#this song was made in 1947 and not much has changed in the... starts counting on my fingers

Note

1 & 2 for music asks!

1: A song you like with a color in the title

"Black-Red" by Dr. Dog

i love this one cuz i always love posing the chorus like a personal question. ohhh black.... or maybe red? 🤔 or black! or...maybe red.....

2: A song you like with a number in the title

"16 Tons" by Red Stick Ramblers

so this is a cover but its the first vers I heard of this song and i do rly like it. bonus: i think of mtmte megatron when i think of this lol

linky link to the post

#and brother am i feeling the lyrics of 16 tons.#you load 16 tons and what do you get?#another day older and deeper in debt#st peter dont you call me cuz i cant go#i sold my soul to the company store#this song was made in 1947 and not much has changed in the... starts counting on my fingers#what? 80 yrs since its conception?#captialism evil.#skeletal chatter#ask games

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

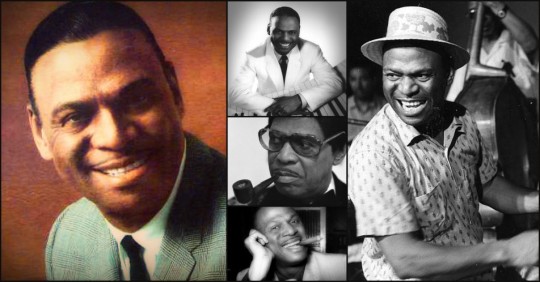

Earl “Fatha” Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one major source, is "one of a small number of pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz".

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (a member of Hines's big band, along with Charlie Parker) wrote, "The piano is the basis of modern harmony. This little guy came out of Chicago, Earl Hines. He changed the style of the piano. You can find the roots of Bud Powell, Herbie Hancock, all the guys who came after that. If it hadn't been for Earl Hines blazing the path for the next generation to come, it's no telling where or how they would be playing now. There were individual variations but the style of ... the modern piano came from Earl Hines."

The pianist Lennie Tristano said, "Earl Hines is the only one of us capable of creating real jazz and real swing when playing all alone." Horace Silver said, "He has a completely unique style. No one can get that sound, no other pianist". Erroll Garner said, "When you talk about greatness, you talk about Art Tatum and Earl Hines".

Count Basie said that Hines was "the greatest piano player in the world".

Biography

Early life

Hines was born in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, 12 miles from the center of Pittsburgh, in 1903. His father, Joseph Hines, played cornet and was the leader of the Eureka Brass Band in Pittsburgh, and his stepmother was a church organist. Hines intended to follow his father on cornet, but "blowing" hurt him behind the ears, whereas the piano did not. The young Hines took lessons in playing classical piano. By the age of eleven he was playing the organ in his Baptist church. He had a "good ear and a good memory" and could replay songs after hearing them in theaters and park "concerts": "I'd be playing songs from these shows months before the song copies came out. That astonished a lot of people and they'd ask where I heard these numbers and I'd tell them at the theatre where my parents had taken me." Later, Hines said that he was playing piano around Pittsburgh "before the word 'jazz' was even invented".

Early career

With his father's approval, Hines left home at the age of 17 to take a job playing piano with Lois Deppe and Hhis Symphonian Serenaders in the Liederhaus, a Pittsburgh nightclub. He got his board, two meals a day, and $15 a week. Deppe, a well-known baritone concert artist who sang both classical and popular songs, also used the young Hines as his concert accompanist and took him on his concert trips to New York. In 1921 Hines and Deppe became the first African Americans to perform on radio. Hines's first recordings were accompanying Deppe – four sides recorded for Gennett Records in 1923, still in the very early days of sound recording. Only two of these were issued, one of which was a Hines composition, "Congaine", "a keen snappy foxtrot", which also featured a solo by Hines. He entered the studio again with Deppe a month later to record spirituals and popular songs, including "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "For the Last Time Call Me Sweetheart".

In 1925, after much family debate, Hines moved to Chicago, Illinois, then the world's jazz capital, the home of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver. Hines started in Elite No. 2 Club but soon joined Carroll Dickerson's band, with whom he also toured on the Pantages Theatre Circuit to Los Angeles and back.

Hines met Louis Armstrong in the poolroom of the Black Musicians' Union, local 208, on State and 39th in Chicago . Hines was 21, Armstrong 24. They played the union's piano together. Armstrong was astounded by Hines's avant-garde "trumpet-style" piano playing, often using dazzlingly fast octaves so that on none-too-perfect upright pianos (and with no amplification) "they could hear me out front". Richard Cook wrote in Jazz Encyclopedia that

[Hines's] most dramatic departure from what other pianists were then playing was his approach to the underlying pulse: he would charge against the metre of the piece being played, accent off-beats, introduce sudden stops and brief silences. In other hands this might sound clumsy or all over the place but Hines could keep his bearings with uncanny resilience.

Armstrong and Hines became good friends and shared a car. Armstrong joined Hines in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Sunset Cafe. In 1927, this became Armstrong's band under the musical direction of Hines. Later that year, Armstrong revamped his Okeh Records recording-only band, Louis Armstrong's Hot Five, and hired Hines as the pianist, replacing his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, on the instrument.

Armstrong and Hines then recorded what are often regarded as some of the most important jazz records ever made.

... with Earl Hines arriving on piano, Armstrong was already approaching the stature of a concerto soloist, a role he would play more or less throughout the next decade, which makes these final small-group sessions something like a reluctant farewell to jazz's first golden age. Since Hines is also magnificent on these discs (and their insouciant exuberance is a marvel on the duet showstopper "Weather Bird") the results seem like eavesdropping on great men speaking almost quietly among themselves. There is nothing in jazz finer or more moving than the playing on "West End Blues", "Tight Like This", "Beau Koo Jack" and "Muggles".

The Sunset Cafe closed in 1927. Hines, Armstrong and the drummer Zutty Singleton agreed that they would become the "Unholy Three" – they would "stick together and not play for anyone unless the three of us were hired". But as Louis Armstrong and His Stompers (with Hines as musical director and the premises rented in Hines's name), they ran into difficulties trying to establish their own venue, the Warwick Hall Club. Hines went briefly to New York and returned to find that Armstrong and Singleton had rejoined the rival Dickerson band at the new Savoy Ballroom in his absence, leaving Hines feeling "warm". When Armstrong and Singleton later asked him to join them with Dickerson at the Savoy Ballroom, Hines said, "No, you guys left me in the rain and broke the little corporation we had".

Hines joined the clarinetist Jimmie Noone at the Apex, an after-hours speakeasy, playing from midnight to 6 a.m., seven nights a week. In 1928, he recorded 14 sides with Noone and again with Armstrong (for a total of 38 sides with Armstrong). His first piano solos were recorded late that year: eight for QRS Records in New York and then seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, all except two his own compositions.

Hines moved in with Kathryn Perry (with whom he had recorded "Sadie Green the Vamp of New Orleans"). Hines said of her, "She'd been at The Sunset too, in a dance act. She was a very charming, pretty girl. She had a good voice and played the violin. I had been divorced and she became my common-law wife. We lived in a big apartment and her parents stayed with us". Perry recorded several times with Hines, including "Body & Soul" in 1935. They stayed together until 1940, when Hines "divorced" her to marry Ann Jones Reed, but that marriage was soon "indefinitely postponed".

Hines married Janie Moses in 1947. They had two daughters, Janear (born 1950) and Tosca. Both daughters died before he did, Tosca in 1976 and Janear in 1981. Janie divorced him on June 14, 1979.

