#Masami Taura

Photo

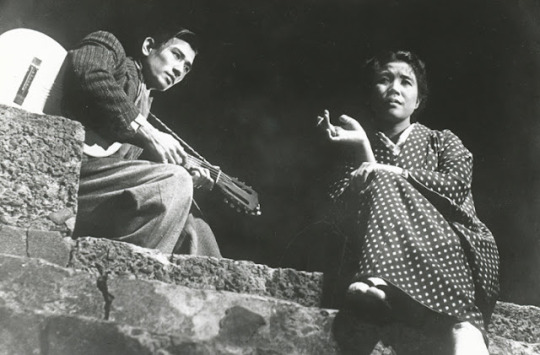

Keiji Sada and Yuko Mochizuki in Tragedy of Japan (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1953)

Cast: Yuko Mochizuki, Yoko Katsuragi, Masami Taura, Teiji Takahasi, Keiji Sada, Ken Uehara, Sanae Takasugi, Keiko Awaji. Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita. Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda. Art direction: Kimihiko Nakamura. Music: Chuji Kinoshita.

Tragedy of Japan is the Criterion Channel's title for Keisuke Kinoshita's film, but I prefer the one used on IMDb and elsewhere: A Japanese Tragedy. Not only does that title echo Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy, but it also particularizes the story better. What happens to Haruko Inoue (Yuko Mochizuki) and her children is not a microcosm of recent Japanese history but a product of it -- one among millions, including those told in Kinoshita's many films. The film also demonstrates something of Kinoshita's tendency to overreach, often with distracting innovations such as the oval masks that frame scenes in You Were Like a Wild Chrysanthemum (1955) or the color washes that creep into The River Fuefuki (1960). Here it's an unwise use of extensive documentary footage of the war and its aftermath as a frame for the fictional story. The contrast between the raw actuality of news footage and the artifice of movie storytelling works to the disadvantage of the latter. Which is unfortunate because Kinoshita has a good story to tell about Haruko's attempts to survive and to provide for her children and the unforeseen consequences of her efforts, as well as the problems faced by Seiichi (Masami Taura) in his ambitious pursuit of a medical career and Utako (Yoko Katsuragi) in her disastrous involvement with her English teacher. None of Haruko's good deeds, it seems, go unpunished, as the skirting of the law that she found necessary is held against her in more peaceful and prosperous times. Despite the mistaken attempt to fold these stories into a larger historical context, this is one of Kinoshita's better films, marked by some very good acting and genuine human dilemmas.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky / Kono hiroi sora no dokoka ni (1954, Masaki Kobayashi)

この広い空のどこかに (小林正樹)

1/10/22

#Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky#Kono hiroi sora no dokoka ni#Masaki Kobayashi#Hideko Takamine#Keiji Sada#Yoshiko Kuga#Akira Ishihama#Minoru Oki#Masami Taura#Kumeko Urabe#Chieko Nakakita#drama#Japanese#gendaigeki#domestic#50s#postwar#families#in-laws#Tokyo#liquor store#disabilities#husband hunting#dysfunctional family#poverty#class differences#matchmaking#Japanese Golden Age

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ineko Arima and Masami Taura - Tokyo Twilight (1957)

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tokyo Twilight (1957, Japan)

I haven’t been a classic movie fan for as long as some fellow amateur writers on movies, and I've only been delving into older live-action Japanese films within the last ten years. Having only made Akira Kurosawa’s acquaintance in 2010 and Kenji Mizoguchi’s after that, my first viewing of a Yasujirô Ozu film was in 2012, with his Early Spring (1956) – the work that preceded the subject of this write-up, Tokyo Twilight. A half-decade later to that introduction to Ozu, I am beginning to realize – like the plays of Shakespeare, the animated movies of Walt Disney Animation Studios and Studio Ghibli, the symphonies of Beethoven, and any other continuum of challenging, worthwhile art – that it will take me a lifetime to become familiar with Ozu’s movies. Bar any unforeseen developments in my health, there is plenty of time to do so.

For on the surface, the director’s works are filled with the tatami shots and pillow shots that I have written about numerous times on this blog. Beyond that, Ozu’s humanity, the intricacies of mundane human life, and his attention to individuals between moments of catharsis or tragedy reflect a philosopher-artist fully in control of the artform he specializes in.

