Text

Good news its still there

Vienna Natural History Museum (NHMW)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vienna Natural History Museum (NHMW)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

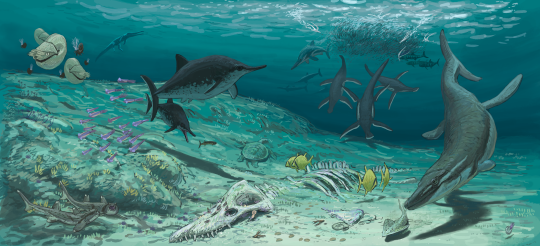

So this one was an absolute blast (and sometimes pain) to research in preparation for the stream and I love how Josch's piece came out.

And so that all that info isn't just hidden away I'll break this one down beyond the croc stuff. Big part of this was defining what would be used, which brings the often overlooked but important distinction between the Pebas Megawetlands as a whole and the Pebas Formation in particular. Obviously the latter was used for this piece, which largely removed other fossil localities like Fitzcarrald and most importantly La Venta of the Honda Group from the resource pool (La Venta being well known for its mammal fossils), but despite this there was still a lot of ground to cover.

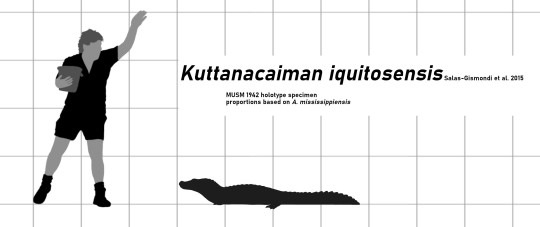

Starting with the crocs, the Pebas Formation might just be the formation with the single highest Cenozoic croc diversity. Sure in total theres more taxa in places like Urumaco, but in that case they are spread out across very different biomes. Meanwhile, all 7 Pebas crocodilians are known from the same localities. Of those 7, 4 are featured in the piece, covering most of the different morphotypes. The ones left out were Paleosuchus sp. (an extinct species of dwarf caiman), Kuttanacaiman and Caiman wannlangstoni (the latter two being ecologically too similar to one that is featured).

Images by Joschua Knüppe, Wann Langston, Andrzej Wolniewicz and yours truly.

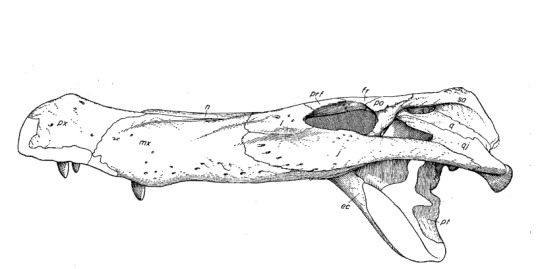

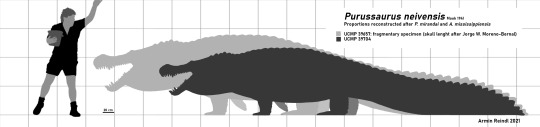

The first one that obviously had to be included was Purussaurus neivensis. I wager most are familiar with Purussaurus at least by hearsay, generally as "one of the biggest crocodilians" and all those estimates upwards of 10 meter in length. Purussaurus neivensis however is the oldest species in this genus and as such as nowhere near as big and has a notably less boxy head. It was still big mind you, when I scaled it some years ago I still got a size of 6 to 7 meters, though a paper published after that proposed a more modest 5 to 4 meters. Multiple localities have yielded bones of this thing and the locality of Na 069 has sloth fossils that bear bitemarks likely attributed to P. neivensis.

Images by Josch, yours truly and Salas-Gismondi R. et al.

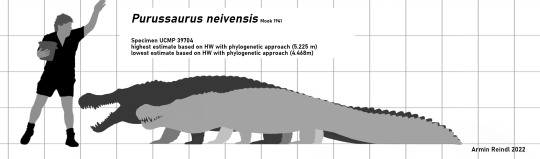

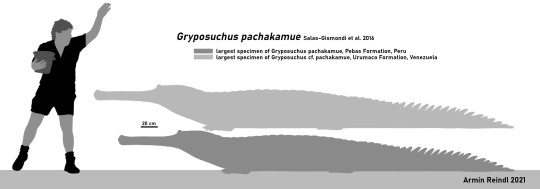

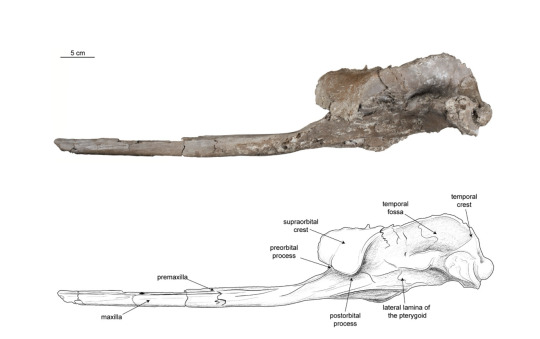

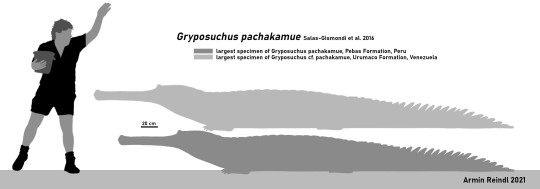

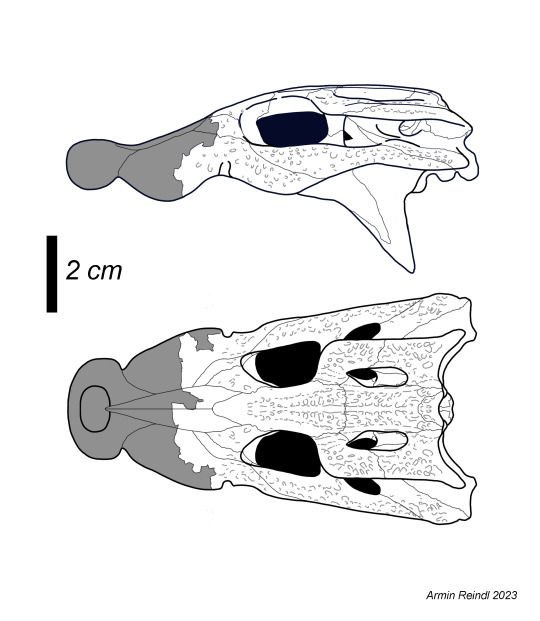

The second largest animal featured here is Gryposuchus pachakamue. Now as with Purussaurus, Gryposuchus is probably best known from its giant relatives like G. croizeti. Again the species encounted within the Pebas Formation is smaller and has some major anatomical differences, namely the fact that the eyes aren't telescoped. Quick context, if you look up the skull of modern gharials and derived Gryposuchus, you'll find that the rims of their eyes are raised, which elevetes the eyes. That's telescoping and not present in G. pachakamue. This might factor into habitat preferences and ecology. Telescope-eyed Gryposuchus are present in the Pebas Megawetlands, but do appear to stick to the edges and areas with flowing waters, like rivers, whereas G. pachakamue was found deeper in the oxygen-poor swamps. Another cool thing about this guy is that its the only crocodilian from the formation thats not a caiman, but a gharial. Long story short, gharials briefly colonized South America, thrived but sadly went extinct. Tho its possible that todays Indian Gharials are descendents of this South American radiation.

