Text

On Consumption and Blackness and Sustainability

It used to break my heart when I couldn’t obtain luxury items I heard rappers and singers promoting in their songs when I was younger. Seeing magazines filled with suggestions for a “Perfect Fall Wardrobe,” or the latest summer accessory that every “it” girl needs often left me feeling a palpable distance between my reality and the reality that these glossies were painting. I had aspirations of being a woman, a powerhouse, who could afford luxury items and lifestyle. I remember receiving the coveted Tommy Hilfiger overalls with the logo on the straps when I was in middle school. My mom found them on sale at a local department store. I then learned that TJ Maxx or at the time, Value City, had name brands for much less. My mom told me these items were real, just made wrong, or were possibly discarded by the brands themselves for imperfections. I didn’t care. The logo (and style — I did have some discernment) was really all I cared about. But why? Why did I feel more inclined to want clothing that bore a logo from a white designer who most likely did not have me in mind when they contemplated their target customer base?

I ended up shedding my materialist tendencies, opting for more individuality in my fashion sense when I began high school. This was one of the most, if not the most, transformative time of my life. I received a full-tuition scholarship to attend a prestigious boarding school in Newport, R.I. for grades 9-12. This school was a far cry from my very working class upbringing in Dayton, Ohio. I remember feeling the deep pangs of sadness when I realized I probably would never own a louis vuitton bag at that age, let alone, the extravagant lifestyles my classmates enjoyed by virtue of being born into a family with generational wealth. So I scoured the counterfeit market and even lucked out on a knock-off Louis Vuitton logo bag my junior year — a gift from my uncle whose business ventures ranged from shady to shadiest.

After being called out for having a fake bag, and honestly not caring, I began looking for more counterfeit bags to collect. Eventually I ended up with about three more before I retired the fucks I was giving for keeping up with the Jones (I mean the Kardashians). You see, I wasn’t the type of kid who ever owned a pair of jordans, or the latest anything. I was the type of kid who put together looks and if an expensive item happened to be a part of the lot, I needed to have it. I thought that by checking my materialism to a certain extent, separated me from my friends who were really slaves to trends, and also broke.

It was the sadness of unattainability that marked my transition within my consumption habits. No longer was a serving logos, I was into serving looks. I even considered my sense of style better than anyone who appeared in head to toe name brand, because I considered them to be lazy. What I was actually doing, was assuming the role that so many in this space assume when trying to distinguish themselves from those of a lower class. I was unaware that I was perpetuating a classist, colonial construct by attempting to parse out my sense of self from my consumptions habits. The truth is, Black people, those who are descendants of formerly enslaved Africans, in particular, will never be divorced from consumption and capitalism. WE WERE CAPITAL FOR MORE THAN THREE CENTURIES (STILL ARE!!!). And the only way a system built on the exploitation of people’s labor and resources is to introduce tactics of scarcity. Slavery existed because we were not granted the ability to consume BASIC THINGS. So when you have your conversations about sustainability and discuss anti-consumerism in the same breath, remember how nuanced that argument actually is. When consumption is inextricably linked to liberation, why should we stop attempting to obtain the nice things we want? I know there are more caveats to this inquiry, such as financial responsibility, materialism, and the promotion of toxic behaviors, but we didn’t create the system that we have been expected to survive in. If your sustainability talks do not address dismantling a system that got us here in the first place, are you really talking sustainability??

1 note

·

View note

Text

Failures, Part 1

The walls of the room where study hall was held were decorated with engraved plaques bearing the names of those who achieved honor roll all four years and those who ascended to school prefect (student body president) status since the school’s inception in 1910. I was prepared to end up on both plaques, however, I only became immortalized on one: Senior Prefect. The year I was elected to represent the entire student body, I had experienced the most failures I had ever encountered in my adolescent life. The summer prior to Junior year, I was chastised by my father for “running up” the family cell phone bill. I was one of the few sophomores on campus to receive a cell phone in my school the year prior. The aftermath of September eleventh and the proximity of my boarding school to New York, deemed it necessary for my parents to be able to reach me in case of another catastrophic emergency. I didn’t know that two month of unanswered calls to the Bahamas, where my new boyfriend lived, would incur such a steep charge. “Don’t they have to answer the phone in order to charge you?” I asked my dad earnestly. “Hell no,” he said partially laughing through the new financial anxiety I caused him. I found no humor in the unanswered calls. As someone who has a knack for getting answers to her inquiries the sudden cooling off of the moderately passionate relationship my boyfriend and I had metamorphosed me into a hog sniffing out truffles of truth from him.

Our differences were palpable. He was from the Bahamas, born to a black father and a white mother. He had a thick Caribbean accent and a LOT of energy. In fact, it was this same energy that initially repulsed me once he arrived on campus Sophomore year. Our class size doubled that year, as they did in years past, quickly expanding our class size from 40 to 80. Dustin had soft curly hair that was closely cropped the way all the black boys hair was when they first arrived. He too became one of my braiding clients by the time we graduated. Despite his obnoxious energy, he was incredibly smart. He arrived on campus accompanied by another Bahamian black kid who also was recruited to play for our school’s Varsity Soccer team. I wanted him. He was tall, with defined features, also mixed, but with a more demure, mature, commanding presence. But my friend Jamila, (no not the first one) quickly claimed him as her crush. And even though he quietly flirted with me on occasion, I placed him on the shelf of possibly destructive decisions and left him there in order to preserve my friendship with her.

Dustin, on the other hand was very available. No one wanted him. He was shorter than his comrade. and had no interest in enunciation, or whether people understood what he was saying. My advisor, a dominant black man from D.C. took more of my life under his wing than I was comfortable with, including my dating life, setting the two of us up one night through eye brow raises and suggestions that Dustin walk me back to my dorm after we finished watching a football game at his house. A weekly ritual for all of the black kids on campus. My advisor’s behavior wasn’t questionable to me until I later became aware of his battle with alcoholism and other health issues my senior year of college. Dustin walked me back to my dorm only three times before we went on our first date. Winter formal was quickly approaching and I was all too familiar with the coldness of singledom AND winter on the hilltop. So I looked at him, really looked at him. I studied his features, the way his eye lashes curled long and full haloing his deep brown eyes. He often had a grin on his face, which cause the creases of his eyes to deepen, forecasting wisdom to come. His lips were plump and round, pink with promise and his teeth sparkled white beyond them. His skin was smooth and caramel and the more I studied him, the more I wanted to devour him. He was smitten with me from the very beginning and told me often. We maintained a sweet loving relationship, which involved some moderate dry humping at times, but for the most part was pretty cerebrally focused. We connected on our differences and he made me feel safe when he really tried. The night of Winter formal I was on day three of a stomach bug. The nurses released me from the infirmary so I could wear the salmon colored satin A-lined dress I begged and pleaded my parents to purchase for me a few weeks prior. It was a $180 dress. Despite protests by my step mother and step sister about the exorbitant price of the dress, my father and mother contributed to purchasing it for me.

Winter formal was our version of prom, except it was open to all grade levels, 9 - 12. This is the first time I became aware of my lack of genuine wealth. When conversations about chipping into the rental of a limo surfaced or the cost of dinner at one of the many expensive restaurants in Newport, my heart rate sped up and a cold sensation coated my skin. “Don’t worry, I’ll pay for it,” Dustin said, sensing my insecurity amidst the group discussion. I loved him for knowing me that way.

