#withholding labor is how unions negotiate for better rights

Text

I’m so happy for them

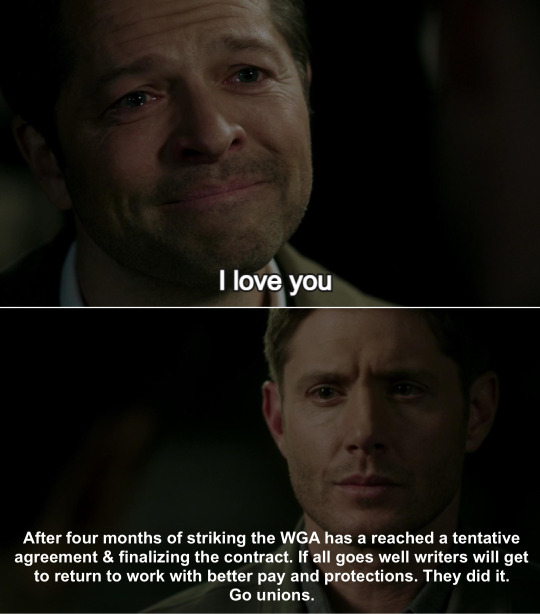

[Image Description: Castiel from Supernatural is saying I love you, underneath is an image of Dean Winchester with the caption: “After four months of striking the WGA has a reached a tentative agreement & finalizing the contract. If all goes well writers will get to return to work with better pay and protections. They did it. Go unions”]

(Source)

#wga solidarity#wga strong#after months of watching union busting and anti union tactics#wga is coming out strong#hopefully sag is next!#writers strike#support unions#wga strike#sag strike#supernatural meme#destiel#destiel meme#workers rights#fuck the amptp#destiel news#mine#we’ve hit the note amount where people start fighting in the notes#stop fighting kids#but also the strike was absolutely necessary#withholding labor is how unions negotiate for better rights#the CEOs are multimillionaires who refused to pay proper wages#they needed to receive heavy losses so they’d actually come to the table listen to union demands

74K notes

·

View notes

Photo

IN THESE TIMES

When I ask Bernie Sanders about the surge of teachers’ strikes that swept the country earlier this year, he perks up, applauding the teachers’ display of working-class power. “The teachers may be the tip of the spear here,” he declares in his heavy Brooklyn accent.

In many ways, the strikes illustrate Sanders’ theory of political change. He has long insisted that the key to moving the country in a more progressive direction is to make ambitious demands and build movements capable of achieving them. Striking teachers in states from West Virginia to Arizona bucked the traditional tried-and-failed mechanisms for obtaining better pay and working conditions, and joined together by the tens of thousands to act. By withholding their labor, they won key demands.

At a time of staggering income inequality and stagnant wages, with unions facing an all-out assault from the Right, the teachers’ strikes have served as a rare bright spot for labor, proving that workers can still take on conservative politicians and their corporate backers. Now, with the Supreme Court’s Janus decision poised to bruise public-sector unions, Sanders is attempting to help revive the U.S. labor movement.

Over the spring, Sanders trekked across the country to stand with low-wage workers at corporations such as Disney and Amazon, spotlighting their efforts to win better treatment on the job. In May, he introduced the Workplace Democracy Act, a sweeping bill that would prevent employers from using certain anti-union tactics, make it easier for workers to unionize, and undo so-called right-to-work laws that drain unions of resources. The bill has secured support from almost a third of Senate Democrats, including prospective 2020 presidential contenders Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris and Cory Booker.

In a sprawling interview with In These Times, Sanders discusses how unions can respond to Janus, the fight to move the Democratic Party left, the recent victories of democratic socialist candidates and why he believes the 2018 midterms are the most important of his lifetime.

Why do you see labor issues as a critical rallying point in 2018?

In my view, there is really no way the middle class in this country is going to grow unless we build the trade union movement. Virtually all of the power rests with employers and large corporations. Workers without unions are finding it very difficult to get the kind of wages and benefits that they need.

The statistics are very clear that workers in union companies are earning better wages and have far better benefits than nonunion workers. And the working people in this country know it. In overwhelming numbers, workers want to join unions.

But it is increasingly difficult for them to do so. That is because of the power of employers to intimidate workers, to threaten to move their companies away, and to fire workers who are trying to organize. So it is very, very difficult now for workers to have a union. That has got to change.

You named your bill the Workplace Democracy Act. Why do you think it’s important for workers to be able to practice more democracy on the job?

It’s an issue that we don’t talk about as a nation very much. Millions and millions of people are waking up in the morning and saying, “Oh God, I have to go to work and I hate my job. I feel exploited. I feel powerless. I feel like a cog in a machine.” If we believe in democracy, it’s not just voting every four years, or every two years—it’s about empowering your whole life and having more say in what you do all day.

Workers who are in a union have the ability to have their voices heard and to express their discontent in terms of working conditions. So unions empower ordinary people to have a little bit more control over their lives.

Less than 11 percent of Americans currently belong to unions, and since taking office, the Trump administration has been waging an all-out assault on workers' rights. Yet in recent months, teachers have gone on strike across the country. Polling shows that younger people have a more favorable opinion of unions than older Americans. Are you optimistic about the future of the labor movement?

Yes, I am. With these teachers’ strikes—especially those taking place in so-called conservative states like West Virginia, Kentucky and Oklahoma—teachers have basically said, “Enough is enough.” We have to make sure that our kids get the educations that they need, that we attract good people into the teaching profession. Teachers almost spontaneously stood up and fought back and took on very right-wing legislatures. This was, I think, a very significant step forward.

The teachers may be the tip of the spear here, because you’ve got millions of people watching and saying, “Wait a minute, I work two or three jobs to make a living, 60 hours a week, and can’t afford to send my kids to college. Meanwhile, my employer is making 300 times what I make and he gets a huge tax break.”

I see an anger and a resentment among working families. They want an economy that rewards the work of ordinary people and doesn’t just allow the billionaires to get even richer. That’s what the teachers’ strikes are all about.

