#Arles Christian Lacroix

Text

Christian Lacroix

Solare, opulento e virtuoso: Christian Lacroix

#christianlacroix #lacroix #moda #fashion #paris #creatoredimoda #creatoredistile #storiadellamoda #desigual #maison #hautecouture #perfettamentechic

Christian Lacroix è uno stilista francese e fondatore della Maison Christian Lacroix.

Christian è nato il 16 maggio 1951 ad Arles, Bouches-du-Rhône, nel sud della Francia. In giovane età ha iniziato a disegnare costumi storici. Dopo aver studiato storia dell’arte all’Università di Montpellier, nel 1973 si trasferisce a Parigi dove si iscrive alla Sorbona ed alla École du Louvre, studiando come…

View On WordPress

#90s#Air France#Aix-en-Provence#Ancona#Anna Wintour#Anniversary Collection#Arles#Arles Christian Lacroix#Art of Living#Avon#Avon Cosmetics#Baccaret#Barcellona#Bazar#Bazar Enfant#Bernard Arnault#Bijou#Bouches-du-Rhone#Boutique#Brian Kenny#Christian Lacroix#Christian Lacroix Absynthe#Christian Lacroix Ambre#Christian Lacroix Bijou#Christian Lacroix Costumier#Christian Lacroix Noir#Christian Lacroix Nuit#Christian Lacroix Rouge#Christina Aguilera#Christina Aguilera wedding dress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

