Text

i just don't think people should even be allowed to discuss whether wake is a good mom or a bad mom when there are literally people in the fandom calling john a good dad. i absolutely do not want to hear it

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

necromancy-cavalierhood, masculinity, chivalry, and imperialism in the locked tomb: or, the cavalier gender essay.

you may have seen an earlier version of this essay do the rounds, from an ask i answered last august – whilst the argument seemingly gained significant traction and i stand by the majority of the claims i made in the original piece, i wanted to write an “updated,” clearer and more thorough version, to cover some ground that i left uncovered in the original and to clear up a few ambiguities – as well as to just, like, write the whole thing out in a well-planned, comprehensible format, rather than as an answer to an ask that i wrote in less than 24 hours, most of which was done in one go, and i absolutely did not expect to get the kind of attention (and subsequent assumed authority) that it did.

in this reading, i’m not particularly interested in making claims about how being a necromancer or a cavalier “is” a gender – i more want to argue that a framework which understands gender as a social relation forged as a means of cementing imperialism is one that might help us make sense of the necromancer-cavalier dynamic as muir renders it, both as socially stratified positions within imperial society and as agents of imperialism in relation to the external world. in short, john created a world that aligned with his values – ie. what is now colloquially termed a ‘no homophobia’ world, where queer relationships hold the same social currency as heterosexual ones, but also one designed around the advancement of his imperialist vision. this doesn’t quite make sense, just on a base logical level, because the gender binary enshrined in western imperialist hegemony and heterosexuality each are tools of imperialism, and their removal from the equation should have caused social collapse around gender, sexuality, and imperialism alike – why didn’t it?

my hot take is that an abstraction of the mechanisms of gender that make these imperialist social formations possible onto necromantic hegemony wherein necromancy is the thing that ‘powers’ the empire, and the simultaneous underclassing of cavaliers and need for their absorption into the imperial fold (as protectors of necromancers, as part of the body of militia, and eventually as the key to lyctorhood), is what makes john’s imperialism a) possible in-universe, and b) meaningful to us, as an audience engaging with a text that pushes us to think about the entanglement of imperialism and queerness and lesbian masculinity in particular.

because this is inevitably going to get ridiculously long, i’m dividing this up into sub-sections, which will be as follows:

how gender as we receive it functions in-universe

how the social relations of gender are abstracted onto necromantic hegemony

what are the expected gender norms and what does deviation from those norms look like?

cavalierhood, masculinity, chivalry, and imperialism

conclusion

anyway. let’s get into it.

(nb. since i am arguing for a reading of cavalierhood and necromancy/the state of being a necromancer each as functionally genders, it can get a little confusing where i refer to ‘gender’ to mean what we as readers make of it, ie. the binarised man-woman social formation that exists alongside the socially enforced model of sexual dimorphism under western hegemony. when i mean this, i have tried to caveat it as ‘gender as we receive it,’ or something similar, but since doing this every time would break up the flow of the piece, assume that i use ‘gender’ to refer to our understanding of it unless it is clear that i am using it in a different way. cheers.)

(nb. the second – i use a lot of “we,” “us,” type language to refer to the audience approaching the text with a preexisting set of contemporary values, and often what i mean by these contemporary values is the set of hegemonic social relations making up the system of gender within which we are all situated. obviously ‘we’ do not always function as mouthpieces for this system, and i would imagine the type of audience for this material is not the type that’s going to be arguing in favour of, like, rigid gender roles and so on, but i use this as a shorthand for the hegemonic body that’s clearly shaping what muir does. in practice, obviously a lot of us are approaching this from positions of marginalised genders + sexualities and racialised and/or colonised subject positions that heavily alter our perspective, so take my use of the plural second person pronoun with a grain of salt – i really just needed a shorthand so this essay didn’t get any more unnecessarily verbose than it already is.)

(nb. the third – for clarity/transparency of position i am a white tme butch lesbian.)

how gender as we receive it functions in-universe

as stated in the original post, a lot of this section will read like stating the obvious – ie. gender as we receive it exists in-universe because the characters have genders – but it’s necessary groundwork to get to where i’m going with all this. there are a significant number of points in-text that we can look to to extrapolate some sense of how this society is thinking about gender, gender norms, relationships, and so on:

the fact that we receive characters through gideon’s close third person perspective rather than an omniscient narrator, and every character we meet has a gender that’s seemingly legible and identifiable on sight (ie. we meet cytherea, she is a woman, we meet the twins, they are women, we meet babs, he is a man, and so on), suggests that there is some sense of what constitutes a shared social understanding of what ‘makes’ someone a man or a woman that we receive filtered through gideon’s perspective.

these values do not appear to align very clearly with contemporary gender models (those being, to be incredibly reductive about it, ‘womanhood’ in the abstract is the closest a person can get to a white cisgender performance of femininity; ‘manhood’ in the abstract is the closest a person can get to a white cisgender performance of masculinity. of course this is not what gender is, but i am referring to what has social currency within hegemonic spheres.) the clearest illustration of this is that cytherea is able to identify gideon as a woman, but when she first meets harrow, she calls her ‘lady or lord of the ninth,’ implying a difficulty in matching harrow’s gender performance – whatever that may be – to conventional expectations. i’ll talk about cytherea in more depth later, but what matters here is that she as a lyctor is imbued with something like an authoritative relationship to gender, acting as an arbiter of ‘correct’ gender performances. gideon – butch, has a name that cytherea would have been able to identify as masculine even when the rest of the cast wouldn’t have been able to do so – falls into a performance of womanhood that cytherea is able to identify, and harrow – whilst hardly uncomplicatedly feminine, not necessarily what we as an audience would consider ‘more’ gender nonconforming than gideon – does not. why is that?

