Text

“My Red Homeland”: Jewish Contemporary Art

Anna Nesterenko

“The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them”

-Mark Rothko

Shooting into the Corner, Anish Kapoor

In many cases, especially connected to the migration and living among the foreign ethnicities, as it is happens widely with the Jews through history and nowadays, categories of ethnicity and nationality serve as principles for organization of life and social contacts. While these categories are socially constructed, they have objective consequences for access to important resources - including housing, political resources, and opportunities in the labor market (Chong, 2011).

These processes occur both outside the community and inside, when its members distinguish themselves from the rest during the interactions, even with the strangers, (Tavory, 2010). Drawing up such boundaries is based on the ascription and evaluation specific characteristics, which are considered to be significant to the group of people or in our case, the group of art (Barth, 1969). According to Bourdieu, these symbolic and cultural factors are very important in the social construction, as far as they contribute to building a hierarchy in society and allow certain agents to occupy a dominant position that can result in symbolic violence - the imposition of their cultural and symbolic practices (Bourdieu, 1984). When it comes to the art, what is considered to be national is always really a question of social boundaries, that can be described as the “conceptual distinctions made by social actors to categorize objects, people, practices and even time and space” (Lamont & Molnár, 2002). However, the attempt to make a certain homogenous image ends in failure because in reality the concept of “national” in reality is always heterogeneous.

Jerusalem, Moshe Mizrachi

In the past, in spite of the doubts about the theoretical possibility of Jewish, acuteness of this question contributed to its unexpected rise in the XX century, when Jewish identity became an increasing concern in the visual arts (Silver & Baskind, 2011). At this time avant-garde Jewish groups, each with its own concept, arose throughout Europe, finally freed from the political oppression: the artists gathered, argued on this topic, founded magazines and exhibitions devoted to Jewish art in Paris, Berlin, Warsaw.

In other words, it was the process of national self-ascription that was accompanied by an explosion of both reflection on this topic and Jewish artistic creation. The names of Marc Chagall or Chaim Soutine are widely heard, but many of the artists who participated in this process (for example, cubist Max Weber in America or avant-gardist El Lissitzky in Russia), later became classics of European modernism, even though their Jewish dimension usually remains understudied, as far as for some of them the passion for avant-garde art reflected a break with Jewish ancestry and Judaism, especially due to the ideology of atheism in the Soviet Union (Orlov, 2008).

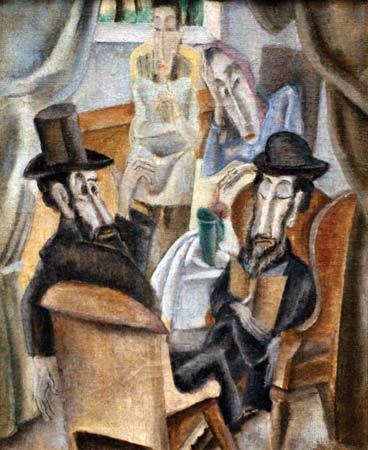

Book cover for "Chad Gadya", El Lissitzky

Sabbath, Max Weber

In the XX century, several approaches emerged to how to express the Jewish contribution to art. One of them, which is popular now in Israel, is an exhibition based on the presence in the work of Jewish artists of the “Jewishness” – their very own experience that is the personal history experienced by the artist as a Jew. This story can either enter creativity directly - for example, as the experience of the Holocaust, - or it can also somehow indirectly affect the choice of scenes or style in some complicated way.

Svayambh, Anish Kapoor

“He was antisemitic and I'm Jewish. Who cares?”

-Anish Kapoor on Wagner

In the February of this year the winner of The Genesis Prize, the so-called "Jewish Nobel Prize", which “recognises individuals who have attained excellence and international renown in their fields and whose actions and achievements express a commitment to Jewish values, the Jewish community and the State of Israel”, was announced Anish Kapoor - a British sculptor of Indian-Jewish origin (The Guardian, 2017). Kapoor said that he would donate a million dollars of the prize to help the refugees: “As inheritors and carriers of Jewish values it is unseemly, therefore, for us to ignore the plight of people who are persecuted, who have lost everything and had to flee as refugees in mortal danger” (The Guardian, 2017).

And canceled the rewarding of the Prize because the celebration is “inappropriate” in the face of the war in Syria “on Israel’s doorstep” (The Jewish Chronicle, 2017).

Anish Kapoor was born in Bombay in 1954, in family of Hindu and Iraqi Jewess. His mother’s relatives are Jews, immigrated to India from Iraq in the 1920s. In 1978, his first exhibition was held in London at the Hayward Gallery. Ten years later, he is already an acknowledged artist, a prizewinner at the Venice Biennale, a laureate of the Turner Prize. In September 2009 Kapoor became the first artist whose personal exhibition was organized in The Royal Academy of Arts during his lifetime (The Jewish Chronicle, 2017).

To set an example, of the modern artist suited into the third approach who express his own stories as the Jew, I would like to focus on him and explore the way he represents it in his artworks and how it is perceived by the both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences. Analyzing a number of interviews with Kapoor and the reviews, we can distinguish several main frames used in order to evaluate him and his artworks: the view from within the Jewish community on Kapoor as a Jew, in the first place, regardless of the positivity or negativity of the review; the frame that focused on the artworks themselves; and the one that explore his personal views, mostly political, including ones that are embedded into the artworks.

The authors and magazines, mostly connected to the Jewish community, such as The Jewish Chronicle, Jewcy, Haaretz, Jewish.ru, etc. prefer to focus on the Jewish origin of the Kapoor and emphasize it: “Most notoriously, in 2015, his work at Versailles was defaced several times with anti-Semitic graffiti, and when Kapoor elected to not remove it to highlight underlying problems, a right-wing politician successfully sued to force him to cover up the vandalism” (Jewsy, 2017).

Anish Kapoor, Dirty Corner

Kapoor himself, while not denying the importance of the Jewish question, tries to avoid discussions about the influence of his origin and especially religion on his art:

“-…And you are part Jewish. Were you formally taught these things, were they formally or casually talked about in the family conversation?

-…But my parents were fastidiously a-religious. So while some of this was around, its much more that I feel that the symbolic world, which I insist is the nub of a problem for an artist like me, is latent in most actions I would wish to make as an artist. And the work is to find that latent content” (The John Tusa Interviews, 2003).

This is especially noticeable in publications related to the outrage on the part of Jewish society, when Kapoor were developing a design of sets for the new Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde: “And many of my Jewish relatives and friends say: ‘How can you?’ Honestly, in the end, one somehow has to put that aside” (Jeffries, 2017). He responds to all these criticism: “In the end, who cares if the artist is a nice person?” (Jeffries, 2017). For him, some practical actions are obviously more important, he actively expresses his views on the pressing issues of our time, both personally and in his art.

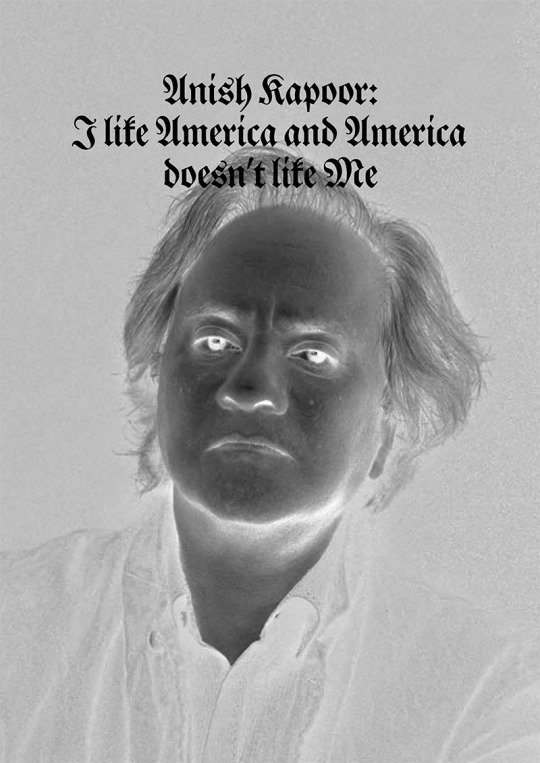

Thus, other more independent authors focus mostly on his views in the art itself. Such as the support for refugees or protest against the policy of Tramp, when Kapoor altered one of the posters created in the 1974 for the performance “I Like America and America Likes Me” of the artist Joseph Beuys. Kapoor placed his portrait on the poster and changed the title. In his version, it sounds like: “I Like America and America Doesn’t Like Me”. He says: "I call on fellow artists and citizens to disseminate their name and image using Joseph Beuys' seminal work of art as a focus for social change. Our silence makes us complicit with the politics of exclusion. We will not be silent" (ArtDaily, 2017).

