#Lord Mountjoy

Text

#OTD in 1600 – O'Neill engages Mountjoy's forces in the Battle of Moyry Pass.

In September of 1600, the Irish forces of Hugh O’Neill, whom the English had made Earl of Tyrone, were in rebellion against the crown. Two years earlier O’Neill and his principle ally “Red” Hugh O’Donnell had routed an English army under Sir Henry Bagenal at Yellow Ford, expelling the English completely from the lands of O’Neill. Now Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, was marching on Tyrone with…

View On WordPress

#Battle of Moyry Pass#Charles Blount#England#History#History of Ireland#Hugh O&039;Donnell#Hugh O’Neill#Ireland#Irish History#Lord Mountjoy#Queen Elizabeth I#Redshanks#Today in Irish History#Tyrone

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapuys had taken up Catherine's cause upon his arrival in London after the recess of the court of Blackfriars. Until Anne's succession, her uncle often communicated with Chapuys, ingratiating himself with the diplomat in the hope that he might learn secret information concerning Charles V. In this context, the Duke [of Norfolk]'s statement that both Anne's father and he were opposed to the King's decision to marry her was significant because this information enabled the hostile ambassador to assume that Anne, presumably acting without family support, had bewitched Henry into divorcing Catherine. Following this assumption to its logical conclusion, Chapuys could then blame Anne instead of the King for the European crisis the marital dispute had created. Far from being a valid private account of the royal household, Chapuys's dispatches provide an intriguing history of what he thought, and of what others wanted him to think, about court politics. The fact is that after 1531, when Catherine of Aragon was rusticated, no major courtier was willing to plead with the king of her behalf and, with the break-up of her household, her support at court ceased to exist. Even Thomas More's continuation as Lord Chancellor rested on the assumption that King and Parliament could decide the succession, and when he resigned it was to defend a Church whose unity was under attack. In 1533, the King's councillors, including William, Lord Mountjoy, Catherine's own chamberlain, attempted to persuade her to accept the title of Princess Dowager.

Tudor Political Culture, Dale Hoak

#'recess'...a sensible chuckle.gif#catherine of aragon#eustace chapuys#henry viii#anne boleyn#thomas howard#dale hoak#thomas boleyn#presumably acting without family support is a bit of a stretch insofar as chapuys definitely knew and reported#that george was very fiercely in her corner . but yeah. chapuys was fairly credulous of norfolk 'confiding' in him in this instance#'no major courtier' does not really seem like so much of a stretch bcus#the imperial lady/mistress only seems to have sent a message to princess mary . the implication was sympathy for coa but no attempt at#intercession for her necessarily...#'her support at court ceased to exist' i'll have to check. idr when the duchess of norfolk hid that message#in an orange for her...maybe it was prior 1531?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my increasingly favorite pastimes is imagining Shakespeare as an actor performing roles in his own plays, so without further ado, here are the roles we think Shakespeare he performed (per stylistic analysis and contemporary accounts):

The Lord (Induction) (Taming of the Shrew)

Antonio, the Duke (Two Gentlemen of Verona)

Suffolk (Henry VI Part 2)

Warwick, Old Clifford (Henry VI Part 3)

Mortimer or Exeter (Henry VI Part 1)

Aaron (Titus Andronicus)

Clarence, Scrivener, and Third Citizen (Richard III)

Egeon (Comedy of Errors)

Friar Lawrence and Chorus (Romeo and Juliet)

Duke Theseus (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

Old Gaunt and/or the Gardener, the Lord (Richard II)

Leonato, the Friar (Much Ado About Nothing)

King Henry, Rumor (Henry IV Parts I & II)

The Garter Inn’s Host, Master Ford (The Merry Wives of Windsor)

Old Kno’well (Every Man In His Humor by Ben Jonson)

Chorus, Ely, and Mountjoy (Henry V)

Adam, later Corin (As You Like It)

Flavius (Julius Caesar)

Ghost, First Player (Hamlet)

Antonio (Twelfth Night)

Ulysses (Troilus and Cressida)

Macro and Sabinus (Sejanus His Fall by Ben Jonson)

Brabantio (Othello)

The King (All’s Well that Ends Well)

The Poet (Timon of Athens)

Duncan, perhaps Banquo later on (Macbeth)

Antiochus and Simonides, Cleon (Pericles)

#william shakespeare#shakespeare#i’m haunted by his aaron the moor#even his leonato…#he was said to perform old man/father/kingly roles#i also think he played lodovico in othello#also added the ben jonson ones because why not#oh and clarence!!!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

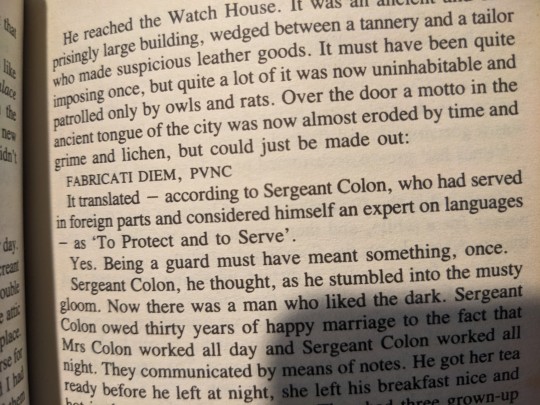

FABRICATI DIEM, PVNC

...and later...

"This is Lord Mountjoy Quickfang Winterforth IV, the hottest dragon in the city. It could burn your head clean off... What you've got to ask yourself is: Am I feeling lucky?"

Love those Dirty Harry moments in G!G!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Derbyshire Lawlessness

On the 1st January 1434 90 men under Thomas Foljambe attacked their rivals, the Longfords in Chesterfield. Parish Church.

Henry Longford + William Bradshaw were killed & Sir Henry Pierrepont was maimed as detailed in an oyer and terminer commission of March 1434 issued to the duke of Bedford, Humphrey Stafford duke of Buckingham, William de la Pole Earl of Suffolk and two judges

The parish churches were frequently the scene of open conflict in the 15th century where the pulpit could be used to whip up support!

In 1434 alone there were 200 juries assembled to try to deal with the Foljambe-Pierrepont / Longford dispute. Pierrepont is known to have sat on at least one and others were definitely pro Foljambe.

The original source of the quarrel is largely obscure but may have been an attempt by one Richard Brown g Replan to get Thomas Foljambe acquitted g felony by 'trickery' and it appears that Foljambe had the key support of the Vernons. It also became apparent that Foljambe had prevented Pierrepont from collecting profits from Chesterfield Fair which was licensed to him by Joan Holland, Countess of Kent. Foljambe was also accused of illegally issuing 21 liveries - the most ever recorded in a session - highlighting the wider political sympathies as his co-accused included Sir Ralph Cromwell, Henry, Lord Grey & Joan Beauchamp, Lady Bergavenny.

The largest skirmish reported was in 1454 when 1,000 men attacked Walter Blount at Elvaston including Longfords and Vernons, now apparently working together!

Such large numbers of gentry were involved that it was almost impossible to recruit a jury at all. Richard, duke g York, John, Earl of Shrewsbury and 2 judges eventually heard the case at Derby in July 1454 and continued in September 1454 and at Chesterfield in March 145S, still without enough jurors to try the key figures.

