Text

Some news...

Hi dear followers of this tumblr! I’ve decided to start a website where I will share my essays from now on! https://lothelynx.wordpress.com/ So feel free to check that out!

I also just published a new essay on there, about the “grotesquerie” that Tyrion and Penny ends up in during their enslavement in ADWD. https://lothelynx.wordpress.com/2020/08/29/the-grotesqueries-of-planatos/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colonialism in His Dark Materials

CW: racism, sexism, sexual violence

Spoiler warning: all the books in the His Dark Materials series, as well as La Belle Sauvage, The Secret Commonwealth, and Once upon a Time in the North

Intro

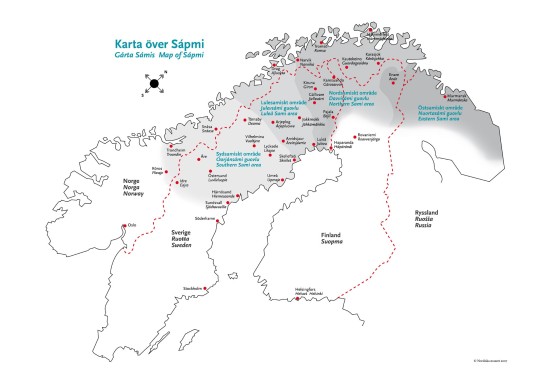

His Dark Materials takes place in a world like our own, but not quite like our own, which is evident in everything from daemons to their use of anbaric light instead of electric light. It’s also evident in the way national borders have evolved in their world, as is clear if one looks at the map of Lyra’s world:

(Source: His Dark Materials Wiki)

It should be noted that while this map is to my understanding an official in-world map, it doesn’t seem to include every country, for instance there is no mention of Norroway which is mentioned in Northern Lights (Pullman 2011a, 170). I spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out how the North in this world functions and compares to our world in this essay, and the parallels one can see to the history of our North. Furthermore, a while back the excellent podcast Girls Gone Canon pointed out that in The Subtle Knife Lee Scoresby meets someone who he describes as a Yoruba man (2020a). This is interesting, since in our world, the Yoruba people are split across several different nations (mainly Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana) as a result of colonial borders. As Girls Gone Canon said, this makes one curious about the colonial history of Lyra’s world, was there a British (and French, Spanish, Dutch etc) empire in the same way as in our world? It’s clear that racism and xenophobia exists in Lyra’s world, for instance there are several instances of disparaging remarks about the Gyptians, Turks, and the Tartars. The Tartars are described as dangerous and brutal throughout Northern Lights, for instance in regard to their practice of scalping and trepanning enemies (Pullman 2020a, 26). We later of course find out that they don’t trepan their enemies, but that it’s a ritual reserved for those the Tartars esteem (ibid, 228). We also hear of Turk children kidnapping children (ibid, 105), and as I will expand upon further later, the gyptians are often looked down upon by landlopers (non-Gyptians). For instance there’s this quote from La Belle Sauvage, when Malcom tries to pass on Fader Coram’s warning about a flood coming to his teachers who think: “It was nonsense- it was superstition- the gyptians knew nothing, or they were up to something, or they were just not to be trusted.” (Pullman 2018, 277) But it’s also clear that while there is racism in Lyra’s world just as in our own, the history of Lyra’s world is different than ours, as can be seen in how the national borders have been constructed. So, one might assume that the systems of colonialism, and how coloniality still effects Lyra’s world is different as well. In this essay I will argue that the Magisterium plays a similar, if also different, role to the colonial powers of our world. I will specifically focus on three aspects of this; the gyptian’s situation and the Magisterium’s treatment of them, the Magisterium’s attempted control/colonialization of The North, and the Magisterium’s control/colonialization of Asia Minor.

So, what do I mean by saying colonialization and coloniality? Well, as feminist post-colonialism researcher Chandra Talpade Mohanty writes:

[T]he term ‘colonialization’ has come to denote a variety of phenomena in recent feminist and left writings in general. From its analytic value as a category of exploitative economic exchange in both traditional and contemporary Marxism (cf. particularly such contemporary scholars as Baran, Amin and Gunder-Frank) to its use by feminists of colour in the US, to describe the appropriation of their experiences and struggles by hegemonic white women’s movements, the term ‘colonization’ has been used to characterize everything from the most evident economic and political hierarchies to the production of a particular cultural discourse about what is called the ‘Third World’. However sophisticated or problematical its use as an explanatory construct, colonialization invariably implies a relation of structural domination, and a discursive or political suppression of the heterogeneity of the subject(s) in question. (1988, 61)

As she writes, the effects of colonialism can be seen on several different levels in society. When analysing coloniality in His Dark Materials, I’m attempting to move between a discursive level and material level. That is to say, I consider both the colonial/white supremacy discourse, and its material consequences (and the way the material aspects contributes to the discourse). Another aspect that I think is relevant to consider is how colonialism effects the way we move through different spaces, and indeed through the world at large. Feminist and critical race theorist Sara Ahmed describes it like this:

Colonialism makes the world ‘white’, which is of course a world ‘ready’ for certain kinds of bodies, as a world that puts certain objects within their reach. (…) I want to consider racism as an ongoing and unfinished history, which orientates bodies in specific directories, affecting how they ‘take up’ space. Such forms of orientation are crucial to how bodies inhabit space, and to the racialization of bodily as well as social space. (2006, 111)

A crucial point here is how racism and colonialism is an ongoing and unfinished history, and that it continually effects people, bodies, and spaces. Ahmed further describes that bodies who do not fit into this white world are deemed strangers and stopped in different ways. These bodies cannot move through the white world smoothly. As an example, she described how she, even though she has a British passport, are stopped at airports because her last name sounds Muslim. This makes her stand out in a white place, and as such she is stopped and questioned about her being in this space. This way of describing racial/ethnic others as, well, others, as strange strangers, is central in how a nation and national subjects are created (Ahmed 2004). We gain a sense of who we are, who our group is, and who “belongs” in our community and nation by making clear who doesn’t belong. As Ahmed writes about white supremacy groups: “Together we hate and this hate is what makes us together.” (2004, 26) Ahmed further writes about how such instances of racist hatred is both created by histories of racism, and creates the groundwork for future similar situations:

[A] white racist subject who encounters a racial other may experience an intensity of emotions (fear, hate, disgust, pain). That intensification involves moving away from the body of the other, or moving towards the body of the other in an act of violence, and then moving away. The ‘moment of contact’ is shaped by histories of contact, which allows the proximity of a racial other to be perceived as threatening, at the same time as they create new impressions. (Ahmed 2004, 31)

That is to say, racist encounters on the microlevel (between people) are influenced by historical structural racism and ensures that such structural racism can continue. Having established this background, I now want to move on to a group in His Dark Materials who are continually seen as strangers by the rest of society and mistreated for it; the gyptians.

