniques which have been honed in Aberdeen.

“This is one of the largest collections ever recovered from a single site Alaska, and perhaps even the whole Arctic region and is of huge significance as it now accounts for more than 90 per cent of everything we know about pre-contact Yup’ik, one of the major indigenous groups in North America.

“We hope that from this summer onwards the vast majority of conservation work can be done right in the village of Quinhagak.”

The findings of the archaeologists have also revealed for the first time evidence of a period referred to in oral tradition as the ‘Bow and Arrow Wars’, when Yupik communities fought each other in bloody battles sometime before Russian explorers arrived in Alaska in the 1700s.

A collection of wooden masks was discovered at Nunalleq

“Nunalleq offers the first archaeological evidence, and the first firm date, for these terrible wars, which affected several generations of Yupiit,” Dr Knecht added.

“It seems likely these attacks were associated with climate change—a 550-year chilling of the Earth now known as the Little Ice Age—that coincided with Nunalleq’s occupation. The coldest years in Alaska, in the mid-1600s, may have been a desperate time, with raids probably launched to steal food and take over hunting and fishing territory.

“Whenever you get rapid change, there’s a lot of disruption in the seasonal cycles of subsistence. If you get an extreme, like a Little Ice Age—changes can occur faster than people can adjust.

“Oral testimonies passed down from generation to generation speak of the horror of these wars and the archaeological evidence strongly supports this. We have unearthed the remains of women children and elders together which suggests that they were captured and killed. These were recorded and turned over to the village for reburial.

“It is important their stories are told and we are delighted to be working with the Nunalleq community to ensure that these vital artefacts related to their lives can be shared in the place they belong.”

Warren Jones, president of the local Yupik corporation known as Qanirtuuq, Inc. which manages 130,564 acres was influential in encouraging Dr Knecht and his team to excavate the area.

He envisages the center, with these collections at its heart, as a place where people can see, touch, and share stories about the beautifully worked possessions of their ancestors.

“I want our kids who are in college now to run it and be proud that it’s ours,” he said. “And when this dream takes shape and the center opens its doors, I want to be the first to go in and say, ‘I’m Yupik, and this is where I come from.’ ”

#archaeology#history#native american#yupik#alaska#nunalleq#Yupiit#Quinhagak#Aberdeen#arctic#Yup’ik#indigenous

167 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yup’ik carved wooden artifacts, ~AD 1600, Nunalleq, Alaska

#yup'ik#nunalleq#indigenous peoples#native american archaeology#alaskan archaeology#university of aberdeen#inuit

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A mask belonging to the Yup’ik people of Alaska emerging from the permafrost. It is one of more than 100,000 artifacts retrieved from Nunalleq, the site of a village that was attacked by rivals 350 years ago.

Credit...University of Aberdeen

340 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@UoA_Archaeology: 1st #findoftheday from #Nunalleq 2018 (3/7) - a walrus ivory fish lure, with some original red ochre pigment still intact #alaska #yupik https://t.co/09Zil1ZKha

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

10,000-year-old dog remains from Alaska hint at a beautiful tale of migrating together

https://sciencespies.com/humans/10000-year-old-dog-remains-from-alaska-hint-at-a-beautiful-tale-of-migrating-together/

10,000-year-old dog remains from Alaska hint at a beautiful tale of migrating together

A tiny, ancient bone fragment found in Southeast Alaska is a lot more than meets the eye. It belonged to a dog that lived in the region 10,150 years ago, which means it’s a piece of the puzzle of dog migration into the Americas – and the humans that likely came along with it.

Scientists have sequenced the DNA found in the bone, positively identifying the animal. This makes it the oldest confirmed dog remains in the Americas, the researchers said.

“There have been multiple waves of dogs migrating into the Americas, but one question has been, when did the first dogs arrive? And did they follow an interior ice-free corridor between the massive ice sheets that covered the North American continent, or was their first migration along the coast?” said evolutionary biologist Charlotte Lindqvist of the University of Buffalo.

“We now have genetic evidence from an ancient dog found along the Alaskan coast. Because dogs are a proxy for human occupation, our data help provide not only a timing but also a location for the entry of dogs and people into the Americas. Our study supports the theory that this migration occurred just as coastal glaciers retreated during the last Ice Age.”

