#Decatur Public Library

Text

A trend I would like to see more of.

youtube

One of Decatur’s best-kept secrets is getting more exposure. Friends of The Decatur Public Library is replacing its annual book sale with a bookstore with regular hours.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louisville Seminary is one of 10 theological schools of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). In addition, the United Methodist denomination officially recognizes the Seminary as an appropriate school for its candidates to receive their theological education. Louisville Seminary warmly welcomes individuals from the wider ecumenical community as well.

The four degrees for which Louisville Seminary is accredited are:

Master of Divinity (MDiv) (CIP 390602)

Master of Arts in Religion (MAR) (CIP 390601)

Master of Arts in Marriage and Family Therapy (MAMFT) (CIP 51.1505)

Doctor of Ministry (DMin) (CIP 390602)

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) to award master's and doctoral degrees. Questions about the accreditation of Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary may be directed in writing to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, GA 30033-4097, by calling 404-679-4500, or by using information available on SACSCOC's website.

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary was last reaffirmed in 2020 and is scheduled for reaffirmation in 2030.

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary is accredited by the Commission on Accrediting of The Association of Theological Schools (ATS) and is approved to offer the following degrees: MDiv, MAR, MAMFT, and DMin.

The Marriage and Family Therapy Program at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Marriage and Family Therapy Education (COAMFTE) of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT), 1133 15th Street, NW, Suite 300, Washington, D.C. 20005-2710, 202.452.0109.

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary is also approved by the University Senate of the United Methodist Church.

Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary is licensed by the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education (CPE) as a non-public postsecondary institution. For information on making a consumer complaint through CPE, visit this web site.

#Theological Studies#Seminary#Religious Schools#Professional Masters Programs#Licensed Marriage and Family Therapy

0 notes

Photo

The Decatur Arts Alliance invites international artists of all mediums to apply for the 11th edition of the juried exhibition of The Book as Art, which will be installed in the newly renovated 4th floor gallery at the Decatur Branch of the DeKalb County Public Library, home to the Georgia Center for the Book. Enter by June 11th. For more details, click the link in our bio. ... #art #artist #artwork #callforartists #artcall #book #myth #magic #library #decatur #georgia #prize #award @decatur_arts_alliance https://buff.ly/3IBsU5I — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/hztkpdM

0 notes

Text

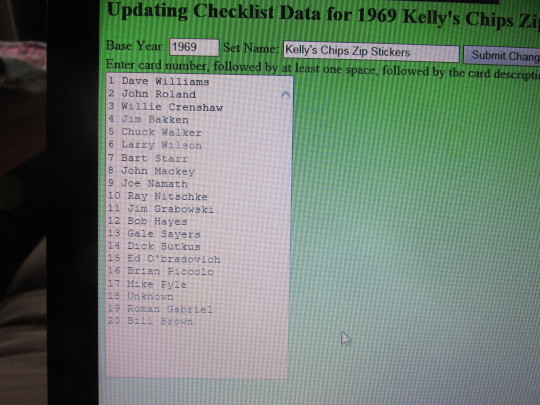

Zip Chips

I received a test message from one of my followers, Wayne Genteman, of Central Wisconsin. Wayne was a prolific collector of football cards, but now concentrates on Zip Stickers. These stickers were issued by Kelly Potato Chip Company of Decatur, Illinois in 1969 and featured stars of the teams in Kelly's distribution area, the St. Louis Cardinal, Chicago Bears and Green Bay Packers in addition to such national stars as Joe Namath.

They were placed in potato chip bags of Kelly's with one major mistake. The stickers were not placed in cellophane and therefore many of them had oil or grease stains. They were done in two to three colors. All have distinct cuts and many are smudged. They were named zip stickers since they contained Kelly's motto "Chip with Zip."

The series contains 20 stickers and Wayne and a few of his friends are in competition to collect all 20 of them. Wayne has 17 of the 20 and is missing #5 Chuck Walker, #17 Mike Pyle and #18. Nobody is sure who was on card number 18, although Wayne suspects it may have been a Chicago Bear. Please contact me at TogaChipGuy.com if you know the whereabouts of either of the two missing named crds of the unknown # 18.

A collector's web-site describes the Namath sticker as follows:

Talk about your rare Regional, in 1969 the Kelly`s Potato Chip Co. located in Decatur, Illinois issued a 20 card set of prominent Pro-Football players. Only a handful of these cards are in the hobby today. The cards were included in specially marked bags of chips. A personalized hand autographed full color action picture of one of the players could be obtained by redeeming the complete set of cards. This has got to be one of the rarest "Broadway Joe" cards around!

The Kelly potato chip bags contained Major League Baseball player pins in the summer. These pins were similar to those distributed by both the Sunoco and Citco gasoline companies.

Wayne has provided the attached photos of the checklist of the 20 stickers. Again #18 is unknown. He has also provided photos of the 17 stickers he has. Finally, see the article by Michael Blaisdell, one of Wayne's friendly competitors, on the zip stickers.

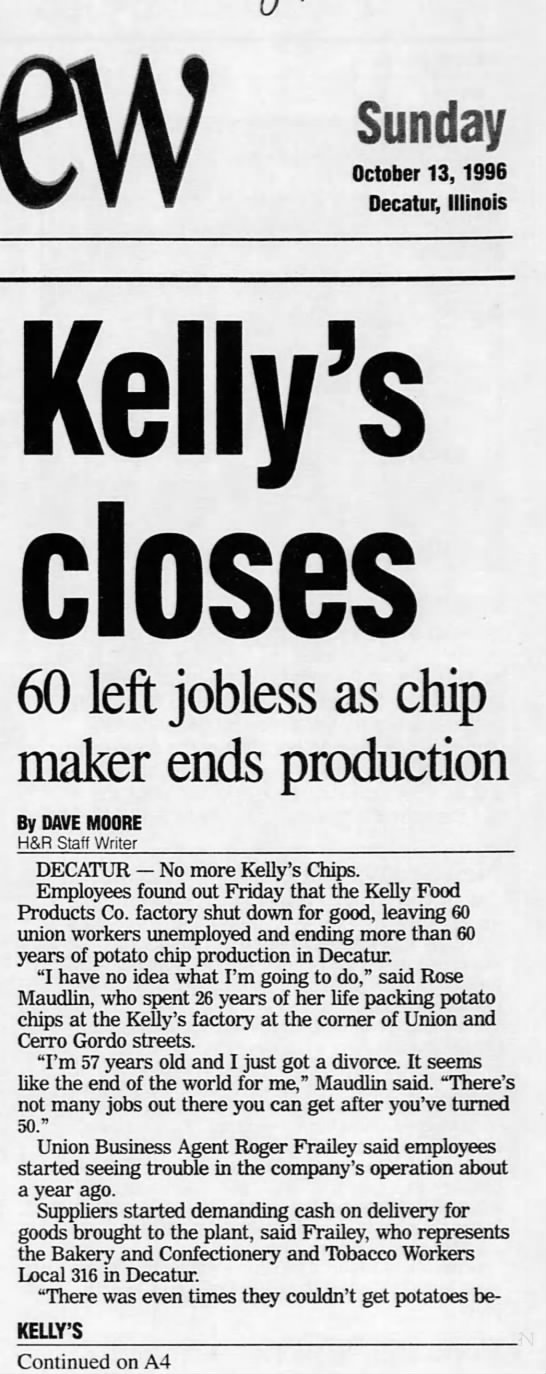

A good history of Kelly's is set forth in the attached article from the October 13, 1996 edition of the Herald and Review (Decatur, Il).

Kelly Food Products Co. factory shut down for good in 1996 after employees had started to see trouble in the company's operation about a year before.Most of the product line was sold to Seyfert foods of Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Special thanks to Rebecca Damptz, Archivist of the Local History Department of the Decatur Public Library for providing a copy of the table top display that was included at the Decatur Public Library. It includes Kelly's, Perfect, and Crane companies. Rebecca has also provided the attached photos from their collection and a book called Decatur Business: A Pictorial History by Karen Anderson and Dayle Cochran Merideth (1995) pgs.144-145. I've also included photos from Perfect Potato Chip.

0 notes

Text

Jarrett Krosoczka Events!

Tues., 4/18: Public event at the Academy of Music in Northampton, MA (books sold by High Five Books) // Event Listing

Thurs., 4/20: Public event at Austin Scottish Rite Theater in Austin, TX (books sold by BookPeople) // Event Listing

Fri., 4/21: Public event at St. Charles City-County Library, Spencer Road Branch in St. Louis, MO (books sold by The Novel Neighbor) // Event Listing

Sat., 4/22: Public event at the Decatur Library in Decatur, GA (book sales by Little Shop of Stories) // Event Listing

Sun., 4/23: Public event with Politics & Prose in Washington, D.C. // Event Listing TK

Mon., 4/24: Public event at Penncrest High School in Media, PA (books sold by Children’s Book World) // Event Listing

Blaze

0 notes

0 notes

Text

Jarrett Krosoczka Events!