(i think, fwiw, the straightforward answer to why harrow’s gender in particular is so all over the place lies in the relationship that she has to thinking of herself as two hundred people at once, but this isn’t a harrow character study, this is an examination of gender as that social world receives it.)

in short, nonconformity to traditional gender categories – as we see in gideon and several other characters, including isaac, babs, coronabeth – doesn’t seem to be socially punished. similarly, the absence of a patriarchal social structure means the absence of a world where these traditional categories make sense. whatever it is that ‘makes’ a man or a woman or a nonbinary person within the imperial system, it does not directly translate to how we as contemporary audience might understand it.

whilst i don’t think the canaan house priest who is referred to with they/them pronouns is a huge deal regarding how muir does gender, i think it’s noteworthy that the language used to identify (categorise, taxonomise) their gender situation uses a binarist framework – ‘They might have been a woman and might have been a man and might have been neither.’ (gtn ch 8). if we are to assume that this priest is nonbinary, the means by which a nonbinary gender is made legible in the text is via reference to the gender binary, much like how contemporary liberal models of gender often envision a gender ‘trinary,’ or imagine nonbinary genders only in relation to how they are positioned alongside and/or outside of binary ones.

it’s plausible that the models of anatomy and reproduction used in the imperial society deviate from the sexual dimorphism that necessitates the gender binary, though i can’t find anything that would suggest this. in relation to reproduction in harrow the ninth, ortus is referred to as the only available source of ‘XY chromosomes,’ meant to establish him as the only person on the ninth who, to be crass, could impregnate harrow; i don’t know if we could get all that much out of this line besides a possible case to be made for there being something of an extant understanding of transness that informs how bodies are talked about with arguably degendered language (otherwise, i imagine it would have just said he was a man?). which aligns pretty well with the rest of the gendered values we see – transness is visibilised, possible, probably ‘accepted’ by some definition, but still confined to a framework steeped in imperialism.

obvious point and somewhat related to the one above, but since reproduction is still a politically charged matter tasked with continuing each house’s line of necromantic scions, and is imbued with the necessary imperialist resonances that come with this practice via eg. the eugenics practices of the seventh house or the notion of ‘resurrection purity,’ but reproduction is also not something that can be easily incorporated into an entirely ‘no-homophobia’ social formation since eg. a marriage market would obviously prioritise couples that can reproduce together and create social formations around the fact (ie. heteropatriarchy), we get the whole handwavey explanation of ‘womb vat tech,’ which presumably makes reproduction possible within any relationship. lazy as hell but i can’t fault her because it’s better than just being like ‘why does this society that’s very concerned with reproduction not have a hierarchy akin to heteropatriarchy? Ehhhhhhhhhhhh dw :)’.

in essence, the means by which our contemporary understanding of gender is rendered in-text is broadly through the prism of what i would estimate john’s values to be – a sense of manhood and womanhood as ontologically extant but not at all strictly defined by traditional western gender roles or heteropatiarchal forces, and transness and/or the state of being nonbinary, along with similar such peripheralised gender formations, legible only within this model. (it’s not clear in-text whether john, as a māori character, has a relationship to gender + sexuality shaped by the fact of his being an Indigenous islander, though i imagine he must to some extent; for clarity, i am assuming that his position as an imperialist takes primacy – after all, this is about the social formations that he needs to create – but i think it’s a necessary caveat when considering his position amidst All This.) it’s a very laissez-faire understanding of conventional gender in a society that no longer has a use for it because it did away with heterosexual hegemony, but still needs the social conditions that gender and heteropatriarchy create, and has to look elsewhere so as to synthesise them. which leads me to –

how the social relations of gender are abstracted onto necromantic hegemony

if we want to start really digging into the meat of how muir is asking us to think about gender, it’s necessary to look for ways in which our contemporary understanding of gender and colonial patriarchy can be mapped onto social relations present in the books, and i think that the clear answer to this is the hegemonic power invested in necromancy. put simply, necromancy is the force that propels the empire and the means by which its expansionism becomes possible in the first place; it very much is a fascist death cult, in that the fascism intrinsic to imperialism in its highest stages is realised through necromantic practices; the flipping of planets, of course, and the glimpses we get of warfare between the cohort and the territories that the empire occupies strongly suggests that necromancy is the weapon by which warfare is enacted.

Harrowhark said, “The Second House is famed for something similar, in reverse. The Second necromancer’s gift is to drain her dying foes to strengthen and augment her cavalier—”

“Rad—”

“It’s said they all die screaming,” said Harrow. (gtn ch 20)

the suggestion here of course being that cohort tactics rely on necromancy not only at the macro-level (ie. the flipping of planets and the structuring of the imperial social formation) but also at the micro-level of on-the-ground warfare. the point is, the state of being a necromancer is subsequently invested with a level of material hegemonic power that we might read as akin to patriarchal gender constructions. for example, the structuring of the nine houses around the need for a necromantic scion (to the point where eg. coronabeth has to pretend that she is a necromancer) takes on formations similar to those which we would receive as designed to reify patriarchy.

“The Reverend Daughter Harrowhark Nonagesimus ought to have been the 311th Reverend Mother of her line. She was the eighty-seventh Nona of her House; she was the first Harrowhark. She was named for her father, who was named for his mother, who was named for some unsmiling extramural penitent sworn into the silent marriage bed of the Locked Tomb. This had been common. Drearburh had never practiced Resurrection purity. Their only aim was to keep the necromantic lineage of the tomb-keepers unbroken. Now all its remnant blood was Harrow; she was the last necromancer, and the last of her line left alive.” (htn ch 3)

the inheritance practices of the ninth house here provide just one example of how the sorts of practices that would typically be employed in colonial noble households to preserve patriarchal power are mapped onto necromancy pretty much one-for-one. you could make a case for the ninth being somewhat exceptional, its priorities being the preservation of the ‘tombkeeper line’ descending from anastasia where the other houses seem more invested in merely providing a necromantic heir presumably blood-related to their predecessors (sixth house potentially excepted, since the position of master warden seems to be elective, but the sixth are outliers for various reasons anyway), but i think the fact that the very premise of gtn rests on the assumed provision of said necromantic heir in every house is enough to tell us that these social structures designed to preserve and hegemonise necromancy are very much in place. as noted above, this naturally segues into a eugenicist practice (most notable in the seventh house) endemic to imperialist fascism, oriented around the preservation of a necromantic bloodline and the augmentation of an individual’s necromantic power.