(Douglas Levere/University at Buffalo)

The fragment of bone, named PP-00128, was actually found quite some time ago, during excavations of Lawyer’s Cave on the Alaskan coastal mainland in 1998 and 2003. Hundreds of bone samples and some human artefacts were collected in those excavations, and the fragment had been sitting in storage awaiting further examination.

Initially, scientists thought it was a fragment of bear bone – which would help put together a picture of the cave’s usage throughout the millennia, but is not quite as relevant to human history.

It wasn’t until Lindqvist and her team took a closer look at the mitochondrial DNA that they realised this supposition was – excitingly – very incorrect. The fragment, a piece of the rounded head of a femur about 1 centimetre (0.4 inches) across, belonged to a canine lineage that split from Siberian dogs around 16,700 years ago (Canis lupus familiaris).

This now almost completely extinct lineage, known as precontact dogs because they predate European contact in the Americas, went on to populate North America alongside indigenous humans. The branch of this precontact dog family tree that produced the owner of the PP-00128 bone sample split away around 14,500 years ago.

The DNA also revealed that the dog likely fed mainly on seafood, similar to dog remains found in Nunalleq, a precontact Yup’ik archaeological site in coastal Southwestern Alaska. In both cases, it’s easy to imagine that the dogs fed on fish, seal and whale meat hunted and caught by their human companions.

Put all together, the evidence suggests that the region may be a significant one for the history of human migration into the Americas.

“This all started out with our interest in how Ice Age climatic changes impacted animals’ survival and movements in this region,” Lindqvist said.

“Southeast Alaska might have served as an ice-free stopping point of sorts, and now – with our dog – we think that early human migration through the region might be much more important than some previously suspected.”

It only constitutes a piece of the puzzle. Humans entered the Americas several times over the millennia, bringing different dogs with them (because who would leave their puppy behind?). But it could be a very important piece.

“Our early dog from Southeast Alaska supports the hypothesis that the first dog and human migration occurred through the Northwest Pacific coastal route instead of the central continental corridor, which is thought to have become viable only about 13,000 years ago,” said biologist Flavio Augusto da Silva Coelho of the University at Buffalo.

Precontact dogs were later almost entirely replaced by Inuit sled dogs and European breeds that arrived with the colonists, so studying remains such as PP-00128 could also help us understand the fate of the entire lineage.

The research has been published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

#Humans

0 notes

Photo

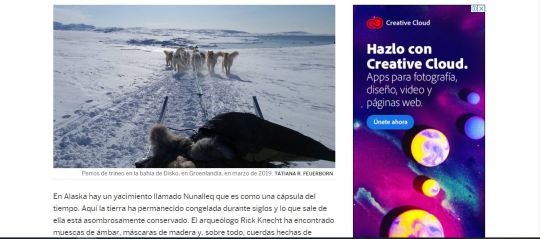

Esta nota se relaciona con la biologia ya que nos habla de el origen de una especie que son los perros. La nota nos dice que en Alaska hay un yacimiento llamado Nunalleq que es como una cápsula del tiempo. Aquí la tierra ha permanecido congelada durante siglos y lo que sale de ella está asombrosamente conservado. El arqueólogo Rick Knecht ha encontrado muescas de ámbar, máscaras de madera y, sobre todo, cuerdas hechas de hierba seca que fue cortada hace más de 400 años o, como él dice, cuando Shakespeare aún andaba sobre la Tierra.Esas cuerdas hablan de uno de los capítulos más duros y desconocidos de la expansión de los humanos por el planeta. Hace unos 2.000 años, los esquimales —un grupo de cazadores nómadas de Siberia— se lanzaron a la conquista del Ártico llegando primero a Alaska y después desplazándose por la costa este de Canadá y hasta Groenlandia, donde llegaron hace unos 800 años.

0 notes

Text

Artifact of the Month: Owl Effigy, Togiak

Owl carved masks, dance fans and painted designs are associated with aspects of Yup’ik traditions in southwest Alaska. The effigy featured this month was found near the village of Togiak. Located in upper Bristol Bay, Togiak is a Yup’ik village with a long history in the area. Local owl species include snowy owls, northern hawk owls, short-eared owls, boreal owls, great grey owls and great horned owls. Owls are rarely used as a food source, rather they are reserved for starvation times because of their plentifulness and rich meat.

Owl Effigy from the Togiak region in Alaska.

