Text

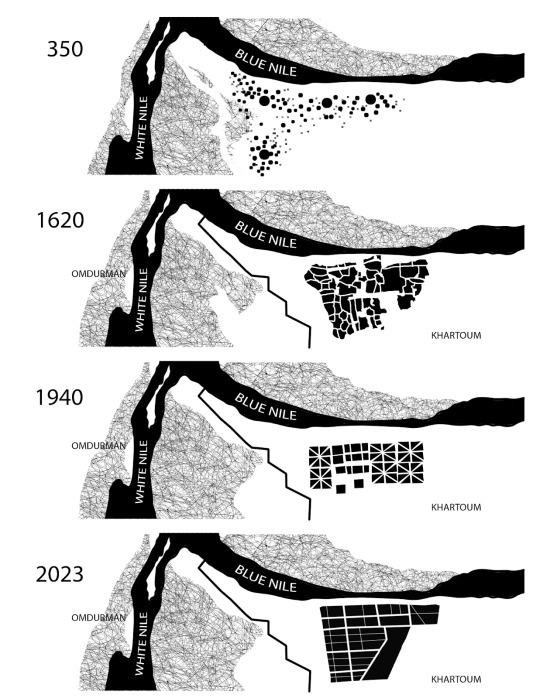

Mapping Postcolonial Sudanese Urbanisms in Khartoum

fall 2023

Introduction

With Sudan’s recurringly-scarred legacy of occupation after siege after occupation after civil war, urban development in its major cities have been either imposed or established in self-defense. Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, has been forced to morph according to the wills of political actors and social unrest. With Khartoum being actively razed and depopulated by 6 million in the ongoing civil war (as of December 2023), rebuilding for lasting change necessitates reimagining it devoid of colonial stress, something that has not happened since prehistory (UNHCR 2023.) Dreams to rebuild Khartoum cannot occur without documenting its trajectory of change over its ancient history--not only to honor its legacy, but to challenge the longstanding academic neglect of its culture and people.

Sudan, the Region

Sudan is an expansive Northeast African nation, which was the largest African country prior to its division into North and South Sudan in 2011. Geographically, Sudan borders Egypt and Libya to its North, Chad to its West, and Ethiopia to its East. Through this position, Sudan exists as a gateway from the Arabized Middle East and North Africa to Black Africa. In fact, the name Sudan itself originates from its Arab settlers--بلاد السودان/Bilād as-sūdān, or "land of the black (color) people,” after the notably dark skin of its indigenous inhabitants. This transition occurs environmentally, as northern deserts become southern savannahs.

Although still contested, much archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest human ancestors and Homo sapiens ourselves originated in Sudan. A rich prehistory and foundation of one of the oldest civilizations remains very undocumented across disciplines of archaeology, genealogy, geography, and architecture. Beginning a dialogue of its urban evolution requires a general understanding of its history.

A Reductive History of Sudan

The beginnings of the Sudanese nation date to around 3,500 BCE, with the Meroitic Kingdom founded between 300 BCE to 350 CE. Across its kingdoms, rapid urbanization due to its rich agricultural and mineral economy led to the foundation of multiple centralized city centers.

The first indigenous Sudanese (Nubian) kingdom was the Kush empire, established by 750 BCE, and surviving until 350 CE.

Between 350 CE and the Arab invasions of the 7th century, not much further concrete documentation has been established.

In the 7th century, Nobatia and Makouria merged into one kingdom, which was dominated politically by the Makouria Kingdom.

Muslim Arabs invaded Makouria and defeated it, the Funj Islamic kingdom was established, with Sinnar as its capital in 651, flourishing for 3 centuries. This marks formal islamization of Sudan.

In 1820–1821, the kingdom was destroyed by a Turco-Egyptian army as a proxy for the Ottoman Empire. A Sudanese national named Mohamed Ahmed ibn Abdalla, known as El Mahdi, revolted and successfully ousted them, beginning a short-lived era of Sudanese self determination.

In 1898, sensing a weakness in Sudan’s forces, British forces invaded, ending the Mahdia era, and together with Egypt, began the rule of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan under the Condominium Agreement. Khartoum was chosen as the capital of the state which lasted until Sudan forcefully gained its independence in 1956.

Since independence in 1956, the history of Sudan has faced recurring internal conflicts:

First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972)

Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)

War in Darfur (2003–2010)

Third Civil War (2013–2020)

Civil war reignites (2023- )

Khartoum, Sudan

Khartoum was founded in 1821, as a part of Egypt b urban planner Muhammad Al-Saeed Samaha Bey. Its location is sought after due to its setting at the convergence of the White and Blue Nile rivers to form the Nile River, which bisects the country vertically.