Tokyo Twilight is considered Ozu’s darkest film, and it’s certainly the darkest Ozu film I have yet to see – it is not recommended for those who never seen an Ozu movie before. This darkness is based not in what the film depicts – remember, Ozu never shows the most traumatic moments (Chieko Higashiyama’s character dies off-screen in 1953′s Tokyo Story) or even a character’s greatest celebrations or victories (the buildup to Setsuko Hara’s wedding in 1949′s Late Spring is essential to that film’s plot, but the wedding itself is skipped over) – but how it impacts the characters we come to know intimately and make us care for them. Tokyo Twilight, with that apt title, would be Ozu’s final film in black-and-white.

Banker and single father Shukichi Sugiyama (Chishû Ryû) is looking forward to spending time with his eldest daughter, Takako (Setsuko Hara), as she is returning home from the aftermath of an unhappy, perhaps abusive, marriage. Takako is also bringing home her young daughter, who is just learning how to walk. Youngest daughter Akiko (Ineko Arima) is learning English shorthand and she, too, is having significant other troubles with Kenji (Masami Taura). One evening while searching for Kenji, Akiko stumbles upon a mahjong parlor owner named Kisako (Isuzu Yamada), who claims to have been an old neighbor of the Sugiyamas many years ago. Even for a neighbor, Kisako seems to know more about the Sugiyama family than she should, instantly making Akiko suspicious. In Tokyo Twilight’s second half, the two most important subplots emerge: the identity of Kisako is deduced by Takako and Akiko becoming pregnant thanks to a boyfriend who could not care less.

Ozu, considered one of the greatest of filmmakers and one-third of the trinity of great Japanese directors (alongside Kurosawa and Mizoguchi) and sometimes framed as unassailable by his less critical supporters, addresses one of his storytelling weaknesses with co-screenwriter Kôgo Noda. That weakness: Ozu has always excelled in crafting stories from the viewpoints of elders or parental figures, not so much their children. And when those children are as young as those found in I Was Born, But... (1932) or Record of a Tenement Gentleman (1947), Ozu’s depiction of children – though well-meaning, and sufficiently funny when needed to be in his comedies – never adopts their perspective, but frames their experiences through the behaviors and expectations of the adults in the movie. Having seen only one teenager as a central character in an Ozu film (Miyuki Kuwano in 1958′s Equinox Flower), my sampling size is too small to draw any conclusions – but I can’t imagine Ozu and Noda were any better with depicting teenagers. Hara and Yamada are playing young women here and, unusually in Ozu’s earlier post-silent era movies, Tokyo Twilight centralizes their fears, desires, joys, and disappointments for the plot – not that this marginalizes the father’s concerns.

Akiko and Takako are not content to care for their father alone, but to assert their independence. Takako, as the oldest, is not the stereotypically submissive woman so often found in Japanese narratives, and will not tolerate her husband’s inebriation and boorish behavior. We don’t know whether Takako married her husband out of love or some other means, but so often in Japanese cinema one would expect the battered wife to stick it out or openly fight with him. Takako knows better than to bother. Streaks of independence are even more pronounced with Akiko, who is more Westernized and enjoys being a rebel without a cause (this characterization might be the most problematic, as Ozu and Noda refuse to look into why Akiko might be acting this way – instead, Ozu and Noda prefer to have Mr. Sugiyama wallow in self-pity and express his sadness about how he raised his daughters). Among the adult daughters that appear in Ozu’s films, Akiko might be the least trusting, least reliant, and most manipulative towards her parent and other elders.

And yet despite their attempts to escape from the traditional trappings of marriage, the Confucian-influenced relationships between children and parents, or both, Akiko and Takako find the past to be inescapable. In conjunction with Yuuharu Atsuta’s pillow shots – unlike previous Ozu movies – are kept to confined spaces inside buildings or at the end of cluttered walkways. Gone are the expansive shots of a morning or afternoon sky, the flowing windswept grasses of a hillside or a berm leading up to train tracks. Instead of those relaxed pillow shots, Tokyo Twilight features pillow shots including the uncertainty that comes with darkness (almost all of the pillow shots appear during nightfall, let alone twilight), the confining angles of the home and other familiar buildings. The past, before and after those pillow shots, is built over years by the “little white lies” that parents tell their children. Perhaps the lies that your parents told you are not as serious as those eventually revealed by Tokyo Twilight’s conclusion. But at its essence, Tokyo Twilight is a piece depicting the last vestiges of childhood innocence (maintained by parental prevarication) stripped away, and how damaging that can be.

