#suspension of disbelief

Text

I'm normally happy to grant video game worldbuilding nearly unlimited suspension of disbelief, but some RPGs seem determined to make that difficult. Like, I'll be playing a game where human civilisation apparently consists exclusively of small fortified villages isolated from each other by vast stretches of trackless, monster-infested wilderness, with the villages' inhabitants rarely (if ever) venturing beyond the walls and non-village-dwellers having a life expectancy measured in minutes, and I'll think "well, clearly this is a gameplay abstraction, or possibly some sort of metaphor" – but then the game's plot seizes me by the shoulders and looks me in the eye and says "nothing you've just seen is a gameplay abstraction or a metaphor; here are multiple long-winded cutscenes and thousands of words of supplemental lore establishing that the narrative critically depends on the depicted setting being 100% literal", and I'll be like, all right, you know what? Fuck you. Where do they get their food? Who's minting the universally accepted currency? Why do they all have the same accent?

#gaming#video games#game design#worldbuilding#suspension of disbelief#death mention#food mention#swearing

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

OFMD fandom has me thinking about Protagonist Centered Morality, like, in general.

I feel like we only call it that when we think it's been handled wrong and are criticizing it, even though - let's be honest - we have all bought into some degree of protagonist centered morality in our favorite show. Like. It's the beating heart behind the very idea of a Mook - the faceless darkside minion that your heroes can destroy without any moral consequence for that action because who gives a shit? It's basically inescapable in every cop-show (or reskinned cop show like spn), chosen one story, action movie, revenge quest, underdog tale... we fucking love it when the universe agrees "yeah they earned that" and will generally just roll our eyes at people going "ok but you know your fictional murderers are doing bad things, right?"

Until we don't.

And, like, as an offshoot of this... 99% of the time, when you're criticizing a show for its protagonist centered morality, the most straightforward way to get your point across is complaining about whatever happened. "X did Y and then we're just supposed to forget about it?" Or "X is being such a hypocrite about Z!" And then someone else (real or hypothetical) pushes back with some point about how the story / other characters / etc. don't treat this as a problem and that kicks off the framing criticisms. But is it really about what they did?

People will object to the protagonist centered framing of actions they don't consider that serious, and be satisfied or unconcerned with the framing of actions they find borderline unforgivable. Protagonist centered morality can casually handwave (or seriously penalize) the whole spectrum of morally questionable actions from being a shit in high school to committing massive war crimes. Sometimes the primary complaint is that the protagonist already took a stance against this action, so now being fine with doing it themselves is hypocritical and out of character, and the problem with protagonist centered morality seems to be more that it's letting the OOC part slide.

The concept engages with genuine criticism of a characterization or character's actions as a shorthand, but the part it's actually complaining about is closer to feeling the narrative failed somewhere on a meta level to calibrate how much the audience should care about this event (and what level of in-universe caring would then satisfy).

It's not (at least usually) a fancy way of putting forward character crit of the good guys - most people who want to do that are just going to do so directly. If anything it has more in common with being upset at a story for breaking your Suspension of Disbelief (usually in the arena of character relationships).

#media#tropes#analysis#fandom culture#suspension of disbelief#protagonist centered morality#i'm mostly just rambling here after seeing lots of back and forth flame stuff just bounce entirely off the points being made#like you can't argue someone around to your pov on this by doubling down on how there's no issue until they make one#or defending your fave from perceived attacks. it's not *about* blorbo it's about the meta narrative#see: criticizing the fact the spn universe treats dean winchester's pov as divine law is not really deancrit#in fact my poor blorbo is actively denied character growth because he's fundamentally no allowed to be wrong#ladyluscinia

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having multiple A03 tabs open is like, “Ok is this the fic where the characters are siblings, the one where they’re fucking, the one where they got age regressed to toddlers, or the one where one of them owns a coffee shop and the other one’s a dragon?”

And it’s the same fandom so your brain’s just like, seamlessly bopping around from platonic to porn to preschooler and it’s like doing burpees for your synapses.

(Feel free to print this out to show your therapist if they ask whether you do any kind of brain training exercises.)

#fanfic as exercise#why isn’t that a tag#fanfic#ao3#fandom#fandom magic#suspension of disbelief#why does every fandom have a coffee shop au

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Until it breaks: Suspension of disbelief has limits

Nothing deals damage to suspension of disbelief like cold hard facts. Because once the analytical part of your brain kicks in, it's all over. All the Fridge Logic will unravel, and frankly, the enjoyment drains out the watching or reading experience.

Now, I picked this topic because of a recent Lupin III Part 6 episode I watched. Being one of the longest-running shows with endless material released over the course of decades, Lupin III has in general good writing. Or let's say it like this: Typically the authors nail the characters.

