#Machiek Machiek

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts on Sydney Film Festival

I just want to point out and say this: I’ve never went to Sydney Film Festival.

I never did, and reason for that is because I’m not a giant film enthusiast. I’d rather go to YouTube conventions such as Vidcon, Playlist Live and Amplify, which is my version of a film festival since it focuses on online multiplatforms and so forth. But my university requires us to attend the festival and write 2 essays on our thoughts throughout the events and the films we watched. At first, I thought I wouldn’t enjoy it, that I would get bored and probably just wing the assignments… but I was mistaken as I actually enjoyed it. Not to the point where next year I’d go again and get like a multi-day pass, nope. It’s more on the fact that I just had a good time and it’s worth going if you really like movies and you’d wish to become a filmmaker yourself

‘But aren’t you doing a film major? ‘

I’m doing journalism as a sub-major. I want to work in broadcast media. The only thing that I have to be concerned about is the world around me and knowing who our current Prime Minster and State Premier are. But films are nice and knowing who made what just allows you to understand what their filming styles are like and how’d they’d change over the years (the last time I did this when a few friends and I debated which of James Cameron’s work is better, Titanic or Avatar).

I only attended 2 events in the festival, The Dendy Awards for Australian Short Films and the world premier of ‘Hope Road’ – A documentary by Tom Zubrycki (you can pretty much figure out what were my 2 film classes based on). I was required to watch them and give a review on my thoughts towards the films. I have to say, despite being one of the youngest to attend (based on observation since the people around me were elderly people and huge film enthusiast for many years), they were quite interesting and worth a watch.

There was a common theme shown from both of the events I’ve attended, and that is the theme of ‘Struggle’ – How each character has to overcome the obstacles and issues that they face just to reach their goals, fulfil their dreams or to just get on with life. And the various styles of how each of the films were presented and produced showed various was to interpret that theme.

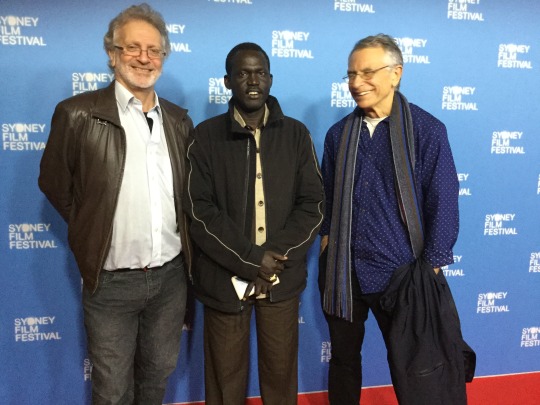

Hope Road

Yup… I met the people behind the documentary

Hope Road is the 11th film created by Australian Filmmaker Tom Zubrycki and is based on Zacharia Machiek’s vision to build a school in his home village in South Sudan. The film has been in production since 2012 and the story is still ongoing as there is more to be done. According to Zubrycki, the documentary is more than just a ‘fundraiser documentary’, but it also tells Zacharia’s personal story as a refugee and his determination to help his people back in South Sudan. The film also mentions the need for education (especially for women), gender equality for men and women, the conflict that’s currently occurring in South Sudan, and hope that the people who view this film would support their project.

The film starts off explaining about the conflict in Sudan in 1995, telling the results of the war and the amount of people who were affected and killed. We’re then introduced to Zacharia, a refugee who was one of the surviving Lost Boys of Sudan, as he’s on a flight to his home village. We are then seen the landscape of his village and throughout the documentary, we’re able to compare the lifestyle the Sudanese people in contrast to what we have here in the western world and how Zacharia’s personal life and the political conflict affected him from reaching his goal.

“Two things that kept the African people alive – hope and your own determination” – Zacharia.

This film reveals to audiences the struggles that the South Sudanese people and let audience realise the importance of women’s equal rights to work and education. Zacharia states that not many people view the importance of men and women working together and that peace could not be achieved without the participation of women.

We’re also exposed to Zacharia’s struggles as his domestic life and the ongoing conflict that’s occurring in South Sudan as well as financial issues, play a role on the delays and the prevention on getting the job done. But no matter how bad the situation is, Zacharia still believes that something good would come out of it. Zacharia still has a connection to his family and people back in South Sudan and this what drive his motivation to help them provide the education they need. What this film hopes to let people take out it is to let them know that there will always be hope, no matter how bad the situation is and that migration is more complicated than it’s seems as the migrants have a role on giving something back to the people that’s closest to them.