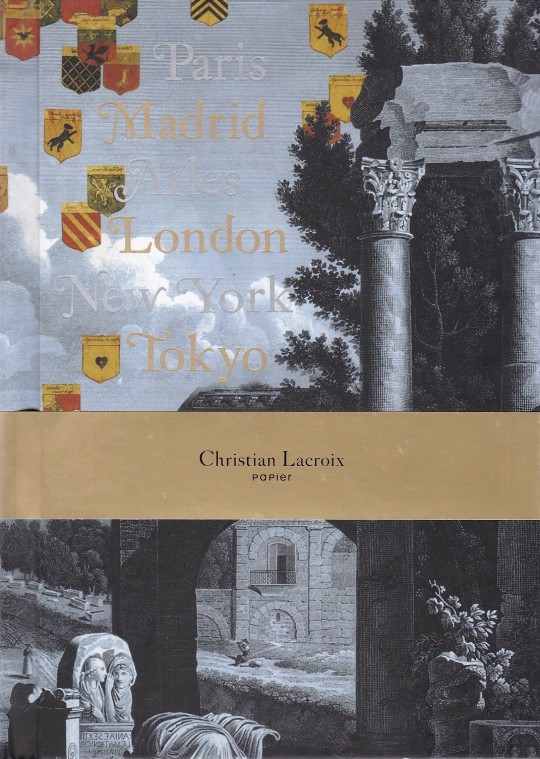

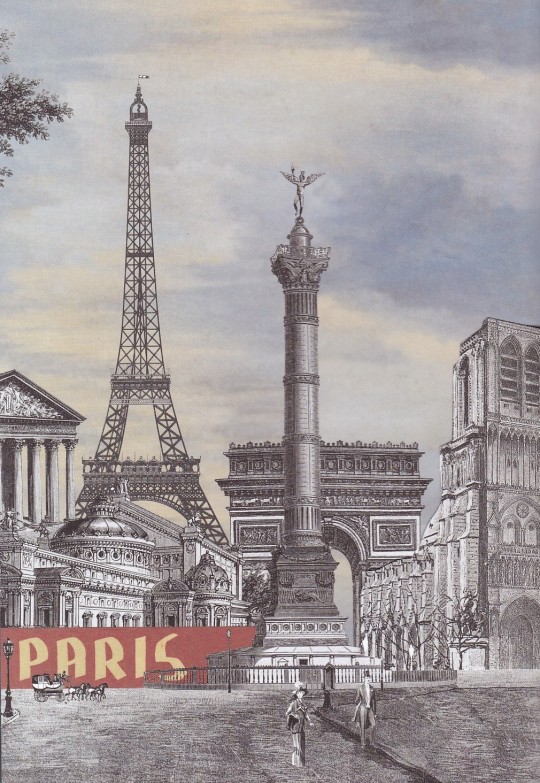

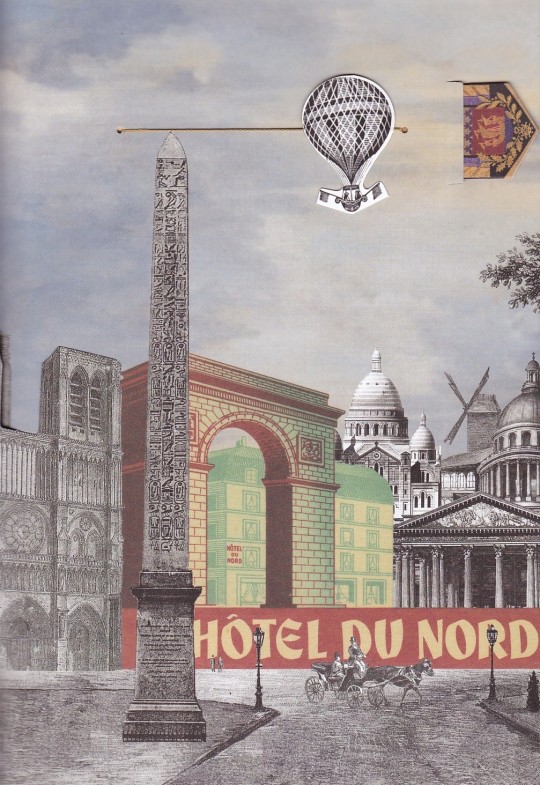

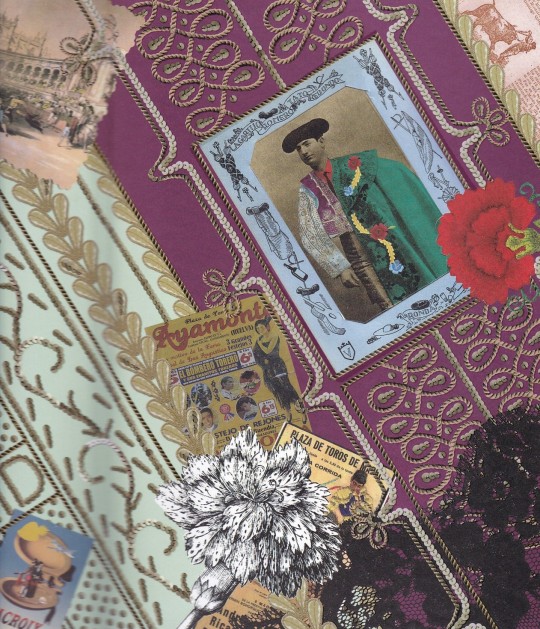

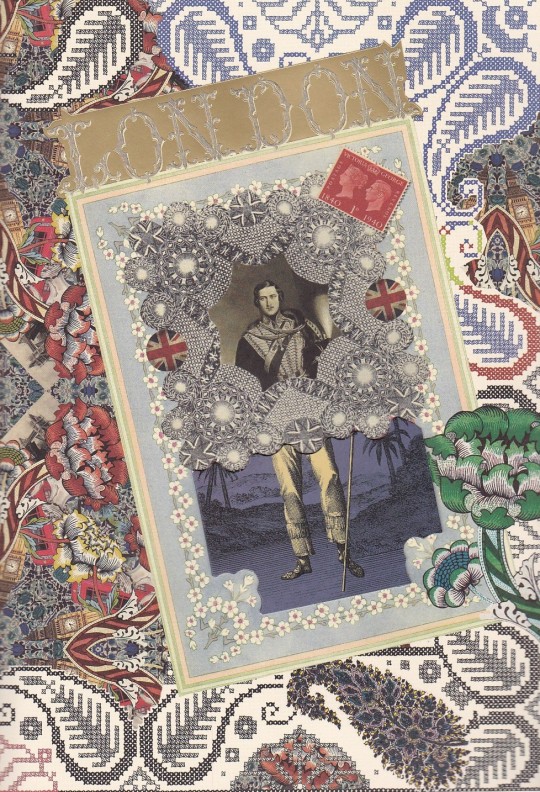

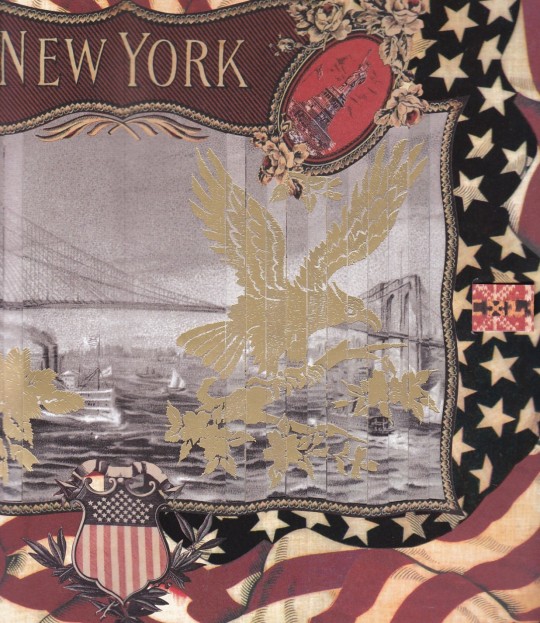

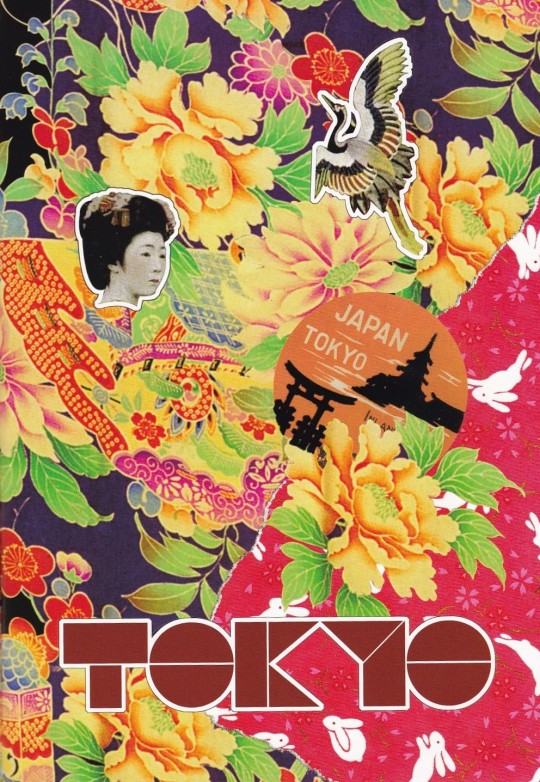

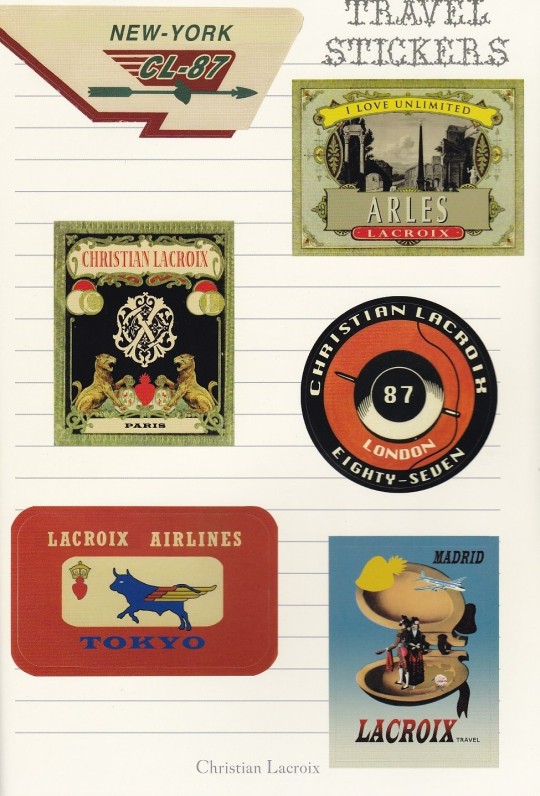

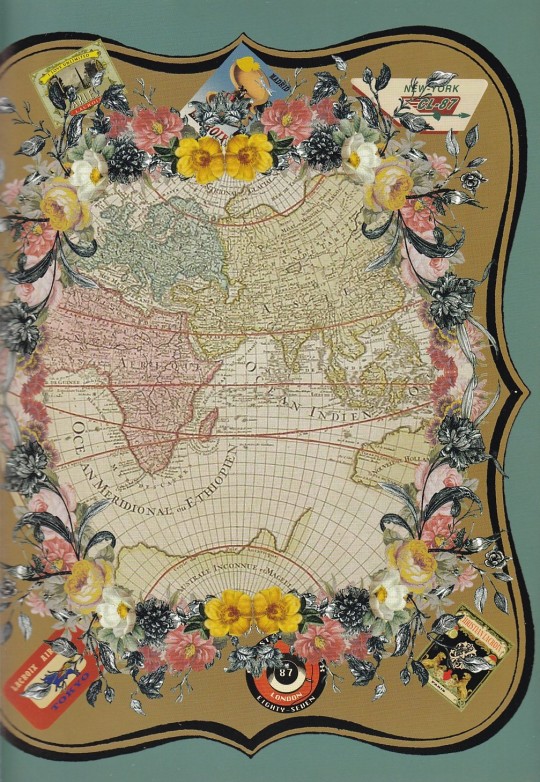

Christian Lacroix Voyage

Flocked Journal

Galison, New York 2016, 96 ruled ivory pages plus a page of old-fashioned travel stickers , Striped ribbon marker, 176x250mm, ISBN 9780735350380

ero 80,00

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

A book with multiple uses: travel log, diary, journal. Six great cities unfold: Paris, Madrid, London, Tokyo, Arles, and New York. Paper engineering and pop-up technology bring each city to life.

12/11/20

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Christian Lacroix#Lacroix#voyages#Paris#Madrid#London#Arles#New York#Tokyo#travel stickers#striped ribbon marker#fashionbooksmilano

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christian Lacroix

Editorial Illustrations for Illustrations for F/I/M²/P

#Illustration#editorial illustration#magazine#paris fashion week#fashion#pattern#mode#cover magazine#F/I/M²/P#purple#mirror#arles#designer#christian lacroix

0 notes

Photo

ASTOUNDING ARLES

A former 17th century Carmelite convent, the Hotel & Spa Jules César Arles - MGallery by Sofitel is now a hotel of character which combines elements of the 18th century with contemporary art, without forgetting its past.

Having been entirely renovated between late 2013 and early 2014 by the master of fashion Christian Lacroix, the hotel is a real journey through time, where nothing is left to chance. Interplay of perspectives and materials, the building today is a poetic world where design expresses itself. Old stones mix with modern materials and sparingly-added pops of colour are revealed by tricks of the light.

