#Jordan 1946 Independence from the British Government

Text

Jordan Independence Day Amman

Jordanian Flag Independence Day – Edarabia

May 25 is Jordan Independence Day, and the “most important event in the history of the country, marking its independence from the British government in 1946”. The 2023 celebration signifies 75 years since Jordan “officially gained full autonomy in 1948“.

King Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein

“Jordan’s independence took place during the reign of King Abdullah I…

View On WordPress

#Al Shareef Hussein Bin Ali – Emir of Mecca - King of the Hijaz - King of the Arabs#Arab League#Arab Revolt Against the Ottoman Empire#Autonomous Constitutional Monarchy#Council of the League of Nations#Emirate of Transjordan#Great Arab Revolt#Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt#Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan#Hashemites#His Majesty King Abdullah I Emir of Transjordan 1921-1946#His Majesty King Abdullah II – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1999 to Present#His Majesty King Al Hussein – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1952-1999#His Majesty King Talal – King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1951-1952#House of Hashem#Jordan 1946 Independence from the British Government#Jordan Houses – Senate - House of Representatives#Jordan Independence Day May 25#Jordan WWI Allies Britain and France#Jordanian Armed Forces#Khamaseen Winds#King Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein#King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1946-1951#Ottoman Empire#Presentation of Colours Ceremony#Sharif Hussein of Mecca#The Emir#Transjordan#Transjordan Memorandum#United Nations

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The parliament of Transjordan made Abdullah I of Jordan their Emir on May 25, 1946.

Jordan’s Independence Day

Jordan’s Independence Day is celebrated on May 25 every year, and is the most important event in the history of Jordan, as it commemorates its independence from the British government. After World War I, the Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt took over the area which is now Jordan. The Hashemites launched the revolt, led by Sharif Hussein, against the Ottoman Empire. The Allied forces, comprising Britain and France supported the Great Arab Revolt. Emir Abdullāh was the one who negotiated Jordan’s independence from the British. Though a treaty was signed on March 22, 1946, it was two years later when Jordan became fully independent. In March 1948, Jordan signed a new treaty in which all restrictions on sovereignty were removed to guarantee Jordan’s independence. Jordan joined and became a full member of the United Nations and the Arab League in December 1955.

History of Jordan Independence Day

The first appearance of fortified towns and urban centers in the land now known as Jordan was early in the Bronze Age (3600 to 1200 B.C.). Wadi Feynan then became a regional center for copper extraction with copper at the time, being largely exploited to facilitate the production of bronze. Trading, migration, and settlement of people in the Middle East peaked, thereby advancing and refining more and more civilizations. With time, villages in Transjordan began to expand rapidly in areas where water resources and agricultural land abound. Ancient Egyptians then later expanded towards the Levant and would eventually control both banks of the Jordan River.

There was a period of about 400 years during which Jordan was under the rule and influence of the Ottoman Empire, and the period was characterized by stagnation and retrogression to the detriment of the Jordanian people. The reign of the Ottoman Empire over Jordan would eventually cease when Sharif Hussein led the Hashemite Army in the Great Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, with the Allies of World War I supporting them. In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the terms of the Transjordan memorandum. Transjordan remained under British mandate until 1946, when a treaty was signed, with eventual sovereignty being granted upon signing a subsequent treaty in 1948.

The Hashemites’ assumption of power in the Jordan region came with numerous challenges. In 1921 and 1923, there were some rebellions in Kura which were suppressed by the Emir’s forces, with British support. Jordan is generally a peaceful region today, and it has become quite a tourist destination in recent times.

Jordan Independence Day timeline

3600 B.C. Earliest Known Jordanian Civilizations

Fortified towns and urban centers begin to spring up in the area now known as Jordan.

1922 Jordan is Recognized as a State

In 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognizes Jordan as a state under the Transjordan memorandum.

1946 First Independence Treaty is Signed

In 1946, Emir Abdullāh negotiates the first independence treaty with Britain which would later lead to Jordan's ultimate independence in 1948.

1955 Jordan Joins the United Nations

Jordan becomes a member of the United Nations and the Arab League in 1955.

Jordan Independence Day FAQs

What day is Jordan’s Independence Day?

Jordan’s Independence Day is May 25, every year. It marks the anniversary of the treaty that gave Jordan her sovereignty.

When did Jordan become independent?

On May 25, 1948, Jordan officially became an independent state.

Who is Jordan’s current leader?

The current ruler Of Jordan is the monarch, Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein, King of Jordan.

How to Observe Jordan Independence Day

Light up some fireworks

Prepare some mansaf

Share on social media

One of the hallmark celebrations of any independence day is the show of fireworks. Be sure to be a part of the beauty!

As you probably already knew, Mansaf is Jordan’s national dish. As such, preparing it on such a special day as Independence Day is a brilliant idea.

Take pictures and videos of you in your dishdasha celebrating Independence Day. Share them on your social media!

5 Interesting Facts About Jordan

Home to the Dead Sea

A nexus between Africa, Europe, and Asia

Over 100,000 archeological sites

The world’s oldest dam

Jesus was baptized in Jordan

The Dead Sea, which is the lowest point on Earth, is located in Jordan.

Jordan is a pivotal point connecting Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Jordan has over 100,000 archeological and tourist sites.

Jordan is home to the world’s oldest dam, the Jawa Dam.

Jesus, who is the symbolic character of the Christian faith, was baptized in the Jordan River before beginning his ministry.

Why Jordan Independence Day is Important

Jordan is peaceful and liberal

The weather in Jordan is nice

Jordan is a tourist’s dream

Though a generally conservative country, Jordan is relatively liberal. The country is peaceful and tolerant of foreign cultures.

Jordan is a warm region. The weather is usually warm and pleasant at all times of the year.

Jordan has everything a tourist could dream of. Beautiful sights, calm weather, a welcoming culture, and amazing people make it a fantastic place for tourists.

Source

#Petra#Amman#Aqaba Fortress#Aqaba#Jerash#ruins#architecture#travel#archaeology#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#summer 2007#Jordan#Asia#Middle East#Gadara#Dead Sea#Wadi Mujib#Wadi Rum#desert#Kerak Castle#Abdullah I of Jordan#Emir#25 May 1946#anniversary#Jordan history#vacation#Jordan’s Independence Day

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 5.25

567 BC – Servius Tullius, the king of Rome, celebrates a triumph for his victory over the Etruscans.

240 BC – First recorded perihelion passage of Halley's Comet.

1085 – Alfonso VI of Castile takes Toledo, Spain, back from the Moors.

1420 – Henry the Navigator is appointed governor of the Order of Christ.

1521 – The Diet of Worms ends when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, issues the Edict of Worms, declaring Martin Luther an outlaw.

1644 – Ming general Wu Sangui forms an alliance with the invading Manchus and opens the gates of the Great Wall of China at Shanhaiguan pass, letting the Manchus through towards the capital Beijing.

1659 – Richard Cromwell resigns as Lord Protector of England following the restoration of the Long Parliament, beginning a second brief period of the republican government called the Commonwealth of England.

1660 – Charles II lands at Dover at the invitation of the Convention Parliament, which marks the end of the Cromwell-proclaimed Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and begins the Restoration of the British monarchy.

1738 – A treaty between Pennsylvania and Maryland ends the Conojocular War with settlement of a boundary dispute and exchange of prisoners.

1787 – After a delay of 11 days, the United States Constitutional Convention formally convenes in Philadelphia after a quorum of seven states is secured.

1798 – United Irishmen Rebellion: Battle of Carlow begins; executions of suspected rebels at Carnew and at Dunlavin Green take place.

1809 – Chuquisaca Revolution: Patriot revolt in Chuquisaca (modern-day Sucre) against the Spanish Empire, sparking the Latin American wars of independence.

1810 – May Revolution: Citizens of Buenos Aires expel Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros during the "May Week", starting the Argentine War of Independence.

1819 – The Argentine Constitution of 1819 is promulgated.

1833 – The Chilean Constitution of 1833 is promulgated.

1865 – In Mobile, Alabama, around 300 people are killed when an ordnance depot explodes.

1878 – Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera H.M.S. Pinafore opens at the Opera Comique in London.