Despite the undoubted truth of Blount's case, the family were almost completely isolated and Vernon and Longford refused to attend the sessions. It is probably that greater forces were at work: Humphrey Stafford duke of Buckingham may well have encouraged the attack on Blount who was a retainer of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, Buckingham and Warwick being rivals in Warwickshire and although Buckingham had supported York's protectorate, he was a staunch supporter of Henry VI and Somerset.

Buckingham retained Vernon after the first session and Vernon responded by bringing men from across the Peak to join the fray. Buckingham was clearly lining up against Warwick's man, showing that it was not only in the north that local rivalries and national politics were intertwined.

The Derbyshire Gentry in the Fifteenth Century

Susan M. Wright

Derbyshire Record Society Volume VIII, 1983

Image: Garter stall plate of Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy (c.1416-1474), KG. St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. Image published in: Hope, W. H. St. John, The Stall Plates of the Knights of the Order of the Garter 1348 – 1485

0 notes

Video

youtube

Amazing Historical Events That Occurred on 3/30🎉 #shorts #history

March 30th has seen some truly amazing historical events! In 1282, the people of Sicily rose up in revolt against King Charles I in the famous Sicilian Vespers. This event was a major turning point in the history of Sicily, and helped to spark a large-scale revolt against the monarchy.

In 1603, the English army led by Lord Mountjoy was victorious in the Battle of Mellifont against the Irish. This battle was decisive in the Nine Years' War and resulted in the treaty of Mellifont that would bring an end to the conflict.

Fast forward to 1814, where the Sixth Coalition forces marched into Paris after their successful defeat of Napoleon. This marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and many consider it to be one of the most amazing historical events of all time.

In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia for the sum of $7.2 million in the famous Alaska Purchase. This was an incredibly important event that shaped the future of the US, and still has major implications today.

Finally, in 1945, the Soviet Union invaded Austria, marking the beginning of the Cold War. This was the start of a decades-long conflict that would shape much of the world for the rest of the 20th century.

March 30th is certainly a day that has seen some amazing historical events, from the Sicilian Vespers to the beginning of the Cold War. It's an important day in history that deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

Amazing Historical Events That Occurred on March 30th

In 1282, the people of Sicily rose up in revolt against King Charles I in the historic Sicilian Vespers. Fast forward to 1603, where the English army led by Lord Mountjoy was victorious in the Battle of Mellifont against the Irish.

In 1814, the Sixth Coalition forces marched into Paris after their successful defeat of Napoleon. Over 50 years later, in 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia for the sum of $7.2 million in the famous Alaska Purchase. Finally, in 1945, the Soviet Union invaded Austria, marking the beginning of the Cold War.

https://bit.ly/freebetwithCrypto

https://splinterlands.com?ref=mortonmattd1

https://bit.ly/getonHive

https://ecency.com/signup?referral=m0rt0nmattd

https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=m0rt0nmattd

https://exode.io/?ref=790e9e1

https://bit.ly/WinCryptoWithMe

https://bit.ly/FreeCryptoDrip

https://bit.ly/FreeZECdrip

0 notes

Text

The Irish Rebellion, 1641: ‘Worse and Worse News from Ireland’

The Commencement of Civil Strife in the British Isles

Illustration from a popular pamphlet of the time showing alleged Old Irish atrocities against Protestants in Ireland

THE IRELAND of 1641 was a collection of quite distinct and mutually antagonistic communities. There were the so-called “Old Irish”, the Gaelic speaking Roman Catholic native Irish people, now substantially reduced to peasant semi serfdom by newer arrivals from England. There were the “Old English” (sometimes also referred to as the “New Irish”) who were descended from the original twelfth century Ango-Norman settlements. This group were generally landowning aristocrats, traditionally at odds with the conquered Old Irish, but since the Reformation, shared Roman Catholicism with their historic subject peoples and a healthy scepticism towards more recent arrivals from the old country. This latter grouping termed, not altogether accurately, as the “New English”, consisted of Protestant settlers from England who arrived during the colonisation of eastern Ireland under Elizabeth I, more recently supplemented since the reign of James I by Presbyterian Scots. This group, for religious reasons and those of social class, had no love for either Irish grouping and not much regard for each other, given the Anglican and Presbyterian divide which had become so rancorous in England and Scotland. Strafford’s great skill, through bribery, manipulation, assertive use of the Irish Parliament and key concessions to the different interest groups at tactical points, was to hold this mutually antagonistic society together and, unlike England or Scotland, broadly loyal to the king. Without Strafford, however, Ireland began to resemble a powder keg.

Strafford had repeatedly assured Charles that Ireland was a peaceful and pliant subject nation, so when revolt broke out in October 1641 in Ulster, it took all English opinion, Royalist and Parliamentarian, by surprise. Perhaps inevitably, the rebellion was triggered by the most oppressed class, the dispossessed and landless Old Irish, whose grievances had been exacerbated by Strafford’s preference to both elements of the New English, particularly favouring the Scots colonies in Ulster, in an effort to prevent their signing up to the National Covenant of Scotland. With little or no stake in the established order, the Old Irish took the opportunity of the power vacuum the execution of “Black Tom” Wentworth produced, to launch a well planned assault on the Royal and New English fortresses and settlements. The Old Irish grievances were primarily that of lack of land ownership and a manifest lack of respect for Catholicism by Strafford and his Scots and New English allies. In this, however, they were joined by their Catholic Old English landlords, who feared a Scots led new settlement of Ireland displacing both their religion and their pre-eminent social position. The rebellion quickly began to assume a proto “national” Irish character. Led by landowner Sir Phelim O’Neill, an insurgent Irish army launched simultaneous assaults on Newry, Armagh, Charlemont and Mountjoy on 23rd October 1641. All fell in a matter of days.

With the north of Ireland now in ferment, the response from England reflected the political conflict in which that kingdom was embroiled. All were agreed that something had to be done to combat what was in effect a Catholic rebellion against the Protestant ascendancy in Ireland, but Parliament and the King could not agree what that response should be, or which of them should co-ordinate it. The sense of crisis was heightened by lurid reports of Irish Catholic atrocities against Protestants. O’Neill himself had been clear from the outset that the rebellion was intended to restore ancient Irish liberties progressively eroded by English Lord Lieutenants, particularly Strafford. He also asserted that the rebels had no wish to secede from the United Kingdoms, pledged loyalty to the king and ordered that Protestants who did not resist the rebellion should not be harmed. However, centuries of injustice will out, and many fleeing Protestants, often egged on by vengeful Catholic priests, were indeed massacred by mobs and soldiers well beyond O’Neill’s control. To these tales of horror were added, possibly mischievous, claims by the rebels that the King was sympathetic to their cause. This enabled the Puritan factions of Parliament to openly state the Irish rebellion was Charles’ long awaited attempt to return Catholicism to Britain by force.

