Text

Navigating the L2

An exploration of my time as an L2 student, and my role as an ESL writing tutor within the writing center // reflection on IWCA 2016.

My first 24 hours in Spain were probably some of the most exhausting of my life, both physically and mentally. Physically, jet lag is a very real thing. A 7 hour time difference and almost a full day of travel with no sleep can definitely wipe you out. The city of Seville is also very walking-as-transportation centered. So my legs were tired and I was ready for bed. But mentally, my brain was working overtime, trying to think both in Spanish and English as I attempted to close the language barrier some.

I began taking Spanish classes in seventh grade and continued to do so all through college. I loved the language and was pretty decent at it, so I decided to minor in Spanish in college and continue my language education. While I still did well in Spanish classes, actually being in Spain was a whole new ballgame. Here's what no one tells you about study abroad in a Spanish speaking country: no amount of classes can prepare you for being thrown into the real culture and language of a country.

My entire Spanish education until college was based on Spanish spoken in Mexico. So when I got to Seville, I was completely at a loss for how to use the vosotros form that's so commonly used in Spain and I struggled to understand the fast paced and heavily accented language of the Sevillanos.

But trying to understand the Sevillanos was only half the battle- the few times I was able to tell what someone was asking me in that first day, I was too focused on understanding them to compose an answer in response. It was like everything I had ever learned about Spanish instantly was drained from my memory.

When speaking to my host family, I struggled to provide adequate conversation. While they were trying to get to know me, I was focused on giving a grammatically correct answer in the right verb tense with my limited vocabulary. So when they would ask what I learned in my class that day (I took a course called History and Culture of Spain while there) over dinner, I could only offer limited answers that barely skimmed the surface. (I was lucky enough to have a super kind host family who was patient with me, encouraged me, and tried to meet me halfway with their limited English).

And the worst part? This lasted almost the entire 3 week trip. At the end of each day I would flop into bed (after my 9:30 pm dinner) and feel incapable of thinking. I tried to journal before bed each night throughout my trip, but found myself unable to think of the words I wanted to use. My brain was exhausted and in this liminal space of trying to navigate between two languages.

When I was asked to write a 5 page research paper for the class I was taking abroad, I actually felt relieved because I could take my time figuring out the language and not be pressured to come up with content on the spot.

Traditionally, writing in Spanish has been a struggle for me. As someone who enjoys writing and typically excels at it (in English), trying to maintain my voice and style when writing in Spanish seemed almost impossible with my more limited vocabulary. I also tend to be a bit of a perfectionist- so knowing that I would have grammatical mistakes in my Spanish writing was both irritating and kind of embarrassing for me. I felt like I had a writing reputation to maintain and I didn't want to ruin it.

But in this instance, I was happy for the opportunity to have a break from verbal communication, so I took comfort in writing. The slower pace took off some pressure and made the process less exhausting than everyday communication and conversation. It felt safer and almost relaxing.

As a writing center tutor, when I was writing this essay for my study abroad class, I couldn't help but wonder what it would be like to have a tutorial in Spain. It would be the reverse of my typical writing center reality- I'd be the student instead of tutor, and the tutorial would have to take place in my L2 instead of my L1. That exhausting element of having a conversation in Spanish would be present again and take away some of what appealed to me about writing in Spanish.

My time in Spain ended 4 months ago, but just a few days ago I found myself exhausted again from traveling. This time, I was only a little jet lagged and sleepy as I attended the first day of the International Writing Center Association conference in Denver. I love attending these kinds of conferences because it helps to put writing center work into perspective- we are not just one center at one university, we are a part of a larger community/network of people who are all sharing in the struggles, joys, theories, and nuances that make up writing centers. Not only is there this aspect of commonality that makes the conferences appealing, but they are also jam packed with great information and ideas, too. This year there were literally hundreds of presenters ready to engage with anyone who wanted to listen.

One of my favorite sessions from the whole conference came from an undergraduate tutor from Saginaw Valley State University entitled "Revisiting the ESL Frontier: Tutor Perceptions of Multilingual Students in the Writing Center". Alison Barger presented her research on tutor perceptions of ESL students in the writing center. Her research suggested that tutors typically don't feel as successful or confident in their tutorials when working with ESL students. This stemmed not from reality necessarily, but from tutors feeling uncertain about whether or not the ESL student understood their feedback. So, a tutorial could have gone very well in actuality, but if the tutor couldn't gauge the student's level of understanding, then the tutor left feeling unhappy with the session.

While I can't say that every international or ESL student experiences trying to practice and learn their L2 (or 3 or 4) the same way I did, my experience in combination with Barger's research has given me a new perspective on tutoring ESL students: learning a language (and how to function within the culture and community associated with that language) is exhausting and complicated.

So I don't have a perfect plan, but I hope to use this research and experience to take a new stance in tutoring- one where I take the focus off of me and my success within a tutorial setting, and instead remember what it's like to feel stuck in that liminality of language. Writing is a completely different experience for everyone, and adding language into writing just creates a new layer of complexity. There is no method or fix or theory that can teach me how to perfectly work with ESL students, but now I feel capable of coming from a better place. A place where I have the capacity for compassion and can remember that we're all just humans trying to navigate this crazy, exhausting, exciting world made up of many languages.

--Gabbie Fales

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leadership

Hello! My name is Rachel Carroll and I am a tutor coordinator in the Writing Center. In simpler words, I work at the front desk. Last year I was asked to join the student leader board (SLB) which has impacted my semester a lot and has given me a lot more leadership roles. In choosing to write a blog post, I wanted to write something related to the Writing Center, but I also wanted to write something that would impact other students.

By definition, leadership means the action of leading a group of people or an organization; the state or position of being a leader. As an SLB member, I have been given leadership roles over the new tutor coordinators that we have hired this year and creating the schedule, training them, and answering their questions. This would have been a challenge last year when I was afraid to speak up for my opinions. However, being in a leadership role has helped to nudge me toward being more authoritative and confident in myself.

When I first came to Marian and started working in the Writing Center, I was very quiet and shy. I have always been introverted and starting in a completely new atmosphere was quite terrifying. As the year went on, I became more comfortable with the people around me, but I also became more confident in my ability to communicate with others. In taking on a leadership role, I needed to trust in my own ability to communicate and be confident in myself. This was difficult at first. However, as I look back at last year and then look at where I am now, I realize how much progress I have made. Now I am able to be myself at work and I can joke with the other students. Being a leader doesn’t make you separated from the rest of the community; it just gives you something more that you can do within the community.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

APA Online Workshop Update: We’ll have to postpone the webcast once we work out a few more kinks :(

Okay, we're going to try this out. APA Online Workshop, 8/31/16 at 8pm. Watch and participate here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sryEKKsPaTk

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thank You

Earlier this week, I stood up from my folding chair in the gymnasium and I practiced, with the rest of Marian University’s 2016 graduating class, the pledge we would recite (weather permitting and fingers crossed) on the football field during commencement. There were some chuckles and grins at the buzzword that appeared in it—we had all heard before that we were to become “transformational leaders” in the world after our time at Marian, and the pledge mentioned “honor[ing] the excellent teachers who transformed our lives.”

This touch of cynicism bothered me a bit. I understood that the words transformative and transformational had lost their punch and meaning over the years, as when you repeat a word too much or look at a word for too long and it begins to make no sense. At the same time, I knew that I had been transformed by the professors here, by my courses, by my classmates, and, especially in this last year, by the community in the Writing Center. To be transformed is really the whole point of going to a liberal arts university—to walk across the stage dressed in cap and gown as more thoughtful, informed, insightful, creative, compassionate, and empathetic people than we were when we came onto campus all those years ago, hauling mini-fridges and microwaves up the Doyle Hall stairs because there was no elevator and meeting neighbors for the first time while slipping past cardboard boxes filled with everything you brought from home.