Anish Kapoor, I like America and America doesn't like Me

The exhibition “My Red Homeland” in the The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow also caused a debate about its insert meaning. Because of the current political situation in Russia and strong associations between the red colour and history of the country, a lot of local visitors were looking for the some kind of the hidden message. However, Kapoor states that, “the works point in certain directions, but they’re not prescriptive in their meaning. I think that means that they allow for a possible openness of interpretation and that can be responsive to the time in which the work is shown. It’s not incidental that I’m showing My Red Homeland here in Russia. In one way it’s slightly naughty, and in another way, I quite like the idea of engaging with the questions” (Small, 2017).

Anish Kapoor, My Red Homeland

Nevertheless, even if for the artist the question of his cultural affiliation is open, in his artworks Kapoor emphasizes that the most important things are to be hidden in sight and that a work of art is not a finished form, but an ongoing process.

Above all these issues, in the case of Kapoor, there is still the effect of the social boundaries can be seen, as far as for the reviewers from Jewish community, the emphases of his Jewishness is a subconscious way to claim him authentic and draw the boundary between his art and the rest. At the same time, the definition of the essence of Jewish art no longer has priority over artists and works of art, as we also can see on the example of Anish Kapoor. Art should not be reduced to the biographies of its producers or be analyzed only with respect to the intended audience or limited religious community.

References:

Anish Kapoor recreates seminal artwork in anti-Trump protest. (2017). ArtDaily. Retrieved from: http://artdaily.com/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=93455#.Wed8DGi0OMo

Anish Kapoor. Artist. Jewish. Color Renegade. (2017). Jewcy. Retrieved from http://jewcy.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/jewish-artist-anish-kapoor

Barth, F. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture difference. London: Allen & Unwin (‘Introduction’).

Bourdieu, P. (1984) [1979]. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chong, P. (2011). Reading difference: How race and ethnicity function as tools for critical appraisal. Poetics 39 (1): 64-84.

Conversations with Artists, Selden Rodman, New York Devin-Adair. (1957). p. 93.; reprinted as 'Notes from a conversation with Selden Rodman, 1956', in Writings on Art: Mark Rothko (2006) ed. Miguel López-Remiro.

Gutmann, J. (1961). The "Second Commandment" and the Image in Judaism. Hebrew Union College Annual, 32, 161-174.

Hesli, V., Miller, A., Reisinger, W., & Morgan, K. (1994). Social Distance from Jews in Russia and Ukraine. Slavic Review, 53(3), 807-828.

Jeffries, S. (2017). Anish Kapoor on Wagner: 'He was antisemitic and I'm Jewish. Who cares?'. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/jun/08/anish-kapoor-on-wagner-he-was-antisemitic-and-im-jewish-who-cares.

Lamont, Michèle & Virág Molnár. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual

Orlov, A. (2008). First There Was the Word: Early Russian Texts on Modern Jewish Art. Oxford Art Journal, 31(3), 385-402.

Prize ceremony for Anish Kapoor cancelled because of Syrian suffering (2017). The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved from: https://www.thejc.com/news/israel/prize-ceremony-for-anish-kapoor-cancelled-because-of-syrian-suffering-1.437797.

Review of Sociology 28 (1): 167-195.

Silver, L., & Baskind, S. (2011). Looking Jewish: The State of Research on Modern Jewish Art. The Jewish Quarterly Review, 101(4), 631-652.

Small, R. (2017). Anish Kapoor Colors Russia Red - Interview Magazine. Interview Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/anish-kapoor-jewish-museum-and-tolerance-center [Accessed 18 Oct. 2017].

Tavory, I. (2009). Of yarmulkes and categories: Delegating boundaries and the phenomenology of interactional expectation. Theory and Society, 39(1), 49-68.

The Guardian. (2017). Anish Kapoor condemns 'abhorrent' refugee policies as he wins Genesis prize. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/feb/06/anish-kapoor-condemns-abhorrent-refugee-policies-as-he-wins-genesis-prize.

The John Tusa Interviews, Anish Kapoor. (2003). Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00ncbc1

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is South African culture? I give you: Die Antwoord

‘’Whatever Man’’

Check it,

I represent South African culture.

In this place you get a lot of different things:

Blacks,

Whites,

Coloured,

English,

Afrikaans,

Xhosa,

Zulu,

watookal.

I'm like all these different things,

all these different people,

fucked into one person.

Whatever man.

When the members of South African music group Die Antwoord speak these words, they present themselves as the embodiment of South African culture. In contemporary society, South African culture includes people from countless different ethnic backgrounds. But this has not always been the case.

It is probably sensible to say that South Africa knew a more peaceful time before colonialism. European countries, specifically the Netherlands, took the country of South Africa under their wing. Not necessarily in the positive sense, but with a rather forceful emphasis on imperialism. In doing this, masses of Dutch people immigrated to South Africa. They packed their bags with clothes, wealth, and feelings of white superiority. When the colonialists arrived in South Africa, these feelings were manifested into the act of simply conquering land that belonged to the country’s first inhabitants (Minty, 2006).

Clearly, white supremacy and racial segregation are issues that South Africa has dealt with for centuries. Segregation has been argued to support the development of the capitalist system in South Africa, thus perpetuating white economic ideologies that the colonialists brought with them (Dubow, 1989). It is this course of events that lead to the notion of apartheid. Apartheid may also refer to ‘’separate development’’ (Wolpe, 2006, p. 425). The oppressive government implemented apartheid quite literally. African communities were relocated to townships where the police could exercise constant control. (Wolpe, 2006). Gradually, black and white communities were separated altogether. A structure was built in which the white settlers gained full control over the African inhabitants. Ironically, the minority dominated the majority.

It appears that apartheid challenges the definition of South African culture. The separation of communities may be argued to have created two developmental paths, or rather two histories: that of white people and that of black people. Since colonialism, the history of black people is characterized by resisting white domination (Wakashe, 1986). The opposition between blacks and whites defines the structure of South African culture, and is of central importance to every South African citizen today. (Minty, 2006).

But what exactly is South African culture? Did South Africa only have its own distinctive culture before European interference? Is it a mixture of cultures, or is it authentic due to its historical path? The remnants of cultural elements that colonialists left behind, including racist ideologies, are omnipresent in South African culture. Not only this, but also the development of ‘’Afrikaans’’ language, similar to Dutch language, makes up a great deal of South African identity. An interesting subject to discuss is where this particular aspect of culture collides with art.

The Afrikaans music scene has exploded in the last decade. Noticeably, the majority of artists in this music scene are white (Marx & Milton, 2011). This raises complications in defining Afrikaans identities, especially because the Afrikaans music scene speaks to a wider (less whiter) audience in South Africa (Coetzer, 2009). Within the field of whiteness studies, Marx & Milton (2011) find that this challenges the normative stance of whiteness. Whiteness is argued to be the standard that white people use to measure other identities. (Perry, 2001). Or, as Heavner (2007, p. 65) puts it, white identity has been ‘’serving as a marker against which difference is drawn’’. In South Africa, this argument does not necessarily hold. Marx & Milton (2011, p. 723) comment that ‘’white people are acutely aware of their whiteness’’. They feel responsible for limiting their performance of whiteness. This condition of practicing whiteness unsettles culture: unwritten rules and codes are broken (Hall, 1997).

In a culture as unsettled as in South Africa, a reconfiguration of white identity is taking place. This is especially evident in the art world, and in this case: the music scene. The negotiation of Afrikaans identity, however, seems contradictory within this scene. Afrikaans commercial music invokes nostalgia and glorifies what it means to be Afrikaans. Alternative music opposes these characteristics, and denounces the apparent stability of Afrikaans identity. In addition, it expresses cynicism with the dominant position of Afrikaans identity (Marx & Milton, 2011).

