Text

The Piper of Loos by JF Derry

I was a typical prepubescent boy: Commando comics, stenn gun sticks, fir cone grenades. Incongruously violent games for kids; Bang! Bang! Neeeooow! Kabooosh! There was no honour or glory in our play, no honorable mentions in dispatches, no medal ceremonies, no weeping widows. Just brutal annihilation.

Lie down! You’re dead! I got you. No you didn’t!

At secondary school, this interest manifested itself as a not well-received piece about the Crimean War, particularly the Charge of the Light Brigade. The teacher had expected a work of fiction but, being enamored by the romance and daring-do of it all, I had written a precise factual account, despite clear instruction to the contrary.

Despite an interest in the Crimea, and a concurrent knowledge of the Victoria Cross, it wasn’t until adulthood that a link was forged, finding out that these medals were first manufactured from the Russian artillery captured at Sevastopol and other Crimean battles, (and then from captured Chinese guns subsequent to the end of the First World War).

The next parallel with the honour came with a fascination of the Zulu War and Rorke’s Drift in particular. It’s a remote location a day’s drive from the place I was working in the southern Drakensberg mountains of South Africa in the mid-90s, but it was worth every bone-crunching pothole and sun-baked mile travelled to see what still holds the record for the place where the most Victoria Crosses have ever been won in a single action by one regiment.

From my enduring fascination in this highest military honour, the mature picture I was building about warfare was a very different one to my juvenile play: selfless courage in the face of adversity while surrounded by horror as your comrades are dismembered, and coming to terms with the likelihood of your own death. Violent emotions represented in this one medal. More than most: for the first time, all men were treated equal; valour holds no rank. Their value is thus priceless, despite which you can’t help think of all those ex-servicemen who have had to sell their decorations in order to supplement their pension, to be warm, to eat. The honour of a nation pawned because that nation fails to support its elders and heroes.

And most heroic must be those soldiers who don’t fight, but provide support in combat: medical corp, chaplains, buglers, pipers. Usually unarmed and risking being under fire only to help others, these men are valiant beyond comprehension. Indeed, although bagpipes have likely always accompanied the Scots into battle, the archetypal symbolism of post-Union Scottish military history, from the Jacobite uprising to Waterloo and onwards, every major Campaign involving Scottish battalions, and Hollywood depiction of Scottish soldiery, has included the obligatory piper, often accompanied by some ill-fated drummer boy destined to fall in the line of duty. The only thing possible is to recognise their valour and honour their names, regardless of rank. And that is where the Victoria Cross plays its part.

Piper George Findlater, “The Piper of Dargai”, of the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders won his Victoria Cross at Dargai Heights in October 1897 for continuing to play “The Haughs o’ Cromdale’” under heavy fire even though he had been shot through both feet. Enlisting in the 9th Battalion of The Gordon Highlanders at the commencement of the First World War, he was invalided home from Loos in September 1915.

Another was William Millin, “Piper Bill”, personal piper to Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, commander of 1st Special Service Brigade, who played "Hielan' Laddie" and "The Road to the Isles" as his comrades fell around him on Sword Beach on D-Day in June 1944. German snipers later reported that they did not shoot him because they thought he was crazy.

However, probably the most famous piper to receive the Victoria Cross is Daniel Laidlaw, “The Piper of Loos”. The first day of engagement, the 25th September 1915, was a disorganised mess: the wrong gas cylinder keys had been sent, and what gas could be released before the British infantry attacked blew into their own faces on the changeable light south-westerly wind, exacerbated by the downdraft produced by heavy german shelling. Poorly designed gas masks were discarded as a hindrance and men were overcome by the Red Star chlorine smog gathering in the trench bottoms, exactly where the men were cowering for cover. Seeing the distress and destroyed morale, the CO implored, "For God's sake, Laidlaw, pipe them together!" Laidlaw recounted:

“On Saturday morning we got orders to raid the German trenches. At 6.30 the bugles sounded the advance and I got over the parapet with Lieutenant Young. I at once got the pipes going and the laddies gave a cheer as they started off for the enemy's lines. As soon as they showed themselves over the trench top they began to fall fast, but they never wavered, but dashed straight on as I played the old air they all knew 'Blue Bonnets over the Border'. I ran forward with them piping for all I knew, and just as we were getting near the German lines I was wounded by shrapnel in the left ankle and leg. I was too excited to feel the pain just then, but scrambled along as best I could. I changed my tune to 'The Standard on the Braes o'Mar', a grand tune for charging on. I kept on piping and piping and hobbling after the laddies until I could go no farther, and then seeing that the boys had won the position I began to get back as best I could to our own trenches.”

The shell that wounded Laidlaw had exploded only a few yards distance from him, sending up a section of barbed-wire entanglements previously cleared by his charging comrades. The wire cut off the heel of his boot and a strand lodged in his foot. The same shell blast killed Lieutenant Young.

Laidlaw was now hindered from following his troops, but continued until forced, from loss of blood, to kneel and then become prostrate, never ceasing his piping all the while. "You see," he said later, "I was only doing my duty.”

“Duty” seems to say it all; it is the calling that supercedes common sense, the motivation for heroism. Duty! Such a modest word. For King and Country! Sentiment almost inconsequential in our modern society obsessed with individual success and the epistemics of constant self-evaluation. To whom do we pay our duty today? Whereas, even the the last British soldier who died in action during WWI is an honorable death because his sacrifice was dutiful, “Ellison, G.E., Private, 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers ... was unhappily killed only an hour and a half hour before the Armistice came into force ... The path of duty was the way to glory”.

If Nelson’s flags at Trafalgar ordered that, "England expects that every man will do his duty", then the skirl of Laidlaw’s pipes strengthened similar resolve from his Scottish ranks, and the lyrics to “The Standard On The Braes Of Mar” that Laidlaw chose are most apt,

Our prince has made a noble vow,

To free his country fairly,

Then wha would be a traitor now,

To ane we lo'e sae dearly,

We'll go, we'll go and seek the foe,

By land or sea, wheree'er they be,

Then man to man, and in the van,

We'll win or die for Charlie.

It was a very different world a 100 years ago. All that was needed by Daniel Laidlaw and his brothers in arms to imperil their lives was the unquestioned duty to the liege, and divine guidance, epitomised by the battalion’s mottos: In Veritate Religionis Confido (“I put my trust in the truth of religion”) and Nisi Dominus Frustra (“Without the Lord, everything is in vain”). Loyalty was unquestionable, but also crucial was having God on your side.

And an unwavering belief in those central tenets was gloriously rewarded with decoration. But ulterior motives existed; heroes were needed back home as much as on the Front, as propaganda to reassure the public that the nations’ sacrifices were worthwhile. It is perhaps then no coincidence that Laidlaw was among 17 recipients of the Victoria Cross at Loos. This was one of the first engagements to receive large losses of volunteering soldiers, set up as Kitchener’s Army, to supplement the fast dwindling regular troops. Suddenly, the war would have felt very real back home.

Laidlaw had re-enlisted at the start of the War, having seen action on the Indian Frontier some 17 years earlier. This made him one the most experienced, and at 40 years of age, one the oldest in his ranks. This contrasts starkly with the tragedy that often evokes most sentiment about the massive loss of life in those trenches: the stark youth of the soldiers that did die. Of the 210 fatalities to the battalion on that one day, the casualty records (kindly provided to me by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) hold the ages for only 91, ages ranging from 17 to 53, with an average age of 26 (a loathsome coincidence for this project).

When considering this task for 26 Treasures, it became increasingly obvious that a modern perspective would not be able to do justice to these men, their sense of place, their shared camaraderie. This is what the Piper of Loos represents: a lone piper gathering the genuine might of a whole battalion, and hurling it at the enemy. Advance! Side-by-side. Hold the line! But no words, especially so few as 62, could capture that obligation to duty; I am no Wilfred Owen or Siegfried Sassoon to draw from first hand witness, nor do I have the word-count and turn of phrase available to Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and so do not have a line like, “Into the valley of Death / Rode the six hundred”. Anything similar, attempted from a modern perspective, could form only a trite narrative.

Hence my solution, the symbolic use of the surnames of the men who fell on that day, when Daniel Laidlaw earned his Victoria Cross, as many as I could use within the rules and word limit, to form a different, altogether too familiar cross. I only feel guilty that I had to omit so many.