alongside this comes cavalierhood both as necessarily supplementary to necromancy and as a subjugated mode; in other words, an axis of oppression strictly within the confines of the imperial system alongside (and in tandem with) its function as a method of subjugation outside of the imperial system, ie. towards those the empire colonises. where this hierarchy of power becomes clearest is in its orientation towards lyctorhood, ie. the culmination of the necromancer-cavalier dynamic, wherein the cavalier is absorbed by the necromancer and becomes at once integral to the creation of ‘lyctor’ as a state of necromancy at its apex (‘the queenhood of my power,’ quoth cytherea) and entirely stripped of agency, selfhood, etc. once again i’ll do cytherea in more depth later in this essay, but within this setup, lyctorhood then functions as a hegemony such that it makes sense to read cytherea as something of an arbiter around gender, herself not only having taken on the social power of which necromancy is hypothetically capable but now imbued with the ability to regenerate and reinstitute the creation of these social dynamics, ie. through gideon.

it’s through this setup that i think a case can be made for the necromancer-cavalier dynamic as a social force to be elucidated within a gendered framework. if gender, even on this abstracted level, exists (as, again, a social force) within the world of tlt, it logically follows that there must be a set of norms and a set of behaviours that constitute deviation from these norms. which! brings! me! to!

what are the expected gender norms and what does deviation from those norms look like?

i think there’s a strong case to be made for the set of codifications of behaviour around the necromancer-cavalier dynamic (which we receive primarily via the values that gideon internalises throughout gtn) to be products of the culture of the nine houses that of course developed around the need for the dynamic in the first place; and i think a good place to look for a sense of this is via what we can extrapolate about mercy and cristabel’s relationship vs that of cytherea and loveday. some measure of this argument does involve a bit of speculation and is not technically grounded in firm, unambiguous canon, but i think i can make a fairly good case for it anyway.

so, again, this is a little pepe silvia of me, but i think we have a few factors in play wrt the mercy/cristabel-cytherea/loveday dynamic of sorts that all work together to tell us something about the form these gender performances took as they became culturally reified.

that mercy and cristabel founded the eighth house and each were part of god’s initial set of resurrections, strongly suggesting that their necromancer-cavalier relationship developed relative to the needs and strictures of lyctorhood as its process was gradually elucidated at canaan house, but not in relation to the set of cultural demands at play in the houses themselves; in contrast, we are told in cytherea’s funeral scene that she and loveday came to canaan house after having grown up on the seventh, seemingly several generations after the initial set of resurrections with enough time having passed for a cultural sedimentation around the necromancer-cavalier dynamic to have taken place and presumably exerted its force on their relationship.

in other words, we can read mercy and cristabel as somewhat ‘organic,’ less burdened by heavily gendered demands, than cytherea and loveday, around whom i would argue there is a gargantuan amount of narrative pressure being exerted genderwise. mercy and cristabel, as narrative focal points, seem predominantly concerned with the devotional-to-sacrificial side of cavalierhood (in relation to religious practice), where cytherea and loveday are far more the focal point of chivalric-type gendered tensions.

on that note, we can even see mercy/cristabel as a relationship oriented directly, immediately, intentionally towards lyctorhood, and cytherea/loveday as subject to more diffuse cultural demands, affected by but not immediately and consciously oriented towards lyctorhood from the first. we get a more holistic glimpse of necromancer-cavalierhood as it manifests outside of the canaan house bubble through the latter.

to get more specific i would argue that cytherea and loveday’s relationship functions as the prototype for the model that we later see cytherea imposing on gideon, ie. that of a butch/femme-type performance of chivalry, and i think reading loveday as having been a butch woman is like, the most plausible interpretation around her whole Situation. on the flipside, i can’t see a strong case to be made for gendered tensions being at play with mercy and cristabel, who as i said seem far more concerned with sacrifice and devotion and their limits.

this isn’t to say that cristabel can’t have some kind of ‘interesting’ gender thing going on – she might well be butch, she might well be what we would receive as gender nonconforming in any other manner, etc., or even to strictly claim that loveday was, like, definitely butch or masc or w/e beyond all shadow of a doubt – but that from what we’ve seen of mercy + cristabel + cytherea + loveday, the narrative is only honing in on the gendering of the latter two.

necessary caveat that some other early lyctors were of course entering into necromancer-cavalier dynamics shaped by having grown up in the houses themselves (eg. cyrus and valancy) without necessarily replicating the dynamic we see present in the seventh house lot, but much like how not every cavalier we meet has to be a butch for the narrative to still be clearly preoccupied with what cavalierhood does with butchness, i think focusing on the necromancer-cavalier pair who are clearly trying to tell us something about gender (ie. cytherea/loveday, rather than like, cyrus/valancy) makes the most sense on a metanarrative level. anyway

that cristabel and loveday are not oppositional, exactly, but played off against one another a little. augustine hates cristabel for cosmic, immense reasons, and we can’t really get a read on why he hates loveday, but it seems deeply … pedestrian? which is a little funny. loveday is the invisibilised driving force behind gideon the ninth, in that she is what incentivises cytherea’s actions; cristabel is the invisibilised driving force behind harrow the ninth, both in how she incentivises mercy and in how the relationship between augustine & mercy & john is functionally lynchpinned by her. both gtn and htn hone in on descriptions of cytherea and mercy’s eyes (loveday and cristabel’s eyes, let’s remember) in particular, as sites where the violent act that necessitates lyctorhood is made unavoidable, and as a reminder of the continued narrative presence of loveday and cristabel that i just outlined. most potently, where we learn that cristabel was ‘a total delight, effervescent,’ etc., our main insight into loveday’s personality is that she seemingly antagonised john + augustine + mercy for reasons unknown, and ‘looked like she wanted every one of [them] beaten to death’ upon meeting them, lmao. aside from the Opposite Personality setup happening here, the latter in particular to me implies a relationship to cavalierhood almost entirely removed from devotion to john and focused entirely on devotion to cytherea, where cristabel’s whole situation seems to have been that devotion to john and devotion to mercy and love for mercy were all so inextricable and coterminous that her killing herself so that mercy could achieve lyctorhood was not only logically possible, but in fact logically necessary.

