Text

A Radical Narrative Disguised as a K-Drama: "Coffee Prince," Gender, and Sexuality

What would you do if you fell in love with someone but couldn’t tell if they were a man or a woman? That’s not quite the premise of the K-drama “Coffee Prince,” but it is the question posed to its viewers. In the series, an androgynous woman named Eun-chan (played by the beautiful actress Yoon Eun-hye) is mistaken for a boy. Its other protagonist, and Eun-chan’s love interest, is Han-gyul (Gong Yoo), a slacker who comes from a wealthy family and is pressured into finally earning his living. He takes over a coffee shop owned by his family and renames it Coffee Prince. Unlike him, Eun-chan is hardworking, the eldest daughter of her family who lives at home with her mother and younger sister and works multiple jobs to earn money for her family. After developing a chance friendship with Han-gyul, Eun-chan is offered a job to work at Coffee Prince. The catch, though, is that, according to the coffee shop’s gimmick, all the staff must be men, the “coffee princes.” Eun-chan had already been mistaken by Han-gyul for a man and passively kept this illusion up—even pretending to be Han-gyul’s gay lover, so that she could help him ruin the blind dates his family has been sending him on—but with this job opportunity (which offers her higher pay than her other jobs) and a chance to remain close to Han-gyul, she actively keeps up with her disguise. We are even shown a breast-binding montage to stress the care and work put into passing as a man. If you understand even the basics of melodramas and rom-coms, you can begin to imagine what happens next.

Here’s a brief, somewhat reductive description of how K-dramas work: they set up a couple, dangling the possibility of them ending up together (and convincing you of the necessity of this), and then they create a series of obstacles to delay this from happening until the last possible moment. It’s very simplistic but it works so well that there’s little need to stray from this formula. One of my favorite aspects of K-dramas, though, is the more “non-narrative” aspect: between the major plot points that move these stories along, there are a lot of scenes that are, narratively speaking, unnecessary. My favorite moments from “Personal Taste,” in which Lee Min-ho plays a man pretending to be gay who falls in love with Son Ye-jin, are those that simply involve Lee and Son hanging out, acting playfully, and chastely flirting with one another. While Son believes Lee to be gay, the attraction between the two nevertheless materializes as a pseudo-platonic friendship that, despite being non-sexual, is quite passionately romantic. If we can equate plot with the horizontal thrust of narrative, then the other dimension of K-dramas, and a key feature of melodramas in general, is their verticality, their poetry.

The best moments in K-dramas come when the horizontal and vertical dimensions are aligned to serve one unified purpose. The vertical asides whip up a frenzy of emotions, create tension, and reveal new, tender dimensions of the central couple’s relationship, amplifying the urge we have for the horizontal plot to develop and come to its fated conclusion. In “Coffee Prince,” we desperately want Eun-chan and Han-gyul to end up together. What this means in terms of the narrative is that, essentially, we want Han-gyul to “become” gay. After all, there are two general ways that the obstacle (Han-gyul thinking Eun-chan is a man) could be surmounted. First, Eun-chan could come out and admit that she is, in fact, a woman. She does this with many of the series’ minor characters, all of whom come to realize that she is a woman before Han-gyul does. Second, Han-gyul could say that he doesn’t care and that he’s going to love her/him no matter what. This second scenario is what actually happens, but it’s worth pointing out why it’s really the only option. K-dramas depict love as an overwhelming totality so ecstatic that it transcends just about everything and approaches the realm of the metaphysical. To put conditions on this love—and once the romance plot is initiated, not even sexual preference can keep the couple apart—is anathema to the worldview embodied by the K-drama. For Eun-chan to reveal that she is a woman would excuse Han-gyul from further proving the integrity and totality of his love for her/him, which is the precise modus operandi of the K-drama.