The night of formal, I tried to enjoy my lobster bisque, but all I could think about is how much I had to shit or vomit. Dustin also sensed my discomfort and hailed us a taxi back to campus. We were at an advantage because none of the adults on campus expected students to return so soon, so we ventured down into the basement of the dorm we both shared (girls on one side, boys on the other) where a palate of blankets, a couple of long stem roses, and a bottle of sparkling apple juice greeted me. I knew then that he was signaling to me that he was ready to have sex. But the uproarious bubbling within my gut cautioned him. “Awww! This is so nice baby, but I feel so sick.” I studied his eyes for disappointment and was met with none. Without question, he walked me to the infirmary and lied to the nurses that he had in fact caught the stomach bug too and needed to be admitted as well. The next morning I woke up to him laying next to me in the other twin bed in the room, awake, at peace, in love.

My confusion peaked when I saw him arrive on campus Junior year. I was both angry and excited to see him. The anger dissipated when I got close enough to hug him, ready to forgive him for not answering any of my calls for the entire two months of summer break. But the hug was not returned and his eyes sparkled no longer. In fact, I had to maneuver my head just to get him to make eye contact. My heart raced, my palms began to sweat and coldness once again coated my epidermis. But this time, he didn’t care. I knew that this was rejection, but had a hard time accepting that it was HIM who was rejecting me.

I broke down, publicly, one day as I was walking back to my dorm room that Fall. The black boys made a habit of hiding member’s of our group’s belongings after lunch, sending the poor unfortunate mark of the day frantically searching for their book bag, or purse causing a malicious comic relief for the culprits. I was usually a neutral party to this behavior, but became the mark that day. “WHERE IS MY STUFF?!” I screamed at them in the main common room. They snickered and feigned ignorance, some even ignoring me. I felt my breath quicken and watched their eyes dart back and forth to each other, knowingly, stifling their laughter. I repeated myself multiple times, each time escalating a decibel, eventually graduating into an all out frenzy. “WHERE IS MY STUFF?!” I felt the tears begin to accumulate at the base of my throat. My voice cracked and I started to smack each of them on the back of their heads. “Yo chill chill,” my friend Will, a black kid from Flatbush and someone I really deeply loved, repeated in a way that didn’t help. It was Will this time, who sensed that the joke was going too far and that I was becoming enraged beyond the location of my belongings. He retrieved my brightly colored tote bag from behind the pool table and I snatched it indignantly. I attempted to swallow the tears, a skill I thought I had mastered in the three years of navigating boarding school thus far, but my swallows were to no avail. The tears erupted uncontrollably from deep within my gut and I ran back to my dorm room through the relics of the school’s white male-only past, down the dark corridors and eventually into the sunshine of the courtyard joining the dining hall and common room with the driveway to my dorm. I didn’t make it into the dorm, collapsing in the driveway, emitting loud wails akin to a woman in labor. Lamaya, a Dominician senior and day student from Providence, recognized this type of breakdown and rushed to me, picking me up off of the asphalt and gave me a pep talk. I don’t remember the details of her diatribe, but I do remember was effective enough to encase my heart in the acceptance that Dustin just didn’t want to be with me anymore.

News of my breakdown spread within minutes to my friends and they came to my aide with solutions. Madeline was among the flock of both white and black girls ready to disarm my ex of any type of leverage he had in our social circle, culminating in a very satisfying act of smashing a glass pendant he purchased for me the previous valentines day. Though, I kept the poem he wrote about me and performed in my honor in front of the entire school the day he gave me the necklace. As an adult, I still read this poem, because again, he understood me.

I later learned that Dustin realized he was actually in love with his best friend back home in the Bahamas over the course of our nine month relationship and solidified his love for her the summer of unanswered calls and unrequited love. I couldn’t fault him for falling in love with someone I even grew fond of through his colorful stories of life back home. I did, however, harp on the fact that I was a black girl who was left by a black man for a white girl, a scenario I always heard my mother condemn — a scenario I would see repeated by the men in my family throughout my life. Though his coldness never subsided, resulting in him blocking me from even connecting with him on social media as adults, I learned that he eventually married this girl.

After the breakup, I threw myself into auditions for the Spring Play. This was my lane. With absolutely no theater or acting experience, I unseated the most beautiful senior from her title as the lead role in every Spring Play since I stepped foot on campus. The first year, I was cast as the pragmatic, but fed up wife in Oscar Wilde’s an Ideal Husband. The following year, the bustling, naive princess in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. The breakup added more weight to my need to land the lead role that year because I wanted him to be forced to look at me, under lights, talented, poised, beautiful — a reminder of his mistake. The leading role audition monologue was meant to be delivered by a character who was grappling with slowly losing her sanity amidst the backdrop of chaos ensuing in her own home. I evoked the only example of crazy I was aware of: crackheads. When it was time for me to take the stage, I got into character by frantically scratching my neck, and arms and elbows, moving about the stage in a torrid pace, randomly stepping upstage and downstage, sporadically shouting the lines I memorized. By the end of my audition, my theater teacher, also the director of the spring play, seemed simultaneously confused and let down. A tall brunette with more academic features followed me, delivering the same lines with a slow, distant, much quieter, ease. This is how WASPS do crazy. My theater teacher seemed relieved after Britton’s audition and I retreated back to my dorm room, chanting the same prayers my mother chanted when she was anxious, under my breath.

Squeals of excitement erupted down the hall from my room and I could hear the joyful chatter of my dorm mates across the hall. I opened my door to see what they were so excited about and upon my transition beyond the threshold of my neighbor’s door, I was stopped with the ere of unwelcoming. I saw Britton on the bed, surrounded by four other girls I was not very close with, all looking at me with sympathy. I knew then, but made her say it. “You got the part?” “Yup!” she said, re-igniting her excitement, this time, not caring that it was a punch to my gut.

I tried to swallow tears once again, but they erupted bringing forth a newly familiar pang of rejection and a simultaneous icing of my veins. I was cast in the ensemble of the play, with a role that required only two lines. I also had to wear an ill-fitting frumpy nun costume for my role. Obviously this was the opposite of the vision I had for my revenge on Dustin. But sweet satisfaction showed up in a different way by the end of junior year.

At the urging of my dorm mates, dorm parents, friends, and non-friends, I decided to enter the race for School President. Only three black guys held this position since the school integrated in the 60s and only one other black young woman. I would be the second black female student body president. My campaign slogan was inspired by R. Kelly’s (cringe…i know) Remix to Ignition: “It’s the remix to ignition, hot and fresh out the kitchen.” I’m pretty sure that’s all I wrote on my posters, so you can imagine my utter surprise when my name was called during the famous all-school assembly at the end of the year.

And as if torn from a page of my personal vendetta book, Dustin bolted towards me once the assembly concluded and asked me to be his girlfriend again. I wasn’t sure if he was serious, but I had already moved on. The glory was mine and I was prepared to bask in it for the entire year, single.

