Text

Superlative objects and technological dreams

Thanks for tuning in - it’s been a while.

Since the last post Crap Futures has left the island of Madeira, it seems, for good: Julian to Breda in the Netherlands and James to Paris. Shifting from the vast expanse of the quinta overlooking the open Atlantic to confinement in our small urban apartments under numerous lockdowns may have stymied our ability to write … but finally here we are. The following words emerged from a rejected conference paper (where all good ideas are born) and aim to provide another analysis on the state of the design industry today.

What follows is a (very) potted Western history of the designed object, or more specifically the superlative object - and an argument that the placing of such high cultural value on the object allows the systems and resources behind its realisation (the means) to be largely taken for granted.

This elision gives mainstream design an enormous advantage over alternative approaches, as all the available methods and means - global resources, neo-liberal labour practices, highly sophisticated manufacturing and marketing methods, intricate supply chains and the latest technological advances - can be exploited to achieve the celebrated end. How can more ethical or ecological design processes compete - when only the end product, the superlative object, is valued?

What do these terms mean? Let’s take a closer look.

The superlative object

In Mythologies Roland Barthes introduced the notion of the superlative object through the example of the Citroën DS. Cars, he argues, ‘are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists’. Commenting on the seamless perfection of the vehicle, he compares it to the ‘unbroken metal’ of science-fiction spaceships and even to the smooth and seamless robes worn by Christ. Barthes’ emphatic words anticipate the status objects of today. Seams, he argues, reveal the hand of the (human) maker, therefore suggesting that the DS is beyond human – an immaculate conception.

Our history of the superlative object begins in France during the 19th Century. Redgrave’s Manual of Design from1890 provides a rigorous examination of the superlative objects of the period, tracing their origins back to the establishment of the ‘royal manufactories, the tapestry and furniture works of the Gobelins, Beauvais, and Aubusson ... in these works the most skilled workmen, aided by the most scientific men of the age, executed the designs of the first artists of France’ (p. 4). Redgrave’s manual and the essays of his father that preceded it were largely written in response to the great exhibitions of the mid-19th Century, in London (1851) and Paris (1855). The original intention of the French exhibition was to honour the prototype builders - designers, craftsmen, and workers - through the various displays in the Palais de l’Industrie (Poisson, 2005). Whilst these displays were ‘often products of an impeccable, at times even virtuosic technique, they nevertheless formed part of an occasionally redundant, profoundly eclectic and overabundant decor ... which had been misappropriated in the name of ornament worship’ (p. 4).

This analysis of the superlative object is supported by Redgrave who is even more damning of the French tendency towards the meretricious: ‘the world is still deceived with ornament’, he suggests, ‘and led astray by pretentious display, instead of advancing in the road to real excellence’.

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged from an attempt to reform design and decoration in mid-19th century Britain. It was a reaction to the pretentious displays seen in the great exhibitions of the period. Redgrave insisted that ‘style’ demanded sound construction before ornamentation, and a proper awareness of the quality of materials used. ‘Utility must have precedence over ornamentation' (p. 15).

Machines and making

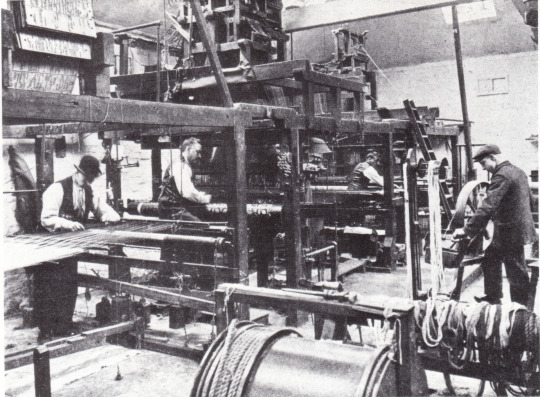

In the late 19th Century debate began to grow about the relationship between designing and making. For some key figures in the Arts and Crafts such as John Ruskin and Walter Crane, the making of an object should happen totally under the hand of the designer, while others (including Morris) believed that mechanisation was not negative in itself, and machines used well could improve the quality of the designed object.

This argument was played out in a discussion between Crane and the early industrial designer Lewis F. Day:

W.C. ... I presume you would admit that a designer is all the better for a first-hand acquaintance with the conditions, necessities and limitations of the work for which he is designing.

L.F.D. Certainly; but it doesn't follow in the least that he should execute his design with his own hand.

W.C. How then would a designer obtain his first-hand acquaintance with a method or material unless he had actually worked out his own design in that method or material?

This was perhaps the last true period when designed means and ends existed in an unbroken continuum; when design was considered as a social justice movement as much as an aesthetic one. The last line from Lewis F. Day is quite remarkable when viewed from today’s perspective - that a designer would do all that he designs.

This brief history will now move across the Atlantic because the version of design developed there during the 1930s, in many ways, represent the true genesis of the version of design that dominates today.

Building on the ideas of the more progressive members of the Arts and Crafts movement, the ex-set designer Norman Bel Geddes described an approach to design that completely incorporated the manufacturing process, advocating that the designer should ‘visit the client’s factory and determine the capacity and limitations of the machines and workers’.

As the century progressed the capacity grew exponentially whilst the limitations of the workers were increasingly bypassed by sophisticated machinery and automation.

Industry and spectacle

Bel Geddes was also one of the pioneers of the influential movement Streamline Moderne. Here he describes the potential elevation of the industrial object to the superlative:

When automobiles, railway cars, airships, steamships or other objects of an industrial nature stimulate you in the same way that you are stimulated when you look at the Parthenon, at the windows of Chartres, at the Moses of Michelangelo, or at the frescoes of Giotto, you will then have every right to speak of them as works of art. Just as surely as the artists of the fourteenth century are remembered by their cathedrals, so will those of the twentieth be remembered for their factories and the products of these factories.

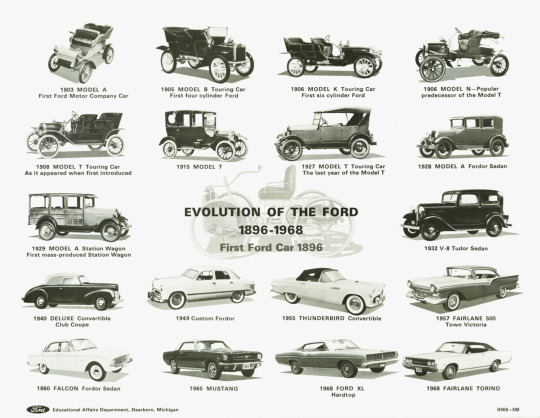

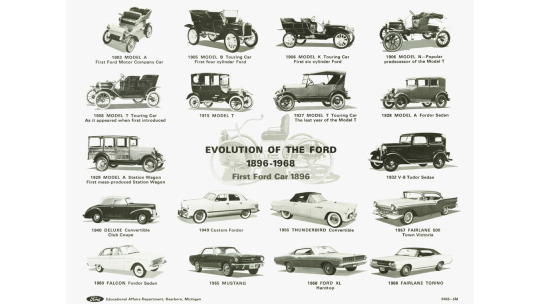

The invention of the internal combustion engine at the beginning of the century had transformed the way Americans moved around, but by the mid-1920s the US car industry had reached saturation point. Alfred Sloan, the boss of General Motors, came up with a plan to keep people buying new cars. He introduced annual cosmetic design changes to convince car owners to buy replacements each year. The cars themselves changed relatively little in their essence, but they looked different.

This created the new role of the consumer - and with it the growth of public relations and advertising. As Bel Geddes suggested in 1932: ‘the artist’s contribution touches upon that most important of all phases - entering into selling the psychological. He appeals to the consumer’s vanity and plays upon his imagination, and gives him something he does not tire of’. Cars became symbols of progress and objects of status. J. G. Ballard provides a wonderful cultural critique on this subject:

youtube

Towards the end of the 20th Century (in The Society of the Spectacle) Guy Debord stated that: ‘in societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.’

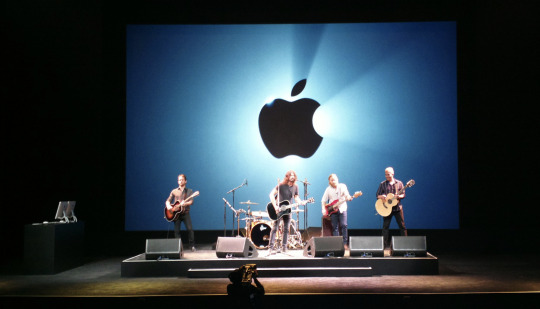

It is impossible, for example, to separate an Apple iPhone from the brand, its marketing, and the global fanfare that surrounds the launch of a new Apple product. This focus on seamless design, on the spectacle, on the superlative object, has (to paraphrase Albert Borgmann), resulted in a dramatic dislocation of ends from means. Highly emotive and susceptible personal value systems, such as a perceived enhancement of status, place an almost total emphasis on the end, allowing the means to be reduced to whatever it takes to facilitate its existence.

Problematic means to superlative ends

We’ll conclude with 5 key examples of problematic means hidden behind the thick facade of the superlative object.

1. The verb to design has become increasingly separated from the verb to make. As a consequence the practice of planning has become reduced to moving shapes around on a screen, whilst the arranging of (physical) elements happens in increasingly complex technical systems. Design is dislocated from making.

youtube

The designers of today’s superlative objects follow both Morris and Bel Geddes’s lead in that they remain obsessively connected to the manufacturing process. However, the complexity and expense of the machines that do the making have grown exponentially.

