Text

“plot armor” is so funny as an idea. I can’t believe the author used this character in a thematically coherent way instead of killing them off randomly in the fourth chapter…

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

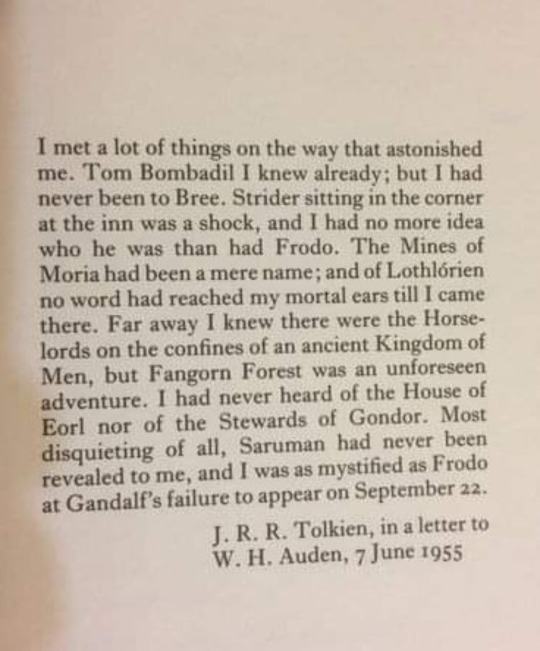

Posting this for the people who think that Tolkien's world-building was something complete and entire and finished before he started to write.

You always learn and discover your story and your world as you write. Sometimes you are just the first reader.

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Name Your Side Characters

Names are one of the hardest things for audiences to remember. As such, you should avoid naming characters unless you absolutely have to because you cannot rely on audiences to remember names.

To illustrate this, let’s play a quick memory game. I’m going to give you a string of numbers and then I’m going to give you a string of words. Read each string, then close your eyes and try to remember what you just read. Then repeat the exercise with the other string. Don’t try to memorize these examples, just read them once and see what you remember.

743432589

I love to eat pie! It’s such a yummy food.

I’m going to make a wild guess and say that you were probably able to remember at least the general gist of the stuff about pie, but the random numbers probably didn't stick at all. Now let’s play that game again, but with two different examples.

123456789

House tall strawberry flake song tight man you cat run

This time, the numbers were probably easy while the words were in one ear and out the other. This is because of the way that our brains process and store information. We like patterns and things that make logical sense. Randomness is a lot harder to make stick and names are largely random. It’s why they're something that people struggle with when they meet real life people and there they have cheats like being able to associate a face with a name. When it comes to literature, names are just words on a page. It takes repetition for them to stick, which is why naming your main character is fine. The audience will hear their name a lot and come to remember it pretty quickly. But if you name a random student “Henry” on page 34 and then bring that student back on page 160, no one is going to remember who “Henry” is. You’re going to have to remind them.

That doesn’t mean that Henry must go nameless. If there’s a good reason to give Henry a name, then go for it! Just don’t rely on the name being an effective shorthand that you can use to jog people’s memories if you only drop the name once. Here's an alternate way to introduce "Henry":

Ms. Hardmon’s eyes scanned the classroom, looking for victims. They finally settled on a red-headed boy in the front row.

“What is the square root of nine?” she demanded.

The attention obviously startled him, but he still managed to quickly stutter out, “Three?”

Ms. Hardmon frowned and sighed, "That is correct."

You can then go on to later give his name or he can fade into obscurity never to be seen again. You can also avoid calling attention to any one person in a scene like this, thereby also avoiding needing to drop random names.

Ms. Hardmon’s eyes scanned the classroom, looking for victims. Every time they found one, she'd bark out a question.

“What is the square root of nine?”

"What's four squared?"

"What's the cubed root of eight?"

And every time, the unfortunate student would blurt out an answer, praying that they'd gotten it right. They all did, much to Ms. Hardmon’s annoyance.

Avoiding random names is especially important at the start of a story. At that point, the audience is learning a lot of new information, so avoiding unimportant information like random names is a kindness and will make your story more readable.

Yes, it does make it easier to guess who the important characters are. In most cases, that's a feature, not a flaw.

Along similar lines, when you introduce a character whose name the audience needs to remember, try to repeat their name a lot to help make it stick. Like there's a good chance that you remember that my fictional teacher is named Ms. Hardmon since I dropped that name four times in rather quick succession.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing advice from my uni teachers:

If your dialog feels flat, rewrite the scene pretending the characters cannot at any cost say exactly what they mean. No one says “I’m mad” but they can say it in 100 other ways.

Wrote a chapter but you dislike it? Rewrite it again from memory. That way you’re only remembering the main parts and can fill in extra details. My teacher who was a playwright literally writes every single script twice because of this.