Every detail creates this very particular ambiance, enabling the building to subscribe to an idea of a second home telling a story of life.

#arles#france#christian lacroix#5-star#5-star hotel#boutique hotel#luxury#luxury hotel#luxury holiday#luxury travel#europe#europe all#europe destination

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

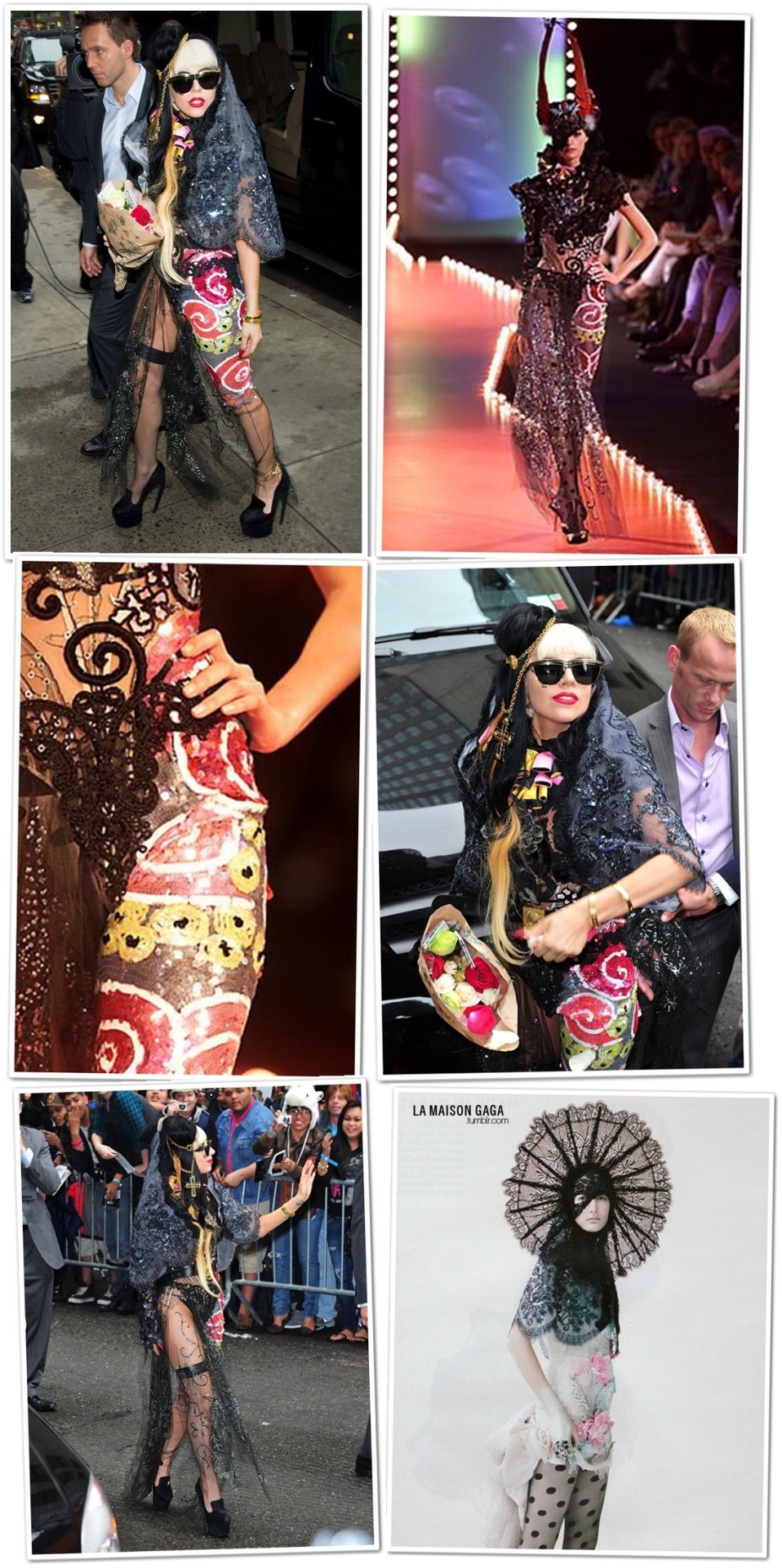

BACK IN TIME: LADY GAGA ROCKS CHRISTIAN LACROIX

Before changing into her wild Viktor & Rolf leather ensemble, Lady Gaga was seen arriving to the Late Show with David Letterman in a whole different look back in May 2011.

The meticulously handmade thousands of beads and sequins hand embroidered mesmerizing jumpsuit with candy-colored neck ruffles and one-sided tulle skirt belongs to one of the strongest collections designed by Christian Lacroix, his Fall/Winter 2001 Haute Couture collection, inspired, among others, by Franco-Spanish traditions of his native Arles.

Her black embroidered lace mantilla with scalloped trim belongs to the same collection.

Another rare Christian Lacroix piece is this black & gold lucite cross chain necklace that she wrapped around her pony tail. She found it at Resurrection Vintage.

Gaga was photographed also wearing the vintage cat-eye shaped frames with gold and black trim by Charme, model 7089. She got them from Vintage Frames Company.

The Italian-American fashionista also wore two different bangles. One of them is the golden Atlas bangle by Tiffany & Co., featuring Roman numerals all around.

Inspired by vintage Art Deco elements, Gaga’s Paloma gold bracelet with precious stones is made by Spanish jewelry heritage brand Nicol’s.

The chunky anklet, which is actually a bracelet, is a vintage Versace piece that was gifted to her by a Japanese fan (similar version pictured).

Black alien-inspired pumps from Mugler’s Fall/Winter 2011 collection provided the finishing touches.

#May 2011#jumpsuits#hats#Christian Lacroix#Resurrection Vintage#jewelry#Tiffany and Co#Versace#Nicols#sunglasses#Charme#Vintage Frames Company#pumps#Mugler

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

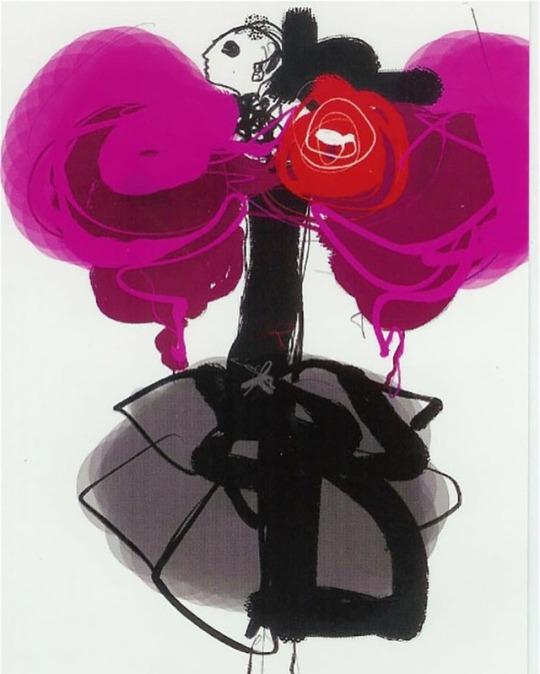

Such vibrancy 💕 /Christian Lacroix sketches/ ✨ Born in Arles in 1951, Bouches-du-Rhône in southern France. At a young age he began sketching historical costumes and fashions. Lacroix graduated from secondary school in 1969 and moved to Montpellier, to study Art History at the University of Montpellier. In 1971, he enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris. While working on a dissertation on dress in French 18th-century painting, Lacroix also pursued a program in museum studies at the École du Louvre. His aspiration during this time was to become a museum curator. It was during this time he met his future wife Françoise Rosenthiel, whom he married in 1974. (at Moscow, Russia) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bs3uKu2hSHm/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1nc26k0g3p5f8

0 notes

Text

See the town in southern France that brings Van Gogh's paintings to life

See the town in southern France that brings Van Gogh’s paintings to life

From the ancient Romans and Van Gogh to haute couture designer Christian Lacroix, the artisans of Arles have helped make the southern French city an architectural and artistic treasure.

