#A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

Text

North American beaver

By: New York Zoological Society

From: A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

1913

#beaver#castorimorph#rodent#mammal#1913#1910s#New York Zoological Society#A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

195 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🦌 A history of land mammals in the western hemisphere New York, The MacMillan Company, 1913.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life restoration of Agriochoerus antiquus, illustrated by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913

from A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere, by William B. Scott

#i couldn't find this uploaded here & i really like this art so hi#agriochoerus antiquus#agriochoerus#tylopoda#artiodactyla#uploads#art#vintage art

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hedges and how to lay 'em.

(weird first post, I found these photos on my phone and wanted to write something. Sorry if my formatting repulses you- I'm new around these parts, my grammar will be bad coz tired. This guide is only to spark the imagination, please consult a variety of sources before carrying out a task such as this)

Hedges. Not the planted rows Buxus or Leylandii that many in Western Europe have become accustomed to as the staple boundary, I'm talking about the old fashioned, stock boundary hedge.

Tools and equipment

PPE, including waterproof clothing and acceptable footwear.

A billhook or hatchet

A pruning saw

Welding gauntlets

First of all we need to lay some basic principles out. Angiosperm trees can heal themselves quite well in funny ways that make them grow in strange ways, case in point 👇

(Credit: Gardener's path)

As long as layer of various plant based plumbing, xylem and phloem, remains a it can survive an injury such as this one 👇 that I made,

(Sorry the photo is crap, my phone camera isn't great).

Why did I do this? Am I a sick, twisted motherfucker who likes to torture trees? No. Well sometimes on a Saturday evening with consent from all parties, but this my friends is the starting move to laying a hedge. (Note, this should be done when the sap isn't flowing, my preference is January to February, but can be carried out from October to March in the northern hemisphere).

Individual trees on a bank in a row are referred to as pleachers. These require a 45 (ish) degree cut to be made three quarters of the way through the stem. It should then be bent over👇

(Credit: Devon rural skills hub)

This pleacher, if not the first, can be woven into the rest, wear gloves for the love of God almighty. This is an intricate job, a neat hedge should have very little lean and brush should preferably be concentrated in gaps. Cutting the pleacher will leave a pointed wedge of wood at the base of the stem, called a spar, this can impale someone if not cut off so please do.

This is the completed hedge, which is laid in the Glamorgan style.

The trees that make up the hedge will grow into a thick, tall, living barrier.

Hedges must be relaid over generations, and soon enough I'll have a video detailing how to plant a hedgerow.

History

Hedgerows were invented by John Hedge and his husband Hugh Row in 1755...oh no that's my rural history fanfic. Hedges were actually invented by, well actually we don't know. I've heard it said that they've cropped up in the fertile crescent and ancient Rome. My personal theory is that they are a Neolithic or earlier invention which resulted from a failed coppicing attempt (coppicing post coming to a Tumblr blog near you) the individual who happened to do it may have discovered that the tree was still alive and thus the possibilities of tree shaping were extended to barriers.

Now, as an ancom who decries attempts to stifle the rights of the proletariat, I would be remiss in informing you of one important part of hedge history: the enclosure of the commons. Common land formerly was land for people to graze stock, pannage pigs, forage, hunt and collect firewood. The inclosure act of 1773 allowed private landowners to close common off from the commoners thus creating starvation. And it was all done with hedges, eco-friendly opression of the working class! Yaaaaay!

The importance of hedgerows.

Hang on, you may think to yourself, eco-friendly? How is savaging trees eco-friendly? Good question, dear reader. For a number of reasons;

The regrowth of trees means no loss of fruit or flowers in the long run, thus providing food resources to animals.

Shelter is provided to herps, inverts, nesting birds and small mammals through a diverse branch structure.

The general damp and dim conditions provides a safe haven for bryophytes and fungi.

The hedgebank is a bread and butter to the burrowing animal. Foxes, badgers and rabbits all frequently use hedgebank as the entrance to their dens, setts and warrens.

They act as wildlife corridors for animals to travel from habitat to habitat, thereby helping to combat habitat fragmentation.

Hedgerows in Wales have declined 50% since the second world war and the push to mechanise agriculture. 60% of our current hedgerows are in a substandard condition.

There is a human benefit too, and it isn't just the confinement of livestock.

My maternal family are South Welsh rural folk: foresters, shepherds and the like. My paternal family are Romanichal, who lived a nomadic life in former days. Both have one thing in common: life without the hedgerow that provided fruit and meat would have been a damn site much harder than what it already was.

Therefore I advocate the hedge not only to preserve wildlife but also to provide ample wild fruits (though I wouldn't recommend crab apples to eat, other trees like bullaces and medlars are excellent) and meat for the poorer rural working class, the ever increasing rural homeless population and whomever else needs it.

DISCLAIMER!!!!

I haven't covered everything here, so if you don't look up any other sources you'll probably bugger up somewhere. Please do your homework and make sure you don't injure yourself, or potentially harm nature.

#conservation#rural#rural skills#country skills#cottagecore#solarpunk#wildlife#fair shares#permaculture#livestock#don't sue me if you try this and something goes wrong please#hedgelaying#hedgerow#countryside management#countryside#gardening

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 Beautiful and Rare Species Found Only in Australia

The supercontinent of Gondwana split 180 million years ago. What would become Australia and Antarctica were part of a breakaway landmass from that breakup. Australia had completely separated by the time it travelled north on its own 30 million years ago. Since then, modifications to the land’s climate and physical isolation from the rest of the world have contributed to the development of Australia’s distinctive flora and fauna. Australia is the only place in the world where more than 80% of our flora, animals, reptiles, and frogs can be found.

About one million different native animal species can be found in Australia.

More than 80% of the country’s mammals, reptiles, and frogs, as well as the majority of its freshwater fish and 70% of its bird species, are exclusive to the Australian natural environment.

140 species of marsupials, such as kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, and the Tasmanian Devil, which is currently only found in Tasmania, are known as rare animals in Australia The dingo is the largest carnivorous mammal native to Australia and a wild dog.

About half of the 828 bird species found in Australia are unique to the country, with the huge, nearly two-meter-tall flightless emu being the most well-known.

Waterbirds, seabirds, and birds that live in open woodlands and forests all abound in Australia, including black swans, fairy penguins, kookaburras, and lyrebirds. Australia is home to 55 different species of colourful parrots, as well as a stunning array of cockatoos, rosellas, lorikeets, parakeets, and budgerigars.

More poisonous snake species, namely 21 of the 25 deadliest species, as well as two types of crocodiles, one saltwater and one freshwater, may be found in Australia than on any other continent.

The UNESCO World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef, which is the biggest coral reef system in the world, is also located in Australia. With our Exploring Our Ocean course, you may learn more about marine environments.

The predatory great white shark, which can reach a length of six metres, the enormous whale shark, which can grow to a length of 12 metres, and the box jellyfish, one of the world’s most venomous creatures are among the distinctive marine species.

Kangaroos, dingos, wallabies, wombats, and, of course, koalas, platypus, and echidnas are just a few of the well-known Australian wildlife. However, there is still a great deal that is unknown about the native creatures of Australia. In this article, we’ll look at 9 of the most unique animal species that are considered rare animals in Australia.

Why are Australian animals so unique?

Since Australia is geographically isolated in the southern hemisphere and is known as “The Land Down Under,” many of its animals are unique to Australia.

Around 250 million years ago, the Earth consisted of simply one enormous supercontinent called Pangaea, according to evolutionary history and fossil evidence.

After around 50 million years, this supercontinent split into the continents Laurasia and Gondwana. Monotremes and marsupials dominated the region of tropical forests in Gondwana at the time of this split, whereas placental mammals originated in Laurasia.

After thereafter, in the Jurassic Period, 180 million years ago, the western part of Gondwana, which comprised Africa and South America, split off from the eastern half, which contained Madagascar, India, Australia, and Antarctica. 40 million years later, India gradually broke away from Australia and Antarctica, forming the Indian Ocean. Australia and Antarctica slowly drifted to the south, where they were surrounded by immense oceans and cut off from the rest of the world.

Australia and Antarctica ultimately split apart 50 million years ago. Its environment changed as it moved away from the southern arctic zone, becoming warmer and dryer, and new animal species emerged and took over the landscape.

Eventually, monotremes and marsupials took over as the main mammals in Australia due to their less demanding reproductive systems and greater suitability for this new climate.

The original inhabitants of the Australian landmass no longer interacted with species from other continents, thus they continued to develop on their own. Australian native animals are distinctive from those found elsewhere in the globe because of their distinct evolution, which has produced several odd Australian animals.

