Text

Monumental Migrations for World Fish Migration Day!

Celebrate and experience the joys of fish passage with the “living laboratory” that is the Elwha Watershed!

By: Dan Spencer, Information & Education Specialist, Puget Sound & Olympic Peninsula Complex (USFWS)

Photo: Tagged steelhead on the Elwha River, Credit: Olympic National Park

If you free it, they will come! This Saturday, October 24 is World Fish Migration Day! And what better way to celebrate than to follow some history making journeys? The Puget Sound/Olympic Peninsula Fisheries Complex (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service) is sharing a unique and engaging learning opportunity that features the world-famous Elwha River Restoration Project. Using real fish tracking data, participants plot and analyze the journeys of several fish throughout the watershed. Journeys that, until recently, had been blocked for close to 100 years.

Photo: A sample of the locations of steelhead and chinook salmon, Credit: FWS

The removal of Elwha and Glines Canyon dams on the mighty Elwha River of the Olympic Peninsula (WA) is the largest completed project of its kind. This historic achievement has also been the perfect opportunity to study the response of an ecosystem to dam removal. A large and diverse group of scientists from the Federal, State, and Tribal agencies as well as universities and conservation organizations have been studying many aspects of this living laboratory including: documenting the fish returns and movements; changes in the aquatic invertebrate communities; and changes in vegetation and animal populations on land.

Photo: Mobile tracking of lamprey on the Elwha River, Credit: Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

The stars of this activity are Chinook Salmon, Steelhead, Bull Trout, and Pacific Lamprey. These species are all born in fresh water and migrate to salt water for part of their lives before returning to fresh water to reproduce. Since the removal of the two dams, biologists have captured several fish from each of these species and fitted them with radio tags. Each tag is like a mini radio station, transmitting a signal in a unique frequency and limited broadcast range. Like switching between radio stations in a car, biologists switch between frequencies using their receiver to pick up these sub-surface fish-infused “stations.”

Photo: Tagged Chinook salmon, Credit: Olympic National Park

Sometimes biologists were indeed switching between frequencies while riding (as passengers) up Olympic Hot Springs Road, for example. Other times, fish were tracked while hiking, via airplane, or while rafting down river. Not a bad way to spend your day at the “office”, eh?! Radio frequencies (individual fish) detected were documented along with their approximate location. There were also several “fixed stations” throughout the watershed, where computers connected to the receiver recorded the dates, times, and frequencies of tagged fish within range. Over the course of several months, the story of each tagged fish took shape, allowing biologist to determine if restoration goals have been achieved.

Biologist from the Olympic National Park and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe have generously provided the fish tracking data for this learning activity. Participants get a taste of fisheries biology work as they enter locations on Google’s free “My Maps” program, compare migrations within and between species, and form conclusions. In addition to biology and science careers, participants will also inherently learn about technology, math, and geography in the process. But the sky is the limit when it comes to how integrated the learning experience can be. Participants are also encouraged to delve deeper into the story of the Elwha Watershed, covering geology, history, Native American Studies, civics, and government, for example.

This curriculum is very flexible in nature; applicable to a range of grade levels (7th-12th) and subject coverage, allowing teachers and parents to mold it to the educational needs of their students. Yet this educational opportunity it is not limited to this age range or even to students. We encourage all curious minds to learn about this historic project as they follow some epic fish migrations. Happy tracking!

Please click here to access and download the curriculum pdf file.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racing the Tide

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators tackle challenging nighttime project on Oregon Coast

The tide was slowly draining out of Nestucca Bay, and it was still hours before the sun would peek above the horizon. The only light was from headlights of the machinery that was already rumbling along in the cool night air, moving dirt at a furious pace.

A crew of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators were racing the tide.

The objective was to install a fish screen for a pump, and remove and replace tide gates that help manage water levels on the Upton Slough section of Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge on the Oregon Coast.

The entire project took weeks, but this critical element had to be done in a narrow window of time at the lowest tides last fall.

This work on soft ground on the bank of the Little Nestucca River was left to a crew of five heavy machinery operators from National Wildlife Refuges across the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Story Map with videos and audio clips available at

https://fws.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=64cdfe78fe87436881551befde79b8e7

In bureaucratic terms, the heavy equipment operators are known as wage-grade professionals. That’s the official term.

But to project leaders, facility managers and biologists --- they simply call them the backbone of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They're the people who turn habitat conservation dreams into reality.

They're creators of conservation.

“They are so important to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's mission. Without our wage-grade professionals, we couldn't accomplish the important habitat and conservation work we do on refuges. They're unsung heroes of conservation,” said Kevin Foerster, Refuge Chief for the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Due to the location and environmental factors for the Upton Slough work, this project had a variety of technical challenges including daily tidal changes, a variety of infrastructure upgrades/installations, ever-changing weather conditions, and the need for specialty heavy equipment to implement the habitat restoration.

“This was a technically challenging project and all the construction work was completed by our heavy equipment professionals. What really floored me was the morning of the first tide-gate replacement,” Oregon Coast NWR Complex project leader Kelly Moroney. "We were following the tidal cycles, which required operations to begin a 3 a.m. I have been involved in many projects over my 25-year career, but nothing came close to what I saw when I pulled up to that morning. It almost looked choreographed. I was impressed. They are true professionals.”

Gary Rodriguez, a 32-year Service employee and now-retired Facilities Operations Specialist/ Engineering Equipment Operator at Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, served as lead for the project.

“Our job was to execute the project. We had plans, elevations and equipment, and then it was up to us to be able to put that all together. Some folks were skeptical if we could do it. From our standpoint, it was not a problem. It was going to happen, and that’s what we did,” Rodriquez said.

The crew during the nighttime installation was (from left) Kenny Berry from Malheur NWR; Shaun Matthews from Willapa NWR; Gary Rodriguez from Oregon Coast NWR Complex; Kelly Connall from Little Pend Oreille NWR; and Tyrone Asencio from Willamette Valley NWR Complex. Dave Harlow from Willamette Valley NWR Complex primarily worked on the channel restoration at Upton Slough.

Spencer Berg, heavy equipment manager for the Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region, also worked heavy equipment on the project. He says that wage-grade staff play an essential role in conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I consider our wage-grade staff the backbone of the refuge system,” Berg said. “They’re doing the work on the ground, mowing the habitat, maintaining the boiler systems and parking lots, and creating wetland habitat. They are doing phenomenal things. On the Upton Slough project, a project like that takes a lot of planning and work to get going. You have to order the culverts and supplies, you have to get the permits, and watch the tide charts and weather. Getting all those factors lined up is a huge lift.”

All the construction work on the Upton Slough project was handled by the Service’s heavy equipment professionals, saving taxpayers close to $200,000 for the project.

Internally, multiple Service programs and departments helped with the development and execution of the program. Those programs include the Service's Water Resources Division, Inventory & Monitoring's Biological program, Ecological Services' Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office, Fisheries and Aquatic Conservation's Vancouver Office, and Connor Shea from the Partners for Fish and Wildlife in California.