Tokyo Twilight is the most plot-centric of the Ozu-Noda collaborations. With multiple plot twists – to even have one plot twist in an Ozu movie is uncommon – and verbal conflict more visceral than usual, this is not the placid meditation that longtime Ozu fans who have never seen Tokyo Twilight before might expect this film to be. It is, oftentimes bitter, disillusioned. The two women of Tokyo Twilight are suffering from a lack of love demonstrated by their partners and the adults – persnickety and gossiping – surrounding them. Such developments are unsustainable for any human being after years of misdirections and separations. Maybe someday Akiko and Takako will accept the indiscretions of their father, their elders, and their friends as the behavior of men and women unable to imagine life in any other way. Maybe someday Akiko and Takako may find the room to forgive those who did not love them as much as they should have. But that will not happen in Tokyo Twilight or immediately after the movie’s defining tragedy – which, in true Ozu fashion, is never shown, only talked about and reacted to.

Twenty-five years old when the film was released, Ineko Arima (Equinox Flower, 1959′s The Human Condition I: No Greater Love) almost never smiles for the 140-minute runtime. For a Japanese movie, in this specific modern culture where women smiling is an uncodified tradition, that is unthinkable. Arima gives the performance of the movie, reflecting an emotional and motivational emptiness that might have been glossed over by Setsuko Hara’s smile in any other Ozu movie. To maintain that disposition for the length of the film and to earn the audience’s empathy is an enormous undertaking, and the young actress has outdone herself here. Despite a history of Ozu and Noda underwriting or refusing to give the adult children the focus of the story, Arima capitalizes on the rich writing offered to her from the screenwriters here.

This would be the third-to-last film Setsuko Hara would make with Ozu, with almost a decade’s worth of stunning performances under his direction. Tokyo Twilight marked the end of Hara, in an Ozu movie, playing a daughter of Chishû Ryû’s that other characters think should have been married long ago. Playing the older sister (possibly because, approaching forty years of age, Hara could not plausibly play the unmarried daughter to Japanese audiences any longer), the character of Takako is one of the least obedient characters Hara played in an Ozu film. The trademark smile is there, though offset quite often with her behavior towards Isuzu Yamada’s character. it is not the most memorable Hara performance, but this would not be the last time Hara would play an older sister character. If Hara had continued her career after Ozu’s death, performances like Tokyo Twilight might instead be used an example of Hara’s versatility rather than a deviation from typical Hara roles.

The veteran Ryû –who appeared in fifty-two of Ozu’s fifty-four films (including Ozu’s seventeen lost and partially surviving films) – is sometimes unreadable in Tokyo Twilight, but this plays to the film’s characterizations. It is an assured performance drawing deep from his acting experience. As Mr. Sugiyama, reserved and exhausted amid post-War change, Ryû disassociates himself with the personal details and trivialities of others unless it is somehow related to his family’s welfare. Social change and the outside world do not seem to bother him, and he is just willing to cast his fate to the winds of that change without knowing where those winds might take him. The traumas of Japanese militarization – how it estranged Mr. Sugiyama from his family and Japanese society at-large – are omnipresent. This is Ryû playing a sort of victim; a victim who unwittingly contributes, in part, to his family’s ultimate despair.

Japanese audiences, expecting a ponderous familial drama of smaller incidents rooted in a greater wisdom, responded poorly to Tokyo Twilight upon the film’s release. Over time – at least among Western audiences and cinephiles – Tokyo Twilight has burnished its reputation as one of Ozu’s most ambitious movies, embracing plotting in ways that the director had not done so since the 1930s.