In terms of younger people, they’re looking at a nation where technology is exploding, where workers’ productivity has risen, and yet the average young person today has a lower standard of living than his or her parents. Younger people are saying, “What is going on? This is the wealthiest country in the history of the world—why am I still living at home? Why am I struggling to pay off my student debt 10 years after I graduated college? Why can’t I afford healthcare?” I think young people are smart enough to look around and say maybe we need unions to get the kinds of wages and benefits that working people are entitled to.

The Supreme Court’s Janus decision will spread right to work to the public sector nationwide. How can workers respond?

The Workplace Democracy Act would make it illegal for states to pass right-to-work legislation. The people of this country have a right to organize, they have a right to form trade unions, and it is not acceptable that states are denying them that right.

The Janus case is a very significant setback for the union movement. The Right is already trying to mobilize public employees to leave their unions. What we have to do is an enormous amount of organizing and educating to explain to workers: “You think you’re going to save a few bucks by not paying union dues, but in the long run you’re going to be a lot worse off when you don’t have a union negotiating a decent contract for you. If you want the benefits of that contract, you’ve got to pay your fair share of dues.”

Why do you think it’s important to highlight the plight of workers at Disney and Amazon?

In terms of Amazon, the CEO, Jeff Bezos, is the wealthiest person in the world right now. His wealth has increased in the first four months of this year by about $275 million a day. You got that? A day. That sort of astronomical number is hard to believe.

Amazon is doing phenomenally well, and yet you have thousands of employees in Amazon warehouses who are paid wages so low that the average taxpayer in this country has got to subsidize Amazon by providing them food stamps, or Medicaid, or publicly subsidized affordable housing. The taxpayers of this country should not have to subsidize a guy whose wealth is increasing by $275 million every single day. That is obscene and that is absurd. This speaks to the power of the people at the top who use their power to become even richer at the expense of working families.

With Disney, you have a corporation that made $9 billion in profit last year—a very, very profitable company. CEO Bob Iger recently reached an agreement for a $423 million, four-year compensation package. And yet he’s paying the workers in Disneyland—the people in Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck costumes, the people who serve food, the people who collect the tickets and manage the rides—starvation wages. Eighty percent of the workers there make less than $15 an hour.

Living expenses are very high in Anaheim [where Disneyland is]. Many people cannot afford an apartment and are living in their cars. They don’t have enough money for food. So here you have a profitable corporation reaching an extraordinary compensation package for their CEO and paying starvation wages to their workers. These are the kind of issues that need to be highlighted.

Between 1978 and 2017, we've seen the union membership rate in the United States fall by more than half. Over this same period, the Democratic Party has taken a more corporate-oriented turn. In President Obama’s first term, Democrats were criticized for failing to pass the Employee Free Choice Act, which would have enshrined card check, a feature of your bill. Do you think the Democratic Party establishment has been asleep at the wheel on protecting labor rights?

If your question is whether, for too many years, the Democratic Party has been paying more attention to corporate interests than the needs of working people, then the answer is yes. Ultimately, the fight is over the future of the party. The Democratic Party has got to decide, to quote Woody Guthrie, “Which side are you on?” You cannot be on the side of Wall Street and large profitable corporations and very wealthy campaign contributors while you’re claiming to be the party of working people. Nobody believes that. You can’t do both. And right now, the Democratic Party has got to decide which side it is on, and I’m doing everything that I can to make it the party of working people.

We need a party that has the guts to stand up to the 1% and to represent working families. I think it’s the right thing to do, and from a public policy point of view, I think it will make this a much better country—to put policies in place that end our high level of poverty, to address the fact that we’re the only major country not to guarantee healthcare, that we’re not being as strong as we should on climate change; that we haven’t made public colleges and universities tuition-free. Those are all ideas that will improve life in the United States of America. They’re also great political ideas.

You have worn the mantle of democratic socialist throughout your political career. Today we’re seeing socialism increase in popularity among younger people, and democratic socialists are winning local primaries and elections in states such as New York, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Montana. What do you think this shift means?

Our opponents can say, “Oh, democratic socialist, it’s radical, it’s fringe-y, it’s crazy.” But when you go issue by issue and you ask the American people what they think, they say, “Yeah, that makes sense.” For example, should the United States join every other major country and guarantee healthcare for all by moving toward Medicare for All? Is that a radical idea? No. Because healthcare is a right, not a privilege. Young people say, “Yeah, of course. That should be a right, yeah. My grandma is on Medicare, she likes it. Why can’t I get it?” Not a radical idea.

Today, in many respects, a college degree is as valuable as a high school degree was 50 years ago. So, when we talk about public education, it should be about making public colleges and universities tuition-free. Is that a radical idea? I don’t think so.

At a time when you have three people, including Jeff Bezos, who own more wealth than the bottom 50 percent of the American people, is it a radical idea to say that we should significantly raise taxes on the very wealthy and large profitable corporations? Not a radical idea. Rebuilding our infrastructure, creating millions of jobs. Not a radical idea. Immigration reform. Criminal justice reform. The vast majority of the American people support both those ideas.

We are managing to get these ideas out there. The ideas are catching on. And to young people especially, they make sense.

You recently introduced a Medicare for All bill with a historic number of co-sponsors. Why do you think so many Democrats are now jumping on board with universal, single-payer healthcare?

The overwhelming majority of Democratic voters now support Medicare for All. So if I'm running for office and I see a poll that shows that 70 or 80 percent of people say that we should have Medicare for All, I don't have to be the bravest guy in the room to say I think I'm going to make that part of my program.