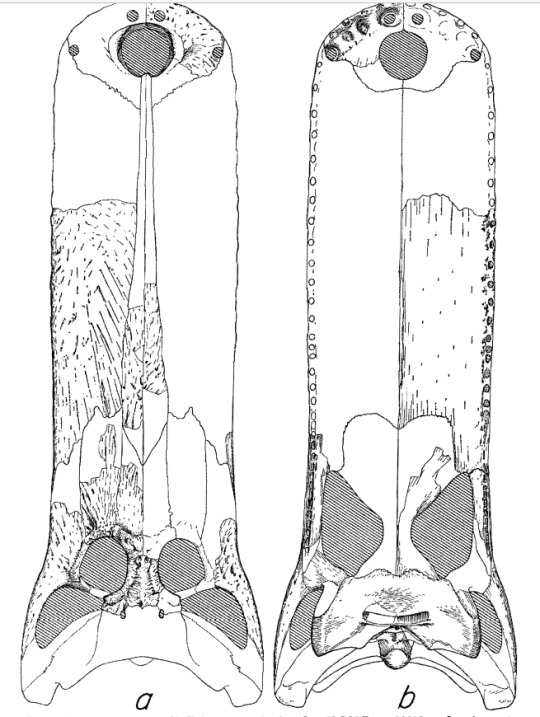

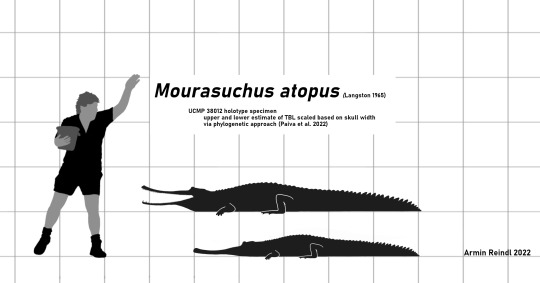

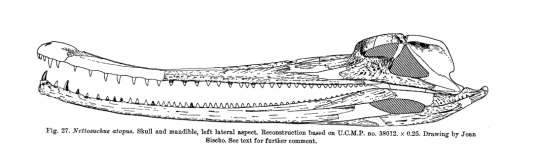

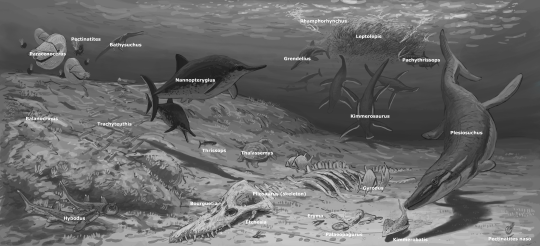

Artwork by Josch, skull reconstructions by Wann Langston, size comparisson by me

Third on our list is Mourasuchus atopus, which, I mean look at it. Mourasuchus takes us back to the caiman subfamily and it might just be the weirdest of the bunch. A flattened surfboard like head, highly telescoped eyes, lots of small teeth. These things are an enigma. Again the species present in this piece is on the smaller end of the spectrum and in general these animals are often way oversized in artwork and popular literature. The more interesting thing tho is their diet, which we still don't quite get. Theres been multiple hypothesis, including that it was a herbivore or that it waited with open jaws for fish to pass by. The hypothesis that has recieved the most attention is "filter feeding", tho the term is probably missleading as I'll explain. The idea is that Mourasuchus may have fed on small prey that could have hid in substrate or appeared in large numbers. Accordingly, it has often been depicted with a gullar pouch or similar to whales, largely based on a hypothesis erected for the unrelated Stomatosuchus, tho said hypothesis is not well supported either. Given that it lacks any obvious filter apparatus and may not have actually filtered anything, its perhaps more apt to describe it as a gulp feeder as used by Cidade et al. in their study. Which nicely leads into the name gulper caiman thats occasionally floated around.

Images by Joschua, Kevin Montalbán-Rivera and me

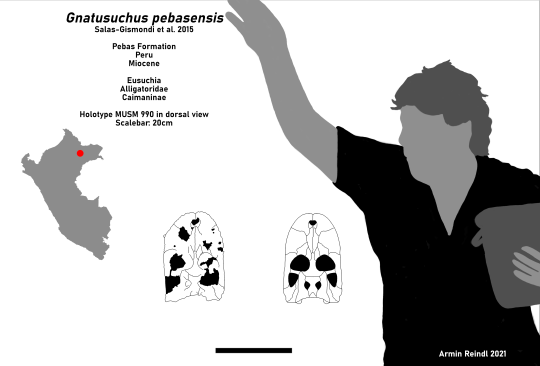

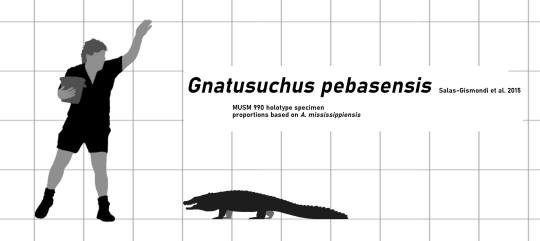

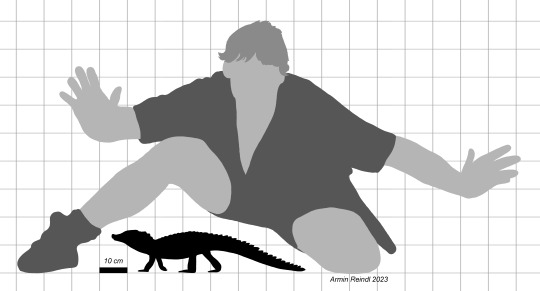

The final croc featured in this piece is Gnatusuchus (Nose Crocodile), the smallest of this selection at only around 1.5 meters long but not the smallest overall (that honour goes to the unnamed Paleosuchus species). Gnatusuchus represents the crusher morphotype. Basically, during this time period the wetlands had an incredibly diverse mollusc fauna with plenty of shellfish. These shellfish became prey to a variety of caimans that had blunt, globular teeth and generally shorter snouts. The afforementioned Kuttanacaiman and Caiman wannlangstoni both fall into this camp, but Gnatusuchus was probably the most extreme with its shovel-like skull and very round teeth. It is thought that they were the main predator of clams in the oxygen poor swamps, given that as air-breathers they didn't take issue to the water conditions in the same way that fish did.

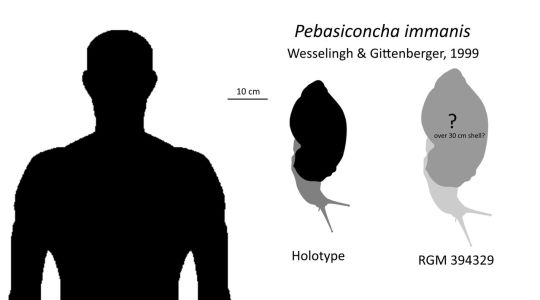

Live reconstructions by Joschua, Paradracaena skull by Matt Borths, Pebasiconcha size by Ta-tea-two-te-to

Crocs out of the way lets move on to other reptiles with Paradracaena and its would-be prey that I'll just cover here for simplicity. Now Paradracaena is an extinct relative of today's Caiman lizards and tegus and a good example of where La Venta really comes to help. The skull featured above is from La Venta for example, but we do have less complete fossils of this animal from the Pebas Formation, after all they are located within the same wetland system. Paradracaena was large, larger than modern caiman lizards and tegus, yet this one overestimates just how big its prey is. Pebasiconcha is among the largest known terrestrial snails with a size of possibly up to 30 cm (25 at the least of it), larger than even today's giant african land snails.

More hidden is this one, Colombophis, a relative of today's false coral snake. Now problem is, I know little to none about this animal so I'm afraid I cannot provide that much information on it other than that it was widespread across the megawetlands and its successor systems during the Miocene.

Joschua Knüppe and the University of California Museum of Paleontology

The final reptile to be covered is this guy, Chelus colombiana aka the Giant Mata Mata. This is another one that I know less about than I like and its been on my list to research and write about for a while, but to keep it brief Chelus colombiana is a relative of the modern mata mata turtle that reached a shell length of upwards of 70 centimeter. Given that Mata Matas have stupidly long necks, the full animal would probably exceed a meter in length. If I get around to it I'll go on a deep dive in the future, but I'll make no promises.

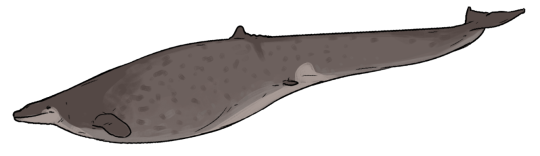

People who follow my blog should be familiar with this animal, given I've written a summary on it shortly after it was described (shameless plug here). Several cool things about this guy come to mind. Not only is Pebanista the largest river dolphin we know (at least of those that are described), measuring 3.5 meters in length, but its also entirely unrelated to the river dolphins that inhabit the Amazon today. Instead, as one might guess from the name, Pebanista is most closely related to the genus Platanista, which includes the Ganges and Indus river dolphins of South Asia. This family used to be a lot more common during the Oligocene prior to the rise of orcas, sperm whales and real dolphins, and both our modern ones and Pebanista seem to have fled competition into areas further inland. In the back you can also see manatees. Better known from other regions of the wetlands, manatees are known from the Pebas Formation itself through ribs and teeth.