Don’t overuse metaphors, or they lose their potency. Limit yourself.

Before you write your novel, write a page of anything from your characters POV so you can get their voice right. Do this for every main character introduced.

199K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro-writing tip: if your story doesn't need a number, don't put a fucking number in it.

Nothing, I mean nothing, activates reader pedantry like a number.

I have seen it a thousand times in writing workshops. People just can't resist nitpicking a number. For example, "This scifi story takes place 200 years in the future and they have faster than light travel because it's plot convenient," will immediately drag every armchair scientist out of the woodwork to say why there's no way that technology would exist in only 200 years.

Dates, ages, math, spans of time, I don't know what it is but the second a specific number shows up, your reader is thinking, and they're thinking critically but it's about whether that information is correct. They are now doing the math and have gone off drawing conclusions and getting distracted from your story or worse, putting it down entirely because umm, that sword could not have existed in that Medieval year, or this character couldn't be this old because it means they were an infant when this other story event happened that they're supposed to know about, or these two events now overlap in the timeline, or... etc etc etc.

Unless you are 1000% certain that a specific number is adding to your narrative, and you know rock-solid, backwards and forwards that the information attached to that number is correct and consistent throughout the entire story, do yourself a favor, and don't bring that evil down upon your head.

#understanding how minds work is actually a great way to improve your writing#be it linguistics or just general facts about memory

82K notes

·

View notes

Text

I tried to write a novel. Not once. Not twice. But about 12 times. Here's how that would play out:

1. I sit down and knock out 10 pages

2. I share it with someone

3. They say "It's goooood" like it's not good

4. I ask for critical feedback

5. They say, "Well....the plot just moves so quickly. So much happens in the first few pages it doesn't feel natural."

So I'd write more drafts. I'd try to stretch out the story. I would add dialogue that I tried to make interesting but thought was boring. I would try including environment and character descriptions that felt unnecessary, (why not just let people imagine what they want?)

Anyways, I gave up trying to write because in my mind, I wasn't a fiction writer. Maybe I could write a phonebook or something.

But then I made a fiction podcast, and I waited for the same feedback about the fast moving plot, but guess what???

Podcasts aren't novels. The thing that made my novels suck became one of the things that made Desert Skies work. I've received some criticism since the show started, but one thing I don't receive regular complaints about is being overly-descriptive or longwinded.

In fact, the opposite. It moves fast enough that it keeps peoples attention.

I always felt I had a knack for telling stories but spent years beating myself up because I couldn't put those stories into novel form. The problem wasn't me. The problem was the tool I was trying to use.

All that to say:

If, in your innermost parts you may know that you're a storyteller but you just can't write a book, don't give up right away. You can always do things to get better and there's a lot of good resources.

But if you do that for a while and novel writing just isn't your thing, try making a podcast, or creating a comic, or a poem, or a play, or a tv script.

You might know you're an artist but suck at painting. Try making a glass mosaic, or miniatures, or try charcoal portraits, or embroider or collage.

You might know you're a singer, but opera just isn't working out. Why not yodel?

I could keep listing out examples, but the point is this. Trust your intuitions when it comes to your creative abilities, but don't inhibit yourself by becoming dogmatic about which medium you can use to express that creativity.

Don't be afraid to try something new. Don't be afraid to make something new. You might just find the art form that fits the gift you knew you always had, and what it is might surprise you

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's hard to give advice as to how to start writing stories because, unlike other art forms, there's not really a clear step-by-step guide for how to do the basics. If you look up how to draw a face, you're going to find a bunch of similar guides that will let you develop basic skills that you can then expand upon to develop your own style. Writing isn't like that.

Stories can be written linearly, backwards, in random chunks, and so on. Concepts like pacing are nebulous without a true right and wrong. Word choice is incredibly personal to the author with most authors having Strong Opinions. These opinions are incredibly important to the individual author as it's how they know when they've written a good story, but the reason they need that is because there's no objective standard to meet. One reader's favorite novel is another's boring slog brimming with childish prose. If you want an example of this, then look up "using adjectives in writing" and you will find articles telling you to never use them and articles defending them.

That's why one of the most common pieces of writing advice is "read." Consuming literature is the best way to figure out what you consider a good story. It's how I learned to write and, if you want to be a writer, it's really the only way to develop your personal standard for what makes a good story.