Powered by WPeMatico

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

25 Pessoas famosas que conhecemos pelo nome, mas raramente vemos suas fotos

Mesmo não tendo muito interesse em moda, você provavelmente já ouviu falar das grandes marcas do mundo da moda, como Armani, Calvin Klein e Prada. Existem pessoas criativas e inovadoras por trás dessas marcas, mas que não gostam muito dos holofotes. Veja abaixo como são os rostos por trás de marcas mundialmente famosas do mundo da moda.

1 – Stella McCartney

Stella McCartney é uma designer britânica, filha do famoso ex-Beatle Paul McCartney. No entanto, Stella provou ser muito mais do que isso. Ela começou a desenhar suas peças aos 13 anos de idade e hoje é conhecida por suas roupas femininas, para as quais a estilista nunca usa couro ou pele, já que ela é uma ativista dos animais e da ecologia.

2 – Giorgio Armani

Giorgio provavelmente dispensa apresentação. Ele nasceu na Itália e agora é conhecido por suas roupas incríveis e elegantes. Em 2001, ele foi proclamado o melhor designer italiano de todos os tempos.

3 – Kenzo Takada

Kenzō Takada, um lendário designer japonês, que mudou-se para Paris depois de se formar no Bunka Fashion College de Tóquio. Ele então montou uma loja na cidade e seu sucesso começou em 1970. Atualmente, Kenzō é um dos designers mais renomados do mundo.

4 – Roberto Cavalli

Quando Roberto era jovem, ele estudou técnicas de tecelagem. Isso o inspirou a abandonar o colégio e abrir seu próprio negócio na área têxtil, que ganhou fama no mundo da moda. Aos 32 anos, o estilista apresentou sua primeira coleção em Paris, e logo abriu uma boutique em Saint-Tropez. Atualmente seu nome é sinônimo de estilo, glamour e sensualidade.

5 – Tommy Hilfiger

Quando Tommy tinha apenas 20 anos, ele abriu sua própria loja de roupas, mas faliu após 5 anos. Após a falência, mudou-se para Nova York (a capital da moda dos EUA), onde trabalhou para várias marcas. Aos 28 anos, ele criou sua própria empresa de roupas, chamada Tommy Hill. Seis anos depois, ele fundou a Tommy Hilfiger Corporation, que se tornou uma das marcas de moda mais renomadas do mundo.

6 – Alexander Wang

Alexander Wang é um designer americano, conhecido por projetos urbanos e elegantes. Ele nasceu em São Francisco e, aos 18 anos, como muitos outros estilistas, mudou-se para Nova York para participar da Parsons School of Design.

7 – Dolce & Gabbana

Stefano Gabbana e Domenico Dolce se conheceram em Milão em 1980, quando trabalharam para uma marca, e criaram sua própria empresa cinco anos depois. A Dolce & Gabbana tornou-se conhecida pelo seu estilo sensual e sexy, muitas vezes inspirado nos looks clássicos e femininos das mulheres da Sicília.

8 – Vera Wang

Vera Ellen Wang é uma designer de moda americana com ascendência chinesa, conhecida por desenhar lindos vestidos de noiva, principalmente para famosas. Vera Wang nasceu em 1949 e cresceu em Nova York. Excelente patinadora, Vera tentou chegar à equipe olímpica dos EUA e fracassou, e isso a levou a buscar outra paixão – a moda.

9 – Vivienne Westwood

Vivienne Westwood é uma estilista britânica responsável pela moda punk e new wave modernas. Ela se inspirou na moda punk e é conhecida por não ter papas na língua. Vivienne estudou moda na Harrow School of Art, em Londres.

10 – Donna Karan

Donna Karan é uma estilista americana e proprietária das grifes Donna Karan de Nova York e DKNY. Ela nasceu em Queens, Nova York, e depois do ensino médio estudou na Parsons School of Design.

11 – Jean Paul Gaultier

Jean-Paul Gaultier cresceu nos subúrbios de Paris. Quando Jean-Paul era criança, sua avó o apresentou ao mundo da moda. Ele costumava desenhar esboços e enviá-los para os costureiros famosos quando era mais jovem. Felizmente, Pierre Cardin viu o seu talento e ficou tão impressionado que contratou Jean-Paul como seu assistente em 1970.

12 – Manolo Blahnik

Quando Manolo tinha 28 anos, ele começou a escrever em uma coluna sobre calçados na revista Vogue, em Londres. Um ano depois, ele abriu sua própria boutique de calçados com o seu nome. Aos 32 anos, o estilista tornou-se o segundo homem da história a aparecer na capa da Vogue. Agora, os sapatos Manolo Blahnik são cobiçados por celebridades e até mesmo chamados de quinto personagem da série Sex and the City.

13 – Diane Von Furstenberg

Diane von Fürstenberg é uma estilista belga. É considerada umas das mais importantes criadoras de moda dos anos 1970 e 1980, sendo a criadora dos power rings (anéis feitos de pedras grandes) e também do Wrap Dress.

14 – Calvin Klein

Calvin Klein se tornou um grande nome do mundo da moda, sendo sua marca famosa principalmente pelos jeans e roupas íntimas. Além disso, a marca Calvin Klein também produz perfumes e acessórios.

15 – Tom Ford

Tom Ford é um designer de moda americano, diretor de cinema, roteirista e produtor de cinema. Tom passou sua infância nos subúrbios do Texas e depois no Novo México. Ele lançou uma linha de moda masculina, beleza, óculos e acessórios em 2006, que desde então faz bastante sucesso.

16 – Michael Kors

Michael Kors, é um designer conhecido principalmente por suas peças glamourosas, mas atemporais. Sua paixão pelo design surgiu cedo e, aos 5 anos, redesenhou o vestido de casamento de sua mãe para o segundo casamento

17 – Christian Louboutin

Desde muito jovem, Christian adorava fazer sapatos e o fez para casas de moda como Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent e Maud Frizon. Quando ele completou 27 anos, decidiu criar sua própria marca e abriu uma loja. Seu negócio ganhou reconhecimento de celebridades e socialites de Hollywood, que se apaixonaram por seus calçados, fazendo dele um dos mais notáveis designers de calçados da história da moda.

18 – Miuccia Prada

Neta de Mario Prada, Miuccia Bianchi Prada assumiu o negócio da família em 1978. Uma das mulheres mais bem vestidas do mundo (segundo a Forbes), Miuccia é a designer-chefe da marca de luxo Prada e fundadora da sua subsidiária Miu Miu.

19 – Gianni Versace

A mãe de Gianni era costureira, então ele passou a maior parte de sua infância aprendendo a costurar. Gianni abriu sua primeira boutique Versace em 1978 e rapidamente se tornou uma sensação internacional.

20 – Marc Jacobs

Marc Jacobs é o designer-chefe de sua própria marca de moda Marc Jacobs, que é conhecida por seu estilo feminino e às vezes peculiar.