Tues., 4/18: Public event at the Academy of Music in Northampton, MA (books sold by High Five Books) // Event Listing

Thurs., 4/20: Public event at Austin Scottish Rite Theater in Austin, TX (books sold by BookPeople) // Event Listing

Fri., 4/21: Public event at St. Charles City-County Library, Spencer Road Branch in St. Louis, MO (books sold by The Novel Neighbor) // Event Listing

Sat., 4/22: Public event at the Decatur Library in Decatur, GA (book sales by Little Shop of Stories) // Event Listing

Sun., 4/23: Public event with Politics & Prose in Washington, D.C. // Event Listing TK

Mon., 4/24: Public event at Penncrest High School in Media, PA (books sold by Children’s Book World) // Event Listing

0 notes

Text

Openbox v8s gift

Linux Operating System 1.6GHz Quad Core 64 bit CPU Hi3798MV200 High-Performance Muilt-Core Mail 450 CPU Support 4K/60FPS HDR,Full HD 1080P,HDMI576i,576p,720p,1080i,1080p Up to 3840* ,10bit,HDR 10 Support DVB-S2X+DVB-T2/TC combo Tuner Built-in 8GB EMMC 1GB DDR3 RAM Memory 2.4G WiFi Support 1xCA Smart Card 1x USB3.0 1xUSB2.0 1xHDMI2.0 1xAV MPEG-2/ H.264andH.265 Hardware Decoding HEVC /H. CCCAMSERVER4u Free Cline, cccam 2017, openbox v8s, openatv 5.1 cccam, cccam prio 2016 ,cccamserver, cccam, cccam server gratuit, free server cccam ,free cccam. Image-in-picture function as 4K UHD and of course the E2 Linux operating system. Other main features include HDR/HDR10 support,transcoding,multiboot function,IPTV support, 1PC Applicable SKYBOX F3 V8 M3 M3S, OPENBOX V8S V8SE V6S,S-V8,SOLOVOX V8S PLUS F7S F6S F5SPLUS,models original F3 remote control. CHANNEL LIST UPDATE OPENBOX V5S&V8S NOVEMBER 2021 MOST POPULAR&BEST ON EBAY. Get it Tuesday, Nov 16 - Saturday, Nov 20. RM Series Replacement Remote Control for Openbox V8S. Details: months, gift, openbox, skybox, receiver, watch, polish, portugues, spanish, connect. Skybox V8S receiver to watch Polish Portugus dyson corrale hair straightener gift edition brand new open box item. OpenBox V8S DVB-S2 CCcam NEWcam MGcam TV Receiver With Web TV. Tv Portuguesa Openbox V8S With 12 Months Gift, us. You can install different user interfaces or plugins and settings. ( 1 Year Gift ) Original Openbox V8S Plus DVB-S2 Digital Satellite Receiver S-V8 WEBTV Biss Key 2x USB Slot USB Wifi 3G. 12 Months Full Gift for Openbox V8s F5 F3 Zgemma Vu - Warranty. vexson Wifi USB Adapter for Openbox V8s Mag VU+ DreamBox Zgemma Star. You can choose between satellite TV (DVB-S2X), cable TV (DVB-C) or DVB-T2 reception. In addition to the OPENATV operating system, the main feature is the multi-tuner, with which Verwandte Suchanfragen polska telewizja pl tv dekoder openbox v8s 12 miesiecy gift: 12 MONTH SLY GIFT WARRANTY OPENBOX V5S V8S SKYBOX V5S V8S 12 MONTH GIFT WARRANTY OPENBOX V5S V8S SKYBOX V5S V8S 1Caractéristiques de lobjet État : Neuf: Objet neuf et intact, nayant jamais servi, non ouvert, vendu dans son emballage dorigine (lorsquil y en a un). Provides super fast switching times and a buttery soft user interface. 8+ Openbox Gift V8s deals & offers in the UK from 3.79 November 2021 Save UP to 25 in Openbox Gift V8s Dealsan help you find the cheap price.

Best Buy's 'Top Deals' discounts TVs, laptops, PCs and more - MobileSyrup MobileSyrupFingbox: Family Wireless Network Security - GeekDad GeekDadThe Best Cyber Monday Deals of 2020: Apple, Dyson, Patagonia More - gearpatro_ gearpatro_5 questions with Jessica Hill, community resource coordinator at the Decatur Public Library - Herald Review Herald ReviewDid Smith accidentally spill Storm secret? - NEW_.au NEW_.auBest cheap kids tablet deals for October 2021 - Digital Trends Digital TrendsThe 18 best kitchen, home decor, and furniture deals you can get this weekend - USA TODAY USA TODAYThe best deals and sales on everything for your home this week - USA TODAY USA TODAYSpeak Out: For Those Of Us With 'Points', Instead Of CPU-Ignitions.☺! - Southeast Missourian Southeast MissourianBlackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve Studio License Key, Includes Free Speed Editor DV/RESSTUD - Adorama AdoramaHow Many Parts In A Triumph Herald Heater? - Hackaday HackadayPorsche Owners Are Jerks.The HiTube 4K UHD Combo Sat Receiver is a real all-rounder.Īt the heart is the 15,000 DMIPS (4x 1.6 GHz) strong ARM HI3798MV200 Quad Core processor.

0 notes

Audio

Our newest episode of Dewey Like Murder? is available for streaming and download! We talk about The Demon Next Door by Bryan Burrough & Seduced by Madness by Carol Pogash! Check it out! (Decatur Public Library TX)

#SoundCloud#music#Decatur Public Library TX#Demon Next Door#Bryan Burrough#Seduced by Madness#Carol Pogash

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

View of commercial buildings on an unidentified street in Decatur, Michigan. Horse-drawn wagons in foreground. Printed on front: "The Gay Nineties, Decatur, Mich., 1893."

Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

#the gay nineties#decatur#michigan#michigan history#1893#19th century#gay nineties#decatur michigan#vintage#postcard#postcards#vintage postcards#detroit public library

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

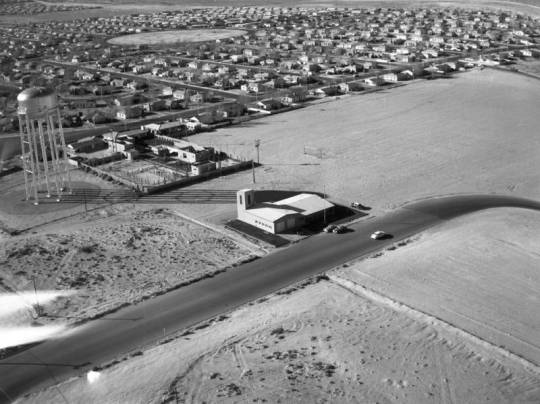

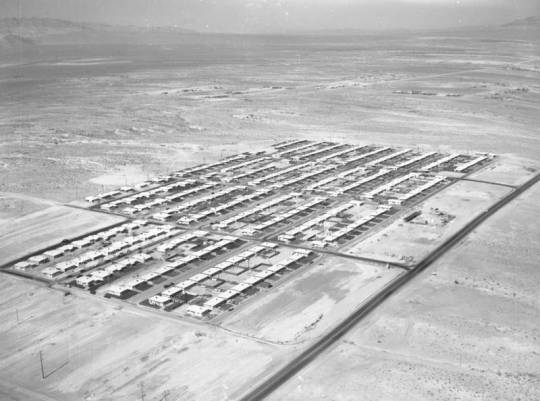

Las Vegas aerials, February 19, 1959

Photos by Howard Kelly and George Holiday for Pioneer Flintkote, Kelly-Holiday Mid-Century Aerial Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

(1) Southern Nevada Memorial Hospital, est. ‘31 as Clark County Hospital, and today known as UMC. Charleston Blvd at Rancho Lane, Pahor Dr and Westwood Dr.

(2-4) Hyde Park (developed in ‘52) - Hyde Park Middle School, Fire station at 1020 Hinton & W Charleston, SW corner of Decatur Blvd & Lorna Pl.

(5) Las Vegas Square (developed late 50s) near N Decatur Blvd.

(6) Twin Lakes Elementary School (‘55), Twin Lakes Village.

(7) Marble Manor (developed ‘52). J St. & W McWilliams Ave in the foreground.