The owl depicted in this effigy, is likely a great horned owl because of its ear-like features. There are round circles for eyes on both sides of the owl’s head. The design is reminiscent of the ellam iinga motif style. Ellam innga, referred to as the circle-and-dot motif, represents the conceptual symbols of Ellarpak [awareness; the universe]. These designs are associated with religious symbols on objects like drums or as familial ownership designs on pottery or kayaks.

Owl Effigy from the Togiak in Alaska.

Adjacent to Togiak is the excavation of Nunalleq. Owl images are regularly located at Nunalleq including effigies, masks and atlatl weights. Like Togiak, Yup’ik ancestors inhabited the village of Nunalleq around 1,000 BP to present. However, some Bristol Bay villages date much older like the 6,000-year-old village of Qayassiq on Round Island. Related artifacts between the three villages suggest a longer and more continuous occupation of the Bristol Bay area. As work continues to document prehistoric villages in the Bristol Bay region, owl symbolism may be found to exist even further back in the archaeological record.

Written by Dougless Skinner

Sources:

John, Theresa. 2010. Yuraryararput Kangiit-luu: Our ways of Dance and Their Meanings. Dissertation. University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Nunalleq Excavation: https://nunalleq.wordpress.com/

Togiak National Wildlife Refuge: https://www.fws.gov/refuge/togiak/

0 notes

Text

University of Aberdeen team saves 50,000 frozen Alaskan artefacts

More than 50,000 frozen Alaskan artefacts are to be returned home after being preserved by archaeologists at the University of Aberdeen.

The team has spent more than seven years recovering and preserving the objects at Nunalleq.

They faced a race against the clock in the face of melting ice to save the frozen artefacts.

Once removed from the earth, they began to deteriorate quickly so the team had to act quickly.

The collection is thought to be one of the largest of its kind from a single site in Alaska.

The items will be sent back to Alaska for the opening of a new culture and archaeology centre. Read more.

615 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Photos: Evidence of a Legendary Massacre in Alaska | Live Science

In Photos: Evidence of a Legendary Massacre in Alaska | Live Science

Tens of thousands of artifacts and the remains of 28 human bodies reveal details of a massacre in the village of Nunalleq.

— Read on www.livescience.com/65287-photos-legendary-massacre.html

View On WordPress

#Alaska#culture#genocide#Indigenous massacre#mass murder#murder#racial profiling#racism#racist violence#rape#terrorism#white supremacy

0 notes

Link

The archaeological site of Nunalleq on the southwest coast of Alaska preserves a fateful moment, frozen in time. The muddy square of earth is full of everyday things that the indigenous Yupik people used to survive and to celebrate life here, all left just as they lay when a deadly attack came almost four centuries ago.

Around the perimeter of what was once a large sod structure are traces of fire used to smoke out the residents—some 50 people, probably an alliance of extended families, who lived here when they weren’t out hunting, fishing, and gathering plants. No one, it seems, was spared. Archaeologists unearthed the remains of someone, likely a woman, who appears to have succumbed to smoke inhalation as she tried to dig an escape tunnel under a wall. Skeletons of women, children, and elders were found together, facedown in the mud, suggesting that they were captured and killed.

As is often the case in archaeology, a tragedy of long ago is a boon to modern science. Archaeologists have recovered more than 2,500 intact artifacts at Nunalleq, from typical eating utensils to extraordinary things such as wooden ritual masks, ivory tattoo needles, and a belt of caribou teeth. Beyond the sheer quantity and variety, the objects are astonishingly well preserved, having been frozen in the ground since about 1660.

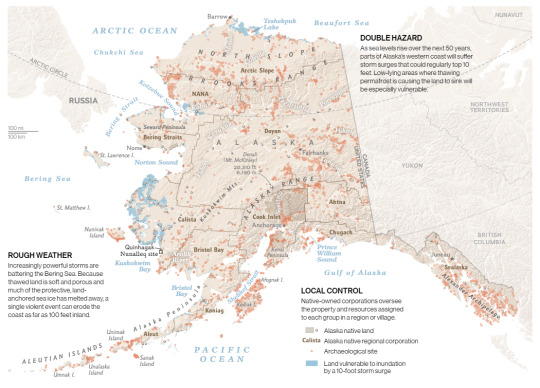

Emma Frances Echuck and her daughter Valerie take a break from drying salmon in the village of Quinhagak. At a nearby archaeological site artifacts such as this mask are emerging from the permafrost as it thaws.