Beginning as settlements of Nubian-Egyptian natives, greater Khartoum was scattered to form small villages that can be traced back to the 16th century. Khartoum was not designated as an official capital until 1821, under the Turco-Egyptian occupation of 1821. Here, an agrarian slave society, with Sudanese laboring as slaves in their own homeland, was established. This remained until the revolution of Mohammad Ahmad Al-Mahdi, who recaptured Khartoum, ending the Turco-Egyptian occupation, and established Umm Durman, a smaller city to its west, as the capital. This Mahdiist era lasted until 1898, when Egyptians conspired with the British, at the height of their plunderous conquest of Africa, to establish an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium. The Mahdist army was defeated, and Khartoum, in symbol of the previous Egyptian domination of the region was re-established as capital. Political independence was eventually achieved in 1956 with Khartoum remaining as the capital, serving administrative and military outposts.

To begin piecing together the consequences of this historic sequential colonization and its effects on the urban landscape, we must establish the link between urbanism and colonialism.

Urbanism and the Colonizer

The contemporary field of architectural urbanism, one undoubtedly rooted in Western colonial dominance, has long championed designing cities of order, function, and uniformity. The forefathers of urbanism, Western urbanist giants like Hippodamus, Le Corbusier, Jane Jacobs, and Robert Moses left built and theoretical legacies in their efforts to tame the field of urbanism and city planning.

In contemporary urban design disciplines, many have begun exhibiting interest in contesting these longstanding laws and legacies, selling flashy design concepts like the 15 minute city or alternative material construction. Implementing larger communal spaces, blurring the lines between private and public property, using impermanent and biodegradable construction material, and decreasing reliance on vehicles, designers of several disciplines seem to iterate against the principles embedded in their education.

Beyond the bubble of hegemonic Western urbanism, it has been acknowledged that the foundational elements of institutionalized city planning--orthogonal street grids, zoning laws to segregate functions, wide car-centric circulation--are the footprints of Western colonial projects. Urban Geographer Mohamed Babiker Ibrahim writes,

“Pre-colonial morphology is characterized by narrow, winding, and congested streets. On the other hand, morphology of colonial cities—or those with heavy colonial influence—in Africa and Asia is often characterized by grid-patterned streets and the segregation of ethnic groups.” (Ibrahim 2014)

Consequently, these very practices of multifunctional communal urbanism and earthen construction were practiced in nations in the Global South prior to colonial intervention. Historic divergence from this method in these regions nearly always indicates the past presence of a colonial power. This is no coincidence. Comparisons between Western urbanist and West European colonial tactics reveal stark overlaps. When the British implemented the Divide and Rule policy in their apartheid regime in India, Architect Louis Sullivan coined the common phrase “form follows function” in justification of segregated city blocks. Robert Moses, in staunch justification of the estimated 250,000 he displaced in his urban planning career, penned, "I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs." (Boeing 2017) Striking similarities between the 1940s British colonial city plans that forcibly removed 3.5 million Black South Africans, and the 1950 Jerusalem City plan that displaced 5.9 million Palestinians (Citino 2023) have been noted by the ANC themselves (African National Congress, 2018.) Le Courbusier’s fetishism of Arab-Amazigh architecture culminated in his razing and rebuilding of Algerian city centers, since his appreciation for those indigenous practices was never genuine enough to preserve or realize them. The sheer scale of city planning campaigns, and the perception that moving inhabitants around like pawns is necessary in order to demolish and erect built environments at will, mobilize both colonial projects and urban planning.

In a sense, the act of urban development and master planning becomes a greatly colonial act. This is not because urbanism and development is an inherently Western concept, although it is an inherent expression of domination by altering the built environment en masse. Thus, Urban planning has, throughout multiple colonial projects, been the catalysts to realize schemes of exploitation, displacement, and even genocide. And so, historic urban features, optimized by indigenous population for their environments, are deemed barbaric and backwards at its worst, and reduced into ornamentation at its best. The rich historic developments in construction technology and community placemaking are forgotten by the field, to be “rediscovered” and exalted in a Western institution. In the case of Sudan, these consequences have long devastated and scarred its cities. Mapping its history and architectural lineage retroactively, however, is a step towards retribution and setting precedents to build forward.

Mapping Khartoum’s Urban Evolution Across Colonial Chapters

Prehistoric and Pre-Islamic Sudanese Urbanism (3,500 BCE)

Distinctly pre-Islamic traditions of urbanism in Sudan occurred adjacent to the Nile River, where cities were established in modern-day Khartoum before its official inception. The first urban environments were born of a partial “Egyptianization” of riverine northern Sudan. Residential areas remained scattered among monuments, like the Nubian Pyramids that had been built prior to 2550 BCE. for at least two thousand years. Such settlements were especially large and prosperous during the Meroitic Period of 300-400CE. This urban typology of residences scattered among community monuments endured for around 2000 years.

