#Ken marschall

Text

USS Macon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before the wreck of the Titanic was found on September 1, 1985, it was widely accepted the ship sank in one piece. When Robert Ballard started his search for the wreck in 1985, artist Ken Marschall painted this painting to submit to the National Geographic.

"Proposal painting of a sunken Titanic submitted to National Geographic in May 1985 in hopes that if the wreck were found that summer they might hire me to illustrate for the magazine. I was not."

Later, Ken drew several pieces of artwork of liner that was used in several publications.

Artwork by Ken Marschall: link, link, link, link, link

#RMS Titanic#Titanic#Olympic Class#Ocean Liner#Liner#passenger ship#ship#boat#September#1985#White Star Line#White Star#wreck#wreck of Titanic#my post#artwork#painting

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

When greetings go wrong

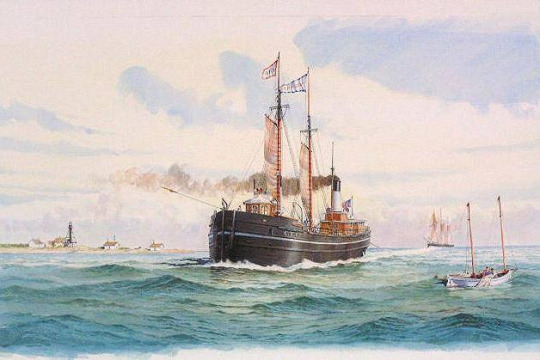

On 17 September 1892, the wooden steamer Vienna, loaded with iron ore and the barge Mattie C. Bell in tow, was underway at Whitefish Point, Lake Superior. Soon their commander noticed that a familiar vessel from the same company was coming towards them.

Vienna at Whitefish Point by Bob McGreevy (x)

It was the Nipigon with two barges from the Melbourne and the Delaware in tow. The Nipigon altered course slightly to greet the Vienna and pull ahead port to port, but in doing so she veered and rammed the Vienna hard on her port side.

The wreck of Vienna by Ken Marschall (x)

Immediately the barges were left behind and Nipigon tried to pull the badly damaged Vienna into shallow waters, but Vienna was too badly hit and sank within an hour. The entire crew was rescued unharmed, but Vienna is now lying about 45m deep in Lake Superior.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

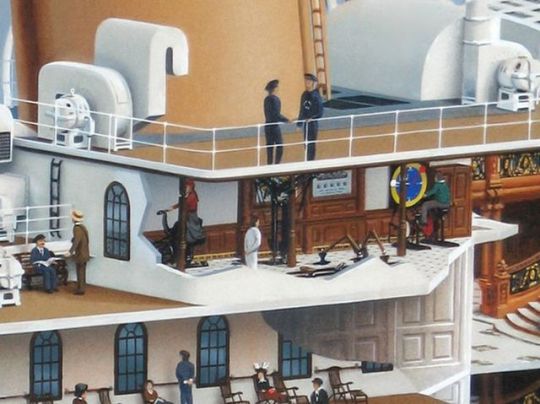

Bow section model diorama of RMS Titanic as discovered in 1985 condition. Based on the early artworks of Ken Marschall and model by Roy Mengot.

#ocean liners#oceanliner#maritime art#daryltoh#art#tohdaryl#titanic#tohdraws#titanicdiorama#titanicmodel#titanic wreck model#rms titanic#titanic wreck

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I follow a lot of blogs so sometimes its a long time between seeing your posts and i like it that way. Its a treat to go look through your more recent renditions.

I have a statement and a question. And follow-up questions.

1. I greatly respect your dedication to your renderings even as the titanic became newsworthy again last month.

2. Do you always use a reference or do you have it down by heart now?

3. If you do still use references are you more into photos or do you have a model that you use?

4. If you don’t use references anymore, when did you stop having to rely on those?

Excellent questions, thank you for asking!

Thank you. A few friends suggested I goose engagement by incorporating the imploded submersible into a drawing or two or use a stunt hashtag, but I thought that would be in poor taste.