Chicago years

On December 28, 1928 (his 25th birthday and six weeks before the Saint Valentine's Day massacre), the always-immaculate Hines opened at Chicago's Grand Terrace Cafe leading his own big band, the pinnacle of jazz ambition at the time. "All America was dancing", Hines said, and for the next 12 years and through the worst of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Hines's band was the orchestra at the Grand Terrace. The Hines Orchestra – or "Organization", as Hines preferred it – had up to 28 musicians and did three shows a night at the Grand Terrace, four shows every Saturday and sometimes Sundays. According to Stanley Dance, "Earl Hines and The Grand Terrace were to Chicago what Duke Ellington and The Cotton Club were to New York – but fierier."

The Grand Terrace was controlled by the gangster Al Capone, so Hines became Capone's "Mr Piano Man". The Grand Terrace upright piano was soon replaced by a white $3,000 Bechstein grand. Talking about those days Hines later said:

... Al [Capone] came in there one night and called the whole band and show together and said, "Now we want to let you know our position. We just want you people just to attend to your own business. We'll give you all the Protection in the world but we want you to be like the 3 monkeys: you hear nothing and you see nothing and you say nothing". And that's what we did. And I used to hear many of the things that they were going to do but I never did tell anyone. Sometimes the Police used to come in ... looking for a fall guy and say, "Earl what were they talking about?" ... but I said, "I don't know - no, you're not going to pin that on me," because they had a habit of putting the pictures of different people that would bring information in the newspaper and the next day you would find them out there in the lake somewhere swimming around with some chains attached to their feet if you know what I mean.

From the Grand Terrace, Hines and his band broadcast on "open mikes" over many years, sometimes seven nights a week, coast-to-coast across America – Chicago being well placed to deal with live broadcasting across time zones in the United States. The Hines band became the most broadcast band in America. Among the listeners were a young Nat "King" Cole and Jay McShann in Kansas City, who said his "real education came from Earl Hines. When 'Fatha' went off the air, I went to bed." Hines's most significant "student" was Art Tatum.

The Hines band usually comprised 15- to 20 musicians on stage, occasionally up to 28. Among the band's many members were Wallace Bishop, Alvin Burroughs, Scoops Carry, Oliver Coleman, Bob Crowder, Thomas Crump, George Dixon, Julian Draper, Streamline Ewing, Ed Fant, Milton Fletcher, Walter Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Leroy Harris, Woogy Harris, Darnell Howard, Cecil Irwin, Harry 'Pee Wee' Jackson, Warren Jefferson, Budd Johnson, Jimmy Mundy, Ray Nance, Charlie Parker, Willie Randall, Omer Simeon, Cliff Smalls, Leon Washington, Freddie Webster, Quinn Wilson and Trummy Young.

Occasionally, Hines allowed another pianist sit in for him, the better to allow him to conduct the whole "Organization". Jess Stacy was one, Nat "King" Cole and Teddy Wilson were others, but Cliff Smalls was his favorite).

Each summer, Hines toured with his whole band for three months, including through the South – the first black big band to do so. He explained, "[when] we traveled by train through the South, they would send a porter back to our car to let us know when the dining room was cleared, and then we would all go in together. We couldn't eat when we wanted to. We had to eat when they were ready for us."

In Duke Ellington's America, Harvey G Cohen writes:

In 1931, Earl Hines and his Orchestra "were the first big Negro band to travel extensively through the South". Hines referred to it as an "invasion" rather than a "tour". Between a bomb exploding under their bandstage in Alabama (" ...we didn't none of us get hurt but we didn't play so well after that either") and numerous threatening encounters with the Police, the experience proved so harrowing that Hines in the 1960s recalled that, "You could call us the first Freedom Riders". For the most part, any contact with whites, even fans, was viewed as dangerous. Finding places to eat or stay overnight entailed a constant struggle. The only non-musical 'victory' that Hines claimed was winning the respect of a clothing-store owner who initially treated Hines with derision until it became clear that Hines planned to spend $85 on shirts, "which changed his whole attitude".

The birth of bebop

Hines provided the saxophonist Charlie Parker with his big break, until Parker was fired for his "time-keeping" – by which Hines meant his inability to show up on time, despite Parker's resorting to sleeping under the band stage in his attempts to be punctual. The Grand Terrace Cafe had closed suddenly in December 1940; its manager, the cigar-puffing Ed Fox, disappeared. The 37-year-old Hines, always famously good to work for, took his band on the road full-time for the next eight years, resisting renewed offers from Benny Goodman to join his band as piano player.

Several members of Hines's band were drafted into the armed forces in World War II – a major problem. Six were drafted in 1943 alone. As a result, on August 19, 1943, Hines had to cancel the rest of his Southern tour. He went to New York and hired a "draft-proof" 12-piece all-woman group, which lasted two months. Next, Hines expanded it into a 28-piece band (17 men, 11 women), including strings and French horn. Despite these wartime difficulties, Hines took his bands on tour from coast to coast. and was still able to take time out from his own band to front the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1944 when Ellington fell ill.

It was during this time (and especially during the recording ban during the 1942–44 musicians' strike ) that late-night jam sessions with members of Hines's band's lay the seeds for the emerging new style in jazz, bebop. Ellington later said that "the seeds of bop were in Earl Hines's piano style". Charlie Parker's biographer Ross Russell wrote:

... The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band's sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg.

As early as 1940, saxophone player and arranger Budd Johnson had "re-written the book" for the Hines' band in a more modern style. Johnson and Billy Eckstine, Hines vocalist between 1939 and 1943, have been credited with helping to bring modern players into the Hines band in the transition between swing and bebop. Apart from Parker and Gillespie, other Hines 'modernists' included Gene Ammons, Gail Brockman, Scoops Carry, Goon Gardner, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Benny Harris, Harry 'Pee-Wee' Jackson, Shorty McConnell, Cliff Smalls, Shadow Wilson and Sarah Vaughan, who replaced Eckstine as the band singer in 1943 and stayed for a year.

Dizzy Gillespie, in the Hines band at the time, said:

... People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit.

The links to bebop remained close. Parker's discographer, among others, has argued that "Yardbird Suite", which Parker recorded with Miles Davis in March 1946, was in fact based on Hines' "Rosetta", which nightly served as the Hines band theme-tune.

Dizzy Gillespie described the Hines band, saying, "We had a beautiful, beautiful band with Earl Hines. He's a master and you learn a lot from him, self-discipline and organization."

In July 1946, Hines received serious head injuries in a car crash near Houston which, despite an operation, affected his eyesight for the rest of his life. Back on the road again four months later, he continued to lead his big band for two more years. In 1947, Hines bought the biggest nightclub in Chicago, The El Grotto, but it soon foundered with Hines losing $30,000 ($364,659 today). The big-band era was over – Hines had had his for 20 years.

Rediscovery

In early 1948, Hines joined up again with Armstrong in the "Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars" 'small-band'. It was not without its strains for Hines. A year later, Armstrong became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time magazine (on February 21, 1949). Armstrong was by then on his way to becoming an American icon, leaving Hines to feel he was being used only as a sideman in comparison to his old friend. Armstrong said of the difficulties, mainly over billing, "Hines and his ego, ego, ego ...", but after three years and to Armstrong's annoyance, Hines left the All Stars in 1951.

Next, back as leader again, Hines took his own small combos around the United States. He started with a markedly more modern lineup than the aging All Stars: Bennie Green, Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, and Etta Jones. In 1954, he toured his then seven-piece group nationwide with the Harlem Globetrotters, but, at the start of the jazz-lean 1960s and old enough to retire, Hines settled "home" in Oakland, California, with his wife and two young daughters, opened a tobacconist's, and came close to giving up the profession.

Then, in 1964, thanks to Stanley Dance, his determined friend and unofficial manager, Hines was "suddenly rediscovered" following a series of recitals at the Little Theatre in New York, which Dance had cajoled him into. They were the first piano recitals Hines had ever given; they caused a sensation. "What is there left to hear after you've heard Earl Hines?", asked John Wilson of the New York Times . Hines then won the 1966 International Critics Poll for Down Beat magazine's Hall of Fame. Down Beat also elected him the world's "No. 1 Jazz Pianist" in 1966 (and did so again five more times). Jazz Journal awarded his LPs of the year first and second in its overall poll and first, second and third in its piano category. Jazz voted him "Jazzman of the Year" and picked him for its number 1 and number 2 places in the category Piano Recordings. Hines was invited to appear on TV shows hosted by Johnny Carson and Mike Douglas.