Soon wildly exaggerated accounts of Catholic depredations in Ireland were being circulated in England, often in vividly illustrated pamphlet form, and were widely believed. The rebels, to back up their claim of Royal sympathy, produced forged documents to demonstrate their case, simply increasing Parliamentary paranoia and paralysing the English kingdom’s response, as Parliament refused to grant Charles the funds to raise an army to combat the rebellion for fear the King would use it against them. A compromise was eventually struck. King and Parliament agreed that Alexander Leslie’s Covenanting army should be sent to Ireland to combat O’Neill’s forces who, by late November had expanded the rebellion to other parts of Ireland. The King saw advantage in getting Leslie’s menacing force off the English/Scottish island; Parliament was happy to see an army despatched not under the control of the King, and the Scottish Covenanters wished to protect their Presbyterian kin and to extend their influence into Ireland.

Meanwhile John Pym and his allies feared the Irish crisis would distract from the Puritan campaign to secure constitutional reform. Amidst the debates over funding and control of the armed forces, Pym sought to get his Grand Remonstrance, a letter from Parliament to the King listing all Parliament’s grievances against Royal actions over the 1630s, passed by the Commons. This was achieved in November 1641, but Parliamentary opinion was no longer united. Many opponents of Royal prerogative became irritated by this move during a time of national crisis and the Remonstrance passed with a much smaller majority than Pym was used to, and a supplementary resolution to have the document published and distributed was defeated outright. Parliamentary unity was beginning to fray, as those MPs who felt sufficient concessions had been wrung from Charles began to hang back from further reform, while Pym’s Putrian lobby continued to press for the institution of what would come to be termed a constitutional monarchy. Battle lines were now being drawn within Parliament itself.

In Ireland the army of Leslie, now the Earl of Leven, had immediate success. By spring 1642, County Down had been pacified and in May, Newry was recaptured, accompanied by a massacre of Catholic survivors, including many civilians, adding to a folk memory of Protestant Scots atrocity in Ulster that would stretch down the centuries of bitter conflict in the territory. Protestant reprisals and excess solidified the Old and New Irish alliance. Following a Catholic victory at Julianstown, the Gaelic Irish and their landowning co-religionists met in Kilkenny in summer 1642 and agreed to form an alternative government for Ireland, loyal to the King, but which should achieve an end to further Protestant settlement in Ireland, a rejection of Anglican or Presbyterian religious hierarchies and the endorsement by the rest of the United Kingdoms of Catholicism as the religion of Ireland: this confederation was in many ways an Irish version of Scotland’s National Covenant. Thus began Ireland’s own civil war: the so called Confederate War of 1641-1653.

The British Kingdoms were now on the verge of outright civil war. The intense constitutional and religious controversies since 1625 had seen the monarch dispense with the services of Parliament for eleven years and rule as an absolute monarch. Equally when Charles stubbornly insisted on his divinely appointed will to impose Anglicanism throughout the British Isles, his Scottish subjects had resorted to rebellion and war. The actions of Strafford had exacerbated tension in Ireland and resulted, after his death, in what amounted to a national Catholic rebellion, prompting ill advised Scottish Presbyterian military intervention in Ireland, creating an almost revolutionary atmosphere and, ultimately, a resolution on the part of the English Parliament to “reconquer” Ireland. Organised violence had now become the means to resolve political dispute in two of Britain’s three kingdoms. Resorting to such action to conclude the conflict of King and Parliament in England perhaps now seemed to many, to be simply logical.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Henry's marriage to Catherine had long since grown cold. Though his wife remained, and would remain, loyal and devoted, Henry was in very different case. The raptures of the early days had faded and the consequent demands upon him for self-discipline and generosity had found him wanting. Catherine was five years his senior. In I527 he was still in his prime, in his mid-thirties, she over forty. As king he could satisfy desire all too easily, for who would refuse a king easily, especially a king such as he? Fidelity was rare among monarchs and the temptation besetting him, in particular, strong.

At first Henry had been a gallant husband. Catherine had accompanied him to every feast and triumph, he had worn her initials on his sleeve in the jousts and called himself 'Sir Loyal Heart'. He had shown her off to visitors, confided in her, run to her with news. Though there had been talk of a lady to whom he showed favour while campaigning in France, he had slipped home ahead of his army and galloped to Catherine at Richmond in order to lay the keys of the two cities he had captured at her feet.

We cannot know when he first succumbed to the temptation of adultery, but it must have been within five years of his marriage, when there appeared on the scene one Elizabeth Blount, a lady-in-waiting of Queen Catherine and a cousin of Lord Mountjoy - and she may not have been the first. She caught the king's eye during the New Year festivities in I5I4, that is, shortly after he had returned from the first campaign in France. Bessie Blount eventually bore him a son, in I519. Subsequently she married into a gentle family, the Talboys of Lancashire, with a dower of lands in that county and Yorkshire assigned by act ofParliament. Hers, then, was a fate less than death; and her son, the duke of Richmond, was occasionally to acquire considerable political and diplomatic significance.

Next there was Mary Boleyn, since 1521 wife of William Carey, daughter of a royal councillor and diplomat, and sister of Anne. That Mary was at one time Henry's mistress, and this presumably after her marriage, is beyond doubt. Years later there was a strong rumour that she too had born Henry a son, but we cannot be sure. Anyway we may guess that the liaison was over by l526, and when her younger sister climbed on to the English throne, with perhaps pardonable pique, she dismissed Mary from the court. The latter was to do well enough, with her family at the centre of affairs during the reign of her niece, Elizabeth I - which was more than could be said of Bessie Blount. And finally there was Anne, Thomas Boleyn's younger daughter.

Following in the wake of her sister, who had been in the entourage that accompanied Mary Tudor to France in 1514, Anne had crossed the Channel about 1519 to enter the household of Queen Claude, wife of Francis I, an amiable lady who had several young girls in her care and supervised their education. The newcomer to the royal school must have been about twelve years old. She stayed in France until the out- break of war in 1522 and then came home, by which time she was on the way to becoming an accomplished and mature girl. She does not seem to have been remarkably beautiful, but she had wonderful dark hair in abundance and fine eyes, the legacy of Irish ancestors, together with a firm mouth and a head well set on a long neck that gave her authority and grace.

On her return, if not before, her future had apparently been settled, ironically by Henry and Wolsey. She would marry Sir James Butler, an Irish chieftain and claimant to the earldom of Ormond, to which the Boleyns, rivals of the Butlers, had long aspired. Anne was therefore to mend the feud by uniting families and claims. Had this familiar kind of device been executed, and had this been the sum total ofher experience ofhow marriage and politics could interweave, things might have been very different for England, if not for Ireland. But Butler's price was too high and Anne remained in England.

Her father, aided perhaps by her grandfather, the second duke of Norfolk, had meanwhile brought her to Court, as he had her sister before her. There she eventually attracted attention, first from Sir Thomas Wyatt, the poet, a cousin of hers; then from Henry Percy, son of the earl of Northumberland and one of the large number of young men of quality resident in Wolsey's household. Alas, Percy was already betrothed. At the king's behest, Wolsey refused to allow him to break his engagement and, summoning him to his presence, rated him for falling for a foolish girl at Court. When words failed, the cardinal told the father to remove his son and knock some sense into him. Percy was carried off forthwith- and thus began that antipathy for Wolsey that Anne never lost.