The Gyptians

We first meet the gyptians in Northern Lights when Lyra mentions their children being part of the war the children of Oxford wage against each-other: “The other regular enemy was seasonal. The gyptian families, who lived on canal-boats, came and went with the spring and autumn fairs, and were always good for a fight.” (Pullman 2011a, 33) Later we are introduced to Ma Costa specifically in this manner:

It was about the time of the Horse Fair, and the canal basin was crowded with narrow boats and butty boats, with traders and travellers, and the wharves along the waterfront of Jericho were bright with gleaming harness and loud with the clop of hooves and the clamour of bargaining. (…)

‘Well what have you done with him, you half-arsed pillock?” It was a mighty voice, a woman’s voice, but a woman with lungs of brass and leather. Lyra looked around for her at once, because this was Ma Costa, who had clouted Lyra dizzy on two occasions but given her hot gingerbread on three, and whose family was noted for the grandeur and sumptuousness of their boat. They were princes among gyptians, and Lyra admired Ma Costa greatly (…) Lyra was frightened. No one worried about a child gone missing for a few hours, and certainly not a gyptian: in the tight-knit gyptian boat-world, all children were precious and extravagantly loved, and a mother knew that if a child was out of her sight, it wouldn’t be far from someone else’s who would protect it instinctively. But here was Ma Costa, queen among the gyptians, in terror for a missing child. (ibid, 55)

I want to highlight a few things here, firstly the way the gyptians’ tradition of moving around through the year (on their boats) and visiting during fairs (specifically horse fairs), secondly that the Costas are described as princes among gyptians, and thirdly that we are introduced to them with a child going missing. As I will argue here, the gyptians are quite clearly inspired by our world’s Roma people, and there exist a lot of racist stereotypes about Roma stealing children. Here instead, the gyptians’ children are the ones getting stolen. I will lay out further parallels, but before doing that, I want to note an interesting aspect of their name. In the English versions of His Dark Materials, the name for the gyptians seems to be a reference to the word g*psy (considered a slur by some Roma people, which is why have chosen to not use it). G*psy in itself comes from the belief that Roma people originally came from Egypt (Amnesty 2020). In the Swedish translation of Northern Lights, which is the one I read as a child, gyptians are translated to “zyjenare”. This is very similar to a Swedish word for Roma which is most definitely a slur, the His Dark Materials word has only swapped the i to a y and the g to a j. So, I’ve always thought it was very obvious that the gyptians were essentially Roma. I recently found out that in the Swedish version of La Belle Sauvage this translation has changed, and gyptian is translated to “gyptier” instead (which is a sort of Swedish-ification of the English word, it can be compared to the word for Egyptian which is “egyptier”). I do not know the reason for this but would guess that it’s because the original translation is uncomfortably close to a racial slur (they’re pronounced the same).

Moving on from name similarities, I want to look at how the gyptians’ lifestyle is described similarly to that of Roma people, and then look at the similar racism facing the two groups. Firstly, it bears mentioning that Roma people aren’t an ethnic homogenous people. Roma is usually used as a broad term to describe a variety of ethnic groups, including Romani, Sinti, and other Travellers. But as Colin Robert Clark points out in his PhD thesis ‘Invisible Lives’: The Gypsies and Travellers of Britain: “The reality is that for the last century and longer all Travellers, whatever their ethnic status, have been labelled as ‘criminals’, ‘deviants, ‘vagabonds’ and asocial.” (2001, 46). In the mind of the populace, all these groups are usually seen as the same. Therefore, I will refer to them as a group as Roma here, even if I’m aware that there are differences within that broad category. As Clark points out, among Roma in the UK there are a lot of similar traditions (2001, 125). Traditionally many will travel throughout the year, and do different seasonal work, while wintering in one place. Many meet up or gather at different fairs, including horse fairs. This, I think is similar to the gyptians in His Dark Materials. As pointed out in the quote I quoted above in Northern Lights, the gyptians tend to travel throughout the year, and turn up in Oxford for horse fairs. Another clear similarity is of course that Roma traditionally live and travel in caravans, while the gyptians of His Dark Materials travel on canal boats. As Clark points out, this is often central both in Roma’s cultural identity, and in the governmental oppression facing them:

[W]e need to recognise the fact that many Gypsies and Travellers in Western European countries, whether travelling or settled, are nomads. This is a 'state of mind' and their economic status and social identity are often defined and mapped-out by their nomadic life-style and culture, even when, out of choice or through policies of social inclusion and normalisation, they are permanently or temporarily sedentarised. For this reason, it is perhaps through their predisposition towards nomadism, rather than (or as well as) their ethnic identity, that they are perceived as a threat by states and governments. (2001, 55)

This seems similar to the nomadic gyptian lifestyle, which is occasionally threatened by authorities. Another clear similarity between Roma people and the gyptians seems to be the racist stereotypes surrounding them. A main one is of course the way Roma are seen as criminal and untrustworthy in different ways (Clark 2001, 72). As mentioned above, this stereotype seems to exist regarding the gytians as well, as Malcom recounts in La Belle Sauvage (Pullman 2018, 277). Another similar instance is that Malcom’s friend Erik claims that he’s been told by his father that gyptians always have a hidden agenda. Related to this, perhaps, is the way Roma are often connected to occultism, including fortune telling (Clark 2001, 70). This seems the case with the gyptians as well, which becomes especially clear in La Belle Sauvage and The Secret Commonwealth. In La Belle Sauvage, as mentioned, Fader Coram warns Malcom about the upcoming flood (which other characters dismisses as superstition), and in The Secret Commonwealth Lyra learns about different creatures from the secret commonwealth from Master Brabant (Pullman 2019, 224). Another stereotype about Roma people that seems to have been influenced Pullman when writing the gyptians is what Clark calls “internal nobility” (2001, 69). Clark quotes the following from Liegeois (1986: 58-63):

The 'King of the Gypsies' is a figment of the imagination of the gadze (non-Gypsies), and neither Roma as a whole nor any of the subgroups have a formal leader. ... These terms ... do not reflect a social hierarchy, but were an instance of superficial adaptation to local conditions and customs. (Liegois 1986, in Clark 2001, 69)

Clark goes on discuss how this might have been a way to interact with local nobility during historical times, and gain some sort of legitimacy in the eyes of the rest of society. He specifically brings up an example which I think is very relevant for His Dark Material, which is how an ‘Egyptian’ was granted certain powers by James V of Scotland:

which granted considerable privileges to John Faw, 'lord and erie of Litill Egipt' ... enjoining all those in authority in the kingdom to assist John Faw in executing justice upon his company, 'conforme to the lawis of Egipt' and in punishing all those who rebelled against him. (Fraser 1995, 118, in Clark 2001, 70).

Now, this seems like it quite obviously could be the inspiration for the gyptian character John Faa, lord of the western gyptians. It seems as if in the world of His Dark Materials the gyptians do have some sort of internal nobility, or at least ruling structure. It also seems relevant to point out how Lyra thinks that the Costa family are princes among the gyptians. Now, one stereotype that it seems less certain if it applies to the gyptians as well, is the stereotype that Roma are black and/or tawny (Clark 2001, 67). We very rarely get descriptions of the gyptians appearance in the books, what we do get is that Fader Coram is brown-skinned (Pullman 2018, 221), and that Lyra’s blond hair stands out (Pullman 2011a, 133). In either case, it doesn’t seem that such a stereotype exists, that judges the gyptians negatively based on their looks. Another stereotype that doesn’t exist in His Dark Materials is that of the Roma stealing children. Instead, as mentioned above, the gyptians children are the ones being stolen. That seems like it might be a deliberate contrast.

Now, let’s look at some similarities between how Roma people have been oppressed by governments, and how the gyptians are treated by the Magisterium. I first want to turn to a quote from an Amnesty report about the situation for Roma in Europe:

The Roma are one of Europe’s oldest and largest ethnic minorities, and also one of the most disadvantaged. Across the continent Romani people are routinely denied their rights to housing, health care, education and work, and many are subjected to forced eviction, racist assault and police ill-treatment. (…) Millions of Roma live in isolated slums, often without access to electricity or running water, putting them at risk of illness. But many cannot obtain the health care they need. Receiving inferior education in segregated schools, they are severely disadvantaged in the labour market. Unable to find jobs, they cannot afford better housing, buy medication, or pay the costs of their children’s schooling. And so the cycle continues. All this is not simply the inevitable consequence of poverty. It is the result of widespread, often systemic, human rights violations stemming from centuries of prejudice and discrimination that have kept the great majority of Roma on the margins of European society. (Amnesty 2020, 3)