There is further poignancy here: there remains only a single veteran of the great war Florence Beatrice Green (née Patterson, born 19 February 1901), of the Women's Royal Air Force. The significance? Simply that, with the passing of witness, a society without living history has a greater responsibility to keep, protect, curate and learn from its past. Without reliance on firsthand accounts, reliability of record and memories in museums are all we have.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Can Rebuild You: The Bionic Hand by Lucy Harland

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.

(Douglas Adams)

Deadline-crashing habits from time served in the media die hard so here I am on the morning of 28 July with various false starts, sitting on the western-most edge of the Isle of Lewis trying to think about a bionic hand lying in a museum several hundred miles away.

Outside, long strips of crofting land and fenced-in polytunnels reflect the ages-old determination to make a living here in the face of wind and weather. Inside it’s all Apple Macs and the whirring of the washing machine.

My 10 year old likes those conversations that go, “Say there’s a rhino and an elephant in a fight, who you think would win?”. Nature v people in a fight round here? I know who I’m backing.

My object signifies the battle between technology and arbitrary events, science vs nature. A bionic hand to replace one that was lost or never there.

It’s impossible to know what it’s like to live without a hand or to live with one like this. I’ve spent months with my writing hand in a sling (I have a shoulder that doesn’t understand the basic principle of a ball and socket joint - i.e. that the ball needs to stay inside the socket ...) but there’s no way I can understand what a bionic hand might mean to its owner. What can it be like to watch that hand respond to the signals sent by your brain for the first time?

I haven’t been to see my object. Quite deliberately. I’m an adopted Glaswegian not an islander so it would be possible. I know where the hand is, I just don’t want my mind to be too cluttered with my museum baggage. In my real life I operate on the other side of the museum’s green baize door ... One of the things that I do is to help museums write labels. I have spent hours of my life poking through the recesses of other people’s curatorial knowledge - knowledge that they have crafted into talks, conference papers, lovingly-researched doctoral theses - and then synthesising it into 30-word object labels (and definitely no more than 30 - I am the word count police ... ). Debating what can and can’t be said. What tone of voice should we use? Are ‘we’ the museum and ‘you’ the visitor? Are we sufficiently chatty? Help, are we sounding too patronising? Do we share our doubts about provenance or do we ignore what we don’t know and maintain our Victorian forefathers’ (and they were fathers, and mostly bearded ones at that ...) voice of certainty? How do we make a flat iron tell a story?

It’s my bread and butter to have conversations about how to interpret things in museums. We would start by discussing the context of the gallery or display, and then the specific interpretation aims of this section and object. Perhaps we would decide to talk about the triumph of technology over nature or the story of bionics in Scotland or to simply use the words of someone who owns a hand like this as the best way of representing the personal meaning of this object?

But I’m trying to forget the day job for a few moments.

For me, what’s really interesting about this object is that points to the future. And it’s been chosen to be in the museum for precisely that reason. Unlike the other objects in the 26 Treasures, this has no historical resonance yet. A museum object without a past. It’s been chosen to show the future something about contemporary life. It’s part of a conscious choice about how to represent the present. I’ve collected things like this for museums. I have taken part in shaping that representation. But it can only ever be partial and totally subjective and we certainly can’t control what the future will think of our choices ... So that’s what I will write about. The one object in 26 Treasures that has no history but is in the museum to become part of history.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tartan Tale by Kate Tough

Learning which object I’d been assigned (Ross Tartan Suit), I was delighted. I had no problem with it. Not at that point.

OK, who among us didn’t look down the list of 26 objects to see what everyone else had ‘got’? And who didn’t wonder what it would have been like to have been paired with something else, something more immediately glamorous or dangerous: the Lewis Chessmen, miniature coffins, a bionic hand?

I loved my object, because it was mine; not naive enough to think I’d bagged a coveted one (confirmed by an email, saying, ‘Glad I didn’t get the tartan suit!’).

I understood why. We laugh at tartan; can’t take it seriously. The White Heather Club. The carpets.

What instantly recognisable symbol has this nation, of its identity? Tartan. Is there another country which so derides and shamedly dissociates from the thing it promotes, globally, as its badge? And would punch any non-Scot for mocking?

The rare citizen wearing tartan day-to-day is met with incredulity, hilarity. Yet it has evolved into the uniform for men at weddings.

Our struggle to be proud of ourselves is mirrored in our love-hate with tartan. Our slight self-embarrassment, which hides behind our passion, our social levelling, our teary sentimentality and our brilliant Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment contributions. Are we a knowledge economy or a signing-on underclass? Self-determined or occupied dependents?

Early signs that big themes lay in wait, that this object may render me wordless, were crowded out by elation. I had a photograph: a back view of a suit that stopped time as I stared at it. And I had potential family connections. The suit is Ross tartan. The historic clan seat is Balnagown Castle – a few miles from where my paternal ancestors hail. We had salmon fishing rights near Tain. Did the owner of this suit eat fish caught by my great, great grand-someone? The connection seemed uncanny; this was meant to be my object. I would visit Ross-shire! I would write the piece there!

Oh that heady time of uninformed enthusiasm for the suit. I remember it fondly.

It buoyed my journey to Edinburgh, dispelled any trepidation in steep, blind closes to the Royal Mile.

The enthusiasm of the curator, David Forsyth, matched my own. His knowledge far exceeded. A ranging, exhilarating conversation ensued about Scots and Scotland. Scots as aboriginals, as Highland warriors. The Highland clearances (more people left in the 20th century than the 19th – did you know that? We’re way up the emigration league table with Ireland and Norway.)

David left me at a large table with a thin A4 folder; the ‘object file’. It took two hours to feel done with less than a dozen sheets.

If tartan had been my first problem related to the object, its provenance became my second. And that, dear reader, shall remain the greatest story never told. I was privy to the information in relation to how the suit came to be donated to the NMS. For you, I can distil some facts:

The suit was made for Alexander Ross, a medical student, most likely for the ceremonials surrounding the visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822.

It was given by Dr. Ross to his wife Kitty’s younger brother, Donald Munro Ross (same surname being a coincidence, I think).

The suit was taken to Australia when D.M. Ross emigrated in1864, aged 34.

He won the Best Dressed Highlander rosette at the Melbourne Fayre, more than once.

The suit passed down the family, until being donated by The Rev. and Mrs. Donald Dufty, Australia, for the opening of NMS in 1998.

The act of donation was inspired by repatriation of aboriginal remains by Scottish institutions.

Geography and dates had ruled out any connection between the wearers of this suit and my forebears.

What I was invaded by, what awakened my writerly urge, was what I found in the object file: the correspondence, the newspaper clippings. Its wearers and keepers; how they changed the suit and the suit changed them (nothing in any way ‘bad’, just regular family myth-making). But I couldn’t touch that. Because as ripe and tantalising as it was, it was not mine to tell. The owners donated their suit, not their family, for the public to stare at.

The significance of the suit as a gift to the people of Scotland brought the weight of the tartan fabric to bear again. In what way was it Scottish? How authentic was this suit, made for a street party? Who wears tartan? When? How relevant is it? Does it mean more to the diaspora than the born-and-bred?

But I couldn’t resolve the politics of tartan in 62 words. And I’d take no avenue that could be construed, however unintentionally, as disrespectful to the donors of the object. I wouldn’t examine the ‘more Scottish than the Scots’ angle, and how the diaspora feels about Scotland. I would not set out to disabuse them of their views. I don’t even know my own.

This object was not a fossil whose relatives were long dead. Or a piece of industrial equipment, which never had any. This object was gifted to Scotland by a generous family who live (albeit very far away). I wouldn’t be ungracious. It’s not what Scots are known for.

This tartan coatee had become a straight jacket. What words were left for me?

Well, I had the fact that when I first saw its photograph I loved it. Utterly, almost sexually, it hooked me. The fresh-blood red of it, the pleat and puff of it. The curl and drape of it. The red. The luminous red. It hung like there was a man still wearing it. If you stand a man’s clothes up, I thought, he can’t leave. Take down this kilt and coatee. Let him rest.

With 15 minutes till closing time, I scurried out from ‘behind the scenes at the museum’ and back in by the public entrance, to the fourth floor, expecting to round a corner and be met with the majesty of it, the statuesque, solitary spot-lit glory of it. I was almost past it before I realised I was passing it.

That was it?

Dull wool, dully lit, front view. Nothing to see here, folks, move along. In a busy display case, one thing among many. Wallpapering a corridor. I wanted to love this object, but it didn’t want to be loved. Scotland and the Scots came to mind, again. We don’t make it easy for people.