The remains of baskets and mats still retain the intricate twists of their woven patterns. Break open a muddy, fibrous bundle and you’ll find crisp, green blades of grass preserved inside. “This grass was cut when Shakespeare walked the Earth,” marvels lead archaeologist Rick Knecht, a quiet, grizzled veteran of decades of digging.

Knecht, who’s based at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, sees a link between the destruction at the site and the old tales that modern Yupiks remember. Oral tradition preserves memories of a time historians call the Bow and Arrow Wars, when Yupik communities fought each other in bloody battles sometime before Russian explorers arrived in Alaska in the 1700s. Nunalleq offers the first archaeological evidence, and the first firm date, for this frightful period, which affected several generations of Yupiks.

Knecht believes the attacks were the result of climate change—a 550-year chilling of the Earth now known as the Little Ice Age—that coincided with Nunalleq’s occupation. The coldest years in Alaska, in the 1600s, must have been a desperate time, with raids probably launched to steal food.

“Whenever you get rapid change, there’s a lot of disruption in the seasonal cycles of subsistence,” Knecht says. “If you get an extreme, like a Little Ice Age—or like now—changes can occur faster than people can adjust.”

Today increasingly violent weather has driven Nunalleq to the brink of oblivion. In summer everything looks fine as the land dons its perennial robe of white-flowering yarrow and sprigs of cotton grass that light up like candles when the morning sun hits the tundra. But the scene turns alarming come winter, when the Bering Sea hurls vicious storms at the coast. If the waves get big enough, they crash across a narrow gravel beach and rip away at the remains of the site.

This centuries-old ulu, or cutting tool, was plucked from the thawing ground at Nunalleq. Embodying the native Yupik belief that everything is constantly in transition, the handle can be seen as either a seal or a whale.

The Arctic wasn’t always like this, but global climate change is now hammering the Earth’s polar regions. The result is a disastrous loss of artifacts from little known prehistoric cultures—like the one at Nunalleq—all along Alaska’s shores and beyond. Ötzi, the Stone Age man whose body was found in 1991 as it emerged from a receding Italian glacier, is the most famous example of ancient remains brought to light by warmer weather. But a massive thaw is exposing traces of past peoples and civilizations across the northern regions of the globe—from Neolithic bows and arrows in Switzerland to hiking staffs from the Viking age in Norway and lavishly appointed tombs of Scythian nomads in Siberia. So many sites are in danger that archaeologists are beginning to specialize in the rescue of once frozen artifacts. They’re having to make hard choices, though. Which few things can they afford to rescue? And which will they just have to let go?

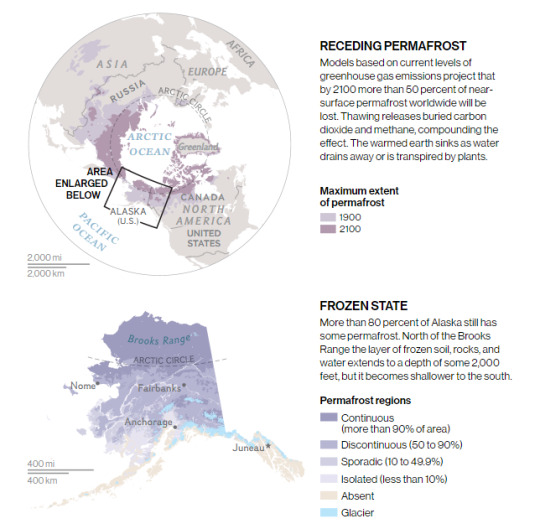

In coastal Alaska, archaeological sites are now threatened by a one-two punch. The first blow: average temperatures that have risen more than three degrees Fahrenheit in the past half century. As one balmy day follows another, the permafrost is thawing almost everywhere.

HERITAGE AT RISK

The effects of global climate change threaten hundreds of sites that hold clues to Alaska’s past. Permafrost once protected fragile artifacts from rot and mold, but warmer temperatures are now causing more and more of the icy ground to thaw in the southern part of the state. At the same time, seas are rising and winter storms are raging, putting sites all along the coast in danger.

When archaeologists began digging at Nunalleq in 2009, they hit frozen soil about 18 inches below the surface of the tundra. Today the ground is thawed three feet down. That means masterfully carved artifacts of caribou antler, driftwood, bone, and walrus ivory are emerging from the deep freeze that has preserved them in perfect condition. If they’re not rescued, they immediately begin to rot and crumble.