1895 – Playwright, poet and novelist Oscar Wilde is convicted of "committing acts of gross indecency with other male persons" and sentenced to serve two years in prison.

1895 – The Republic of Formosa is formed, with Tang Jingsong as its president.

1914 – The House of Commons of the United Kingdom passes the Home Rule Bill for devolution in Ireland.

1925 – Scopes Trial: John T. Scopes is indicted for teaching human evolution in Tennessee.

1926 – Sholom Schwartzbard assassinates Symon Petliura, the head of the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, which is in government-in-exile in Paris.

1933 – The Walt Disney Company cartoon Three Little Pigs premieres at Radio City Music Hall, featuring the hit song "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?"

1935 – Jesse Owens of Ohio State University breaks three world records and ties a fourth at the Big Ten Conference Track and Field Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

1938 – Spanish Civil War: The bombing of Alicante kills 313 people.

1940 – World War II: The German 2nd Panzer Division captures the port of Boulogne-sur-Mer; the surrender of the last French and British troops marks the end of the Battle of Boulogne.

1946 – The parliament of Transjordan makes Abdullah I of Jordan their Emir.

1953 – Nuclear weapons testing: At the Nevada Test Site, the United States conducts its first and only nuclear artillery test.

1953 – The first public television station in the United States officially begins broadcasting as KUHT from the campus of the University of Houston.

1955 – In the United States, a night-time F5 tornado strikes the small city of Udall, Kansas as part of a larger outbreak across the Great Plains, killing 80 and injuring 273. It is the deadliest tornado to ever occur in the state and the 23rd deadliest in the U.S.

1955 – First ascent of Mount Kangchenjunga: On the British Kangchenjunga expedition led by Charles Evans, Joe Brown and George Band reach the summit of the third-highest mountain in the world (8,586 meters); Norman Hardie and Tony Streather join them the following day.

1961 – Apollo program: U.S. President John F. Kennedy announces, before a special joint session of the U.S. Congress, his goal to initiate a project to put a "man on the Moon" before the end of the decade.

1963 – The Organisation of African Unity is established in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

1966 – Explorer program: Explorer 32 launches.

1968 – The Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri, is dedicated.

1973 – In protest against the dictatorship in Greece, the captain and crew on Greek naval destroyer Velos mutiny and refuse to return to Greece, instead anchoring at Fiumicino, Italy.

1977 – Star Wars (retroactively titled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope) is released in theaters.

1977 – The Chinese government removes a decade-old ban on William Shakespeare's work, effectively ending the Cultural Revolution started in 1966.

1978 – The first of a series of bombings orchestrated by the Unabomber detonates at Northwestern University resulting in minor injuries.

1979 – John Spenkelink, a convicted murderer, is executed in Florida; he is the first person to be executed in the state after the reintroduction of capital punishment in 1976.

1979 – American Airlines Flight 191: A McDonnell Douglas DC-10 crashes during takeoff at O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, killing all 271 on board and two people on the ground.

1981 – In Riyadh, the Gulf Cooperation Council is created between Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

1982 – Falklands War: HMS Coventry is sunk by Argentine Air Force A-4 Skyhawks.

1985 – Bangladesh is hit by a tropical cyclone and storm surge, which kills approximately 10,000 people.

1986 – The Hands Across America event takes place.

1997 – A military coup in Sierra Leone replaces President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah with Major Johnny Paul Koroma.

1999 – The United States House of Representatives releases the Cox Report which details China's nuclear espionage against the U.S. over the prior two decades.

2000 – Liberation Day of Lebanon: Israel withdraws its army from Lebanese territory (with the exception of the disputed Shebaa farms zone) 18 years after the invasion of 1982.

2001 – Erik Weihenmayer becomes the first blind person to reach the summit of Mount Everest, in the Himalayas, with Dr. Sherman Bull.

2002 – China Airlines Flight 611 disintegrates in mid-air and crashes into the Taiwan Strait, with the loss of all 225 people on board.

2008 – NASA's Phoenix lander touches down in the Green Valley region of Mars to search for environments suitable for water and microbial life.

2009 – North Korea allegedly tests its second nuclear device, after which Pyongyang also conducts several missile tests, building tensions in the international community.

2011 – Oprah Winfrey airs her last show, ending her 25-year run of The Oprah Winfrey Show.

2012 – The SpaceX Dragon 1 becomes the first commercial spacecraft to successfully rendezvous and berth with the International Space Station.

2013 – Suspected Maoist rebels kill at least 28 people and injure 32 others in an attack on a convoy of Indian National Congress politicians in Chhattisgarh, India.

2013 – A gas cylinder explodes on a school bus in the Pakistani city of Gujrat, killing at least 18 people.

2018 – The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) becomes enforceable in the European Union.

2018 – Ireland votes to repeal the Eighth Amendment of their constitution that prohibits abortion in all but a few cases, choosing to replace it with the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland.

0 notes

Photo

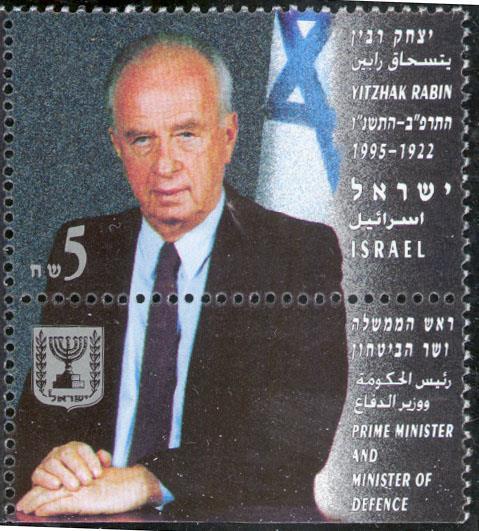

24 years since the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin was born in Jerusalem in 1922 to pioneers from the Third Aliyah. As a youth he began to pursue a career in agronomy, but was persuaded by his friend Yigal Allon to forsake his studies and join the newly established Palmach.

Shortly after, the 19-year-old sabra found himself at the head of the allied invasion of Lebanon under the command of Moshe Dayan. Yitzhak’s military prowess propelled him to the top of the Palmach command, where he stood out as one of the organization’s most distinguished members.

In 1946 Yitzhak was arrested along with many other prominent Zionist leaders by the British during Operation Agatha and imprisoned for five months. In October 1947, he was appointed the Palmach’s Chief Operations Officer and went on to serve in many other critical roles throughout Israel’s War of Independence.

Rabin’s military success culminated in his 1964 appointment as Chief of Staff, a position he held until 1968. During his tenure, the IDF achieved the miraculous victory of the Six Day War and established itself as the most dominant fighting force in the region. After retiring from the military, Rabin served as Israel’s ambassador to the US, during which the US became Israel's main weapons supplier.

In 1973 Yitzhak entered politics and was appointed minister of labor in Golda Meir’s government; however, Golda resigned shortly after due to the public outcry following the Yom Kippur War. The Labor Party elected Rabin as its head and he was sworn in as Prime Minister, a position he held until 1977.

After the 1984 elections that resulted in a national unity government, Rabin was appointed minister of defense and oversaw IDF military operations during the First Intifada. Rabin was elected Prime Minister for the second time in 1992 and signed the famous Oslo Accords with the PLO the following year (for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize). In 1994 he signed a peace treaty with Jordan.

On November 4, 1995, Yitzhak was assassinated by Yigal Amir, an extremist who opposed the Oslo Accords. In Israel, Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Day is commemorated on the Hebrew date of his assassination, the 12 of Cheshvan.

My Nation Lives עמי-חי

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

West Bank Story

Is diplomacy merely the costume politics wears when it ventures out into the international arena? Or are diplomacy and politics entirely different fields of endeavor, the one “about” the translation of national principles into the stuff of international relationships and the other “about” the need at least on occasion to surrender those very same principles for the sake of attaining the power necessary broadly to implement them in the forum of national affairs? It’s not that easy to say!

