Text

welp, it seems this drawing app has finally died. it was off the play store for a couple years now but was still working fine installed. now it won't update anymore or even work, not sure if it can be moved or installed to a new device

probably not gonna be able to get any new art done for a while until I find a new app with similar capabilities and features and get my tab in working order again :(

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

'While some of the armored rattiles known as shingles live firmly on dry land, and another class, the seashingles, living entirely in the open ocean, some species dwell in the numerous inland bodies of fresh water all so abundant in the Middle Temperocene, with its ponds, lakes and streams conducive to the flourishing of an assorted diversity of life. The pond turtduck (Anatochelymys atla) is one such species of freshwater shingle, foraging at the bottom of ponds with its broad flattened snout to feed on an assortment of food, ranging from algae and aquatic plants to freshwater snails, clams, worms and other invertebrates that it stores in its cheek pouches and chews when it surfaces to breathe. Found mostly across Gestaltia's tropical regions, the pond turtduck, defended by its sturdy skeleton and protective keratinous armor plates, is largely unconcerned with enemies, feeding at its own leisurely pace--though, if an aggressor proves persistent, the sharp raking claws on its flipper-like limbs acts as an additional deterrent, particularly on land where the turtduck is clumsy and unsuited for a quick getaway.'

-----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

'With the explosion of diversity the hammoths had in the Early Temperocene, on the isolated continent of North Westerna, there emerged many unique forms some of which harkened back to the days of the Glaciocene as giant grazing megafauna, and others, as small burrowers but a tiny fraction the size of their cousins. Yet one unique and aberrant species is neither, a medium-sized forager weighing a generous 40 pounds on average, but nonetheless stands out due to its unusual dietary preferences: the splendid tamandmoth (Myrmecomammuthomys glossomagnus), whose long prehensile tongue, a hallmark of hammoths as a whole that enabled them to graze in spite of immense elaborate tusks some bore in the Glaciocene, now proving equally capable of gathering up wood-boring insects like termites, grubs and beetles exposed from their tunnels by its short, pointed tusks, thus taking advantage of an abundant resource that in this habitat is otherwise rarely exploited. While still grazing on the sparse vegetation of the forest floor and relishing fallen conifer cones on the ground, this atypical hammoth has, perhaps surprisingly, converged with various rattiles, zingos such as the moundhound, rhinocheirids and at one time even specialized hamtelopes in the niche of long-tongued insectivore. Yet this is hardly unexpected as, time and time again, different species unrelated and separated by time and space, arrive upon similar solutions to address a common problem.'

------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A heaving grunt from a territorial bull North Mesoterran narwalrus (Odobenoceratos mesoterrus) sends a small, subadult white-cheeked wavewaddler (Otaripterimys ambulus) sprinting to safety, taking advantage of its superior mobility on land to evade the large male's powerful bulk and potentially injurous tusk. Wavewaddlers, the most basal of the bayvers, are an unusual group of generalized omnivores that, while having flipper-like limbs and partly-fused rear limbs to act as rudders when swimming, still possess the ancestral ability to rotate their hip under their bodies and bear weight on their flippers, unlike the rest of their bayver kin which are far more cumbersome on land, some of which have abandoned the land entirely and fully specialized to the sea. The narwalrus, on the other hand, represents an opposite but equally unusual case within the clade, as it descends from ancestors that were fully marine, but secondarily regained an amphibious lifestyle with the help of stronger forelimb muscles and flexible wrists to seek refuge from large sea-bound predators. Their hind limbs, however are fixed and immobile, merged to form a pseudo-fluke, and thus on land the narwalruses shuffle their two-ton bulk along with rhythmic undulations of their bodies.'

-------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Startled by the rumbling of enormous approaching footsteps, a foraging straight-tusked marmoth (Nanomammuthomys pliodens), a diminutive creature barely four or five kilograms in weight, flees to the safety of its burrow, scurrying past and beneath the stomping feet of towering beasts resembling itself but hundreds of times bigger: a herd of three-meter tall, six-ton maustodons. Despite their tremendous disparity in size, only about twenty or so million years separates the two species: the polar extremes of a sudden, dual trend of insular dwarfism and insular gigantism on the subcontinent of North Westerna. The last of the hammoths, small stunted remnants of their Glaciocene kin, persisted on the landmass, and grew even smaller to exploit new niches, but to combat larger predation that came much later, their greater cousins once more returned to the sizes of their bygone relatives. In between them, hammoths of various shapes and sizes coexist, from sheep-sized mountain grazers to buffalo-sized plains herders, but it is between this two species in particular that the dramatic newfound diversity of a clade almost condemned to oblivion becomes ever so strikingly evident.'

------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

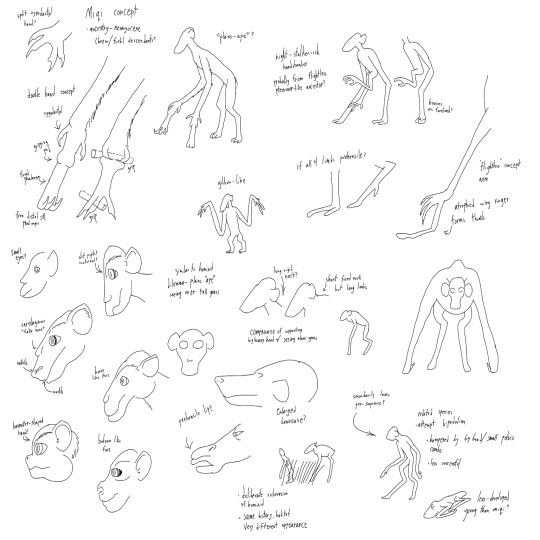

(warning: MASSIVE spoilers ahead for those who have not read the original 2017 version. read here or click away if you don't want to get spoiled years ahead.)

in light of recent news of a certain mouse hitting public domain:

a jumble of unfinished random concept sketches for a part of the story that probably won't be reached for years. also addressing much criticism on the excessive convergence.

