Audio

(Daniel Lu) Made on a train ride.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Awkward Turkey

The workshop project was to make “high five gloves” that light up an LED using conductive threading and fabrics. A circuit is complete only after two people high five each other. I placed the fabric such that only an awkward turkey could light up the LED.

0 notes

Photo

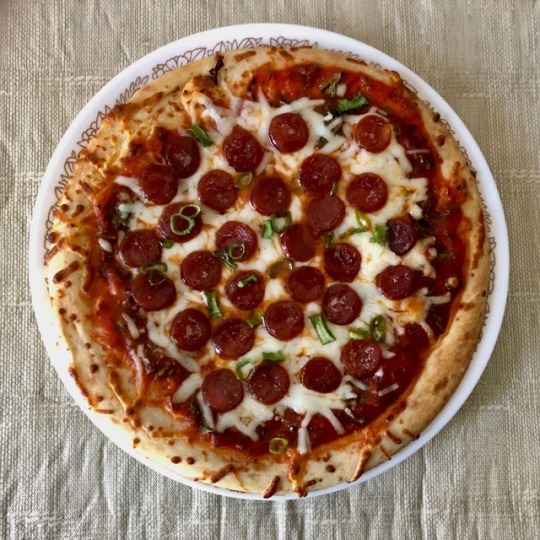

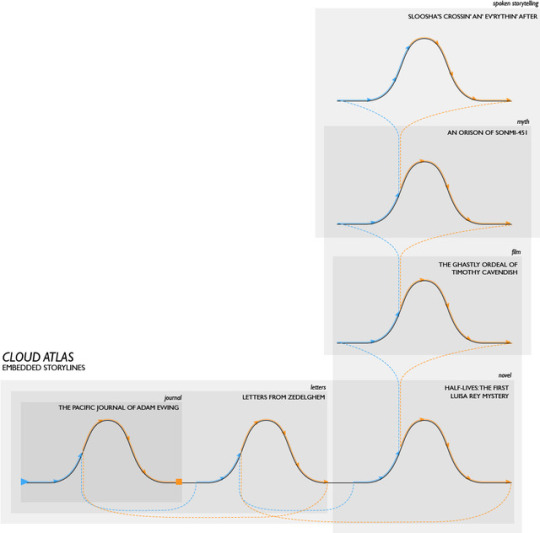

the extremes

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

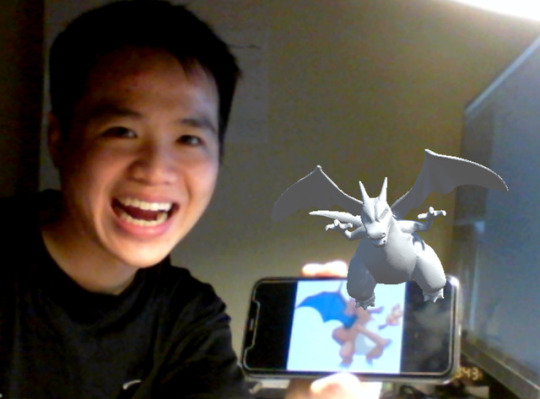

testing a chatroom project for an online programming class

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=wawSCvuGj4o

Inspired by 2001 A Space Odyssey and Carl Sagan

1 note

·

View note

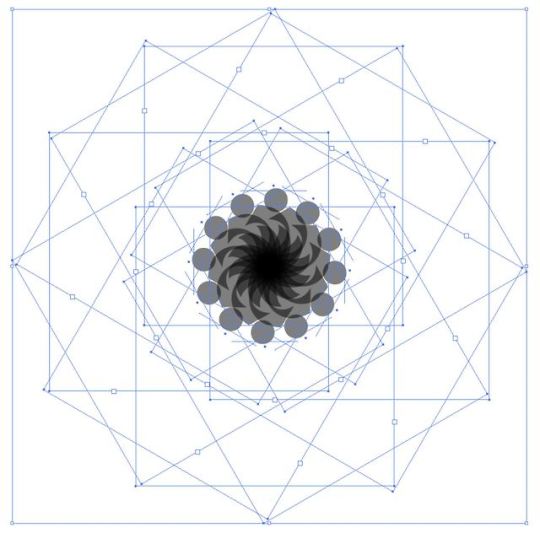

Photo

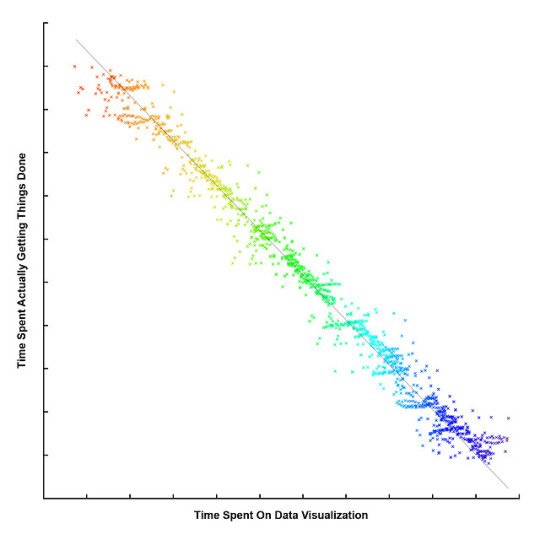

when you try to make something in Illustrator, and the selection looks cooler than what you’re trying to make.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

finally fixed my headphone jack. third time’s the charm.

0 notes

Photo

together

together

together

0 notes

Text

The Trolls are Alright

I started the first class by handing out surveys for the students to fill out, asking for their favorite TV show or movies so that I could provide relatable examples of good framing and composition. As I took attendance, one kid blurted out, “Can I just write in New York Times?” I looked up from the attendance sheet, totally caught off guard. With all of my mental capacity, I responded:

“What?”

“I don’t watch TV. Or movies. Can I just write the New York Times?”

“…Do you read the New York Times?”

“No…I’m just going to write that in.”

He knew the game I was playing. He wasn’t going to give me personal information, as if I was going to use it against him later.

This was the first time I ever taught photography to middle school students. This was also the first time I tried out a class involving smartphones only. The focus of the class was less on creating highly technical shots (high speed, long distance zoom, etc.) and more on general composition (oh and #nofilter). I originally planned out a detailed curriculum where I present key concepts, take students to a different location, and hold group discussions afterwards. When I was done writing my lesson plans, I had something resembling a college syllabus. It felt a bit silly, even a little foreboding, for something that described kids’ summer camp activities to sound so academic and serious. But I also couldn’t see myself teaching any other way.