I don’t really use references anymore. I find that looking at a reference every once and awhile helps me realign my memory as I draw. I also enjoy how, in the time between studying references, my recollection of a detail (bollard locations, deck transitions, size of portholes, etc.) will sort of morph into what I think is supposed to be there and then over time that morphed detail becomes a staple of dozens of drawings before I “correct” it, if that makes sense.

Photos, definitely. I have some models, too, but books and magazines are my go to.

When I first began this project I deliberately didn’t look at ANY references. I wanted to capture how I drew the ship when I was a little kid (mostly from memory or from a scant few physical sources.) As the drawings started to pile up I began looking more closely at photos and other renderings (Ken Marschall’s work in particular) for inspiration but never in an attempt to directly copy them.

Again, thanks for asking!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A(nother) Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration: Let’s Read “Into the Deep: A Memoir From The Man Who Found ‘Titanic’”

Because my main blog is still suspended, I very frustratingly cannot link to any of my previous posts about how Dr. Robert Ballard was one of my childhood heroes, the reason I majored in archaeology, and therefore ultimately the reason I am currently working for the National Park Service. But you CAN still hear me talk about all of those things starting at 14:28 in this video I made in 2017! (Thank you Vimeo.)

In an appendix to Into the Deep, Dr. Ballard lists 25 earlier books he’s written. Over the past two decades I have read and enjoyed 11 of them and own three others that are on my “to-read” list. I have read Ballard’s previous autobiography from 1995, Explorations: My Quest for Adventure and Discovery Under the Sea, as well as his two other quasi-memoirs, The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration (2000) and Adventures in Ocean Exploration: From the Discovery of the Titanic to the Search for Noah’s Flood (2001), which aren’t strictly autobiographies as much as histories of seafaring that have a lot of Ballard’s own personal anecdotes woven in.

When I saw this book in a bookstore window in Falls Church back in the fall of 2021, I was very surprised because I’d had no idea Dr. Ballard was planning to write another memoir. I bought it immediately, but felt a little bit uncertain.

Even with another 20 years of expeditions since his last self-reflective book, how many sea stories here would just be repeats I’d already heard in his previous books? The simple cover art of a wave also looked less visually-interesting than the covers of his previous books— no over/under shot of a ship and ROV together or Ken Marschall painting.

Well, he’s almost 80 years old now. I thought Maybe Dr. Ballard is finally running out of steam. Maybe it won’t hold up to the others.

After all, I was almost 30. It had been 25 years since the famous expeditions in the 90s that Dr. Ballard had written his children’s books about and almost 20 since I’d been a ten year old sitting cross-legged on the library floor reading them. Almost twenty years since I’d gone to his lecture at the National Geographic Society and gotten a signed book and expedition cap. Over time, his expeditions had seemed to get less and less publicity, even as they remained incredible and the technology he used continued to advance.

Even at age 11, as I’d sat on the library floor reading about Ballard’s 1990s expeditions in Lost Liners, they already belonged to the fast-receding pre-9/11 Former World. The brief shining moment captured in William J. Broad’s The Universe Below, when the Peace Dividend and the end of the Cold War opened up new opportunities to use Navy hardware, up to the point of nuclear submarines, for peacetime archaeology. I was never going to get to dive to the Britannic inside the NR-1 now and I knew it.

So maybe it wouldn’t seem as great as his earlier books. Maybe seas broad had rolled between since days of auld lang syne.

Maybe that’s why I left Into the Deep in my “To Read” list until I saw Dr. Ballard on TV again last month. Normally this would have been cause for celebration, but his interview was of course unfortunately in the context of the recent submersible accident.

The one bright spot in that twisted tale of fatal negligence and incompetence, for me, was that under the official ABC YouTube video of Dr. Ballard’s interview, there was a comment thread of people who were all a lot like me. People who said that Ballard had been one of their heroes as a kid and that now they were working in STEM or heritage fields because of him.

It was time to go along on another Ballard expedition.

Compared to Explorations, which I read in summer 2017, the prose in Into The Deep seems somewhat less descriptive. Some of this may be because of the different co-author, but as the first 3/4s of the book does cover a time period written about in Ballard’s earlier books, it may also be that he didn’t want to repeat himself and knew he had written about these periods better and in more detail there.

