Text

"...divos pater atque hominum rex..."

Vergil's description of Jupiter, Aeneid 1

0 notes

Text

Itaque distantia partium virtutem agendi debilitat, molis amplitudo retardat motum, crassitudo penetrationem corporum impedit... Quapropter cum tres esse debeant perfectae actionis conditiones, corpus aut habet tres alias illis adversas aut unam illarum accipiendo, non accipit aliam. Oporteret quippe brevitatem simul habere, levitatem et raritatem. Quae quidem tria ad incorporalem quendam habitum corpus ipsum reducunt, ut omnis agendi virtus sit ad naturam incorpoream referenda.

Marsilio Ficino. Platonic Theology, I.2.2 (pg. 18). Editor James Hankins. English Translation Michael Allen. HUP: 2001.

0 notes

Photo

Fra Angelico. The Annunciatory Angel. Tempera and Gold Leaf. 1450-5.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Damascius also points out that 'reversion' is ambiguous between something's achieving its own definition from an inchoate state, and something's returning to a higher source or to its cause.

Sara Ahbel Rappe. Prolegomena to Damascius's Problems and Solutions Concerning First Principles. OUP: 2010, p. xx.

#sara ahbel-rappe#damascius#problems and solutions concerning first philosophy#imperial platonism#modal ontology

0 notes

Text

...του^ μη' ό'ντος ε'φιέμενοι του^ κακου^ ε'φίενται.

...attending to not beings, [the demons] attend to evil.

Pseudo-Dionysius. Divine Names IV.34 733D. Quoted in Perlman, Theophany, ch. 4, pg. 60.

#i can be your angelology or your demonology#divinity and theology#evil and negation#pseudo dionysus#imperial platonism#ontology#eric perlman#theophany

1 note

·

View note

Text

But whereas Proclus finds evil, as deficiency, only at the level of human souls and of natural bodies, Dionysius uses this procedure to explain, on the one hand, that evil is no positive reality in anything and, on the other, that it can occur as a deficiency of proper perfection at any level of being whatsoever. Thus he argues that evil is no reality in angels (DN IV.22, 724BC); in demons (DN IV.23 724C-725C); in souls (i.e., human souls) (DN IV.24, 725D-728A); in irrational animals (DN IV.25, 728B); in nature as a whole (DN IV.26, 728C); in bodies (DN IV.27, 728D); and in matter (DN IV.28, 729A).

Eric Perlman. Theophany. Ch. 4, pg. 58.

#eric perlman#theophany#divinity and theology#proclus#plotinus#pseudo dionysus#imperial platonism#evil and negation#ontology

0 notes

Text

Constant capital and variable capital in Volume 1 do not refer to hypothetical quantities of money capital, which are assumed to be equal to the values of the means of production and means of subsistence (as in the standard interpretation). Instead, constant capital and variable capital in Volume 1 refer to actual quantities of money capital, which tend to be equal to the prices of production of the means of production and means of subsistence, although prices of production cannot be explained in Volume 1, because prices of production have to do with the distribution of surplus-value; and before the distribution of surplus-value can be explained, the total amount of surplus-value to be distributed must first be determined--this being the main task of Volume 1.

Fred Moseley. Money and Totality. Brill: Leiden, 2015. Ch. 1, pgs. 7-8

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 'transformation problem' is usually conceived as a transformation of individual labour values to individual prices of production. But that's not what Marx's theory of prices of production is about; Marx's theory is about the transformation of aggregate price to individual prices of production and the transformation of the total surplus-value into its individual parts. The standard interpretation misses entirely the all-important macro aspect of Marx's theory and logical method, and the logical priority of the total surplus-value over the individual parts.

Moseley, Fred. Money and Totality: A Macro-Monetary Interpretation of Marx's Logic in Capital and the End of the 'Transformation Problem.' Brill: Leuden 2015. Ch 1, pg. 6

#fred moseley#political economy#marxism#positivisms and mass society#analysis and causality#price theory#the transformation problem

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Albert Burgh, a former student (who later converted to Catholicism), asked him how he knew his philosophy was the best one, Spinoza answered: "I d9 not presume that I have found the best philosophy. I know that I understand the true one."

Hampe, Michael, Ursula Renz, and Robert Schnepf. Introduction to Spinoza's Ethics: A Collective Commentary. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History 196: Leiden (2011), p. 1.