By the end of the first class, I had unsuccessfully gone through what I originally thought would be two classes’ worth of activities. I dismissed the students and “New York Times” kid ran out of the room, two arms extended straight behind him, exactly like ninjas from Naruto. Yeah, he definitely watches TV…

I left the school, got on the subway, and just sat there, totally drained. It was clear that most of my lesson plans had to be thrown out. Discussions weren’t going to work if the students were going to actively refuse to open up. One question kept gnawing at my mind:

“How can I trick these kids into learning photography?”

I struggled with the fact that the students weren’t in my class to develop something they already had an interest in, like people in a photography class typically are. It was summer camp. They just wanted to play. To teach them concepts of composition would have been like trying to teach physics to skateboarders. My students didn’t see a point in getting focused and self-aware. In their minds, taking photos is as natural as breathing. What was there to talk about? To think about? To improve?

I thought back to when I was in middle school. I was lucky enough to take a photography class in eighth grade, where I learned to use a black and white film SLR camera and develop photos in a dark room. I remembered how awesome it felt in the darkroom seeing the photos emerge out of paper as they sat in the chemical wash. I also remember failing a quiz on shutter speed and aperture, barely passing the class. When I started out in photography, I mostly learned from doing photography. Actively thinking about technique and craft came much later, after I was open to asking myself questions about how to improve. Thinking back to those beginnings, I re-focused my classes less on presentations and more on activities, partly in hopes that those activities would raise similar questions in the kids’ minds on how to get better.