again, nothing is canon yet

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#spoiler stuff#non canon stuff

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Unsafe even in their own home den, a nest of colonial molrocks are caught off-guard in a moment of false security as a dwarf earbill (Auriculorhychus minimus) erupts through the sandy floor of their storage chamber to seize an unlucky worker in its snapping jaw-like ear plates. Numerous, omnivorous and prolific, colonial molrocks are plentiful prey for a wide array of subterranean predators. Burrowurms will trail them down their burrows, their long bodies and reduced limbs suited for pursuing prey in narrow tunnels, small fearrets will take up residence within the colonies themselves to pick off any stragglers, and badgebears will relentlessly dig for them, taking advantage of their disorientation when exposed to light to quickly gulp down as many as they can before they can escape. With many dangers threatening them at every turn, colonial molrocks survive by banding together: partly to rely on strength in numbers--and partly to be so numerous that they cannot be consumed all at once.'

-------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

New year, new cover photo!

A happy 2024 to everyone who's followed this blog from the beginning and to those who are newcomers too :)

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#new year#tribb speaks

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Welcome to world, newpup."

"To you I am kind, but world...will not be."

"Now you are weak. World destroy weak. Weak prey-beast to strong."

"But you not weak always. You will grow, be strong. More big. More strong than other. You different. You special."

"World want to destroy you. World want to destroy Us. Them want to destroy you, and Us. But you will be big and strong with many seasons. Stronger than other. Two strong put together. Two strong as one stronger. Two half made one whole."

"Half of the Us who take sky-flame from Them."

"Half of the silent spirits of the pale eye."

"You are both but more. You both but greater. You both at once and more and stronger with time with seasons. The strong lead the Us. One day you lead the Us."

"In seasons and many seasons, you lead in many days. Lead the Us to victory. The strongest will lead the Us and you will be the strongest to lead the Us. Chase off Them from good hunt-land, destroy Them if must. Land for the Us. Hunt-land for Us."

"You will grow and be strong in many seasons."

"When you are strong and big and lead, the unkind world will be prey-beast. Them will flee from the half-spirit. Half-spirit bring Us to greatness."

"Like ash from fire-mountain, burn all, cover all. From ash of fire-mountain grow new life. Strong life."

"Now you are weak, small, know nothing. But you will grow and be strong and learn. Learn to be fire-mountain ash and burn and bring strong new life."

"Welcome to world, newpup. Now you are small and weak but not always. Time come in season when Them will run from your name."

"And your name, new youngpup...will be Ashfall."

--------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot#the calliducyon saga

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Every few years, populations of sand cricklings (Acridiscarabinus gregarius) reach perodic and explosive booms as their numbers swell dramatically. Normally solitary and inconspicuous, the sudden increase of these desert-dwelling, plant-eating beetles inevitably leads to a shortage of food supply in a few weeks' time, and it is at this period of their life cycle that they begin to migrate in enormous groups: traveling many miles at a time, they feed and mate nonstop, depositing their eggs in suitable locations along the way as they form enormous swarms that at times may appear to be dark clouds from a distance, descending onto whatever vegetation they can locate and stripping them bare in a matter of days. During this period, their eggs and larvae develop much more quickly than usual, and they, too, become swarmers in a month's time, born already in their gregarious phase when they emerge during this particular season.

The sudden appearance of so many herbivorous insects in an arid semidesert environment may lead to local epidemics of famine to resident herbivores, which at these times are too forced to migrate or starve. Yet, for the drysanders, residents of one of South Ecatoria's most inhospitable regions, this plague is, conversely, a time of plenty. Seldom are they given such an abundant bounty of plentiful, easy prey whose only defenses are their sheer numbers, and with food and water quite scarce in their homeland, the swarming of the cricklings is considered a blessing. Indeed, in spite of whatever devastation they may cause to the local flora, the drysanders consider these seasons a cause for celebration, with their folktales and songs being ones of joy and thankfulness, citing a specific instance in their history many generations ago, known as the Summer of the Cloud-Bug Feast, when the timely appearance of the swarming bugs was the only thing that saved their people from certain doom in a grim time of conflict and hunger.'

-----

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot#the calliducyon saga

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

'In the scrublands of South Ecatoria, a well-defended porcuswine--a common genus of bumbaa widespread throughout the northern part of the continent--nonchalantly tucks into a rather unusual and unsavory meal: a serving of its own droppings. Porcuswines, and their cavybara kin, which include even the likes of hammoths and piggalo, are hind-gut fermenters, with their stomachs small and simple but their large intestine complex and spacious, allowing them to process more quantity rather than quality. Unlike the foregut-fermenting ungulopes, however, this fermentation of cellulose occurs after the absorbing region of the small intestine, rather than before, and thus valuable sugars and amino acids are lost to the dung. Rather than let these nutrients go to waste, the porcuswines, as do juvenile hammoths and piggalo, opt to an obvious solution: they eat their droppings a second time, allowing it to be re-processed and helping its nutrients be extracted fully.

While such behaviors may seem off-putting and downright disgusting to a human spectator, the boldmarks, who cultivate fruit trees from their latrines and thus have a quite different and more positive cultural perspective of this natural process, see it as but just another natural part of the lives of the animals they observe in their surroundings. In fact, the porcuswine's consumption of its dung specifically has made a powerful cultural symbolic impact in their lore and imagery. To them, just as the twin suns rise and fall, the twin moons wax and wane, the seasons change through the year, and all living things are born, eventually die, and in death catalyze new life to spring forth, the porcuswine devours food, digests it, and expels it to devour it once more--a symbol of the endless cycles of life and nature in its duality of the beautiful and hideous.'