You can also look for guides on how to write a novel and find articles and books where authors talk about their writing styles. Reading through these can help if you have no idea how to approach the topic, but I'll admit that I've never used them. I developed my style on my own purely through trial and error, but I've talked to enough writers to know that it's not an uncommon style and I've explained it to new writers who claimed that it was useful, so here you go:

I call my writing style "spark noting". When I get an idea, I write out a spark-notes or Wikipedia-style summary of the idea. I rarely know the whole summary when I start writing it. I figure it out as I go, which lets me find the general flow of the story. It includes the big plot points, but can also have details on little ideas that I love and want to include. Then I take that summary and start writing it piece by piece, expanding it from summary to novel.

I'm a linear, one-draft writer, which means that I write the story in the same order that a reader will read it. It also means that I work on each chapter until I feel like it's 95% to 100% complete and only then move on to the next. Some people will draft the whole novel without editing and then take it through multiple edits, but that doesn't work for me. I need part A to be set in stone before starting on part B because if A changes, then B changes and so on. It doesn't mean that my first finished draft will be absolutely perfect, but it should be in a state that just needs some minor polishing.

I have no idea if that's what you were looking for, but I didn't see any answers like this after a quick scan of the reblogs so here you go.

Hey! Question for writers. How do you do that

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have … a tip.

If you’re writing something that involves an aspect of life that you have not experienced, you obviously have to do research on it. You have to find other examples of it in order to accurately incorporate it into your story realistically.

But don’t just look at professional write ups. Don’t stop at wikepedia or webMD. Look up first person accounts.

I wrote a fic once where a character has frequent seizures. Naturally, I was all over the wikipedia page for seizures, the related pages, other medical websites, etc.

But I also looked at Yahoo asks where people where asking more obscure questions, sometimes asked by people who were experiencing seizures, sometimes answered by people who have had seizures.

I looked to YouTube. Found a few individual videos of people detailing how their seizures usually played out. So found a few channels that were mostly dedicated to displaying the daily habits of someone who was epileptic.

I looked at blogs and articles written by people who have had seizures regularly for as long as they can remember. But I also read the frantic posts from people who were newly diagnosed or had only had one and were worried about another.

When I wrote that fic, I got a comment from someone saying that I had touched upon aspects of movement disorders that they had never seen portrayed in media and that they had found representation in my art that they just never had before. And I think it’s because of the details. The little things.

The wiki page for seizures tells you the technicalities of it all, the terminology. It tells you what can cause them and what the symptoms are. It tells you how to deal with them, how to prevent them.

But it doesn’t tell you how some people with seizures are wary of holding sharp objects or hot liquids. It doesn’t tell you how epileptics feel when they’ve just found out that they’re prone to fits. It doesn’t tell you how their friends and family react to the news.

This applies to any and all writing. And any and all subjects. Disabilities. Sexualities. Ethnicities. Cultures. Professions. Hobbies. Traumas. If you haven’t experienced something first hand, talk to people that have. Listen to people that have. Don’t stop at the scholarly sources. They don’t always have all that you need.

103K notes

·

View notes

Text

I didn't think to mention this exception in the original post, but it's absolutely true. If the thoughts are related to the dialogue, then yes, you can often get away with including them!

My advice for that is:

Remember that the focus of the scene is the dialogue and only include the thoughts that are necessary for the audience to follow along. The things we think while talking tend to be quick flashes, so that's how I tend to include moments like this. If it's something that's going to take paragraphs, bringing it up mid-dialogue is probably still the wrong way to do it even if it fits the conversation.

Try to limit this technique to dialogue where the audience needs to remember the topic, but not the words. The above example is just playing off of mine, so don't take this as criticism of the choice given here, but it is a prime example of a place where I'd rephrase Mary's comment or avoid adding thoughts because the audience might get confused since they need to remember Mary's question for Ryan's response to make sense. I'm going to redo it to show what I mean and hopefully it will be self-explanatory when you compare the two:

Mary laughed, the sound making Ryan's traitorous heart skip a beat. Then she said, “Gosh, every time I drink this soda, I think of that night with Jimmy and the cat!”

Ryan thought back to that night Jimmy had come in with the kitten looking like it had drowned in blue raspberry soda and smelling like Fanta. He had demanded everyone help him clean it up, sending several of them on errands to get supplies, food, and a collar. It had been after daylight before any of them had been able to get to sleep.

“That was a wild night! I still don’t know where he found the poor thing!” Ryan said, gazing at her with melancholy fondness. “Did he ever tell you?”

There might very well be other exceptions that I didn't think of, which is a good thing to keep in mind! Writing is about communicating. If you think that your story is clear, then it doesn't matter if you break every rule in the book because they're not really rules. They're more like guidelines or even just opinions.