Yes, part 6 in general is a highly enjoyable show that can bank on the fact that our main characters - Lupin, Jigen, Fujiko, Goemon, and Zenigata - are well fleshed-out, recognizable characters that you are just gladly along for the ride with and the general fun factor of the show ensures that you merely experience the differing quality of episodes as minor ups and downs along the journey.

There are exceptions, though.

When it holds

Lupin III is basically revived as "parts," where each part could be considered a big season. I'm currently watching Part 4, and several episodes definitely have the quality of Fridge Logic - you might question things after the episode finishes, but you're basically okay with how things unfold while they still do.

One episode, hitting that slightly noir vibe, focuses on Inspector Zenigata, Lupin's eternal complement.

The show aired almost ten years ago, so forgive me for spoilers.

The basic plot of the episode "Until the Full Moon Wanes" revolves around every scoundrel in the world believing that the widow of a media mogul sits on a huge hidden fortune because her husband seeded the rumor before he died. The first climax of the episode seems to be convincing the world that this was indeed a lie - a cooperation between Lupin and Zenigata. In the denouement we learn that the fortune actually exists and the widow wanted potential thieves off her back, Lupin shows up to steal it and is finally thwarted by Zenigata.

The episode really revolves about human folly, with a media mogul rescuing a girl from sexual violence, taking her as his beloved wife, then completely scorning her when she cheats on him once - including marking her body. This theme of scorn beyond the grave and its somewhat noir vibe playing on human passion and the unreliability of love and character are enough to keep us entertained until we get our inevitable finale.

I'd say this one stretches suspension of disbelief but doesn't break it. Though it raises questions - even if she had a huge fortune hidden, wouldn't it be easier to own it, hire guards, and just enjoy it? Furthermore, how did Lupin and his gang intend to steal the fortune?It's gold. It weighs tons and tons. (And yes, it's enough gold to be considered the reserves of a country. Did the author not watch "Die Hard with a Vengeance"?) It's also stacked in the most stupid way possible to impress the audience. Once you start to think about it, the story unravels and falls apart. But I'd bet while it goes on with its (somewhat forced) twists and turns, you're willing to follow it.

When it breaks

There are, however, some episodes too stupid to live, and so far the unrivaled king of the trash heap is "The Jet-Black Diamond". I'll spoiler this one so you don't have to watch it.

So, some small wooden dolls are somehow supposed to lead to a treasure. But the story makes no sense, no matter which way you look at it.

The central theme behind the treasure hunt is supposedly a love story. A somehow Japanese woman in Brazil falls in love with a pirate who basically sacks her village but spares her. (Because seeing people die you spent your life with is conducive to romance. Maybe she had Stockholm Syndrome.) They know they have little time so they concoct a plan to hide some treasure and meet again. Which never happens because the pirate gets executed shortly after and she commits suicide.

This might make sense on the surface but just wait for the rest...

The clues they leave lead to a cashew tree with magical red glowing flowers that only blossoms every 75 years. The biological facts themselves are mindboggling - how does it benefit the damn tree to blossom only every 75 years? And how is it so exact over such a long period of time?? And why is everyone showing up at the right time to see it???

Breathe. Slow, deep breaths.

So this basically means they planned to meet again when they were around a hundred. Instead of, you know, like five years later.

Then... piracy in the Caribbean and around South America was a phenomenon largely limited to the 16th and 17th centuries, with stragglers hanging on until the 18th century. Steam vessels and larger national navies ended it for good in the 19th century. (To put it very roughly.) The episode itself can be assumed to be set in 2021 when Part 6 aired. So, are we to assume that old-fashioned piracy occurred in Brazil in the mid of the 20th century? The age of airplanes and nuclear bombs? (Piracy persists but is a rather local phenomenon in the world, relying on quick hit-and-run raids.)

What is the treasure, actually? Pepper. Some special pepper, that supposedly ended up making the village prosperous. This is probably an allusion to the times when pepper was still highly valuable, something which was maybe true up to the 17th century (as a little research shows).

What we really have here is an author shoe-horning a pirate story into Lupin III, and somehow trying to tie it to a love story and a living relative. (Instead of a long-lost pirate treasure.) But frankly, the whole thing fails over and over again. The finale is devoid of any logic. Even the dolls are somehow important because their patterns help identify the tree by its blossom patterns. The only tree blooming in that particular year, looking entirely magical and obvious BY ITSELF!!

(Also some young local thugs show up to gang up on the old lady and her company because everybody thinks about the ages old treasure all the time and so the arrival of a Japanese lady is clearly stirring up the area.)

To make the offense even worse, just when the story focuses on Fujiko being in the lead for quite a while, Lupin shows up as a drone projecting a hologram acting as Captain Exposition, stealing her thunder. They couldn't be arsed to write him in properly, but they couldn't leave him off-screen for five minutes or have somebody else have the spotlight. Wow, that was horrible writing altogether.

