Text

Lorna F., Or, The Emancipation of One Dead Corpse from the Clutches of a Girlboss Necrophile

The electronegativity disruptor whizzed erratically. Lorna kicked it. It was an old model, found in a dusty old shop where it did nothing but grow rust, and she had spent days oiling it, fixing it, fine tuning it so she could coax precisely what she needed out of it. She kicked it again, her steel-capped boots bouncing against the machinery, for good measure. That would have to do. Already, she could hear the storm brewing, crackling over the mountains. The birthing tank bubbled gently with bioluminescent fluid. Lorna watched the thick liquid pop deep craters into the surface, oozing. Beautiful. Thunder rattled the windows in their frames. There was no time. Wires. She needed wires, wires, wires to connect the tank to the disruptor.

Thunder burst the glass windows. No time, there was no time. There. In the cabinet. Wires. From one side of the laboratory to the other, tiptoeing, cackling, around the glimmering shards of glass, Lorna unfurled the wires, connecting them, strewing them across the room, connecting them to all her purring instruments. Just in time. Lighting cracked, sending surging electricity flying through the wires, wires, twisting, convulsing, wild snakes on the stone ground. Ha! Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful, her dark laboratory, purring, purring and pulsating, all the harnessed power of the natural world at her fingertips, a wild beast, a tiger on a leash, at her feet, at her feet, roaring with power. Thunder shook the laboratory, flattening Lorna to the ground. No point getting back up, the ground still rolling with thunder. So she waited. She stayed down, her head on the ground, protecting her face from the flying glass shards, in a fetal position, waiting, waiting for the storm, pummelling her laboratory, supercharging her instruments, roaring outside her window, to quiet. She could do nothing else.

Hours passed. The rain quieted to a patter. The storm passed the castle, wind still rushing against her ears, but softer now. Noxious fumes fouled the air she forced into her lungs, burning her sinuses as it made its way down. On the inhale she steeled herself. Crawled to her knees, glass shards glistening in the fire light, cutting into her hands. Her lab was trashed. Instruments, her instruments, lay belly up, mechanical guts splattered on the stone ground. Wires, tangled and lifeless, dangled from the ceiling. Wind from the shattered windows played with her carefully kept notes, strewing them across the room.

But it was worth it. It stood in its birthing tank, tall, tall, and breathing. Breathing. Its chest rising and falling, rising and falling, white in the dark room, rising, with the breath Lorna had given it, filled its lungs with, each rise and fall, alive, alive, each rise and fall, nourishing bloods cells she had given it, coursing through veins she had filled. Each rise and fall, a gift to her. To her. It belonged to her. On her knees, on scraped and bloodied knees, she crawled towards it, towards the chest, rising and falling, filling lungs, filling them with breath, her lungs, her lungs in its chest. A temple, a temple to her in its chest. With shaking hands she touched the skin, slick with birth fluid, placed her hands on the skin taunt over her temple, her temple of breath.

It collapsed onto her. Her knees buckled. She stood, straining, her hands under its slippery wet arms, under its armpits, letting the body fall unto her, splashing with bioluminescent fluids, guiding it out of the tank and down to the floor. Lorna pushed it onto its back. Put her mouth on its mouth and sucked the mucus out of its airways. Spit it out. The body gasped for air. It was breathing. It was. Raspy, difficult, some fluids still thick and clogging its trachea, but breathing. Kneeling next to her temple, Lorna watched it breathe. She watched it breathe until the black of night gave way to the gray of morning, until an anemic sun filled the thrashed laboratory with light. Light. The light shook her from her trance, her passive gaze resting on the body she built. Light. Lorna could examine her work.

Its white eyes unblinking, fixed the ceiling. Maybe she had given it breath but not brain. Birth fluid had dried crystalline on its skin. Red scars covered the body, raised and angry. With a finger, she traced one, from ankle to knee, joining the two parts. She felt the sutures, dark spots in the canyons of red shining tissue. Kept clean, it would heal, it would. The primary materials had been carefully curated for aesthetic appeal. Looking at her work now, now that blood flowing flushed the flesh, that corkscrews oil glands joyously secreted anew, giving the white

skin a brilliant sheen, now that a fresh growth of stubble prickled under her hand, it was even more pleasing to her than when it had laid lifeless on her work table. Although it had delighted her then too.

Looking up, she saw its empty eyes staring at her. Good. Maybe the brain did work. She grabbed the arch of its foot and rolled the ankle, testing its mobility. The body flinched. Pain. It felt pain. Its reflexes worked. Its ankle had a normal range of movement. Three facts that pleased her. Lorna moved on to the knee. Placed on hand under it, carefully, watching the face for signs of hurt, and pushed the leg up, gliding the bones against each other. Good. The knee worked. So did the other knee. All signs pointing to the excellence of her work.

She moved to its chest. A y-shaped scar ran from its clavicles down to its stomach. For the organs, freshness of the material had been a higher concern than aesthetics. And yet, looking at the chest breathe, filling with air, was to her like walking into a cathedral was to a Christian. Her cathedral, her cathedral lived in its chest. Its ribs, bumpy, visible through its skin, were for her like the vaults of the Notre-Dame, holding in between them the red sacred heart, the communion flesh, pumping with blood, and the scar she was tracing upwards and upwards, a delight of raised sutures, like a spire, like a spire, rising tall against the sky of its skin, calling the faithful to worship. It grabbed her wrist, hard, stopping her.

“You’re hurting me,” Lorna said, a smile pulling at the corners of her mouth, looking up at the body. Its own cracked blue lips stretched tentatively over its teeth. Mimicking her. Mimicking her smile. Her smile, with its teeth, teeth she had chosen for it, for the body. Straight, white, healthy, no cavities. Perfect. Perfect white teeth she had placed in its mouth, a perfect red mouth she had assembled, a mouth it was now using to echo her smile. It tightened its grip on her wrist. Lorna yelped. The body let go. Her smile widened. It had understood her. Not her words, but her manifestation of hurt, her yelp. Some kind of innate sense of empathy. A good thing, that. It’s strength surprised her. It had left a bruising mark on her wrist in the shape of its fingers.

Satisfied with the sutures she felt on its stomach, she took its heavy hand in hers. White, laced with red, black sutures, purple under the fingernails. The material seemed to be attached properly. And it had already demonstrated how well it could use it. She squeezed it before letting go. Next, its head. Between finger and thumb, she grasped its chin, guiding it on its side, stubble already growing back. Scars ran from its neck to its jaw, following it to the ears, circling them, finishing on the back of its head. A head she had shaved for ease of assembly. She did not mind the scars, no, they were palpable proof that the body was hers, hers, her creation. Under her thumb, the scar of the vermilion. She traced it, following its raised border, carved into its face by her scalpel, tracing it up to the cupid’s bow. Her little altar, there, on its cupid’s bow. With her thumb, she pried its mouth open, grabbing its tongue with her fingers, examining it, looking below it, looking down its throat. She let go of its tongue. She put her lips to its mouth. More mucus to clear. She sucked it and spit it out.

The ground was wet and packed. It was raining, making it more difficult for Lorna to dig. Up to her knees in mud, her clothes soaked with sweat under her dirty raincoat, shivering with cold and exhaustion, Lorna had to keep shovelling the dirt. One shovelful after the other. She had to get to the grave while it was still fresh, buried only yesterday. She had known the primary material while it was alive, a man from the village. Tall and strong from working the fields. Died prematurely. Maybe a heart attack. Lucky for her. The young made better harvest. Lorna’s shovel hit wood. The casket. She cleared the rest of the mud with her blistered hands, a surge of excitement powering up her tired limbs. Lately, the caskets the villagers buried were reinforced with steel, the peasants not entirely blind to her work. No matter. No match for her instruments. Straddling the casket, she bore a whole in the metal like a worm in an apple, grinding it down until she could harvest what she needed. Its head. Lorna wanted its head. She had coveted it while it was alive, seeing it at work in the fields. With thumb and forefinger, she pried its eye open. White.

Now those very eyes, wet with living mucus, were looking at her, looking at her, their re-animator, from across the dining table. The body sat rigid, arms on the table, unmoving. It had to be hungry. Lorna had pumped its stomach empty before inserting it back in its chest. It had to be hungry. She had dragged it to this room, sat it at this table, pushed a plate in front of it, and still it wasn’t eating. Very well. Maybe it needed to be taught. In her fingers, Lorna picked a chunk of bread from her plate, making her way to its side of the table. Prying its mouth open, she placed the bread between its teeth, on its tongue, forcing it to chew. She made it chew one more time. She had its full attention, she saw, one hand under its jaw, holding its mouth shut, the other pointing at her own throat, she swallowed. It did the same, its Adam's apple bobbing down, tense in its reconstructed neck.