Generally speaking, it's good to understand why writers give the advice they do instead of just following it blindly, which is why I try to focus on the why and don't just give guidelines. When you understand the why, then it's up to you to decide where and when a guideline can be ignored even if you generally agree with it. If you think that you've found an exception, then ignore the guideline and do what feels best to you! Writing is an art, not a science, and there are as many valid writing styles as there are styles of painting.

Don’t Mix Thoughts and Dialogue

During a bit of dialogue, it can be incredibly tempting to give your reader a glimpse of what the characters are thinking. This is a trap. Don’t do it.

Why?

Well, the best way to explain this is to just give you a quick example.

Mary laughed, her eyes sparkling. “Hey, do you remember that night with Jimmy and the cat?”

Ryan smiled, his mind drifting back over the long years of their friendship. That they would still be so close after all this time was truly a gift. Yet a part of him still asked ‘what if?’ What if they were meant to be something other than friends? Could that every happen or was he being greedy? Risking something beautiful for so little gain.

He shook his head, clearing his thoughts. Then he smiled and said, “Yeah, I still don’t know where he got it!”

Question: when you got to Ryan’s response, did you remember what Mary said or did you have to glance back up to jog your memory? If you glanced back up, then don’t feel bad! You are completely normal and that’s why this is a technique that you should use sparingly.

When we’re reading, our brains are constantly processing new information. It’s basically an ongoing memory game! If you’ve ever played one of those, then you know that it can be quite tricky to recall which picture is hiding under which card or what objects were on the now-hidden tray. However, we can always pick up the card or reveal the tray to remind ourselves of the answer. Similarly, we can always glanced back up the page and reread the previous line, but a story isn’t a game. Most writers want their audience to be fully immersed in the scene. Their eyes should travel down the page, following the flow of the words, never needing to look back at what was said three paragraphs ago.

You’re never going to be able to make your audience remember everything that you wrote. There are just too many words in the story. That’s why, when you’re writing dialogue, you want to keep all of the surrounding text related to the dialogue. Don’t let your characters go off on tangents like Ryan did because then your audience’s brain will switch to this new topic and forget the old one the same way that a verbal tangent will lead to someone asking, “Hey, wait, what were we talking about?”

I get the temptation to do the thought thing. It can give some really fun insight into a character. I will do it myself in early drafts. Then, upon rereading, I’ll realize that I switched focus from the dialogue and, as much as I like sharing my character’s thoughts, dialogue just isn’t the place to do it. If you’re including dialogue, the point is usually the interactions between the characters, not their deep, individual thoughts.

In this case of the above, Ryan’s thoughts needed to wait until after the conversation was over OR I should have introduced this topic earlier so that I could briefly hint at Ryan’s feelings with something like:

Mary laughed, the sound making Ryan's traitorous heart skip a beat. Then she asked, “Hey, do you remember that night with Jimmy and the cat?”

“Yeah, I still don’t know where he got it!” Ryan said, gazing at her with melancholy fondness. “Did he ever tell you?”

This is not to say that you can never do the thought thing. You can. Just be aware that it's dragging your audience away from the dialogue and they will likely forget the details of what was being discussed, making it a not-so-great techniquie.

The only time when I’d do that is when I want the character to forget the conversation, too. Then I can bring the character and the audience back to the discussion in a natural way.

I’ll also note that readers do remember things long after they happen. It’s just that what tends to stick are the big, important details (ex: Alim was murdered) or the things that get repeated constantly (ex: the suspect list that the detectives go over after every new clue). Dialogue tends to be largely forgettable as the point is rarely the specific words, which is why breaking a conversation is so jarring.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Abuse Suspension of Disbelief

Today, at 11am GMT, the Bank of England was robbed, a massive prison break occurred at Pentonville Prison, and someone helped themselves to the Crown Jewels. How did the thief do it? A computer program that can break through any security system.

None of this actually happened, btw. It’s merely the setup for The Reichenbach Fall, the season finale of BBC’s Sherlock’s second season, which will serve as today’s object lesson for a thing that I occasionally come across. A thing that you really should avoid at all costs: taking advantage of suspension of disbelief.

If you know even a little bit about computer security, you know that the above setup is total BS. No such program could possibly exist. Application code varies wildly, so it’s impossible to have one program that can hack any application. Even though you know that, you’d probably still be fine watching this episode because you’re willing to ignore reality for the sake of a good story.

That willingness to ignore reality is called ‘suspension of disbelief’ and it’s a vital part of the bond between writer and audience. The audience knows that your story is fiction, not fact, but they’re willing to play along and believe your BS because they assume that the BS is needed for the story to work. Which is why the ending of The Reichenbach Fall is such a massive writing error. For those who haven’t seen the show (and I don’t recommend it), this is the twist: There is no key, DOOFUS!... You don’t really think a couple of lines of computer code are gonna crash the world around our ears? I’m disappointed.