the point i’m getting at with all that is that cristabel and loveday represent something of a horseshoe theory of lyctorhood, where these seemingly oppositional motivations and characters and relationships to their necromancers in relation to their devotion (or lack thereof) to john eventually circle round to lead to the same result. they’re two separate-yet-inseparable branches of cavalierhood, and the cytherea-loveday branch is the Gender Branch. i swear to god i am going somewhere with all this.

that of all the early cavaliers, cristabel and loveday are the two with whom gideon is brought into the most narrative contact; cristabel via the fact that the two of them are very much paralleled both in their own right and via the mercymorn-harrow parallel at play during harrow the ninth, and loveday via everything that goes down with cytherea and gideon necessarily drawing the two into one another’s orbit. given that by the end of gideon the ninth, gideon comes to take on something akin to a ‘perfected’ or complete performance of cavalierhood necessary to the completion of her corruption arc, it’s fair to say that in having cristabel and loveday be the two figures through which this performance is realised, the narrative asks us to regard cristabel and loveday as characters set up to tell us something about cavalierhood as a state. as argued above: cristabel is the emotive, loveday is the cultural.

where that incredibly long-winded trajectory ends up is that i think we can take cytherea and loveday to signify the culturally idealised model of the necromancer-cavalier relationship within the nine houses. whether or not their relationship constituted a ‘perfect,’ if you will, performance of necromancer-cavalierhood is a) unclear and b) irrelevant – within this theory, loveday does still only represent one side of the ‘complete’ performance of cavalierhood that gideon comes to internalise – but for the purpose of this section of the essay, where we’re looking to break down what the cultural baggage of necromancer-cavalierhood might be, i think there’s scope to argue for those two as a model of it.

from here, i would point to the various clues we have about the gendered nature of cytherea and loveday’s relationship, and how that maps onto how we receive cavalierhood:

that cytherea as we receive her in gt9 is a femme embarking on a predatory and fetishistic seduction of a butch, and conducting this seduction specifically along a line that fetishises gideon’s masculinity

that this seduction is at the same time a process of ‘teaching’ gideon cavalierhood from cytherea’s own vantage point of lyctor, ie. an arbiter and reproducer of gender, thus implying a continuum between the gendering acted out between cytherea and gideon on a sexual level and that acted out on a necromancer-cavalier level – ie. gideon as fetishised butch and as subjugated cavalier are one and the same

that cytherea is a femme and her femmehood is necessary to her relationship to cavaliers to me strongly implies that loveday was a butch

various other context clues wrt loveday and gender – the name isn’t exactly masculine, but it’s surnamey to the point of literally being used in-text as a surname (‘cytherea loveday’); ‘knight of rhodes’; the seemingly bristly, stonewally personality that doesn’t necessarily signify ‘masculinity’ per se, but like, it can – these factors alongside cytherea’s whole Deal with gender and cavalier fetishism and femmehood + the pre-existing lesbian fixation on butch chivalry is enough to make a reasonable case for her having been a butch

that cytherea and loveday’s whole deal, in particular, seems concerned with gendered performances of chivalry (in tandem with the broader imperial relationship to the crusades and the contemporarily-extant cultural phenomenon wherein butchness gets tied to notions of chivalry) – the gendered side of cavalierhood that plays on chivalry and butchness (as we see with cytherea and gideon) makes sense when read off of these two as something of a prototype

the conclusion to all of this being that i think you can make a case for the gendering of cavalierhood orienting itself around the kinds of cultural values that we as contemporary readers associate with butchness, and that muir uses cavalierhood to interrogate notions of that particular model of queer masculinity in relation to imperialism.

past this heavily speculative work, we can of course also look to more immediate, concrete moments in the text that reveal something about the social norms shaping the necromancer-cavalier dynamic. the most obvious example is that of abigail and magnus – a deeply milquetoast heterosexual couple who we see experience social punishment for the ‘transgressive’ nature of their relationship, ie. that they are married. i’ll break this down in much more detail in the next section, but we see the relationship taboo again with judith and marta (and judith and coronabeth). alongside this taboo against marriage or romantic relationships between a necromancer and their cavalier, we see a demand for devotionalism to excess, such that eg. babs is socially punished for not being adequately devoted to ianthe (which in practice only means having a sense of himself as an individual outside of the role of ‘ianthe’s cavalier,’ which of course is a major blockage in the ultimate trajectory of cavalierhood), and coronabeth is of course held up as the cavalier that babs failed to be. from these jumping-off points – that muir uses the necromancer-cavalier dynamic as a means of unpacking butchness, or butch/femme relations, under imperialism; that the dynamic demands a subjugated devotionalism whilst being held at arm’s length from ‘traditional’ relationships, which themselves imply a certain level of equality – we can move on to the big, overarching statement making up the core of how muir thinks about gender. which! is!

cavalierhood, masculinity, chivalry, and imperialism

the nature of a fictional society constructed as a ‘no-homophobia’ world not out of twee, stultified notions of escapism that frequently get invoked when queernorm worldbuilding is discussed, but via a conscious process that was carried out by someone with values relatively contemporaneous to our own alongside an imperialist agenda is such that that tlt is at once able to remove itself from overly interior preoccupations that can stunt a narrative from gaining any real, compelling momentum and, as i said in my introduction, question where the colonial forces that initially ‘created’ or necessitated heteropatriarchy (and, of course, homophobia and transphobia and the extant gender binary in the first place) are dispersed to when the imperial fold absorbs (a model of) queerness. it’s the underlying principle of contemporary discussions of homonationalism, and it’s what muir takes up in her rendering of cavalierhood-as-butch.

way back when i first read tlt – probably one of my first posts on this blog, actually – one of my biggest questions concerned how gideon’s butchness took shape within her in-text sense of self; what were the models of masculinity that she had available to her? how tied to manhood were they – how much did her butchness inform or complicate or add to her womanhood? this whole essay is one big answer to that question that i had rotating in my mind from the start, and i really do think the short simple answer is – cavalierhood, as a gender, as a social formation, is the means by which she understands herself as a butch; or more precisely, the means by which we understand her as a butch, because cavalierhood on its own acts as a repository for the cultural values that muir wants to mobilise. gideon, in a ‘no-homophobia’ society, doesn’t receive the concept of butchness as culturally legible in the way that we with our set of values are doing; she does, however, have the state of cavalierhood at her disposal.