It choked. Lorna held its mouth shut, held it shut, held it shut, as it sputtered and coughed, her grip slipping on its drooling chin, still she held it shut, held its mouth shut until it stopped choking, caught it its breath, its breath regular against her palm. There. She wiped the drool from her hands. Now it knew how to eat. She broke off another piece of bread. It recoiled, flinching. Smiling, she put the bread in her own mouth, chewing, looking down at her work. Its eyes were bright with tears, its face smeared with spittle. But with trembling hands it did the same, broke a piece of bread and placed it in its mouth, chewing. Her work, her work, mirroring her gestures.

The blood had been hers. Easier to source. For weeks, Lorna ate red meat and leafy greens, pricked needles in her arms, in her veins, watched the tubes uncoiling, turning red with her blood, again and again. Her blood would flow through the body’s veins. She would own it from the inside out. But the body wasn’t ready yet, not ready to receive the gift she pumped out of herself. She turned on the lamp, flooding the body with light. It was not finished. It was missing parts, still, organs and limbs, its shoulders ending in bruised stumps, its chest open, ribs akimbo, white between the red and glistening meat. The legs were complete, muscular, the primary material sculpted to perfection by her scalpel. She traced the raw scars upwards, on its thigh. Yesterday’s work.

The body had a head. It was attached to its neck with expert sutures. Its eye sockets stared, cherry-red and empty, at the ceiling. That was why Lorna needed the villager’s head. She would take its nose too, and the few good teeth she had seen in its mouth, but what she had coveted when the primary material was alive was its eyes. With one hand, she pried its eyelid open, with the other, she took her scalpel. Started cutting. She would preserve its sight, if she could, but she did not care if the body was blind. As long as she liked looking at it.

The eye sockets now plump with the newly inserted eyes, Lorna sighed. Her work was strenuous, but the body, the body was a gift to her, a gift now a little more complete. Its mouth and nose had been reworked. Scars coursed through its face like little red rivers. The skin of the eyelids stretched thin over foreign eyeballs, the little blue veins of them visible under the fluorescent light. It would heal, it would. She put her hand on its cheek, palpating the bones she had smoothed and ground down. Beautiful. The skin, the face, her work. It was beautiful, bruised and bloodied, white skin striated purple. She put her mouth to its skin, tasting blood on her lips, tasting iron in its mouth. The body had no tongue, only hers passed its lips. Her work was unfinished. One hand under its skull, she felt the follicles below the surface, itching to sprout again, as she deepened the kiss in its tongueless mouth.

And they did. The body, shocked back to life, grew hair on its skull. Lorna felt it. Less than a millimetre, but stubbly when she stroked the back of its head. From the window of the bedroom, the body watched the sun rise over the trees. Leaves were turning yellow on the castle grounds, and in the morning light, frost sparkled on the overgrown lawn. Its skin smelled of ozone and sweat, her nose nestled in the crook of its neck, the body as still and silent and as white as the frost. It never warmed. But it did not mind the cold, it had no need for furnaces or blankets. Lorna did. At night, she dragged the body to her bed and lay beside it, its freezing skin next to hers under the frayed blanket, watching it close its eyes in something that looked like sleep.

Unblinking, the body stared at the changing colours of the leaves, trembling in the breeze. “There is nothing there,” Lorna said, wrapping one arm around the body’s waist. “There is nothing past the treeline,” she said. “I only go outside because I have to. The world ends here, there's nothing past the treeline.” Months had passed and still its skin smelled of ozone, like the lightning that sparked it to life. She breathed it in. She kept its hair short. She liked it that way, scars visible, zigzagging on its skull. Healed to a faint lavender, the scars, but still visible. She liked tracing them, tracing the scars she had cut into its flesh, the sutures she had sewed into it, point by point, remembering how the silver needle had pierced the white flesh, dragging behind it a black thread, piercing it again and again. A reminder of the excellence of her work, the scars. “I have to go.” It pained her to leave her work unattended. She pulled herself away from the body, and locked the heavy door behind her.

The man had a gift for healing. The villagers flocked to him, flocked to him that he may lay his hands on them, lay his hands on them and cure them of their diseases. Lorna saw them, saw them in the town square, thick throngs of the villagers making it hard to get anywhere. A nuisance. And yet. Lorna saw the man, cloaked in red, lay his hands on the sick, the pestilent, the corrupt, lay his hands on them like white gold spiders, lay his hands on the black and the foul and the vile, and heal them, again and again, heal them, the villagers gathering around him, flocking to him, the man in the red cloak, jostling, noisy crowds, fighting for the touch of his hands.

Unavoidable, the faith of the healer’s hands, from the first time Lorna saw them, she loved them, she wanted them, white hands in the sun, white hands laying on the black of pestilence, white healing hands. The healing hands pulled at her, compelling her to the faith healer’s bedroom under the cover of night, compelling her to take his hands from him, compelling her to stain his red cloak with healing blood, gushing forth from them, from the healer’s hands. Hands, the finishing touch to her work, her work, laying on her work table, under the fluorescent lamp, its forearms ending in stumps. Beautiful heavy white hands, hands uncorrupted by field work, learned hands, healing hands, hands, the perfect material, the freshest material, hands for her living sculpture. With black sutures, Lorna attached the hands to the stumps of its forearms, folding its limbs over its chest, her work completed. All it needed now was a little electricity. A little breath. Climbing onto the work bench, Lorna laid next to the body, her head on its cold and empty chest, and wrapped its pale arms around her. She would give it all it needed.

Her bag heavily laden with food and firewood, Lorna made her way through the forest of the castle grounds. From between the trees she saw it. The body was out. Out, on the grounds, luminous white against the ochre backdrop of dying grass, she could see it from here. She saw it linger through the autumn, she saw it lift its hands, lift its hands to study the air, feel the warmth of the sun on the goosebumps of its translucent skin, taking a few steps than stopping again, to feel more of the sun, more of the wind, its mouth open and nostrils flaring, she saw it breathe in the smells, the smell of the wet ground, decomposing leaves, the smell of frosted dew and pine needles, its eyes bulging as if blinking even once would deprive it of something, something vital. It ambled and stopped, and examined, criss-crossing across the overgrown garden, each new delight registering on its face stabbing Lorna like a knife. This was not why she had given it eyes. This was not why she had given it hands.

Every limb burning with anger, she clutched its hand, dragging it back to the castle, not looking back as she felt it stumble behind her. Pushed it inside. Locked the door behind her, the heavy oaken door. Could not bear to look at it, this body she made, only aware of it in her periphery. A lump of anger clogged her throat. How much had it seen? It had not been past the treeline. Finally, in a stilted whisper. “It’s dangerous outside,” Lorna said, “I only go out because I have to, I have to, for us. It’s dangerous outside.” She forced herself to look at it. “There’s nothing past the treeline.” Studied its inscrutable face. It had not been past the treeline. Maybe she would allow supervised exits on the castle ground. She sighed, anger waning. It had not been past the treeline. Her work was safe. Lorna pushed herself away from the door, her balance unstable still, walking over to the body, she wrapped her arms around it, her nose finding its skin. Ozone. She hugged it tight like an apology. Minutes passed. Lorna breathed in its smell, squeezing a little tighter before letting go. One arm wrapped its waist, she guided it forward, guiding it up on the stone stairs, up to the bedroom, away from the door. It did not look back. She watched it closely.

It did not eat. Flames from the fireplace cast flickering shadows on its hollow cheeks, unseeing, empty eyes fixed on some point behind her. She clenched her fist around her fork, but appetite failed her. She stared at the beast she made. It did not move. Sitting, its pale arms luminous in the darkened room, the white spiders of its hands resting on the table in front of it, it did not eat, it did not move, more quiet than when it had been dead. It did not look at her with its white eyes. She broke a piece of bread. She would make it eat.

Before Lorna reached the other end of the table, a noise came from the window. Looking out, she saw torch light, flames rising, licking at the edge of the treeline. At the centre, centre of the fire, a man, a man with a red cloak and no hands. They came from the village, they came from the village to destroy her work. She would not allow it. In her fist she grabbed her beast’s hand, dragging it, dragging it behind her, darting through stone corridors and corridors and flights of stairs. They would not destroy her work, no, she wouldn’t allow it. There was a passageway in the cellar, only she had to get there, dragging, pulling the heavy body stumbling behind her.

The oaken door came down with a booming noise, the villagers desecrating her ancestral home. Lorna tightened her clammy grip on the beast’s hand. In the dark and dusty cellar, she looked for the hidden doorway, the hoards stomping overhead. Raising both her hands, she felt for a breath of air, a whisper of wind, the only clue in locating the hidden tunnel. There. On the left wall. A loose brick. She jiggled it free, opening the door on a damp and dirty hole. Safe passage.