Moving on to the remaining mammal fauna. Again this is far from my expertise so I'll have to keep things relatively brief. First and most obvious we got the ground sloth, Magdalenabradys. Remember when I mentioned that we have caiman bite marks on some fossil remains, yeah its this guy. Which makes it all the better that in Josch's illustration the latter seems to sneak up on the former. Now when said bitemarks were described the sloth was identified as Pseudoprepotherium, but some digging by the other members of Paleostream has found that the Pebas specimens were later moved to the genus Magdalenabradys (hell the name of the type species even references how common this confusion is). Next to it you'll find Potamarchus, relatives of today's Pacarana and Josephoartigasia, the largest rodent ever. A more distant cousin to these guys is seen in the background next to Mourasuchus, Neoepiblema. THe morphology of the hindlimbs and pelvis suggest that they could have been digging or swimming animals, the latter seeming quite likely given the types of environments inhabited by them. And finally there's the glyptodont, specifically, bear with me, Parapropalaehoplophorus. Not making this up. Now a consistent theme with the Pebas Formation mammals is how little we know of them. Again, La Venta is easily the superior formation when it comes to mammal fossils, wheras the Pebas Formation proper mostly preserves fragments of taxa found in the former.

Fish I'll just keep to a quick footnote, having reached another area where I just know little about these animals to the point where I feel like without doing a proper deepdive I might just accidentally get something wrong. The most interesting might be the cow-nosed rays and the sawfish. Sawfish of course still inhabit the Amazon to this day, so perhaps this ones not so surprising. The cow-nosed ray stands out more, but several papers indicate the presence of either Myliobatis (the eagle ray) or Rhinoptera (the cownose ray). The latter ended up being chosen due to the work of Chabain et al., who also named three different species of Potamotrygon (bottom left next to Purussaurus), which are your typical South American river rays. The rest of the fish fauna here falls into your typical modern Amazonian fauna (Pacus, Plecos, Piranhas, Cichlids and various catfish) with Pogonias being the one outlier featured, as its closest kin are found in the Atlantic Ocean (tho they do occasionally venture into freshwater from what I could gather). In general there are some fossil fish from the formation that are either offshoots of lineages that are still marine to this day or early offshoots of groups that would eventually become fully freshwater, highlighting how these fish, much like the dolphins, took the opportunity presented by these enormous wetlands to expand into new habitats.

And thats all I have to say, thankfully I somehow managed to keep this under Tumblrs 30 picture limit.

Result from the Pebas formation #paleostream!

Not as diverse as some other places he have hit and yet, we weren't even able to put in all the crocs.

#pebanista#gryposuchus#purussaurus#gnatusuchus#mourasuchus#chelus colombiana#paradracaena#pebasiconcha#sawfish#pacu#piranha#pebas#pebas formation#pebas megawetlands#peru#miocene#cenozoic#prehistory#paleontology#palaeoblr#paleostream#long post#fossils#magdalenabradys#neoepiblema#science#biology#swamp#Parapropalaehoplophorus#glyptodont

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a fun fact, during the early to middle Miocene the north of South America was covered by an enormous wetland system sometimes known as the Pebas Megawetlands, which was home to one of the single most-diverse collection of crocodilians in history.

Among them were a "small" species of Purussaurus that preyed on ground sloths, South American gharials, three different types of small caimans that fed on clams, a relative of todays dwarf caimans and the weird, surf-board headed Mourasuchus, all of which were recovered from a single locality.

If you wanna see more of this I highly recommend you check out @knuppitalism-with-ue stream tomorrow night, 23:00 CEST on Twitch.

#purussaurus#gryposuchus#kuttanacaiman#mourasuchus#gnatusuchus#paleosuchus#caiman#crocodilia#gharial#pebas#pebas megawetlands#paleostream#palaeoblr#prehistory#miocene

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sifting behavior is actually addressed in the description of Antaecetus, with the conclusion that the teeth were too gracile to be used that way (essentially trying to do so would abrade them into nothing see Skull and partial skeleton of a new pachycetine genus (Cetacea, Basilosauridae) from the Aridal Formation, Bartonian middle Eocene, of southwestern Morocco - PMC (nih.gov)), while the tooth wear of Pachycetus is shown to match well with orcas feeding on sharks (having several distinct types of wear visible on the teeth). Basilotritus (Cetacea: Pelagiceti) from the Eocene of Nagornoye (Ukraine): New data on anatomy, ontogeny and feeding of early basilosaurids - ScienceDirect

As for other basilosaurids, we have direct evidence of Basilosaurus itself preying on Dorudon.

Archaeocete predation (palaeo-electronica.org)

its also further worth noting that Krabeater seal teeth are much more complex, the secundary apices almost curve around to enclose the gaps. To my knowledge they also don't sift through sediment but feed on krill in free water. Not to mention that their closest relatives are the predatory leopard seals.

I am definitely curious to see if it could apply to Perucetus, given that grey whales are a potential analogue thrown out there, but we'll have to wait for skull material I suppose.

Pachycetinae: The Thick Whales

Oh look I'm way behind not only on my work with wikipedia but also in regards to summarizing it on tumblr. Good thing, three of the pages I've worked on these past few months can just be summed up in one post because they are all one family.

So Pachycetinae, at the most basic level, are basilosaurid archaeocetes, the group that famously includes Basilosaurus and Dorudon. Reason I've picked up the articles in addition to my usual croc work, basically a friend and I noticed how lacklustre many pages are and stupidly decided to start revising all of Cetacea (pray for me).

Currently theres two genera within the group. Pachycetus aka Platyosphys aka Basilotritus, which is a whole mess I will get into at the end for those interested, and Antaecetus, which I'll just call "the good one" for now. Among those are three species. Pachycetus paulsonii (or Basilotritus uheni) from continental Europe (Germany and Ukraine mostly), Pachycetus wardii (Eastern United Staates) and Antaecetus aithai (Morocco and Egypt)

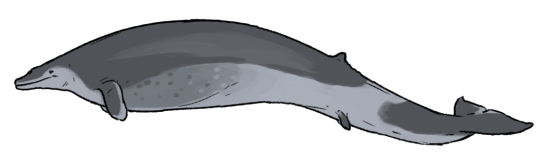

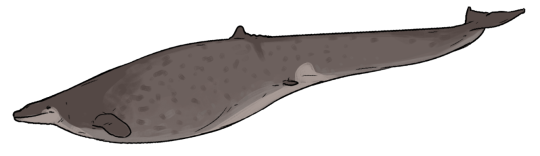

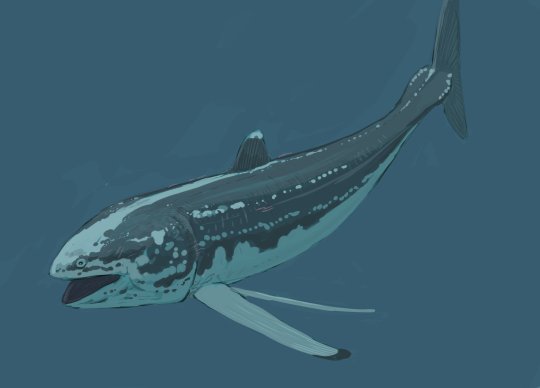

Picture: Pachycetus and Antaecetus by Connor Ashbridge

So the hallmark of Pachycetines, as the name would suggest, is the fact that their skeletons are notably denser than that of other basilosaurids. The vertebrae, the most abundant material of these whales, are described as pachyostatic and osteosclerotic. The former effecitvely means that the dense cortical bone forms thickened layers, while the latter means that the cortical bone, already forming thickened layers, is furthermore denser than in other basilosaurids with less porosities. The densitiy is increased further by how the ribs attack to the vertebrae not through sinovial articulation but through cartilage, so adding even more weight to them. Overall this is at times compared to manatees, famous for their dense skeletons.

