Text

DANGER WORD, directed by Luchina Fisher.

A zombie short cowritten by Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes, starring Frankie Faison (who you might recognize from The Silence of the Lambs or The Wire) and Saoirse Scott.

Crowdfunded, 2013. Relevant to some prior thoughts about The Last of Us and Train to Busan.

0 notes

Text

Zombie occupiers and BLOOD QUANTUM

I watched BLOOD QUANTUM (2019) after running across a reference to it on the former Twitter (I still look, I still look sometimes) by a professor who uses the film in his classes and has been intrigued at the way students respond to it.

The key bits in that convo are these:

She found the frank depiction of drug use, poverty, etc. on the reservation to be racist and said that even though the filmmaker was native the movie was offensive. I explained that the film was rejecting the “noble savage” trope that plagues representation of native people.

And that its attempt to realistically represent reservation life was pushing back against white audiences who want sentimental depictions of indigenous people communing with nature. After I explained that, I asked if they still thought it was racist. Almost every hand went up.

Having read that, I went in expecting the film to be a certain way - jaded, grimy, something like MARFA GIRL or KIDS with zombies on a reservation. It wasn't like that, though. It was really like WORLD WAR Z rewritten for asymmetrical warfare.

It's a war movie for an occupation.

Maybe the most interesting thing about the movie is what it doesn't say. Like NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, we don't really get any explanation for what's happening. Our first inkling is a fisherman gutting salmon he's netted and then being disturbed at them flopping and wiggling back to life. It's unnatural. But for this guy (and for a lot of the characters), unnatural is something they've been forced to live with for generations. The zombie plague is just another settler indignity, really.

The title is never really explained or referenced directly ... if you, like me, didn't recognize the phrase, "blood quantum" is a measurement of "of the amount of "Indian blood" you have. It can affect your identity, your relationships and whether or not you — or your children — may become a citizen of your tribe."

In this story, we get the impression that the members of the tribe are immune to whatever is making dead people rise up running and hungry. And the reservation is on an island in a river. It's not easy land to commute on and off of, but it's pretty easy to defend.

It seems like what a non-Native filmmaker would have done, and maybe what the prof's students would have been happier with, would be to layer on a couple of speeches about ecology, and then build a plot around desperate white folks leading an assault to try to take the reservation over. But instead, we've got something far more cynical and jaded.

It's taken for granted that the rest of the world has gone to shit. The only 100% non-Natives we see are refugees (mostly sick and dying) or else ravening zombie hordes. The conflict of the film is ... what do we do with them? And most of all, how do we draw a line between them and us? Who belongs here - and how do we decide?

Of course, disagreements over that problem lead to violence. Nearly every character in this film has been living with trauma since before the dead started rising. This is not done allegorically, like the race relations in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. It's right there on screen, stuff you might have read in the police blotter in the local paper 10, 30, 50 years ago. Delinquency and drugs. Despair and divorce. Even the sheriff and the doctor can't keep their personal lives together, for all the good they do for their communities.

Where the film succeeds is in making that the source of horror. There's some disturbing stuff beyond the gutted salmon flopping on the cleaning table, but the worst of it is people making grim decisions about each other and doing terrible things to each other and realizing, "Yeah, I can see why they'd do that."

The central figure here is a pregnant girl. She's the white girlfriend of the Native cop's troublemaking son. Whether her baby has enough "Indian blood" to survive becomes a big question. Who belongs here? Who decides? And will the wrong decision mean we get eaten from within, either personally or as a community?

It's a film that could maybe be remade in any occupied land (Ireland during the Troubles, Sri Lanka with the Tamil Tigers, South Africa under apartheid, and of course, now, again, Gaza and Israel). Anywhere "us" and "them" become life-or-death definitions, and where the act of defining comes with its own cost in the blood of the innocent bystander ... if you even believe there is such a thing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Messiah of Evil and the Word made Flesh.

This film was not as "bad" as I was expecting. The frequent references to "surreal" in write-ups had me anticipating nonsense or non-sequiturs, encounters with gore trumping character development ("why would you DO that??") or plot ("how did THAT happen??") ... but Messiah of Evil didn't actually fall prey to any of that. I think if it had been more "bad" it would have been remembered better.