Die Antwoord belongs to the latter category of alternative Afrikaans music. Die Antwoord is a white music group based in Cape Town, South Africa, and consists of three members: Yo-Landi Vi$$er, Ninja (Watkin Tudor Jones), and DJ Hi-Tek (Jeffries, 2017). They can be categorized into the genres of rap and hip-hop. Typically, these genres are associated with black artists. Black people are socially marked, because they deviate from whiteness, which is considered the norm (Brekhus, 1998). Due to this markedness, black artists find themselves confined within genres. White artists, as the ‘unmarked’, are not explicitly associated with specific genres or styles. But precisely because Die Antwoord performs within typical black genres, they call for a reconfiguration of white (Afrikaans) identity. They appear to do this in an almost parodical way.

Afrikaans bands like Die Antwoord challenge white identity by participating in ‘zef’-culture. They consider ‘zef’ to be the ultimate South African style. ‘Zef’ means being common, and was considered kitsch when the term originated in the 1980s (Marx & Milton, 2011). Nowadays, being ‘zef’ is ascribed with credibility, and according to author and singer Koos Kombuis, ‘’being truly zef takes guts’’ (cited in Fourie, 2010). Yo-Landi explains what it means to her in an interview: ‘’It’s just a style that came out of South Africa. Like, my haircut is zef. And Ninja’s tattoos are zef, and the fact that he wears his underpants, that’s zef’’ (YouTube, 2017). Poplak (cited in Marx & Milton, 2011), associates ‘zef’ with being white trash. White trash is not common in negotiating white identity, so by expressing themselves through this particular ‘zef’-culture, Die Antwoord’s whiteness becomes marked (Marx & Milton, 2011).

‘Zef’-culture is clearly visible in the way Yolandi Visser and Ninja strut their style. However, this ‘zef’ identity also presents itself in their music. By employing the encoding/decoding model, music can be read as a text in which artists negotiate their identity (Laubscher, 2005). ‘Zef’ identity is thus reflected in the music that Die Antwoord produces. One of their songs, ‘’Dis iz why I’m hot’’, accurately describes what they represent:

I'm hot because I'm ZEF, you ain't because you not

Furthermore, Ninja comments on the omnipresence of racial issues, even outside of the context of South Africa itself:

When you say South Africa the first things that come to mind

Is, yup, racism apartheid and crime

Fuck a racist, motherfuckers is stuck in '89

But the crime's still wildin' - word to my 9

In the lyrics above, Ninja discards ideas of racism and criticizes immediate race-related associations with South Africa. Being part of ‘zef’-culture, for Die Antwoord, signifies that South Africa should be treated as one distinctive culture. Their music may be regarded as a social commentary on the complexity of race inequalities. This is also apparent in earlier mentioned lyrics, where he proclaims:

I represent South African culture

This is a contradictory statement, because Die Antwoord is negotiating a white Afrikaans identity. How can they then represent an entire culture consisting of so many different identities? Perhaps, representing South African culture is embedded within the act of criticizing traditional white identity. By being so expressively ‘zef’, the members of Die Antwoord mark themselves and challenge the normativity of whiteness (Heavner, 2007).

This negotiation of Afrikaans identity has not always been perceived with positive connotations. Some black critics have argued that Die Antwoord has appropriated styles commonly identified with black music forms (Marx & Milton, 2011). This sparks a debate about the authenticity of ‘zef’-culture, and Die Antwoord’s music positioned within it. According to Peterson (2005), authenticity is a social construct, in which membership of an ethnic group is the only criterion to obtain the right to represent that group. In this vein, black critics have questioned the right of white artists to use rap music in expressing themselves (Marx & Milton, 2011). However, crossing this line may blur existing boundaries between ethnic groups. One may call it appropriation, but adopting other ethnicities’ cultural elements is one step towards forming one distinctive South African culture, which Die Antwoord seems to advocate for. After all, ‘’ethnic groups only persist as significant units if they imply marked difference in behaviour’’ (Barth, 1969, p. 15). Hence, by adopting each other’s behaviour, gaps between ethnic groups are reduced. Whether or not this process is a desirable one is up for discussion, because it does hold implications for the persistence of authentic ethnic cultural heritage.

Conclusively, how does Die Antwoord represent South African culture? They do not, necessarily. They do represent the construction of white Afrikaans identity and thereby challenge relationships between South African ethnicities. So what is South African culture? As to that, there is no definite answer… But Die Antwoord definitely is controversial.

Bibliography

Barth, Fredrik. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture difference. London: Allen & Unwin (‘Introduction’).

Brekhus, Wayne. (1998). A sociology of the unmarked. Sociological Theory 16 (1): 34-51.

Coetzer, D. (2009, August 29). Speaking in tongues: Afrikaans artists find mainstream success in South Africa. Billboard.

Dubow, S. (1989). Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Fourie, M. (2010). The dummies’ guide to zef. news24.com. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from

http://www.news24.com/Entertainment/SouthAfrica/The-Dummies-guide-to-Zef-20100216

Hall, S. (1997). The spectacle of the other. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural

representation and signifying practice (pp. 223-290). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Heavner, B.M. (2007). Liminality and normative whiteness: A critical reading of poor white trash. Ohio Communication Journal, 45, 65-80.

Jeffries, D. (2017). Die Antwoord [Blog post]. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://www.allmusic.com/artist/die-antwoord-mn0002454832/biography

Laubscher, L. (2005). Afrikaner identity and the music of Johannes Kerkorrel. South African Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 308-330.

Marx, H., & Milton, V. C. (2011). Bastardised whiteness: ‘zef’-culture, Die Antwoord and the reconfiguration of contemporary Afrikaans identities. Social Identities, 17(6), 723-745. doi:10.1080/13504630.2011.606671

Minty, Z. (2006). Post-apartheid Public Art in Cape Town: Symbolic Reparations and Public Space. Urban Studies, 43(2), 421-440. doi:10.1080/00420980500406728

Perry, P. (2001). White means never having to say you’re ethnic: White youth and the construction of “cultureless” identities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 30(1): 56-91.

Peterson, Richard. (2005). In search for authenticity. Journal of Management Studies 42(5): 1083-1098.

Wakashe, T. P. (1986). ''Pula'': An Example of Black Protest Theatre in South Africa. The Drama Review: TDR, 30(4), 36-47. doi:10.2307/1145780

Wolpe, H. (2006). Capitalism and cheap labour-power in South Africa: from segregation to apartheid. Economy & Society, 1(4), 425-456. doi:10.1080/03085147200000023

YouTube. (2017, September 17). Why Yolandi Visser is a queen in a 10 minute video [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ogw-FdnMuUY

‘’Whatever Man’’

Check it,

I represent South African culture.

In this place you get a lot of different things:

Blacks,

Whites,

Coloured,

English,

Afrikaans,

Xhosa,

Zulu,

watookal.

I'm like all these different things,

all these different people,

fucked into one person.

Whatever man.

When the members of South African music group Die Antwoord speak these words, they present themselves as the embodiment of South African culture. In contemporary society, South African culture includes people from countless different ethnic backgrounds. But this has not always been the case.

It is probably sensible to say that South Africa knew a more peaceful time before colonialism. European countries, specifically the Netherlands, took the country of South Africa under their wing. Not necessarily in the positive sense, but with a rather forceful emphasis on imperialism. In doing this, masses of Dutch people immigrated to South Africa. They packed their bags with clothes, wealth, and feelings of white superiority. When the colonialists arrived in South Africa, these feelings were manifested into the act of simply conquering land that belonged to the country’s first inhabitants (Minty, 2006).

Clearly, white supremacy and racial segregation are issues that South Africa has dealt with for centuries. Segregation has been argued to support the development of the capitalist system in South Africa, thus perpetuating white economic ideologies that the colonialists brought with them (Dubow, 1989). It is this course of events that lead to the notion of apartheid. Apartheid may also refer to ‘’separate development’’ (Wolpe, 2006, p. 425). The oppressive government implemented apartheid quite literally. African communities were relocated to townships where the police could exercise constant control. (Wolpe, 2006). Gradually, black and white communities were separated altogether. A structure was built in which the white settlers gained full control over the African inhabitants. Ironically, the minority dominated the majority.