0 notes

Text

Looks

Making time to reevaluate childhood trauma as an adult before its too late. Sometimes I feel like i’m a passenger on a speeding jet, ascending into the air, my life, the landscape beyond my window. Everything feels like a blur. As I am working through upending fears to create joy, I have decided to write through this process as best I can. Feel free to leave feedback. Or not. Today’s fear: Looks. Read more below.

_______________________________________________________________

I always took pride in being different. Standing out amongst the crowd whether it was because of my height, foot size, or sharp wit. I never stood out for the things I really wanted to, like looks. I remember once agonizing over the fact that I didn’t have lighter skin like my mother. We were leaving a grocery store parking lot when she stopped the car abruptly, “your are beautiful! Don’t ever discount your beauty,” she said with the same tone of command she used to shift the Buddhist gods into protection during her prayers. There is this theory that the Buddhist gods offer protection to those who inspire them to act through prayer. My mother had a way of activating these gods. Though deeper study of this religion, has revealed to me that these gods are actually just synonymous with the unspoken spiritual energy of human beings. Her commanding voice when it came to protecting her child made me feel simultaneously comforted and insecure. I learned early that the world offered little protection to those who looked like me (regardless of age) and that my mother would have to pray extra hard to make sure I didn’t fall victim to an accident or an act at the hands of someone who didn’t quite see the value of my life. I also learned at an early age that she, nor her prayers would be able to prevent either one of those things from happening to me.

The first time I was asked why I didn’t wash my hair everyday I was three weeks into boarding school. I intentionally showered at night to avoid the morning rush of blonde haired, blue eyed girls in the shared bathroom. I also showered at night because it was my only bit of welcomed solitude amongst a flurry of freshman welcome events. There were 40 of us admitted to St. George’s that year — Twenty girls and twenty boys. I was the only dark-skinned black girl in my class. And apparently the only one who had never gone to sleep away camp. The boys had more company, counting four amongst themselves with deeper hued epidermis and tightly coiled hair that I ended up knowing intimately due to the absence of adequate barber services for black boys in the traditional seaport town of Newport, R.I. I doubt the Vanderbilts contemplated the need for such services when they erected one of their many mansions in the popular seaside town decades prior to our arrival. Regardless, I honed my hair braiding skills (for a ten dollar fee) over the next four years and my retort to the inquiry of less frequent washing. But the first time I had to answer this question, I paused. Quite frankly, I had never really thought of washing my hair everyday. I just knew I didn’t have the time, nor the tools to tackle my chemically processed strands the way my hair dresser did back in Dayton, Ohio. “It takes me a long time to straighten it after I wash it. I have to go to someone special to do it.” A look of confusing and eventual acceptance swept across her face and that was that. This was the first time I understood that I would have a lot more explaining to do these next few years, and the last time I would make the mistake of showering in the morning that semester.

My inquirer’s name was Madeline. She was a 5’4” thin girl with large green eyes. Her hair was wavy and the blondest I had ever seen on a person outside of an albino person. She was strikingly beautiful with facial features of a baby leopard. She hailed from somewhere in the south and also somewhere from the north as the result of divorced parents. I related to being pulled in opposite directions and the sweet reprieve of being away from the rigors of delicate emotional labor to prove to both parents they were loved equally. We became friends quickly and she invited me into spaces i otherwise may not have gained entry into. Like Whip-It sessions after “lights out” in the dorm. Despite her invitations, the acceptance of others who felt comfortable with her was not afforded to me. Maybe it was because I never did drugs with them.

I lived with a Latina from East New York. We quickly realized we were made to share a room that year because we were the only two racial minorities in the class of boarding students that year. We hated each other. I often came back to my dorm room with pants, underwear, and pens stolen only to find them in her dirty clothes hamper once my theory that she might be the culprit surfaced within the first three weeks of our arrival. Our school was on a hill top, surrounded by three beaches. Even amidst this picturesque setting, the details of my experience were littered with conundrums often stemming from the fact that I apparently had a lot more to lose than my classmates. Walking a tight rope of assimilation, which so far, wasn’t boding so well, and the intrinsic reflex to “knock a bitch out,” became a daily exercise. The last time I heard her speaking to my boyfriend in a flirtatious way while I laid above her in our bunk beds, I snapped. “What the fuck are you really doing?” I asked harkening back to my days in Dayton when I had to have both bark and bite to fit in with my classmates whose vocabulary’s were less evolved and enunciation was not as refined. “You talk white,” became a mantra for them before I stopped speaking and lunged at the main culprit of the group in fifth grade resulting in detention for weeks. This was also the first time I realized, I circumvent logic when catalyzed by anger. And the last time someone in that school told me I talk White.

I jumped down from my bunk bed and began a series of expletive ridden diatribes, somewhat still trying to insert a bit of stern compassion, or evoke some from her. We were, after all, the only minority girls in our class. She laughed. I got louder. Soon my dorm parents, and a few of the girls on our floor were crowded outside our dorm room. She remained silent and as I finished that good ol’ cussout, I became uncomfortably aware of the fact that I now had an audience and they weren’t coming to defend me. Tina, my roommate had more palatable features. She was light skinned with thick dark eyebrows, a chiseled nose and full lips. In fact, all of the black guys in the school complimented her on her looks whenever I was around and I’m sure more often when I was not. My boyfriend at the time was a tall brown-skinned junior from Pine Bluff, Arkansas and he spoke so slowly and with such a deep southern drawl, I often questioned his intelligence and whether he was worthy to have been afforded entry into our school. He too gained admittance, as many of us did, via a financial scholarship. I dumped him on Valentine’s day, just three days after this altercation. It also happened to be his birthday. My dorm parent, a Chinese man from Taiwan had just moved his family to Newport two months prior. His name was Mr. Wong and I often participated in singing a song employed by one of the more rebellious blondes on my floor whenever she protested his authority, which was often. All I remember from the song is the melody and instead of saying “the wrong way,” we substituted his name: “the Wong Way.” He laughed with us until it wasn’t funny anymore. Unfortunately for me, it had stopped being funny just before Tina incited this debacle. “Uh Miss Megwere,” I am giving you a green card. I could hear gasps from the growing crowd outside of my door. Green cards were one’s ticket to entry into boarding school’s version of detention— Early Morning Proctored Study Hall. And despite the cajoling of my rebellious blonde friend, Abagale, I in fact was the first to receive an infraction for my behavior in the dorm. “But, SHE IS TALKING TO MY BOYFRIEND ON THE PHONE AND FLIRTING WITH HIM!!” I pleaded for logic to infiltrate his heart and that he would renege on the offer to admonish me into early morning study hall, but the insignificance of teenage girl drama deafened his ears. “No no no, I am giving your a green card. Everyone back to your rooms and lights out!” The door closed and Tina wished me an ironic “good night.”

0 notes

Text

Crashes

Making time to reevaluate childhood trauma as an adult before its too late. Sometimes I feel like i’m a passenger on a speeding jet, ascending into the air, my life, the landscape beyond my window. Everything feels like a blur. As I am working through upending fears to create joy, I have decided to write through this process as best I can. Feel free to leave feedback. Or not. Today’s fear: Crashes. Read more below.