K-drama’s treat love as so rapturous and all-consuming that, despite the fact that they minimize the visibility of sex and emphasize the relatively greater importance of romance, you couldn’t accuse them of ever being prudish. When sex is brought to our attention, it is treated discreetly: the only sex scene in “Coffee Prince” actually occurs in the space between the end of one episode, when the sexual encounter is teasingly hinted at, and the beginning of the next episode, when Eun-chan and Han-gyul wake up in bed together. Nonetheless, sex is never treated as merely redundant. We can debate the pros and cons of this approach, what it means in terms of gender and sexual politics, but personally, I love it: the K-drama’s intoxication with love in the abstract allows it to take romance plots to unorthodox places. It’s probably misleading to draw conclusions from the two K-dramas that I’ve seen, but taken together, they are interesting. Both depict couples whose sexuality is initially (and temporarily) nullified due to misunderstandings and outright deception (though not of a malicious intent). But this nullification allows something else to arise in its place.

In “Personal Taste,” Son Ye-jin becomes more and more attracted to Lee Min-ho even though she think he’s gay. To its credit, the show rather maturely discusses homosexuality (even featuring a very dignified and likable gay character who, although his sexuality is often neutralized to some extent, is never reduced to caricature or stereotype) and never resorts to the line of thinking that assumes women want to fall in love with a gay man and possibly change him. In fact, it’s Son’s friendship towards Lee, her respect for his presumed sexuality, that adds fuel to the fire of their relationship, which walks the line between platonic and erotic. In a sense, the narrative of “Personal Taste” needs Lee to pose as gay in order to take sexuality out of the picture for a moment, stoking the flames of romance until their romantic passion can be consummated at the end. By sidestepping the question of sexuality, “Personal Taste” can explore a different side of love (all the more potent because it masquerades as being platonic) that is not often narratively available in the contemporary world, where sex is somewhat routine (in many everyday relationships but even more so in films and television).

In “Coffee Prince,” Han-gyul believes that Eun-chan is a man, but he nevertheless develops feelings for him/her. At first, these feelings are of a platonic nature, reminiscent of “Personal Taste.” In one scene, Han-gyul and Eun-chan make a pledge that they are brothers. As with “Personal Taste,” love is treated as a force that transcends gender and sexuality. The love we feel for a close friend can be very similar to the love we feel for someone to whom we are attracted sexually, even if the forms each takes are radically different. These K-dramas blur these lines because love is understood as something that cannot be contained, so you can never say, “Okay, now I’m going to love you, but only to this extent and in this way.” (Well, you can, but everything we understand about love means that doing so will only get us so far.) The point here is not that the love between two male friends is always and inevitably homoerotic, but rather, what K-dramas tend to insist is that words like “homoerotic,” in this case, only manage to convey a portion of how human beings might experience love. Love transcends not just sexuality (which it embraces and folds into itself) but, more precisely, sexual identity (which it dissolves and makes moot). Theoretically, we might fall in love with anybody, because if unconditional love is something we pursue and accept, then we cannot portion it out into pre-approved forms.

This point is central to what occurs in “Coffee Prince”: this K-drama’s stroke of genius is in building up the attraction between Han-gyul and Eun-chan until the former must, essentially, “become” gay (or so he thinks, obviously). If the affirmation of unconditional love is truly something in which to be believed (and it is central to the melodrama’s emotional dynamics), then Han-gyul can’t just stop at the last minute, halt his attraction, and decide that the person he’s falling in love with is pretty much perfect but, unfortunately, a man. This could happen in real life, but not in a melodrama, where narrative conventions (and viewer expectations/desires) demand certain outcomes. Some treat conventional narratives as inherently conservative, but I think that they can actually function in a more radical way. In this case, consider how “Coffee Prince” treats identification with regards to the straight male viewer. He can, of course, identify with the female Eun-chan, but the “natural” point of identification is Han-gyul: he is, after all, attracted to a heterosexual woman. But he doesn’t know Eun-chan is a woman, which means that any straight male identifying with him has to ask himself that important question: Would I still love her/him if I believe she/him was a man?

