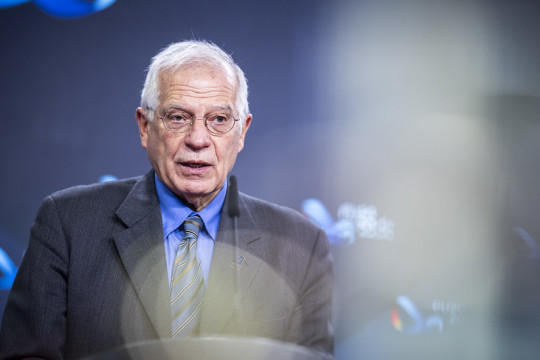

#Josep Borell

Text

Josep Borrell: Izrael éhínséget idéz elő Gázában

Izrael éhínséget idéz elő a Gázai övezetben, a lakosság kiéheztetését háborús fegyverként használja – jelentette ki az Európai Unió kül- és biztonságpolitikai főképviselője Brüsszelben, az Európai Humanitárius Fórumon elmondott beszédében hétfőn.

Josep Borrell a kétnapos brüsszeli rendezvényt megnyitva hangsúlyozta: elfogadhatatlan, ha civilek kiéheztetését fegyverként használják bármely háborús…

View On WordPress

#éhezés#Európai Unió (EU)#Gázai övezet#Izrael#izraeli-palesztin konfliktus#Josep Borell#palesztinok#Vaskardok gázai háború

0 notes

Text

Mesaj fără precedent! Borrell sacrifică europenii pentru Ucraina VIDEO

Șeful diplomației UE a lansat un mesaj care nu lasă nici un fel de interpretări. El cere, nici mai mult, nici mai puțin, ca toți banii UE să meargă către Ucraina.

Georgiana Arsene

Ucraina se va prăbuși în câteva zile dacă UE nu va mai furniza bani. UE nu are de ales: trebuie să cheltuim toți banii pentru a proteja Ucraina, a declarat Borrell.

Pe aceeași temă:

Șeful diplomației europene nici…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Josep Borrell'den Türkiye'de geçen görüşmeler için açıklama

Josep Borrell’den Türkiye’de geçen görüşmeler için açıklama

Josep Borrell, yaz tatilinden önceki son AB Dışişleri Bakanları Toplantısı’nın girişinde basın mensuplarına konuştu.

Ukrayna Dışişleri Bakanı Dmitro Kuleba’nın da sabah oturumuna katılarak özellikle tahıl ambargosuyla ilgili bilgi vereceğini aktaran Borrell, bu hafta Türkiye’de yapılacak görüşmelerle ilgili bir soruya, “Bu hafta Odessa ve diğer limanlar üzerindeki blokajın kaldırılması için bir…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

by Jacob Magid

A senior European source tells The Times of Israel that the decision announced earlier today by European Union Commissioner Oliver Varhelyi to immediately sever all EU aid to the Palestinians will not be implemented, due to opposition from member states.

Varhelyi is a diplomat from Hungary, which takes a much more hawkish approach toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than many of the 27 other members of the EU.

The senior European source speculates that Varhelyi’s decision will be walked back tomorrow when the EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borell meets with European foreign ministers.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Josep Borell az Európai Unió külügyi és biztonságpolitikai főképviselője: Történelmi jelentőségű találkozó, az EU 27 külügyminisztere találkozik Kijevben.

A Lavrov-díjas Szijjártó Péter külügyminiszer eközben:

Roppant fontosan tűnő találkozón vesz részt a német ThyssenKrupp AG képviselőivel - Budapesten.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve largely avoided writing anything too topical about the conflict in and around Ukraine, because I dislike polemic, and anyway I don’t have enough technical knowledge to write about day-to-day military issues. Nonetheless, I can’t help being struck by the sense of disorientation and intellectual befuddlement that a lot of western writing about the fighting displays. In turn, this comes, I suggest, from a fundamental western unwillingness to do the hard work of learning about strategy and the political uses of military force, and to raise one’s eyes from the exciting bangs and booms, advances and retreats on the battlefield, and to look at the big picture.

So here, I’m going to try to take a step or three back, and talk about the biggest of the big pictures, and try to show how various political and economic factors have to be taken into account in understanding what I think the Russians are trying to do. Whatever your views on the conflict, it’s very hard to say anything useful about it (I’m looking at you, Josep Borrell, for example) unless you make an effort to understand the importance of these factors.

Fortunately, others have been this way before in writing about strategy, and nobody more fruitfully than the great Prussian soldier and military theorist, Carl von Clausewitz. Now one reason Clausewitz is important is that he is part of a very select group of theorists and historians, including Machiavelli and Thucydides, who were practically involved in the things they wrote about. Like them, he is referred to much more than he is read, and misunderstood even when he is read. But Clausewitz was the first important theorist to get away from detailed writing about tactics, and ask (and indeed answer) the question, what is war actually for? And why do states resort to military force? His answer was simple: war is “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.” We want our enemy to do something, or stop doing something, and so, says Clausewitz, we must put our enemy in a “situation that is even more unpleasant than the sacrifice you call on him to make.” In addition, he adds, this situation cannot be a transient one, where the enemy can simply wait for things to improve, but one where the enemy is effectively defenceless, or likely to become so.

But Clausewitz insists on the need to situate war in the context of state policy generally (not “politics” as politik is often wrongly translated here). Wars start, he says, because of some “political situation, and the occasion is always due to some political object.” Thus, “war is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse, carried on with other means … The political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and the means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose” (my italics). Although On War is a forbidding text, these citations (in the standard Howard and Paret translation) are all taken from Book I, and you can download an older public domain translation of that Book and read it in an hour. (Maybe Mr Borell’s office should consider doing that.)

After doing so, things become immediately much clearer, and a number of the questions not asked by western media and politicians become obvious. What, for example, are the larger Russian political objectives? How significant is the current fighting in Ukraine, and indeed how significant are individual battles? What parallel activities are going on, politically and economically, all tending in the same direction? And what vision do the Russians have of the situation they want to bring about—what Clausewitz calls the “end-state”?

But why are these questions not being asked on a systematic fashion by the West? After all, if it wants to frustrate Russian plans, it might make sense to try to deduce what those plans are, and how the Russians expect to bring their end-state about.

The answer, I think, comes from a mixture of two factors. First, much of the policy impetus on Ukraine comes from Anglo-Saxon countries, whose history of warfare, and thinking about warfare, is essentially expeditionary and limited. Apart from very brief periods in 1916-18 and 1944-45, the British and Americans never had to consider the use of large land and air forces, and develop a doctrine for their employment. Historically, military expeditions were small, with limited objectives, far away from the motherland. The Falklands War of 1982, for all that it was a remarkable military achievement, fits very much into this tradition, of small-unit tactics, individual leadership and battlefield improvisation.