Fitzroy River Turtle

Rheodytes leukops, a species of turtle from the Rheodytes genus, lives in the Fitzroy River. The other species in that genus, Rheogytes devisi, has long since gone extinct, leaving only them as the remaining species. In Queensland, Australia’s Fitzroy River and its tributaries are where you can find them.

Fitzroy River turtles spend roughly 21 days submerged. They are remarkably adaptable creatures. The other species of their genus is extinct, leaving only these critters as survivors. The extinct species was known by the name “Rheodytes devisi”. September to October is the time when they lay their eggs.

These turtles are classified as Vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. Because of habitat degradation, predators, and population decrease, they are classified as Vulnerable by IUCN. These turtles are frequently attacked, along with their nests, by foxes, pigs, and goannas.

Because predators frequently attack and totally destroy their nest, there are no surviving hatchlings left, which is a major factor in their Vulnerable conservation status. Its population growth is challenging for this species because of this.

To get the most out of their toe daggers, cassowaries can jump feet first, so their claws can slash downward in mid-air towards their target.

Australian Southern Cassowary

This bird, which descended from dinosaurs, has been designated as the “most hazardous bird on Earth.” Most human attacks in which victims are kicked, shoved, jumped on, and headbutted are motivated by the need to provide food for the bird. Their 12-centimeter middle claw functions as a dagger and may cause significant harm.

Be on the lookout for the elusive cassowary if you happen to be in Tropical North Queensland. It’s a big, colourful bird that has a prehistoric appearance, if that answers your question. The cassowary may reach a height of 180 cm and often weighs 60 kg. With its distinctive appearance, the cassowary is simple to identify. Especially its blue neck and the helmet-shaped protrusion on its head.

They’re great sprinters too, with a top running speed of 50 km/h through dense forest. Not only that, they’re good swimmers, with the ability to cross wide rivers and swim in the sea. That’s one animal you don’t want to be chased by!

Saltwater Crocodile

It is the largest reptile in the world, with a known maximum weight of over 1000 kg, and has the strongest bite of any species. This endangered species mostly consumes small reptiles, turtles, fish, wading birds, wild pigs, and livestock including cattle and horses.

Did you know? A crocodile cannot sweat, so instead, it relies on the process of thermoregulation to control its body temperature. To avoid overheating, it will either go into the water or lie still with jaws agape, allowing cool air to circulate over the skin in its mouth. That’s why you often see them happily basking in the sun with their mouths wide open. This process is crucial for many bodily functions including digestion and movement.

Mistletoebird

The little Mistletoebird, often called the Australian Flowerpecker, is the sole member of the Dicaeidae family of flowerpeckers that lives in Australia. Males have a bright red throat and chest, a white belly with a central dark streak, and a bright red undertail in addition to having a glossy blue-black head, wings, and upperparts. Females have a pale crimson undertail and a belly streaked with the grey that is white above. Young birds are female-like, but whiter and with an orange-coloured bill as opposed to a dark one. These birds fly quickly and erratically, alone or in couples, typically high in or above the canopy.

To its diet of mistletoe berries, the mistletoebird has developed a strong adaptation. The rudimentary digestive system it has allows it to quickly process the berries, breaking down the fleshy outer sections and excreting the sticky seeds onto branches. It lacks the muscular gizzard (food-grinding organ) of other birds. After then, the seed might quickly grow into a new plant. The mistletoebird does this to guarantee a steady supply of its primary meal. In order to feed its young, it will also catch insects.

The mistletoebird is widespread over mainland Australia and can be found wherever mistletoe is present. It plays a significant role in the spread of this plant species. Eastern Indonesia and Papua New Guinea also contain it.

Tasmanian Devil

The Tasmanian Devil is listed as an endangered species in Australia. Their tail, where they store fat, may hold up to 40% of their body weight per day, thus you can gauge their health by the size of it! Although they don’t have the same terrifying appearance as other creatures in Australia, they have a bite that is so strong that it may easily break bones.

These creatures are worth viewing, despite the fact that some people may find them cute and others may find them horrifying. It is a carnivore that can only be found in the woods of Australia. The intriguing thing about its name is that these creatures were discovered in Tasmania for the first time, and due to their obnoxious yells and frightful growls, people thought they were quite diabolical. It is also known as Tasmanian Devils. In Australia, don’t miss viewing these adorable devils.

While travelling through Tasmania, you have the best chance of seeing Tasmanian devils in the wild. At Cradle Mountain-Lake St. Clair National Park, Devils Cradle, and Tasmanian Devil Unzoo, which offers a 4WD tour on which you may follow the devil’s movements, you can get up close and personal with these wild animals. There are other zoos and sanctuaries all around the country.