Early Islamized Khartoum (1520-1820)

The traditional Muslim cities of north central Sudan and modern-day Khartoum can best be described with Nubian adaptations fitted to the archetype of a “Muslim city”, which Arab settlers brought with them during their settler conquests. Cities began to centralize and condense, acting as trading centers enshrouded by irregular streets with particular circulatory functions. Despite the use of “Islamization,” religion played a very minor role in the general urban fabric. Mosques and Churches demarcated residential units, very rarely being in city centers themselves. Universities, instead served the public in the city center, alongside tombs of exceptional Sudanese figures. In this way, Arab and Islamic influences, although certainly modeled after existing Arab cities, did not dilute existing Nubian cultural landmarks. Although it did begin to segregate public functions of work and school by concentrating them into the city, architecture itself through form and function was relatively preserved. Nubian settlements scattered remained built around monumental buildings. Earthen architecture continued to be built as opposed to Arab building typologies, like this earthen Qutiyya house.

Turco-Egyptian occupation, slavery, and shifting attitudes towards and ownership (1820-1885)

In 1820, the Ottoman Empire began their conquest of Sudan. They established Khartoum, which has previously been a conglomerate of multiple small cities. The capital was connected by trade routes, still functioned as commercial centers, and still had markets and an irregular street pattern. Although the physical formation of these cities remained similar, their functions drastically and destructively changed. The occupation changed the pre capitalist system of land tenure to one with a system of private property. This shifted the traditional system of agricultural labor, particularly through the introduction of agricultural slavery of the Sudanese themselves, introducing both slave and apartheid conditions that then began to alter the layout of the city. The Turkish enslavement of Sudanese in their own land made land ownership industrialized and extremely difficult for Sudanese themselves to inherit land, which was becoming privatized in swaths. This also changed the demography of the region, as poor and enslaved Sudanese fled to the South. In addition, many heritage buildings and monuments were also destroyed-- the Turkish settlers began to shave the tops of pyramids off after hearing rumors of there being gold in them. A disregard for indigeneity and the brutal institutionalization of slavery set a precedent for deep structural racism that began with the organization of the city.

The Mahdist Era (1885-1899)

Muhammad Ahmed, nicknamed Al-Mahdi prophetically, was a general who organized a slave revolution against the Turco-Egyptian occupation. Their victory ushered in a brief era of anticolonial Sudanese nationalist Independence. He shifted the capital from Khartoum to the neighboring city, Omdurman, where Khartoum was neglected until British colonialists, with their eye on the agricultural and mineral-rich region, conspired with the Egyptians to again impose a period of violent occupation.

Khartoum’s Morphological Evolution During British occupation (1899-1956)

When Sudan became under British colonial power in 1899, the first thing the Governor-General Kitchener did was to establish Divide and Conquer Policy, constructing a colonial apartheid city back in Khartoum. The British cleared residential areas and cleared indigenous architecture to begin plundering the area (Njoh, 2007). His partner Willian Mclean, a Scottish colonial officer and architect, drew up a comprehensive plan for Khartoum. He began by introducing a four-tier neighborhood classification system consisting of: first class, second class, third class, and native lodged areas. (McLean, 1980). European settlers lived in these first-class zones, filled with green spaces, clean streets and excellent water and electricity supply. Sudanese people could only live in zones designated third class and below, effectively establishing a brutal apartheid with separate infrastructure serving them entirely. The traditional Nubian and Nubian-Islamic city structure was not entirely eliminated, just pushed away to the borders and rural outskirts of Khartoum, likely existing as pictured below, segregated from all-White zones.

Post-Colonial Aftershocks following the Declaration of Liberation: Islamism, Foreign Intervention, and Deurbanization (1956-)

Planning and layout of Khartoum after Sudanese independence in 1956 continued in this colonial path. A grid system was similarly applied in newer neighborhoods, which were still divided into first, second, and third class, based on size and quality(Hafazalla, 2006). Multistory buildings in an international architectural style were built. Khartoum began to expand horizontally, and the administrative area at its core swallowed up the previous regions inhabited by British occupiers in first-class zones. Still, a colonial mindset is extended through the continuation of this quality ranking systems, and class divide is deepened as economic activity concentrates more at Khartoum’s core.

The dictatorship of Omar El-Beshir, beginning in 1993 and lasting 26 years, fueled fundamental Islamism as well as virulent corruption. Reactionary Islamism begun to impact the urban environment in reaction to the desire to return to the precolonial glory of the region that had been continuously plundered and suffocated for 2 centuries. In response, monuments of colonialism, like the All Saints Cathedral built after General Gordon in Khartoum, were demolished. Mosques, in an act of defiance were quickly erected around Khartoum.

A short-lived establishment of the Khartoum Planning Committee (1960s-80s) was responsible for much infrastructural development, and was well-respected. Under a corrupt government, however, it soon fell to internal corruption and external international corporate exploitation. Multiple master plans had since been proposed and deemed financially unfeasible. A reliance on China and Saudi Arabia to Finance infrastructure, with terms of manipulative debiting and resource exploitation sending Khartoum, the economic capital of the nation, into financial crisis.

Under El-Bashir’s reign, a slew of genocidal campaigns against the regions outside of Khartoum with differing ethnic and cultural makeup ensued. The Darfur war killed thousands, displaced millions, and destroyed cities that in function, were similar to Islamic-Nubian layouts of scattered earthen homes around community centers. South Sudan seceded following another Civil War, with aid from the British in 2011.