From then until his death twenty years later, Hines recorded endlessly both solo and with contemporaries like Cat Anderson, Harold Ashby, Barney Bigard, Lawrence Brown, Dave Brubeck (they recorded duets in 1975), Jaki Byard (duets in 1972), Benny Carter, Buck Clayton, Cozy Cole, Wallace Davenport, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Duke Ellington (duets in 1966), Ella Fitzgerald, Panama Francis, Bud Freeman, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Gonsalves, Stephane Grappelli, Sonny Greer, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Peanuts Hucko, Helen Humes, Budd Johnson, Jonah Jones, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, Ellis Larkins, Shelly Manne, Marian McPartland (duets in 1970), Gerry Mulligan, Ray Nance, Oscar Peterson (duets in 1968), Russell Procope, Pee Wee Russell, Jimmy Rushing, Stuff Smith, Rex Stewart, Maxine Sullivan, Buddy Tate, Jack Teagarden, Clark Terry, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Venuti, Earle Warren, Ben Webster, Teddy Wilson (duets in 1965 and 1970), Jimmy Witherspoon, Jimmy Woode and Lester Young. Possibly more surprising were Alvin Batiste, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Teresa Brewer, Barbara Dane, Richard Davis, Elvin Jones, Etta Jones, the Ink Spots, Peggy Lee, Helen Merrill, Charles Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Vi Redd, Betty Roché, Caterina Valente, Dinah Washington, and Ry Cooder (on the song "Ditty Wah Ditty").

But the most highly regarded recordings of this period are his solo performances, "a whole orchestra by himself". Whitney Balliett wrote of his solo recordings and performances of this time:

Hines will be sixty-seven this year and his style has become involuted, rococo, and subtle to the point of elusiveness. It unfolds in orchestral layers and it demands intense listening. Despite the sheer mass of notes he now uses, his playing is never fatty. Hines may go along like this in a medium tempo blues. He will play the first two choruses softly and out of tempo, unreeling placid chords that safely hold the kernel of the melody. By the third chorus, he will have slid into a steady but implied beat and raised his volume. Then, using steady tenths in his left hand, he will stamp out a whole chorus of right-hand chords in between beats. He will vault into the upper register in the next chorus and wind through irregularly placed notes, while his left hand plays descending, on-the-beat, chords that pass through a forest of harmonic changes. (There are so many push-me, pull-you contrasts going on in such a chorus that it is impossible to grasp it one time through.) In the next chorus—bang!—up goes the volume again and Hines breaks into a crazy-legged double-time-and-a-half run that may make several sweeps up and down the keyboard and that are punctuated by offbeat single notes in the left hand. Then he will throw in several fast descending two-fingered glissandos, go abruptly into an arrhythmic swirl of chords and short, broken, runs and, as abruptly as he began it all, ease into an interlude of relaxed chords and poling single notes. But these choruses, which may be followed by eight or ten more before Hines has finished what he has to say, are irresistible in other ways. Each is a complete creation in itself, and yet each is lashed tightly to the next.

Solo tributes to Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Ellington, George Gershwin and Cole Porter were all put on record in the 1970s, sometimes on the 1904 12-legged Steinway given to him in 1969 by Scott Newhall, the managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1974, when he was in his seventies, Hines recorded sixteen LPs. "A spate of solo recording meant that, in his old age, Hines was being comprehensively documented at last, and he rose to the challenge with consistent inspirational force". From his 1964 "comeback" until his death, Hines recorded over 100 LPs all over the world. Within the industry, he became legendary for going into a studio and coming out an hour and a half later having recorded an unplanned solo LP. Retakes were almost unheard of except when Hines wanted to try a tune again in some other wat, often completely different.

From 1964 on, Hines often toured Europe, especially France. He toured South America in 1968. He performed in Asia, Australia, Japan and, in 1966, the Soviet Union, in tours funded by the U.S. State Department. During his six-week tour of the Soviet Union, in which he performed 35 concerts, the 10,000-seat Kiev Sports Palace was sold out. As a result, the Kremlin cancelled his Moscow and Leningrad concerts as being "too culturally dangerous".

Final years

Arguably still playing as well as he ever had, Hines displayed individualistic quirks (including grunts) in these performances. He sometimes sang as he played, especially his own "They Didn't Believe I Could Do It ... Neither Did I". In 1975, Hines was the subject of an hour-long television documentary film made by ATV (for Britain's commercial ITV channel), out-of-hours at the Blues Alley nightclub in Washington, DC. The International Herald Tribune described it as "the greatest jazz film ever made". In the film, Hines said, "The way I like to play is that ... I'm an explorer, if I might use that expression, I'm looking for something all the time ... almost like I'm trying to talk." He played solo at Duke Ellington's funeral, played solo twice at the White House, for the President of France and for the Pope. Of this acclaim, Hines said, "Usually they give people credit when they're dead. I got my flowers while I was living".

Hines's last show took place in San Francisco a few days before he died in Oakland. As he had wished, his Steinway was auctioned for the benefit of gifted low-income music students, still bearing its silver plaque:

presented by jazz lovers from all over the world. this piano is the only one of its kind in the world and expresses the great genius of a man who has never played a melancholy note in his lifetime on a planet that has often succumbed to despair.

Hines was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

Style

The Oxford Companion to Jazz describes Hines as "the most important pianist in the transition from stride to swing" and continues:

As he matured through the 1920s, he simplified the stride "orchestral piano", eventually arriving at a prototypical swing style. The right hand no longer developed syncopated patterns around pivot notes (as in ragtime) or between-the-hands figuration (as in stride) but instead focused on a more directed melodic line, often doubled at the octave with phrase-ending tremolos. This line was called the "trumpet" right hand because of its markedly hornlike character but in fact the general trend toward a more linear style can be traced back through stride and Jelly Roll Morton to late ragtime from 1915 to 1920.

Hines himself described meeting Armstrong:

Louis looked at me so peculiar. So I said, "Am I making the wrong chords?" And he said, "No, but your style is like mine". So I said, "Well, I wanted to play trumpet but it used to hurt me behind my ears so I played on the piano what I wanted to play on the trumpet". And he said, "No, no, that's my style, that's what I like."

Hines continued:

... I was curious and wanted to know what the chords were made of. I would begin to play like the other instruments. But in those days we didn't have amplification, so the singers used to use megaphones and they didn't have grand-pianos for us to use at the time – it was an upright. So when they gave me a solo, playing single fingers like I was doing, in those great big halls they could hardly hear me. So I had to think of something so I could cut through the big-band. So I started to use what they call 'trumpet-style' – which was octaves. Then they could hear me out front and that's what changed the style of piano playing at that particular time.

In their book Jazz (2009), Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux wrote of Hines's style of the time:

To make [himself] audible, [Hines] developed an ability to improvise in tremolos (the speedy alternation of two or more notes, creating a pianistic version of the brass man's vibrato) and octaves or tenths: instead of hitting one note at a time with his right hand, he hit two and with vibrantly percussive force – his reach was so large that jealous competitors spread the ludicrous rumor that he had had the webbing between his fingers surgically removed.