External partners on the project included the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Nestucca, Neskowin & Sand Lake Watersheds Council and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

“Like most projects these days, partnerships were huge,” Moroney said. “We could not have accomplished this project without help from internal and external partners.”

The Service also reconstructed the historic slough channel as a part of the project. It was returned to its original path, winding across the lowlands. This will reduce flooding, which will benefit landowners in the Upton Slough watershed basin and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

It will also improve habitat for fish and wildlife. Dusky and Semidi Island Aleutian Canada geese, which are both identified as species of concern in the Pacific Flyway Council Management Plans, and other migratory waterbirds will benefit from the lowland pasture improvements. It’ll also improve fish passage and fish habitat requirements for federal- and state-listed Oregon coastal coho salmon.

“The bottom line is that the operators left their homes for two weeks, worked long hours as a team to deliver on a common goal,” Moroney said. “Their work and accomplishments on the Upton Slough project should be a model for refuges doing business. These professionals care about the resource, care about refuges, and take a lot of pride in their work – and it shows.”

Our wage-grade professionals -- the people who turn conservation ideas into conservation successes.

Story by Brent Lawrence / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

youtube

youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rufous Hummingbird: Glowing, Tiny Toughnecks

By Sarah Levy, External Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Rufous hummingbird. Photo credit: Creative Commons

Have you ever heard of an aggressive hummingbird? Meet the rufous hummingbird, a tiny roughneck that aggressively defends and chases other hummingbirds away from its preferred food source, even during migration. These little guys are bright, even glowing in the right light. They are “rufous” colored, meaning they typically have reddish-brown feathers. Males are almost entirely rufous with a vivid patch of iridescent rusty-red feathers on their throat, known as a gorget. Much like other hummingbirds, they feast on nectar and insects, sometime even swiping their prey from spider webs.

The hummingbird (chupaflor or chuparosa) played an important role in Aztec culture. These captivating birds represents the sun god Huitzilopotchli, a powerful warrior who guided the Aztecs’ journey to the Valley of Mexico. The story goes that he was born when her mother held a ball of hummingbird feathers to her breast. Hummingbirds, and particularly the feathers, continue to play an important role in Latin American heritage and customs.

Huitzilopochtli. Photo credit: Creative Commons

Rufous hummingbirds fly nearly 4,000 miles on their migratory routes, traveling from wintering areas in Mexico as far north as Alaska. Rufous hummingbirds breed in the Pacific Northwest and migrate north along the Pacific Coast in the spring, and return south through the Cascades and Rocky Mountains in summer following the later blooming wildflowers at higher elevations.

Rufous and other hummingbirds are threatened by many things including black market trading of their bodies and feathers. Some people believe that hummingbirds have supernatural powers, or can make the owner lucky in love. Fish and Wildlife and other law enforcement are actively cracking down on the international market for dead hummingbirds. You can help us conserve these amazing little birds by admiring them from afar—and letting these tough guys continue on their migratory journeys.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oregon and Washington’s Sweet Little Beach Bums

By Sarah Levy, External Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Baby snowy plovers with tags. Photo credit: K. Castelein/USFWS

Snowy plovers are sweet little beach bums. These white and tan small birds enjoy nesting on white sand beaches, often blending in with their surroundings. Although some snowy plovers stay on the same beaches year after year, other plovers enjoy short hops inland or down the coast, living anywhere between southern Washington and Latin America. They dine on crustaceans, mollusks, and insects.

Unfortunately, sharing beaches with humans has jeopardized the habitat and population of these birds. Off-road vehicles, building construction, recreational use, and even dogs have disrupted the nesting and breeding grounds of the snowy plover. Nonetheless, due to successful partnerships and the diligence of the public in respecting beach restrictions during the nesting season, western snowy plover numbers are higher than they have been along the Oregon and Washington coast in decades.

Agencies and organizations in the United States and Mexico have been collaborating to protect and restore the snowy plover’s habitat. Work between the Sonoran Joint Venture (a collaboration between the Fish and Wildlife Service and other cross-border organizations and agencies), and Mexican non-profits like Terra Peninsular and Pro Esteros have made dramatic improvements in protecting snowy plover habitat. Fencing, signage, and outreach continue to make progress in conserving these species.

Adult snowy plover feeding. Photo credit: D. Pitkin/USFWS

Help us make a difference by respecting conservation areas on beaches. Check out the video below about good doggy etiquette. Most of all, let’s work together to protect the snowy plover’s oceanfront property. Just like us, they enjoy a good day at the beach.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rare Bird Takes Flight this Fall

By Dana Bivens - Public Affairs Officer for the US Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo by Aaron Hamilton/USFWS

Have you ever seen a western yellow-billed cuckoo? Standing about twelve inches tall with a distinctive black and white patterned tail, yellow-billed cuckoos are now a rare sight in the western United States. Once a frequent resident in riparian forests along rivers, yellow-billed cuckoos have experienced population declines during the twentieth century. The US Fish and Wildlife Service listed these migratory birds as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2014.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, the yellow-billed cuckoo has become rare due to loss of habitat. Cuckoos love to forage for larger insects such as cicadas, katydids, grasshoppers and caterpillars along rivers and in flood plains. In recent decades, their foraging and breeding grounds have been lost to development, agriculture, and changes to river flows. We do still have larger stands of riparian forest in the PNW so if you listen attentively from late May through August, you may be one of the lucky few to hear and catch a glimpse of an elusive western yellow-billed cuckoo.

Photo By Steve Shunk/USFWS

When the sunny days of the Pacific Northwest summer begin to give way to fall, yellow-billed cuckoos head south to spend the winter in Columbia, Brazil, and Venezuela. Some even head as far south as northern Argentina where they remain until spring migration begins. During the winter months, cuckoos dedicate themselves to feeding and storing up the needed energy to make their long trip north to breed and raise their young.

Migratory birds are an important part of our Pacific Northwest Ecosystem, and we can all help to improve their habitat and make it safer. Small things like turning lights off during spring and fall migration and keeping cats indoors can help protect all migratory birds, including the yellow-billed cuckoo. For more tips on how you can help make your home a home for wildlife, please visit https://www.fws.gov/Oregonfwo/promo.cfm?id=177175843

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small but mighty! Goldfinches travel to the tropics and back

By: Dana Bivens - Dana is a PAO at the USFWS Portland Regional Office

Photo By Peter Pearsall, USFWS

Did you know, many of the birds we see in the Pacific Northwest in the summer spend their winters in the tropics? The goldfinch is no exception! You may have seen this charming bird in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington in the spring and summer months. Goldfinches are a common sight across the continental US and southern Canada. They are frequent residents at backyard bird feeders, and love to mill about in bushes, fields, and floodplains foraging for seeds.

