#Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Text

#covid-19#covid 19#sars cov 2#covid#Long covid#JAMA Network#Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection#Tanayott Thaweethai PhD#Sarah E. Jolley MD#Elizabeth W. Karlson MD MS#Covid-19 data journalism#Betsy Ladyzhets#Researcher#Machine learning/AI#Research and Advocacy#Hannah Davis#Patient Led Research#MEAction Network#Media#Health and science#Health and science reporting

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

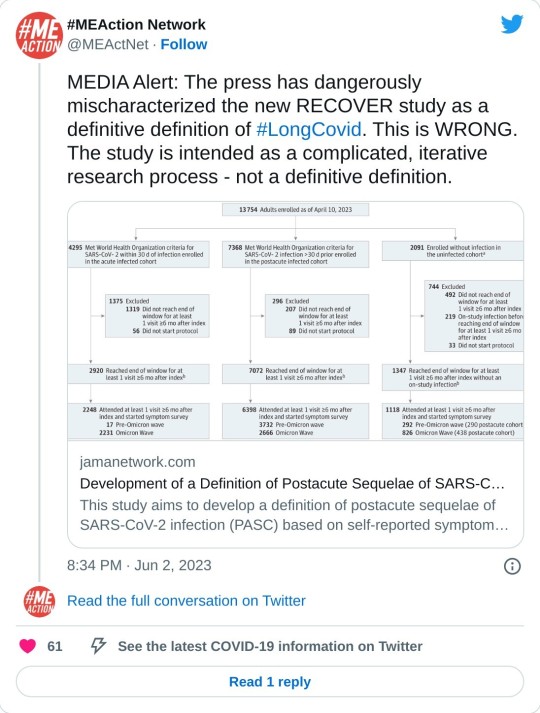

On May 25 of this year, JAMA published Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (“Definition”), an “original investigation” whose authors were drawn from the RECOVER Consortium, an initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)[1]. This was an initially welcome development for Long Covid sufferers and activists, since questions had arisen about what exactly patients were getting for the billion dollars RECOVER was appropriated. From STAT:

The federal government has burned through more than $1 billion to study long Covid, an effort to help the millions of Americans who experience brain fog, fatigue, and other symptoms after recovering from a coronavirus infection.

There’s basically nothing to show for it.

The National Institutes of Health hasn’t signed up a single patient to test any potential treatments — despite a clear mandate from Congress to study them.

Instead, the NIH spent the majority of its money on broader, observational research that won’t directly bring relief to patients. But it still hasn’t published any findings from the patients who joined that study, almost two years after it started.

(The STAT article, NC hot take here on April 20, is worth reading in full.) Perhaps unfairly to NIH — one is tempted to say that the mountain has labored, and brought forth a coprolite — a CERN-level headcount may explain both RECOVER’s glacial pace, and its high cost:

That’s a lot of violin lessons for a lot of little Madisons!

“Definition” falls resoundingly into the research (and not treatment) bucket. In this post, I will first look at the public relations debacle (if debacle it was) that immediately followed its release; then I will look at its problematic methodology, and briefly conclude. (Please note that I feel qualified to speak on public relations and institutional issues; very much less so on research methodology, which actually involves (dread word) statistics. So I hope readers will bear with me and correct where necessary.)

The Public Relations Debacle

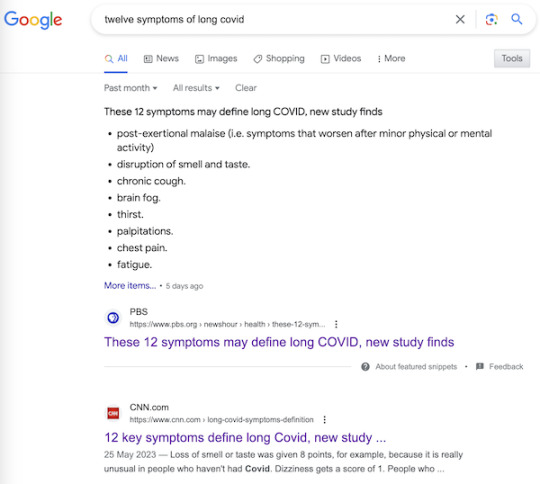

Our famously free press instantly framed “Definition” as a checklist of Long Covid (LC) symptoms. Here are the headlines. For the common reader:

12 key symptoms define long Covid, new study shows, bringing treatments closer CNN

Long COVID is defined by these 12 symptoms, new study finds CBS

Scientists Identify 12 Major Symptoms of Long Covid Smithsonian

These 12 symptoms may define long COVID, new study finds PBS News Hour

These Are the 12 Major Symptoms of Long COVID Daily Beast

(We will get to the actual so-called “12[2] Symptoms” when we look at methodology.) And for readers in the health industry:

For the first time, researchers identify 12 symptoms of long covid Chief Healthcare Executive

12 symptoms of long COVID, FDA Paxlovid approval & mpox vaccines with Andrea Garcia, JD, MPH AMA Update

Finally! These 12 symptoms define long COVID, say researchers ALM Benefits Pro

With these last three, we can easily see the CEO handing a copy of their “12 symptoms” article to a doctor, the doctor double-checking that headline against the AMA Update’s headline, and incorporating the NIH-branded 12-point checklist into their case notes going forward, and the medical coders at the insurance company (I love that word, “benefits”) nodding approvingly. At last, the clinicians have a checklist! They know what to do!

We’ll see why the whole notion of a checklist with twelve items is wrong and off-point for what “Definition” was actually, or at least putatively, trying to do, but for now it’s easy to see why the press went down this path (or over this cliff). Here is the press release from NIH that accompanied “Definition”‘s publication in JAMA:

Researchers examined data from 9,764 adults, including 8,646 who had COVID-19 and 1,118 who did not have COVID-19. They assessed more than 30 symptoms across multiple body areas and organs and applied statistical analyses that identified 12 symptoms that most set apart those with and without long COVID: post-exertional malaise, fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire or capacity, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic cough, chest pain, and abnormal movements.

They then established a scoring system based on patient-reported symptoms. By assigning points to each of the 12 symptoms, the team gave each patient a score based on symptom combinations. With these scores in hand, researchers identified a meaningful threshold for identifying participants with long COVID. They also found that certain symptoms occurred together and defined four subgroups or “clusters” with a range of impacts on health

So there are 12 symptoms, right? Just like the headline says? Certainly, that’s what a normal reader would take away. And if a temporally pressed reporter goes to the JAMA original and searches on “12”, they find this:

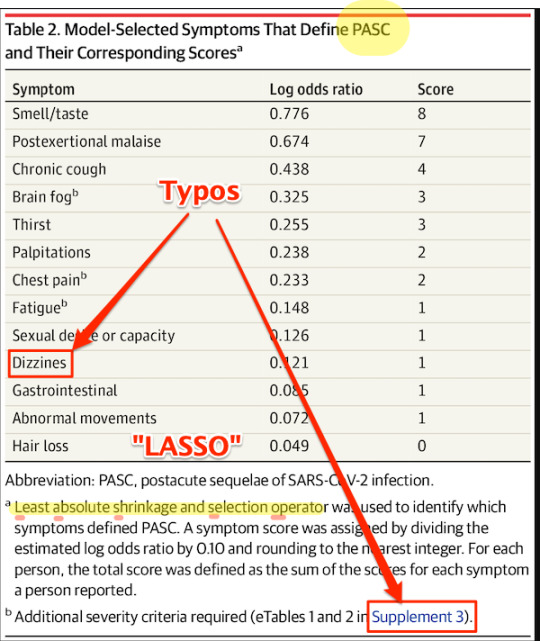

Using the full cohort, LASSO identified 12 symptoms with corresponding scores ranging from 1 to 8 (Table 2). The optimal PASC score threshold used was 12 or greater

And if the reporter goes further and finds Table 2 (we’ll get there when we look at methodology), they will see, yes, 12 symptoms (in rank order identified by something called LASSO).