Lorna reached behind her for the beast’s hand. Her work had to be protected. Did not find its hand. She turned around. It ignored her outstretched hand, but, stepping closer, towered over her, luminous in the black room. Closer, another step, it dwarfed her, Lorna, her lungs heavy like lead. It raised its white hand, raised it high, high, to her face. With the thumb of a healer, it touched her lips, forcing it past her teeth, the beast put its mouth to her. She fell, fell down, backwards into the tunnel, bile in her mouth, spitting, quickly, quickly, closed the door, closed the door on it, closed the door on the monster she made. Eyes bulging from their sockets, she watched, watched, as the door shut, shutting him out.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foie Gras

Male pattern baldness fascinates you. His bald head glimmered enticingly from across the room. Norwood seven. The crown jewel of male pattern baldness. A head entirely depleted of vile mammalian hair, save for the sides, which he shaves. You can tell. There the skin is gray. Follicles, dormant, waiting to burst through and sprout anew. Pink and gray, rough, lined and textured. Cratered by acne scars. You admire it from afar, the texture of his skin.

So male pattern fascinates you. It’s not polite to stare at men’s hairlines. But his lack of hair has you enthralled. His bald head glimmers enticingly from across the room. Norwood seven, the bone of the sacred skull visible under the skin, the skin of the dome, which shines like its own source of light, haloed by a half circle of gray shaved skin where the hair still persists. His skin has you captivated, sealing his faith.

He sits cross-legged and bald at the bar, his balance unsteady, his speech slurring. Drunk. He sends another glass down his gullet, sending his shimmering Norwood seven backwards. Wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. Pauses. His grip tight on the bar, he pushes himself to his feet. An unsteady drunk stumbling on his feet, or, as you perceive it, an opportunity.

You are by his side with an arm around him, and you carry him, him, jovial, trusting, mollified by the drink, already leaning on you with all of his heavyweight body. He is heavy and drunk and warm. A warm body full of drink. You carry him home. Drag him, more like, drag him to your bed. Lay him on his side. Lay him on his side so he doesn’t drown in his own sick. Clean his vomit. Tuck him in, up to his chin. Take care of him. Watch him.

The room is sour with the smell of his sickness, the smell of his sweat, as he tosses and turns in the restless sleep of the drunk, eyeballs rolling under red and raw eyelids. You study the topography of his features. Jutting Adam’s apple, stubble on his jawline, not much of a nose, but nose enough. Crooked teeth hidden under a thin, square mouth. With your index, you pull his lips back to see them. You take your finger out from his mouth, and use it to continue your topographical analysis, dragging around a shining trail of his own spittle on his cheek. Drag it on his scalp, caressing, gray and enticing. An ingrown or two, red and inflamed, pus ready to burst.

When he wakes up you are by his side with all he needs, solicitous. Coffee. Water. Heaping plates full of food. Eggs. Bacon. Sausages. Oatmeal. Pastries and toast. The light cracking through the curtains makes him groan. The sound of an animal in pain. Flushes your insides with warm delight. The groaning stops, quickly followed by the sounds of heaving and splashing bile.

He tells you he feels better, still, you watch him amble, unassured, through the stone corridor of your castle. It’s late in the afternoon. He tells you he is looking for the room he woke up in, but just can’t seem to find his way back. You tell him you cooked for him, would he like to eat something first? You offer your arm to guide him. Anything for the touch of his skin.

You heap more food on his plate. Fill his glass again. Watch him soak his bread in the running juices of the meat, the butter. Watch his teeth wet and crooked as he tears another mouthful of meat, wipes his mouth on the back of his hand, leaving it shining with saliva. When he finishes eating the plate after plates that you serve him, you offer to show him back to his room. He is welcome to stay another night, if he wants. He does.

He could leave if he wanted to. You left every door open, the wind rushing through the winding down dark corridors. Over breakfast, he tells you he wants to understand the floorplan. Shows you a sketch he has made, theorizes about the layout, how none of the corridors ever seem to be the same length. You watch with rapt attention as his expressive hands move over the sketch he has made, listening to him explain your home to you.

The hair around his crown has grown luxuriantly, but his dome remains untouched by the wild jungle encroaching. His enthusiasm has left him. It takes him a minute to chew a morsel of bread, his eyes unfocused. You put your hand on his back when you fill his glass, trace your hand on his shoulders, feeling the fibres under his skin, his arm and plumb body. He wants to understand the workings of your castle, to understand how the solid walls of your home seem to shift and swell, then shrink again. He could ask you if he wanted to. He could leave if he wanted to. You serve him again, more food on his already full plate.

The walls are closing in, water weeping, oozing, from the stone. He is frantic, desperate, still, to understand the floor plan of your home. Sketches drawn by his hand litter the floor. He could leave if he wanted to. He balls up another sketch, throws it on the floor. With your eyes, you follow the shimmering of his scalp as he disappears again down into the corridor, only to reappear again behind you after a minute. He tells you this time it took him half the time it did before. You ask him if he is hungry.

He doesn’t eat. He doesn’t drink. Only stares, unblinking, at the wall, gears turning under his polished dome. Words burst out of him like pus from a pimple. He says it doesn’t make any logical sense, how could stone walls be stretching then shrinking like a living thing? His voice chokes, trails into silence, he lets his bald head crumble into his hands, you watch his shiny skin, his shoulders folding in, his strong arms flinching under the weight of his dome.

Standing up, you give him your arm to guide him (anything for the touch of his skin). He takes it. His hand is warm, heavy, full of hair and vitality. Around you, the walls weep clear fluids, the stones, engorging themselves full, stretch, as you walk him to the open door, the wide open door where the wind rushes in.

Standing behind him, you look down, down at the desolate grounds, lunar-like and barren. The trees that grow on the grounds of your castle are turned into twisted cripples by the wind. The man sits down on the doorstep, torn, between going home and understanding. He could leave if he wanted to. His curiosity condemns him. He stays.

You lead him back in where the walls are leaking and the stone is flushing. You walk with him, nestling in his warmth, taking him in, showing him how the walls breathe, expand, how the long, twisting corridors unfurl, straightening themselves out. You walk with him to the kitchen table. Now he understands how the castle works.

Lay him on the table. Lift his shirt. Cut him. A small incision on his side, between jutting hip bone and his lowest rib; a red mouth on his white skin. Trace the lips of his wound. Put two fingers in. Feel his flesh tense around your fingers, see his eyes widen, his breath catch, sticking in his throat.Study his face, his complaint face full of shocked angularity.

Slide your hand in, under his skin, like you would a chicken, lifting, lifting his skin from his flesh. You’ve cut no veins. No blood spills out. Reach in deeper, for his liver, feel his pulse around your fingers. His head rolls back, his neck exposed, his eyes close. Groaning. The sound of an animal in pain. His flesh shivering and trembling, feel it engulf your hand, your hand, tuck it under his ribs where it's warm.

Touch his liver, the smooth, warm organ, caressing, with the tips of your fingers. Reach for it, grab it, pull at it. Pull his liver from his wound. Taste his liver on your tongue, taste the whole of his liver with your tongue, feel him pulse, shiver, in your mouth. Bite down. Your teeth cutting through the sponge-like organ, filling your mouth with his warmth, running down you, lighting you up shock full of electric delight. Out of the corner of your eye, see him die.

Swallow. Bite down again.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palms of the Prophet

Roses bloom in the palms of the prophet. Roses bloom in the palms of the prophet. It’s a matter of getting them out. The razor blade is a rectangle of solid starlight, its corners pointy sharp between the fingers of the prophet. Roses bloom in the palms of the prophet, below the skin, below the lines. The prophet takes the razor and cuts, and flowers do bloom in the palms of the prophet, and blood does pour from the wounds of the prophet, the burning crimson palms of the prophet. Roses bloom in the circles of his skin, and it stings.

The prophet raises his roses towards the heavens, praying, until dewdrops of relief fall, flooding, between the petals of his skin. The prophet, endorphine-soaked, roots his roses back into the dirt, digs his hands in the soft black ground, velvet-like and soaking in, thirsty, the blood of the prophet. Every fibre of the prophet relaxes all at once.

When the prophet comes to, the feeling of heaven’s left. His hands are burning. The feeling of heaven’s left him, leaving him with nothing but the sting of cut palms. Rage blooms in him like one of his roses, and his roses are slick, warm, with his blood, and blood spills from him and soaks the ground, and he cries for air but chokes on dirt. All around him is nothing but the dirt.

All for nothing. The feeling of heaven’s left him. Wounds him worse than the cuts. All around him is nothing but the dirt, in his eyes, his mouth, gravel in his teeth, dirt in the folds of his roses. His roses reach for the buckle of his belt, his hands are for himself, on him, finding himself solid. The roses of his palms are warm and slick, and so is he, and the cuts of his hands burn when he moves them on himself, his blood, congealing, sticks and unsticks from skin to skin.