These were the thoughts that came to me this last week when I read that the United States government has determined that there is no inherent illegality to the establishment of Jewish settlements on the land Israel took over from Jordan after the Six Day War in 1967. Of course, illegal and ill-advised are not the same thing—and it is more than possible for something to be technically legal but still a bad idea actually to implement. (It is, for example, fully legal in New York State to purchase cigarettes and to smoke them wherever smoking is permitted.) And, that being the case, asking whether Israel should continue to construct settlements on the West Bank or whether the path toward peace will be made smoother or more rocky by this specific policy shift on the part of the U.S. government—those questions remain on the table for discussion and no doubt prolonged, rancorous debate. And rancor—to say the very least—is surely what will presently ensue now that this week’s decision is in place.

The United Nations has expressed itself repeatedly to the effect that allowing Israeli civilians to live on territory Israel acquired in the Six Day War is a contravention of the Fourth Geneva Convention, an international agreement to which both Israel and Jordan have been party since 1951. Leaving aside the moral bankruptcy of the United Nations and its decades-long history of unremitting and shamefully prejudicial hostility towards Israel, the issue here turns on the fact that the Convention in question specifically prohibits states signed on from moving civilians onto land seized by war, as might be done by a nation eager to establish an ongoing claim to the seized territory in question. But nothing in the Middle East is ever all that simple to unravel. (Also, it’s a good thing the U.S. only signed the convention in 1955—wasn’t Texas acquired by our nation in the Mexican War of 1848? Just sayin’.)

The territory in question on the west bank of the Jordan River was indeed part of sovereign Jordan before 1967. But Jordan only came to control the territory after the Israeli War of Independence in 1948 and its occupation of the territory was itself never recognized by a vast majority of the world’s nations. Furthermore, the land in question was specifically acknowledged as the heartland of the Land of Israel—the ancient homeland of the Jewish people—by the League of Nations in 1922. Most Americans will find it challenging to say whether any real importance should be ascribed to the decision of an organization that existed for a mere twenty-six years and which has been defunct since 1946. But for Jewish Americans, who come pre-equipped with much, much longer memories than their average co-citizens, the issue is rooted in a far older times than the Roaring Twenties anyway.

That the land on the west bank of the Jordan—called by many today by their biblical names, Judah and Samaria—that that land was part of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in antiquity is debated today by no reputable historian or political analyst at all. Nor, as I wrote in this space a few weeks ago, is at all in dispute the fact that the history of the land that followed the collapse of the Maccabean kingdom in the year 67 BCE was one of endless occupation—first by the Romans, but then by Iran (then called Persia), and then in order by the Byzantine Empire, the Muslim Caliphate, the Crusader Kingdoms, the Mameluke Sultanate, the Ottoman Empire and, finally, the British Empire (acting behind the fig leaf of its League of Nations mandate to rule over what had previously—and at that point for almost five centuries—been Turkish Palestine). That’s a lot of occupiers—thousands of years’ worth—and not a single one held back from settling civilians on territory gained by war. Nor, for that matter, did even a single one of the above— including any of the Muslim occupiers mentioned above—consider the land currently referenced as “the” West Bank distinct or different from the rest of the historic Jewish homeland. When Americans talk about “the” West Bank, therefore, as though it were akin to a state in the Union or a department of the French Republic, they are therefore setting themselves up not at all to understand the issue as it feels on the ground to the average Israeli. Or, for that matter, to the average citizen of any country possessed of a clear sense of the history of the territory in question.

All that being the case, the notion that the Fourth Geneva Convention can be simply be applied to the territory in question as though we were talking about the German occupation of Namibia—a place in Africa with no historical tie of any sort whatsoever to Germany—seems, to say the very least, facile.

And also worth noting—and stressing—is the degree to which I constantly see people with little or no background in the actual history of the region speaking or writing negatively about Israel’s presence on the West Bank at all. The Balfour Declaration of 1917, for example, was an expression both of acceptance of the indigeneity of the Jewish people in the Land of Israel and also of their natural right to establish a Jewish nation in their historic homeland. That, of course, was nothing more than an expression of British policy with respect to the eventual future of what was soon to become—at least slightly ironically—British Palestine. But dramatically less well known is that the San Remo Conference of 1920 that divvied up the territories of the nations defeated in the First World War among the victors formally affirmed the basic principles of the Balfour Declaration, speaking overtly “in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national homeland for the Jewish people.” There is not the slightest evidence of any sort that the participants at San Remo meant to exclude the land currently referenced as the West Bank in that thought.

I can’t recall hearing much about the San Remo conference lately, but even less about the Treaty of Sèvres that resulted from San Remo and which, as one of the final agreements that ended World War I, yet again reaffirmed the Balfour Declaration’s intent, and firmly, in these words: “The Mandatory shall be responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.” It was these words that the League of Nations affirmed and confirmed in 1922 when it adopted them into the formal mandate declaration awarded Turkish Palestine to the British.

All that being the case, to refer to the West Bank as being “occupied” by Israel because they wrested it from a nation that itself only ended up as its overlords because they managed to seize it militarily after the British withdrew their forces in 1948 and then had their overlordship of the region affirmed by the Armistice Agreement that ended the Israeli War of Independence seems, again to say the very least, forced.

Another point I generally hear made by none in this fraught context is that the United Nations Charter itself affirms the validity of all treaties entered into or brokered by its predecessor organization, the League of Nations. As a result, when the United Nations passed a scurrilous resolution in 2016 decrying all Jewish settlements on the West Bank as one large violation of international law, it was not only ignoring the specific details of the Oslo Accord of 1995 (which, pending a final peace treaty between Israelis and Palestinians, divided the West Bank up into three areas, innocuously labelled A, B, and C, and specifically awarded Israel the right to govern the Arabs and the Jews resident in Area C), but also its own historical obligations. That our government dishonorably allowed that resolution to pass without a veto was a betrayal not only of Israel, but of our own supposed devotion to the rule of law.

People talk about “the settlements” as an untraversable barrier preventing Israel and the Palestinians from moving forward towards a peaceful resolution of their dispute. But even that commonplace assertion only really works on the assumption that the presence of a relatively small Jewish minority in a Palestinian state is impossible to imagine. On the other hand, if Israel is able to pursue its national destiny as a Jewish state with 20% Arab minority, why shouldn’t Palestine also be able to move forward with a Jewish minority of about 380,000 people among its three million citizens? And that number is not even remotely correct because the chances of every single Jewish resident of the West Bank remaining in place after a declaration of Palestinian independence is zero, which would bring the percentage of Jews present in independent Palestine to less than 10%. To describe that as an intractable problem only really makes sense if it goes without saying that a future independent Palestine must be wholly judenrein, an opinion I find both odious and deeply offensive.

Our government acted in a principled and proper way to reject the notion that the presence of Jewish towns and villages on the West Bank is an ipso facto example of illegal settlement under the Fourth Geneva Convention. In a week already filled with cringe-worthy moments by the dozen, the Secretary of State’s announcement of this shift in American policy (which was really just a return to the policy adopted by the Reagan administration) was both welcome and just.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

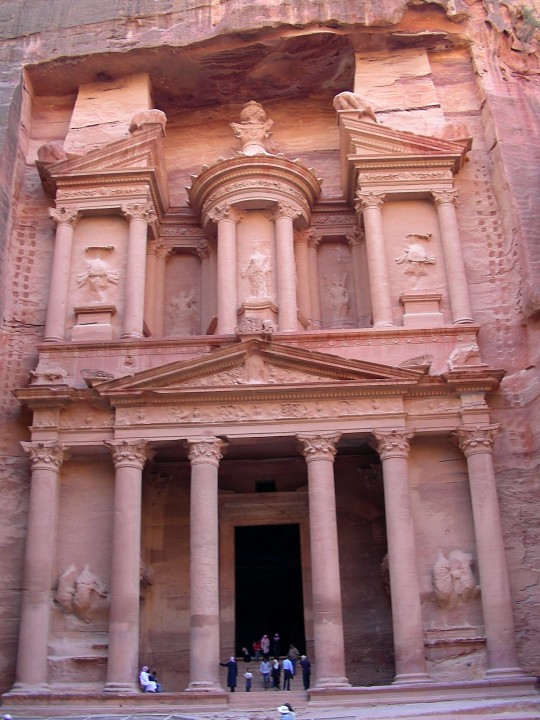

Jordan, Arab country of Southwest Asia, in the rocky desert of the northern Arabian Peninsula. It is a young state that occupies an ancient land, one that bears the traces of many civilizations. Separated from ancient Palestine by the Jordan River, the region played a prominent role in biblical history. The ancient biblical kingdoms of Moab, Gilead, and Edom lie within its borders, as does the famed red stone city of Petra, the capital of the Nabatean kingdom and of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea. British traveler Gertrude Bell said of Petra, “It is like a fairy tale city, all pink and wonderful.” Part of the Ottoman Empire until 1918 and later a mandate of the United Kingdom, Jordan has been an independent kingdom since 1946. It is among the most politically liberal countries of the Arab world, and, although it shares in the troubles affecting the region, its rulers have expressed a commitment to maintaining peace and stability.