21 – Roland Mouret

Roland Mouret nasceu na França e depois do ensino médio, ele estudou em uma faculdade de moda em Paris por três meses. Mesmo que ele não tivesse algumas habilidades técnicas, isso não o impediu de desenhar suas roupas. Seu grande avanço veio em 2006, quando ele introduziu seu vestido Galaxy em sua coleção de primavera. De repente, tornou-se o vestido do ano e a maioria das celebridades caiu sob o feitiço de Roland. O designer disse mais tarde: “Acho que o meu apelo é entender as mulheres; não se trata apenas de desenhar uma roupa para elas”.

22 – John Galliano

John foi proclamado como um dos maiores estilistas britânicos e foi nomeado quatro vezes como Designer Britânico do Ano.

23 – Thierry Mugler

Thierry Mugler nasceu na França, em 1973, O designer ainda encontra novas e novas ideias, inspiradas em coisas estranhas como insetos, robôs, alienígenas. Além disso, Thierry também é fisiculturista.

24 – Jacquemus

Simon Porte Jacquemus nasceu em 1990 em uma pequena cidade na França, de uma família de agricultores. Quando completou 18 anos, Simon foi para Paris, onde estudou por alguns meses na Escola Superior de Artes e Técnicas de Moda (ESMOD). Dois anos depois, em homenagem à sua falecida mãe, ele criou sua marca Jacquemus – que era o nome de solteira dela.

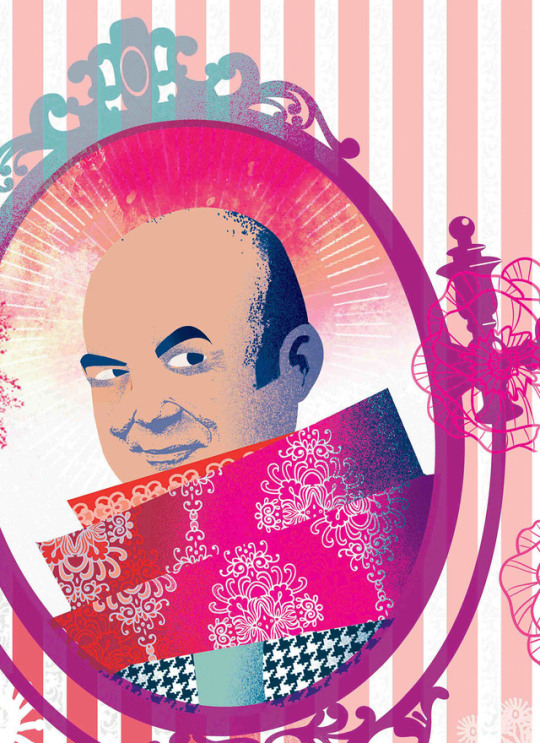

25 – Christian Lacroix (à direita)

Nascido em Arles, na França, Christian queria ser curador de museus. No entanto, ao desenhar fantasias históricas por diversão, ele se apaixonou pela moda e abriu sua própria casa de alta costura em 1975 e começou a criar roupas prontas para vestir 13 anos depois.

Fonte: Bored Panda

O post 25 Pessoas famosas que conhecemos pelo nome, mas raramente vemos suas fotos apareceu primeiro em Tudo Interessante.

Leia aqui a matéria original

O post 25 Pessoas famosas que conhecemos pelo nome, mas raramente vemos suas fotos apareceu primeiro em Tesão News.

source https://tesaonews.com.br/noticia-tesao/25-pessoas-famosas-que-conhecemos-pelo-nome-mas-raramente-vemos-suas-fotos/

0 notes

Text

A Brief History of the Arlesienne Fashion Plates Who Inspired Alessandro Michele’s Cruise Collection

A Brief History of the Arlesienne Fashion Plates Who Inspired Alessandro Michele’s Cruise Collection

[ad_1]

I have been in love with the city of Arles in Provence since the late ’80s when I was invited there by Christian Lacroix, the city’s fashion darling, and his wife and muse, Françoise. In its atmospheric museums, I discovered the work of the local 18th-century artist Antoine Raspal, and examples of the Arlesienne costumes that so inspired Lacroix, with their fichu collars, fitted bodices,…

View On WordPress

#Alessandro#Arlesienne#Collection#cruise#fashion#history#inspired#Micheles#mobileAppReadyTrue#Plates#Runway

0 notes

Photo

★ VLINDERS ★ van Christian Lacroix Prachtig porseleinen bord met kleurrijke vlinders uit de serie: Butterfly Parade. Met details van goud en platinum. Een parade van reële en imaginaire vlinders vliegen over het porselein, met opmerkelijke driedimensionale effecten. *check voor prijzen en mmer info onze webshop --> http://www.studiodewinkel.nl/wonen/?_globalsearch=vlinders ★ BUTTERFLIES ★ of designer Christian Lacroix Beautiful porcelain plate with lots of butterflies from the serie: Butterfly Parade. Enhanced with gold and platinium. A parade of real and imaginary butterflies flying over the pieces, with notable three-dimensional effects. *check for price and more info our webshop --> http://www.studiodewinkel.com/wonen/?_globalsearch=butterflies #christianlacroix #porcelain #designer #wallplate #wallobject #design #porselein #vlinders #arles #butterfly #france

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Vintage Designer Handbags Online | Vintage Preowned Chanel Luxury Designer Brands Bags & Accessories

New Post has been published on http://vintagedesignerhandbagsonline.com/christian-lacroix-the-heir-to-yves-st-laurent-fashion-archive-1987-fashion/

Christian Lacroix, the heir to Yves St Laurent – fashion archive, 1987 | Fashion

The Observer

In August 1961, Yves Saint Laurent declared, ‘Haute couture cannot be modernised.’ It was a bold statement and a sign of the times, for at the dawn of the Sixties it seemed obvious that mass-produced, ready-to-wear fashion was the way forward in a new, young-spirited, democratic age. Haute couture had become an anachronism, the province of the rich, the stuffy and the middle-aged – and would never again hold sway over the world of fashion.

In the late Eighties, Christian Lacroix has overturned Saint Laurent’s prophecy in a manner that has sent the international fashion coterie into an ecstasy of hyperbole. From the moment Lacroix took over designing the couture collection for the ailing house of Patou in 1981, his ostentatious, elaborate, vividly coloured and vastly expensive creations began to make waves.

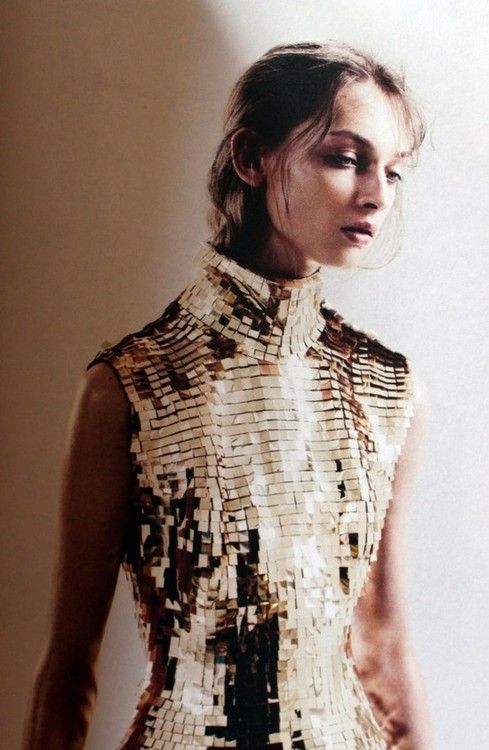

Lacroix reinvented the trapeze line and the bubble skirts Saint Laurent had pioneered in the Fifties, but this was no mere re-run of the past. Lacroix’s women were baby dolls in frou-frou petticoats, his silhouette a shoulderless cone, which made sitting down impossible. Giving full rein to the dying couture intricacies of beading, embroidery and all manner of fancy-work – and using the most extravagant of materials – he piled effect upon effect, with no heed to caution or good taste. Tales of mink dyed green and violet, of pompoms, quilting, patchwork, tassels and exuberant clashing prints drew increasing numbers of onlookers to the house of Patou, many biding their time to decide whether he was merely a vulgar clown, or truly a fledgling genius.