However, there are indeed many new stories in these years that I couldn’t remember hearing in any of Ballard’s earlier books or documentaries, and those were interesting. There’s a lot about his early family life, including feeling inadequate compared to his older brother Richard, who did better in school. (Imagine being ROBERT BALLARD and having Imposter Syndrome, my goodness…)

A few years ago, in his 70s, Ballard learned he was dyslexic, and reassessing his school days and most of the rest of his life in light of this knowledge is a theme throughout the book— it may have actually been his motivation to write the memoir overall.

This is, as I have noted, the first book by Dr. Ballard I have read to include an F-bomb, and there are a few other scattered swears, but compared to a Jimmy Spithill or a Skip Novak his “sailor mouth” seems quite restrained. Still, my younger self wouldn’t have liked that at all.

Some of Ballard’s military career has been declassified, and thus those stories can be told. Indeed, this feels like a much more militaristic book than Ballard’s prior memoirs, with more appearances of weapons, military ranks and uniforms, and more meetings inside the Pentagon.

Some of this is simply because the aforementioned declassified information can now be revealed, but the militaristic turn may also reflect the end of the peacetime period in which Explorations (and Ballard’s juvenile nonfiction books) were written, and how his 21st century expeditions have therefore required Ballard to draw closer to his old military contacts to gain funding and access to equipment.

Robert Duane Ballard (born June 30, 1942 in Wichita, Kansas) is an oceanographer most noted for his work in underwater archaeology. [Wikipedia before November 2008]

-

Robert Duane Ballard (born June 30, 1942) is an American retired Navy officer and a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island who is most noted for his work in underwater archaeology: maritime archaeology and archaeology of shipwrecks. [Wikipedia text as of July 2023]

This is not, of course, to suggest that the specter of war was absent from Ballard’s earlier books or documentaries. Many of Ballard’s most famous expeditions have of course involved ships whose sinking was an act of war— the Bismarck, Lusitania, Britannic, and JFK’s PT-109— and the role of the Navy in DSV Alvin’s development and the Thresher and Scorpion investigations are (contrary to later popular perceptions) discussed forthrightly in The Discovery of the Titanic back in 1986.

Yet the wars in those books and films felt more distant and unthreatening. The wrecks of the warships had been at peace for half a century or more, their weapons corroded, overgrown, and silent. The survivors we saw photos and video of were old men and women, sometimes veterans from opposite sides who were now friends, living in now-allied nations. After all, a modern war between Great Britain and Germany or the United States and Japan has not seemed very likely at any point between the 1980s and the present.

The “Peace Dividend” atmosphere of the 90s expedition books and documentaries, of technology developed for the Cold War now being used for peaceful exploration and archaeology, also felt cheerful and encouraging to my younger self in the same way as Russo-American collaboration on the International Space Station.

Around the same time in the early 2000s that I was reading Ballard’s children’s books from the 90s, I was also reading through my godmother’s gifted collection of National Geographic back issues. A January 2002 article about the adoption of the Euro made a great impression on me because it begun with a visit to the military cemetery in the fields of Flanders and a photo of the seemingly endless white marble headstones row-on-row before moving to EU business underway in Brussels— “A new Europe, in a new century.”

However vaguely or naively, my ten-year-old self did take to heart these different expressions of the Dream of the 90s that perhaps after the horrific war and suffering of the 20th century, the 21st might be a more peaceful one.

The tragedy of Into the Deep, as we get into the last quarter of the book covering Ballard’s career since the 2002 publication of Adventures in Ocean Exploration, is the small reminders scattered through this “new” material of how real life has fallen short of our Millennial dreams.

Ballard’s early-2000s Black Sea expeditions were the point at which I began following his adventures in real-time, as my own subscription to the Geographic started in January 2004, and the May 2004 article “Being Bob Ballard” covered the previous year’s expedition in search of ancient shipwrecks preserved in that body’s anoxic depths.