And by the way, you've got many Republicans today who benefit from Medicare, and their sons and daughters are saying, “My dad has Medicare; I'd like it as well.” So you have the majority of Americans and the overwhelming majority of Democrats now supporting it, so for many candidates it simply becomes common sense and good politics.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#in these times#bernie sanders#progressive#progressive movement#democratic socialism

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuomo won't release state workforce telecommuting data

1of6Agency Building Four at Empire State Plaza is lightly used during the coronavirus lockdown on Thursday, May, 14, 2020, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union)Will Waldron/Albany Times Union

2of6Agency Building Four at Empire State Plaza is lightly used during the coronavirus lockdown on Thursday, May, 14, 2020, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union)Will Waldron/Albany Times Union

3of6View of the secured parking area entrance at the Capitol on Thursday, May, 14, 2020, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union)Will Waldron/Albany Times Union

4of6PEF and CSEA hold a protest against the Governor's furlough plan outside the Capitol in Albany, NY on May 10, 2010. (Lori Van Buren / Times Union)LORI VAN BUREN

5of6CSEA President Danny Donohue,left joined by his chief negotiator Ross Hanna, right, announced a tentative contract agreement with Governor Andrew Cuomo at the headquarters of CSEA in Albany, N.Y. which allows for furloughs in 2011 and 2012 and increased health care contributions by the 66,000 members of the union in order to to get "an agreement that balances shared sacrifice with fairness and respect" according to Donohue. (Skip Dickstein / Times Union)SKIP DICKSTEIN

6of6Public employees have a new early retirement option to consider after the Legislature approved a 55/25 option for state and local workers. (John Carl D'Annibale / Times Union)John Carl D'Annibale

ALBANY — Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo's office has blocked its administration from releasing data on the number of state workers who are doing their jobs at home during the coronavirus pandemic, according to a person briefed on the matter but not authorized to comment publicly.

The decision to withhold the information comes as Cuomo's administration has not said whether it has developed detailed plans for "non-essential" state workers to return to their offices. The administration, facing a $10 billion deficit, also has not revealed its plan for what it predicts will be a necessary 10 percent reduction in "state agency operations," including whether that plan would require layoffs, furloughs or pay freezes.

But multiple state employees said supervisors have told them recently that working staggered shifts is being discussed in anticipation of the reopening of some state offices, potentially in June. That would also entail workers altering the days they work in the office or stay home and telecommute, to limit the number of people who are working in close quarters, sharing elevators or walking in hallways.

Wayne Spence, president of the Public Employees Federation, the state's second-largest public labor union, said he has not been provided estimates on the number of workers who are telecommuting. But Spence said that he has received anecdotal reports that telecommuting is working effectively at many agencies and, in some instances, employees are more productive than they were when commuting and working in offices.

"A lot of these managers who were fearful are actually seeing an increase in production," Spence said. "People are working more hours."

Although there have been some glitches, the wider use of telecommuting, which is becoming more common in the private sector, may be a way to prevent reductions in the state workforce, Spence said.

"We’ve suggested that telecommuting is an opportunity to get the state out of spending a lot of money on real estate and reinvest that money in the state workforce," Spence said. "We believe telecommuting actually worked out way better than a lot of managers had predicted. We also believe that telecommuting allows single parents and millennials to enter the workforce.

Cuomo has commented frequently on what is necessary to reopen private businesses, many of which were shut down in March by a series of executive orders he issued as the pandemic struck New York.

"We understand what has to be done, how the workforce has to have personal protection. They have to be socially distant," Cuomo said earlier this month. "The workspace itself in some cases has to be adjusted, reconfigured. How do you have people work but they are six feet apart? ... There's no gathering. That's what we're trying to avoid, and then what processes do we have in place to test those employees or if the employee is symptomatic you can get them testing right away."

Questions about those concerns were challenged following the state Department of Labor's recent decision to deem employees of its Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board as "essential" as they were ordered to return to their offices earlier this month.

The union for those workers filed a complaint with the Department of Labor last week, noting that many of the employees report to a Brooklyn office that requires them to use public transportation.

"No accommodations have been made for staggered scheduling — which would help staff avoid crowds during their commutes," the complaint states. "Although DOL has indicated that masks and hand sanitizer will be provided to UIAB staff, there is no training on the correct use of masks. DOL also indicated that high touch areas around UIAB offices will be cleaned more frequently ... (but there was) no information about who will do the cleaning, and with what products."

For those state offices and agencies that will continue with telecommuting, it has not been without its problems.

At the Department of Taxation and Finance, where some employees have worked remotely for years, other employees have been connected from their computers at home to the state's secure computer servers in only the past two weeks, despite being out of their offices for more than two months, according to interviews with employees. That agency has also used online teleconferencing services to conduct audits and hold meetings, but its level of audits has decreased significantly.

At the Office of Medicaid Inspector General, an employee told the Times Union this week that it took weeks for the state to set up the employee's laptop computer with the virtual private network needed to connect to the state's servers. The use of VPNs has also unnerved many state employees, who have been cautioned by union leaders that the agencies can monitor their online activity when they are connected to the state's servers.

On top of the inability of many workers to be able to do their jobs effectively from home, the stay-at-home telecommuting orders have also taken an emotional toll.

"We’re seeing a lot more mental health issues, anger, depression," Spence said of his union's members. "We’re saying to the state we need more EAP (employee assistance program)-type services available because of some of things we’re starting to see. But for a majority of the members, most of our members like it."

Still, the union is bracing for workforce reductions and adjusting its own budget accordingly.

"Something is coming so I have to be prepared for that," Spence said. "We have to be realistic and know that with the budget shortfall that’s out there, something is going to happen to the state workforce."

On April 30, Cuomo had suggested members of the state's workforce, who had experienced reduced job duties as a result of their offices being closed, could be used as "contact tracers" who would be tasked with finding and alerting people who may have had contact with a person infected with COVID-19.

"You also have a lot of government employees who are at home now getting paid, but are not working," he said during his daily briefing that day.

It's unclear why Cuomo's office blocked the release of the information regarding the number of telecommuting employees. The agencies, offices and departments that the Times Union asked for the information on May 14 included the Governor's Office of Employee Relations, Department of Civil Service, Department of Health, Office of Medicaid Inspector General, Department of Transportation, Division of Criminal Justice Services, Thruway Authority, Department of Motor Vehicles, State Police, Department of Public Service, Gaming Commission and Office of General Services.

Those branches of state government all are controlled by the governor's office and their public information officers are routinely required to forward information on press inquiries to Cuomo's staff before responding. After the Times Union requested the telecommuting figures, and was assured by several of the public information officers that they could provide that information, most stopped responding to follow-up telephone calls and emails.

But other state offices — outside the governor's direct control — promptly released the information that week. The state Education Department said 2,174 of its 2,670 employees are working remotely, with just 229 reporting to an office regularly. The attorney general's office said that roughly 95 percent of its 1,950 employees are telecommuting.