The capital and largest city in the country is Amman—named for the Ammonites, who made the city their capital in the 13th century BCE. Amman was later a great city of Middle Eastern antiquity, Philadelphia, of the Roman Decapolis, and now serves as one of the region’s principal commercial and transportation centres as well as one of the Arab world’s major cultural capitals.

Although Jordan’s economy is relatively small and faces numerous obstacles, it is comparatively well diversified. Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of Jordan’s gross domestic product (GDP); transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction represent one-fifth of total GDP, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly that proportion. Remittances from Jordanians working abroad are a major source of foreign exchange.

However, although Jordan’s economy is ostensibly based on private enterprise, services—particularly government spending—account for about one-fourth of GDP and employ roughly one-third of the workforce. In addition, Jordan has increasingly been plagued by recession, debt, and unemployment since the mid-1990s, and the small size of the Jordanian market, fluctuations in agricultural production, a lack of capital, and the presence of large numbers of refugees have made it necessary for Jordan to continue to seek foreign aid. The Jordanian government has been slow to implement privatization. Despite efforts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to boost the private sector—including agreements to write off the country’s external debt and loans from the World Bank designed to revitalize Jordan’s economy—it was only in 1999 that the government began introducing a number of economic reforms. These efforts included Jordan’s entry into the World Trade Organization (in 2000) and the partial privatization of some state-owned enterprises.

Only a tiny fraction of Jordan’s land is arable, and the country imports some foodstuffs to meet its needs. Wheat and barley are the main crops of the rain-fed uplands, and irrigated land in the Jordan Valley produces citrus and other fruits, potatoes, vegetables (tomatoes and cucumbers), and olives. Pastureland is limited; although artesian wells have been dug to increase its area, much former pasture area has been turned over to the cultivation of olive and fruit trees, and large areas have been degraded to the point that they can barely support livestock. Sheep and goats are the most important livestock, but there are also some cattle, camels, horses, donkeys, and mules. Poultry is also kept.

Mineral resources include large deposits of phosphates, potash, limestone, and marble, as well as dolomite, kaolin, and salt. More recently discovered minerals include barite (the principal ore of the metallic element barium), quartzite, gypsum (used as a fertilizer), and feldspar, and there are unexploited deposits of copper, uranium, and shale oil. Although the country has no significant oil deposits, modest reserves of natural gas are located in its eastern desert. In 2003 the first section of a new pipeline from Egypt began delivering natural gas to Al-ʿAqabah.

Virtually all electric power in Jordan is generated by thermal plants, most of which are oil-fired. The major power stations are linked by a transmission system. By the early 21st century the government had completed a program to link the major cities and towns by a countrywide grid.

Beginning in the final decades of the 20th century, access to water became a major problem for Jordan—as well as a point of conflict among states in the region—as overuse of the Jordan River (and its tributary, the Yarmūk River) and excessive tapping of the region’s natural aquifers led to shortages throughout Jordan and surrounding countries. In 2000 Jordan and Syria secured funding for constructing a dam on the Yarmūk River that, in addition to storing water for Jordan, would also generate electricity for Syria. Construction of the Waḥdah (“Unity”) Dam began in 2004.

Manufacturing is concentrated around Amman. The extraction of phosphate, petroleum refining, and cement production are the country’s major heavy industries. Food, clothing, and a variety of consumer goods also are produced.

Jordan’s primary exports are clothing, chemicals and chemical products, and potash and phosphates; the main imports are machinery and apparatus, crude petroleum, and food products. Major sources of imports are Saudi Arabia, the United States, China, and the European Union (EU). Major destinations for exports are the United States, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. In 2000 Jordan signed a bilateral free trade agreement with the United States. The value of exports has been growing, but it does not cover that of imports; the deficit is financed by foreign grants, loans, and other forms of capital transfers. Although Jordan’s trade deficit has been large, it has been offset somewhat by revenue from tourism, remittances sent by Jordanians working abroad, earnings from foreign investments made by the central bank, and subsidies from other Arab and non-Arab governments.

Services, including public administration, defense, and retail sales, form the single most important component of Jordan’s economy in both value and employment. The country’s vulnerable geography has led to high military expenditures, which are well above the world average.

The Jordanian government vigorously promotes tourism, and the number of tourists visiting Jordan has grown dramatically since the mid-1990s. Visitors come mainly from the West to see the old biblical cities of the Jordan Valley and such wonders as the ancient city of Petra, designated a World Heritage site in 1985. Income from tourism, mostly consisting of foreign reserves, has become a major factor in Jordan’s efforts to reduce its balance-of-payments deficit.

Jordan has also lost much of its skilled labour to neighbouring countries—as many as 400,000 people left the kingdom in the early 1980s—although the problem has eased somewhat. This change is a result both of better employment opportunities within Jordan itself and of a curb on foreign labour demands by the Persian Gulf states.

The majority of the workforce is men, with women constituting roughly one-seventh of the total. The government employs nearly half of those working. About one-seventh of the population is unemployed, although income per capita has increased. Labour unions and employer organizations are legal, but the trade-union movement is weak; this is partly offset by the government, which has its own procedures for settling labour disputes.

About half of the government’s revenue is derived from taxes. Even though the government has made a great effort to reform the income tax, both to increase revenue and to redistribute income, revenue from indirect taxes continues to exceed that from direct taxes. Tax measures have been adopted to increase the rate of savings necessary for financing investments, and the government has implemented tax exemptions on foreign investments and on the transfer of foreign profits and capital.

Finally, I will leave a link which includes all companies and enterprises in Jordan, for those who want to research and discover more about this country. Thanks for reading.

All businesses address in Jordan: https://findsun.net/JO

0 notes

Text

Leading 10 Lots of Invaluable Currencies In Africa 2021

Pegged to the US dollar in 2003, Kuwait returned to the weighted foreign money basket in 2007, where it stays a powerful foreign money. Oman is one more nation that pegged its foreign money to the U.S. dollar at a set exchange fee. The Omani rial maintained its worth in opposition to the greenback because of Oman's historically tight monetary policy and financial restrictions. Omani policymakers have usually restricted the money supply to guard the nation in opposition to struggle and battle within the Middle East. That has impacted the nation's inflation price, and lending practices in Oman are inclined to favor risk-averse corporations and business ventures. The united dollars is the ninth strongest currencies on earth.

What is the most expensive currency 2020?

Kuwaiti Dinar: 1 KWD = 3.26 USD

The Kuwaiti dinar (KWD) was the most valuable government-backed currency as of 2020. Some currencies not backed by governments, such as gold and bitcoin, were actually worth far more. Substantial oil production helped augment Kuwait's wealth and support the value of the Kuwaiti dinar.

Well, there are one hundred eighty currencies used in 194 international locations at current. US Dollar or Euro is the forex that strikes the mind of most individuals when they think of currencies with the very best value or the strongest currency, which is not true in any respect. The world’s oldest currency that's still in use is the British Pound , US Dollar, then again, remains essentially the most traded foreign money in the world from some time now. This is the forex of each Liechtenstein and Switzerland. The most frequent exchange price for the currency is from the EUR to CHF.