And here we have it - it qualifies as a story. It's tied together by a plot. Events happen, characters appear, and the same mixture of twists and turns and a lack of treasure at the end (for Lupin or Fujiko) appears, but it doesn't work. You could be forgiven for not knowing about the history of piracy, but the notion of a tree with such magical properties is not a twist to a story, it's a ridiculous device meant to introduce one twist too many to a poorly written story.

Because for some reason the author was so focused on thwarting the thieves so much he had to set up an entirely unbelievable gotcha even for Lupin standards. A show where people evade bullets near point blank range or where eating a steak can restore Lupin's blood loss within hours. It's actually quite the accomplishment!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I find the NOT GUILTY verdict in Ross’s trial to be the most implausible plot point in the entire series

• Going into the trial, Ross already had a reputation as a disrespectful hot head from Jim Carter’s trial.

• George had printed and circulated scandal sheets to sway the jury in favor of a GUILTY verdict.

• Demelza’s crazy father showed up to rant about Ross’s sinful lifestyle.

• Jud perjured himself on the stand when testifying against Ross. This could have been a boon for Ross, but all it did was make Jud an unreliable witness for either side.

• Although Dwight testified in Ross’s favor with a defense of mental instability, he was forced to admit that he was not an expert in that field, but merely a regular physician.

• The prosecution easily cast doubt upon the ship captain’s testimony that Ross had offered the survivors protection at Nampara by pointing out that Ross had not remained at the house for the duration of the night.

• During questioning, Ross was asked if he started the riot. The correct answer would have been a simple ‘No.’ Instead, he said he didn’t consider it a riot. (That’s not what they asked).

• They also asked Ross if he killed Matthew Sanson. The correct answer would have been to say ‘No,’ and explain that he had merely found Sanson, already dead, washed ashore. Instead, he said he was sorry for not killing Matthew.

Yet, despite all of this, the jury came away with a Not Guilty verdict. On what grounds, exactly? On the grounds that Ross was gentry? Perhaps, but weren't there plenty of gentry folk, including authority figures, that didn't like him?

Did they decide on a Not Guilty because Ross was a champion of the “little people?” Did Ross’s reputation as such reach all the way to Bodmin? If so, where was the evidence of this? Didn’t they pull the jury from residents closer to Bodmin, or did they pull from the whole of Cornwall?

Did they decide on a Not Guilty because he was pretty? I could see that.

Or did they decide on a Not Guilty because we couldn’t kill off our hero in the second season?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sorry babes but sometimes if you wanna enjoy the story you have to suspend your disbelief in the divine right of kings. Yes, I know that hereditary monarchy is fundamentally wrong and should not exist in real life but that particular lense of analysis is going to make you miserable if you're applying it to something like fucking Sailor Moon

#media literacy#suspension of disbelief#you're forcing a square peg into a round hole here#if you wanna do that go ahead but i will not be joining you#if you wanna see a proper deconstruction of the concept find another piece of media#it's not that hard

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

hualian modern au....conversation at the back of the bus

#tgcf#hua cheng#hualian#xie lian#art stuff#tgcf art#is that anything#once again i hate colouring sm#but this image was rlly vivid in my mind#part of this vague hualian au i have in my head#i did try to draw the seats in front of xie lian but i hated them sm so uh#suspension of disbelief#i swear i can actually colour but i'm just. lazy af.#one day when i'm happy enough with my art style i will start putting effort into painting...#my art

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so we come again, as so many discussions of fantasy inevitably do, to J. R. R. Tolkien. As a writer of fantasy, Tolkien hardly needs an introduction. Even before the success of the film adaptations of his work transformed him into a household name, he had won first the hearts of children with The Hobbit in 1937 and, some twenty years later, the hearts and minds of adult readers with The Lord of the Rings. But, like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, Tolkien thought deeply about his craft as a writer and creator, and it is largely by virtue of this thought that his art has achieved such timeless success. His 1939 lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” subsequently published as an essay in the 1964 book Tree and Leaf, is, as the editors of the recent authoritative edition of the essay put it, “Tolkien’s defining study of and the centre-point in his thinking about the genre [of fantasy], as well as being the theoretical basis for his fiction” (Flinger and Anderson 9). In this seminal work, he addresses all the points about the imagination raised by Coleridge and, following MacDonald, defends their application in the literary arts. We have already explored the other facets of Tolkien’s theory of fantasy as it contributes to the fantastic sublime, but I have saved his thoughts on the imagination for last, because I feel they serve as a linchpin for the fantastic sublime as a whole.

At first glance it would appear that Tolkien dispenses altogether with Coleridge’s whole tripartite scheme of primary imagination, secondary imagination, and fancy. Indeed, he takes issue with the desynonymization of imagination and fancy, though he does not single out Coleridge directly. A philologist of the highest order and sometime editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, Tolkien may be displaying false modesty when he ventures that, “[r]idiculous though it may be for one so ill-instructed to have an opinion on this critical matter, I venture to think the verbal distinction philologically inappropriate, and the analysis inaccurate” (OFS 59). Having deconstructed Coleridge’s framework, Tolkien then counters with his own, which is, by his own admission, just as arbitrary as Coleridge’s imagination/fancy divide.