Read Full Article: 9 Beautiful and Rare Species Found Only in Australia

1 note

·

View note

Text

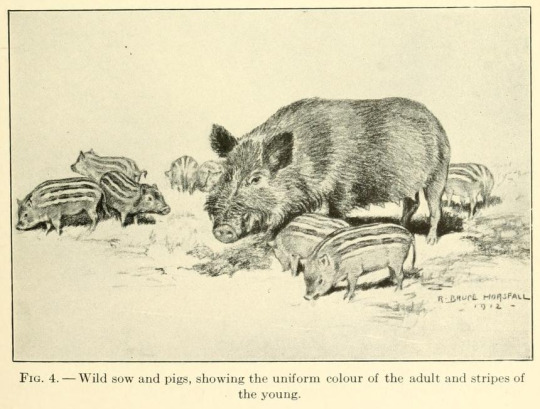

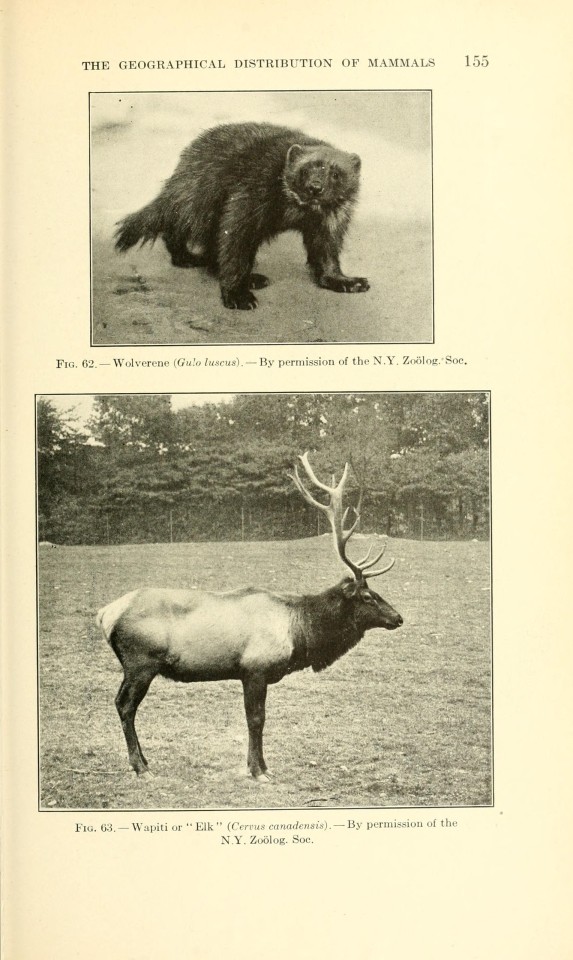

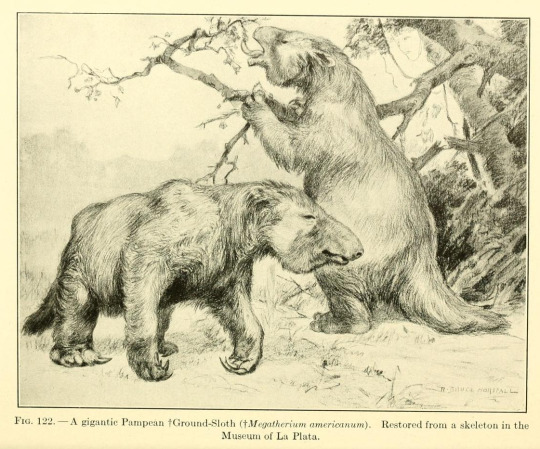

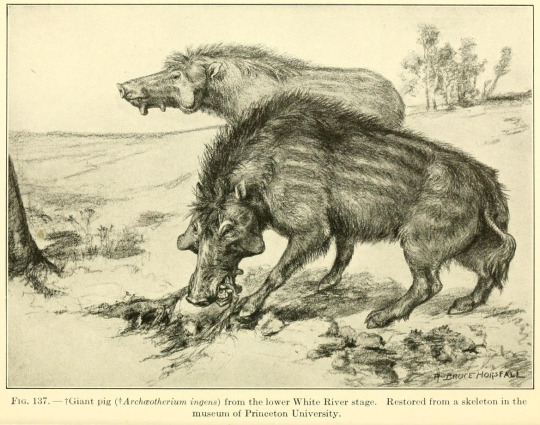

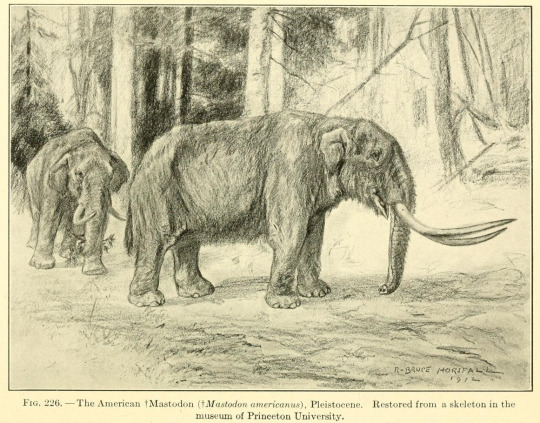

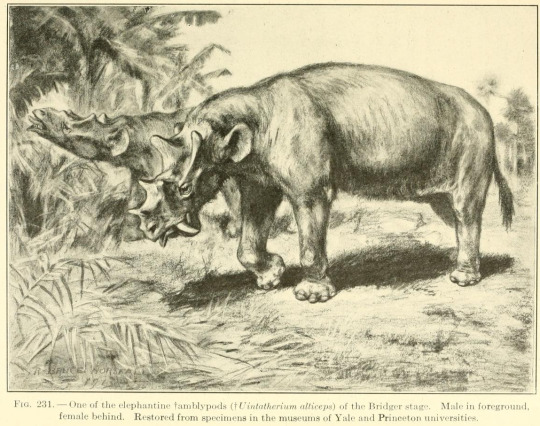

Robert Bruce Horsfall (1869 - 1948), From A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere, 1913.

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kellabor In a Nutshell

I'm realizing I've never put together all my Kellabor lore in one place for people to read, so here goes:

Kellabor:

Kellabor is a country in the southern hemisphere on a continent called Soria. It’s about the size of Mexico, maybe a bit smaller. The landscape is extremely mountainous and heavily forested, and the climate is analogous to western Canada (warm dry summer, cold wet winter). Culturally, it’s heavily inspired by Russia and Siberia. You’ll notice a lot of Russian words and names. You may also notice a lot of more western-European sounding names and culture. This is because Kellabor has historically had a strong trade history (along with some failed colonization attempts) by a country in the northern hemisphere called Rowea (which is more inspired by western Europe). People who are native to Kellabor are usually called “Gribi,” whereas people who have Rowean or other foreign ancestry are called “Seivet.” Gribi people are actually made up of several different ethnic groups that have banded together a bit more tightly as Seivet culture has started to become more widespread.

Humans:

Gribi have many old traditional beliefs and historically worship local minor gods and spirits. Most festivals and traditions revolve around the passage of seasons and paying respect to the animals and deities of the land. There’s a big emphasis on doing things like planting and honoring the spirits correctly and at the right times of year. The healer’s guild strictly adheres to these traditional Gribi values.

Seivet beliefs vary a lot, but most are “Heraldists,” a specific sect of Followers of the Luminous Child. They have integrated Gribi folklore into some of their beliefs, but are generally wary of “pagan” Gribi traditions. Churches in Kellabor are Heraldist congregations exclusively. Heraldism and The Old Ways agree on enough points to mostly get along, but leaders of congregations sometimes butt heads with Gribi leadership. Kellaborn children are usually taught to read by the local Heraldist priest, but most stewards (who are almost always Gribi and/or non-Heraldist) require said priests to use non-religious texts for teaching materials. This is often a matter of contention between local congregations and local government.

Lots of Gribi people convert to Heraldism, and plenty of Seivet people have left Heraldism behind and embraced local traditions, so there’s quite a mix of beliefs happening. There’s a lot of intermarrying and cultural mixing as well.

Calendar:

The people of this world have a 12 month, four season calendar with six day weeks. Every month has exactly 30 days. Every 4 years an extra day is added between the last and first days of the year. The days of the week are not named.

The “New Year” starts on the first of Yieldfrost, the rough equivalent of March and is considered the first day of spring.

The months of the year are shifted approximately 15 days before our months:

March: Yieldfrost

April: Leafbud

May: Newblossom

June: Broadleaf

July: Brightsun

August: Latebloom

September: Larderbrim

October: Tinderleaf

November: Baretree

December: Stonewater

January: Dimlight

February: Whiteveil

Ecology:

There are several large ungulates, including deer, elk, boar, dragon-elk (basically a giant six-legged elk), wisent (mountain bison), and tur (mountain goat). Other mammals include several squirrel species, kreezin (cave rats), zatel (fox), ermine, and bep (kind of like a pika). Large carnivores include bear (gilded bear, imagine like a grizzly bear but sort of yellow), fen cat (really just a big lynx), and direrodi (giant pack-hunting wolverines). There are a million birds, including quail, pheasant, dove, hawk, owl, eagle, and ruhk (giant eagles).

There are three dragon species: black-toothed drakes (big, cranky, and venomous opportunistic scavengers) and wild garjen (big shy herbivores) are flightless, four-legged, and non-firebreathing and are really only dragons in the taxonomical sense. Zargrum are coastal flighted dragons that dive for fish along the high Kellabor cliffs.

Non-human peoples:

There are two non-human peoples inhabiting Kellabor: sphinx and Kanai. In technical terms they are called “anthropoidal chimerics,” but only scholar-types refer to them as such.

Kellaborn sphinx look like snow leopards with snowy owl wings and a human face with ram’s horns. They’re big; think horse-sized. Culturally, they’re wanderers and nomads that travel alone or in small, casual groupings. Story-telling and knowledge-sharing are their great loves. They also like sleeping in the sun and tend to be extremely chill.

Kanai are essentially bear-sphinxes (grizzly bear body, human face, no wings or anything) and they’re stupid huge. House-sized. Like, eat-humans-whole-sized (which they have been known to do). Culturally, Kanai are hard-working land-tenders. They are extremely attuned to the ecosystem of a given area and their culture puts a huge emphasis on responsible harvest and forestry. They tend to live alone or in small, tightly-knit groups and hardly ever travel far from their home territories. Kanai have many yearly gatherings and festivals to reestablish bonds of family and friendship, and to trade stories and supplies. They very rarely fight seriously among each other.

Humans relations to non-humans:

Sphinx are generally thought to be fierce and to encounter one is a great honor. They’re often seen in the distance on the wing, but few humans have ever been closer than that. To attempt harm on a sphinx is to incite the wrath of the gods. That being said, sphinx have been known to steal wegs on occasion, and some weg-drovers are resentful of their presence. Some tales of sphinx paint them as tricksters.

Sphinx enjoy mingling and swapping stories with Kanai and humans alike, but tend to keep a judicious distance. They’re very cryptic and cat-like in personality, but are generally friendly and have been known to help humans on occasion. They have a tendency to pop in and out of places as they please, so they come across as flaky and unreliable, but they do make long-term bonds and friendships and will return to their favorite people and places to catch up on the hot gossip.

All Kellaborn people have a deep respect for Medved’ Beis (which means “bear demon”) but also a great many myths about them. Plenty of people don’t believe they exist at all. Many believe talking about them or speaking their real name will summon them (this is why no one calls them “Kanai” anymore. Literally everyone stopped calling them that for a generation and everyone forgot the word). Gribi people believe Medved’ Beis are divine beasts sent by the gods to punish people who stray from the Old Ways, and are mostly very reverent. Seivet people are just scared shitless of them and don’t like to talk about it. Neither group has much real, factual understanding of Kanai.

Kanai are tolerant of humans at best. Mostly, Kanai keep to themselves and prefer humans to do the same. At worst, things get very ugly. They have a bit of an “eat first, ask questions later'' philosophy when it comes to competition for resources, which squarely puts humans on the menu. Kanai sometimes become habitual people-eaters in areas where trappers or hunters regularly encroach onto Kanai territory. In some regions of Kellabor, people-eating has become a part of important social traditions. It’s… rough. Smart humans stay out of the deep woods.

Plenty of humans are less than thrilled about Kanai. Rarely, if a particular Kanai is vulnerable enough or really particularly brazen about their people-eating, humans will band together in an attempt to kill them, with mixed success.