For one thing, I don’t think that high school me, who was making leaps and bounds in confidence but who was still shy, would have ever guessed that, in college, she would spend hours each week sitting down with people she had never met before and talking about their academic and creative writing with them. At the Writing Center, I learned that, when it comes to transformational leadership, listening is just as important as speaking. In taking a student’s work seriously and showing them that their ideas matter, in asking others questions and helping them to verbalize their goals and thoughts, we empower them. I know that I would not be the writer that I am or the person that I am today without all of those who believed in me and in my work over these past four years. I have had the privilege and the joy of working with, laughing with, and learning with an incredible community of writing tutors. I have had the opportunity to learn from our amazing writing center director, who argues sincerely that words matter, that our purpose as a writing center is to make the world a better place.

As an English and history major, and as a peer writing tutor, I know that stories matter. I am so grateful for the funny and wonderful stories, from baby showers to long drives to conferences, from challenge poetry competitions to ugly sweater Christmas parties, which we have created together over the years in the Marian University Writing Center. I will take those stories and the lessons I learned from my time at the Writing Center with me wherever I go. They will inspire me, motivate me, and remind me that you can change the world (or at least change someone’s world) by listening, by being inquisitive, by naming things, by being sincere. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

--C.C.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At ECWCA 2016, several members of our staff attended a session on personality types and writing center work! The presenter indicated that the majority of tutors are NF types (intuiting and feeling--this seems to check out at our center!). Many tutors are introverts, which might seem odd, as tutors work so closely with others. The presenter explained that perhaps tutors see themselves as primarily working with a piece of writing, with the author of said writing present for discussion and deliberation. Finally, how much do we “play a part”--is our behavior in or response to a situation an unchanging part of our personality, or is it changing or covering our personality in the moment? How do we present ourselves, in line with or in contrast to our true personality, in a situation such as a tutorial session?

What’s your personality type?

#MU Writing Center#personality types#myers briggs#whiteboards#writing center#peer tutoring#know thyself#info courtesy of J.C.

0 notes

Text

On Sunday, April 10th two of the Marian University Writing Center Student Leader Board members will be walking in the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s Walk Out of Darkness on Butler University’s campus. The Marian University Writing Center places a lot of emphasis on our involvement in our community and in the awareness of those inherent qualities that humankind is concerned with. It is only natural that our Tutors and Tutor Coordinators, then, are those people who involve themselves in these causes in their time outside of the Writing Center. Rachel Carroll and KC Chan discuss how suicide has impacted their lives personally, and why they chose to participate in the Walk Out of Darkness.

Rachel Caroll:

Suicide is not a fun topic and it is horrible how many people lose their lives to suicide. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, approximately 117 suicides happen each day and this has been increasing over the years. My friends and I chose to join the “Walk Out of Darkness” Suicide Prevention and Awareness walk to show support and community for those who struggle with the temptation to hurt themselves and those struggling with mental disorders such as depression and anxiety.

I’ve struggled with depression off and on since seventh grade and I know what the temptation feels like. Depression can take all the good things in the day and twist them to make them seem bad or destructive. It’s like drowning in darkness and being afraid to reach for help. Some days it’s hard to even get out of bed. Other days I get out of bed and my body slowly shuts down to the point of feeling like I can’t even move or talk. Depression makes each day more difficult and it becomes harder and harder to fight.

I signed up for this walk because I know what it feels like to wish that everything would end. Recently, I wanted to give up because I was so tired of fighting my depression without it getting any better. Sometimes it feels like it will never get better, but there are people surrounding me who tell me repeatedly that it will get better. They have encouraged me to keep fighting. “Walk Out of Darkness” was designed to build a community and encourage people to see that they are not alone and that it’s ok to ask for help. It’s not easy to reach out, but hopefully by participating in this walk I can give someone else the courage reach out to others.

KC Chan:

There are a lot of circumstances in which those who have taken their own lives are cited as never having exhibited any symptoms.

And then there are those who very obviously have.

The problem is often not that someone didn’t make it obvious that they were unhappy, that something about them had changed, but that those around them didn’t know when or whether they should step in. So when I walk for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s “Walk out of Darkness”, I will be walking not only for those who suffer from suicidal symptoms themselves, but to create an awareness to those around them.

I was not diagnosed with Depression until I was 22-years old, but I have struggled with it silently since I was 14. When I tried to take my own life the first time, I was called dramatic. When I tried to take it a second time, it was never acknowledged. I was stigmatized by my family, my friends, and even a nurse practitioner.

And I think it is important to acknowledge that there is more than one way the we try to kill ourselves.

There is the physical way, the actual taking of a life.

And for me, when that failed there is the spiritual way. The symbolic way. The Intellectual way. The way of choosing to continue to exist in that state of non-existence that so often leads to suicide, and it cycles back on itself.

I think that those who suffer from depression are often so immersed in monotony that suicide becomes a viable option because it is one last resort way of feeling something.

I live everyday with the awareness that at any moment, some force of nature is going to take a hand mixer to my thyroid. I revel in the glimpses of happiness I have, when I glow a little bit and participate in conversation, because I recognize that at any moment, I can be pulled back under. I will be forced to return to the place where I overthink every gesture, where eye contact makes me feel far too vulnerable to function. Where time moves too slowly and all at once.

When I discovered that Rachel was walking in the Walk Out of Darkness, I discovered that once again, I was not alone. Not only that, but that a community of people like me existed much closer than I had realized. And that community could someday be the key to someone’s survival. On the day of the walk, I showed up on campus unprepared for the cold and the rain, and I noticed that no one else was there. I hid inside the nearest building, waiting for the time that the walk would begin, and when I slunk back to the starting line, suddenly a crowd had appeared. This silent community had suddenly sprung fourth—reminding me again that those who struggle often go unseen until they choose to make an appearance, and that that community is always present, and I am a part of it.

I struggle with depression every day, but today, I looked through some photos of everything beautiful in my life-- My daughter, my accomplishments, my friends, my strength.

And I have found my reason to live.

I fell in love with this picture taken during the AFSP Walk(Right)because it is the first picture that I have felt completely comfortable in my own skin, and I found beauty in something as simple as my own happiness. I have struggled with my appearance for so many years, and pictured here is a victory.

#MU Writing Center#Walk Out of Darkness#American Foundation for Suicide Prevention#Butler University#Marian University

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Roots: A Brief History of the Marian University Writing Center

Most of us— and by that I mean those of us who attend mandatory meetings— have heard other, more senior, Writing Center tutors say it at least once. “There’s a whole new world out there, tutors. A dazzling place you can only understand if… you go to a conference like we have.”

“Writing Centers are kind of a thing,” Gabbie says during the peak of the meeting. Her head is tilted slightly to the right, just so… she is feigning a determined innocence in a remarkably useful rhetorical head-fake. Without your noticing, in the short pause between words she has sat up straight, and the whole moment shifts. “Our Writing Center is ahead of the curve on so many things,” she says, dropping all pretense that someone in the room could not be paying attention, speaking of a world that she and the other tutors she gestures toward are now a confident part of. And through the ad hoc group presentation that ensues with Gabbie and Alyee and KC, there are a few lines of questioning remaining untouched— Which things? Why do we do them and others don’t? How does one know we’re ahead of the curve, rather than behind it, or run through the wall and into the crowd? Well, they’ll tell you, the conversation implies, like they told others in their conference presentations. But it would be better to attend a conference and see for yourself.