----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot#the calliducyon saga

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A dramatic struggle ensues in the grassy tropical plains of Mesoterra as a bucktooth buntelope (Paracervicricetus scalprudontus) is beset upon by a hungry pack of spotted streakbacks (Myocynomimus dixoni), a hunt that will be no easy task against a well-armed adult with powerful hooves and defensive tusks. In isolation, the animals of Mesoterra have converged quite heavily on similar plains-dwellers native to corresponding biomes on other continents. Here, the small, mouse or rat-like scabbers abundant elsewhere as small scavengers and insectivores have grown to larger and more canid-like predators in parallel to the zingos of distant landmasses, while the rabbeasts, part of a clade of more basal hamtelopes, have in turn produced cursorial long-legged running grazers due to their ecosystem's deficit of the more widespread ungulopes. As such, as form follows function, familiar shapes begin to arise among animals so far apart on the taxonomic family tree--so long as niches remain vacant and ready to accomodate any species able to fill it.'

----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

the month has come once more

it's december again folks

#seasons greasons#meme#shitpost#man after man#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise

602 notes

·

View notes

Text

While a relatively secluded ecosystem, the caverns of Arcuterra have expanded greatly over the last few million years. Consisting of a network of tunnels, chambers and crevices spanning for miles underground, the floor space of the caves have now exceeded those of a small island comparable to Earth's Tasmania-- and has gotten large enough to have several sub-biomes within itself, some levels more superficial and closer to the outside world where the abundance of nutrients trickling in allows the lush forest-like growth of subterranean pseudo-flora, and others beneath the upper layers where groundwater and detritus accumulates, forming stagnant, muddy swamps where, against all odds, life finds a way to thrive.

One of the ecosystem's most abundant animals are the feelerflits: the caverns' only flying animals. Descended from dipteran flies, their forebearers once did lose their wings in their initial colonization--yet over time re-evolved this ability through atavistic mutations once the caves had expanded enough to make flight advantageous again: though now, in pitch black darkness and without vision.

Feelerflits, however, managed to adapt by developing especially-hypertrophied feelers both on their antennae and their abdominal cerci, giving them the ability to detect movement both forward and behind. This, coupled by pressure sensors and long hairs on their feelers, allow them to discern their environment in flight, while olfactory and theroreceptor cells allow them to pick up thermal and chemical signals to recognize food, enemies, and conspecifics.

Most of the common feelerflits (Phantasmusca spp.) are generalist omnivores, feeding on decaying matter, shroomor spores and fungi, but some, in the abundance of resources and lack of competition, have ascended a rung in the food chain. The murksquitoes (Anophelomimus spp.) have become part-time parasites, supplementing their diet of mocklichen spores by biting larger animals such as daggoths, especially females that require additional protein in producing their eggs. Others, the darkdarters (Quadropteroides spp.) have become predators, preying on other feelerflits. With their halteres enlarged to resemble a second pair of wings but used as organs of balance instead, they are agile in the air, seizing other, smaller feelerflit species with spiny grasping forelimbs and using a sharp proboscis to pierce the bodies of their prey.

This abundance of insects, arthropods and other invertebrates has led to other unique specializations among the daggoths: the cavern systems' dominant troglofauna. Many are specialized insectivores, typically smaller species, but also some unusual outliers among the larger kinds.

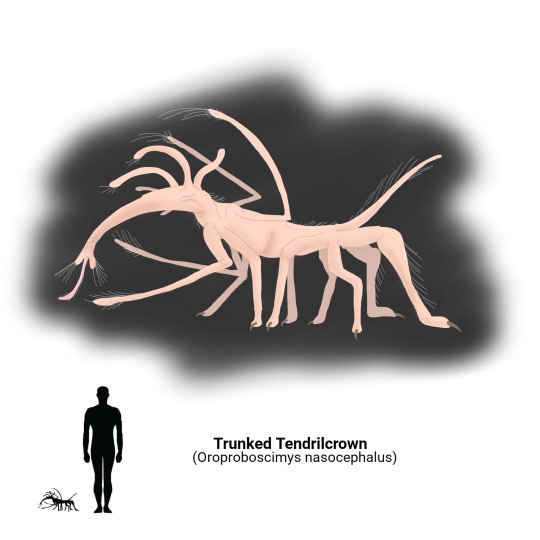

One such creature is the trunked tendrilcrown (Oroproboscimys nasocephalus), a member of the cavehopper family that, unlike its other grazing kin, has adapted an elongated snout from the elongation of its lips, forming a trunk-like appendage with its mouth opening at the end, out of which emerges a long, sticky tongue equipped with small barbs, ideal for piercing through mocklichens to get at the interior, reaching into crevices to pull out rootlike mycelia, and most importantly to raid insect nests and feed on the inhabitants. Its trunklike appendage only contains its mouth, with its nostrils set far back behind the top of its head, keeping the vulnerable orfices far from reach of its biting insect prey.

Tendrilcrowns, like most other cavehoppers, are gregarious creatures that seek safety in numbers from predators like blindmutts and tendriltooths. They use their tail, atypically long for a daggoth, as a scent-marking organ to set territorial boundaries and identify related individuals. Yet, as their social behavior are merely for protection, their individual bonds are rather weak. When startled by predators, they individually flee with powerful thrusts of their leaping hind limbs, displaying little concern for their fellows whose company they only partake in to reduce the chances of individually being caught.

The cavehoppers may be agile and flighty creatures, but in the limited space, not all daggoths share their energetic means of movement. Some daggoths are content with a slower-paced life: especially those that live in the lower levels of the cave systems where fewer food is available and energy is better off conserved.