The type of military operations that Europeans have actually conducted since 1945, and especially since 1989, have tended to follow this model. Although generations of NATO officers planned and exercised for apocalyptic confrontations with the Warsaw Pact, those countries that actually carried out real-life operations became involved in much lower-level counter-insurgency or peacekeeping missions. And when Europeans, still a little dizzy from the fall of the Berlin Wall, started to think about what tasks their militaries might perform in the future, their best guess was more of the same: peace missions, military-assisted evacuations, crisis-management deployments, and so on. And so national service and large armies were abandoned, high-intensity large-scale warfare stopped being studied except as history, and careers were made from leading small groups of soldiers on missions far way.

The second factor is simply that in general the West’s wars have been limited liability ones, where there have been few casualties at home. True, the wars in Algeria, Angola and, arguably, Vietnam, produced political convulsions and brought down governments, but the actual death and destruction almost all took place somewhere else.

For the Russians, geography mandated a different set of criteria. Always a massive country with a relatively large population and long borders, the nation has suffered foreign military invasions repeatedly in its history. It is used to being obliged to fight on its own territory, and in World War II alone, suffered nearly thirty million dead, a large proportion of them civilians. Thus, national defence is literally a life and death issue, and thinking about, and planning for, war, takes place at a massively higher and more complex strategic level. It’s also worth pointing out that the formidable edifice of Marxist-Leninist Military Science has not lost its influence, and Marxism was above all a doctrine based on the predominance of tangible material forces.

This Russian experience inevitably produces a way of looking at conflict which is radically different from western one, with the proviso that the West itself has had to painfully learn similar lessons during two World Wars, only to promptly forget them each time. War is seen in a total sense: as a political, economic and military struggle combined. Sheer numbers, political discipline, massive reserves of manpower and equipment, total mobilisation capability and long-range and ambitious strategic planning are inevitable features of such an approach, so if we want to see what the Russians are after, it would be as well to include these factors. The end-state is, by definition, not military, and thus the military may contribute to that end-state in a wide variety of ways. Victory on the battlefield may not be the overwhelming priority, if other factors are operating in your favour, and the employment of large forces over a wide area will itself impose a higher-level way of thinking. For example, giving battle, even if you think you will win, may be a bad idea if it uses up units and equipment which are going to be badly needed elsewhere. Better to withdraw. Conversely, inviting an enemy attack on your positions, even if it is tactically disadvantageous, can be a good idea if you inflict heavy casualties that your enemy cannot replace.

The Soviet and Russian militaries have a long tradition of studying the terrible past wars of their country, and there are a number obvious conclusions from any such analysis. One is the importance of sheer numbers, of personnel, of equipment and ammunition. In a long war, which the Russians, unlike the West, have always expected to fight, these things matter a great deal. In the Cold War, the Red Army planned to win by a tactic known as echeloning. Essentially, you send your best forces in first, and they are mostly destroyed, but destroy the enemy’s best forces as well. Then you send in your second echelon, and mop up the enemy’s remaining forces, even if you lose most of yours. Your third echelon has effectively no opposition, and you win. (This would not have surprised Clausewitz, who argued that it was important to be “strong everywhere, especially at the decisive point.”) Likewise with ammunition stocks. If you have two million rounds of ammunition and your enemy has half a million, your enemy is going to run out before you do, after which you will have dominance. The West has opted, since the late 1940s, to have fewer weapons and less manpower, hoping that quality will trump quantity. During the Cold War, it also planned to use tactical nuclear weapons early, since it could not accept the economic burden of maintaining massive conventional forces as the Soviet Union did. Whether all that would have worked in the Cold War we will, thankfully, never know, but clearly it is the very opposite of the policy the Russians have been pursuing recently.

If this sounds like industrial-scale warfare, that is exactly what it is: and literally so, in that the importance of war production was another lesson from 1941-45, where the Soviet Union out-produced the Germans in military equipment even after moving its factories East of the Urals. Moreover, Soviet and later Russian equipment was designed to be operated by conscripts, and therefore was kept relatively simple, so that it could be employed in very large numbers. We are seeing the results now in Ukraine, where T-62 tanks, kept in reserve for many years, are being sent to the Donbas to be operated by local militias and recalled reservists with lower standards of training. The West has opted for platforms which might individually perform better in combat (so far, nobody knows) but are much more complex and difficult to operate and maintain. Among other things, any attempt to greatly expand western forces in the future would require a complete rethink of concepts like ease of use, training time and maintenance of equipment.

The West has an intrinsic difficulty with this kind of approach. Notably, its tradition of military history and theory is focused much more on battles than campaigns, much more on leaders than on forces, much more on stories of individual weapons systems than on war production. Even historians writing about the Eastern Front in WW2 still tend to write about individual battles (notably Kursk), whereas the best accounts (by Chris Bellamy for example) correctly focus on the campaign level. Indeed, it’s been persuasively argued that individual battles in that terrible conflict largely only affected the precise timetable, and that underlying factors dictated the result from the start. Notably, the catastrophic German underestimation of the size and fighting power of the Red Army, and the Wehrmacht’s inability to finish the campaign by the beginning of the Autumn, have been argued to be much more important limitations than victory or defeat in any single battle. That’s as may be, but it’s clear that even that sort of approach is completely foreign to the intellectual framework of those western commentators following every video, every rumour, every twist and turn of the bloody game that’s being played in Ukraine. It’s hard to find an appropriate metaphor: perhaps music critics arguing over the costume of the prima donna in an opera, without mentioning whether the production was finally greeted by flowers and a a standing ovations, or by the cast being pelted with rotten eggs.

Finally, the Russians are operating, to repeat, in a Clausewitzian tradition, which sees military force only as useful when it is clearly tied to a political purpose. (And a purpose is not just an aspiration.) The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, for example, included a clear political strategy for building support for the new regime among the professional middle class, reforming the state and the political system and creating effective security forces. In the end it didn’t work, at least not after the fall of the Soviet Union, but it was at least a strategy. By contrast, the kind of plans for Afghan reconstruction that that I remember seeing circulating in the West in the 2000s, were just a series of loosely-connected aspirations, where it was assumed that the arrows on Powerpoint slides actually represented some kind of causal relationship. Much the same was true at the time of the Iraq War (although the US State Department had done its best). In Washington, the future of Iraq was seen in terms of a series of concordant and sequential fantasies, with no idea how they were to be brought about. Mostly, this was because Liberalism always assumes that certain political elements exist universally, and that once the Bad Guys are removed from power, nations will develop automatically and ineluctably towards a liberal democratic model. This is still very much the view today. If you have anything to do with ideas trading as Post-Conflict Reconstruction or Peace-building, especially as marketed by organisations like the UN and the EU, you’ll be presented with a series of sequential steps towards a hypothetical utopia, but with nothing holding them together. So for example a Ceasefire is shown as leading to Demobilisation, then to Restarting the Political Process, then to Elections, then to Stability. But if you ask precisely how a ceasefire will lead to restarting the political process (or indeed why it should do so) you’ll be greeted with an embarrassed silence. And of course in real life it generally doesn’t: it’s odd that it’s Liberalism, rather than Marxism, that seems to believe in historical inevitability.