Pianist Teddy Wilson wrote of Hines's style:

Hines was both a great soloist and a great rhythm player. He has a beautiful powerful rhythmic approach to the keyboard and his rhythms are more eccentric than those of Art Tatum or Fats Waller. When I say eccentric, I mean getting away from straight 4/4 rhythm. He would play a lot of what we now call 'accent on the and beat'. ... It was a subtle use of syncopation, playing on the in-between beats or what I might call and beats: one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and. The and between "one-two-three-four" is implied, When counted in music, the and becomes what are called eighth notes. So you get eight notes to a bar instead of four, although they're spaced out in the time of four. Hines would come in on those and beats with the most eccentric patterns that propelled the rhythm forward with such tremendous force that people felt an irresistible urge to dance or tap their feet or otherwise react physically to the rhythm of the music. ... Hines is very intricate in his rhythm patterns: very unusual and original and there is really nobody like him. That makes him a giant of originality. He could produce improvised piano solos which could cut through to perhaps 2,000 dancing people just like a trumpet or a saxophone could.

Oliver Jackson was Hines's frequent drummer (as well as a drummer for Oscar Peterson, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, Teddy Wilson and many others):

Jackson says that Earl Hines and Erroll Garner (whose approach to playing piano, he says, came from Hines) were the two musicians he found exceptionally difficult to accompany. Why? “They could play in like two or three different tempos at one time … The left hand would be in one meter and the right hand would be in another meter and then you have to watch their pedal technique because they would hit the sustaining pedal and notes are ringing here and that’s one tempo going on when he puts the sustaining pedal on, and then this hand is moving, his left hand is moving, maybe playing tenths, and this hand is playing like quarter-note triplets or sixteenth notes. So you got this whole conglomeration of all these different tempos going on”.

Of Hines's later style, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz says of Hines' 1965 style:

[Hines] uses his left hand sometimes for accents and figures that would only come from a full trumpet section. Sometimes he will play chords that would have been written and played by five saxophones in harmony. But he is always the virtuoso pianist with his arpeggios, his percussive attack and his fantastic ability to modulate from one song to another as if they were all one song and he just created all those melodies during his own improvisation.

Later still, then in his seventies and after a host of recent solo recordings, Hines himself said:

I'm an explorer if I might use that expression. I'm looking for something all the time. And oft-times I get lost. And people that are around me a lot know that when they see me smiling, they know I'm lost and I'm trying to get back. But it makes it much more interesting because then you do things that surprise yourself. And after you hear the recording, it makes you a little bit happy too because you say, "Oh, I didn't know I could do THAT!

Selected discography

Hines' first-ever recording was, apparently, made on October 3, 1923 at Richmond, Indiana, when he was aged 19. Records commercially available as new, as of February 2016, are shown emboldened in the lists below: many more usually available second-hand on e-bay

The 1930s, classic jazz and the swing era:

Louis Armstrong & Earl Hines: inc. "Weatherbird", "Muggles", "Tight Like This", "West End Blues": Columbia 1928: reissued many times inc. as The Smithsonian Collection MLP 2012

Jimmie Noone & Earl Hines: "At the Apex Club": Decca Volume 1 1928: reissued 1967 : Decca Jazz Heritage Series

Earl Hines Solo: 14 of his own compositions: QRS & OKeh: 1928/9: reissued many times (see below)

Earl Hines Collection: Piano Solos 1928-40: OKeh/Brunswick/Bluebird: Collectors Classics

That's a Plenty, Quadromania series 1928-1947 Membran, four CDs, 2006, an easily available collection

Deep Forest, ca. 1932-1933: Hep

'Swingin' Down, 1932-1934: Hep

Harlem Lament, 1933-1934, 1937-1938: Columbia

Earl Hines - South Side Swing 1934-1935: Decca

Earl Hines - The Grand Terrace Band: RCA Victor Vintage Series

[Besides the piano solos Hines recorded for QRS (1928) and OKeh (1928), in 1929 Hines signed with Victor and recorded a number of sides in 1929. In 1932, he signed with Brunswick and recorded with them through mid-1934 when he signed with Decca. He recorded 3 sessions for Decca in 1934 and early 1935. He did not record again until February, 1937 when he signed with Vocalion, for whom he recorded 4 sessions through March 1938. After another gap, he signed with Victor's Bluebird label in July 1939 and recorded prolifically right up the recording ban in mid-1942]

Swing to bebop transition years, 1939-1945:

(Big bands were particularly affected by the 1942-1944 American Federation of Musicians recording ban which also severely curtailed the recording of early bebop)

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols 1, 2, 1939-1940, Jazz Tribune/BMG

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols 3, 4, 1939-1942, 1945, Jazz Tribune/BMG

Earl Hines & The Duke's Men: (with Ellington side-men) (1st 1944): reissued Delmark 1994

Piano man: Earl Hines, his piano and his orchestra: 1939-1942, RCA Bluebird

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols. 5, 6, 1944, 1964, 1966, Jazz Tribune/BMG

Earl Fatha Hines and His Orchestra: 1945-1951, Limelight 15 766

Classics, 1947-1949 (includes Eddie South) Classics

After 1948 - and therefore after Big Band era:

Louis Armstrong All Stars: Live in Zurich 18 October 1949: Montreux Jazz Label

Louis Armstrong & The All Stars: Decca 1950 & 1951: reissued

Earl Hines: Paris One Night Stand: Verve/Emarcy France 1957

The Real Earl Hines: (1st "Rediscovery" concert at Little Theatre, NY, 1964) Focus & Collectibles Jazz Classics: reissued

Earl Hines: The Legendary Little Theatre Concert (2nd "Rediscovery" concert): Muse 1964

Earl Hines: Blues in Thirds: solo: Black Lion 1965

Earl Hines: '65 Solo - The Definitive Black & Blue Sessions: Black & Blue 1965

Earl Hines: Fatha's Hands - Americans Swinging in Paris EMI 1965

Earl Hines: Hines' Tune: (live in France with Ben Webster, Don Byas, Roy Eldridge, Stuff Smith, Jimmy Woode & Kenny Clarke): Wotre Music/Esoldun 1965: reissued

Once Upon a Time with Ellington side-men: Verve 1966

Stride Right with Johnny Hodges: Verve 1966

Jazz from a Swinging Era (with All-Star group in Paris): Fontana 1967

Earl Hines & Jimmy Rushing: Blues & Things 1967

Swing's Our Thing with Johnny Hodges: Verve 1967

Earl Hines: At Home: solo (on his own Steinway): Delmark 1969

Earl Hines: My Tribute to Louis: solo: Audiophile 1971 (recorded two weeks after Armstrong's death)

Earl Hines Plays Duke Ellington (New World, 1971-1975 [1988]) reissue of Master Jazz LPs

Earl Hines Plays Duke Ellington Volume Two (New World, 1971-1974 [1997]) reissue of Master Jazz LPs

Earl Hines: Hines plays Hines: The Australian Sessions: solo: Swaggie 1972

Duet!: (with Jaki Byard), Verve/MPS 1972

Earl Hines: Tour de Force & Tour de Force Encore: solo: Black Lion 1972

Earl Hines: Live at the New School: solo: Chiarascuro 1973

Earl Hines: A Monday Date: reissues of Hines' 15 1928/1929 QRS & OKEH solo recordings: Milestone 1973

Earl Hines: The Quintessential Recording Session: solo: Chiaroscuro 1973 (remakes of his eight 1928 solo QRS piano recordings)

Earl Hines: The Quintessential Continued: solo: Chiaroscuro 1973 (remakes of his seven 1928/9 solo OKEH piano recordings)

Earl Hines Plays Cole Porter (New World, 1974 [1996])

West Side Story (Black Lion 1974)

Hines '74 (Black & Blue, 1974)

The Dirty Old Men (Black & Blue, 1974) with Budd Johnson

Earl Hines at Sundown (Black & Blue, 1974)

Earl Hines/Stephane Grappelli duets, The Giants: Black Lion 1974

Earl Hines/Joe Venuti duets: Hot Sonatas: Chiaroscuro 1975

Earl 'Fatha' Hines: The Father of Modern Jazz Piano (five LPs boxed): three LPs solo (on Schiedmeyer grand) and two LPs with Budd Johnson, Bill Pemberton, Oliver Jackson: MF Productions 1977

Earl Hines: In New Orleans: solo: Chiarascuro 1977

An Evening With Earl Hines: with Tiny Grimes, Hank Young, Bert Dahlander and Marva Josie: Disques Vogue VDJ-534 1977

Earl 'Fatha' Hines plays Hits he Missed: (inc Monk, Zawinul, Silver): Direct to Disc M & K RealTime 1978

(It would seem that Hines' last-ever recording was on December 29, 1981.)