The mental power of image-making is one thing, or aspect; and it should appropriately be called Imagination. . . The achievement of the expression, which gives (or seems to give) the inner consistency of reality, is indeed another thing, or aspect, needing another name: Art, the operative link between Imagination and the final result, Sub-creation. For my present purpose I require a word which shall embrace both the Sub-creative Art in itself and a quality of strangeness and wonder in the Expression. . . I propose, therefore, to arrogate to myself the powers of Humpty-Dumpty, and to use Fantasy for this purpose. (OFS 59-60)

But the advantage to this approach as both a theoretical model and a critical framework is that it separates out and clearly labels the writer’s mind (Imagination), the creative process itself (Art), and the finished product (Sub-creation). Fantasy is the end result.

Although Tolkien’s theory dispenses with Coleridge’s distinction between imagination and fancy, however, it preserves and even strengthens Coleridge’s assertions regarding the qualitative similarities between primary and secondary imagination. This isn’t immediately obvious, though the term “Sub-creation” gives us a telling hint. But to fully understand Tolkien’s debt to Coleridge, we must travel back to 1931, eight years before Tolkien delivered his lecture “On Fairy-Stories.” In that year, following a latenight conversation with his friend C. S. Lewis in which he defended the truths of Pagan myth even in a Christian world, he crystalized his thoughts into a poem called “Mythopoeia.” He quotes several lines from the poem in his lecture, and they are worth quoting here as well, for they cut to the heart of the similarity between primary and secondary imagination:

Man, Sub-creator, the refracted light

through whom is splintered from a single White

to many hues, and endlessly combined

in living shapes that move from mind to mind.

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build

Gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sowed the seed of dragons, 'twas our right. (Mythopoeia 61-8)

The metaphor of light that Tolkien employs here and elsewhere for the imaginative process is more vivid than Coleridge’s original distinction, but it nonetheless conveys exactly the same sense. In fact, the verbs Coleridge uses to describe the process of the secondary imagination—dissolves, diffuses, dissipates—suggest he was thinking along the same metaphorical lines. But Tolkien, usually so careful to avoid overt religious reference, here actually makes the religious and spiritual implications of the imagination more explicit than Coleridge’s “infinite I AM.” While, as we saw, George MacDonald is uncomfortable with ascribing to man the power of creation, Tolkien actually revels in man’s creative power. As in Coleridge, man’s creative power differs from that of God only in degree, hence the word “sub-creator.”

Tolkien’s vision of man as sub-creator leads him to openly challenge Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. Like MacDonald, he argues that a secondary world, or sub-creation, must be governed by a certain consistency if it is to hold an audience’s attention. To him, “this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed” (OFS 52). The true aim of fantasy, for Tolkien, is to draw the audience into a state of “Secondary Belief” similar to the sustained participative imagination argued for by MacDonald. The real change from Coleridge, and even MacDonald, here is that it places the burden of proof, so to speak, on the artist rather than the audience. When confronted with a good work of fantasy, the audience should not have to voluntarily suspend disbelief. Rather, “the story-maker proves a successful 'subcreator'. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is 'true': it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside” (OFS 52). I can’t help but think that Coleridge would have admired the symmetry of this idea of primary and secondary belief with his own idea of primary and secondary imagination, and would have conceded the point to Tolkien. And it is here that the fantastic sublime comes into full flower.

Tolkien’s language here reflects many of the writings on the sublime, from Longinus all the way up to present critics like Robert Doran. There is a certain inexorable, inevitable, magnetic pull that surrounds works of the sublime like a gravitational field. The sublime grabs hold of readers and doesn’t let them go. It turns their gaze upward and pushes their minds and spirits to see and experience things they could not have otherwise imagined. And at the same time, it makes audiences see themselves from those same heights, see their own mortality and frailty, and want to climb higher, be greater, do better. But while traditional conceptions of the sublime see this process as occurring in flashes, as lightning during a tumultuous storm, Tolkien insists we can have more than that. In his view, we can actually live in a world, if only for a little while, where the sublime is made manifest, where it is as real as rain.

And like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, he insists that these sublime worlds are not merely the playgrounds of children, but the kingdoms of all readers, of any age. He is in agreement with Coleridge about the educational value of fairy-stories. While

tepidly approving of fairy tales written specifically for children, he urges that “it may be better for them to read some things, especially fairy-stories, that are beyond their measure rather than short of it. Their books like their clothes should allow for growth, and their

books at any rate should encourage it.” But Tolkien is adamant that fantasy or fairy stories (he uses the terms more or less interchangeably) should be read by everyone. “If fairy-story as a kind is worth reading at all it is worthy to be written for and read by

adults,” he says, for “they will, of course, put more in and get more out than children can.” (OFS 58).