So if that’s the tradition the Russians are coming from, and that’s why the West has difficulty understanding what it’s seeing in Ukraine, then what does that tell us about the type of wider and longer-term plan the Russians are likely to have, and how they will go about it? Two qualifications need to added though, before we start.

First we should avoid the temptation to assume “masterplans” everywhere. It’s easy to fall into conspiracy theories about the Illuminati, the Bilderberg group, the “Anglo-Zionist cabal,” or some plot to destroy Europe’s economy masterminded from Washington. But that’s the stuff of airport bestsellers, not real life. Second, and partly as a consequence, we’re not talking here about some complex and detailed plan over generations, but rather a series of relatively straightforward objectives at different levels, consistent with Russian statements so far, and with a sensible unbiased look at what their security objectives obviously are. As good students of Clausewitz, we would expect the Russians to consider war at all its levels, so let’s lean on him again as our guide.

Consider first what Clausewitz said about the need for victory to be complete, and definitive, to avoid the enemy being able to restart the war. And here we recall that, in 1945 the Red Army did not stop at the Russian border, but went all the way to Berlin, where it occupied half the country and installed a puppet regime. This kind of conclusion to a war is actually not unusual: in 1814, Russian troops actually occupied Paris after the final defeat of Napoleon. It is only in recent decades that fully inclusive peace settlements dealing with underlying causes of conflict, with the participation of vulnerable groups, and complex peace-building regimes after detailed negotiations and all-embracing peace-treaties, has become the norm. The latter will certainly not happen this time, which is why we need to be very careful how we employ the word “negotiation”, but neither is it likely that the Russians will want to physically occupy any more of Ukraine than they have to. So what would complete victory mean, in this sense?

Following Clausewitz, the first variable would be that of time. For the Russians, Ukraine must be left in a situation where it is incapable of posing a threat in any reasonable length of time. It’s hard to be precise, but twenty-five years sounds about right. Now, even if the Russians do nothing more, the best guess is that it would take a good ten years to reconstitute the Ukrainian forces to something like their February 2022 level of effectiveness. But note that this implies the availability of massive funds (which Ukraine does not have) or massive, organised and sustained aid from abroad, including either substantial diversions of new armaments from the already-depleted US and European militaries, or substantial investments in new production facilities especially for Ukraine. Neither seems very likely. In addition, a new generation of officers would have to be recruited and trained, military infrastructure repaired or newly constructed, and a wholesale process of conversion from ex-Soviet to western military equipment, together with the associated operational doctrine, would have to be developed. And of course the basic infrastructure of the country would have to be repaired in order for the military to function at all. The chances of achieving that at all, let alone in as short a period as a decade, are not great.

So the problem may solve itself. However, it’s probably not in Russia’s interest to have Ukraine completely disarmed, because that would lead to potential instability, which could spill over into Russia itself. Whatever government succeeds the current regime in Kiev will have to be able to control its own territory. So the Russians may force a peace treaty on Ukraine which, for example, includes the creation of a professional gendarmerie, allowed to operate light armoured vehicles and helicopters, but no more. Attempts to develop or acquire more powerful systems would be impossible to hide, and easy to squash. This is a much more elegant and much cheaper solution than attempts to construct massive fortifications or occupy non-Russian speaking territories.

However, it’s been obvious for a long time that Ukraine is only the visible part of the strategic iceberg, for both sides. The West wants, roughly, a return to the 1990s, and the end of an ideological and strategic competitor. Russian aims obviously include frustrating that, but almost certainly go much farther. Unlike many people I have no idea what’s in the collective heads of the Russian government, but it’s possible to make some broad deductions from the draft treaties the Russians circulated in December last year. These are treaty texts, and drafts at that, so it’s unlikely that they constitute anything more than a wish-list of objectives that in reality would probably have to be adjusted downwards. But we can make some reasonable inferences.

The principal Russian objective in Europe is to be the local military superpower, in a Europe which is militarily weak, partly dependent economically on Russia, and does not pose a military threat. So far as Western Europe itself is concerned, we are not far from that now: only Ukraine could have been said to have posed a military threat, and that is no longer the case. The idea would then be to convert the ring of countries around the borders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (in practice, the Baltics, Rumania and Poland) into effective neutral states, without foreign troops stationed there. This would not necessarily mean these countries leaving NATO, because US troops, for example, are stationed in non-NATO countries anyway. Rather, there would be an unspoken agreement (as with Finland during the Cold War) that these states would behave themselves with respect to Russia. One component of this solution would be the withdrawal of the relatively small numbers of US troops still in Europe. This is likely to be part of the parallel aim of effectively destroying NATO as an alliance, by showing that, in practice, it has no military utility, and by extension that what is generally called the American “security guarantee” is worthless. Note that this does not mean that NATO cannot survive in some dormant and vestigial form: it’s unlikely the Russians would object to that.

In all of this, we need to bear in mind one other concept of Clausewitz: the Centre of Gravity. Clausewitz wrote a lot about this in different parts of On War, but the easiest way to conceive of it, is as the most important target of the war, on which everything else depends. It is “the ultimate substance of enemy strength” on which the greatest possible effort should be concentrated. Clausewitz notes that this may be, but does not have to be, the enemy’s military forces. At the end of the book, he mounts a strong defence of Napoleon’s decision to enter Moscow in 1812, rather than to pursue the defeated Russian Army. No conceivable military victory, he argues, could have knocked a country the size of Russia out of the war, while taking and holding the enemy capital could have done so. In the end, he accepts the plan failed, but only the capture of Moscow was actually worth trying. Had the Tsar and the aristocracy been as shaken by the loss of the city as Napoleon hoped, the war would have been over. That was the Centre of Gravity.