Telecommuting has not been as frequent among the tens of thousands of Civil Service Employees Association workers.

"The overwhelming majority of our state workforce were considered essential and have been working since the beginning of this crisis," said Mark M. Kotzin, a spokesman for CSEA. "That said, we’re still having active conversations with (the administration) all the time about people who have been continuing to work all along. ... Personal protective equipment is part of that. We’ve largely worked out any problems in the supply chain for PPE for our members in the state."

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Text

Education

Los Angeles Braces for Major Teachers’ Strike

LOS ANGELES — There are 900 schools, 30,000 teachers and more than 600,000 students in the Los Angeles public school system. By the end of the week, a teacher strike could throw them all into crisis.

After months of failed negotiations, teachers are expected to walk off the job on Thursday, in a show of frustration over what they say are untenable conditions in the second-largest school system in the country.

Teachers and other employees in the Los Angeles Unified School District are demanding higher pay, smaller class sizes and more support staff like counselors and librarians. But district officials say that they do not have the money to meet all of the demands and that the strike would do more damage to schools than good.

A strike in Los Angeles would offer a new stage for the national teacher protest movement, which in the last year has driven walkouts against stagnant pay and low education funding in six states. A walkout in staunchly liberal Los Angeles would also signal a major shift in a movement that has spread mostly in conservative or swing states with weaker unions.

Teachers in those states thronged state capitals to picket legislators and governors last year. Educators in Los Angeles, by contrast, are led by a strong union and are planning a more conventional strike against the superintendent and Board of Education, who they say favor charter schools over traditional ones. Their protests could ripple across the state, with frustrated teachers in other cities considering their own labor actions.

Although officials from the teachers’ union and the school district have another negotiating meeting set for Monday, analysts say a last-minute agreement seems unlikely.

The impending strike highlights the fact that despite California’s reputation as a center of liberal policy, it spends relatively little on public education. School spending levels, about $11,000 per student in 2016, are far below those in other blue bastions; for example, California spends about half as much as New York on the average child.

Education advocates on all sides of the labor impasse in Los Angeles say that it is the neediest students who are hurt most by funding constraints. More than a fifth of public school students in California are still learning English, the highest percentage in the country.

“California has been underfunding its schools for many, many years,” said Pedro Noguera, a professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has worked closely with Los Angeles and New York public schools.

The state has only recently begun to restore deep cuts made during the last recession, when California was hit particularly hard. “It’s not even close to where we should be,” Professor Noguera said. “I would not say that the state has deliberately starved the schools, but there has been no leadership from the state.”

Underlying the debate between the two sides is a situation they agree is a major problem: that high-needs school districts like Los Angeles, where 82 percent of students are low-income, bear the brunt of the burden from the state’s low education spending.

With many wealthy and white families opting to choose charter or private schools, or move to other surrounding school districts, the Los Angeles school district is disproportionately African-American and Latino. A study from U.C.L.A.’s Civil Rights Project found that Latino students in Los Angeles are more segregated than anywhere else in the country.

In other districts in California — Oakland, in particular — as well as in Virginia and Indiana, teachers angry over pay and limited resources have raised the possibility of protests.

“We’ve had a systemic process over the past many years of disinvesting in neighborhood public schools,” said Alex Caputo-Pearl, the president of United Teachers Los Angeles, the main union for the district. Instead of funding neighborhood schools, cities and states had chosen to “dismantle them and privatize them,” he said.

Critics of the Los Angeles union say that by targeting the school district and not the state, the union is misdirecting its ire.

“Ninety percent of our funding comes from Sacramento, and if they were marching there, I would be marching with teachers,” said Nick Melvoin, vice president of the Los Angeles Board of Education.

Mr. Melvoin is a major supporter of the city’s charter schools, but concedes that some of the union’s complaints are valid. When traditional schools lose students to charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately run, they are sometimes left with students who have more demanding needs. Some may be homeless or live in foster care, or have parents who are less involved in their educations.

“I think that’s fair,” he said of the critique. The solution for traditional schools, he argued, was not to vilify the charter sector, but to adopt some of the strategies of charters to compete with them. Policymakers should better regulate charter schools to make sure they do not “cherry pick” the easiest-to-teach students, he added.

The vast majority of charter-school teachers are not unionized (although hundreds of them in Chicago last month staged the nation’s first strike against a charter network). All charter schools in Los Angeles are expected to stay open during the strike.

Just before school began last fall, public schoolteachers in Los Angeles voted overwhelmingly in favor of a strike. For months public officials hoped for an agreement, especially after the district offered a 6 percent raise. Teachers in the statewide walkouts last year were largely successful in securing raises, though results were mixed on demands for more school funding and resources.

The Los Angeles union has insisted that it wants more than a raise. Some classes have as many as 45 students, the union complained, and school nurses, art and music teachers must serve thousands of students by traveling to multiple schools.

The union has accused the district of withholding nearly $2 billion in reserve money, but the district has repeatedly said that it is operating at a deficit. Austin Beutner, the district superintendent, says that meeting the union’s demands would immediately bankrupt the district and that the district is already in danger of insolvency.

“We all say we want what’s better for students,” Mr. Beutner said. “We all want lower class sizes and more nurses. There’s no issue between what they want and what we want.”

The union has fought bitterly with Mr. Beutner, a former investment banker who was selected to lead the district last year. “We need to be working ourselves out of a hole,” he added. “I have yet to understand how a strike is going to get us there.”

Because the state allocates money to schools based on daily attendance, the strike could cost the district millions of dollars in lost funding if students stay home while teachers are on strike. The last teacher strike in Los Angeles was in 1989, when schools closed for nine days. At the time, some teachers crossed the picket lines, but there is little sign that any will do so this time. Unlike other states, public employee strikes are legal in California, where unions hold considerable sway.

Many observers say the state’s property tax law is the major culprit for chronic funding shortages in large urban school districts. In 1978, California voters passed Proposition 13, which capped property taxes and drastically limited what the state could bring in for public schools. The law means that smaller affluent suburban communities can raise money for their schools with local bonds or parcel taxes much more easily than poorer urban districts, including Los Angeles.