(8) Lincoln Elementary (opened ‘56, demo'ed 2017), E Brooks Ave & Berg St, North Las Vegas.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON NOVEMBER 3, 1979, a caravan of neo-Nazis and Klansmen fired upon a communist-organized “Death to the Klan” rally at a black housing project in Greensboro, North Carolina. Five protestors died—four white men and one black woman—and many more were injured. Fourteen Klansmen and neo-Nazis faced murder, conspiracy, and felony riot charges. Although three news cameras captured the identity and actions of the Klan and neo-Nazi shooters, all-white juries acquitted the defendants in state and federal criminal trials. A civil suit returned only partial justice. The Greensboro confrontation heralded a paramilitary white power movement mobilized for violence, and also revealed a legal system broadly unprepared to convict its perpetrators.1

The shooting at the Greensboro rally was the logical extension of post–Vietnam War paramilitary culture and a series of increasingly violent clashes between the fractious radical left and the nascent white power movement. Sharing a common story of the Vietnam War, disparate Klan and neo-Nazi factions united around white supremacy and anticommunism, and sustained the groundswell by circulating and sharing images, personnel, weapons, and money. In 1979, North Carolina Klansmen had recently discovered a new leader in David Duke. His Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKKK), gaining momentum nationwide, had just secured a local foothold in an area with a long tradition of Klan activity and with other active Klan factions. In February, Duke himself came to Winston-Salem to screen Birth of a Nation. The 1915 film depicts Klansmen as heroically saving the South—embodied by white women threatened by interracial sex—from the ravages of blacks and northern carpetbaggers during Reconstruction.2

While neither the post–Vietnam War KKKK nor the white power movement was primarily southern, the film’s invocation of the lost Civil War had particular resonance in North Carolina. For the South, the Vietnam War was not the only American defeat at play in the popular imagination, nor the only war that needed to be reengaged. Indeed, one illustration published in the Alabama-based KKKK newspaper White Patriot portrayed a Confederate veteran standing in formation with a Vietnam War–era Green Beret and a third man wearing a Klan hood.3 At the time of Duke’s visit in 1979, the KKKK showed signs of a southern membership surge as well as openness to new alliances: people wearing Nazi armbands, for instance, attended an exhibit of Klan artifacts at a county library in Winston-Salem.4

At the same moment, an attack waged by Invisible Empire Knights of the Ku Klux Klan upon black civil rights marchers in Decatur, Alabama, modeled a Klan strategy of forming armed caravans to carry out violence.5 The Decatur altercation wounded four black demonstrators and resulted in a local ordinance prohibiting guns within 1,000 feet of public demonstrations. The Invisible Empire responded by driving a caravan of vehicles past the mayor’s house: “If You Want Our Guns, Come and Get Them,” one sign read. The local police chief made no arrests, unsure if the ordinance applied to a moving caravan of cars. The Invisible Empire, helmed by Bill Wilkinson, famously didn’t get along with several other Klan factions. Nevertheless, an increasing circulation of newspapers and other printed ephemera had begun to link these groups, and articles about the Decatur clash appeared in Klan and neo-Nazi publications as well as in the mainstream press. The incident foreshadowed the caravan of Klansmen and neo-Nazis that would gun down protestors in Greensboro months later.6

In July 1979, local members of the Federated Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party arranged another screening of Birth of a Nation. This time they chose a community center in the small, working-class town of China Grove, North Carolina, about sixty miles from Greensboro.7 Members of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO)—which soon changed its name to the Communist Workers Party (CWP)—organized a rally and march in protest. A hundred self-proclaimed communists as well as black community members stormed the community center, armed with clubs. While Klansmen and Nazis stood on the porch with shotguns, a few policemen managed to keep the groups from attacking each other. The Klansmen retreated into the building as protestors damaged the structure and burned a Confederate flag.8

The scene was remarkably similar to the final sequence in Birth of a Nation, in which the southern family hides in a small cabin as the town is, as the intertitles say, “given over to crazed negroes … brought in to overawe the whites.” As the “black mob” and the carpetbaggers wreak havoc in town, tarring and feathering Klan sympathizers and attempting to force an interracial marriage, those in the cabin are trapped, hopelessly besieged, until a large cadre of robed Klansmen rescues them, accompanied by the strains of Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.”9

No such rescue party appeared in China Grove. Klansmen experienced the protest as a direct attack. The women huddled in the bathrooms as the men defended the building, vowing revenge. Several Klansmen would later study photographs of the China Grove demonstrators to choose whom to “beat up” in Greensboro on November 3. In the moments before the fatal shooting, a news camera would capture neo-Nazi Milano Caudle murmuring “China Grove” as he drove past the demonstrators, evoking that earlier clash just before the shooting began.10

The CWP, on the other hand, saw China Grove as a success. A Maoist Communist group that advocated political violence, the CWP was largely composed of young, earnest white and Jewish outsiders, many from New York. Several had left jobs as doctors at Duke Hospital to unionize textile factory workers in nearby Greensboro, choosing the town because of its low unionization and the persistent problem of brown lung disease acquired from inhaling cotton fibers. The group also included black activists long involved with the local civil rights movement. While the WVO / CWP claimed a long alliance with the black community in Greensboro, it was a complicated relationship characterized by misunderstanding. Black residents would later express their frustration that the CWP had turned their neighborhood into a site of confrontation without their consent. WVO / CWP leaders claimed China Grove as a victory, ignoring the fears of future violence the confrontation had raised for many group and community members. Following several other Maoist and radical left groups nationwide, the CWP took the official position that organizing against the Klan required aggressive confrontation. They mobilized against what they called a southern Klan resurgence, and against the impact such a movement might have on unionizing and racial cooperation.11

The Klan was, indeed, in the midst of a major membership surge. According to watchdogs, the Klan had been 6,500 strong in 1975 but by 1979 had increased to 10,000 active members plus an additional 75,000 active sympathizers. Duke, at the peak of his popularity on the talk-show circuit, boasted that the KKKK had doubled its membership between March 1978 and March 1979. A Gallup poll, furthermore, showed that the number of people with favorable opinions of the Klan rose from 6 percent in 1965 to 11 percent in 1979.12

While the local community and national press perceived people on both sides of the Greensboro confrontation as dangerous and violent extremists, they also remained deeply engaged in the anticommunism of the Cold War. The Greensboro community, including local media, saw the Klansmen as local boys defending the status quo and the communists as anarchist outsiders who came to town to make trouble. The communists, with their openly revolutionary agenda, were understood as traitorous, radical, and dangerous in a way that Klansmen were not.

The Greensboro shooting was the culmination of almost two years of intense antagonism and repeated clashes between white power groups and the radical left. In July 1978, Tom Metzger, Grand Dragon of the KKKK in California, encountered left-wing opposition when the Maoist Progressive Labor Party (PLP) and Committee Against Racism (CAR) tried to forcibly prevent Metzger’s Klan from screening Birth of a Nation in an Oxnard, California, community center. According to the KKKK newspaper Crusader, the communists had come to the screening prepared for a fight: “PLP / CAR put over nine police in the hospital, swinging lead pipes rolled in Challenge newspapers.” The Los Angeles Times reported that forty leftist demonstrators had charged the community center, wielding clubs, bottles, and pipes. Police arrested thirteen demonstrators for incitement to riot, assaulting police officers, carrying concealed weapons, and refusing to disperse. Between 180 and 300 more demonstrators—characterized by local police as “mostly Mexican-Americans”—remained on the street, shouting “Death to the Klan, Death to the Klan!” One Klansman, blindsided by a protestor’s lead pipe, suffered a broken nose and lost teeth, according to police. Three law enforcement officers and four demonstrators also sustained serious injuries, and seven more policemen reported minor wounds.13

Similar incidents across the country showed rising tension between the left and the nascent white power movement. In August, leftists attacked neo-Nazi Michael Breda in Kansas City as he was giving a radio interview—twelve to fifteen men with clubs and pipes broke into the radio station and beat Breda and another member of his group, the American White People’s Party. Although the attack lasted less than a minute, Breda and two radio station employees suffered significant head and shoulder injuries. A member of the International Committee Against Racism and the Revolutionary Communists Progressive Labor Party—iterations of CAR and PLP—took credit for the beating. Breda told the Los Angeles Times that the same thing had happened during a Houston radio interview.14

The next summer, Klansmen gathered in Little Rock, Arkansas. They intended to stage a counterdemonstration to some 1,200 to 1,500 mostly black men and women protesting the rape conviction of a mentally disabled black man. The event stirred memories of the civil rights movement: Little Rock had seen some of its most tumultuous moments around the integration of the city’s Central High School in 1957, when federal troops were called in to keep order. As the Chicago Tribune reported of the 1979 march, “To preclude violence … state and city officials sent in extra men and firepower, including 230 state troopers, a full platoon of Alabama National Guardsmen, two armored personnel carriers, and police from surrounding communities armed with AR-15 semiautomatic rifles and pump-action shotguns.” This intense armament foreshadowed another burgeoning paramilitary culture in the escalating militarization of civilian policing.15

Two months later, some forty members of Metzger’s Klan met to discuss “illegal aliens and Vietnamese boat people and communists and other things” in Castro Valley, California. Thirty chanting and stone-throwing CAR members stormed the meeting to break it up. The Klan swiftly responded with a fifteen-man contingent armed with clubs and plywood shields, dubbed the “Klan Bureau of Investigation.” Sheriff’s deputies broke up the fight, which resulted in only one minor injury. The speed of the Klan response showed both an escalation from the Oxnard confrontation the previous year and the expansion of group activities throughout California. Although Metzger had militarized his operation as early as 1974 through the Klan Border Watch and other activities, the California KKKK was now regularly prepared for violent confrontation at public events.16

As violence came to the fore of the movement, distinctions among white power factions melted away. Klansmen and neo-Nazis set aside their differences, which had been articulated largely by World War II veterans with strong anti-Nazi feelings, as the Vietnam War became their dominant shared frame.17 White men prepared for a war against communists, blacks, and other enemies. As one Klansman said just after the China Grove altercation, “I see a war, actual combat, eventually between the left-wing element and the right wing.”18