Clausewitz also notes that the Centre of Gravity may be the delivery of a blow against a more powerful ally. So in the case of operations in Ukraine itself, this means the willingness of the West to continue supporting the regime in Kiev militarily, politically and economically, because if that stops, so will effective Ukrainian resistance, and that will open the way to other strategic objectives. In a war where both Russia and the West are careful not to strike each other directly, this willingness will have to be attacked indirectly, effectively by persuading the West to give up, because success is impossible. There are precedents for this, although they may seem surprising. The NVA/VietCong forces fighting the US and the South Vietnamese forces were well aware that they could not win a conventional military victory. What they could so was to bring the Americans to the point where they realised the struggle was hopeless, just by continuing the war, and inflicting political and economic damage on the US itself. This they duly did. The situation was quite similar with the French in Algeria and the Portuguese in Angola: both were militarily dominant, but each war ended with political and economic exhaustion and a change of government. Afghanistan is a more recent example of much the same approach. So here, the Russian objective is probably the political and economic exhaustion of the West to the point where further support of Ukraine seems useless, or even impossible. And whilst it may not have been part of the original plans, it’s hard to believe that the Russians would regret the West continuing, for at least a while, to weaken itself militarily and economically in a hopeless cause.

So at that level, the Russians are presumably seeking to make the West give up any hope of a solution favourable to them. This means they have no incentive to compromise, or to agree to peace talks. In effect, they only seek to dictate peace terms, perhaps along the lines sketched out above. If the West does not give up, operations in Ukraine will continue as long as necessary. At a higher strategic level, the Russians probably also intend for the War to go on long enough to make NATO’s weakness, and the impotence of the US, transparently clear, such that it can more easily accomplish the kind of wider objectives I have just outlined, as well as weakening western economies.

Now, I have no idea whether this is actually what the Russians are intending to do: I can only say that it seems entirely possible to me. This is, after all, a society that takes Clausewitz more seriously than Harry Potter, and Tolstoy as a better guide to war than Twitter. And I have no idea whether it will succeed. But more importantly, if the above analysis is even remotely correct, then the West is intellectually and politically badly equipped to understand what the Russians are doing, let alone react effectively to it.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell told media that the meeting on Thursday in the Belgian capital between Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic and Kosovo Prime Minister Albin Kurti did not yield any progress towards resolving current tensions.

Borell said after a series of meetings, which lasted over five hours, that “we did not get to an agreement today but it is not an end to the story”.

The meetings took place after tensions escalated two weeks ago when Kosovo Serbs protested against a Kosovo government decision to impose new entry and exit procedures for people with Serbian documents and the re-registration of cars with Serbian car plates.

Kosovo police on July 31 closed the country’s border crossings after local Serbs set up barricades. Under US advice, Pristina then decided to postpone the changes until September 1, causing the protests to subside.

Borrell expressed hope that a solution could be reached. “Both leaders agreed that the process needs to continue and the discussion will resume in the coming days,” he said.

“There is still time until the 1st of September, I don’t give up,” he added.

Vucic and Kurti last met at an informal dinner with the EU Special Representative for Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue, Miroslav Lajcak, on May 4 in Berlin.

The two leaders met twice during the summer of 2021 but neither the first nor second meeting produced any apparent progress.

On June 21, so-called “technical level” delegations from both countries agreed to a “road map” to further implement energy agreements made in 2013 and 2015.

However, after the recent protests, both Vucic and Kurti hardened their rhetoric.

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008, but Serbia does not recognise its sovereignty. Talks have been ongoing in Brussels for over a decade in an attempt to normalise relations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LA INCLUSION DE TEMAS DE INTERES DEL SUR GLOBAL EN AGENDA GLOBAL

“El tiempo pierde su poder cuando el recuerdo redime el pasado”,Herbert Marcuse

Después de haber analizado el carácter disruptivo global que producen los dos principales conflictos territoriales-culturales actuales (Ucrania y Medio Oriente) y la posible ruptura del frágil equilibrio entre los EEUU y China en Taiwán, considero desde las conclusiones de dicho escrito1, las posibilidades que se abren de un nuevo equilibrio internacional en que las aspiraciones y demandas del Sur Global sean incorporadas a la agenda internacional. En dicho análisis se concluye, en primer lugar, que ante las crecientes tensiones geopolíticas actuales y la fragmentación económica que producen tanto el desacople como el “de-risking” o la construcción de economías estratégicas nacionales o comunitarias, se va a una profundización de la marginalización e instrumentalización del llamado Sur Global, región mayoritaria del mundo que asume los mayores costos de estas luchas de poder.

En segundo lugar, se considera la disfunción paralizante mundial, a la que se llega por la aparición de bloques que compiten entre sí en una contexto de tensiones geopolíticas, que retraen los intercambios económicos internacionales que beneficiarían a los países emergentes, a la vez, que dañan la institucionalidad del sistema internacional a favor de acuerdos bilaterales o regionales. Dicha dinámica no favorece al más débil sino que exaspera las tensiones de los actores más poderosos en su competencia global. Es así como las potencias dominantes se comportan en realidad como las revisionistas2 que buscarían retrasar el desarrollo de potencias del Sur Global, a lo que el canciller de la Unión Europea, Josep Borell, se refirió como decadencia occidental3.

El cuantioso nuevo paquete de apoyo de los EEUU, aprobado por el Congreso y a la firma del Presidente Biden, después de meses de debate interno sobre esta cuestión, tensionará aún más la frágil paz internacional y dejará a los países del Sur Global ante paradojas irresueltas que finalmente inclinarán aún más su apoyo a las llamadas potencias “autoritarias”. El paquete de 90 mil millones de dólares tiene como prioridad Ucrania, pero incluye los otros dos actores en conflicto antes citados, Israel y Taiwán (el “Indo-Pacífico)4. Si bien en dicha legislación se incluye la confiscación de activos rusos por aproximadamente USD 5 mil millones USD, con las impredecible reacción rusa que se produciría, se ahondan las divisiones internas en el seno de la sociedad y dirigencia de los EEUU. El debate sobre el destino de dichos fondos cuando la agenda doméstica muestra tantas demandas insatisfechas permanece abierto y del mismo tipo al que se da en el contexto internacional.

En éste los índices de inequidad y polarización crecen desde la pandemia y aún antes, ya que los efectos de la globalización y de cierta difusión de los avances tecnológicos se fueron atenuando, consecuencia de crisis económicas globales, tensiones geopolíticas y mayor fragmentación cultural internacional. Además, gran parte de la disminución de las brechas existentes entre el Norte y Sur se deben al salto que dio China y posteriormente la India, que representan juntos dos tercios de la población mundial. El resto de los países del Sur Global prácticamente no han tenido variaciones internas y externas en dicho índice5.