__________________________________________________________________

I remember a loud crash. My head was resting on my mother’s lap as we both sat on the floor. Her french tip acrylic nails tracing calms down my back, repeating affirmations of better days to come as if writing sentences over and over the way ornery pupils do for punishment. Goosebumps emerged from my skin filling my body and mind with comfort. belonging. A pervading knowing that I was loved. The crash happened during my mother’s evening prayers, a ritual she embraced just 12 years prior to my arrival Earthside. It was 1991 and I was five years old. Glass shattered in our living room and all I could see were headlights. Our elderly neighbor, one my mother was never really fond of, accidentally pressed her gas instead of her break and sped into our front porch. “She’s a bitch,” my mother would say, ignoring the social mores of swearing in front of children through her feigned smile every time we pulled into our driveway, under the watch of this neighbor. She never returned the smile. The matriarchs of my family rushed to our aide that evening. I stood on my favorite stool, hunched over the kitchen sink, dry heaving from the fumes of our neighbor’s mangled Buick LeSabre. A few of my braids affixed with plastic, colorful beads, tapped the side of the sink escaping my grandmother’s gentle grasp catching remnants of my spit. The patriarchs remained outside with the police.

I’ve only a few memories in this kitchen. Most of them revolving around the swift need to diffuse tension. Despite the frequent goosebumps offered to me by my mother’s touch, my stomach held memories of a different sensation, prompting my uncle to offer me ginger supplements often. Apparently I worried a lot. My parents’ arguments filled the home as I watched them between banister posts on the stairs. My mother humorously recalls “losing it” on my father a few times, once so badly she chased him out of the door and down the street with a knife. The other times she would grab the closes hard object and hurl it at him out of frustration and exhaustion. A hairdryer is the only inanimate object my father fondly recalls being thrown at him.

My parents lived together for only one year of my life. I met my father when I was 4. He was released from prison shortly before my 4th birthday. The first time he drove me to pre-school, without my mother, I screamed the entire way there. Later that day, I fell off of a swing and cracked a tooth. Bloody and all, I knew the first person I would see outside of pre-school staff would be my mother. I was right.

The second crash occurred a few months later. My mother and I rushed to a Buddhist meeting, skipping morning prayers. An elderly woman in a very big green car rammed into our toyota sending it careening into on-coming traffic and eventually on the lawn of a small law firm. I was secured in a booster seat in the back. Somehow I managed to hold onto my barbies the entire time. I don’t remember fear. The door closest to me was too dented to open, so I crawled out of the opposite window into my mother’s arms. No one from the law office came to check on us. We were in the “white part of town.” They did let us use their phone to call the police, however. My mother never skipped her morning prayers again.

The green paint from the woman’s car streaked the gray and silver dents on our car, which eventually stayed in our driveway. We couldn’t afford to get it fixed. Every time we approached our home, I saw the “good side of the car first, feeling a flash of hope that it was fixed, but at we got closer, I would spot the side that was impacted by the wreck. And I would grow instantly cold. Even in the summer. This is when fear began to set in for me, for just about everything. If we parked next to a wrecked car in a parking lot, or pulled up next to one at a stoplight, my 5 year old body would tense up, my heart would race, my stomach would churn and sometimes I would cry. My mother, unaware of my newly-acquired phobia, would repeatedly ask me what was wrong. I don’t remember what I told her, but I’m sure it was, “nothing.”

The third crash happened outside of my presence. My grandmother, a new widow and our primary support, was apparently leaving the parking lot of a gas station when someone slammed into her Lincoln town car causing significant damage to the anterior of the car. She came home shaken up, but quite unaffected in my opinion. I, however, feared going into the garage everyday until the car was fixed. I noted the way my grandmother and mother handled these situations. Ones that seemed to completely jar my sense of security seemed nothing but blips on the radar for them. It’s worth mentioning that I never saw either of them cry after my grandfather, my grandmother’s husband and my mother’s father passed away the year prior.

He was a pervading force in my life. My first father. He made me waffles, eggs and bacon in the mornings and we would discuss fishing, books, and my mother - his favorite child, though he never expressed that verbally to her. In the evenings, curled up in his lap, I would often stare at the gold playboy bunny symbol that dangled from one of his many gold chains. Eventually, I would find his Playboy stash and marvel at bodies I simultaneously wanted to devour and admire. His death left an imprint on my psyche. Men leave.

The day I won the kindergarten spelling bee, my mother was absent. My grandfather met me backstage with a bouquet of flowers and drove me home. The garage door opened shortly after and my mother also walked in, greeted with her own bouquet of roses i excitedly presented to her with a smile on my face. “CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR DIVORCE!!!” I yelled à la Oprah, with arms outstretched in power stance. She thanked me bashfully. “Glad that’s done,” she said.

The year I turned 6 was an opposite year. Everything was different as if I had unknowingly agreed with some higher power to participate in 365 opposite days that year. You know, the kind where you wear your clothing backwards or days when the teachers dress up as students and vice versa. Except I wasn’t in on the joke. When I blew out the candles on my 6th birthday I wished for my grandfather to come back. He never did. Apparently my grandmother couldn’t get the image of his dead body slumped in his favorite chair during March madness out of her mind either. We moved from that house soon after. She, into a smaller, family-owned condominium across town, and my mother and I in a cute, run down two story home somewhat near her.

Although my new bedroom was twice the size of the one my mother and I shared in my grandparents’ home, I spent most of my time in my mother’s room perusing her fancy clothes and watching MTV and Nickelodeon on her personal television. My mother was a teacher during the day and a Jazz singer at night. I consider myself a “stage kid” because I grew up used to the daily grind of having a parent who worked two jobs, to which one I could accompany her, when appropriate. Her most consistent gig was at a restaurant near the airport called Shades of Jade. We would have to drive almost an hour to get there on Tuesdays and Thursdays. On those days I would meet her at home from the bus stop and hop in the tub to wash off the day. She would lay out my outfit for the evening and I would watch her apply vibrant shades of red lipstick, black eyeliner, and blush to her caramel-colored skin. She was always a beautiful woman, but on those nights, her beauty was especially enhanced. Her charisma and stage persona always made me feel a little small. Like I could never do what she’s doing, despite her encouragement for me to join her on stage for what she thought would be cute mother-daughter moments. Also, tips were more abundant when the singer’s child was present. But I never acquiesced. A retired white couple befriended my mother during her residency at this restaurant. They were regulars and often bought me extra shrimp toast and egg rolls to eat while I sat through my mother’s four-hour set. They were artists themselves and often brought writing and drawing implements to keep me busy. I loved to draw. I loved to write.

The fourth crash happened the summer before my first year in boarding school. My mother had recently accepted a job in Las Vegas after explaining to me that “she had exhausted the Mid-West circuit (for performing).” She was ready to regain her sense of self and step even more fully into the person she was before I came along. She met my father before moving to New York after graduating from Central State University in Dayton, Ohio. They remained in contact during the 13 years she spent performing with some of the biggest names in music at the time, Chaka Kahn, Prince, Rick James, etc. One divorce under her belt and the trauma of watching her first cousin and twin flame die from AIDS sent her back to Dayton, our hometown, for a change of pace and more stability. “I didn’t want to be no damn teacher,” she’s often reminded me. But when my father was convicted of a drug offense, she was left with no income and a newborn baby. “I had to do what I had to do,” she said. My father remarried rather quickly after their divorce, their second my the way. My mother divorced him while he was in prison, perhaps as a way to regain a sense of control during one of the most chaotic times in her life. My step mother, a more simple woman who pragmatically sought stability through a government job she held for nearly 40 years, and a teen mom, reminded me of my mother, only in looks. Both had short hair, channeling Anita Baker. Bother were the same complexion. Both were consistently aggravated by my father.