Despite the film having an inconclusive ending, Hope Road is a film that will put viewers to view the different perspectives of our world. They will learn that not everything is simple as it is and that there will be twist and turns as we go through in life; but also learn that there is always hope for them to succeed.

The Dendy Awards for Australian Short Films

Some of the films that I watched (via Sydney Film Festival Site)

The Dendy Awards is a short film competition where 10 films are selected out of the 288 that were submitted. This year, there were a range of directors and filmmakers, some have years of experiences, some collaborated with big media industries and universities, and there were some who just started.

Here are some of the highlights of the night:

Adele

Adele is a film about an African teenage girl named Adele who is an expecting teen mum and has to go through her family tradition of arrange marriage, unconsented sex (which caused her pregnancy) and how it affects her, her ‘partner’ and her family. This film deals with what it’s like to go through the toughest situations when it comes to becoming a teen mum and how it affects their personal life.

After all

A stop-motion animation film about a son’s relationship with his mother who dies from smoking. The film merges the two timelines of the son’s past and present to tell the story and was able to intertwine the two timelines to tell the story.

Brown lips

An Aboriginal film made in Western Sydney, with collaboration with the ABC, where two cousins who fall in love and the girl wonders what if they’d escape with each other. This film was slightly criticised by a few of the audiences due to it’s theme of incest. The use of emotion was well used and you could clearly see how much the two characters felt for each other.

Lost Property Office

An animated film about an officer faces loss of his job due to it’s redundancy. He works at lost property where no one collects their lost goods and it just keeps accumulating with dust. This short filmed has this steampunk theme mixed with a 60’s vibe since it’s on a sepia filter rather than technicolour. The film made it hint that the officer was going to commit suicide due to the loss of his job but gave a twist ending that was slightly unexpected.

The Wall

An illustrated animated film about a grandma and her grandchild who runs away from war and are stuck in a camp with a giant wall blocking their way and sold everything about herself she had for a better future for the boy. The film had narration which was very poetic and it symbolised on how it’s like to seek refuge from the war and the victims wanting to give their children a better future.

Each film shown told different stories using different styles and the audience had various emotional response towards the films they’ve sat through. The use of colour, lighting and music helped set the mood on what each scene is about and the use of symbolism in the animated films gave the short films a deeper meaning to its story. Some of the films had a direct plot that the audiences could easily pick up and some needed to be critically analyse to figure out what the main intension is. Overall, the films were inspiring and are worth watching over again.

Whether you’re really into films or just a casual viewer or just someone like me who just spends time on the internet, The Sydney Film Festival is worth going to. You don’t have to go every year or to all the events but just supporting independent films that were funded by Screen Australia, and seeing the final product after months and years of production, its worth attending. As someone who mostly enjoys the online platform, I was quite inspired to see what they’ve created and it did inspire me and I plan to apply what they did in their films when I work on my future projects.

So if you’re given the chance to go to this event, at least try to give it a chance. It’s nice to try something new for a change. And who knows, you may also be inspired to create something as well.

0 notes

Photo

Moonrise by Machiek Wyganski

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiir sacks health undersecretary, Dr. Makur

Kiir sacks health undersecretary, Dr. Makur

President Salva Kiir has sacked the undersecretary at the Ministry of Health, Dr. Makur Matur Koriom.

Dr. Makur was appointed to the position in 2012 when he replaced Dr. Olivia Lomuro.

In a decree read on the state-own SSBC TV on Wednesday evening, Kiir replaced Dr. Makur with Dr. Mayen Machut Machiek.

Dr. Mayen was the Dean of the College of Medicine at the University of Juba.

The changes…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Truth and objectivity in animated documentary

John Grierson described documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality” (Dirk Eitzen p82, 1995). Although this is a widely accepted definition, it is difficult to establish what constitutes “actuality”. As all representations of reality are reflections of a personal viewpoint or belief, and documentaries are often designed to portray a specific message, it could be argued that these depictions are in part fictional. To me, what constitutes a documentary is a representation of real events, people and locations, which tells the story of what actually happens, or has happened in reality. It is valid for a documentary to offer a perspective, interpretation or an argument of it’s subject, as this is a natural consequence of the nature of documentary. However, it is important that the filmmaker represents reality and does not reinterpret it. In this essay, I will explore whether animation follows or defies the fundamental values of truth and objectivity in documentary.