Another dewdrop of relief washes over him, this time not from the heavens, but from his hands, his own hands, working on himself, each pomp sending golden electric relief, shivering down every nerve, pulling them tight.

With a shiver, blood spurts from the roses of the prophet. Creeping red and white, intertwined, seep into the dirt. The prophet on his knees, emptied, unsticks his roses from himself. Each panting breath builds back the composure of the prophet, each breath a brick in the fortress. The prophet stands, tall as a tower, wipes his hands clean on his clothes, and leaves.

In the dark, serpents spawn forth from the site of his emissions. In the dark, worms crawl from the hands of the prophet.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

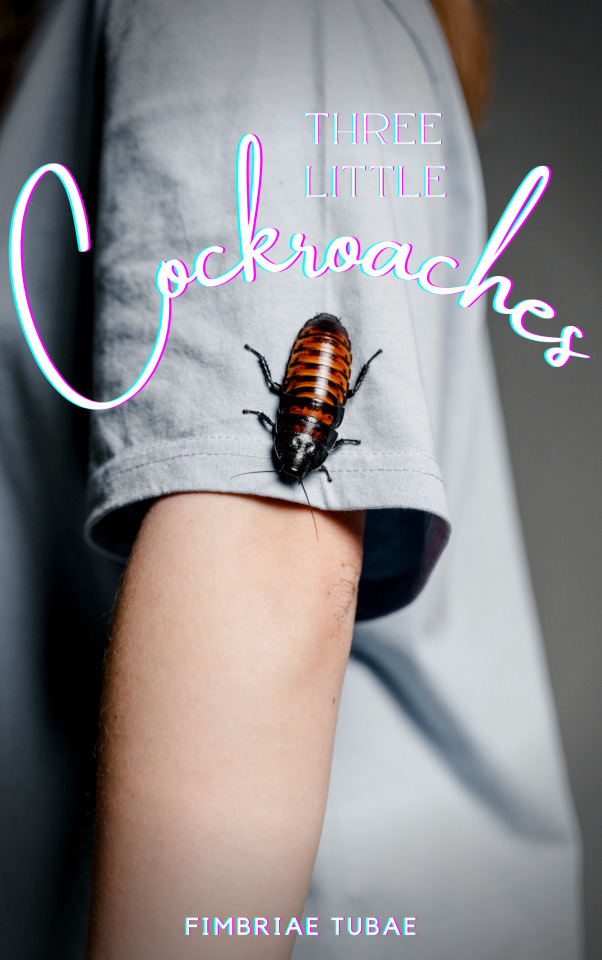

Three Little Cockroaches, or, Cumrag Revenge

“The curse needs a part of him,” said the witch. The room was hazy with smoke, thick and stinging my eyes, making them water. Incense and cigarettes. It smelled awful. I breathed in through my mouth. I could barely see the witch, but what I saw was twisted and bent and dry like driftwood. A head small and hairy like a coconut poked out from beneath her concentric layers of shawls. “I know how curses work, and I’ll get something, alright? I will,” I said, “I just wanted to talk about payment first.” There were knick-knacks on the table in front of me, witchy stuff, crystal balls, and the likes. I picked up a little statuette, three bug-like things plated in gold, and held it to my eyes. The witch was watching me, watching me with her pruny little black eyes set deep in her wrinkly face.

“Payment?” The question came out of her like dust from the bag of a vacuum cleaner. “Payment. What you take from the boy, I use as well.” Fine by me. “Deal,” I said, holding out my hand to shake hers. The witch ignored me, crawling over to her library and pulling a grimoire out of it. A heavy-looking thing, of bound leather and metal clasps, bigger than her, bigger than the little old woman, really. Should I help her? She seemed to struggle with the huge, heavy book. Before I could, she dropped it onto the table, sending knick-knacks flying on the ground, raising a cloud of dust. The witch opened it to a page in the middle. I sat up straight, peeking. Nothing. The page was blank. Her brows furrowing deep on her wrinkly face, she turned the pages, blank, all of them, until she found the one she was apparently looking for.

“You want this boy to suffer, yes?” Her index moved down the page, like she was tracing an ingredient list. Sagging coconut of a woman. “I came to you for a curse. Of course I want him to suffer.” Her eyes ran zigzags across the parchment paper. I waited for her to speak. After forever, the witch spoke with her dusty basement of a voice: “The curse needs part of him. It also needs part of you.” Sure. Fine by me. Part of me, that would be easy. Part of him, not so much. “Sure, yeah, no problem, you’ll get something,” I said, as the witch ushered me out of her house, “couldn't be easier, really.”

I had no idea how I’d do it, get close enough to him to get some kind sample of him. Every day I saw him in the corridors of our high school, but I couldn't get close enough to steal a hair, or draw some spit, or something. He avoided me, that was the whole problem, really, pretended not to see me, to be deep into a conversation with a friend, or looking at the floor intently. Maybe he thought that’d keep him safe. Only for now, now that I still needed a hair. Just the one hair and I’d make him suffer. I sat behind him in class, hoping to drill a hole in his spine with my eyes alone, or at least make a hair fall from his scalp. No such luck. And no helpful follicle left on his desk after he left, either. I checked.

But I did know where he lived. Last resort. But I pictured his house bursting full of hair and spit, and that, that convinced me. No other option. I’d break in like they did in the movies. Only I had to wait until they all left, his parents, his brothers, him; I was watching them from my car, parked on the street in front of the house, his house, full of light, buzzing with activity, every room under an amber glow, his mom cooking, his brothers doing their homework on the kitchen table. Zipping my coat up tighter, breathing on my hands to keep them warm, I watched them, studying them, waiting for the perfect moment. When the house went dark, I walked around it, testing windows, trampling on their lawn with a sense of righteous revenge.

The perfect moment came in late November. They all left, the mother, a chubby woman with curly black hair, packing all her children into the car, the father, a tall man with a bald spot, getting into the driver's seat before driving off. I was alone with the house. The house was all mine. I’d get what I needed. Laundry room. That’s how I’d get in, in the back. I picked the perfect rock, a heavy thing my fingers barely reached around. Threw it at the window, breaking it. Cleared the glass from the frame, kicking the shards off with my feet. That’s how they did it in films, so they don’t get cut. I wasn’t gonna rush in and cut myself like an idiot on the shattered glass.

I fell to the laundry room, holding my arm, bleeding. I’d missed a shard, I guess, but no time to hesitate now, not while the neighbours might have heard, heard the glass shattering and the girl falling and screaming. I’d get what I needed, but I had to be focused. Couldn't let myself bleed all over their white carpeted floor. Or bleed all over the white walls. Upstairs. That’s where the bathroom was. Combs and hair brushes. They were left out on the sink. But there was no way to tell which was his mother’s, his brothers’, or his. All had the same black and curly hair. I needed something uniquely his. No harm would come to the innocent, only the guilty needed to be punished. Something, something uniquely his.

I set the cumrag down in front of the witch. The coconut woman stared. “There’s enough of him on there for an army,” I said, “ should be more than plenty for my curse.” More than enough for her payment, too. “So? You’ll do it, right?” I asked the witch. She nodded, wrinkles rippling down her sagging neck. “The curse needs part of you, as well.” I pointed to the blood drying in rusty rivers down my arm. Her coconut head nodded no. “Menses. Equal.” When I came back from the bathroom, the witch had set the cumrag in a copper cauldron over the fire and was pouring fizzing liquids all over it. “Should I drop it in now?” I held the tampon up by the little string, dangling it. She shook her head, no, her eyes never leaving her work. Dark vapours rose from the pot. Should I set it down on the table? There wasn’t any place for it, with all the knick-knacks, and I didn’t want to stain the tablecloth. So I just held on to it, hoping it wouldn’t drip.

“And now?” It felt like hours had passed and that the witch had poured into the cauldron from all of her dark and dusty bottles, dropping into it all of her eyes of newts and toes of frogs. “Last,” the witch grunted. So I waited. “Now?” Her boney fingers grabbed my wrist hard and pulled me to the cauldron. “It needs you to do it.” The liquid was opaque black, boiling with lazy bubbles. “You want him to suffer, yes?” I nodded. “Do it.” I dropped the tampon in the cauldron and it dissolved instantly, hissing with steam.

I’d put a curse on him and he didn’t know it. I stared at the vain, crisp line of his hair at the back of his neck. Effervescent. Where he went, I followed. I followed him through the corridors of our school, I sat behind him in our classes. I had drunk three ladlefuls of the witch’s potion, chanted with her holding onto her boney fingers, chanted with her until my throat was raw, and I had put a curse on him. I wanted to see what would happen, what punishment would befall him. And hoped it hurt. I hoped he suffered. So I followed him, followed him through the flowing rivers of students. Trailing him, I overheard him talking to his friends, talking about the broken window in the laundry room, blood on the white carpet, but nothing stolen, no jewellery, no electronics. Nothing. Well, nothing was stolen that he noticed, really. The only thing I needed was the rag, and it was the only thing I took.