The bright yellow color and aerial acrobatics of these social birds is a delightful sight to see. In the winter months, some of these tiny travelers migrate south as far as Mexico. Weighing in at only 0.7 oz, migrating goldfinches will take up their winter residences in the southern United States, and in northern Mexican states including Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, and along the Gulf of Mexico. In mild winters they may also be seen much further north.

While many birds make the trip south, some take up year-round residence in the continental United States, and are a common sight around birdfeeders in the winter when food is scarce. Always pleasant to see on a cold winter day, goldfinches are favorites for wildlife enthusiasts and birdwatchers alike.

Migratory birds are an important part to the Pacific Northwest Ecosystem, and we can all help to improve their habitat and make it safer. Small things like placing bird decals on window glass or keeping cats indoors can help protect all migratory birds, including goldfinches. If you want to make your backyard or garden a gathering spot for goldfinches, check out this information on making your home a home for wildlife: https://www.fws.gov/oregonfwo/documents/Education/USFWSBackyardBirds.pdf

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small Game Hunters: Catching Butterflies in the Pacific Northwest

By: Zach Radmer, USFWS Fish and Wildlife Biologist, Washington Fish and Wildlife Office

Photo: West Coast lady butterfly (Vanessa annabella) at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon; Photo credit: Zach Radmer

“Swoosh!” My net lay still, a colorful quarry perhaps captured after a brief sprint along the trail. Admittedly I’m more excited than you would think. It’s not every day that you catch something new. I don’t think people know that most butterflies get away. The large and sun-warmed individuals are highly motivated and will easily outpace you even into a headwind. I have carried a net for miles and caught nothing but mosquitos. But this time it’s a lustrous copper (Lycaena cupreus) that sports bright orange wings covered in dark black spots. Best of all, I have never caught one before.

Photo: Zach Radmer, biologist and butterfly enthusiast. Photo credit: Jerrmaine Treadwell

This is the part of the story where you think I would wax poetic about chasing butterflies as a kid, but the truth is my professional and personal interest in butterflies didn’t start until my colleagues at the Washington Fish and Wildlife Office introduced me. Butterfly catching is for everyone. Butterfly catching turns every hike or picnic into a scavenger hunt. In an alpine meadow or even a brushy field on the eastern slope of the Cascades you never know what you might find. Visit the same place four months later and you might find an entirely different crew of butterflies. Some fly in spring and some fly in late summer. Some could be ‘on the wing’ all year round because they spend the winter as adults resting in the crevices of trees and houses! Wherever you decide to go looking, bring a lunch. Butterflies are small game and decidedly not delicious.

Photo: Common wood-nymph (Cercyonis pegala) butterfly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS.

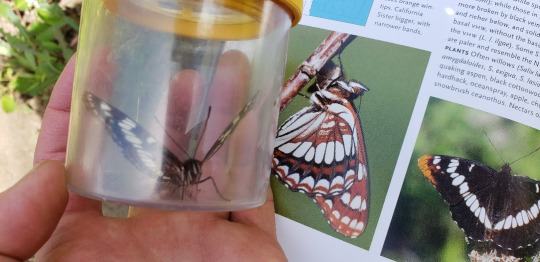

Butterfly catching is a cheap sport, and you can take it as seriously as you want (or not). A net and a field guide can be purchased for less than 50 bucks. I prefer Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest by Robert Michael Pyle and Caitlin LaBar. Butterfly nets come in different shapes and sizes and none cost a pretty penny. I use a collapsible net that is easier to backpack with. Unless you have the reflexes of Jackie Chan, a long handle is a good idea too.

There are two endangered butterflies in Washington State, and we like to talk about them a lot (See our web pages on Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly and island marble butterfly).

Photo: Zach in action. Photo credit: Jerrmaine Treadwell

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Washington Fish and Wildlife Office has been involved in butterfly conservation for a few decades. But most people don’t know that 202 butterfly species can be found in Washington and Oregon. Little ones, big ones, spanning just about every color you can think of. Butterflies in Washington and Oregon are sorted in six families, and many of them don’t take any special skills to identify. For example, this is a ‘mud puddle club’ of pale tiger swallowtails and western tiger swallowtails:

The pale wings, large size, and striped wings are unmistakable for anything else. You don’t even have to chase it with net! The western tiger swallowtail (the yellow butterflies in the picture) has a few look-alikes, but only in some portions of the range. If you are butterfly catching in Olympia when you see this one, you know it is very unlikely to be a two-tailed tiger swallowtail or an Oregon swallowtail. Trust me, this isn’t as hard as you think. The Lorquin’s Admiral is another great example of an easy-to-identify butterfly.

Photo: A mud puddle club of swallowtails (both pale and Western). Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

Wherever you’re going, make sure you know which butterflies you should probably let be. A good guidebook will let you know what’s rare and what’s common. This mug shot might look like the federally endangered Taylor’s checkerspot, but it is actually a closely related subspecies (E. e. colonia) that is common in the Cascades:

Butterfly photography is great but some people want to take their small game home. Personally, I don’t collect the butterflies I catch. Butterfly collecting can contribute greatly to our understanding of these species, and collectors have no chance of impacting the abundance of common species. Collecting, pinning, and preserving butterflies is its own set of skills that I won’t address here. Figuring that out will give you something to do when the weather is poor for butterfly chasing.If you are nervous to get started on your own, I personally recommend you check out the Washington Butterfly Association that leads occasional field trips. Experts can help you discover where to look and tricks for telling some groups of butterflies apart. This wild-looking pink-edged sulphur you might assume is unique, but in reality is difficult to pick out of a lineup of other sulphurs.

Lorquin’s Admiral (Limenitis lorquini) buttefly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

There are only a few more things to know before you start. First, catching butterflies is not allowed in National Parks. Not even catch and release. If you must, sign up for the National Park Service’s Cascade Butterfly Project citizen science program to monitor butterflies in the Parks. Second, butterflies should not be moved from where you caught them, and definitely not released outside of their natural range. Butterflies carry diseases and may inappropriately hybridize or compete with closely related species.

Photo: Edith's checkerspot butterfly ( Euphydryas editha colonia), not to be confused for the endangered Taylor's checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori). Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

I will join many other writers on this topic before by saying that the first step in conserving butterflies is to notice them. Where they are, where they aren’t, and what they’re doing. Scientists and enthusiasts can contribute to butterfly conservation by recording what they see and pointing it out to those around them. So grab a net and notebook, and happy hunting.

Pink edged sulphur (Colias interior) butterfly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Boon(e) for Stewardship: What America’s Oldest Conservation Club Taught Me About Caring for Nature

By: Molly Good, USFWS biologist

Photo: Theodore Roosevelt, founder of the Boone and Crockett Club

Working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), I have long held deep admiration of and appreciation for America’s conservation heroes, including John Muir, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell, Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, and Rachel Carson, to name a few. Their lasting contributions continue to enhance our nation’s scientific understanding of ecosystems and natural processes, management and preservation of land and natural resources for future use, and recreational opportunities. These founding conservationists and their legacies have also motivated me to find ways to leave my own mark on the natural world. Over time, I have found that modern-day conservation heroes exist too, and that, depending on their values and goals, they can be powerful partners with our agency in affecting positive change for our nation’s wildlife and people. For me, The Boone and Crockett Club – the oldest conservation organization in America – exemplifies the power of positive change through its diverse and inspirational network of natural resource stewards.