this isn’t to say that there aren’t alternative models of masculinity available to her and that their forces weren’t being exerted on her prior to the start of the narrative. when we first meet her in gtn, she conceives of her gender in relation to the cohort, and you could probably make a case for aiglamene as some kind of model of gender for her; certainly their relationship seems to have an undertone of ‘older butch/younger butch.’ that cohort-esque masculinity is also, for obvious reasons, tethered to imperialism. but crucially, the thing that gives the narrative of gtn momentum is gideon undergoing a corruption arc via ‘learning’ cavalierhood; the whole thing is mobilised by the need to get her to a point where she is able to kill herself and undergo lyctorisation at the very end. and the end result of that corruption means total absorption into the imperial fold. as such, cavalierhood is the focal point for questions of masculinity and imperialism alike.

i’ve talked elsewhere about notions of ‘queer chivalry,’ most commonly butch chivalry, and the fact that chivalry as a social phenomenon is inextricable from a violence akin to imperialism that valorises a particular form of white, christian masculinity. that the model of cavalierhood which cytherea teaches gideon is a chivalric one is clear – the seventh house is, for lack of a better term, a deeply ‘chivalric’ house imbued with medieval aesthetics, and the seduction conducted by cytherea closely resembles courtly love, being at once relatively chaste and undercut by notes of desire that are eroticised by the very fact of their going unrealised. or even just the name ‘dulcinea’ being a reference to don quixote, wherein ‘dulcinea’ is an idealised, nonexistent lady constructed by a man trying to perform knighthood, and also a stand-in for the glorified vision of the spanish empire. this chivalric construction is rendered alongside cytherea’s fetishism of gideon – to give a few examples:

‘Dulcinea said, “Draw your sword, Gideon of the Ninth.”“Oh, very good!” said Dulcinea, and she clapped like a child seeing a firework. “Perfect … just like a picture of Nonius. People say that all Ninth cavaliers are good for is pulling around baskets of bones. Before I met you I imagined that you might be some wizened thing with a yoke and panniers of cartilage … half skeleton already.”’

this of course being relatively self-explanatory – part of her flirting involves thinking gideon looks hot with a sword.

‘The Ninth’s cavalier elect would walk past an open doorway, and a light voice would call out Gideon—Gideon! And then she would go, and no mention of her sword would be made: just a pillow to be moved, or the plot of a romance novel to be related, or—once—a woman seemingly lighter than a rapier to be picked up and very carefully transferred to another seat, out of the sun.’

drawing on the strand of chivalry that valorises being in the service of a lady without ever making explicit advances; it’s of course noteworthy here that gideon has moved from being falsely ascribed the title of ‘cavalier’ to being ‘cavalier elect,’ implicitly in the process of becoming a cavalier via that which cytherea is teaching her.

‘“Do you ever think it’s funny, you being here with me?” she asked once, when Gideon sat, black-hooded, holding a ball of wool for Dulcinea’s crocheting. When Gideon shook her head, she said: “No … and I like it. I send Protesilaus away a good deal. I give him things to do: that’s what suits him best. But I like to see you and make you pick up my blankets and be my scullion. I think I’m the only person in eternity to make a Ninth House cavalier slave away for me … who’s not their adept. And I’d like to hear your voice again … one day.”’

‘“Are your biceps huge,” she said, “or are they just enormous? Ninth, please tick the correct box.”

Gideon made sure her necromancer couldn’t see her, and then made a rude gesture. Dulcinea laughed her silvery laugh, but it was sleepy somehow, quiet. She pointed serenely to a spot next to her seat and Gideon obligingly squatted there on her haunches.’

both of these are doing similar work to the first two quotes – a fetishism that relies on servitude and obedience + masculinity in equal measure. this is a pretty consistent pattern throughout with how cytherea talks to gideon – like, you get the point.

and, most potently, immediately after she tells cytherea that she isn’t the real ninth cavalier:

‘The smile she got in return had no dimples. It was strangely tender—as Dulcinea was always strangely tender with her—as though they had always shared some delicious secret. “You’re wrong there,” she said. “If you want to know what I think ... I think that you’re a cavalier worthy of a Lyctor. I want to see that, what you’d become. I wonder if the Reverend Daughter even knows what she has in you?”

They looked at each other, and Gideon knew that she was holding that chemical blue gaze too long. Dulcinea’s hand was hot on hers. Now the old panic of confession seemed to rise up—her adrenaline was getting a second wind from deep down in her gut—and in that convenient moment the door opened.’

the two points to draw from this are 1) that this is about as close to explicitly erotic as these two get – like, it’s a heavily sexually tense scene – and it’s also the moment where cytherea tells gideon not only that she ‘is’ a cavalier, but she is a cavalier ‘worthy of a lyctor,’ ie. cytherea’s seduction of gideon and her transformation of her into a cavalier able to go through with what gideon goes through with at the end of the book are one and the same, and 2) that this is a point of no return, in a sense, for gideon; that she tries to deny the authenticity of her cavalierhood, and finds herself corrected by cytherea. there’s a brief window in the narrative after this where she thinks about herself as cytherea’s cavalier, before pivoting to loyalty towards harrow, but from this point onwards she no longer has a sense of herself as not a cavalier. (possible exception here being her insistence on not being harrow's 'real cavalier' at the very end, and harrow then corrects her in much the same manner as cytherea here.) that we get a reference to cytherea’s (loveday’s!) eyes here – and they are described as ‘chemical,’ an adjective far more ominous than romantic – forecloses gideon’s fate by leaving the fact of it hanging over the whole scene, the seductive-romantic element with which we receive these references to cytherea's eyes now being inextricable from what they represent. the narrative cogs, so to speak, are all in place for the completion of the corruption arc, and the mode of cavalierhood that she learns from cytherea is one sutured to butchness and to chivalry alike. (not to be a shameless self-promoter, but if you’re interested in the Happenings wrt cytherea’s gender, i write a ton about it here!)

and of course, from htn, this snippet that reveals cytherea’s fetishistic relationship to cavalierhood in general:

‘Eventually, she said: “I think I wish Cytherea were here.”