I couldn’t write a paen to the object itself, because what caught me was its photograph. The fresh-blood-and-mud pleats, in white studio light. I’d have to write about what visitors to the museum would see.

Let me look more closely, I thought. Let me study this. Let me forget its reinvention over the years (which I cannot mention) and talk only of what is there. The process of tartan-making, a 62 word phonic poem of suggested meaning: plaid and thread, warp and weft, twill and weave, sett and selvedge.

It was not enough. OK then, a tribute, to the dead animal that is folded over on itself, into a sporran, face framed by useless legs. Claws for tassles. An animal which, in the documentation, was never referred to as anything other than ‘the sporran’. (Confirming why I could not touch the ‘story’ of the suit in my 62 words. I couldn’t treat the suit’s wearers and donors like we have treated this creature – as irrelevant and not there. The family is standing beside it every time I look.)

How could I talk about this? How could I haul up its treasure; love it once more?

The only angle to come from was the one chosen for me; the curator’s –

the position in the Australia and New Zealand case, in the Industry and Empire section. I would talk about emigration. The Scots who go. This was not a new phenomenon to explore; nor unique to this object. This phenomenon was all I had.

When I had my angle, the 62 words came. I found out, first hand, that you can’t write well about what you have just learned (the history of tartan, Walter Scott and George IV). You can only write about what you already ‘know’. And I know the push of this country. And I know the pull.

#Scottish history#nms#26Treasures#Kate Tough#Tartan#Scottish Design#Ross#Balnagown Castle#Highland Clearances#Emigration#Walter Scott#George IV

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rat-a-tat-tat by Christine Finn

Mary Barbour's rattle sounded out to me long before I ever saw it. I was delighted to be paired with such a fascinating object, especially one so much outside my ken; I knew nothing about Scotland during the First World War. But I should have done. Going to see it meant I could pursue another lead, possibly one to draw on, which had rattled away in the cupboard of family tree stories for years. I made the journey north, travelling from the end-most corner of south-east England. But not immediately to the fifth floor gallery at the National Museum, but heading west, past Glasgow, to the tip of Kintyre. Around the time, 1915, that Mary Barbour was leading her army of women on the streets of Govan, my Scottish grandfather was most likely also in Glasgow, where he was working in the Clyde shipyard. A few years later, Charles Finn travelled where I had come from, Deal in Kent, to work as a sinker for the new coalfield in the 1920s. He stayed a miner all his life. My father, and his six siblings, were born in Deal but, as far as I knew, none had visited Campeltown where Grandpa Finn came from. He was a child of a fishing family, and his parents, the story was told, had a fishing fleet which plied between Ardglass, in County Down, and Campeltown. Children were born in Ireland or Scotland, depending on where the herring were at the time. Last year I went to Northern Ireland determined to flesh out the story from very bare bones, but more than 30 years of journalism did not prepare me for the slipperiness of memory, and holes in hand-down family yarns. I could find nothing but conjecture about my great-grandparents, although dredged up plenty on the breeding patterns of herring.

But back to Campeltown, in my heart for years, and especially with grandparents and parents long gone. The tale told me by an aunt was that Grandpa Finn was related to Cecil Finn, a Scottish fishing luminary and decorated for his work over decades. Through him, I thought, I'd get the full story. Except, when I met him, nothing was resolved. Obliging as he was with family history, Cecil hadn't heard of any relative called Charles Finn, and we couldn't find any other names of likely overlap. If my Finn line came across the sea from Ardglass, where it went after that I simply couldn't fathom. But this unexpectedly dead end didn't diminish the rattle pilgrimage. If anything, the thrum of the poem was rattling about in my mind from the first train north, through the several sea journeys, and numerous buses. I took a random route to Edinburgh after Kintyre ... via Islay and Jura, trying to gather words. By the time I reached the Museum, I had quite a clear idea about how I wanted to write the poem. Mute in its case, and ambered with age, the object did not disappoint. Even with a film loop playing next to it, I swear I could hear the rattety sound rolling out. If his Clyde shipyard tales are not another red herring, I am left wondering: did Grandpa Finn hear it too?

0 notes

Text

"Gneiss to meet you" by Janette Currie

My object is the Lewisian Gneiss [rhymes with ‘nice’]. It isn’t a personal object - didn’t belong to someone famous or infamous. What can be said about a lump of grey rock? What can you even think about a rock? I’m a researcher at heart, so, being paired with an object and subject-matter completely outside my field, I scurried in search of the undiscovered country: geology.

Both in the NMS bookshop and online I delved into scientific information which was often illustrated with stunning photographs of rugged Scottish landscape and scenery – the structure below and the towering mountain peaks. And of course, I read about James Hutton, the important Scottish Enlightenment thinker, friend to Robert Burns and founder of modern geology.

I traipsed off with teenager to meet my gneiss. He’s grey but not dull [the gneiss, not the teenager]. He shimmers under the exhibition lights in the ‘Beginnings’ Gallery. We read about the long process that formed metamorphic rock and watched the video which opens with the evocative words translated from Derik Thomson’s Gaelic poem called ‘Strong Foundations’. But most of all we looked at [and touched and stroked] the Lewisian gneiss.

Gneiss is ancient rock. Over millions of years, or ‘super-eons’ it stretched and split from the Earth’s crust and found its way across the globe to Norway and North America as well as places like Loch Finbay in the Outer Hebrides. Sometimes called ‘the old boy’ and ‘the haunted wing of geology’, it’s Scotland’s basement. ‘Haunted’? Criss-crossed with stripes of white and pink, sparkling within the folds are ghostly shades of granite and ancient rock deposits.

I dug a word bank from out of the dry statistics– chipped away the facts to discover a story [forgive the geology puns].

undulate, meld, shimmer, spark, steam, fold, cleave, building blocks,

South Pole, Cape Wrath, volcanic, ice-laden

Thinking of the rock as a person, ‘the old boy’, combined with these deliciously descriptive words, an image emerged, not of ‘the old boy’, but of his younger self. And a story began to emerge of how his movements across the globe created the dramatic Scottish landscape we now have. It’s a story about a journey – a young man’s quest northwards from the ‘ice-laden seas’ at the South Pole.

Using ‘found’ words I decided that the epic, the oldest written poetic form, was the best structure for my poem about the oldest European rock. It isn’t a story of conquest, although, to be frank, it takes a lot of force and steam and volcanic pressure to create gneiss. Nor did I want to write a ballad romance of a swooning female waiting for the handsome southerner to rescue her. What I hope to represent is a 21st Century retelling of the story before the history of Scotland where the union of equals in passionate embrace shapes the landscape.

So - I’ve got the beginnings of my poem about Scotland’s beginnings

…‘From the South he came.’

All of which goes to show that you can write a lot about a rock, once you get to know him.

Acknowledgements

It’s a myth to think that writing is a solitary occupation. I’ve found staff at NMS, friends and family only to happy to put me right on science and wonky thinking. So I’d like to thank them for letting me bounce ideas around and for their patience and forbearance as the poem takes shape. Thank you – David Currie; Peter Davidson [Curator, NMS]; Mardi Stewart and Jane Stewart. My poem grows out of a conversation with Nicky Melville after his presentation on conceptual and found poetry at the Write Now Conference, University of Strathclyde, June 2011.

0 notes

Text

Saint Fillian's Magic by Linda Cracknell

I love the kind of writing commission which delivers a subject without any choice. Anxiety nags at me initially but then I discover there’s something about it I’ve always wanted to write about, even if I didn’t realise it.

When I got matched with the ‘Coigrich’ – the 16th century silver gilt case or 'shrine' which represents the handle of Saint Fillan’s Crozier, and became one of his holy relics -- I had more of a starting point than I’d expected. I live in Perthshire, just a little east of Strathfillan, where between Tyndrum and Killin, Saint Fillan walked into his missionary territory in the eighth or ninth century, built a chapel and organised a number of miracles, not least the harnessing of a wolf to help oxen pull his plough. Robert the Bruce later established a Priory near to the chapel.

Those early Celtic saints intrigue me. I’m fascinated by their earthy-seeming beliefs, humble ways of life, their journeys on foot, and their miracles, so close in my mind to acts of magic.

I like my writing projects grounded in places, and physical activity – usually walking – helps me make the job visceral, sparking up words and images. So in preparation for my 62 words, and to get familiar with Saint Fillan, it seemed only natural to put on my walking boots for a stroll between Tyndrum and Crianlarich.