This is the main batch of revelations that come about when students from the Marian Writing Center attend a regional or national conference on Writing Centers— that, first off, “there are others?” and second that ours is somehow doing things differently. But I want to tell you that the fact that we do things differently is no accident, and it is surely not just because Mark(1) woke up one day and said “man, I feel like the writing center should serve the community as a mode of learning.” Today, the Writing Center functions on a set of principles deliberately chosen. That is to say, that there are several words that tend to come up when the Director and Assistant Director get together with the Student Leader Board. They come out looking back on years past. They come out looking at what we’re doing right now and whether it’s successful, needs tweaking, or needs scrapping. And they come out in conversations surrounding that foggy future and all its contingencies. These lines between future, past and present is of course an artificial one— as much so as the focus on several words as unifying vision principles. Anyone who enters the Liberal Arts arena and stays for more than a few hours recognizes that even within a single term there is a baklava of alternating negative and positive connotation, and those connotations— both positive and negative— matter. It is also important to recognize that these connotations are shifting, and words that work now stand a good likelihood of not working in the future, or may become less useful as their purposes or the surrounding scholarship continues to grow and change. Our words, if you’d like to know, are agency, advocacy, and ownership.

These terms have arisen, I think mostly over the past couple years, as having a concretized necessity not only within the Writing Center but through Marian University’s Writing Futures program as a whole. But that doesn’t mean that it hasn’t been a unifying principle for years and years, or even when they were not part of a unifying coherence, an inherent component of the Marian University Writing Center structure. There is a long bag that drags behind our Writing Center, as Robert Blythe(2) or Carl Jung(3) would both say in their discredited psychological manner. And, like Blythe and Jung, mixed in with the brilliant poetry and translation, and insight into human nature that stood the test of time, there’s going to be some quackery that was understood as brilliant at the time, but later fell out of favor for some pretty good reasons when looking at it in 20/20. I hope that this short piece can answer for both, and everything in between.

“It was a different time,” I told Alyee through laughter, just this morning. I think I can officially say that now, since students who don’t know me have transitioned from asking me “what year are you?” to on bulk something more like “What classes do you teach?”

“Right?” she says, instinctively agreeing from half-attention. She’s doing me the kindness of listening, while the greater half of her attention rolls through the two dozen timesheets she’s sorting through. We’re very near the same age, Alyee and I. But of course as far as Marian is concerned, my era as a Writing Center tutor is near ancient history. That was a time before any of our current tutors, before any of our current Lab Instructors, before the current Lab Hour job description hinging on Discourse and Community, and before Mark and Community Engagement initiatives. In fact, there may only be three shared actors in common between the Writing Center then and now: Me, Dr. Crossley, and that desk where Alyee sorted timesheets.

It was still “Marian College,” then. “Marian University” was still a couple years in the making. The words of the day were “Critical Thinking.” How do we get students to elevate their game— not just for this paper, but all the rest of the games they play thereafter? Knowing what I know now about how the brain integrates new concepts, particularly when it comes to writing, we were hunting a magical unicorn. But we sure talked a big game in the Writing Center. “We want to raise the level of scholarship,” Cliff would regularly say during both team and private meetings, and the tutors did their best to keep things elevated— philosophy and theology (often using actual logical notation) was the common language, and the vocabulary was always a show of bravura, if occasionally its intrepidity verged into grandiloquence. Aristotle, Plato, Kierkegaard, DesCartes, Sartre were where we matched our Discourse. And matching the characters who worked there were the characters on the walls: The Philosoraptor was a favorite. The Kantosaurus, another. The Camusognathus was in a state of constant existential angst, and occasionally one of these varieties of thunder lizard would find himself caught in an epistemic circle. Stephen North had a mystical, unfelt presence, even though his words were nowhere on the physical space of the writing center itself. Until, when you began a tutorial, North’s presence made itself unambiguously known— “Our goal is to make better writers, not just better papers” screamed the bottom of the paper tutorial report form. Literally hundreds of paper report forms stacked throughout the room, saying over and over, every tutorial, “Our goal is to make better writers, not just better papers.”

“The Writing Center isn’t just a center for writing, but for knowledge,” Cliff would say. “We recruit the best thinkers on campus, because we can teach them to be great tutors.” And that was a point of pride for us. We were a storehouse of clandestine knowledge, a garret of waiting genius looking to reach into as many waiting minds on campus as possible and enlighten them into this greater Truth of the University.

There are obviously some portions of this system that we can point back to and recognize as problematic. The Storehouse and Garret models of the Writing Center privilege certain varieties of knowledge and epistemologies, in this case philosophy, theology and academic and colloquial versions of Standard Academic English, at the expense particularly of sociological and communal knowledge and language, and that privileging can often have an inherently racialized component, just as it can inherently have a component that stigmatizes poverty and legitimizes hegemony and the myth of purist meritocracy. None of this, of course, was intentional, and in fact there were direct attempts made to act against these potentialities of the garret/storehouse writing center models through conscious initiatives. Cliff(4) stressed, and students echoed, the need for acceptance in growing the accessibility of the Writing Center, while still maintaining the insular community where a student entering the writing center might have to ask “who’s working now?” because while there were two tutors on the clock working with students, six other tutors were in the space carrying on a conversation about heuristics. And whether these efforts were able to counteract the structural effects of the storehouse/garret models notwithstanding, they were in conscious effort.

It was from this insular camaraderie that valued conscious outward movement that Cliff created a very particular program. It created the ability for the Writing Center to undergo quick and drastic change, organically from the student level upward as well as from the Director downward. In fact, it had first begun in a different space(5)— a smaller, more intimate seventies-y space in the basement of the library, amid the purple and orange patterned carpet and concrete walls unfinished and wet, and exposed piping painted purple just a couple inches from the Cliff’s desk in the center of the room— but really came into its own in the basement of Clare Hall(6). It was the “Writing Scholar Internship,” and I would argue it was one of the most successful programs in the Writing Center’s history, because of the way it democratized that outward movement of the Writing Center. “I want to push down the responsibility from the administrator level to the student level,” Cliff said to me when the program was in its infancy, “and we’re figuring out how to do that. A lot of research has shown that when you push the responsibility downward, a lot of cool things can happen.” He would look up at me sideways past his glasses, and smile a mischievous smile that could mean many things— but always meant more than you knew at the time.

Writing Scholar Internships were inherently designed to expand the reach of the Writing Center and bring in more tutorials. Any internship that could prove a causal increase of 20 tutorials was determined a success on that front.(7) We were in it to bring more students into our range, and more students in range meant that we could disseminate our Truth to a wider audience. The problem for the interns to solve themselves was, how do I do this in ways that Cliff— a writing center director with an eye toward innovation— had not already thought of? And this led through the back door to students who wanted to take on Writing Scholar Internships looking into very current research on Writing Center Theory and Administration, to see what other schools were doing, thinking outside the box, and being incredibly creative in divining brand new wells to tap for more students to tutor.

But perhaps most importantly, in all of these Writing Scholar Internships there was a stated expectation of self-directed scholarship, a faculty member who would be consistently in your corner and an understanding that whatever came of that internship, it was yours. While the words of the day may have been different, the Writing Scholar Internships brought to the Writing Center a focus on agency, advocacy and ownership that may otherwise not have been fostered outside of an insular community of a few Writing Center tutors— and along with it, laid the bedrock for challenging the standing privileging of certain funds of knowledge at the expense of others.