Economy:

Being depredated by Kanai so often has had an effect on the behavior of humans in Kellabor. The oldest cities and towns are ones that don’t have a negative effect on the environment around them, so most people have come to live in harmony with the landscape. People tend to clump close together and don’t spread out very much, leaving huge swaths of untouched wilderness. The population is fairly low and very stable (the human population of Kellabor stays very level, even with a relatively long life expectancy) so labor is valuable, and the working class actually has quite a lot of power compared to neighboring countries. Farmland is usually owned by the farmers who tend it, “wilderness” is considered owned by the public and is always available for trappers, hunters, and foragers to harvest on (if they dare), and although taxes are fairly high, it gets redistributed quickly in maintenance of roads, social services, a well-developed courier system, rangers, etc. There are several strong guilds, such as the blacksmith’s guild, healer’s guild, mason’s guild, and trapper’s guild, among others. The guilds maintain high standards for their members, enforce their own rules and regulations, and step in to help when there are financial difficulties. The actions of the guilds are carefully monitored by the state to ensure no one is becoming too powerful or taking advantage of the system.

Agriculture:

The people of Kellabor have a thriving economy based on agriculture and fur trade. Traditionally, they rely on terraced farming of vegetables like beets and cabbage, domestic garjen (horse drake things), and weg droving (sort of a wooly pig thing analogous to sheep). The Seivet people have introduced more land-intensive farming techniques as well as ryno (a wooly rhino that’s used similarly to oxen or cows). Quail and pheasant are commonly kept for food. Rodi (domestic wolverines) are kept for companionship, hunting, and herding.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

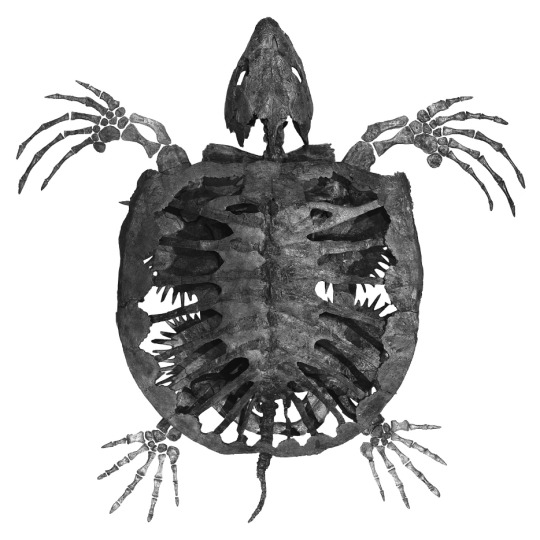

MESOZOIC MONTHLY: PROTOSTEGA

June 20th was the first day of summer! The weather here in Pittsburgh is already beautiful. It’s enough to make one dream of a socially distant beach! Summer, of course, is sea turtle nesting season: during the next several weeks, female sea turtles all across our planet’s Northern Hemisphere will return to the beach where they hatched, drag themselves onto land, and lay their eggs in the sand. It would have been an incredible sight to see Protostega gigas, one of the largest sea turtles of all time, hauling itself onto the beach to lay its eggs! For June’s Mesozoic Monthly, we’re going to “dive in” to the paleontology of this giant reptile.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s spectacular skeleton of Protostega gigas is a composite made from the fossilized bones of two different individuals. Come see it on display in our Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition when the museum reopens at the end of this month. But don’t forget to purchase your timed ticket in advance!

All turtles, including sea turtles like Protostega and tortoises like the Galápagos giant tortoise, belong to the group Testudines. This group originated during the Triassic Period, the first of the three time periods of the Mesozoic Era (aka the Age of Dinosaurs). Turtles split from other reptiles to form their own group before crocodiles and dinosaurs evolved! This means that turtles are not descended from dinosaurs, no matter how primordial some tortoises may look. Turtles differ from other reptiles in many ways, the most noticeable being their iconic shells.

A turtle shell is formed of two main parts: the carapace, or top shell, and the plastron, or bottom shell. The shell is made of bone fused directly to the spine and ribcage, so a turtle cannot crawl out of its shell without leaving its skeleton behind! Another major difference between turtles and other modern reptiles involves skull anatomy. Turtles have anapsid skulls: the bony case that protects their brain lacks any external openings behind their eyes (known as temporal openings). All other extant reptiles plus birds are diapsids, meaning their skulls have two holes behind their eyes. Mammals differ from both conditions because we have only one temporal opening, making us synapsids. Traditionally, the anapsid condition of turtle skulls has been taken to indicate that they are the most primitive of living reptiles. More recently, however, many paleontologists and biologists have uncovered evidence that turtles are in fact diapsids whose evolutionary course led, for some reason, to a secondary closure of their temporal openings. According to these scientists, the closest relatives of turtles among today’s diapsids are either lepidosaurs (lizards, snakes, and kin) or archosaurs (crocodilians and birds).

A bird’s (or pterosaur’s!) eye view of Protostega gigas (left) swimming past two long-necked elasmosaurid plesiosaurs in shallow waters of North America’s Western Interior Seaway roughly 85 million years ago. (This scene is set in what’s now Kansas!) Art by Julio Lacerda; see more of his beautiful work here.

Reptiles, mammals, and birds all belong to a group called Amniota, and the key defining feature of amniotes is a protective layer around their eggs that allows this vulnerable life stage to survive on land. Having eggs that did not have to be laid in water meant that animals could move to less-wet habitats, a significant step in evolution! Unfortunately for sea turtles, which spend most of their lives at sea, this means they must return to land to lay their eggs. An amniotic egg would “drown” in water because the embryo still needs access to air. As a sea turtle, Protostega would have faced these same reproductive challenges, plus one more: it was huge!The largest modern turtle, the leatherback sea turtle, can grow over seven feet (2.1 meters) long; Protostega dwarfs it at 9.8 feet (3 meters)! If you’ve ever seen video of a sea turtle crawling onto the beach to nest, you know that it’s an awkward process. Imagine seeing a turtle that weighs at least a ton try to do the same! Although surely clumsy on land, Protostega was a graceful swimmer, using its four rigid flippers like wings to “fly” through the water.

Protostega lived in the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea that stretched across much of North America during the Cretaceous Period (the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era). The seaway was warm, shallow, and teeming with all kinds of aquatic life: the perfect habitat for an omnivorous sea turtle. Because sea turtles are ectothermic (sometimes erroneously called “cold-blooded”), they cannot regulate their own body temperature. Instead, Protostega relied on warm water temperatures and sunlight hitting its back to keep warm. Although we don’t have a fossil record of the coloration of Protostega, we know that today’s large sea turtles are counter-shaded, with heat-absorbing, dark-colored backs and pale undersides. In an ocean environment where both predator and prey shift positions in the water column, this combination aids concealment. From below, a light-colored underside blends with light-saturated water. From above, a dark back blends with dark water. Camouflage in the water was an important feature when living alongside so many sizable predators. Protostega fossils have been found with bite marks from the large shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli, and it almost certainly was also on the menu for the mighty mosasaurs as well. Fortunately for us, we humans can enjoy the ocean knowing that few creatures are interested in eating us!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Mesozoic#Protostega#Paleontology#Natural History#Pittsburgh#Protostega gigas#Sea turtle

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Places to go to in Australia

Girls

Australia contains a myriad of natural wonders, which implies that the adventuresome traveller are going to be spoiled for choice; this country within the hemisphere has one thing for everybody. Of course, you wish to understand that places of Australia to go to throughout your trip and to search out the most effective cities, national parks, islands et al regions that Australia needs to provide. i am pretty certain everybody desires to go to Australia a minimum of once in their lifespan and you must too considering however jam-packed with beauty and natural surprise it's.

Girls

Australian Culture:

Much of Australia's culture comes from European roots. Australia could be a product of a novel mix of established traditions and new influences from western European culture, once warfare II there was serious migration from Europe. these days Australia conjointly defines itself by its Aboriginal heritage, spirited mixture of cultures and existence of democratic.

Unique Australian Animals:

Australia teems with completely different species of animals, several that ar found solely in Australia. This cluster includes Kangaroos, Koalas, Australian state wolves, wallabies, wombats, and plenty of others. The marsupial is exclusive to Australia, it is a from the family Macropodidae that mean 'large foot' it's giant hind legs, a powerful tail, little forelegs, and long ears. Kangaroos board Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and New Seeland. The Phascolarctos cinereus it's generally cited Australian kangaroo bear, but they're not a bear. The phalanger is found in coastal regions of japanese and southern Australia. The opossum prefers to maneuver around neither in daylight or night, however rather simply when sunset, as eightieth of its time is spent sleeping.

Climate of Australia:

Australia may be a continent that experiences a range of climates because of its size. consequently, the northern Australia enjoys a tropical climate, and southern Australia a temperate one. The weather will vary from below zero temperatures within the Snowy Mountains to intolerable heat within the north-west. In several components of the country, seasonal high and lows will be nice with temperatures starting from higher than fifty ° Anders Celsius to well below zero.