In a broad valley between some of Perthshire’s blunt-topped, high hills, the ruins of the Priory dedicated to Saint Fillan shelter in a copse of trees right on the route of the West Highland Way. The nearby graveyard, prominent on the mound next to Kirkton Farm, dates back to the eighth century. More remarkable to me though, is the holy pool about a mile away, associated with Fillan’s early life here and his healing powers. For many centuries a monthly ritual, its date dictated by the phase of the moon, drew gatherings of mentally ill people. The pool, naturally divided in two by topography, maintained a discreet segregation of the sexes. After immersion, the ill were taken to the Priory and clamped into some kind of device overnight, covered in hay, and left with Saint Fillan’s Bell (another holy relic) on their heads. If they weren't cured by the morning, this ritual might have to be repeated. Despite the shimmering heat on the day of my walk, I shivered a little looking at the pool’s glassy dark surface, and declined a dip myself.

As with the lasting power of the holy pool, belief in the Coigrich seems to have grown over generations, surviving the Reformation and other moves against superstition. So great was its reputation that even when the relic’s keeper of the time, Archibald Dewar, emigrated to Canada in the 19th century and took it with him, Canadian highlanders still sought it out, following the tradition that waters touching it could heal cattle.

Such stories have had me scouting for words like foot rot, lumpy jaw, wooden tongue -- the wonderful lyricism of cattle ailments. And for words like chrismatory, affusion, and thirdendeal, archaic words associated with the holding or scattering of liquid.

The Coigrich has further intriguing qualities, not least that the shrine encases the curved shape of, and even includes some bronze plates from the 11th century crozier head discovered inside it when it was recovered from Canada. A crystal incorporated into the design may even date back to the time of Fillan. The shrine itself, through its association with the crozier head, with miracles, with famous people, with success in battles, seems to have amalgamated greater and greater holy power, outshining its simpler and older lodger.

‘Coigrich’ comes from a Gaelic word for stranger or foreigner, attributed to it because as a relic it was so well-travelled. The family assigned to be the relic’s custodians became known by another word with a similar meaning, Deoradh, giving rise through the generations to the Perthshire surname, Dewar. And the word ’crozier’ originally referred to the bearer of the Bishop’s staff, not to the staff itself.

These are curious minglings and transformations taking place over centuries. People merge with things; things become spoken of as people; cases adopt their occupants’ power..! The 62 words I choose will have to work their magic well to embody this thicketed enchantment of stories and language.

#Coigrich#shrine#St Fillian#Linda Cracknell#NMS#26Treasures#Archaeology#Christianity#miracles#Celtic church#crozier#Dewar

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

DIG OUT YOUR DANCING SHOES by Collette Davis

I was meant to go to Orkney today but a wise Neolithic archeologist persuaded me otherwise. I made the decision to venture North a couple of weeks ago after speaking to Ian Begg, who I came across in June when dipping my toe into the 26 Treasures research waters. Ian is a retired architect who just so happens to have a specific interest in the carved stone balls of Scotland. He suggested I write my piece on the Isle of Papa Westray, where you can find the oldest house in Northern Europe. But then I met Alison Sheridan and we decided that my time would be better spent in the libraries of the National Museum.

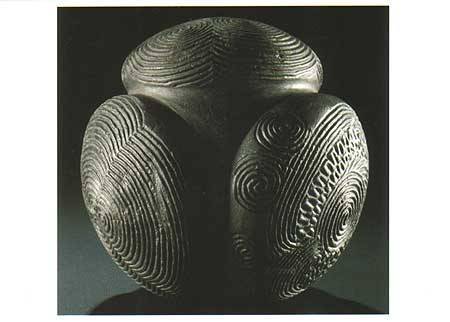

Short for time, Alison marched me down to the prehistoric underworld of the museum where the Towie Ball and I were finally introduced. I was surprised by the rush of excitement that thundered through my caffeine riddled veins when I laid my eyes upon it. “Oh my god, it’s tiny!” In my mind, this 3000 year-old carved stone ball was like those big bad spheres from World’s Strongest Man. It is not. It’s a wee thing that could easily fit in the palm of your hand, if only I could touch it. The hairs stood on end, from my ankles to my ears, as I found myself in the presence of greatness.

The Towie Ball is classified as a ‘Prestige Object’ and I’m starting to feel quite smug that my treasure is so very prestige. Intricate spirals and concentric circles have been painstakingly etched into the glacial Aberdeenshire stone. It sits serene next to a vicious spiked stone ball and what looks like an antiquated grenade. They are surrounded by Jadeite axes and maceheads carved from flint and antlers. But this is no weapon.

The spirals are the key to unlocking the secret of the enigmatic Towie Stone, whose “use is wholly unknown”. The pattern can be found on the kerbs of the passage tombs in Newgrange, Ireland. They appear on the lintels of ceremonial monuments in Orkney. And you can find them on maceheads discovered in Norfolk. The spiral is thought to be a symbol of power and seems to be associated with life, death and the supernatural. If you had one of these in your back pocket, you were probably a pretty big deal back in the day.

Before I came to Edinburgh to meet Alison and The Towie Stone I thought I might apply the Structuralist school of thought to my object. Intent on understanding its use and purpose, many an enthusiast and archeologist has sought to impose their reading upon it. These Neolithic mysteries are blank texts that are open to interpretation. A signifier with no signified. But all of this seems pretty insignificant and poncy when you learn that a carved stone ball was found in the grave of a Viking. So I think I’ll dance inside spirals of power instead.

#Towie Ball#NMS#26Treasures#Collette Davis#carving#sculpture#neolithic#bronze age#greenstone#spirals#Scottish heritage

1 note

·

View note

Text

Treasure on Arthur's Seat by Ronnie Mackintosh

On the wall above my desk is a copy of Kay‟s Plan of Edinburgh, 1836. Beneath it; a stack of print-outs, notes and copies of contemporaneous paintings. Researching my treasure, the mysterious Arthur‟s Seat miniature coffins and their unknowable origins, has become something of a mild obsession.

I‟m a screenwriter, and with my allocated 62 words, I intend to create a scene as my 26Treasures submission. At 62 words, it‟ll be little more than a moment in the life (or lives) that end up on the page. Regardless, this imagined fragment of time must be as authentic as possible.

First of all, what do we know about the coffins?

Discovered on a summers day in June or July (accounts differ), 1836, by five boys while out hunting for rabbits on the slopes of Arthur‟s Seat, in what was described as: „an aperture about twelve inches square‟, further described in the Scotsman: 'The mouth of this little cave was closed by three thin pieces of slate-stone, rudely cut at the upper ends into a conical form, and so placed as to protect the interior from the effects of the weather.’

And when the boys removed the slate pieces, seventeen miniature coffins, laid out in two layers of eight with a single coffin on top, were exposed, each around four inches long, fixed with a lid and neatly adorned with small pieces of shaped tin.

An historic find indeed, although, according to another report of the day, in The London Times, dated July 20th, 1836, its significance was lost on the youngsters; “a number were destroyed by the boys pelting them at each other as unmeaning and contemptible trifles.”

Some coffins were in a bad state of decay and did not survive, but those that did were later recovered, according to some records by the boy‟s schoolmaster, who opened them to discover that each contained a small wooden figure, dressed in a sewn cloth garment.

What is known of the chain of ownership from then is unremarkable, until their donation to the National Museum of Scotland in 1901.

Such is the context in which the miniature coffins were discovered. But of course, the interest lies not in their discovery but in their creation and purpose.

A scientific study of the coffins and their occupants, published in 1994, gave new insights into the mystery. Those that attracted me, bearing in mind my intention, included the suggestion that the uniformity of the rough cut figures, the markings on them and the remains of paint implies that at one time they may have been part of a set of "

toy soldiers‟. This may be supported by the fact that several figures had arms removed to allow them to fit into the coffins, suggesting that they had another prior purpose and had not been created for burial in the coffins. The examination of the textiles and threads suggest a date of interment no earlier than 1830, and the tin from which the coffin decorations are made is similar to the sort used in shoe buckles of the time, but while the tin-work suggests a degree of proficiency, the coffins were not shaped with carpentry tools or developed with any significant woodworking skill.

The widely held belief is that the figures are connected to the infamous Burke and Hare murders of 1827/1828. While the chronology and body count fit nicely with this theory, I find it contradictory that of the sixteen Burke and Hare victims (another died of natural causes) twelve were women. Yet all of the wooden figures are dressed in representations of male clothing, where dresses would surely have been easier to fashion.