#Spinoza#stoicisn#methods of the philosophers#divinity and theology#early modern philosophy#early modernity

0 notes

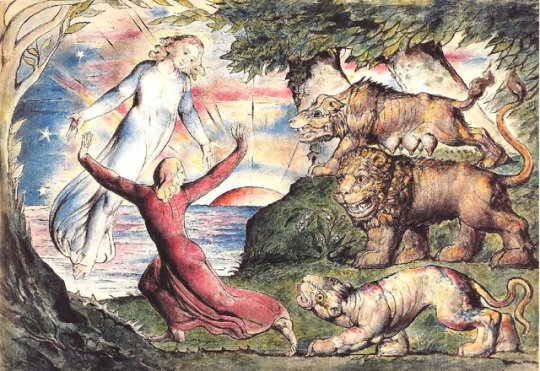

Photo

William Blake. Illustration of Inferno I. 1826-27. WikimediaCommons

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whatever role they may have played the American War of Independence, the weapons of an insurgent crowd--especially pikes--had long been recognized in England as the ideal arms for rebels, and particularly urban rebels such as the ones we see in Blake's prophecy: the only effecfive means my which untrained but determined militiamen could resist a regular army's heavy cavalry without firearms, for the simple reason that pikes do not require much training to use, and cavalry horses will not charge into a thicket of well-placed pikes.

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chapter 2 p. 47

#praxis#saree makdisi#william blake and the impossible history of the 1790s#william blake#poetry#radicals and their discontents

0 notes

Text

...the artisan radicals ended up in an impossible situation, articulating the position of a class that they did not belong to--largely because it pertained to a modern social formation in which the figure of the artisan would be altogether anomalogous--while at the same time disassociating themselves from a class that they thought of as "below" them, when in fact they were about to be absorbed into it.

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chapter 2 p. 27.

#william blake#saree makdisi#william blake and the impossible history of the 1790s#literacies and class warfare#radicals and their discontents#positivisms and mass society#poetry#arts and crafts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

However, the recent scholarly emphasis on the heterogeneity of 1790s radicalism, and on the extent to which popular enthusiasm could be combined with secular rationalism in a pungent revolutionary blend, should not prevent us from discerning the presence of a strand of radicalism that sought to rise above the fray and to assert its own legitimacy, partly by making its own claims on "respectable" political discoursw, partly by denying, excluding, and disassociating itself from other forms and subcultures of radicalism (which it regarded as inarticulate, unrespectable, unenlightened, and hence illegitimate), and partly by working to assimilate as many grievances as possuble into its own agenda for reform, rearticulating them when necessary--and thereby exercising, in effect, a form of hegemony, albeit one whose dominance was still very much in question at the time and would fade altogether amid the deepening crises of 1796-97, only to return early in the nineteenth century. This strand of radicalism enjoyed the allegiance of many of the best-known intellectuals as well as relatively broad-based popularity among the artisans class whose members constituted the core of London's radical culture.

Saree Makdisi. Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chapter 2 p. 21-22

#william blake#radicals and their discontents#positivisms and mass society#bourgeois politics#literacies and class warfare#saree makdisi#william blake and the impossible history of the 1790s

0 notes

Text

For Blake can be seen to locate the foundation of bith his aesthetics and his politics, as well as his sense of being, in desire, which was taken to be the great scourge of the radical culture of the period, the morally virtuous self's means of differentiating itself not only from passionate Orientals but also from the unruly mob and decadent aristocrats.

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790's. Chapter 1 p. 7

0 notes

Text

Jesus, Blake writes, "supposes every Thing to be Evident to the Child & to the Poor & Unlearned Such is the Gospel."

For, he adds, "the Whole Bible is filld with Imaginations & Visions from End to End & not with Moral virtues that is the baseness of Plato & the Greeks & all Warriors The Moral Virtues are continual Accusers of Sin & promote Eternal Wars & Domineering over others."

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790's. 4

0 notes

Text

...much modern scholarship has also...identified Blake with the champions of an emergert modern consumer culture, which, through the rhetoric of rights and choices, shared the key conceptual and philosophical assumptions of the radical discourse of liberty (primarily the celebration of the secular freedom of the sovereign individual) and would in fact prove to be inseparable from it.

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790's. 3

1 note

·

View note

Text

Indeed, it seems to me that the overriding emotions in Blake's work are not bitterness and resentment, but rather love and joy...

contemporary scholarship is in a much better position to address the theme of despair in 'London,' or the theme of exploitation in either of the chimney sweeper poems, or even the theme of revenge in A Poison Song, which is actually quite anomalous in Blake's oeuvre; and it finds itself all but stripped of the critical capacity and the conceptual language with which to make much of the joys and desires of The Garden of Love or Ah! Sun-Flower or A Little Girl Lost, or Oothoon's cries of "Love! Love! Love! happy happy Love!" in Visions of the Daughters of Albion.

Saree Makdisi. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790's. University of Chicago Press: London, 2003. xiii

1 note

·

View note