Klansmen and neo-Nazis united against communism at the same moment that elements of the left fractured and collapsed under the pressure of internal divisions and government infiltration. In Greensboro, for instance, the CWP competed locally with the Revolutionary Communist Party and the Socialist Workers Party. The members of each group refused to speak to each other and more than once came to blows while attempting to unionize the same textile mill.19

In contrast, white power activists bound by paramilitarism also developed a cohesive social movement managed through intimate social ties. Intermarriages connected key white power groups, and Christian Identity and Dualist pastors provided marriage counseling. White power activists, who often traveled with their families, stayed at each other’s homes and cared for each other’s children. They participated in weddings and other social rituals and depended on others in the movement for help and for money when arrested. They founded schools to teach their ideas. The Dualist Mountain Church, for instance, hung Nazi flags and performed cross-burnings, but also held “namegivings,” weddings, “consolamentum” ceremonies for the sick, and last rites.20

In September 1979, two months before the Greensboro shooting, about 100 neo-Nazis, National States’ Rights Party members, and Klansmen of various groups convened in Louisburg, North Carolina. Leroy Gibson, convicted in 1974 of two civil-rights-era Klan bombings, organized the meeting. Gibson, who claimed twenty years of service in the Marine Corps, said that 90 percent of his faction, the Rights of White People, was composed of veterans. Gibson described paramilitary training and free instruction for local high school students. Harold Covington, leader of the National Socialist Party of America, spoke of Nazi paramilitary training camps in two North Carolina counties. “Piece by piece, bit by bit, we are going to take back this country!” he said, holding aloft an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle.21 A rope noose was strung from a tree outside the lodge “for purely inspirational purposes,” as Klan Grand Dragon Gorrell Pierce told an Associated Press reporter.22 Many activists attended the meeting heavily armed.

Participants called the rally the first North Carolina meeting of Klansmen and neo-Nazis, although the groups had begun cooperating as early as February. Activists understood how World War II affected relations between their groups. “You take a man who fought in the Second World War, it’s hard for him to sit down in a room full of swastikas,” Pierce said. “But people realize time is running out. We’re going to have to get together. We’re like hornets. We’re more effective when we’re organized.” Pierce argued that urgent threats—particularly communism—required Nazis and Klansmen to band together.23 They named their coalition the United Racist Front and pledged to share resources.

Shifting from the openly segregationist language of the civil rights era to a discourse in which anticommunism was used as an alibi for racism, Klansmen spoke publicly of race as a secondary concern. “The one thread that links all Klan factions and other extreme right-wing groups such as Nazis is hatred of communists,” one Associated Press article reported just after the shooting. “Blacks, they say, are pawns of communism, and integration is merely one salvo in the communist battle to destroy the United States.”24

This strategy drew on a long history of Klan rhetoric that intertwined racial equality, communism, labor organization, immigration, anti-imperialism, and internationalism as threats to the “100 percent American” nationalism early Klans sought to defend. Such ideas were linked not only in Klan rhetoric but also on the left. In Alabama, for instance, the Communist Party attempted in the 1930s to mobilize the same groups targeted by Klan vigilantism and harassment. Communists called the Jim Crow South an oppressed nation, pushed for black self-determination, decried lynching, and defended black men accused of rape. They organized for shorter workdays, better labor conditions, and the right of tenant farmers to engage in collective bargaining. Those who opposed communism in the South—not only the Klan, but many southerners—explicitly associated communism with free love, assaults on the family and on the church, homosexuality, the idea of white women becoming public property, and the threat of interracial sex. In this way, communism and unionization were seen as threats to the white supremacist racial order, which the Klan purported to defend.25

In the days before the Greensboro shooting, the men who would join the caravan papered the North Carolina city with posters of a lynched body in silhouette, hanging from a tree. Part of the caption read “It’s time for old-fashioned American Justice.” (Four years later, the same language and graphic would appear on a poster for Posse Comitatus in the Midwest. The Posse would use the Klan graphic in 1983 to encourage its members to stockpile guns and ammunition in preparation for white revolution. The flier promoted its own circulation: “Reprint permission granted,” it read. “Pass on to a friend.”)26

When the Klan and Nazi caravan drove to Greensboro on November 3, its members expected to wage war on communists. The CWP prepared for confrontation as well, anticipating the brawling that had characterized such clashes in previous years. Several communists wore hard hats. Others armed themselves with police clubs and sticks of firewood. Some brought small guns to the demonstration, though these were mostly left in locked cars.27

But the United Racist Front in North Carolina, following the movement at large, had outfitted itself as a paramilitary force. White power activists brought three handguns, two rifles, three shotguns, nunchucks, hunting knives, brass knuckles, ax handles, clubs, chains, tear gas, and mace. Roland Wayne Wood, a neo-Nazi who had served as a Green Beret in Vietnam, had a tear gas grenade, possibly stolen from nearby Fort Bragg; he wore his army boots. They had packed several dozen eggs for heckling and “a .22 cal revolver as fresh as the eggs—a receipt for its purchase was with it.” This implied that the Klansmen and Nazis armed themselves particularly for the November 3 confrontation, with plans to use the guns. They also had two semiautomatic handguns and an AR-180 semiautomatic rifle, a civilian version of a military assault rifle. The Vietnam War’s guns and uniforms framed this attack, much as the war’s narrative framed the larger movement.28

Significantly, although the Vietnam War had also impacted the left, the militarization of the left never matched that of the paramilitary right, in part because of the right’s cultural embrace of weapons and in part because of the matériel and active-duty personnel that the white power movement continued to draw from the U.S. Armed Forces. Veterans led leftist groups like the CWP, continuing a legacy of protest and armed self-defense begun by veterans of color who participated in civil rights, armed self-defense, and other left movements after homecoming. In Greensboro, one of the CWP leaders, Nelson Johnson, was a local black activist who had fought in Vietnam. While some on the left advocated radical activism in the name of anti-colonial self-determination, however, many wavered on the use of violence.29

On the sunny Saturday morning of November 3, 1979, CWP members arrived in Greensboro’s Morningside Homes, a black housing project, to stage their widely publicized “Death to the Klan” demonstration. Three television news crews arrived. At a rally preceding the march, protestors—along with a number of children wearing red berets—milled around the intersection, singing protest songs and burning a Klansman in effigy. While the group expected confrontation during the march, they did not expect it at the rally. And, due to a series of command decisions and miscommunications, local police had not provided on-site protection, but instead stationed their cars and personnel several blocks away.30

Meanwhile, Klansmen and Nazis convened at a member’s home and talked about “getting into some fistfights” with the communists. Caudle showed people a military machine gun and told them he could get more for $280 each. Spurred on by Eddie Dawson, a longtime Klansman and sometime FBI informant, they grabbed guns and formed a caravan of cars. They intended to picket the march, taunting and throwing eggs, but they also brought the guns and planned to use them if necessary. As Klansman Mark Sherer would later testify, “By the time the Klan caravan left … it was generally understood that our plan was to provoke the Communists and blacks into fighting and to be sure that when the fighting broke out the Klan and the Nazis would win. We were prepared to win any physical confrontation between the two sides.”31

As the caravan of cars approached, a news camera zoomed in, refocusing on a Confederate flag license plate. The protestors took up the chant: “Death to the Klan, death to the Klan.” People in the caravan screamed racial slurs. A young black man yelled, “Get up,” beckoning at the Klansmen and Nazis in the cars. A black demonstrator hit a car with a stick as it accelerated at him; the car swerved wildly at the demonstrators. A teenage white girl shouted from one of the cars, calling the protestors “kikes” and “nigger-lovers.” In a pickup truck, Sherer, smiling, hung out of the front window and fired the first shot in the air, with a powder pistol. The air turned heavy with blue smoke. Another Klansman fired, also pointing his shotgun in the air. Sherer fired twice more, claiming later that these shots hit the ground and a parked car.32

A young Klansman yelled into the CB radio, “My wife’s in one of those cars!”33 Klansmen and neo-Nazis climbed out of the vehicles and ran toward the intersection. The groups met, fighting with fists and sticks.34 CWP member Sandi Smith screamed for someone to get the children out of the way; a black woman, eight months pregnant, lost her balance and fell while trying to run away, her legs pelted with birdshot.35 CWP member Jim Waller retrieved a fellow protestor’s shotgun from a parked car, pulled it up, and aimed it at Klansman Roy Toney. They struggled, and the gun fired twice.36