That’s right, the twist of The Reichenbach Fall is that we weren’t supposed to suspend our disbelief. The thing that couldn’t actually exist doesn’t actually exist and how silly were you for thinking that it could?

I should now note that there is no point in The Reichenbach Fall where hints are dropped that the code doesn’t exist. It’s treated as a real threat right up until the twist, meaning that the twist only works because it’s jerking us back to reality and saying, “Get out of fantasy land, this thing obviously couldn’t be real!”

This is terrible storytelling for two reasons: it insults your audience and it makes your story feel pointless.

The audience never actually believed that the code could exist in the real world, but they were willing to believe that, in your story, such a code could exist because everyone was acting like it could. When you drop the bomb that the story world works by real-world logic, you aren’t pulling a shocking twist. Instead, you are making fun of your audience for trusting you because the only reason they believed the BS was because they thought that you needed them to for the sake of the story.

You’ve also ruined your story and made your characters look like idiots because the audience is left wondering why anyone ever believed in the computer code. How did no one know the real way that the robberies were done? Surely there had to be an investigation? Why did the Sherlock ever think the code could be a thing? He’s supposed to be smart, right?

All of the above is why I strongly encourage writers to avoid this type of twist at all costs. If the big reveal is that your fantasy world follows real-world rules, then that needs to be something that the story tells you because the audience is there for the story. They’re there to play pretend with you and part of your job as a storyteller is honoring that. If you're not dropping hints that set up the twist, then you've failed to tell a good story.

#writing advice#suspension of disbelief#bbc sherlock#The post wasn't inspired by Sherlock it was just the best known example of this writing goof that I could think of

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've mentioned this before, but the simple way to sum this up is "Is your character [stereotype] because that's what that gender/race/group/etc is like or is that character [stereotype] because of who they are and how their life has gone?" If it's A, then you have a problem. If it's B, then you're fine. Real people meet stereotypes, too, that doesn't make them lesser and the same can be true of fictional characters.

There’s also a large grey area between an Offensive Stereotype and “thing that can be misconstrued as a stereotype if one uses a particularly reductive lens of interpretation that the text itself is not endorsing”, and while I believe that creators should hold some level of responsibility to look out for potential unfortunate optics on their work, intentional or not, I also do think that placing the entire onus of trying to anticipate every single bad angle someone somewhere might take when reading the text upon the shoulders of the writers – instead of giving in that there should be also a level of responsibility on the part of the audience not to project whatever biases they might carry onto the text – is the kind of thing that will only end up reducing the range of stories that can be told about marginalized people.

A japanese-american Beth Harmon would be pidgeonholed as another nerdy asian stock character. Baby Driver with a black lead would be accused of perpetuating stereotypes about black youth and crime. Phantom Of The Opera with a female Phantom would be accused of playing into the predatory lesbian stereotype. Romeo & Juliet with a gay couple would be accused of pulling the bury your gays trope – and no, you can’t just rewrite it into having a happy ending, the final tragedy of the tale is the rock onto which the entire central thesis statement of the play stands on. Remove that one element and you change the whole point of the story from a “look at what senseless hatred does to our youth” cautionary tale to a “love conquers all” inspiration piece, and it may not be the story the author wants to tell.

Sometimes, in order for a given story to function (and keep in mind, by function I don’t mean just logistically, but also thematically) it is necessary that your protagonist has specific personality traits that will play out in significant ways in the story. Or that they come from a specific background that will be an important element to the narrative. Or that they go through a particular experience that will consist on crucial plot point. All those narrative tools and building blocks are considered to be completely harmless and neutral when telling stories about straight/white people but, when applied to marginalized characters, it can be difficult to navigate them as, depending on the type of story you might want to tell, you may be steering dangerously close to falling into Unfortunate Implications™. And trying to find alternatives as to avoid falling into potentially iffy subtext is not always easy, as, depending on how central the “problematic” element to your plot, it could alter the very foundation of the story you’re trying to tell beyond recognition. See the point above about Romeo & Juliet.

Like, I once saw a woman a gringa obviously accuse the movie Knives Out of racism because the one latina character in the otherwise consistently white and wealthy cast is the nurse, when everyone who watched the movie with their eyes and not their ass can see that the entire tension of the plot hinges upon not only the power imbalance between Martha and the Thrombeys, but also on her isolation as the one latina immigrant navigating a world of white rich people. I’ve seen people paint Rosa Diaz as an example of the Hothead Latina stereotype, when Rosa was originally written as a white woman (named Megan) and only turned latina later when Stephanie Beatriz was cast – and it’s not like they could write out Rosa’s anger issues to avoid bad optics when it is such a defining trait of her character. I’ve seen people say Mulholland Drive is a lesbophobic movie when its story couldn’t even exist in first place if the fatally toxic lesbian relationship that moves the plot was healthy, or if it was straight.