I have read from certain film critics that some of the greatest movies can help change how one conducts their life or views the act of living for the better. For me, the Ozu films that I have seen – as a whole, not any one in particular as of yet – have helped shape how I view relationships familial, platonic (not so much romantic). By how much? Ask me in another five years of watching Ozu movies and I might have a more definite answer for you. Because like I've written above, Ozu and Noda are best at writing through the eyes of adults, not their adult children. Nevertheless, these films, in their own ways, still have their appeals even to adult children.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Tokyo Twilight is the one hundred and forty-second film I have rated a ten on imdb.

#Tokyo Twilight#Yasujiro Ozu#Ineko Arima#Setsuko Hara#Chishu Ryu#Isuzu Yamada#Haruko Sugimura#Nobuo Nakamura#Masami Taura#Kogo Noda#Yuuharu Atsuta#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

1 note

·

View note

Photo

東京暮色 (1957) · Yasujiro Ozu

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

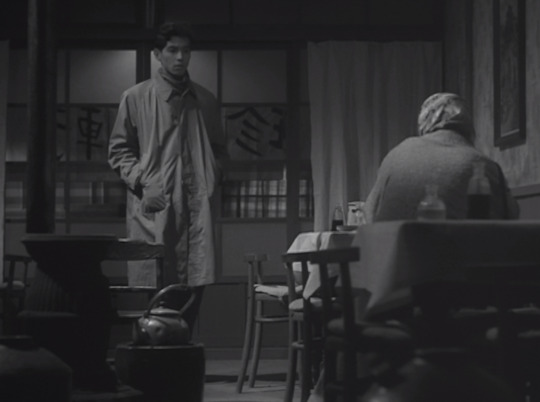

Tokyo Twilight | Yasujirô Ozu | 1957

Masami Taura, Ineko Arima

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

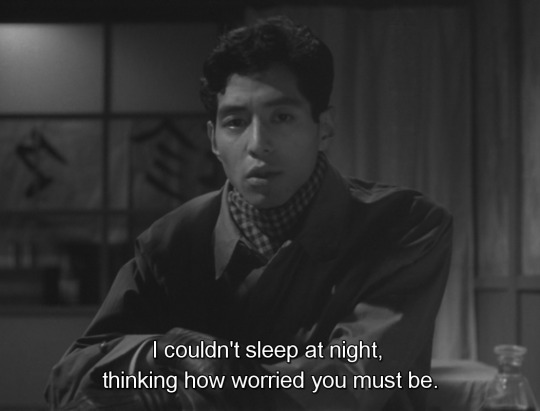

sensitive Kenji (worried sick κυριολεκτικά)

Tokyo Twilight (1957), dir. Yasujirō Ozu

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ryo Ikebe and Keiko Kishi in Early Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1958)

Cast: Chikage Iwashima, Ryo Ikebe, Teiji Takahashi, Keiko Kishi, Chishu Ryu, So Yamamura, Takako Fujima, Masami Taura, Haruko Sugimura, Kumeko Urabe, Kuniko Miyake, Eijiro Tono. Screenplay: Kogo Noda, Yasujiro Ozu. Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta. Production design: Tatsuo Hamada. Film editing: Yoshiyasu Hamamura. Music: Takanobu Saito.

Early Spring is a film pregnant with significant themes: the dreariness of corporate office work, the nostalgia for wartime adventure and camaraderie, the tension between tradition and modernization, but none them are allowed to overwhelm the simple human story it tells. Shoji Sugiyama (Ryo Ikebe), a "salaryman" for a fire-brick manufacturing company, and his wife, Masako (Chikage Awashima), are have grown apart after the death of a child: He throws himself into his work, into concern over the illness of a friend, into after-hours drinking with old war buddies, and finally into a brief affair with a young woman (Keiko Kishi) he has met on the commuter train. She's called "Goldfish" because of her large eyes, and she's a rather giddy and flirtatious woman who likes to pal around with the guys. After Shoji and Goldfish are seen together on a weekend hike put together by some of their co-workers -- Masako, who is reserved and rather traditional in manner, declined to accompany him -- gossip begins to spread. Eventually it comes back to Masako, and after several incidents -- he spends the night with Goldfish and claims he was with his sick friend, he forgets to observe the anniversary of the death of their son, and he brings home two very drunk war buddies -- she leaves him. Meanwhile, Shoji has been offered a transfer to a manufacturing branch of his company in a distant city where he will have to spend three years in the hope that he can return to Tokyo and a promotion. He accepts the offer, and at the end Masako joins him, thinking they can work things out. At the conclusion they watch a train go by and reflect that Tokyo -- as symbolic for them as Moscow is for Chekhov's three sisters -- is only three hours away. Characteristically, Ozu and co-screenwriter Kogo Noda tell this story in a strictly linear fashion. Another director might have been tempted to insert expository flashbacks to, for example, the death of the child. But by letting the story play out as it happens -- beginning with a "typical" day in the life of the Sugiyamas -- Ozu builds a special kind of intimacy with his characters, as we gather the clues to their behavior and sometimes their relationships along the way. This intimacy is reinforced by Ozu's signature low-angle camera, in which we build our acquaintance with the characters from the ground up, as it were.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Masami Taura and Akira Ishihama in Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky (Masaki Kobayashi, 1954)