The straight male viewer cannot simply play this case of mistaken identity off, such as by saying “Well, I would have realized she was a woman.” Importantly, Han-gyul never finds out that Eun-chan is a woman until after he professes his love for her/him and says that he no longer cares if she/he is a man. This would make the average straight male cringe because it is essentially admitting that you could be attracted to (what you think is) a man and that, in this case, emotional connection and physical beauty (abstracted from gender) transcend one’s identification as a heterosexual. For the typical heterosexual male, this show has a potentially queering effect that is impossible to displace. There’s really nowhere to hide from the consideration of whether or not he could be attracted to another man. It helps that the actress who plays Eun-chan, Yoon Eun-hye, is not only stunning beautiful but, more importantly, androgynously so. Outside the context of the show, when she wears her hair long and has on conventionally feminine clothes, Yoon is unmistakably a woman. But with her hair short, her breasts bound, and wearing the male Coffee Prince uniform, she really does look astonishingly like a boy. In fact, the series opens by showing Eun-chan delivering food—one of her many jobs—to a female bathhouse, where she is mistaken for a man and causes a panic in the all-female locker room. Later on, she gets mistaken for her sister’s male suitor by her sister’s boyfriend, who later works with Eun-chan at Coffee Prince and becomes one of the first people to find out about her secret.

What is the real issue, then, in Han-gyul’s sexual confusion? We accept that he is a relatively normal straight male, even after his attraction to Eun-chan begins, because we know the truth all along and so we can play it off as a case of Han-gyul’s mind, which takes Eun-chan for a man, in battle with his libido, which perhaps instinctively takes her for a woman (because even if she was a man, she would be a rather pretty and feminine man). But this is not altogether accurate either. If the libido is something we take to exist, in some form or another, does it really have any sense of gender? What are we attracted to in other people? Surely it’s not just the presence or absence of a penis. (And if we expand our consideration to include transgender persons, then genitalia is quite a reductive starting point.) If it’s not necessarily what’s underneath Eun-chan’s clothes that attracts Han-gyul to her—and this being a K-drama, that doesn’t really come into play until much later on in the series—then is it merely her undeniable beauty and lovable personality? This suggests that there are two ways to consider the concept of attraction: are we attracted to how others look and act or are we attracted to what they are, on some more fundamental level? (And obviously, it’s always perceived as a combination of the two.) Han-gyul likes everything about Eun-chan (how she looks, how she behaves, etc.) except for that one fundamental trait that he thinks she possesses: maleness. Ironically, he clings to this essentialist view yet also gets it absolutely wrong.

Consider two Korean celebrities whose gender/sexual identities complicate this dichotomy. Recently, the K-pop boy band named NU'EST debuted, and one of their members is a startlingly feminine-looking man named Ren. Surely, he’s a lot “prettier” than some women, so does that mean that it would be acceptable for straight men to be attracted to him? (Hold your horses, bros: he’s only 16!) If we used the standards of beauty that women are judged by, surely Ren would score pretty well in any evaluation of his looks. He’s something of a male analog to Yoon Eun-hye’s androgyny. And like Yoon playing Eun-chan, Ren confronts the average heterosexual male (at least in North America, as I don’t have a sufficient understand to how these dynamics play out in Korea) with a disturbing fact: men can acquire the same qualities, e.g. “prettiness,” that the heterosexual male prizes in women. This doesn’t negate the differences between men and women, but it sure makes the preference for one over the other seem just a bit more arbitrary. And then there’s the case of a Choi Han-bit, a post-op transsexual supermodel and actress. Unsurprisingly, given that she is a supermodel, she is quite beautiful, but how are conventional straight men “supposed” to react to her? I gather that the attitude toward transsexuals is somewhat different throughout Asia (where there are, for instance, transsexual pop stars) than it is in the United States, where gender and sexuality are tied together in what seems like a much different way. For the conventional North American straight male, Choi now has the “proper” genitalia, but of course, it would still disturb some men to think of her as someone who was born with a penis.

The rules that govern heterosexuality are quite strict (again, often arbitrarily so): sex must be good ol’ fashioned penis-in-vagina intercourse (but only “natural” vaginas, not “artificial” ones). Anal sex is permitted every once in a while, but it’s dangerous to get too carried away: after all, men have anuses too. “Coffee Prince,” being a K-drama, doesn’t focus very much on sex at all, but it nonetheless succeeds in teasing these rules governing sexuality, loosening them up. In the West, there’s an implicit assumption that truly radical or progressive works of art are those that are most explicit. We even carelessly equate explicitness with progressiveness. How could a work of narrative art (“narrative art” being strike one) like “Coffee Prince” be daring and radical if it doesn’t confront you with the physicality of non-heterosexual love and sex? It’s true that “Coffee Prince” is not very confrontational, disturbing, or unsettling. If it is radical in any way—and I think this should be judged not as an inherent trait in the work itself but as a potential to be used or experienced by certain viewers in radical ways—it works by way of seduction, the long con rather than the quick mugging. The strength of conventional narrative works like “Coffee Prince” (or any K-drama) is in its willingness to speak to viewers on a level equal to them, not in any esoteric way. The world of “Coffee Prince” is our world, and this is why melodramas and rom-coms inspire so many people to apply their narratives to everyday life.

