Text

Native American peace pipe.

Add more info.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Ojibwa tradition: 'The Snowshoe Dance', performed at the first snowfall every year.

George Catlin, 1835.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buffalo hunt pictograph, c. 1800s.

Region: Idaho.

This nineteenth century depiction of a buffalo hunt is painted in the traditional way, using pigments and elk hide. Exclusively executed by Shoshone men, pictographs like this were originally used to make a record of the warriors’ bravery in battle, but by this period many recorded their exploits using paper notebooks and ledgers taken or captured from the white man.

A buffalo hunt is depicted here, showing horseback riders driving a herd over a cliff. Before the introduction of the horse in the mid-seventeenth century, the buffalo would be driven by men on foot into corrals placed at the top of ravines, where men hiding nearby would frighten the buffalo into stampeding over the edge. The use of the horse obviated the need for corrals, as the animals could be chased straight over the cliffs. This was probably one of the last depictions of a buffalo hunt before 1869, when the Transcontinental Railway was completed – giving the white man easy access to the vast herds of plains bison. Within 15 years, the buffalo was on the brink of extinction, and the entire way of life of the Native American was destroyed. The subsequent wholesale removal of the indigenous peoples to reservations led to a sharp decline in these colourful pictographs.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 186-67.

#Native American#Shoshone tribe#bison#American buffalo#hunt#pictograph#art#traditional crafts#horse#Transcontinental Railway

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hopi basket, c.1800s.

Region: Arizona.

The Hopi are a Pueblo people, named for the are they inhabited. They continued the tradition of basketry that reaches back to the ancient peoples of the area. Basketry artefacts of the ancestors of the Pueblo tribes has been discovered ere, and these peoples have been dubbed the ‘Basket Maker Culture’ by archaeologists.

The trade network of the Pueblo extensive , and the decoration of goods was much influenced by contact with other cultures, including Mexican. Basket-making was exclusively carried out by women, whose wisdom and knowledge of the craft was essential for the making of quality bowls and baskets used and traded by the tribe. They understood the ecology of the surrounding area, and knew where the plants used in the making of the fibres could be found. They made assessments of the value of the materials and prepared them for specific uses. Many plants were used to make fibres from which the baskets were woven, including roots and grasses. The material chosen depended on the function of the basket – whether it needed to be particularly strong or water-retentive. Baskets were used for cooking until superseded by clay pots; the fibres were very tightly woven and any liquid they held would cause the material to swell and so retain it. Hot rocks were then put into the baskets to cook the contents.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 182 – 83.

#Native American#Native American women#Hopi tribe#Pueblo#traditional crafts#trade#basket#cooking#Arizona#utensils

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

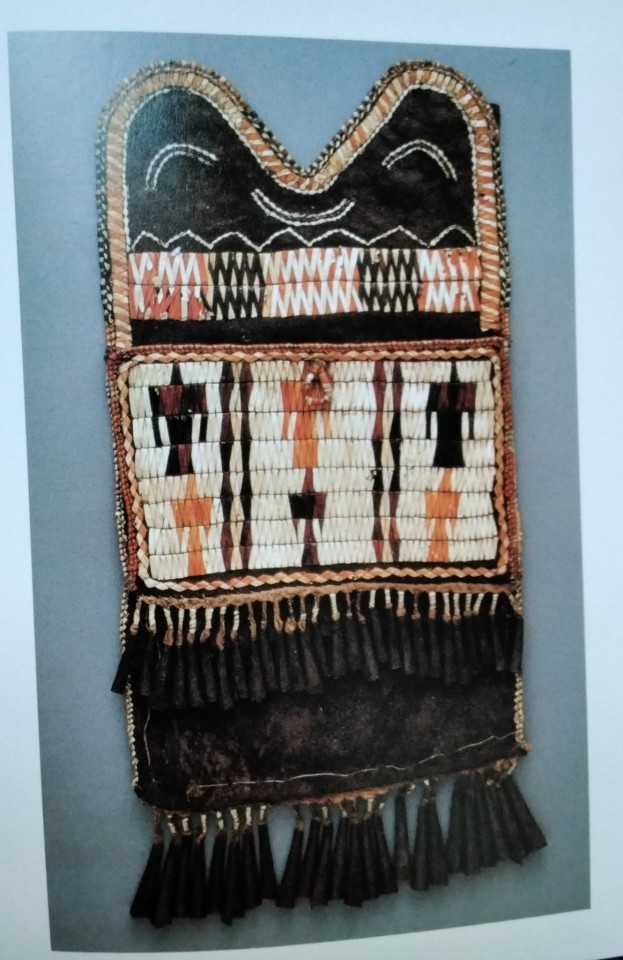

Sioux pouch, c.1800s.