Paul Wells underlines the key issue of animated documentary, which is that the very nature of animation cannot be objective. ‘The very subjectivity involved in producing animation, [...] means that any aspiration towards suggesting reality in animation becomes difficult to execute. For example, the intention to create a ‘documentary’ in animation is inhibited by the fact that the medium cannot be objective’ (Paul Wells p27, 1998). He goes on to say that ‘the medium does enable the film-maker to more persuasively show subjective reality.’ This is a fundamental point. Indeed, suggesting reality through animation may be difficult, but it can be hugely beneficial when used to portray subjective matters.

Animated documentaries consist of drawing and imagery that a camera literally cannot make, but this does not necessarily render them untruthful. Their content can still be about real people, real locations and real events. Slaves is an animated documentary about two Sudanese children, Abouk aged nine, and Machiek aged fifteen, who were kidnapped and enslaved by government backed militia in southern Sudan. David Aronowitsch and Hanna Heilborn made sensitive visuals that allow the children’s voices to be heard. The film begins with the interview set up, and as the interview progresses, the animation moves out of the room and the children’s terrible experiences are visualised. By establishing the film in the reality of the interview, the experiences of the children are more afflictive. This is highlighted when Abouk and Machiek talk about the abuses they witnessed, for example, of other children being ‘torn apart’ and thrown down a well. The sound recording is accurate and unedited. The typical background noises associated with an interview setup, such as the little sneezes, gives the audience a strong sense of how traumatic and true their experiences are. As a viewer, what you see is a subjective representation, but what you hear is a real child recounting a real experience. Rozenkrantz maintains that the inclusion of the actual recorded voice is critical to guarantee an animated documentary’s success. The success of Slaves is due to this, as it enables the viewer to trust the interviewee’s story. Rozenkrantz also claims that hearing the actual voice of the individual who the memories belong to, fills the gaps and provides credibility (Jonathon Rozenkrantz, 2011). In Slaves, the majority of the interview concerns the children’s memories of their past, of which no footage exists. The animation bridges the gap between the voices of the children and their memories, creating a deeper connection and understanding. Slaves is an exceptional piece of animation which highlights what animation can achieve in the field of nonfiction documentary.

Animation also enables consideration and control over movement. Animators can selectively exclude or add information. They can control the length of time the observer views information and the way it unfolds. Sometimes less is more, as a viewer will gain more from a documentary that is easy to digest and understand. This applies to Slaves, as when the children start to speak of their experiences, we are taken out of the room and into another landscape, where the scenes are not crowed or busy, allowing the children’s stories to come through clearly and making a bigger impact. Although this is not necessarily the case in Slaves, condensing information can result in the filmmaker’s truth being imposed onto the audience, as they may make the decision to leave out something significant which subtlety changes the story. The animators of Slaves have produced a slight shake of the frames, which mimics a camera wobble. This is a small touch, but it undoubtedly adds to the sense of reality. It could be argued that the content of solely voice-recorded interviews are more truthful than that of video-recorded interviews, as film crews and camera equipment can be intimidating to interviewees, who might not feel comfortable to speak openly of their experiences.

Animation can act as a substitute to live-action documentary. Substituting what cannot be captured through film. ‘Animated documentaries offer us an enhanced perspective on reality by presenting to us the world in a breadth and depth that live action alone cannot’ (Jeffrey Skoller, 2011). It can be a very effective tool when depicting the unseen, making the invisible visible. Examples of the unseen are subjective, internal psychological states, or the visualisation of events where no footage or only partial footage exists, such as memories, as demonstrated by Slaves. Although it may be easy to identify ways in which animation can be beneficial to documentary making, it can be challenging to bring this back in relation to truth. All documentaries are constructions, and the viewer discovers the ‘truth’ in a film through the director’s assembly of cinematic choices – choices that inevitably represent the filmmaker’s version of the truth (Peter Biesterfeld, 2016). Indeed, it might be helpful for an audience to see visuals of a subject, but this could potentially detract from the original message, as rather than the audience experiencing the ‘truth’, they are instead viewing the director or creator’s understanding or interpretation of the truth. Arguably, this question can be applied to live-action documentary. As Wolf Koenig stated, “every cut is a lie. Those two shots were never next to each other in time that way. But you're telling a lie in order to tell the truth” (Peter Biesterfeld, 2016). It could be said the animated documentaries are more ‘truthful’ than live-footage documentaries, as they are true to the editing process. No one thinks they are real. Whereas in live-action documentaries, particularly during scenes where the past has been reenacted, people may consider the documentary as untrustworthy. Animation however, asks us to see it for what it is, ‘a construct or representation,’ by introducing a certain transparency and self-consciousness to the mix’ (Beige Adams, 2009).