Tolkien delivered this lecture about two years after publishing The Hobbit, and just as he was beginning to work in earnest on The Lord of the Rings. While the former book is clearly a book for children, the latter effort “grew in the telling,” as he notes in the foreword to the second edition. Fortunately for the reading world, he practiced what he preached in “On Fairy-Stories.” But he did not build this world on sand. Tolkien scholars point to the medieval sources for Tolkien’s world, and rightly so, for these are indeed his secondary world’s bones and sinews. But its life-blood is, I would argue, the imaginative laws... that both create and sustain it. He took his own advice to heart and created a secondary world, Middle Earth, that has captivated and captured the imagination of millions of readers, drawing them into a state of secondary belief that, in some cases, lasts long past the reading of the books.

#Tolkien#Tolkien studies#J.R.R. Tolkien#the sublime#literary criticism#samuel taylor coleridge#suspension of disbelief#George MacDonald#the fantastic sublime#fantasy literature#fantasy genre#on fairy-stories#mythopoesis#mythopoeia#secondary belief#sub-creation

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

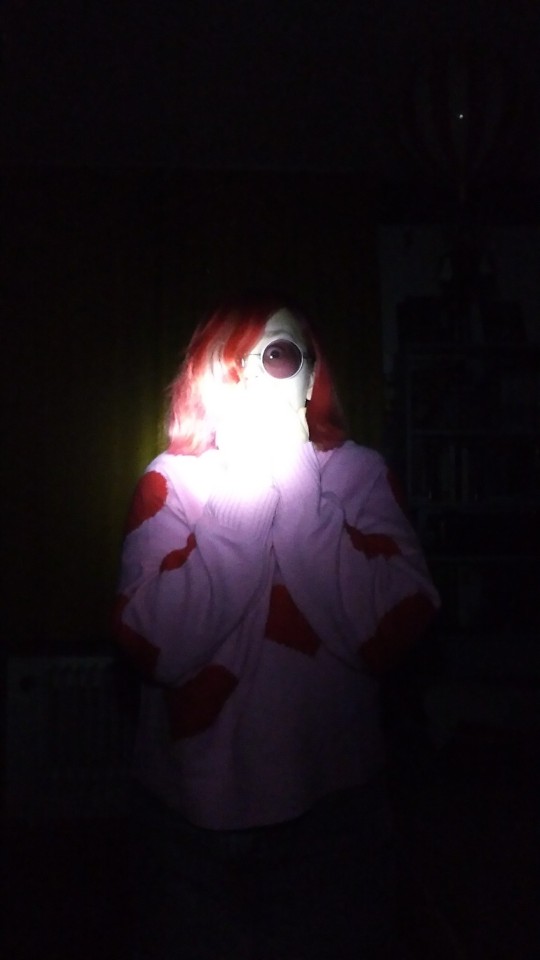

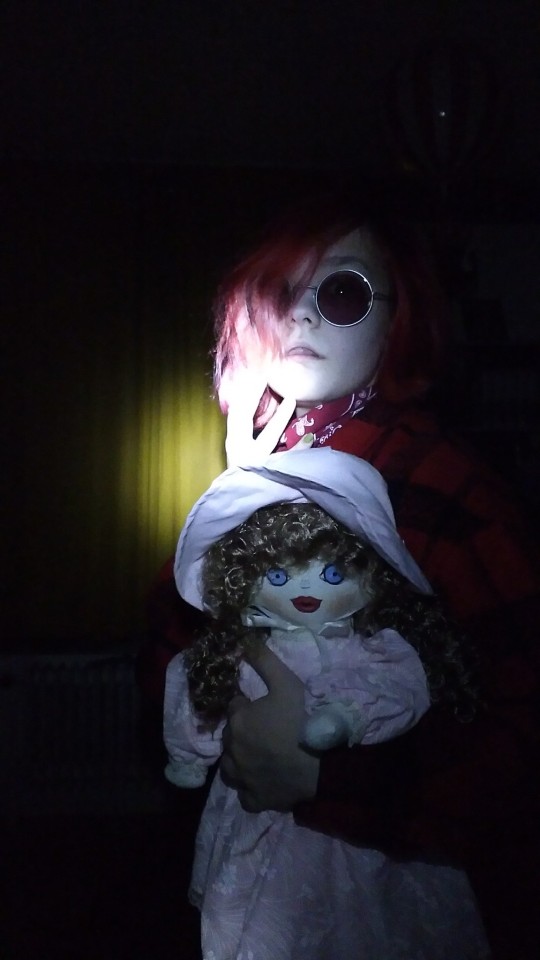

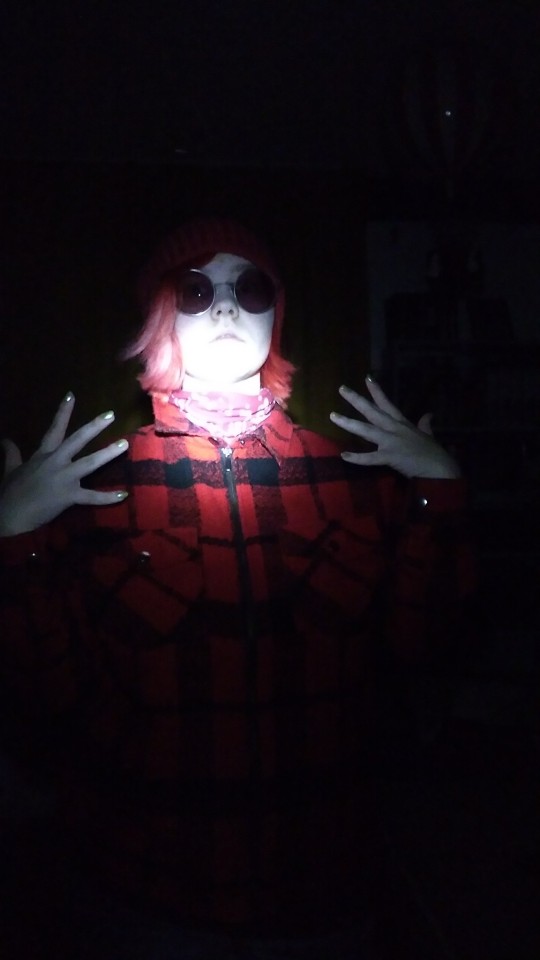

I'm just saying, given the opportunity the one-eyed mildly unhinged cryptid chick I'm playing in my next film would definitely be a Tumblr sexywoman.

(these are all from outfit tests)

#personal post#madphantom#maddie's face#traue deinen augen nicht#yes i know my eye is visible in one of these i didn't want to apply the make-up again#suspension of disbelief

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Casual reminder.

Critiquing/Analyzing the mechanics of how a story is told. This is cool.

Scouring a piece of media to contrive plot holes is not.

You have to remember that suspension of disbelief is an agreement between audience and creator. They make every effort to maintain the illusion, and you agree to find the most charitable explanation you can for any nitpick.

Generally the creator has failed on their end if despite your best efforts, you can't maintain it. You have failed when your engaging in unironic CinemaSins bullshit. When you are actively trying to resist being pulled into the immersion, as opposed to letting something fail/succeed to do so.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok y'all, we gotta talk about precision in language for a second, because I'm noticing a trend in book spaces (mostly but not exclusively reviewer spaces) that is irksome AF. Reviewers have this weird tendency to say variations on "I expect my suspension of disbelief to be maintained" before saying something that honestly has less to do with suspension of disbelief than actual poor writing or pacing.