But it may well be that, when Henry ordered Wolsey to stamp on Percy's suit, it was because he was already an interested party himself and a rival for the girl's affection of perhaps several gay courtiers, including Thomas Wyatt. The latter's grandson later told a story ofhow Wyatt, while flirting once with Anne, snatched a locket hanging from her pocket which he refused to return. At the same time, Henry had been paying her attention and taken a ring from her which he thereafter wore on his little finger. A few days later, Henry was playing bowls with the duke of Suffolk, Francis Bryan and Wyatt, when a dispute arose about who had won the last throw.

Pointing with the finger which bore the pilfered ring, Henry cried out that it was his point, saying to Wyatt with a smile, 'I tell thee it is mine.' Wyatt saw the ring and understood the king's meaning. But he could return the point. 'And if it may like your majesty,' he replied, 'to give me leave that I may measure it, I hope it will be mine.' Whereupon he took out the locket which hung about his neck and started measuring the distance between the bowls and the jack. Henry recognized the trophy and, muttering something about being deceived, strode away.

But the chronology ofAnne's rise is impossible to discover exactly. All that can be said is that by I525-6 what had probably hitherto been light dalliance with an eighteen or nineteen year-old girl had begun to grow into something deeper and more dangerous. In the normal course of events, Anne would have mattered only to Henry's conscience, not to the history of England. She would have been used and discarded - along with those others whom Henry may have taken and who are now forgotten. But, either because of virtue or ambition, Anne refused to become his mistress and thus follow the conventional, inconspicuous path of her sister; and the more she resisted, the more, apparently, did Henry prize her.

Had Catherine's position been more secure she would doubtless have ridden this threat. Indeed, had it been so, Anne might never have dared to raise it. But Catherine had still produced no heir to the throne. The royal marriage had failed in its first duty, namely, to secure the succession. Instead, it had yielded several miscarriages, three infants who were either still-born or died immediately after birth (two of them males), two infants who had died within a few weeks ofbirth (one ofthem a boy) and one girl, Princess Mary, now some ten years old. His failure to produce a son was a disappointment to Henry, and as the years went by and no heir appeared, ambassadors and foreign princes began to remark the fact, and English diplomacy eventually to accommodate it, provisionally at least, in its reckoning.

Had Henry been able to glimpse into the second halfofthe century he would have had to change his mind on queens regnant, for his two daughters were to show quality that equalled or outmeasured their father's; and even during his reign, across the Channel, there were two women who rendered the Habsburgs admirable service as regents ofthe Netherlands. Indeed, the sixteenth century would perhaps produce more remarkable women in Church and State than any predecessor - more than enough to account for John Knox's celebrated anti-feminism and more than enough to make Henry's patriarchal convictions look misplaced. But English experience of the queen regnant was remote and unhappy, and Henry's conventional mind, which no doubt accorded with his subjects', demanded a son as a political necessity.

When his only surviving legitimate child, Mary, was born in February 1516, Henry declared buoyantly to the Venetian ambassador, 'We are both young; if it was a daughter this time, by the grace of God sons will follow.' But they did not. Catherine seems to have miscarried in the autumn of 1517 and in the November of the following year was delivered of another still-born. This was her last pregnancy, despite the efforts of physicians brought from Spain; and by 1525 she was almost past child-bearing age. There was, therefore, a real fear of a dynastic failure, of another bout of civil war, perhaps, or, if Mary were paired off as the treaty of 1525 provided, of England's union with a continental power.

Catherine, for the blame was always attached to her and not to Henry, was a dynastic misfortune. She was also a diplomatic one. Charles's blunt refusal to exploit the astonishing opportunity provided by his victory at Pavia and to leap into the saddle to invade and partition France had been an inexplicable disappointment. Of course, had Henry really been cast in the heroic mould he would have invaded single- handed. But established strategy required a continental ally. Eleven years before, in 1514., Ferdinand of Spain had treated him with contempt and Henry had cast around for means of revenge, and there had been a rumour then that he wanted to get rid of his Spanish wife and marry a French princess.

Whether Henry really contemplated a divorce then has been the subject of controversy, which surely went in favour of the contention that he did not - especially when a document listed in an eighteenth-century catalogue of the Vatican Archives, and thought to relate to the dissolution of the king's marriage - a document which has since disappeared - was convincingly pushed aside with the suggestion that it was concerned with Mary Tudor's matrimonial affairs, not Henry's. Undoubtedly, this must dispose of the matter even more decisively than does the objection that, in the summer of 1514, Catherine was pregnant. In 1525, however, the situation was different. Charles had rebuffed Henry's military plans and, by rejecting Mary's hand, had thrown plans for the succession into disarray.

For a moment the king evidently thought of advancing his illegitimate son - who, in June 1525, was created duke of Richmond. But this solution was to be overtaken by another which Henry may have been contemplating for some time, namely, to disown his Spanish wife. Catherine, therefore, was soon in an extremely embarrassing position. Tyndale asserted, on first-hand evidence, that \Volsey had placed informants in her entourage and told of one 'that departed the Court for no other reason than that she would no longer betray her mistress'.' When Mendoza arrived in England in December 1526, he was prevented for months from seeing the queen and, when he did, had to endure the presence of Wolsey who made it virtually impossible to communicate with her. It was the ambassador's opinion that 'the principal cause of [her] misfortune is that she identifies herselfentirely with the emperor's interests'; an exaggeration, but only an exaggeration.

The king, then, had tired of his wife and fallen in love with one who would give herself entirely to him only if he would give himself entirely to her; his wife had not borne the heir for which he and the nation longed, and it was now getting too late to hope; he had been disappointed by Catherine's nephew, Charles V, and now sought vengeance in a diplomatic revolution which would make the position of a Spanish queen awkward to say the least. Any one of these facts would not have seriously endangered the marriage, but their coincidence was fatal. If Henry's relations with Catherine momentarily improved in the autumn of 1525 so that they read a book together and appeared to be very friendly, soon after, probably, Henry never slept with her again.

The divorce, which came into the open in early 1527 was therefore due to more than a man's lust for a woman. It was diplomatically expedient and, so some judged, dynastically urgent. As well as this, it was soon to be publicly asserted, it was theologically necessary, for two famous texts from the book of Leviticus apparently forbade the very marriage that Henry had entered. His marriage, therefore, was not and never had been, lawful. The miscarriages, the still-births, the denial of a son were clearly divine punishment for, and proof of, transgression of divine law. Henry had married Catherine by virtue of a papal dispensation of the impediment of affinity which her former marriage to Arthur had set up between them.

But Leviticus proclaimed such a marriage to be against divine law - which no pope can dispense. So he will begin to say. And thus what will become a complicated argument took shape. Henry had laid his hand on a crucial weapon - the only weapon, it seemed, with which he could have hoped to achieve legitimately what he now desired above all else. How sincere he was is impossible to determine. More than most, he found it difficult to distinguish between what was right and what he desired. Certainly, before long he had talked, thought and read himself into a faith in the justice of his cause so firm that it would tolerate no counter-argument and no opposition, and convinced himself that it was not only his right to throw aside his alleged wife, but also his duty - to himself, to Catherine, to his people, to God.