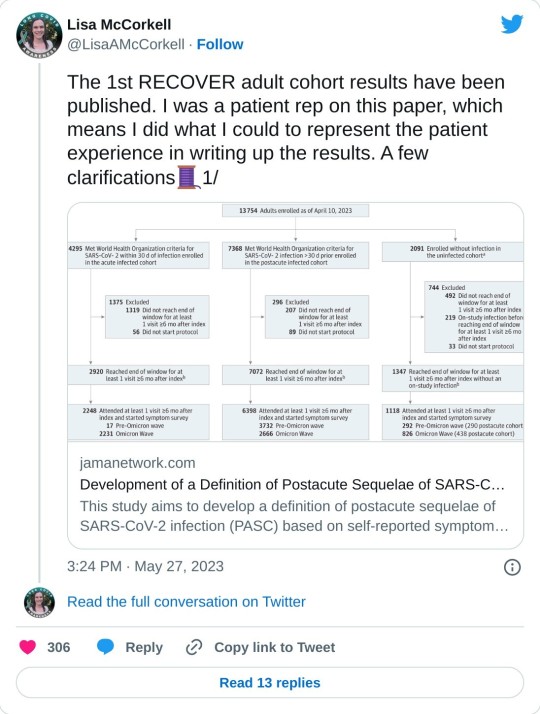

So it’s easy to see how the headlines were written as they were written, and how the newsroom wrote the stories as they did. The wee problem: The twelve symptoms are not meant to be used clinically, for diagnosis.[3], Lisa McCorkell was the patient representative[4] for the paper, and has this to say:

Nevertheless, the “12 symptoms” are out of the barn and in the next county, and as a result, you get search results like this:

It’s very easy to imagine a harried ER room nurse hearing “12 Symptoms” on the TV news[5], doublechecking with a Google search, and then making clinical decisions based on a checklist not fit for purpose. Or, for that matter, a doctor.

Now, to be fair to the authors, once one grasps the idea that symptoms, even clusters of symptoms, can exist, and still not be suitable for diagnosis by a clinician, the careful language of “Definition” is clear, starting with the title: “Development of a Definition.” And in the Meaning section of the Abstract:

A framework for identifying PASC cases based on symptoms is a first step to defining PASC as a new condition. These findings require iterative refinement that further incorporates clinical features to arrive at actionable definitions of PASC.

Well and good, but do you see “framework” in the headlines? “Iterative”? “First step”? No? Now, I’d like to exonerate the authors of “Definitions” — “They’re just scientists!” — for that debacle, but I cannot, completely. The authors are well-compensated, sophisticated, and aware professionals; PMC, in fact. I cannot believe that the Cochrane “fools gold” antimask study debacle went unobserved at NIH, especially in the press office. How was it possible that “Definitions” was simply… printed as it was, and no strategic consideration given to shaping the likely coverage?[6] One obvious precautionary measure would have been a preprint, but for reasons unknown to me, NIH did not do that. A second obvious precautionary measure would have been to have the patient representative approve the press release. Ditto. Now let us turn to methodology.

The Problematic Methodology

First, I will look at issues with Table 2, which presents the key twelve-point checklist, and names the algorithm (although without explaining it). After that, I will branch out to a few larger issues. Again I issue a caveat that I’m not a Long Covid maven or a statistics maven, and I hope readers will correct and clarify where needed.

Here is Table 2:

First, some copy editing trifles (highlighted). On “PASC”: As WebMD says: “You might know this as ‘long COVID.’ Experts have coined a new term for it: post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).” Those lovable scamps, always inventing impenetrable jargon! (Bourdieu would chuckle at this.) On “Dizzines”: Come on. A serious journal doesn’t let a typo like that slip through (maybe they’re accustomed to fixing the preprints?). On “Supplement 3”: The text is highlighted as a link, but clicking it brings up the image, and doesn’t take you to the Supplement. These small errors are important[7], because they indicate that no editor took more than a cursory look at the most important table in the paper. On “LASSO,” hold that thought.

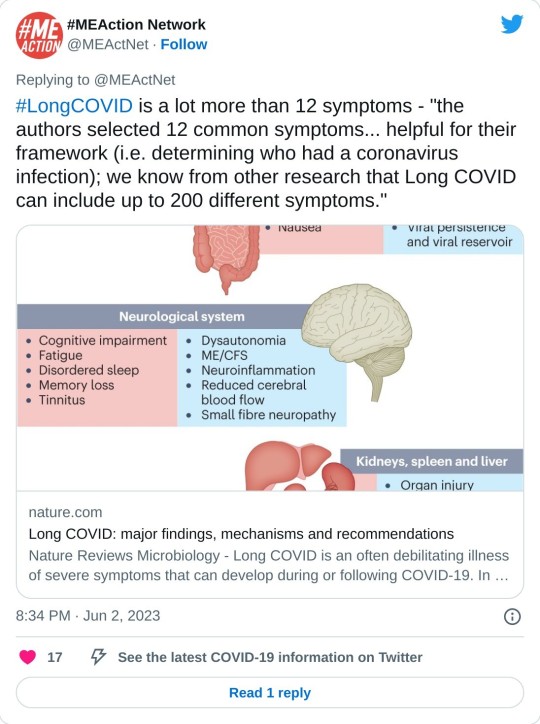

Second, the Covid Action Network points out that some obvious, and serious, symptoms are missing from the list:

[T]he next attempts at diagnostic criteria should take into account existing literature that shows more specifically defined symptoms for Long Covid, from objective findings. (E.g. PoTS, Vestibular issues, migraine, vs more vague symptoms like “headache” or “dizziness.) [The Long Covid Action Project (LCAP)] noticed that while [Post-Extertional Malaise (PEM)] was used as a specific symptom with a high score to produce PASC-positive results, other suites of symptoms, like those in the neurologic category, could have produced an equal or higher score than PEM if questionnaires had not separated neuro-symptoms into multiple subtypes and reduced their total scores. This alone could have created a more scientifically accurate picture of the Long Covid population.

Third, these symptoms — missing, from the patient perspective; to be iterated from the researcher’s perspective, at least one would hope — are the result of “Definition”‘s methodology:

Fourth, I would argue focus on the “most clearly provable effects” — as opposed to organ damage — is a result of the “LASSO” algorithm named in Table 2. I did a good deal of searching on LASSO, and discovered that most of the examples I could find, even the “real world” ones, were examples of how to run LASSO programs, as opposed to selecting the LASSO algorithm as opposed to others. So that was discouraging. I believe — reinforcing the caveats, plural, given above — that I literally searched on “LASSO” “child of five” (“Explain it to me like I’m five”) to finally come up with this:

Lasso Regression is an essential variable selection technique for eliminating unnecessary variables from your model.

This method can be highly advantageous when some variables do not contribute any variance (predictability) to the model. Lasso Regression will automatically set their coefficients to zero in situations like this, excluding them from the analysis. For example, let’s say you have a skiing dataset and are building a model to see how fast someone goes down the mountain. This dataset has a variable referencing the user’s ability to make basketball shots. This obviously does not contribute any variance to the model – Lasso Regression will quickly identify this and eliminate these variables.

Since variables are being eliminated with Lasso Regression, the model becomes more interpretable and less complex.

Even more important than the model’s complexity is the shrinking of the subspace of your dataset. Since we eliminate these variables, our dataset shrinks in size (dimensionality). This is insanely advantageous for most machine learning models and has been shown to increase model accuracy in things like linear regression and least squares.

Since LC is said to have over 200 candidates for symptoms, you can see why a scientist trying to get their arms around the problem would be very happy to shrink those candidates to 12. But is that true to the disease?

Because LASSO (caveats, caveats) has one problem. From the same source:

One crucial aspect to consider is that Lasso Regression does not handle multicollinearity well. Multicollinearity occurs when two or more highly correlated predictor variables make it difficult to determine their individual contributions to the model.

Amplifying:

Lasso can be sensitive to multicollinearity, which is when two or more predictors are highly correlated. In this case, Lasso may select one of the correlated predictors and exclude the other [“set their coefficients to zero”], even if both are important for predicting the target variable.

As Ted Nelson wrote, “Everything is deeply intertwingled” (i.e., multicollinear), and if there’s one thing we know about LC, it’s that it’s a disease of the whole body taken as a system, and not of a single organ:

There are some who seek to downplay Long Covid by saying the list of 200 possible symptoms makes it impossible to accurately diagnose and that it could be encompassing illnesses people might have gone on to develop anyway, but there are sound biological reasons for this condition to affect the body in so many different ways.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor 2 (ACE2) is the socket SARS-CoV-2 plugs into to infect human cells. The virus can use other mechanisms to enter cells=, but ACE2 is the most common method. ACE2 is widely expressed in the human body, with highest levels of expression in small intestine, testis, kidneys, heart, thyroid, and adipose (fat) tissue, but it is found almost everywhere, including the blood, spleen, bone marrow, brain, blood vessels, muscle, lungs, colon, liver, bladder, and adrenal gland

Given how common the ACE2 receptor is, it is unsurprising SARS-CoV-2 can cause a very wide range of symptoms.

In other words, multicollinearity everywhere. Not basketball players vs. skiiers at all.