In a 2012 video (above) showing the manufacturing process of the iPhone 5, Jony Ive states the Apple belief that ‘going to such extreme lengths is the only way that we can deliver this level of quality’. Whilst Apple’s approach clearly leads to the elevated status of their products, the machinery at their disposal gives them an enormous advantage over those with more humble tools.

2. The material elements used in contemporary designed artefacts (e.g. rare earth elements) have become increasingly global and out of reach of the individual.

In this case we can trace the origins of the designer’s use of elements back to the colonial era. Arthur Chandler notes that at the time of the 1855 World’s Fair, ‘the French attitude is a mixture of pure greed and the dawning sense of the “civilizing mission” of France: Africa will supply the raw materials; and in return, France will supply the most precious of all commodities: French civilization’.

Turning again to the iPhone, it comprises 75 of 118 elements from the periodic table (the human body is made up of around 30). In a 2017 article for the Los Angeles Times Brian Merchant described the pulverising of an iPhone and then analysing the resulting dust using mass spectrometry, X-ray fluorescence and infrared analysis. He suggests that to obtain the 100 or so grams of minerals found in a single iPhone, miners around the world have to dig, dynamite, chip and process their way through about 75 pounds of rock on nearly every continent. Very little has changed!

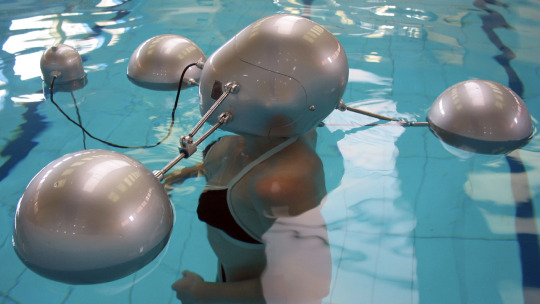

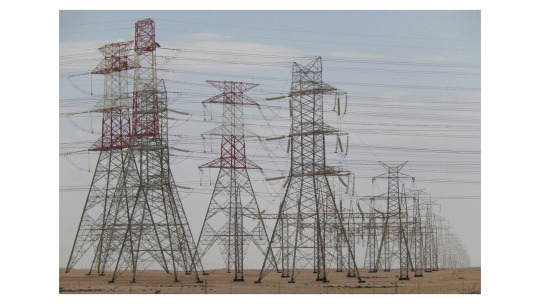

3. The functional purpose of contemporary designed artefacts has become increasingly dependent on global infrastructure systems, thus perpetuating established power structures.

In A History of the Future (2008), Donna Goodman describes how the invention of electricity was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the coming machine age. By the 1940s 90% of American homes were connected to the electricity grid. This in turn led to many new domestic products - all electrically standardised via the sockets they plugged into and all dependent on the infrastructure.

Contemporary products today are reliant on far more complex systems than the electricity grid; for example, the GPS system on mobile phones is owned by the US Government and operated by the United States Air Force. Anything from thermostats (e.g. Nest) to vehicles are increasingly becoming reliant on, and controlled by, connection to the internet. The design of almost all modern products is constrained by the reliance on infrastructure.

4. The aesthetic purpose of contemporary designed artefacts has become deeply entwined with the manipulation of human desires via increasingly sophisticated marketing practices.

This is not a new practice. In 1890 Richard Redgrave likened the French Goods at the 1855 Paris Exhibition to the ‘gilded cakes in the booths of our country fairs, no longer for use, but to attract customers’. In Objects of Desire (1986), Adrian Forty affirms that for a product to be successful it must incorporate the ideas that will make it marketable.

This results in manufacturing goods ‘embodying innumerable myths about the world, myths which in time come to seem as real as the products in which they are embedded’. How then to re-separate the object from its image? Or to see through the image to what it really stands for?

Even the more respectable elements of the media fall prey to design’s sleight of hand - this is from an article in the New York Times in 2016:

‘There has been zero innovation in this market for over 60 years,’ said Mr. Dyson, 68, a billionaire who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2006. ... Mr. Dyson, Britain’s best-known living inventor, is the Steve Jobs of domestic appliances. He has built a fortune from making otherwise standard products seem aesthetically desirable ... Dyson said there were 103 engineers involved in the creation of the Supersonic, which included the taming of over 1,010 miles of human hair tresses and 7,000 acoustic tests as teams tackled three core issues: noise, weight and speed. ... As a result, the Supersonic will retail at $399 when it arrives in the United States in September.

5. The plans for designing contemporary artefacts are typically iterative in nature. This facilitates and maintains the current approach to economic growth via generational products.

We raised the constraint of future nudge in one of our early posts - here’s a slightly updated explanation: According to the economist Robert Heilbroner, ‘All inventions and innovations ... appear essentially incremental, evolutionary. If nature makes no sudden leaps, neither, it would appear, does technology.’ And as a consequence neither do technological products.

This limits the designer to developing only what the current product could realistically evolve into. In reality it is a mechanism, employed by corporations - to maintain lucrative generational economic models, extend the life of production lines, pander to conservative tastes through risk-avoidance, facilitate rapid object obsolescence, and encourage various forms of brand loyalty.

There is nothing to suggest, however, that the decisions made many product generations ago were the ideal ones. Whilst natural organisms cannot be freed from their genealogical lineages, technological artefacts certainly can.

Next post: Towards appropriate means

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-petroleum futures

Several months ago Crap Futures gave a talk at the Center for Contemporary Theory (3CT) at the University of Chicago. The theme provided some good inspiration for new thinking on the state of design. Now, at the dawn of the new decade, we’ve finally got around to sharing some of these thoughts in blog form, many cups of coffee and plates of toast later.

For obvious reasons, there are many discussions at the moment asking: ‘What comes after petroleum?’ Before getting into this, it might be helpful to better understand the promise of petrol – what were the origins of petroleum utopias? Who was responsible for them? And what agendas were hidden behind the progressivist imaginaries?

So, starting with petroleum (and related materials): this naturally occurring liquid is essentially a battery, which stores a fragment of the solar energy that reached the earth during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods (typically via algae and woody plants). While the first recorded use of petroleum can be found 4,000 years ago when natural asphalt was used in the walls and towers of Babylon, it wasn’t until the early 20th Century that its potential, as a useful form of energy, began to exert its influence on so many and diverse aspects of human life.

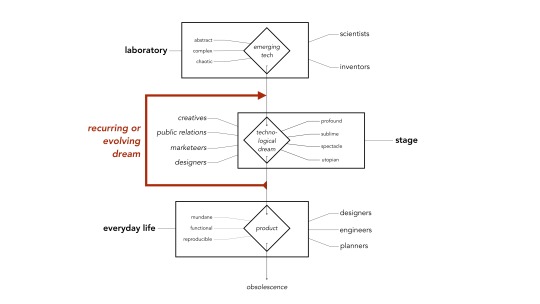

This diagram (which appeared in a previous post) describes the fairly typical journey a technology makes, starting from its genesis as an emerging technology in the laboratory. Next is the technological dream phase in which the potential of the emerging technology is translated into techno-utopian imaginaries – intended by both corporations and politicians to sell particular agendas to the public audience. Designers love this phase, as the constraints that apply to the design of normal products do not yet exist. The last phase is the transition of aspects of the dream into real products in everyday life – and this of course means the implementation of all the infrastructure necessary to allow them to function. Finally the product descends into obsolescence, as it is replaced by more advanced iterations. Or else the dream gets recycled or regurgitated; updated with the latest technology.

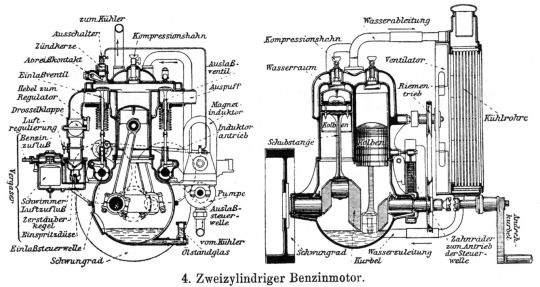

Applying this journey to petroleum – the new machines of the late 19th and early 20th Century, such as the internal combustion engine or the coal-powered steam generator – revealed for the first time the true potential of petroleum. In a split-second its energy, captured during the time when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, could be magically transformed into heat, noise and more importantly movement! Lots and lots of movement – think of the Italian Futurists in 1909, championing ‘a new beauty: the beauty of speed’ – ‘a roaring car … more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace’ – a new perspective on time and space that comes to symbolise modernity in all its thrilling, dynamic and destructive power.

The aeroplanes, automobiles and ships that were built around these engines also became the symbols of the new machine age, as extrapolations of the potential of the internal combustion engine fed the utopian imaginaries of the near future.

For a country emerging out of the despair of the Great Depression, Streamline Moderne (as it became known) represented the American dream of freedom and escape – both in the physical sense, through the action of the engine, and in the metaphorical sense, through the sleek teardrop styling that gave the impression that the object was moving – even when standing still. Designers, meanwhile, were for the first time beginning to play an instrumental role in linking technological progress to the notion of a better future – all in the service of American corporate capitalism …

… and in turn inspiring the design of the new wave of domestic products – toasters! radios! televisions! washing machines! – that would give consumers a sense of buying into, and thus belonging in, that utopian American dream.