Por ejemplo, en la pandemia el acceso a vacunas planteó serios cuestionamientos desde los países del Sur Global. Las crisis económicas iniciadas en falencias del sector financiero en el Norte Global también tuvieron serias reacciones negativas. El exacerbamiento de agendas de defensa y seguridad también han tenido efectos nefastos en los países del Sur Global, por la aparición de un nuevo tipo de proteccionismo y relocalización de factores productivos con criterios selectivos y políticos, a lo que se suma la histórica protección del norte de sectores competitivos del sur, como el agrícola. Flagelos como el crimen transnacional, narcotráfico y mafias principalmente, o desafíos internacionales como el cambio climático, migraciones y desplazamientos forzados, pobreza y enfermedades, tienen sus peores y más dolorosas manifestaciones en términos de costos y pérdidas materiales y humanas en el sur.

Sin ser exhaustiva la lista, se agrega la gran hipoteca para el futuro de estos países, como lo es la cuestión de la deuda externa, donde las inequidades antes mencionadas convergen y muestran lo injusto y precario del actual “orden internacional”. El último informe del FMI sobre la economía internacional alerta a los EEUU y a China para que tomen medidas para bajar sus futuros préstamos tomados en el mercado internacional, ya que el salto de sus deudas externas amenaza tener “profundos” efectos en la economía global6. Otros países que continúan en dicho listado son el Reino Unido e Italia. Los déficits fiscales están en el origen de tal cuestión, sea por medidas en la pandemia u otras vinculadas a objetivos políticos, económicos y militares. A su vez, dicho proceso atenta contra el objetivo de reducir la inflación, lo que a su vez, mantiene las tasas de interés altas, lo que afecta finalmente a otros gobiernos. En un contexto de numerosas elecciones que tienen lugar este año, todo contribuye para que esta situación empeore, perjudicando a las economías menos desarrolladas.

Se suma la tendencia antes mencionadas de un regreso a políticas proteccionistas, de carácter económico-estratégicas, anteriormente normales en regímenes como el chino, ahora expandidas entre los países desarrollados y hasta en los países del BRICS. En conclusión, más de 2500 políticas industriales han sido introducidas el año pasado, tres veces más que en 2019, lo que ya está produciendo un decrecimiento económico global, según también alerta el FMI7, por las distorsiones que se generan en las corrientes de comercio e inversión. Tanto los EEUU, la UE, como China figuran a la cabeza de tales medidas, pero países como Brasil8 se han ido sumando y producen graves perjuicios tanto al interior de sus países como a los países vecinos y a los de menor desarrollo relativo.

Tal es la situación en que estos procesos agravan la ya crónica vulnerabilidad de los países menos desarrollados que el FMI estaría revisando sus tradicionales políticas y condiciones para reestructuración de deudas y concesión de nuevos préstamos aún a países en situaciones de impago potencial o real9. La caída al vacío de países emergentes como Egipto, Pakistán o Indonseia podría producir tal efecto expansivo en otros en situaciones similares o en el sistema internacional, que la atención hacia cuestiones más de fondo lleva a que las paradojas del contexto global sean atendidas con mayor atención y seriedad por el conjunto de la comunidad internacional.

A raíz de la desatención de dichas paradoja,s gran parte de los países del mundo no se unen tan dócilmente al esfuerzo de EEUU y sus aliados en sus “cruzadas” democráticas contra las autocracias del mundo. Países como Brasil, India, Turquía o Sudáfrica, además de las potencias árabes de Medio Oriente, Arabia Saudita o los Emiratos Arabes, terminan por compartir esfuerzos y espacios como el BRICS, con potencias como Rusia o China y finalmente participar implícitamente en redes de alianzas con regímenes como el de Irán o Corea del Norte. Es lugar común decir que no hay factores cohesionadores entre estos países más que la oposición a los EEUU y sus aliados, expotencias colonialistas, y que sus fines últimos los dividen10. Sin embargo, la conjunción de intereses más o menos laxa de dichos países se alimenta de las numerosas paradojas antes mencionadas, que reflejan situaciones de inequidad, marginalización e instrumentalización de demandas y desafíos que por su carácter son nacionales, regionales y finalmente globales.

En tal sentido, el nuevo paquete de ayuda de los EEUU a los países aliados constituye un eslabón ineludible y grave en el escalamiento de conflictos potenciales y actuales en los tres frentes mencionados, no sólo porque acentúa la globalización y perpetuación de los tres conflictos, sino porque producirá una consolidación de la alianza Rusia-China-Irán, que incluye progresivamente a Corea del Norte. La alianza entre Rusia y China quedó establecida al inicio de operación militar espacial rusa en Ucrania, cuando el 22 de marzo de 2023 ambos países hicieron pública su agenda de entendimientos estratégicos. Esta se sintetiza en el compromiso conjunto de poner fin a la “hegemonía occidental” a través de una “amistad ilimitada”11. Los esfuerzos de los EEUU por doblegar tal alianza, hasta ahora visible principalmente en la no adhesión de China a las sanciones y cierto apoyo a la industria defensiva rusa, han sido infructuosos12.

Es más, dicha alianza se consolida ya que al mismo tiempo China percibe el cerco militar de contención que los EEUU y sus aliados han tendido en el Indo-Pacífico como una amenaza a sus intereses13. Rusia, a su vez, percibe la amenaza occidental como existencial y percibe el sistema de alianzas como un incentivo y necesidad para fortalecer sus propio sistema defensivo y hasta ofensivo, incluyendo acciones desestabilizadoras en Occidente14. En tal sentido, la alianza con Irán hace parte de tal cuestión, y se observa un accionar coordinado de Rusia y China en el mundo islámico, con base en el ingreso de Irán en la Organización de Cooperación de Shanghai, la estructuración de una red en Asia Central y el ingreso de éste en el BRICS15. Para mayor gravedad de este escenario, los ataques bélicos directos entre Israel e Irán marcan la regionalización y hasta globalización de la guerra en Gaza, lo que muestra como este conflicto se inserta en el contexto mayor16.

Volviendo al tema de los intereses del Sur Global y su aparente coincidencia con potencias como las que confluyen en el BRICS, se plantean dudas sobre tal hecho, toda vez que la agenda internacional es absorvida por la geopolítica y las demandas económicas sociales globales y del sur se ven nuevamente postergadas. Es decir, los esfuerzos llevados a cabo desde diversos frente para un diálogo que atienda las necesidades reales del Sur Global se ven contrarrestados por intereses propios de un contexto conflictivo altamente polarizado.