So is LASSO even the right algorithm to handle entwinglement, like ACE2 receptors in every organ? Are there statistics mavens in the readership who can clarify? With that, I will leave the shaky ground of statistics and Table II, and raise two other issues.

First, it’s clear that the population selected for “Definitions” is unrepresentative of the LC population as a whole:

If the patients in “Definition” are not so ill, that might also account for Table 2’s missing symptoms.

Second, “Definition”‘s questionnaires should include measures of severity, and don’t:

Conclusion

The Long Covid Action Project (materials here) is running a letter writing campaign: “Request for NIH to Retract RECOVER Study Regarding 12 Symptom PASC Score For Long Covid.” As of this writing, “only 3,082 more until our goal of 25,600.” You might consider dropping them a line.

Back to the checklist for one moment. One way to look at the checklist is — we’re talking [drumroll] the PMC here — as a set of complex eligibility requirements, whose function is, as usual, gatekeeping and denial:

what they did is create basically a means test to figure out a dx but for smthg that is still not fully understood. it's premature and rly limited, & this will only further aid ppl already dismissive of lc

— Wendi Muse (@MuseWendi) June 3, 2023

If you score 12, HappyVille! If you score 11, Pain City! And no consideration given to the actual organ damage in your body. And after the last three years following CDC, I find it really, really difficult to give NIH the benefit of the doubt. If one believed that NIH was acting in bad faith, one would see “Definition” as a way to keep the funding gravy train rolling, and the “12 Symptoms” headlines as having the immediate and happy outcome of denying care to the unfit. Stay safe out there, and let’s save some lives!

NOTES

[1] Oddly, the JAMA paper is not yet listed on RECOVER’s publications page.

[2] “12” is such a clickbait-worthy brainworm. “12 Days of Christmas,” “12 apostles,” “12 steps,” “12 months,” “12 signs of the zodiac,” etc. One might wonder where if the number had been “9” or “14” the uptake would have been so instant.

[3] To be fair to the sources, most of them mention this: Not CBS, Chief Health Care Executive, or the Daily Beast, but CNN in paragraph 51, Smithsonian (9), PBS (20), AMA Update (10), and Benefits Pro (17).

[4] There was only one patient representative for the paper:

One seems low, especially given the headcount for the project.

[5] I was not able to find a nursing journal that covered the story.

[6] Unless it was, of course.

[7] Samuel Johnson: “When I take up the end of a web, and find it packthread, I do not expect, by looking further, to find embroidery.”

#long covid#naked capitalism#lambert strether#national institutes of health#covid pandemic#covid 19#long covid action project#long covid awareness day

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), often referred to as Long COVID, has had a substantial and growing impact on the global population. Recent prevalence studies from the United States and the United Kingdom found that the complication has affected, on average, around 45 percent of survivors, regardless of hospitalization status.

No accurate tally of the number of people affected and its real global impact has yet been made, but conservative estimates of several hundred million and trillions in economic devastation would hardly be an exaggeration. Even in China, after the lifting of the Zero COVID policy late last fall and the tsunami of infections that followed, social media threads are now widespread with people complaining of chronic debilitating fatigue, heart palpitations and brain fog.

Yet, more than three years into the “forever” COVID pandemic, with Long COVID producing more than 200 symptoms, impacting nearly every organ system and causing such vast health problems for a significant population across the globe, it remains undefined and somewhat arbitrary in the clinical diagnosis. Additionally, the assurances given to study potential therapeutic agents have remained unfulfilled.

In this regard, a new Long COVID observational study called the “RECOVER [researching COVID to enhance recovery] initiative,” was published last week in the Journal of the American Medical Association, with almost 10,000 participants across the US. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), it attempts to provide a working definition for Long COVID (PASC).

While the study represents an advance from the standpoint of assessing the impact of Long COVID, and has been celebrated in media coverage, it must be viewed with several reservations and caveats. It is exclusively focused on describing the disease, rather than supporting efforts to alleviate its impact, let alone find a cure. And its definition, however preliminary, could well be misused by insurance companies and other profit-driven entities in the healthcare system to restrict diagnosis and care.

Comments by Dr. Leora Horwitz, one of the study authors and director of the Center for Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science at New York University, give some sense of the misgivings felt by serious scientists. Horwitz stated, “This study is an important step toward defining Long COVID beyond any one individual symptom. This definition—which may evolve over time—will serve as a critical foundation for scientific discovery and treatment design.”