On anthologies:

The Complete Master Jazz Piano Series: 13 Hines solo numbers: Mosaic MD4 140 (with Jay McShann, Teddy Wilson, Cliff Smalls, etc.) 1969-1972

Les Musiques de Matisse & Picasso: included Louis Armstrong & Earl Hines: West End Blues: Naive 2002

As sideman:

With Benny Carter: Swingin' the '20s: Contemporary 1958

With Johnny Hodges: 3 Shades of Blue: Flying Dutchman 1970

Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tension and Trust

The moon is hugely pregnant out there, radiant, like pregnant women so often are.

So radiant that I can’t sleep. It s not the chaotic state of disarray and trickling feeling of being entirely disempowered, but the moon, which reassuringly returns, lockdown or not, at fault for my persistent insomnia.

Walking up my little hidden woods at the rear of my even more unseen home I though of the rabbit on the moon. He s trapped out there, unlike us, forever.

I felt sorry for him. But then again, may be it is by choice and love of all things moon that he is there, by choice, not trapped, not lonely, he is the moon's baby in the womb and is floating upside down in eternal embryonic waters waiting to be born every night.

My cat is even more sticky and kissy than usual and April is getting a touch too warm for furry feline limpets. He wants to be ON TOP OF ME, be my scarf, adoringly asphyxiating.

While I write this he s giving me reproachful looks as if he knows i m criticizing him in type.

Cats know everything.

Dog face in the other hands seems truly sad over our apparent lack of social bottom smelling escapades. I m trying to engage with him more and give him more treats and tricks but he's bored.

Me? I have two good days, one bad, closely connected to sleep. Meditation, training, eating, baking, mapping the daily slow movement of snails. Did you know snails have between 15 to twenty thousand teeth in their mouths? I didn’t.The sluggish slowness of days. My Ariadne, as I call my course tutor trying to guide us through the marshes of our minds, told me to try to go ‘slow’ after the whole home threatening eviction plus loss of two jobs in one month and panicking pandemic plus actual world pandemic post Barcelona trip happened.

So- snails are slow.

Bach apparently loved them and wrote a fair section of his music based on snails and other garden creatures- he was a loving and enthusiastic gardener, apparently.

The task of finding a tangential on my collective equilibrium project for fair and just futures- in other words, an apprentice to Calder’s aspirational mobile- made me think of the movement of the piece.

Not only how to document the trajectory and motion- long exposure photograph or Muybrige like motion perhaps?

But also, how to annotate it. Like music or dance, all the parts move simultaneously but following different trajectories, fixed in a larger space.

The only specific requirement beside the objective of collaborative balance for my model is:

Space.

A central empty void is needed to hang a mobile. Tall and wide enough for the fragile structure to move, pivot, swivel and balance, fixed yet flexible, suspended.

Space.

The only requirement to survive the Covid 19 outbreak.

Space.

The new movement we are having to learn is giving way on narrow lanes. Listening and carefully watching, responding and also - trust.

You trust that they will move, they trust that you will, we all move apart.

I thought of fish schools moving away yet keeping the perfect distance and density.

So we dance and move like sardines all packed up, in new ways to ensure survival of the specie and non death.

I started thinking about traditional dance and mimicking the natural world, in direct analogies such as Black swans flying in V formations at perfectly synchronised ballet- Matthew bourne introduces an interesting and radical gender reverse in his production to perfectly stilted ballerinas walking in long stilt like doll legs. In unison.

But ballet is only for the exclusive few, a performance that one observes and experiences vicariously, like theatre often is too, cinema, television.

All these are clearly divided spaces- at least in traditional productions- where the audience is not participatory.

So what was dance and what is dance and what could this new Covid dance be like?

Before I delve into notation and movement language- another turn of the maze and one I came straight to first and I’ m now ignoring- from exponentials and mathematical notations to the figure of eight.

Dance was originally means of expression from when? Tribal dances? They still have a common beat and were performed perhaps in order to communicate with the gods, beating drums and feet and hearts in one song.

Collective rather than individual?

Must research and learn more.

But then, after looking into the figure of eight problem and waltz, and realising the huge amounts of people that used to meet up and dance TOGETHER, like one body- not only in the rich salons of Vienna for the debutantes parties, but in the streets, at parties, asking the belle for a dance- it dawned on me that dance was even at a popular level an activity which connected strangers but that asked them to move TOGETHER. To listen to one another, to lead, to follow, to feel, to trust. But also, to improvise.

And seeing that we don’t know what tomorrow’s world will look like, we should probably get used to improvising.

(Mathew Bourne’s Swan Lake - I confess it did make me cry)

To dance in partnership or in groups you have to know the steps, and trust.

And try not to step on your partners toes, ideally.

Keep your balance. A mutual balance.

Improvisation work in contemporary dance is a good example.

But all ballroom dances require a dialogue of hands legs and hips- especially if you are Latin. Of all these, the hardest I found to learn was tango.

You have to connect and respond to the movements of the leading partner- generally male as tango could be seen as chauvinistic dance in that it is the men that lead.

In the other hand, I was grateful to respond. Women done always have to have the harder job- unless, you are in Brighton and your lesbian married couples are also dancing Tango, learning the lead.

The steps are difficult. Feeling them, responding in perfect timing and elegantly and with the ferociousness required, a true accomplishment of humane coordination of limbs, hearts and brains. Then hope for creativity, later, much later.

Just thinking about it exhausts me but it was a lot of fun once you could feel and not think and just swirl around a room full of people that never collided or tired.

My tango career fell short due to a my Achilles heel, an injury that has recently interrelated returned. How timely. May be I should not even think ‘dance’. My dancing days are far from over, but are carefully counted courtesy of having been a wild tree climbing horse riding down mountain rolling monkey that has thoroughly trashed one' s body. The only other tribe I know of that hurt themselves to the extent I have, are skateboarders.Now that s another interesting group of folk- skateboarders and the city. Mitha please don’t forget to return my book.

I am loosing my thread. It must be because it is two twenty two in the morning.

Two twenty three.

One two three for five six seven eight.

Sometimes it s one two three four.

In waltz, or a waltz in tango (also a possibility just to add to the complexity of the matter) one two three one two three dresses swiiiishing round and round the room.

The footage of people waltzing in the streets in London for the coronation of the Queen are mind blowing. It s an ocean in movement, hypnotized I watch it over and over again like a child.

When did we stop meeting in the square on Sundays to dance with our neighbours?

(Robert Capa- Women dancing in the streets of Moscow 1947. Sixty percent of men that left to battle didn’t make it back home)

When we go dancing these days- and even at my age I do and won’t miss an opportunity- we go to a club, a sweaty party where we throw ourselves around but dance in our minds and our bodies- mostly, alone.

With the exception of Latin vibes and then, it changes.

I m then back dancing with my sister- not in my mother's house dancing with my grandmother and all the family too for New Year’s Eve like we used to- but dancing with my blood, like we have since we were small.

I know she ll always catch me and throw me and that I can do the same without having to think. Practiced, life practice.

Trust of blood- yet when you know the dance and trust, you can dance the dance with anyone.Trust. They will catch you.