Sin embargo, se observa que la inacción de la ONU favorece el accionar de clubes de amigos, como el grupo BRICS, en donde países como India o Brasil no mantienen posiciones anti-occidentales, aunque no sean totalmente afines con Occidente. El hecho de que los países del BRICS “no hicieron las reglas, por lo que no habría que suscribir a las mismas o cumplirlas”, es una definición bastante cierta de su posicionamiento, al igual que de gran parte de los países del Sur Global17.

Además, iniciativas de los EEUU como, por ejemplo, la nueva “Asociación para la Cooperación Atlántica”, son vistas con desconfianza desde el Sur Global por su insufiencia para atender necesidades concretas y amplias para el desarrollo. En tal tipo de iniciativas escasa atención se ve en aspectos como inversiones en infraestructura y transporte o los temas de deuda externa, más allá del planteo de cuestiones estrechas como asociaciones marítimas, protección del medio ambiente o la pesca ilegal18.

En el contexto antes mencionado de tensiones geopolíticas, es notorio el rol que juegan las alianzas internacionales, donde las rivalidades explícitas entre las potencias antes mencionadas, llevan no sólo niveles crecientes de regionalización, sino también a que regiones enteras de Africa, Asia y América Latina pasen a ser marginalizadas y/o instrumentalizadas. Ello deja al descubierto el hecho de que la globalización ha sido siempre un fenómeno concentrado, con un conjunto de países y actores internacionales que son los que concentran el poder real y lo substancial de los movimientos e intercambios internacionales19.

Sin embargo, así como el BRICS se presenta como una reacción ante tal “hegemonía occidental”, con una progresiva mutación de su agenda hacia fines de seguridad y defensa, por el rol de liderazgo que ejercen Rusia y China, la voz del Sur Global ha ido filtrando temas propios de su agenda en foros como el G20. En este ámbito los EEUU y sus aliados sí proyectan temas de su política exterior20. También lo vienen haciendo países representativos del llamado Sur Global, puntualmente y de modo más reciente, Indonesia, la India y Brasil, durante sucesivas presidencias del G20. El siguiente turno será de Sudáfrica en 2025.

El rol de este foro donde conviven países actualmente confrontados con otros con un posicionamiento más neutral, pertenecientes al Sur Global principalmente, relanza las posibilidades del G20 como ámbito para solucionar problemas globales, como lo fue en la crisis financiera de 200821. Actualmente la posibilidad de brindar la paz al mundo vendría principalmente a partir del desempeño de dichos países neutrales y de sus posibilidades para tender puentes y generar canales de diálogo que desemboquen en acuerdos22.

Desde dicha necesidad mínima y básica de la paz, hay otros temas que desde las presidencia de los mencionados países se han ido lanzando e incorporando con más fuerza desde dicho marco institucional en la agenda internacional. Especialmente, en las últimas presidencias, India y Brasil, se enfatiza lo relacionado con la Seguridad alimentaria y erradicación del hambre; Clima y financiamiento para el desarrollo; Infraestructura pública digital; Instituciones financieras internacionales, principalmente bancos multilaterales para el desarrollo23.

Dicha agenda, junto con los temas de la paz, confirman la presunción inicial al iniciar este análisis en mi artículo anterior24, sobre la incorporación a la agenda internacional de temas relevantes para el Sur Global en la agenda internacional. La universalización de desafíos y riesgos que ha traído consigo el contexto de confrontación, si bien habría postergado otras demandas no directamente vinculadas a la seguridad y defensa, al mismo tiempo, ha generado, principalmente desde potencias emergentes en el mundo multipolar, nuevos canales para el diálogo multifacético. De progresar y cristalizar esta posibilidad en iniciativas concretas, a pesar de las fuerzas y dinámicas reaccionarias que se han descripto en este artículo, se habrá avanzado hacia un mayor consenso internacional en aquellos temas centrales para un desarrollo más equitativo, estable y armónico en la comunidad internacional.

RAPA -

31/03/2024.

Citas Bibliográficas:

1https://baluarteargentino.blogspot.com/2024/02/triunfo-del-multipolarismo-es-una-nueva.html

2Idem Nota 18.

3https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/munich-security-conference-four-tasks-eu%E2%80%99s-geopolitical-agenda_en

4https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/your-primer-on-the-us-house-security-bills-for-ukraine-israel-the-indo-pacific-and-more/

5https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/08/02/global-inequality-is-rising-again

6PAUL HANNON: “IMF Warns Surge in US, China Debt Could Have Profound Impact on Global Economy”. The Wall Street Journal. EEUU, 17/04/2024.

7PATRICIA COHEN: “The Global Turn Away From Free-Market Policies Worries Economists”. The New York Times. EEUU, 17/04/2024.

8https://www.ambito.com/economia/funcionario-clave-lula-revela-su-mega-plan-industrial-como-impactara-argentina-n5982614

9https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/04/18/can-the-imf-solve-the-poor-worlds-debt-crisis

10MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: “Occidente se fractura mientras sus rivales trabajan en equipo para poner fin a su hegemonía”. El Tiempo. Colombia. 10/03/2024.

11CARLOS PEREZ LLANA: “El conflicto Irán-Israel y el cambio de época en la política internacional”. Clarín. Argentina. 22/04/2024.

12“Russia and China Double Down on Deying US”. The Wall Street Journal. Estados Unidos. 09/04/2024.

13Item Nt. 12.

14CATHERINE BELTON: “Russian document targets the West”. The Washington Post. Estados Unidos. 18/04/2024.

15Idem Nt. 11.

16JOSCHKA FISCHER: “La guerra de Gaza se globaliza”. El Tiempo. Colombia. 21/04/2024.

17MATTHIAS VON HEIN: “Will BRICS expansion set a new agenda for the Global South?”. Deutsche Welle (DW). Alemania. 29/12/2023.

18ATLANTIC COUNCIL EXPERTS: “ Does the new Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation mark a sea changein transatlantic relations?”. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org

19https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/forjar-alianzas-en-un-mundo-fragmentado-y-geopolitico-estados-unidos-segun-el-indice-de-presencia-global-de-elcano/?_cldee=fsHeRo6YZva19qRJDa2258voJ7nqj0eEp3Hra-8Tg4oVUx-7kG6910ohJkKUtEqK&recipientid=contact-d2eef9cbd49de911a988000d3a233e06-740ef4eacc5241a1bc316967cd460fb8&esid=36add2c2-68d2-ee11-9079-000d3a4c1cd2

20Idem Nt. 19.

21FEDERICO PINEDO: “Un G20 para la paz?”. La Nación. Argentina. 11/03/2024.

22 MURILLO CAMAROTTO: “G20 no Brasil: Habilidade brasileira para criar consensos será testada”.O Globo. Brasil. 07/03/2024.