Using Purchasing Power Parity To Search Out Essentially The Most Useful Foreign Money

That’s one of many less-known countries, but its large-scale economic system and improvement won it international respect, and the ability of its foreign money is demonstrated. [newline]The Dinar is the Hashemite Kingdom’s official foreign money on the Asian continent. It has Amman as capital and JOD’s currency code is 1 JOD, which is $1.forty one. In 1940 King Jordan himself launched the official forex, which has since continuously developed into the fourth most essential forex in the world.

Although it is a very small country, it's a relatively free economy in comparability to the remainder of the area.

The task of distributing the currency lies with the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

British Pound Sterling ranks on the number 5 in the listing of top 20 highest currencies within the World.

The Kuwaiti dinar was the most valuable government-backed forex as of 2020.

It's not fairly often that you simply come throughout a coin this old and in almost excellent condition. Ephraim Brasher was a goldsmith and silversmith within the New York City area in the late 1700s. Since the United States Mint was not operational yet, the colonies resorted to minting their very own coins. Private entrepreneurs corresponding to Brasher minted some of these cash.

Prime 10 Highest Currencies In Africa In 2021 Most Precious

The US Dollar is essentially the most traded foreign money in the forex market as of the time of writing this text. As of September 2018, about 1.69 trillion USD in circulation globally, where about 70% of those notes are circulated outdoors the US. The US Dollar is the most traded foreign money within the foreign exchange market as of today. The worth of forex differs the world over and infrequently change over time. The foreign money exchange rate converts the value of 1 form of forex into one other. Knowledge of this price is particularly helpful when traveling to different international locations.

What is the average salary in Iran?

A person working in Iran typically earns around 44,800,000 IRR per month. Salaries range from 11,300,000 IRR (lowest average) to 200,000,000 IRR (highest average, actual maximum salary is higher). This is the average monthly salary including housing, transport, and other benefits.

The fact that the Jordanian Dinar is on this list at all is something that comes as a surprise to lots of people because the nation is often provided with overseas aid. Most of its energy must be imported from close by countries and it typically struggles to provide enough water for everyone that's residing within the nation. It as soon as shared a forex with Palestine however gained independence from this country in 1946. Nevertheless it didn't get its personal foreign money until 1959 when the Jordanian Dinar was launched.

The nation is situated in Western Asia with the capital name of Kuwait City. On the other hand, it is also one of many largest suppliers of oil on the earth. That is the rationale Kuwaiti Dinar is included in some of the valuable currencies in the world. The foreign money has got extra respect from the world as a end result of financial standing of most of the European countries. It attention-grabbing to know that it's the currency of about 25 member states of the Eurozone. It was formally introduced because the foreign money of this area in 1999 with the symbol of €.

For many international locations, that is the reserve foreign money of the state. Although the US dollar might be the commonest currency for worldwide trade, it's not as highly valued as one would anticipate. In truth, some of the nations talked about in the following list of the costliest foreign money on the earth, have a far larger trade rate, sometimes doubling or tripling that of the US dollar. So without going into additional detail, let us take a more in-depth take a look at these currencies and find out how a lot they're actually value. Despite being the world’s most traded currency, the USD surprisingly appears on the backside of the list. This has to do with the reality that its value has depreciated during the last couple of years, owing to its present account deficit and excellent US debt.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

When Fred Halliday—scholar, activist, journalist and teacher—died two years ago at the too-early age of 64, obituaries and tributes swamped the British press; the New Statesman subtitled its remembrance “The death of a great internationalist.” Halliday was a truly original thinker, a combination of Hannah Arendt (in her concern for the connection between ethics and politics) and Isaac Deutscher (in his materialist yet supple approach to history). Halliday also knew a little something about the Middle East: he spoke Arabic, Farsi and at least seven other languages, and he traveled widely throughout the region, including in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Palestine, Israel, Libya and Algeria. He is one of the very few writers who, after 9/11, understood the synthesis between fighting radical Islam and opposing the brutal inequities of the neoliberal global order. He was an uncategorizable independent, supporting, for instance, the communist government in Afghanistan and the US invasion of that country. He embodied the dialectic between utopianism and realism. In his scholarship and research, in his outspokenness and courtesy, in the complexity of his thinking, he was the model of a public intellectual. It is Halliday’s writings—not those of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens or Tariq Ali—that can elucidate the meaning of today’s most virulent conflicts; it is Halliday who represented radicalism with a human face. It says something sad, and discouraging, about intellectual life in our country that Halliday’s death—which is to say, his work—was ignored not only by mainstream publications like The New York Times but by their left-wing alternatives too (including this one).

It is cheering, then, that a selection of essays, written by Halliday for the website openDemocracy between 2004 and 2009, has just been published by Yale University Press. Called Political Journeys, it gives a taste—though only that—of the extraordinary range of Halliday’s interests; included here are analyses of communism , the cold war, Iran’s revolution, post-Saddam Iraq, violence and politics, radical Islam, the legacies of 1968 and feminism. The book gives a sense, too, of Halliday’s dry humor—he loved to recount irreverent political jokes from the countries he had visited—and his affection for lists, as in the essay “The World’s Twelve Worst Ideas” (No. 2: “The only thing ‘they’ understand is force”). But most of the articles, written as they were for the Internet, are comparatively short and represent a brief span in a long career; this necessarily sporadic volume will, one hopes, lead readers to some of Halliday’s two dozen other books and more extensive essays.

Political Journeys is a well-chosen title for the collection. It alludes not just to Halliday’s travels but also to the ways his ideas—especially about revolution, imperialism and human rights—changed in reaction to tumultuous world events over the course of four decades. For this he has often been attacked, even posthumously. Earlier this year, Columbia University professor Joseph Massad opened a piece about Syria, published on the Al Jazeera website, by dismissing Halliday—along with his “Arab turncoat comrades”—as a “pro-imperial apologist.” (Massad also put forth the novel idea that Syria “has been…an agent of US imperialism,” which might be news to Bashar al-Assad and the leaders of Iran and Hezbollah, Syria’s allies in the so-called axis of resistance.) Yet it was precisely Halliday’s intellectual flexibility—his ability to derive theory from experience rather than shoehorn the latter into the former—that was one of his greatest strengths. Pace Massad,

Halliday didn’t move from Marxism into imperialism, neoconservatism, neoliberalism or “turncoatism”; rather, he developed a deeper, more humane and far sturdier kind of radicalism. It was one that refused to hide—much less celebrate—repression, carnage and virulent nationalism behind the banner of progress, world revolution, selfdetermination or anti-colonialism. Halliday sought not to reject the socialist tradition but to reconnect it to its heritage—derived from the Enlightenment, from 1789, from 1848— of reason, rights, secularism and freedom. He would also develop an unsparing critique of the anti-humanism that, he thought, was ineradicably embedded in the revolution of 1917 and its successors.

Halliday believed that the duty of committed intellectuals is to keep their eyes open, to learn from history, to be humble enough to be surprised (and to admit being wrong). The alternative was what he called “Rip van Winkle socialism.” He sometimes told his friends, “At my funeral the one thing no one must ever say is that ‘Comrade Halliday never wavered, never changed his mind.’”

* * *

Fred Halliday was born in 1946 in Dublin and raised in Dundalk, a town near the northern border that, he pointed out, The Rough Guide to Ireland advises tourists to avoid. The Irish “question” and Irish politics remained, for him, a touchstone—though more as a warning than an inspiration, especially when it came to Mideast politics. The unhappy lessons of Ireland, he wrote in 1996, included “the illusions and delusions of nationalism” and “the corrosive myths of deliverance through purely military struggle.” He added: “A good dose of contemporary Irish history makes one sceptical about much of the rhetoric that issues from dominant and dominated alike.… [A] critique of imperialism needs at the very least to be matched by some reserve about most of the strategies proclaimed for overcoming it.” Growing up in the midst of the Troubles, Halliday developed, among other things, a healthy aversion to histrionic nationalism and the repugnant concept of “progressive atrocities.”