I waited until sundown and parked my car in front of his house. From there I waited, waited for him to meet his faith. He was in the kitchen. Lots of ways to suffer, in a kitchen. Knives. He was dicing something. Took whatever he was cooking over the oven. An oven. Maybe it would burst into flames and swallow him whole. Maybe he wouldn’t even die, but survive, burned, but alive, alive, and in pain. I wanted him to hurt, I wanted the fridge to fall on him and crush him, the knives to slip and cut him a hundred times, the toaster to electrocute him, the garbage disposal to shred his hands into minced meat, and all the cords and wires of the appliances to strangle him.

Ambulance lights flashing red and blue woke me up. In my car, I made myself as small as I could. There was an ambulance in their parking lot. The paramedics wheeled a stretcher out of the house. Then they were gone. Took with them their flashing lights and wailing sirens. I drove home.

It was his mother, his mother they wheeled out from the house. Behind him in class, I saw his head slumped down on his desk. A seizure. In hushed voices in the classrooms, I heard them talk about his mother, his mother, in the hospital, while his head was in his hands flat on his desk. That wasn’t what I wanted.

“Please, this isn’t what I wanted, you have to fix this,” I went begging to the witch. “You said you wanted him to hurt. He is.” A smile on her yellow black teeth. “This is what you wanted.” Tears stung my eyes. I shook my head, no, this isn’t what I wanted, no, no, and what I wanted was wrong, I could see it, I could see it now, crawling towards the witch. “Please. This is wrong. Please, you have to make it stop, stop the curse,” I begged her, begged the witch. She put her hand on my head, her twig-like fingers running through my hair. “Quiet, now,” she whispered, wiping tears from my cheeks, rolling them like jewels on her fingertips. “Yes, I’ll do what you want.”

I heard his mother was better. That she left the hospital. But she wouldn’t have been there at all, if not for me. I stared at his black and curly hair. Like his mother. I ran after him down the school corridor, catching up, and grabbed his arm. “I’m sorry about your mother, I’m really, really sorry.” He was staring behind me, not seeing me, not hearing me. “Thanks, yeah, it’s fine.” He didn’t hear me. I tightened my grip on his arm. “I’m really sorry about your mother.” Still, he didn’t see me, just pried my fingers from him, saying it was fine, thanks. My sleeve rode up on my arm, and I readjusted it. His face turned white, seeing the cut. Now he saw me, now he really did. “I’m sorry about your mother,” I said. He drew his arm back like I burned him.

He towered over me, holding himself over me. “I didn’t mean to, please, I’m sorry.” I shrank hard against the brick wall, continuing to beg, to apologize, please, forgive me, it’s all my fault, please, let me leave, please, I’m sorry. He pushed me, yelling at me. I fell down. All around me rivers of students went by undisturbed, stepping around me. All I saw were multicoloured shoes, walking fast, walking past me, hundreds of colourful shoes, running all around me. Until there were none, until I was the only thing under the fluorescent lights of the school corridor. I sat, cross-legged, looking at the ceiling, gray.

I was at the witch’s house again. Through the thick incense smoke, the coconut woman called to me. “Ever saw a cockroach give birth?” Eyelessly, I made my way to where the witch’s voice came from. In her crooked, liver-spotted hands, she was holding something. “Come closer,” the witch said. She was holding a glass, with a sheet of paper underneath. A cockroach. I stepped closer, closer to the witch and her bug. It wasn’t crawling around, immobile, except the back of it, its abdomen. It was pulsating. The witch grabbed my arm, tight. “See? It’s coming.” Her voice was high, strained with excitement. Something was coming out of the cockroach, white, sack-like. I tasted bile. Its abdomen was vibrating, pulsating, each pulse pushing out the sack a little more, more and more. The sack was big as the cockroach itself, pulsating with life, gliding out of its abdomen, falling out, as big as the cockroach, like the cockroach was hollow, emptied out.

A flurry of tiny cockroaches hatched, pouring out from the sack, thousands and thousands of them, transparent, unfinished, filling the glass like a tempest. The witch let go of her claws on my arm. With both hands, she raised the glass, high, thousands of baby cockroaches like glitter in a snow-globe, carefully, she walked to the fireplace, her eyes never leaving the spectacle of birth, birth in her hands, a smile sending waves down her rippling jowls. I followed her. The cauldron on the fire, bubbling thick. And smoking, black smoke reeking of ash and rot. The witch held the glass over the cauldron, then, then she emptied it, emptied it all, all the cockroach nymphs falling into the thick brew like snowflakes into mud, not sinking, but crawling, crawling on the surface, some swallowed whole by the craters of bubbles bursting open, thousands and thousands of tiny white cockroaches. They burned, the little cockroaches, catching on fire as they crawled over the mud-thick potion, disappearing, white flecks of ash on the black brew.

The witch turned to me. Some cockroaches, the blessed few, crawled their way up her hands, into the rags she wore. “Changed your mind?” She smiled with her yellow black teeth. I nodded. “A new curse. Drink,” the witch said, pointing with one dry finger to the cauldron.

The house was dark, my mother at her work. I made my way to the kitchen, bumping into walls and furniture, my hands in front of me. I pulled a plastic bag from under the sink, took off my clothes and put them in the bag. Ghost cockroaches crawled all over my skin. I wrapped the lump of clothes in a second layer of plastic, putting a knot in it tight as I could. Three layers. Another plastic bag. Three layers of plastic bags. Three was a good number, a witchcraft number. It tightened the bag shut before dropping it in the garbage bin outside. I took a shower, scrubbed my skin raw. I microwaved leftovers my mother left for me, standing over the laminated counter-top, my fingers in the tomato-stained Tupperware.

I went through the day gliding, one hundred miles away from my skin, gliding through school corridors, to and from classes, classes I couldn’t remember or hear. Gliding through the corridors, I saw him, far away, looked in his eyes, and blinked three times for witchcraft. He fell to his knees coughing, choking coughs from deep inside him, cavernous, like he was hollow. Turning red, he coughed and coughed and coughed and coughed, a crowd of students forming around him. All I saw was a little bit of black hair, falling down. I elbowed my way through. Choking still, his head, turning purple, on the floor, in a puddle of his bile. I turned him over so he could breathe. His neck was pulsating, vibrating. A lump visible in his throat. Much bigger than his throat, moving up, up, with each pulse, moving up, so much larger than his throat. His mouth fell open. Past the uvula, I saw something white, and pulsating. He wasn’t breathing. I had to help. I put my hand in his mouth, far as I could, reaching for the thing, my fingers slipping on it, not gripping. Tried again. It slipped, it slipped but I held on, and I pulled. I pulled with each pulse, pulling, and pulling on the white thing, pulling out with each pulse the thing from his throat.

He was like emptied out, deflated, his jaw unhinged and broken open from the thing in his throat. Next to him, a sack, a sack of white membrane, pulsating, palpitating, full of life.With each pulse, growing, stretching, the membrane thinning. But not tearing. I had to help. I crawled closer to the pulsating sack. With my hands I tried tearing, stretching the film, but it wouldn’t, wouldn’t give. My hands kept slipping, the membrane wet with bile. I dug my nails in. Clawed it open, ripping it, shredding the wet film.

It gushed full of fluid, sweeping me in its wave. It was putrid. I was soaked. I wiped the fluid from my eyes, clouding my sight. The sack was torn open. Not pulsating anymore. White, covering something like opaque shrink wrap. I peeled it off, peeled off the film, peeled it from the face. She looked like me. Delicate as I could, I wiped the mucus from her face, dabbing gently, gently, on this skin like mine, wiping the fluids from her eyes, her nose, turning her so she could breathe. “A witch is born,” said the witch, her hand warm on my shoulder. Gently, I cleaned the woman, cleaned her skin, babbling it gently, just her, the witch, and me, in the corridor, warm, warm, under the glowing lights.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seahorse Caviar

It felt good to touch it. What was it? I traced the folds of skin, glistening pink in the bathroom mirror, dead centre in the middle of my chest, sprouting like a fleshy cabbage from my solar plexus. It felt good to touch it, glimmering ropes of mucus trailing my fingers when I pulled them away, away from whatever that thing was. Some kind of a skin infection? An infection wouldn’t feel this good, my hand, like compelled, continuing to finger the skin, my fingers running on the edges of the folds, feeling them reaching down, down, shivering down my spine. Some kind of skin tag? Obviously this was a problem. Not normal, exactly, not ideal, really. I pulled my t-shirt over my head, covering my torso. Only the cotton felt rough, distracting, chafing against the skin folds. I stopped my hands from reaching for them, the folds, again. It had to be some kind of skin tag. Or more like large, concentric rows of dozens of skin tags. Only skin tags don’t feel this good, do they? Through my shirt, I had started touching the folds again, studying them, the strange puzzle of flesh. Even through the rough fabric of my shirt, it felt good to touch it.