As the shots continued, a few communist protestors reached for their handguns. Caudle climbed out of his powder-blue Ford Fairlane and walked calmly around to the trunk, from which he distributed shotguns, rifles, and semiautomatic weapons to six men. One of these men, Klansman Jerry Paul Smith—a cigarette dangling from his lower lip—dropped one knee to the ground, a gun in each hand, as he fired into the panicking crowd. Others took aim and shot, over and over. One gunman, a survivor remembered, passed up a clean shot at a white woman in order to kill Sandi Smith, a black woman, instead.37 Klansman Dave Matthews, firing buckshot, would later recount, “I got three of ’em”;38 neo-Nazi Roland Wayne Wood, who had a 12-gauge pump shotgun, would claim, “I hit four of the five that were killed and wounded six more.”39 Three minutes after the first shot, twelve Klansmen and neo-Nazis, including Jerry Paul Smith, Wood, Matthews, Harold Flowers, Terry Hartsoe, and Michael Clinton, climbed into a yellow van and drove away. The police didn’t arrive until the gunfire had subsided and the yellow van had fled the scene. By then, five protestors lay dead or mortally wounded; as many as seven more protestors and one Klansman were injured, and damage to the Morningside Homes community would reverberate across generations.40 The dead included Cesar Cauce, shot by a .357 Magnum in the neck, heart, and lungs. Michael Nathan had “half his head shot off.” Jim Waller lay dead with fifteen bullets in his body. Bill Sampson was shot in the heart; Sandi Smith was shot between the eyes. Paul Bermanzohn, who survived, was shot twice in the head and once in the arm. He underwent major brain surgery and spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair.41

Despite the threats and altercations leading up to the clash, the shooting took Greensboro by surprise. A town of textile mills, rapidly developing Greensboro had a reputation for progressivism but low rates of unionization. The city prided itself on its civil rights history—the Woolworth’s of the first lunch counter sit-in of the civil rights movement, in 1960, would become a designated landmark downtown. Greensboro’s civil rights record, however, turned on a “progressive mystique” that placed a premium on civility, consensus, and paternalism. While protestors experienced a notably lower level of violence in the Carolinas than in the Deep South, North Carolina was still a stronghold of civil-rights-era Klan activity.42

The Greensboro shooting briefly garnered national attention, making Time, Newsweek, and the front pages of several major papers including the Boston Globe, Miami Herald, New York Times, and Times-Picayune. President Jimmy Carter ordered an investigation into Klan resurgence on November 5, and his press secretary announced that a special unit of twenty-five FBI agents had been assigned to the case. Also on November 5, however, the Iran hostage crisis took the front page and held it for some fourteen months. Greensboro became a strange aside, lost in the inner pages of national newspapers.43

But within the white power movement, Greensboro served to energize activists. A few months later, Metzger’s KKKK organized another march in Oceanside, California. Local police had to separate Klansmen from counterprotestors, who shouted “Death to the Klan!” as both sides threw rocks and bottles. Klansmen kicked and beat one member of the Revolutionary Socialist League until blood covered his head and face.44 As they marched, wielding bats, the Klansmen sang a song to the tune of “Sixteen Tons” that lauded the altercation in Greensboro and ended with the refrain, “If the Nazis don’t get you, a Klansman will.”45 The U.S. Department of Justice marked 1979 as a particularly violent year, noting that serious Klan violence had increased 450 percent.46

The movement drew on anticommunism to classify that violence as self-defense. Klansmen and neo-Nazis involved in the November 3 shooting almost uniformly invoked the Vietnam War to justify their actions. As Klansman Virgil Griffin—the Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire KKKK, who had brought a semiautomatic handgun to the November 3 march47—said in a public statement long after the shooting:

I think every time a senator or a congressman walks by the Vietnam Wall, they ought to hang their damn heads in shame for allowing the Communist Party to be in this country. Our boys went over there fighting communism, came back here and got off the planes, and them … that they call the CWP was out there spitting on them, calling them babykillers, cursing them. If the city and Congress had been worth a damn, they would’ve told them soldiers turn your guns on them, we whupped Communists over there, we’ll whup it in the United States and clean it up here.48

Griffin saw the Vietnam War not only as a war between nations but also as a universal, man-to-man conflict between communists and anticommunists. He had tried three times to enlist, he said, but doctors declared him unfit for duty because of his asthma. Griffin’s Vietnam War, real to him, was in the realm of a popular narrative. Within that story, he equated all antiwar protestors with the CWP and all veterans with the Klan.49

Michael Clinton, a Klansman who rode in the yellow van on November 3, had a good record of army service, his wife told a reporter. He was drawn into the Klan because of its anticommunism and its paramilitarism. And the wife of caravan member Harold Flowers, the only Klansman injured on November 3, expressed her anticommunism as a common view: “Everybody has concerns.”50

Following the shooting, the local district attorney’s office pressed charges against all fourteen of the Nazis and Klansmen who had been arrested after the melee. Charges included four counts of first-degree murder, one count of felony riot, and one count of conspiracy.

The defendants called upon the Vietnam War story to raise money for their defense. Several of the men from the caravan posed for a photograph in front of the local Vietnam War memorial. The signed photo circulated in the Thunderbolt under the heading “Dangerous Communists Killed” and was reprinted in other white power publications. In an attempt to raise money for the defense and awareness for their cause, the photo also appeared in the Talon, a white power periodical that made its way—free of charge—to prison inmates.51

Trial proceedings began on August 4, 1980, and from the outset reflected the entrenched racism of the North Carolina judicial system. The allowance of peremptory challenges—dismissal of jurors without explanation—meant that the defense could easily select an all-white jury. With fourteen people on trial, the defense had a total of eighty-four peremptory challenges to use at its discretion: defense attorneys dismissed fifteen black jurors for cause and another sixteen peremptorily. This system so clearly produced racially biased juries that North Carolina would abolish it in 1986.52 In this case, it ensured a jury sympathetic to the defendants.

The all-white jurors were all Christian and therefore likely to be fundamentally opposed to communism, understood in 1979 as a threat to any organized religion and, in the South, tinged with the threat of race mixing. Jurors repeatedly voiced anticommunist rhetoric. Foreman Octavio Manduley, who had fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the 1960s, spoke frequently to the press about his strident anticommunism, allegedly telling a reporter that the CWP was like “any other Communist organization” and needed “publicity and a martyr.” He implied that the CWP had staged the November 3 altercation with the intention of getting one of its members killed in order to bring attention to its cause. His view resonated with a summary presented in the Thunderbolt: “The hitch came when they got more martyrs than they intended.” The Thunderbolt also reported that Manduley called the Klan “a patriotic organization.”53

Manduley quickly became a favorite of the white power movement, held up as an example of white, anticommunist, first-wave Cuban immigration. Slain CWP member and fellow Cuban Cesar Cauce, on the other hand, was painted as “a pro-Castro enemy agent” of questionable whiteness. Cauce had come to the United States later than Manduley; the Thunderbolt claimed Cauce was “on the first boatlift of so-called refugees. Fidel Castro used the boatlift to empty his prisons and insane asylums of thousands of undesirables to further destabilize America for his planned communist overthrow of the U.S. Government in the future.” This passage conflated Cauce’s arrival with the 1980 Mariel boatlift, which Castro had indeed used to move inmates to the United States. The white power focus on immigrants as communists and as threats to whiteness was a thread that connected the Greensboro shootings to the Klan harassment of Vietnamese refugees on the Texas Coast.54

Although later proceedings would cast doubt on whether Manduley had really expressed views that the Klan was “patriotic” and the neo-Nazis were “strongly patriotic,” at least one juror did make those comments.55 Other jurors and potential jurors expressed sympathy with the defendants or distrust of the CWP. One prospective juror said of the gunmen, “I don’t believe that they were guilty of anything but poor shooting.” Another said of the slain, “I think we are better off without them.”56 One juror, the wife of a sheriff’s deputy, commented after the not-guilty verdict, “I’m really worried about the spread of communism.”57 A man who was chosen as an alternate juror said he believed that it was less of a crime to kill a communist than to kill someone else. According to the Thunderbolt, another juror “stated that the communists got themselves in too deep when they challenged the Klan to attend their ‘Death to the Klan’ rally.… The Klansmen were simply the superior marksmen.”58

Those responsible for the prosecution of the gunmen also reportedly expressed prejudice. Even district attorney Mike Schlosser drew connections between peacetime communist protestors in North Carolina and communist soldiers abroad; when asked by a reporter about his ability to objectively prosecute the Klan and neo-Nazi gunmen, Schlosser referenced his own experience fighting in Vietnam and added, “And you know who my adversaries were there.” In another public comment, Schlosser reportedly said that the Greensboro community felt the CWP members got what they deserved.59

Besides the anticommunism that framed the proceedings, the state trial failed to take into account the role of two government informants who had foreknowledge of the Greensboro shooting and may have actively incited the altercation. Neither prosecution nor defense called them as witnesses. Two other key witnesses against the white power activists also refused to testify because of their fear of reprisal, surrounded as they were by a paramilitary and demonstrably lethal white power movement.60

Public distrust of the CWP mobilized sympathy for the white power gunmen. Furthermore, CWP members repeatedly undermined their chance at what justice the court could offer. Several of the women widowed on November 3 confounded the Greensboro community when, instead of weeping or grieving, they stood with their fists raised and declared to the television cameras that they would seek communist revolution.61 Days after the shooting, an article appeared in the Greensboro Record that was titled “Slain CWP Man Talked of Martyrdom” and implied that the CWP had foreknowledge of the shooting and that some planned to die for the cause. This damaged what little public sympathy remained. In language typical of mainstream coverage, the story described the CWP as “far-out zealots infiltrat[ing] a peaceful neighborhood.” Even two years later, when the widows visited the Greensboro cemetery and found their husbands’ headstone vandalized with red paint meant to symbolize blood, they would not be able to effectively mobilize public sympathy.62