Both union and district leaders in Los Angeles support an effort to place a measure on the 2020 ballot that would amend the law to allow increased taxes on commercial, but not residential, property.

Many education advocates are placing their hope in Gavin Newsom, the former mayor of San Francisco who will be inaugurated as California’s governor on Monday. But Mr. Newsom has made it clear that he already plans to spend billions in early childhood education and community college, so it is unclear how much new funding he will allocate to K-12 schools.

In the meantime, teachers like Amy Owen are preparing to greet students on Monday after three weeks of winter vacation and then strike three days later. Ms. Owen, who has been teaching in Los Angeles public schools for more than a decade, said it has grown increasingly difficult to live near her school in central Los Angeles on her salary of about $72,000.

“Pretty much everyone at my age owns things, a home or a condo or something, and for me to get that I’d have to commute an hour and a half every day,” said Ms. Owen, 44. “If you looked at my salary just as a number I would be doing well in many places. But in L.A. I am just barely middle class. I understand that teaching is not a profession where you are going to make a lot of money, but we deserve some basic respect.” *Reposted article from the New York Times by Jennifer Medina and Dana Goldstein of January 7, 2019

0 notes

Text

Why the NBA Wildcat Strike Is So Important

In protest of the Kenosha, Wisconsin police shooting of Jacob Blake, the Milwaukee Bucks refused to play their playoff game against the Orlando Magic—who also did not play and refused the Bucks’ forfeit—on Wednesday night and instead stayed in the locker room to speak with Wisconsin’s Attorney General and Lieutenant Governor.

"Despite the overwhelming plea for change, there has been no action, so our focus today cannot be on basketball,” the Bucks said in a statement. “We are calling for justice for Jacob Blake, and demand the officers be held accountable. For this to occur, it is imperative for the Wisconsin State Legislature to reconvene after months of inaction and take up meaningful measures to address issues of police accountability, brutality, and criminal justice reform.”

Within hours of the Bucks’ work stoppage, other teams in the NBA playoffs launched their own and were joined by sport leagues across the country. Every other playoff team scheduled to play that night refused, and teams in the WNBA, MLB, and MLS walked off the field during their games.

Many have called these work stoppages a boycott, but they're actually strikes. In fact, what these teams are doing right now is called a wildcat strike—a work stoppage without union approval, in this case the National Basketball Players Association. Confusing the two diminishes the fact that the players are risking their incomes and careers, because they are bound by “no-strike” clauses in their collective bargaining agreement. Across the country, workers in numerous industries are similarly barred from expressing their discontent.

A boycott is when an individual or group protests by withholding money and refusing to consume some company’s product or service. The #StopHateForProfit campaign, organized by activists protesting how Facebook handles hate speech and misinformation, was a boycott—advertisers refused to pay Facebook to place their advertisements. A strike is when an individual or group protests by withholding their labor and refusing to work—these athletes are refusing to work and withholding their labor, not their money.

What makes the NBA strike a “wildcat” strike is the fact that the NBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (the contract between the NBA and the players' union that dictates the "terms and conditions of employment") explicitly prohibits strikes. Section 30.1 is titled "No Strike" and reads:

"During the term of this Agreement, neither the Players Association nor its members shall engage in any strikes, cessations or stoppages of work, or any other similar interference with the operations of the NBA or any of its Teams."

The CBA, originally signed in 2017 and scheduled to last in 2023, is currently being renegotiated in response to the coronavirus pandemic and the effects it will have on working conditions and league revenue projections.

In the United States, no-strike clauses are common in collective bargaining agreements. They allow employers to take away workers’ key threat: withholding their labor. Under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, strikes are protected to an extent, but highly regulated. A strike may not be in support of an "unfair" labor practice, in violation of a no-strike clause, in the form of a sit-down strike, and so on. In 2019, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that wildcat strikes are not protected if striking employees become aware their union "disapproved of and disavowed the strike." To violate these rules is to open up oneself to being punished by your union, or the strike being found unlawful and its participants legally fired, or striking workers being indefinitely replaced.

U.S. labor law is born out of a violent history. Charles Lindholm, an anthropology professor at Boston University, found that “the United States had more deaths at the end of the nineteenth century through labor violence‚in absolute terms and in proportion to population size—than any other country except Tsarist Russia.” Labor violence here refers to violence against workers carried out either by private security forces funded by Gilded Age robber barons or by public security forces funded by the government.

Today, labor law is less violent and constructed to prevent general strikes and labor unrest with more finesse. This doesn’t necessarily empower workers, but leads to more docile relations. Often, this means the process of reaching a collective bargaining process can end up “routinizing and bureaucratizing conflict” as UC Santa Barbara history professor Nelson Lichtenstein told Motherboard. Strikes are defused by a long series of negotiations, fake outs, and attempts at stalling by the employer and its lawyers that stretches out weeks, months, or years.

This means that strikes—if they happen at all—almost always happen during pre-set periods of negotiation. For example, there is widespread labor unrest in Major League Baseball, but there is little chance of a strike until the current collective bargaining agreement between the Major League Baseball Players Association and the league expires on December 1, 2021. Many analysts believe that there will be a strike after it expires, because the league and the players are at odds on many issues. The same isn’t true of Europe, where the right to strike is generally much stronger across the continent than in any part of the United States.

And so the fact that the NBA strike happened suddenly, and in violation of its current CBA, is notable, laudable, and particularly risky.

Boycotts are for consumers. Strikes are for workers. And while no-strike clauses shouldn’t exist, they do for many workers across this country. A piece of paper shouldn’t stand in between people and a better contract, fair working conditions, or a better world. The choice to risk one’s job and career—especially one that pays as well as an NBA player—is a serious one that warrants a clear understanding so that we can better make that decision ourselves and support those who decide to strike, even if we don’t.

And even though anonymous and unconfirmed reports are emerging that players have “voted” to continue playing, no games have been played. Even if the NBA resumes in some fashion, the story isn’t over: the toxic labor relations at play will still be there, and so will the inhuman police violence that sparked the players’ labor action.

Why the NBA Wildcat Strike Is So Important syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

Working, and paying taxes, on holidays

Happy Labor Day. While many Americans are working on this holiday, others are fortunate to have off this first Monday in September.