Cast: Keiji Sada, Yoshiko Kuga, Hideko Takamine, Akira Ishihama, Minoru Oki, Toshiko Kobayashi, Masami Taura, Kumeko Urabe, Chieko Nakakita, Shin'ichi Himori, Ryohei Uchida. Screenplay: Yoshiko Kusuda. Cinematography: Toshiyasu Morita. Art direction: Kazue Hirataka. Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara. Music: Chuji Kinoshita,

Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky* is a reminder that Masaki Kobayashi began his career as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita. It not only employed Kinoshita's brother Chuji as composer of the score, along with the director's usual film editor, Yoshi Sugihara, it also displays one of Kinoshita's usual domestic drama themes: the conflict of tradition and modernity as several generations of a family try to work out a way of living together in postwar Japan. And it shares some of Kinoshita's sentimentality in the developments of its plot. In tone and theme, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky could not be more different from the film Kobayashi made just before it: the harsh, fierce The Thick-Walled Room, which was made in 1953 but which the studio withheld from release until 1956. For that matter, it's not much like Kobayashi's bleak slum drama Black River (1956) or his unsparing three-part antiwar epic The Human Condition (1959-1961). Kobayashi would find his way out of the genteel trap that Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky represents. Which is not to say that he didn't make a pleasant, thoroughly enjoyable film in which everyone seems to find themselves on the right path by the time the plot works itself out. Ryochi (Keiji Sada) and Hiroko (Yoshiko Kuga), who run the family liquor store, have married for love, which alienates his stepmother, who would have preferred an arranged marriage. Abetted by Ryochi's depressed, self-loathing sister, Yasuko (Hideko Takamine), the stepmother constantly finds fault with Hiroko. Eventually, however, everyone makes peace, thanks in large part to Ryochi's steadfast good nature in defense of his wife and to Yasuko's unexpectedly finding love and a new purpose in life. The feel-good elements of the film are not quite so convincing as the harsher parts, but the performances -- especially that of Takamine in a cast-against-type role -- are persuasive.

*The Criterion Channel title is a translation of the Japanese title Kono hiroi sora no dokoka ni. IMDb gives it as Somewhere Under the Broad Sky, and I've also seen it referred to as Somewhere Beneath the Vast Heavens.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Isuzu Yamada in Tokyo Twilight (Yasujiro Ozu, 1957)

Cast: Setsuko Hara, Ineko Arima, Chishu Ryu, Isuzu Yamada, Haruko Sugimura, Nobuo Nakamura, Kamatari Fujiwara,��Kinzo Shin, Masami Taura. Screenplay: Kogo Noda, Yasujiro Ozu. Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta, Art direction: Tatsuo Hamada. Music: Takanobu Saito.