“I used to be so shy,” KC said to me— the two of us had each been occupying the same space, but only in the most technical sense of the term. We were probably only four feet apart, but I was looking down at my own computer, and she at hers— facing opposite directions.

“Huh?” I said, swiveling in my chair. I had been reading some Paulo Friere, and was a bit into it.

KC looked up through her bangs. She never seemed to brush them off to the side— but somehow looking through bangs seems so “her” that there were no questions. “I just used to be so shy. Like… I never talked to people. I would never have written any of this,” she pointed to her computer screen. “But it just seems so natural now.”

“Well, that’s pretty cool,” I said. “I guess I’ve never known that other KC. I never met you until I was working here as a Lab Hour Instructor.”

“Yeah, that’s true,” she said, looking for some reason toward the wall at the back of the room. She smiled, thinking something just for her. I shrugged, and dove back into my reading, both of us going back into the comfortable space-sharing that only comes with familiarity.

I first met KC during my second stint as a lab instructor, during a community event just off Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard a few miles southeast of campus. Mark Latta was running the event and acting in the role of Assistant Director of the center. This was our first time seeing each other since he’d started his new position.(8) Under Mark’s direction we were working on collecting stories from the community— a new initiative he’d brought to the center. Cliff loved it. For quite some time, he had been looking to take the Marian Writing Center off-campus, but lacked the words, and the framework within which it could be done. Mark provided those words, and provided that framework. And the best part— the framework, though it caused tensions in some places, fit in well with the direction the center had been going and offered the center a chance to potentially publish this community work and put Marian’s Writing Center on the map. The outreach on campus from the time before him had prepped the center for this type of move, but this, again, with the catalyst of Mark as the new Assistant Director, was movement that was in the process of remaking the center from within.

But the movement had been happening even before Cliff began taking the center toward on-campus outreach, and well before Mark ushered in community outreach. Back before me, and perhaps before the desk, and before most of the current Writing Center Employees even existed as people— all the way back to the Jurassic of the mid-90’s when our only remaining actor, Dr. Gay Lynn Crossley, left her doctoral program at Florida State for the chance to run a writing program at a small Catholic Liberal Arts school in Indianapolis.

The Marian University Writing Center was a relatively recent creation. It was a need seen by one David Shumate, Poet-in-Residence of Marian University, who acted upon the need for a central hub of writing on campus. He was responsible for the inculcation of the writing culture that inculcated successful poets and writers like Norm Minnick, who currently teaches in the English Department— for running student publications in the Mac Lab next door— and for the very culture that enabled the Writing program at Marian to thrive. Through these programs, he and the writers he worked with created a forum for students to uncover their own voice within the University and outside of it in the world of publications, with Dave knows well. The basement of the library was a hub of writing activity, and a community of writers that was described as feeling both welcoming and highly insular. In those days, based on the focus of the Writing Center as fomenting a writing culture, the main focus, necessarily, was trust and understanding among the people who worked together. This concept was buttressed by the space. The Writing Center, at the time, was located in an even smaller and more seventies-y room next door to its later location in the Library basement— a ten-by-ten (or less) space fit for, perhaps, two. Writers, creative and otherwise, came to see their Writing artfully critiqued, much in the way one of Dave’s classes works today. In line with Dave’s fluid and beautiful poetry (“You have to follow the golden thread…. And only follow it. If you tug too hard, it will break,” are some favorite Staffordite words of advice) and the style in which he teaches, the center, above all else, valued its writing community and developing voice.(9)

Composition Theory was fresh off of the “Tidy House” speech by David Bartholomae. Everyone was talking about Basic Writing, and everyone was coming up with radical solutions to its problems(10). Even though radical, solutions to these problems tended to come in three varieties: Additional coursework, curriculum systems that created additional courses as a prerequisite to the mainstream course within the for-credit University catalog in an attempt to acclimate students to the University Discourse without removing them from mainstream coursework entirely; Stretch Courses, which stretched the same course taken by mainstreamed students over two semesters(11) so students whose home Discourse differed more from the University’s, or who had some learning difficulty, could have more time to acclimate; and Spatial curriculum choices, which allow students to schedule additional time to work on their writing during the same semester, with the understanding that this instruction would happen in a different space and time than the Composition Course. A very famous Spatial-style course arrangement is that of Grego and Thompson from the University of South Carolina, which arranges the composition classroom as a three-tiered system composed of the course, the Lab where individual instruction with an outside instructor happens, and then the workshop, where the Lab Instructors and Composition Professor work together, while all the students who take part in the course work on writing.

It was a variety of this Spatial design that Gay Lynn implemented when she arrived at Marian University in the mid-90’s, shortly after the publication of “Tidy House.” But there’s something interesting about that implementation— despite the timing and the similarity, neither “Tidy House” nor the program at University of South Carolina had any causal connection with the design of our Lab Hour/ENG 101 connection. As Gay Lynn informed Mark and I sometime last year, the design of the program was borrowed wholesale from the one she’d come from at Florida State University.

What was even more shocking was, when Gay Lynn and I asked the current director of the Writing Program there, Dr. Debra Coxwell-Teague, it turns out that the program was in place until just shortly after Gay Lynn left Florida State— and had been in place since 1986.

This was a brain-melter. This meant that despite every Composition textbook I’d read telling me that the turn in Basic Writing was spawned by a white man who loomed large in Composition Theory— David Bartholomae, whose mere bickering with Peter Elbow dominated the 90’s Composition Theory discourse— there was an entire curriculum designed by a female high school teacher of unknown moniker acting as interim Writing Program Director, which presciently modeled the style of classrooms Bartholomae would advocate a full six years later in ’92.

“That is often the case, you’ll find, when you start to dig deeper,” Gay Lynn told me when I expressed my amazement. She leaned across her desk, the way that someone does when they’re about to delve into something they truly love to talk about. “Theory often trails behind practice. The people are in the trenches working with a mess of already-existing theories and pedagogies and doing what it is they do and making changes on-the-fly as-needed in-the-moment, and just concerned with doing right by their program and their students. Then someone comes along and writes it down or says it to a crowd, and… Bazinga.”

Agency, advocacy, ownership. Bazinga.

“Humanities has a paper coming up,” chimes in Lydia. Her eyes look up from her computer to the faces around her— the faces of Gabbie, Alyee, KC— then me on her left, and Mark on her right. We’re all tending that liminal space between thought and expectation, an extended moment of courtesy between turn-taking in conversation. Lydia, filling the space, chimes back in again with a question?

“We could make it a humanities workshop?”

“Hey, Lydia.” Mark leaned back in his tall blue chair, his smile creeping up through the beard. That smile that makes everyone nearby expectant of something teasing, something cutting, something simple and sense-making…. they tend to emerge in equal measure, and with no real-seeming pattern guiding their exit path, so we all sit like bat-catchers at the entrance to a cave waiting to sweep our nets in any direction.

“How would you like to be in charge of a Humanities workshop on that Friday?”

Pause.

“I mean… what would it look like?” she asked, already penning her to-do-list on her personal Trello Board and grinning ear-to-ear. The grin, in this case, isn’t a descriptor of emotion, but rather a descriptor of Lydia as a whole— the grin that permeates into her voice, demeanor, and substance.

“Okay… well, what do we need to do? They have a paper coming up, but not for a little while, right?” Mark, the other tutors and I all nod. “Maybe they could do some brainstorming, or talk about how to write a good humanities paper.”