On the day of the fourth crash i was brewing with anger in the wake of one of the most explosive arguments I had ever had with an adult - my father - the night before. We sat in his black GMC truck arguing about whether he should have to pay for the laptop computer i needed to rent for boarding school. The $400 rental fee may seem like small change for many, but for my family it meant the difference between being able to afford necessities versus something that seemed rather extravagant at the time. “You don’t need a computer. You can use a pen and paper.” I retorted with the fact that most of our assignments were disseminated via computer and that I would be at a significant academic disadvantage without one. “Well why can’t your mother pay for it? Child support doesn’t cover these things. I am not obligated by the court to pay for a computer. What is your mother using the child support for?” “BILLS!!!” I responded at the top of my lungs, I’m sure followed by many expletives I brazenly employed — a hallmark of my communication tactics with my parents. I don’t hold my tongue. The morning after, I decided to skip church, but my stepmother, a faithful woman at the time, guilted me into attending church that day. I was always annoyed by her driving. She always stopped too short in my opinion, driving too closely behind cars that were in front of her. In fact, I often questioned her depth perception. This day was no different. While in traffic she stopped short and actually tapped the red pickup truck in front of us, but then, “BANG!” The loudest bang there ever was. The cereal I was eating from a cup flew out from between my legs and scattered all over my white pedal pushers and the dashboard. My step mother checked the rearview mirror and all we could see was the red trunk of her Mazda 626 mangled. “My CAR!” she exclaimed then checked me to make sure the cereal milk was not, in fact, blood. The first responders to the scene asked me a few questions then looked at me sympathetically. “It happens,” the firefighter said to me pointing to my wet pants. “It’s MILK!” I said, curing the embarrassment he was transferring to me from his assumption that I had wet my pants.

I received a few hundred dollars from the settlement from that accident and went to the nearest Walmart to purchase snacks for my dorm room. I had been accepted to boarding school the year prior as the result of my misunderstood independence. Just a year prior to that, when I was 12 years old, I met one of my mother’s favorite students, Jamila. She had the longest hair I had ever seen on a 100% black girl, sort of like Aaliyah. She carried a confidence that I often tried to mimic, but could never really nail. She was tall, beautiful, and her eyes sparkled with new beginnings and an “other side of the train tracks” aura. My mother introduced me to Jamila by reminding me that she was attending boarding school for high school. I had no idea what boarding school was so I inquired about her experience as if her little sister, ready to hang on to her every word. “You will really like it. You should apply,” she said. Following that conversation, I read my first (and only) harry potter book and another written by a black woman Buddhist member my mother had recently befriended. Both stories, one fictional, the other biographical, told the story of boarding school with the same amount of magic. Except Charlene’s magic was navigating an all-white institution as one of the first black students to integrate her historically white male boarding school. I saw myself in both characters. I saw myself in Jamila. So I decided that I would pursue the opportunity to apply to boarding school via a feeder program for inner city youth.

A few months, lots of judging from my family who thought my mother, father and me were crazy, many re-writes of handwritten applications and essays later, I was in! Five out of five boarding schools accepted me, but only one offered me a full-tuition scholarship, Jamila’s school, St. George’s high school in Newport, RI. The first time I visited campus I felt goosebumps, like the ones my mother’s nails caused. For the first time in a long time, I was fearless.

0 notes

Link

My Newsletter is available now. Click the link above to read it!

#whitneyrmcguire#sustianablebrooklyn#fashionlaw#attorney#new york attorney#music law#art law#blackwoman#womanownedbusiness#WOCowned

0 notes

Photo

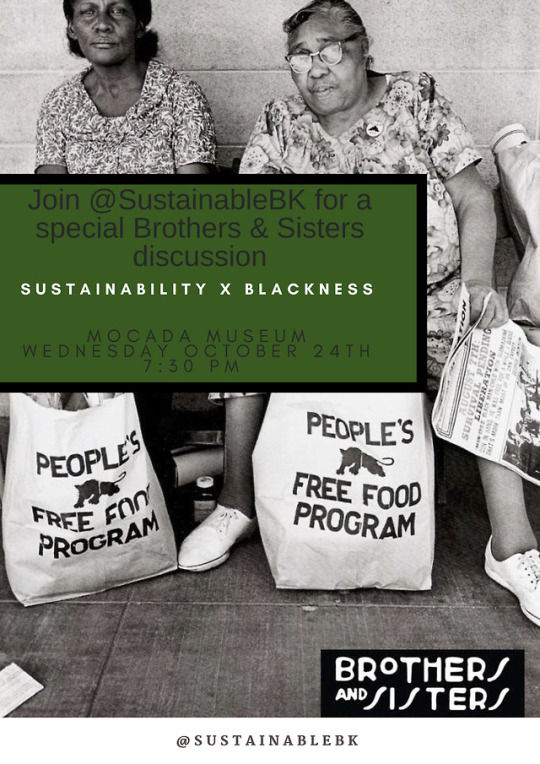

I am so proud to have moderated my first event with Dominique Drakeford of MelaninASS as co-founders of Sustainable Brooklyn (@sustainablebk).

We are beyond thrilled to have had a successful 1st event discussing Sustainability x Blackness in partnership with Brothers & Sisters and @mocada_museum 🖤 The energy, various perspectives and abundance of love was something so magic. A key takeaway is that at the heart of sustainability is the intent to sustain life. We are feeling so inspired to learn, grow, evolve and most importantly share resources to create stronger communities! The time is now to cultivate sustainable solutions for future generations and we are excited to get this work started! .

.

.

Thanks to everyone who attended and also those who were there in spirit. A special thanks to our panelist @mslbetty@janinewins @solsipsnyc @melaninass. .

🌿Please DM is if you’d like to be included in our newsletter 🌿

.

.

.

#sustainablebk #sustainablebrooklyn#brooklyn #sustainablity #eco #green#community #blackgirlmagic #art #healing#wellness #blacksustainability #racism#colonization #voices #friday #friyay#weekendvibes #blacksustainability

0 notes

Link

I wrote this journal article in 2012 linking fast fashion and counterfeit culture to detrimental effects on human laborers and the environment. One year later, Rana Plaza happened.

When I wrote this article, I was enmeshed in, what I now realize, was quite a linear and myopic conversation about sustainability. These conversations were mostly dominated by white people. When any conversation is held amongst a group of people within the same socio-economic and similar education background, the perspectives of those with differing experiences are not considered.

Fast fashion has always been a progenitor of unfair labor practices. There’s just no way a $10 cotton shirt was mass produced without affecting someone or the earth. But fast fashion has also been a way for people with categorically lower socio-economic status to present themselves proudly, fashionably, affordably. I think the overarching argument that fast fashion = an enemy of sustainability is only considering the effects of this industry from those who never really had to necessarily rely on cheaper clothes. Is there a way for fast fashion to exist without harming the environment or human laborers? Is there a way to educate each other about purchasing fast fashion so as to reduce the volume with which these items are consumed? How can we evolve this thinking to create lasting solutions when fast fashion, a mainstay in our culture, doesn’t appear to be losing steam anytime soon?