The various contemporary sociopolitical overtones in coverage of these expeditions— culture warriors debating whether the theory that rapid flooding of the Black Sea at the end of the Ice Age had inspired the story of Noah’s Flood would strengthen or disprove Creationism, a Turkish official’s joke to Ballard “Is it true you’re here for oil?” “Yes, 3000 year old olive oil.”— were mostly lost on my younger self. Something I did grasp, but only vaguely, was the remarks that such an expedition to the Black Sea by American scientists would have been impossible during the Cold War. However, the shape of the Black Sea itself, roughly a little like a lima bean, with Crimea a pointy triangle-diamond bite into one side, was burned into my brain, along with the maps of its deep-water contours with markers showing the locations of ancient wrecks.

While the theory of rapid flooding of the Black Sea at the end of the Ice Age has since been questioned and now looks less likely, gathering data points even if they prove your pet theory wrong is all part of the progress of science. The preserved shipwrecks with intact wood discovered by Ballard’s expeditions were indeed useful to archaeologists and astonishing to the public, myself included. (Unfortunately, since Ballard’s focus shifts so suddenly and understandably to the shipwrecks of the Black Sea, Into the Deep does not mention any later research into the deluge theory.)

The intrusion of contemporary war into Into the Deep comes in a description of a later expedition to the Black Sea in 2012. While doing the same shipwreck research as a decade before, Ballard was suddenly called by the US Ambassador to Turkey and asked to find and investigate a Turkish fighter plane recently shot down over the Mediterranean during the ongoing Syrian Civil War. Syria and Turkey, we are told, were threatening to go to war over this incident, depending on whose airspace it was in at the time. The jet was found and tensions diffused, and while thankfully no pictures are included, Ballard describes the sight of the crab-chewed bodies of the pilots as “unpleasant”. Three members of Ballard’s crew, we are told, asked to take leave and considered seeing psychologists after studying the jet crash site.

This is not the silent and corroded guns of the Bismarck or the rummy eyes of an old British woman explaining how she survived the sinking of the Lusitania as a child, all safely consigned to the pages of history. This wreck belongs to a raw, gruesome, and ongoing war with still-fleshed bodies and an uncertain outcome.

In the past decade, Ballard says, politicians have looked down on NOAA funding for such far-flung expeditions, in favor of the exploration of US territorial waters. This, together with an increase in piracy in the Indian Ocean, led to the cancellation of planned expeditions to that part of the world. Most of his subsequent work has therefore been in US waters.

In late 2016, searching for escapism, I rewatched one of the 2003 Black Sea documentaries on YouTube. One commenter noted that such an expedition might be hard to organize in the present day after the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. Ballard does not discuss this in Into the Deep, but surely similar thoughts must have occurred to him.

This is probably even more true today in light of the current Russo-Ukrainian War. A contemporary discussion of “shipwrecks in the Black Sea” is more likely to be about casualties of the current war than the ancient ships Ballard studied 20 years ago. Perhaps, as horrible as it is for me to contemplate, many younger Americans will grow up with this war, rather than ancient wrecks preserved in poison or a search for Noah’s flood, as their first thought whenever the Black Sea is mentioned.

What is in Into the Deep that was not in Ballard’s earlier books, then? Sadly, for me, one of the most notable things is the reminder of the violence in our world and that, in et in Arcadia ego fashion, even the escapist world of Dr. Ballard’s expeditions is not completely insulated from that violence.

#books#reading#Ballard is Beast!#inner space#For the Increase and Diffusion#writing#Into the Deep#Let's Read

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was a kid, I read a little bit of anything and everything that looked interesting. Right around the time I was ten, I picked up “A Night to Remember” by Walter Lord, the quintessential book on the sinking of the Titanic. This is also around the time Bob Ballard and his team located the wreck of the ship, so National Geographic and a bunch of other magazines were publishing articles and photos and artwork regarding the ship and the sinking.

I. Was. Hooked.

Now, this is pre-1997-Leo-and-Kate Titanic mania, but my parents latched onto “Jennifer likes Titanic” and got me every possible book they could on the ship. A lot of them were coffee table books with lots of information and beautiful artwork of the ship and the wreck by Ken Marschall. Some of the books covered the Lusitania and Britannic and Empress of Ireland, so now I’m not just Titanic girl, I’m shipwreck girl.

I was also into baseball and was watching the World Series in 1989 when the earthquake struck live on air. So I start diving into earthquake research. Then volcanoes. Then building fires. Then plane crashes. Before long, if it’s a book about a disaster, I’ve read it.