Great coral reef, Fraser Island, the nice Ocean Road area unit some of the places we are going to explore on this journey to Australia. Australia is that the excellent destination for you, relish our recommendations.

10. Gold Coast Introduction: one amongst the key tourer destinations to go to in Australia is that the Gold Coast additionally the foremost inhabited noncapital town in Australia placed in South East Queensland, 94km south of the city state capital., There square measure variety of exciting rides and variety of diversion avenues. With a population close to 540,000 in 2010 year. With scoop temperature twenty five.1 °C (77 °F) and min temperature one7.2 °C (63 °F).

9. Kakadu park Introduction: Kakadu parkland (name 'Kakadu' is from Gagudjuan, associate Aboriginal plain language) could be a living cultural landscape and also the largest park in Australia covering a district of four,894,000 acres, set among the Alligator Rivers Region of the territory of Australia. The parkland Kakadu is home to sixty eight mammals, over a hundred and twenty reptiles, 26 frogs, quite a pair of,000 plants and over ten,000 species of insects, the park is good of these want to grasp additional concerning Aboriginal culture. you'll be able to drive in yourself except for the alligator reason it is best to require a tour!

8. Broome Introduction: Broome ancient lands of the Yawuru folks may be a holidaymaker city in Australia 2389km north of Perth, a 2 and a 0.5 hour flight from state capital. Broome is Associate in Nursing oasis of colorize the outback and place to relax, broome is presumably the foremost reposeful place I actually have ever been, time simply appears to disappear here. Broome encompasses a tropical climate, season in Broome is late could to early Sept once temperature could be a balmy thirty °C.

7. pouched mammal Island Introduction: marsupial is third largest island once Tasmania and Herman Melville in Australia however pouched mammal has a lot of to supply. it's the simplest places to go to in Australia with children. as a result of marsupial is sort of a zoological garden with rare birds and lots of kangaroos and koalas the ocean is abundant with fish and ocean lions. The wine is pretty smart too for you. Visit pouched mammal Island. you will see why it is a commercial enterprise icon.

6. the good Ocean Road Introduction: the nice Ocean Road one in every of the world's most haunting coastal drives situated at AN hours drive from Melbourne. the wonder of this road is consists of Australia's signature stone rock formations, like the far-famed '12 Apostles' it's fancy doing it by automotive. Road may be a 243km stretch of road on the south jap coast of Australia between the Victorian cities of Torquay and Warrnambool. Best time to travel, most likely spring and season once the scenery is at its best.

5. Barossa Introduction: Barossa is one among the foremost wine (red wine in particular) manufacturing regions of Australian state. If you significantly ar a oenophilist, then Barossa is correct place to go to. Barossa depression is created by the North Para River, being solely 60km northeast of state capital, the southern finish of the vale is simply regarding one hour's drive from town. There area unit over fifty wineries within the region and 390 hectares of flora & fauna.

4. Uluru Introduction: Uluru should be one in all the most effective best-known sights of Australia and one amongst the world's greatest natural wonders! For a style of aboriginal culture and history, create your thanks to Uluru. previous name of Uluru is Ayers Rock. Uluru could be a massive stone rock formation within the southern a part of the territorial dominion in central Australia. the simplest time to go to is Gregorian calendar month, August and Gregorian calendar month.

3. Fraser Island Introduction: Fraser Island is that the biggest sand island in world spreads across 1840 km². In fact, Fraser Island is that the solely place within the world wherever forest square measure found growing on sand. settled on the southern coast of Australian state, Australia. Bird lovers are in paradise as Fraser Island is home to over three hundred species of bird. one in every of the most effective things to try and do is rent your own automobile and explore the island at your leisure conjointly do not miss the illustrious clear Champagne Pool.

2. state capital Harbour Introduction: Sydney Harbour Bridge is nicknamed "The Coathanger" is often said because the most stunning natural harbour within the world location within the initial European settlement in Australia and 134 meters on top of the ocean level. 2 hundredth of the population of state capital will see the bridge a minimum of once every day. The best time of year to visit is New Year. Whilst you can drive across the bridge, there is a toll so beware!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Indian wolf among world’s most endangered and distinct wolves

https://sciencespies.com/nature/indian-wolf-among-worlds-most-endangered-and-distinct-wolves/

Indian wolf among world’s most endangered and distinct wolves

The Indian wolf could be far more endangered than previously recognized, according to a study from the University of California, Davis, and the scientists who sequenced the Indian wolf’s genome for the first time.

The findings, published in the journal Molecular Ecology, reveal the Indian wolf to be one of the world’s most endangered and evolutionarily distinct gray wolf populations. The study indicates that Indian wolves could represent the most ancient surviving lineage of wolves.

The Indian wolf is restricted to lowland India and Pakistan, where its grassland habitat is threatened primarily by human encroachment and land conversion.

“Wolves are one of the last remaining large carnivores in Pakistan, and many of India’s large carnivores are endangered,” said lead author Lauren Hennelly, a doctoral student with the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine’s Mammalian Ecology Conservation Unit. “I hope that knowing they are so unique and found only there will inspire local people and scientists to learn more about conserving these wolves and grassland habitats.”

‘A game-changer’

The authors sequenced genomes of four Indian and two Tibetan wolves and included 31 additional canid genomes to resolve their evolutionary and phylogenomic history. They found that Tibetan and Indian wolves are distinct from each other and from other wolf populations.

advertisement

The study recommends that Indian and Tibetan wolf populations be recognized as evolutionarily significant units, an interim designation that would help prioritize their conservation while their taxonomic classification is reevaluated.

“This paper may be a game-changer for the species to persist in these landscapes,” said co-author Bilal Habib, a conservation biologist with the Wildlife Institute of India. “People may realize that the species with whom we have been sharing the landscape is the most distantly divergent wolf alive today.”

Indian and western Asian wolf populations are currently considered as one population. The study’s finding that Indian wolves are distinct from western Asian wolves indicates their distribution is much smaller than previously thought.

An ancient lineage

Gray wolves are one of the most widely distributed land mammals in the world, found in snow, forests, deserts and grasslands of the Northern Hemisphere. Wolves may have survived the ice ages in isolated regions called refugia, potentially diverging into distinct evolutionarily lineages.

advertisement

Recent genomic studies confirmed that the Tibetan wolf is an ancient and distinct evolutionary lineage. However, until this study, what was known about the evolutionary history of Indian wolves was based on mitochondrial DNA evidence, which is inherited only from the mother. That evidence suggested that the Indian wolf diverged more recently than the Tibetan wolf.

In contrast, this study used the entire genome — the nuclear DNA containing nearly all of the genes reflecting the wolf’s evolutionary history. It showed that the Indian wolf was likely even more divergent than the Tibetan wolf.

“Mitochondrial sequencing alone was not sufficient to make a case,” said senior author Ben Sacks, director of the Mammalian and Ecology Conservation Unit at UC Davis. “Nuclear DNA is the big picture, and it changes the picture. You might assume most genetic diversity of gray wolves is in the northern region, where most wolves are found today. But these southern populations harbor most of the evolutionary diversity and are also the most endangered.”

Both Tibetan and Indian wolves stem from an ancient lineage that predates the rise of Holarctic wolves, found in North America and Eurasia. Sacks said this study indicates Indian wolves could represent the most ancient surviving lineage.

Charismatic competition

Attention for gray wolves in India is often eclipsed by animals considered more charismatic, such as tigers, lions and leopards. Hennelly, who dreamed of being a wolf biologist in fifth grade, was not aware there were wolves in the region until she conducted field work on birds in the Himalayas. When the opportunity to study wolf howls and behavior in India arose as a Fulbright scholar, she jumped at the chance and began the work and collaborations that led to her team becoming the first to sequence the Indian wolf’s genome.

“I knew that if we sequenced the wolves and the results indicated a divergent lineage, answering that question could really help their conservation at a policy scale that could trickle down and bolster local efforts to help protect these wolves,” Hennelly said.

A separate study led by Sacks about endangered red wolves appears on the cover of the same Molecular Ecology issue in September. Addressing a 30-year-long controversy, that study shows that red wolves are not a colonial-era hybrid between gray wolves and coyotes, as some have argued, but the descendant of a pre-historic North American wolf that diverged from coyotes over 20,000 years ago. Both studies have substantial implications for wolf conservation.

The Indian wolf study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of India, the Wildlife Institute of India, UK Wolf Conservation Trust and UC Davis. Hennelly was also supported by fellowship grants from National Science Foundation and UC Davis.?? The red wolf study was funded by a variety of sources, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

#Nature

0 notes

Text

Ocelot

By: New York Zoological Society

From: A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

1913

#captivity#ocelot#feline#carnivore#mammal#1913#1910s#New York Zoological Society#A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🐺 A history of land mammals in the western hemisphere New York, The MacMillan Company, 1913.