Community wariness of the CWP’s militant stance only increased after the CWP held a public funeral for their fallen comrades and marched through town with rifles and shotguns. The fact that the weapons were not loaded hardly mattered: photographs of the widows holding weapons at the ready appeared in local and national newspapers. In the public imagination, these images inverted the real events of November 3, when a heavily armed white power paramilitary squad confronted a minimally armed group of protestors. The defendants, depicted as respectable men wearing suits in front of the Vietnam War memorial, stood in stark contrast to the gun-toting widows.63

National and local CWP members took up a campaign of hostile protest of the trial itself. The day before testimony began, the CWP burned a large swastika into the lawn of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms director, and hung an effigy on his property with a red dot meant to convey a bullet wound. In the trial itself, CWP members refused to testify, even to identify the bodies of their fallen comrades. CWP widows who shouted that the trial was “a sham” and emptied a vial of skunk oil in the courtroom were held in contempt of court. Although the actions of the widows may have “shocked the court and freaked out the judge,” as the CWP newspaper Workers Viewpoint proudly reported, the widows’ “bravery” didn’t translate as such to the Greensboro community.64 Even those who may have sympathized with the CWP after seeing the graphic footage of the shooting soon found that feeling complicated by the group’s contempt for the justice system, however problematic that system was.

With the CWP widows refusing to tell their stories, attorneys for the defendants built a self-defense case by deploying two widely used white power narratives: one of honorable and wronged Vietnam veterans, and the other of the defense of white womanhood. The defense depended on the claim that CWP members carrying sticks had threatened Renee Hartsoe, the seventeen-year-old wife of Klansman Terry Hartsoe, as she rode in a car near the front of the caravan. Terry Hartsoe testified that he could see the communist protestors throwing rocks at the car and trying to open the door. Such a statement can be seen as alluding to the threat of rape of white women by nonwhite men, a constant theme throughout the various iterations of the Klan since the end of the Civil War.65 White supremacy has long deployed violence by claiming to protect vulnerable white women.

To bolster the claim that the CWP had started the fight, and that the Klansmen and Nazis had acted in self-defense, attorneys called an expert witness from the FBI. Based on the locations of the news cameras that had recorded the altercation, he said, he could pinpoint the origin of each shot with new sound-wave technology. Using this new and insufficiently tested method—later broadly discredited—he testified that the CWP had fired several of the first shots. In other words, the defense convinced the jury that the CWP had started the fight. However, under North Carolina law, the claim of self-defense should have been limited to defendants free from fault in planning or provoking a confrontation. Even had the CWP fired first, the Klansmen and Nazis intended to incite a fight, and had planned it in advance. Their armament alone, and the receipts that showed the timing, indicated as much.66

Meanwhile, some defendants showed little or no remorse for the five deaths and numerous injuries that resulted from the shooting. Defendants testified at the trial that members of the white power movement had displayed autopsy photographs of the CWP victims at a Klan fundraising rally on September 13, 1980. Jerry Paul Smith had obtained copies of the autopsy photos, as well as photos of the dead and mutilated victims taken just after the shooting, from the office of one of the defense attorneys. Smith said someone had displayed the photos at the Klan rally without his knowledge, and that he asked for them to be put away when he saw them.67

The jury spent long hours watching the footage of the shooting—forward, backward, and in slow motion—and witnessed the raw violence of the event. However, jurors heard nothing of the Klan’s use of graphic photographs of the victims for fundraising; they were out of the courtroom when this information came to light. Prosecutors argued that the “jury should hear the testimony, saying it shows the Klansmen acted with malice and have no regrets about the deaths of five Communist Workers Party members,” but the judge disagreed. The jury deliberated without accounting for the continuing violence manifested in the circulation of those images, including profiting from the photographs of the wounded, mutilated, and dead. Such action recalled a long history of circulating lynching photographs. The white power movement was using the pictures to raise money not only for the defense of the “Greensboro 14” but also for acquiring weapons to use in future violent actions—including a projected race war.68

On November 17, 1980, the jury arrived at a unanimous not-guilty verdict after six days of deliberation and twelve major votes. Surprised Klansmen and neo-Nazis wept. The verdict was a national news story. Saturday Night Live even ran a sketch depicting the opening day of “Commie Hunting Season.” The performance received little laughter and scant applause from the live studio audience, and NBC received 150 phone complaints that it was offensive. Perhaps the accuracy of the sketch, despite its overwrought redneck accents and heavy-handed satire, rendered it humorless. The basic point, that a court had effectively condoned the intentional killing of communists, rang true.69

After the acquittal, the white power movement amplified its praise of the Greensboro 14. The Thunderbolt reported at length that the men showed courage during the long trial, from praying and singing “God Bless America” in jail to their heroic homecoming. Family, neighbors, and fellow Klansmen cheered for Smith when he returned home, where “he proudly wore a [Confederate States of America] belt buckle and flew the Confederate flag over his house. One neighbor … remarked: ‘I’ve said all along they ought to pin a medal on those boys.’ ” A journalist reported that Smith’s “feelings toward blacks have softened, partly because of black prisoners he met in jail.” His alleged contrition didn’t last long. Two days later, Smith crashed his car after exchanging gunshots with an unknown person.70

Smith had testified in court that, after a blow to the head, he had no memory of firing into the crowd in Greensboro with a gun in each hand. But he soon traveled to Texas to recount the shooting as a guest speaker at a rally of Klansmen mobilizing against Vietnamese refugees. By 1984, members of the movement could buy a ninety-minute interview of Smith on audiocassette, in which he retold the shooting in detail. The story he allegedly didn’t remember became his currency and celebrity within the movement.71

Indeed, the white power movement took the acquittal as a green light for future action. The Aryan Nations organ Calling Our Nation ran photographs of neo-Nazis in Detroit marching with signs reading “Smash Communism: Greensboro AGAIN.” To some, the trial stood as one battle won in a global war against communism, the same war they had fought in Vietnam. As Klansman and defendant Coleman Pridmore remarked: “This is a victory for America. Anytime you defeat communism, it’s a victory for America. The communists want to destroy America, to tear it down, and they should be tried for treason.”72

The Greensboro case went to trial again on January 9, 1984, this time under civil rights laws in federal court. Although an appeals court blocked a court-ordered federal investigation into “charges of high-level government involvement” under the Ethics in Government Act, this time the court did allow investigation into the role of government informants who provoked or failed to prevent the altercation.73 The FBI and ATF had long used undercover agents in attempts to arrest members of fringe groups on both left and right, and would continue to do so in the years that followed. However, the 1971 end of COINTELPRO made it illegal for undercover operatives to act as agents provocateurs or to initiate or incite violence. The first man in question, Eddie Dawson, was a longtime Klansman who had occasionally reported information to the Greensboro Police Department and FBI. The second, Bernard Butkovich, was a career ATF agent working undercover.74

According to three neo-Nazis and one Klansman, Butkovich—posing as a trucker interested in the movement—had foreknowledge of the Greensboro caravan and did not report it to other agents, his superiors, the FBI, or local law enforcement. He allegedly suggested several illegal activities, encouraging people to get equipment used to convert weapons to fully automatic function and suggesting the assassination of a rival Klan leader. Group members also said Butkovich advised white power activists to harbor the November 3 fugitives after the shooting. The Klansmen and Nazis didn’t take any of his suggestions. Butkovich defended his actions—with the support of his superiors in the ATF—by saying that these statements were necessary to establish him as a credible member of the group for future intelligence-gathering purposes. Butkovich had met Covington and Wood at a White Power Party rally in Ohio in June 1979, but his wire had gone dead, failing to record a lengthy section of their meeting.75

Eddie Dawson, on the other hand, actively worked to plan and provoke the November 3 clash. Dawson gave speeches to fire up the Klansmen and Nazis to protest the CWP rally, according to Klansman Chris Benson’s later trial testimony. And police knew that Dawson was bringing the Klan to confront the CWP. They knew the Klansmen had eggs and planned to heckle, and that they had guns. They knew Virgil Griffin was involved, that he had “a hot head with a short fuse,” and that he frequently carried weapons.76

Dawson obtained a copy of the CWP parade permit prior to November 3 and so he knew where to find the communists. That day, he urged the caravan members to hurry to the CWP rally. At the same moment, the Greensboro Police Department ordered two officers on an unrelated call away from the neighborhood, and sent the rest of the force to lunch. As a result of this sequence of events—as well as prior confrontations between the CWP and the local police that had led the latter to decide that officers would protect the demonstration from afar—no police officers were on the scene when the shooting began.77