It appears that apartheid challenges the definition of South African culture. The separation of communities may be argued to have created two developmental paths, or rather two histories: that of white people and that of black people. Since colonialism, the history of black people is characterized by resisting white domination (Wakashe, 1986). The opposition between blacks and whites defines the structure of South African culture, and is of central importance to every South African citizen today. (Minty, 2006).

But what exactly is South African culture? Did South Africa only have its own distinctive culture before European interference? Is it a mixture of cultures, or is it authentic due to its historical path? The remnants of cultural elements that colonialists left behind, including racist ideologies, are omnipresent in South African culture. Not only this, but also the development of ‘’Afrikaans’’ language, similar to Dutch language, makes up a great deal of South African identity. An interesting subject to discuss is where this particular aspect of culture collides with art.

The Afrikaans music scene has exploded in the last decade. Noticeably, the majority of artists in this music scene are white (Marx & Milton, 2011). This raises complications in defining Afrikaans identities, especially because the Afrikaans music scene speaks to a wider (less whiter) audience in South Africa (Coetzer, 2009). Within the field of whiteness studies, Marx & Milton (2011) find that this challenges the normative stance of whiteness. Whiteness is argued to be the standard that white people use to measure other identities. (Perry, 2001). Or, as Heavner (2007, p. 65) puts it, white identity has been ‘’serving as a marker against which difference is drawn’’. In South Africa, this argument does not necessarily hold. Marx & Milton (2011, p. 723) comment that ‘’white people are acutely aware of their whiteness’’. They feel responsible for limiting their performance of whiteness. This condition of practicing whiteness unsettles culture: unwritten rules and codes are broken (Hall, 1997).

In a culture as unsettled as in South Africa, a reconfiguration of white identity is taking place. This is especially evident in the art world, and in this case: the music scene. The negotiation of Afrikaans identity, however, seems contradictory within this scene. Afrikaans commercial music invokes nostalgia and glorifies what it means to be Afrikaans. Alternative music opposes these characteristics, and denounces the apparent stability of Afrikaans identity. In addition, it expresses cynicism with the dominant position of Afrikaans identity (Marx & Milton, 2011).

Die Antwoord belongs to the latter category of alternative Afrikaans music. Die Antwoord is a white music group based in Cape Town, South Africa, and consists of three members: Yo-Landi Vi$$er, Ninja (Watkin Tudor Jones), and DJ Hi-Tek (Jeffries, 2017). They can be categorized into the genres of rap and hip-hop. Typically, these genres are associated with black artists. Black people are socially marked, because they deviate from whiteness, which is considered the norm (Brekhus, 1998). Due to this markedness, black artists find themselves confined within genres. White artists, as the ‘unmarked’, are not explicitly associated with specific genres or styles. But precisely because Die Antwoord performs within typical black genres, they call for a reconfiguration of white (Afrikaans) identity. They appear to do this in an almost parodical way.

Yo-Landi Vi$$er and Ninja

Afrikaans bands like Die Antwoord challenge white identity by participating in ‘zef’-culture. They consider ‘zef’ to be the ultimate South African style. ‘Zef’ means being common, and was considered kitsch when the term originated in the 1980s (Marx & Milton, 2011). Nowadays, being ‘zef’ is ascribed with credibility, and according to author and singer Koos Kombuis, ‘’being truly zef takes guts’’ (cited in Fourie, 2010). Yo-Landi explains what it means to her in an interview: ‘’It’s just a style that came out of South Africa. Like, my haircut is zef. And Ninja’s tattoos are zef, and the fact that he wears his underpants, that’s zef’’ (YouTube, 2017). Poplak (cited in Marx & Milton, 2011), associates ‘zef’ with being white trash. White trash is not common in negotiating white identity, so by expressing themselves through this particular ‘zef’-culture, Die Antwoord’s whiteness becomes marked (Marx & Milton, 2011).

‘Zef’-culture is clearly visible in the way Yolandi Visser and Ninja strut their style. However, this ‘zef’ identity also presents itself in their music. By employing the encoding/decoding model, music can be read as a text in which artists negotiate their identity (Laubscher, 2005). ‘Zef’ identity is thus reflected in the music that Die Antwoord produces. One of their songs, ‘’Dis iz why I’m hot’’, accurately describes what they represent:

I'm hot because I'm ZEF, you ain't because you not

Furthermore, Ninja comments on the omnipresence of racial issues, even outside of the context of South Africa itself:

When you say South Africa the first things that come to mind

Is, yup, racism apartheid and crime

Fuck a racist, motherfuckers is stuck in '89

But the crime's still wildin' - word to my 9

In the lyrics above, Ninja discards ideas of racism and criticizes immediate race-related associations with South Africa. Being part of ‘zef’-culture, for Die Antwoord, signifies that South Africa should be treated as one distinctive culture. Their music may be regarded as a social commentary on the complexity of race inequalities. This is also apparent in earlier mentioned lyrics, where he proclaims:

I represent South African culture

This is a contradictory statement, because Die Antwoord is negotiating a white Afrikaans identity. How can they then represent an entire culture consisting of so many different identities? Perhaps, representing South African culture is embedded within the act of criticizing traditional white identity. By being so expressively ‘zef’, the members of Die Antwoord mark themselves and challenge the normativity of whiteness (Heavner, 2007).

This negotiation of Afrikaans identity has not always been perceived with positive connotations. Some black critics have argued that Die Antwoord has appropriated styles commonly identified with black music forms (Marx & Milton, 2011). This sparks a debate about the authenticity of ‘zef’-culture, and Die Antwoord’s music positioned within it. According to Peterson (2005), authenticity is a social construct, in which membership of an ethnic group is the only criterion to obtain the right to represent that group. In this vein, black critics have questioned the right of white artists to use rap music in expressing themselves (Marx & Milton, 2011). However, crossing this line may blur existing boundaries between ethnic groups. One may call it appropriation, but adopting other ethnicities’ cultural elements is one step towards forming one distinctive South African culture, which Die Antwoord seems to advocate for. After all, ‘’ethnic groups only persist as significant units if they imply marked difference in behaviour’’ (Barth, 1969, p. 15). Hence, by adopting each other’s behaviour, gaps between ethnic groups are reduced. Whether or not this process is a desirable one is up for discussion, because it does hold implications for the persistence of authentic ethnic cultural heritage.

Conclusively, how does Die Antwoord represent South African culture? They do not, necessarily. They do represent the construction of white Afrikaans identity and thereby challenge relationships between South African ethnicities. So what is South African culture? As to that, there is no definite answer… But Die Antwoord definitely is controversial.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Voluntourism: Valuable Volunteering or Unconscious Colonialism?

In recent years, there has been a surge of an alternative form of tourism in which tourists, who are often white, Western and from developed countries, travel to developing countries and spend part of their vacation volunteering in poverty stricken communities. Most of us have probably encountered one of these young, starry-eyed travellers; enthusiastically recalling the humbling, eye opening volunteer tourism (or voluntourism, for short) experience they had during their gap year. They may reminisce about the bright smiling faces of the children they cared for in a Kenyan orphanage, or the young students in a run-down Cambodian elementary school, all the while expressing their deepest gratitude for having had the chance to really “make a difference.”

Encountering these travellers and their stories has become increasingly common, with voluntourism being widely considered as an excellent way of participating in sustainable tourism that mutually benefits both tourists and their host communities (Pastran, 2014). Discussions on, and recollections of, voluntourism often highlight a long list of positive implications, describing the selflessness of the volunteers, the cross-cultural exchange and education, and the lasting effects on the volunteers who return to their home countries with a new, life-changing perspective on the world (Becklage, 2013).

However, while there may be positive implications of, and altruistic intentions behind, voluntourism, there is also a tendency to overlook certain negative, racial, implications of the act. Often lurking behind the seemingly well-intentioned discourse on voluntourism are neocolonial assumptions that very much reproduce structures of racial/ethnical power, privilege and oppression (Pastran, 2014). One of these underlying assumptions derives from the lack of education provided to Western volunteers about the local culture, history and general way of life of their host community, resulting in a one-dimensional, simplified perspective that highlights the neediness, poverty and apparent incapability of the “underdeveloped” locals (Mohamud, 2013). Rather than acknowledging the complexity and socio-historical contexts of these communities, or attempting to find cross-cultural similarities between the developing and the developed world, many voluntourists (and the organizations they make arrangements through) choose to instead emphasize the ‘otherness’ of their host communities and ethnic residents, defining them simply by their needs and ‘uncivilized’ nature (Guttentag, 2009). Such simplified classification is exemplified in the documentary ‘The Voluntourist’ (Sanguinetti, 2015), in which a local, employed at a Cambodian school accepting Western voluntourists, expresses his discomfort at the frequent generalization of the character of Cambodia (22:20 – 23:35). Referring to the sole focus on the neediness, or otherness, of the country, he exclaims “Really?! Is this how you view Cambodia?” suggesting the existence of a multi-dimensional perspective, or even reality, of Cambodia that is being largely ignored.