At the time, and later, others would be accused of planting the great scruple, the levitical scruple, in Henry's mind. Tyndale, Polydore Vergil and Nicholas Harpsfield (in his life of Sir Thomas More) charged Wolsey with having used John Longland, bishop of Lincoln and royal confessor, to perform the deed. But this was contradicted by Henry, Longland and Wolsey. In 1529, when the divorce case was being heard before the legatine court at Blackfriars, Wolsey publicly asked Henry to declare before the court 'whether I have been the chiefinventor or first mover of this matter unto your Majesty; for I am greatly suspected of all men herein'; to which Henry replied, 'My lord cardinal, I can well excuse you herein. Marry, you have been rather against me in attempt- ing or setting forth thereof' - an explicit statement for which no obvious motive for misrepresentation can be found and which is corroborated by later suggestions that Wolsey had been sluggish in pushing the divorce forwards.

Longland too spoke on the subject, saying that it was the king who first broached the subject to him 'and never left urging him until he had won him to give his consent'. On another occasion Henry put out a different story: that his conscience had first been 'pricked upon divers words that were spoken at a certain time by the bishop of Tarbes, the French king's ambassador, who had been here long upon the debating for the conclusion of the marriage between the princess our daughter, Mary, and the duke of Orleans, the French king's second son'. It is incredible that an ambassador would have dared to trespass upon so delicate a subject as a monarch's marriage, least of all when he had come to negotiate a treaty with that monarch.

Nor was it likely that he should have sug- gested that Mary was illegitimate when her hand would have been very useful to French diplomacy. Besides, the bishop of Tarbes only arrived in England in April 1527, that is, a few weeks before Henry's marriage was being tried by a secret court at Westminster. The bishop could not have precipitated events as swiftly as that. No less significantly, another account ofthe beginnings of the story, given by Henry in 1528, says that doubts about Mary's legitimacy were first put by the French to English ambassadors in France - not by the bishop of Tarbes to his English hosts.

He and his compatriots may have been told about the scruple or deliberately encouraged by someone to allude to it in the course of negotiations, but did not invent it; nor, probably, did Anne Boleyn - as Pole asserted. It is very likely that Henry himselfwas the author ofhis doubts. After all, he would not have needed telling about Leviticus. Though he might not have read them, the two texts would probably have been familiar to him if he had ever explored the reasons for the papal dispensation for his marriage, and he was enough of a theologian to be able to turn to them now, to brood over them and erect upon them at least the beginnings of the argument that they forbade absolutely the marriage which he had entered.

Wolsey said later that Henry’s doubts had sprung partly from his own study and partly from discussion with 'many theologians'; but since it is difficult to imagine that anyone would have dared to question the validity of the royal marriage without being prompted by the king, this must mean that the latter's own 'assiduous study and erudition' first gave birth to the 'great scruple' and that subsequent conference with others encouraged it. Moreover, Henry may have begun to entertain serious doubts about his marriage as early as 1522 or 1523, and have broached his ideas to Longland then - for, in 1532, the latter was said to have heard the first mutterings of the divorce 'nine or ten years ago'.'

By the time that Anne Boleyn captured the king, therefore, the scruple may already have acquired firm roots, though probably not until early 1527 was it mentioned to Wolsey who, so he said, when he heard about it, knelt before the king 'in his Privy Chamber the space of an hour or two, to persuade him from his will and appetite; but I could never bring to pass to dissuade him therefrom'. What had begun as a perhaps hesitant doubt had by now matured into aggressive conviction.”

- J.J. Scarisbrick, “The Repudiation of the Hapsburgs.” in Henry VIII

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celebrating the New King of England & his Queen Consort:

On the 24th of June 1509, Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon were jointly crowned at Westminster Abbey amidst huge pomp, greeted with public acclaim go from their subjects, high and low.

As some historians point out from contemporary sources, the coronation was a success and up to that point, one of the biggest demonstrations of dynastic power of the century. These contemporaries paint not just a portrait of an impressive king but two young monarchs who were both alike in royal dignity.

"... the following morning Catherine and Henry processed from the palace into the abbey, where two empty thrones sat waiting on a platform before the altar. A contemporary woodcut shows them seated level with each other, looking into each other’s eyes and smiling as the crowns are lowered on to their heads.

It is a potent image of the occasion, intimate in spite of the crowds behind them, suggesting a relationship of two people equal in sovereignty, respect and love. In reality, the positioning of Henry’s throne above hers, and her shortened ceremonial, without an oath, indicates the actual discrepancy between them. He had inherited the throne as a result of his birth; she was his queen because he had chosen to marry her. Above his head the woodcut depicted a huge Tudor rose, a reminder of his great lineage and England’s recent conflicts; Henry’s role was to guide and rule his subjects. Over Catherine sits her chosen device of the pomegranate, symbolic of the expectations of all Tudor wives and queens: fertility and childbirth. In Christian iconography, it also stood for resurrection. In a way, Catherine was experiencing her own rebirth, through this new marriage and the chance it offered her as queen, after the long years of privation and doubt. Westminster Abbey was a riot of colour. Quite in contrast with the sombre, bare-stone interiors of medieval churches today, these pre-Reformation years made worship a tactile and sensual experience, with wealth and ornament acting as tributes and measures of devotion. Inside the abbey, statues and images were gilded and decorated with jewels, walls and capitals were picked out in bright colours and walls were hung with rich arras. All was conducted according to the advice of the 200-year-old Liber Regalis, the Royal Book, which dictated coronation ritual. The couple were wafted with sweet incense while thousands of candles flickered, mingling with the light streaming down through the stained-glass windows. Archbishop Warham was again at the helm, administering the coronation oaths and anointing the pair with oil. Beside her new husband, Catherine was crowned and given a ring to wear on the fourth finger of her right hand, a sort of inversion of the marital ring, symbolising her marriage to her country. She would take this vow very seriously.

The coronation proved popular. Henry wrote to the Pope explaining that he had ‘espoused and made’ Catherine ‘his wife and thereupon had her crowned amid the applause of the people and the incredible demonstrations of joy and enthusiasm’. To Ferdinand, he added that ‘the multitude of people who assisted was immense, and their joy and applause most enthusiastic’.

There seems little reason to see this just as diplomatic hyperbole. According to Hall, ‘it was demaunded of the people, wether they would receive, obey and take the same moste noble Prince, for their Kyng, who with great reuerance, love and desire, saied and cryed, ye-ye’.

Lord Mountjoy employed more poetic rhetoric in his letter to Erasmus, which stated that ‘Heaven and Earth rejoices, everything is full of milk and honey and nectar. Our king is not after gold, or gems, or precious metals, but virtue, glory, immortality.’ In his coronation verses Thomas More agreed with the general mood, explaining that wherever Henry went ‘the dense crowd in their desire to look upon him leaves hardly a narrow lane for his passage’. They ‘delight to see him’ and shout their good will, changing their vantage points to see him again and again. Such a king would free them from slavery, ‘wipe the tears from every eye and put joy in place of our long distress’. " ~The Six Wives and Many Mistresses Henry VIII by Amy Licence

In his book on the Wars of the Roses (Wars of the Roses: The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors), Dan Jones also highlights Henry's good looks and the similarities between him and his maternal grandfather, Edward IV, and the reason for his popular appeal:

"Young Henry came to the throne confident and ready to rule. He was well educated, charming and charismatic: truly a prince fit for the renaissance in courtly style, tastes and patronage that was dawning in northern Europe. He had been blessed with the fair coloring and radiant good looks of his grandfather Edward IV: tall, handsome, well built and dashing, here was a king who saw his subjects as peers and allies around whom he had grown up, rather than semialien enemies to be suspected and persecuted."