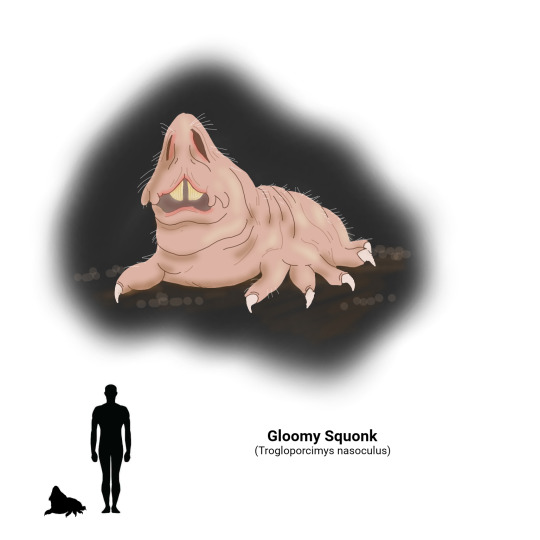

The gloomy squonk (Trogloporcimys nasoculus), one species of the gloomhogs in relation to the biblarodons, lives in the basement-levels of the cavern systems: where the muddy deposits gather into the large, wide chambers into a sort of underground marshland. Here, underneath the organic sludge, specialized filamentuous fungi grow in soggy, fibrous clusters, absorbing and converting the detritus back into biomass that, in turn, is the primary food of the gloomy squonk. Its ghostly eye-like orfices are in fact enlarged nostrils on its inverted, upturned snout, as it has adapted for spending much of its time wallowing in the subterranean swamps scraping off the fungi from the bottom, surfacing time and time to breathe. With larger nostrils as well as a markedly larger lung capacity, it is able to take in more air per breath, allowing it to make the most of the thin, oxygen-poor atmosphere so deep beneath the ground.

Its sluggish demeanor, large fat-storing body and glycogen-storing liver allow the gloomy squonk to survive for long periods without food, in one of the less-hospitable regions of the cavern system, where growths of its preferred forage follow irregular boom-and-bust cycles depending on how much nutrition is available from higher rungs. This, however, makes it an ideal potential meal for younger tendriltooths that may wander down lower crevices to avoid competition from aggressive and cannibalistic adults. However, while slow and typically placid, the squonk is not entirely defenseless. Its jaws, strong enough to tear fungal mycelia from rocky anchors, can also inflict a vice grip onto a would-be predator, after which it submerges into the muddy sludge in an attempt to drown its assailant.

Similarly, while some of the blindmutts became active, pouncing ambush predators, others, the cavegleaners, took on a more slow-paced lifestyle, wandering along as foragers and scavengers, picking on shroomors, insects, small daggoths and carrion, and thus alleviating competitive pressure from the tendriltooths, who now seldom consider them a threat and rarely bother attacking them.

The ridge-headed whiskersaw (Heliconasodon rubrilophus) is one such cavegleaner, often drawn to the leftover kills of tendriltooths to finish off the remains left behind once the predator is sated. Like the tendriltooth, the whiskersaw is equipped with sharp keratinous serrations on its nasal tendrils that function much like teeth. Yet now, with its foraging lifestyle, the whiskersaw now puts its false dentition to a strange use: coiling its two most prominent tendrils into tight spirals with the spines pointing outward, it then rotates them against one another as they uncoil back and forth: forming two abrading "polishers" that cleanly scrape the last residues of meat attached to bones, especially those out of reach of other predators. When uncoiled, these spiny appendages can also be inserted into hollows of bones to access the marrow, or be probed into the burrows of small prey to be extracted from their hiding spots.

The other conspicuous feature of the whiskersaw is of course the two fleshy ridges that adorn its head: the frontmost rims of which are made of highly-vascularized tissue that can be engorged and distended with specialized blood vessels to release a small amount of body heat. These are picked up by the thermoreceptors found on the nasal tendrils of other whiskersaws, in essence being used as a display organ by a species without eyes to see visual cues. Being mesothermic, like most daggoths, the display is a very energy-intensive effort in relative terms, and to the solitary creatures only means one of two things: a dominant male asserting his strength to a potential rival, or a receptive female advertising her readiness to breed. Also like the majority of other daggoths, the undeveloped but precocial young recieve minimal parental care, nursing for only a day or two before being deposited near abundant food sources conducive to their growth and survival.

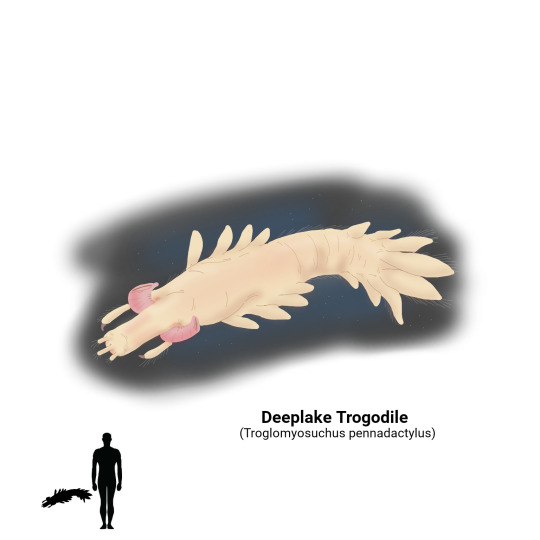

A wide variety of large fauna now thrive among the drier regions of the caverns, which, while still smaller than surface animals due to the more limited space and resources, nonetheless reach impressive sizes for a cave-dweller. But the aquatic biomes of the caverns are not left out by such trends, as some aquatic daggoths have grown quite large, in particular the deeplake trogadile (Troglomyosuchus pennadactylus) which can reach lengths of up to a meter long or more.

While the tendriltooths are the top predators of the land, the trogadiles are the apex carnivores of the underground rivers and lakes where an impressive array of organisms thrive: aquatic insects, shrish, pescopods, hampreys and tubesnouts alike, dependent on a base producer of chemosynthetic bacterial mats and aquatic meatmoss, growing in thorny fronds like animal kelp. All of these are food for the trogadile: not a picky eater, it catches food with its muscular fused nasal lobes as well as two smaller tendrils equipped with sharp claw-like points, and using its extensible snorkel-like nostrils to breathe at the surface every few minutes, sometimes lying motionless just below the surface with only its snorkels exposed, waiting to strike at unwary prey.