Photo: Waterfowl hunting at Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge in Ridgefield, Washington; Photo credit: USFWS

I was a bright-eyed, twenty-four year-old graduate student when my advisor introduced me, through his involvement, to the Boone and Crockett Club. I am ashamed to admit I knew nothing about the Club at the time, yet I couldn’t kick the theme song from Disney’s 1955 movie, “Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier!” from my head! I was impressed to learn that Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell founded the Boone and Crockett Club in 1887 in response to declines in wildlife populations, especially in large animals or big game. At the time, founding Club members were particularly motivated to think creatively about how to balance human and wildlife needs while maintaining traditions and a fair chase ethic around resource consumption, especially as a wildlife management tool. Since the late 1880s, the Club and its membership—which has included military and political leaders, business leaders, outdoors sports enthusiasts, scientists, writers, and industrialists—have coordinated regularly, campaigned and raised money, pioneered policy initiatives, and initiated legislation to advance the following mission:

“…to promote the conservation and management of wildlife, especially big game, and its habitat, to preserve and encourage hunting and to maintain the highest ethical standards of fair chase and sportsmanship in North America.”

The USFWS and Boone and Crockett Club align in their dedication to increasing access to public lands and their recognition of hunting and fishing as a cornerstone of our American heritage. In the last year, the U.S. Department of Interior has taken significant action to expand public access to public lands and waters by creating new hunting and fishing opportunities at National Wildlife Refuges and National Fish Hatcheries, which are managed by the USFWS. The expansion spans 4 million acres nationwide across the refuge system and, of the total 567 National Wildlife Refuges, the public may now hunt at 399, and fish at 331, of them. This expansion, coupled with other monumental legislative achievements such as the recent passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, have been successful, in part, as a result of a shared vision among federal agencies, the Club, and other organizations and their commitment to preserving important natural areas for our use and enjoyment.

Photo: The Boone and Crockett Club’s Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Ranch in Missoula, Montana

The USFWS and Boone and Crockett Club also align in their goal to increase access to hunting and angling opportunities for underrepresented groups and educate the public, especially youth, to promote shared use of natural resources and build stewardship of maintaining healthy ecosystems. In addition to supporting a Conservation Education Committee that meets regularly, the Boone and Crockett Club manages the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Ranch, a working cattle ranch on the East Front of the Montana Rockies in Missoula, Montana. Approximately 2,500 students and educators participate in the Club’s Conservation Education Program, which includes classes, programs, and trainings hosted at the Ranch, each year.

Photo: Students glassing terrain at the Ranch

Boone and Crockett Club President, Tim Brady, reflects upon the importance of the Club’s Professional membership in supporting these conservation policy and educational initiatives, stating that “these accomplishments would not be possible were it not for the hard work and dedication of our Professional Members, most of whom are hunters themselves and either work in wildlife and habitat management for federal and state agencies, partner with the Club’s University Programs, or are affiliated with like-minded conservation organizations.” In my own life, I feel privileged to have had the experience tracking deer in the snow, watching a bird dog flush pheasants out of a field, and land a steelhead on an 8 wt fly rod from the river. The relationships I have built within the Club, however, have shaped my values about hunting and fishing, fair chase ethics, wildlife management, and conservation the most. My eager interest in supporting the Club’s activities, and my participation in the Club’s various committees and annual meetings, helped m secure a Professional Membership with the Club in 2019. I am honored to be part of this membership, which includes 172 wildlife professionals and enthusiasts from across the nation, and I feel more knowledgeable in my role as a biologist with the USFWS, and more capable of understanding the values held by the diverse human natural resource users we serve.

Photo: Hunting at the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation in Dundee, Illinois; Photo credit: Molly J. Good

While recognizing that all of us use and appreciate the natural world in different ways, and that we all have our personal conservation heroes, I hope this story also inspires you to leave your own mark and enhance your own conservation stewardship—the sustainability of our natural resources and future of our recreational privileges depends on it!

For more information about the Boone and Crockett Club, please contact me ([email protected]) or visit: https://www.boone-crockett.org/. All photos are courtesy of the Club unless otherwise noted.

Photo: Roosevelt Elk at William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge in the Willamette Valley, Oregon; Photo Credit: USFWS

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Birds and the Bees...and the Fish! Salmon Safe Gardening

By Julia Pinnix, Visitor Services Manager, Leavenworth National Fisheries Complex

Photo: A native bumblebee on non-native flowers. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

The first adult spring Chinook salmon arrived at Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery in mid-May this year. In my high-elevation home garden, daffodils were fading and spinach was two inches high. Gardens and salmon are more tightly linked than many people realize. Consider that whether you live three feet from a salmon stream, or three miles away, whatever goes into your garden finds its way via water into a salmon stream.

I’m a big fan of manure when it comes to fertilizing my garden. This is often a better choice than concentrated fertilizers. Manure offers a healthy dose of nutrients to plants, without overdoing it. But too much of a good thing is still too much: it’s the concentration that counts. That goes for manure as well as for chemicals. Excess nutrients wind up contaminating rivers and streams, promoting unwanted plant and algae growth. Too much nitrogen can even change the pH of rivers, making them more acidic. Acidic water kills salmon eggs and interferes with fish growth.

Photo: The Leavenworth NFH pollinator garden. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

I avoid using herbicides in my garden or yard. To keep weeds down in the gravel of my driveway, I spray concentrated vinegar on a sunny day. It works well and doesn’t leave behind harmful chemical residue.

I especially avoid pesticides. These can have widespread effects that we are only beginning to understand. Insect populations in many places all over the world are down by as much as 30-70 percent, a startling change with broad consequences. This change may be partly caused by the use of neonicotinoids. Neonicotinoids are chemical insecticides in use since the 1990s. Not only have these compounds proved lethal to bees, they harm salmon by killing the aquatic insects that are food for young fish.

Photo: Palmer's penstemon blooming in the LNFH pollinator garden. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

It’s not just gardens that pose risks to salmon. Leaching chemicals and fertilizers can come from lawns, too. Lawns can serve as filters if not overloaded with chemicals. Washing your car on the grass, for instance, traps detergent, mud, and grease and keeps it out of the streams—and waters the lawn, too.

Reducing lawn size and planting native species is even better—native plants need less watering, and provide habitat to local birds, insects, and other animals. Especially here on the eastern side of Washington State, using less water in your lawn and garden means more water stays in the rivers to benefit salmon.