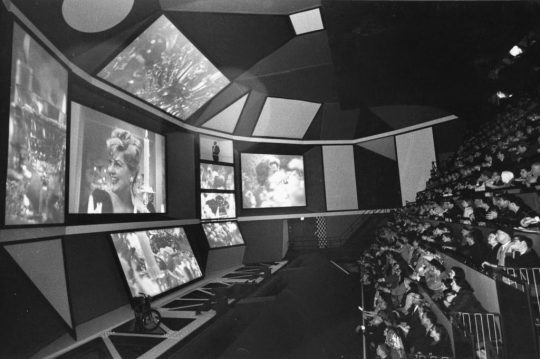

Nothing exemplifies this period of techno-optimism better than Futurama, General Motors’ exhibit at the 1939 New York World Fair. This described a further extrapolation of the potential of petroleum - outwards across time and space. Designed by Norman Bel Geddes, the 35,000-square foot interactive exhibition presented a version of the United States set 20 years in the future, with sprawling superhighways connecting the major cities and facilitating the growth of suburbia as commuters escaped from the claustrophobia of urban life.

E. L. Doctorow’s 1985 novel World’s Fair is revealing in its dramatisation of events, as it connects the key players who, behind the scenes, write the scripts for such techno-utopian futures. In this excerpt a family are leaving Futurama when the child asks his father for his opinion. The father replies:

Of course the roads were built and many cars were sold, but with the benefit of hindsight it is obvious that the Futurama was no utopia. For consumers, however, the dream kept evolving.

In the 1950s the jet engine allowed for super-sonic flight, expanding the horizons and moving the utopian visions upwards and into the ‘final frontier’ (note the colonising terminology) of space.

Another famous world’s fair took place 25 years later using the very same venue – Flushing Meadows in Queens, in 1964. It represents the final extrapolation of petroleum utopias – within a few years they were exhausted. As the novelist J. G. Ballard observed in a 1979 interview with Penthouse magazine:

‘The world of "Outer Space", which had hitherto been assumed to be limitless, was being revealed as essentially limited, a vast concourse of essentially similar stars and planets whose exploration was likely to be not only extremely difficult, but also perhaps intrinsically disappointing. … The number of astronauts who have gone into orbit after the expenditure of this great ocean of rocket fuel is small to the point of being ludicrous. And that sums it all up. You can't have a real space age from which 99.999 per cent of the human race is excluded.’

Elsewhere at the same expo, however, a new genesis was being revealed - introducing a refreshingly new direction for technological futures.

The IBM Pavilion, with exhibition design and a film presentation by Charles and Ray Eames and architecture by Eero Saarinen, introduced visitors to the computer and its place in mainstream contemporary life. Again quoting Ballard:

‘The ability to pass information around from one point in the globe to another in vast quantities and at stupendous speeds, the ability to process information by fantastically powerful computers, the intrusion of electronic data processing in whatever form into all our lives is far, far more significant than all the rocket launches, all the planetary probes, every footprint or tyre mark on the lunar surface.’

Jumping forward to the present and the corporate dreams of today – very well encapsulated by Google’s self-driving car – it becomes apparent that little has changed in terms of strategy: government and corporations in collusion, shaping the technological future on our behalf, with largely the same agendas. At the forefront are a few leading designers whose role hasn’t for the most part evolved much since the days of Norman Bel Geddes.

Here are a few key observations on why visions of the future have stagnated or are simply not appropriate for the world of the 21st Century:

1. Those responsible for the creation of future visions are guilty of being overly optimistic – never acknowledging the possible negative implications.

2. Those responsible for the creation of these visions are guilty of being overly simplistic – perfect worlds, perfect people, interacting perfectly, thus negating the complex and messy reality of human lives.

3. The reduction of future visions into objects of desire has resulted in the dislocation of means and ends – the systems that facilitate the function of products have become largely invisible and intangible.

4. The reduction of visions into objects of desire leads to an increased instrumentalisation of operation and banal iterative development.

5. The emergent technologies that are extrapolated into today’s utopian visions (IoT, AI, nanotech, etc.) tend to act in the background, at intangible scales, or in complex languages – meaning that the resultant futures are difficult to convey (and sell).

6. Corporate imagination that informs future visions is frequently underwhelming – merely updating, through the application of emergent technologies, the pursuit of ancient human obsessions (artificial life, immortality, flight, automation).

7. Finally, many of the metrics through which we evaluate future imaginaries remain the same as those from the machine age – faster, more efficient, more automated – and as such are wholly inadequate for addressing the complex problems we face today.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

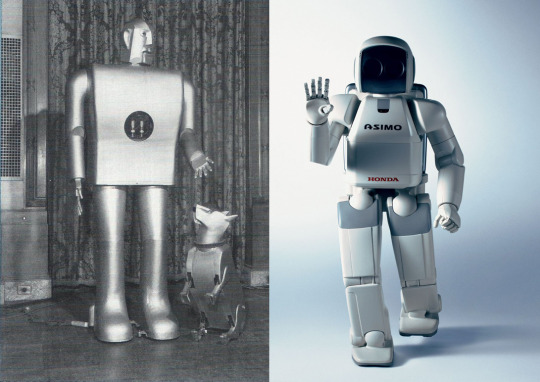

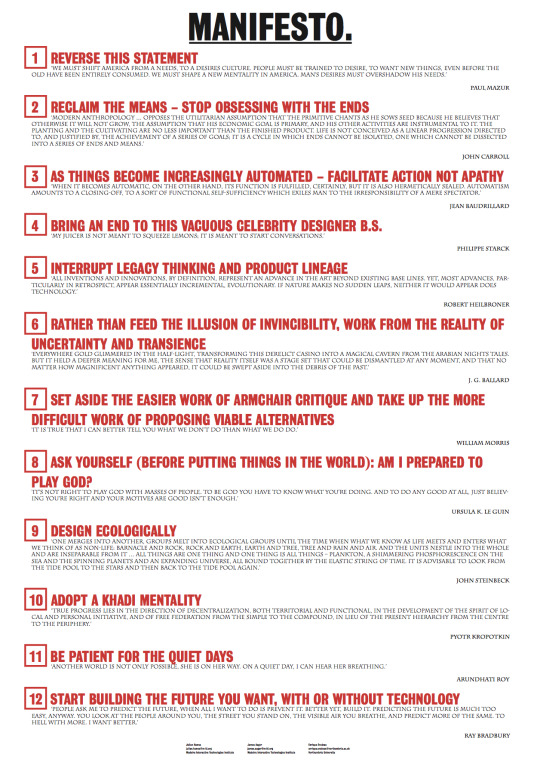

Reconstrained Design (the book)

We have a new book, a catalogue of sorts, covering certain aspects of our work as the Reconstrained Design Group* over the past couple of years. It’s a handsome object full of nice words and images - some of which you may have seen first on this blog. There is also new material: for example, it features essays on Reconstrained Design by Lucy Suchman and Clive Dilnot. Please send us a message if you’re interested in receiving a copy.

Here is a short piece from the book, ‘DIY Reconstrained’, written by ourselves and Enrique Encinas:

The three words that form the DIY acronym send a clear and empowering message: anyone can do it. You can do it. But do what? What needs to be done? For some, DIY resides in a shed at the back of the garden—the Reader’s Digest manual from the 1970s that tells you how to fix everything from a drainpipe to a typewriter. For others DIY suggests punk rock, a form of expression that requires only minimum skill to achieve satisfying results, and that builds around it an active community, rejecting the passivity of corporate consumerism.

DIY is rational resistance to an irrational consumer culture. Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers declared in 1927: ‘We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture.’ Public relations, advertising agencies, and designers answered Mazur’s call with methods appealing not to the rationality of citizens but to the irrational and subconscious drives of consumers. The marketplace boomed as selling bypassed the intellect to interact directly with the emotions. This near complete alteration of perspective puts DIY in a fragile position—impoverished by its more complex appeal, its objects struggle to compete with the hi-gloss culture of brands and fashion. For many consumers, the latest iteration of consumer electronic products exhibit a near sacred aura.

In Mythologies (1957) Roland Barthes describes this elevation of object status through the example of the Citroën DS, the ‘Goddess’—‘a superlative object’. He comments on the seamless perfection of the vehicle, likening it to the ‘unbroken metal’ of science-fiction spaceships and even to the smooth and seamless robes worn by Christ. Seams, he argues, reveal the hand of the (human) maker—methods of assembly and therefore dis-assembly (or fixing). In a sinister shift, this godlike approach to artefacts has become the celebrated norm of product design—think of Apple—where ‘perfection’ means not letting any grubby hands inside the pristine carapace of the technological device, not meddling with divine creation. How can DIY compete with such perfection?

The deskilling of a generation of young people presents another problem for DIY, as schools focus too exclusively on new ways of making such as 3D printing and laser cutting. This has severely limited the scope of what can be made and by whom.

It was in the early 20th century that DIY, the ungenteel inheritor of the Arts and Crafts movement, got its name. Then and now, in the Maker Movement, DIY is viewed as a creative and/or recreational and/or money-saving activity. It is helpful, useful, and fun. It is as straightforward a practice as the end it wants to accomplish. Through a set of accessible premises, ‘shed’-style DIY launches the rational individual into a journey of self discovery and learning—a journey that normally ends when function is met and hence need is no more. As a good citizen, one finds in DIY the sensible alternative to a trip to the store. As a consumer embedded in a culture of desire, however, the workshop presents a real challenge—who has the time, access, or requisite knowledge? As with the Arts and Crafts movement, the Maker Movement risks simply being a mouthpiece for the middle classes, an outlet for those with the disposable time and income to temporarily reject the mainstream attitude towards objects and our interactions with them. So what can be done?