What it is is creepy. Dreams and memory are a theme, as well as using traces of the present to reconstruct the past. It's a B-movie, so there are some limitations. And, reading up on it after watching, it's easy to see that the filmmakers (husband and wife team Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz) would also have been Howard the Duck fans (they co-created the famous Marvel flop). This film has some of the same bizarreness of the original comic books without any of the absurdist humor.

It's also got the same sincerity under all the strangeness.

Is it a zombie movie? It was, for a while, released under the alternate title Return of the Living Dead, no relation to the 1980s franchise, and semi-successfully sued by George Romero's folks for infringing on his film. Some commentators seem to want the cannibals in this to be vampires, but they're not. They eat flesh. The gradually-unveiled origin story lies in the Donner Party expedition and a preacher who survived by consuming his companions and turning to a new god to worship.

There is a theme of consumption - the key scenes are of ordinary-looking suburbanites killing and eating attractive, hedonistic hippie chicks in a grocery store and a movie theater. And there's also a theme of infection.

No, not infection. The condition is a physical condition - body temperature drops, victims become hungry for flesh and immune to pain, and there's some kind of, if not decay, then at least playing host to the worms and bugs and creepy-crawlies associated with rotting corpses. But the condition is a symptom of a spiritual understanding. Dreams come, and compulsions to stare at the moon. Poetic diary entries start to take on literal significance. It's a film about conversion.

There's an apocalyptic promise in this one, much like the "when there's no more room in Hell..." line from the later Dawn... and Day of the Dead Romero movies. Only those seem to be a little more mathematical: This many dead people can infect and/or kill that many living people, making them become dead people who then infect more... etc. Messiah of Evil really is about a messiah who returns, in an experience that seems both literal (the dark preacher walks back out of the ocean a hundred years after he walked into it) and also personal, spiritual. The horde of cannibal converts are waiting for the signs in the sky to be right and their spiritual leader to return before they march inland and spread to new towns. They don't seem to be particularly hungry about it. They seem to want to spread the word.

That puts the ghouls of Point Dume in an odd category. They're never referred to as zombies, or vampires, or anything other than cannibals. They don't seem to be entirely mindless; they seem normal, until they get close enough to take a bite. They're possibly similar to the Deadites of the Evil Dead franchise, which are basically people possessed violently by demonic entities who leave and return almost randomly. But they're not even interested in scaring their victims. A few folks are hunted, like rabbits by a pack of dogs, but these hounds aren't in it to scare the rabbit. They just want to eat it, because that's what they do.

1975 seems like a year when the idea of "cults" was gaining in currency, and maybe also when anxiety between "normal" society - church, business, maybe even self-help books - and "cult" society - offering pre-fab meaning in an ever-more meaningless world - was mounting. The fact that this is a movie that featured what I have to read as a polycule of longhairs as "the good guys," alongside a bohemian painter's daughter seems really central to the horror here. And there are Lovecraftian echoes - the old preacher in the sea, a half-mad drunk who reveals the town's religious secrets to outsiders before meeting his own doom - that evoke ideas like "the old gods" and the Church of the Starry Wisdom, which, if you remember, set up shop in a Christian church in order to open up the facility to pre-Christian religions.

These are not Voudoun zombies like Sugar Hill, they're not demonic zombies like [REC], and they're not even natural law snapping back after being pushed too far like in World War Z. I think they're cult zombies.

0 notes

Text

Zombie Modernism, the End of History.

One of the secrets of zombie fiction -- and I mean here the post-Romero, post-apocalyptic zombie, which may well be the inevitable form of the zombie (since, at least, it's the one we're living with now) -- is that we are drawn to the post-apocalyptic nature of these stories because we are already living in post-apocalyptic times.

Think, maybe, of the Apocalypse of John, also known as the Book of Revelation. The usual, fundamentalist reading of this weird visionary volume is to read it as a prophetic warning of things yet to be -- a literal(-ish) depiction of world-ending plagues, supernatural locusts, and many-headed beasts that lie waiting in our future. There are two traditional allegorical readings though.