Their specialized limbs, modified into flipper-like paddles, undulate rhythmically to propel themselves through the water, but, conversely, now make them practically immobile on land as grown adults, entirely helpless and vulnerable if beached. Young individuals, a few inches long at birth, however can manage a clumsy scuttle across dry land, enough to be able to disperse into other bodies of water. Once grown, they are permanently waterbound, though populations can still intermingle genetically despite isolated pools being separated, due to the amphibious capabilities of the juveniles.

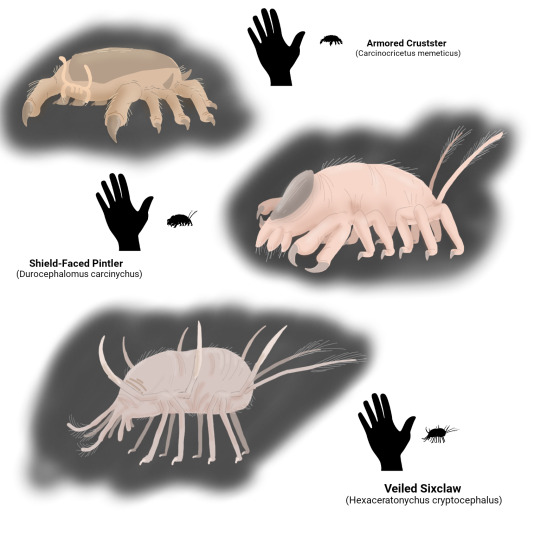

Many branches of the daggoth evolutionary family have thus produced a wide variety of some of the strangest and most alien-looking forms ever assumed by a rodent: to such an extent that many are scarcely ever recognizable as such. Many of these arise from derived lineages, but, from the gothtles, one of the most basal lineages, bizarre yet oddly familiar forms too have since emerged. These animals, in their basal forms once top predator of the caves, now find themselves at the bottom of the food chain, preyed upon by their distant kin: while some such as the xenomures adapted to flee and hide, others armed themselves with strange weaponry to to ward off and injure their enemies.

The veiled sixclaw (Hexaceratonychus cryptocephalus) is one such unusual species that, when threatened, conceals its face and sensitive nasal tendrils in a fold of thick skin as it curls itself up into a tight ball: leaving only six prominent defensive spines exposed. These long, horn-like projections are, surprisingly, actually elongated claws: attached to mobile, specialized digits, they can point in any direction to painfully stick into a predator's mouth, and, even when moving about and actively foraging, the sixclaw bears its weaponry in arms, raised above and behind its body to make it difficult to grab. Able to move together, they can pinch the tendrils and toes of an enemy, hard enough to draw blood, even if successfully picked up.

This ability for the digits to grip in junction has been put to good use by some species. The shield-faced pintler (Durocephalomus carcinychus) specifically has hypertrophied the first two pairs of its digits to use almost as grasping pincers, able to partly oppose and each equipped with a large, retractable claw. These serve it good use in excavating burrows, tearing apart food, defending itself and, most remarkably, used in intraspecific combat. Males can be up to twice as big as a female, and sport greatly enlarged claws and a larger keratinous facial shield that, while used in the females merely to protect their faces while burrowing, are defenses for males when they fight over territory, mates and resources, lifting each other up and tossing each other away as they tussle for dominance, with the losing combatant occasionally losing a few digits in the process.

These defenses, armor and burrowing abilities all reach their peak in the armored crustster (Carcinocricetus memeticus), a smaller and more placid relative of the pintlers that has evolved a more compact body and a single enlarged shield covering most of its back that, with its sharp-spined edges and smooth curved shape, makes it resistant to all but the most specialized of predators. Its powerful front claws are primarily used for digging, while its back, reinforced by a thick and sturdy spine with multiple interlocking vertebral processes, allow it great strength for its size, able to use it for leverage to wedge itself under large stones or into crevices, both to make itself inaccessible to enemies trying to fish it out of its hiding spots, as well as access small invertebrate prey taking shelter underneath.

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#biome post

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

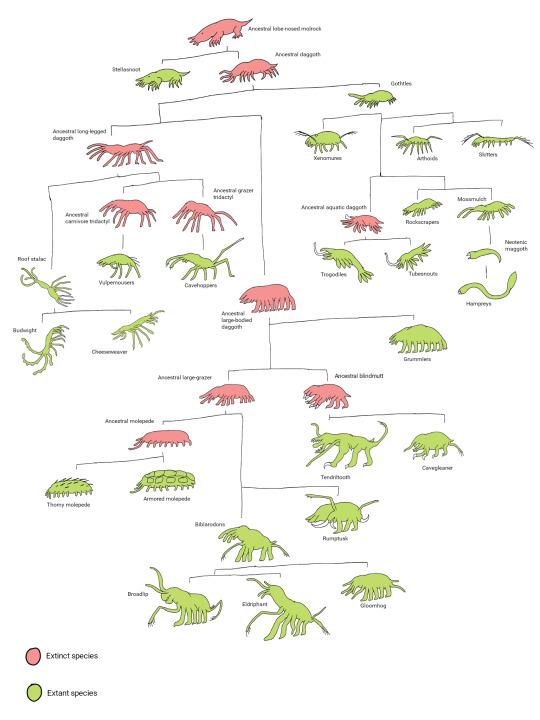

From a single founding species descended from the stellasnoots that found a suitable home in the secluded caverns of Arcuterra, the daggoths, a clade of subterranean molrocks of distant relation to the rattiles, have since diversified over the last 25 million years in isolation. As the cave systems naturally expanded over the course of many millennia, the ecosystem too grew bigger, as it created more room for a wider and more diverse range of species to thrive.

Over millions of years, the upper chambers of the cave system became more open to the surface, resulting to not only a slight but significant influx of oxygen into the ecosystem but also nutrients from the surface, such as organic detritus and the abundant droppings of transient species such as roosting ratbats that nest in the surface chambers, washed down into the caves by rain. These fuel the abundant growth of bacteria, mocklichens and meatmoss, the cavern ecosystem's producers in the absence of plants and sunlight. With an abundance of food, space and, relatively speaking, oxygen, the life of the caves have since grown more diverse and complex than ever before.