10 notes

·

View notes

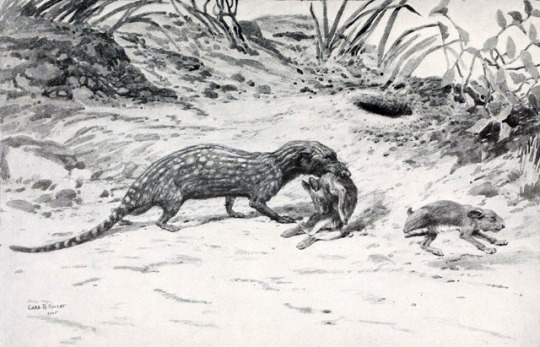

Photo

Cladosictis lustratus and Pachyrukhos moyani, Charles R. Knight, 1905, from W.B. Scott's A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere

In ancient Argentina, a female Pachyrukhos came home to find a slender form backing out of her burrow—first the skinny tail; then the long striped and spotted body, those mincing paws scrabbling below it like scribbles underscoring calligraphy; and finally the head, narrow, pointed, her partner’s limp form locked in its jaws.

Nature deals out coincidences and living things react. Had she returned to the den a minute earlier, it might have been her dangling from the jaws of the Cladosictis. A minute later, and the burrow would have been merely empty, her mate vanished, a breeding season lost. But she was there when she was there, and upon the sight of death, she turned and ran, never returning to the burrow again.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 10: Life During the Ice Ages

Image Credit: janeb13, under Free for Commercial Use Pixabay License.

The following is the transcript for the tenth episode of On the River of History.

For the link to the actual podcast, go here. (Beginning with Part 1)

Part 1

Greetings everyone and welcome to episode 10 of On the River of History. I’m your host, Joan Turmelle, historian in residence. I apologize if I sound funny, I’m battling seasonal allergies at the moment, but that won’t stop me!

During the Ice Ages, great glaciers expanded across the northern hemisphere. With so much water trapped in the ice at any given time, the sea level would drop significantly (as much as 230 feet in some places!) and there were new territories that opened up where there is ocean today. Two regions stand out: Beringia, which I had previously discussed in the last episode, and Doggerland, which connected the British Isles to mainland Europe. Because these areas were so cold and dry during the glacial periods, great forests could not grow there, even the coniferous evergreen trees, which receded southward. In their place were expansive, treeless plains: steppes and grasslands. Besides grasses, common plants included scrubs, mosses, and wildflowers. Sources of freshwater, besides glacial meltwater, included permanent shallow lakes as well as rivers.

There had been several successive glacial periods over the past 2.58 million years, and the last and most intense period began around 115,000 years ago and ran over 100,000 years. This period has been given different names for different parts of the world, with the European glacial termed the Weichselian and the North American called the Wisconsin. Even though all peoples during this time lived through the glacial period, not everyone experienced the intense polar conditions that often characterize the Ice Ages for non-specialists. Therefore, for this episode, I will be examining the three regions of the world where Ancestors struggled in the cold: Europe, Siberia, and North America.

Following the massive volcanic eruption in Italy 39,000 years ago, which spread copious amounts of ash and dust across the European subcontinent, the Ancestors who survived found themselves in a land of strange beasts. These were the megafauna: quite literally, large animals, usually larger than a person. In the frigid grasslands and tundra of southern Europe, the mammals there adapted their bodies accordingly, often sporting shaggy coats and thick layers of fat. There were the familiar woolly mammoths, the biggest animals in the region, but they were accompanied by great rhinoceroses, including the massive Elasmotherium which sported a single, 5-foot horn atop its forehead like an oversized unicorn. Alongside the great herds of reindeer was Megaloceros, a giant deer which sported great, spoon-shaped antlers, tipped with spines. There were also muskoxen and bison, as well as wild horses, and these were all preyed upon by a selection of predatory mammals, the last of their kind in Europe. There were wolves and hyenas, pack-hunting species, as well as the infamous cave bear, which was only slightly larger than the average grizzly but may have been more herbivorous in its diet (this remains to be seen). Definitely carnivorous was the cave lion. Reaching a length of almost seven feet, these big cats actually appear to have been very distinct from true lions, as opposed to the original view that they belonged to the same species.

The earliest definitive culture that we see in Europe is the Aurignacian, named after the town of Aurignac in southwestern France, where several human skeletons, stone tools, and food remains were uncovered in a local cave. As far back as 1858, the researchers who examined the finds recognized their age immediately, and over 50 years later archaeologists applied the name Aurignacian to these finds, cementing the discovery of a brand new prehistoric culture. Associated with the Aurignacians is the famous Cro-Magnon archaeological site, located underneath a rock depression in France in 1868. Like the earlier Aurignac finds, there were a few bones and tools, including reworked objects made from antlers and ivory. This is where we get the name ‘Cro-Magnon man’, which typifies the Aurignacians and marks the earliest known group of humans in Europe. Overtime, the term was extended to all of the prehistoric remains of peoples across the subcontinent, encompassing a period of many thousands of years. Nowadays, researchers try to steer-clear from the term, because its use was very fluid and not bound by anything beyond “prehistoric Europeans”. If you read the literature today, you’ll find the phrase “European early modern humans” instead.

We have been extremely fortunate to have acquired DNA from many remains of ancient peoples from across the entire Ice Ages rocks of Europe, so we have a better understanding of the movements of the different peoples. The Aurignacian culture stems from the expansion of peoples outwards from southeastern Europe nearly 39-35,000 years ago, retaking the continent as the ash cleared from the eruption. From there they reached as far north as the British Isles and western Russia and as far west as Iberia by 31,000 years ago. As well as signifying a type of culture, the Aurignacian also represents a distinct tool technology, one of the first of its kind in Europe following the decline of the Neanderthals and their Mousterian toolkit. Aurignacians preferred scrapers and blades, some of these with knife-like edges and others working as chisels. They were tools with a wide range of uses, with evidence of woodworking and the carving of skin and hide, and points that would have been attached to wooden spears. What is striking is the stones used to make these tools are very fine-grained, that is, made of small particles and minerals which would have made them particularly easy to shape. Aurignacians relied so much on these rocks that they went to great lengths to retrieve them. Archaeologists have been able to show that these Europeans were seeking out particular sources or outcrops of fine-grained rocks, moving many miles to gain access to these resources. Since the Aurignacians were plentiful in Europe, it is conceivable that trade was a regular occurrence, with many certain groups having access to specific outcrops, and facilitating exchanges with others. Marine shells have been found far inland at some sites, so if trade was happening (and not just extensive trips to the beaches), then it was happening on a subcontinent-wide scale.

While Aurignacians had effective spears, it seems that they did not go after prey of very large sizes, preferring small mammals and at least reindeer and horses. The site of Kostenki, in western Russia, shows evidence of a successful hunt, where a group of Aurignacians drove a herd of wild horses into a natural pit in the ground. Trapped inside by the steep walls, the horses were sectioned off and speared to death (perhaps also smashed by small to medium-sized stones, which would have to have been thrown at them). Afterwards, the meat appears to have been cut on site, meaning that it would have been carried away to a settlement to be prepared. Humans were using tailored clothing during this time, as previously explained, and we see plenty of bone needles for preparing warm outfits for the colder environment.

While forms of aesthetic appreciation have been recorded deep into human prehistory, as far back as Homo erectus and its kin at least, it is around the time of the Aurignacians (30,000 years ago), that artwork becomes very elaborate. While some of the oldest figurative artwork shows up 40,000 years ago in Southeast Asia, Europe’s record is particularly complete and well-known to archaeologists. For their figures, Aurignacians sculpted bones and ivory and mostly turned them into depictions of neighboring animal species. These small artworks have perplexed researchers for decades and we really have no way of knowing just what they were for (suggestions abound, from animistic totems to children’s toys). The most famous of these early figurines is the Lion-Person, found from the Hohlenstein-Stadel site in Germany. It stands 11 inches tall and clearly depicts a creature of the imagination: sporting the head of a cave lion on the body of a human. When it was originally found, the figurine was broken and had to be reassembled, and even today it still has missing parts. The feet are incomplete, but their shape has led to suggestions that the Lion-Person stood on paws. Its left arm is patterned with markings and has been interpreted as tattoos. The Lion-Person is a curious and fascinating look into the minds of people who lived 30,000 years ago, and is a long-standing mystery that prompts questions of all kinds. What does the Lion-Person represent? It is a spirit or a deity? It is nothing more than a playful exercise in creativity? I wish I knew.