I’m not an idiot. I had to go to the doctor, a clinic, or something. I had some kind of weird skin thing on my chest, some kind of infection, maybe. But as diseases go, not so bad. It felt good to touch it. Walking down the street, I held my shirt as far away from my skin as I could. The rough cotton chafed against the sensitive skin. Plus it stopped me from reaching for them, the folds, again. There was a clinic I knew. They’d tell me what was wrong with me, the doctors. Strangers on the street looked at me, looked at me weird as I tugged at the hem of my shirt, keeping it away from my skin. They were staring at me, with their too many eyes on me, too visible, an ant on the pavement, dwarfed by the strangers. So I let go. But with every step I felt the fabric rubbing, rubbing, on the folds of skin. Only a few steps down the street, already, fluid from my skin seeped through my shirt, and the cotton chafed the skin folds raw.

“Human?” The nurse asked, looking me up and down with her protuberant eyes. “Yeah, human.” The waiting room chairs were too big for someone like me to sit in comfortably. If I scooted all the way back, my feet didn’t touch the ground, if I shifted forward, I couldn’t rest my back on the backrest. So I let my feet dangle. Made me feel like a child, too small, embarrassed. The burnt orange carpet looked like it hadn’t been vacuumed in a decade, under the fluorescent lights I saw scales and nail clippings. So maybe it wasn’t so bad my feet couldn’t reach. “Sex? Name?” The nurse asked with a click of her forked tongue. Her pen hovered over the intake sheet. Right. “Male. Afra Carbo.”

The doctor had thick, scaly skin. I saw the sharp triangles of keratin from where I was sitting, on the cold steel examination table. He was reading the intake sheet, his clawed fingers tracing down the sheet of paper. Not looking forward to those in me. Still. He was reading. It gave me a second to steady my breathing, looking at the ceiling corner furthest away from him. Here too, my feet didn’t reach the ground. He was done reading. I held my breath, staring at the ceiling. He stepped towards me, leaned in to look at the skin tag thing. His ridged forehead was millimetres away from my chest. I couldn’t breathe. I counted the tiles on the ceiling. One, two, three, four… Pulling surgical gloves over his clawed hands, he touched one of the folds, making me shiver. I gripped the edge of the table, my knuckles white, desperate to steady the spasm, ignore it, pretend like that didn’t just happen.

I was looking away as far as I could. He had his claws in my folds. I counted the titles. Eleven tiles across, twelve tiles down. With his gloved claws, he separated the folds of skin, examining beneath and between them, the latex gloves squeaking against my skin, each new unfolding sending another shiver through me. The skin was glistening, I saw it, I saw it glisten, but I looked away, I looked away, far as I could. He dragged his claw between two folds. I inhaled, sharp. Forced myself to cough, like I had choked or something. One hundred and thirty two. Eleven times twelve is one hundred and thirty two. One hundred thirty two tiles on the ceiling. “Could be some kind of a skin infection,” he said, peeling off his gloves and throwing them in the garbage bin. “It doesn’t hurt, you said?” I put my shirt back on, holding the fabric away from my skin. “Uh, no, no, not really.” He shrugged. “I could refer you to a dermatologist. Dr. Maior. Specializes in humans.” He scribbled something on a piece of paper, handing it to me. I took it and ran.

Dr. Galo Maior’s office was nice, nicer than the clinic. Everything surface was polished clean, beige and blue and stainless steel. Some of the chairs were human-sized. She’d tell me what was wrong with me, Dr. Maior, she would. I could feel it in the lemony scented air. Clean. Cleaner than the clinic. Plus she was human, Dr. Maior. “And you said this appeared quite suddenly?” Laying on the examination table, I tried raising myself to my elbows, but slipped on the slippery plastic. “Yeah, like, about a week ago?” Dr. Maior was probing the flesh circle. I counted down from one hundred and thirty two, holding back shivers, gripping the edges of the table. No tiles on this ceiling. She slipped her hand in. In? I looked down at Dr. Maior. Her hand was in my chest, up to the wrist. Her hand was inside me, inside me, I felt it move, pushing into my flesh, her hand, her fingers unfurling, stretching, inside me. “That’s unusual,” she said, looking up at me, her eyes wide. She unstuck her fist from my thorax, a shiny rope of fluid trailing behind her hand. I fell back onto the table like a weight lifted from me.

“I’m not quite sure what to do here,” said Dr. Maior, wiping her gloves off. “I can tell you, it doesn’t seem to be a dermatological issue, I’d say it goes a bit deeper than that.” The hole was new. I told her the hole was new, yesterday that thing, whatever it was, was a weird bunch of skin, but the hole was new. She shrugged. “I don’t know what to tell you. It’s not like any skin infection I’ve ever seen. But you said you’re not in any pain, are you?” She was right. I wasn’t in any pain. I felt great. I felt fantastic. Like nothing I’ve ever felt before, elated, effervescent. Something harmful wouldn’t feel this good. I still felt it. Still felt like a ghost of her hand unfolding under my ribs, pushing inside my flesh. I wasn’t feverish. I wasn’t sick. I felt great, really, I felt fantastic. Only there was a hole in my chest, apparently. But it felt good to touch it. My doctor had put her hand in there, she put her hand in me, and it felt great. Dr. Maior said something, something about another refereall. Only I didn’t hear, not really. I was thinking of her little hand pushing inside me.

Home. The hole in my chest had dribbled through my shirt. Running home, I covered it with my arms, but I could tell, I could tell strangers on the street were staring, staring at the wet spot blooming on my chest. I locked the door behind me, locked it again. No one would come in. No one could see me here. Free from their probing, protuberant eyes, I took my shirt off. It was ruined. Filthy. My hole was leaking, fluids running down my stomach like a syrupy clear river. I balled up my shirt. It was ruined anyways. Stuffed it in the chest hole. I felt it in there, but it didn’t hurt, it didn’t, it just felt full and dry. Shirtless, pacing my apartment, I felt every breeze, every small gust of wind in the folds of my skin. It was alright. It was alright, it didn’t hurt, with a shirt in it, it didn't leak. It was fine, I was fine. It was mine. It felt good to touch it, my hand rubbing circles on my chest. I paced the length of my apartment. I was fine. I felt great. It felt good to touch it.

With my shirt in the hole, I went about my day. It didn’t leak, it didn’t hurt. I was fine, this was fine. Only, the pink skin at the centre of the folds flushed red. Looking at it in the mirror, looking at the circle of skin flushing red, swollen and full, I pulled my shirt from the hole. It was soaked through, heavy with the fluid, landing in the bathtub with a wet thud. It started leaking again, a waterfall of syrupy fluid running down my stomach. Not ideal, that. A towel, maybe a towel would do. I took one, a ratty old one hanging from the door frame, balled it up and jammed it in my chest cavity.

So it was getting worse. I had to change the chest hole stuffing twice a day, change them, wash them, dry them, pack it back in my thorax. So it was getting worse, the colour of it blooming to a wine dark red. But why would I go to another doctor? Have them touch me, put their hands in me, while I struggled to steady the spasm, to stop the shivers running through me, laying cold on their examination tables, as they pried me open like a can of tuna. And for what? They couldn’t tell me what was wrong. They couldn't tell me what was wrong with me. All they did was put their hands in me. It felt like a violation. Worse. It felt good. Dr. Maior’s little hand felt good in me. Made me shiver. So I couldn’t go to the doctor. But It was fine. All I needed was to change the towel again, pulling it out of myself, again and again, wet and heavy, letting the hole breathe, breathe, and leak.

I was touching it now. So what? It was mine, the concentric circles of folded skin, a dark red eye, the leaking, oozing, it was mine. I felt it down my spine. Running my fingers through the folds. It felt good. I slipped my hand in, saw it disappear, sinking in the flesh of my hole. Wrist deep. Elbow deep. I was feeling for the end of it. It felt good, my fist moving through me, pressure pushing in the flesh. There was no end to it. My fingers touched only the void, useless. There was no end to it. A tunnel of flesh, endless, endless, it swallowed my hand, it swallowed my arm. There was no end to it. But it felt good to touch it. I felt it in my spine. I took my hand out, glossy slick with mucus. It felt good. Maybe that’s all that mattered. It felt good. I pushed my hand back in, in the mirror, I watched it be swallowed by the skin, swallowed by the folds.