“I don’t,” said the saint on the other side. “We would have had to suffer her favourite conversation of Who had the hottest cavalier?”’

really excellent breakdown in this essay on how grief for cytherea in particular is corrupted by imperialism to become fetishistic and dehumanising – the essential takeaway here is that cytherea’s fetishistic relationship to cavalierhood, and the fetishism of cavaliers in general, is axiomatic to maintaining the imperial necromancer-cavalier gender structure. we get another glimpse of this fetishism and its dissemination throughout the house culture in as yet unsent, when judith explains her teenage crush on marta.

‘I’d been secretly reading material … I was convinced … I thought it was a natural development, or at least, one nobody had to know about. Lieutenant Dyas was so handsome, so attractive, so alive. In my childhood I had already developed a taste for … strength, physical vivacity. What’s more, it’s a necromancer’s privilege to see their cavalier in moments of vulnerability. I was very susceptible.’

here of course, rather than receiving an account of this fetishism through cytherea’s deliberate and agentive predation that we understand to be morally reprehensible, we receive it via seventeen-year-old judith who gives a deeply sympathetic account of her struggling to understand what we recognise as a straightforward crush on an older woman because of the extent to which the cultural subjugation of cavaliers and stigmatisation of necromancer-cavalier relationships had shaped her notion of what it meant to find marta attractive. the reference to marta being ‘handsome’ arguably puts her in a camp closer to butch-type masculinity, and the emphasis on physicality is a reflection of a cultural impetus towards objectification. we see judith putting her attraction to marta – and to other people with ‘strength, physical vivacity,’ the sorts of traits that she admired in marta – in terms of clear guilt and disgust, ie. that she had ‘developed a taste,’ that she was ‘susceptible,’ unable to conceive of this mode of attraction as anything other than a fetish (and the fact of it being a fetish, in turn, being a source of discomfort and moral failing). i think it’s pretty clear that the way judith talks about marta is invoking queer women grappling with their attraction to other women on an abstracted level, which is ofc worth flagging here.

‘She didn’t have to tell me in so many words what we both knew, that the relationship between cavalier and necromancer could so easily curdle into codependency… a loss of self on both sides. An obsessive fusion of halves, not two complementary forces. We were both Cohort born and bred; I should have known better. She forgave me instantly. The fog cleared much quicker than I deserved. I knew without having to be told what I’d done wrong… And I didn’t err, ever again.’

‘I told her that when I was younger I was overwhelmed by the cavalier relationship. I told her that I hadn’t expected it to feel that way. I told her, using efficient and unsentimental language, that the love Lieutenant Dyas showed me as my cavalier—in all the ways she had made us one flesh—turned my head completely. I told her how deeply I had fallen for Marta Dyas as a woman, to the point where one evening I tried to make things different between us.’

with these two quotes, we get a really strong sense of how ingrained this subjugatory mode is, such that judith needs to talk about her attraction to marta ‘as a woman’ (whether this means judith as a woman or marta is unclear, though i would hedge my bets on it being marta, just because the syntax makes more sense when in reference to the object of the sentence, i think?) ie. implicitly moving her away from as a cavalier. womanhood is a space where what judith considers to be ‘legitimate’ attraction can be realised and acted on, but cavalierhood is the framework limited to the fetishism towards which she feels such a visceral disgust. it’s a gender!

so what we’ve got here is a fairly substantial set of evidence for cavalierhood-as-gender resembling cultural performances of chivalry presented through a prism at once fetishistic and seeking to identify these performances with butchness, as a means of ultimately picking through the ways in which lesbian masculinity can be cannibalised by the demands of imperialism. alongside reading cavalierhood as functionally similar to a subjugated gender within the imperial system, we can map the necromancer-cavalier binary onto the purpose served by our contemporary western imperialist system of gender and of sexual dimorphism, ie. as systems of taxonomisation by which colonialism is carried out, and the subjugation of (in this case) cavaliers being in itself a means of maintaining imperialist order.

even before gideon comes to understand herself as a cavalier, we see her conceiving of herself and her body via the heavily instrumentalised language of imperialist warfare.

“You didn’t need half of what she’d done to gain medical entry to the Cohort, but she had fed her entire life into the meat grinder of hope that, one day, she’d blitz through Trentham and get sent to the front attached to a necromancer’s legion. Not for Gideon a security detail on one of the holding planets, either on a lonely outpost on an empty world or in some foreign city babysitting some Third governor. Gideon wanted a drop ship—first on the ground—a fat shiny medal saying INVASION FORCE ON WHATEVER, securing the initial bloom of thanergy without which the finest necromancer of the Nine Houses could not fight worth a damn. The front line of the Cohort facilitated glory. In her comic books, necromancers kissed the gloved palms of their front-liner comrades in blessed thanks for all that they did. In the comic books none of these adepts had heart disease, and a lot of them had necromantically uncharacteristic cleavage.”

this passage in particular, as well as the general repetitive, exhausting emphasis on gideon’s body that serves to highlight her own obsession with her physicality, tethers her relationship to her selfhood (and her gender) to the extent to which she can instrumentalise her body for warfare (a self-objectification, in a sense), and in turn tethers this instrumentalisation to imperialist expansionism. however, crucially, this initial imperial gender model within which she understands herself remains a fantasy – she never actually makes it to the cohort, and it functions as little more than scaffolding to be transformed into the cavalier-gender. gideon as we meet her in gtn is in a position of relative precarity where the imperial system is concerned – whilst still a part of the imperial core, she is heavily, violently subjugated, denied virtually all autonomy, and prevented from participating in the system of imperial expansionism in the way that she wants. she is also, by virtue of being wake’s daughter and the circumstances of her birth being what they were, positioned at an uneasy crossroads between anti-imperialism (wake’s daughter, thus proximate to BOE) and about the highest, most immediate form of imperialism a person can be (god’s daughter, named for a lyctor). this is an ambiguity that remains unresolved and that i imagine nona the ninth + alecto the ninth will take up. we also understand her desire to participate in this system as, effectively, the best she can do with what she has; ie. that she sees the cohort not as an outlet for her imperialist ambitions, but as what she understands to be her only chance at escaping the brutal subjugation on the ninth. this doesn’t excuse it – i don’t think muir is the sort of writer who’s concerned with justification or excuses or apologism – but it makes it far easier to understand how her coming to cavalierhood was corruption via a reshuffling of preexisting conditions.