One is as a political allegory for things contemporary with its writing: the Number of the Beast as a coded reference to Emperor Nero, the seven heads referring to the seven hills of Rome and so on. Another, though, is as an Early Christian answer to the Bardo Thodol, a vision of a soul's migration from the mundane world through a personal, subjective universe of spiritual warfare and ultimately reaching the Kingdom of Heaven. In other words, the End Times are something waiting for each of us, individually, one at a time. We are all on the way to our own inevitable apocalypse.

It is perhaps not a comforting thought for everyone, not unless one is willing to embrace the idea that our day-to-day lives can be imbued with deep and paradoxical spiritual meaning.

That's one way in which we can be said to be living in post-apocalyptic times, or at least living in an apocalypse of our own making. More literally, though, there is another sense in which we are in an apocalypse, or a post-apocalypse. It has to do with the significance of World War I.

The Great War was, at the time, a global eruption of madness, blood, and pain that proved conclusively that the progress of Western Civilization was a lie, or if not a lie, then at least inhuman and amoral. A civilization that could build machine guns and tanks, create factories for automated death, and then send thousands of human beings to be fed into the machinery on the strength of a few signatures on a sheet of paper made by a few close cousins whose own lives were never at risk ... was not all that civilized after all, was it. The philosophical statement that "God is dead" had already been made, but here was the proof.

The war was in some ways the cradle of Modernism, right? The birth of Surrealism in Andre Breton's veteran's psychiatric hospital goes hand in hand with the desire for a clean, well-lit place. The yearning to strip away adornment and see forms for what they are and not what they resemble ... this is an apocalyptic urge. "Apo," to remove; "Kalyptein," a veil.

The fascination with the zombie is a Modern fascination; the zombie apocalypse is something we're already living through. Society has been breaking down since 1914. We walk, we feed ourselves, but are there souls inside us?

Do we watch zombies march mindlessly through the ruins of civilization so we feel less bad about our own mindless marches through our own ruined civilization?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

First thoughts on The Last of Us

I've only seen the first four episodes, but I think I've got a handle on what makes THE LAST OF US different from previous zombie fiction. I'm not sure how to string these thoughts together yet, but I want to jot them down to see what patterns emerge (like fruiting bodies from a mycelial network, of course).

* It's firmly lodged in the apocalypse-as-family-dynamic subgenre of zombie films, like the first few seasons of THE WALKING DEAD, 28 WEEKS LATER, and even moreso TRAIN TO BUSAN (previously discussed here).

* Rather than extending out of melodrama like... well, most zombie movies from NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD on; lots of repressed anguish, psychological subtext, close-ups on sweaty faces making bad decisions... and rather than borrowing dynamics or settings from war movies like DEAD SNOW, DAY OF THE DEAD, OUTPOST, or the final third of 28 DAYS LATER... this series is pretty consciously taking its cues from Westerns. It's not exactly TRUE GRIT in the zombie apocalypse, but it's close.

* The Western trappings change the deeper themes at play. Westerns are always about remarkable individuals making existential decisions, whereas nearly all zombie movies are about social systems and the breakdown of interpersonal hierarchies. The zombies (or fungally infected) in THE LAST OF US don't seem to travel in herds. It's an epidemic, but in this story, the infected are all networked together. We're told early on that what one perceives, others will react to even over a distance of miles. This isn't a mathematical or statistical model; it's biological. Rhizomatic.

* The design work is outstanding, and unlike nearly every post-apocalyptic fiction I've seen (with the possible exception of STATION ELEVEN) the photography seems to take real joy in life. This isn't THE ROAD WARRIOR as much as it is AFTER MAN. Cars aren't burnt and blackened as much as they are green with moss and weeds. City streets have been reclaimed by wilderness. Of course, this visual choice is a natural extension of a schema in which the infectious agent is a fungus rather than a virus. A virus is a biological machine, not even truly alive. Cordyceps fungus is alive, too alive; it only wants to dominate a brain and an animate creature's neurology in order to reproduce itself. The horror of THE LAST OF US is that everything grows, not that everything breaks down.

* Because it is a family story, and a story about life, the triumph of life over society itself, it is also a love story. The third episode with Nick Offerman is ... well, I won't spoil it, but it's really about emotional life flourishing in the face of a world that is unkind, crude, and dismissive of the value of the individual. That value is developed not just for every person in their own right (in true Western fashion) but also expressed in the value people find in each other. Humans are networked too, only by emotional bonds, not by mycelium. (Of course one of two main characters is a prepper. Who you let into your bunker makes for a great character-shaping tool.)