The thing is, it was never morbid. It was never like, “Look at these photos of the burned dead from the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire! Isn’t it gross?” It was, “Here, let me tell you about the woman who organized the factory workers to strike before the fire!” or “No, but you should know the names of the elevator operators who saved so many lives!” or “Listen to what the bosses did that put everyone in such danger, all to save a buck!”

My therapist once asked me why I’m interested in disasters when they’re so incredibly depressing. Which, yes, of course, they are, but also there’s hopeful stuff there too. People who survived despite the odds, problems which were found and fixed because these terrible things happened, memorials which were built to remember those who died. That’s what I end up getting hooked with - the final survivor they pull out of the wreckage, the person who does something gallant to help others even if they know doing so will sign their own death certificate, the people who show up with whatever they can to help out even if it probably won’t be useful because they feel like they have to do *something*.

Like, there’s so many depressing things going on in the world all the time, and I can’t always find the good in those stories all the time. But with Titanic, for example, I can think about the Strausses staying together in the ship because they refused to be parted or take a seat from a younger passenger. With the Triangle Shirtwaist factory, I can think about Clara Lemlich, a certified badass who unionized garment workers in the early 1900s in New York and led the Uprising of the 20,000 in 1909. (She even organized the workers at her nursing home in her old age. She was kind of amazing.)

So when I went back to college, one of the classes I had in my final semester was a literature class focused on nature writing. One of the books we read was “Into the Wild.” (Which I love as a book, but haaaaate because McCandless’s actions frustrate me to no end, but whatever.) Our final assignment was a presentation on a different book by an author we already read in class, so I did “Into Thin Air.” I did background on Everest exploration, the events of the 1996 disaster itself, memorials, and things which have been improved since then as a result.

I was only supposed to do ten minutes. I think I did twenty.

Now, I’m not a good public speaker. I’m nervous and stutter and get anxious being stared at. But that presentation was easy to give, because I wasn’t just interested in the subject matter, I’d literally read the book a half-dozen times before AND watched multiple documentaries on the 1996 disaster. I could have done the presentation without even doing the research. Even now, I could do a thirty-minute talk on dozens of disasters without any prep whatsoever.

When I got done and sat down, my teacher in the next seat leaned over and said, “You’re such a good storyteller.” I was grateful, except … I’m not. I’m really not. At least, not all the time. I have to be VERY into what I’m talking about. I’ve dictated to my phone at least part if not all of three books this year.

But I can tell THOSE stories. I can tell survival stories, I can tell rescue stories, I can tell stories of victims getting justice. Because look at what people can be! Not everyone is an unrepentant douchebag! Maybe everything’s NOT a big bag of ferret shit! Like, do some people suck? Sure. Do terrible things happen? Every day. But do good things happen in spite of all that, literally in the middle of the world falling apart? Weirdly enough, yeah.

Also, it’s grossly unfair that we skip over learning these stories because they’re depressing, and in the process allow the victims to be forgotten over and over again. The story of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory is one full of strong women who started over in a new country and were doing what they could to take care of their families, and people down on the street who did what they could, and Frances Perkins! The first female cabinet member who served as secretary of labor under FDR! Who was hardcore into workers’ rights and safety because the day of the fire she was having tea at a friend’s home nearby and went out to see what was going on and had the image of jumping girls burned into her mind.

Someone in the notes of that other post I made for the podcast questioned if it was informative or exploitative. I mean, aside from the answer I could have given, which is I don’t know, listen and find out? I get the worries of exploitation in darker non-fiction stories, especially given we were all just talking about the Dahmer miniseries being exploitative as fuck. But me personally? I’m pretty much in it to tell you true stories from history and share donation websites and remember the deceased and warn people how to respond to disasters and assure you air travel’s safer than it’s ever been and basically do exactly what I normally do to my coworkers and relatives and people I meet at parties when I actually GO to parties.