Certainly, a working definition that medical communities can agree on is critical. But after three years and nearly all the $1.2 billion given to the NIH already spent, one must ask how much another observational study contributes to answering pressing questions affecting patients that have not already been addressed in more than 13,000 previous reports, as tallied by the LitCOVID search engine?

Why have there been so many delays in conducting clinical trials studying potential treatments and preventative strategies in the acute phase of infection that could reduce or eliminate the post-acute sequelae? Where is the urgency at the NIH and in the Biden administration to expand funding and initiate an all-out drive to develop treatments for Long COVID like the $12.4 billion spent on the COVID vaccines?

Scoring post-acute symptoms

The findings in the recent study, published on May 25, 2023, in JAMA, titled, “Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” are somewhat limited and problematic in their current formulation. The authors have identified 12 primary symptoms that distinguish COVID survivors with Long COVID from those without those aftereffects. These include loss of smell or taste (8 points), post-exertional malaise (7 points), chronic cough (4 points), brain fog (3 points), thirst, (3 points), heart palpitations (2 points), chest pain (2 points), fatigue (1 point), dizziness (1 point), gastrointestinal symptoms (1 point), issues with sexual desire or capacity (1 point), and abnormal movements (1 point).

Assigning points to each of the 12 symptoms and adding them up gives a cumulative total for each patient. Anyone scoring 12 or higher would be diagnosed as afflicted with PASC, accounting for 23 percent of the total. In general, the higher the score, the greater the disability in performing daily activities.

The researchers also noted that certain symptom combinations occurred at higher rates in certain groups, leading to identifying four clusters of Long COVID based on symptomology patterns, ranging from least severe to most severe in terms of impact on quality of life. Why such clusters were seen remains uncertain.

Some symptoms were more common than others, and this did not correspond to the severity of the symptoms as measured approximately by the points. Symptoms of post-exertional malaise (87 percent), brain fog (64 percent), palpitations (57 percent), fatigue (85 percent), dizziness (62 percent), and gastrointestinal disturbances (59 percent) were most common.

The study’s lead author, Tanayott Thaweethai from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, explained, “This offers a unifying framework for thinking about Long COVID, and it gives us a quantitative score we can use to understand whether people get better or worse over time.”

Andrea Foulkes, the corresponding author and principal investigator of the RECOVER Data Resource Core and professor at Harvard Medical School, said, “Now that we’re able to identify people with Long COVID, we can begin doing more in-depth studies to understand the mechanisms at play. These findings set the stage for identifying effective treatment strategies for people with Long COVID—understanding the biological underpinnings is going to be critical to that endeavor.”

The currently evolving definition could have significant implications, and not just medically. For instance, if people suffer only brain fog and post-exertional malaise and score less than 12 on their symptomology, they would not be construed as having PASC. Under such a construct, the definition could be used by employers and health insurers to deny compensation or treatment by telling people they don’t have a recognized Long COVID complication. Additionally, it is not clear how long these symptoms have to be present before the diagnosis is accepted.

Lisa McCorkell, one of the authors of the study, explained on her social media account, “If people didn’t meet the scoring threshold for PASC+, that doesn’t mean they don’t have PASC! It means they are unspecified. Unspecified includes people with Long COVID. Future iterations of the model will aim to refine this—that will include doing analysis using the updated RECOVER symptoms survey, adding in tests/clinical features and ultimately biomarkers. That is also why this isn’t meant to be an official prevalence study. The sample is not fully representative, but also, we know that there are people in the unspecified groups that have PASC.”

She continued, “It is very clear throughout the paper that in order for this to be actionable at all, iterative refinement is needed. In presenting this to NIH leadership, they are fully aware of that. But the press is not fully understanding the paper which could have dangerous downstream effects. Since the beginning of working on this paper I’ve done everything I could to ensure the model presented in this paper is not used clinically.”

Unfortunately, in the world of capitalism, such things take on a life of their own. The definitions will influence how health systems will choose to view these patients and demand their clinicians abide by prescribed diagnostic codes. This has the potential to dismiss millions with Long COVID symptoms and deny them access to potential treatments if and when they materialize.

The concerns of Elisa Perego

Dr. Elisa Perego, who suffers from Long COVID and coined the term, offered the following important observations.