Some critics see Mikio Naruse's Sound of the Mountain (1954) as a kind of reaction against films by Yasujiro Ozu like Late Spring (1949) in which the plot climaxes with the marriage of a young woman. Naruse explored the fact that marriage is not always, or even seldom, the fulfillment of things that the bride and her family have wished for. But Ozu himself is not beyond skepticism about marriage, and no film of his depicts that skepticism more keenly and tragically than Tokyo Twilight, in which a father whose own marriage has failed is trying to cope with the failed marriage of one daughter and the troubled love life of another. The father in this case is played, as it so often was in Ozu's films, by Chishu Ryu, Ozu's favorite actor. I can see why Ozu liked him so much: Is there any other actor who can say "Hmm" with such eloquence and variety of intonation than Ryu? He has many opportunities to pack that internalized sound with meaning in Tokyo Twilight, expressing everything from doubt to contentment to disapproval, or just reinforcing his character's stoic resignation to the misfortunes that life continues to bring him. Ryu’s Shukichi Sugiyama and his three children were abandoned by his wife during the war, when he was stationed in Seoul, and he has done what he can to raise the family. The son from the marriage has died in an accident several years earlier, and now his daughter, Takako (Setsuko Hara), has left her husband, bringing their toddler daughter to live with Shukichi. The other daughter, Akiko (Ineko Arima), has a disastrous fling with the irresponsible Kenji (Masami Taura), who leaves her pregnant and looking for the money to have an abortion. The various secrets that the family, packed into one of the boxlike homes Ozu has made into such eloquent settings (expressing both closeness and confinement), only become more pressing when the girls' mother, Kikuko (Isuzu Yamada), returns to their lives: She and her new husband (Nobuo Nakamura) -- the man she left Shukichi for has died -- run a mah jongg parlor that Akiko, searching for Kenji, finds herself in. Kikuko overhears the young woman's name and, realizing Akiko is her daughter, strikes up a conversation, asking about the family without revealing the truth. But then Shukichi's sister accidentally encounters Kikuko while shopping and brings him the news that she's returned. When Takako overhears, she goes to Kikuko and asks her not to reveal her identity to Akiko. But secrets will out, and Akiko, racked with guilt not only for the abortion but also for having been arrested under suspicion of prostitution while waiting for Kenji in a bar, decides that she has inherited a bad streak from Kikuko, even questioning whether Shukichi is her actual father. Events are set in motion that culminate in Takako denouncing Kikuko, who decides to leave town. There is a poignant scene at the end in which Kikuko, hoping that she has made amends with Takako, looks out of the window of the train for her daughter to say goodbye. If you know Isuzu Yamada only as the sinister "Lady Macbeth" of Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957), her performance as the woman who has spent a lifetime of quiet regret will be eye-opening. As usual, Ozu transcends the potential for sentimental excess and the complexities of plot to arrive at just the right blend of pathos and quiet endurance.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Mieko Takamine and Chieko Higashiyama in The Garden of Women (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1954)

Cast: Mieko Takamine, Hideko Takamine, Keiko Kishi, Yoshiko Kuga, Takahiro Tamura. Masami Taura, Takashi Miki, Kuniko Igawa, Yoko Mochizuki, Chieko Higashiyama, Kikue Mori. Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, based on a story by Tomoji Abe. Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda. Art direction: Kimihiko Nakamura. Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara. Music: Chuji Kinoshita.

Youth rebellion films became a prominent genre in Japan, but Keisuke Kinoshita's The Garden of Women is distinctive in that the rebels are all women. They have a lot to rebel against: They are students in a hidebound women's college more determined to turn them into proper young ladies than into educated women. This causes difficulties for Yoshie Izushi (Hideko Takamine), who is a few years older than her fellow students. Most of them come from wealthy families, but Yoshie had to work for several years to earn enough money for the tuition. She wants an education that would make her a fitting partner for her upwardly mobile boyfriend, Sankichi (Takahiro Tamura). But she struggles with some subjects, especially math, and when she tries to study after hours she comes up against school rules that forbid her from studying anywhere except in her room -- which is usually filled with her roommates' friends, who are plotting against the stern headmistress, Mayumi Gojo (Mieko Takamine), aka "The Shrew." Yoshie wants no part of the rebellion: She wants to graduate and marry Sankichi before her family forces her into marriage with a wealthy man of their choosing. Eventually, the student rebellion succeeds, but Yoshie gets caught in the crossfire. The Garden of Women is one of Kinoshita's more successful films, mostly because it gives us an unexplored angle on Japanese society and its tumultuous postwar society. But it's somewhat overplotted, with a few too many characters whose stories take away from the central narrative.

0 notes

Photo

Tokyo Twilight | Yasujirô Ozu | 1957

Masami Taura, Ineko Arima

14 notes

·

View notes