But sometimes skateboarders just want to skate. My role as a teacher was more about creating different skating environments than about teaching them “the right way” to skate. One of the class organizers referred me to this amazing book called The Photographer’s Playbook. Each page was a different person’s idea of an activity or a story about their most memorable lesson in photography. If you’ve ever seen Avatar: The Last Airbender television series, the experience of reading this book was similar to how the main character could recall the spirits of all of his past lives for their advice in times of crisis. I never really followed the photo activities in the book to the letter but they spurred activity ideas of my own, much more readily than when I read conventional books that break down photography into parts: rule of thirds, aperture and depth of field, etc. I had to break out of the “learning first, doing later” approach and the Playbook demonstrated ways that learning could be embedded in doing.

The only principle I emphasized to the students was FART, an acronym I learned from renowned camera reviewer, Ken Rockwell. FART stands for Feel, Ask, Refine, and Take. Most people take photos impulsively. FART reminds photographers to become more aware of those impulses and refine the photos accordingly, usually by standing in a different nearby location to get a better angle. I felt like this was the most important thing they should take away from the class: there’s no wrong or right way to envision a photograph, but there’s still better and worse ways to capture it. The acronym fit perfectly within the adolescent minds I was trying to teach. Every class would begin with the word FART on a projector screen.

Slowly I grew comfortable giving the students ideas of what to do while still giving them some freedom in how to do it. Sometimes it became impossible for them to take a bad photo. The troublemakers (or as education professionals now call them, “nonconformists”) occasionally ended up with more interesting photos than the ones who just played along. In one activity, I had the students take a photo every few steps on our way walking to a nearby park. What I intended was for the kids to notice multiple scenes in their usual surroundings. Here’s what “New York Times” kid took:

In spite of trolling the activity, he still managed to take an interesting series of photographs. You first laugh at his consistent facial expression, and then you start to notice what’s different in his surroundings in each frame. This is who he is. This is where he is. This is him. After we came back from the park, I asked the students to turn three photos into black and white cropped squares and modify them however they like. Here are his three photos:

Again, the results were not what I intended. Nevertheless, he ended up making three genuine and unique photographs. I can’t say for sure if he was “getting better” at photography or if he was just fooling around. Probably the latter. But every time the New York Times kid did his own thing, I just had to laugh, both at myself and at what they made. Here I was, trying so hard to get the students to learn something, when maybe I had to let go a little and just appreciate their photos in a different light.

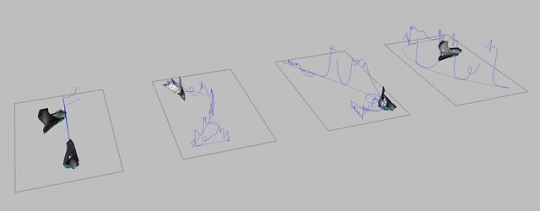

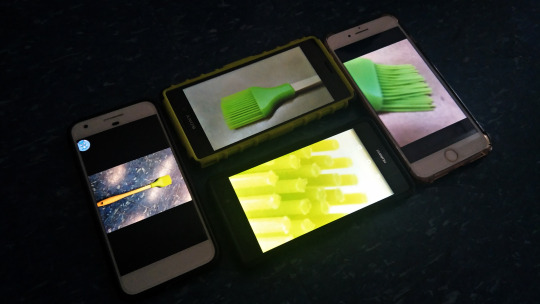

For the next class, I had the students first take photos of the same object in their own angles. They would then display a different photo of the same object and place their phones on the floor, forming a “digital collage”:

When I told them to take photos of an umbrella, one student opened it and threw it in the air for another student to take a photo of it in “mid-float.” I could have easily said “Hey! Stop messing around!” but I recognized that it could lead to something interesting. When it came time to make the umbrella collage with their phones, the two students realized they could make it look like a person was throwing an umbrella from one phone screen to another.

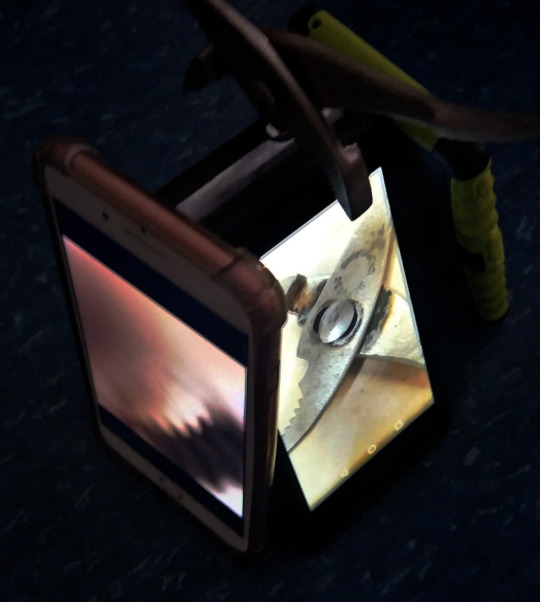

For another collage, one student started stacking the phones like a house of cards. The result was a 3D collage sculpture of a wrench:

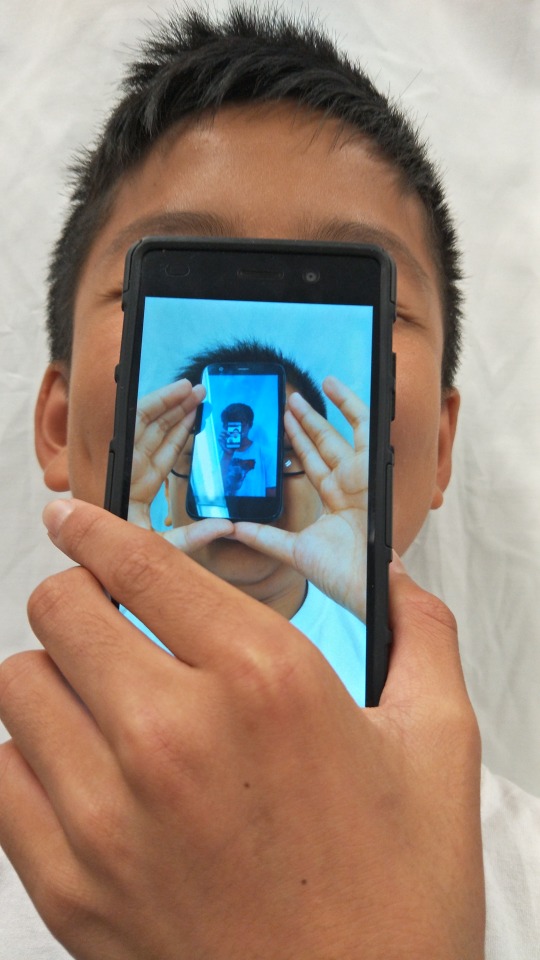

It was moments like these that left me to wonder. I knew I had a hand in what they made. I did lay the ground rules for these activities. But it still felt like the students were doing this all on their own. Was I really teaching them anything then? Perhaps I left this whole experience more changed than the students. It was only during this activity that I realized I had neglected to really consider how the smartphone could enable activities that wouldn’t make sense for regular cameras. During the collage activity, the students instinctively “cropped” their photos by zooming in and out on the display. My last class tried to make a “photo in a photo” class portrait:

Again, they tried to troll the exercise by covering their faces, but if you didn’t know that, you might see the photo as social commentary on identity in the age of smart devices. Every time the kids disrupted the activity, my attempts seemed to fail fantastically. On the one hand, the students didn’t end up making what I intended them to make. On the other hand, I had to recognize they still made something brilliant and the whole effort wasn’t for nothing.

Before this all happened, the only way I imagined I could teach people anything was through breaking things down into key concepts and then actively critiquing a person’s output. Sitting in lectures in college and going to meetings for my day job got me accustomed to this standard way of communicating and learning. Teaching middle school kids reminded me that sometimes it can be more natural and fun to just do an activity and have principles be internalized through experience. I’m still not sure how much of an impression I really made on these kids’ creative confidence. But perhaps I shouldn’t view teaching that way. Perhaps I was at my best when I was teaching for the moment, rather than for some hypothetical future where one of these kids becomes a world famous photographer. The students took photos. They shared them. They laughed. And then they took them home. Maybe that’s all I need to do.

For the last class, the students had to fill out another survey form, this time required by the Fun Fun Saturday program. The “New York Times” kid wrote one word responses to each survey question, forming the sentence, “I-learned-absolutely-nothing-from-this-class.” I asked him to take it a bit more seriously. He filled out the form again. For the question “What did you learn in this class?” he wrote:

“I learned to FART.”

I guess that’s something right?

0 notes