Now, one aspect that I think is relevant to highlight here when considering similarities to the gyptians of His Dark Materials is that this situation is “not simply the inevitable consequence of poverty.” It is a result of systemic governmental discrimination and oppression. One part of this that I want to consider is housing. For instance, in the UK there have been many instances of the government prohibiting caravans being parked on lots of land for a variety of reasons (Clark 2001, 217). One example of this was The Caravan Sites (Control of Development) Act of 1960, which made it difficult for Roma to buy plots of land to winter on, since said act forbade land being used as a caravan site unless the owner of the land had a site licence. And to get a site licence one had to jump through several bureaucratical hoops that had the effect of it being hard for Roma to get such a license, and also made private landowners unwilling to let people stop on their lands, even if they had let them do that previously. In 1968 the Caravan Sites Act was enacted, which was supposed to provide more official sites for caravans where Roma and Travellers could stop, instead of having to stay on private land. This did not work very well in practice since very few such sites were actually created, leading to Roma and Travellers actually having fewer options on where to stop. This all sounds very similar to what the gyptians of His Dark Materials have had to face, as John Faa outlines when describing what Lord Asriel has done for the gyptians: “It were Lord Asriel who allowed gyptian boats free passage on the canals through his property. It were Lord Asriel who defeated the Watercourse Bill in Parliament, to our great and lasting benefit.” (Pullman 2020a, 136) We’re not told exactly what this Watercourse Bill entiled, but from context it sounds like it would limit the gyptian’s ability to travel and live on the water. That paired with them being grateful that Asriel let them pass through his property makes it sound like there might have been legal battles surrounding the gyptians travelling, similar to that of the Roma in our world. There is one big difference though, the gyptians have the Fens. The Fens seems to function as similar to a winter site might for Roma in our world, but for the whole gyptian community, where they also have some sort of autonomy. It is pointed out on several occasions that the Magisterium does not have jurisdiction there, for instance:

The gyptians ruled the Fens. No one dared enter, and while the gyptians kept the peace and traded fairly, the landlopers turned a blind eye to the incessant smuggling and occasional feuds. If a gyptian body floated ashore down the coast, or got snagged in a fish-net, well- it was only a gyptian. (Pullman 2011a, 113)

It also becomes clear here that the police in His Dark Materials do not care about gyptians, which is similarly often the case regarding Roma in our world (Amnesty 2020, 5). In His Dark Materials this also becomes evident when the police at first doesn’t care about the poor and/or gyptian children going missing; “Children from the slums were easy enough to entice away, but eventually people noticed, and the police were stirred into reluctant action.” (Pullman 2011a, 45). That brings me to the last form of government oppression that I want to mention, and that is the taking of children and control over reproduction. One instance of this in our world was the Norweigan Omstreifermisjonen, which roughly translates to “The Travellers mission”, a Christian organisation which with the backing of the Norweigan state practiced forced assimilation of Travellers during the 20th century Selling 2013, 26). This was practiced by forcibly putting children in boarding school like facilities and the adults in labour camps. Some argued for similar practices in Sweden at the turn of the century:

Vicar Hedvall in Malung shared the view that ‘[Swedish slur for Roma] and [Swedish slur for Travellers]’ generally raised their children to begging, promiscuity and crookedness. He argued for ‘reformatory schools’ for the children and labour camps for the adults, as well as changing the law so that the child welfare committee would ‘have the power to, without too extensive procedures, take the children into their care.’” (Selling 2013, 49). [my translation from Swedish]

We can see here that Roma and Travellers weren’t seen as suitable parents for children, who would in some instances be taken from them. Slightly later in history many Roma people would be forcibly sterilised for similar reasons (Selling 2013, 59). I’ve written about the Swedish history surrounding that in this and this essay, but it bears mentioning here too. As is of course the horrific genocide of Roma by the Nazis where approximately between 250 000 and 500 000 Roma was killed (Amnesty 2020). As I’ve argued previously, this history of eugenics feels similar to how gyptian children in His Dark Materials are kidnapped to clean them of Dust:

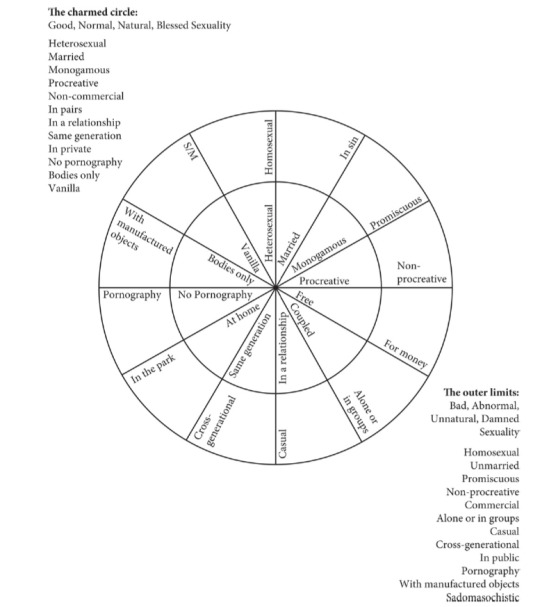

Another thing I want to highlight is the comparison between the severing of children and dæmons, and sterilisation. In the books, children’s bond to their dæmons (their soul) are severed by the GOB [General Oblation Board] in order to prevent “Dust” settling on the children (Pullman 2007, 275). Dust is considered dangerous and sinful, something that according to the church started infecting humans after their fall from the garden of Eden. Sterilisation in our world, on the other hand, took place in order to make the population “cleaner” and of “better” stock. Groups who were in different ways considered degenerate were targeted, including women who were perceived as promiscuous/sexual transgressors. In Lyra’s world a spiritual connection is severed by the Church in order to curb sinfulness. In our world a biological connection is severed by “scientists” (in collaboration with the Church at times) to control sexuality and reproduction. There is a definite similarity here. (Lo-Lynx 2019)

Among the people who were specifically targeted historically in our world were Roma, because they were considered degenerate (and thus shouldn’t be allowed to reproduce) and/or unfit as parents (and thus shouldn’t be allowed to raise children). The control of the lower classes and gyptians’ sexuality through the control of Dust feels very similar. It should of course be noted that this kind of practice did not just happen in the North in our world, sterilisations and other eugenic measures has taken place in many places. For instance, in countries that were colonised by European countries this was often the case, and here as well the church were often involved (Stoler 1997). Sexual control was in fact often central in creating and upholding racial boundaries in colonies.

We can thusly see that the way the gyptians are treated in His Dark Mateials is similar to the treatment of Roma in our world. I would furthermore argue that their status as “strangers” in the country where they live functions as a way to uphold racial bounderies and hierarchies, similar to how Ahmed writes (2004). By being thought of as suspicious and “up to something” they are continually othered and seen as lesser than society at large. Their treatment by the Magisterium is also similar to how Roma have been treated in many places in Europe, and a clear example of how nation of white hegemony/a colonial state might treat racial others inside of its borders.

The Magisterium’s controlling/colonizing of the North

I now want to turn to how the Magisterium in the books attempts to take control of the North, and how it can be seen as a colonial state’s attempt to do so. To do that I want to first give a brief historical background of a similar process of colonization in the North, but the North of our world, that is the Swedish colonization of Sápmi. Sápmi is the land inhabited by the Sami people, and it includes land in contemporary Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia. The colonization of Sápmi was highly tied up in the Christening of the Sami, who traditionally practiced their own religion. The website samer.se which is run by Sametinget, the governmental body of Swedish Sami, puts it like this:

In order to force the Sami to abandon their religion and instead attend church services and church education, the Church used different forms of punishment: fines, prison, or death penalties. The holy sites were defiled and drums [used in religious rituals] were burned.