23MRUGANK BHUSARI, ANANYA KUMAR, PEPE ZHANG AND VALENTINE SADER: “What’s on Brazil G20 agenda? Start by looking at where India left off”. New Atlanticist. EEUU. 21/02/2024.

24Idem Nt. 1.

#geopolitica#sudamerica#economia#argentina#cultura#desarrollo#rusia#politica#estrategia#crisis#eeuu#europa

0 notes

Text

Wer ist Zivilist, wer Terrorist in Gaza?

Tichy:»Es ist keine sechs Monate her und beim Lesen der aktuellen internationalen Nachrichten drängt sich unweigerlich der Eindruck auf: Schuld an der katastrophalen Lage in Gaza trägt niemand anders als Israel. Der EU-Außenbeauftragte Josep Borell ist bei dieser anti-jüdischen und anti-israelischen Kampagne ganz vorne dabei: „„Es ist kein Erdbeben, es ist keine Flut. Es ist

Der Beitrag Wer ist Zivilist, wer Terrorist in Gaza? erschien zuerst auf Tichys Einblick. http://dlvr.it/T4p7Rb «

0 notes

Text

Deputy Chairman of the Russian State Duma, Alexander Babakov’s comments on the US neocolonial posture in International relations following the despicable and haughty word uttered by the senile and sleepy Biden labelling dictator, his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, have the merit of naming the things by their name contrary to the very diplomatic words by Chinese ministry of foreign affairs, simply calling Biden’s word of dictator “wrong and irresponsible” The word of dictator is not only openly contemptuous of Chinse leader, it is also clear insult of 1,4 billion of Chinese, of their state, of their political, economic and cultural institutions and chiefly of their thousands years of history. The qualifiers, dictator, dictatorship, terrorism, authoritarian regimes, are integral part of the language of Empire used by hegemonic power, the United States and its European vassals, to denigrate men, political and economic systems, institutions, axis of evil history and culture of nations and peoples refusing to kneeling and to obey to diktats and orders emanating from master to its slaves. In addition, the qualifiers such liberal democracy, freedom, liberty, the garden versus the jungle of Josep Borell, axis of good are integral part of the language of Empire.

0 notes

Text

Șeful diplomației europene nici nu vrea să audă de planul de pace al Chinei: ”Există un singur plan de pace: planul Zelenski” VIDEO

Josep Borell a făcut o declarație prin care spulberă orice speranță că Uniunea Europeană ar vrea ca în Ucraina să se instaureze pacea.

Georgiana Arsene

Josep Borrell, șeful diplomației europene, a vorbit despre cum a devenit “ministrul apărării al UE”:

Mă simt ca un ministru al apărării al UE. Pentru că îmi petrec cea mai mare parte a timpului vorbind despre arme și muniții. Nu m-am gândit…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Foreign policy chief: EU prepares long-term security commitments for Ukraine

The bloc’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said on Monday that EU foreign ministers at a special meeting in Kyiv confirmed their intentions to continue supporting Ukraine.

A delegation of European Union foreign ministers made an unexpected visit to Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, on Monday, aiming to demonstrate unity and reiterate the EU’s support for Ukraine. The visit comes amidst doubts and divisions emerging in both the United States and Europe regarding their long-term commitment to assisting Ukraine.

Borell said that the EU would be able to provide Ukraine with “long-term security guarantees” after the end of hostilities on Ukrainian territory. He has made a proposal to the EU to provide Ukraine with another €5bn ($5.25bn) military aid. He expects EU countries to agree to this support by the end of 2023.

Learn more HERE

#world news#world politics#news#eu news#european news#eu politics#europa#europe#ukraine war#ukraine news#ukraine#josep borrell

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

L'Union européenne cherche à recalibrer sa stratégie vis-à-vis de la Chine

La mise à jour de la stratégie de l’Union européenne (UE)E vis-à-vis de la Chine était nécessaire, notamment en raison de la montée du «nationalisme et de l’idéologie» sous le dirigeant chinois Xi Jinping, de la rivalité accrue entre les États-Unis et la Chine, et de l’intensification du rôle de Pékin dans les «questions régionales et mondiales», précise le document, lu par Euractiv.

Pour réduire les risques lorsqu’elle traite avec la Chine, l’UE doit se montrer plus «lucide» et se concentrer sur les valeurs et la sécurité économique et stratégique, selon le document interne préparé par le chef de la diplomatie de l’UE, Josep Borrel.

Ce document officieux, préparé par le Haut responsable de l’Union pour les Affaires étrangères et la Politique de sécurité Josep Borrell et le Service européen pour l’action extérieure (SEAE), a été envoyé aux États membres avant une réunion des ministres des Affaires étrangères qui s'est tenu le 12 mai à Stockholm. Cette réunion des ministres s'est concentrée sur l’approche à adopter vis-à-vis de la Chine.

Lire aussi : Face à la Chine, l'Union européenne cherche une union

Le document, intitulé «Remodeler nos relations avec la Chine, s’engager avec la Chine, rivaliser avec la Chine», a exprimé un soutien clair à la nouvelle stratégie d’«atténuation des risques» de l’UE, préconisée par de hauts fonctionnaires du bloc au cours des derniers mois, au lieu d’un «découplage» des relations.

Aller vers un changement de stratégie : une politique plus dure

Les États membres de l’UE sont aussi invités à réduire le risque d’une influence croissante de la Chine dans les domaines de l’économie et de la sécurité. D'autant que la Chine devrait être l’un des principaux sujets abordés lors du Sommet européen qui se tiendra à Bruxelles à la fin du mois de juin.

Les États-Unis ont adopté une approche plus ferme à l’égard de la Chine, les dirigeants européens veulent en faire de même, mais ils leur faut pour cela une approche unifiée. Raison pour laquelle, l'UE a décidé de consacrer les prochaines semaines à la question de la Chine.

L’UE doit adopter une approche «lucide» mais «non conflictuelle» face à une Chine qui cherche à «construire un nouvel ordre mondial», a indiqué le document de l’UE, envoyé aux capitales des Vingt-Sept, le 11 mai.

Ces derniers mois, certains États membres ont appelé à une refonte de la stratégie de l’UE de 2019 à l’égard de la Chine, tandis que d’autres restent prudents et mettent en garde contre une révision complète de cette stratégie.

Cette volonté de changement stratégique fait suite à une première discussion qui s’est tenue à la fin de l’année 2022 et au cours de laquelle le service diplomatique de l’UE, mené par Joseph Borell, a préconisé pour la première fois une position plus dure à l’égard de la Chine.