Looking forward to where this fiction goes next.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've just enjoyed the fellas at Weird Studies discussing the "deadite" zombie/demons in Evil Dead 2.

The conversation spent some time on the zombie as a figure of the inanimate somehow wanting to be animate, the desire of material things to have a spiritual dimension, taking some direction from Cannibal Metaphysics by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. (In this way the theme is similar to the Tower of Babel story, in which humanity raises an earthly monument in an attempt to make bricks and stones like Heaven, the kingdom of spirit.)

There was also some discussion of puppets and puppetry along the same lines, riffing on Victoria Nelson's The Secret Life of Puppets.

The zombie - and especially the zombies in this film, in which they're really just projections of an extradimensional force that also animates lamps, books, and body parts - is a cipher for the relationship between spirit and matter, the hunger we perceive of inanimate things to be like people, to have desires and dislikes, and to move away from or toward them.

It's good stuff.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Soullessness: Zombie Theology.

Besides the post on the corpse-citizens of ancient China, I don't think I've spent enough time thinking about what I guess could be called a theological critique of the figure of the zombie.

I was nudged to think about this by an RPG podcast which had players leaning heavily into the soullessness of a zombie menace, and in which one of the player characters was a sort of vampire that drains life-force (or, really, something a lot like qi or pneuma) rather than blood.

A person needs a soul, unless they're not a person any more.

There's an argument to be made that the zombie as we know it today is a product of modernity, of Nietzsche's proclamation that God is dead. Because if that's true, if the Holy Spirit is absent, then what do we make of the soul, the spirit inside us? That seems to be one of the big questions of modernity or post-modernity, and maybe one of the hinges that's turning that 20th-century stuff into the New Sincerity/hauntology discourse of the 21st century.

It's also something that I think has changed between the creepy zombies of the 1960s-1980s and the less-central figures zombies have become in more recent stories like Army of the Dead or The Walking Dead. We don't spend any time in those fictions considering the state of zombie-ism, of being dead yet animated... animated, yet without personality.

From around the 1990s, I think, a lot of those questions or anxieties seem to have been shifted onto the figure of the vampire. Thinking now of the whole importance that "soul" took on in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel - the idea that the soul is what made the person THAT person, and that once it was removed, the person still could possess memories and a name and the ability to act and interact, but was not that person any more. Soul was identity on some deeper level.

Zombie movies treat the soul differently. Strange that it has become less of a central question in zombie fictions just as themes like "hauntology" become more significant in horror fictions and critique. Can one have a folk horror zombie? I think something like Sugar Hill comes pretty close. The old-fashioned, pre-Romero religious zombie might be a potent starting point for new ways of thinking through this. Memory, return of the repressed... those things come up in stories of ghosts (like the marvelous story "The Murmuring" in Guillermo del Toro's Cabinet of Curiosities) and demonic possession and deal-making (Hereditary, Mandy).

But there's still more that the zombie can say about this, I think. I'm not sure exactly what yet.

#cartesian dualism#zombie theory#zombie theology#nietzschean zombies#zombie origins#ghosts in the machine

0 notes

Text

"Zombie Movies Where Everyone Has Seen Zombie Movies But They Get Things Horrifically Wrong Because Of Them."

A Twitter thread by Alexandra Erin outlines a horror story based on the public thinking a zombie plague has finally broken out, when in fact it's something quite different. It starts:

Imagine there's an infectious agent (probably a parasite) whose life cycle in the human body is that it spends like 24-72 hours maturing, and meanwhile it interferes with motor and neurological functions in such a way that the person can move stiffly, has no fine motor skills...

...in the sense of not being able to voluntarily move their fingers, and similarly they can vocalize but can't control the vocal apparatus to do anything more than wordlessly groan and moan. The host is very numb and can't feel pain to notice or react to injuries.

And while most of their senses are blurred and dulled, their brain becomes very sensitive to the smell of humans and any impulse they have to move towards humans specifically or generally (for help, because they recognize family, etc.) is magnified by the parasite.