Region: Northern America.

This nineteenth-century Sioux pouch is made of duck skin, and was probably used to hold tobacco and pipes. It is decorated with a symmetrical geometric quillwork design and three representational Thunderbirds. The Thunderbird was a powerful symbol in some Native American mythologies – a gigantic eagle-like bird that caused awe-inspiring thunderstorms by the flapping of its wings, and lightning flashed from its eyes or beak. It is possible that the story that some Sioux warriors came upon the body of a gigantic and fearsome bird with a bony crest on its head, is based on the discovery of a Pteranodon fossil in the rocks.

The porcupine quills that were traditionally used to make the rectilinear design shown here were sewn on to leather by women who would soften and flatten the quills by drawing them through their teeth. The quills were then dyed. The tassels that they hung from these pouches were generally cut from deer hooves.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 184-85.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

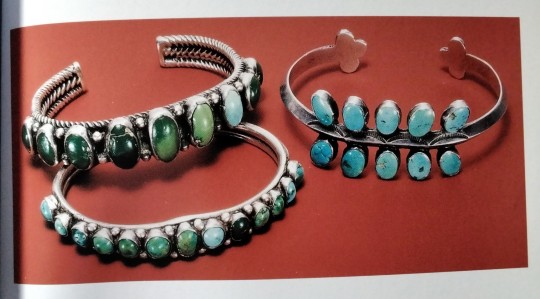

Navajo bracelets, c.1800s.

Region: South-West America.

These fine silver and turquoise bracelets were made by Navajo artisans at the time of the genesis of this kind of jewellery-making. The Navajo had fashioned jewellery out of semi-precious stones and shells for hundreds of years when they were shown the possibilities of silver – a new metal brought out of Mexico. An early Navajo blacksmith began by using silver coins to make jewellery, and early items were cast in clay moulds. These simply made items were decorated by scratching or incising designs, but soon more elaborate jewellery was made using mounted stones. Some of the first items to be decorated in this way were headstalls for horses. This was followed by bracelets, necklaces and many other beautifully adorned items. The south-west of North America is a significant source of turquoise, and this tribal industry was transformed. A tremendous flowering of this art continued into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 192-23.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crow war-medicine shield, c.1800s.

Region: Montana.

This nineteenth-century war shield was made by a member of the Crow tribe. The shields used before the Europeans introduced the horse were very large and could sometimes cover two men. Smaller and more practical shields were used by warriors on horseback, but the protection they offered was not dependent entirely on their physical properties. Protection was also afforded by a personal spirit. In this case, the moon spirit, which was always depicted as a skeletal figure. Before he could be deemed worthy of possessing such a shield, a warrior would spend days fasting and passing into trances. He would be visited by a spirit who would teach him its powers. When the warrior emerged from his trance, he would make his shield and point it with a representation of the spirit he had seen. The shields were made from animal hide – this one has been made of buffalo skin, and has been decorated with eagle feathers and a crane’s head, both of which had magical properties.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 194-95.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Penobscot powder horn, c.1815.

Region: Maine.

The Native Americans used horns like this one to carry gunpowder. The horns were taken from a variety of animals. But bison were most common. The Native Americans put the bison they hunted to many uses – as well as food, their skins were used for clothing and shelters. The horns and bones were used to craft all manner of items, including spoons and cups. To create the powder horns, they were hollowed out, and often carefully decorated with patterns and engravings, and tipped with brass like this one. A circular piece of bone was often attached to the top to cover the opening and prevent the gunpowder from falling out.

Powder horns really only came into common use after the arrival of the Europeans. With the fighting that ensued, most Native American men carried with them a powder horn and a shot bag, carried across the shoulders on a wide strap. This powder horn comes from the Penobscob tribe, who lived in the area around Penoscob Bay and the Penoscob River in what is now Maine. They were active in the frontier wars against the new settlers in this part of the country.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 196-7.