Photo: A view upstream on Icicle Creek toward the peaks of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

Gardens don’t have to be just vegetables or flowers. Planting shrubs and trees counts, too. Bob Stroup, a retired high school teacher and member of Trout Unlimited in Leavenworth, has planted hundreds of trees and bushes at his property along Icicle Creek. People like Bob who are lucky enough to have waterfront land also know the consequences of living close to a river: floods. His home is better protected because of his plants, which divert flood water and stabilize the bank.

At the hatchery, we support insects with a pollinator garden. The Chelan-Douglas Master Gardener program helps maintain the garden and educate visitors and students about the value of insects and native plants.

I love gardening. I also love bees, birds, and salmon. I try to include them in my gardening choices. What we do at home can impact our rivers and wildlife. It’s something to keep in mind.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How are fish scales like rings on a tree? Look closely...

By Julia Pinnix, Visitor Services Manager, Leavenworth Fisheries Complex

Photo: Biologist Katy Pfannenstein holds up a scale from a spring Chinook. Credit: Julia Pinnix, USFWS

The thrill of hooking into a fighting fish never gets old. Success in bringing it to the bank or boat comes with a choice: will this fish be dinner, or will I slip the hook and let it go? If you choose to keep it, likely you have dinner on your mind. I favor dinner—but I also plan to read the story of the fish in its anatomy.

Reading that story starts from the outside, with a look at fins. Does it have an adipose fin—the little one between the tail and the big fin on its back? If it does, that salmon can’t be dinner! It’s wild and must be released. Hatchery salmon have their adipose fins clipped off, precisely so anglers can tell which ones are keepers.

Photo: Otoliths (ear bones) collected from king salmon in southwestern Alaska. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

I scan the fish’s sleek and slimy body. Does it carry bite marks left by seals? Was it punctured by an osprey’s claws? I’m not the only one thinking of dinner… Are there sea lice still clinging to its skin? Sea “lice” are copepods that attach to salmon in the ocean. They will soon die in fresh water, so their presence tells anglers the salmon has not been out of the ocean for long.

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve had a microscope at home. My first look into the magnified world captured me. There are two parts of a salmon that are particularly fascinating under magnification: scales, and earbones (otoliths). Biologist Katy Pfannenstein at the Mid-Columbia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office finds scales exciting. While we were helping at a spawning event last year, she thrust a scale clamped in tweezers toward my camera, saying, “Take a photo of this!” After I got the picture, she carefully laid the scale on a card, along with a collection of scales from every salmon spawned.

Photo: A model of spring Chinook in the Leavenworth NFH visitor center demonstrates the presence of an adipose fin on a wild fish. Credit: Julia Pinnix/USFWS

Under high enough magnification, scales reveal lines like the rings in trees. Like wood, scales store information about growth conditions. An experienced biologist can read scales to find out whether the fish was raised in a hatchery, and how old it is. This information is collected and included in annual reports for our hatcheries.

Otoliths (earbones) also have ring-like layers, but they usually take a lot more preparation to read. They’re also hard to find! A Chinook salmon is a large fish, but its earbones are less than half the size of a dime. They resemble tiny bone leaves. To locate them takes a rugged knife, some knowledge of anatomy, and patience.

Photo: Some fish reveal encounters with predators. Credit: Betsy Bamberger/Douglas County PUD

Otoliths, like all bones, preserve isotopes like strontium as they form. This, in essence, also preserves a map of where the fish spent its time. Research proved individual hatcheries can be identified by their isotopic signature in otoliths. The ear bone alone can reveal where salmon are from and where they’ve been, as well as their age.

I always take a look at the internal organs when I am cleaning fish. Cutting open the stomachs of trout is a great way to see what they’ve been eating, which gives anglers clues about what to use for bait or flies. Odd lumps and bumps on other organs can indicate diseases or parasites. One winter in Alaska, I tracked the growth of parasites feeding on the livers of rainbow smelt I caught throughout the season. It didn’t stop me from eating them, but it did prompt me to cook my fish thoroughly!

Salmon are a great choice for eating. Their lifespan is short, almost never more than six years, which means heavy metals like mercury don’t have time to build to dangerous levels in their bodies. Their time in the ocean packs their tissues with healthy fatty acids. Although numbers of returning salmon have been very low over the last three years, spring and summer Chinook from our hatcheries have allowed anglers opportunities to fish in our area when other fisheries are shut down. That’s something we celebrate, in part by joining other anglers on the river when we can, casting our lines in hopes of fish.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Heat Blob: Disrupting Ocean Food Chains

By Sarah Levy, a Fish and Wildlife Service public affairs officer in Portland, OR.

The heat blob. It brings to mind the horror movie, “The Blob,” or a large wildfire seen from space. The heat blob evokes an image of a hot, angry, foaming bubble that slowly and methodically wrecks everything in its path.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what it is.

The heat blob, or simply, “the blob” as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) calls it, is a relatively new oceanic heat wave taking over the continental shelves around the North American and Asian continents. Scientists first observed a heat blob in 2014, when it disrupted marine ecosystems off of the West Coast of the United States, and depressed salmon returns. In 2019, the blob returned.

“There are serious disruptions to the food chain going on right now due to ocean warming and other changes,” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service seabird coordinator Roberta Swift said. “These Pacific-wide changes affect seabirds throughout their entire Pacific Range. This could affect the quantity or quality food available for seabirds in the Pacific, meaning seabirds might skip breeding, abandon their nests, or die of starvation.”

The changes start at the bottom of the food chain, and disrupt predator-prey relationships all the way to the top. Here’s one example: Warmer water conditions encourage warm water zooplankton to proliferate in areas formerly dominated by cold-water species. Warm water zooplankton have a lower lipid (fat) content than cold-water plankton. For the fish that rely on the cold-water plankton, the warm water zooplankton simply are not as nutritious. The forage fish that eat the warm water zooplankton do not grow as big, which then results in fewer calories and less energy for their predators, including seabirds. That, in turn, can result in starvation and death.

In 2019, thousands of migratory short-tailed shearwaters died off the coast of Alaska. Shearwaters spend their summers (our winter) and breed in South America, and then fly up the coast during their winter (our summer). Because of their high metabolic rate, they rely on huge numbers of krill, small fish, or squid. If there are fewer numbers of these krill or fish, or they have a lower value nutritional content, it could lead to a significant die-off. In previous years, die-offs affected common murres, tufted puffins, and Cassin’s auklets, each in turn.

Picture courtesy of NOAA

“Ocean warming events most affect colder oceans in this way,” Swift said. “Warming events can alter ocean circulation patterns and affect forage fish distributions which may require seabirds to fly farther for their meals, making feeding themselves and their young much more difficult and energy expensive.”

Another way that that human activities affect the marine food change is through input of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Excess carbon dioxide causes ocean acidification, which is the absorption of carbon dioxide into seawater. According to NOAA, a series of chemical reactions result in an increased concentration of hydrogen ions and a decrease in carbonate ions.