Halliday graduated from Oxford in 1967 and then attended the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Later he would earn a PhD from the London School of Economics (LSE), where, for over two decades, he taught students from around the world and was a founder of its Centre for the Study of Human Rights. (The intellectual and governing classes of the Middle East are sprinkled with his graduates.) He was an early editor of the radical newspaper Black Dwarf and, from 1969 to 1983, a member of the editorial board of the New Left Review, a journal for which he occasionally wrote even after he broke with it over key political issues. He immersed himself in the revolutionary movements of his time and gathered an enviable range of friends, interlocutors and contacts along the way: traveling with Maoist Dhofari rebels in Oman; working at a student camp in Cuba; visiting Nasser’s Egypt, Ben Bella’s Algeria, Palestinian guerrillas in Jordan and Marxist Ethiopia and South Yemen (the subject of his dissertation). He wasn’t shy: he proposed a two-state solution to Ghassan Kanafani of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, infamous for its hijackings; argued with Iran’s foreign minister about the goals of an Islamic revolution; told Hezbollah’s Sheik Naim Qassem that the group’s use of Koranic verses denouncing Jews was racist—“a point,” Halliday dryly noted, “he evidently did not accept.”

Halliday received, and accepted, invitations to lecture in some of the Middle East’s most repressive countries, including Ahmadinejad’s Iran, Qaddafi’s Libya and Saddam’s Iraq, where a government official told him, without shame or embarrassment, that Amnesty International’s reports on the regime’s tortures and executions were correct. Clearly, he was no boycotter. But neither was he seduced by these visits: in 1990, he described Iraq as a “ferocious dictatorship, marked by terror and coercion unparalleled within the Arab world”; in 2009, he reported that the supposedly new, rehabilitated Libya was just like the old, outcast Libya: a “grotesque entity” and “protection racket” that was regarded as a joke throughout the Arab world. His moral compass remained intact: that year, he warned the LSE not to accept a £ 1.5 million donation from the so-called Charitable and Development Foundation of the dictator’s son, Saif el-Qaddafi. Alas, greed trumped principle, and Halliday’s arguments were rejected—which led, once the Arab Spring reached Libya, to the LSE’s public disgrace and the resignation of its director.

* * *

In May 1981, Halliday published an article on Israel and Palestine in MERIP Reports, a well-respected Washington journal that focuses on the Middle East and is closely identified with the Palestinian cause. It is an astonishing piece, especially in the context of its era, more than a decade before the Palestine Liberation Organization recognized Israel’s right to exist and the signing of the Oslo Accords. It is no exaggeration to say that, at the time, the vast majority of the left, Marxist and not, held anti-Israel positions of various degrees of ferocity; to do otherwise was to risk pariahdom.

While harshly critical of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and of the occupation , Halliday proceeded to question—and forcefully rebuke—the bedrock beliefs of the left: that Israel was a colonial state comparable to South Africa; that Israelis were not a nation and had no right to self-determination; that Israel was a recently formed and therefore inauthentic country (most states in the Middle East—including, for that matter, Palestine— are modern creations of imperialist powers); that a binational state was desired by either Israelis or Palestinians and, therefore, could be a recipe for anything other than civil war and a harshly authoritarian government. (Halliday asked a question often ignored by revolutionaries: Why would anyone want to live under such a regime?)

Most of all, he challenged the irredentism of the Palestinian movement and its supporters. Partition, he presciently warned, is “the only just and the only practical way forward for the Palestinians. They will continue to pay a terrible price, verging on national annihilation, if they prefer to adopt easier but in fact less realizable substitutes, and if their allies and supposed friends continue to urge such a course upon them.” Halliday stressed that a truly revolutionary strategy cannot be “at variance with reality.” Solidarity without realism is a form of betrayal.

The reality principle, and its absence, was a theme Halliday would return to frequently, as in his reappraisal of the legacy of 1968. “It does not deserve the sneering, partisan dismissal,” he wrote in 2008. But nostalgic celebration was also unearned, for “the problem is that in many ways, we lost.” Despite triumphal rhetoric, the year of the barricades led not to worldwide revolution but to conservative governments in France, England and the United States (Richard Nixon). In the communist world, the situation was even worse: “It was not the emancipatory imagination but the cold calculation of party and state that was ‘seizing power.’” In Prague, socialist reform was crushed; in Beijing, the Cultural Revolution’s frenzy reached new heights.

Yet Halliday, like most of us, was sometimes guilty of letting wishful thinking cloud his vision too. In 2004, he called for the United Nations to assume authority in Iraq, which was then in free fall. This ignored the fact that Al Qaeda’s shocking bombings of the UN’s Baghdad mission the previous year—resulting in the death of Sergio de Mello, the secretary general’s special representative in Iraq, and so many others—had disposed, rather definitively, of that issue; the UN had withdrawn its staffers and, clearly, could not ask them to undertake another death mission. (Nor was there any indication that the UN’s member nations—many of whom opposed any intervention in Iraq—would have supported such a proposition.) And his claim, made in 2007, that “a set of common values is indeed shared across the world,” including a commitment to “democracy and human rights,” is hard to square with much of Halliday’s own reporting—such as his 1984 encounter with a longtime acquaintance named Muhammad, who had formerly been a member of the Iranian left. Now a supporter of the regime, Muhammad visits Halliday in London and explains, “We don’t give a damn for the United Nations.… We don’t give a damn for that bloody organisation, Amnesty International. We don’t give a damn what anyone in the world thinks.… We have made an Islamic Revolution and we are going to stick to it, even if it means a third world war.… We want none of the damn democracy of the West, or the socalled freedoms of the East.… You must understand the culture of martyrdom in our country.” Indeed, Halliday’s optimism of the intellect here is belied by even a casual look at any of the world’s major newspapers— whether from New York or Paris, Baghdad or Beirut—on any given day.

* * *

Iran, which Halliday first visited in the 1960s as an undergraduate, was foundational to his political development; he analyzed, and re-analyzed, its revolution many times, as if it was a wound that could not stop hurting. (Iran is the only country to which Political Journeys devotes an entire section of essays.) His initial study of the country, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, was written just before the anti-Shah revolution of early 1979. Based on careful observation and research, the book scrupulously analyzed Iran’s class structure, economy, armed forces, government, opposition movements, foreign policy—everything, that is, but the role of religion, which Halliday seemed to regard as essentially a front for political demands, and which he vastly underestimated. The book’s last sentence reads, “It is quite possible that before too long the Iranian people will chase the Pahlavi dictator and his associates from power… and build a prosperous and socialist Iran.”

Events moved quickly. In August 1979, Halliday filed two terrifying dispatches from Tehran, published in the New Statesman, documenting the chaotic atmosphere of fear and xenophobia, the outlawing of newspapers and political parties, and the brutal crackdown on women, intellectuals, liberals, leftists and secularists. “It does not take one long to sense the ferocious right-wing Islamist fervour that grips much of Iran today,” he began. Later, he would write, “I have stood on the streets of Tehran and seen tens of thousands of people…shouting, ‘Marg bar liberalizm’ (‘Death to liberalism’). It was not a happy sight; among other things, they meant me.” A revolution, he realized, could be genuinely anti-imperialist and genuinely reactionary.

But the problem wasn’t only Iran or radical Islam. As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, it became clear—or should have—that most of the third world’s secular revolutions and coups (in Algeria, Syria, Libya, Ethiopia and, especially, Iraq) had failed to fulfill their emancipatory promises. Each became a one-party dictatorship based on repression, torture and murder; each stifled its citizens politically, intellectually, artistically, even sexually; each remained mired in inequality and underdevelopment. None of this could be explained, much less justified, by the legacy of colonialism or the crimes of imperialism, real as those are. These were among the central issues that led to Halliday’s rift with the New Left Review—and that continue to divide the left, both here and abroad. Indeed, it is precisely these issues that often underlie (and sometimes determine) the debates over humanitarian intervention, the meaning of solidarity, the US role as a global power, the centrality of human rights and of feminism, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. (In 2006, Halliday would sum up his points of contention with his former comrades, especially their support of death squads and jihadists in the Iraq War : “The position of the New Left Review is that the future of humanity lies in the back streets of Fallujah.”)