Royal detested this orthodoxy of the intelligent. Visiting his neighbours’ apartments, he would find himself physically repelled by the contours of an award-winning coffee pot, by the well-modulated color schemes, by the good taste and intelligence that, Midas-like, had transformed everything in these apartments into an ideal marriage of function and design. In a sense, these people were the vanguard of a well-to-do and well-educated proletariat of the future, boxed up in these expensive apartments with their elegant furniture, and intelligent sensibilities, and no possibility of escape.

- J.G. Ballard, High-Rise

Consumers have been programmed for sleek, seamless products far too long to accept the standard (non-designed) DIY aesthetic overnight. The desire for award-winning coffee pots (and phones, juicers, hair dryers, etc.) is strong, and for the time being Ballard is most likely right—there is no possibility of escape. This leaves two options: one easy, one very difficult.

The hard route: Adapt consumer desires to a maker aesthetic. Reprogramme people to be less obsessed with brands, or to see value in what is rough, cheap, or practical.

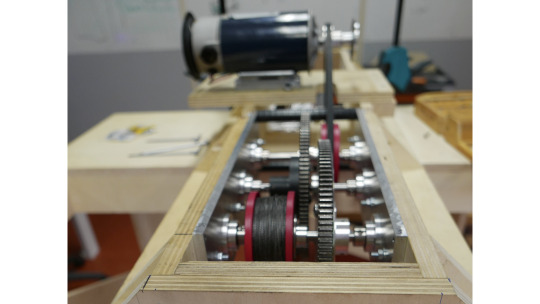

The various gravity batteries described in the Newton Machine project exemplify the approach with their focus on easy making over high-level production, found components over highly-refined, open-source over heavily patented and local materials over globally sourced. This is the first challenge we set in our manifesto—to reverse Mazur’s statement and return to a needs-based culture. But this is a slow-burning, long-term strategy.

The easier route: Adapt the DIY aesthetic to what people want. Introduce a better sense of design that allows maker products to compete with mainstream exemplars of good design such as Apple and Dyson. What would a DIY artefact like if it had the touch of Charles and Ray Eames? Or Dieter Rams? Or Enzo Mari? There aren’t many designed maker objects to be found. The OpenStructures WaterBoiler is one example of how such things could look. Originally designed by Jesse Howard and Thomas Lommée, it was adapted by Unfold, who replaced the PET bottles with a cut-through bottle (see Tord Boontje’s Transglass project for the potential of cut recycled glass) and used a combination of 3D-printed ceramic, off-the-shelf plumbing material and simple folded steel. If more objects like these were produced by the Maker Movement, there might be a chance of shifting consumer habits.

To complement our sometimes utilitarian approach, we are developing more designerly examples of Reconstrained Design addressing the complex notions of desire that drive conspicuous consumption. The Gravity Lamp and Gravity Turntable, for example, aim to provide a more direct challenge to contemporary design, by removing constraints imposed by its relationship to the market. The aim is not only to address stylistic issues but also the problem of making—that the route to ownership should not be constrained by a lack of skills or access to tools. The solution is to build a network of experts, professionals, and craftspeople, essentially decentralising DIY by engaging with the local community, its expertise and its resources. A DIY manual for a product could, for example, be a wiki that shows the constructive steps but also points the way to local cabinet makers or metal shops that will help to build sophisticated elements of a project. This approach would also support the survival of craft knowledge in local communities.

* The Reconstrained Design Group is James Auger, Julian Hanna, Laura Watts, Enrique Encinas, Mohammed Ali, and Parakram Pyakurel

Images:

Citroën DS 19; Enzo Mari by Adriano Alecchi (Mondadori Publishers) - both via Wikimedia Commons.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scratch an itch: A taxonomy of automation

We promised this post getting on for two years ago. In the meantime James has decamped to Paris and Julian has just completed a book on manifestos. Last week happened to find us both in Madeira, so we had a crack at devising a taxonomy of automation over our usual coffee and toast. The itch motif likely springs from the fact that it’s mosquito season.

As long ago as 1958, the philosopher Gilbert Simondon warned of the implications of automation, using developments in the motorcar to illustrate his argument. Simondon criticised the starter motor for overcomplicating the mechanical purity of the internal combustion engine. He preferred the simplicity of the manual turning handle: less to go wrong, easier to fix. Of course Simondon’s warnings, and many others in between (see challenge #3 of our manifesto), have been mostly ignored as we continue down the road of increasingly over-engineered standards of luxury, captured here in an observation from the environmentalist Bill McKibben:

At a certain point, says the philosopher Albert Borgmann, “Technology … mimics the great breakthroughs of the past, assuring us that it’s an imposition to have to open the garage door, walk behind a lawn mower, or wait twenty minutes for a frozen dinner to be ready.” Borgmann wrote that twenty years ago. Now the salesmen insist that it’s an imposition to have to press the button that opens the garage door when the smart ID chip embedded in your bicep can do it for you.

Simondon’s critique of the starter motor may now appear somewhat dated, as it is perhaps a bit of an imposition to crank a car into life each time you want to drive somewhere. However, such warnings, made when the automation of everyday life was in its infancy, become extremely poignant when you consider the ‘advances’ made in recent years - in particular the increasing complexity and non-fixability of contemporary technical systems.

Our taxonomy of automation, sketched hastily on the back of a coffee-stained napkin, charts the shift from Fordist-style production lines to more complex near-future scenarios in everyday life. We’ll start with our (adapted) definition of a robot to help clarify what we mean by automation:

For a thing to be considered ‘automated’ it should be able to sense and interpret in some fashion its environment, compute decisions based on that sensory information, and then act on those decisions in a physical way.

The basic assumption is that the combined automated operation satisfies some human need or desire: the sensing aspect realises the existence of the desire, computation figures out exactly what this is and how to address it, and the act is the physical intervention that satisfies the desire.

We’ll attempt to explore the taxonomy by describing various technologically progressive ways of satisfying the desire to scratch an itch ... please bear with us (starting with that terrible pun).

The Simondon scratch. You have an itch and the instantaneous desire to get rid of it - so you do it the old-fashioned way, using what is in your local environment (say, a tree trunk) without enlisting the aid of any automated system. This is clearly not part of the ‘official’ taxonomy, since there is no automation in the process. Like the cranking of the engine, the desire is fulfilled by direct human action. The downside is that it takes more effort and a certain amount of skill. The upside is that the human has almost full control over the system.

The Fordist scratch. Or to use the industry term, semi-automation. You feel the itch and guide your scratching machine to the correct place, where it satisfies the desire in a collaborative manner. In this case the sensing aspect is non-existent. Desire is experienced by the human, who then sets the automated process into motion with the physical button. This taxonomic category largely has its origins in the push-button future kitchens of the 1950s, where everything the family desired was available though the simple push of a button.

Modern, and slightly disappointing, versions of this stage include the Amazon Dash - a person, realising the lack of a particular (desired) product, presses the appropriate Dash button. This engages an already-in-place physical infrastructure that follows a predictable path to satisfy the original desire.

For the purposes of this discussion we’re focusing on domestic notions of automation. There has been much debate over the pros and cons of Fordism in manufacturing, for example: reduction of hard or repetitive labour, cheaper products vs. fewer jobs, deskilling of the workforce, and the standardisation of products in both a positive and negative sense. The advantages and disadvantages in the context of everyday life are in some ways related: domestic automation does reduce human labour (going to the shop), but the reduction of choice that arises as a consequence of production lines (any colour so long as it’s black) is also felt by those using a service such as Amazon Dash. Consumers are locked into: (1) product lines that Amazon have negotiated a contract with, and (2) products for which they have bought a Dash button.

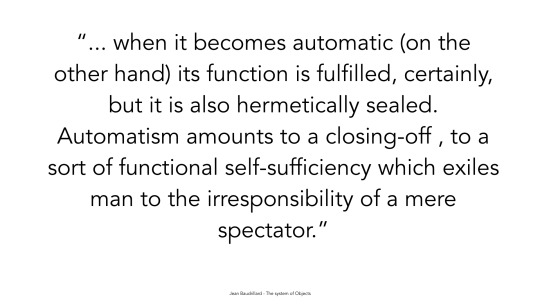

Simondon, again in the critique of technical systems, described automatism as ‘a rather low degree of technical perfection’ due to the number of possibilities of operation and usage that need to be sacrificed. The more open nature of semi-automation can provide a counter to this argument, but not in the form described by Dash - the key element that needs to be considered (from the experiential perspective) is in the balance and malleability of the collaboration.

Here is one of our favourite examples, in which the system replaces the human act of throwing a ball. This very basic automated system benefits equally all elements: the robot would be pointless without the dog; the dogness of the dog is enhanced by the function of the robot; and the dog’s owner, the one being replaced by the machine, enjoys both relief from the effort of throwing the ball and pleasure from the continuing spectacle. (For some reason this video never gets boring.)

youtube

The smart scratch. In this scenario, always-on sensors are scanning for an itch. For example a thermal imaging camera could detect a hot-spot from a mosquito bite (extremely common in Madeira) and guide the scratching machine to the appropriate place.