On March 4th, Lydia will attend(12) her first ever Writing Center Conference at ECWCA. She’ll get to watch Mark, KC, and Gabbie give presentations that will be well ahead of what many other writing centers are even contemplating right now: Service Learning? Professional Writing? Many writing centers are still wondering how to get off the ground and get students to visit, let alone how to prioritize their tutoring sessions. But a history of Directors and students, working hard to innovate and inculcate a high degree of scholarship, has provided Marian with the intellectual and functional capital to have these conversations. So, while some Writing Centers are still wondering if composition theory and education theory has a place in the Writing Center at all, Mark, on the other hand, will be working in a very specific niche the world of composition and education theory, talking about legitimizing systemically delegitimized funds of knowledge(13) through the Writing Center— bringing into the Writing Center conversation education, sociological and composition topics that have, in some cases, not been offered in our discipline before.(14)

Before we wrap up, I want to add a disclaimer. That our Writing Center is currently at some zenith of its development and at the end of some ray of progress would be misleading. Much like the baklava of our words and academia itself, the ground beneath us and the world around us are constantly in flux. We don’t know, after all, what things we’re doing now, though evidence-based and thoroughly researched, will be looked on as problematic as new and compelling evidence is produced through the years. But the developments in the center over the past couple decades are not trivial, they are not abrupt, and they’re not random. There are scores of studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of our tutoring methods(15) as they’ve developed with emerging scholarship, and our Writing Center has positioned itself to contribute to that shifting academic landscape. But it’s when we begin speaking within the University of these systemically delegitimized funds of knowledge that we encounter something quite profound— and, I think, the thing that makes our Writing Center today and the Writing Futures program that it exists within fundamentally different not only from other Writing Centers, but from the very milieu in which the center and the Writing Futures program operates— because not everything around us is a paragon of collaborative knowledge-building.

For today, we’ll skip the fifty years of theoretical in-fighting and the misappropriation of “Copernican shift” moments that have been one of our themes. Perhaps that is a story for another time. But for now, the present-day Writing Center exists on a knife’s-edge of disciplinary and interdisciplinary theory, and at a crossroads of multidisciplinary frameworks within the institution. And the recognition of those frameworks is important, because of the narrative those frameworks will write on the students who inhabit them, consciously or tacitly. In the Writing Center, everything we do is an attempt to create a space where students’ developing agency can flourish, advocate on behalf of and allow space for the self-advocacy and critical advocacy in students, and create shared ownership of spaces, concepts, Discourses, and power in a way that engages rigorous scholarship. But look around you and you’ll see the signs: Where the framework is closest to the Garrett or Storehouse model or something closer to an egalitarian, collaborative model reigns. Where particular knowledge is privileged and other knowledge denigrated, or all knowledge is recognized as a collection of neurons firing that mitigate life experiences which, when stripped from power structures, becomes “right” based only on the applicability of its current use. And where the Instructors are the sole granters of knowledge and students vessels for filling, or students are actors within a whole new world, creators of knowledge regardless of where they’ve been or where their newly-created knowledge will take them, and craft their own place in the narrative that we, the “theorists,” will inevitably get to tell.

But of course, if you attend a conference, you can tell your own story.

--A.W.

Endnotes

1 The current Writing Center Director

2 A rather famous poet, essayist, literary critic, and translator of Eastern poetry and aficionado of Carl Jung’s work

3 Jungian Analytical Psychologist of great repute from the early 20th century

4 The Writing Center Director.

5 The previous Writing Center location

6 The current Writing Center location. The Writing Center moved over in the Spring of 2010.

7 This was of course taken along with the merit of the work over the course of the internship, and as far as grades were concerned merit of the work was more important— a solid internship that didn’t pan out with a high net result of student contact wasn’t automatically penned a failure. But the programmatic focus was increasing outreach onto campus, and so the measurement for that was net increase in tutorials resulting from the internship.

8A couple years earlier, Mark and I had worked as Lab Hour Instructors simultaneously, but never ran into each other— and a couple years before that, Mark and I (Mark as an instructor from ____ and I as a student leader acting in a role as emergency pseudo-teacher) had both taught middle school students during the first annual and only-ever Summer Writing Program at Marian University. I cut a fly in half in mid-air protecting the strawberries he’d brought us from his home garden, and have never again been able to replicate that feat despite hundreds of tries.

9 Voice is a very well-known, and also foggy term within composition theory. It’s one of those things that is undeniable when it’s seen, and when it’s not there it’s difficult to describe and even more difficult to foment. One of the aspects that Shumate often uses, is recognizing “self,” in writing. This focus on voice has continued through to today, and its influence was integral in the focus on agency and ownership, and subsequent addition of advocacy, within the Writing Program.

10 The main problem with “Basic Writing” classes, typically classified as 099 classes, is that they were very often unintentionally (or intentionally, depending on your level of cynicism) exploitative of poor and minority students. As Bartholomae pointed out in “Inventing the University,” and many linguists such as James Paul Gee have pointed out time and time again, it is unreasonable to expect a college freshman to come into school and immediately write like someone who understands, or worse yet has mastered, collegiate writing. This particularly effects poor and minority students, who often come from backgrounds where linguistic norms and cultural valuations differ most greatly from the University, which, in turn, tends to result in poorer testing scores. Now, if these courses were merely to help student acclimate to college environments that would be one thing, but as they had been traditionally conceived, they were non-credit-bearing courses (meaning students still had to pay for them, but they were not actually admitted into the University and/or didn’t count for college credit), they were remedial (meaning they were stigmatized as students who weren’t quite as bright as mainstreamed students, who on trend were typically whiter and more affluent), and because of this combination often ended up being a $3000 bill for a student who then left the University without any credits or benefits from having taken the course.

11 IUPUI’s ENG W130 offers a “Stretch” variety of course. Students stay with the same instructor over both semesters, and go through the same material just in twice the time, giving them more time to acclimate to the collegiate Discourse.

12 At the time of this writing, future tense was still appropriate

13 Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., Amanti, C. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. 2006. Routledge.

14 This is a very academic-ey way to say that Mark wants to value the learning that happens every day outside of formal schooling as much as that which happens within formal schooling. This theoretical framework says that everyone, everywhere, has a huge storehouse of knowledge available to them simply by being a person existing in society, and that it is only social structures that privilege certain types of knowledge rather than the inevitable stratification of knowledge in and of itself.

15 Lightbrown, P.M. (1983). Exploring relationships between developmental and instructional sequences in L2 acquisition.

Krashen, Stephen D. (1987) Principles and practice in second language acquisition.

Brown, H. Douglas (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching.

All related to the “highlighter method” borrowed from ESL/ELL instruction techniques

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Naming of Things

This will be the third version of the blog post I said I would submit for the week of April 4-8. Perhaps there are ways to interpret April 10 as a day within this range. More likely: I’ve not met my obligation. This is not for lack of trying. The first draft produced a few pages on my East Central Writing Center Association Conference presentation. Too egocentric. The second draft gravitated toward narration of my teaching origins, inspired by a question Jill Crane asked while sitting down for a meal at ECWCA. Eh, too maudlin.

So here’s the third draft. We’ll see what happens.

Lately, there’s been a bit of conversation surrounding the role of writing centers, about what it is we’re supposed to be doing and how we should go about doing it. Actually, strike that. What I mean is that I’ve been attempting to generate and engage in some conversation about the role of writing centers, about what it is we’re supposed to be doing, and how we’re going to go about doing it. This question has been on my mind for some time, but I’ve addressed it with palatable urgency since becoming director of Marian University’s center in Fall ’15.