Many of the daggoths have remained unchanged from the first forms that were the earliest colonists of the caves. The gothtles, small, mouse-sized insectivores, continue to stick to the ancestral lifestyle, as small, slow-moving ambush hunters that relied on stealth to pounce on insects. Yet the ancestral niche now comes with one drastic difference: they are no longer the apex predators of their environment. Abundant and fast-breeding, the gothtles are now the lower rung of the food chain as larger predators have since evolved from other branches of their kin.

While slower basal gothtles now rely on camouflage by scent and touch to evade enemies, numerous lineages have since evolved speed and evasiveness in order to outpace their predators. One such group are the xenomures, such as the four-plumed xenomure (Xenomuris tetradactylopluma), with long, slender legs that allow them to scurry quickly across the fungal and meatmoss mats to escape their enemies and hide among the maze-like growths to lose their enemies' trail. Two pairs of modified digits act as antennae fore and aft, giving the xenomures a vivid perception of obstacles in their surroundings while moving quickly in the pitch black darkness. These timid omnivores, in many ways, have come to be the caves' ecological parallel to "typical" rodents like furbils and duskmice on the surface, with some even harvesting and storing fruiting pods of mocklichens in burrow larders to eat later, and thus helping the mocklichens proliferate to new areas.

Other lineages of the small gothtles have also evolved more active lifestyles as dynamics of the ecosystem have changed. Some, such as the long-bodied common skitter (Longicorpomys polypus) developed slender bodies and shorter limbs to specialize in hiding in small crevices in the rock walls, well-protected from predators, where they can feed on the fungal mycelia, the buried "roots" hidden underneath the organic soil-like detritus mats covering the cave floors. Others have become small hunters of their own right, paralleling the chrews and scabbers of the surface, like the earthumb arthoid (Dactylotomys auricheirus), equipped with two front digits bearing pointed claws positioned next to its head almost like ears, that it uses to root out small prey, such as insects, nematodes and wormlike maggoths out of their burrows and out from growths of mocklichens and meatmoss.

Virtually every surface of the cavern system has offered a habitat for life, including the walls and the ceiling of the caves, with the walls and roofs forming elevated "branches" and dangling "vines" of various vegetative plant-analogues, which are fed upon by "browsers" adapted to reach high up on to access fungal growths inaccessible to other ground-dwellers.

The ceilings, in particular, are abuzz with a surprising diversity of organisms dwelling amidst the overhanging stalactites. In particular, the dangling "vines", in reality complex filamentous fungal hyphae nourished by a symbiotic relationship with chemosynthetic bacteria, produce buds that exude an odorous scent, that draws in the feelerflits: flying insects descended from dipteran flies that, with long and very sensitive antennae equipped with tactile, thermal and olfactory receptors, have secondarily regained their power of flight and are able to navigate even without sight and home in on the buds that produce nutritious carbohydrate-rich liquids in return for it spreading its spores.

One descendant of the roof stalac has since adapted to exploit this relationship. The bulbous-snouted budwight (Nasofungiosus imitator) has developed specialized bud-like growths at the end of its nasal tendrils, that sport modified sebaceous glands that excrete a scent similar to those of the vine blooms, the chemicals of which it acquires and secretes by eating the blooms themselves. Then, lying in wait, anchored onto the surface of stalactites or perched amidst the vines, it waves its tendrils in the air in anticipation of an unwary feelerflit blundering into its trap, to be ensnared by seven long and flexible tendrils and passed into the mouth to be eaten.

Curiously, despite its purpose of mimicry, the budwight's tendrils in fact look nothing at all like the vine buds, being simple enlarged growths at the ends of the knobbly nasal appendages. In a world of darkness, appearances are almost entirely insignificant, as prey and predator alike perceive their surroundings with sound, smell and touch, as well as other more remarkable senses like thermo- and electroreception. As such, mimcry revolves around these senses: not even a vaguely-similar imitation to a sighted creature, but a deception at least sufficient to trap its equally-blind prey.

Of the various small daggoths that populate the caves, however, none are as divergent and unconventional as the maggoths: a lineage of neotenic descendants of the mossmulch, a more typical-looking daggoth whose life-cycle has taken unexpected turns to produce one of the greatest regressions in complexity second only to the shroomors.

Measuring only a centimeter or less, the maggoths, such as the basal lichen maggoth (Vermimys simplisticus) are extremely simplified creatures: their respiration takes place almost entirely through their permeable skin, their skeletons, save for their ossified mandible and maxilla, are completely made of only cartilage, and they move entirely through two sets of muscles, an inner layer of longtidunal muscles and an outer layer of concentric muscles that contract and relax alternatingly to undulate them forward. This body plan arose from the mossmulch's early gestation lasting only a few days and producing barely-developed young, basically just self-sufficient and free-living early-stage embryos, adapted to feed constantly on meatmoss and mocklichens by tunneling through them, and, with an abundance of a reliable food source, some species eventually became neotenic, no longer developing limbs and nasal tendrils and ossified skeletons, and simply reproducing in a larger version of their quasi-larval state.

The simplified anatomy and reduction of surplus organs has allowed maggoths to be quite successful in the vast expanses of the subterranean caverns. In particular, their very simple bodies has reduced their development to but a few days, allowing them to shorten their generations to as little as three or four weeks: at the age of twenty-one days, maggoths are already sexually mature and can mate, bearing litters of up to a dozen or more wormlike quasi-larval young at a time once every five or six days. These 3-4 millimeter-long newborns feed off skin secretions made by the females for the first few hours of their life before departing for good, in a last remaining hint of mammalian history in a species so far removed from a typical mammal's form.