Halliday’s revised thinking—his emphasis on democracy and rights; his aversion to the particularist claims of tribe, nation, religion or identity politics; his unapologetic secularism; his questioning of imperialism as a purely regressive force—is evident in his enormously compelling book Islam and the Myth of Confrontation, published in 1996. (Halliday dedicated it to the memory of four Iranian friends, whom he lauded as “opponents of religiously sanctioned dictatorship.”) In this volume he took on two still prevalent, and still contested, concepts: the idea of human rights as a Western imposition on the third world, and the theory of “Orientalism.”

Halliday argued that, despite the assertions of covenants such as the 1981 Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights (which defines “God alone” as “the Source of all human rights”) and the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (which defines “all human beings” as “Allah’s subjects”), there is no such thing as Islamic human rights—or, indeed, of rights derived from any religious source. Such rights apply to everyone and, therefore, must be based on man-made, universalist principles or they are nothing: it is the “equality of humanity,” not the equality before God, that they assert. (That is why they are human rights.) Because rights are grounded in the dignity of the individual, not in any transcendent or divine authority, they can be neither granted nor rescinded by religious authorities, and no country, culture or region can claim exemption from them by appealing to holy texts, a history of oppression, revered traditions or because rights “somehow embody ‘Western’ prejudice and hegemony.”

In this light, the search for a kinder, gentler version of Islam—or, for that matter, of any religion—as the basis of rights is “doomed” to failure; for Halliday, the question of a religion’s content was entirely irrelevant. “Secularism is no guarantee of liberty or the protection of rights, as the very secular totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century have shown,” he argued. “However, it remains a precondition, because it enables the rights of the individual to be invoked against authority.… The central issue is not, therefore, one of finding some more liberal, or compatible, interpretation of Islamic thinking, but of removing the discussion of rights from the claims of religion itself.… It is this issue above all which those committed to a liberal interpretation of Islam seek to avoid.” The issues that Halliday raised in 1996 are by no means settled today, and they are anything but abstract; on the contrary, the Arab uprisings have forced them insistently to the fore. In Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, secularists and Islamists struggle over the role (if any) of Islam in writing new constitutions and legal codes; at the United Nations, new leaders such as Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi and Yemen’s Abed Rabbu Mansour Hadi argue that the right to free speech ends when it “blasphemes” against Islamic beliefs.

But more than a defense of secularism is at stake here. Halliday argued that the very idea of a unitary, reliably oppressive behemoth called the West—on which so much antiimperialist and “dependency” theory rested— was false. “Far from there having been, or being, a monolithic, imperialist and racist ‘West’ that produced human rights discourse, the ‘West’ itself is in several ways a diverse, conflictual entity,” he wrote. “The notion of human rights was not the creation of the states and ruling elites of France, the USA, or any other Western power, but emerged with the rise of social movements and associate ideologies that contested these states and elites.” The West embodied emancipation and oppression, equality and racism, abolitionism and slavery, universalism and colonialism. Political theories and practices that refuse to acknowledge this—proudly brandishing their “anti-Western” credentials—will be based on the shakiest foundations.

* * *

The argument between advocates of the concept of “Orientalism,” put forth most famously by Edward Said, and its critics—often associated with the scholar Bernard Lewis—was close to Halliday. Lewis had been a mentor of his at SOAS, and one he admired; Said, whom Halliday described as “a man of exemplary intellectual and political courage,” was a friend. (Though not forever: Said stopped talking to Halliday when the two disagreed on the first Gulf War.) Yet on closer look, Lewis and Said shared an orientation: both had rejected a materialist analysis of Arab (and colonial) history and politics in favor of a metadebate about literature. “For neither of them,” Halliday argued, “does the analysis of what actually happens in these societies, as distinct from what people say and write about them…come first.” Increasingly, Halliday would regard the Orientalist debate as one that deformed, and diverted, the discipline of Mideast studies and helped to foster a vituperative atmosphere.

Said had argued that, for several centuries, British and French writers, statesmen and others had created a static, mythical Middle East—sometimes romanticized, sometimes denigrated, always objectified— as part of an unwaveringly racist, imperialist project. (Indeed, Said’s book has turned the word “Orientalist,” which used to refer to scholars of the Muslim, Arab and Asian worlds, into a term of opprobrium.) With sobriety and respect, Halliday considered and, in the end, devastatingly refuted the theory’s major tenets. With its sweeping, all-encompassing claims, he argued, the concept of Orientalism was a form of fundamentalism: “We should be cautious about any critique which identifies such a widespread and pervasive single error at the core of a range of literature.” It was based on a widely held yet entirely unsubstantiated belief that Europe bore a particular hostility toward the Muslim world: “The thesis of some enduring, transhistorical hostility to the orient, the Arabs, the Islamic world, is a myth.” It was undialectical, ignoring not only the myths that Easterners projected against the West—ignorant stereotyping is, if nothing else, a busy two-way street—but the ways the East itself reproduced the tropes of Orientalism: “A few hours in the library with the Middle Eastern section of the Summary of World Broadcasts will do wonders for anyone who thinks reification and discursive interpellation are the prerogative of Western writers on the region.” In fact, Islamists can be among the greatest Orientalists, for many insist on an Islam that is eternal, opaque and monolithic.

Most of all, though, Halliday questioned the assumption that the presumably impure origin of an idea necessarily negates its truth value. “Said implies that because ideas are produced in a context of domination, or directly in the service of domination, they are therefore invalid.” Carried to its logical conclusion, of course, this would entail a rejection of modernity itself—from its foundational ideas to its medical, technological and scientific advances—for all were produced “in the context of imperialism and capitalism: it would be odd if this were not so. But this tells us little about their validity.” (“Antiimperialism” and “self-determination” are, we might note, Western concepts, just as penicillin, the computer, the machine gun and the atom bomb are Western inventions.) And he questioned a key tenet of postcolonial studies and postcolonial politics: that the powerless are either more insightful or more ethical than their oppressors. “The very condition of being oppressed…is likely to produce its own distorted forms of perception: mythical history, hatred and chauvinism towards others, conspiracy theories of all stripes, unreal phantasms of emancipation.” Suffering is not necessarily the mother of wisdom.

But if Halliday was a foe of the simplicities of Orientalism, he was equally opposed to Samuel Huntington’s notion of “the clash of civilizations”—a concept that, he pointed out, was as beloved by Osama bin Laden as by neoconservatives—and to essentialist fictions like “the Islamic world” and “the Arab mind.” (On this, he and Said certainly agreed.) More than fifty diverse countries contain Muslim majorities; the job of the intellectual—whether located inside or outside the region—was to specify and demystify rather than deal in lumpy, ignorant generalities. “Disaggregation and explanation, rather than invocations of the timeless essence of cultures,” was the Mideast scholar’s prime task, Halliday insisted. He rejected mystified concepts such as Islamic banking and Islamic economics (“Anyone who has studied the economic history of the Muslim world…will know that business is conducted as it is everywhere, on sound capitalist principles”); the Islamic road to development (Iran’s economy was “a perfectly recognisable ramshackle rentier economy, laced with corruption and inefficiency”); and Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia, Halliday noted, has virtually no basis in the Koran). Echoing E.P. Thompson, Halliday argued that much of what passes for the ancient and authentic in the Islamic world—including Islamic fundamentalism itself—is the creation of modernity, and can be productively analyzed only within a political context.

Halliday proposed that even the Iranian Revolution—with its mobilization of the masses, consolidation of state power, repressive security institutions and attempts to export itself—had, despite its peculiar ideology, reprised the basic dynamics of modern, secular revolutions: “not that of Mecca and Medina in the seventh century but that of Paris in the 1790s and Moscow and St Petersburg in the 1920s.” Islam, Halliday insisted, could not explain the trajectory of that revolution or, for that matter, the politics of the greater Middle East.