I have two issues with variations on expecting your suspension of disbelief to be maintained.

First: We need to talk about what suspension of disbelief is and whose responsibility it is. To paraphrase Geoffrey Tennant (from the criminally underappreciated Slings and Arrows) paraphrasing Samuel Taylor Coleridge, drama and storytelling functionally IS the willing suspension of disbelief for the moment. The word "willing" tends to get dropped from the understanding of suspension of disbelief these days, which opens authors (and other creators, but I fucking hate broadband terms like "creator" so for the purposes of this post, we're talking authors) to holding the entireity of the responsibility for suspension of disbelief.

This is incalculably stupid and not how anything works.

Authors have the responsibility of creating worlds, characters, and narratives. That's pretty much it. They build the sandbox, and we as readers play in it. But here's the thing: If we agree to play in the sandbox, then we also agree that "willing" is part of the deal. That means that we as readers have to meet authors AT LEAST halfway, and honestly I think it's more like 3/4 of the way where suspension of disbelief is concerned. Authors aren't in your heads, and they aren't going to tailor a book directly to what you believe, so you have to be willing to suspend the disbelief. You as a reader have to do at least half of that work.

Now having said that, I'm not about to say that there aren't immersion-breaking things in books sometimes or that there is no such thing as a bad book; none of that is true. But there is something so cynical and frightened of looking dumb in assuming that if an author isn't doing 100% of the work to suspend YOUR disbelief, then the author is in the wrong that it actually takes my breath away. Take responsibility for your part in the act of reading.

Second: Don't bitch about a lack of suspension of disbelief when what you actually mean is that you have a very legitimate complaint about the pacing or the writing or an incongruous use of language or a deus ex machina that you didn't like. Get specific with the problem you have with a book, and be precise about the issue and how it impacts the narrative. Quality and reading experience don't necissarily line up. I have THOROUGHLY enjoyed reading objectively poor-quality books, and I have found objectively high-quality texts an absolutely hideous experience to read (see every time I tried to read To the Lighthouse).