That’s not to say we can’t ever question the larger patterns in stories about certain demographics, or not draw lines between artistic liberty and social responsibility, and much less that I know where such lines should be drawn. I made this post precisely to raise a discussion, not to silence people. But one thing I think it’s important to keep in mind in such discussions is that stereotypes, after all, are all about oversimplification. It is more productive, I believe, to evaluate the quality of the representation in any given piece of fiction by looking first into how much its minority characters are a) deep, complex, well-rounded, b) treated with care by the narrative, with plenty of focus and insight into their inner life, and c) a character in their own right that can carry their own storyline and doesn’t just exist to prop up other character’s stories. And only then, yes, look into their particular characterization, but without ever overlooking aspects such as the context and how nuanced such characterization is handled. Much like we’ve moved on from the simplistic mindset that a good female character is necessarily one that punches good otherwise she’s useless, I really do believe that it is time for us to move on from the the idea that there’s a one-size-fits-all model of good representation and start looking into the core of representation issues (meaning: how painfully flat it is, not to mention scarce) rather than the window dressing.

I know I am starting to sound like a broken record here, but it feels that being a latina author writing about latine characters is a losing game, when there’s extra pressure on minority authors to avoid ~problematic~ optics in their work on the basis of the “you should know better” argument. And this “lower common denominator” approach to representation, that bars people from exploring otherwise interesting and meaningful concepts in stories because the most narrow minded people in the audience will get their biases confirmed, in many ways, sounds like a new form of respectability politics. Why, if it was gringos that created and imposed those stereotypes onto my ethnicity, why it should be my responsibility as a latina creator to dispel such stereotypes by curbing my artistic expression? Instead of asking of them to take responsibility for the lenses and biases they bring onto the text? Why is it too much to ask from people to wrap their minds about the ridiculously basic concept that no story they consume about a marginalized person should be taken as a blanket representation of their entire community?

It’s ridiculous. Gringos at some point came up with the idea that latinos are all naturally inclined to crime, so now I, a latina who loves heist movies, can’t write a latino character who’s a cool car thief. Gentiles created antisemitic propaganda claiming that the jews are all blood drinking monsters, so now jewish authors who love vampires can’t write jewish vampires. Straights made up the idea that lesbian relationships tend to be unhealthy, so now sapphics who are into Brontë-ish gothic romance don’t get to read this type of story with lesbian protagonists. I want to scream.

And at the end of the day it all boils down to how people see marginalized characters as Representation™ first and narrative tools created to tell good stories later, if at all. White/straight characters get to be evaluated on how entertaining and tridimensional they are, whereas minority characters get to be evaluated on how well they’d fit into an after school special. Fuck this shit.

64K notes

·

View notes

Text

imo the best way to interpret those “real people don’t do x” writing advice posts is “most people don’t do x, so if a character does x, it should be a distinguishing trait.” human behavior is infinitely varied; for any x, there are real people who do x. we can’t make absolute statements. we can, however, make probabilistic ones.

for example, most people don’t address each other by name in the middle of a casual conversation. if all your characters do that, your dialogue will sound stilted and unnatural. but if just one character does that, then it tells us something about that character.

164K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Mix Thoughts and Dialogue

During a bit of dialogue, it can be incredibly tempting to give your reader a glimpse of what the characters are thinking. This is a trap. Don’t do it.

Why?

Well, the best way to explain this is to just give you a quick example.

Mary laughed, her eyes sparkling. “Hey, do you remember that night with Jimmy and the cat?”

Ryan smiled, his mind drifting back over the long years of their friendship. That they would still be so close after all this time was truly a gift. Yet a part of him still asked ‘what if?’ What if they were meant to be something other than friends? Could that every happen or was he being greedy? Risking something beautiful for so little gain.

He shook his head, clearing his thoughts. Then he smiled and said, “Yeah, I still don’t know where he got it!”

Question: when you got to Ryan’s response, did you remember what Mary said or did you have to glance back up to jog your memory? If you glanced back up, then don’t feel bad! You are completely normal and that’s why this is a technique that you should use sparingly.

When we’re reading, our brains are constantly processing new information. It’s basically an ongoing memory game! If you’ve ever played one of those, then you know that it can be quite tricky to recall which picture is hiding under which card or what objects were on the now-hidden tray. However, we can always pick up the card or reveal the tray to remind ourselves of the answer. Similarly, we can always glanced back up the page and reread the previous line, but a story isn’t a game. Most writers want their audience to be fully immersed in the scene. Their eyes should travel down the page, following the flow of the words, never needing to look back at what was said three paragraphs ago.