This stage represents an important shift in the process, as the recognition and interpretation of human desire becomes integrated into the automated system through the action of sensors. These sensors operate in real time and make fairly basic assumptions, like a basic if/then statement - for example, [if] a presence sensor in a smart fridge detects a low level of eggs [then] it computes the decision to order another box. The rest of the process happens as in the previous stage. The effort, on the part of those implementing the automation, is to minimise the timeframe between the occurrence of the desire and its satisfaction.

The category was explored in detail in one of our very first posts, smart futures = crap futures. One contemporary example is the Amazon Dash Replenishment Service (DRS), which orders products automatically, without the push of a button. The [then] command reduces possibility in exactly the way Simondon discussed, as the system is essentially closed. It enforces repetition, standardisation and efficiency - which, in an era that increasingly appreciates and even fetishises ‘slow food’, is exactly not what a person with fluency and flair in the kitchen desires.

This category suffers the same problems as the utopian promises made in the last century, and why so many future visions fail. They are driven by either technological dreams or engineered notions of progress, such as efficiency. They ignore the complex and messy reality of human activity and desire. Smart systems also raise the key question: What desires can realistically be sensed, and how open is the reading of that sensing for misinterpretation (a point we explored in our careless whispers post).

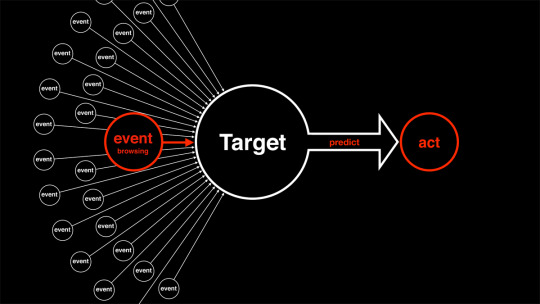

The scratch before the itch. The system predicts the itch. Perhaps you’ve experienced it before, at predictable intervals in predictable places, or the prediction is based on data relating to the behaviour of individuals with similar profiles, as well as the fact that it happens to be mosquito season where you live.

Or, to continue the parallel example of the fridge, the system might anticipate that you’ll need avocados on Saturday - because you normally make a lot of avocado toast, or whatever. Or it might check your calendar and see that you’re having friends over and you’ll need a box of cheap wine and Doritos for entertaining, or conversely that you’re going to be out of town and therefore won’t need anything. It might order the ingredients of your favourite dinner party menu and hangover breakfast, or ‘propose’ fun activities like baking a cake. (The elaborate possibilities of a truly smart fridge paired with a busy social life are intricate enough to require a separate post - in fact we’ve been working on such an idea called Elvis’s Fridge.) This stage brings to mind Amazon Go, the cashierless stores first introduced in 2016. Amazon removes human interaction - the type of recommendations that you might get from a local grocer or butcher, the foundation of local communities - and delegates instead to the algorithm.

The tickle that makes the itch. The system over-automates, presuming to know you better than you know yourself. Or the system becomes manipulative - perhaps even creating the itch in the first place. There is an obvious loss of control at this stage, with complex decisions being made on your behalf. Desires are being triggered through direct appeals to your reptile brain. Services like Amazon Go are venturing into this territory, raising issues of privacy and the extent to which consumers are being forcibly assimilated (or very strongly nudged) into systems using biometric data and other new technologies. The tipping point is retaining human agency versus being governed by the system. Some people recoil at this loss of control, while others embrace it. Why not let a machine make all the decisions for you?

It seems to us that the optimum point of automation is where a machine does the drudgery and human agency and control are still given priority. Simondon compares this preferable state to an orchestra, where machines are the musicians and the human being is the conductor. They work together in harmony: the machines play a crucial role, but the human ultimately serves in the role of interpreter and decision maker - ‘inventor and coordinator’. As the stages of automation progress, this starts to shift: the automated system increasingly influences and intrudes on the terrain of desire.

Freud wrote about the pleasure principle (id) versus the reality principle (ego), the latter involving the delayed gratification that comes with adulthood. Higher level automation combined with late capitalism invites us to override our adult selves, exchanging self-control for the childish expectation of instant gratification in all aspects of daily life. (Think of Amazon Prime Now’s guaranteed one-hour delivery, and the extreme time pressure that means employees can’t even stop to perform essential bodily functions.) The fear of complacency and passivity has long been associated with technology, from Brave New World to WALL-E. Of course it depends where you live: in Madeira, for example, an Amazon delivery still takes weeks to arrive.

Resistance to algorithmic control is popping up everywhere, including some unexpected places. The Rage Against the Algorithm colloquium, held this month in Prague on the anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, is one example. The event, hosted at Charles University, featured speakers such as Nick Srnicek (Accelerationism), Helen Hester (Xenofeminism), and Louis Armand (Alienism), all in some sense responding to the challenges, threats, and opportunities presented by automation and other ‘advances’. Over in America, meanwhile, there is the long brewing backlash in Silicon Valley against algorithmic control, with a rise in no-tech homes and schools. Things have flipped in the past decade, so that poorer schools increasingly rely on devices like iPads while more economically advantaged schools are going tech-free, back to basics, Waldorf curriculum, and so on. In his essay ‘Why I am Not Going to Buy a Computer (1987), Wendell Berry anticipates this shift with the simple observation: ‘If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer idea is not to use one.’

Increased automation touches on a number of important themes, some of which we’ve discussed before: narrowing pathways, loss of agency, deskilling, automation of habits and desires, loss of identity and self, alienation from natural processes. In Mythologies (1957), Barthes laments the way that mechanical toys (unlike wooden ones) encourage a passive role:

faced with this world of faithful and complicated objects, the child can only identify himself as owner, as user, never as creator; he does not invent the world, he uses it: there are, prepared for him, actions without adventure, without wonder, without joy.

People want more pleasure with less work - that is the promise of automation. But how much pleasure can we take? And how much do we enjoy endless pleasure, which is often not even pleasure, but mere convenience? What is pleasure without resistance, or a bit of pain? To return to the example of the itch, if we could anticipate and remove the itch forever - never have to scratch again - would we? Or would we miss that strange animal pleasure? Scratching an itch releases the hormone serotonin, which we could obtain artificially, without causing any negative effects But would it be as sweet?

In his great novel of tyrannical automation and technological control, Player Piano (1952), Kurt Vonnegut paints a vision of America as ‘one stupendous Rube Goldberg machine’. Assuming at this point we cannot stop it completely - or wouldn’t want to - how can we escape the worst effects of this vast and hidden, pervasive and all knowing machine?

Images:

Coffee and toast (photo: Julian Hanna); Baloo in Disney’s The Jungle Book (1967); Amazon Dash buttons (2015-); a wood shop in Santo da Serra, Madeira, Portugal (photo: Julian Hanna); a tin mechanical toy (CC0).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Careless whispers

In a previous post we mentioned the story of the infamous conflict between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 12th century England. It’s a familiar story of two powerful and egotistical men clashing over issues of status and pride. After a series of altercations over clerical privilege, Henry finally loses his temper; what he actually said to the assembled courtiers has been lost to history, but the most likely version comes from the biographer-monk Edward Grim, who recorded it as follows:

What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?

Whatever Henry said, four of his knights (Richard le Breton, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, and William de Tracy) interpreted the utterance as a royal command. They rode to the Normandy coast, took ship for England, and confronted the Archbishop. What happened next was described by the aptly named Grim, who was on the scene and actually wounded in the attack:

The wicked knight, fearing lest Becket should be rescued by the people and escape alive, leapt upon him suddenly and wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God, cutting off the top of the crown which the sacred unction of the chrism had dedicated to God.

More terrible blows followed, and eventually the Archbishop succumbed. Was the king’s statement interpreted correctly? We’ll never know. But we can perhaps read parallels to our own time in the complex motivations and agendas that informed the knights’ collective decision to commit murder.

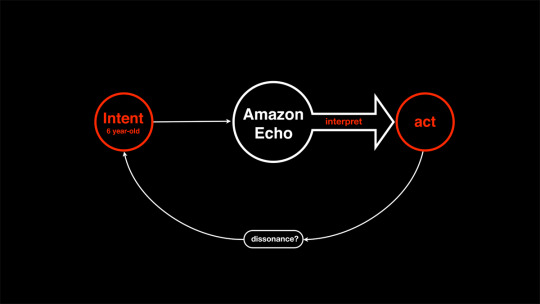

Another story, more recent. This one takes place in Dallas, Texas, where a six-year-old girl asked her family’s Amazon Echo: ‘Alexa, can you play dollhouse with me and get me a dollhouse?’ Alexa promptly complied, ordering a $300 KidKraft Sparkle Mansion doll’s house from one of Amazon’s suppliers. She also ordered (for reasons known only to the internal logic of the system) nearly two kilograms of sugar cookies. The story doesn’t stop there: the following day, when a San Diego news programme reported the story, a number of Echos were roused by the wake word ‘Alexa’ coming from proximate television sets, and they in turn followed the command to also purchase dolls’ houses.

What inspired Alexa to order the biscuits? A flawed system or a very smart one?