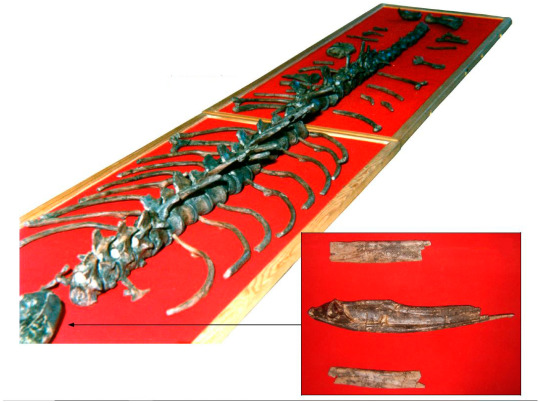

Pictured below, the currently best preserved pachycetine fossil, an individual of the genus Antaecetus from Morocco.

Now there are some interesting anatomical features to mention that either differ between species or just can't be compared. For example the American species of Pachycetus, P. wardii, shows a well developed innominate bone, basically the fused pelvic bones. This is curious as one would think of it as a more basal feature, with derived whales gradually reducing them. The skull is best preserved in Antaecetus and has a very narrow snout. One way to differentiate the two is by the teeth. Pachycetus has larger, more robust teeth while that of Antaecetus are way more gracile and is thought to have had a proportionally smaller skull (in addition to being smaller than Pachycetus in general).

All of this has some interesting implications for their ecology. For instance, why the hell are they so dense? Well its possible that they were shallow water animals using their weight as ballast, staying close to the ocean floor. This would definitely find some support in the types of environments they show up in, which tend to be shallow coastal waters. There are some Ukrainian localities that suggest deeper waters, but that has been interpreted as being the result of migration taking them out of their prefered habitat.

Now while pachycetines were probably powerful swimmers, their dense bones mean that they were pretty slow regardless. And to add insult to injury, they were anything but maneuverable. Remember those long transverse processes? Turns out having them extend over the majority of the vertebral body means theres very little space for muscles in between, which limits sideways movements.

From this one can guess that they weren't pursuit predators and needed to ambush their prey. What exactly that was has been inferred based on tooth wear. Basically, the teeth of Pachycetus show a lot of abrasion and wear, not dissimlar to what is seen in modern orcas that feed on sharks and rays. And low and behold, sharks are really common in the same strata that Pachycetus shows up in. Now since Antaecetus had way more gracile teeth, its thought that it probably fed on less well protected animals like squids and fish.

Below: Pachycetus/Basilotritus catching a fish.

The relationship between pachycetines and other basilosaurids is wonky, again no thanks due to Pachycetus itself being very poorly known. Some studies have suggested that they were a very early branching off-shoot, in part due to their prominent hip bones, but in the most recent study to include them, the description of Tutcetus, they surprisingly came out as not just the most derived basilosaurids but as the immediate sister group to Neoceti, which includes all modern whales. Regardless, in both instances they seem to clade closely with Supayacetus, a small basilosaurid from Peru.

And now for the part that is the most tedious. Taxonomy and history.

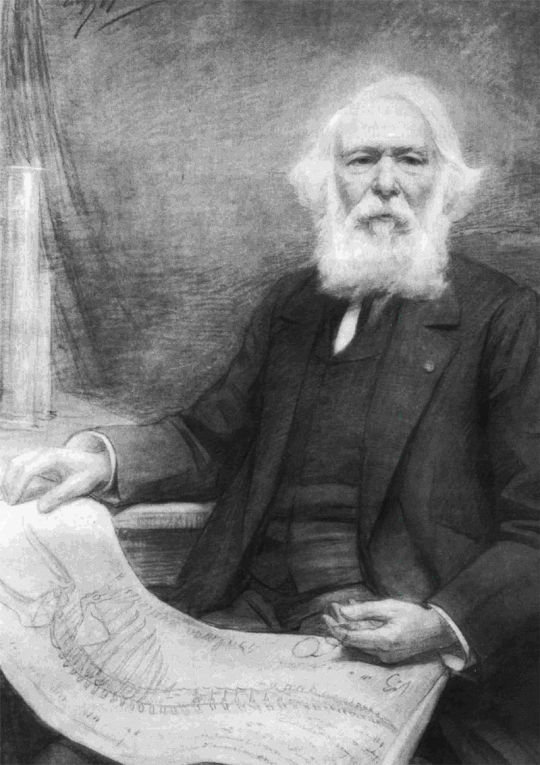

Remains of pachycetines have been known for a while and were first described as early as 1873 by Russian scientists. To put into perspective how old that is. The material's history in science predates both World Wars, the collapse of the Russian Empire and even the reign of Tsar Nicholas II. Now initially the idea was to name the animal Zeuglodon rossicum, but the person doing the actual describing changed that to Zeuglodon paulsonii reasoning that it would eventually be found outside of Russia (something that aged beautifully given that Ukraine would eventually become independent).

And this is where the confusion starts to unfold. Because at the same time people unearthed pachycetine fossils in Germany too, which would come be given the name Pachycetus (thick whale) and be established as two species. Pachycetus robustus and Pachycetus humilis, both thought to be baleen whales.

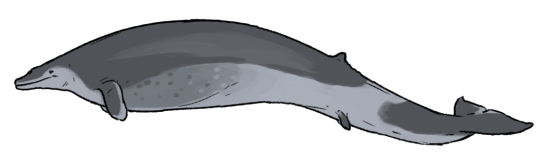

Pictured below: Pierre-Joseph van Beneden who coined Pachycetus and Johann Friedrich Brandt who described Zeuglodon paulsonii. Beneden easily has the better beard.

These latter two names however were later rejected in 1935 by Kuhn and lumped into other species, whereas Zeuglodon paulsonii was elevated to a full on new genus by Remington Kellogg in 1936. For those curious, Platyosphys means "broad loin", in combination with the species "Paulson's broad loin" to the amusement of some friends of mine.

And then people stopped caring and we have a nearly 70 year research gap. Eventually Mark D. Uhen found fossil material in the United States, but interpreted those fossils as being part of the genus Eocetus, naming them Eocetus wardii, a move that many following researchers disagreed with.

Then in 2001 a new species of Platyosphys, P. einori, was named. It's bad, moving on. More importantly, we got the works of Gol'din and Zvonok, who attempted to bring some clarity into the whole thing. To do so they rejected the name Platyosphys on account of the holotype having been lost sometime in WW2 and picked out much better fossil material to coin the genus Basilotritus ("the third king" in allusion to Basilosaurus "king lizard" and Basiloterus "the other king", isn't etymology fun?). They erected the type species Basilotritus uheni and then proclaimed Eocetus wardii to also belong into this genus, making it Basilotritus wardii.

This move was however not followed by other researchers. Gingerich and Zhouri maintained that regardless of being lost, Platyosphys is still valid and can be sufficiently diagnosed by the original drawings from the 19th and early 20th century. And to take a step further they added a new species, Platyosphys aithai (weird, why does that name sound familiar).

Then Van Vliet came and connected all these dots I've set up so far, noting that the fossils of Platyosphys are nearly identical to those of Pachycetus. This lead to the fun little thing were "paulsonii", applied first to Zeuglodon in the 1870s, takes priority over "robustus", coined just a few years later, BUT, the genus name Pachycetus easily predates Platyosphys by a good 60 years. Subsequently, the two were combined. Platyosphys paulsonii and Pachycetus robustus became Pachycetus paulsonii (simplified*). Van Vliet then deemed humilis to be some other whale and carried over Basilotritus uheni, Basilotritus wardii and Platyosphys aithai into the genus Pachycetus. *Technically Pachycetus robustus was tentatively kept as distinct only because of how poorly preserved it was, making comparisson not really possible.

Then finally in the most recent paper explicitly dealing with this group, Gingerich and Zhouri came back, killed off P. robustus for good, sunk Pachycetus uheni into Pachycetus paulsonii for good measure and decided to elevate Pachycetus aithai to genus status after finding a much better second skeleton, coining Antaecetus (after the giant of Greek myth).

And that's were we are right now. Three species in two genera, but only one of them is actually any good. So perhaps at some point in the future we might see some further revisions on that whole mess and who knows, perhaps Basilotritus makes a glorious comeback.

To conclude, sorry about the lack of images, despite the ample history theres just not much good material aside from that one Antaecetus fossil and I didn't want to include 5 different drawings in lateral view.