You’re never going to be able to make your audience remember everything that you wrote. There are just too many words in the story. That’s why, when you’re writing dialogue, you want to keep all of the surrounding text related to the dialogue. Don’t let your characters go off on tangents like Ryan did because then your audience’s brain will switch to this new topic and forget the old one the same way that a verbal tangent will lead to someone asking, “Hey, wait, what were we talking about?”

I get the temptation to do the thought thing. It can give some really fun insight into a character. I will do it myself in early drafts. Then, upon rereading, I’ll realize that I switched focus from the dialogue and, as much as I like sharing my character’s thoughts, dialogue just isn’t the place to do it. If you’re including dialogue, the point is usually the interactions between the characters, not their deep, individual thoughts.

In this case of the above, Ryan’s thoughts needed to wait until after the conversation was over OR I should have introduced this topic earlier so that I could briefly hint at Ryan’s feelings with something like:

Mary laughed, the sound making Ryan's traitorous heart skip a beat. Then she asked, “Hey, do you remember that night with Jimmy and the cat?”

“Yeah, I still don’t know where he got it!” Ryan said, gazing at her with melancholy fondness. “Did he ever tell you?”

This is not to say that you can never do the thought thing. You can. Just be aware that it's dragging your audience away from the dialogue and they will likely forget the details of what was being discussed, making it a not-so-great techniquie.

The only time when I’d do that is when I want the character to forget the conversation, too. Then I can bring the character and the audience back to the discussion in a natural way.

I’ll also note that readers do remember things long after they happen. It’s just that what tends to stick are the big, important details (ex: Alim was murdered) or the things that get repeated constantly (ex: the suspect list that the detectives go over after every new clue). Dialogue tends to be largely forgettable as the point is rarely the specific words, which is why breaking a conversation is so jarring.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

i just saw a tiktok (<- cursed cursed site) that started out good, talking about how "show don't tell" is something you should keep in mind. It used the example of "instead of saying 'she opened the door', try 'her shaking hand twisted the doorknob, letting out a loud creak'".

And, yeah, if you're trying to convey the hesitance, fear, and eventual sucking-it-up that seems to be going on in the scene, that's great.

But.

The tiktok ended with, "see? Showing is ALWAYS better." And I just...

Friends & enemies, that's how you end up with that insufferable always-showing always-active YA writing style that does not know when to just shut up and say "she opened the door".

Because, yeah, I'll say it. Sometimes "she opened the door" IS better. Sometimes, the act of opening the door is literally just announcing a setting change, and you don't need to focus on it.

Show don't tell is about conveying important or relevant information, not about literally everything you're writing. You're allowed to say "she opened the door" & similar, and in fact, I encourage it in many scenarios.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lil’ Tip

I see two common formulas when a character is severely hurt

injured >> panic >> faint

or

injured >> hide it >> faint

While these two formulas are great, I am here to propose other things people do when they are in severe physical pain. pain to this degree throws a persons entire body out of wack, show it!

here are some other less commonly found things people do when they’re in severe pain:

firstly, repeat it after me, kids! not everyone faints when they’re in a ton of pain! some people wish they could faint

but they do tremble, convulse, or thrash uncontrollably (keep in mind, trembling and convulsing are something the body does of it’s own accord, thrashing is an action taken by the person)

hyper/hypoventilate

become nauseous

vomit (in severe cases)

hallucinate

lose sight (temporarily)

lose hearing (temporarily)

run a low-grade fever

run a high-grade fever (in severe cases)

become unaware of surroundings

develop a nosebleed

develop a migraine

sweat absolute bullets

feel free to add more in comments/reblogs!

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever I make a post about a technique that you can use to diversify your writing, I usually keep it pretty surface level. Describe the technique, give an example or two, and then leave it up to you to decide whether or not you want to use it in your own writing. However, my post on using relationship descriptors instead of pronouns generated some comments along the lines of “just use names” so I wanted to take a step back and explain why relationship descriptors work whereas things like “my blue eyed sibling” don’t.

To start, let me show you that this isn’t a “me” thing.

Prue Ramsay, leaning on her father's arm, was given in marriage. What, people said, could have been more fitting?

-Virginia Wolf To The Lighthouse

When Jane and Elizabeth were alone, the former, who had been cautious in her praise of Mr. Bingley before, expressed to her sister how very much she admired him.

-Jane Austin Pride and Prejudice

Frances pulled his hair heartily, and then went and seated herself on her husband’s knee

-Emily Bronte Wuthering Heights

“Of course it wouldn’t,” agreed Tom.