The knockout blow: rising seas. The global level of oceans has risen about eight inches since 1900. That’s a direct threat to coastal sites such as Nunalleq, which is doubly vulnerable to wave damage now that the thawing permafrost is making the land sink. “One good winter storm and we could lose this whole site,” Knecht says.

He speaks from experience. Since the start of the excavation, the relentless action of the sea has torn about 35 feet from the edge of the site. The winter after the 2010 dig was particularly brutal. Residents of Quinhagak, the modern village just four miles up the beach, remember huge chunks of ice slamming into the coast. By the time Knecht and his crew returned, the entire area they had excavated was gone.

Since then Knecht has pressed on with a renewed sense of urgency. Rain or shine, during the six-week dig season, about two dozen archaeologists and student volunteers spend long summer days on their hands and knees gently stripping away soil with their trowels.

When this wooden paddle blade from Nunalleq was new, people relied on kayaks to get around. Modern Yupiks use motorboats to visit other villages, hunt sea mammals, and net fish. Mike Smith (right) waded into the Kanektok River before work to hook a few salmon, which he gave to his grandmother. “She was so happy, she put on her apron right away and began cutting them up,” he says.

On an August day that begins warm and buggy but soon turns overcast and cold, Tricia Gillam finds a common artifact that was created with exceptional artistry.

It’s a women’s cutting tool popularly called an ulu—uluaq in Yupik—with a curved blade of slate and a carved wooden handle. The archaeologists often uncover a blade, a handle, or an occasional complete ulu, yet this one brings gasps from everyone. The handle has the graceful shape of a seal. But that’s only half the design, it turns out. When local carver John Smith takes a look later from another angle, he sees the outline of a whale.

The artifact speaks to the fundamental Yupik worldview that nothing is a single, inflexible entity because everything is in a state of transformation. The ulu handle is a seal, but it’s not a seal. It’s a whale, but it’s not a whale. Other finds embody that same idea: A mask that’s a walrus, or a person. A small wooden box that’s a kayak, or a seal.

“That dynamism is a constant part of their lives,” Knecht says. “And climate change is part of that.”

If anyone’s going to survive the changes occurring in the natural world, he believes, it’s these people who have always seen their environment as something fluid, requiring adjustments and adaptations. They know firsthand the seasonal patterns of plants and animals, and if there’s a shift, they’ll shift with it.

On a visit to 86-year-old Carrie Pleasant (right), Sarah Brown gets advice on sewing a beaver-skin parka. Pleasant made fur garments for all 10 of her children, but kids today usually wear store-bought clothing. “Things are changing so much,” she said wistfully. Pleasant has since passed away.

The village of Quinhagak sits on Yupik land at the mouth of the Kanektok River, which winds across the tundra in wide loops before spilling into the Bering Sea. A few gravel streets run past a school, church, post office, supermarket, hardware store, health clinic, gas station, washateria, cell phone tower, and three sleek wind turbines that spin in the brisk sea breeze.

Officially, 745 people live here, in metal-roofed, wood-frame houses that perch on stilts a foot or so above the once frozen ground. But on any given day the actual population may be larger, swelled by relatives who have come to stay for several weeks, and residents of nearby villages who have come to shop, visit friends, and maybe pull in a few fish.

Based in an office building that also serves as the archaeologists’ headquarters, 50-year-old Warren Jones is president of the local Yupik corporation known as Qanirtuuq, Inc., managing its 130,564 acres, overseeing its businesses and financial assets, and negotiating contracts with the outside world. But he’d really rather be hunting, he tells me. Along with almost everyone else here, he follows the same cycles of subsistence as the generations of Yupiks who came before him.

“Most of our diet is from the stuff we gather, hunt, or fish,” he says. “My grandpa used to say, if you don’t have wood, fish stored away, berries, birds, you might as well be dead, because you don’t have nothing.”

From a traditional lookout, hunters scan the tundra for moose. Land and sea are like supermarkets for the Yupik, who know exactly what foods to search for in each season of the year. Locals’ ancestors carved the life-size mask above. Part human and part walrus, it was worn in a ritual dance to ensure a safe, successful hunt. “Even now, with rifles, going after a walrus is scary,” says Knecht.