More dialogical, then, than it is confrontational, “Coffee Prince” is, in many ways, all the more powerful in its treatment of gender and sexuality precisely because no one takes their clothes off, leaving everything to our imagination. As in any melodrama, the passion between Han-gyul and Eun-chan mounts as the series goes on, pushing closer and closer to moments of physical contact. In one scene, Eun-chan falls asleep at Han-gyul’s apartment, and Han-gyul caresses him/her in a manner than walks the line between brotherly/platonic love and full-on sexual attraction. There are funny scenes where flashbacks to earlier moments shared together comically hint at the way Han-gyul’s libido is utterly perplexed by what’s happening to him (which is both funny and sweet to us, the viewers who know everything). And then there’s a great scene on the beach where Han-gyul and Eun-chan share a moment of intimate closeness, never crossing the line and touching each other in a sexual manner but always wanting to. Both of them seem to know what’s going on. In fact, we all do: he’s attracted to her but doesn’t understand why because he think she’s a guy. In characteristic K-drama manner, “Coffee Prince” treats this confusion demurely. The show is willing to let us fondly laugh at Han-gyul, but tension builds through the way his confusion is never fully verbalized. This is part of the K-drama’s seduction: as in real life, we are more apt to behave contrary to our own self-imposed sexual rules if we never consciously acknowledge what’s going on, acting more on feeling and instinct than thought.

In this seductive mode, “Coffee Prince” achieves something remarkably profound and radical in its own way. The series uses its focus on idealized love to temporarily distract us from contemplating the sexual appropriateness of Han-gyul pursuing Eun-chan despite thinking that she’s a man. And rather than treat the nude body as a shock device, as is often done in gender-bending stories like this, “Coffee Prince” portrays it as a mysteriously unknowable and undefined potentiality. The series seeks to supplant conventionally rule-based sexuality, which says that a straight man cannot fall in love with another man (or what he thinks is a man), with a softer, more romantic embrace of love as an erotic force that can unravel our own restrictions. The series’ temporary suppression of sexuality has the effect of nullifying the dynamics of conventional genitalia-centered sexuality because, for a moment, genitalia ceases to be a factor. The question “Could you fall in love with another man?” is too easy for the average straight male to answer because its answer itself is coded in the question: no, straight men don’t fall in love with other men (because that’s how heterosexuality works). But “Coffee Prince” doesn’t ask this question, substituting in its place something more like “Could you fall in love with this person?"—"this person” meaning that gender is temporarily suspended and all you have to go on is the combination of physical beauty and personality. This is a dangerous question for people to ask, and it is radical in the sense that if we all went around asking this question, and not the former one, all social and romantic life would be upended and changed quite drastically. Thus, in its shy reticence, in its seemingly conservative prioritization of love over sex, “Coffee Prince” goes a lot farther than the majority of narrative works in probing the questions about our gender and sexuality that we’re too afraid to ask of ourselves.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