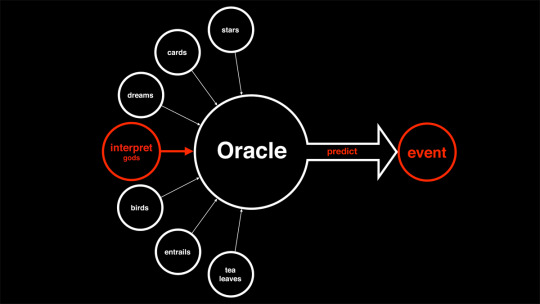

In 560 BC, King Croesus of Lydia set a challenge to the world’s oracles to determine who provided the most accurate prophecies. His emissaries were sent to seven sites to ask the resident oracle what the king was doing at that precise moment. The winner was the Oracle of Delphi, who correctly reported that the king was making a lamb-and-tortoise stew.

Oracles were seen as conduits to the gods, speaking and giving advice on their behalf. Divination came in many other forms: augurers would follow the flight paths of birds (legend has it that the location of Rome was decided through this approach). Haruspices would read the entrails of sacrificed animals. Today, however, reading the future is much less exotic or gruesome, being mostly about data and statistics.

The next story starts back to front. A man walks into a Target outside Minneapolis and demands to see the manager. He’s got a handful of targeted coupons that had been sent to his teenage daughter, and he’s angry. ‘My daughter got this in the mail!’ he said. ‘She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?’ In fact the daughter actually is pregnant. Target knows it before the girl’s father, thanks to a hunch based on its analysis of online searches and product purchases - in this case a particular lotion often used by pregnant women in the second trimester.

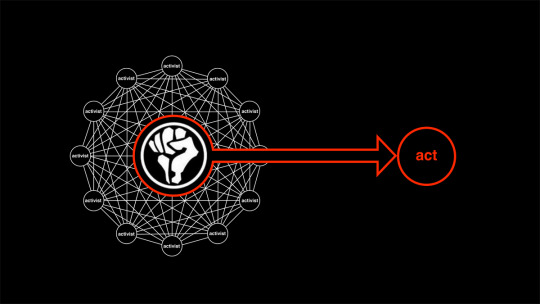

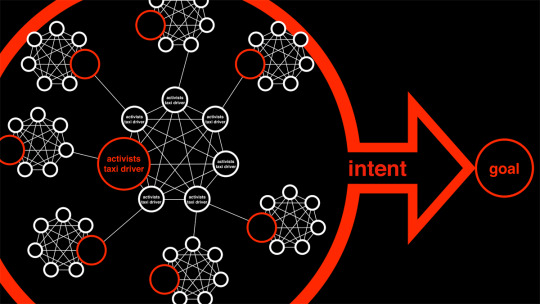

One more story. In happier times for Facebook, the social media giant played a significant - if unevenly distributed and still debated - role in the Arab Spring by facilitating communication between protesters. The April 6 Youth Movement in Egypt, for example, used Facebook to launch a successful call for protests in the aftermath of the Tunisian Revolution that preceded the spread of uprisings across North Africa and the Middle East in 2011-12. Events of the Arab Spring demonstrated that social networks provide a perfect mechanism through which to disseminate information broadly and quickly, as long as you have access to the internet.

So far this is a familiar and well-trodden tale; the more interesting story, however, happened when Arab states began to shut down internet access. Activists in Cairo found the solution in a different kind of social network - not screen-based, but via the city's taxi drivers. The activists realised that if they could direct conversations towards the planned anti-Mubarak gathering on 25 January 2011 in Tahrir Square, taxi drivers might spread the word and the protest would be a success. Initially, the activists tried to talk directly to drivers.

But they soon discovered that due to the highly politicised nature of their subject, conversations would quickly turn into arguments rather than dissemination, and their objective would fail. The solution was found in exploiting the human tendency to gossip. Instead of engaging in direct conversation, the activists allowed the taxi drivers to overhear a mobile phone conversation where they would disclose the details of the protests. The taxi drivers eavesdropped, and believing they had overheard a gossip-worthy secret, they began to spread the message.

‘Technology is making gestures precise and brutal, and thereby human beings.’ - Adorno

In one of our very first posts, The Pleasures of Prediction, we described the daily experience at our local cafe - where the gestures of interaction were not always precise, sometimes brutal (depending on the mood of either ourselves or the people behind the counter), but mostly genial and surprisingly seamless. More recently, our colleague was telling us how his landlady keeps track of the number of bottles of alcohol he consumes each week by counting his recycling - a sort of small island version of a fitness tracker like the Fitbit. ‘She’s not judgemental’, he said. ‘Well … not really.’ Of course surveillance and tracking - mediating, amplifying, interpreting - have always been present in society; in the past they were just more social, or at least more analogue.

These examples raise some big questions, such as: Would you rather be monitored by a human being or a machine? If machine, why? Why don’t we trust humans? For that matter, why don’t we trust ourselves? How have we been shown to be untrustworthy and unable to control our own self-destructive or anti-social impulses? For the past two years we have been collecting stories that relate to the interpretation of information - tracing the shift from human beings to technological mediation as translator and interpreter; who is making important decisions, on whose behalf, and why.

There is certainly precision and brutality in Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data for micro-targeting and psychological profiling. Likewise Amazon Echo, a data-based Trojan horse mediating our personal lives in increasingly precise but also brutal ways. There is a tendency to understand and evaluate technology according to old-fashioned notions of progress: faster, easier, more efficient and so on. But digitisation, the data that it creates, and the vast networks of dissemination also facilitate the augmenting of darker aspects of human behaviour, targeting our deepest vulnerabilities. How we examine the implications, embrace the ethics, and understand the complexity of these systems are some of the fundamental challenges we face.

Real Prediction Machines

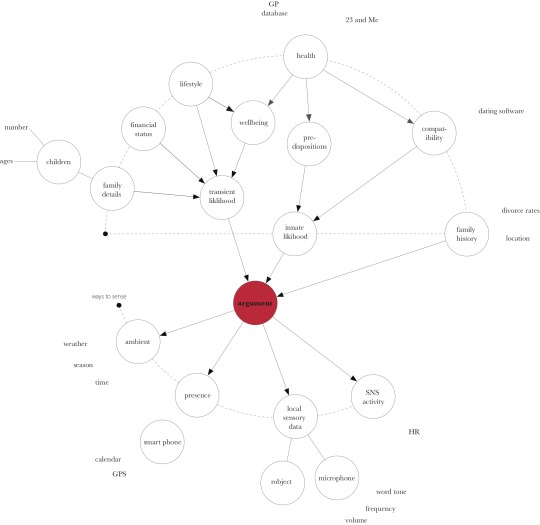

Shortly before the Echo appeared on the market in 2014, Real Prediction Machines addressed many of the issues Amazon’s new device (and others like it) would raise. The speculative project was developed by James Auger in collaboration with designer Jimmy Loizeau, artist Alan Murray, and Edinburgh University data scientist Ram Ramamoorthy, who at the time was developing predictive modelling systems combined with machine learning to predict when professional athletes might sustain an injury through overtraining.

James, Jimmy and Alan began by asking Ram what kind of other things might be predictable through such techniques, such as ‘Will my child become a professional football player’, ‘Will Labour win the next general election’, and ‘Will I suffer a heart attack?’ The words inside the circles of the Bayesian network diagram represent potential variables. In relation to a heart attack they could correspond to something like diet or exercise, the data coming from a supermarket loyalty card, or the accelerometer in your smartphone. Or more finite information such as family history, for example data coming from a genetic testing service like 23andMe.

These variables combine to create a live and ongoing feed into the predictive algorithm. The heart attack example seemed a little too banal due to its obvious connection to wellbeing and the huge growth of data and tracking methods, so the group suggested another question to Ram: Will I have a domestic argument?

The Bayesian network shown above looks similar to the earlier one, but in this instance a microphone was added for live sound input (anticipating the omnipresent Echo). Using machine learning, the system would become better at predicting arguments through the statistical analysis of keywords, tone, and frequency - identifying particular subjects that a couple might commonly fight about.

The output was translated into an object - not an app but something more symbolic, sympathetic. They settled on an ambient device sitting in the background, providing information when you might need it.

The device essentially has three states:

Clockwise means that the argument is moving into the future;

Anti-clockwise means that the argument is approaching, and the slower the rotation the more imminent it is;

When the rotating stops, the argument starts.

Projects like Real Prediction Machines work when it is not completely clear whether the idea is a ‘good’ one or not. Is it too invasive? Is it genuinely helpful? This is how we should think about all potential technologies, but we rarely do.

What happens next? How far away are we from Alexa ordering not biscuits, but a councillor? How much control will we have in the future, and how much do we want to have?

Images:

All diagrams by James Auger; photo of Real Prediction Machines by Sophie Mutevelian.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time reconstrained, part 2

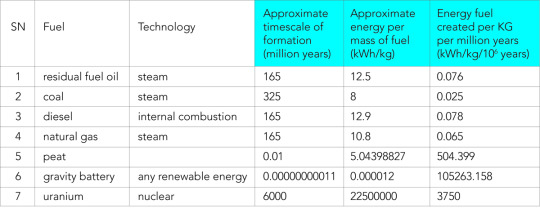

In the previous post we got onto the topic of time and energy. We pointed out that in this relatively blink-of-an-eye moment we’re living in—say the last hundred years—some of us enjoy the kind of energy abundance and comfort that no one before us had ever enjoyed and that, at this rate of simultaneous rapid consumption and spiralling environmental degradation, no one after us will either. We also described how, when time is factored in, fossil fuels are actually inefficient and low yield in terms of a time-energy ratio. Now let’s go a bit deeper into that thought: what if we took time seriously in our calculations of energy value and efficiency?