Very often when people say "I expected my suspension of disbelief to be maintained," they're eliding the reading experience with their assessment of the textual quality. Stop doing that. Be precise.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A quarry? In Wales?

Oh no. These are the blighted wastelands of Ciceronicus XII!

Yes! Very dangerous!

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#my poor attempt at a joke#quarry#wales#cymru#bbc quarry#doctor who#the hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy#douglas adams#blake’s 7#Ciceronicus XII#unreality#suspension of disbelief#what#no context#wastelands

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'know how sometimes a TV show or movie will have something happen -- some random thing they try to milk for comedy -- and your entire suspension of disbelief shatters because you need to deal with this?

I just watched the dinner scene in Only Murders in the Building where Oliver Putnam's tooth falls out/is ripped out by the pork chop, and for the entire rest of the episode I was stuck on how HE NEEDS TO GO TO THE DOCTOR! (Or at least a dentist)

It's not normal for teeth to just fall out. It's especially not normal for them to fall out without any pain or discomfort. He had a heart attack a few episodes ago. This strange new symptom indicates that he has some sort of significant health issue which needs immediate attention.

For the entire ferry ride with him and Loretta Durkin I was completely at a loss for how they were just giggling or jesting about this. They're two grown adults, they should know this isn't normal.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

First off I want to say that your TOH criticals are a good read. It puts my grievances with the show in words I can only ever feel and brings a bit of closure in the "whys" of those grievances. That being said I haven't gone through all of them, so feel free to direct me if you've already made comments about my upcoming ask elsewhere.

Regarding Elsewhere and Elsewhen, what do you think of the show using time-travel as a plot device only once and not returning to it? The way they used it, Luz might-or-might-not be a catalyst for what wounded up happening and we might-or-might-not be watching a show that's been on an alternate timeline. I would think that's a pretty big deal but the show just moves on from it; Luz might as well have given Belos that glyph in the present since time-travel is never dwelled on again.

I think it would have helped make a more solid finale if they used time-travel again because of the possibilities, where ALL the characters could benefit from it, instead of whatever the intention of 3 characters babysitting The Collector was.

So first, thank you for the kind words!

Secondly... No. Just no. Time travel is REALLY tricky to use in a narratively fulfilling way. This is because you run the risk of creating a paradox or having it not matter OR BOTH like TOH since the literal only real change from Luz entering feels to be the saving of the journal. The Collector otherwise was about to teach him other magic, we never get an instance where him learning the light glyph is important and he literally already killed one person doing this scheme of his: He would have found another. Literally the only thing that really changes is the EXACT when of the Collector and Belos meeting, which hardly matters with how much time Belos had, and the journal which... only brought about Luz and changes literally nothing else if lost so... Yeah, even if it's a stable timeloop, it's a really dumb one that still has the paradox of Luz needing to show up to save the journal.

And if this feels overly critical... Blame the trope. Time Travel plots usually are ALL about the consequences. Going back in time inherently begs that question for the audience. There's a reason why a lot of time travel stories end with the lesson of DON'T FUCK WITH THE TIMELINE and restore all to status quote with the main character having not changed anything. Or it introduces multiple timelines like Dragonball Z to allow a series to eat its cake and have it too.

So what is my advice for time travel plots?... Lean into the fun of it. See, a lot of my issues with the specifics of the time travel element of Elsewhere Elsewhen are nitpicks. The larger issue for the episode is that it's just the WORST version of Lilith, Lilith and Luz are at their absolute dumbest, arguably at least as dumb for Luz as she was in the SECOND EPISODE. And this is the second episode of the second half of the second season. I think it's reasonable to ask for a little better from Luz at this point.

But the time travel itself is mostly just... There. They don't do ANYTHING with it in the episode, between like two good jokes that are mostly just portal jokes frankly more than time travel episodes except for a little tweak in flavor. The Isles we're shown is incredibly boring. What they do there is boring. Philip is EXCESSIVELY boring... So what am I supposed to focus on?

So I focus on the mechanics of the plot. And how stupid they are. And how literally they seem to reclassify how the portals work 3+ times because they could stick their heads in and out but that doesn't constitute it moving because now it would inherently be in the same place twice, they found the portals because they were in the sand but now if that sand gets moved by the tide, it'll make the portal disappear? Couldn't they just wait until morning? Or is there a timer on them? How do they know when the portals first showed up? For that matter, why the fuck does a device that is likely most tracking magical anomalies need Titan's Blood to detect an anomaly as strong as TIME MAGIC which doesn't seem to have been developed yet in the Isles?