But this is because at the end of the infectious period, the parasite's parent organism cells in the host dies and they want a lot of other hosts around for the spores they've been gearing up to produce to infect. The infection is *not* spread through bites or contact.

And when the life cycle ends in their body, the formerly infected are exhausted, dehydrated, likely covered in abrasions or worse, and suffering severe inflammation, but very much alive. The infection is only ever incidentally lethal.

In this scenario, the scientists and doctors and leaders who are urging people to remain calm while they study the disease before leaping to conclusions would 100% be right, but zombie movies would have prepared folks to think the people saying that are clueless at best....

This is just how it starts - it gets worse (or better) from there.

0 notes

Quote

Zombies are cinematic inscriptions of the failure of the 'life/death' opposition. They show where classificatory order breaks down: they mark the limits of order. Like all undecidables, zombies infect the oppositions grouped around them. These ought to establish stable, clear and permanent categories. But what happens to 'white/black', 'master/servant' and 'civilized/primitives' when white colonialists can also be the zombie slaves of black power? Can 'white science/black magic' remain untroubled, if what sometimes works against a zombie is white magic, the Christian religion, the power of love or superior morality? How certain is the opposition 'inside/outside', if the zombie's internal soul is extracted and an internal force becomes its inside? Is there any security in opposing 'masculine' to 'feminine' and 'good' to 'evil' when the zombie is desexualized and has no power of decision?

"The zombie is therefore fascinating and also horrific. It poisons systems of order, and like all undecidables, ought to be returned to order. In zombie movies, this return to order is difficult. For a classic satisfying ending, the troubled element has to be removed, perhaps by killing it. But zombies are already dead (while alive) you can't kill a zombie, you have to resolve it. It has to be 'killed' categorically, by removing its undecidability. A magic agent or superior power will have to decide the zombie, returning it to one side of the opposition or the to the. It has to become a proper corpse or a true living being. There are other endings, less final. The zombie might be ineradicable, they might return. Perhaps undecideability is always with us. If not figured in the zombie, then something else: ghosts, golems or vampires, between life and death.

From Introducing Derrida by Jeff Collins, via The Inevitable Zombie Apocalypse, via my old friend Camel.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The pandemic turned communities into haunted landscapes. Coffins ran out as bodies piled up everywhere. Stores, theaters and schools were closed, and wagons were pulled through the streets to collect corpses. Funerals were often impossible to organize, and across the country, mass graves were dug to accommodate the many dead....

"In his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft was surrounded by the pandemic’s ghastly atmosphere. As one local witness remembered, “all around me people were dying… . [and] funeral directors worked with fear… . Many graves were fashioned by long trenches, bodies were placed side by side”; the pandemic, the witness laments, was “leaving in its wake countless dead, and the living stunned at their loss” (letter by Russell Booth; Collier Archives, Imperial War Museum, London).

"Lovecraft channeled this climate into his stories of the period – producing corpse-filled tales with infectious atmospheres from which sprang lurching, flesh-eating invaders who left bloody corpses in their wake.

"In his story “Herbert West: Reanimator,” for example, Lovecraft creates a ghoulish doctor intent on reanimating newly dead corpses. A pandemic arrives that offers him fresh specimens – and that echoes the flu scenes of mass graves, overworked doctors and piles of bodies. When the head doctor of the hospital dies in the outbreak, Dr. West reanimates him, producing a proto-zombie figure that escapes to wreak havoc on the town. The living dead doctor lurches from house to house, ravaging bodies and spreading destruction, a monstrous, visible version of what the flu virus had done worldwide.

- Prof. Elizabeth Outka, author of Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature, on how the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic helped create the figure of the zombie... in H.P. Lovecraft's Herbert West - Reanimator. (This was published last October, in the time before COVID-19.)

0 notes

Quote

When Lovecraft was writing, his strident expression of an almost misanthropically cruel scientific atheism, alongside his portrayal of the human body as profane, dead clay powered only by crude, electrical impulses, must have seemed a shocking, or at least provocative, statement of intent. Sixty years later however, such a stance was pretty much the default expectation for an audience of horror fans shaped by the work of Romero, Fulci and Cronenberg (not to mention the increasingly grotesque run of European Frankenstein movies which proceeded them in the ‘60s and ‘70s). Wasting time allowing the characters to pontificate about it would simply have been surplus to requirements. Zombies, man - we get it.