The evidence in the federal trial clearly established that the earlier claim of self-defense could not stand. As one prosecutor noted, the Klansmen and Nazis “fired 11 shots before any shot was fired in return,” by which point they had wounded several people. Mark Sherer, who had by then quit the Klan, testified that Griffin had planned to incite a race war in North Carolina and that Smith had experimented with making pipe bombs. Butkovich had overheard a Klansman say the explosives would “work good thrown into a crowd of niggers,” but had failed to mention bombs in his ATF paperwork. Sherer now indicated that the Klansmen and Nazis fired the third and fourth shots, which had been attributed to the CWP by faulty sound analysis in the state trial.78

Despite substantial evidence to discredit the claim of self-defense—and despite the full cooperation and testimony of the CWP—the federal trial exonerated the Klansmen and neo-Nazis a second time. Prosecutors sought to prove that by shooting and killing them, the Klansmen and neo-Nazis denied the CWP members their civil rights for reasons of race. To make this case, the jury instructions specified, the prosecution had to show that race was the “substantial motivating factor” behind the violence. The defense countered that the Klansmen and neo-Nazis acted on political, not racial, motives. They were, as they had said repeatedly, trying to defend the United States from communism. And since the connection between anticommunism and racism in the ideology of white power activists went unexplained, the Klansmen and neo-Nazis walked free again in April 1984.79

The third and final trial began in March 1985. In a civil suit, the CWP widows and eleven injured demonstrators sought monetary damages from the Klansmen, the neo-Nazis, Dawson, Butkovich, the Greensboro Police Department, the City of Greensboro, the State Bureau of Investigation, the FBI, the ATF, and more. The judge dismissed several of these defendants, including the federal agencies that had sovereign immunity, and also dismissed a number of unknown “John Does” because charges against them were too vague. The case went to trial with sixty-three defendants.80

Attorneys for the plaintiffs called seventy-five witnesses over eight weeks; the defense lasted four days. In the most dramatic moment of the trial, former Klansman Chris Benson testified that he had previously lied in court because he feared retaliation. Benson had been the second-highest-ranking Klansman in the Greensboro caravan, and in earlier trials had maintained that the CWP demonstrators provoked the violence. Now he said that white power activists had intended to provoke a confrontation. In cross-examination by Klansmen and Nazis representing themselves, Benson “said he had particularly feared the ‘underground Klan,’ which he described as a paramilitary group that would ‘carry out acts to intimidate people.’ ” Benson named members of the paramilitary Klan, including co-defendant Dave Matthews, and added, “I saw Mr. Matthews shooting at people in Greensboro who were running away from him.”81

Benson, reformed and contrite, stood in stark contrast with most of the other defendants. On the first day of the trial Roland Wayne Wood wore “an olive drab T-shirt with the phrase ‘Eat lead, you lousy red’ printed next to an image of a man in camouflage fatigues spraying automatic weapon fire.” Because Wood chose to represent himself in the civil trial, he wore the shirt in court while acting as a part of the U.S. justice system.82

Despite compelling evidence, the jury, which this time included one black member, delivered only partial justice. In June 1985, it found some of the absent policemen and some of the white power gunmen—Dave Matthews, Jerry Paul Smith, Roland Wayne Wood, Jack Fowler, and Mark Sherer—jointly liable for one of the five deaths and two of the many injuries. Significantly, the only death found wrongful was that of Michael Nathan, the only one of the five people killed who was not a card-carrying CWP member. It might be wrong to shoot bystanders, the decision confirmed, but there was nothing wrongful about gunning down communists. The City of Greensboro paid the full amount of the settlement, covering the costs for Klansmen and neo-Nazis.83

Once again, the white power movement took the settlement payment as endorsement of violent action. As Klansman and Thunderbolt editor Ed Fields wrote in his 1984 personal newsletter, “We must increase activity while we are still free—while juries made up of God fearing White people will free our street activists such as in the Greensboro case.”84 Louis Beam, too, saw Greensboro as a success for the movement. In a film of Beam’s paramilitary camps in Texas circa 1980, he told the camera, “When the shooting starts, we’re going to win it, just like we did in Greensboro.”85

The Greensboro shooting had the effect of consolidating and unifying the white power movement. Most directly, caravan participant Glenn Miller would use the shooting to leverage state leadership in the North Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which would soon change its name to the White Patriot Party, uniform its members in camouflage fatigues, and march through the streets by the hundreds. In his increasingly revolutionary Confederate Leader, Miller expressed pride about the shooting even six years afterward.86 A veteran who served two tours in Vietnam as a Green Beret, Miller used paramilitary camps to prepare his new white army for race war, recruited active-duty soldiers, and obtained stolen military weapons. Soon he would align his force with the white power terrorist group the Order.87

The idea of worldwide struggle against communism also aligned the Greensboro gunmen with antidemocratic paramilitary violence in other countries. Thunderbolt, for instance, called it “very strange” to hear President Ronald Reagan “pleading for money to send to guerillas” fighting against communists in Nicaragua and El Salvador when “right here in America we have a clear case of White Christian family men being shot at by communists who returned fire in a perfect case of self-defense.”88 To the movement, there was little difference between white power gunmen at home and paramilitary fighters who worked to extend U.S. interventions abroad.

Harold Covington, an American Nazi Party Leader and veteran who claimed to have been a mercenary soldier in Rhodesia, did not participate in the Greensboro caravan, but sent several of his men to the skirmish. Shortly before the shooting, Covington wrote a letter to the Revolutionary Communist Party, which he mistook for the CWP. “Almost all of my men have killed Communists in Vietnam and I was in Rhodesia as well,” he wrote, “but so far we’ve never actually had a chance to kill the home-grown product.”89 Covington, who saw himself as a person who killed communists—he killed them abroad and he intended to kill them at home—showed how violence at home and anticommunist interventions abroad would link white power organizing with a network of mercenary soldiers who waged war in Central America and beyond.

Katherine Belew, Bring the War Home

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

NATIONAL LIBRARY WEEK 2019

HAPPY NATIONAL LIBRARY WEEK, BOOKWORMS AND LIBRARY CATS!

Our favorite time of year has come around again! For those of you who are long-time followers of ours, you know what this means: It’s time to shower your local (and not so local) libraries with all the love we can muster online and in person!

For those of you who may be new here, every year during National Library Week, we make a list of all the library tumblrs that follow us and/or we follow so that you bookworms and library cats can discover new booklrs and fantastic library content! This year the tradition continues with our updated 2019 Master List.

Without further ado, show these libraries some love and (if you aren’t already) #followalibrary!! (Including, hopefully, us! ;D Just putting it out there.)

(Alphabetical by url)

@agslibrary (American Geographical Society Library)

@alachualibrary (The Alachua County Library District)

@alt-library (By Sacramento Public Library)

@americanlibraryassoc (American Library Association)

@aplibrary (Abilene Public Library)

@austinpubliclibrary (Austin Public Library)

@badgerslrc (The Klamath Community College’s Learning Research Center)

@barbertonpubliclibrary (Barberton Public Library)

@bflteens (Baker Free Library’s Tumblr For Teens)

@biblioitesmgda (BiblioTECa en Guadalajara [Technological Library in Guadalajara])

@bibliosanvalentino (Biblioteca San Valentino [San Valentino Library])

@biodivlibrary (Biodiversity Heritage Library)

@bklynlibrary (Brooklyn Public Library)

@bodleianlibs (Bodleian Libraries)

@boonelibrary (Boone County Public Library)

@brkteenlib (Brookline Public Library Teen Services Department)

@californiastatelibrary (California State Library)

@carlblibrary (Concordia College’s Carl B. Ylvisaker Library)

@cheshirelibrary (Cheshire Public Library)

@cincylibrary (The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County)

@cityoflondonlibraries (City of London Libraries)

@cmclibraryteen (Cape May County Library’s Teen Services)

@cobblibrary (Cobb County Public Library System)

@cpl-archives (Cleveland Public Library Archives)

@cplsteens (Clearwater Public Library Teens)

@crossettlibrary (Crossett Library at Bennington College, Vermont)

@cscclibrary (Columbus State Library)

@darienlibrary (Darien Library)

@dcpubliclibrary (DC Public Library)

@decaturpubliclibrary (Decatur Public Library)

@delawarelibrary (Delaware County District Library - Teens)

@detroitlib (Detroit Public Library Music, Arts & Literature Department)

@dorcaslibrary (Dorcas Library)

@douglaslibraryteens (Douglas Library For Teens)

@dplteens (Danville Public Library Teens)

@ebrpl (East Baton Rouge Parish Library)

@escondidolibrary (Escondido Public Library)

@fdrlibrary (Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library)

@fontanalib (Fontana Regional Library)

@fppld-teens (Franklin Park Library Teens)

@friscolibrary (Frisco Public Library)

@gastonlibrary (Gaston County Public Library)

@gladstoneslibrary (Gladstone’s Library)

@glendaleteenlibrary (Glendale Public Library Teens)

@goffstownpubliclibrary (Goffstown Public Library)

@gtpubliclibrary (Georgetown Texas Public Library)

@hbalibrary (Hampton B. Allen Library)

@hpldreads (Havana Public Library District)

@hpl-teens (Homewood Public Library For Teens)

@huntingtonlibrary (Huntington Library)

@kingsbridgelibraryteens (Kingsbridge Library Teens Advisory Group)