when harrow rejects gideon’s sacrifice, she carries out a rejection of lyctorhood and thus a(n incomplete – harrow still very much Does Imperialism throughout htn, but she is functionally useless to god in the long term, as we see) rejection of the imperialist project that lyctorhood finalises. gideon’s resentment of harrow for this is of course indicative of the extent to which she internalised the values of cavalierhood, which in turn flags her allegiance to imperialism. the sense of intense stewardship she feels over harrow’s body and the inability to admit to her own personhood – the references to showering with her clothes on, taking care not to touch harrow’s skin, panicking over the thumbs because they weren’t hers to lose – signifies, obviously, her refusal to accept being kept alive when being alive means being not the form of cavalierhood that she chose for herself, but also takes on a very literalised form of that process of instrumentalisation that she had been chewing on from the start. by the end of htn, she no longer sees herself as an individual subject, but as an instrument of lyctorhood and of imperialism.

to more closely highlight the relationship between gideon’s gender situation and cavalierhood-as-imperialism, it’s worth honing in on the points at which she is most explicitly codified as ‘masculine’ in-text.

her name – as obvious as it sounds, it’s a masculine name; and it’s also the name of a lyctor, ie. god’s imperialist vanguard, given to her via his thwarting of an anti-imperialist plot.

the clothes she wears in gtn are ortus’ resized to fit her – i know ‘men’s clothing’ is probably somewhat meaningless in a culture that valorises masculinity in cavaliers, but it still serves a purpose of signification for us, and the putting on of it comes alongside the adoption of cavalierhood, which is in turn an adoption into the imperial fold.

as outlined above, we see her held to a somewhat masculinised standard of attractiveness, ie. she’s hot because she’s Built and has a Massive Sword. this is of course a standard imposed upon cavaliers, and subsequently a standard modelled off of the need to physically reinforce imperialist expansionism.

the plot of ‘the necromancer’s marriage season’ in htn is a jokey reference to ianthe spending the whole book thinking that she’s in a romance novel and acting accordingly; ianthe is ‘abella trine,’ corona is the sexy swordswoman, harrow is the tedious widow, and gideon is the saintly husband. in other words, we receive gideon as harrow’s husband (as harrow’s cavalier) alongside the notion of her as ‘saintly,’ which in turn is inextricable from ‘imperialist.’ in order to get to the point where she could be ‘saintly’ – where she could be the christ allegory fully realised – she had to ingratiate herself into the imperialist order.

the matthias nonius comparisons – pretty straightforwardly, it’s a model of cavalierhood, which is, of course, imperialist.

the line about her feeling ‘emasculated’ around cytherea – it seems minor, but to my memory it’s the only reference we have to her thinking about herself in an explicitly masculinised manner. it’s also carried out in relation to cytherea, which is significant for all the reasons explained above.

extremely worth flagging that these standards are built around a mode of masculinity that centres whiteness, and that gideon is māori. as much as she doesn’t have the framework to conceive of māori identity and colonial subjugation in the manner that we as readers are able to, it still carries metanarrative weight; that she understands herself in relation to a hegemonic, colonial masculinity again reifies the relationship between her gender and imperialism.

in essence – to sum up this absolute weapon of a section – muir models cavalierhood as a form of gendered subjugation codified in relation to butchness in order to interrogate how a homonationalist approach to queerness that seeks to hypothetically do away with homophobia (and perhaps transphobia) whilst still having need of gendered, sexual subjugation in order to bolster imperialism (necessarily, because that is … how imperialism functions) will cannibalise queer gender configurations, with a focus on lesbian masculinity.

conclusion

i did initially have a final section here detailing how necromancer and cavalier function not as fixed, intransient states of ‘oppressor’ and ‘oppressed,’ but as social forces whose violence is revealed at the point of transgression, much like how we understand gender in contemporary terms. i was going to talk about ianthe, coronabeth, and pyrrha as three characters given messy, ambiguous, arguably trans-adjacent (clearly trans, in pyrrha’s case) positions within that abstracted gender system, and what that can elucidate around cavalierhood and imperialism that the gideon-focused reading doesn’t manage to do. however, i then looked at the word count on this google doc and rethought a few of my life choices, and i’m now planning on doing all of that in a separate essay over the next couple of weeks. i think the argument behind it is worth flagging here, though, to steer this essay away from what could uncharitably be taken as an essentialist interpretation.

anyway – to recap! gender as we, contemporary readers, will typically understand it holds little to no social weight beyond some notion of it being vaguely extant in-world due to the impetus for its enforcement being removed from play; gender, along with the dimorphic sex model and broader systems of taxonomisation, is a necessary mechanism of colonialism; muir abstracts this mechanism onto the necromancer-cavalier dynamic, specifically the means by which cavalierhood functions as a subjugated gender, in order to interrogate homonationalist configurations of queerness, with a focus on butchness. at the same time as cavalierhood is a subjugated mode, it is a necessary component of imperialist expansionism – that subjugation is in fact integral to maintaining this system. the fact of gideon the ninth being a corruption arc in which gideon learns a ‘correct’ performance of cavalierhood such that she becomes capable of dying for harrow by the end exemplifies this – we see her understand her gender through these imperialist frameworks available to her until her gender becomes inextricable from both her subjugation and her allegiance to imperialism. all of this – the last two books, essentially – presumably functions as a setup from which muir will be able to pursue her interrogation of how this dynamic can be reshaped, destabilised, and ultimately torn down as the anti-imperialism of the locked tomb begins to calcify in-narrative.

thank you for reading!