Obligatory Wikipedia links:

Pachycetinae - Wikipedia

Antaecetus - Wikipedia

Pachycetus - Wikipedia

Ideally Supayacetus will be the next whale I tackle, distractions and other projects not withstanding (who knows maybe I'll finally finish Quinkana)

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pachycetinae: The Thick Whales

Oh look I'm way behind not only on my work with wikipedia but also in regards to summarizing it on tumblr. Good thing, three of the pages I've worked on these past few months can just be summed up in one post because they are all one family.

So Pachycetinae, at the most basic level, are basilosaurid archaeocetes, the group that famously includes Basilosaurus and Dorudon. Reason I've picked up the articles in addition to my usual croc work, basically a friend and I noticed how lacklustre many pages are and stupidly decided to start revising all of Cetacea (pray for me).

Currently theres two genera within the group. Pachycetus aka Platyosphys aka Basilotritus, which is a whole mess I will get into at the end for those interested, and Antaecetus, which I'll just call "the good one" for now. Among those are three species. Pachycetus paulsonii (or Basilotritus uheni) from continental Europe (Germany and Ukraine mostly), Pachycetus wardii (Eastern United Staates) and Antaecetus aithai (Morocco and Egypt)

Picture: Pachycetus and Antaecetus by Connor Ashbridge

So the hallmark of Pachycetines, as the name would suggest, is the fact that their skeletons are notably denser than that of other basilosaurids. The vertebrae, the most abundant material of these whales, are described as pachyostatic and osteosclerotic. The former effecitvely means that the dense cortical bone forms thickened layers, while the latter means that the cortical bone, already forming thickened layers, is furthermore denser than in other basilosaurids with less porosities. The densitiy is increased further by how the ribs attack to the vertebrae not through sinovial articulation but through cartilage, so adding even more weight to them. Overall this is at times compared to manatees, famous for their dense skeletons.

Pictured below, the currently best preserved pachycetine fossil, an individual of the genus Antaecetus from Morocco.

Now there are some interesting anatomical features to mention that either differ between species or just can't be compared. For example the American species of Pachycetus, P. wardii, shows a well developed innominate bone, basically the fused pelvic bones. This is curious as one would think of it as a more basal feature, with derived whales gradually reducing them. The skull is best preserved in Antaecetus and has a very narrow snout. One way to differentiate the two is by the teeth. Pachycetus has larger, more robust teeth while that of Antaecetus are way more gracile and is thought to have had a proportionally smaller skull (in addition to being smaller than Pachycetus in general).

All of this has some interesting implications for their ecology. For instance, why the hell are they so dense? Well its possible that they were shallow water animals using their weight as ballast, staying close to the ocean floor. This would definitely find some support in the types of environments they show up in, which tend to be shallow coastal waters. There are some Ukrainian localities that suggest deeper waters, but that has been interpreted as being the result of migration taking them out of their prefered habitat.

Now while pachycetines were probably powerful swimmers, their dense bones mean that they were pretty slow regardless. And to add insult to injury, they were anything but maneuverable. Remember those long transverse processes? Turns out having them extend over the majority of the vertebral body means theres very little space for muscles in between, which limits sideways movements.

From this one can guess that they weren't pursuit predators and needed to ambush their prey. What exactly that was has been inferred based on tooth wear. Basically, the teeth of Pachycetus show a lot of abrasion and wear, not dissimlar to what is seen in modern orcas that feed on sharks and rays. And low and behold, sharks are really common in the same strata that Pachycetus shows up in. Now since Antaecetus had way more gracile teeth, its thought that it probably fed on less well protected animals like squids and fish.

Below: Pachycetus/Basilotritus catching a fish by @knuppitalism-with-ue

The relationship between pachycetines and other basilosaurids is wonky, again no thanks due to Pachycetus itself being very poorly known. Some studies have suggested that they were a very early branching off-shoot, in part due to their prominent hip bones, but in the most recent study to include them, the description of Tutcetus, they surprisingly came out as not just the most derived basilosaurids but as the immediate sister group to Neoceti, which includes all modern whales. Regardless, in both instances they seem to clade closely with Supayacetus, a small basilosaurid from Peru.

And now for the part that is the most tedious. Taxonomy and history.

Remains of pachycetines have been known for a while and were first described as early as 1873 by Russian scientists. To put into perspective how old that is. The material's history in science predates both World Wars, the collapse of the Russian Empire and even the reign of Tsar Nicholas II. Now initially the idea was to name the animal Zeuglodon rossicum, but the person doing the actual describing changed that to Zeuglodon paulsonii reasoning that it would eventually be found outside of Russia (something that aged beautifully given that Ukraine would eventually become independent).

And this is where the confusion starts to unfold. Because at the same time people unearthed pachycetine fossils in Germany too, which would come be given the name Pachycetus (thick whale) and be established as two species. Pachycetus robustus and Pachycetus humilis, both thought to be baleen whales.

Pictured below: Pierre-Joseph van Beneden who coined Pachycetus and Johann Friedrich Brandt who described Zeuglodon paulsonii. Beneden easily has the better beard.

These latter two names however were later rejected in 1935 by Kuhn and lumped into other species, whereas Zeuglodon paulsonii was elevated to a full on new genus by Remington Kellogg in 1936. For those curious, Platyosphys means "broad loin", in combination with the species "Paulson's broad loin" to the amusement of some friends of mine.

And then people stopped caring and we have a nearly 70 year research gap. Eventually Mark D. Uhen found fossil material in the United States, but interpreted those fossils as being part of the genus Eocetus, naming them Eocetus wardii, a move that many following researchers disagreed with.

Then in 2001 a new species of Platyosphys, P. einori, was named. It's bad, moving on. More importantly, we got the works of Gol'din and Zvonok, who attempted to bring some clarity into the whole thing. To do so they rejected the name Platyosphys on account of the holotype having been lost sometime in WW2 and picked out much better fossil material to coin the genus Basilotritus ("the third king" in allusion to Basilosaurus "king lizard" and Basiloterus "the other king", isn't etymology fun?). They erected the type species Basilotritus uheni and then proclaimed Eocetus wardii to also belong into this genus, making it Basilotritus wardii.

This move was however not followed by other researchers. Gingerich and Zhouri maintained that regardless of being lost, Platyosphys is still valid and can be sufficiently diagnosed by the original drawings from the 19th and early 20th century. And to take a step further they added a new species, Platyosphys aithai (weird, why does that name sound familiar).

Then Van Vliet came and connected all these dots I've set up so far, noting that the fossils of Platyosphys are nearly identical to those of Pachycetus. This lead to the fun little thing were "paulsonii", applied first to Zeuglodon in the 1870s, takes priority over "robustus", coined just a few years later, BUT, the genus name Pachycetus easily predates Platyosphys by a good 60 years. Subsequently, the two were combined. Platyosphys paulsonii and Pachycetus robustus became Pachycetus paulsonii (simplified*). Van Vliet then deemed humilis to be some other whale and carried over Basilotritus uheni, Basilotritus wardii and Platyosphys aithai into the genus Pachycetus. *Technically Pachycetus robustus was tentatively kept as distinct only because of how poorly preserved it was, making comparisson not really possible.

Then finally in the most recent paper explicitly dealing with this group, Gingerich and Zhouri came back, killed off P. robustus for good, sunk Pachycetus uheni into Pachycetus paulsonii for good measure and decided to elevate Pachycetus aithai to genus status after finding a much better second skeleton, coining Antaecetus (after the giant of Greek myth).

And that's were we are right now. Three species in two genera, but only one of them is actually any good. So perhaps at some point in the future we might see some further revisions on that whole mess and who knows, perhaps Basilotritus makes a glorious comeback.

To conclude, sorry about the lack of images, despite the ample history theres just not much good material aside from that one Antaecetus fossil and I didn't want to include 5 different drawings in lateral view.

Obligatory Wikipedia links:

Pachycetinae - Wikipedia

Antaecetus - Wikipedia

Pachycetus - Wikipedia

Ideally Supayacetus will be the next whale I tackle, distractions and other projects not withstanding (who knows maybe I'll finally finish Quinkana)

#pachycetinae#pachycetus#basilotritus#platyosphys#antaecetus#archaeocete#prehistory#paleontology#palaeoblr#basilosauridae#eocene#whale

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Giant Turtle and the River Dolphin

Fans of Cenozoic South America are eating good this month. Within Just a week we were introduced to two amazing new taxa. One a giant river turtle that might have encountered the first humans to have reached the continent, the other a much more ancient river dolphins with ties to Asia.