Carbonate ions are essential building blocks of calcium carbonate. Calcium carbonate is critical in the formation of the exoskeletons of crustaceans that make up the zooplankton, fundamental components of the oceanic food chain. Many seabirds eat the larval stages of fish and invertebrates, but shells and exoskeletons cannot develop normally in an acidified ocean with increasingly acidic conditions. We will all have less seafood to eat if larval crustaceans can’t develop into adults.

According to NOAA, shifts in the marine food web during the evolution of the 2014-2015 marine heatwave called, "the Blob," forced sea lion mothers to forage further from their rookeries in the Channel Islands off Southern California. Hungry pups set out on their own, but many became stranded on area beaches. Picture courtesy of NOAA

Many communities around the world are dependent on shellfish and fish higher up the food chain for food and exports. These days, shellfish farmers must pay special attention to the acidity of the water that bathes larval oysters in order to ensure their development into the adult oysters we eat. The changes affecting tiny organisms in our oceans right now are leading to big changes for fish, birds, and people.

Although getting rid of heat blobs and ocean acidification might seem daunting, some of the little things you can do can help. Reduce your energy footprint. Recycle your waste. Try to be mindful of your consumption. Most of all, treat your oceans and your planet with respect. All the little things (and big things!) count.

Below are some more resources to learn about the blob and ocean warming.

https://www.eopugetsound.org/magazine/IS/marine-heat-wave

https://www.eopugetsound.org/articles/warm-water-%E2%80%98blobs%E2%80%99-significantly-diminish-salmon-other-fish-populations-study-says

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racing the Tide

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators tackle challenging nighttime project on Oregon Coast

Story by Brent Lawrence, public affairs officer in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Regional Office.

The tide was slowly draining out of Nestucca Bay, and it was still hours before the sun would peek above the horizon. The only light was from headlights of the machinery that was already rumbling along in the cool night air, moving dirt at a furious pace.

A crew of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service heavy equipment operators were racing the tide.

The objective was to install a fish screen for a pump, and remove and replace tide gates that help manage water levels on the Upton Slough section of Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge on the Oregon Coast.

The entire project took weeks, but this critical element had to be done in a narrow window of time at the lowest tides last fall.

This work on soft ground on the bank of the Little Nestucca River was left to a crew of five heavy machinery operators from National Wildlife Refuges across the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

In bureaucratic terms, the heavy equipment operators are known as wage-grade professionals. That’s the official term.

But to project leaders, facility managers and biologists --- they simply call them the backbone of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They're the people who turn habitat conservation dreams into reality.

They're creators of conservation.

“They are so important to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's mission. Without our wage-grade professionals, we couldn't accomplish the important habitat and conservation work we do on refuges. They're unsung heroes of conservation,” said Kevin Foerster, Refuge Chief for the Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region.

Due to the location and environmental factors for the Upton Slough work, this project had a variety of technical challenges including daily tidal changes, a variety of infrastructure upgrades/installations, ever-changing weather conditions, and the need for specialty heavy equipment to implement the habitat restoration.

Watch the full Story Map with videos and interviews at https://fws.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=64cdfe78fe87436881551befde79b8e7

“This was a technically challenging project and all the construction work was completed by our heavy equipment professionals. What really floored me was the morning of the first tide-gate replacement,” Oregon Coast NWR Complex project leader Kelly Moroney. "We were following the tidal cycles, which required operations to begin a 3 a.m. I have been involved in many projects over my 25-year career, but nothing came close to what I saw when I pulled up to that morning. It almost looked choreographed. I was impressed. They are true professionals.”

(Facilities operations specialist Gary Rodriguez, left, and Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex project leader Kelly Moroney.)

Gary Rodriguez, a 32-year Service employee and now-retired Facilities Operations Specialist/ Engineering Equipment Operator at Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, served as lead for the project.

“Our job was to execute the project. We had plans, elevations and equipment, and then it was up to us to be able to put that all together. Some folks were skeptical if we could do it. From our standpoint, it was not a problem. It was going to happen, and that’s what we did,” Rodriquez said.

The crew during the nighttime installation was (from left) Kenny Berry from Malheur NWR; Shaun Matthews from Willapa NWR; Gary Rodriguez from Oregon Coast NWR Complex; Kelly Connall from Little Pend Oreille NWR; and Tyrone Asencio from Willamette Valley NWR Complex. Dave Harlow from Willamette Valley NWR Complex primarily worked on the channel restoration at Upton Slough.

Spencer Berg, heavy equipment manager for the Service’s Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region, also worked heavy equipment on the project. He says that wage-grade staff play an essential role in conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“I consider our wage-grade staff the backbone of the refuge system,” Berg said. “They’re doing the work on the ground, mowing the habitat, maintaining the boiler systems and parking lots, and creating wetland habitat. They are doing phenomenal things. On the Upton Slough project, a project like that takes a lot of planning and work to get going. You have to order the culverts and supplies, you have to get the permits, and watch the tide charts and weather. Getting all those factors lined up is a huge lift.”

All the construction work on the Upton Slough project was handled by the Service’s heavy equipment professionals, saving taxpayers close to $200,000 for the project.

Internally, multiple Service programs and departments helped with the development and execution of the program. Those programs include the Service's Water Resources Division, Inventory & Monitoring's Biological program, Ecological Services' Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office, Fisheries and Aquatic Conservation's Vancouver Office, and Connor Shea from the Partners for Fish and Wildlife in California.

External partners on the project included the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Nestucca, Neskowin & Sand Lake Watersheds Council and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

“Like most projects these days, partnerships were huge,” Moroney said. “We could not have accomplished this project without help from internal and external partners.”

The Service also reconstructed the historic slough channel as a part of the project. It was returned to its original path, winding across the lowlands. This will reduce flooding, which will benefit landowners in the Upton Slough watershed basin and the Little Nestucca Drainage District.

It will also improve habitat for fish and wildlife. Dusky and Semidi Island Aleutian Canada geese, which are both identified as species of concern in the Pacific Flyway Council Management Plans, and other migratory waterbirds will benefit from the lowland pasture improvements. It’ll also improve fish passage and fish habitat requirements for federal- and state-listed Oregon coastal coho salmon.

“The bottom line is that the operators left their homes for two weeks, worked long hours as a team to deliver on a common goal,” Moroney said. “Their work and accomplishments on the Upton Slough project should be a model for refuges doing business. These professionals care about the resource, care about refuges, and take a lot of pride in their work – and it shows.”

Our wage-grade professionals -- the people who turn conservation ideas into conservation successes.

Juvenile coho salmon found in Upton Slough

Checking depths for tide gate construction.

Setting a tide gate that helps drain water from Upton Slough to the Little Nestucca River.

Dusky Canada geese are on of the species that will benefit from the work on Upton Slough.

Gary Rodriguez was the project lead. He spent 32 years in public service before his recent retirement.