Breakfast in the Ruins has taken a deep, two-part dive into Herbert West - Re-animator, one of Lovecraft's earliest and most troubling tales, and what it took to get it adapted into one of the biggest horror films of the VHS era.

Of course, between the time that blog post was written and my reading it, the section about how old-fashioned it seems to modern readers to have a city being affected by a plague... well, you know. It's less old-fashioned now than it was in the 80s.

Well worth a read. Part 1. Part 2.

0 notes

Link

Adding to my reading list now: John Cussans’ Undead Uprising.

0 notes

Quote

Unlike the werewolf, Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster – creatures born in Europe – the zombie’s history is rooted in the United States and it origins came during a time of blatant racism and also competition for world power status.

“Part of my central thesis is that I think we wanted a monster of our own,” he said, noting that during the 1930s and 1940s, the United States had become an imperialist power and that its nationalistic character naturally extended into popular culture.

Bishop’s research seeks to unmask "a lot of imperialist racism and lack of tolerance – the idea that when the Western culture encounters a different culture,” he said, “the immediate thing to do is to make that culture seem threatening or horrific.”

Though the film resulted in the zombie’s ensuing popularity, the creature today is often portrayed quite differently than its original self.

Numerous directors have used the zombie to make social critiques and metaphors while the creature has also been portrayed in a whimsical and comedic way, as was evidenced by films like “Zombie Love” and “Shaun of the Dead,” which was inspired by George A. Romero’s classic 1978 film “Dawn of the Dead” – Bishop’s all-time favorite horror movie.

In film, the zombie saw a “revival” during the 1960s and 1970s, Bertsch said. In recent years, numerous popular films in the United States and in the United Kingdom have centered on the zombie or incorporated zombielike characters.

“The voodoo is pretty much gone now, but the idea of infectious cannibalism is still there,” Bishop said.

UA doctoral student (in 2008) Kyle Bishop on zombies in American cultural history, from UA News, "The Zombie: A New Monster for a New World." I'm with him on the voodoo zombie analysis, but I wonder how he links those slave-magic zombies to the infectious cannibal zombies.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Another zombie story from Hurston's *Tell My Horse*. They're mostly linked with labor in her book - make me wealthy, I'll become your zombie; I need cheap laborers to do hard work (but never feed them salt!). This story has them linked to marriage, though. Not quite "sex zombies" but somehow - metaphorically at least - prisoners of the church, perhaps?

0 notes

Photo

From Zora Neale Hurston's ethnographic study, *Tell My Horse*. Little girl zombies appear again, later in the chapter. She also describes people making a bargain with a bocor- have the loa make me wealthy now, and I'll be your zombie later.

0 notes

Text

Tractatus Train to Busan

[Note: Spoilers throughout, for all kinds of films. If it's about zombies, trains, or children, there's a chance I've mentioned the ending here.]

Train to Busan represents a new sub-genre of zombie film, one that may well grow to prominence.

It is both new and not-new, both familiar and unfamiliar, telling the same kind of story using the same elements, but with a slight difference in emphasis that results in a radically different... something. Perhaps "emotional value."

It is a zombie film in every important way. But it feels like something else as well.

It is as different from Night of the Living Dead as is the underwater Nazi zombies of Shock Waves, but maintains as close a thematic and narrative connection as does 28 Days Later. (There is more to consider on the sequel 28 Weeks Later.)

The site of difference for Train to Busan is located in the thematic zone of family.

The zombie genre is defined by its concern with social relationships: it has always been about

consumerism

social status

authority vs. the masses

tension in traditional social units, especially families

Because of horror conventions, the family in the zombie genre is usually presented as tainted or in some way inauthentic, unreal.

One of the archetypal locations is the family home or cabin, a place where one retreats to have "family time," and where family secrets are stored in attics or basements (as in Evil Dead or, arguably, Dead Snow; most of the storyline of Night of the Living Dead involves the conflict over whether the retreat with the nuclear family to the cellar is wise).