Link to 'The Voluntourist': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E16iOaAP4SQ&list=PLp1c-iNf31IYOI4OJcRhjKW-P0o7joNzP&index=3

Moreover, the poverty, or otherness, of host communities is often romanticized by privileged volunteers, and associated with emotional and social wealth, or a ‘poor-but-happy’ attitude to life. (Simpson, 2004) That is to say, voluntourists have the tendency to assume that locals in developing countries feel a certain sense of freedom, happiness and gratitude not experienced by those in first world, Western countries, who are too corrupted and restrained by economic wealth and material possessions to pursue the emotional/social wealth that is apparently so prevalent in third world communities. This is highly problematic, as not only does it allow for the justification of world wide material inequality, it is also quite reminiscent of the colonialist concept of the ‘noble savage’. This literary character/ideal has existed since the 16th century, representing the primitive ‘wild human’, uncorrupted by civilization and thereby innately ‘good’ (or in the modern case, more grateful and content with life) (Ellingson, 2001).

By adopting such simplified perspectives, volunteers effectively engage in the cognitive classification of these residents and their communities (Brubaker et al, 2004), emphasizing the boundaries between “them” and “us”, and further perpetuating common, colonialist stereotypes of the needy, underdeveloped, yet noble (i.e. content and grateful) ethnic groups who are unable to move forward without the help of the civilized, Western savior.

This leads us to our next underlying assumption of voluntourism, namely the above- stated belief that poverty-stricken countries/communities require the help of Westerners to induce development. This belief is referred to as ‘the white savior complex’ and stems from white, Western fantasies of ‘saving’ minority groups in developing countries (Cole, 2012). It is an idea that allows voluntourists to travel to these countries with the neocolonial assumption that even unqualified and inexperienced Westerners, with little to no understanding of the local resources and contexts, can ‘make a difference’ simply by being there (Saguinetti, 2015). Moreover, it indicates the assumption that unknowledgeable Westerners are still somehow more in a position to teach the community how best to partake in their own development than local residents, implying their perceived superiority of white, Western culture, and further enforcing the dichotomy of the superior, benevolent giver and the inferior, helpless ‘other’ (Sin, 2009). Clearly, the agency, knowledge, and capabilities of local residents in developing countries is largely ignored in these situations, a problem which Teju Cole (2012) thoroughly discusses and criticizes in his article ‘The White Savior Industrial Complex’. He examines the American outrage regarding humanitarian crises in Uganda in 2012 (which came to Western consciousness through the viral Kony 2012 video), as well as the Western desire to save the country. Responding to these concerned calls for Western heroism, Cole (2012) argues that a well-intentioned Westerner can ‘save’, a place like Uganda by first adopting a sense of respect for the agency of Ugandan people in their own lives, and through the abandonment of the ‘we have to save them because they can’t save themselves’ mentality. While most voluntourists are not engaged with humanitarian crises such as this one, the argument is still applicable to Westerners wanting to ‘save’ smaller, developing communities in Thailand, Cambodia, South Africa and other typical voluntourist destinations.

While wanting to ‘save’ developing communities is a common, well intentioned yet misguided (even ignorant) motivation to engage in voluntourism today, there are also other motivations amongst voluntourists that further imply the negative implications of this industry. First, as exemplified by Ossob Mohamud (2013) in her article ‘Beware the voluntourists doing good’, there is often a highly self-congratulatory atmosphere amongst these volunteers, who partially and perhaps unconsciously embark on these trips to inflate their own egos. Considering this common attitude, as well as the sole focus on the volunteer’s search for an authentic, self-fulfilling experience amongst many advertisements within the voluntourist industry, Mohamud questions whether these types of trips are designed more for the fulfillment of the volunteer, rather than reduction of global poverty. Often, there appears to be more of an emphasis on the volunteer feeling good, feeling as if they’ve made a difference, rather than on actually making a difference. Callanan and Thomas (2005) refer to this phenomenon as ‘shallow volunteer tourism’, where volunteers are more concerned about career achievement and self-development/fulfillment than about the well being of the local community. Sin (2009) confirms the commonality of this rather selfish motivation, claiming that interviews in his research on voluntourism reveal that many volunteers’ motivations revolve around the ‘self’, their own desires and expectations, rather than around the host community.

Another questionable, common motivation behind these trips lays with the search for authenticity, for an authentic ‘uncivilized’ experience with the cultural other. John Urry (1990) refers to this as ‘the tourist gaze’, i.e. a set of expectations, often based on stereotypical racial and cultural stereotypes, adopted by Western tourists and placed on local populations and communities. Locals are often forced to respond to these expectations and reflect back, or act according to, this Western gaze in order to benefit financially, and to please tourists who have spent money to engage with these “authentic” experiences. This process is very harmful, as it reduces important local cultural expressions and norms to little more than commodities. Furthermore, the tourist gaze is often rooted in neocolonial myths, e.g. ‘the myth of the uncivilized’ (Echtner & Prasad, 2004). Influenced by a nostalgic version of the era of colonial exploration, many modern day tourists (and voluntourists) idealize destinations containing “primitive, untamed nature and natives” (Echtner & Prasad, 2004, p. 675), wishing to participate in the discovery and exploration of these wild, uncivilized frontiers, much like the ‘great’ (white) explorers before them.

Many voluntourists were found to be adopting a sort of tourist gaze in, for example, Chen and Chen’s (2009) study ‘The Motivations and Expectations of International Volunteer Tourists’. They examine the motivations of Western voluntourists for volunteering in an underdeveloped village in Shaanxi, China. Interviews were conducted with the participants of the project, and amongst the most frequently mentioned motivations for volunteering was the desire for an authentic experience. Many respondents wished to immerse themselves in the Chinese culture, and to interact with the cultural other engaging in culturally authentic activities (Peterson, 2005) They expressed wanting to see “the real [Chinese] story” and to “get a close look at how people lived day by day in the village” (p. 439).

While the desire to immerse oneself in authentic cultural activities may seem admirable, a critical view on this common search for authenticity should be adopted, as not only does it often supersede what should be the core motivation and intention of volunteering (i.e. helping the community), but also reinforces stereotypes of the cultural other, potentially placing pressure on local communities to act according to these stereotypes. Furthermore, this search may result in people engaging in these ‘authentic’ experiences, simply to be able to claim a bit of authenticity for themselves, to construct and present themselves as an authentic, worldly, culturally aware person (Peterson, 2005). Voluntourists may very well be (un)consciously choosing this form of tourism to add something to the identity they perform, to develop (or at least perform a self that has developed) an authentic, deep understanding of the local conditions of developing communities (Sin, 2009). This, of course, is not, or should not be, the purpose of volunteering, and greatly differs from the supposed altruistic intentions that most voluntourists claim to have.

In conclusion, though it has a few positive aspects, volunteer tourism is a problematic industry, which contributes to the continuation of neocolonial power structures. However, it is possible to break from these structures if voluntourist organizations and travellers are willing to challenge and examine the discourses, history and assumptions behind the practice with a critical eye. Adopting the perspective of the host communities is essential in achieving this break from development that only furthers neocolonial relationships. If well-intentioned Western volunteers begin to engage in this analysis, to consider root structural and institutional causes of global inequality, and to understand their own role in this issues, perhaps a new, more effective and less self-focused form of development can emerge. Simply put, volunteering in Africa may seem like an impactful, sophisticated thing to do, but before running off to that orphanage in Kenya, perhaps one should take the time to ask themselves to what extent they really want to make a difference.

Bibliography

Blackledge, S. (2013). In defence of ‘voluntourists’. Retrieved October 11, 2017 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/25/in-defence-of-voluntourism1

Brubaker, R., Loveman, M., & Stamatov, P. (2004). Ethnicity and cognition. Theory and Society, 33(1), 31-64.