#dance#coviddance#balance#trust#movement#steps#collective#sustainabledesign#solangeleoniriarte#trajectory#united#improvise#creativity#futures

0 notes

Text

Bhim struck a conversation with the boys sitting next to him. All Mallu boys studying engineering and from Telichery- Northern part of Kerala. One of them was singing the songs blasting in the vehicle.

It turned out he was a good singer and even did an open jam session in one of the cafes in Kaza. The boys were good natured and easy going, making fun of each other, telling us stories, adventures, sharing funny videos of themselves. Then we coaxed him to sing some songs, the driver tuned out the volume, and so he began. Beautifully singing Hindi numbers while the driver took us through hair raising narrow hairpin bends that got your gut.

After some time, the musician guy at the back also joined in, and together they sang. It was a wonderful moment. The rough journey notwithstanding, it was pleasing to see such energy in the group.

We had already crossed the first ‘Nalla’ glacier water that was storming down and one could imagine how the full force would be. The driver said by evening it would completely block the route flooding it, hence no one started from Kaza post noon.

The landscape was ever changing with the Spiti river flowing, the massive valley opening on and off with the rocks filled road. I didn’t see grimace or tension in our driver’s face. Cool, smiling, talking now and then.

His skills were extraordinary navigating the vehicle over flooded water, really bad paths that one wrong step meant fatal. We had already crossed a diversion where one way was directed towards Chandratal while the other continued to Manali.

Enroute we saw shepherds, horses grazing with the magnificent mountains behind them. Honestly I don’t have the right words to describe what we experienced.. We were open mouthed, star struck seeing it unfold in front of us. The driver rightly said ‘If you want to see the real wild Spiti, it is this route’. We saw a group of foreigners trekking with a guide in the middle of nowhere going towards Chandratal.

We crossed Batal, where we passed by the famous Chacha Chachi dhaba, I remember seeing this in my friend Bunny’s post. But the driver wisely went ahead of all the dhabas that was super crowded and stopped at another place for lunch. Our bones were rattling when we got down from the jeep.

After quickly finishing up lunch, we were on our way again. We were counting the number of Nallas we crossed. Some of the man made stone bridges were damaged with glacier water and landslides. One could imagine how it would be when it snowed. By October the routes were closed off. Even now buses were not allowed to go on this route.

At one point, the route was really bad filled with rocks, mud, slush and flooding water. Bikes were stuck with the bikers falling off their bikes. And let me tell you this was a narrow on the edge route.There was one path I remember that was jammed with big rocks and gushing water and the driver had to reverse and rev up the engine repeatedly to go over it. We all became silent, hoping it won’t crack down. It was the sheer skill of the man that we made it through. Spiti tells you how thin the line is between life and death..

We saw the landscape now slowly moving away from Spiti. From the raw wild landscape with browns and stark barrenness, we could see patches of green then slowly the mountains were turning green, with this it was clear that we were leaving Spiti behind us.

As I saw the changes, I felt a pang in my heart, like a wound, I was leaving Spiti. Will I ever come back here? For almost two weeks we were in Spiti experiencing it’s magnificence, unpredictability and challenges, it felt more than bitter sweet, I felt a lump in my throat, a deep well of pain. Life is like that, everything is in motion and the only thing constant is change.

We briefly saw a good wide road for 15 minutes. The driver also said it would have been good if the entire route was like this but then one wouldn’t face the raw wilderness either. We saw loads of bikers and vehicles going from Manali to Kaza and vice versa. The mountains now were a luscious green with the fog enveloping them and even clouding the roads. This was a different landscape altogether.

Then we crossed Rohtang Pass – more like a fucking ‘Mela’(festival) I tell you. We were shocked when we saw people crowding the road, traffic jams like in the city. People renting jumpsuits to go near the snow, vendors and street hawkers it was crazy! It was more like Chowpatty in Bombay than a pass! The driver wisely didn’t stop telling us stopping here even for 5 minutes meant an hour late into reaching our destination.

But Murphy’s law prevails and how! On a narrow crossing because of the rains there was lot of soft mud and slush and a couple of big vehicles got stuck. The entire traffic was jammed. There was no option but to wait and we did for more than a hour and half. And that’s when you see people in their true colours. The bikers were the worst. Trying to overtake a traffic jam, one bike fell right in front of us because of his over smart moves.

One truck was stuck so bad that they were not able to move ahead. Bhim, the other boys, the driver, people from other vehicles helped pushing the truck. But not one and I mean not one single biker moved. With their fancy bikes and fancy gear, they were only fretting and fuming about getting delayed. And their registration plate? Delhi, Punjab and Haryana. Never breaking the stereotype.

The couple spoke to Bhim. The girl suggested some lovely places to hangout in Manali that evening. We were looking at cheap hostel options so they told us to stay in Old Manali side. They were digital content creators living in Bangalore.

We were finally on our way with the traffic clearing up and it looked beautiful as we moved ahead, the entire landscape turned lush dark green. It was raining hard and fast and the slopes were a sight to behold.

Spiti was gone and we were in the green landscapes of Manali. There was fog, there was rain and there was dangerous driving by the vehicles and bikers. Our driver was cool personified, navigating wet slippery slopes calmly.

We were crossing villages, amidst heavy rains reaching Manali. I remember one guy cycling on the road with his backpack, an Indian guy. The slopes were steep with hairpin bends. Finally we entered into Manali and got swamped by noise, pollution, roads and shops. We were back to civilisation or were we? Leaving the silent landscape of Spiti, we were in a different world.

The vehicle stopped near the new bus stand. It was 6.30 pm and we were on the road for 11 hours. The body took a solid toll. We could feel our bodies screaming, How much more? The route and the ride is definitely not for the faint hearted. One has to have balls of steel.

We wished the boys all the best, they were going to Kullu and doing the Kheerganga trek. The couple would stay in Manali for a couple of days. The guy gave us precise directions to go to the hostel with the amount to be paid to the auto guy, he was very helpful. He asked if we could meet them tomorrow for a drink but we were heading off to Dharamsala in the morning.

We thanked the driver profusely and tipped him. It was our way of thanking him in a small way. He gave a big smile and asked So will you guys visit Spiti again? What do we say? We smiled and said our goodbyes. The man would go back to Kaza early morning tomorrow.

We enquired at the bus stand about buses going to Dharamsala in the morning. There was one at 8.30 am so we had time. We were relieved we didn’t have to rush early.

We reached the beautiful hostel in Old Manali. The dorm beds were really cheap, very comfortable and no one was there in the room. We just dumped our backpacks, a quick fresh up and asked the guy managing the place for a cafe. It was 100 metres from the hostel.

In fact there were lots of options as we walked. As it was Old Manali, it retained its colonial charm with lovely eclectic cafes. We walked into a cafe called 1947. The best part about it was one could sit outside with the view of the river next to it. We settled in and immediately ordered chilled beers. I remember when we took that first sip, we went Aaah! 😊 After two weeks of roughing it, this was heaven!

Over pizzas and beer, we chatted, spoke about our sojourn in Spiti and the journey it was. We were now entering into a new journey, a new beginning. Tomorrow would be another long ride to Dharamsala.

Obstacles,People & Manali – Part XXI Bhim struck a conversation with the boys sitting next to him. All Mallu boys studying engineering and from Telichery- Northern part of Kerala.

0 notes

Text

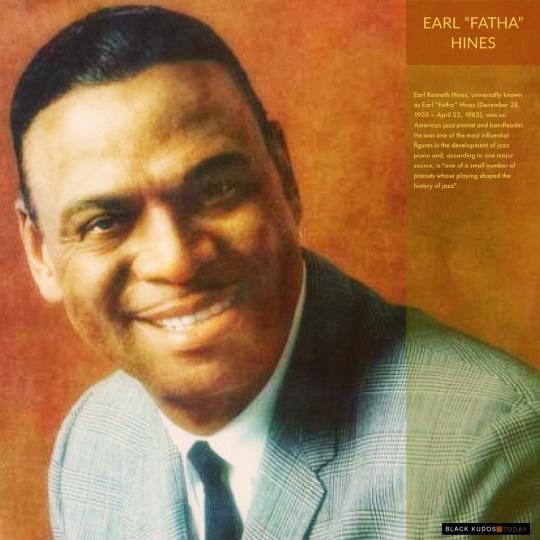

Earl "Fatha" Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl "Fatha" Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, "one of a small number of pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz".