#Native American#Penoscob tribe#powder horn#horn#gunpowder#bison#American buffalo#traditional crafts#Maine

1 note

·

View note

Text

Creek or Seminole shoulder bag, c.1820s.

Region: South-west Woodlands.

Intricately decorated with embroidery and glass beads, this bag has the wide shoulder strap typical of a bandolier or shot bag. The nomadic lives of many Native Americans meant that they needed to carry their possessions with them, and various pouches and bags served particular purposes. Some were used for carrying gunpowder, others were used for transporting paints, medicines or tobacco.

Earlier bags and pouches would have been made from animal skins and decorated with beads that had been carved from bones and teeth. Shells and stones were also used, and more rarely, amber or pieces of coral. With the advent of the European settlers, who introduced coloured glass beads, these traditional methods waned in popularity and cloth-based bags were made for trading. The decoration on this bag uses non-traditional glass beads exclusively, but the pattern is typical of the people of the South-Eastern Woodlands.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 198-9.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Haida sailor mask, c. 1850s.

Region: North-East Coast.

This Haida mask, depicting a red-haired European sailor, demonstrates a remarkable fusion of ancient Native American traditional culture with the outsiders who came to trade and settle in North America. The Haida had a rich artistic culture, and this is exquisite example of their work. Probably carved in cedar wood, the hair and beard are realistically rendered and painted, and the freckles are inlaid with glass. The maker may have heard of a story that a Native American girl once saved the life of a red-haired sailor, but the realism of this carving suggests that it was probably based on the artist’s own observation s of European sailors and traders. Unfortunately, this contact with Europeans had less benign influences: the native population was devastated by smallpox, influenza and other diseases previously unknown to them. After 1774, when they experienced the first contact with Europeans, 95% of the Haida population was wiped out by epidemics, and by 1915 the population comprised just 558 individuals.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 204-5.

#Native American#Haida tribe#traditional crafts#mask#European#sailor#small pox#influenza#epidemic#North-East Coast#folk art#art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crow quiver and bow case, c. 1850 -75.

Region: Montana.

The real name of the Crow tribe who this bow case and quiver is Apsaarooke or Apsaarookee, and they were a small tribe of Montana hunters whose lives centred upon the great herds of buffalo. They were an independent and warlike people who distanced themselves from neighbouring tribes. They took great pride in their reputation as fine hunters and likened themselves to a great pack of mountain wolves who would sweep down upon their enemies. They used animal hides for clothing and their lifestyle meant that their artistic and creative expression manifested itself in decoration of clothing and various carrying pouches such as this quiver and bow case. Fine, soft leather and fur such as otter skin was ideal for all kinds of pouches. The women of the tribe would work beautiful designs on to all their menfolk’s accoutrements, using glass beads in brilliant colours. There was great competition to make their husbands the most splendidly clad.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 206-7.

#Native American#Crow tribe#traditional crafts#Apsaarooke tribe#Apsaarookee tribe#Montana#bison#American buffalo#quiver#bowcase#hunt#otter#Native American women#beads

1 note

·

View note

Text

Potowatami spoon, c. 1870.

Region: North-east America.

This wooden spoon was made by the Potowatami who lived in north-eastern America. Even after the arrival of the new materials introduced by the Europeans, wood remained the favoured material for eating bowls and spoons or ladles. Nomadic people needed lightweight utensils and families would treasure their stock of bowls and spoons. In earlier times, bowls for every day use and for feasting, as well as spoons, were hollowed out of a burr of wood by burning t with hot cinders and then scraping away the charred wood. Spoons and ladles usually had animals carved on their handles, as does this example which dates from around 1870. The spoon was probably not shaped by the charring method but by the use of an adapted European blacksmith’s knife. It was reported by a contemporary observer that those men who were less skilled at hunting deer for trading, carved tulipwood bowls in order to exchange them with the hunters. In this way they obtained their skins. At the time the spoon was fashioned, many Native Americans had become famously skilled artisans.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 210-11.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sioux pipe bowl, c. 1880.

Region: Great Plains.