By January 1986, the matter was settled for them. The announcement that Lacroix had been backed by £50 million from Dior’s parent Financière Agache, confirmed him as a force to be reckoned with. The deal meant not merely that Lacroix would have his own couture salon in which to produce hand-made dresses for private customers, but that a potentially highly lucrative ready-to-wear line would follow, as well as the opportunity for any number of money-spinning licensing deals in the way of perfume, sunglasses, shoes, handbags, and so on.

A model displays a styled Spanish ensemble, black jacket embroidered over a balloon-dress and Castilian hat for Christian Lacroix 1987/88 Fall/Winter haute-couture collection. Photograph: Pierre Guillaud/AFP/Getty Images

At the unveiling of his first own label collection last July, fashion editors, swept up in the maelstrom of publicity, stood on chairs to weep and throw flowers at the newly-crowned king (they did much the same last week). Had Parisian couturiers in their dark years ever dreamed of the coming of a saviour, these scenes would surely have surpassed their wildest fantasies. Lacroix, it seems, is the biggest news in Paris fashion since the emergence of Yves Saint Laurent himself, some 30 years ago.

Lacroix is now a French national hero, and very much an international property. Until yesterday every high fashion retailer in London was claiming to be in discussion with the house of Lacroix for exclusive rights to sell his ready-to-wear line, which will become available in March. Sidney and Joan Burstein of Browns of South Molton Street, Roberto Devorik of Regine, Peder Bertelsen of Aguecheek, and Claire Stubbs of Harrods were locked in fierce competition to win the contract that will confer the ultimate prestige upon their shops.

The man at the centre of all this attention is, in many ways, a surprise. At 37, Christian Lacroix is not naturally a distinguished figure, but he is certainly a distinctive one in his Ralph Lauren suits, bright shirts, loud ties and dandyish pocket handkerchiefs. All who meet him agree: he is hugely polite and considerate, keen to listen and well informed. After interviews, he is in the habit of sending round charming, hand-written thank-you notes on recycled paper. Everyone loves him: his wife and muse, Françoise Rosenthiel, his PR man and friend, Jean-Jacques Picart, the skilled workers who moved with him from Patou. Even the models are said to adore him, lending their professional smiles an extra brilliance as they ply his catwalk.

Lacroix is the son of an engineer from Arles. Family legend has it that, when his grandfather asked him, aged four, what he wanted to be when he grew up, he replied, ‘Christian Dior.’ Brought up in the Camargue, to which he is sentimentally attached, and to which he dedicated his first collection, he studied the history of art and costume at Montpelier University. He worked apprenticeships at Hermès and Guy Paulin, where he met Francoise and Picart in 1978, before signing up with Patou. They are a jokey and intimate team, sharing ideas, inspiration and a keen interest in London’s young fashion and furniture designers. Lacroix, it is said, prefers to mix with writers and artists rather than fashion people, and back home in Arles he is just plain Christian, who keeps up with his old friends as if nothing had happened.

Continue reading

How to access the Guardian and Observer digital archive

Source link

0 notes

Photo

DESIGNER ARLES

The Hotel & Spa Jules César Arles - MGallery by Sofitel in Arles was completely renovated and decorated by Christian Lacroix in 2014. Located in the Arles city center, you will experience true 5-star comfort. Formerly a 17th century Carmelitas convent this hotel offers 52 rooms, including 11 suites, a gourmet restaurant with terrace, outdoor heated pool close to the cloister gardens (open seasonally) and a registered CINQ MONDES spa. Arles is an ideal layover stop with its Roman architecture classified by UNESCO as a World Heritage site

#arles#france#christian lacroix#5-star#5-star hotel#luxury#luxury hotel#luxury travel#luxury vacation#europe#europe all#europe destination

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

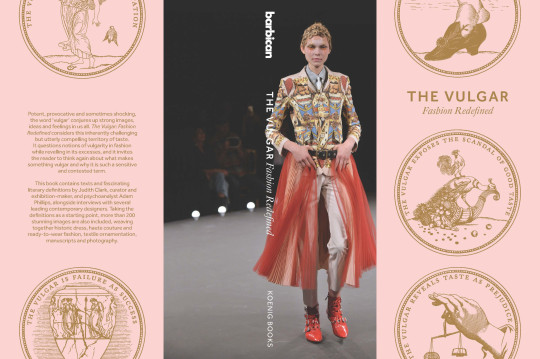

TEMPTED BY VULGARITY by Hilary Reid

from Salmagundi, Summer 2017

“The Vulgar” was the focus of an unlikely fashion exhibition mounted at the Barbican in London last October. The creation of fashion historian Judith Clark and the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, the exhibition was clearly intended to challenge, or “interrogate,” a wide range of assumptions and clichés. Though many of the fashions displayed at the Barbican were beautiful, others notable for extravagance, or wit, or elegance, several were selected principally to raise questions about the meaning of originality, or our addiction to so-called good taste. Fashion was, to be sure, front and center throughout the very extensive Barbican assemblage, and yet fashion itself seemed but a single, convenient representation of the ideas and puzzlements at hand. The focus on “vulgarity” was designed to send viewers through the Barbican with tantalizing questions in mind—questions about taste, to be sure, but also about class, sensibility, condescension, ostentation and a host of other preoccupations. Those uneasy thoughts were provoked not only by the objects on display but by the wall texts and other prompts composed to accompany them. To read a characteristic essay by Adam Phillips, on any subject, is always to feel that your sense of things has been enlarged and complicated, and thus to read him on fashion—especially in the first-rate catalogue* prepared for the show—is to discover that really you have only begun to take possession of something you supposed you’d mastered before.

But then there were many surprises on offer at the Barbican. Surprising, to me at any rate, was the inclusion of several pieces of clothing—this was, after all, a show subtitled “Fashion Redefined”—that did not in any sense confirm what I had previously associated with “the vulgar.” Take, for instance, a conservative, floral, Provencal, traditional jacket, or droulet, from 1790, or a prim and ultra-feminine 1950s Christian Dior evening dress, or a delicate French Agentan linen needle lace collar from the 1740s. A museum-goer landing in sections of the show featuring such items would be apt to doubt that they had anything to do with vulgarity. No doubt an aspect of the experience shared by pretty much anyone confronted by the sheer, sometimes dazzling variety of objects assembled for “The Vulgar” was the nagging thought that the term itself is no longer quite available to us in the way it once was. Even to invoke the term in a casual way is to acknowledge that it is at once a sort of old-fashioned term, even a cliché, nowadays rarely used, and yet somehow also fraught, in several respects uncomfortable.

In part, this may have to do with the fact that the exhibition encourages viewers to loosen up, chill out, and calm down about so-called good taste. After all, the show is informed by the observation that vulgarity is in the eye of the beholder, that it is not an intrinsic property of objects. By juxtaposing certain high fashion items incorporating conventionally outré (or vulgar) features with items lacking obvious signs of vulgarity, Judith Clark forced this viewer at least to wonder about the roots of her own presumptions and aversions, and of course Phillips’s wryly brilliant and often counterintuitive definitions of vulgarity (to which I’ll return in a moment) made a persuasive case for opening up one’s sense of what is and is not tasteful or delectable. When I entered the Barbican, I thought of vulgarity as something to be avoided at all costs—louche, common, gross. By the time I left the museum, I was surprised to find that vulgarity, only somewhat reconceived, was something I was tempted to embrace.