Early August, when the excavation is in full swing, is a busy season for the villagers as they tap nature’s larder. Berries are ripening across the tundra, and fat coho salmon, known here as silvers, are swimming up the Kanektok on their way to spawn. In keeping with Yupik tradition, Misty Matthew helps her mother, Grace Anaver, gather food for the winter.

On the days she goes berry picking, Matthew drives an ATV deep into a flat, green landscape dotted with others on the same mission, hunched over as they fill their plastic buckets. Salmonberries ripen first, one small, sweet, orange cloud per plant. Then blueberries, with a vivid, sweet-tart flavor that no supermarket fruit can match, and low-growing black crowberries that are crunchy and subtly sweet.

No one here thinks in pints. It’s gallons they need. Matthew stirs up some of her haul with sugar and fluffy shortening to make a snack called akutaq, or Eskimo ice cream. Then she makes jam in her grandmother’s old stainless steel pot, and jelly with the leftover juice. But the bulk of the picking goes into big chest freezers in a backyard shed. She opens all three to show me what her mother already has gathered. One is stuffed with berries in clear plastic bags. Another has berries, salmon, seal oil, trout, and smelt. The last holds moose, clams, geese, swans, caribou, and two kinds of wild greens.

Kids in Quinhagak, the village near the archaeological site, are growing up very differently from their parents and grandparents. Instead of hand-sewn fur parkas, they wear the same store-bought clothing as other children around the world, and English, not Yupik, is their first language. Their time is occupied not with gathering food or making tools needed for survival, but with school, television, and the Internet.

Grace Hill at first argued against digging up the place where her ancestors lived and died, but she now sees how archaeology can connect people to their past. Some Quinhagak elders believe the old site has chosen to speak today and that’s why artifacts are turning up. Quinhagak’s residents are listening—and most important, the children are learning to appreciate their cultural heritage.

In a shed where salmon fillets hang to dry, Grace Anaver pauses while cutting up the day’s catch. On a wooden table nearby, she uses her ulu to cut the head off each fish. She then slits open the belly to remove the guts and slices fillets from the ribs. Returning home for lunch, she serves broiled salmon and a soup made with salmon heads and plump sacs of orange salmon eggs.

Carver John Smith works with electric tools, but his raw materials are strictly traditional: walrus ivory like the tusks he’s carrying here, antlers from caribou, and driftwood collected on the shores of rivers and the Bering Sea. He often finds inspiration in the artifacts that the archaeologists uncover—an ivory earring with spiral motifs, a beautifully shaped ulu, or a tiny wooden owl pendant.

Out on the vast tundra, Kathy Fox shows of the crowberries she has just gathered. The fine-tooth metal cradle that she’s holding allows her to harvest a dozen or so fruits with a single swipe. Crowberries grow on the branches of ground-hugging evergreen shrubs. Pickers have to get down on their hands and knees to find the tiny berries hidden in the dense mats of sprucelike needles.

“It’s good to be fat in this village. It means you’re eating well,” she says. “You’re supposed to have three years of food stored away to get you through the lean times.”

On another day, early in the morning, Matthew and her brother, David, take out their family’s motorboat to net salmon on the river. An hour later they bring 40 silvers, easily 20 pounds each, to the wooden drying racks along a quiet side creek where their mother is waiting. The two women spend the rest of the day gutting the fish, cutting fillets, and slicing strips for brining, drying, and smoking—everything done with deft strokes of their ulus.

Like many people who grew up here, Matthew has sometimes left Quinhagak to find work, but the people, the tundra, and the river keep pulling her back. Yet even after years away, she can see that the natural rhythms of life are out of whack.

“Everything’s two or three weeks ahead now,” she says as she cuts into a fish. “The salmon are late. And the geese are flying early. The berries were early too.”

Emma Fullmoon can count on younger relatives to provide food, like this salmon. And guests are always welcome in the home she shares with extended family. “That’s just what we’re supposed to do,” says her sister Fanny Simon. Though the Yupik idea of hospitality has endured, other customs have not. The wooden figure above has large, oval lip plugs, but no one today wears such ornaments.

If there’s one thing everyone in Quinhagak agrees on, and talks about often, it’s all the changes brought by the weird weather.

“Twenty years ago the elders began to say the ground was sinking,” says Warren Jones, as we chat in his office. “The past 10 years or so it’s been so bad everybody’s noticed. We’re boating in February. That’s supposed to be the coldest month of the year.”