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (a member of Hines's big band, along with Charlie Parker) wrote, "The piano is the basis of modern harmony. This little guy came out of Chicago, Earl Hines. He changed the style of the piano. You can find the roots of Bud Powell, Herbie Hancock, all the guys who came after that. If it hadn't been for Earl Hines blazing the path for the next generation to come, it's no telling where or how they would be playing now. There were individual variations but the style of ... the modern piano came from Earl Hines."

The pianist Lennie Tristano said, "Earl Hines is the only one of us capable of creating real jazz and real swing when playing all alone." Horace Silver said, "He has a completely unique style. No one can get that sound, no other pianist". Erroll Garner said, "When you talk about greatness, you talk about Art Tatum and Earl Hines".

Count Basie said that Hines was "the greatest piano player in the world".

Biography

Early life

Earl Hines was born in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, 12 miles from the center of Pittsburgh, in 1903. His father, Joseph Hines, played cornet and was the leader of the Eureka Brass Band in Pittsburgh, and his stepmother was a church organist. Hines intended to follow his father on cornet, but "blowing" hurt him behind the ears, whereas the piano did not. The young Hines took lessons in playing classical piano. By the age of eleven he was playing the organ in his Baptist church. He had a "good ear and a good memory" and could replay songs after hearing them in theaters and park concerts: "I'd be playing songs from these shows months before the song copies came out. That astonished a lot of people and they'd ask where I heard these numbers and I'd tell them at the theatre where my parents had taken me." Later, Hines said that he was playing piano around Pittsburgh "before the word 'jazz' was even invented".

Early career

With his father's approval, Hines left home at the age of 17 to take a job playing piano with Lois Deppe and His Symphonian Serenaders in the Liederhaus, a Pittsburgh nightclub. He got his board, two meals a day, and $15 a week. Deppe, a well-known baritone concert artist who sang both classical and popular songs, also used the young Hines as his concert accompanist and took him on his concert trips to New York. In 1921 Hines and Deppe became the first African Americans to perform on radio. Hines's first recordings were accompanying Deppe – four sides recorded for Gennett Records in 1923, still in the very early days of sound recording. Only two of these were issued, one of which was a Hines composition, "Congaine", "a keen snappy foxtrot", which also featured a solo by Hines. He entered the studio again with Deppe a month later to record spirituals and popular songs, including "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "For the Last Time Call Me Sweetheart".

In 1925, after much family debate, Hines moved to Chicago, Illinois, then the world's jazz capital, the home of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver. Hines started in Elite No. 2 Club but soon joined Carroll Dickerson's band, with whom he also toured on the Pantages Theatre Circuit to Los Angeles and back.

Hines met Louis Armstrong in the poolroom of the Black Musicians' Union, local 208, on State and 39th in Chicago. Hines was 21, Armstrong 24. They played the union's piano together. Armstrong was astounded by Hines's avant-garde "trumpet-style" piano playing, often using dazzlingly fast octaves so that on none-too-perfect upright pianos (and with no amplification) "they could hear me out front". Richard Cook wrote in Jazz Encyclopedia that

[Hines's] most dramatic departure from what other pianists were then playing was his approach to the underlying pulse: he would charge against the metre of the piece being played, accent off-beats, introduce sudden stops and brief silences. In other hands this might sound clumsy or all over the place but Hines could keep his bearings with uncanny resilience.

Armstrong and Hines became good friends and shared a car. Armstrong joined Hines in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Sunset Cafe. In 1927, this became Armstrong's band under the musical direction of Hines. Later that year, Armstrong revamped his Okeh Records recording-only band, Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, and hired Hines as the pianist, replacing his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, on the instrument.

Armstrong and Hines then recorded what are often regarded as some of the most important jazz records ever made.

... with Earl Hines arriving on piano, Armstrong was already approaching the stature of a concerto soloist, a role he would play more or less throughout the next decade, which makes these final small-group sessions something like a reluctant farewell to jazz's first golden age. Since Hines is also magnificent on these discs (and their insouciant exuberance is a marvel on the duet showstopper "Weather Bird") the results seem like eavesdropping on great men speaking almost quietly among themselves. There is nothing in jazz finer or more moving than the playing on "West End Blues", "Tight Like This", "Beau Koo Jack" and "Muggles".

The Sunset Cafe closed in 1927. Hines, Armstrong and the drummer Zutty Singleton agreed that they would become the "Unholy Three" – they would "stick together and not play for anyone unless the three of us were hired". But as Louis Armstrong and His Stompers (with Hines as musical director and the premises rented in Hines's name), they ran into difficulties trying to establish their own venue, the Warwick Hall Club. Hines went briefly to New York and returned to find that Armstrong and Singleton had rejoined the rival Dickerson band at the new Savoy Ballroom in his absence, leaving Hines feeling "warm". When Armstrong and Singleton later asked him to join them with Dickerson at the Savoy Ballroom, Hines said, "No, you guys left me in the rain and broke the little corporation we had".

Hines joined the clarinetist Jimmie Noone at the Apex, an after-hours speakeasy, playing from midnight to 6 a.m., seven nights a week. In 1928, he recorded 14 sides with Noone and again with Armstrong (for a total of 38 sides with Armstrong). His first piano solos were recorded late that year: eight for QRS Records in New York and then seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, all except two his own compositions.

Hines moved in with Kathryn Perry (with whom he had recorded "Sadie Green the Vamp of New Orleans"). Hines said of her, "She'd been at The Sunset too, in a dance act. She was a very charming, pretty girl. She had a good voice and played the violin. I had been divorced and she became my common-law wife. We lived in a big apartment and her parents stayed with us". Perry recorded several times with Hines, including "Body & Soul" in 1935. They stayed together until 1940, when Hines "divorced" her to marry Ann Jones Reed, but that marriage was soon "indefinitely postponed".

Hines married singer 'Lady of Song' Janie Moses in 1947. They had two daughters, Janear (born 1950) and Tosca. Both daughters died before he did, Tosca in 1976 and Janear in 1981. Janie divorced him on June 14, 1979.

Chicago years

On December 28, 1928 (his 25th birthday and six weeks before the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre), the always-immaculate Hines opened at Chicago's Grand Terrace Cafe leading his own big band, the pinnacle of jazz ambition at the time. "All America was dancing", Hines said, and for the next 12 years and through the worst of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Hines's band was the orchestra at the Grand Terrace. The Hines Orchestra – or "Organization", as Hines preferred it – had up to 28 musicians and did three shows a night at the Grand Terrace, four shows every Saturday and sometimes Sundays. According to Stanley Dance, "Earl Hines and The Grand Terrace were to Chicago what Duke Ellington and The Cotton Club were to New York – but fierier."

The Grand Terrace was controlled by the gangster Al Capone, so Hines became Capone's "Mr Piano Man". The Grand Terrace upright piano was soon replaced by a white $3,000 Bechstein grand. Talking about those days Hines later said:

... Al [Capone] came in there one night and called the whole band and show together and said, "Now we want to let you know our position. We just want you people just to attend to your own business. We'll give you all the Protection in the world but we want you to be like the 3 monkeys: you hear nothing and you see nothing and you say nothing". And that's what we did. And I used to hear many of the things that they were going to do but I never did tell anyone. Sometimes the Police used to come in ... looking for a fall guy and say, "Earl what were they talking about?" ... but I said, "I don't know - no, you're not going to pin that on me," because they had a habit of putting the pictures of different people that would bring information in the newspaper and the next day you would find them out there in the lake somewhere swimming around with some chains attached to their feet if you know what I mean.