I am posting this article so you can understand the trajectory of my position within the sustainability space, the questions I’m currently pondering and hopefully inspire some interesting discussion on the topic.

Oh, P.S. The IDPPPA (cka IDPA) did not pass.

#fashionlaw#fashionsustainability#sustainability#sustainablefashion#sustainable brooklyn#IDPPPA#IDPA#Rana PLaza#Fast Fashion#FOrever21#Zara#H&M

0 notes

Photo

Founded by Whitney McGuire & Dominique Drakeford, Sustainable Brooklyn (@SustainableBK) champions disenfranchised communities in the sustainability movement by dismantling colonized frameworks, while providing workshops, programming and resources across sustainability spaces.

Sustainable Brooklyn in partnership with Brothers & Sisters (a community Brooklyn-based monthly event series) is hosting an insightful conversation about Black Sustainability. With a special focus in the FOOD andFASHION spaces, we will share expertise from:

Francesca Chaney -food justice trailblazer and Sol Sips owner

Dominique Drakeford- MelaninASS founder

Lisa Betty -Fordham University PhD candidate, whose work centers on the politics of food security

Janine Hausif -the founder of BASYL, a socially responsible women’s fashion brand

DATE: Wednesday, October 24th, 2018

TIME: 7:30 PM

LOCATION: MoCADA (80 Hanson Place, BK NY)

FEE: POSITIVE ATTITUDE

HOSTS: Saada Ahmed and Jason Parham

#sustainable fashion#food sustainability#food justice#fashionsustainability#fashion#food#foodie#consumption#black#black women#black people#melaninass#fordham university#mocada#solsips#sustainable brooklyn#culture#change

0 notes

Link

I presented this workshop on sustainable fashion to design students in Las Vegas almost three years ago. I decided to make this presentation available for any readers interested in a visual refresher or an introduction to sustainable fashion issues and a few solutions. This link does not include the full text of my presentation, just the visual accompaniment. For the purpose of formality, all rights are reserved. Enjoy!

#fashionsustainability#sustainablefashion#sustainable fashion#fashion#fashion law#fashion designer#streetwear#environment#environmental sustainability#climatechange#climate change#2016#popular

0 notes

Text

On Black Breastfeeding Week

By Whitney McGuire

It’s Black Breastfeeding Week according to Instagram and I’m sad. I don’t want to waste time describing the sadness, and maybe that’s not even the right word to describe how I feel, but tears are welling up in my eyes and my heart aches a bit. I’m a black woman. I had a baby 4 months ago. I am not breastfeeding.

I don’t have time to entertain judgments, even those cloaked in support. And trust me, there are a lot. I’ve already lashed out on a woman for communicating the assumption that I stopped breastfeeding due to cosmetic reasons. Now that I think about it, I’m like, “so what if it was?” I only have time to be present - to see that my first child, who’s somewhat traumatic entry into this world (for me) revealed parts of myself of which I wholeheartedly am in awe.

Presently, I see flashbacks of endless pregnancy nausea (worse than morning sickness. I had that too.) and breastfeeding classes at my midwife’s office. The joyful expectation that I will be a great mother who breastfeeds her child for at least a year. A. Great. Mother. I learned latching techniques, different hold positions to make for a comfortable feed for me and baby, and an understanding that every woman can and should breastfeed her child. “Was my former co-worker actually hyperbolizing when she said she couldn’t produce breastmilk for both of her children as she broke down in the break room every other day?” I faded out of my inner questioning and listened to statistics being tossed at me from the breastfeeding counselor making it patently clear that the act by omission -- not breastfeeding your child -- is basically considered child abuse. It didn’t take long for my instagram explore page algorithm to catch up , depicting images of pregnant women, or women with young children, happy and glowing. I knew not to click on those images. I am pretty cognizant of strengthening my muscle not to compare. But sometimes I skipped my workouts. Sometimes those images brought me to profiles that inevitably revealed a woman with one or both breasts exposed and the back of a baby’s head cradled lovingly, happily sucking away. Images like this made me feel warm and proud. Like I was about to join a sisterhood of like-minded, revolutionary, strong women championing the normalization of breastfeeding. A few looked like me. Many didn’t.

After giving birth, a lactation consultant visited me the day before I was discharged from my 7-day stay. She sat on the foot of my hospital bed. I sat in a recliner nursing my new child. He was very small. He decided to come four weeks early. The consultant quizzed me. “Do you know why breastfeeding is so important?” I listed stats I’d memorized from my breastfeeding class and hours of prior research on the topic. I wanted to be a GREAT mom. I had already delivered via emergency c-section and was repeatedly reminded how dangerously high my blood pressure was due to preeclampsia. I already wasn’t starting this motherhood journey the way I’d hoped. So, I didn’t want to fuck this quiz up. She affirmed the correctness of my answers and gave me a warm smile and nod. I took that to mean that she agreed with me. I was going to be a great mom.

By the second week of my son’s life earthside, I had one nipple that was chaffed, sore, bleeding occasionally. Yes. I used the organic nipple balm. The other nipple was functioning but was unfortunately attached to the less milk abundant breast. My son began to fuss. Loudly. His entire body stiff, arms splayed open in frustration. Until this point, his latch had been great. Something changed, however. Now, he kicked aggressively and cried abundant tears when my nipple made contact with his mouth. He was not eating enough. I researched why this could be. I tried different holds, pumping even the sore nipple with tears of agony welling up in my eyes to try to produce more milk to freeze for future bottle feedings. I wanted to be prepared to give myself time to heal when/if this happened again. Pumping on a chaffed nipple was what I’d hoped was peak “this sucks,” for me. They tell you pumping more will help you produce more milk. I’ve heard many testimonials to this truth and a few to the contrary. For me, pumping only produced more tears. My nipple eventually healed after I began using a plastic nipple guard my friend, also a new mother, purchased for me. Feedings became easier. Finally, I felt like one of those moms I admired. Some I knew. Others I didn’t. Moms who look like they take time and energy to be patient loving attentive moms. My son enjoyed the nipple guard too.

One month after my baby’s birthday, I sat on the stoop of our brownstone Apartment cradling him prepared to finally breastfeed outside of my home or the pediatrician’s office/ ob/gyn clinic. It was a hot day. We didn't have air conditioning. I was proud to possibly perform what I considered an amazing phenomenon of the human body, in public. I wanted to look anyone in the eye who passed and glanced in my direction during this sacred, beautiful act. I was ready to make my activism seen...known. I wanted to challenge any glances contrary to approval. Proud. Stern. Stately. I am proudly a black woman. I was also proudly a breastfeeding woman -- just with a nipple guard. Eventually it was time to feed my baby. I realized I left the nipple guard upstairs, so I took out one of my breasts and attempted to put my bare nipple in my baby’s mouth. He hollered and protested. A foiled attempt however, not the final one.