Another, unlikely advantage of their simplified anatomy is that it requires far less oxygen, which coupled by their incredibly small body sizes and their respiration through their skin, has led one lineage into a new frontier: the waters of the subterranearn rivers as well as the underground sumps that form bodies of water such as ponds and lakes. Thus arose the hampreys: the first ever aquatic lineage of hamsters on HP-02017 to evolve fully-aquatic respiration and thus be entirely independent of breathing air at the surface. Specialized vessels directly branching from the heart absorb oxygen diffused through their permeable skin, and thus their lungs have been reduced to simple sacs regulating buoyancy. Perhaps more remarkable, however, is the marked reduction of their nervous system, especially the brain: their simple lifestyle and unusual respiration had no need for such an energy-hungry organ as a complex brain, and thus in the hampreys this otherwise very vital organ, once the pride of mammals in their complexity, now has completely atrophied to basically but a brain stem, capable of little more than basic bodily functions and responses to external stimuli, moving through the water in jerky, wiggling movements toward the taste and scent of food and away from the vibrations of danger.

Some hampreys, such as the rasping hamprey (Vermicthymys micronis), are independent creatures teeming in the underground ponds and lakes, scraping off mats of chemosynthetic bacterial colonies using their jaws: an ossified mandible and maxilla bearing two pairs of gnawing incisors--basically the only remaining visual vestige of their rodent ancestry. Some, however, have specialized these remnant teeth for another purpose: the sanguine hamprey (Atrocivermimys haemophilus) has developed elongated teeth and a "lip" that allows its mouth to function as a suction--enabling it to attach to other aquatic daggoths such as tubesnouts and trogadiles and parasitically feed off their bodily fluids.

Not all daggoths are small, however. In the recent eons, as food and space became more available as the caverns grew and became more oxygenated, some of the daggoths began growing in size. While still small compared to outside surface animals, reaching only a maximum of 90 kilograms in the largest "grazers", their size is nonetheless an incredible achievement given their environment and evolutionary history.

The lineage that would give rise to their largest species eventually diversified into low-level grazers, higher-level browsers, generalist omnivores and specialized macro-predators. But most basal of these are the grummlers, with the largest species being the giant grummler (Macroabyssomys maximus). These represent the earliest lineage of daggoths that began expermenting with size, with them resembling the basic daggoth but simply larger. With their increased weight, their multiple digits became more columnar to support their bulk, their reduced metacarpals forming equivalents of shoulder blades to anchor powerful limb muscles, while their phalanges grew stronger and thicker and developed a bony heel-like protrusion on the second-to-the-last phalanx to support a fleshy "sole" pad: in essence turning the spindly fingers of the smaller daggoths into sixteen proper "legs".

The greater grummler is a large and indiscriminate omnivore, feeding on mocklichens, meatmoss, bacterial mats, arthropods, smaller daggoths and carrion. Depending on the species, the several species of grummlers either lean toward a more "grazer" side or a more "carnivore" side: a distinction that is less drastic than surface animals given that some of their "plant" equivalents are technically animals as well, making them more accurately "meat-grazer omnivores" or "carno-herbivores". This dietary ambiguity of this lineage would lead to the evolutionary split between the "grazers" such as the molepedes and the biblarodons, and the predators such as the blindmutts, with the grummlers themselves representing a more ancestral state of this divergence. Indeed, leaning more on the "grazer" side, the giant grummler itself sometimes falls prey to smaller grummler species with more carnivorous tendencies, especially targeted if sick, young or old.

As larger-scale predation began to emerge among the macro-daggoths, a trend akin to surface animals started to arise among them--an arms race between increasingly armed predators and increasingly defended "herbivores", with hunters specializing to take down prey larger than themselves, and large prey developing weapons to better fend off would-be assailants.

One of the most notable examples of this would be the molepedes: a clade of macro-daggoths that developed elongated bodies and short limbs that allowed them to graze closer to the ground, feeding on filamentous, low-growing mocklichens that, in a loose sense, could be considered an analogue of "grass". These slow-moving creatures were afforded ample protection by their size alone in the earlier days, but as predators too began to grow, the molepedes gradually found themselves becoming outmatched. Over time, the ancestral soft-bodied molepedes disappeared entirely, too vulnerable to the new predators, but from it emerged two lineages: the thorny molepedes and the armored molepedes.

The common thorny molepede (Echinopolypodomys spinosus) repurposed many of the sensory bristle hairs of its body into defensive spines, covering its back, its flanks and even its nasal tendrils. These spines, barbed and loose like porcupine quills, embed painfully into a would-be predator's skin and remain stuck in the flesh as they break off. As a warning, they exude a distinctive scent from specialized anal glands that previously-quilled predators quickly associate with a painful experience.

However, while an effective means of self defense, the thorny molepede's defensive spines pose a significant challenge to its other routine activities: specifically, when it comes to mating. Thorny molepede courtship is an awkward affair, with both partners releasing odorous pheromones to communicate their amorous and non-hostile intentions. Once they reach a mutual agreement, they then very slowly and gingerly back into each other, until their rearmost quills barely touch, and the male, fortunately endowed with elongated reproductive equipment, is able to complete his job from a safe distance.

A less socially-challenged relative of the thorny molepede is the armored molepede (Armopolypodomys edurus), which is a far more gregarious creature than its spiny cousin and gathers in small groups of up to ten to twenty individuals at a time. Rather than spines, the armored molepede instead has fused its hypertrophied, hardened bristles into tough keratinous scutes, which form a coat of plated armor nigh-impenetrable to the claws and teeth of its enemies. When threatened, groups of then huddle together and press themselves down, concealing their vulnerable limbs and nasal tendrils and exposing only their armored backs. Their strategy is one of persistence: eventually, after hours of clawing and biting to no avail, most predators simply give up the hunt and leave to find easier food elsewhere, and once danger has passed, the armored molepedes once more unfurl and carry on their usual grazing.

Both types of molepede tend their young with a significant amount of care until their defenses grow in, even if only passively, with their numerous litters of up to twenty young at once huddling between the adults' legs, afforded protection by their armored or spiny backs. They are, however, quite precocial, grazing and moving on their own shortly after birth, and, once sufficiently developed and defended at the age of five or six months, gradually disperse from their parent to lead an independent life.