In Khartoum, the capital degraded in tandem in the wake of further corruption. Public parks were closed and “sold” to government officials for personal use. Inflation made living in the city impossible for all but a select few. Khartoum was impoverished back into ruralism, with uses of animal transport more affordable than driving cars, and conversion of unaffordable, empty housing to shanty homes.

Contemporary struggles in Khartoum, 3.5 Civil Wars later

Today, Khartoum has turned into a war zone amid the deposition of Bashir and his trial for crimes against humanity. A power struggle between his two former military aides, with the Sudanese Army under the command of Abdul Fattah Alburhan and the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary group under Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo has ensued absolute destruction. Bombing campaigns began on behalf of the RSF in April 2023, and violence, genocide, and disposession have ensued. Much of what was left of Khartoum’s residential areas was looted and flattened. In all, two million refugees are living in the fringe of Greater Khartoum in slums or squatter settlements. Infighting has destroyed infrastructure, heritage sites, killing millions and displacing 6 million refugees in total, as of December 2023.

Mediating Scarred Cities with Postcolonial Thought

How can Sudan move forward in the wake of seemingly endless atrocities? Through these horrors, in acknowledging that these events unfolded after a series of colonial conquests claiming lives and resources, and only leaving power vacuums to be filled by corrupt officials and vulture-like international forces, it is only accurate to state that the postcolonial era in Sudan was never brought to fruition. Though breaking past this cycle of dispossession and exploitation, there are anecdotal references of deeply scarred nations and cities in their struggle for agency and resilience.

The era of postcolonial thought, defined as “the historical period or state of affairs representing the aftermath of Western colonialism” (Ivison 2023) brought sociologists, anthropologists, and activists to imagine paths forward of the colonized from colonial violence. Both the study and act of urbanism and urban development mobilize this path, by establishing the built environment in reflection of progress from scarred histories. The theories of postcolonial figures across the globe, although they may not have been created within the field of architecture or urbanism, inform the process of mediation just as the theories of colonial domination informed the processes of rigid and imposing cities.

Palestinian Edward Said’s work on orientalism and the White gaze deconstructs the inherently colonial nature of urban planning in the colonized architect’s mind. Orientalism, which he defines as “a style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between "the Orient" and "the Occident” (Said 1978.) Through this binary distinction, Said argues, further binaries like “good” and “bad,” “moral” and “immoral,” “developed” and “barbaric,” are assigned to this geopolitical one. Those who dominate determine which binary applies to them. This framing allows the absolute dissonance between those in the Occident, who claimed their power through acts of immoral dominance and destruction, to assign morality for themselves. This confrontation of the facade of represented goodness of the West forces the designer to see through the systemic assumption, in urbanist theory and practice, that the qualities of western urbanism are any more developed, dignified, or legitimate than those practiced in the South. A Sudanese qutiyya house is not any less legitimate than a British terrace house. The architect must understand this to effectively challenge built characteristics, lest they appropriate an existing indigenous one and claim it as their own.

The decolonial work Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial activism describes a path of agency and self determination, one that would provide agency for the displaced and disenfranchised Sudanese. In his Work Wretched of the Earth, Fanon states,

“The Third World must not be content to define itself in relation to values which preceded it,’ he warned. ’On the contrary, the underdeveloped countries must endeavour to focus on their very own values as well as methods and style specific to them.” (Fanon 1961)

Through our analysis, we have seen that Khartoum’s developing agents following colonialism have already fallen victim to the need to conform to colonial ideals even in their wake. Indigenous architectural methods and styles, developed specifically with the climate and material conditions in mind, had been suppressed and replaced by British settler colonialists. As Fanon also argues, colonial violence narrows the mind of those who it victimizes, as well as its colonizer. Colonizers imposed unfit built conditions upon Khartoum because they did not see value in it, and unfortunately, this spite has also infected the minds of Sudanese developers. A reclamation of this isn't only an act of defiance, but a readoption of genuine and appropriate methods.

Moving Forward: Healing and Designing for the Future

Critiques of Urbanism as an inherently colonial act began once the discipline transitioned from a collective spatial evolution into an institutionalized act of imposition. The process of urbanization and master plans themselves, in colonial history, are predetermined schemes designed by the few, imposed upon the many. Urbanism relies upon adaptability and the molding of the built environment to the needs of its inhabitants, and this adaptable and domestic reality is often overlooked when working at a large scale. Through this history of persistent colonialism and exploitation, any shred of self determination to craft one's environment has been stripped from the Sudanese.

Unfortunately, this reality is not unique, and Sudan is not the only nation to suffer in this ongoing struggle. To track the large-scale morphological changes in the built environment, as this paper hopes to do, is only a superficial beginning in unpacking the spirit of Sudan’s urban struggle. It would be reductive to introduce this knowledge as novel, because although this specific topic is academically neglected, to suggest that the wills of the Sudanese to form their own environment have not been voiced, mobilized, and silenced is both reductive and untrue. In addition, speculating routes of healing in the clinical and detached mediums of writing and drawing, and detached from the land itself, is an irresponsible feat that would eventually repeat the same presumptive colonial actions. The most competent actors for change are the Sudanese in Khartoum themselves. True advocacy lies in the labor of documentation, resource mobilization, and fighting against the ongoing and persistent subjugation of Sudanese land, lives, and resources.