Other general matters that struck me, include the fact that in 1836, Edinburgh was going through an historic rebirth with the stunning New Town having been completed the previous year.

Holyrood Palace, which sits at the base of Arthur‟s Seat, had also just undergone significant external works, and paintings of the time show smart, red coated soldiers on the parade square.

And yet, only three years before, the city had been declared bankrupt, with the blame being placed on the development of Leith Docks. The same docks from which those who wanted to and could afford it, were emigrating to a better life, on ships such as that which records show departed from Leith and arrived at New York on 29th May, 1835.

My task is to create that brief, imagined moment, and with the help of the foregoing information, characters and circumstances can now be imagined.

And I think there‟s enough clues in this piece to suggest where I might be going with this.

#Ronnie Mackintosh#Arthur's seat coffins#scottish screen#BAFTA#NMS#26Treasures#grave practices#Edinburgh#coffins#grave goods#Scottish tales

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collared - and another thing! by Vivien Jones

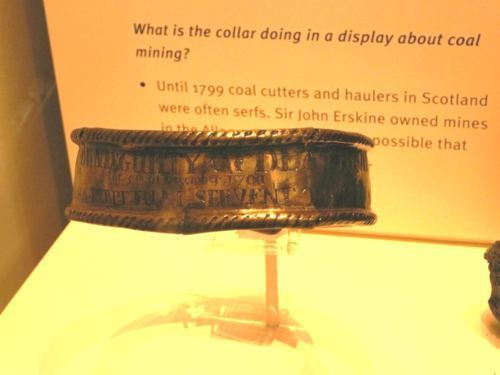

I'm eight years old again. Sat in the car with a butterfly stomach about to go to THE MUSEUM where I know wonderful things await me. I'm so pleased this excitement has stayed with me. I'm 63 and I'm going to Edinburgh 93 miles away to The National Museum of Scotland to see my treasure in the flesh - perhaps I should say in the metal. The drive amongst the Border Hills is always spectacular and today proves no exception, even going most of the way behind a lorry load of tractors doesn't spoil the drive - rather it allows time to mark the sudden purple blaze on the hillsides and the swollen burns after last week's rain. And time to speculate on my treasure - an 18th century serf's collar.

Serf. There's a word, a concept, to ponder on. In my mind 'serfs' were the peasants of old Russia and Eastern Europe. 'Serfs' were a feature of feudal society in the Middle Ages. The word causes discomfort in my conscience, considering the existence of serfs in 18th century Scotland, co-existing with the ideas of Locke and Hume, with the intellectual giants of the Enlightenment. Serfdom was not abolished in Scotland until 1799. So what story will a serf's collar tell ?

There it is then, in the Trade and Industry section, gleaming like a Celtic circlet, incongruous in a case of primitive hand tools used in mining of the 18th century.

A closer look scrubs out a jewellery definition. At the back a hasp and staple arrangement show its purpose, three slots to adjust the grip round the neck, a reusable token denoting one person owned by another. I lean forward, read the legend, already intrigued. A man, Alexander Steuart, convicted of 'theft ' in Perth in 1701, sentenced to hanging commuted to being 'gifted as ane perpetuall servant' to another, Sir John Erskine of Alva, a mine and, apparently, a man owner.

My mind is buzzing What did he steal ? Why was he pardoned ? Why fit the collar when it was standard practice to brand the forehead with ' ane mark the size of a sixpence'* to mark each criminal ? Is there something particular, something personal, about this crime, this criminal, that requires such a humiliating marker ? I lean closer, note the detail of the forging and rolling, the inscription, the decoration. Surely a simple metal collar hammered to a circle on an anvil would have sufficed ? My gaze shifts sideways to the paraphernalia of coal cutting by hand, a shoulder stool to support a man undercutting, a tallow-candle holder, a bottle for water, the diagrams of working conditions for men hacking, women and children hauling, in never-ending, unbearable toil. I imagine one among them, Alexander Steuart, bent to his work, irritated by the unremitting rub of the metal round his neck, considering his interminable future.

The following day comes a package from the museum - with more tantalising information - our serf, a Highlander, would probably not have had the skills to work in the mine, but may have been employed as a surface labourer.

He was one of four judged and sentenced to death that day in Perth by the Commissioners of Justiciary for securing the peace of the Highlands. It seems the prisoners (pennals) were to be returned to the Tolbooth while their 'collars be made and putt upon their necks' before being handed over to their new owners.

Inscribed on this collar is 'Aler.Steuart Found Guilty of Death for Theft at Perth the 5th of December 1701, and gifted by the Justiciars as a Perpetual Servant to Sir Jo. Areskin of Alva.' How long did that work take? Not a common skill, that quality and clarity of lettering.

And perhaps, being a Highlander and it being close to the 1688 Jacobite rebellion, judgements were aimed to humiliate a rebellious people. There could be no greater humiliation for a Highlander with a strong sense of brotherhood than to be owned by another man - a concept that might seem worse than death.

And, what manner of man was 'Sir Jo. Areskin of Alva' ? His name is on the collar - a very firmly inscribed note of name, crime, sentence and status on a collar with decorated rims. That decoration intrigues me - it appears to be hammered into the top and bottom rims of the collar. It serves no purpose other than to attract attention. The dynamic between these men, owner and serf, fascinates me. This is where I feel my creative instincts are drawn.

*His branding ' a mark of the largeness of ane sevenpence or therby'.

#serfdom#scotland#vivien jones#26treasures#collar#archaeology#coal mining#Indentured labour#serf's collar

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Maiden Speaks by James Robertson

‘A beheading machine’ is an accurate definition of the Maiden, Scotland’s own guillotine. Introduced in 1564, it was similar to devices used elsewhere in Europe. Guillotining was more efficient, and more humane, than the previous Scottish practice of removing heads with a sword, which could and often did go grotesquely wrong if the victim moved, or if the executioner’s aim was off or his sword blunt. The beauty of the Maiden was that it left no room for human error. The operator struck the trigger of the machine, releasing the rope securing the blade, and the blade, loaded with 34 kilos of lead and guided by copper-lined grooves down the uprights of the structure, did the rest. I cannot imagine what awful noise that descent made, but it would be the last thing the victim heard. Even if the blade wasn’t that sharp his or her neck would be broken. The National Museum’s information rather brutally explains the enormous lead weight as being ‘the key to punching head from body’. Public execution is, of course, a brutal business.

Before I went to see the Maiden, which stands in the ‘Law and Order’ section of the ‘Kingdom of the Scots’ display, I had a wander round some of the other galleries. In the ‘Scotland Transformed’ exhibition a couple of floors up I found what at first glance looks like an enormously expanded version of the Maiden, built perhaps to decapitate ogres. This is Thomas Newcomen’s 1712 steam engine, actually used to pump water from coalmines in Ayrshire. It therefore represents progress of a kind; but the Maiden was still at work, and was not retired until 1720. By that time it (or ‘she’, as we might refer to her in deference to her name) had removed the heads of more than 120 people. Hanging became the modern way of carrying out capital punishment. As late as 1820, though, the leaders of the Radical Rising had their heads chopped off in Stirling (with an axe) as a warning to other would-be rebels against the state. They, however, were already dead, having been hanged first.

The Maiden was a big-boned lass, ten feet tall and with a heavy oak frame, but she was also portable. When not in use she was dismantled and packed away in storage, then reassembled to perform her grisly task at various locations in Edinburgh, including the Grassmarket, Castlehill and the Mercat Cross. It’s said that she acquired her virginal name because she wasn’t used for a number of years after being built. Maybe this is true, but the French called their beheading machine Madame Guillotine so it could be more about the macabre allure of femmes fatales in popular culture. Women who kill are much rarer than men who kill, and are therefore often regarded with greater horror and hatred.

The man believed to have introduced her to Scotland, James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, also became one of her victims. In 1581 he was found guilty of involvement in the murder of Queen Mary’s husband Darnley back in 1567. Morton was condemned to be hanged but Mary’s son King James VI ordered that the instrument of death should be the Maiden. ‘The King shall lose a guid servant this day,’ Morton said, but if James heard about this it didn’t change his mind.