One of the main strengths of animation is its power to engage the audience. Often, an abstract representation of information is more appealing than a literal one. American filmmaker, Richard Robbins, believes real footage ‘impinges your ability to listen to the story’ (Beige Adams, 2009). As a society, we tend to disengage when presented with genuine footage of pain, suffering and violence.

‘Animation has emerged as an important practice in recent documentary, particularly those that examine life in wartime’ (Tess Takahashi, 2011). Waltz with Bashir is an animated documentary about the Lebanon war and dealing with trauma. The use of animation creates space from the photographic imagery that is necessary in order to observe and take in the information. For topics like trauma, animation seems suitable, as ‘the unconscious must become manifest. The invisible must become visible’ (Carlo Avventi, 2018). The filmmaker, Ari Folman’s experience shapes Waltz with Bashir. It is his attempt to make sense of his time as an Israeli soldier in the Lebanon war in 1982. It is centred around a series of conversations between Folman and other Israeli soldiers, who were in Lebanon on the night that three thousand Palestinian refugees were massacred by Christian militia. Twenty years on, after an old friend tells Folman of a recurring nightmare relating to the war, Folman realises that he has no recollection of his experiences during the war. Ari Folman had previously worked on more conventional, live-action documentaries, but for Waltz with Bashir, animation seemed fitting due to the nature of the content. Folman himself said, ‘with animation you can do anything’ (Carlo Avventi, 2008). The film weaves in and out of dreams, hallucinations and memories, of both his own and other veterans, and it makes it possible to visualise these subjective, internal thoughts. As each man tells his story to Folman, we are taken out of the setting of the conversation and into a frightening, dark landscape. ‘The freedom afforded by animation [..] allows Mr. Folman to blend grimly literal images with surreal flights of fantasy, humour and horror’ (A. O. Scott, 2008).

As in Slaves, the interpretation of the Lebanon war through animation was not a wholly aesthetic decision, ‘with its artificiality, the animation offers the necessary distance to be able to approach the images of such an event’ (Carlo Avventi, 2018). When a subject is too horrific, many people find it too hard to watch live-action, or choose not to watch it as a way of self-protection. Animation can be a useful tool to draw people in without being too gruesome. However, to gain a true understanding of a subject, it may be that the absolute reality needs to be seen. Animation could potentially act as a blanket. Viewers may use its clear subjectivity as a comfort that what they are seeing didn’t really happen. This psychological block is challenging to break. Maybe the most ‘truthful’ documentary is one that uses both animation and live-footage; for animation to slowly introduce an idea to the audience, without being too graphic, then to consolidate its reality, by showing real photographic images or footage. The subject’s reality is then inescapable. This way, the filmmaker is able to show their truth without causing viewers to disengage for reasons of self-protection. This is what Ali Folman did in his animated documentary, Waltz with Bashir. Just before the film finishes, the animation stops, and we are faced with horrifying footage of raw grief and real dead bodies. This indicates ‘just how far Mr. Folman is prepared to go, not in the service of shock for its own sake, but rather in his pursuit of clarity and truth’ (A. O. Scott, 2008). It is also his ‘way of acknowledging that imagination has its limits, and that even the most ambitious and serious work of art will come up short against the brutal facts of life’ (A. O. Scott, 2008). As the audience, when confronted with these graphic images, it is the stark contrast between this and the animation that allows the reality and pain to really hit hard. The live-action footage is the most distinguishable difference between Waltz with Bashir and Slaves and is certainly effective, but it does not necessarily make Waltz with Bashir more truthful. The unedited voice recording of the children’s stories in Slaves serves as a powerful truth.

All documentaries set out to teach us something about the world, and animation can take this further by pushing the boundaries of how and what we learn. There are many things in our world that simply cannot be observed literally. Animation can compensate for the restrictions of live-action. Slaves and Waltz with Bashir both demonstrate the benefits of using animation in documentary making. ‘It is clear that animation is not just a technique or technology, but a necessary mode of representation’ (Jeffrey Skoller, 2011). Indeed, the medium itself is not objective, but it’s ability to bring subjective meaning to life is formidable. In my opinion, if the content is based on real events, real people and real locations, animated documentaries do adhere to the conventional values of truth in reportage, and in some cases, animation can convey information with more success, particularly when describing subjective states. I believe there is just as much discourse with animated documentaries as live-action documentaries when questioning their ‘truth’. Though both are valid, animation is undoubtedly more truthful, as it is transparent to the way it is made, allowing the audience to be more thoughtful and creating a space to make their own judgment.

0 notes