After mapping this colonial legacy in contrast with other instances, my argument remains that introspection of urban practices inherent and original to Sudan and its inhabitants are a seed of potential to be protected. I cannot say that I am hopeful that this seed will be able to germinate and thrive in the near future, undisturbed, into the will and hopes of Sudanis. Still, the labor of documenting this past and breaking through colonial mindsets, difficult as it may be, is an act that a generation of urbanists and architects ought to perform in order to prevent further designing a hostile world. In addition, this work must be done, as there is no greater injustice to the colonized, besides having been colonized, than to be both colonized and forgotten.

//

Resources

Mahmoud, A. A. (1995). "Urbanization and Planning in the Sudan: The Case of Khartoum." Cities, 12(3), 141-148.

Ibrahim, A. H. (1985). "Colonial Impact on Urbanization: The Case of Khartoum." African Urban Quarterly, 1(2), 147-156

O’Callaghan, Cian. (2012). Contrapuntal Urbanisms: Towards a Postcolonial Relational Geography. Environment and Planning A. 44. 1930-1950. 10.1068/a44615.

Hassan, S. S., i in. „Urban Planning of Khartoum. History and Modernity. Part I. History”. Wiadomości Konserwatorskie, nr 51, Stowarzyszenie Konserwatorów Zabytków, 2017, s. 86–94.

Jok, J. M. (2001). "The Culture of Politics: British Colonialism and Political Modernity in Sudan." African Studies Review, 44(2), 1-21.

Ali, A. O. (2017). "Urbanization in Sudan: Historical Phases and Future Prospects." In A. Dafaalla, A. Mustafa, & A. Omer (Eds.), The Geographies of the Sudan: Historical and Contemporary (pp. 219-234). Springer.

Prakash, G., ed. After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

APA. Said, E. W. (2003). Orientalism. Penguin Classics.

Fanon, Frantz, 1925-1961. The Wretched of the Earth. New York :Grove Press, 1968.

0 notes

Text

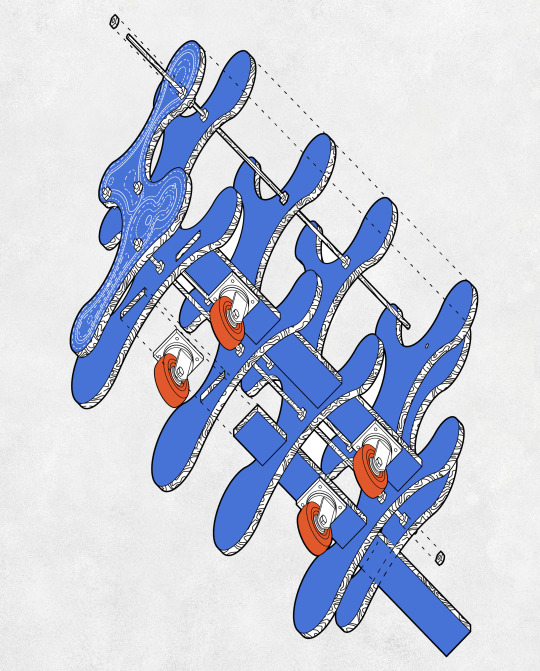

megainfraecosuperstructure

spring 2023

Tasked with designing and integrating a hostel for nomads in New Orleans’ downtown, this proposal braces to be infested by living, nonhuman, and nonliving lodgers. The site is a vacant lot sandwiched between a hotel and condominium, all existing complacently among a row of other abandoned parcels, AirBNBs, and chain hotels just one block removed from the lively French Quarter. With a fixed function, how can yet another hostel in this region avoid a fate of fleeting exploitation and later abandonment? Perhaps an authentically New Orleanian model of this deliberate temporariness and resolved dormance already exists: The parish’s sprawling industrial sector, demarcated by shipping containers, cranes and freight trains, that is perpetually visible in the skyline as it twinkles along the Mississippi River. This commercial mechasystem embodies the spirit of a hostel in its own right, economically housing cargo as its inhabitants, each container anticipating journeys of their own.