When I discovered that I was to write 62 words about the Maiden, I thought they should tell something of her side of the story. How might she have reacted on learning that Morton, who had originally commissioned her, was to put his head in her lap? What cruel, kind or ironic words might she have uttered as he was brought before her? She was no longer a maiden by then, of course, but in all her trysts it was never her blood that was shed. Possible words of welcome – of soothing calm, of sexual invitation? – sprang into my mind. The Maiden spoke with a Scots tongue. These words became the first line of a poem. Eleven short lines later, Morton was dead.

James Robertson

#NMS#The Maiden#Guillotine#James Robertson#Law and Order#Capital punishment#Scottish history#James Douglas#26Treasures

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two million tides by Stephen Potts

Modern 26 treasures have a provenance. We know when, where, by whom, for whom, with what, (and, occasionally, at what cost) they were made. We know where they have been, since first they were created. We can trace their history. We can tell their story.

For my treasure – the Cramond Lioness – all these questions remain unanswered and are perhaps unanswerable: a mystery which heightens interest, and allows many alternative stories to suggest themselves.

The undisputed facts are that it was pulled from the mud at the mouth of the River Almond after discovery by the Cramond ferryman, Rab Graham in 1997. It’s almost certainly Roman in origin, and a Roman fort stood at the site around the time of the building of the Antonine Wall some 18 centuries ago.

It’s a massive piece of work, carved from sandstone. A fearsome animal devours a remarkably calm bearded man, who is naked, exposing a muscular torso, and who may have his arms bound. A prisoner then, marked out for death, perhaps in the arena: execution as entertainment. Pour encourages les autres.

But who is he? What was his crime? Why does he go so blithely to his maker? An early Christian, martyred for his belief? A common criminal, glad his tortures are over at last? A rebellious general, convinced his cause will yet prevail?

The sandstone is probably British, and possibly local. Yet apart from Toblerone teeth, the lioness is terrifyingly naturalistic, as if the sculptor had surely seen such beasts close up, in the wild, or in the cages under the Coliseum. So his stone might be local - but sculptor and subject are not. Why did he come to Britain? Why to this, the Northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire? Was he exiled here? To serve a military master, with decorations for his tomb? And was this indeed its purpose, as the snakes curling over the plinth are said to imply?

The story of its discovery bears telling. Although two million tides had ebbed and flooded over its head since Roman days, winter storms in 1996 scoured the concealing and protective silt away, to expose the lioness’ face at low spring tides. Positioned, as it was, below the quayside steps, Mr Graham thought it first a rock which might damage his boat, and then, as its carved nature emerged, a possible garden ornament for his Forth-side lawn. But when he set to digging it out, he soon saw it was something greatly more substantial, and reported his find. Careful excavation, removal, cleaning and preservation followed, until now it crouches, menacing and powerful, in the NMS.

It is remarkable that the building of the Cramond quay did not lead to its earlier discovery, to damage, or to encasement in concrete: but how it came to be there in the first place is to my mind the most interesting question of all. I picture the Picts, exploring the fort after the Romans have finally abandoned it and headed south to begin their long slow implosion of Empire. They pick over the empty buildings for anything of value or utility; but finding little, their anger at the departed occupiers rises. The start to break things, beginning with the small and fragile: but this is not enough to mark liberation or victory, so they look around, they look up, for something bigger, something solid, something symbolic. And seeing this enormous sculpture of cruelty imposed as both punishment and entertainment, they know what they must do. They smash down supporting walls, till the lioness crashes to earth, breaking its plinth. They drag it to the water’s edge; and they hurl it in, where it vanishes from view as completely as Roman rule has vanished from their land.

0 notes

Text

David Manderson: The ‘Instrument of Authority’

It would be me, somehow, that got the Instrument of Authority. Whatever that is. I’m the guy everyone thinks is a cop on holiday: the short hair, the ultra-straight look (though that’s not me at all).

But what is this ‘treasure’ exactly? Something dark, brutal and unpleasant no doubt … A truncheon? A hook on a dungeon wall?

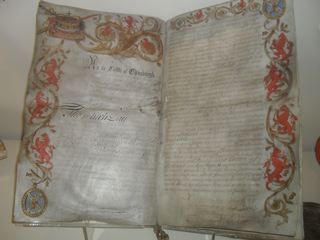

But here’s a surprise. With my treasure comes a picture, and it’s none of the above. It’s not cold and cruel. It’s a document, a crisp piece of parchment with faded coloured ink, red lions rampant down the margins, scratchy signatures at the bottom, and big words that stand out:

At the Castle of Edinburgh …

My research starts on the Net, and with a few guesses, a little ingenuity and some clicks I have all I need. I will go to Edinburgh to see it though. I can’t miss the chance of standing in front of it and taking it in, the reality of it, not just on a screen. Because it really is a treasure I’ve been given, a piece of a story that was lost and found, and lost again and found once more, and has come back as alive today as it was three hundred years ago.

This is the document that the keeper of the Scottish Crown Jewels – or the ‘Honours of Scotland’ as they were known – had drawn up at the Treaty of Union in 1707. He was one William Wilson, and he must have been conscious of the importance of the moment, and his role in it. For it had been decided, and written into the Treaty, that the Honours would stay in Scotland, kept forever in Edinburgh Castle, a marker of all that remained of Scottish independence.

And maybe he was aware too of the trouble in the streets, the cries of rage from the markets and taverns, the unrest at the selling of a nation ‘for English gold’ - or gold of any sort. Maybe he knew that the significance of the jewels was much greater than their value or their symbolic power.

Perhaps he believed, as many others did, that they were the soul of Scotland, something people would sell their lives for. They already had, during Cromwell’s brief but brutal reign, when they had been shielded against overwhelming odds in Dunnottar Castle, and then smuggled out, a frantic, desperate escape, to be buried again in Kinneff Chapel for eight years, until Charles II mounted the throne and Cromwell’s head rested on a pike. Maybe he knew that symbols though they were they stood for something, like the Stone of Scone, that people would remember, and long for again.

The Which Day …

Local poets on that fateful day in 1707 even gave the Honours a voice, sadly lamenting their fate:

The Croun’s last speech 26 March 1707

When lodged in ye castle of Edinr after ye

rising of ye parliament

I royal diadem relinquisht stand

By all my friends and robbed of my land

So left bereft of all I did command …

And they were indeed lost. In fact, the crown, orb and sceptre were to disappear for over a hundred years, forgotten, the cast-off relic of a cast-off nation. And not until a new era had set in, and a young Borders lawyer (who was rapidly becoming a best-selling author and an international publishing sensation), Walter Scott, set out to trace them were they found again. Scott used the Instrument to prove that the Honours were still in the castle – after all, it said they would be there forever, and it was stated again in Article 24 of the Treaty – but rumour had it they’d been taken to London decades before, like everything else of any worth, and melted down. But in the Crown Room of the castle that day in 1818 an ancient chest was opened, a roughly bound bundle drawn out, and there they were, the oldest sovereign ornaments in Britain, still as they were on the day they’d been taken from their rightful place and hidden in darkness. Maybe something like Scotland itself.

The story doesn’t even end there – for the jewels were buried again, in the grounds of Edinburgh Castle during the Second World War. But today they rest on scarlet velvet in the Edinburgh Crown Room, except when they’re dusted down and give a rare journey down the Mile, like they were just the other day for the Queen’s opening of the Holyrood parliament. And the Instrument – loudly, blowsily and show-offily - still protests the right of a nation to protect what it holds most dear.

A country at a cross-roads, trouble in the streets, debates over dependence or independence, a new parliament, no end of pride, and still no gold …

It was so long ago. It couldn’t happen now.

Mind you …

#David Manderson#Act of Union#Scottish Nationalism#Instrument of Authority#NMS#Unionism#Scottish history#Scottish independence#Scottish crown jewels

0 notes

Text

Connecting with the past by Lee Randall

Last weekend I went to the museum to commune with my object, The Darien Chest. Stubbornly refusing to pick up a gallery map, I went the long way around, wandering through room after room of relics, worrying as I so often do at airports and crowded parties, whether I’d recognise my quarry, even though I had a much-referenced picture of the chest stashed in my handbag.

Eventually I found it, looking exactly like itself. A pair of American tourists paced back and forth in front of it, examining it carefully. I approached warily, eavesdropping in the hope of hearing something quirky in their reactions. (At times such as these I keep shtum, fearful that my own still-American vowels will prompt confusion, because that makes me defensive – unbidden, I launch into a laboured explanation about how I actually live here, and Edinburgh’s home. These monologues leave me feeling like a pedantic prat, yet I cannot cure myself of them.)