* * *

In his catalog essay on “The Vulgar,” Phillips references an article in the style section of The Guardian, in which fashion editor Hadley Freeman refers to the word “vulgar” as “overused-to-the-point-of-cliché.” In response, Phillips writes:

There are reasons why we might want to overuse a word to the point of cliché: to make something that is contentious appear self-evident; to make a club out of fellow-users; to fortify ourselves with collusive like-mindedness; to conceal the violence of our taste. We make words into clichés—take them to be clichés, or habits—when we don’t want to think about them.

One way to salvage a term from cliché is to reinterpret it. In preparation for the Barbican show, Phillips conceived eleven new definitions of vulgarity, from “Common” and “Too Popular” to “Impossible Ambition” and “Puritan.” In re-describing and contextualizing vulgarity in this way, Phillips suggests that it is not as opaque or unavailable as we might think. Though “vulgar” has often been used as a conversation-stopper—“she is so vulgar,” someone might say as a way to dismiss someone without further explanation—the term may be more richly deployed in an effort to examine one’s own prejudices, or to note, in an ironic way, how condescension is often an expression of unearned superiority.

In speaking of “The Vulgar Tongue,” Phillips invokes the 17th century sense of the term, which entails simply “what is common,” belonging to “the people.” He writes:

The vulgar tongue is the common language, the native language, the language ‘we’ speak. It is local and indigenous, like national or traditional dress. So, why would we be suspicious of, or amused by, a language everyone could speak, and what would we be suspicious of? Vulgarity amuses us because it makes us uneasy. And it makes us suspicious because it is too close to home; it reveals an embarrassment we are trying to avoid.

Here Phillips asks why we might be suspicious of our own “vulgar tongue,” or commonness, our decidedly “popular” appetites, and describes the vulgar tongue as that which we believe “needs to be refined.” In this sense, even the floral Provencal droulet , whatever its rich tones and intricate embroidery, its obviously refined craftsmanship and use of traditional techniques, may betray its status as a kind of provincial person’s dress. To me, the assorted 19th century Provencal pieces were not only “beautiful” but museum-worthy, old-world, to my eye in no way common or inferior. But within the context of “The Vulgar” we were instructed, as it were, to regard such items as just the kinds of things that people concerned with their own status would shirk for the new and the modern, so long as “new” and “modern” signified for those persons “refinement.” In the exhibition, Clark juxtaposed the Provencal pieces with 1980s styles by Christian Lacroix, a designer who has been explicit about the influence on his designs of traditional styles associated with Arles, his birthplace in the South of France.

But Lacroix has also been explicit about the influence of vulgarity in his work. In an interview included in the exhibition catalog, Lacroix states, “The vulgar is the source of everything I do, because I can’t help designing from something existing, something simple, and something with a deep soul, and something belonging to my guts somewhere.” Lacroix’s pieces in “The Vulgar” incorporate large lace patterns, oversize bibs, and big, flat-rimmed sunhats, all obvious references to an unmistakably provincial past. The enlarged, somewhat off-kilter, and even emphatic renditions of these pieces seem to me to be a critique of our willingness to “refine” the common, or vulgar, styles of our ancestors. They demonstrate a certain knowingness on Lacroix’s part: he knows that these are old-fashioned elements, tokens of a past which he carries in his “guts,” so that, instead of concealing that past, Lacroix’s designs suggest that we forthrightly embrace it and see what it reveals about the present.

In a different section of the exhibition entitled “Extreme Bodies,” Phillips notes that “where there is pleasure, there is always the temptation of vulgarity…Sometimes we fear that vulgar pleasures are the real pleasures—the ones we need to disdain and distance ourselves from, as though the vulgar is a version of the forbidden.” Presumably Phillips would include, under “pleasure,” a whole range of activities, from sex to flamboyant displays of wealth or excess, which, at one time or another, have been described as vulgar. For “Extreme Bodies,” Clark selected clothing that demonstrates how the body has been (or might be) considered vulgar depending on how much or how little is shown. In this section, we find a strappy leather bondage bodysuit and a white chiffon bodysuit, both by Pam Hogg—who, Clark notes in her captions, often represents fetishism and sexuality in her runway shows—as well as a short dress by André Courrèges, who, along with Mary Quant, was an early proponent of the miniskirt. A1964 Rudi Gernreich bathing suit, with bottoms that went up to the waist and a top comprised of two straps that would go between, but not cover, the breasts, was displayed nearby. A person wearing any of the three getups would certainly show some skin—but while the minidress and even the topless bathing suit now seem relatively tame, even mainstream, the bodysuits still fall within the realm of the “unwearable,” or, to some, the vulgar.

As I walked through the halls of the Barbican, I felt a deep urge to wear some of these “unwearable” pieces. What becomes of me if I put on Manolo Blahnik’s thigh-high denim boots encrusted in rhinestones—the kind of shoes that would give my well-mannered grandmother a heart attack if she saw me wearing them—or, better yet, that strappy black leather bondage bodysuit by Pam Hogg? How do I see myself if I dare to wear Gareth Pugh’s top made entirely of gold coins, or one of the most enticing pieces in the show, a pair of Gucci loafers fabricated in long amber-colored goat hair, only identifiable as Gucci loafers by their signature horse bit detail?

This fantasy—or impulse—calls to mind a passage in The Language of Clothes, in which Alison Laurie expands upon Roland Barthes’ suggestion that theatrical dress is a kind of writing, in which the sign is the foundational element. Laurie refers to the components of a style as “words.” “‘Vulgar words,’ in dress,” she writes, “give emphasis and get immediate attention in almost any circumstances, just as they do in speech…They are most effective if people already think of you as being neatly dressed, just as the curses of well-spoken persons count for more than those of the customarily foul-mouthed.” I read and reread this formulation and can’t help thinking of myself as one of those customarily well-spoken or at least cautious persons who might well wish, now and then, for something strong, even harsh, to provide “emphasis.” I’ve always loved, mainly dreamed about, a shocking pair of bedazzled stilettos or a flashy top, but you will more often find me in flats and a turtleneck. Though the items in “The Vulgar” are not ones I would ordinarily wear, the temptation to make myself “vulgar,” just to try it out, is strong. We know, of course, that putting on a very short dress and very sharp high heels can be a strong visual way to command sex. But what about putting on something funny? Or something that looks like a work of art? “The Vulgar” demonstrates that vulgarity can be as various and unpredictable as beauty—that when we embrace the humor and smarts of it, when we brandish it occasionally with abandon, we have in our reach a powerful aesthetic that can challenge, confuse, attract, or repel.

* * *

A question that remained with me after viewing “The Vulgar” is whether or not the distinction between high and low fashion is still relevant today. So much of what might traditionally be considered low—the thigh-high boots, the over-the-top proportions, even Moschino’s bright pink plastic pair of blow-up lips worn as a hat—is, if not commonly worn, a common enough sight. Last spring, several designers created sheer tops and dresses that models wore without bras, so that their nipples were on display, and sheer pants and skirts that displayed the model’s undergarments. These looks are no longer shocking, and only a very unhip person would think to declare such garments vulgar. In fact, anyone offended or distressed by sheer womenswear might well find himself under fire for failing to respect a woman’s right to display her body as she chooses. As Laurie writes in The Language of Dress, “In speech, slang terms and vulgarities may eventually become respectable dictionary words; the same thing is true of colloquial and vulgar fashions.”