And so, a massive rigid steel frame is erected and sets the meter for prefabricated modular “living containers,” shipped to site along the same freight route the steel is manufactured in. Each module is then assembled to be braced and strung upon the superstructural frame à la Yona Friedman. With the hostel units perched above, smaller greenhouse structures accessible by all are activated for communal use. These greenhouses hover on stilts, liberating the earth into an urban wetland to house its green inhabitants. While the wetland is integrated to regulate itself and its permanent residents, it fronts water collection and purification systems composed of cisterns and

filtration-sterilization systems to deliver it for visitors above. A decentralized HVAC network in the form of multiple DOAS systems which only serve specific living container regions ensures that

this ecological and mechanical labor is only used as necessary. In this fashion, and with removal/addition and rearrangement intrinsic to the life of this megastructure, a fully-booked scenario is just as premeditated as it would be in a “dormant” greenhouse state

0 notes

Text

construction drawings

physical model // paper and aluminum

0 notes

Text

jefferson island museum and research center

fall 2021

Jefferson Island is a scarred landscape that was the site of mass industrial exploitation before the Lake Peignur disaster of 1980, where the collision of salt mining and oil drilling shafts created a subterranean vacuum, sinking the lake bed 150 feet. Upon this fragile pier, traces of its past use as a loading dock for mineral imports sourced few feet away are evident through signs of natural and industrial wear and age. Where this structure is perched, right besides the strip of land along the pier, is where barges might have been anchored as they were loaded with minerals extracted just a few hundred feet below. From there, the barges journeyed forth across the expanse of Lake Peigneur. Such historical and directional implications are reflected in the structure's origin and orientation, as well as the linear circulation encouraged by the vertical push-and-pull of the building's aggregates.

0 notes

Text

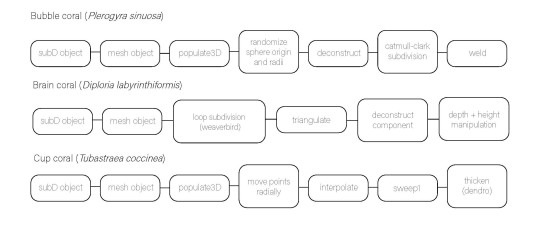

generating coral

fall 2022

Photographs of three 3d-printed coral generations on foam pedestals.

This investigation began by examining the growth sequence and physical geometries of three species of aquatic coral. Their unique biological development sequences were mimicked through scripts written in Grasshopper, and 3D printed with resin.

Brain coral (Diploria labyrinthiformis,) Bubble coral (Plerogyra sinuosa,) and Cup coral (Tubastraea coccinea,) photographed respectively, were the species recreated. Whether the volumes were inflated from scattered spores, thickened from organic cleavage, or developed by splintering off fractals, each script copied the process, so they may be applied to infest any mesh object. Possible applications of this investigation involve contributing to the established architectural niche of using biomimicry to mediate built interventions in the natural world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