The most impactful scene in Night of the Living Dead is the little girl turning on her misguided parents. This is the image that is quoted numerous times in the genre, from [REC] to Warm Bodies to The Walking Dead.

The narrative engine for the first few seasons of The Walking Dead was fueled by marital infidelity, spousal abuse, and where the hell did Karl wander off to this time; in Shaun of the Dead, the choice is always made against domestic life in favor of heading down to the pub and spending time with "real" friends. You get the idea.

Yet, against the "badness" or insufficiency of "real" families, these characters very often form ad hoc families - taking in lost children, forging sibling-like or spouse-like alliances as society breaks down, sharing food around a table or a campfire. Zombieland, Day of the Dead, Ash vs. Evil Dead, 28 Days Later... all overtly rely on intentional families, families that are made or chosen rather than being produced through biology or traditional society.

Train to Busan reverses nearly all of this. But not the full 180 degrees.

It has both the traditional family and the broken family (the husband is separated from his wife, alienated from his daughter; the husband lives with his mother; the mother urges him to reconcile with both wife and daughter).

It has both "natural" family and "intentional" family (the father-daughter team are thrown together with the blunt Sang-hwa and his pregnant wife, and in various scenes swap roles of father/protector, mother/wife, daughter)

It has social breakdown based on familial love (the elderly woman who, upon seeing her sister zombified, allows the horde into her car - overrunning those who coldheartedly excluded her sibling from safety)

Most of all, it has the little girl. Soo-an. Who is beautiful.

There have been other exceptions, in which family plays a different part in the zombie story:

Revenant featured an extreme version of the theme: "They're our loved ones, we must care for them in undeath as we did in life."

But in Revenant, they also weren't trying to feed on the living - uncanny, but not actively dangerous, or even infectious. In Train to Busan, the zombies are infectious, hostile, and fast.

28 Weeks Later featured a half-zombified (sure, "rabid," whatever) father crossing the country to be reunited with his beloved children.

But, like the undead Romeo in Warm Bodies, he retained some portion of his memories, of his self-control, of his self full stop. The zombies in Train to Busan are (sure, "rabid," whatever) genuine zombies - they are mindless and attack loved ones and strangers indiscriminately.

In Fido, there's a happy family at the heart of the film.

But this film is a high-concept exercise, played mostly for laughs: "What if we mashed up Lassie with Night of the Living Dead?" The family elements are part of the 1960s-kid's-adventure genre. Fido is an aesthetic success, if you like the joke, but is not creating a new thing.

These, then, represent ancestors of this new sub-genre. Forerunners. Not yet exemplars.

Another key to the new genre Train to Busan defines (or should define) is transit.

It takes place on a train, so shares something of the venerable action-on-a-train genre (Murder on the Orient Express, Silver Streak, Horror Express, From Russia With Love).

It also shares a frantic sense of pacing and claustrophobia with transit-thrillers like Speed or Con Air.

These are films that critique the way in which our daily lives - the mere action of going from one place to another, the simple act of movement - become mechanized, constrained, unnatural. Our industrialized, technologized society is highlighted, in a way, but not with anything as flashy as killer robots or possessed diesel engines. Instead, it's as banal as a daily commute. The deadly, miraculous machines that surround us are part of the scenery.

Perhaps the ultimate examplar of the transit-horror (or transit-dystopia) would be Snowpiercer, which is not a zombie film in the remotest sense - but has an oddly similar set of concerns: the end of society, exaggeration and breaking of government power and social class differences, the mass of humanity reduced to (or overtly expressing) mathematical principles in the way we reproduce and we eat.

Snowpiercer is an allegory; our world or our society is the train. Train to Busan is not so simple.

(It should also be mentioned that while being on the train is not an element of 28 Weeks Later, train stations are, aren't they? Unless I'm misremembering. That franchise does love a subway tunnel. The trains haunt those films, like ghosts. Why?)

(And again, in The Walking Dead, one season was consumed with the quest to reach "Terminus," as if this train station was the last outpost of civilization rather than a place where humanity eats itself.)

The train has become a potent symbol - a sign that's heavy with meanings, sometimes contradictory ones:

Ultra-modernity, but with nostalgia (as in the mighty engines of the Hogwarts Express).