Henry VIII understood the power of propaganda. Like his father, he used powerful imagery to push Tudor propaganda but taking a page from his maternal grandfather, Edward IV, Henry also relied on popular acclaim. He knew how to win the people over and dance his way around every argument; his illustrious court and physical prowess won over foreign ambassadors who like Lord Mountjoy and Sir Thomas More also noted his wife's virtues.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

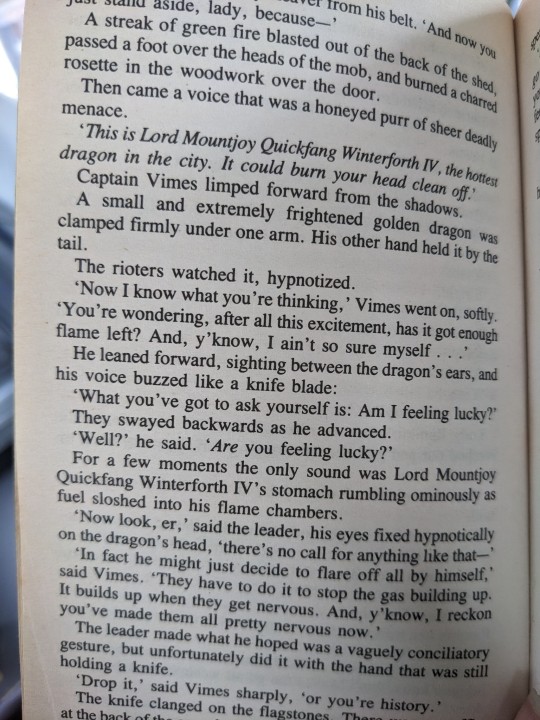

Katherine of Aragon and Erasmus of Rotterdam

The famous Dutch humanist Desiderus Erasmus held an important place in ensuring humanism became a driving force in England. He visited England at the end of the 1400s where he forged important relationships with English scholars such as Thomas More, John Colet and his former pupil, William Blount, Lord Mountjoy. It was then that he met an eight-year old Prince Henry. He went on to live in England between 1511 and 1514 and lectured at Cambridge University. He advised Henry that to be a great king it was important not just to win wars but also to be educated and show the world that the English court was a court of intellectuals.

Erasmus was so well respected by the king and queen that Katherine wanted him to be her Latin tutor; however, he could not be lured back to England. “The Queen has tried to get me to be her preceptor; and everyone knows that if I cared to live even a few months at Court, I might heap as many benefices as I likes. But I allow nothing to interfere with my leisure and studious labours.” However, Erasmus was fascinated by Henry’s studious wife: “As for the Queen, not only is she prodigiously learned for one of her sex, but no less respected for her piety than for her knowledge … The Queen loves literature, which she has studied with good result since her childhood.”

For Erasmus and others, indeed, the fact that Katherine and women like Sir Thomas More’s clever daughters joined in debates ‘afore the king’s grace’ was truly remarkable. This they put down, in part, to Katherine’s own education under her mother Isabel. ‘Who would not wish,’ asked Erasmus, ‘to live in such a court as hers?. Erasmus called Queen Katherine ‘a unique example in our age … who, with a distaste for the things of no account that women love, devotes a good part of her day to holy reading’. Serious, pious Katherine was a contrast to those women who ‘waste the greatest part of their time in painting their faces or in games of chance and similar amusements’, Erasmus said approvingly.

Although he chose not to return to England, he still held the English court in high regard as a place of intellectuals. He described Henry as “the wisest of contemporary princes and a great lover of literature.” Erasmus believed that the English court had become a place of high learning, writing that “your court is a model of Christian instruction, frequented by persons of the very highest erudition, so that there is no university that could not be jealous of it.” Of course this may be mere flattery of a scholar to his potential patron. But Erasmus also extolled the virtues of the English court in correspondence to other people in Europe. He wrote to Bombasius: “You know how adverse I have always been from the courts of princes; it is a life which I can only regard as gilded in misery under a mask of splendour; but I would gladly give move to a court like that, if only I could grow young again … The men who have the most influence [with Henry and Katherine] are those who excel in the humanities and in integrity as wisdom”.

Both Henry and Katherine continued to be active supporters of the humanist scholars and often both commented on books presented to them. One example is a book written by Erasmus, which Vives presented to the king and queen in 1524. In a letter to Erasmus, Vives explained how the book was received: “[Your] book De Libero Arbitrio was yesterday given to the King, who read a few pages, seemed pleased, and said he should read it through. He pointed out to [me] a passage … which he said delighted him much. The Queen also is much pleased. She desired [me] to salute [you] for her, and says that she thanks him for having treated the subject with so much moderation.” This is a fascinating example which shows that both the king and the queen took a personal interest in the works of the great Erasmus as well as other humanist scholars.

In 1526, Erasmus wrote a lengthy book on marriage entitiled Christiani Matrimonii Institutio (The Institution of Christian Matrimony). Queen Katherine, through her chamberlain Lord William Mountjoy, had commissioned Eramus to write this book. With unforeseeable irony Erasmus refers to her ʹmost sacred and fortunate marriageʹ as exemplary. The book itself explained the essential importance of chastity in women within a Christian marriage and less about female education before marriage. It shows that Katherine was asking various humanist scholars in her acquaintance to write books that may have helped with the moral education of her daughter. The book took Erasmus two years to write and was a bulky 300 pages long. A year later William, Lord Mountjoy wrote to Erasmus explaining that the queen was pleased with the book. “But be well assured that our glorious queen is favourably impressed with your Institution of Christian Marriage. She is most grateful to you for this devoted act of yours, and you will learn amply of her good will towards you from the servant to whom I myself have made it known in some detail.”

However, Erasmus, still bitterly regretting his involvement in the Lutheran controversy, had no intention of becoming entangled in Henry’s matrimonial problems. At the same time, Erasmus refused to be drawn in on the queen’s side. Vives asked him at least twice for an opinion on the marriage, but in a letter of September 1528 Erasmus merely reiterated his suggestion that it would be better for Jove to take two Junos than to put one away. Allen, the editor of Erasmus’s letters, conjectured that a mysterious letter enclosed in one addressed to More was an apology to Katherine for his indiscreet references to divorce in Christiani Matrimonii Institutio. Certainly, Erasmus had previously told More of his fear that she had taken offence, though a letter from Mountjoy had reassured him about her attitude. Is however, his only services to the queen were a letter of cautious consolation sent in March 1528 and a recommendation to Mountjoy that she should read his Vidua Christiana: scarcely a tactful suggestion, in view of Katherine’s defence of her status as Henry’s wife rather than Arthur’s widow.