Whether you're working or not most likely depends on the type of employee you are.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not require employers to pay employees for time not worked, such as vacations or holidays, writes Susan Heathfield for The Balance.

Different jobs, different days off: Salaried employees in exempt professional, technical or managerial positions expect paid holidays. Nonexempt, or hourly, employees are less likely to have paid holidays, or they receive fewer such days off than their salaried counterparts.

In some cases, workers who clock in while others are sleeping in get holiday pay.

However, absent a collective bargaining agreement, whether or how much holiday pay you get is totally up to your boss. There are no federal or state laws that require companies to compensate you more for holiday work than your normal hourly rate.

If you do get extra pay this Labor Day, good for you … and the U.S. Treasury. Today's earnings will be reflected in your income and payroll tax withholdings.

If like me you're a contractor working on holidays, things don't change. We still must meet our deadlines for the amount negotiated with our clients.

And, oh yeah, keep track of our earnings so we can make the appropriate estimated tax payments. Remember, we have one of those, the third of the tax year, coming due on Sept. 15

Enjoy employment-themed movies: As for all y'all with Labor Day time to kill, consider checking out a work-related movie.

Here are 10 of my employment-themed film favorites.

In the classic silent movie "Modern Times," Charlie Chaplin's Little Tramp struggles to survive in the modern, industrialized world. The 1936 comedy, written and directed by Chaplin, is a comment on the desperate employment and financial conditions many people faced during the Great Depression. Trust me, despite the harsh setting and topic, Chaplin entertains.

Charlie Chaplin as the Little Tramp on a new job in "Modern Times." (Photo via Wikipedia)

More modern workplace issues are the subject of Mike Judge's contemporary comedy "Office Space." Live vicariously through the three company workers who hate their jobs and decide to rebel against their greedy boss. Plus, Milton Waddams' red stapler!

Who hasn't felt like they knew exactly what needed to be done to get the job done right? That's why we cheer for the movie version of real-life environmental health activist "Erin Brockovich." Julia Roberts portrayal of the insistent, committed single mom who becomes a legal assistant and almost single-handedly brings down a polluting power company earned her an Oscar. Albert Finney, who played her boss, deserved one, too.

Want more environmental activism? Rent or stream the late Mike Nichols' "Silkwood." Meryl Streep is the title character, a plutonium processing plant worker who, according to legend and the movie, literally gave her life to expose the facility's worker safety violations. Streep and costar Cher received Academy Award nominations for their performances, Nichols for his direction.

I'm on a heroic worker roll with "Norma Rae," the 1979 biopic about efforts to organized union workers in the South. Sally Field as the film's lead won her first Oscar for her performance.

OK, let's get back to lighter film fare with a double feature of employees getting the better of their horrible bosses. Yep, I'm talking about "9 to 5" "Working Girl."

In "9 to 5," released in 1980, and pre "Grace and Frankie" Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, along with movie theme-song writer/singer Dolly Parton, take down their sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical, bigoted boss, played with relish by Dabney Coleman.

Eight years later we got "Working Girl" Melanie Griffith's big hair and bigger aspirations, with secretary Griffith stealing back her idea that evil boss Sigourney Weaver appropriated while simultaneously finding love with Harrison Ford.

Hey, guys, I haven't forgotten y'all. "Trading Places" gives us Eddie Murphy as a street-smart con artist and Dan Aykroyd as a snobbish commodities broker who initially unknowingly switch places as part of a nature vs. nurture bet. But the duo wins in the end, besting the two brothers — played by Don Ameche and Ralph Bellamy — who used Murphy's and Aykroyd's stations in life as an experiment, giving the comedy some social commentary bite.

Yes, I'm a George Clooney fan, so his 2009 movie "Up in the Air" makes my workplace flix list. Clooney's character specializes in firing people, a job he actually enjoys. But as the story progresses, his mind and job choice changes.

Finally, the Labor Day movies round-up closes with a movie about a worker who rarely, if ever, gets a paid holiday. "Waitress" stars Kerry Russell as Jenna, a pregnant, unhappily married waitress who falls into an unlikely relationship as a last attempt at happiness. Bonus: there are lots and lots of pies.

I know I was a bit late in getting this post up, so you probably won't be able to get all 10 of these movies in this afternoon. But check them out in the coming weekends. You'll be glad you did.

You also might find these items of interest:

5 moves — and 7 tax tips! — to make if you're fired

Job search expenses could help reduce your tax bill

Labor Day tax tip: Union dues might be tax deductible

Advertisement

// <![CDATA[ // <![CDATA[ // &lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); // ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;gt; // ]]&gt; // ]]> // ]]>

0 notes

Text

Working, and paying taxes, on holidays

Happy Labor Day. While many Americans are working on this holiday, others are fortunate to have off this first Monday in September.

Whether you're working or not most likely depends on the type of employee you are.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not require employers to pay employees for time not worked, such as vacations or holidays, writes Susan Heathfield for The Balance.

Different jobs, different days off: Salaried employees in exempt professional, technical or managerial positions expect paid holidays. Nonexempt, or hourly, employees are less likely to have paid holidays, or they receive fewer such days off than their salaried counterparts.

In some cases, workers who clock in while others are sleeping in get holiday pay.

However, absent a collective bargaining agreement, whether or how much holiday pay you get is totally up to your boss. There are no federal or state laws that require companies to compensate you more for holiday work than your normal hourly rate.

If you do get extra pay this Labor Day, good for you … and the U.S. Treasury. Today's earnings will be reflected in your income and payroll tax withholdings.

If like me you're a contractor working on holidays, things don't change. We still must meet our deadlines for the amount negotiated with our clients.

And, oh yeah, keep track of our earnings so we can make the appropriate estimated tax payments. Remember, we have one of those, the third of the tax year, coming due on Sept. 15

Enjoy employment-themed movies: As for all y'all with Labor Day time to kill, consider checking out a work-related movie.

Here are 10 of my employment-themed film favorites.