Such defenses have become a necessity for the great grazer daggoths, as predation became more of a significant threat with the evolution of the cavern system's first proper apex predators, the blindmutts. Earlier forms simply preyed upon smaller daggoths such gothtles and xenomures, but, as prey species increased in size, so did some predators, leading to the development of some advanced blindmutts able to tackle large prey such as molepedes, biblarodons and grummlers as well.

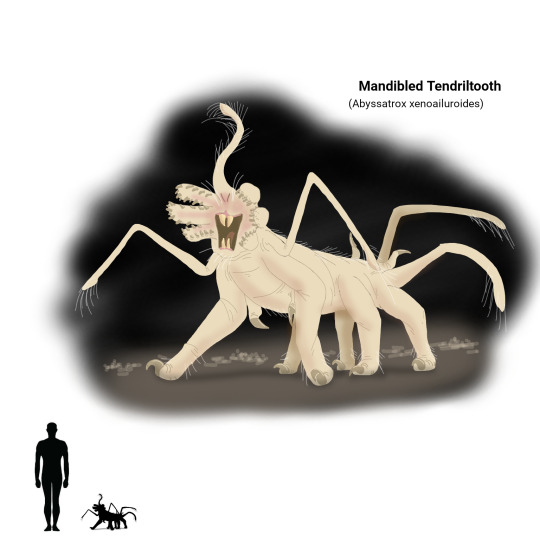

The mandibled tendriltooth (Abyssatrox xenoailuroides) is, in the Middle Temperocene, the caverns' undisputed apex predator: even if it grows only to the size of a large house cat. Its most notable adaptation is the development of sharp, hooked keratinous spines on six of its seven nasal tendrils, which have become thick and muscular and adapted for gripping: in essence becoming six additional jaws with false "teeth". Two of its foremost digits, its central nasal tendril, and its two rear digits act as sensory feelers able to navigate its surroundings with a delicate sense of touch, while it homes in on prey with a powerful sense of smell and hearing. Once it locates its prey, it tries to grapple it with an ambushing pounce before using its six main limbs to anchor itself with its claws, and using its toothed tendril-jaws to secure a firm grip on the prey's neck before using its true teeth, sharp dagger-like incisors, to inflict a fatal bite to the prey's neck. As it targets prey larger than itself, the tendriltooth may take several days to eat its fill, and will camp out next to the carcass over the following days, fending off rivals and scavengers that may come to steal its prize. As its prolonged feeding lasts for a duration long enough for putrefaction to set in, the tendriltooth has evolved an extremely powerful set of digestive juices that allow it to continue feeding on even decomposing meat. Eventually, however, once it has sated its fill, the rotting carcass is then abandoned, and now unguarded, a buffet of scavengers then descend on the carcass, ranging from insects and worms to maggoths and xenomures to even rumptusks, vulpemousers and grummlers, all clearing up the residues the tendriltooth leaves in its wake.

Tendriltooths may reign as top carnivore, devoid of any predators of their own, yet their existence is still a precarious one, as they are few and far between given their placement on the food web. Throughout the entire cavern ecosystem, filled with millions of daggoths of different species, there are never more than a few hundred adult tendriltooths at any one time, being solitary and territorial, as they need plenty of space to sustain themselves. Tendriltooths are fairly prolific, with litters of up to twenty to thrirty tiny offspring at a time, but these small but precocial offspring, independent after only a few weeks, have a rather high mortality rate: during their early youth, where they prey primarily on insects, they are indiscriminately themselves prey for various medium-sized carnivores such as vulpemousers and smaller blindmutts, and, once they themselves graduate to medium-sized carnivore status hunting larger prey like xenomures, now have to contend with adult tendriltooths who will target the subadults to get rid of potential competition. However, should a lucky tendriltooth survive its precarious first two years, a feat accomplished by less than five percent of all juveniles, it is assured a niche of apex predator, unbothered by any other creature and with only another adult tendriltooth to fear.

------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#biome post

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cladorgram of daggoths in the Middle Temperocene.

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Like something out of the fear-stories told by the elders around the flame-gift, a grotesque aberration, dead before birth, is brought forth lifelessly into the world, much to the horror and distress of the herders who bore witness. In the drier seasons where the favorable forage dwindles, the horn-herders, half-domesticated cattle of the highbrows, are forced to make do with bitter, less-palatable vegetation. But some of those harbor a sinister secret, as a few poisonous cloverferns, such as the cursed eye-weed (Oculoflorus cyclopus), contain toxic substances, some of which are capable of interfering with cellular processes and are generally used to deter insects. When ingested by pregnant female horn-herders, however, these natural defenses can display serious and lethal teratogenic effects on the developing embryos: most importantly, a failure of the two hemispheres of the brain to divide, and with this, a complete craniofacial disfigurement that leaves the unfortunate and usually stillborn calf with a singular fused eye and no nasal tract.

But the highbrows do not know this. To them, these occasional freaks were the work of evil and frightening forces of nature beyond their understanding. While some are well aware of the correlation of the plants with the gross malformation of their livestock, hence its name, their folklore tells of a far more colorful interpretation. Long ago, the elders say in tales passed down generations, there was the wicked One-Eyed One, who climbed into the wombs of expecting mother-beasts and devoured their unborn young from within. But from the pleas of the people and their laments in song, the great spirits who commanded the seasons at last intervened and imprisoned the One-Eyed One within the cursed eye-weed plant, sealing it away inside its blooms which are said to somewhat resemble an eye. But, as their legends then ominously conclude, the One-Eyed One still struggles to be reborn, and during the spring and fall, when the seasons are in transition and the great spirits are distracted, it attempts to no avail to manifest itself from the horn-herder calves, but failing and perishing time and time again.'

-------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#art one shot#the calliducyon saga#tw body horror

90 notes

·

View notes