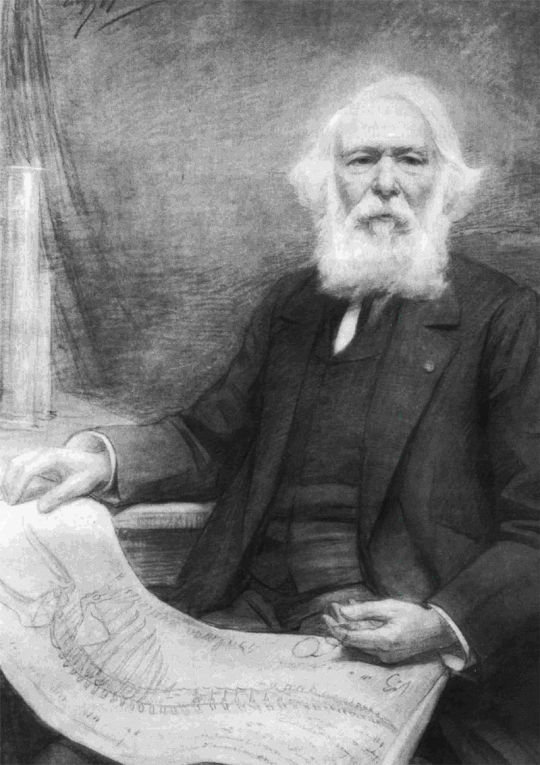

Peltocephalus maturin

Starting with the turtle we have Peltocephalus maturin, a species within the still extant genus Peltocephalus, which previously only included the big-headed Amazon river turtle. Tho only known from a singular lower jaw, what makes this animal impressive is its shere size.

Images:

Gabriel S. Ferreira (right) with the holotype lower jaw

Size comparisson based on the paper's size estimates

Yup. That is enormous. Size estimates have yielded an incredible 1.7 meters straight carapace length (just under 6ft). That makes Peltocephalus maturin not only one of the biggest freshwater turtles period (behind the likes of Stupendemys), but easily the biggest river turtle of the recent past. That's also the backstory behind the name, which references Maturin, a celestial tortoise from the works of Stephen King. Because this thing wasn't some native of the ancient Miocene wetlands of South America, no this one was recent. It is thought that Peltocephalus maturin lived only around 14.000 to 9.000 years ago and thus could have reasonably encountered the first humans to arrive in South America.

Artwork by the always talented Júlia d'Oliveira and @knuppitalism-with-ue

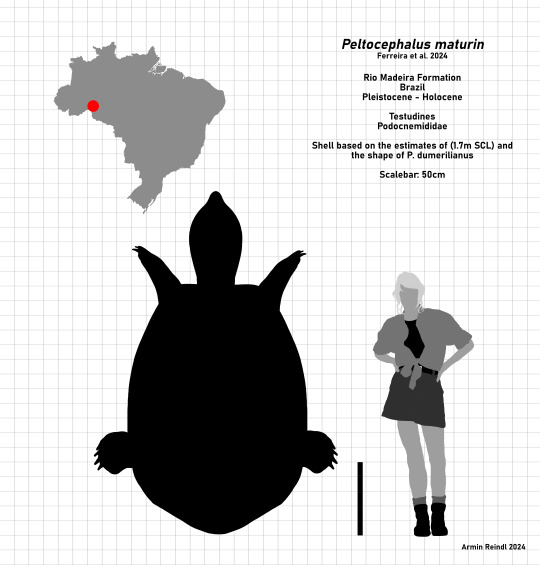

Pebanista yacuruna

The second really cool Cenozoic South American discovery of the past week I wanna mention is Pebanista yacuruna, a species of river dolphin from the Miocene Pebas Formation, so it and Peltocephalus wouldn't have met sadly enough (tho it would have coexisted with even bigger river turtles). It's also way more complete, having a nearly complete skull just missing a few areas including the very tip of the snout.

There are two stand out things about Pebanista. For one, much like with Peltocephalus maturin, it is noted for its size. Estimates based on the width of the skull would suggest a total length of 2.8 meters, with a fragmentary second specimen possibly pushing this up to 3.4 meters. This makes Pebanista the largest known freshwater cetacean and comparable in size to its marine relatives. One possible reason for this is just how productive its ecosystem was. For context, it inhabited the Pebas Megawetlands, an enormous wetland system that stretched across most of modern Amazonia during the Miocene and was home to enormous caimans, giant turtles, sloths and all sorts of other animals. And importantly, plenty of prey for a dolphin.

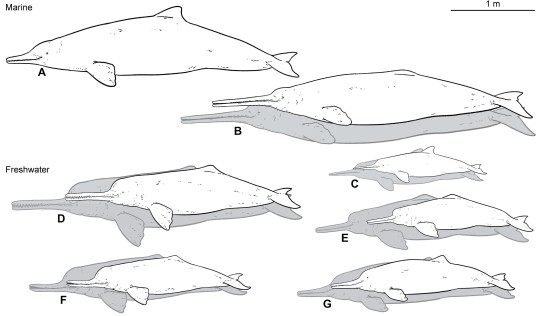

Image:

Size comparisson of various cetaceans. A) and B) are marine platanistids (Macrosqualodephis and Zarhachis), C) the La Plata Dolphins, D) Pebanista, E) the Amazon river dolphin, F) the Ganges river dolphin and G) the baiji or Chinese river dolphin, artwork by Jaime Bran

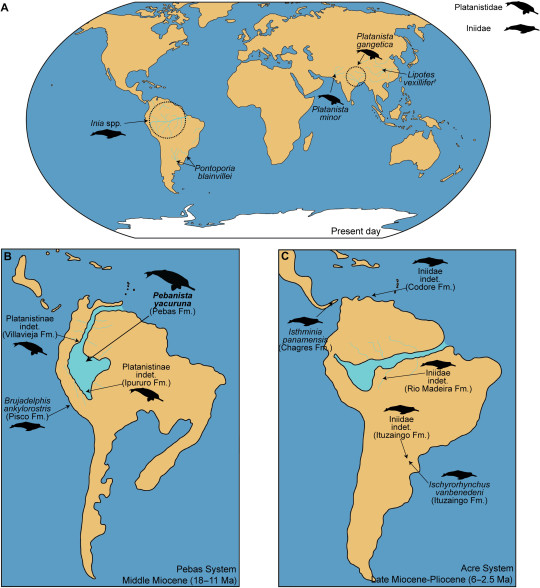

The second thing needs a little bit of background knowledge. Something that not all people know is that today's river dolphins are actually four separate families not all that closely related to another. There's the South American river dolphins (Iniidae), the La Plata Dolphin (Pontoporiidae, though they are not exclusively freshwater), the possibly extinct baiji (Lipotidae) and the two South Asian river dolphins (Platanistidae). Now though the first three do clade together, all four groups are known to have become freshwater animals independently from each other, all having marine ancestors that just so happened to enter rivers.

Image:

the current (a), Early to Mid Miocene (b) and Late Miocene (c) distribution of river dolphins

So what's interesting with Pebanista is that, although being found in an area today inhabited by the South American river dolphins, it was actually not related to them. Instead, Pebanista, as you might have guessed from the name, is most closely related to the Ganges and Indus river dolphins (Platanista gangetica and Platanista minor). Based on stratigraphy, it would seem that platanistids, which used to be very common during the Oligoce and Miocene (before being replaced by proper dolphins of the Delphinidae), entered the freshwaters of South America, brought forth Pebanista, went extinct for unknown reasons and were eventually succeeded by members of the Iniidae taking on a similar niche leading to the modern Amazon river dolphins.

Images:

Pebanista as illustrated by Jaime Bran (left) and its closest known relative, the Ganges river dolphin photographed by @ganeshwildlife91 (right)

And one last thing. Pebanista has a prominent supraorbital crest, essentially a bony structure that extends over the melon of the animal and might have been used to focus its biosonar while hunting in murky waters. This structure is very similar, tho smaller, than the one seen in modern Platanista and probably was an early stage in the nightmare that is the skull of modern South Asian river dolphins. Enjoy.