If no one listened to the podcast, if it was just me researching and recording it and that’s it, it’d still do me the service of allowing me to get excited about something, which so very often I find far too difficult. It gives something to focus on, to aspire to, and I’m so proud of it turning seven years old at the end of December.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This painting by Ken Marschall beautifully illustrates how the wreck of Italian liner Andrea Doria would likely have appeared in the hours and days immediately following her loss, with many pockets of air still escaping from inside the gleaming hull and with her pretty lines still razor sharp and as new. Diver Peter Gimbel became the first explorer to reach the site at around 10.00 AM on the 27th of July 1956, just under twenty four hours after the vessel had come to rest on the sea floor. He reported ghostly scenes of loose luggage, paper, bedding, and curtains floating freely around the wreck, escaping oil, and a great quantity of rising bubbles, the trails of some of which he used to locate sections of the ship 250’ (76m) below the surface of the Atlantic.

Of very interesting note is the story of the port side lifeboat seen here pointing upright at center, the craft held aloft above the ship by its intact inner buoyancy tanks. During the evacuation of the Andrea Doria, an immediate list of nearly twenty degrees and worsening prevented the use of all boats on this side of the ship, and most eventually floated away as the liner went under. This lone example however was pulled down with the Doria, and was photographed by Peter Gimbel and others with its buoyancy tanks slightly crushed by pressure but intact. The lifeboat remained in this position for nearly twenty five years until finally breaking free of its rotted lashing and rising to the surface sometime during the spring of 1981. The drifting boat then went unnoticed for some number of weeks before being discovered by Con Edison workmen, washed ashore on New York’s Staten Island on the 1st of July and reportedly remaining in almost usable condition.

Painting by Ken Marschall

0 notes

Text

oh ken marschall's titanic paintings my beloved

0 notes

Text

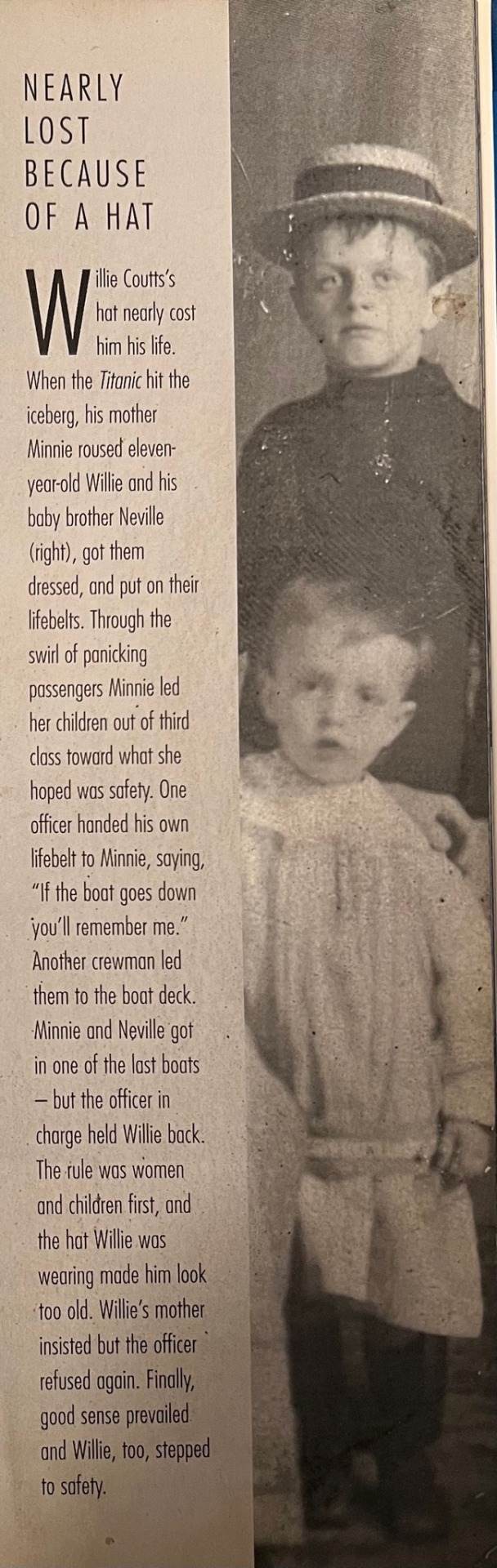

Pictures of my favorite Titanic passenger, Willie Coutts, with his brother Neville Coutts, (Excerpt: “Nearly lost because of a Hat”), from the book, “Ghost Liners: Exploring the world’s greatest lost ships”, by author’s Robert Ballard and Rick Archbold with paintings/illustrations done by artist, Ken Marschall!!! ❤️ One of my favorite books!!! ❤️