Time is a crucial factor that is often left out of discussions around energy. Traditional fossil fuels, as everyone knows, take millions of years to form and only brief moments to consume. So while they have very high energy densities (i.e. calorific values), drawing a direct comparison between fossil fuels and renewable energy sources can be misleading. Renewable energy sources have much lower energy densities—but they do not deplete in real time, and their formation timescale can be taken as virtually instantaneous.

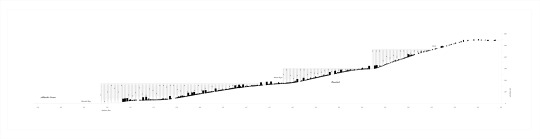

The table and graphs below compare renewable energy sources and traditional fossil fuels in terms of energy per mass of fuel as well as energy fuel created per kilogram per million years. Figure 2 for example shows that if only approximate energy per mass is considered, the energy storage value of a gravity battery using a renewable energy source is negligible compared with the storage value of fossil fuel. However, if the time taken to form energy sources is taken into account, the situation is suddenly reversed: fossil fuel sources become negligible compared to a renewable energy source like the gravity battery (Figure 3). (Thanks to our postdoctoral researcher, Parakram Pyakurel, for crunching the numbers used in these diagrams.)

Fig.1: Comparison between timescale of formation and energy stored

Fig.2: Approximate energy per mass of fuel (kWh/kg) vs. fuel

Fig.3: Energy fuel created per kg per million years (kWh/kg/million years) vs. fuel

Images: James Auger

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time reconstrained, part 1

We have assumed increasingly over the last five hundred years that nature is merely a supply of ‘raw materials’, and that we may safely possess those materials merely by taking them. This taking, as our technological means have increased, has involved always less reverence or respect, less gratitude, less local knowledge, and less skill. Our methodologies of land use have strayed from our old sympathetic attempts to imitate natural processes, and have come more and more to resemble the methodology of mining.

- Wendell Berry, ‘The Total Economy’ (2000)

The condition in which some of us now live—and have lived for decades—is undeniably a luxurious one, energy-wise, comfort-wise. No one in human history has had what some of us now have; but equally there is a growing sense that if things don’t change neither will anyone have it again—we are rapidly depriving future generations of energy resources and a clean, stable environment, both of which have too long been taken for granted.

A piece of coal provides roughly eight kilowatt hours of energy per kilogram, which in one sense is extremely efficient. But the coal takes hundreds of millions of years to form. This almost unimaginable quantity of time is consumed with the flick of a switch, or at the press of a button—all dissipated, all devoured in an instant, to light a room or power a computer. When time is factored in, therefore, fossil fuels actually provide surprisingly low efficiency, low yield in terms of a time-energy ratio. A gravity battery, while seemingly of negligible energy storage value compared to fossil fuels, becomes much more powerful when time is factored into the equation.

The ideas underpinning our current exhibition (as the Reconstrained Design Group, until 15 April) at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) represent a radically different philosophy of energy storage and consumption. They indicate a shift away from quick, thoughtless consumption of ancient resources, towards visible, tangible, real-time consumption. Of course, at this stage the Newton Machine is more of an intervention than a practical solution—it is not designed to be an instant fix for the world's energy problems, which are complex and multifaceted.

But before our prototypes and the thinking behind them are dismissed on grounds of impracticality, it is worth noting that our everyday relationship with energy is also a dream, an illusion of through-the-wall magic. It is unsustainable, based on a fantasy of unlimited supply, when in fact it has long been operating on a system of sleight of hand and perpetual deferral. When oil supplies are dwindling, the short-term answer is new technologies of extraction or batteries made from lithium and other non-renewable materials. What the Newton Machine offers is a new way of thinking about energy—a gesture, however rough, towards the seismic paradigm shift that is urgently needed to bring about a more responsible future.

Time is at the centre of this proposed shift in thinking. So is our relationship with nature, which must become balanced rather than extractive and exploitative. Even the generic and ubiquitous electrical sockets in our homes are anything but harmless. The apparent banality of the plug and socket has masked a century of unprecedented environmental destruction. By hiding energy, we have made it seem free of both limitations and consequences. A temporal convenience such as a hot bath or a flash of light releases potential (stored) energy irreversibly. Buttons, switches and plugs conceal enormous infrastructures and exploitation of existing resources on a truly sublime scale.

Design influences desire. If in the past design has been used to encourage consumption, to make consumer goods desirable, then in the future we must enlist design in the fight to bring our desires more closely in line with our needs. A shift is required to preserve what has taken millions or billions of years to form in the past, and to avoid a legacy of waste stretching forward into the future. We have to adjust the scope of our consumption. Reconstraining time means shifting away from the behaviours that brought us into the nightmare of the Anthropocene, and living sustainably within our own modest scale as an animal species on Earth.

Images:

James Auger (top): Gathering black sand for casting at Praia Formosa, Madeira; Miguel Taverna: Images from CCCB exhibition

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Et in Orcadia ego

In a recent post (‘scrap futures’) we mentioned a project we’re doing with Laura Watts from ITU Copenhagen and partners in Scotland that involves building a gravity battery on the small island of Eday in Orkney.

We’ve just returned from that island-to-island journey. It was quite a trip, a proper eye opener. We arrived on Sunday evening with nothing - no tools or materials of any kind - and by Thursday we were running a public demo of a gravity-powered Casio keyboard playing Ode to Joy. Here is a brief (and highly subjective) travelogue and technical account of the process, which was not unlike a 72-hour Scrapheap Challenge, but involving the whole community.

The northward trek

Three of us left Madeira early on the Friday, bidding farewell to sunshine and flower blossoms. The fourth in our party, Mohammed, coming from rural Sweden, met us that night in Inverness. By Saturday morning we had reached Kirkwall, on the Orkney Mainland. Laura arrived on the next flight, and over a lunch of fish and chips we shared our thoughts about the gravity battery, including what sort of scrap we might use to make it - an old motorcycle, a car or tractor, even a crashed Vespa someone had mentioned. There was also the question of what we should do with the energy it released. Previously we had powered a record player; this time we had in mind a lamp, or an old radio playing The Shipping Forecast. None of us had ever been to Eday, an island of ten square miles with a population of just 130 people.

The wind picked up and the afternoon ferry was cancelled, so we headed over to Stromness on the other side of the Mainland to spend the night in the atmospheric Stromness Hotel. Enrique waxed poetic on the irony of Silicon Valley’s dreams of colonising Mars, when we were stranded ten miles from our destination by a bit of wind. But we made the best of it, and after a full Scottish breakfast with haggis on Sunday morning we drove back to Kirkwall and caught the afternoon ferry. We arrived after dark, windswept and seasalted, and followed the island’s only road to the only year-round accommodation, the hostel, where we met our documentary filmmaker, Aaron Watson. The trip north had taken three days, leaving only three days to build for the demonstration.

Build Day 1

We woke Monday morning to the sound of a large wind turbine spinning fast outside the hostel, telling us the weather conditions. In fact the island grid is powered entirely by renewable energy - Eday’s experimental and community-driven use of renewables, including wind, tidal, and solar, as well as storage in hydrogen fuel cells, is the main reason we were keen to visit. Even the electric heaters in the hostel are powered at certain times by energy overflow from the wind turbine outside. Everyone we met on Eday was extremely well versed in energy generation and storage, including the seven children of the local primary school who spoke knowledgeably about electrolysers and curtailment.

We met Clive, our local fixer and project partner with Eday Renewable Energy Ltd., after a solid breakfast of porridge and bacon butties. Before we set out to gather scrap materials and tools, he gave us a pep talk of sorts: ‘This may look like chaos. But I assure you the machine will be built, it will be demonstrated, and you will leave happy on the ferry Friday morning.’ In the car he pointed out the island’s landmarks and mentioned some of the people we would likely meet that day. As far as we could tell you were not allowed to have the same name as anyone else on the island - when a second Kate arrived she was renamed Katie, and the second Mike became Mick. This we decided was as good a definition of a small island as any we’d heard. Clive warned us that the community would need some convincing before they got involved. We should expect questions like: What’s in it for Eday?

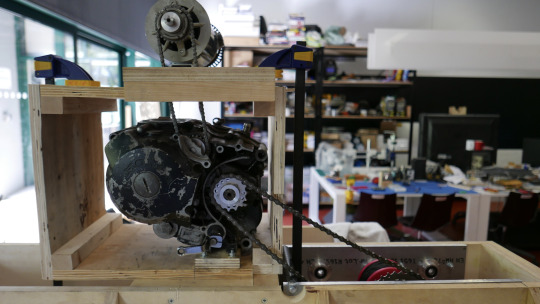

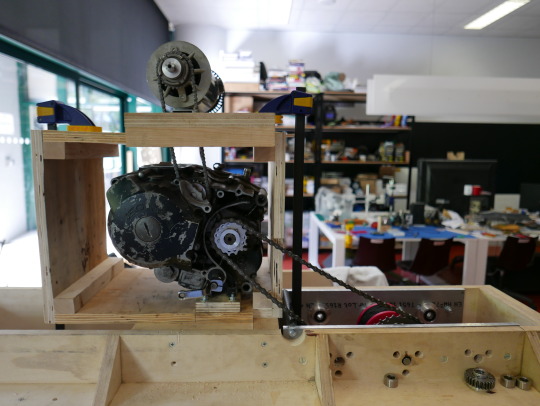

The first stop of the morning was the Old Church, which had been bought by a woman from London with big plans in the 1980s and has sat derelict ever since. Here we found an old motorcycle, a red Kawasaki, parked in the middle of the church amongst other scrap (a Super 8 camera, a record player, a typewriter). The bike had only 12,000 miles on the odometer, but it was buried under a thick blanket of corrosive pigeon shit, and all of its insides were seized beyond reasonable use. We took a lot of photographs. At the second stop, the New Church a minute down the road, we found a large brass bell salvaged from a sunken steamship. We thought we might use it as a weight for the gravity battery. Permission would have to be sought, Clive said. The third stop was an old mechanic’s back garden, full of rusted cars and a jumble of engine parts. ‘Did he die?’ someone asked. ‘No, just left the island’, Clive replied. James opened the hood of an old BMW and found a live rabbit inside.