It was resonating, booming loud, mucus flowing with renewed vigour, cascading down, until the bathroom floor was inches covered in crystal clear liquid, liquid oozing from me, oozing from the hole in my chest. Humming, resonating, I felt it in my bones, my ribs rattling with the sound of the hole, I heard it, I heard it, it sounded like a song, the folds of my skin, humming, it sounded like a song, like a bullfrog mating call, like the skin of a drum being hit, reverberating on the tense dancing skin, when I pushed my hand out and in, from the hole in between my ribs, out and in, from the folds of my skin. I took my fist out. It sang louder, louder, the empty hole amplifying the sound. It was calling, calling, using me, my ribs, my hole, to call, to call for something. But it felt good to touch it. And that’s all that mattered. I pushed my fist back in.

It wouldn’t stop singing. I lay exhausted on the bathroom floor. It wouldn't stop leaking either. I was wet and covered in sweat. And the hole wouldn’t stop singing, and the bathroom floor was cold and slippery, and I couldn't get up again. The skin folds were full, painfully gorged, red, distended, reverberating with the hole’s humming. It kept singing, it kept calling. It was beautiful. I was tired. I couldn’t go outside. Not like this. Not with the hole singing in my chest. I reached my hand up for a towel, I’d make it quiet. Even with the towel between my ribs, the hole still sang, barely muffled. Another one. Still it called, singing. My hands shaking with exhaustion, I ripped my shirt to shreds, wrapping it harsh, tight, over my ribs, tight until it hurt, tight until I struggled to breathe, but the hole was quiet, quiet, finally.

On the outside I flowed with the rivers of strangers, on the inside, I had towels balled up in my chest to muffle the hole’s song. I flowed with the rivers of strangers, strangers in their shimmering red, green, black, blue scales, like jewels, I’d follow them, I’d follow them, so small among them, they couldn’t tell, I was one, part of them, the glittering, shining river flowing from stop light to stop light. They couldn't tell. Deaf to the sound. Blind to the hole, seeping through my shirt, so long, so long as I kept close, kept close, part of the river, one drop flowing with the whole. Only I had a hole in me. Close, touching me, their scales touching my skin, touching me close, blind to the disease blooming on me, in me, deaf to the sound of the hole singing.

The strangers in the river poured into an opening, an opening past the street, thinning themselves out on a plaza, a plaza of black stone polished to a shine, pillars and plateaus of the same black and shining stone. The river emptied itself of its people, throwing them to all corners, until I was alone, dwarfed by the pillars and plateaus, polished black and shining, dwarfed by the tall, reptile strangers, alone on the black stone. My hole started humming, loud, louder than ever, I covered it with my arm, muffled it, best I could, but still, it screamed louder, screeching. The strangers turned their frog’s eyes towards me, yellow and bulging from their rough and scaly faces, pointed their black clawed fingers at me, laughing, laughing, baring their black teeth, black tongues, laughing at me, laughing at the hole singing in my chest, with their hyenas’ cackle.

I locked the door behind me, I locked the door again behind me, the hole was screaming loud, loud, I pressed my hands over the skin folds, hard, still, it wouldn’t quiet. Knocking came from the door. I was on the floor, my arms around my chest. Another knock on the door, impatient. Through the peephole, a brown eye looked back at me. Brown. Human. I cracked the door open. “Can I, uh, help you?” I asked through the crack, not seeing my interlocutor. I received no answer, the door was pushed open and a small figure pushed the door open into my home.

She was a head shorter than I was, and everything about her was brown. “My name is Opilio Flammen,” she said, punctuating it with a grand flourish from her hands, “could you get me a glass of water? I’m thirsty.” I pressed both of my hands firmly over my chest, the hole seeping through my shirt, looking down at her, for a second, a minute, maybe. “Could you get me a glass of water? And you should really have one too, I think,” she told me. I got one for her, I didn’t know what else to do, still holding one hand over my wet shirt. Opilio walked to my living room and I followed her. She sat on my couch, drank the water, set the glass down on the coffee table, propped her feet up, and looked up at me, me, standing in front of her, leaking fluid spilling from my chest onto the floor, trying desperately to hold it back with both my hands over the hole.

Opilio looked at me, scanning me, like, and it felt like hours. I was still leaking all over the floor. “I followed you because I heard it calling.” She pointed at my chest, at me, me, struggling to keep the fluids from spilling between my fingers. “I have it too.” With this, she reached over her head and pulled off her shirt; in the middle of her chest, between her breasts, there was a hole like mine. Darker, even, the folds of skin on her chest the purple color of a bruise, something white and humid poking out from between the circle of skin folds. She, too, had plugged her chest hole with a bath towel. She stood tall, I stood hunched, she told me, “now show me yours.” My hands hesitated. If I let go, the chest juice would gush out of me, I knew it, and the hole would start screaming again. So I hesitated. Opilio saw that, I thought, her features softened, and she stood up, walking over to me.

“It doesn’t hurt, right? It doesn’t.” She took my hand and with it, made me pull the towel from her chest, heavy with fluid, pulling it out of her like a coiled rope, a rope coiled beneath her ribs. I held it with both hands, the towel was so heavy. Without it, she was leaking too, dripping, all over the living room floor. Her hole was humming, I saw the skin folds tense up and pulsate with the hum. Mine was singing too, muffled, quiet, but calling, calling me to hers. I dropped the towel. She took my hand with both of hers. Placed it on the folds of her skin. I felt the skin tremble, reverberating, under my palm. She held it there, my hand flat on her chest, pressed it against herself, shivering, her eyes closed, for a minute, before slipping her hands to the hem of my shirt, pulling it off from me. Her hands were on my chest, her fingers slipping beneath the folds of my skin, to the cavity, I helped her drag the towel out of me, dropping it on the floor with a splash.

Bare chested in front of the other, feet deep and slipping on the ooze dripping from the both of us, our holes humming, I stood in front of her and her in front of me. I took her little hand and pushed it inside me, slid it beneath the bones of my ribcage, felt it expand next to my heart, next to my spine, touching them with the tips of her fingers, pushing, unfurling, inside my skin. My hand went to her chest, her eyes closed, I felt her hand shiver in me when I traced the contours of her skin folds, tracing them gently, barely touching them. Didn’t want to hurt her. Her frame felt so small under my hand, my hand flat across the bones of her ribcage. She withdrew her arm back from my chest, I felt the loss of her acutely, my chest barren of her, but she took my fist with both her hands, and pushed it inside herself. I felt the inside of her warm and wet and endless like mine was. It was warm, it felt good. Opilio drew my fist deeper inside her, up to the elbow, her grip firm on my arm, before pulling it back out. In my hand, I held her eggs, black and shining spheres, covered with mucus. I stared at what I drew from her. Eggs. She, too, hesitated, if only for a second. Gently, she closed my hand over her eggs, together, we placed them into the hole inside my chest. They fit neatly inside me, still warm, sliding down me, from the heat of her body.

With her own hands, both of them inside herself, Opilio drew more eggs from her hole, the skin folds of her chest taunt with a bullfrog song. She passed them to me. Pushed her little hand inside me, full of her eggs. Again and again. I welcomed them inside me, warm, filling me, feeling heavy. And heavier still as she slipped another handful of eggs down the opening in my chest, covered in sweat and covered in fluid, shivering at the touch of her fingers inside my skin, Opilio filled me with her eggs, filled me until I was bursting full, full of her eggs, heavy and warm.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crocodile

He came to me in the shape of a crocodile, laying next to me, next to my skin, in his scales of keratin. The bed buckled, bent in two under his weight, the weight of a crocodile. Sinking down the middle, down the middle of the bed, I sank under him, under the body of the crocodile. I put my mouth to the mouth of the crocodile, felt the teeth of the crocodile, felt the tongue of the crocodile, felt the breath of the crocodile, and sank, sank, down under the weight of the crocodile. With each breath into the lungs of the crocodile, I felt his keratin skin dance next to mine, up and down, sinking down dancing under the scales of the crocodile.

In the morning I washed my bed sheets. Balled them up and threw them in the washer. Didn’t like the white of them. I’d dye them green, I’d dye them red. Didn’t like the white of them. In the morning I washed my skin, scrubbed it like it was made of keratin. In the morning I made breakfast, and the oatmeal tasted of nothing. In the morning I went stalking, sulking in the meat department of the grocery store, staring, hungry, at the red, red meat in their little packages. This one would do. The styrofoam squeaked when I picked it up. Thirty percent off for quick sale. Crocodiles sometimes settle for carrion. And the crocodile woman would settle for thirty percent off beef. It was red. I piled cartons in the cart, lining them up neatly like little red soldiers.

I wanted to do this correct. I took the meat out of the pack, held it in my hands, cold and slippery. Crocodiles don’t chew. They use the muscles of their neck to slam their prey down, to pull and twist and tear the meat into ribbons. Then they swallow. But they don’t chew. Their teeth aren’t made for chewing, but for digging in flesh and holding it down. On the screen of my computer, a crocodile dragged a wildebeest underwater, its curving body slinking into the green, green Serengeti mud. A death roll cracked the wildebeest’s spine. Again and again, the muscles of its neck bulging, the crocodile slammed the beast’s body on the water, ripping its flesh into shreds, turning the green water red, and swallowing, its jaws turned to the sky like it would swallow the sun next.