There is one item that strikes me as particularly vulgar in 2017: a bright red “Make America Great Again” hat. Style aside, the red cap is so potently vulgar that I would not wear even the parody hats put out by the Hillary Clinton campaign (hats that read “I have a very good brain”) or the “Make America Read Again” hats sold in the Strand Bookstore in New York. “The Vulgar” opened at the Barbican in October 2016, four months after Brexit and a month before the election of Donald Trump in the United States. The October morning that I went to see “The Vulgar,” I received a breaking news email from The New York Times. The subject line read: “Donald Trump brags in vulgar terms about groping women in a 2005 recording, saying, ‘When you’re a star they let you do it.’” Both Brexit and Trump’s election have widely been described as reflections of the “people speaking” (though the popular vote totals in this country suggest otherwise). And yet it is hard not to think again of the old 17th century definition of vulgarity as “common” or merely “popular.” Months after seeing “The Vulgar,” I’m struck by the extraordinary prescience the theme has taken on. The vital vulgarity presented in the halls of the Barbican Centre is one I am eager to embrace, and yet a different strain of pungent vulgarity has taken command of things at the White House.

“The Vulgar” exhibition closed in February, a few weeks after the inauguration of Donald Trump and a weeks before the Fall 2017 fashion weeks took place in New York, Paris, London, and Milan. Politics were on the mind of several designers: Prabal Gurung sent models down the runway in t-shirts that read “The Future is Female,” Missoni models wore the pink knit pussyhats that have become emblematic of the Women’s March, and Public School opened their runway show with a model in a bright red “Make America New York” hat. These looks were in protest of Trump, of course, and one can imagine certain viewers feeling assured that these designers were taking a public stand against the president. Still, it does not take much of a cynic to feel that these items were included in the runway show because feminism and activism are, at the moment, popular and profitable. The designers took items of protest clothing that already existed—pink hats, t-shirts with feminist slogans—slapped on their brand name and sent them down the runway. They simultaneously sold assurance of their political awareness (and correctness) and, of course, a name brand product.

These items do not strike me as sufficient expressions, let alone critiques, of our vulgar moment. If designers intend to create styles that engage with a vulgar political moment, they would do well to look at the modes of expressing vulgarity demonstrated in “The Vulgar.” In his catalog essay, Phillips writes, “Through performance, through styling, through caricature, through fashion: vulgarity is a way of thinking about the idea of the real thing. If there is something supposedly unreal about the vulgar—if vulgarity is a kind of pretence—then it is possible to be real.” While it is too early to tell exactly what the “real” might look like in the often unreal-seeming times of Trump, one fashion collective (that was not included in “The Vulgar,” but would have fit right in) provides clues. The styles put forth by Vetements—a brand known for its confounding, challenging, often ugly clothing, and whose name simply translates as “clothing”—caricature the “real thing,” as it were. What is the “real thing” for Vetements? Usually, it is the most common stuff of everyday life. Take, for instance a Vetements’ t-shirt with the DHL shipping company logo emblazoned on it, or a pair of redesigned Champion sweatpants, or a banal grid-patterned men’s shirt that is a bit rumpled and ill-fitted, worn with the kind of brown leather belt commonly found on businessmen, but in an exaggerated length, so that part of the belt almost reaches the floor. These pieces are inspired by items associated with everywhere and nowhere; they are a kind of mirror held up to the stuff that so commonly surrounds us that we hardly see it. The Vetement garments draw our attention to the ubiquitous ephemera of the present—the clothes we wear to work, the clothes we wear to relax, the logo of a company we use to ship things to various places—, a present that feels oddly accelerated and uncertain.

The peculiar oddity and uncertainty definitely call to mind the strain of self-knowing vulgarity articulated in “The Vulgar.” Can clothing communicate anger? This clothing can, and the anger feels relevant to the present moment. In The Telegraph, Kate Finnegan writes, “[A] snarly attitude… emerges at a Vetements show…The models race along the catwalk at an amphetamine-fuelled pace, deliberately unglamorous. There was no ambiguity about the sweatshirt for next season that proclaimed: You Fuck’n Asshole.” In an interview with Vetements designer Demna Gvalasia, Finnegan brings up the seemingly angry clothing and asks about “inspiration.” The design collective is based in Paris, and Finnegan suggests that, perhaps, the violent events at the Bataclan and Charlie Hebdo offices might somehow have influenced these styles. At first Gvasalia denies that the attacks were on his mind, but then states: “I remember the morning after walking through Paris and it was zombie land. Maybe the anger somehow was present in our last show, yeah, but it was totally subconscious. In the same way, before Charlie Hebdo we had made all these security and police sweatshirts. Something is in the air, I guess. It’s strange. At a certain time you feel certain things and then it filters through to the world.”

The idea that the mood of a time affects fashion is not new: it has long been said, for instance, that when markets go up skirt hems get shorter, and when markets fall, skirt hems are longer. In an article in The Guardian, design critic Alice Rawsthorn answered the question “Is fashion a true art form?” by stating, “Fashion rarely expresses more than the headlines of history.” It seems to me that Rawsthorn’s answer understates what fashion can do, but still the pieces in “The Vulgar,” and pieces like those put forth by designers like Gvasalia, do, suddenly, reflect the current headlines of history: those of impossible ambition, excess, the rise of the common and popular. But they express more than the headlines, too—they offer a critique, a way to articulate vulgarity that transcends the ugliness of our moment. Perhaps now, when we are forced to reckon with a kind of vulgarity beyond any we have seen in recent history, we can look to the artful vulgarity in “The Vulgar,” a kind that laughs at and knows itself—one that is not unrelated to irony, a powerful artistic tool of protest.

0 notes

Text

Christian Lacroix a fashion impresario

Christian Lacroix a fashion impresario

Child and early life Christian Lacroix was born in 1951 Arles, France. He was the adored son of a family of engineers. His father and grandmother were very interested in fashion and style. So that he grew up in his family and the fashion ideas were growing with him. He studied art at the Paul Valery University, in Montpelier then he moved to study in Sorbonne in Paris from 1970 to 1972. In 1972,…

View On WordPress

#Advice experts#body care routine#Botox#business magazine#business man#celebrities news#Christian Lacroix#couture and ready-to-wear house#daily quotes#daily style#decoration ideas#diet meal plan#diet pills#events near me#EXOTIC#eye makeup tips#Fashion Advice#fashion designer#fashion magazine#fashion shows#lebanese magazine#lifestyle magazine#makeup tutorial#men fashion trends#men style#most expensive gadgets#news update#online magazine#plastic surgery#real estate magazine

0 notes

Photo

★ Porseleinen bord van designer Christian Lacroix.

De Franse mode ontwerper. Geïnspireerd op de monumenten uit de 19e eeuwse franse stad Arles. Met details van goud en platinum. Een parade van reële en imaginaire vlinders die vliegen over het porselein, met opmerkelijke driedimensionale effecten. Mooi als kunstwerkje voor aan de wand

*check voor prijs & meer info onze webshop–> http://www.studiodewinkel.nl/wonen/?_globalsearch=lacroix

★ Beautiful porcelain plate with lots of butterflies from the serie: Butterfly Parade, of the great designer Christian Lacroix. Enhanced with gold and platinium. A parade of real and imaginary butterflies flying over the pieces, with notable three-dimensional effects.

*Check for price and more info our international webshop–> http://www.studiodewinkel.com/wonen/?_globalsearch=lacroix

0 notes