And yeah, if that sounds like nitpicks... You're right. But you nitpick when Suspension of Disbelief is broken and the most common way it breaks? Boredom. Sheer fucking boredom. If what is happening on screen that you're supposed to just mentally tank as "Yeah, that sounds fine" even when it might be a bit dumb logically is just boring... Why tank it? Why not question it when in the questioning, you might enjoy yourself more than simply accepting what the show is doing.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi is the MASTERCLASS at how to fuck up Suspension of Disbelief seven ways to Sunday because everything sucks and nothing you do matters, but at least that was part of the movie's point. With TOH... You don't get anything for watching it. Satisfying reunions of friends? Nah. Amity and Willow never have a satisfying friendship. A grand tale about a human rising up with her found family and her hard won magical powers? Frankly, how much do King and Eda actually do in the finale? Like they're there but swap them with literally anyone else (like how Raine is just randomly right by Luz's side effectively too for this finale) and nothing really changes because their involvement isn't important. Luz's magic isn't earned nor even HERS. Want a satisfying conclusion to Palisman? Nope because Stringbean makes no sense. Want satisfying character arcs? Look elsewhere because we're not going to look into the hardships that come about with those changes, despite both Hunter and Amity having VERY clear reasons why this change would be potentially DANGEROUS for them.

Elsewhere Elsewhen is just of a kind that way. Outside of its first five minutes, and the two minutes with Dell... What are you getting out of this episode? Comic relief Eda which is always the worst comedy in the show and this is the worst of it as Eda is bonked with the stupid stick like Lilith and Luz? Lilith and Luz interacting with a SINGLE person in the past who doesn't even reflect the culture of the Isles back then so he could have been just a homeless person in the present if not for the twist it's Belos? For the lack of puzzle? For the strict anti-climax of the threat because Luz was lucky enough to poke her head into the right portal to give her the solution at the end?

And that episode is one of the most important plot points of the SERIES. It is one of the only plot points that is actually brought back and kept consistent and one of the only, ONLY times something happens and it actually affects Luz, even if it's delayed. This is the episode that revealed that Belos and Philip were the same person. It is critical to the series overall.

And most of it is just a BORING waste of time. While doing TIME TRAVEL. Instead, their priorities in this episode were really lazy 'subtle' storytelling to say the covens are bad and to allude to the twist at the end of its own episode and... Not fucking much else.

And why should that be surprising? We never get a proper idea of what the Isles and its people are like because we don't spend real time with them (besides them just being humans), it's contradicted all the time, etc. like that and that is their MAIN setting and time period. Is it really that surprising that the Isles of the past is just a utopia to these writers? Or that they literally have to ignore the conversations they themselves wrote for fish out of water jokes when the witches go to the human realm?

But these aren't concepts in a professional work you can half ass. You have to actually give a damn about a trip to a new universe or time period for the episode to not reel rote or boring or the like.

And, well, I'd love to see the timeline where the writers really cared about a lot more of TOH than they seemed to have.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're not getting 'out'

AKA Miles Sucks 2/3

Miles Bron may not be the complicated genius, master manipulator that you expect, but he certainly does his fair share of manipulating.

This is one of three moments I wanted to zoom in on

When Lionel hears that Miles has powered his island with the volatile fuel Klear, despite Lionel's many warnings and pleas for more safety tests, Lionel tries to give up. "I'm out," he says. "I'm done." He gives the ominous prediction, "This is reckless. And you're gonna get somebody killed."

This is, of course, a handy clue to the audience: Klear is not everything Miles makes it out to be. But it's also an opportunity to show us 1) a Disruptor at a breaking point and 2) how Miles reacts to someone trying to pull away.

Miles comes up with a hand on the shoulder and a "bro" on his lips. Literally, "Bro, you're not getting 'out'."

He tells Lionel, "It's already happening." The Sunk-Cost Fallacy. In for a penny, in for a pound, a phrase that was featured in the climax of Knives Out.

Then he gives him a little bro-squeeze and says "I love you." Reinforcing their bond in an effort to keep him tied down. I didn't say it was masterful, but it sure works.

And Miles doesn't even wait a second before trying to change the subject to something lighter. "Come on, let's … Let's eat!"

However, this time, the camera doesn't move with Miles. It lingers on Lionel's face. He's still troubled. But he sighs slightly, already knowing he's given in.

#glass onion#glass onion 2022#glass onion spoilers#miles bron#lionel toussaint#i post#i speak#i gif#badly but hey i did it#i ramble in the tags#man when i first watched this#that#i love you#set alarm bells ringing in my head#i had a whole paragraph about#suspension of disbelief#and the unspoken agreement between writers and viewers#about materials like flux capacitors and vibranium#but we all know that already right

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Why do people write fic where Blitzwing speaks German??? The language doesn't exist on Cybertron!" And apparently neither does the square-cubed law.

#i can suspend my disbelief if blitzwing gets to call bee hummelchen#transformers#transformers animated#blitzwing#blitzbee#maccadam#suspension of disbelief

52 notes

·

View notes