a room with a view

intimate art gallery and studio

fall 2021

0 notes

Text

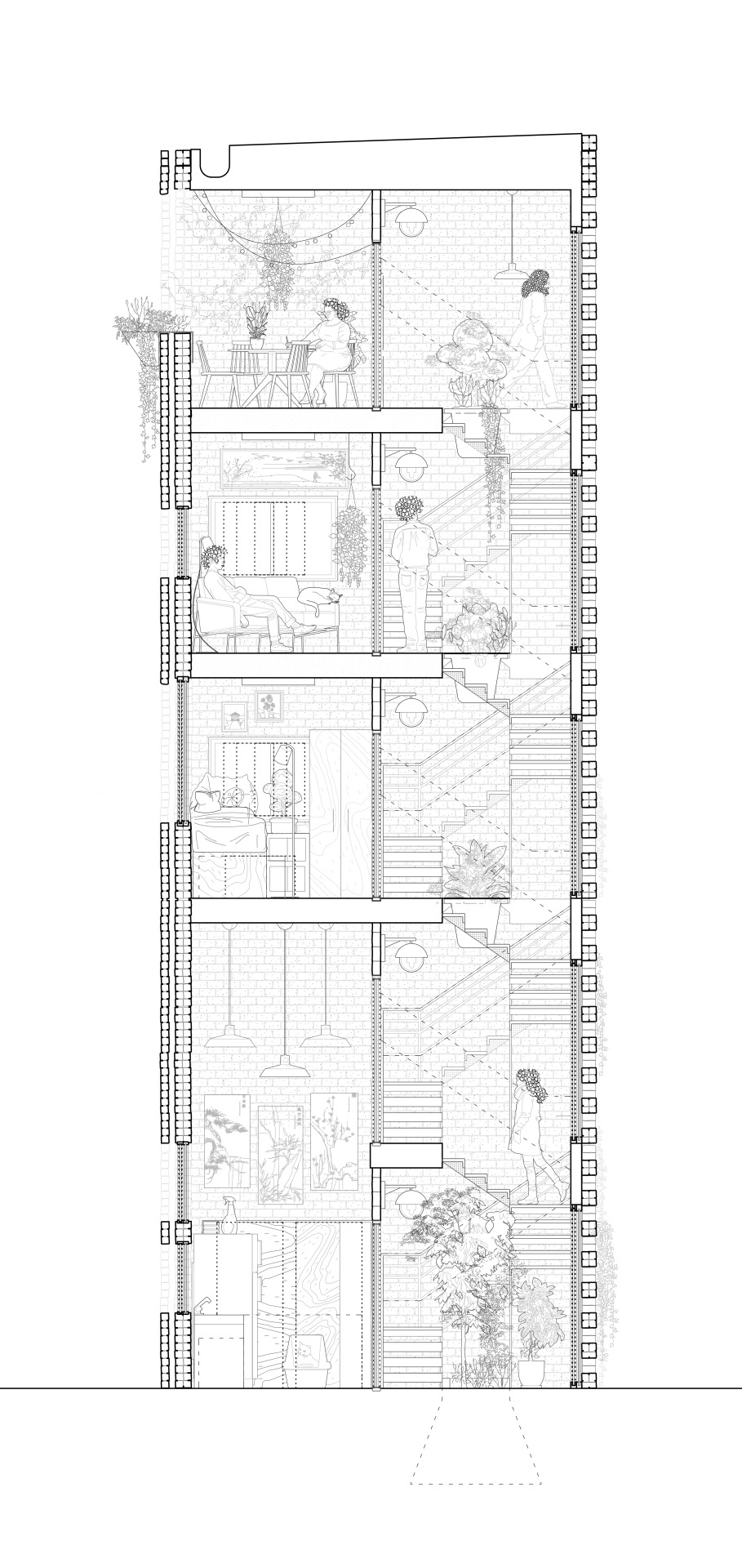

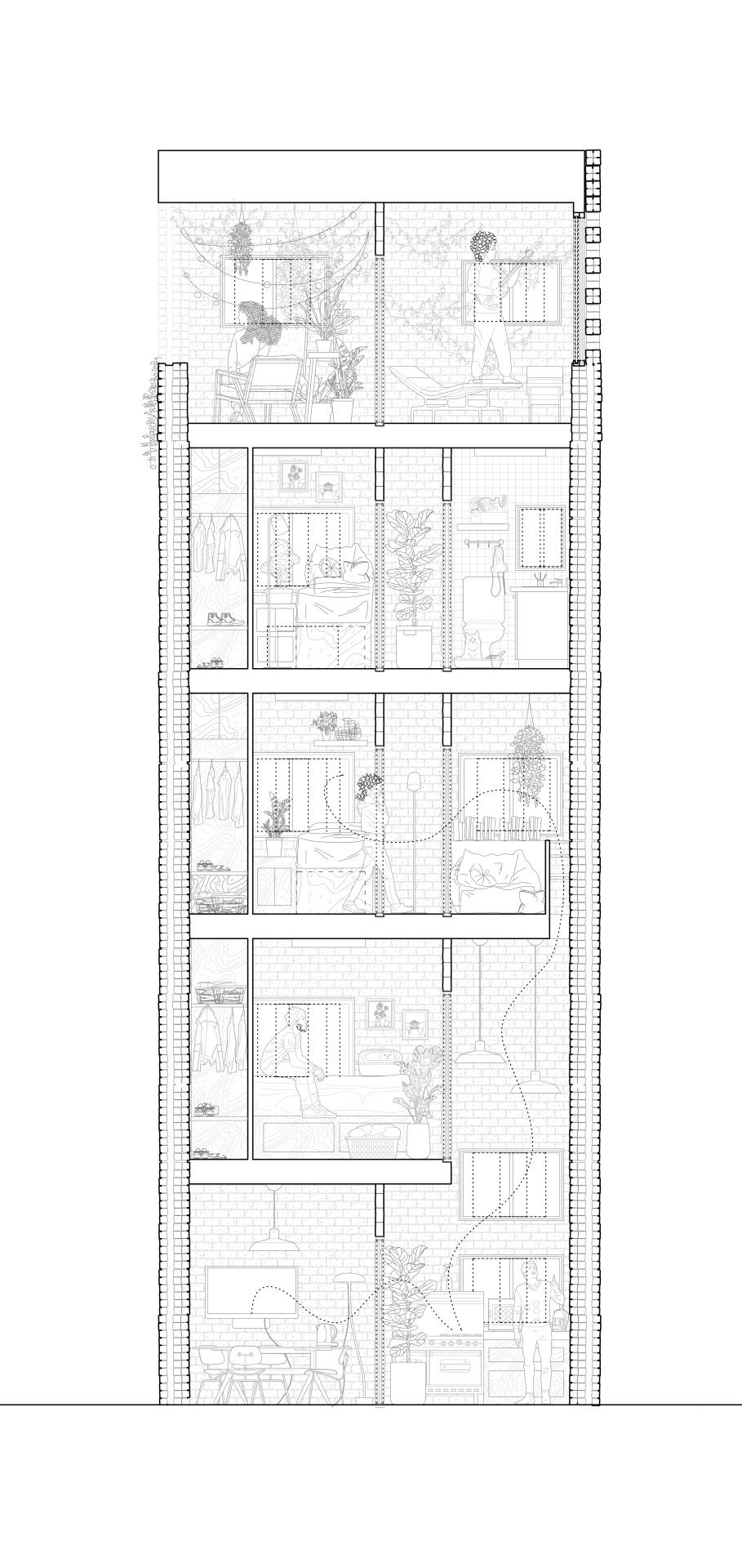

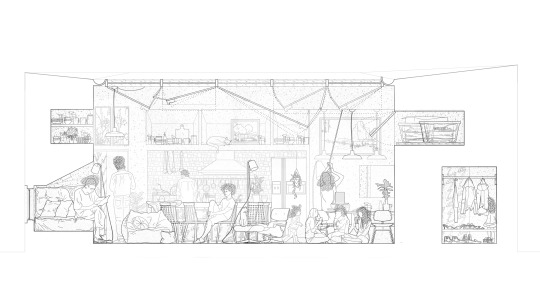

vertical home

fall 2023

prompt

> tower habitat with a footprint of 24m2 per floor with stacked repetition logic for 5 college students