In the classic silent movie "Modern Times," Charlie Chaplin's Little Tramp struggles to survive in the modern, industrialized world. The 1936 comedy, written and directed by Chaplin, is a comment on the desperate employment and financial conditions many people faced during the Great Depression. Trust me, despite the harsh setting and topic, Chaplin entertains.

Charlie Chaplin as the Little Tramp on a new job in "Modern Times." (Photo via Wikipedia)

More modern workplace issues are the subject of Mike Judge's contemporary comedy "Office Space." Live vicariously through the three company workers who hate their jobs and decide to rebel against their greedy boss. Plus, Milton Waddams' red stapler!

Who hasn't felt like they knew exactly what needed to be done to get the job done right? That's why we cheer for the movie version of real-life environmental health activist "Erin Brockovich." Julia Roberts portrayal of the insistent, committed single mom who becomes a legal assistant and almost single-handedly brings down a polluting power company earned her an Oscar. Albert Finney, who played her boss, deserved one, too.

Want more environmental activism? Rent or stream the late Mike Nichols' "Silkwood." Meryl Streep is the title character, a plutonium processing plant worker who, according to legend and the movie, literally gave her life to expose the facility's worker safety violations. Streep and costar Cher received Academy Award nominations for their performances, Nichols for his direction.

I'm on a heroic worker roll with "Norma Rae," the 1979 biopic about efforts to organized union workers in the South. Sally Field as the film's lead won her first Oscar for her performance.

OK, let's get back to lighter film fare with a double feature of employees getting the better of their horrible bosses. Yep, I'm talking about "9 to 5" "Working Girl."

In "9 to 5," released in 1980, and pre "Grace and Frankie" Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, along with movie theme-song writer/singer Dolly Parton, take down their sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical, bigoted boss, played with relish by Dabney Coleman.

Eight years later we got "Working Girl" Melanie Griffith's big hair and bigger aspirations, with secretary Griffith stealing back her idea that evil boss Sigourney Weaver appropriated while simultaneously finding love with Harrison Ford.

Hey, guys, I haven't forgotten y'all. "Trading Places" gives us Eddie Murphy as a street-smart con artist and Dan Aykroyd as a snobbish commodities broker who initially unknowingly switch places as part of a nature vs. nurture bet. But the duo wins in the end, besting the two brothers — played by Don Ameche and Ralph Bellamy — who used Murphy's and Aykroyd's stations in life as an experiment, giving the comedy some social commentary bite.

Yes, I'm a George Clooney fan, so his 2009 movie "Up in the Air" makes my workplace flix list. Clooney's character specializes in firing people, a job he actually enjoys. But as the story progresses, his mind and job choice changes.

Finally, the Labor Day movies round-up closes with a movie about a worker who rarely, if ever, gets a paid holiday. "Waitress" stars Kerry Russell as Jenna, a pregnant, unhappily married waitress who falls into an unlikely relationship as a last attempt at happiness. Bonus: there are lots and lots of pies.

I know I was a bit late in getting this post up, so you probably won't be able to get all 10 of these movies in this afternoon. But check them out in the coming weekends. You'll be glad you did.

You also might find these items of interest:

5 moves — and 7 tax tips! — to make if you're fired

Job search expenses could help reduce your tax bill

Labor Day tax tip: Union dues might be tax deductible

Advertisement

// <![CDATA[ // <![CDATA[ // &lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ // &amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); // ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;amp;gt; // ]]&amp;gt; // ]]&gt; // ]]> // ]]>

from Tax News By Christopher http://www.dontmesswithtaxes.com/2017/09/labor-day-holidays-work-taxes.html

0 notes

Text

The NFL's Growing Class Divide Could Undermine a Potential Player Strike

Richard Sherman is right. There's only one way for NFL players to get guaranteed contracts—or really, any other concessions—from league owners. And it doesn't involve asking nicely.

"If we want as the NFL, as a union, to get anything done, players have to be willing to strike," the Seattle Seahawks cornerback told ESPN on Wednesday. "That's the thing that guys need to 100 percent realize.

"You're going to have to miss games, you're going to have to lose some money if you're willing to make the point, because that's how MLB and NBA got it done. They missed games, they struck, they flexed every bit of power they had, and it was awesome. It worked out for them."

If this sounds like Bargaining 101 for Dummies—use the leverage you have to force the outcome you want, duh—well, that's how power works. Heading into its next round of collective bargaining, the NFL Players Association will be exactly as strong—or as weak—as the ability of its members to stand together, withhold their labor, shut the sport down, and take one on the financial chin so that owners, advertisers, and broadcasters take one, too.

Given what happened the last time the union struck a deal with the league, Sherman and his peers may be severely hamstrung. They've been put in a position where the haves and the have nots might not find common ground.

Look, walking out on work is hard. Especially for football players. They play a brutal sport, and typically have a short window of time to earn what they can before their brains and bodies break. Forming a picket line means giving up money they'll never get back, all so somebody else can make more in the future. It's not particularly surprising that the NFLPA historically has been lousy at it.

That said, the league's current Collective Bargaining Agreement likely makes a potential future strike even tougher. How so? Start with the bottom line. Under the previous agreement negotiated by former union head Gene Upshaw in 2006, players received 59 percent of annual NFL revenues minus a roughly $1 billion set-aside that went directly into owners' pockets; under the current deal negotiated by NLFPA executive director DeMaurice Smith in 2011, players receive 47 percent, minus a similar set-aside.

In other words: players took an 12 percent haircut that former player Sean Gilbert estimated would cost players $10 billion over the 10-year life of the agreement. Former NFLPA executive committee member Sean Morey told VICE Sports that amount could be closer to $15 billion. Whatever the final number ends up being, every dollar clawed back gives owners more resources to ride out a possible work stoppage when the current CBA expires in 2020—and more importantly, saps the union's ability to fill a war chest of its own, something players will need if they're foregoing paychecks.

But that's not the most union-busty thing about it.

It's one thing to end up with a smaller slice of the money pie; sometimes that happens. It's quite another to agree to divvy up that slice in a way that weakens—albeit inadvertently—your own position. And that's what the CBA seems to do, primarily by fostering what former Tampa Bay Buccaneers general manager Mark Dominik told Kevin Clark of The Ringer is "a have-and-have-not league" in which a small number of star veterans earn big bucks while the rest of the labor pool becomes increasingly younger, cheaper, and more disposable.