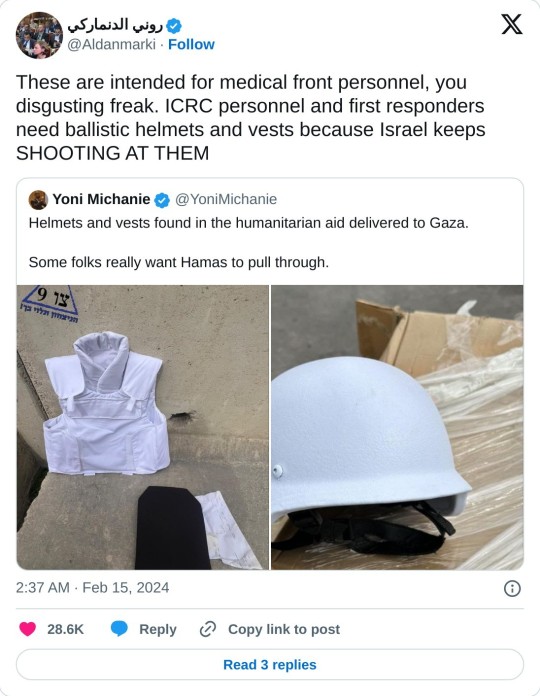

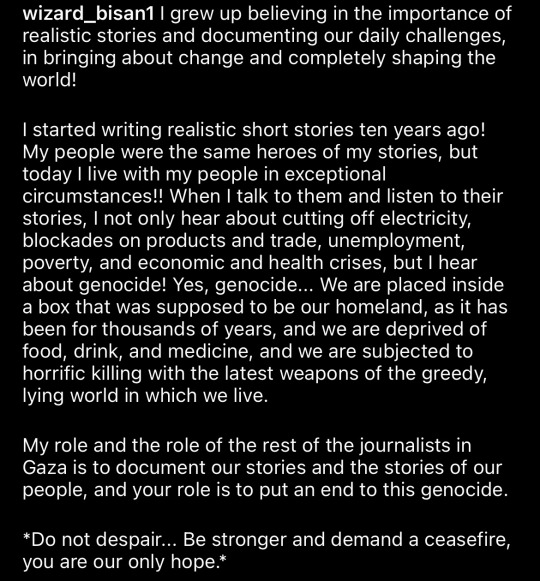

@/hindkhoudary on instagram

i tend to share posts from the reporters of gaza on this app whenever they post a caption or a story that brought me to tears.

i hope that it’ll reach the right people and move them as well

we need real change in this world we cannot keep living under this system

do not say you can’t do anything you can always do something

#selfishness and greed won’t get you far in this world#free palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#palestine#ceasefire now#we’re not free till we are all free#hind khoudary

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

60K notes

·

View notes

Text

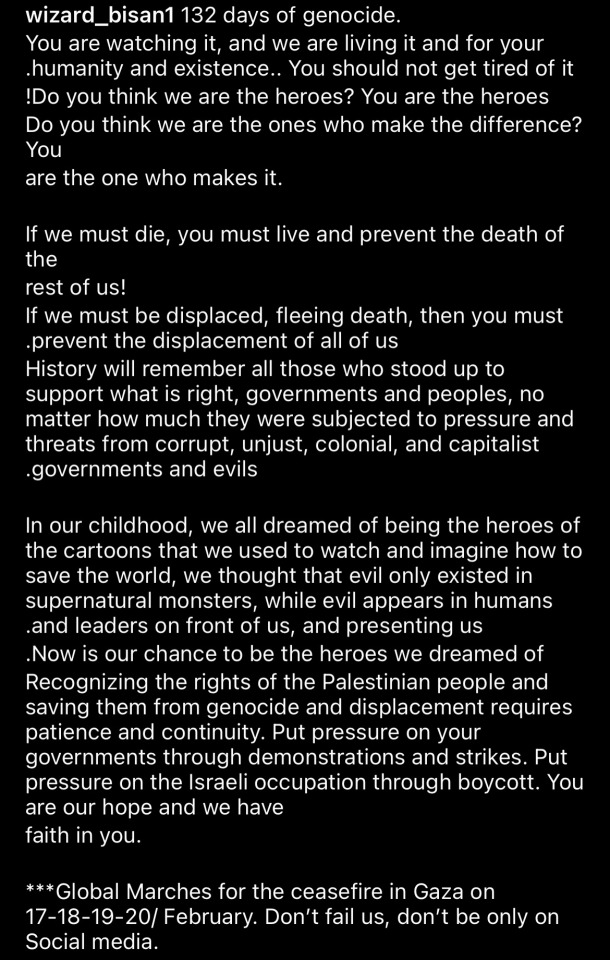

@/wizard_bisan1 on instagram.

Bisan is asking for a global march from February 18th through to the 20th! Talk to your local organisations let’s get this done for Bisan and all of the Palestinian people!!