Sources and Wikipedia plug:

The latest freshwater giants: a new Peltocephalus (Pleurodira: Podocnemididae) turtle from the Late Pleistocene of the Brazilian Amazon | Biology Letters (royalsocietypublishing.org)

Peltocephalus maturin - Wikipedia

The largest freshwater odontocete: A South Asian river dolphin relative from the proto-Amazonia | Science Advances

Pebanista - Wikipedia

#peltocephalus#peltocephalus maturin#pebanista#pebanista yacuruna#podocnemididae#platanistidae#river dolphin#river turtle#cetacea#turtle#whale#miocene#south america#paleontology#palaeoblr#prehistory#fossils#paleo news#long post

13 notes

·

View notes

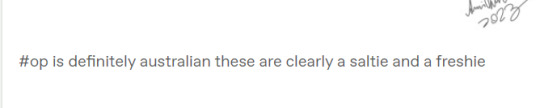

Photo

Classic post, might as well chuck in my own contribution

the differences between crocodiles and alligators in case u were not aware

208K notes

·

View notes

Text

I actually intentionally kept the long-snouted one generic rather than going for any species in particular. So theres a bit of gharial, a bit of Tomistoma, and so forth in that.

Sorry to disappoint, I'm not an Ausie myself either.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

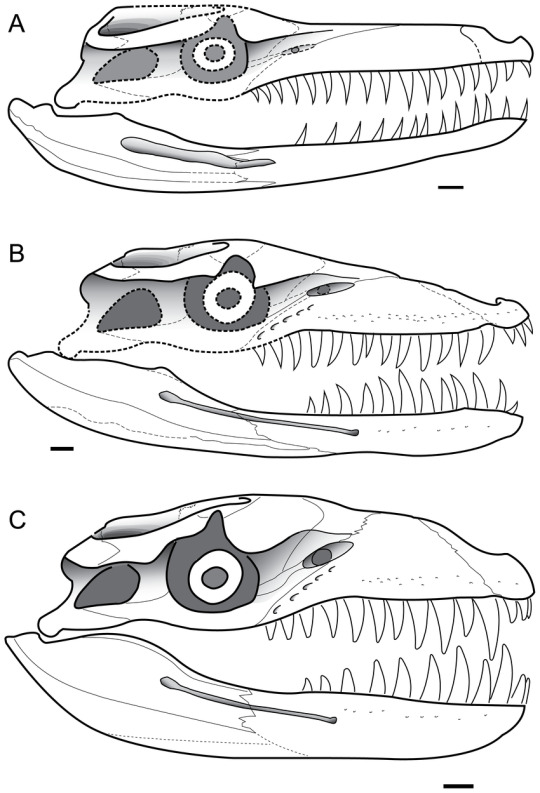

Two more croc-line archosaurs to dig into with this one and both are super fascinating.

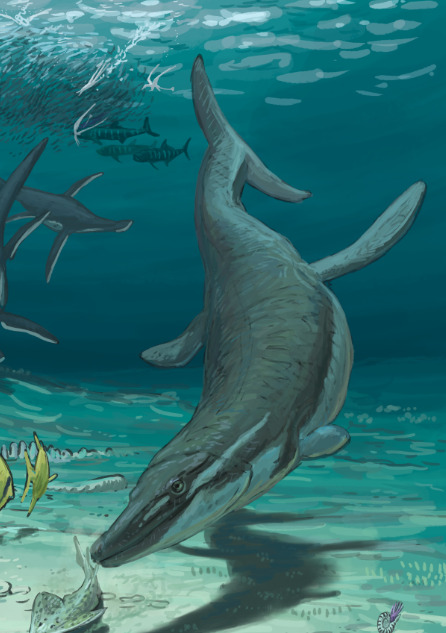

Obviously the star of this piece is our friend in the foreground, Plesiosuchus manselii, the largest of the fully marine metriorhynchids (the skull of which being the first one shown in the image to the right, taken from Young et al. 2012)

More broadly speaking, metriorhynchids are a fascinating group of early croc-relatives that stand out for having returned completely back into the water, developing a fluked tail, tiny little reduced forelimps, flipper like hindlimbs and smooth skin entirely lacking in the osteoderm armour we so strongly associate with pseudosuchians.

Plesiosuchus specifically is the largest of them. Close to 7 meters in length, it's basically in the same range as Liopleurodon (although smaller than several of the pliosaurs we know from the Kimmeridge Clay like that very decorative skeleton). Plesiosuchus actually wasn't the only metriorhynchid from the formation either. We also know of the small Cricosaurus, the name-giving Metriorhynchus and most interestingly the large-bodied Dakosaurus and Torvoneustes, which were likely to reach lengths of 4.5 to 4.7 meters respectively. At least with metriorhynchids this diversity can be explained in the different animals having very different preferences. Torvoneustes is interpreted as a durophage, feeding on hard-shelled prey. Dakosaurus is characterized by slicing dentition, potentially able to cut apart large prey with tooth wear possibly suggesting sharks or suction feeding habits. Plesiosaurus meanwhile would be able to take on large prey simply due to its great size and large gape but may have been limited by the size of its own head.

The other marine "croc" in the image is Bathysuchus, which may be described as a cousin to the metriorhynchids.

Remember Machimosaurus from the Guimarota locality that Josch drew a few weeks back? Yeah its related to that one. A teleosauroid to be precise, which are the sister group to metriorhynchoids and appear much more croc-like in their appearance despite still being a long way off from crocodiles in the strict sense. Teleosauroids may appear like what you'd think of as basal to metriorhynchoids, but they simply did their own thing after diverging, thus retaining this more ancestral bauplan with more developed limbs, more croc-like skulls and maintaining their armour plating (keep that in mind).

Bathysuchus is kind of a weird one tho. Why? Because from what we can tell Bathysuchus seems to have tried to become more like its metriorhynchoid cousins. It's known from deeper waters, its osteoderms were much more reduced and if the closely related Aelodon is anything to go from then its quite likely that this guy also started reducing the size of its forelimbs. In short, adaptations to a more pelagic lifestyle that moves away from the coastal habitat other teleosauroids seem to have preferred. Who knows, maybe its possible that in some other timeline these guys might have become something akin to metriorhynchoids like what happened with mosasaurs.

Unlike metriorhynchoids, teleosauroids were way less common in the Kimmeridge Clay, hell, to my knowledge Bathysuchus is the only one of them, a pretender among the other pelagic pseudosuchians.

Result from the Kimmeridge Clay #paleostream!

We were only able to scratch the surface, but I think you get the idea ;)

#bathysuchus#plesiosuchus#kimmeridge clay#crocs#pseudosuchia#crocodile#metriorhynchidae#metriorhynchoidea#teleosauroidea#thalattosuchia#crocodyliform#jurassic#marine croc#paleostream#palaeoblr

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

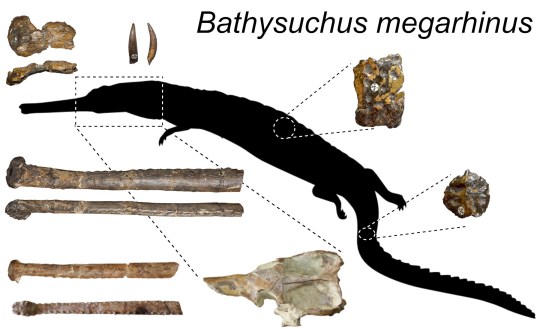

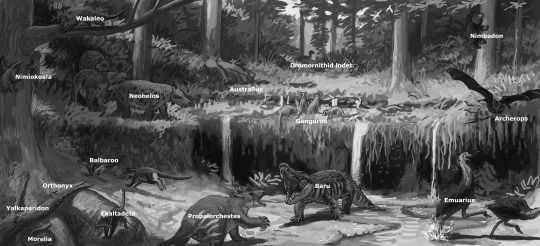

I've been blessed with the amount of croc-bearing formations covered by Josch. Riversleigh is another exceptional example. This piece was based on the late Miocene localities, primarily AL90 and the Ringtail Site.

Obviously the main animal here is Baru, the cleaver-headed crocodile. Some 4 meters long with enormous recurved teeth and a skull way more robust than that of any modern crocodile. One hypothesis goes that the reason for this is that Baru couldn't really drown its prey due to how shallow the water was, which meant it had to dispatch of it quickly. Thus, inflict a lot of damage with one bite and be done with it.