We checked out the building site next, a shed by the pier used mostly for deliveries. It had a forklift and plenty of room - the first real success of the day. We would have to clear out twice a day when the ferry docked, but aside from that it was ours. We agreed it would do very nicely. Our other Eday contact, Andy, who works with Clive, met us at the shed. From there we drove to an old quarry on the far side of the island, a five-minute journey. As we walked around the site, staring up at the sheer sides from the quarry base, someone had an epiphany about making a gravity-powered keyboard. Andy, it turned out, not only knew how to play (he was currently the church organist), he had also been the keyboardist in an eighties band called Freeez, who had a number one single in the US dance charts (‘IOU’). We all agreed that if we could get hold of a scrap keyboard the issue of what to do with the energy released by the gravity battery was solved.

After lunch at the hostel we met some people from the community in a building next to the island shop. The key moment in this meeting was the suggestion that Mick, who was spotted leaving the shop outside, had an old motorcycle in his barn; someone ran out to talk to Mick and he kindly agreed to let us follow him home. He was a large man in a CCCP shirt, who told us in a Liverpool accent to mind the ducks and sheep. He opened the barn and dragged out an old dirt bike, its wheels clogged with hay; he used an axe to free up the front wheel, and four of us rolled it up the driveway in the rain and waited as someone found a van to bring it back to the pier shed. We were cold and wet, and the light was fading on our first day, but we had a motorcycle and a rough plan. We ate a hearty dinner at Roadside, the island’s former pub turned occasional restaurant (actually just a dining room in a private house), and then returned to the hostel to drink whisky and sleep.

Build Day 2

We arrived at the shed Tuesday morning at 9.05am to find several islanders already waiting in boilersuits, ready to work. We introduced ourselves, made some tea, and set up to start cutting into the bike, while Clive got on the phone to order a new chain from the Mainland - the only part the bike was missing. We quickly sourced some necessary tools from generous community members, including an angle grinder (Aaron the filmmaker’s favourite, because it made a photogenic shower of sparks), a lathe, and a socket set, and got to work. By lunch the bike was stripped, leaving only the parts necessary for the gravity battery - the frame, engine, and rear axle. In the afternoon two of us went to the school to give a workshop while the others stayed back at the shed. The wind blew and the rain poured down. Countless cups of tea were consumed. Soon the day was over, the children went home, the shed was locked up, and at the hostel Mohammed made his special dhal. It was Halloween night on a remote Scottish island, so obviously we watched The Wicker Man. More whisky was consumed.

Build Day 3

The challenge now was how to get the gravity battery over the fence and down into the quarry, our chosen site for Thursday’s demo. We noticed a large tractor - who did it belong to? Could somebody drive it there? Health and safety was still a headache that Andy was dealing with, negotiating with the property owners in England and the insurance company. It was blowing a gale all the previous night and all morning; the rain beat down on the corrugated iron roof of the shed, making it hard to hear anyone speak.

On the positive side, people from the community were beginning to get excited about working together on this strange and unexpected project. Old habits were shifting as people from different parts of the island who rarely spoke to each other met and pitched in as a team. Hamish and Mel, native Orcadians, came to join in and brought their son Robbie, an apprentice engineer. An old Casio keyboard was found, and after some minor tinkering was brought back to life. The chain arrived by afternoon ferry. Calculations were underway for rigging a pulley over the quarry edge. More people showed up, to work or to watch. Clive told us stories of moving to London in the late sixties, working in Carnaby Street, seeing the Stones in Hyde Park. ‘What brought you up to Eday?’ we asked. ‘Cheap innit’, he said with a smile. We met other southerners who said the same thing. But their attachment to the place had obviously gone very deep.

On Wednesday afternoon we went to use the lathe in the shed of a friendly guy named Mike, another Englishman and ex-submariner who lived in the old schoolhouse. Mike left a note in the shed telling us what to do if a blackbird showed up at the door - he had trained the bird to come in and ask for food when it was hungry. Sure enough the bird showed up, looking at us expectantly until we passed it some raisins and a biscuit. When we finished our machining Mike invited us into the main house. In what turned out to be one of the highlights of our week in Eday, Mike showed us not only a display he’d made on the history of the school, but also - leading us through a hole in the wall - no less than a full-sized model of the inside of a submarine, complete with salvaged periscope, control panels, and torpedo launchers. We walked through room after room, through sleeping quarters with life-sized mannequin sailors, until we reached the end and emerged back into the schoolhouse. We shook hands with Mike, somewhat unsettled by what we’d just seen, and returned to the pier shed.

That night at dinner we discussed our visit to Eday as a three-act play. The first two acts, we decided, had established the principal characters and their relationship to the world they lived in. The inciting incident of Act One was our arrival on the island, with a mad plan to build a gravity battery from scrap. The rising action of Act Two was the first three days of building, where we pitched in with the community to make the thing we’d set out to make - the spectre of public humiliation creating tension and driving us forward. The character arcs of ourselves and everyone in the community developed under this pressure; Andy and Clive even told us that relationships between community members had been altered - for the good - by our presence. People who hadn’t spoken to each other in years exchanged words; old feuds were put to rest or laid aside. For our part we gained insights about ourselves, our roles, and the nature of our work.

Every story needs a climax, and it usually involves collectively overcoming a crisis. So it was not unexpected that we should receive a phone call at dinner that night, the night before the public demo, telling us that the absentee landowner would not allow access to our chosen site, the quarry, without insurance - and negotiations with the insurance company had reached an impasse. Andy was trying his best to provide evidence of due diligence to both parties; but insurance is about predictability, and is naturally risk-averse. Testing a gravity battery made from scrap in an abandoned quarry with children present is not an ideal scenario from the insurer’s perspective. How could we bridge the gap between health and safety, on one hand, and daring innovation and experimentation, on the other? How could we achieve a satisfying resolution and leave happy, as Clive promised, on Friday morning?

Demo Day

Andy, as we mentioned above, was a professional musician in his previous life - he had played on Top of the Pops and The Old Grey Whistle Test. So when he sat down to rehearse for the demo on Thursday morning, perched on a wooden crate in shorts and hiking boots and a down jacket, tapping at the keys of a salvaged Casio, the other islanders laughed and jibed goodnaturedly: ‘You’ve come a long way, Andy!’ The crisis at the quarry had been overcome, or rather bypassed completely, by ten o’clock: just as the insurance problem was solved, we decided it would be easier to stage the demo at the pier near the shed, so that no major moving of equipment would be involved. Now momentum was gathering towards the final event and resolution.

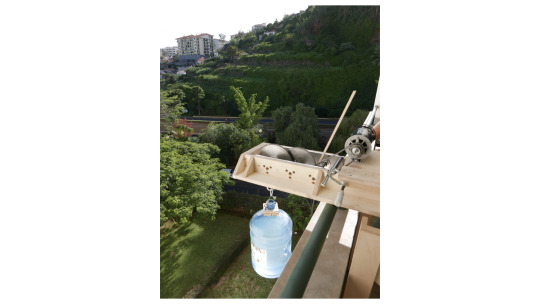

The demo was scheduled for after lunch. Word spread and by late morning a small crowd started to gather. We were busy with small jobs: like untangling rope for the pulley to suspend the mass, a 25-litre water container, from a long metal pole extending off the fork of a tractor Hamish had driven over from his farm. The motorcycle chassis that formed the heart of the machine was strapped to a wooden pallet. We only had to figure out how to lift the weight into the air - in Madeira we had used a solar panel, but that was not an option in Orkney. Various attempts were made, including hooking up the battery from Mike’s car, but with no success.

The school bus pulled into the parking lot in front of the pier shed and the children got out. They lined up in front of the crowd and showed drawings of the gravity batteries they had designed earlier in the week. One child broke down under the pressure and sobbed loudly, but eventually held up his drawing between shaking hands. The weather was calm and dry. We handed out Madeiran sweets to the kids, who wore reflective vests for safety. Everyone stood facing us in a semicircle and waited for the show to begin. At the last moment a solution was found: James improvised an attachment to a rechargeable electric drill and used it to drive a super low-gear winch, slowly raising the water container. It seemed a bit of a cheat - though in fact it wasn’t, since the island’s grid is powered by renewables - but the mass was now suspended, the energy was stored until needed, and that was the main point. We called for everyone’s attention; released the mass; wires were connected and the keyboard came to life. Andy played ‘Ode to Joy’, followed by ‘The Flintstones’ for the children. The performance lasted several minutes, then the keyboard fell silent at the instant the water container touched the ground. The crowd went wild. We did it again, and then again - the last time letting the kids take turns banging out some noise. It was a success. We cleaned up as dusk fell.