Seeing them there, I felt a swell of pride: Hey! People are admiring my object! MY object! They were especially interested in the intricate lock, whose mechanism covers the entire underside of the chest’s cover. I circled them, affecting nonchalance but vibrating inside. I read the curator’s label. I looked over and wondered (all right, sneered), “Do you have any idea of this chest’s significance? Do you want me to tell you?” This, despite my own very limited knowledge, because I’d decided to meet the Darien Chest before googling the hell out of it. This, simply because someone decided it was “mine.”

The lock they – and I, and a swarm of blue-blazered schoolboys arriving later – so admired is a marvel of technology and aesthetics. A Heath Robinson affair (or Rube Goldberg, I might have said to the Americans), it’s a montage of swirling strips of iron, which mesh or push past one another to activate the intricate mechanism. They terminate in carved arrows, while tiny, unnecessary flowers cover the heads of bolts or joins. Someone with an eye for beauty took time crafting this object. Someone proud to win the commission for such an important treasure chest. Someone, perhaps, who believed it stood for Scotland’s brave new future, who unlocked his own, smaller casket to retrieve coins to the worth of £5, to invest in the Company of Scotland.

I misbehaved during my visit. During a summer internship at the Cloisters museum, many years back, I learned that there are two mortal sins of museum-going: walking backwards and touching the exhibits. I knew that, and I touched the chest anyway, to understand how cold and hard and enduring it was. Then, making certain no one was looking, I leaned down and inhaled, pulling the stench of iron – so like blood – right into my lungs. I very nearly crawled into the chest. It looked roughly the right size to accommodate someone bent double.

The allure of history has been with me, always. As a kid I wondered about everyone who’d gone before, never speculating forward, about rocket ships or life on Mars. I was immediately attracted to the concept behind 26 Treasures, because while the facts and figures comprising human history are compelling, I’ve always been amazed at how universal and unchanged are the complex emotions linking people of every nation, and throughout millennia. Thus, armed with a bit of imagination and information, it’s tremendously tempting to slip into someone else’s skin and feel the world as it once was.

Leaving the museum with the ferrous tang of the Darien Chest clinging to my fingers, I did a bit more research. I don’t want to become an expert; I don’t want to research the emotion right out of this experience. But I did want to probe the scar a while, and think about what the Darien Scheme might have meant to Scots in its time. (And oh, how bitterly I laughed when I learned that the payout of Equivalent Money eventually led to the creation of the Royal Bank of Scotland, which has wreaked havoc anew on the Scottish economy.)

I have probably walked past this chest dozens of times before, and have certainly skimmed articles about the scheme in the past. But this time was different. This time I had a connection. It was vital to stop and pay attention -- because this time it was personal. So here’s an idea: Why not assign every school kid an object from one of Scotland’s museums at the start of the academic term? Give them a couple of assignments, spaced throughout the year. Perhaps they could draw their object, deliver a ten minute presentation about the story of their object, or capture the essence of their object in just 62 words? There’s nothing like making a connection to fire up the imagination.

#Lee Randall#Darian chest#Scottish economy#enlightenment#scottish history#nms#inspiration#financial markets#scotsman#museum#royal bank of scotland#26 Treasures

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On being sorry by Jamie Jauncey

Alone in a glass case in the Church section at the back of level three of the National Museum of Scotland stand two objects which, at first glance, seem quite unexceptional. One is a square wooden chair. The other, draped on a display dummy, is a dull-looking gown.

On closer inspection, the chair reveals nothing. It is simply dark and polished with use. The gown is odd, though. It is not made of any fine stuff, but rather sackcloth, now worn and threadbare. It is not a garment for grand occasions.

But this is the Church section, remember, and the church in question is an unforgiving kirk where questing nostrils were constantly alert to the stench of moral turpitude, and the salvation of souls was prosecuted with much energy, zeal and inventiveness. The chair and garment are two of the great seventeenth and eighteenth century instruments of ecclesiastical discipline. Otherwise known as the Stool and Gown of Repentance, they were to be sat upon, or worn, in front of the congregation, by fornicators, adulterers, slanderers and other wrongdoers.

Jonet Gothskirk was one such. Between July and November 1677 she appeared before the congregation of West Calder kirk on thirteen successive Sundays for her adultery with a certain William Murdoch. ‘Because of her stupidity and that she could discover no sense or feeling of her sin, nor sorrow for ye same,’ she continued to wear the gown each Sunday, week after week, while the minister fulminated at her wickedness. Nature eventually intervened and she was released on account of the imminent arrival of her child.

But what did she feel, what did she think to herself while she stood there, Sunday after Sunday, her belly swelling, her legs aching, the sackcloth scratching at her skin? Did she look out at the congregation and read behind the pursed lips, the solemn faces, ‘There but by the grace of God go I’? Did she glance at the minister and rage at the hypocrisy that the Bard would immortalise a century later in Holy Willie’s Prayer? Was she so cowed by the collective opprobrium that she simply stood there and hung her head in misery? Did she long to be back in the arms of William Murdoch for whom no punishment was recorded? Was she simply resigned to her fate? Or was she too fearful for her own future, and that of her child, to think of anything but what she would do when her present ordeal ended?

I don’t know, but I have to find out because now that I’ve been to see the gown, it’s Jonet’s voice I’m beginning to hear. I’m not yet well enough acquainted with her to know what she’s saying, but I will be. By the end of July, the project deadline, Jonet will have spoken.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Ireland. Funny place. Even funnier people.

Not many of us like the usual associations. Say you’re from Northern Ireland and chances are, you’ll be met with one of the following responses.

1. Are you a protestant or a Catholic? (Variation, do you see yourself as Irish or British?)

2. Have you ever seen anyone shot?

3. Do you know my Granny? She’s from Cork.

I realise that we’ve largely brought this on ourselves. Nations who appear to be addicted to belting the crap out of one another can’t really be surprised when belting the crap out of each other seems to be the number one visual association.

On the other hand, we’re not just good at being bloody. We’re also bloody good at telling yarns, making people laugh (like proper belly laughs) and spinning tales. No coincidence then that some of the greatest writers, musicians and artists to have committed thoughts to air and paper have come from good old Norn Iron. I wonder why, often.

Could it be down to the collective argumentative streak (read belligerent), or the non verbalised, insecurity complex (we’re in denial), might it have something to do with the identity crisis (too many to list here), but the truth is we do like to undo people’s prejudgements. Quite often by being wittier, smarter, more articulate than people expect us to.

Whatever psychology lurks beneath, it doesn’t extend to a national level. Northern Ireland is full of creative talent. Designers, writers, artists, poets, illustrators, photographers, composers, all doing wonderfully evocative and provocative work. Can’t we put this on the agenda for discussion? Just a thought, but wouldn’t a regional identity based on creativity help our economic situation? We can’t keep apologising to the rest of the world for our internal struggles, so perhaps it’s time to change the topic of conversation.

(Lucy Caldwell and Karys Wilson have been paired with The Clonmore Shrine – a miniature classical tomb that housed relics of Christian saints, decorated in a native, pre-Christian style.)

26 Treasures at the Ulster Museum is a starting point – one way to reconnect words and images with vestiges of people and places from our past. Writers randomly paired with artists, randomly paired with our most beloved treasures, each pair exploring new ways to retell their secrets centuries later. And on 23rd June, 52 of our most cherished creative talents came together at the Ulster Museum to discover their object and their partner. Lucy Caldwell, one of our 26 writers and award winning author and playwright, is already excited about her treasure, the Clonmore Shrine:

“The Ulster Museum is full of such wonderful treasures – those I remember from my childhood, instantly dramatic, such as the dinosaur and the mummy, and many more which are no less evocative. Between them they’ve seen centuries – millennia – of life, death, strife, freedom, secrets, hope, certainty, fear, doubt, yearning, love. Walking around the Ulster Museum, you can’t help but think: if only each object could tell just one of its stories – one of the times it's lived through or lives it’s seen! So when I was asked to take part in this project, alongside some of our best poets and writers, I was immediately inspired by the thought of teasing one of its myriad stories from my object. A few days in, and I’m starting to wish I had 6,200 words, not just 62.”

My hope is that 26 Treasures at the Ulster Museum will go a small way to celebrate how creativity, history and collaboration can touch our lives, challenge us to reflect, think and articulate ideas and thoughts we never thought possible. Who knows, it might even go some way to sorting out some of those identity issues.