Story posted 6/26/2020

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish Food for Thought: Scientific Sustenance for Salmon

By: Julia Pinnix, Visitor Services Manager, Leavenworth Fisheries Complex

Photo: Ann Gannam, supervisory fish biologist at Abernathy Fish Technology Center shows the science and machinery behind making nutritious food for fish, Credit: USFWS

Every day that I walk through the grounds of Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery (NFH), I see our production staff at work, tossing pellets of fish food into the raceways while young fish make the water’s surface boil with action. At other times, I see them pushing brooms slowly down the length of the enclosures, pushing waste to the drain without stirring it up into the water column. Fish production work has, in some ways, remained the same for decades. Fish need to be fed, ponds and raceways cleaned, water temperatures and flow checked and maintained.

But one aspect of hatchery work has changed a lot: fish food.Dr. Ann Gannam (now a Supervisory Fish Biologist at Abernathy Fish Technology Center) noted in an article about fish feed (published in 2008) that hatchery fish in the 1930s were fed a range of items: “salmon eggs, fish, oilseed meals, beef and hog liver, spleen, chicken eggs, and horse meat. A feed mixture back then might be comprised of thirds of beef liver, hog liver, and salmon guts, chopped and mixed at the hatchery with salt added to thicken and bind the mixture.”

By the 1940s, wheat, cottonseed meal, and soybean meal might be added. When Leavenworth NFH was built, it included three large buildings: the nursery, the maintenance shop, and a cold storage building. The cold storage building has two enormous walk-in freezer spaces where meat was kept. Fish feed trials at Leavenworth NFH in the 1940s tried out combinations of beef liver, hog spleen, salmon viscera and offal, diatomaceous earth, apple pomace, and rockfish. First, large electric grinders were used to reduce the size of the ingredients. Then the meat mixture was forced through different sized ricers to make pellets. This could take hours.

Reading through Entiat National Fish Hatchery logbooks from 1943-1944, I see that the supervisor meticulously recorded in clear, careful cursive handwriting the hours worked by his three staff. Cleaning raceways, ponds, and troughs took, on average, 3.6 hours per day. Feeding fish took 3.2 hours daily. Preparing food for the fish occupied an average of 3.1 hours a day, including defrosting meat and fish, grinding it, extruding it through ricers, then sifting it to get the right size pellets.

Photo: Staff measure out fish food in preparation for feeding time, Credit: USFWS

Preparing fish food was done on-site for decades. Commercially-made moist feed became available beginning in the 1950s, but it still had to be kept in cold storage. Commercial dry feed, no refrigeration required, reached the U.S. market by 1955, but was not used at our hatcheries until 2001, after it had been tested and improved. Modern dry feed is made from a proprietary blend of materials, including fish, poultry, wheat, feather meal, corn gluten meal, pork blood, and brewer’s yeast, along with added vitamins and minerals.Ingredients continue to change. An intriguing new option is insect meal. Located on the Columbia River, Abernathy Fish Technology Center provides technical assistance in natural resource conservation to the Service and its partners, primarily in the western U.S. Racheal Headley, in Abernathy’s ed levels in Nutrition & Physiology Program, concluded a study in July 2019 on insect-based feed for salmon.

Photo: Staff walk the raceways several times a day feeding fish, Credit: USFWS

As is typically done with new and alternative ingredients, feeding trials are run using the ingredient at graded levels in the diet. Factors such as growth, survival, body composition, and digestibility are examined. Insect meals are being evaluated as a potential replacement for fish meal in aquafeeds because many insect species could be used as feed ingredients. Black soldier fly larvae meal was chosen because it has shown some promise for salmon in other studies. Three diets were tested: a control with no insect meal; then two diets, one with 25% of the fish meal replaced and the other with 50% of the fish meal replaced with insect meal. The fish used were coho, and the trial lasted 75 days. Results are currently being analyzed. Research into fish feed continues to explore new sources of material and to match the best feed to the right species of fish. Meanwhile, our hatchery workers continue their daily rounds, feeding fish, cleaning ponds and raceways, and keeping the water cool and flowing, just as they have done now for eighty years.

Note: This article originally appeared in the Wenatchee World as part of their “Fish Tales” series.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birding: How to get started and make it count for conservation

By: Rylan Suehisa - Public Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based out of Portland, OR

Spring migration continues to roll along as upwards of 3 billion birds make their way north toward their summertime breeding grounds. Wave after wave sweeps through the Pacific Northwest, giving us all a calming seasonal spectacle that brings with it a bit of normalcy during these uncertain times. And if you’ve been following along with our #MigrationMondays content, we hope that you’ve been enjoying paying closer attention to this incredible spring migration event as it happens in real time.

Maybe you’ve already taken that next step in helping birds along the way by planting native plants and avoiding harmful pesticides, or begun building birdhouses for birds that will spend the summer in your yard. If you are seeing positive results from your efforts, congratulations - we are stoked!

Here’s another thing you can do to help birds along their way - simply take time out of your day to watch birds and take note of your observations. In addition to the benefit to your well-being that this “pause” from the world provides, birdwatching benefits birds too. By noting what you see and submitting those observations to a database such as eBird, you are expanding our knowledge about where birds go, how they get there and what they need along the way.

Birding 101

“Hold on,” you might be saying. Maybe you are new to birding and wondering how to get started. Perhaps you’ve been an appreciator of birds for a while, but are uncertain about how to take the next step into birding as an activity. Below is an infographic that we hope you will find useful as you get started.

For more on the subject from a Service bird biologist and certified “Bird Nerd,” check out this piece written back when we were celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a landmark agreement that laid the foundation for bird conservation as we know it today.

Why It Matters

As you begin to bird and get more comfortable with the activity, your observations will make a difference. By noting what types, how many and where you are seeing birds and submitting that data to a database such as eBird, you are contributing to a remarkable global knowledge-base. Here’s what the eBird team has to say about how your and thousands of other birders’ observations make a difference for birds:

eBird transforms a global birding community’s passion for birds into critical data for research, conservation, and education. Half a billion bird observations have been contributed so far. When combined and analyzed appropriately, these data enable next generation species distribution models that provide full life cycle information about birds at relatively fine scales across broad spatial and temporal extents. These model results inform novel conservation actions, from site-specific information about the occurrence and abundance of birds, to looking at patterns of species abundance across continent-spanning flyways.

Answers to large-scale questions such as “Where do birds go and how far do they travel?” to specific ones like “where do birds stop along the way so we can prioritize conservation of those locations?” come from citizen science data that you and many others submit. Indeed, the data you collect about birds you count from your yard, local park or National Wildlife Refuge goes a long way towards their conservation.

Now that you know more about this hobby and its impact, we hope you feel more comfortable taking the next step towards discovering an exciting way of experiencing nature. With that, we wish you happy birding!

#USFWS#USFWS Pacific Region#migration#spring migration#birds#birding#nature#science#MigrationMondays

546 notes

·

View notes

Text

#MigrationMondays: Install Homes for Resident Birds

By: Rylan Suehisa - Public Affairs Officer based out of Portland, OR

Often, when we think of spring migration, we might imagine more northern destinations being the objective for traveling birds. For birds such as chickadees, wrens and sparrows though, the Pacific Northwest is the final destination where these birds will settle down to build nests and raise young. If your yard has the materials and food resources, your bird-watching highlights could extend through the summer and into the fall.