Callanan, M., & Thomas, S. (2005).Volunteer tourism. Niche tourism: Contemporary issues, trends, and cases. Wallington, UK: Butterworth- Heinemann.

Chen, L. & Chen, J. S. (2011). The motivations and expectations of international volunteer tourists: A case study of “Chinese Village Traditions”. Tourism Management, 32(2), 435 – 422

Cole, T. The White-Savior Industrial Complex. Retrieved October 12, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

Echtner, C. M., & Prasad, P. (2004). The context of third world tourism marketing. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 469-471

Ellingson, T. (2001). The myth of the noble savage. Berkely, CA: University of California Press

Guttentag, D. A. (2009). The possible negative impacts of volunteer tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11 (6), 537 – 551

Mohamud, O. (2013). Beware the voluntourists intent on doing good. Retrieved October 10th, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/13/beware-voluntourists-doing-good

Pastran, S. H. (2014) Volunteer tourism: a postcolonial approach. University of Saskatchewan Undergraduate Research Journal, 1(1), 45 – 57.

Peterson, R. A. (2005). In search of authenticity. Journal of Management Studies, 42 (5), 1083 - 1098

Sanguinetti, C. (2015).Documentary ‘The Voluntourist’: Is Voluntourism doing more harm than good? Retrieved October 15, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E16iOaAP4SQ&list=PLp1c-iNf31IYOI4OJcRhjKW-P0o7joNzP&index=3

Sin, H. L. (2009). Volunteer tourism – “involve me and I will learn?” Annals of Tourism Research, 36 (3), 480 - 501

Simpson, K. (2004). ‘Doing development’: the gap year, volunteer-tourists and a popular practice of development. Journal of International Development, 16(5), 681 – 692.

Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: leisure and travel in contemporary societies. London: Sage.

0 notes

Text

#OscarsSoWhite #WhoisToBlame

A refreshing inside on the continuous issue of minority representation within the academy awards and beyond

What the... Oscar is wrong with the academy awards? From Leonardo DiCaprio who forever seemed to remain Oscarless, to woman hastagging Me-too as result of sexual intimidation to the ongoing debate on the lack of ethnic minority nominations. The #OscarSowhite first appeared in 2015 when, as a reaction to all white nominations in the top Oscar Award categories, one citizen turned to twitter, tweeting:

The following year when the list of nominees portrayed a similar lack of minorities nominated for an Oscar, several actors and directors decided to boycott the annual academy awards (Cox, 2016). This year the awards did however, after a quick “envelope snafu” (Gray, 2017, p. 1), have the coming-of-age drama about a gay black man, Moonlight, win the Oscar for Best picture. Still the question remains whether this shattered a glass ceiling for ethnic minority directors, actors and films (Gray, 2017)

In the heat of this debate, On the one hand, the highly feasible ‘academy’ and its “colour-blind” (Rodriguez, 2006, p. 645), mostly white organizational structure is often addressed to as the Evil-doer. However, on the other hand looking at what the Academy awards are a representation of: the film industry, one may argue that the industries occupational careers, predominantly occupied by white man, and the markets “whitewashing” (Lowrey, 2016, p.1), is what leads to disadvantages in opportunities for racial/ethnic minorities. This post revives the ongoing trend of racial and ethnic representation in the film industry & academy awards commenting on the effects of colour-blindness within the organization of the Academy, the industries “social & symbolic boundaries” (Lamont, Molnar, 2002, p. 2 & 3) as well as the whitewashing of film in general. Not to mention the role of the critical/ biased audience in the issue of diversity. In order to get an inside in #whosis/aretoblame for the #Oscarsowhite and finally propose the possible first steps into solving the problem.

In the mist of the 2016th Academy award show La times published an article on the Unmasking of the Oscars arguing that there is an overwhelmingly unequal proportion of white male members in relation to those from a minority (Horn, Sperling, & Smith, 2012). Since 2012 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is mostly white (94 percent) and predominantly male (77 percent) (Horn, Sperling, & Smith, 2012). At that time, black members only accounted for just 3 percent of the group (Williams, Rosen, & Dvalidze, 2015). From an abstract liberalist perspective this lack of diversity, grounded in the Organizational structure (membership list), would have no effect on those who are nominated for opportunity has no colour (Rodriguez, 2006). Besides this, from a quote by Frank Pierson it appears that ethnic and racial matters within the academy are to a certain extent naturalized as he argues “We represent the professional filmmakers, and if that doesn't reflect the general population, so be it," (as cited in Horn, Sperling, & Smith, 2012) withholding any argument incorporating racial or ethnic differences (Rodriguez, 2006). Rodriguez (2016) describes how the above-mentioned sayings are part of a colour-blind ideology emphasizing a perceived equality between racial and ethnic groups despite unequal social locations and varying histories. By claiming that success knows no culture the white dominated academy ‘marks’ themselves as “cultureless” (Perry, 2001, p. 57). I purposely say mark because even unintentionally culturelessness can become a mean to white racial superiority (Perry, 2001)

A solution making sure Academy members avoid marking themselves as cultureless would be easy; simply invite more ethnic minority actors, directors, filmmakers etc. into their voting systems. Unfortunately, this is, as the Oscars uphold a prestige position within the movie industry, not so easy (Williams, Rosen, & Dvalidze, 2015). From the official Oscar website, it appears that becoming a member you must either be sponsored by two current academy members from within their own branch, or be nominated for an Oscar, which automatically puts them up for membership consideration (“academy membership”, 2017). These requirements form both a symbolic boundary; ethnic minority actors, directors etc. who feel unwelcome within the voting sphere of the Academy, as well as an objectified boundary; manifested in their unequal access to and unequal distribution of roles within the voting academy (Lamont, Molnar, 2002) It seems that as long as the current academy voters do not vote for more diversity these boundaries remain persistent. yet nonetheless, an analysis by the Economist (2016) suggests that voter prejudice is not the sole reason for social boundaries. As minority actors have secured only 15 % of the top roles the Academy’s choices remain limited. (“How racially skewed are the Oscars?”, 2016)

“If the industry as a whole is not doing a great job in opening up its ranks, it's very hard for us to diversify our membership." – writer-director, Phil Alden Robinson (as cited in Horn, Sperling, & Smith, 2012)

From the quote by Robinson it appears that social and symbolic boundaries are also visible in the film industry at large (Lamont, Molnar, 2002). From a historical context it’s found that when post war America had tried to assimilate native Americans into American culture but failed to offer an equal position, the upcoming movie industry knew a similar process failing to include the society at large (Magnien, 1973). From history, onwards this white ideal has led to today’s whitewashing of the movie industry (“BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”, 2017). Whitewashing is the practice of erasing people of color commonly with a white actor replacing a minority actor, or the other way around (Lowrey, 2016). Those in favour of non-white actors and actresses playing Asian or African kings and pirates, argue that the industry “simply choses the best” (Lowrey, 2016, p. 4) regardless of their ethnicity. Besides that, financial uncertainty causes director and producer to choose star power over risking to lose their audience to unknown minorities (Lowrey, 2016). These are all excuses according to Dr. Nancy Yueng who, in her book Reel inequality, comments on the lasting problem of whitewashing in the movie industry. In an interview with the BBC commenting on the recent movie cancelling of actor Ed Skrein after receiving criticism for being cast for an originally Asian role, he asks Yueng: haven’t we not passed the white washing? (“BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”, 2017) No, Yueng responds. saying that “Hollywood isn’t just there yet” (as cited in “BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”, 2017) due to their risk adverse behaviour (“BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”, 2017). An example of this can be found in how, casting calls often call for “Caucasian or any other ethnicity” (Lowrey, 2016, p.4), marking any ‘other ethnicity’ as the odd ones out, is simultaneously preferring the unmarked category of the ‘Caucasian’ (Brekhus, 1998). As a result of marking ethnic minorities are often typecast in particular roles. For example, black actors who are type casted into ghetto roles, characterized by an alternative speech (Yueng, 2010). These type castings again limit the reach of ethnic or racial minority cultural practioners, but why?