During centuries the Sami religion had been able to live side by side with Christianity. But from the 17th century onward, the attempts to Christen the Sami went hand in hand with the Crown’s attempt to conquer the land in the north. When religion became a means of power, the Sami were made to suffer many forms of abuse, just as has been the case with other indigenous people throughout the world. (samer.se n.d. a) [my translation from Swedish]

One motivation for the Swedish Crown to claim Sápmi was access to natural resources there, such as silver and later iron (samer.se n.d. b). During the industrialisation of Sweden, even more parts of Sápmi became settled in order to open more mines, mainly iron mines. As I’ve written about in this essay, soon after this, new laws surrounding schooling of Sami children were put into place. This new law stated that teachers would wander around the mountainous regions in the summer. There, the youngest schoolchildren would be taught in the family’s cot for a few weeks each year during the first three school years. The rest of the school time consisted of winter courses in regular schools for three months a year for three years. The teaching would only cover a few subjects and it had to be at such a low level that the children were not “civilized”. Children of nomadic Sami were not allowed to attend public primary schools. It was often in collaboration with schools for Sami children where much eugenic “scientific research” later took place. As I wrote in my earlier essay:

In 1922 The State’s Race Biological institute (Statens rasbiologiska institut) was created in Uppsala in Sweden, by the “scientist” Herman Lundborg (Hagerman 2016, 961). He wished to research the Swedish race, and the mixing of races in Sweden. This was done in several ways, both by looking at records of marriages and birth (often supplied by church officials who had access to so called “church books” that recorded this), and physical examinations of people. He, and other “scientists”, travelled around Sweden to examine the Sami people and other groups that were considered inferior (such as Finns, Roma people, Jews, disabled people etc). The physical examination of Sami people often happened in collaboration with local churches or schools (Hagerman 2016, 984). Another part of the eugenics movement in Sweden that is worth mentioning here is the forced sterilisations that took place during this time. (Lo-lynx 2019)

Now, the reason I think it is relevant to consider the colonialization of Sápmi, as well as the eugenic practices toward marginalised groups, is the parallel it makes to what the Magisterium is up to in His Dark Materials. Consider for instance this quote from Martin Lanselius in Northern Lights:

‘Well, in this very town there is a branch of an organization called the Northern Progress Exploration Company, which pretends to be searching for minerals, but which is really controlled by something called the General Oblation Board of London. This organization, I happen to know, imports children. This is not generally known in the town; the Norroway government is not officially aware of it.’ (Pullman 2011a, 170)

There are some definite parallels here to the colonising of Sápmi, and colonising of other places too. A government/governmental agency comes looking for natural resources (or at least claiming to) and ends up doing medical experiments and take eugenic measures. I furthermore find it interesting that Lanselius in the above quote mentions that the Norroway government is not officially aware of what the GOB is doing, that indicates that the GOB (and the Magisterium as a whole?) is an outside influence taking control in this area of the North. I will return to the Magisterium’s taking control in other contexts later but wanted to note this here. We also learn that Marisa Coulter attempted to set up a similar facility as the one in Bolvangar on Svalbard, because there are less laws to consider there, as the bear Søren Eisarson relays:

‘There are human laws that prevent certain things that she was planning to do, but human laws don’t apply on Svalbard. She wanted to set up another station here like Bolvangar, only worse, and Iofur was going to allow her to do it, against all the custom of the bears; because humans have visited, or been imprisoned, but never lived and worked here. Little by little she was going to increase her power over Iofur Raknison, and his over us, until we were her creatures running back and forth at her bidding, and our only duty to guard the abomination she was going to create…’ (Pullman 2011a, 356)

This leads me to the next aspect I wanted to consider; Svalbard and the pansarbjørne.

In Northern Lights we first learn of a Svalbard ruled by the pansarbjørne Iofur Rakinson, who attempts to gain power by letting the Magisterium into Svalbard and conforming to human culture. This is very much a contrast to Iorek, the rightful king, who wants a return to true beardom. Now, of course, the pansarbjørne are bears, but they are talking bears with a culture of their own, and I would argue that they are often portrayed as similar to indigenous people. This is also something Girls Gone Canon (2002b) discusses in their episode on the novella Once Upon a Time in the North. One point that they make in that episode is that the whole of the Once Upon a Time in the North is very much written like a Western, even if it takes place in the cold north. Some aspects of this that they mention is that the protagonist, Lee, who is sort of the cowboy of the story, comes into this new town, and by the end has a shootout. There’s also clearly a resource war going on, and the bears play similar roles to that of Native Americans in traditional Westerns. In the episode, Girls Gone Canon also makes note of how the bears are described as “noble savages” by the character Oskar Sigurdsson, clearly a racist trope that exist in our world as well. Sigurdsson describes the bears like this:

‘Worthless vagrants. Bears these days are sadly fallen from what they were. Once they had a great culture, you know- brutal, of course, but noble in its own way. One admires the true savage, uncorrupted by softness and ease.’ (Pullman 2017, 12)

It is in the story unclear if the bears are confined to Svalbard before or after the events of this story. As Girls Gone Canon puts it, did the bears have a great kingdom that included Novy Odense and were later displaced by humans, or did they come from Svalbard but weren’t afforded rights in other places? In either case, it is clear that there are a lot of racial tension in the story, and that is exploited by the character Poliakov who tries to gain political power. He is apparently in league with the company Larsen Maganese who are supposedly looking for oil. This again reminds one of Westerns. I would argue that the “wild” North is in many ways similar to the “wild West”, since, as I outlined before, it has been seen as an unexplored land filled of resources to be claimed (samer.se n.d. b). The role the hunt for resources plays in the story is extremely relevant to the story, and to our own times. Girls Gone Canon put it like this:

A lot of this reminds me of private military companies in general, Iraq and Somali are decent examples of this, but maybe on a smaller scale, depending on some of our before speculation about the series and what exactly Poliakov is looking for, besides this local government power(…) the talk of oil is being loudly said, but Lee notices that there is no big trade happening. So, it kind of seems to be a cover for something, and, maybe he was mining for a resource, but it wasn’t just oil? I don’t know, but I know other governments who have hired armies as contractors who wouldn’t have to face local laws wherever they deployed those armies, you know? As a grey area. And because of that they committed atrocities. While they were saying they were doing it to stop terror instead. But they were really just like, you know, putting colonialism down real hard on the table and exploiting the place. (Girls Gone Canon 2020, 43:08 mins)

I’ll return to this notion of governments using terror as an excuse to go after resources later in this essay, but it is definitely clear that there’s colonial undertones in this claiming of resources and fearmongering about other races.

Before moving on from the Magisterium’s colonialism in the North, I want to discuss one specific character, namely Marisa Coulter. Coulter’s position in the world of His Dark Materials is interesting in many ways. As a woman in a patriarchal world, she has had to find alternative ways to power, because as Lord Asriel says:

‘You see, your mother’s always been ambitious for power. At first she tried to get it in the normal way, through marriage, but that didn’t work, as I think you’ve heard. So she had to turn to the Church. Naturally she couldn’t take the route a man could have taken- priesthood and so on- it had to be unorthodox; she had to set up her own order, her own channels of influence, and work through that. It was a good move to specialize in Dust. Everyone was frightened of it; no one knew what do to; the Magisterium was so relieved that they backed her with money and resources of all kinds.’ (Pullman 2011a, 372)

What this passage essentially says is that when Coulter couldn’t get power the way a man would, she decided to get it by making use of the very same oppressive system that tried to stop her. In many ways it reminds me of the way white European women would attempt to get power in colonies, where they (at least sometimes) could get more freedom/power. Feminist researcher Sara Mills for instance notes that British women in colonial India could find more freedom from restrictive social conventions than they did in their homeland (2003). One example of this that Mills mentions is how British women might find freedom in travelling and “exploring” colonies, and how some of these women in travel journals describe the way these women felt freer on their journeys than in their homes. As Mills rightly points out, this is of course a stark contrast to the life of many of the people they colonized whose freedom was restricted by colonialism. One cannot help but think of Marisa Coulter’s travels here, and how she found freedom by making use of an oppressive system. Her life also very much speaks to a point raised by bell hooks; that white women might often step on the backs of more marginalised people to reach closer to the top of the power pyramid. As hooks puts it:

As a group, black women are in an unusual position in this society, for not only are we collectively at the bottom of the occupational ladder, but our overall social status is lower than that of any other group. Occupying such a position, we bear the brunt of sexist, racist, and classist oppression. At the same time, we are the group that has not been socialized to assume the role of exploiter/oppressor in that we are allowed no institutionalized "other" that we can exploit or oppress. (…) White women and black men have it both ways. They can act as oppressor or be oppressed. Black men may be victimized by racism, but sexism allows them to act as exploiters and oppressors of women. White women may be victimized by sexism, but racism enables them to act as exploiters and oppressors of black people. Both groups have led liberation movements that favor their interests and support the continued oppression of other groups. Black male sexism has undermined struggles to eradicate racism just as white female racism undermines feminist struggle. As long as these two groups or any group defines liberation as gaining social equality with ruling class white men, they have a vested interest in the continued exploitation and oppression of others. (hooks 1984, 14-15) [my bolding of text]