This is the bowl of a tobacco pipe made by Eastern Sioux natives. It is carved from the red catlinite traditionally used to make bowls of wooden stemmed pipes. Catlinite is a soft, easily carved stone that ranges in colour from light to deep red. It was used by the Sioux for ritual and ceremonial pipes and was regarded as sacred. Legend says that the Great Spirit stood upon a wall of rock in the form of a bird and the tribe gathered to him. The Great Spirit took a piece of clay from the rock and fashioned a pipe. As he smoked it, he blew the smoke over to the people. He told them that they had been made from the red stone and they must offer smoke to him through it. He forbade the use of the stone for anything but pipes. The Sioux used pipe smoke at every ceremony. Before beginning to smoke, the pipe-holder would cradle the bowl in his palm with the stem pointing outwards. He would then sprinkle a little tobacco on the ground, giving back to Mother Earth what they had taken.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 212-13.

#Native American#Sioux tribe#traditional crafts#catlinite#pipe#ceremonial#legend#Great Spirit#tradional crafts#tobacco#Great Plains#Native American mythology

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Navajo chief’s blanket, c. 1880-90.

Region: South-West America.

Amongst the Navajo, weaving has traditionally been done by women. It regarded as a sacred art; the universe was created by a mythical ancestress known as Spider Woman, who wove the universe on a great loom. However, the woven textiles and designs of the Navajo tribe have no sacred significance. Early blankets were made using cotton and the wool of the Chinna sheep, using traditional upright looms. A Navajo would carryout all the processes of producing blankets, from shearing the sheep and spinning the wool, to dying and weaving. Many women kept large flocks of sheep. As with many traditional crafters, the Navajo weavers were quick to use the innovations introduced by European settlers, specially the ‘Germantown’ commercially produced yarns. These yarns, named after the town where they were produced were extremely fine and superior to the native yarns. The chemically produced dyes prompted a great change in the colours and patterns of the Navajo; the early, simply striped blankets of the first phase were superseded by exciting new designs in brilliant colours, known as ‘Eye Dazzlers’.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 214-5.

#Native American#Navajo tribe#traditional crafts#weaving#wool#blanket#chief#Native American women#Spider Woman#Chinna#sheep#Germantown

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chippewa awl, c.1890.

Region: Great Lakes.

The handle of this nineteenth-century awl (tool used for piercing holes, especially in leather) was carved from deer antler by the Chippewa or Ojibwa, tribe of the Great Lakes area. Generally, the Chippewa people decorate their carved pieces with stylised animal representations, rarely using anthropomorphic designs (h i.e. the animals did not have human attributes). However, the human hand shape of this handle was also common amongst this tribe. It can be seen on some of the many ‘crooked’ knives that were used. These utilized the European blacksmith’s knife – used for shoeing horses - -which was bent to make a useful curved blade. These were widely adopted to carve out bowls and spoons. Previously, a lengthy and painstaking process was involved in carving out concave shapes; a burr of wood would be burnt with hot cinders and the charred wood scraped away by the use of beaver incisors set into a handle of wood or antler. Other knives and tools, such as planers and this awl greatly improved the efficiency of tribal handiwork.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 216-17.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arapaho war bonnet, c. 1900.

Region: Great Plains.

This splendid eagle-feather war bonnet belonged to the last great chief of the Arapaho, Chief Yellow Calf, who died in 1935. War bonnets like this one served a ceremonial purpose only and were usually made up of a cap or band with a long trail characterised by these erect feathers. The two colours of eagle feathers signify light and dark, daylight and night, summer and winter. The large feathers represent men and the small ones women – and they are greatly treasured.

The eagle is a sacred bird in many Native American belief systems. He is the messenger of the Creator, and legend tells how eagle feathers came to be used by the Native Americans. A solitary warrior was visited by seven great eagles who showed him how to make the war bonnets that would bring his tribe victories. Since then, the eagle has been a symbol of honour and feathers are given as prized gifts. It is considered a sign of good fortune to find an eagle feather and the possessor will always treat it with respect, giving it a place of prominence in the home. The feathers must never be mishandled or destroyed.

Source: ‘Folk Art’, Susann Linn-Williams, pp. 218-19.

#Native American#Arapaho tribe#war bonnet#eagle#feather#traditional crafts#ceremonial#chief#Great Plains#Chief Yellow Calf

4 notes

·

View notes