And it could be that this question is largely rhetorical, although if so, it’s been an effective tool as my recent conference presentations were all generated in response to it. I’ve found myself thinking more about this question lately, thinking it possible I’m close to an answer. Which is to say: I think maybe I’ve known the answer all along, but I’ve been biding my time in the off chance continued percolation will enhance my understanding and prevent me from saying something too simplistic.

But first: I was driving to Marian this afternoon, a Sunday, to attend the student achievement awards ceremony when the answer to this question finally hit me. Earlier in the week, Lydia, who normally tutors early Sunday afternoon, had requested off because she was to receive an award today. In the resulting conversation, it became apparent no one was available to take her shift because a significant number of tutors were also receiving awards, and KC was involved in the Out of the Darkness Walk (along with Rachel Carroll, also walking). We needed to delay our regular opening time this Sunday because of the number of tutors who were either being recognized for their academic and community achievements or who were actively pursuing their commitment to shape the world into a more just place.

That brings me to this:

writing centers are in the business of making the world a better place. As cliched as that may sound, it remains true.

Our work is to serve others, our community, and ourselves through language, one word and sentence and paragraph and document at a time. By doing that, we demystify the approaches to challenges, the abstract becomes concrete, and the naming of a thing becomes the first step in making it real. Words matter. Literacy matters. And we prove it every day by sitting and learning and collaborating with everyone who walks through our door or sits down next to us.

Writing centers provide a space to listen and question, to investigate thinking and to challenge our own literate processes by

being brave enough to have conversations that matter

and demonstrating what it means to ask questions. Sometimes easy questions, but often difficult ones too. About ourselves. About others. About the supposed nature of things. When centers facilitate this type of interaction, everyone involved in the process is encouraged to think critically and— more importantly— to act upon critical thought.

How will we know if we achieve this level of engagement? There are probably a few ways to assess this, but I feel like we’re on the right path when we are forced to remain closed when no one can work because so many peer tutors are receiving academic achievement and service awards. I feel like we’re heading in the right direction when our tutors present at national and regional conferences and influence broader conversations about the role writing centers should have on campuses and in communities. When tutors engage in original research, labor alongside Indianapolis community members, draft multiple novels, and write publicly with brutal honesty about personal struggles… well, it’s hard to not feel genuine hope the world will at least be an okayish place.

Yes, this post sounds largely self-serving.

Our tutors are the best!

But in thinking about the essential purpose of a writing center, I keep coming back to the idea that a center should be space for the collaborative investigation of self and community. How we investigate is through writing, language and literacy. But it is essential that we investigate. This should also be true for those who work within the center and collaborate with others. If we’re actually doing what we say we’re doing, our peer tutors will establish themselves as scholars, as intellectual and social advocates who are not content with the current order of things because they have practiced the act of questioning them. If our center is doing what we’ve set out to do, these tutors— and everyone with whom they work— will know they are capable and responsible for charting their own path forward. They will know the world is eager for them to name the things they will alter and maintain, curate and create.

As of today, I’m feeling confident and proud that we’re getting there.

-M.L.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

April is National Poetry Month!

One of our writing center whiteboards is devoted to our weekly poetry challenge--take three unconnected words and create a poem out of them! Here, the words were “bequeath,” “explode,” and “charity.” Though we have no windows in our writing center, a tutor has also provided us with an artistic rendering of a window. A beautiful day, despite the mysterious UFO, while we deal with rain and hail here in Indianapolis!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Beyond the Book

Our Writing Center tutors go through a lot of training, from conferences and presentations to active fieldwork. Our trainings are long and frequent. We like to be prepared for anything. Got a paper requiring Chicago Style? We’ve got a tutor for that. Not sure when to use ‘that’ vs. ‘which’? Take a look at the handout we’ve created.

But I’ll let you in on a little secret:

Sometimes we don’t know what to do. At least by book standards.

As a senior tutor, the times that I don’t know what to do have become less and less each year. I’ve developed a sense of what most teachers expect out of their students, something that has only come from four years of working at our Writing Center. Though I am no expert on every style of citing, I can confidently answer most questions without a second thought. So when something throws me off and leaves me dumbstruck, I take notice.

Two weeks ago I had my first experience at a community library as a Marian University tutor. I didn’t know what to expect and hid my slight twinge of nervousness beneath a cheerful smile. “There probably won’t be anyone there for the first two weeks,” my boss assured me. As I walked into the dimly lit room and set up our shiny new sign, I realized he was wrong: we already had two people waiting for us.

The other tutor, KJ, took the first client and immediately started up a rapport while I waited for my client to approach the table. This client, we’ll call him Jalean, was nervous- his hands were shaking before he even sat down. He slowly pulled out a faux black leather binder and carefully laid out his papers and pen. “What can I help you with today?” I asked. “Well, I, um… I’m a preacher but I just really struggle with connecting my words,” he said, looking at me hopefully.

Me too, actually, in that moment. What did he mean? “Do you struggle with getting the words on paper or with other grammatical issues?” I probed. “My papers, they just don’t have the connection that I want the audience to experience. I don’t know,” he mumbled and added, “I’m a preacher.”

I’ve had a lot of tutorials with students that need support getting started, but I wouldn’t say it is my strongest point. Everything that I’ve learned about the process has come from observing Aaron Wilder. He is approachable, yet challenging: in essence, he doesn’t let “I don’t know” suffice as an answer. In that moment, I decided to channel my inner Aaron.

“Let’s try a stream of consciousness exercise,” I begin, “It basically means that you write whatever you want for a few minutes, without thinking about possible grammatical mistakes. It’s a practice to help get past the initial block you might be feeling.” Noticing his eyes had gone from nervous to slightly petrified, I added, “To make it easier, why don’t you write about your day?” He nodded and with my signal, began.

I watched him struggle to get words on paper. While it’s easy to tell students or community members to write whatever they want without fear of correction, it takes a lot of mental effort to overcome perfectionism. By the end of three minutes Jalean had about three lines. “I didn’t get much,” he said, disappointment resounding in his voice.

I paused. This wasn’t how stream of consciousness was supposed to go. The paper was supposed to be filled with messy writing, not neat sentences. Clients were supposed to feel inspired, motivated, and free. What could I do differently?

At that moment I caught a very faint whiff of my vanilla perfume. Perhaps what this client needed went beyond mimicking what I’d seen. Perhaps this client needed a sensory experience.

“Now this time,” I said, looking him in the eye, “I want you to choose a sense and describe the same day, using that sense to add details to the story.”

“Like smell?” He asked. “Exactly,” I nodded, smiling, “like smell.”

This time I watched him write fast and smooth, barely stopping to lift his pen to dot and cross. Every few lines or so a smile would emerge. All too soon, his time was up.

“I wrote about the birds I heard this morning,” he shared, before I even had the chance to get a word in, “and how their songs remind me of how blessed I am.” His hands rose and fell as he animatedly explained, “Doing this exercise was like lighting a fire in my soul! It was exactly what I needed! Thank you, thank you!”

We continued our tutorial for the duration of an hour, discussing additional resources he could use to improve his writing, but I kept returning to the moment of realization when I first saw his eyes sparkle with confidence.

Where our trainings end our intuition must begin. This isn’t a blind intuition but one that comes through being intrinsically connected to all of humanity. Perhaps we are more than the box we have put ourselves in: perhaps in our courage we are breathing fire starters, helping souls find their own lights.

And that is something no book will ever teach us.