Now, one might argue that hooks leaves out some power structures here, such as ableism and homophobia, but her point about white women’s complicity in white patriarchy still stands. Coulter is, in my opinion, an extreme version of this. She attempts to gain power as a woman in a patriarchal world, which might garner sympathy, but she does it by exploiting children, mainly children from marginalised groups in society. Feminist scholars Cinza Arruzza, Cinzia, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser describe rich white women’s actions in the context of neo-colonial actions (a context which I will return to further on) like this:

But there is nothing feminist about ruling-class women who do the dirty work of bombing other countries and sustaining regimes of apartheid; of backing neocolonial interventions in the name of humanitarianism, while remaining silent about the genocides perpetrated by their own governments; of expropriating defenseless populations through structural adjustment, imposed debt, and forced austerity. In reality, women are the first victims of colonial occupation and war throughout the world. They face systematic harassment, political rape, and enslavement, while enduring the murder and maiming of their loved ones, and the destruction of the infrastructures that enabled them to provide for themselves and their families in the first place. We stand in solidarity with these women-not with warmongers in skirts, who demand gender and sexual liberation for their kin alone. To the state bureaucrats and financial managers, both male and female, who purport to justify their warmongering by claiming to liberate brown and black women, we say: Not in our name. (2019, 53)

Another relevant point to raise here is Coulter’s connection to the zombi. We first hear about these people in Northern Lights, where Lord Asriel explains:

[S]he’s travelled in many places, and seen all kinds of things. She’s travelled in Africa, for instance. The Africans have a way of making a slave called a zombi. It has no will of its own; it will work day and night without ever running away or complaining. (Pullman 2011a, 373)

In the same passage Asriel explains that it was from things like these the GOB arose, and it seems like the zombi soldiers were also made use of. They are mentioned again in The Subtle Knife when the Magisterium is mustering an army in Trollesund, and it seems like they might have been brought on an “African” ship (Pullman 2011b, 41-42). Then later it is noted that Coulter are using men that have undergone intercision as her personal bodyguards/slave soldiers, which one might assume is the same as these zombi (ibid, 199). She is using her power to gain protection by having these slaves, once again climbing to power on the backs of those more marginalised than her.

The Magisterium’s control and colonization of Asia Minor

Moving on from the Magisterium and Marisa Coulter’s attempts to control the North, I now want to consider the Magisterium and Marcel Delamare’s attempts to control parts of Asia Minor in The Secret Commonwealth. In The Secret Commonwealth we are introduced to Marisa Coulter’s brother Marcel Delemare, who just as his sister is trying to gain power in the Magisterium. His way of doing this is through the organisation La Maison Juste, and by reshaping the Magisterium itself by making use of recent “troubles” in Asia. The reader gets several hints that he himself might be responsible for these troubles by the text saying that he was very aware of these “men from the mountains” (Pullman 2019, 212), and then Oakley Street thinking that these men might come from closer to Europe, rather than from further east in Asia (ibid, 243). In either case, Delamare uses these “troubles” to argue for more centralised control from the magisterium (ibid, 270), a power that he then gets sole control over. Another telling moment is when the director of Oakley Street has this discussion with a friend of the organisation about why the Magisterium is assembling a strike force:

‘To invade Central Asia. There’s talk of a source of valuable chemicals or minerals or something in the desert in the middle of some howling wilderness, and it’s a matter of strategic importance for the Magisterium not to let anyone else get at it before they do. There’s a very strong commercial interest as well. Pharmaceuticals, mainly. (…)’

‘They can’t invade anywhere without an excuse. What’ll it be, d’you think?’

‘That’s what all the diplomacy’s about. I heard that there is or was some sort of science place- a research institute or something- at the edge of the desert concerned. There were scientists from various countries working there, including ours, and they’ve been under pressure from local fanatics, of whom there are not a few, and the casus belli will probably be a confected sense of outrage that innocent scholars have been brutally treated by bandits or terrorists, and the Magisterium’s natural desire to rescue them.’ (Pullman 2019, 592)

As I discussed in the previous section about Once Upon a Time in the North, this practice of using terror as an excuse to invade a region to (partly) get access to natural resources definitely have parallels to our world.

A longstanding justification for colonialism is that “civilised” society shall save the “barbaric” other from itself, and as scholar Margret Denike points out, that has in current times turned into a justification for foreign intervention by for instance the US (2008). As she puts it:

I look to the narratives of progress and human rights triumphalism, and their concomitant campaigns of fear against an allegedly lawless and evil other, as performative gestures in and by which the very distinctions between civilized and uncivilized states are constituted; and the legitimacy or illegitimacy of their public acts of violence are forged. Relating these processes to the politics of gender and racial colonization, I consider how the utilization of human rights discourses, in conjunction with the language of self-defense, relies on and reinforces the selective and strategic denial of humanity and citizenship to the very groups of people-such as Muslim women and refugees-that have been made to symbolize its cause (Chinkin, Wright, and Charlesworth 2005, 28). There is a certain political economy to the strategic deployment of human rights discourses by colonial and imperial states that have sights set on the profits of war, the operations and effects of which can be mapped through a resurgence of new modalities state sovereignty. (2008, 97)

As Denike further points out, religious (specifically Christian) arguments are often just right below the surface in such discourses about saving the racial Other from evil. Furthermore, it is very common that women specifically are in focus in such arguments, playing on the old trope of “white men saving brown women from brown men” (Denike 2008, 105). This can for instance be seen in the US’s (and the EU’s and NATO’s) “war on terror” where much focus was put on liberating Muslim women. She writes:

Indeed, the fact that ‘daily security for women has been reduced’ in the aftermath of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq throws into relief the sad irony of the tale that this has been a “war for women” (Chinkin, Wright, and Charlesworth 2005, 19) and clarifies the gendered politics of Western imperialism’s investment in so-called security. As a counterpart to the docile bodies of veiled and tormented women appears the monstrously demonic, lawless, male terrorist looming larger than life in the fairy tales of triumph against evil. In the talk of the ‘terrorists’ of our time, relatively powerless Muslim and Arabic refugees and immigrants are ascribed, with utter credulity, the powers of mass destruction and plots of imminent nuclear attacks and marked as marginal by racial, religious, or ethnic difference, made to bear the cost of the (seemingly justified) demand for retribution. (2008, 106)

Another aspect I want to raise here, is which lives are sacrificed in such invasions. Which lives are mourned, which lives are acknowledged as human lives at all? Writing about the “war on terror” as well, feminist scholar Judith Butler notes that:

Our own acts of violence do not receive graphic coverage in the press, and so they remain acts that are justified in the name of self defense, but by a noble cause, namely, the rooting out of terrorism. At one point during the war against Afghanistan, it was reported that the Northern Alliance may have slaughtered a village: Was this to be investigated and, if confirmed, prosecuted as a war crime? When a bleeding child or dead body on Afghan soil emerges in the press coverage, it is not relayed as part of the horror of war, but only in the service of a criticism of the military's capacity to aim its bombs right. We castigate ourselves for not aiming better, as if the end goal is to aim right. We do not, however, take the sign of destroyed life and decimated peoples as something for which we are responsible, or indeed understand how that decimation works to confirm the United States as performing atrocities. Our own acts are not considered terrorist. (Butler 2004, 7)

One might very well wonder the same when the Magisterium sacrifices the lives of thousands to gain power in Asia.