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Today in History: April 13, 1912

After the Marconi wireless apparatus stopped working at 11 p.m., the ship’s wireless operators violated Marconi company rules by working on the repairs themselves. The next morning around 5 a.m. the wireless is working again. After breakfast Captain Smith conducted his daily inspection of the ship. Chief Engineer Joseph Bell informed Smith that the fire that had been raging in Boiler Room 6 since before the ship left port has finally been extinguished. However, the bulkhead had been damaged. This bulkhead’s failure on April 15 would play a key role in the ship’s demise. The Titanic continues her voyage through calm waters. 1 day remains until her foundering.

#rms titanic#White Star Line#today in history#Harland and Wolff#titanic#olympic class steamers#RMS Olympic#captain edward smith#captain ej smith#bulkhead fire#titanic fire#april 1912#mypost#this day in history#ken marschall#Marconi Wireless#watertight bulkheads#history#sinking of the titanic#rivet-ing-titanic

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

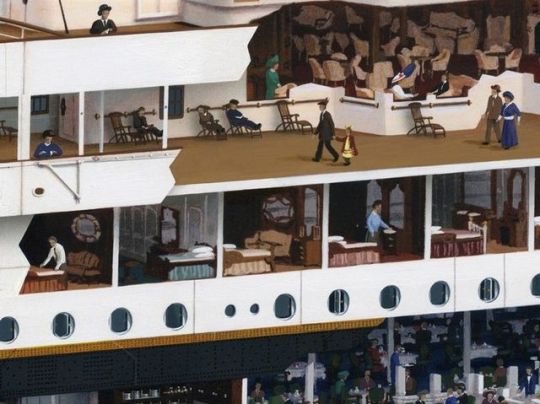

I love this shot of my 1/360 scale Titanic model build. Reminds me of artist Ken Marschall's work on the bridge in this angle.

#maritime art#daryltoh#oceanliner#art#ocean liners#titanic#tohdaryl#tohdraws#titanicdiorama#titanicmodel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One day, I’d like to become next Ken Marschall

... but instead of digital platform, I’ll stick with oil painting. And instead of “oil on canvas”, there will be written “oil on bedsheets” beside the artwork on the wall because I have found a huge supply of bed linen made exclusively for Tuzex in 1970s in my grandma’s cupboard which may last me for a few years. I must tell you, many of those sheets are of better quality than canvas you can purchase in art supplies.

As to my love for ocean liners, let us say that if I said a word to my [nonexistent] psychologist, my diagnosis would be obsession bordering with madness - that would not be too far from home since it sometimes drives me nuts when I cannot reproduce some pattern or detail perfectly. I guess this is one of perks of being a perfectionist...

1 note

·

View note

Photo

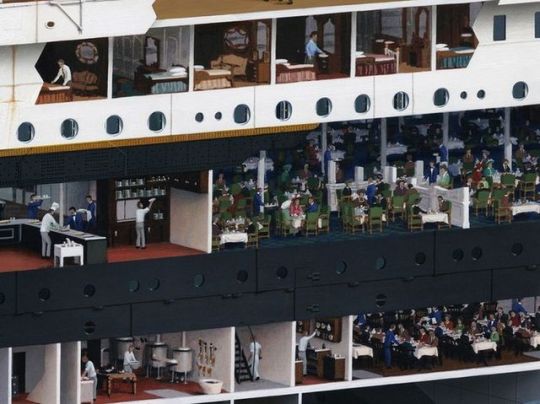

My Favorite book when I was a little boy by ken Marschall

#Ken Marschall#Titanic#Architecture#engineering#section drawing#section cut#illustration#illustrator#drawing#painting#rendering#render#design#interior design#interior section#Cut away#1912#1900s

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ken Marschall seems like such a lovely human being.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 notes

·

View notes