-Alyee

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Filling Pails and Lighting Fires Don’t Cut It

I discovered that I had a green thumb right around the time I discovered my passion for reading, analyzing, and discussing literature. Maybe it shouldn’t have taken me by surprise—my sister and I did craft a little garden plot behind the house when we were kids, planting the sunflower seeds we were given when we registered for kindergarten, and when I did start growing cucumbers and tomatoes of my own, I was delighted to discover that the plants looked quite like the pixelated produce I had cultivated in my favorite video games (Harvest Moon, anyone?). During my junior year, the same year that I began annotating and highlighting books with reckless abandon, I volunteered with the high school’s garden club—soon I found myself checking the greenhouse and watering seed starts after school, helping primary schoolers build their own garden beds, and planting peppers and radishes in my own backyard.

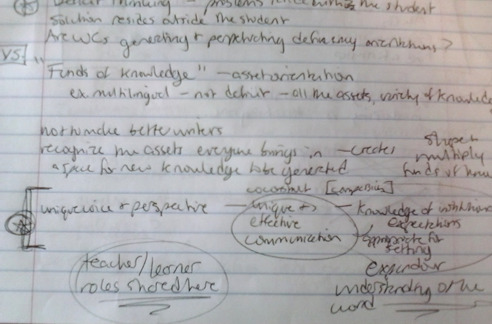

Perhaps, then, it shouldn’t be a surprise that gardens sprang to mind on the ride home from the East Central Writing Centers Association conference. I pulled out my notebook and began jotting down a sudden thought that captured the “funds of knowledge” approach to writing center work that our MU Writing Center Director, Mark Latta, had suggested in his presentation. He had shaken up the audience by declaring that writing centers should shake off their attachment to the slogan, “Our job is to make better writers, not better papers.” The slogan relies upon deficit thinking, which frames our interactions in the writing center as those of deficient, or flawed, writers coming to us to impart our knowledge and “make” them better writers. It was troubling that the audience defended the slogan by calling attention to the way higher education as a whole operates in this manner. Paul Freire captures this approach to education with the concept of a banking system, in which teachers have and impart knowledge to students who deposit it in their minds without learning to think critically about that knowledge or use it. What happened to education not being the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire? And, as I reflected on that quote turned adage, I had the scandalous realization that even lighting a fire requires a missing spark.

But, to return to the stunned audience in Session 4A of ECWCA 2016, there was so much friction over deficit thinking that the alternative, funds of knowledge, was never really discussed. As for myself, I had jotted down, on the heels of our director’s presentation, a quick chart attempting to capture something of it. On one side of the page, I wrote, “unique voice and perspective.” No one can write the paper which that particular student is going to write, even if everyone received the same prompt. On the other side of the page, I wrote, “knowledge of institutional expectations.” Tutors, as experienced academic writers, bring an understanding of how to effectively present information to different audiences. Drawing lines from each side, I scribbled “unique + effective communication” in the center of the page and circled it.

Though the presenter immediately following our director mentioned that she would push back a bit on the criticism of the slogan, when she asked audience members to recall a particularly rewarding tutoring experience, one of the tutors in the crowd said something that caught my attention. As she recalled her tutoring session, she mentioned how she told the writer, “You’re the teacher here; I’m the student!” Exactly! Beneath my rough chart of what student writers and tutors bring to the table, I wrote and circled “teacher/learner roles shared here.” During Q&A section of the session, I tried to express my thoughts in my notebook once again: we all have deficiencies, but we also all have assets, and that is what is interesting—how our assets combine, not how our assets address student writers’ deficiencies.

Okay—here’s the part where I warn you that there’s an extended metaphor on the horizon. After dessert that night, the keynote speaker discussed learning ecologies. This concept poses that a writer does not write something in a vacuum—there is an environment around them that affects the writer and their writing. The conversation that the writer hears on the street, the writer’s relationships with family, friends, or coworkers, the stories which people share with the writer all, in part, contribute to the writing. The keynote speaker even brought up a textbook image of an ecosystem.

Let’s run with that. Let’s imagine all of us writers, tutors and students, as gardeners in a big community plot, and let’s think of all of our projects as our garden beds and plants. Tutors have a green thumb, and we’re veterans of a few more seasons than many of the students who come to see us. We know a little something about how to make plants grow well in our regions—our academic disciplines. We can offer advice on amounts of water and sun, on spacing between seeds, on what plants grow best together—what kind of language and citation to use, how to organize a paper for a stronger impact. If a gardener is struggling with a plant, we can recommend fertilizers—to spur a student’s thinking, we might ask them to think out loud, to dig deeper into their sources, to shed a little more light on an undeveloped idea. We do not pretend to hold all of the answers—we do not deposit gardening kits into the hands of new gardeners, as students in Freire’s banking system are handed knowledge to deposit in their minds unquestioned. In that case, we would see them struggling over their failing crops with limited directions, trying to make the plants adjust to the system rather than questioning the system. Sometimes, the gardeners who come to us might know more about their specific plants than we do—maybe we are unfamiliar with the discipline’s expectations for this kind of paper, maybe we are totally unfamiliar with the course material, but the student can teach us something as we provide our own insights. This collaboration, this hybridization, makes our gardens and our plants more flavorful, more colorful, and more resilient.

What our student gardeners have in their garden is unique to them, based on where they came from, their traditions, and their personal preference. My garden, with plenty of hot peppers and cucumbers for pickling, might look very different from another’s, with plenty of tomatoes, with experimental varieties, with herbs and spices from another part of the world that I have never visited. Our director mentioned that deficit thinking could even be colonial—we don’t want to see our class discussions, our essays, and our educations become like a crop monoculture. Mass produced thoughts that are accepted without discussion or question, much like mass produced crops that are picked and packaged before they are truly mature, make for a bland intellectual environment. As in nature, in the writing center and in our academic pursuits, we are stronger for diverse diets. Our community garden flourishes when we realize that we are better for all of the different experiences and insights, all of the funds of knowledge, we each bring to it. We are all growing, cultivating our gardens with a little help from our friends.

--C.C.

*I would also like to thank K.C. for her recommended reading on the “banking system” in education and for sharing even more insightful ways to compare tutoring with gardening!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Last week’s whiteboard question:

“Which famous author would you like to share a massive, messy plate of nachos with?”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Big RAD Wolf: Quantitative Research in the Writing Center

Over the course of ECWCA I learned that there's a new focus on pursuing RAD research in the writing center--using replicable, aggregable, and data-supported research to come to conclusions about writing center practices. I found myself beginning to wonder why this wasn’t already so. How much of what we do in the writing center is based on talk--on ideas, models, and theories that have the outward appearance of sound logic, despite having never been put to the test?

As I moved from session to session at the conference, I listened to presenters end their inquiries where I would just be starting mine. Changes and improvements to writing center procedures were discussed with the kind of confidence I would only feel with a p value of less than .05, and were just as swiftly left to the audience, for us to take or leave as we wished, when all I wanted to know was what worked and what didn’t.

When presenters did turn their questions into research (instead of a concluding slide on their Powerpoints), it was generally in the form of qualitative comparison and analysis. And don’t get me wrong: I understand the desire to remain qualitative. After all, we support and validate personal experience every day in the writings of our clients. Surely our own experiences with tutoring techniques have just as much worth in the academic sphere, do they not?

Perhaps they do, but interviews and recorded sessions are not the most replicable, aggregable, or data-rich sources of information. My intent is not to argue against qualitative research, however, but rather to ask why we are not embracing RAD research; what is so wrong with quantitative data? Are we afraid that t-tests and univariate ANOVAs will huff and puff and blow down our houses of student testimonials and in-depth analyses of tutorial dialogue?