I also do not think it’s a coincidence that we learn of private (Western) corporations’ interest in resources in both The Secret Commonwealth and Once Upon a Time in the North. As Arruzza, Bhattacharya and Fraser note, capitalist interest are often very much intertwined with neo-colonial interventions: “Throughout the world, leading capitalist interests (Big Fruit, Big Pharma, Big Oil, and Big Arms) have systematically promoted authoritarianism and repression, coups d'etats and imperial wars.” (2019, 52) Perhaps the worst instance of capitalism interest in this area in The Secret Commonwealth is the trafficking of daemons, and essential enslavement of their humans (mostly Tajik people, who seem to be a marginalised ethnic group). As the priest that Lyra meets puts it:

‘It’s poverty,’ he said. ‘There’s a market for daemons. Medical knowledge here is quite advanced, unlike other things. Big corporations are behind it. They say the medical companies are experimenting here before expanding into the European market. There’s a surgical operation… Many people survive it now. Parents will sell their children’s daemons for money to stay alive. It’s technically illegal, but big money brushes the law aside… When the children grow up, they’re not full citizens, being incomplete.’ (Pullman 2019, 660)

This practice obviously reminds the readers of what the Magisterium and the GOB was doing at Bolvangar, but here it is done by big corporations being able to skirt the law by means of their money. It also seems like the companies doing it are European, since it’s stated that they are experimenting here before expanding to the European market. It also bears a similarity to how the Magisterium and Coulter used zombi as slave soldiers. In general, in The Secret Commonwealth we see how the world of His Dark Materials are not simply full of corrupt religious authority, but also corrupt capitalist corporations who are often collaborating with the religious organisations. Another thing this reveal about the way the Tajik are treated does is make clear that the East is “bad”, in a way that seems very similar to how similar areas are seen in our own world (which I discussed above in relation to “the war on terror”). This is also extremely clear in the scene where Lyra is sexually assaulted on the train, and perhaps especially in the aftermath of that when the sergeant of the soldiers assaulting her advices her to wear a niqab in the future (Pullman 2019, 642). This combined with Lyra’s dislike of wearing a niqab later, “it looked neat enough. And safe. And nullifying.” (ibid, 664), seems to indicate a view that women are especially oppressed in this area of the world, and especially by wearing clothing such as a niqab. This is a contrast to the view of many Muslim women who do wear niqabs, who might describe the experience of wearing a niqab as liberating and empowering and see the niqab as an identity signifier (Zempi 2016).

Another aspect of this neo-colonial activity in Asia in The Secret Commonwealth that I want to consider is that it forces people to flee their homes and attempt to seek refuge in Europe. In her travels Lyra sees several of these refugees, first in Prague where her guide Kubiček explains:

‘More of them arrive every day. The Magisterium has begun to encourage each province of the Church to regulate its territory with a firmer hand. In Bohemia things are not yet as savage as elsewhere; refugees are still given sanctuary. But that can’t go on indefinitely. We shall have to begin turning them away before too long.’ (Pullman 2019, 409)

It’s interesting here that the Magisterium is telling provinces of the Church to regulate immigration, it seems similar to what the EU might do in our world. Well, these people have at least managed to make their way to Prague, later Lyra sees people on a boat trying to cross the Mediterranean (Pullman 2019, 483). This clearly seems to be a reference to refugees in our world attempting the same, especially during and after the so called 2015 “refugee crisis” in Europe. Many have criticised this labelling, since it turns the refugees into the crisis, not the war and other circumstances that has led to them having to flee. As researcher Ida Danewid points out, it reduces the crisis to something Europe have to handle only when it reaches its shores:

By divorcing the ongoing Mediterranean crisis from Europe’s long history of empire and racial violence, these left-liberal interventions ultimately turn questions of accountability, guilt, restitution, repentance, and structural reform into matters of empathy, generosity, and hospitality. The result is a politics of pity rather than justice, to borrow the words of Hannah Arendt, and a consequent recasting of the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed as one between the lucky and the unlucky. As anti-colonial scholars such as Césaire, Cabral, and Fanon remind us, such wilful amnesia sits at the heart of the colonial project. Charles Mills and Linda Alcoff have recently described this as ‘an epistemology of ignorance’ (of not knowing, or of not wanting to know), as a form of Forgetting or white amnesia through which Western publics come to believe not only that the world is post-colonial and post-racial, but also that the long history of colonialism, racialised indentured servitude, indigenous genocide, and transatlantic slavery have left no traces in culture, language, and knowledge production. (Danewid 2017, 1681)

This seems incredibly similar to how the issue is framed in The Secret Commonwealth. Simply as an issue of lucky versus unlucky, rather as a result of historical and current colonialism from Europe upon the world. Clearly the refugees in The Secret Commonwealth has had to flee due to conflict that is clearly the fault of the Magisterium and big corporations, that are both fuelled by European interests. But still these refugees have to rely on the good will of the countries they’re fleeing to, and hope that they will not close their borders.

Conclusion

In this essay I have attempted to argue that while the history of Lyra’s world in His Dark Materials is different than our own, many of the racist, white supremacy, and colonial powers operate similarly. From the discrimination toward gyptians, to the eugenic like work of the GOB, to the racist and colonial treatment of the bears, to the neo-colonial capitalist and governmental collaboration in Asia Minor, it seems clear that colonialism definitely exist in the world of His Dark Materials. In most of these instances, the religious authority of the Magisterium is at centre, and functions similar to how a colonial power might. But perhaps it would be more accurate to liken it to a neo-colonial power, similar to the EU, NATO, or the US and the way they have acted when attempting to stamp out terror (and in reality, expanding their own power). Just as in our world the colonial history of Lyra’s world is far from over. As Sara Ahmed puts it, racism is an unfinished and ongoing history which impacts how we navigate the world both as individuals, and how the world itself is set up (2006). Hopefully both our fictional heroes and ourselves can continue fighting against it.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Collective Feelings- Or, the Impression Left By Others”. Theory, Culture & Society. 21(2): 25-42.

Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Amnesty. 2020. Human Rights on the Margins: Roma in Europe. https://www.amnesty.org.uk/files/roma_in_europe_briefing.pdf

Arruzza, Cinzia, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser. 2019. Feminism for the 99 percent- a manifesto. New York: Verso. S. 1-59

Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious life. The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London & New York: Verso.

Clark, Colin Robert. 2001. ‘Invisible lives’: The Gypties and Travellers of Britain. PhD thesis, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Danewid, Ida. 2017. ”White Innocence in the Black Mediterranean: Hospitality and the Erasure of History.” Third World Quarterly, 38(7): 1674-1689.

Denike, Margret. 2008. “The Human Rights of Others: Sovereignty, Legitimacy and ‘Just Causes’ for the ‘War on Terror’.” Hypatia, 23(2): 95-121.

Girls Gone Canon. 2020a. His Dark Materials Episode 11- The Subtle Knife Chapters 5-6. March 27, 2020. https://girlsgonecanon.podbean.com/e/his-dark-materials-episode-11-the-subtle-knife-chapters-5-6/

Girls Gone Canon. 2020b. Patreon E21: Lee Scoresby's Spaghetti Western - Once Upon a Time in the North. April 29, 2020. https://www.patreon.com/posts/patreon-e21-lee-36514273

His Dark Materials Wiki. n.d. Lyra's world. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://hisdarkmaterials.fandom.com/wiki/Lyra%27s_world

hooks, bell. 1984. Feminist theory from margin to center. Boston: South End Press.

Lo-Lynx. 2019. The Nordic influences in His Dark Materials. November 22, 2019. https://lo-lynx.tumblr.com/post/189230180712/the-nordic-influences-in-his-dark-materials

Mills, Sara. 2003. ”Gender and colonial space.” In Feminist postcolonial theory: A reader, eds. Lewis, Reina & Sara Mills. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University.

Mohanty Talpade, Chandra. 1988. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review. 30 (Autumn, 1988): 61-8.

Pullman, Philip. 2011a. Northern Lights. London: Scholastic.

Pullman, Philip. 2011b. The Subtle Knife. London: Scholastic.

Pullman, Philip. 2017. Once Upon a Time in the North. New York: Random House.

Pullman, Philip. 2018. La Belle Sauvage. London: Penguin Books.

Pullman, Philip. 2019. The Secret Commonwealth. London: Penguin Books.