I’d tear the meat with my neck like the crocodile did. Sinking my teeth in, I used my neck, all the muscles of it, slamming it against the counter top. Didn’t work. Again. Slammed the flesh against the counter, tearing a chunk from it. Too big for the mouth of a human. But not for the crocodile woman. Raising my jaws to the sky, I swallowed it. I choked. Coughed. Couldn’t breathe. Panicked. Coughed harder, harder. Couldn’t breathe. My face on fire. Coughed. Expelled the chunk. Covered in wet and throat mucus. I wiped my face from drool and tears. The meat wouldn’t go to waste. Crocodiles eat carrion. Again. I tried again, swallowing the chunk whole like a crocodile would.

I scrubbed the counter clean, clean of blood and bits of meat, clean of spittle and snot, I scrubbed and scrubbed. I made the bed with the dyed bed sheets, splattered green and red with dye. Pulled the bed sheets tight, tight over the mattress. I washed my skin, I ate raw meat, I lay in bed, I closed my eyes. He came to me again in the shape of a crocodile, laid his scales next to my skin. Holding me under the weight of his scales, he spoke to me, the crocodile, he told me what I had to do, the crocodile. He whispered in my ear, his breath warm on my skin, as he held me there, claws gripping, digging, between my hair, he told me there, what I needed to do. He talked to me, the man of crocodile, I felt each word digging, clawing, in my skin, I stretched under the words of the crocodile, every fibre of me to its fullest extent, under his crocodile’s speech.

In the morning, I washed the bed sheets, red and green and soaked through. Crocodiles live in the water, in muddy rivers, mangroves, and brackish coastlines. I’d do what the crocodile told me. But first I washed the bed sheets, cleaned my hair, scrubbed my skin, ate meat, tearing it with my teeth.

On every screen, a crocodile. Documentaries. Footage from families on safaris. Didn’t matter. I sorted the videos by species, saltwater, freshwater, didn’t matter. I watched the crocodile slink back into the mud, propelled forward by his muscular tail, the ridges of scale on his back breaking the surface of the water. A close-up of his eye, wet, lubricated, slit. Greener than a jewel. Another shot. Crocodile and his prey. A wallaby, ripped to ribbons, thrashing in the water. The voice-over quiet, quiet, so I could hear the bones snapping and crunching, the water splashing. Another shot. Crocodile swimming next to a boat, matching its speed, easily, with each thrust of his tail, the slinking s-shape of the crocodile visible in the clear water.

Every screen needed its crocodile. On the television, one was splashing, dragging his meal down under water, drowning, drowning the zebra. On the computer, close-up of his open jaws, his peculiar tongue, white, at the back of his exsanguinated mouth, blocking water from entering his throat. A close-up of his teeth, sharp triangles jutting from his mouth, on the screen of my phone, my phone, in one hand, holding it to my eyes, laying on the bed on my other hand. His teeth. Watching it now, I remembered, I remembered what they felt like, grazing my skin, like he was here with me, his breath stealing mine, stealing mine with every inhale, with every exhale.

I washed my hands, all the videos, bright, blaring all around me. I had to do what the crocodile told me. I made myself ready, the crocodile crawling all around me, dancing on every surface, wading back into dark waters, pulling his prey apart, shredding them, on every surface. I wanted the crocodile with me. I wanted him in every pore. I’d buy a projector. All my walls would be crocodile walls. I’d have him on me, in me, every fibre filed until bursting, full, full of his essence, the essence of the crocodile. But first I had to do what the crocodile told me.

I’d do what the crocodile told me: I’d hunt for him. The man followed me home and sat himself on my couch. I plugged in the projectors, making crocodiles of the both of us. The man said nothing, nothing about the crocodiles, just sat there, rolling something, the elbows of his leather jacket squeaking with each movement. In mortal peril, crocodile lurking below the surface of the muddy water, the man was rolling a joint. I had to do what the crocodile told me. Only I felt myself shaking, like some kind of leaf, pathetic. The man said something, only, I didn’t hear, not over the sound of my heart beating in my ear. He made a gesture. Invited me to sit on my own couch in my own home.

What the crocodile told me to do, I’d do it. Standing in front of the man, I traced the stubble, vile stubble of the hairy mammal, of his neck, the skin of it pink and sagging. My mouth flooded with bile. This wasn’t the skin of a crocodile. But I’d what the crocodile told me. Finger and thumb under the man’s chin, I made him look at me. Brown, doe-eyed, a smile pulling over his tombstone straight teeth. I dug my crocodile claws in his skin, paper-thin. He only smiled wider, the vile little man, with his own hand, took mine, took my hand, the free one, the one not digging red into his skin, and placed it in his salt and pepper hair. Mammalian hair, in the hands of the crocodile. I twisted my claws in the long strands of his hair. Yanked his head back. Hoped it hurt. Hoped it hurt the vile little man. But he only smiled wider, showing off more of his rectangle teeth, his neck bent, exposed, at the Adam's apple.

Smiling, shoulders wide, his neck exposed, his hair tight in my fist, behind him, on the wall, a crocodile dragged its prey underwater, thrashing it against the rocky shoreline, still, still, the antelope fought, slipped away, was caught again in the relentless jaws of the crocodile. But not him, not this prey. Every line of the man’s face wrinkled deep with his grin. A shit-eating grin. I moved my hand to his throat, warm, stubbly, under my palm. He was laughing, laughing at me. I couldn’t reach, not with the one hand, couldn’t circle his throat. Useless, useless little hands of a little mammal.

He was laughing. He was more of the crocodile than me. Still, still, I’d hurt him, I would. With my palm I pushed down, down on his Adam’s apple, I’d push it back where it came from, his vile, horrible little protuberance. I’d rip his hair out, gripping the strands in my fist, I yanked his hair back, hoping his neck would break. I’d dig his eyes out with my thumbs. He was laughing, laughing at me. I’d kill him. The man picked my hands off him like two bugs that were bothering him, holding the both of mine in the one of his, his grip painful tight on my wrist. The man was of crocodile, the man was of crocodile, scales under his skin, his brown eyes slit down in the middle, the man was of crocodile. He laid me on the couch, and I went under him, under the weight of a crocodile.

My nails were itching, the bed of them red and inflamed. I chewed on the index. Anything for relief, relief from the itch. It worked, it did. Only the nail came off, hanging on the nail bed by a filament, a filament shining with spittle under the fluorescent light. Relief flooded me, making me warm. All of them had to go, all of them had to go, all of the nails. The man knocked on the bathroom door. Said he had to go. Whatever. His bladder meant nothing to me. It was morning and he hadn’t left. I chewed on the next nail, it came off too, hanging on the bed by a thread of skin. Eight more to go. The man knocked again. Fine. Fine. I’d continue in the kitchen.

The couch stared at me. For obvious reasons, I couldn’t throw it in the washer. The light of the projectors was thin, dwarfed by the light of the morning sun, washing everything gray. Washed out crocodiles on every wall. Still, I had to do something about the couch. Another nail fell off its bed, chewed to the flesh. The man came out from the bathroom, his hands were dry. Vile little man, vile, vile, little man, who was more of the crocodile than me. Words came out of his mouth, something about breakfast. I had more pressing issues. The couch needed to be cleaned. Nails needed to be chewed, seven of them still to go. Somewhere, I had a spray bottle, a spray bottle, some cleaning products, a rag, I’d clean the couch, I would. The couch would be cleaned.

More noises from the man. He had the fridge door open. All that was in there was discount meat. Ha. Not much of a crocodile, if he balked at the idea of eating discounted beef. Bet he couldn’t eat it like a crocodile, either, couldn’t tear it with his neck. I told him crocodiles sometimes eat carrion. This was my carrion. He shrugged, laughing. If I could kill him I would. But he had the crocodile with him, dancing around him, black scales in the muddy water. Another nail fell. Six to go, six nails, and four empty red beds. Chewing on my fingernails, I stared at the man. Still, he was smiling still, pulling a mocking grin over his straight teeth.

So he wouldn’t leave, and I had nowhere else to go. I’d abide by the rule of the crocodile. The strongest rules. He sat on the couch, rolling something. This again. Well, I’d be in the bathroom, picking my nails off their beds. One after the other, I lined up my nails on the sink, lining them up like little red soldiers. Nails were nothing. I needed claws. I needed scales. In the mirror, my skin was pink and soft, with one finger I poked it, and it dented in like dough, dimpled. Underneath, there were scales, they were there. But I had to get them out, I had to draw them out, draw the scales under my skin out, out, somehow.