Le document du chef de la diplomatie européenne a réaffirmé la stratégie de l’UE : traiter la Chine à la fois comme un partenaire, un concurrent et un rival systémique, mais il souligne que l’équilibre de ces approches dépendra de la manière dont la Chine réagira aux actions de l’UE.

Dans une lettre en annexe envoyée aux ministres des Affaires étrangères de l’Union européenne, Joseph Borrell a fixé trois nouveaux axes qui définiront les futures relations entre l'UE et la Chine : les valeurs, la sécurité économique et la sécurité stratégique, en mettant l’accent sur l’Ukraine et Taïwan.

Les États membres sont invités à s’en tenir à cette désignation, «même si la pondération entre ces différents éléments peut varier en fonction du comportement de la Chine». «Il est évident que ces dernières années, l’aspect de la rivalité est devenu plus important», a noté le Haut représentant, dans son document.

L'UE dénonce une montée du "nationalisme et de l'idéologie" de Xi Jinping

La mise à jour de la stratégie de l’UE vis-à-vis de la Chine était nécessaire, notamment en raison de la montée du «nationalisme et de l’idéologie» sous le dirigeant chinois Xi Jinping, de la rivalité accrue entre les États-Unis et la Chine, et de l’intensification du rôle de Pékin dans les «questions régionales et mondiales», précise le document.

«La Chine et l’Europe ne peuvent pas devenir plus étrangères l’une à l’autre Sinon, les malentendus risquent de se développer et de s’étendre à d’autres domaines», a écrit Joseph Borell dans son document confidentiel, lu par Euractiv.

Ainsi, «la rivalité systémique peut se manifester dans presque tous les domaines d’engagement. Mais cela ne doit pas empêcher l’UE de maintenir des canaux de communication ouverts et de rechercher une coopération constructive avec la Chine.»

En effet, au lieu de rompre tout lien avec la Chine, le service diplomatique de l’Union européenne invite les États membres à maintenir le dialogue et les relations avec Pékin. «Des messages ouverts et clairs à l’intention des dirigeants chinois, associés à des attentes réalistes, sont nécessaires pour garantir la crédibilité et l’influence», peut-on lire dans le document.

«Si nous voulons construire une nouvelle stabilité dans nos relations complexes, l’UE et ses États membres doivent rester fermes, sans confrontation», a ajouté le document. A l'instar de l'administration Biden attestant qu'il est possible de travailler avec la Chine sur certains sujets, dont le climat, l'UE veut également une coopération recherchée dans la mesure du possible, ce qui peut «briser l’isolement croissant que s’infligent les dirigeants chinois, mais surtout faire avancer les intérêts fondamentaux de l’UE».

La Chine s'inquiète des déclarations de l'UE sur la "réduction des risques"

Lorsque l'on parle de "réduction des risques, il est d'abord nécessaire d'identifier ces risques et de comprendre d'où ils viennent", a affirmé Qin Gang, conseiller d'Etat et ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Chine.

"La Chine n'exporte pas son système politique, s'en tient à une voie de développement pacifique, poursuit une stratégie d'ouverture offrant des résultats gagnant-gagnant et mutuellement profitables, respecte et maintient l'ordre mondial fondé sur les lois internationales, et s'oppose aux politiques d'hégémonie, de domination et d'intimidation", a souligné le diplomate chinois.

"La Chine est prête à s'associer à d'autres pays pour relever ensemble les défis et construire une communauté de destin pour l'humanité", a déclaré Qin Gang. D'autant que "la Chine exporte des opportunités plutôt que des crises, de la coopération plutôt que de la confrontation, de la stabilité plutôt que des troubles, de la sécurité plutôt que des risques", a-t-il ajouté.

"La Chine et l'UE sont deux grands marchés qui grandissent ensemble. Ce sont des partenaires pour une coopération gagnant-gagnant", a déclaré le ministre chinois. "Nous apprécions le fait que l'Allemagne et l'UE aient annoncé qu'elles ne chercheraient pas à se dissocier de la Chine, mais nous sommes toujours préoccupés par les déclarations de l'UE concernant la réduction des risques", a indiqué Qin Gang.

Toutefois, "si certains (pays ou parties) persistent dans la désinisation au nom de la réduction des risques, ils rompront en fait avec les opportunités, la coopération, la stabilité et le développement", a-t-il avertit.

Le ministre chinois a mis en garde contre le fait que certains pays sont en train de lancer une "nouvelle guerre froide". "Ils ont enfreint les règles internationales, attisé la confrontation idéologique et la confrontation de blocs, tenté de se dissocier des autres et de rompre les chaînes d'approvisionnement, abusant du pouvoir monopolistique de leur monnaie pour imposer une "juridiction au bras long" et des sanctions unilatérales à d'autres pays. En outre, ils ont exporté leur propre inflation, leur propre crise financière et créé de graves retombées", a indiqué le diplomate chinois.

"Ce sont des risques réels auxquels il faut prêter attention", a déclaré Qin Gang, avertissant que si la "nouvelle guerre froide" était déclenchée, elle serait non seulement néfaste pour les intérêts de la Chine, mais aussi pour ceux de l'UE.

"Nous devons nous opposer fermement au 'découplage avec les autres et à la rupture des chaînes d'approvisionnement', rester vigilants face à la 'nouvelle guerre froide' et nous unir pour garantir des chaînes industrielles et d'approvisionnement internationales stables et fonctionnant correctement", a-t-il conclu.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

The EU has delivered 500,000 of the promised 1 million artillery shells to Ukraine and aims to deliver the total amount by the end of the year, the EU's top diplomat, Josep Borrell, said in his blog on March 25.

The EU announced in March 2023 that it would provide Ukraine with a million shells within one year. News first emerged in October 2023 that the bloc was unlikely to reach its target, having been unable to ramp up production.

On top of the million donated shells, another 400,000 shells will be provided to Ukraine through commercial contracts with the European defense industry, Borrell said.

"The Czech initiative to buy ammunition outside the EU comes in addition to these efforts," Borrell said, referring to the 800,000 shells in stocks in countries around the world that Prague identified in February as potential supplies for Ukraine.

Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala said on March 12 that the initiative has already secured the purchase of 300,000 shells and received nonbinding commitments for 200,000 more. More than 20 countries have pledged funding for the initiative.

According to Borell, however, the planned shell supplies are "far from being enough," and argued that the EU has to "increase both our capacity of production and the financial resources devoted to support Ukraine."

Borrell also pointed out that the 290 billion euro ($314 billion) EU defense budget for 2023 only represents 1.7% of EU GDP, which is below the NATO 2% benchmark.

"In the current geopolitical context, this could be seen as a minimum requirement," Borrell said.

0 notes