In response to the publication, she wrote, “Presenting a salad of 12 symptoms, (many of which many patients might not even experience) as the most significant in #LongCOVID is also detrimental to new patients, who might be joining the community now, and might not recognize themselves in the symptom list.”

She added, “We are also in 2023. There are thousands and thousands of publications from across the world that discuss imaging, tests, clinical signs (=objective measurements), biomarkers, etc. related to acute and #LongCOVID. We have many insights into the pathophysiology already. The #LongCOVID and chronic illness community deserve more. Other diseases, including diseases linked to infections, have sadly been reduced to a checklist of symptoms in the past. This has made research, recognition, and a quest for treatment much more difficult.”

There are additional findings in the report worth underscoring as they provide a glimpse into the ever-growing crisis caused by forcing the world’s population to “live with the virus.”

Hannah Davis, a Long COVID advocate and researcher, with Dr. Eric Topol, Lisa McCorkell, and Julia Moore Vogel, wrote an important review on Long COVID in March, which was published in Nature. She said of the RECOVER study, “The overall prevalence of #LongCOVID is ten percent at six months. The prevalence for those who got Omicron (or later) AND were vaccinated is also ten percent … [However] reinfections had significantly higher levels of #LongCOVID. Even in those who had Omicron (or later) as their first infection, 9.7 percent with those infected once, but 20 percent of those who were reinfected had Long COVID at six months after infection.”

Furthermore, she said, “Reinfections also increased the severity of #LongCOVID. Twenty-seven percent of first infections were in cluster four (worst) versus 31 percent of reinfections.” These facts have considerable implications.

Immunologist and COVID advocate Dr. Anthony Leonardi wrote on these findings, “If Omicron reinfections average six months [based on current global patterns of infection], and Long COVID rates for reinfection remain 10 to 20 percent, the rate of long COVID in the USA per lifetime will be over 99.9 percent. In fact, the average person would have different manifestations of Long COVID at different times many times over. Some things reverse—like anosmia [loss of smell]. Others, like [lung] fibrosis don’t reverse so well.”

The work done by these authors deserves credit and support. Every effort to bring answers to these critical questions is vital. The criticism to be made is not directed at the researchers who work diligently putting in overtime to see the research is conducted with the utmost care and obligation it merits. Rather, it should be directed at the very institutions that have adopted “living with the virus” as a positive good for of public health.

The Biden administration neglects Long COVID

In a recent scathing critique of the Biden administration and the NIH by STAT News, Rachel Cohrs and Betsy Ladyzhets place the issue front and center. In their opening remarks, they write, “The federal government has burned through more than $1 billion to study Long COVID, an effort to help the millions of Americans who experience brain fog, fatigue, and other symptoms after recovering from a coronavirus infection. There’s basically nothing to show for it.”

They continue, “The NIH hasn’t signed up a single patient to test any potential treatments—despite a clear mandate from Congress to study them. And the few trials it is planning have already drawn a firestorm of criticism, especially one intervention that experts and advocates say may actually make some patients’ Long COVID symptoms worse.” This is in reference to a planned study where Long COVID patients would be asked to exercise as much as possible, when it has clearly been shown that such activities have exacerbated the symptoms of Long COVID patients.

As the report in STAT News explains, there has been a complete lack of accountability in how the NIH funds were used. Much of the work to run the RECOVER trial has been outsourced to major universities.

Michael Sieverts, a member of the Long COVID Patient-led Research Collaborative with expertise in federal budgeting for scientific research, told STAT, “Many of the research projects associated with RECOVER have been funded through these organizations rather than directly from the NIH. This process makes it hard to track how decisions are made or how money is spent through public databases.”

In April the Biden administration announced they were launching “Project Next Gen,” which is like the Trump-era COVID vaccine “Warp Speed Operation.” It has promised $5 billion to fund the development of the next iteration of vaccines through partnership with private-sector companies, monies freed up from prior coronavirus aid packages. Incredibly, it has left Long COVID out of the plan.

Indeed, this diverting of money back into the hands of the pharmaceuticals and selling it as the Biden administration’s continued proactive response to the ongoing pandemic, while divesting all interest in preventing or curing Long COVID, is on par with every effort the administration has made to peddle the myth that “the pandemic is really over.” Long COVID is one of the central elements of the worst public health threat in a century, in a pandemic that is far from ended.

2 notes

·

View notes