Aurignacians produced cave paintings and they are works of absolute beauty, mostly depicting wildlife. Chauvet Cave in France was recently re-dated and revealed to belong to the Aurignacian culture, having been visited and painted several times by different groups. These cave paintings were cinematically depicted in the 2010 documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and the film does justice to some of the fantastic artwork found there. The details at Chauvet are so clear that they have even allowed paleontologists to reconstruct some of the life-appearances of the Ice Age megafauna, including coat patterns and soft-tissue structures that otherwise are absent from skeletal remains. There are woolly rhinos, cave lions, wild cattle or aurochs, and even a young mammoth, all depicted in very life-like poses.

Human representations (that is, actual people, not hybrids) are few and far between, with the most well-known finds being a series of vulvae that have been found throughout caves in France. Human reproductive organs appear commonly in European cave art, and that’s another mystery that archaeologists try to explain. On related artistic matters, we find the earliest preserved musical instruments among the Aurignacians. Dating back 35,000 years, woodwinds were constructed out of the bones of vultures, where the hollow spaces were further modified and a series of five holes are drilled along the topside. One of these woodwinds spans 8.6 inches and, yes, reproductions have been made and tested out by experimental-archaeologists. They sound quite nice and one can only imagine what other instruments and songs (if any) accompanied these woodwinds.

The people behind the Aurignacian culture had a long-lasting presence in Europe and subsequently produced other, newer cultures over the span of tens of thousands of years. One of the most dramatic of these shifts started 33,000 years ago, when groups of people from far eastern Europe began to spread westward across the subcontinent. By 28,000 years ago, the last traces of the Aurignacian culture were gone, replaced by the Gravettian culture. These people were named after the site of La Gravette in France, where the foundational artifacts of their culture were catalogued for the first time. Like the Aurignacians, the Gravettians had a distinct tool technology, where the knife-like blades grew smaller in size and were carefully knapped at their ends into fine points. This made them much easier to mount and secure onto wooden spear shafts. Thus, their weapons were very lightweight and swift in use, and this seems to have allowed the Gravettians to experiment with hunting prey of greater sizes. The woolly mammoth, in particular, was a favored prey item, so much so that we often find Gravettian camps situated right near massive kill sites. Its currently debatable as to whether these people physically hunted mammoths or whether they scavenged their carcasses, but the sheer number of skeletons found in some places suggests that they did go on hunts occasionally. In these instances, the young were sought after, as revealed by the site of Milovice (meh-low-vitza) in Czech Republic, where many of the dead mammoths were found with spear points around them. Due to the lack of forests, mammoth bones were used instead of wood for making campsites. First, they dug small oval-shaped depressions in the ground and then formed walls and roofs out of the massive ribs. Skin and hide as well as patches of grass, were then lined all around and inside, ensuring that the camps were as warm and secure as possible. They certainly had to be to survive the intense cold.

While these people seem to have been good hunters, they were not picky. In fact, they seem to have been equal opportunists, managing to catch plentiful fish from rivers on numerous occasions (it has been estimated that 50% of the protein in their diet derived from aquatic resources). Any meat that was worth keeping could be buried in the soil, where the permafrost worked like a freezer that kept the food from spoiling a little longer. Reindeer, rabbits, and gamebirds were commonly hunted animals as well, and there is evidence to suggest that they set up snares and used nets to catch some of these smaller prey items. Given the harshness of the Ice Age temperatures, it seems that Gravettians mostly kept to themselves, with family groups staying at their campsites for many months out of the year. On better, warmer days, however, they did seem to come together for short periods, with evidence from some campsites pointing to a total collection of a couple hundred individuals. These would have been great times to come together, perhaps allowing for trade as well as reconnections.

There have been some significant burials found at Gravettian sites across Europe, complete with grave offerings of significant abundance. We can only guess at what sort of social structure they had, but the presence of such graves is certainly a long way from the possible burials that Neanderthals may have performed. At the site of Sungir in western Russia were found nine different burials, the people representing ages as young as adolescence and as old as 60 or more years. Given the layout of the remains in the graves, we can try to reconstruct the apparel of the Gravettians. That they made and wore jewelry is very clear, and the burials reveal painted bracelets and pendants, caps decorated with sewn beads of bone and clay, and tunics made of leather and furs. What is remarkable is the process it must have taken to construct all these decorative items: experimental archaeologists have replicated the methods it took to make and sew the beads, and it took something like a couple thousand hours to do. And this wealth of decorative apparel is found on people of all ages.

Artwork among the Gravettians is remarkably distinct. The well-known and much speculated Venus figurines mostly belonged to this culture and they were widespread across Europe and all the way into Siberia. A typical Venus figurine depicts a woman with a large body and all of her sexual organs are almost always exaggerated in some way, while the arms, legs, and head are reduced in size and/or featureless. The most familiar of these is the Willendorf Venus, sporting what looks like either braided hair or a wool cap, but no eyes or mouth or anything. Her hands are resting on her breasts and her legs and knees are bowed inwards, no discernable feet present. Everybody and their mother have offered explanations for these figurines – why they were made, who made them, why they were so widespread – and nearly all of these are mostly speculation. The most popular hypotheses lean towards religious purposes: the Venus figurines are not very big and seem almost portable, and they may have been fertility totems, perhaps representing some goddess. Among the more fringe but plausible ideas is the suggestion by art historian Leroy McDermontt who poses that these figurines are basically self-portraits by women who were looking down at their bodies and sculpting what they saw (hence the strange proportions). Incidentally, this particular hypothesis has not gotten much support and seems to be debunked by other Venus figurines with normal proportions. Perhaps there was more than one reasoning behind them? In contrast to these is another famous figurine, the 25,000 year old Venus of Brassempouy, which is nothing more than a finely sculpted head with long, detailed hair. The individual, commonly called a woman but who really knows for sure, is one of the oldest artistic representations of a human face. It’s quite beautiful to look at, only an inch and a half high yet so detailed, one can only imagine the work that went into it. It appears cracked at the neck, so there’s a strong possibility that there’s a body to go along with it. As far as cave art is concerned, we find many similarities from the Aurignacians, including depictions of animal life. Some of this is a lot more stylized, however, including the paintings at Pech Merle in France, where some of the animals are surrounded and covered by spots. Perhaps most striking of all are the hand-prints found at some of these caves, where Gravettians seem to have blown ground ochre paint over their outstretched hands and left the impressions on the cave walls. Some of these prints show certain fingers missing, and this had led to some speculation that at least some Gravettians engaged in ritual finger amputation, which in turn implies some interesting social behaviors.

Gravettian culture lasted until 22-21,000 years ago, after which began the harshest period in Ice Age Europe, the Last Glacial Maximum. Basically, it was the time when the glaciers reached their largest size and range across the northern hemisphere. Europe was severely affected and the people who lived there could not adapt fully to the intense cold, therefore, the subcontinent was all but abandoned in the northern reaches, including Doggerland. Some of the Gravettians that remained in southwestern Europe eventually developed a brand new culture, the Solutrean. The name derives from Solutré in France where their remains were first recognized. Though recently showcased in the film Alpha, we really don’t know much about the Solutrean culture. Their toolkit, of course, is distinct form the earlier Gravettian, known by the leaf-shaped spear points. These stone tools were exquisitely constructed by a process known as pressure-flaking. Flint would be heated in a firepit to make it more durable, while giving it a pristine porcelain-like surface. Then, using mostly organic materials – bone, antler, fingernails – the stone was pressed hard onto all sides to remove thin flakes, eventually producing a thin but durable point. It seems that reindeer and horses were the most common prey animals, easily brought down by the flint-tipped spears, but there is evidence of wild cattle and bison hunts as well. We really don’t have much as far as cave art or burials for Solutreans, but it appears that, at least 17,500 years ago, they had begun to use atlatls. These are spear-throwers, specially designed tools of bone and antler, where spears could be loaded onto and thrown. The atlatl increased the overall accuracy of the throw, as well as the distance, to ensure that kills were made in relative safety. Some tests show that spears could be thrown as far as 330 feet, leaving out the need to get too close to dangerous prey animals. Whether Solutreans invented this technology in Europe or not, it definitely caught on among all the later peoples of Ice Age Europe.

Part 2

The Last Glacial Maximum ended its grip on Europe 18,000 years ago, and just a thousand years earlier a new culture developed on the Iberian Peninsula. Though these peoples lived along the same refugia that the Solutreans did following the spread of the ice sheets, DNA studies have shown that these people, the Magdalenians, are descended from late-surviving Aurignacians that managed to hang on while their kin transitioned into Gravettian life. And so, 19,000 years ago, they spread northward and re-peopled much of northern Europe as the Solutrean culture slowly died out by 17,000 years ago. The name Magdalenian derives from La Madeleine, a site in France that preserves an entire rock shelter from this period. Their toolkit is characterized by small stone blades as well as by an increased use of worked organic materials like bones and antlers. The design of the atlatl, for example, was built upon by the Magdalenians. One of these, found in Bruniquel, France, had carved impressions of reindeer all along it. Incidentally, reindeer appear to have been the most common animals hunted, though they certainly made use of other large mammals like red deer, bison, and wild goat. River resources proved to have as much value to them as they did to the Gravettians and there is good evidence of intricately carved harpoons for spearing fish.