Although only being small part in the production process is the audience demands, it is worth mentioning that looking at the cognitive behaviour of the audience, it becomes clear that a reason for the industry her whitewashing and typecasting can be found in the fact that even “America’s minority audiences watch the movies that ignore them” (Cox, 2016, p.1). The audience, critical demand for a more diversified industry is in immediate contrast to what we buy our tickets for (Cox, 2016). When looking ate Griswold’s “Cultural diamond” (“Diagrams of Theory: Griswold's Cultural Diamond”, n.d, p.1) it seems that consumer demands influence cultural producers but cultural producers also influence consumer demands creating a virtuous circle (see figure 1.1). So as long as America needs the motion picture business, and the motion picture business needs the United States audience, ethnic minorities are stuck in the typecasting roles that have brought the audience commercial success and the audience viewing pleasure (Magnien, 1973). In order to break this circle solutions must be found both from within as well as from the outside.

Luckily, today, audience demands are influenced by changing demographics, where people are growing up in more diverse environments and want to see people that represent themselves and where they come from. (“BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”, 2017). This is in line with what McCarthy (2016) describes as searching for the real authentic experience. The industries reaction to this upcoming trend would in contrast to the whitewashing of film, cast more people of color for roles written for them in order to achieve the ‘real’ dimension of the film and generate the authentic experience. As the ongoing debate from the outside the industry has already revised conventional patterns of markedness, by bringing the lack of ethnic minority representation within the film industry to the foreground (Brekhus, 1998). Brekhus (1998) argues that from within, marking everything, filling in all the shades of social continua, there can no longer be a distinction made between cultural practioners from different ethnic backgrounds. This can only be achieved however through the further ornamentation not only of the unmarked centre but of the interior segments of the poles that fall below a visible threshold of markedness (Berkhus, 1998). no longer distinguishing between ‘causation’ and ‘other ethnicities’ on their calling sheet will only affect ethnic minority inclusion once the choice is no longer effected white predjudice. As far as for the academy, as they are eventually choosing the best and the “professional” (as cited in Horn, Sperling, & Smith, 2012) in doing so it is however important to not ignore but incorporate the unequal positions of actors, directors and filmmakers within the industry instead.

All in all, answering the question of who is to blame for the Oscars being so white it is difficult to point fingers into one direction. Although we may to some extent speak of increasing cultural awareness within the field, the vicious circle which entails how the academy’s colour-blindness might be a reflection of the industry’s easily replacing of an actor with color for a white actor in order to be certain of their market success, is still persistent as the debate continuous to exists. The question remains whether the future will ever know the hashtag of #Oscarssoinclusive. And Even when, in the search of authentic as well as raising cultural awareness, marking everything, will lead to a more diversified movie industry and more ethnic minority representational in the nominations, we must quickly move onto the next issue because hey, what would the Oscars be without a little scandal?

By Bente Lutteke

Bibliography

Academy Membership. (2017, October 13). Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.oscars.org/about/join-academy

“BBC Interviews Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen on Whitewashing”. (2017, August 29). Retrieved October 30, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EIp9a0LkbE4

Brekhus, Wayne. 1998. A sociology of the unmarked. Sociological Theory 16 (1): 34-51.

Cox, D. (2016, February 26). What #OscarsSoWhite got right – and wrong. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/feb/25/oscarssowhite-right-and-wrong-academy-awards-audience

Diagrams of Theory: Griswold's Cultural Diamond. (n.d.). Retrieved October 31, 2017, from https://www.dustinstoltz.com/blog/2016/12/30/diagrams-of-theory-griswolds-cultural-diamond

Gray, T. (2017, October 26). Oscars: Why Wrong-Envelope Snafu Sets the Tone for the New No-Rules, No-Logic Race. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://variety.com/2017/film/news/2018-oscars-wrong-envelope-snafu-1202598359/

Hancock, B.H. 2008. “Put a little color on that!” Sociological Perspectives 51 (4): 783-802.

Horn, J., Sperling, N., & Smith, D. (2012, February 19). Unmasking Oscar: Academy voters are overwhelmingly white and male. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-unmasking-oscar-academy-project-20120219-story.html

How racially skewed are the Oscars? (2016, January 21). Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2016/01/film-and-race

Lamont, Michèle & Virág Molnár. 2002. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 167-195

Lowrey, W. (2016). People Painted Over: Whitewashing of Minority Actors in Recent Film. Lake Worth, FL: Palm Beach State College. Web, 11.

MacCarthy, M. (2016). Touring ‘Real Life’?: Authenticity and Village-based Tourism in the

Trobriand Islands of Papua New Guinea. In ALEXEYEFF K. & TAYLOR J. (Eds.), Touring

Pacific Cultures (pp. 333-358). Australia: ANU press, pp. 335

Magnien, N. (1973). An Actor’s Outrage, or a Generation’s Wake-up Call? Native American Activists’ Declaration at the 45th Academy Awards Ceremony. KANATA, 40, 118.

Perry, P. (2001). White means never having to say you’re ethnic: White youth and the construction of “cultureless” identities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 30 (1): 56 – 91.

Rodriquez, J. (2006). Color-Blind Ideology and the Cultural Appropriation of Hip-Hop. Journal Of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(6), 645-668

Williams, B., Rosen, C., & Dvalidze, I. (2015, February 20). Why It Should Bother Everyone That The Oscars Are So White. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/20/oscars-diversity-problem_n_6709334.html

Yueng, N. W. (2010, April 9). Playing "Ghetto": Black Actors, Stereotypes, and Authenticity « Page 1 « Black Los Angeles. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from https://fromthesquare.org/blackla/?p=17&cpage=1

0 notes

Text

Who are we?

Since October the Netherlands have a new government. In the past few weeks new plans of the government already found its way to the media. Among these were also policies regarding the arts and culture sector. For schools it will be mandatory to bring their pupils to the parliament and the Rijksmuseum, the national museum of art and also partly of history. Subsequently, the schools are obliged to learn the pupils the Dutch national anthem, het Wilhelmus, not only the lyrics, but also the context behind the song. The government said to introduce these plans as they will secure the national identity in times of insecurity and globalization (Thole, 2017). This plan fits within the discussion within the Netherlands about what our identity is, if there even is one. The Dutch queen Máxima stated back in 2007 that the Dutchman does not exist. If there is no coherent image of what the Dutch national identity is in the country itself how can the plans introduced by the government secure the identity. Is the plan not a way of creating or forcing an identity on the Dutch people (children)?

In this blogpost I try to give an answer to the question if identity can be forced on people and if so, what is the role of arts and culture in this identity formation. This question will be answered by discussing how identity and culture are constituted in the first place by the text of Nagel. Second, the role of memory in the constitution of identity will be described by the theory of Assman and DeNora. I chose to focus on memory for it Is mentioned in many text that is used for both the construction of ethnic identity and national identity. Third, the role of arts and culture in the process of identity making will be documented.

Constructing Ethnic Identity and Culture

According to Nagel (1994) ethnic identity is something that is constructed through ascription by others and the view one has of oneself; it answers who we are. The extent to which individuals or groups can construct ethnicity themselves is narrow as ethnic categories are imposed by others (Nagel, 1994).

Ethnicity consists of culture and history, these are also used to construct ethnic meaning (Nagel, 1994). Nagel (1994) states that culture is constructed by collecting and selecting items of the past and the present. As ethnic identity answers who we are, culture answers what we are. Culture is mainly constructed through the reconstruction of history and the construction of a new culture (Nagel, 1994). The cultural construction techniques aides, among other things, the construction of community as “they act to define the boundaries of the ethnic identity, establish membership criteria, generate a shared symbolic vocabulary, and define a common purpose” (Nagel, 1994). The reconstruction of history is according to Hobsbawn seen as the invention of tradition (Nagel, 1994). This invention of tradition can be used for different reasons defined by Hobbsbawn (Nagel, 1994): “a) to establish or symbolize social cohesion or group membership, b) to establish or legitimize institutions, status and authority relations, or c) to socialize or inculcate beliefs, values or behaviors”. One could argue the invention of tradition has to do with the construction of community.

Cultural construction, as documented in the text of Nagel (1994), is especially important for poly-ethnic groups for they are composed of subgroups with different histories and traditions which once were, in some cases, in conflict with each other.

Memory

Memory is a way to construct national identity. Nations use collective memory to let people feel part of the same nation.

Assman (2006) makes distinctions between individual, collective/social, cultural and political memory.