The Ringtail Site was also home to two other crocodiles, both on the smaller side of things. Trilophosuchus and Mekosuchus sanderi are somewhere between 70 centimeters to a meter long, likely more terrestrial and neither one made it in, but I wanna shout them out anyways because really at that size they are simply adorable.

The Riversleigh obviously includes a variety of other localities that range from all the way back in the Oligocene to as recent as the Pleistocene, meaning the croc fauna is even more extensive than what is known from Ringtail and AL90. This includes the slender-snouted Ultrastenos, the terrestrial Quinkana as well as the very recent Paludirex gracilis and today's freshwater crocodile.

And so the Riversleigh #paleostream concluded! Lots of weird marsupials in this one. Since we chose to depict here a Miocene faunal zone you will not come across your typical Australian megafauna, like Diprotodon and Dromornis, that stuff came later.

We are looking at their ancestors, before the rainforest collapse.

Here some detail shots. Next time we will visit the Kimmeridge clay, a late Jurassic marine ecosystem.

#riversleigh#ringtail site#trilophosuchus#mekosuchus#baru#baru darrowi#mekosuchinae#miocene#australia#croc#crocodile#palaeoblr

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

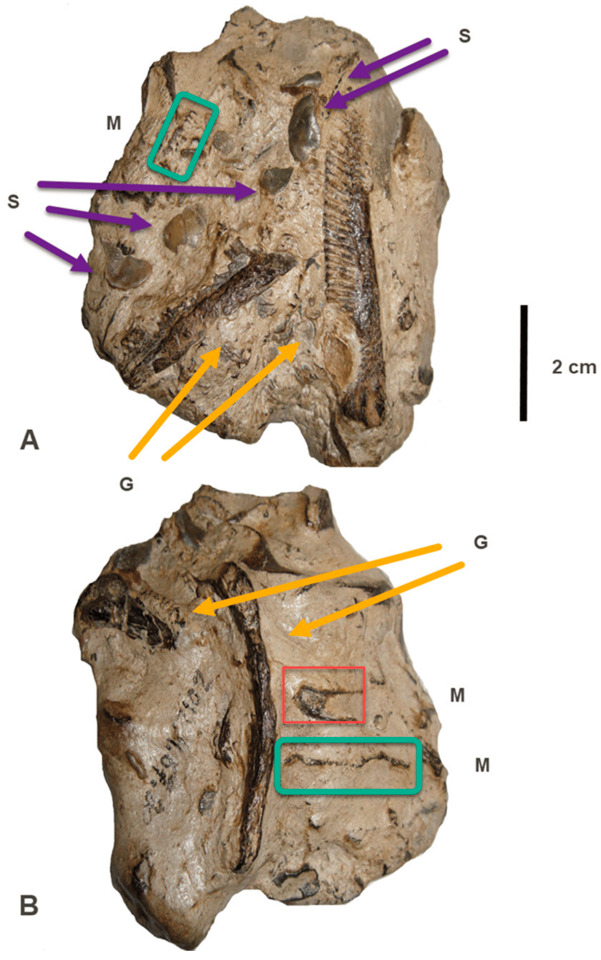

Thalattosuchus and Leedsichthys

Quickly stopping by to report on a new paper describing stomach contents of a thalattosuchian (Jurassic marine crocodile).

The paper in brief describes a specimen of Metriorhynchus superciliosus (aka Thalattosuchus) with preserved stomach contents, which is already rare enough as is. What's even more interesting is that the stomach contents preserve both the gill rakes of the large fish Leedsichthys as well as various mollusc shells. Strange prey for what's a rather small piscivore. Although it was previously suggested that Metriorhynchus/Thalattosuchus attacked living Leedsichthys, this appears to have been based on missinterpreted evidence and given the enormous size difference its way more likely that the fish was simply scavenged, sorta like a kind of Jurassic whalefall. This actually finds support in the mollusc shells, which might have been ingested on accident alongside the fish remains.

Top left: The skeleton of this Thalattosuchus specimen

Top right: The stomach contents in detail (G are gill rakes, S are shells)

Bottom left: Live reconstriction of Thalattosuchus by Gabriel Ugueto

Bottom right: Live reconstruction of Leedsichthys by @knuppitalism-with-ue

The paper itself:

Fossil Studies | Free Full-Text | The Diet of Metriorhynchus (Thalattosuchia, Metriorhynchidae): Additional Discoveries and Paleoecological Implications (mdpi.com)

#thalattosuchus#thalattosuchia#metriorhynchus#metriorhynchidae#leedsichthys#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#jurassic

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another formation stream another fascinating croc to give a shout out to. Voay robustus is a close relative of Crocodylus, the genus of today's true crocodiles.

Probably the most prominent thing about Voay is the pair of large squamosal horns, earning it the English name "horned crocodile". Squamosal horns are far from rare, having appeared independently in several species including modern Siamese and Cuban crocodiles. But they were especially prominent in Voay.

Minor sidenote I do admire the colouration, having previously been featured in Joschua's "Giants Among Us: Crocodiles" Map (proudly hung up on my wall) and his Island Fauna: Madagascar size chart

Another Saturday another formation stream!

This time we visited the subfossil wonders of Madagascar!

411 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two lovely crocs in this one, there's the medium-sized (2-2.5 meter) Confractosuchus which we know for a fact ate dinosaurs (based on the fact that we found an ornithopod in its stomach). And on the right there's Isisfordia which probably only grew up to a meter in length. Both are Neosuchians, tho its not entirely certain how they relate to modern forms, with papers sometimes featuring them within Eusuchia and sometimes outside of it.

And so here is the result of the Winton Formation stream!

Home of Australovenator, a bunch of sauropods and lots of other critters. Preserved in this formation are the animal of a coastal river system.

Have some detail shots as well

718 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very fun thing about this image is that it features three pseudosuchians, none of which are all that closely related to each other.

In the background you have the most superficially croc-shaped ones. Machimosaurus hugii and Goniopholis baryglyphaeus.

Machimosaurus, the big one in the back, might look like a gharial of sorts, but its actually a teleosaur, which falls into the clade Thalattosuchia. Thalattosuchia, which also includes the pseudosuchian version of mermaids (metriorhynchoids) are an incredibly old lineage that despite their appearance probably diverged before even many of the land crocs we see in the Cretaceous. So the fact that it so closely matches our idea of a crocodile in shape is largely evolved independently. An additional fun fact, Guimarota is said to preserve the largest Machimosaurus fossils (tho very incomplete). Some old papers claim them to be 9 meters long, but more recent studies have shown that they were probably shorter and just had a stupidly oversized head.

The small guys in front of it are Goniopholis, which look even more superficially croc-like and, to be fair, are also way closer to modern crocs than Machimosaurus. Goniopholids were pretty common during the Jurassic, tho they began to loose influence during the Cretaceous. This species in particular, Goniopholis baryglyphaeus, grew to around 2 meters in length and is actually the oldest member of its group in Europe, which would go on to give rise to Ophiussasuchus which I talked about a few weeks back.

And then we have this little guy, Knoetschkesuchus guimarotae, an atoposaurid that was originally described under the name Theriosuchus. Atoposaurids were pretty small animals with higher skulls, slender limbs and probably terrestrial lifestyles. But believe it or not, this lanky little land croc may have been more closely related to real crocodiles than either of the other two pseudosuchians in the piece, certainly closer than Machimosaurus and, if recent studies are right, closer than Goniopholis as well.

Result from the Guimarota #paleostream.

This locality has done much to further our understanding of Jurassic mammals.

And some details

#machimosaurus#teleosauridae#thalattosuchia#goniopholis#goniopholidae#knoetschkesuchus#atoposauridae#pseudosuchia#croc#prehistory#palaeoblr

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love it when scientific papers discuss some unclear choices or statements from older literature and just go

"yeah whatever the fuck that meant idk"

it's just so casual that I can't help but crack a smile

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally made some progress on Wikipedia projects I've been sitting on for a bit.

After months in my sandbox I finished and published Basiloterus, an early whale from Pakistan

I managed to update Cryptogyps, an Australian vulture, using a 2023 paper

and with the same paper I also updated Dynatoaetus (its says a lot about extinct bird Wikipedia that nobody else could be arsed to add the newly described second species to the page)

12 notes

·

View notes