I realize it may be the numbers. But as a psychology major with a fondness for statistics, I can assure you that numbers aren't always cold, hard, impersonal measurements. To me, quantitative data is a rating of how comfortable a student felt during their tutorial; it's the number of times the student and tutor shared a laugh; it's how many more people came in to get a paper looked at when they knew there would be free cookies and coffee. It’s a way to check whether the way we feel about what’s happening in the writing center is an accurate representation of what’s actually happening. And I’d rather make sure that our house is built of sturdy enough materials that the big RAD wolf can’t blow it down, than keep rethatching the roof and hoping it doesn’t fall down on its own.

- J. C.

(Don't worry--it's just the likelihood that two or more groups aren't different from each other, even though our data suggests there's a difference.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

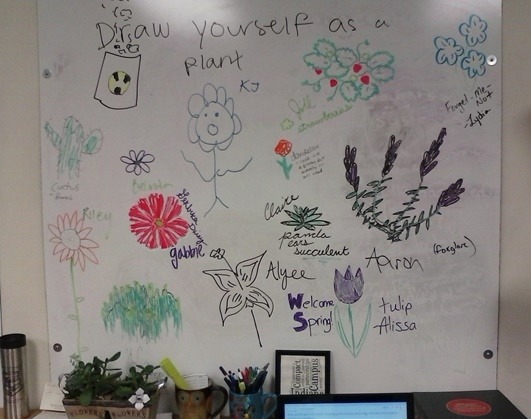

The fountain is flowing once again, the days are getting longer, the trees are budding, the weather is slowly getting warmer... With the first official day of spring right around the corner, MU Writing Center tutors and lab hour instructors have drawn themselves as plants! What kind of plant would you be?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who’s the Hero?

A Reflection on Social Justice in Writing Centers

By Gabbie Fales

There are many components to every story, but two in particular stand out above the rest in my mind: a conflict and a hero. Without conflict, there is no story. Without a hero, there is no resolution. With a shift toward social justice in writing centers becoming increasingly prevalent, it is important to take a closer look at where the conflict lies and who the hero is in the stories that we produce every day. At ECWCA 2016, the most fruitful and engaging sessions in my opinion were two that centered around social justice (and incidentally two of our own presented at these sessions...but no bias, I promise).

One session began with our fearless and strongly bearded leader Mark Latta. The title of his presentation was "Can't Fix Anyone: Our Historical Love Affair with Deficit Thinking"...bold title, I know. Mark was honestly pretty bad ass. There's this saying in writing centers that "we make better writers, not better papers." Which sounds great, right? Well, actually Mark tried to turn this concept on its head. And I'm not sure that everyone bought into it, but I sure did. The problem with this phrase (that has become 'almost holy' and a slogan of virtually every writing center) is that it implies two things:

that it is our job/right/duty and

that there is something wrong with the student writer.

To break it down simply, if we say that we have the ability to make someone a better writer, we are implying that they are flawed in the first place. While everyone can always improve their writing, to think of the students we work with as needing our help to improve is kind of a self-righteous way of thinking of ourselves- and thinking of the student not as a writer, but as a flawed writer.

Now you might say, okay I kind of see that and most of the people in the discussion afterwards did say that to an extent. Some questioned Mark's offered solution (a change from deficit thinking to funds of knowledge) and challenged his resistance to this revered phrase. But somehow Thing 1 (that it is "our job" to "make" better writers) got totally brushed over. People could buy into the idea that our mindset toward the student and their writing abilities should change, but not a single person mentioned the verbiage of 'our job' and 'make'.

I am ashamed to admit that I was thinking these things in my head but did not raise the question out loud- and looking back I wish I had. But to me it seemed obvious! Yes, treating the student as if they are flawed is totally a problem, but so is thinking that it is our job to make better writers. I couldn't quite put my finger on why this felt so wrong to me. My Communication major/Rhetorical Critic mind felt the word colonial lurking around that phrase. It seems to promote the idea that we are above the students, no longer peer, but a source of power. I felt that this topic was important, but I didn't have the words to continue the conversation myself yet- I needed time to process.

The next day, I attended KC Chan's session, "Serving the Community, Serving Us." KC spoke beautifully (seriously beautifully) about the importance of writing centers engaging with the community beyond the campus. When working with a group of women in the Indianapolis community, KC told one of the women who said she could not write that "We are all storytellers." Like...whoa. Such a simple statement, but so true and powerful. THIS was what Mark was getting at that I couldn't quite put words to. We are all storytellers; students, tutors, and community members alike.

Now after hearing these two presentations that seriously kicked butt, I was feeling super excited! I felt like our Writing Center had truly hit upon something so important. But in the 2 weeks that have passed since the conference, I've decided the conversation needs to be taken a step further. Yes, we need to revisit the way we view students and their writing, yes, we need to be active in the community...but what is it that ties these two ideas together?

As a communication major, I have taken many classes on rhetorical theory and criticism. It wasn’t until taking a class called Identity and Pop Culture, however, that I realized what the point of everything I had been studying was. In Rhetoric in Popular Culture by Barry Brummett, he writes “...critical studies is explicitly concerned with intervening, or getting involved in problems in order to change the world for the better.” The first thing I thought after hearing this was simply social justice. That’s what it all came down to. The purpose of studying culture, identity, power structures, and colonialism isn’t just to write a paper. The purpose is to make a difference.

After this “ah-ha!” moment of mine, I realized that there needed to be more to it than just a realization. If the papers I had been writing for two and a half years in my Com classes could really make a difference, couldn’t all of my other writing? And if all of my writing could be powerful, doesn’t that mean other people’s writing can be just as powerful?

Writing is in and of itself an act of justice.

This mindset of writing being powerful and capable of social justice is a mindset that needs to be carried over into writing centers and tutoring practices. Over the past year, I have heard many presentations advocating for social justice in writing centers...but the agents of social justice were the tutors. However, as I think Mark was getting at in his presentation, our goal as tutors should be to encourage and empower students to take ownership of their writing and advocate for their beliefs. The student should be an agent for social justice, too. The writing center is not just a place where writing is improved, it should also be a grounds for using literacy to make a difference, whether that difference be personal, communal, societal, or global.

Every piece of writing seen in the Writing Center is a story in the sense that it should have a conflict and a hero. Now these components may be difficult to determine in some types of writing, but they are there in one way or another. Like any good story, the Writing Center has a conflict and a hero. In a tutorial, the conflict will vary based on the student's needs. Maybe their thesis isn't quite working with the rest of the paper, or maybe the student doesn't know how to cite in APA. There's the conflict- but no flaw.

But who's the hero?

We are. They are. Writers are. Like KC said we are all storytellers, we are also all heroes.

'Our job' as tutors isn't to make a better writer or a better paper. We are there as a peer, a fellow storyteller, to help the student take ownership of being a hero.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No One Remembers Easy.

“We’re superheroes.”

Grey’s Anatomy’s Amelia Shepherd says to Stephanie Edwards. Shepherd stands with her hands planted firmly on her adult diaper in the ever-familiar “superwoman” pose as she prepares for a 20+ hour, impossible, never before dreamt of surgery on a world famous fetal surgeon’s massive butterfly tumor.

Edwards’ response?

To join her, of course.

And when Shepherd, who is the one and only neurosurgeon with any dream of holding a scalpel to this masterpiece tumor, asks Edwards, her protégée, who will be subbing in for after 12 hours of standing in one spot, Edwards responds with the same endearment.

“We are superheroes.”

It is amazing that, only in retrospect, I am remembering this moment. Because for 3 days I had been telling Gabbie that we needed to do this pose, this X-Formation before our presentations and had received a few looks of confusion.