resolution

> thicken quadrant boundaries for access and line them with rails, so cells may be isolated or merged as wall panels are slid across.

0 notes

Text

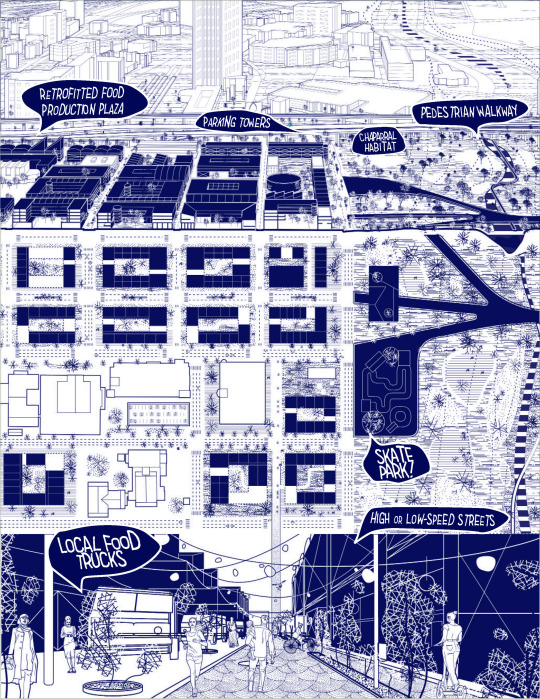

downtown los angeles urban masterplan

fall 2023

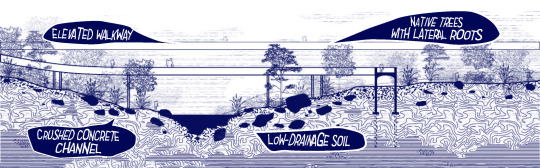

This proposal reconsiders project boundaries and demolition plans, favoring retrofitting and adaptive reuse over demolition. A former air duct factory in the northwest corner becomes a branch of Homeboy Industries, an LA-based gang rehabilitation food production organization. This creates a culinary plaza with food trucks, hydroponic gardens, and volunteer distribution sites to address LA's food insecurity crisis. Emphasizing affordability, mixed-use housing options range from courtyard units to townhome bars, countering gentrification ousting of the working class. Car streets exist along two axes and the site's perimeter, with condensed parking towers in high-traffic areas, while remaining roads prioritize pedestrians and cyclists.

Demolition most radically occurs on the concrete shell of the Los Angeles River. It involves crushing the and distributing the material along the riverbank to encourage water retention in sandy soils. Native oaks, cedars, and shrubs are introduced to withstand the rocky terrain, contributing to river naturalization.

Residential +/- 65%

35 dwellings/acre and 70 dwellings/acre

Mix-Used +/- 30%

Hotel +/-5%

Site-appropriate Parking Strategy

0 notes

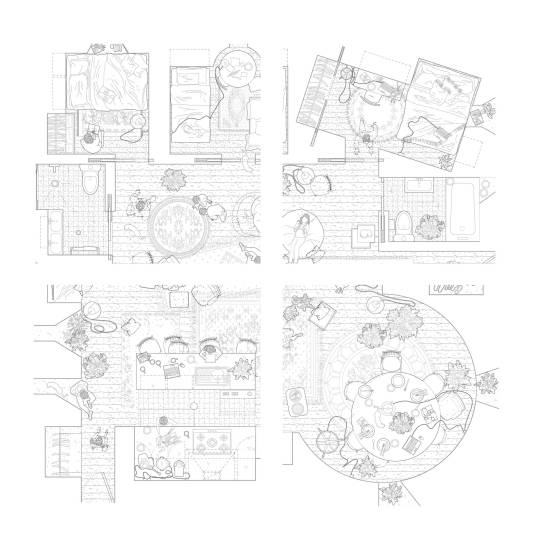

Text

horizontal home

spring 2022

prompt

> single floor/1200ft^2 home for a family of 5

resolution

> reduce privacy as only a utility to be condensed and thickened into a perimeter wall, and liberate the rest of the home openly and languidly.

0 notes

Text

rolling paper shelf for TuSA

fall 2023

Oblique drawing and photograph of a plywood plotter paper holder

for Tulane Graduate School of Architecture's Digital Output Lab.

1 note

·

View note