And maybe you’re like me, sharpening your aesthetic sense and expanding your DIY knowledge through projects around the house. I’m paying more attention to my comfort with all this time at home and that sparks ideas. Do you also get to the bottom of your to-do list and wonder “What else can I do?” We can put all that bubbling DIY energy and attention to comfort towards installing houses for resident birds.

An icicle-laden birdhouse after winter rains in North Dakota.

Photo Credit: Krista Lundgren/USFWS

Here are several things to keep in mind as you get started. A link with all the specifics follows these general concepts.

Design with a specific bird in mind but be open to surprises

When it comes to birdhouses, there's no such thing as "one size fits all." You need to decide which bird you want to attract, then design a house for that particular bird. Don’t get too hung up over what happens though. It’s important to remember that nature and birds pay no mind to the rules that humans set. So don't be surprised when you find tenants you never expected in a house you intended for someone else.

How elaborate you make your bird house depends on your personal sense of aesthetics. For the most part, all the birds care about is their safety and the right dimensions: box height, depth and floor, diameter of entrance hole, and height of hole above the box floor.

Placement is key

Where you put your bird house is as important as its design and construction. No matter how perfect your nest box, if you don't have the right habitat, the birds aren't likely to find it.

There's lots you can do to modify your land to attract the birds you want to see. It can be as simple as putting out a bird feeder or as ambitious as re-landscaping your yard with native plants and fruit-bearing shrubs or installing a pond with a waterfall.

But it's much easier just to identify the birds most likely to take to your backyard as it is and put the appropriate nest box in the right place.

Be an attentive and responsive landlord

Part of being a responsible bird house landlord is your willingness to watch out for your tenants. Bird houses should be easily accessible so you can see how your birds are doing and, when the time comes, clean out the house.

A Service employee inspects a birdhouse at Seatuck NWR. Credit: USFWS

Monitor your bird houses every week and evict unwelcome creatures: house sparrows, starlings, rodents, snakes, and insects. Proper box depth, roof, and entrance hole design will help minimize predator intrusions and harm to the birds within. Sometimes all it takes is an angled roof with a three-inch overhang to discourage access to mammals such as raccoons, cats and opossums .

----------

By putting up a birdhouse, you’re creating a safe and well-maintained place for birds, and you’re also creating exciting bird-watching opportunities for you and your household too. From the to-and-fro flitting of the Mama and Papa birds as a nest takes shape within, to the fledging of the absolutely adorable chicks preparing for migration, the summer into the fall will be a must-watch spectacle indeed. Now with these general ideas in mind, find all the in-depth information you need to get started on your own birdhouses here.

Tune in next week as we look at bird-watching and how this fast-growing hobby can help expand our knowledge of birds and the ways that they travel.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tip for Beginning Birders. Infographic by Sarah Levy/USFWS

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#MigrationMondays: How You Can Help Birds On Their Way This Spring

By: Rylan Suehisa - Public Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based in Portland, Oregon

In the morning when you wake up during this time of Quarantine, what’s the first thing you hear? If it’s not a family member or roommate bugging you to “Get out of bed already!” - (I’ll raise my hand to that), chances are you’re greeted by a chorus of bird song.

As the current pandemic has many of us sheltering in place, we are experiencing nature more acutely. Instead of turning on the TV for morning commute traffic updates, we can take an extra minute or two to focus in on the birdsong coming in through the window, or note a flurry of actively-foraging birds in a nearby Douglas Fir tree. With current circumstances the way they are, we have more time to appreciate the little things.

Yet behind these much-needed moments of zen lies an incredible phenomenon - spring migration. With more than three billion birds heading north throughout North America creating a beautiful seasonal spectacle, migration is something to get pumped about.

Western tanager, credit: Peter Pearsall/USFWS

We’ve just celebrated World Migratory Bird day (WMBD), where a whole flock of bird lovers from around the globe gathered together in collective awe and appreciation of birds’ incredible springtime journeys. Showcasing the inter-connectivity of bird conservation through many virtual events around the world, WMBD participants stirred up a gust of momentum that has us thinking about the remaining duration of spring migration. How can we do our part throughout May into early June?

With much of the world under lockdown, these action items should follow guidelines set forth by your local and national leaders. Here in the Pacific Northwest, that means sticking close to home for now. So from your garden, to your porch, to the grocery store, join us in the coming weeks as we explore some of the ways we can help birds along their journeys.

Let’s get started! First up…

Make informed choices about the plants in your garden.

Black-capped chickadee with insect at William L. Finley NWR. Credit: George Gentry/USFWS

It’s hard to imagine that a tiny nickel-sized bird such as a Wilson’s Warbler travels 2,000 miles or more on its way from wintering in Mexico to northern nesting grounds each year, or that migrating songbirds such as western tanagers, vireos and flycatchers expend up to half their body weight to make their own journeys north. Given these circumstances, it’s not so difficult to grasp a songbird’s need for breaks along the way. Once they’ve landed they need to refuel their tiny bodies to recover and complete the rest of their journey.

These waves of small yet determined travelers often fan out across wild spaces, but also urban areas, voraciously eating any small insect they can find. Yet depending on what’s growing in your garden, a songbird might land to discover a bountiful buffet waiting, or nothing more than a colorful but empty picnic table. A couple keys to meeting the stopover needs of a bird on migration are planting native vegetation and eliminating all use of pesticides, especially those known as neonicotinoids, from your yard.

Native plants provide critical supplies of pollen and nectar for a host of pollinating species including caterpillars - delicacies that many spring migrants love! Non-native plants may have the vivid colors and more showy flowers, but some do not provide nectar nor pollen and research shows that native pollinators generally visit more native flowering plants. Birds in turn visit these same plants in search of the abundant insects found among their leaves. Native plants also have many advantages since they are accustomed to the local climate and native soils, and once established they need minimal care.

As you head over to your local nursery in search of native plants, inquire about that establishment’s use of neonicotinoids, one of the most prevalent pesticides around the world today. “Neonics,” as they are called, are highly toxic to pollinators such as butterflies and bees, but also toxic to birds that eat the dosed insects. A growing number of nurseries are specifying where these pesticides are in use among their offerings so you can be sure that the native plants you purchase will actually bring the insects and birds you’re hoping for.

For more information on neonicotinoids, hear from Regional Refuge Biologist Joe Engler.

For strategies to incorporate native plants into your garden, check out this piece from Regional Bird Biologist David Leal.

Next week, we’ll look into building birdhouses for resident songbirds that will be singing and raising young throughout the summer. Stay tuned!

#USFWS#USFWS Pacific Region#birds#birding#garden#plants#gardening#spring#springtime#ideas#inspiration#quarantine

5 notes

·

View notes