@kpltumblarians (Librarians from the Kalamazoo Public Library)

@kzoolibrary (Kalamazoo Public Library)

@lanelibteens (Lane Memorial Library Teen Services)

@lawrencepubliclibrary (Lawrence Public Library)

@libraryadvocates (The American Library Association’s Washington Office Tumblr)

@librarylinknj (New Jersey Library Cooperative)

@lindylibrary (Lindenhurst Memorial Library Teen Zone)

@loudounlibrary (Loudoun County Public Library)

@marioncolibraries (Marion County Public Library System)

@merrickteens (Merrick Library)

@messengerplteens (Messenger Public Library Teens)

@mobilepubliclibraryteens (Mobile Public Library Teens)

@movallibrary (Moreno Valley Public Library

@mrcplteens (Mansfield/Richland County Public Library Teen Zone)

@mvpubliclibrarymallbranch (Moreno Valley Public Library Mall Branch)

@myrichlandlibrary (Mansfield/Richland County Public Library)

@necclibrary (Northern Essex Community College Libraries)

@nevinslibrary (Nevins Library)

@nevinslibraryteens (Nevins Memorial Library Teens)

@norfolkplyouth (Norfolk Public Library Youth Services)

@novipubliclibrary (Novi Public Library)

@nplteens (Nashua Public Library Teens)

@nypl (New York Public Library)

@omahapubliclibrary (Omaha Public Library)

@orangecountylibrarysystem (Orange County Library System)

@osceolalibrary (Osceola Library System - THAT’S US!)

@othmeralia (Othmer Library of Chemical History)

@pclteens (Pittsford Community Library Teens)

@petit-branch-library (Petit Branch Library)

@pflibteens (Pflugerville Public Library Teenspace)

@phplyouthservices (Prospect Heights Public Library Youth Services)

@plainfieldlibrary (Plainfield Public Library District)

@providencepubliclibrary (Providence Public Library)

@ridgewoodlibya (Ridgewood Library Young Adult tumblr)

@royhartlibrary (RoyHart Community Library)

@safetyharborpubliclibrary (Safety Harbor Library Teen Zone)

@santacruzpl (Santa Cruz Public Libraries)

@santamonicalibr (Santa Monica Public Library)

@schlowlibrary (Schlow Centre Region Library)

@sclteenspace-blog (Springfield City Library Teen Space)

@scplteens (Shelby County Public Libraries - Teens)

@scvpubliclib (Santa Clarita Public Library)

@sfplhormelcenter (San Francisco Public Library’s James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center)

@smithsonianlibraries (Museum Library System)

@smlibrary (Sheppard Memorial Library)

@sonobranchlibrary (Norwalk Public Library - SoNo [South Norwalk] Branch Library)

@southeastlibrary (Southeast Branch Library)

@tampabaylibraryconsortium-blog (Tampa Bay Library Consortium)

@teenbookerie (Erie County Public Library For Teens)

@teencenterspl (The Smith Public Library Teen Center)

@teensfvrl (Fraser Valley Regional Library)

@teen-stuff-at-the-library (White Oak Library District)

@therealpasadenapubliclibrary (Pasadena Public Library)

@ucflibrary (University of Central Florida Library)

@uolincolnlibrary (University of Lincoln Library)

@usfspecialcollections (University of South Florida Special Collections)

@uwmspeccoll (University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections)

@vculibraries (Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries)

@virlibraryteens (Vancouver Island Regional Library Youth Services)

@waynecountyteenzone (Wayne County Public Library’s Teen Space)

@wellingtoncitylibraries (Wellington City Libraries)

@wflchildrensroom (Wellesley Free Library’s Children’s Room)

@widenerlibrary (Harvard’s Widener Library)

@woodlibraryteens (Wood Library’s Teen Services)

@wplteenspace (Woodbridge Public Library Teen Space)

Keep the Library love going by adding any Libraries we may have missed or don’t know of yet. And never forget we Libraries love all of our bookworms and library cats, and your support online and in person (*hint hint nudge nudge*) make all the difference!

Stay gold, and keep visiting your Libraries!

#national library week#follow a library#tumblr do the thing#library love!#libraries#follow back#just putting it out there#osceola library system#bookish#booklr

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

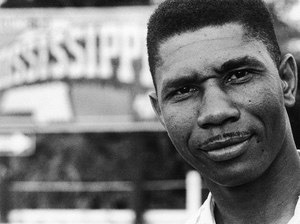

Happy EarthDay Medger Evers...

Medgar Evers was born on this date in 1925 in Decatur, Mississippi. He was an African American civil rights leader whose assassination for his work as field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

As a representative of the NAACP, Evers worked for the most established and in some ways most conservative African-American membership organization. He was, by all accounts, a hardworking, thoughtful, and somewhat quiet man. Yet the work Evers did was groundbreaking, even radical, in that he risked (and eventually lost) his life bringing news of his state's violent white supremacy to nationwide attention. When Byron De la Beckwith, a white racist, assassinated Evers in his front yard, he became a symbol of the brutality with which the old South resisted the Civil Rights Movement. Raised in a small central Mississippi town, Evers absorbed his parents' work ethic and strong religious values early in his life. Friends, including his brother, Charles, remember him as a serious child with an air of maturity about him.

At 17, he left school to serve in the army during World War II, where, according to writer Adam Nossiter, his experience fighting the supremely racist Nazis made a lasting impression on him. After the war, Evers got his high school diploma and immediately entered Alcorn A & M College, where he played football, ran track, edited the campus newspaper, and sang in the choir. Upon graduation, Evers took a job with Magnolia Mutual Insurance; one of Mississippi's few black-owned businesses.

Through his employer, Evers became involved with the NAACP, selling memberships at the same time he was selling insurance policies. Despite its moderate, systematic approach, the NAACP was still considered a radical organization by many in Mississippi, a state (Nossiter writes) the organization had essentially given up hope on. Too likely to become victims of harassment, assault, or murder for any kind of political action, blacks in Mississippi's Delta region were often afraid even to talk about the NAACP. In 1954, when the national organization decided to hire field secretaries in the Deep South, Evers moved to Jackson, the state capital, and went to work full-time for the NAACP. He had two main roles — to recruit and enroll new members, and to investigate and publicize the racist terrorism experienced by African-Americans.

It was a dangerous job. Evers was followed, mocked, threatened, and beaten while he traveled throughout Mississippi — the state that had seen more lynching than any other in the country. Organizations like the White Citizens' Councils and the State Sovereignty Committee spied on him. In May 1963, a month before Evers was murdered, someone threw a bomb into his garage. Evers continued the NAACP's longstanding research on lynching, and he also worked on the legal front, filing petitions and organizing protests against the Jim Crow segregation that still made it impossible for African-Americans to go to movie theaters, to eat in restaurants, or to make use of public libraries, parks, and pools.

Throughout the spring of 1963, Evers was the leader of a series of boycotts, meetings, and public appearances that were designed to bring Mississippi out of its racist past. Just before midnight on June 11, 1963, when Evers was arriving home, Bryon de la Beckwith shot him in the back. Evers died a few minutes later. In two separate trials in 1963 and 1964, all-white juries could not decide Beckwith's fate. Free for more than 30 years after committing murder, Beckwith was finally convicted and jailed for the crime in 1994.

Reference:

African Americans/Voices of Triumph

by Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Copyright 1993, TimeLife Inc.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry in the Time of Pandemic

Poetry in the Time of Pandemic

Last night, Poetry Atlanta and Georgia Center for the Book, in cooperation with the Decatur Public Library, put on a virtual poetry reading featuring Mike James, Julie E. Bloemeke, and yours truly. It was a really cool experience. I actually didn’t suffer stage fright for once, so I count that as a win. Because I couldn’t see the audience it was like I was reading to myself.

I read poems from W…

View On WordPress

#Decatur Public Library#Georgia Center for the Book#Julie Bloemeke#Mike James#Poetry Atlanta#Slide to Unlock#virtual

0 notes

Photo

Spent the afternoon yesterday awarding prizes for the Book As Art: Wonders exhibit at the Decatur branch of the DeKalb Public Library. It’s a great show. If you’re in Atlanta, come see it. Opening reception on August 23. @dekalblibrary #bookartsexhibition #artistsbooks #bookarts #atlantabookarts (at DeKalb County Public Library) https://www.instagram.com/p/B056yS3Hpi7/?igshid=1dl8po0spayk3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

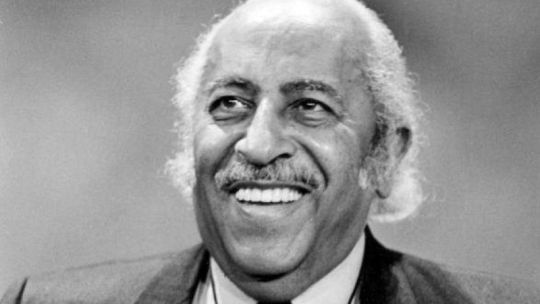

Arna Bontemps

Arnaud (Arna) Wendell Bontemps (October 13, 1902 – June 4, 1973) was an American poet, novelist and librarian, and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Early life