(Poets Michael Longley and Ciaran Carson enjoy a cup of tea at the launch of the working group for 26 Treasures at the Ulster Museum on 23rd June.)

Written by Gillian Colhoun

Organiser of 26 Treasures at the Ulster Museum

26 Treasures at the Ulster Museum will be exhibited in The Belfast Room at the Ulster Museum, 14-29 October 2011.

Photos by www.photosby.si

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lovely cuppa by Sarah Burnett

I have probably passed my golden teapot many times during the past decade, but never noticed it. Children choose my path through the Museum, and without the vital elements of taxidermy or moving parts, the teapot does not stand a chance.

Told that we are off to look at a golden teapot, they are mutinous. One rejects it in favour of craft activities; the other defiantly reads a book about cricket. Good, I think, at least I can commune with my object in peace.

But I don’t commune. My first view of the teapot leaves me underwhelmed. It’s precious, it’s rare, there’s fine engraving, but its shape and lines don’t appeal to me. Gold and royal coats of arms are not really my thing. Lacking any knowledge of goldsmithing, I cannot even salivate at its craftsmanship or rarity.

However, the teapot is my assigned treasure, and I have to look again. Since there is no visual connection, perhaps words and knowledge and themes will help.

The teapot was a prize at Leith Races in 1737-38. The races were held on the sands at Leith, before the docks were built; they then moved eastwards to Musselburgh, where I sometimes go the races myself. Phew, a link. My teapot and I have horseracing in common, and I can sketch mental pictures of the crowds, the races, the horses (though they must have been far heavier in 1738, to cope with running miles over wet sand).

The mental pictures brighten as I read the texts. Racing was traditionally a sport run by the gentry for the gentry (it still is, though you should now substitute ‘rich’ for ‘gentry’). But like today, its appeal stretched far beyond the people who owned the horses. While the King and the wealthy and the rising middle classes awarded each other gold teapots and other fashionable treasures at Leith Races in 1738, thousands of less socially-elevated Scots were spending the week drinking, fighting, womanising, and generally having a riotous time. Imagine the Bath of Jane Austen juxtaposed with a week-long Hearts-Hibs derby.

There’s clearly a class angle, and social change too. The goldsmith was James Ker, who later became an MP. Having bought himself an estate in Roxburghshire, he took on the grander identity of James Ker of Bughtrig. As the helpful legend in the Museum tells me, this was the age of improvement.

Horseracing, social change, class, the Enlightenment. James Ker’s teapot becomes more interesting.

Several days after first scrutinising the teapot, I belatedly realise there’s yet another story. Tea. The teapot dates from the era when Britain was falling in love with tea. When Samuel Pepys first tasted tea in 1660, it was barely known in Britain. Over the next century in Britain, it became a passion, a fashion, an addiction. There were tea taxes, tea smugglers, tea wars, and debates over its heath benefits or dangers. Half a century before the teapot was the prize at Leith Races, many people there would not have seen a teapot or tasted tea.

I still don’t really like my teapot visually, but I’m excited about the themes. Sometime the physical properties of an artwork can move you, sometimes you need a story as well.

The thousands of objects in the Museum all have their own stories. I find this humbling. If I ignore an object on the grounds that it doesn’t suit my taste, I’m missing out on stories, ideas and connections. The teapot has stirred up dozens of ideas about things I want to know more about: from the story of the winning owner Mr Carr of Northumberland and his horse Cypress, to the Scottish Enlightenment, to tea. This is why good museums are so exciting: the way they can leave you fizzing with ideas, curiosity and connections.

So, next time my children want to look at Jackie Stewart’s F1 car, or a stuffed Scottish mammal, I’ll revisit my gold teapot instead. And maybe one day they’ll agree to come with me.

#Sarah Burnett#Golden Teapot#nms#scottish history#tea#racing#horses#leith#james ker#samuel pepys#scottish enlightenment

0 notes

Text

Lizziae's post by Aimee Chalmers

A wee bookie poems bi Marion Angus (1865 -1946) fell frae a library shelf, as if bi magic glamourie, at my feet. Her Scots tung heezed up ma hert. Her weirdfu, ghaistly verse, an her sparkie wit on the natur o time dirled ma heid.

A thoosand years o clood and flame

An a’ thing’s the same and aye the same

Whaun I read what some tattie scone had said aboot her: ‘no life could be less conspicuous’, I was scunnert. I did some delvin for masell, then wrote doon the richt wey o daen (the start o a selection o her work). That wasnae eneuch: I kent hoo she thocht aboot things frae whit she wrote and wantit mair o her spirit tae come though. Sae I traivelled her ‘Tinker’s Road’ wi her, for some five years. Gey chancie, spookie things happened (whiles gied me the cauld creeps), but in the end I ‘won ower the tap’. My wee story gets nearer the hert o her than onie ‘facts’ did.

But whit happens noo? What’ll I dae next? Will I ever be able tae move on, turn ma back on Marion?

Three weeks o gropin i the dark, then ‘26Treasures’ cam scootin intae my laptop – mair magic glamourie. I left Marion ahent wioot a glance ahent me. The National Museum o Scotland – ye would ken I’d jump at the chance! I’ve aye felt prood tae be a Scot, but michty, I was fair taen wi ma first visit tae whit was then an affa new museum – 650 million years o history!

I cannae think o Westlothiana lizziae as my ‘object’. She’s a glisk o history – pre-history – agin a backdrop o cheenge (just like ane o thae lassies in Marion’s poems). She’s jimpie and little-buikit (but guid gear gaes in sma buik); her model’s strippit coat looks like it’s fashioned o teeny beads – sae bonnie and sae real I cannae imagine ither.

Naither can I think o 62 words that’ll dae her justice.

I winnae screive a tale o whit she did. There’s less facts aboot Lizzie than would fit a pin-heid, if facts are chiels that winna ding. But here’s whit I’ve gaithered, and ye can sort them oot yersel.

Westlothiana lizziae

Fossil discovered in limestane rock strippit wi black and pale broon layers (1988) bi Mr Stan Wood, at Kirkton Quarry, near Bathgate.

740 entries on the web, contradictin ane anither!

Fower cutty legs.

Lang tail.

Mrs Marjorie Macrae devised a Strathspey aifter her.

Represented in Spirit o West Lothian tartan as a black threid.

338 million years auld, gie or tak a puckle either side.

Habitat: tropical swamp, near a muddy loch (lake?) polluted bi volcanic springs.

Weather: storms an floodin.

Hazards: forest fires, scorpions, hungert amphibians. Bigger Lizzies. (Did I nae tell ye… cannibalism?)

Food: centipedes (pooshinous?), millipedes, mites an harvestmen. Wee Lizzies?

Ye micht get raivelled at this neist. Lizzie walked the swamps i’ the back-end o the Carboniferous years. So she cannae be a lizard. They didnae evolve til 180 million years aifter that. She could be a reptile, or an amphibian (reptiles lay eggs wi shells, on the grund, amphibians lay eggs in waater).

Let’s nae argie-bargie aboot the turn o her ankle, though some jalouse that maks her an amphibian. Let’s mak believe Lizzie is a reptile. The bad news: mibbe her particlar evolutionary line cam tae a sticky end lang ago.

Let’s mak believe it didnae.

Reptiles the day, an mammals, shared an ancestor awa back in time, so Lizzie micht be oor distant relative. But I’m nae even gaein tae try tae work that oot. I aye thocht a great-aunt was somebodie that gied ye a penny and I still get dottled wi second cousins twice removed.

Mair mixter-maxter: Lizzie’s secret – the lassie could be a laddie. And if that’s richt … she’s surely Jock Tamson and we’re her bairns.

Whit on earth can I scrieve?

Westlothiana lizziae.

Westlothiana Lizzie

West-lothi-Ana-Lizzie.

Anna Lizzie

That’s braw. ‘Annie Lizzie’ in Scots. Annie Lizzie? Whaur hae I heard that afore?

…

The sands o time rin doon – doon

The years turn blin’ and spare

Annie Lizzie’s gane and wi her

A’ that’s young and fair

But…

Hereawa or thereawa

On midsummer’s eve

Young Annie Lizzie’s

At her game o ‘Mak Belive’.

Midsummer’s eve? Mak believe? Spooky!

Whit wey did Marion Angus dae that?

References:

‘The Fox’s Skin’, ‘The Tinker’s Road’ and ‘Links o Lunan’ by Marion Angus in The Singin Lass: Selected Work of Marion Angus (Poygon, 2006)

Westlothiana lizziae