When the unintended consequences of the CBA may be making your job harder. Photo by Mark J. Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports

Modern NFL rosters look a lot like the shifting American economy. The rich get richer. Almost everyone else fights for scraps. Consider the New England Patriots: according to the NFL salary database at spotrac.com, the defending champions have three players making more than $10 million a year, six making more than $5 million, and 53 making less than $1 million (the latter number of players will drop following training camp and preseason roster cuts). Similarly, the Super Bowl runner-up Atlanta Falcons have three players making more than $10 million, six making more than $5 million, and 61 making less than $1 million.

Why the divide? According to Clark, franchises have become increasingly adept at structuring player contracts in ways that are "eradicating the NFL's middle class and costing its lower tier much of its leverage"—mostly through language that reduces pay if players get hurt and/or fail to make their teams' 46-man gameday rosters. Former NFL player-turned-injury insurance salesman Nick Grisen told Clark that those two tricks cost players at least $48 million in 2015 and 2016.

However, the primary culprit is how the CBA treats rookies. Before 2011, incoming players were free to bargain with the teams that drafted them; today, they're subject to a wage scale, three-year renegotiation waiting periods, and team contract options that all conspire to suppress salaries. The last top draft pick under the old agreement, quarterback Sam Bradford, signed a contract worth a guaranteed $50 million; by contrast, the first top pick under the current deal, quarterback Cam Newton, received only $22 million guaranteed.

When the NFLPA agreed to limit rookie pay, the idea was that salary savings would end up in the pockets of experienced players. That's exactly what has happened—for a fortunate few. Otherwise, teams have been incentivized to avoid pricey and (presumably) injury-prone veterans, the better to load up on healthy, hungry, cost-controlled youngsters. As Ben Volin of the Boston Globe explains:

... why would a team pay big money to a free agent when it can simply draft a cheaper, healthier alternative and have him locked in to a near-minimum salary for at least three seasons?

While the CBA promises minimum salaries for veterans—$715,000 this year for players with 4-6 years of experience, $840,000 for 7-9, and $940,000 for 10-plus—many times it works against them.

"I've had teams tell me all the time, 'Your guy is a minimum-salary guy, he's too expensive,' " [an] agent said. "I have veteran players that would play for $50,000 if they could" ...

Last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that after remaining constant over a 17-year span, NFL career lengths were shrinking at an "unprecedented rate"—dropping by about two and a half years from 2008 to 2014. Clark reports that the number of NFL players age 31 or older has fallen 20 percent from a decade ago. Volin notes that in 2016, about half of the league's players were 25 or younger—which means most of them were still locked into their rookie contracts.

The overall result? A star system economy in which the NFL's on-field labor force is split into two castes:

1. A well-paid minority of recognizable veteran players, mostly quarterbacks, who through skill and injury luck have managed to become the league's equivalent of the petite bourgeoisie;

2. A poorly-paid majority of disposable, relatively anonymous short-timers who function as the league's proletariat, grinding and hoping to last long enough to make it into the upper class.

When only one of your is locked into a cost-controlled salary for the next half-decade. Photo by Bill Streicher-USA TODAY Sports

NFL income inequality isn't all bad. Nor is it totally avoidable. The league always will have superstars, as well as third-string special teams fodder.

Still, the unintended hollowing out of a healthy middle class may have severe consequences for union strength and solidarity. Imagine it's 2020. You're Smith or a player union leader, trying to rally your members for a strike—or maybe just imploring them not to cross a picket line, even though their mortgages are going unpaid and their bills are piling up.

How much motivation do star players have to fight tooth-and-nail against a league that's already taking pretty good care of them? Conversely, how many of your rookie scale players want to drag out a work stoppage in which every missed game check represents a significant chunk of all the money they'll ever be able to earn playing football?

For NFL owners, this is the sneaky genius of the current CBA—in fact, I'd be surprised if league negotiators back in 2011 didn't see probable player class stratification as a feature of the deal, not a bug. In 1999, NBA owners took advantage of infighting between star and rank-and-file union members to negotiate a CBA that limited the maximum amount of money any one player could make; in 2011, the league exploited the same divide to slash the players' share of overall NBA revenues by seven percent.

NFL owners aren't strangers to this tactic. When the league and union were battling over allowing free agency in the late 1980s and 1990s, the NFLPA used group licensing revenue to fund a series of antitrust lawsuits against the NFL. In response, a clever league marketing executive named Frank Vuono devised a plan to undercut the union's efforts: convince top quarterbacks to stop assigning their licensing rights to the NFLPA, and instead partner with the league in order to make more money for themselves.

Vuono called his concept "the Quarterback Club." He promised players between $20,000 and $100,000 of extra annual income, cash they wouldn't have to share with their fellow union members. Most of the game's biggest stars—John Elway, Dan Marino, Troy Aikman, and Phil Simms among them—bought in. (As Matthew Futterman notes in his book Players: The Star of Sports and Money, and the Visionaries Who Fought to Create a Revolution, Joe Montana never joined, but only because he wanted to be paid more than anyone else). The QB Club and the union's licensing arm, Players Inc., sparred on and off for the next decade, and it wasn't until the NFLPA bought the QB Club from the league in 2002 for a reported $4 million that the players were "made whole again."

The lesson? Divide and conquer works. Which brings us back to Sherman, and the upcoming CBA negotiations. Could players actually exercise maximum show-stopping leverage, either by striking or credibly threatening to do so? It's possible. They know they got walloped on the last deal; they're openly envious of the big-money guaranteed contracts being handed out in the NBA; they're increasingly tired of commissioner Roger Goodell and the league handing them Ls on everything from player discipline to marijuana use to brain trauma protection. On the other hand, it's difficult to maintain solidarity when your credit card is being declined, or when rocking the boat might cost you a yacht. A financial house divided cannot stand—and as NFL players spoil for a 2020 fight, they would do well to look a little less like Dowton Abbey.

The NFL's Growing Class Divide Could Undermine a Potential Player Strike published first on http://ift.tt/2pLTmlv

0 notes