Was Halliday right? Surely yes, in his refusal of essentialist fantasies and apolitical thinking. And in some ways, the Arab uprisings have confirmed everything for which he had spent a lifetime arguing. Here were populist movements demanding democratic institutions, transparency, and an end to tyranny and corruption; here were hundreds of thousands of protesters demanding entry into the modern world, not its negation; here was the assertion of participatory citizenship over passive subjecthood. Yet the subsequent trajectory of those initial revolts also proved him wrong: nowhere else in the contemporary world have democratic elections led to the triumph of religious parties. Nowhere else do intra-religious schisms result in the widespread carnage of the Shiite-Sunni split. Nowhere else do the democratic rights to freely speak, publish and create collide with strictures against blasphemy—even among some presumed democrats. Nowhere else does the fall of dictatorship and the assertion of self-determination translate, so quickly and so often, into attacks on women’s equality. “Islam explains little of what happens” in Turkey and Pakistan, Halliday wrote in 2002, and he believed this to be true of the region as a whole. Yet I doubt there are many Turks or Pakistanis (or, for that matter, Iranians, Egyptians, Algerians, Lebanese, Afghans, Saudis or Yemenis) who would agree. Can they all be the victims of false consciousness?

Here, I think, lies the problem: in his fight against lazy generalizations about Islam and its misuse as a univocal explanation, Halliday sometimes sought to scrub away, or at least radically minimize, Islam itself, as was demonstrated by his early book on Iran. It is almost as if he—the confirmed skeptic, the lover of reason, the staunch secularist, the self-proclaimed bani tanwir (“child of enlightenment”)—could not quite believe in religion as a force unto itself, and an astonishingly powerful one at that. “What people actually do,” he wrote in 2002, “is not determined by ideology.” This is, we might note, a classic Marxist position, in which the “superstructure” of belief is subsumed beneath class and politics. Yet Halliday’s erstwhile Iranian friend Muhammad— and, indeed, so many of the events that Halliday himself witnessed—told him otherwise. And as organizations as diverse as the Nazi Party and Al Qaeda have shown, rational, politically focused strategies and utterly lunatic ideologies can, alas, coexist.

* * *

In the immediate aftermath of September 11, Halliday was clear about several points: that the attacks would resonate throughout global politics, changing them for many decades to come; that Al Qaeda was a “demented” product not of ancient Islam but of modernity, and represented “the anti-imperialism of racists and murderers”; and that terrorist violence “from below,” though not directly caused by poverty, could not be severed from the grotesque inequalities that international capital had created. In 2004, he wrote, “The central challenge facing the world, in the face of 9/11 and all the other terrorist acts preceding and following it, is to create a global order that defends security while making real the aspirations to equality and mutual respect that modernity has aroused and proclaimed but spectacularly failed so far to fulfil.” This was not a question of either/or, but of and/ and. Ever the dialectician, Halliday observed that imperialism and terrorism are hardly antagonists; rather, they share a “central arrogance,” each “forcing their policies and views onto those unable to protect themselves, and proclaiming their virtue in the name of some political goal or project that they alone have defined.” And he noted with anger and sorrow how terrorism—which has killed far more people in the East than in the West —had transformed millions of people throughout the world into bewildered bystanders, creating an internationale of fear.

Afghanistan had been one of Halliday’s key areas of study, and he repeatedly pointed to several crucial facts that many Americans still resist understanding. Al Qaeda did not spring out of nowhere, much less from its beloved eighth century. It was Ronald Reagan’s arming of the anti-Soviet guerrillas— even after the Soviet pullout in early 1989, when Kabul’s communist government still stood—that was instrumental in creating the Islamist militias and warlord groups, some of which transformed themselves into the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Thus had our fanatical anti-communism led to the empowerment of “the crazed counter-revolutionaries of the Islamic right.” For Halliday there was no schadenfreude in this, no gloating, no talk of chickens coming home to roost or of blowback (a concept that fundamentally misunderstands— and moralizes—historic causation: was Sobibor the blowback from the Versailles Treaty?). But he insisted, rightly, that the crisis of 9/11 could not be understood, much less successfully confronted, in the absence of engaging this “policy of world-historical criminality and folly.”

Halliday had supported the US overthrow of both the Taliban and Saddam (in addition to military intervention against Saddam in the first Gulf War, and against Milosevic in Bosnia and Kosovo). He criticized three tendencies of the post-9/11 world with increasing dismay, though not quite despair: the retreat into rabid nationalism in both East and West; the Bush administration’s conduct in Iraq and in international affairs generally (“The United States is dragging the Western world…towards a global abyss,” he warned in 2004); and the left’s romance with jihad, especially in relation to Hamas, Hezbollah and the Iraqi “resistance.” And indeed, it was somewhat shocking to read Tariq Ali, writing in the New Left Review in the especially bloody year of 2006, exulting in the rise of “Hamas, Hizbollah, the Sadr brigades and the Basij.… A radical wind is blowing from the alleys and shacks of the latter-day wretched of the earth.” Or, more recently, to find his colleague Perry Anderson arguing that the “priority” of Egypt’s new, post-Mubarak government should be to annul the country’s “abject” peace treaty with Israel as a way of recovering “democratic Arab dignity.” Rip van Winkle socialism, indeed.

After September 11, Halliday focused much of his intellectual energy on explaining the ways the attacks and their serial, convulsive aftermaths were decisively changing international relations. While classic internationalism—in the sense of humane solidarity with the suffering of others—was imperiled, a kind of militarized internationalism was on the rise. Conflicts that had been relatively distinct, except on a rhetorical level, had become ominously entwined and the ante of violence—especially against civilians—cruelly raised. “Events in Lebanon and Israel, Iraq and Afghanistan, Turkey and Libya are becoming comprehensible only in a broader regional and even global context,” he wrote in 2006. This new dispensation, which he dubbed the “Greater West Asian Crisis,” represented a struggle for political supremacy in a region that now included not just the Arab world and Israel but also Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan, among others—including a plethora of volatile nonstate militias that are beholden to no constituencies and recognize no restraints. While some conflicts, such as Hezbollah versus Israel, might still be geographically confined, none could be politically or, because of the existence of transnational guerrillas, operationally confined. (Consider, for instance, the reported presence of Islamist fighters from Chechnya and Pakistan in Syria’s civil war.) Halliday warned that the resulting strife would be “more complex, multilayered and long-lasting than any of the individual crises, revolutions or wars that characterized the Middle East.” This was written six years ago; despite the hopefulness of the subsequent Arab Spring revolts, it would be difficult to dispute the alarming vision contained therein.

* * *

In the last decade of his life, Halliday turned, with an urgency both intellectual and moral, to the legacy of revolution in the twentieth century. His writings on this topic—precisely because they are the work of a writer deeply embedded in, and respectful of, the Marxist tradition and committed to the creation of what one can call, without cynicism, a more just world—are important for anyone who seeks to understand the history of the past century or the bewilderments of the present one. These essays make for painful reading, too—especially, I think, for leftists—in their willingness to question, and discard, comforting beliefs.

Halliday’s re-evaluation shared nothing with the smug rejection of revolution that had become so fashionable after 1989, or with the disparagement of communism as an “aberrant illusion.” To the contrary: “Millions of people struggled for and believed in this ideal,” he wrote in 2009. “As much as liberalism, communism was itself a product of modernity…and of the injustices and brutalities associated with it.” Nor had Halliday signed on to a celebration of the neoliberal world order: “The challenge that confronted Marx and Engels,” he wrote in 2008, “still stands, namely that of countering the exploitation, inequality, oppression, and waste of the contemporary capitalist order with a radical, cooperative, international political order.” Against flat-earthers like Thomas Friedman, he argued that the globalized world of the twenty-first century is more unequal than its predecessors.

And so the question of what is to be done still remained, but had to be faced with far more humility and critical acumen than ever before. If Halliday had little sympathy for talk of failed gods, he was equally impatient with the “vacuous radicalisms” and romanticized revival of tattered revolutionary ideals that permeate too much of the left, including—or perhaps especially— the anti-globalization and solidarity movements. The idealization of violence (“the second intifada has been a disaster for the Palestinians”); the eschewing of long-term political organizing in favor of dramatic but impotent protests; the failure to study the complex and blood-soaked trajectory of the past century’s revolutions; the Pavlovian identification with virtually every oppositional movement, regardless of its real political aims: all of this was, in Halliday’s view, the road to both tragedy and farce. “The anti-globalization movement has taken over a critique of capitalism without…reflecting on what actually happened in the 20th century,” he told an interviewer in 2006. “I read the stuff coming out of Porto Alegre and my hair falls out.”