The strangest thing? Three successive winters without snow. On his computer, he pulls up a YouTube video made by a teacher at the village school. As the song “White Christmas” plays in the background, fourth graders try to ski, sled, and make snow angels on bare ground, in December.

This angled piece of wood once formed part of a kayak’s stern. The wooden frame of such a craft, covered with waterproof seal skins, was made to measure for the person who would be doing the paddling. It was so finely calibrated that a kayak often was destroyed when the owner died.

Carved from a caribou antler, this barbed harpoon head (left) originally had a sharp tip, now broken. Its tapered bottom fit into a bone socket at the end of a long wooden shaft. The incised lines mark ownership. Hunters of sea mammals normally worked in a group, and the man whose harpoon struck the prey first was often entitled to a special portion of the meat. This piece of slate (right) was ground into its sharp, pointed shape and then slotted into the end of an arrow. Archaeologists found more than a thousand of these at the site of Nunalleq, mostly in association with the dwelling that was attacked. Some were even embedded in the building’s posts, probably the result of attackers shooting arrows down the hallways.

Like many of the sewing tools found at Nunalleq, this awl handle (left) was made of walrus ivory. A sharp tip of ground stone, bone, or even a rare bit of metal was once attached to the shank at the bottom. To sew a tough skin, an awl was normally used to punch holes along the seam line so the bone or ivory needle could glide in and out without breaking. Wooden dolls turned up all over the archaeological site. Some were simple playthings; others were probably used in rituals. This example, (right) carved from soft willow wood, has an unusually distinctive, detailed face that was likely meant as a portrait. The figure may have been created to stand in for someone who was unable to attend an important function.

Even without warmer winters, the children’s lives are very different from what their elders experienced. Qanirtuuq chairperson Grace Hill, 66, sees trends that concern her—like the fading language. “When I went to first grade, I only spoke Yupik. Now the kids only speak English,” she tells me in the fluent, slightly accented English that she learned in school. And then, of course, there’s the modern technology that’s changing everything everywhere. “The kids are more into computers—and they’re forgetting about our culture,” she worries.

Like other older villagers, Hill at first opposed the excavation of Nunalleq because Yupik tradition says ancestors shouldn’t be disturbed. But now she believes that archaeology can serve a greater good. “I’m hoping this will get the kids interested in their past,” she says.

Henry Small has the same thing in mind one sunny afternoon when he brings his 11-year-old daughter, Alqaq, to Nunalleq to check out the progress of the dig. This is their second visit this summer. When I ask him what he hopes his daughter learns here, he responds as if the answer were obvious: “Where she comes from!”

Alqaq, in a pink T-shirt, plaid capris, and movie-star sunglasses, is getting the message. On previous visits she has helped sort artifacts and sift the excavated soil for small things the archaeologists might have overlooked. She especially likes the dolls, she says, and the lip plugs. And what about the ulus, like the one her father made for her birthday, with her name carved into the handle? “It’s cool that we get to use what our ancestors were using,” she says without hesitation. Today’s visit is brief, with no work to do, so Alqaq and her father soon head up the beach toward home on an ATV.

The weather-bleached whale bones piled around clothesline poles in a Quinhagak backyard likely washed up on a beach nearby. Village elders remember bringing home dozens of whales every year, but those days are gone. Hunters now may make just a single catch on the open sea.

Archaeology’s potential to inspire such appreciation for the past is what motivated Jones to get the dig started. He asked Knecht to assess the eroding site, then helped convince the village’s board of directors that excavating Nunalleq was a good idea. He also got the board to fund the first two years of digging and provide ongoing logistical support. “It wasn’t cheap,” he says. “But to get the artifacts for our future generations, money didn’t matter.”

At the end of each field season the archaeologists have packed up what they’ve found and shipped it to the University of Aberdeen for conservation. But all the artifacts will be sent back later this year, destined for an old school building that Quinhagak has converted to a heritage center. Jones envisions this as a place where people can see, touch, and share stories about the beautifully worked possessions of their ancestors.

“I want our kids who are in college now to run it and be proud that it’s ours,” he says. And when this dream takes shape and the center opens its doors? “I want to be the first to go in and say, ‘I’m Yupik, and this is where I come from.’”

#archaeology#anthropology#native american#Yupik#alaska#Nunalleq#arctic#climate change#environment#national geographic

62 notes

·

View notes