Colossal machines - faster, stronger, heavier than anything on a human scale - that are also in some ways fragile or on the brink of collapse. One of the hallmarks of the cinematic train is its spectacular wreck, sometimes as the film's climax: Silver Streak and Snowpiercer might have entirely different themes and wholly different aesthetics, but they end with tangled steel and steaming debris.

Travel (so, new places), but also routine (so, the same old thing) - timetables are always important, and commuting is often important too.

Business, especially corporate business (or, in the case of Harry Potter, boarding school - still a uniformed space with paperwork and expectations set by supervisors), but also vacations.

Community, but also alienation.

The iconic joke (or urban legend) about the two passengers eating each other's biscuits from the tin, neither one daring to ask the other how he (or she) presumes to take his own sweets... this is also a joke about trains. The faces that become familiar (or even family-like) by sharing that closed space over time - they are also divided from one another. There is always an expectation of silence, or at least of not intruding on the other's space.

Perhaps (and this is the sense that Snowpiercer takes as its central theme) the train is best thought of as a closed environment filled with strangers. Claustrophobic (and boring) and agoraphobic (and overwhelming) all at the same time.

This contradictory nature means that in many ways the train, suitably enough, defines an axis of meanings. It's on a symbolic track, running both ways.

The zombie also functions as a contradictory figure on axes of meanings as well - dead/alive, familiar/alien, operating in huge masses/breaking down society, revealing hidden truths/eternally unknowable.

The beauty of Train to Busan is that it takes on not one but two sets of axes of meanings - two bundles of anxiety-producing contradictions - and resolves them by using the third theme, of family relations.

Note here that I'm seeing "anxiety" as a close relative of "humor" and of "wonder" - states of mind relying on contradictions.

Note also that I'm perfectly aware that this may be an absolutely subjective response on my part - as a father, I know the kind of guilt the main character feels. The final, central contradiction: Sometimes, the only way to demonstrate your love for your child is by your absence, or so it seems. You go away to do the thing they cannot see. You alienate yourself from them (bastard!) for the noblest of motivations (hero?).

This is the ground that Train to Busan occupies. It is one of the warmest zombie films ever made. It manages to be genuine and sweet while still having train wrecks, martial law, and cloudy-eyed cheerleaders chomping on sports heroes. It'll be interesting to see if - or when - another filmmaker tries to do something new with the same three elements: zombies, trains, families.

0 notes

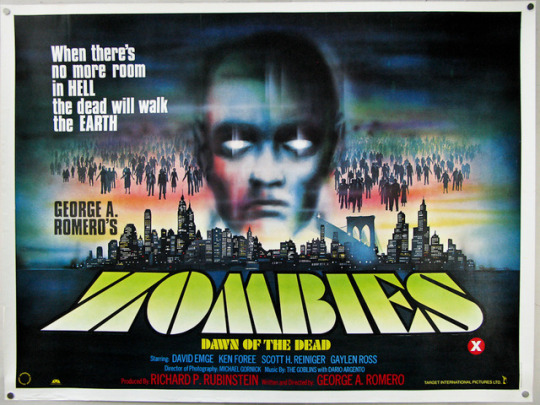

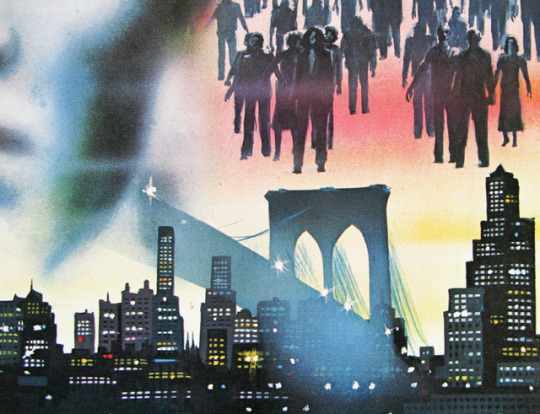

Photo

This poster encapsulates a lot of the genre's themes rather well. Crowds, urbanity, facelessness....

Tom Chantrell poster art for George Romero’s 1978 film Dawn of the Dead.

RIP George Romero.

627 notes

·

View notes