According to Assman (2006) memories help constitute our individual and societal identity. As for the construction of ethnic identity, especially political and cultural memory are important (Assman, 2006). Political and cultural memory are mediated, they rely on material representations and symbols; on museums, monuments and libraries and on education. These types of memories are (meant as) transgenerational memories (Assman, 2006): the memories pass from generation to generation. When memories are transformed to cultural and political memories, these memories become institutionalized top-down memories. The transformation of these memories, however, sometimes cause criticism in society (Assman, 2006).

The political memories can be (ab)used in the construction of collective identities by institutions, states and nations (Assman, 2006). Institutions, states and nations do not ‘have’ memories, they ‘make’ memories. They make memories together with symbols, texts, images, rituals, monuments, etcetera. With these memories such institutions construct an identity (Assman, 2006). The memories used for the identity are strictly selected. They reside in material media, symbols and practices which have to be engrafted in the hearts and minds of individuals (Assman, 2006). These memories have to be engrafted in the hearts and minds of people to be able to be part of the collective identity. Political memories are relatively homogenous as they are reconstructed by historians and represented by public education, national celebrations, narratives, images and film which will enhance emotions of empathy and identification (Assman, 2006). “History turns into memory when it is transformed into forms of shared knowledge and collective identification and participation” (Assman, 2006; p. 216). In this case history is turned in an emotionally involved ‘our history’ which will be absorbed in a collective identity.

National memory is a form of political memory (Assman, 2006). Only the memories referring to the national history that strengthen the positive, heroic self-image are selected. This is in coherence with the text of Nagel (1994) that people have a nostalgia for the past and therefore go back to or create a golden age. In hegemonic nations victories are celebrated, defeats are remembered as consolidation of their power by a sense of imminent danger (Assman, 2006). Minority nations remember their defeats with much pathos, they founded their identity on their suppression by hegemonic states and the defeats represent the counteractions of the minorities against the hegemonic states (Assman, 2006). In either way, victories and defeats are remembered as mythical, heroic events. The seventeenth century is considered the golden age of the Netherlands, the Dutch were the biggest traders and ruled over sea, the Netherlands had a lot of wealth; streets are named after and statues are mad of the heroes of this time such as Michiel de Ruyter. The seventeenth century is also the era of the Dutch masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer, works of these painters are presented in the Rijksmuseum. In this way the Dutch history is glorified.

The memories that are excluded from the national identity are historical events of shame and guilt as this part of national history endangers the positive, heroic self-image (Assman, 2006). The Dutch involvement of slavery is an example for the Netherlands; the Dutch people are not proud of this which results in very little focus on this phase in Dutch history in for example education.

There is, however, a shift going on from the trend of ‘forgetting’ to sharing. There now seems to be a new form of collective memory in which ethnic responsibility is among other things a new concept. Shameful historic moments and traumatic historic moments are now admitted and talked about instead of ‘forgotten’ (Assman, 2006).

An example of an art form that lets people remember or relive certain memories is according to DeNora (2000) music. DeNora (2000) talks about the role of music in the constitution of the self. She acknowledges that music can be used as a tool to remember certain events. If there is a connotation with particular music and a particular event constructed by oneself or by others, this music serves as an aid to remember that event, aide-mémoíre (DeNora, 2000). And as memories help construct a collective identity and as music helps to remember memories; music is an example of an art form that helps constitute identity. This also applicable on het Wilhelmus, I believe, the national anthem is mostly heard at the Dutch national festive, Koningsdag, and with international sport games. Being Dutch is central in both examples. So whenever Dutchmen hear this anthem they remember these patriotic events. In this way het Wilhelmus contributes to the Dutch national identity.

Conclusion

If we take the theories of Nagel (1994), Assman (2006) and DeNora (2000) in consideration, we can come to the following conclusion. Ethnic identity is constructed through self-ascription and ascription. Ethnic identity consists of culture and reconstruction of history. Memories are important in the construction of ethnic identity as well; especially political and cultural memories. These memories are also constructed.

Since ethnicity and memories are constructed by others as well and since there is little space for ethnicities to create their own identity, one could argue that ethnic identity can be forced upon people.

As the memories are reduced into symbols, statues, libraries, museum etcetera and as music is a tool to remember events, one can conclude that arts and culture play a significant role in the construction of ethnic identity.

Thus one could argue that the Dutch government can construct or ‘secure’ the Dutch identity with memories reduced in art that enhance the heroic image of the Netherlands. The Wilhelmus refers to Willem van Oranje, the ancestor of the Dutch monorachy; learning and learning about the lyrics will thus enhance a positive self-image. In the Rijksmuseum the Dutch masters of the seventeenth century are exhibited, this clearly enhances the mythic self-image. However, in 2020 there will be an exposition about slavery in the Rijksmuseum (Zeil & Beukers, 2017); this will not contribute to the positive self-image of the Netherlands. The remarkable choice of the government to let pupils visit the museum, could be explained with the shift to ‘sharing’ instead of ‘forgetting’ as explained by Assman.

Only time will tell if the plans have the desired effect. Only time will tell if queen Máxima has to revise her statement or that she was right all along.

Literature

DeNora, T. (2000). Music in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (46-74)

Assman, A. (2006). The Oxford handbook of contextual political analysis (pp. 210-226). New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Nagel, Joane. 1994. Constructing ethnicity: Creating and recreating ethnic identity and culture. Social Problems 41: 152-176.

Thole, H. (October 10th 2017). Een filosofe vindt het helemaal geen slecht idee dat schoolkinderen het Wilhelmus moeten leren. Business Insider Nederland. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.nl/wilhelmus-leren-basisschool-regeerakkoord-kabinet-rutte/

Zeil, W. & Beukers, G. (February 10th 2017). Nieuwe directeur Rijksmuseum breekt met verleden en maakt tentoonstelling over slavernij. De Volkskrant. Retrieved from: https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/nieuwe-directeur-rijksmuseum-breekt-met-verleden-en-maakt-tentoonstelling-over-slavernij~a4460392/

Cato Overbeek (453735)

0 notes

Text

Tommy Hilfiger: the idealised simulacrum of the American identity

Brianne Wind, 434761

Let’s play a game… Guess the fashion designer. The hints? Red, blue and white. Supermodel Gigi Hadid. Classic American cool style.

We have a winner!

Let me invite you into the world of Tommy Hilfiger - the American fashion brand shaping the desires of the youth. How you might wonder? As Emma Moore from the London Times once stated: “It would be hard to find a designer more fiercely American in inspiration and outlook.” (2001, p. 46). Simply said, Tommy Hilfiger is America and America is Tommy Hilfiger. Ultimately, Tommy Hilfiger enables you to live the American dream life through fashion.

The power of clothing to enhance one’s sense of identification has long been recognized (Crane, 2012). Identification can occur based on a diverse set of cultural traits, but, relatively little is known about fashion in relation to national identity. In this blog I will argue that fashion can: strongly be inspired by a nation; produce nationwide symbolic values; form the foundation for a national frame of identification and; contribute to a sense of American pride. From a production perspective, I have studied the specific case of the all-American fashion brand Tommy Hilfiger. Research has been conducted on how fashion can be considered as a means of national identification, supported by both the effective use of symbolic references and a unique branding strategy.

Fashion as a means of national identification

Hilfiger has carefully selected some elements of the American culture rather than others to create an ideal version of the American identity – an identity especially the younger population seems to consume and relate to. As Crane (2012) mentions, clothing has the power to exercise cultural agency and thereby influence the behaviour and attitudes of the person who wears it. By wearing Hilfiger’s clothes, the youth tends to feel part of the American dream lifestyle, a form of role-playing, solely by dressing accordingly.

Ethnic identities concern to what extent one relates to an ethnic group, thus a community which shares the same cultural background (Nagel, 1997). The focus of Hilfiger on expressing the national background of America is, therefore, a cultural trait many can relate to. Especially, in the contemporary social world where ethnic involvement is more concerned with the social construction of identity as a form of agency and several commercial companies are competing for the attention of the same consumers (Nagel, 1997; Crane, 2012). In these competitive environments, brand equity is enhanced by “leveraging a brand, or borrowing equity through linking the brand to another person, place, or thing.” (Keller, 2003, p. 595). Idolised America in this case.