724 notes

·

View notes

Text

died and came back exactly the same but something was so so so wrong with me before and now I have an excuse to really lean into it

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-work sketches

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

He often summoned you for a theoretical lesson, or the cups of tea you still hated but would have rather seen your skin flagellated off than say so, or simply to sit in silence. He had a trick of asking you to come over and talk, and then never actually talking, but sitting with you watching the asteroids continue their graceful orbit around a thanergenic star.

youtube

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes you have to search up a character on your own blog just to see what a real one is saying about them

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

mutuals we’re not pretentious we’re just always right. not our fault

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost of TLT metas

This is mostly for my own reference, as tagging doesn't seem to guarantee something being findable on Tumblr...but if you like wildly overthinking lesbian necromancers in space, enjoy!

Overthinking the Fifth House:

What is a "Speaker to the Dead"?

Actually, Magnus Quinn isn't terrible at sword fighting

Imperial complicity: Abigail the First

Pyschopomp: Abigail Pent and Hecate

Did Teacher conspire with Cytherea to kill the Fifth?

What does the Fifth House actually do?

The Fourth and the Fifth can never just be family

Cytherea's political observations at the anniversary dinner

Abigail Pent's affect: ghosts and autism

Were the Fourth wards of the Fifth?

Abigail probably knew most of the scions as children

Magnus Quinn's very understandable anger

Fifth House necromancy is not neat and tidy

Are Abigail and Magnus an exception to the exploitative nature of cavaliership?

"Abigail Pent literally brought her husband and look where that got her" (the Fifth in TUG)

The Fifth's relationship dynamic

The Fifth's relationship is unconventional in a number of ways

The queer-coding of Abigail and Magnus' relationship

Abigail and Palamedes, and knowing in the River

Was Isaac the ward of the Fifth?

Did Magnus manage to draw his sword before Cytherea killed him? (and why he probably had to watch his wife die)

How did Abigail know she was murdered by a Lyctor?

Fifth House necromancy is straight out of the Odyssey

The politics of the anniversary dinner (and further thoughts)

Was Magnus born outside of the Dominicus system?

Overthinking John Gaius:

The one time John was happy was playing Jesus

Is Alecto's body made from John's?

Are there atheists in the Nine Houses?

Why isn't John's daughter a necromancer?

The horrors of love go both ways: why John could have asked Alecto 'what have you done to me?'

Why M- may have really hoped John was on drugs

What is it with guys called Jo(h)n and getting disintegrated? (John and Dr Manhattan)

John's conference call with his CIA handlers

Watching your friend turn into an eldritch horror

Why does G1deon look so weird? (Jod regrew him from an arm)

When is a friendship bracelet not a friendship bracelet?

Why did John have G1deon hunt Harrow? (with bonus update)

The 'indelible' sin of Lyctorhood and John's shoddy plagiarism of Catholicism

Are John Gaius and Abigail Pent so different?

What was Jod's plan at Canaan House?

John and Ianthe tread the Eightfold path

The Mithraeum is more than a joke about cows

When was John Gaius born? (And another)

John Gaius and the tragic Orestes

John and Jesus writing sins in the sand

John and Nona's echoing chapters

John's motivations

Is Alecto just as guilty as John?

John's cult (and what he might have done to them)

The horror of Jod

Did John get bloodsweat before he became god?

Some very silly thoughts about John and Abigail arguing about academia

Overthinking the Nine Houses:

'No retainers, no attendants, no domestics'

Funerary customs and the violence of John's silence

Juno Zeta and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad time

The horror of the River bubble

Every instance of 'is this how it happens' in HTN

Feudalism is still shitty even if you make it queer and sex positive

How do stele work?

Thought crime in the Nine Houses

The Houses have a population the size of Canada

What must it be like to fight the Houses?

You know what can't have been fun? Merv wing's megatruck on Varun day...

Augustine's very Catholic hobby (decorating skeletons)

Necromancers are not thin in a conventionally attractive way

Matching the Houses with the planets of the solar system (though perhaps the Fourth *is* on Saturn)

Why don't the Nine Houses have (consistent) vaccination or varifocals?

How would the Houses react to the deaths at Canaan House?

How does Wake understand her own name (languages over 10,000 years)

What pre-resurrection texts are known in the Houses?

Camilla and Palamedes very Platonic relationship (further thoughts)

The horrors the Cohort found at Canaan House

Do the Houses understand the tech keeping them alive?

The scions from an external perspective (sci fi baddies)

Cav cots

The Nine Houses and feudalism

The horrors of early necromantic education

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

the version of GTN that exists in fans’ heads is usually better than the text itself

wrong! the diametric opposite of this is true. the version of GTN that exists in the heads of the fandom sucks shit but the actual book is good

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

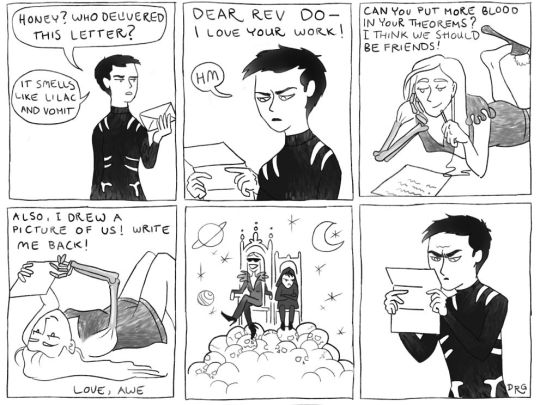

Terrible, horrible metafan comic based on Kate Beaton's Poe shortie at Hark! A vagrant featuring the worst possible space lyctor ship; please enjoy

I'm also going to include a detail shot because this was my proudest moment

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

hello ladies

518 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i should fall, will it all go away?

every damn time .. love u saint of the grindset <3

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

you guys think camilla hect would beat the sleeper in a fight? camilla hect against awake remembrance of these valiant dead? camilla hect who got dealt a lethal blow by ianthe naberius? get real.

#sorry. i'm pissed off#you think CAMILLA HECT.#i'm not saying she's not a good duelist she clearly is#but wake spent her whole life fighting necromancers and their cavaliers#they had to summon the ghost of matthias nonius to fight her and he barely won and only bc her guns stopped working

28 notes

·

View notes