With the Magdalenians comes a return to long-distance sourcing for stones as well as a possible network of trade between groups across Europe. Some types of stones used have been tied to outcrops over 430 miles away, though the average distance is more like 100 miles or so. In contrast to all that had come before, a system of sedentary of semi-permanent living became prominent among the Magdalenians, with evidence of groups of neighboring communities coming together for many months out of the year when an abundance of resources or a particularly warm spell was present. That groups often stayed so close together seems to indicate that social organization among these humans had reached more complex levels than ever before. In fact, the original site of Madeleine had produced remains of an impressive rock shelter that spanned almost 600 feet in length, which certainly housed entire families within its walls.

Some of these rock shelters were located near great cave sites, and many of these have produced more remarkable artwork. Two caves stand out among archaeologists. The first is Lascaux in France, home of the famous “Hall of the Bulls” which is a room entirely covered in depictions of wild cattle. Many of the walls of Lascaux showcase some very fascinating images. One of the bulls has a series of dots painted right above it, and another sequence of images shows (in order from left to right) a woolly rhinoceros, a man with a bird-like face, and a bison that appears to have been gored by a spear, its intestines hanging out underneath it. While at first, these appear to be simple images of the life and times of the Magdalenians, some researchers have hypothesized that these particular paintings depict constellations, making them star maps of a sort. So, the instance of the dots above the bull is a representation of Taurus with the Pleiades star cluster, and the rhino, bird-man, and bison shows a sequence of Leo, Gemini, and Taurus yet again. While some discussion of this hypothesis has been giddily grasped by fringe individuals with more of an ‘Ancient Aliens’ bias, it nonetheless could represent an understanding of the cosmos that would be very well in line with what we know about forager groups. A good knowledge of the stars and their seasonality can provide a tool for knowing when certain times were upon you, and whether you’ll be able to hunt certain species. But, of course, this isn’t something we can confirm or deny with certainty. The other famous cave site is Altamira in Spain, where the walls are littered with bison depictions, painted bright red. There are abstract images here too, as well as more hand prints by lost peoples. It should be stated, that anyone wishing to visit any of the cave sites that I’ve described here will have a difficult time doing so. Years of tourist activity have affected the walls of the cave, and mold had begun to grow and damage these paintings, tens of thousands of years old. To better preserve these sites for future generations (and future research), they have all been closed off to the public. Instead, there are full-scale replicas of these caves that you can go to, without the worry of causing further harm to these treasures.

While Europe experienced quite an array of fantastic cultures throughout the Ice Ages, their Siberian neighbors also developed equally fascinating societies. As stated previously, Ancestors have been living in this region for some 50-32,000 years. Except in eastern Siberia, humans did not have to endure the bitter-cold pushback from northern Europe, so they more or less rode out the Last Glacial Maximum as best they could on the steppes. However, they did not necessarily have it any easier; they, for example, often lacked access to extensive cave systems to take refuge in. The people here had to create their own shelters out of whatever resources they could find, and crafted exquisite tailored clothing that was densely layered. One of the best examples of this ingenuity was by the Gravettians, the same culture that peopled Europe from the east 33,000 years ago. Not everyone moved into Europe, and thus we have a long-standing cultural complex here called the Eastern Gravettian which lasted until roughly 25,000 years ago. Like their European cousins, the Eastern Gravettians made use of woolly mammoth as a resource for building their campsites. At Mezhirich in the Ukraine, are the remains of at least five houses, 13-22 feet across (850 square feet in area). Each house had a wall of mammoth bones stacked together, with tusks, limbs, and ribs supporting a drape of skin and fur over the entire structure. Hearths and storage pits were dug inside, so these homes would have been warm and idea for a family of five (as suggested by the remains). Curiously, seashells and amber have been found in these houses, telling us that trade seemed to have been present even here as there were no oceans nearby and no trees growing anywhere. On a related note, groups that lived further south, where there were forests to be found, used wood as well as bone to construct their shelters, as evidenced at the site of Dolní Vestonice in the Czech Republic.

Siberian toolkits were very standard across the Ice Ages: blade and flake stone tools, coupled with organic bone needles for making clothes. We tend to find settlements near major rivers, like the Don and Dnieper rivers in the extreme west of Russia and the Tunguska and Yenisei rivers in the central regions. Despite the open air of many of these campsites, there were highland places along the rivers where any would-be hunters could get a good look at their megafaunal prey before striking. These included woolly rhinoceros, wild horses, steppe bison, and reindeer, as well as woolly mammoth (basically an extension of Europe’s large mammal communities). Towards Central Asia, which has been blessed with a few select caves, there were people here to inhabit them. The Shugnou culture, present from 20-15,000 years ago, have been found in present-day Samarkand in Uzbekistan and are a relatively poorly-known society. As far as we know, they hunted megafauna like their neighbors (specifically horses, sheep, goats, and cattle) and pollen studies suggest that they had access to juniper, ash, plane, and hazelnut trees during the warmer months, but that’s the most that we have right now.

More familiar are the cultures of the Ancestral North Eurasians, that demographic of people who settled central Siberia and contributed their genes to both European and Amerindian peoples. Between 26,000 and 12,000 years ago, a number of cultures developed across the region, and these have become particularly well-known thanks to both archaeological findings and genetic sequencing. The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, located in southeast Russia, inhabited large camps during the winter months, with partially dug homes made of reindeer bone and skin. They only made flaked stone tools, which makes them an outlier in the Siberian Ice Ages, as scrapers and other stone implements are usually included in toolkits like these. A lot of tools were made from organic materials, including bone and antler spears, which were tipped with stone points. This makes sense, as this region was not forested during the Ice Ages and thus lacked the wood necessary to make spears. The Mal’ta-Buret’ people made use of bone for more than just weapons, as we find carved and polished ivory spikes that have been interpreted as hair-pins by some and beads made from bird bones that were strung up on pendants and necklaces. They also left behind some remarkable bone sculptures and figurines, often depicting people as well as birds in flight and at rest. There are also engravings of mammoths and other animals on pieces of tusk. The human figurines are of immense interest, because they tend to be quite detailed in parts, revealing that some Mal’ta-Buret’ individuals sported thick and wavy hair. There are figurines here that resemble the Venus statues found in Europe, which begs the question whether these people had any significant contact with European communities like the contemporary Gravettians.

Related to these people were the Afontova Gora culture, which lived across the Yenisei River Valley. These Siberian peoples had a more typical stone toolkit, with blades and scrapers that they used to hunt large game. They, and the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, have preserved their DNA for geneticists to examine and we have been able to reconstruct their overall appearance thanks to that. Ancestral North Eurasians seem to have been very similar in appearance to East Asian peoples, with some individuals having dark skin and brown eyes, but there was no doubt variation in traits among them. In particular, while some people had darkened hair, some of the Afontova Gora individuals carried a gene that has been allied to the presence of blond hair in Europeans, and its very likely that this trait originated among these peoples before it was transferred over into Europe over the following thousands of years. It’s one thing to be able to reconstruct an entire lost culture, but another thing entirely to put a face to it too. This underscores the importance of archaeology and ancient genetics in working together to bring the past to life.

At the doorstep of Beringia there were a number of cultures that experienced the worst that the Last Glacial Maximum had to offer. Geologic evidence suggests that, like Europe, eastern Siberia saw a population shift, where communities fled to the south as the glaciers extended downward. One of these was the Yana culture, who made a living hunting woolly rhinoceros and using their horns as tools. They lived in this this region until 25,000 years ago, when it was abandoned. We know that some groups were trapped in Beringia around 28,000 years ago, prior to the expansion of glaciers, and this event no doubt caused further strains on the populations living here, but as it ended the region saw a re-peopling. The Diuktai culture represents a community that thrived following the Last Glacial Maximum. Dating to 16,800 years ago, these people are very important to archaeologists as they reveal some of the details of the very beginnings of the peopling of the Americas. Among the choppers and flaked stone tools are microblades, those tiny stone blades that have arisen multiple times among Ancestors across the world. This tradition, in particular, originated in Siberia during to the Last Glacial Maximum as an adaptation to prevent carrying heavy loads on hunts. These microblades were efficient tools, able to be crafted onto spears that could still do some damage. Indeed, we find them among the remains of bison and horses from eastern Siberia and into Beringia.