Moreover, Erasmus emphasized his neutrality by accepting comissions from Thomas Boleyn, fully aware, as he told Sadoleto, that this was precisely the Boleyns’ object, since his book on marriage for Katherine had given arguments for the indissolubility of the marriage bond. It is a telling comment on the characters of the king and queen that while Henry ignored Erasmus after his refusal to come to England, Katherine continued to read his works and sent him two gifts of money in 1528 and 1529. In 1529 in his treatise De Vidua Christiana (On the Christian Widow), dedicated to Mary of Hungary (niece of Katherine of Aragon) Erasmus mentions the English queen’s masculine gendering of herself: “Catherine, the queen of England -a woman of such learning, piety, prudence, and constancy that you would find nothing in her that is like a woman, nothing indeed that is not masculine, except her gender and her body”

Sources:

María Dowling, Humanist Support for Katherine of Aragon

Leanne Croon Hickman, Katherine of Aragon : a "pioneer of women's education"? : humanism and women's education in early sixteenth century England

Giles Tremlett, Catherine of Aragon: Henry’s Spanish Queen

Allyna E. Ward, Women and Tudor Tragedy: Feminizing Counsel and Representing Gender

#Desiderius Erasmus#Erasmus of Rotterdam#Katherine of Aragon#Catherine of Aragon#Catalina de Aragon#British history#Men in history#Women in history

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decided to open my copy of Guards! Guards! at a random page and now I’m giggling at the phrase “This is Lord Mountjoy Quickfang Winterforth IV, the hottest dragon in the city. It could burn your head clean off”

I’d give anything to see the look on Sybil’s face at that moment, like... “he remembered the whole name”

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1600 – O'Neill engages Mountjoy's forces in the Battle of Moyry Pass.

#OTD in 1600 – O’Neill engages Mountjoy’s forces in the Battle of Moyry Pass.

In September of 1600, the Irish forces of Hugh O’Neill, whom the English had made Earl of Tyrone, were in rebellion against the crown. Two years earlier O’Neill and his principle ally “Red” Hugh O’Donnell had routed an English army under Sir Henry Bagenal at Yellow Ford, expelling the English completely from the lands of O’Neill. Now Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, was marching on Tyrone with…

View On WordPress

#Battle of Moyry Pass#Charles Blount#England#History#History of Ireland#Hugh O&039;Donnell#Hugh O’Neill#Ireland#Irish History#Lord Mountjoy#Queen Elizabeth I#Redshanks#Today in Irish History#Tyrone

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps Queen [Elizabeth of York] was a soft touch. On December 9, 1502, she gave 12d to a “man of Pontefract” who claimed that he had lodged in his home the queen’s uncle Anthony Wydeville, earl Rivers, during the year of his execution—19 years earlier in 1483! She paid expenses for several children given her as gifts. She provided a new lawn shirt to “a child of Grace at Reading.” The diet, clothing, schooling, and books of Edward Pallet, son of an otherwise unknown Lady Jane Bangham, cost the queen a fairly substantial 50s 3d for the year. John Pertriche, “one of the sons of mad Beale” received his diet, a gown, a coat, four shirts, six pairs of shoes, four pairs of hose, “his learning,” a primer, a psalter, and services of a “surgeon which healed him of the French pox,” courtesy of Elizabeth of York. Seven shillings paid for “the burying of the men that were hanged at Wapping Mill.”

— Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth of York: Queenship and Power

In her [1502] accounts, Elizabeth of York also referred to two different christenings, for which she was probably a godparent. One of them was the child of Lord Mountjoy and the other of a John Bell. She did not actually attend the rituals but sent messengers with gifts.

— Retha Warnicke, Elizabeth of York and Her Six Daughters-in-Law: Fashioning Tudor Queenship 1485–1547

#an angel a literal angel#elizabeth of york#historicwomendaily#dailytudors#historian: arlene okerlund#historian: retha warnicke#elizabeth of york: queenship and power#elizabeth of york and her six daughters-in-law

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

RIBA reveals UK's best buildings for 2021

The Royal Institute of British Architects has announced 54 winners of the 2021 RIBA National Awards for architecture including a floating church, the MK gallery and a mosque in Cambridge.

Awarded annually since 1966, the RIBA National Awards celebrates the best buildings in the UK.

This year's 54 winning projects were chosen from the shortlist for the 2020 RIBA Regional, RIAS, RSUA, and RSAW Awards after last year's awards were postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

"Ranging from radical, cutting-edge new designs to clever, creative restorations that breathe new life into historic buildings, these projects illustrate the enduring importance and impact of British architecture," said RIBA president Simon Alford.

The Cambridge Mosque by Marks Barfield Architects was one of the 54 winners. Photo is by Morley von Sternberg

Included on the list are numerous educational projects, including the Centre Building at LSE by Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners and the School of Science and Sport by OMA at Brighton College.

"There are a good number of well-designed school and university buildings that are powerful investments in the future, and I am sure they will inspire young people, their teachers and communities," said Alford.

"I am also thrilled to see many of these make creative use of existing structures. Well-designed education facilities should be the rule rather than the exception – every child deserves an effective learning environment, and these projects provide rich inspiration."

Grimshaw's Bath Schools of Art and Design was one of several educational winners. Photo is by Paul Raftery

Alford also drew attention to the number of projects that adapt and extend existing buildings.

These included the extension to the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes by 6a Architects (pictured top) and Grimshaw's renovation of its former Herman Miller factory into a building for Bath Schools of Art and Design.

"When a new building is essential, we need to make sure it will last and serve the future well – so it needs to be flexible and reusable," he said. "Long life; loose fit; low energy architecture is the present and the future."

"It is therefore very encouraging to see restoration and sensitive adaptation feature so prominently this year; with many buildings acknowledging their history, the needs of the present and the potential of their dynamic future," he added.

Floating church by Denizen Works was also a winner. Photo is by Gilbert McCarragher

The 54 national winners form the longlist for the Stirling Prize – the UK's most prestigious architecture award. The Stirling Prize shortlist will be announced next week with the winner revealed on 14 October.

See the full list of winners, divided by RIBA region, below:

East

› Cambridge Central Mosque by Marks Barfield Architects

› Imperial War Museums Paper Store by Architype

› Key Worker Housing, Eddington by Stanton Williams

› The Water Tower by Tonkin Liu

Peter Barber Architects' Peckham housing was one of the winners. Photo is by Morley von Sternberg

London

› 95 Peckham Road by Peter Barber Architects

› Blackfriars Circus by Maccreanor Lavington

› Caudale Housing Scheme Mae Architects

› Centre Building at LSE by Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners

› Centre for Creative Learning, Francis Holland School by BDP

› English National Ballet at the Mulryan Centre for Dance by Glenn Howells Architects

› Floating Church by Denizen Works

› House-within-a-House by Alma-nac

› Kingston University London – Town House by Grafton Architects

› Moore Park Mews by Stephen Taylor Architects

› North Street by Peter Barber Architects

› Royal Academy of Arts David Chipperfield Architects

› Royal College of Pathologists by Bennetts Associates

› The Ray Farringdon by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

› The Rye Apartments by Tikari Works

› The Standard by Orms

› The Student Centre, UCL by Nicholas Hare Architects

› Tiger Way by Hawkins\Brown

› Tottenham Hotspur Stadium by Populous

› Wooden Roof by Tsuruta Architects

› Zayed Centre for Research into Rare Disease in Children by Stanton Williams

Windermere Jetty Museum won one of two awards for Carmody Groarke. Photo is by Christian Richter

North East

› Lower Mountjoy Teaching and Learning Centre Durham University by FaulknerBrowns Architects