She turned to her husband.

“As if it mattered to you,” she said

- F. Scott Fitzgerald The Great Gatsby

I didn’t have these quotes at the ready. I just pulled up some famous works of literature and searched for relationships that I remembered being in the text, knowing that I’d find examples of relationship descriptors among the lauded pages of the classics.

How did I know that?

Because relationship descriptors are an extremely common way to refer to people even in non-literary conversations. For example, my boss is married and mentions his wife with relative frequency. However, I don’t think that I heard her name until I’d been working there for well over half a year. He just always called her “my wife”.

My wife and I went out for dinner last week.

My wife and I are hosting Thanksgiving.

And so on.

This is a thing that we do without thinking about it, in part because we don’t assume that everyone will remember our loved ones' names. Unless someone knows my brother personally, I’m probably just going to call him “my brother” when talking about him because that makes communication far more easy than expecting every person I know to remember my brother’s name.

We also do it because that’s just how we think of people. I’ve been known to say, “Did you call your brother?” when talking to my significant other. I could have used this individual’s name, but I’m looking at my SO, thinking of things in context of him, and just default to “your brother”.

Because this is a thing that we naturally do, it doesn’t feel odd when we see it in text. We barely even register it. It's really no different than using a person's name.

The same cannot be said for physical descriptors like “the blond” or “the older man”. We don’t typically use those in normal conversation. That doesn’t mean that physical descriptors should never be used, though. Even the greats used them:

I should think this a gull, but that the white-bearded fellow speaks it: knavery cannot, sure, hide himself in such reverence.

-Shakespeare Much Ado About Nothing

They just limited their use to discussions of total strangers or times when character A didn't yet know/had forgotten character B's name.

So, yeah, don’t be afraid to use relationship descriptors. If they sound natural in the line, then they likely are. There are definitely times when I use one and then replace it because I think it sounds awkward, but the same can be said of names! That’s actually when I tend to pull in a relationship descriptor. I read through a passage and think, “I use names too much here, it sounds off” and then I replace one instance of a name with a “his sister”, “her wife”, etc. and that usually fixes it.

#writing advice#pronoun trouble#pronoun troubles#writing tips#more in depth discussion of literature

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hard agree that those types of descriptors usually feel awkward and off, but they do have their place. Here's a quick rule of thumb for those who are scared to ever use these things because people tend to (rightfully) complain about them being overused: when you write a story, you should be framing things in the context of what the character(s) know/would think.

For example, if my brother walks in the door, I'm not going to think "There's my blue eyed sibling" I'm going to think "there's my brother" which is why, if I'm writing about siblings, it's totally fair to write:

Alexander glared at his brother

Because that's a reasonable way for Alexander to think of or refer to Michael. Think of it this way: no one would bat an eye if he said, "that's my brother" and pointed to Michael.

However, if Alexander walks into a room and sees a stranger, then physical descriptors make sense because he's only going to be able to think of that person in terms of what is visually apparent about said person. That's when a sentence like this makes sense:

Alexander stared across the room, trying to figure out what the blond haired man was doing.

As soon as Alexander learns this person's name or learns this person's relationship to something or someone important, then the visual descriptors stop being reasonable because he'd instead think things like "there's Maddy's brother" or "that's the guy who almost ran me over last week".

As long as you're always referring to characters in the way that other characters would refer to them, then your story should read fine. Focus on that and don't get overly concerned about avoiding physical descriptors.

Using Relationship Descriptors To Get Around Pronoun Trouble

Whenever you’re writing a scene where multiple characters use the same pronouns, things can get tricky. Is the ‘he’ in this sentence character A or character B? There are many writing tools that you can use to get around this, but I wanted to share one that I don’t see used very often: keeping focus by using relationship descriptors instead of names.

Allow me to demonstrate!

Alexander glared at Michael, then he grabbed his coat and stalked out of the room.

The ‘he’ in this sentence is ambiguous. It’s probably Alexander, but you can’t be sure. A way I get around this is to do this:

Alexander glared at his brother, then he grabbed his coat and stalked out of the room.

By replacing ‘Michael’ with ‘his brother’, you keep the sentence framed around Alexander. Everything is being described in relation to him, so you naturally assume that he’s the one doing the action.

Here’s another example:

Madeline ran across the room, throwing her arms around Sarah. Then she pulled back, wiping away her tears.

Verses

Madeline ran across the room, flinging herself into her girlfriend’s arms. The she pulled back, wiping away her tears.

I use this all the time when two characters with the same pronouns have to interact in some way. If they're just talking to each other, then I usually use other tools.

23 notes

·

View notes