Samer.se. n.d. a. “I Guds tjänst” [In the service of God]. Samer. Retrieved August 11, 2020. http://samer.se/4441

Samer.se. n.d. b. “Kolonaliseringen av Sápmi”[The colonalization of Sápmi]. Samer. Retrieved August 11, 2020. http://samer.se/1218

Selling, Jan. 2013. Svensk antiziganism: Fördomens kontinuitet och förändringens förutsättningar [Swedish anti-gypsyism: The continuity of prejudice and the conditions for change]. Limhamn: Sekel bokförlag.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 1997. “Making empire respectable: The politics of race and sexual morality in twentieth-century colonial cultures.” In Dangerous liaisons: Gender, nation & postcolonial perspectives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Zempi, Irene. 2016 “‘It’s a part of me, I feel naked without it’: choice, agency and identity for Muslim women who wear the niqab.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. 39(10): 1738–1754.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alleras/Sarella, The Sphinx traversing boundaries of sex and gender

CW: Transphobia, sexism, racism, sexual violence

Spoiler warning: Spoilers for all A Song of Ice and Fire books.

In A Feast for Crows the reader is introduced to the mysterious Alleras, a student of the Citadel in Oldtown. Alleras is described in the prologue as a slight and comely youth, doted on by the serving girls at the inn The Quill and Tankard. We soon learn that he’s called “The Sphinx” by his friends, and the text tells us: “The Sphinx was always smiling, as if he knew some secret jape. It gave him a wicked look that went well with his pointed chin, widow’s peak, and dense mat of close-cropped jet-black curls.” This description, among other things, have led readers to think that Alleras is actually Sarella Sand, the child of Oberyn Martell (see more of the evidence laid out here). But what are we to make of Sarella’s appearance as Alleras in Oldtown? Is it simply a matter of convenience, since women aren’t accepted at the Citadel? Or could it be something more… queer? In this essay I therefore want to make the argument that it’s possible to read Sarella/Alleras as queer and/or trans character as well.

Theoretical background: concepts explained

Before I go any further, I want to clarify that I use both trans and queer very broadly here. When writing this essay, I’m mostly inspired by the field of transgender studies, which is described by Susan Stryker (one of its founders as an academic discipline) thusly:

Transgender studies, as we understand it, is the academic field that claims as its purview transsexuality and cross-dressing, some aspects of intersexuality and homosexuality, cross-cultural and historical investigations of human gender diversity, myriad specific subcultural expressions of “gender atypicality,” theories of sexed embodiment and subjective gender identity development, law and public policy related to the regulation of gender expression, and many other similar issues. It is an interdisciplinary field that draws upon the social sciences and psychology, the physical and life sciences, and the humanities and arts. It is as concerned with material conditions as it is with representational practices, and often pays particularly close attention the interface between the two. (…) Most broadly conceived, the field of transgender studies is concerned with anything that disrupts, denaturalizes, rearticulates, and makes visible the normative linkages we generally assume to exist between the biological specificity of the sexually differentiated human body, the social roles and statuses that a particular form of body is expected to occupy, the subjectively experienced relationship between a gendered sense of self and social expectations of gender-role performance, and the cultural mechanisms that work to sustain or thwart specific configurations of gendered personhood. (Stryker 2006, 3)

That is to say, when I say that I do a trans and queer analysis of a character I’m not necessarily saying that I think the character I’m analysing would identify as trans or queer in the modern conceptualisation of those terms. As I’ll expand on later, different cultures during different times of history have had different ways of conceiving of gender and transness. I do, however, still use trans as an umbrella term for people who disrupts and denaturalises the normative links between sex and gender etc (as Stryker puts it), while recognising that this is a very historically and culturally specific term. I similarly use queer as an umbrella term for that which disrupts normative links between sex/gender and sexuality. However, I do of course realise that people use both trans and queer as identity labels today, and not just theoretical tools (I do that myself). Nevertheless, for the purposes of this essay, I will use trans and queer more as descriptors of a myriad gender/sexuality expressions, than as specific identity labels. Having addressed that, I’ll now go on to some of the theory and analysis.

Theoretical background: trans history

Firstly, I want to take a brief look at research about historical trans people. Afterall, even if ASOIAF makes use of modern conceptualisations of gender, as I’ve argued before, it is set in a medievalesque time. Therefore, it could be useful to consider what we know about trans people historically, and furthermore, how historians have described them. When starting to do research for this essay, I was reminded of an article by Peter Boag which analyses gender nonconformity in the American West during the late nineteenth century (2005). While this is not the same time period as ASOIAF, I think his arguments can be applied to how trans people have been conceived of generally in research. He writes: “Feminist scholars and popular writers of women’s history have traditionally ignored the possibility of transgenderism among " female-to-male" cross-dressers of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century West.” (ibid, 477) (Note: I would not use the term “transgenderism” today, but while the terminology is a bit dated in this article, the arguments still stand) He further notes that while feminist scholars have written about the existence of people who lived as another gender than they were assigned at birth during this time, they haven’t usually been interpreted as trans. When it comes to people who were assigned female at birth, but presented as men, they have usually been interpreted either as women attempting to find a place in a patriarchal world, or possibly as lesbians. One obstacle to analysing the existence of trans people during this time is of course the lack of sources (and obviously the fact that the term “transgender” didn’t exist then, even if gender nonconforming people did). However, as Boag also writes:

Further obfuscating the trans in the gender history of the West is the narrative structure that scholars and popular writers have employed to tell the story of the cross dresser. Marjorie Garber has termed this storytelling device the "progress narrative." Within it, transvestism is normalized, the argument being that the subject changed her clothing in order to obtain employment in a man's world, or because she wanted to succeed in a profession that her biological sex otherwise excluded her from, or because she needed to support her family, or because she desired to follow a husband or male lover into a milieu, such as the army, which excluded women. While the progress narrative has been a storytelling device utilized by scholars who have studied cross-dressing "women" in all eras and places, it has been particularly strong in the historiography of the West. (Boag 2005, 483)

Now, Boag also notes that women at the time (and at other times) might have cross-dressed for these (more practical) reasons too. But the records that do exist also indicates that others didn’t just dress as men, they considered themselves to be men, and some were considered as such by their community too, even when said community suspected they were assigned female at birth.

The description of this “progress narrative” is reminiscent of a lot of what trans activist and researcher Leslie Feinberg describes in hir ground-breaking book on trans history, Transgender warriors (1996). Feinberg describes that book as:

Transgender Warriors is not an exhaustive trans history, or even the history of the rise and development of the modern trans movement. Instead, it is a fresh look at sex and gender in history and the interrelationships of class, nationality, race, and sexuality. Have all societies recognized only two sexes? Have people who traversed the boundaries of sex and gender always been so demonized? Why is sex-reassignment or cross-dressing a matter of law? But how could I find the answers to these questions when it means wending my way through diverse societies in which the concepts of sex and gender shift like sand dunes over the ages? And as a white, transgender researcher, how can I avoid foisting my own interpretations on the cultures of oppressed peoples' nationalities?(…). I've also included photos from cultures all over the world, and I've sought out people from those countries and nationalities to help me create short, factual captions. I tried very hard not to interpret or compare these different cultural expressions. These photographs are not meant to imply that the individuals pictured identify themselves as transgender in the modern, Western sense of the word. Instead, I've presented their images as a challenge to the currently accepted Western dominant view that woman and man are all that exist, and that there is only one way to be a woman or a man. (ibid, XI)

I include this whole quote because thought it was important to preface the discussion of Feinberg’s arguments in this book by explaining hir intent with the book, and how zie reasoned while researching and writing it. Now, throughout the book Feinberg writes about how different people throughout history have traversed the boundaries of sex and gender (I love how zie puts that), including for instance Joan of Arc. Zie describes how researching Joan of Arc was one of the inspirations of this entire book, when zie started thinking about the fact that: “If society strictly mandates only men can be warriors, isn’t a woman military leader dressed in armor an example of cross-gendered expression?” (ibid, 31) When researching Joan of Arc zie realised that the fact that she dressed in “men’s garb” did contribute to her persecution by the Inquisition, and that was ultimately the crime for which she was killed. Feinberg also notes that Joan were often referred to as “hommasse”, a slur meaning man-woman. Allow me to quote Feinberg again:

The English urged the Catholic Church to condemn Joan for cross-dressing. The king of England, Henry VI, wrote to the infamous Inquisitor Pierre Cauchon, the Bishop of Beauvais: "It is sufficiently notorious and well-known that for some time past a woman calling herself Jeanne the Pucelle (the Maid) , leaving off the dress and clothing of the feminine sex, a thing contrary to divine law and abominable before God, and forbidden by all laws, wore clothing and armour such as is worn by men." Buried beneath this outrage against Joan's cross-dressing was a powerful class bias. It was an affront to nobility for a peasant to wear armor and ride a fine horse. (…) On April 2, 1431, the Inquisition dropped the charges of witchcraft against Joan, because they were too hard to prove. Instead, they denounced her for asserting that her cross-dressing was a religious duty compelled by voices she heard in visions, and for maintaining that these voices were a higher authority than the Church. Many historians and academicians view Joan of Arc's wearing men's clothing as inconsequential. Yet the core of the charges against Joan focused on her cross-dressing, the crime for which she ultimately was executed. (…) Even though she knew her defiance meant she was considered damned, Joan's testimony in her own defense [sic] revealed how deeply her cross-dressing was rooted in her identity. "For nothing in the world," she declared, "will I swear not to arm myself and put on a man's dress.” (ibid, 34-35)

(Note: I find it interesting that Henry VI pops up here, considering that GRRM has said that he and The War of the Roses on a whole has influenced ASOIAF, but I’m not sure exactly what to make of it.) It seems clear then that Joan of Arc were persecuted partly because she insisted on dressing in “men’s clothes”. Now, one could argue that Joan only cross-dressed for practical reasons. That’s an argument that’s often brought up with historical people who traversed sex and gender boundaries, like Boar also writes (2005). Feinberg discusses this in hir book as well, and how zie have heard similar explanations of hir own life:

"No wonder you've passed as a man! This is such an anti-woman society," a lesbian friend told me. To her, females passing as males are simply trying to escape women's oppression - period. She believes that once true equality is achieved in society, humankind will be genderless. I don't have a crystal ball, so I can't predict human behavior in a distant future. But I know what she's thinking – if we can build a more just society, people like me will cease to exist. She assumes that I am simply a product of oppression. Gee, thanks so much. (Feinberg 1996, 83).

That is to say, we should be careful when assuming that gender nonconforming people of the past are “simply a product of oppression.” Feinberg also makes the important point that, for instance, someone being assigned female at birth presenting as a man isn’t necessarily safer than if they were to continue presenting as a woman. If other people discover the circumstance of one’s birth that can lead to quite a lot of violence.

The last point I want to make about historical trans people before moving on is the need to consider the context of the narratives we have about such people. In their PhD thesis Fleshing out the self- Reimagining intersexed and trans embodied lives through (auto)biographical accounts of the past trans scholar M. Holm cautions against both taking historical accounts of transness too literally and viewing them through a contemporary lens too much (2017). When analysing trans and intersex accounts from the beginning of the 20th century they write:

My postmodern approach to experience and experiential accounts means that I do not read the (auto)biographical texts as representational accounts in relation to a project of discovering the hidden truth about how it was to be an intersex or trans person (understood from current definitions and as stable identity categories) during the first three quarters of the 20th century. (…) I regard (auto)biographical accounts as containing traces of events, bodies, feelings, actions, relationships, institutions, politics, and much more that existed in this period and made specific kinds of impressions on individuals, in relation to which they have acted. However, I do not regard any account as an unmediated representation of, or truthful testimony to, any of these phenomena. Rather, I perceive all accounts as articulations that are dependent on the concepts and narrative models available to the narrator and on the general socio-historical and specific local and temporal situation of their narration, including the narrator’s specific relation to the receiver(s) of the account and the conscious and unconscious intentions, hopes, and fears related to the telling. (ibid, 70) [my bolding of the text]

That is to say, the way someone describes their gender is dependent on the circumstances surrounding this description, including the concepts and language available to them. As Holm outlines further on in their thesis, at times trans people might have had to tell their stories in accordance to certain narratives in order to get access to health care, or simply to make themselves make sense to other people.

All of this is essentially to say that since we don’t know how Sarella/Alleras would describe their gender themselves, we can’t be sure that they’re presenting as a man just to gain access to a male institution (the Citadel). As Boag points out with similar examples from the 19th century, this might be a contributing factor, but one should not assume it’s the only factor in play. Furthermore, as Feinberg writes, someone being assigned as female at birth but presenting as a man is not necessarily safer for it. This is something I’ve explored in an ASOIAF context before, for instance in this text about Brienne and Arya. I’ll return to some of these historical parallels further on, but before that I want to look at some more theory on traversing boundaries of sex and gender.

Theoretical background: queering and trans-ing gender

In his book Female Masculinity Jack Halberstam writes about masculinity is interpreted in people who were assigned female at birth (1998). He notes that:

Tomboyism tends to be associated with a ‘natural’ desire for the greater freedoms and mobilities enjoyed by boys. Very often it is read as a sign of independence and self-motivation, and tomboyism may even be encouraged to the extent that it remains comfortably linked to a stable sense of a girl identity. Tomboyism is punished, however, when it appears to be the sign of extreme male identification (taking a boy’s name or refusing girl clothing of any type) and when it threatens to extend beyond childhood and into adolescence. (ibid, 6)

Here we once again see how masculinity in “girls” is interpreted as a wish for freedom, while more persistent masculine identification is punished. Halberstam goes on to discuss how lesbians are often seen as masculine (in our contemporary society), writing that “the bulldyke, indeed, has made lesbianism visible and legible as some sort of confluence of gender disturbance and sexual orientation.” (ibid, 119) He also notes that black women are generally seen as more masculine than white women, and that black lesbians are often stereotyped as the “butch bulldagger”. All this is to say that bodies who are assigned female at birth can inhabit masculinity in a myriad of ways, and both race and sexuality is often tied up in how the surroundings perceive their gender. Halberstam also makes note of how the concept of passing as a gender is not necessarily a useful concept for all gender nonconforming bodies:

For many gender deviants, the notion of passing is singularly unhelpful. Passing as a narrative assumes that there is a self that masquerades as another kind of self and does so successfully; at various moments, the successful pass may cohere into something akin to identity. At such a moment, the passer has become. What of a biological female who presents as butch, passes as male in some circumstances and reads as butch in others, and considers herself not to be a woman but maintains distance from the category ‘man’? For such a subject, identity might best be described as process with multiple sites for becoming and being. (ibid, 21)

(Note: when Halberstam writes “gender deviants” he means it in the eyes of society, he’s not condemning such people himself). What Halberstam says here is essentially that a person might pass/read differently in different situations, and for some that might mean that their identity is a bit fluid (“a process with multiple sites for becoming and being”). I think this is relevant to connect to what another trans studies scholar, Signe Bremer, writes about passing, as well as interpellation (2017). I wrote more about Bremer’s arguments in this essay about Brienne, but essentially Bremer describes the act of passing as having one’s body become invisible when inhabiting a space, and thus fitting comfortably (ibid, 134). Bremer furthermore writes about interpellation:

What is meant with interpellation, in the way that Judith Butler conceives of it, is the performative acts of speech through which bodies, by the act of being named, step into the sphere of coherence, and are constituted as possible subjects and ‘real’ people. (ibid, 196) (my translation)

What Bremer is saying here, is that when someone is named as something (for instance as a man), that person is understood as that thing (for instance as a man). People and society make sense of someone through the naming of them. Bremer also notes, however, that interpellation does not require the consent of the individual, interpellation can also be forced upon the individual. This is because, for a body to be interpaled it must follow the lines/norms of society which makes it possible for the body to be recognised as a human. As Bremer notes, this can often result in trans people being interpaled as a wrong gender.