Two weeks later the kicking and screaming started again, even with the nipple guard. I relied on the advice and support of my fellow new moms one of which paid for an in-home lactation consultant. This one was different than the hospital counselor. She was more thorough. She weighed my baby before and after feeding. She observed his latch and informed me that I probably didn’t need the nipple guard anymore. “He’s doing perfectly! Great latch!” I smiled in affirmation. But felt the sting of impending failure creep up from that nipple guard comment. I had been using it religiously for a little over a month. Maybe that was too much time. She watched me pump for 20 minutes. Observed that I was producing a “perfect” amount of milk and put me on a more strict pumping schedule so I could start to store milk. I hadn’t been able to store milk during the days leading up to her visit. His appetite had grown voracious. I was pumping and feeding around the clock. Days blurred together. I was so tired. I resented my husband for being able to leave the house to go to the laundromat or the corner deli. I cried more. My child’s appetite grew more insatiable.

I lamented a bit on instagram stories about my journey thus far. Many mothers expressed their similar journeys and frustrations with breastfeeding. They connected me to other moms and doulas. A few moms directed to lactation support groups. The thing was, I had anxiety about leaving the house. I was unsure that I would be able to perform the act of breastfeeding in front of other moms. I began to feel my goal of being a great mom slipping away. How was I only 1.5 months in and already fucking up?

A very good friend of mine, a mother of four young children, also a black woman, informed me that she too was unable to adequately breastfeed her first 3 children. She supplemented the little breast milk she was able to produce with formula and donor milk. She too pumped often, on the highest setting sometimes. Her first three children had been delivered via cesarean. All three had some amount of trauma attached the circumstances of their birth, from hospital staff to insurance, her first was the most traumatic of them all. Yet, all of her children are remarkable. My idea of a great mother was becoming more layered. As a result, I massaged the thought of formula feeding and tabled it.

I’ll never forget asking my husband, through tears, to run to the drug store to get formula one particularly rough night. I counted every ounce of formula I gave my baby. I tried to reserve his consumption of it for times when he wouldn’t latch at all, which became more and more frequent. Every time I prepared a bottle of formula for him I cried. I couldn’t watch my husband feed it to him. Each time he was fed from the bottle, his crying stopped. He was full, not of breast milk, but of a manufactured substance. He would burp and fall asleep just like he did when he was full of breast milk. He was full. He was at peace. Did he know the difference? Maybe I wasn’t a great mom at the moment, but I was starting to feel like a pretty ok one.

Feeding my baby formula two weeks into his third month still evoked intense sadness for me, but somehow it also allowed me to experience more freedom: longer naps, sporadic phone meetings for work, time out of the house with or without my baby. The sadness led me to once again seek out lactation support. A doula I met on Instagram told me how bad the formula advice was that my friend gave me. I disagreed but thought this doula’s perspective was worth exploring. Maybe my friend wasn’t as educated as this doula was on the subject. Maybe this doula wasn’t as educated about the validity of one’s inability to breastfeed.

I walked 2 miles (part of my personal recovery from my csection) to another lactation counselor’s office. I’d called the day before to make sure someone would be there. I showed up. She wasn’t there. My hopes of reclaiming my great mom title came crashing down. It didn’t help that I had also just had an argument with a close friend that morning. I was reeling with anger and frustration. “WHY HAS ALL OF THIS BEEN SO HARD?!” My pregnancy was mired in sickness. I developed a disease that came pretty close to taking me, my baby, or both of us out of here. And now breastfeeding wasn’t going well? I felt faint and dizzy from the thoughts of failure. I accepted defeat during the two mile walk back home and immediately made my son a bottle of formula.

I’m four months into being a mom and I’m learning more and more each day that I am not just an ok mom, I’m a good mom. I know this based on the fact that my child is happy and according to his pediatrician, quite healthy. He exudes joy. He is taken care of and loved with every fiber of his parents’ (and grandparents’) being. I’m still sad, however. When hashtags and my instagram algorithm remind me that other moms would look at what I feed my child in pure disgust, I get sad. When I see my friends effortlessly whip out a boob to soothe their fussy child forming an instant, animalistic, instinctual, necessary bond, I’m sad.

My mother breastfed me for two months before switching to formula. She had to go back to work. She tells me she couldn’t produce enough milk to store. I too had a voracious appetite, apparently. I didn’t know this until after I gave birth. Why would I? I didn’t fit the description of the “formula fed baby” I pieced together from the statistics freely tossed at me during breastfeeding class.

Simply put, my baby preferred the bottle over my breast. Ultimately, he decided for himself and left me in the grey of a seemingly black and white issue: breastfeeding is best, formula is worst. Pick a side. What of those of us whose children picked a side for them? Are we cast out of the club? Do we form our own club? As a black woman, I’m pretty exhausted with aspects of my existence being defined in reaction to othering. And now, it seems like there’s no way for me to cross the isle into Breastfeeding Mom Land. Even if breastfeeding women empathize with my situation, I will still envy their ability to breastfeed because I cannot. I will still, somehow be othered and quite frankly, as a result, judged.

Motherhood is not a monolith. Our experiences, while somewhat similar, are wholly our own. So are our children (archaic concepts of the ownership of people aside). The best lesson from motherhood so far is that my child is not a vessel for my insecurities or fears. He is not a projection of the aspirations I have for myself. He is his own person with his own karma, abilities, and abundant future (hopefully joyful) experiences.

The movement for public breastfeeding is in the lead for breastfeeding causes and this messaging exists in a variety of media. Black breastfeeding is a distant cousin. Still present. Not as amplified. Which is why I wholeheartedly support Black Breastfeeding Week and its mission. I want other black mothers to know of this movement. I want them to do their independent research on breastfeeding, take classes, form support networks early and often (or at least know where to go for breastfeeding support). Very few moms discuss how incredibly hard breastfeeding actually is. Even fewer discuss the inherent effects of racism on black mothers from the healthcare system to the availability of general education on the topic of breastfeeding. #Blackbreastfeedingweek will hopefully change that.

I am choosing to nurture my child holistically. I’m not sure whether this means stepping away from social media to eliminate the trigger of seeing a woman breastfeeding, especially since I’ve received so much helpful advice and support from complete strangers on social media. I am sure that it involves formula, albeit organic. I’m certainly not happy about my ejection from the breastfeeding club, especially when I tried so hard to get in. Expending more time and resources to be told what I’ve already tried, about which I’ve cried so so much about to this day, no longer interests me. I’m really only interested in being present for my baby’s beautiful growth which I’m overjoyed to witness, even behind occasional tears.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racism and Sustainability in Fashion

By Whitney McGuire, Esq.

Fashion Revolution Week, the fifth of its kind has come and gone. A lot of manifestos, pledges, and educational actions were made to give more truth to the power of the sustainable fashion movement (sustainability in every industry, really). But missing from virtually all of these declarations for change was the acknowledgement of race, specifically racism which is deeply entrenched in the issues calling forth the need for increased sustainability measures in the first place. Racism is the least sustainable system we have created and perpetuated as a human species and there is no way humanity will survive without shifting its practices towards sustainability. So why the blatant omission, in the age of empowered, glaring white supremacy?

Definitions, especially in the age of “isms,” hashtags, and blanket statements, are crucial. Let’s start by defining what sustainability is. In short, according to Google, sustainability is the avoidance of the depletion of natural resources in order to maintain an ecological balance, as in, "the pursuit of global environmental sustainability." A more comprehensive definition of sustainability provided by the Brundtland Commission in 1987 provides that sustainability means “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Essentially, sustainability is about being selfless, to a certain extent. Or at least it’s about being aware of how one’s self impacts one’s environment and whether one’s practices in the present create value to support future generations.