#wizard bisan#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#palestine#we’re not free till we are all free#free palestine#ceasefire now#global march#protest#activism

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

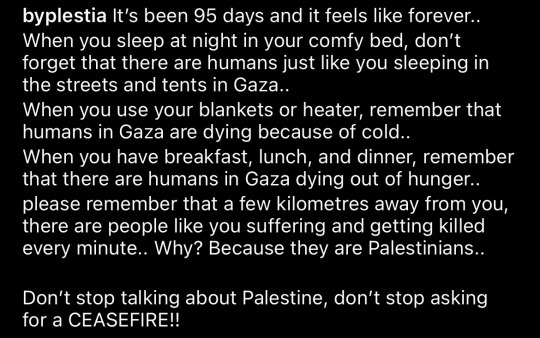

@/byplestia on instagram 🇵🇸

#we’re not free till we are all free#free palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#palestine#ceasefire now#plestia alaqad

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

from @/wizard_bisan1 on insta

i’m so so thankful for bisan and all the other reporters for taking the time to document the atrocities that happen to and around them we truly don’t deserve all they have done for us 🫶🏼🇵🇸

#i hate how the world has failed them#we must not give up please keep boycotting and keep calling for a ceasefire#we’re not free till we are all free#free palestine#ceasfire now#wizard bisan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@/belalkh on instagram

🫶🏼🇵🇸

#he went to get biscuits that his son was craving#then came back to find out both his wife and son had died from IOF missiles#this broke my heart#we need a ceasefire#ceasfire now#free palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

@/ahmedhijazee on instagram 🇵🇸❤️

#free palestine#ahmed hijazee#palestine#don’t be afraid to speak up#the future is in our hands#this genocide needs to end#ceasefire#ceasfire now

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

art parallels

jeremy lipking, federico zandomeneghi, serge marshennikov, allan douglas davidson, svetlana tartakovska

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

i don't pay attention to the

world ending.

it has ended for me

many times

and began again in the morning.

― Nayyirah Waheed, Salt

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

Grief is the only proof that I love and I love well. Love and grief are actually intertwined with each other and as "Akif Kichloo" once wrote, "the opposite of grief is not laughter or happiness or joy. It is love. It is love. It is love."

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

“the word ‘love’ makes the most sense when used with you.”

#why’d he say this beautiful ass line and LIEEE#only friends#bl#drama#thai bl#thai shows#quotes#academia#dark acadamia quotes#academia aesthetic#dark acadamia aesthetic#love#gay

0 notes

Text

“even in an ordinary life there are times when something sparkly floats by. at those times, you must not miss it, and keep it carefully in your star pocket.”

#because this is my first life#kdrama#quotes#academia#dark acadamia quotes#academia aesthetic#dark acadamia aesthetic

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

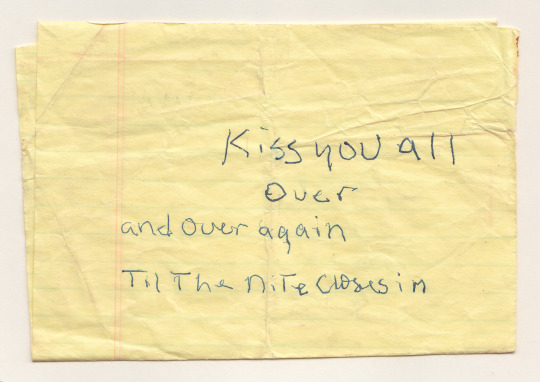

This note was found in New Orleans.

Kiss you all over and over again Til the nite closes in

550K notes

·

View notes

Text

“words are born form a persons mouth and die in a persons ear. but some words don’t die, they go into a persons heart and continue to live.”

#because this is my first life#kdrama#quotes#academia#dark acadamia quotes#academia aesthetic#dark acadamia aesthetic

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

“but there’s one thing i’m sure of a heart isn’t something that is taken or grabbed. it just comes to you.”

#someone ask the writers why they wanted me to cry so much#this is honestly a concept more people to grasp about love and dating and marriage#god this show is beautifully written#because this is my first life#kdrama#quotes#academia#dark acadamia quotes#academia aesthetic#dark acadamia aesthetic

9 notes

·

View notes