North West

› Pele Tower House by Woollacott Gilmartin Architects

› The Gables by DK-Architects

› The Oglesby Centre at Hallé St Peter's by Stephenson Hamilton Risley Studio

› Windermere Jetty Museum by Carmody Groarke

Brighton College was another winner. Photo is by Laurian Ghinitoiu

Scotland

› Aberdeen Art Gallery by Hoskins Architects

› Bayes Centre, University of Edinburgh by Bennetts Associates

› Sportscotland National Sports Training Centre Inverclyde by Reiach and Hall Architects

› The Egg Shed by Oliver Chapman Architects

› The Hill House Box by Carmody Groarke

South & South East

› Brighton College – School of Science and Sport by OMA

› Library and Study Centre St Johns College Oxford University by Wright & Wright Architects

› MK Gallery by 6a architects

› Moor's Nook by Coffey Architects

› The Clore Music Studios New College Oxford University, John McAslan + Partners

› The Dorothy Wadham Building Wadham College Oxford University, Allies and Morrison

› The King's School, Canterbury International College by Walters & Cohen Architects

› The Malthouse, The King's School Canterbury by Tim Ronalds Architects

› The Narula House by John Pardey Architects

› Walmer Castle and Gardens Learning Centre by Adam Richards Architects

› Winchester Cathedral South Transept Exhibition Spaces by Nick Cox Architects with Metaphor

Tintagel Castle Footbridge was designed by Ney & Partners and William Matthews Associates. Photo is by David Levine

South West

› Bath Schools of Art and Design by Grimshaw

› Redhill Barn by TYPE Studio

› The Story of Gardening Museum by Stonewood Design with Mark Thomas Architects and Henry Fagan Engineering

› Tintagel Castle Footbridge for English Heritage by Ney & Partners and William Matthews Associates

› Windward House by Alison Brooks Architects

Maggie's Cardiff was the only winner in Wales. Photo is by Anthony Coleman

Wales

› Maggie's Cardiff by Dow Jones Architects

West Midlands

› Jaguar Land Rover Advanced Product Creation Centre by Bennetts Associates

› Prof Lord Bhattacharyya Building University of Warwick by Cullinan Studio

The post RIBA reveals UK's best buildings for 2021 appeared first on Dezeen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celebrating the New King of England & his Queen Consort:

On the 24th of June 1509, Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon were jointly crowned at Westminster Abbey amidst huge pomp, greeted with public acclaim go from their subjects, high and low. As some historians point out from contemporary sources, the coronation was a success and up to that point, one of the biggest demonstrations of dynastic power of the century. These contemporaries paint not just a portrait of an impressive king but two young monarchs who were both alike in royal dignity.

“… the following morning Catherine and Henry processed from the palace into the abbey, where two empty thrones sat waiting on a platform before the altar. A contemporary woodcut shows them seated level with each other, looking into each other’s eyes and smiling as the crowns are lowered on to their heads.

It is a potent image of the occasion, intimate in spite of the crowds behind them, suggesting a relationship of two people equal in sovereignty, respect and love. In reality, the positioning of Henry’s throne above hers, and her shortened ceremonial, without an oath, indicates the actual discrepancy between them. He had inherited the throne as a result of his birth; she was his queen because he had chosen to marry her. Above his head the woodcut depicted a huge Tudor rose, a reminder of his great lineage and England’s recent conflicts; Henry’s role was to guide and rule his subjects. Over Catherine sits her chosen device of the pomegranate, symbolic of the expectations of all Tudor wives and queens: fertility and childbirth. In Christian iconography, it also stood for resurrection. In a way, Catherine was experiencing her own rebirth, through this new marriage and the chance it offered her as queen, after the long years of privation and doubt. Westminster Abbey was a riot of colour. Quite in contrast with the sombre, bare-stone interiors of medieval churches today, these pre-Reformation years made worship a tactile and sensual experience, with wealth and ornament acting as tributes and measures of devotion. Inside the abbey, statues and images were gilded and decorated with jewels, walls and capitals were picked out in bright colours and walls were hung with rich arras. All was conducted according to the advice of the 200-year-old Liber Regalis, the Royal Book, which dictated coronation ritual. The couple were wafted with sweet incense while thousands of candles flickered, mingling with the light streaming down through the stained-glass windows. Archbishop Warham was again at the helm, administering the coronation oaths and anointing the pair with oil. Beside her new husband, Catherine was crowned and given a ring to wear on the fourth finger of her right hand, a sort of inversion of the marital ring, symbolising her marriage to her country. She would take this vow very seriously.

The coronation proved popular. Henry wrote to the Pope explaining that he had ‘espoused and made’ Catherine ‘his wife and thereupon had her crowned amid the applause of the people and the incredible demonstrations of joy and enthusiasm’. To Ferdinand, he added that ‘the multitude of people who assisted was immense, and their joy and applause most enthusiastic’.

There seems little reason to see this just as diplomatic hyperbole. According to Hall, ‘it was demaunded of the people, wether they would receive, obey and take the same moste noble Prince, for their Kyng, who with great reuerance, love and desire, saied and cryed, ye-ye’.

Lord Mountjoy employed more poetic rhetoric in his letter to Erasmus, which stated that ‘Heaven and Earth rejoices, everything is full of milk and honey and nectar. Our king is not after gold, or gems, or precious metals, but virtue, glory, immortality.’ In his coronation verses Thomas More agreed with the general mood, explaining that wherever Henry went ‘the dense crowd in their desire to look upon him leaves hardly a narrow lane for his passage’. They ‘delight to see him’ and shout their good will, changing their vantage points to see him again and again. Such a king would free them from slavery, ‘wipe the tears from every eye and put joy in place of our long distress’. ” ~The Six Wives and Many Mistresses Henry VIII by Amy Licence

In his book on the Wars of the Roses (Wars of the Roses: The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors), Dan Jones also writes aboit Henry’s good looks and the similarities between him and his maternal grandfather, Edward IV, and the reason for his popular appeal:

“Young Henry came to the throne confident and ready to rule. He was well educated, charming and charismatic: truly a prince fit for the renaissance in courtly style, tastes and patronage that was dawning in northern Europe. He had been blessed with the fair coloring and radiant good looks of his grandfather Edward IV: tall, handsome, well built and dashing, here was a king who saw his subjects as peers and allies around whom he had grown up, rather than semialien enemies to be suspected and persecuted.”

Henry VIII understood the power of propaganda. Like his father, he used powerful imagery to push Tudor propaganda but taking a page from his maternal grandfather, Edward IV, Henry also relied on popular acclaim. He knew how to win the people over and dance his way around every argument; his illustrious court and physical prowess won over foreign ambassadors who like Lord Mountjoy and Sir Thomas More also noted his wife’s virtues.

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘I was staying at Lord Mountjoy’s country house, when Thomas More came to see me, and took me with him for a walk as far as the next village where the King’s children - except for Prince Arthur - were being educated. When we came to the hall, the attendants not only of the palace but also Lord Mountjoy’s household were assembled. In the midst, stood Prince Henry, then nine years old and already something of royalty in his demeanor, in which there was a certain dignity combined with a singular courtesy.’ - Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1499 when Henry was really eight years old.

2 notes

·

View notes