Next, let’s attempt to define racism. The elementary version (thanks, Google) is “prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one's own race is superior.” A deeper take is that racism includes the systemic perpetuation of exclusion and dehumanization of historically oppressed races. Racism looks like many things. It can look like a racial slur being hurled at a passerby, a joke about a historically oppressed culture, calling the cops on any black person who has without a doubt not committed a crime, erecting prisons for the sole purpose of reducing the population of black males, using state sanctioned violence as a way to terrorize entire historically oppressed communities, attempting to justify these acts in the name of egalitarianism/all lives mattering, or not correcting the behaviors of others perpetuating these acts, etc. Racism has plenty of sub categories, all of which blur together. It’s a spectrum. On one end there is white supremacy, the KKK, etc. on the other there are white liberal “activists,” many of which happen to be environmentalists as well. Regardless of where one falls on the spectrum, the truth is we all participate in the system of racism to some extent, either as the oppressed or as the oppressor (intended or not). Which is why it baffles me that this topic is usually omitted from sustainability agendas and conversations.

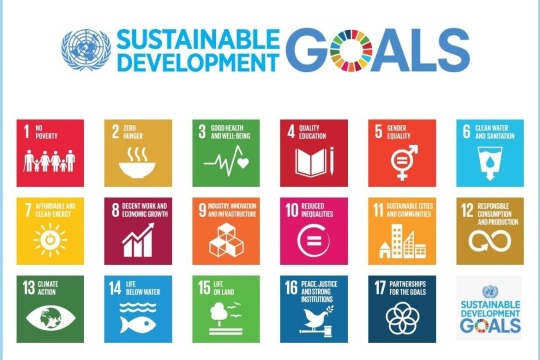

Below are the 2015 Global Sustainability Goals for businesses and organizations according to the United Nations.

It’s very clear that eliminating -- or at least reducing the effects of -- racism is not a global goal for sustainable development, yet almost every goal in this chart has a deep complicated relationship with racism which results in mostly black and brown people all over the world being adversely affected by the issues identified. For any sustainable agenda to be truly successful, we need to acknowledge and eliminate the elephant in this (global) room. If we fail to identify the malignancy, all restorative measures will be in vain and no real sustainable value will be created.

According to Russ Vernon-Jones, “[t]he underlying ideology of racism is that some groups of people can be defined as ‘other’ and labeled ‘inferior’ by a dominant group that sees itself as ‘superior.’” He further explains:

[a]s the age of colonization began in the 16th and 17th centuries, white Europeans developed the ideology of racism to justify the theft of resources, degradation of the land, the enslavement of people, and genocide directed at dark-skinned people and indigenous people all over the world. Greed was the primary driver of these practices. Disregard for the effects of these practices on the targeted populations was (and is) central to the operation of the system. Practices and enterprises today that contribute to the degradation of the environment and to climate change are rooted in the same features – greed, a feeling of being “superior” to those most affected, and prioritizing one’s own profits and comfort as completely legitimate, regardless of the effects on others or on the environment. Racism has long provided a justification for such perspectives, as enacted through colonization, genocide and slavery, extending into the present.

For instance, according to author D.N. Pellow:

Black Lives Matter challenges the scourge of state-sanctioned violence…with a primary emphasis on police brutality and mass incarceration…If we think of environmental racism as an extension of those state-sanctioned practices—in other words a form of authoritarian control over bodies, space, and knowledge systems— then we can more effectively theorize it as a form of state violence, a framework that is absent from most [environmental justice] scholarship”

Let’s start with food. One of the most clear examples of environmental racism is hunger or “food insecurity.” One in seven (1 in 7) Americans struggle with hunger. According to the University of New Hampshire Sustainability Institute, in 2014, 48.1 million Americans were classified as food insecure, translating to 14% of households in the U.S. One in four (1 in 4) African American households were classified as food insecure and more than one in five (> 1 in 5) Latino households were classified as food insecure, compared to one in ten (1 in 10) white households. Latino and African American households are twice as likely to suffer from hunger than their white counterparts. Additionally, landfills, water pollution, and other environmental violent acts are much more likely to occur in lower-income communities of color. We see similar effects in product manufacturing industries such as fashion and tech. Most people who manufacture goods and textiles globally are people of color. Yet the majority who profit off of these industries are not.

Enter the sustainable fashion revolution, a movement that is attempting to highlight the economic and social injustices experienced by those who make our clothes. This movement is perched upon the rhetoric that transparency is essential to eradicating the inhumane practices of an entire industry and is premised upon an egregious tragedy. In 2013, more than 1,000 garment workers lost their lives in Bangladesh due to a building collapse. This building housed a number of garment factories that manufactured apparel for brands including Benetton, the Children's Place, Joe Fresh, Mango, Primark, and Walmart. In other words, fast fashion companies. This is known amongst the sustainable fashion circles as the Rana Plaza incident.

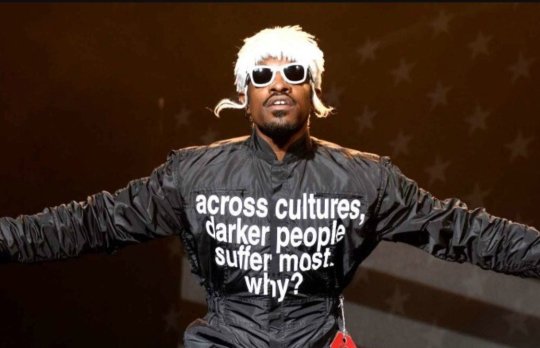

Rana Plaza is an example of capitalism’s role in environmental and racial inequality. In 1920, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that capitalism brought about “a chance for exploitation on an immense scale for inordinate profit, not simply to the very rich, but to the middle class and to the laborers. This chance lies in the exploitation of darker peoples.” Countries that consist of black or brown people have been referred to as the “Global South” -- less developed countries experiencing environmental and economic violence comparable to that which was perpetuated in the southern states of the U.S. during slavery, Jim Crow and, for many, present day. Historically, people of color in the Global South bear the most significant burdens of resource development, while receiving very little payoff. Capitalism has justified greed and Rana Plaza was a prime example of this truth.

A sustainable revolution in the fashion industry is therefore critical to the future of fashion, the preservation of natural resources and the empowerment of garment workers worldwide. However, I caution against any further omissions of the discussion of racism - the underlying reason this industry has been allowed to exploit people and resources.

Sustainability requires its participants to shift paradigms, see through barriers, and courageously and compassionately engage with people and systems that one might not otherwise consider in order to create a future we can all be proud of. Sustainability must be disruptive. Change is uncomfortable. But building a house, building an enterprise, building a mindset, new habits, a future, requires the destruction of fear, weakness, and comfort. This is the only way to drive innovation in our personal lives and in society. Sustainability is not ahistorical, and we must engage in reflexivity, that is, critically reflecting on how the past influences the present and the future. Moving forward requires addressing where we’ve come from and where we are going.

#sustainability#environmental sustainability#fashionsustainability#united nations#racism#bangladesh#whitneyrmcguire#fashionlaw

2 notes

·

View notes