From the Grand Terrace, Hines and his band broadcast on "open mikes" over many years, sometimes seven nights a week, coast-to-coast across America – Chicago being well placed to deal with live broadcasting across time zones in the United States. The Hines band became the most broadcast band in America. Among the listeners were a young Nat King Cole and Jay McShann in Kansas City, who said his "real education came from Earl Hines. When 'Fatha' went off the air, I went to bed." Hines's most significant "student" was Art Tatum.

The Hines band usually comprised 15-20 musicians on stage, occasionally up to 28. Among the band's many members were Wallace Bishop, Alvin Burroughs, Scoops Carry, Oliver Coleman, Bob Crowder, Thomas Crump, George Dixon, Julian Draper, Streamline Ewing, Ed Fant, Milton Fletcher, Walter Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Leroy Harris, Woogy Harris, Darnell Howard, Cecil Irwin, Harry 'Pee Wee' Jackson, Warren Jefferson, Budd Johnson, Jimmy Mundy, Ray Nance, Charlie Parker, Willie Randall, Omer Simeon, Cliff Smalls, Leon Washington, Freddie Webster, Quinn Wilson and Trummy Young.

Occasionally, Hines allowed another pianist sit in for him, the better to allow him to conduct the whole "Organization". Jess Stacy was one, Nat "King" Cole and Teddy Wilson were others, but Cliff Smalls was his favorite.

Each summer, Hines toured with his whole band for three months, including through the South – the first black big band to do so. He explained, "[when] we traveled by train through the South, they would send a porter back to our car to let us know when the dining room was cleared, and then we would all go in together. We couldn't eat when we wanted to. We had to eat when they were ready for us."

In Duke Ellington's America, Harvey G Cohen writes:

In 1931, Earl Hines and his Orchestra "were the first big Negro band to travel extensively through the South". Hines referred to it as an "invasion" rather than a "tour". Between a bomb exploding under their bandstage in Alabama (" ...we didn't none of us get hurt but we didn't play so well after that either") and numerous threatening encounters with the Police, the experience proved so harrowing that Hines in the 1960s recalled that, "You could call us the first Freedom Riders". For the most part, any contact with whites, even fans, was viewed as dangerous. Finding places to eat or stay overnight entailed a constant struggle. The only non-musical 'victory' that Hines claimed was winning the respect of a clothing-store owner who initially treated Hines with derision until it became clear that Hines planned to spend $85 on shirts, "which changed his whole attitude".

The birth of bebop

In 1942 Hines provided the saxophonist Charlie Parker with his big break, until Parker was fired for his "time-keeping" – by which Hines meant his inability to show up on time, despite Parker's resorting to sleeping under the band stage in his attempts to be punctual. Dizzie Gillespie joined the same year.

The Grand Terrace Cafe had closed suddenly in December 1940; its manager, the cigar-puffing Ed Fox, disappeared. The 37-year-old Hines, always famously good to work for, took his band on the road full-time for the next eight years, resisting renewed offers from Benny Goodman to join his band as piano player.

Several members of Hines's band were drafted into the armed forces in World War II – a major problem. Six were drafted in 1943 alone. As a result, on August 19, 1943, Hines had to cancel the rest of his Southern tour. He went to New York and hired a "draft-proof" 12-piece all-woman group, which lasted two months. Next, Hines expanded it into a 28-piece band (17 men, 11 women), including strings and French horn. Despite these wartime difficulties, Hines took his bands on tour from coast to coast but was still able to take time out from his own band to front the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1944 when Ellington fell ill.

It was during this time (and especially during the recording ban during the 1942–44 musicians' strike ) that late-night jam sessions with members of Hines's band's sowed the seeds for the emerging new style in jazz, bebop. Ellington later said that "the seeds of bop were in Earl Hines's piano style". Charlie Parker's biographer Ross Russell wrote:

... The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band's sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg.

As early as 1940, saxophone player and arranger Budd Johnson had "re-written the book" for the Hines' band in a more modern style. Johnson and Billy Eckstine, Hines vocalist between 1939 and 1943, have been credited with helping to bring modern players into the Hines band in the transition between swing and bebop. Apart from Parker and Gillespie, other Hines 'modernists' included Gene Ammons, Gail Brockman, Scoops Carry, Goon Gardner, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Benny Harris, Harry 'Pee-Wee' Jackson, Shorty McConnell, Cliff Smalls, Shadow Wilson and Sarah Vaughan, who replaced Eckstine as the band singer in 1943 and stayed for a year.

Dizzy Gillespie said of the music the band evolved:

... People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit.

The links to bebop remained close. Parker's discographer, among others, has argued that "Yardbird Suite", which Parker recorded with Miles Davis in March 1946, was in fact based on Hines' "Rosetta", which nightly served as the Hines band theme-tune.

Dizzy Gillespie described the Hines band, saying, "We had a beautiful, beautiful band with Earl Hines. He's a master and you learn a lot from him, self-discipline and organization."

In July 1946, Hines suffered serious head injuries in a car crash near Houston which, despite an operation, affected his eyesight for the rest of his life. Back on the road again four months later, he continued to lead his big band for two more years. In 1947, Hines bought the biggest nightclub in Chicago, The El Grotto, but it soon foundered with Hines losing $30,000 ($393,328 today). The big-band era was over – Hines' bands had been at the top for 20 years.

Rediscovery

In early 1948, Hines joined up again with Armstrong in the "Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars" "small-band". It was not without its strains for Hines. A year later, Armstrong became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Timemagazine (on February 21, 1949). Armstrong was by then on his way to becoming an American icon, leaving Hines to feel he was being used only as a sideman in comparison to his old friend. Armstrong said of the difficulties, mainly over billing, "Hines and his ego, ego, ego ...", but after three years and to Armstrong's annoyance, Hines left the All Stars in 1951.

Next, back as leader again, Hines took his own small combos around the United States. He started with a markedly more modern lineup than the aging All Stars: Bennie Green, Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, and Etta Jones. In 1954, he toured his then seven-piece group nationwide with the Harlem Globetrotters. In 1958 he broadcast on the American Forces Network but by the start of the jazz-lean 1960s and old enough to retire, Hines settled "home" in Oakland, California, with his wife and two young daughters, opened a tobacconist's, and came close to giving up the profession.

Then, in 1964, thanks to Stanley Dance, his determined friend and unofficial manager, Hines was "suddenly rediscovered" following a series of recitals at the Little Theatre in New York, which Dance had cajoled him into. They were the first piano recitals Hines had ever given; they caused a sensation. "What is there left to hear after you've heard Earl Hines?", asked John Wilson of The New York Times. Hines then won the 1966 International Critics Poll for Down Beat magazine's Hall of Fame. Down Beat also elected him the world's "No. 1 Jazz Pianist" in 1966 (and did so again five more times). Jazz Journal awarded his LPs of the year first and second in its overall poll and first, second and third in its piano category. Jazzvoted him "Jazzman of the Year" and picked him for its number 1 and number 2 places in the category Piano Recordings. Hines was invited to appear on TV shows hosted by Johnny Carson and Mike Douglas.

From then until his death twenty years later, Hines recorded endlessly, both solo and with contemporaries like Cat Anderson, Harold Ashby, Barney Bigard, Lawrence Brown, Dave Brubeck (they recorded duets in 1975), Jaki Byard (duets in 1972), Benny Carter, Buck Clayton, Cozy Cole, Wallace Davenport, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Duke Ellington (duets in 1966), Ella Fitzgerald, Panama Francis, Bud Freeman, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Gonsalves, Stephane Grappelli, Sonny Greer, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins, Milt Hinton, Johnny Hodges, Peanuts Hucko, Helen Humes, Budd Johnson, Jonah Jones, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, Ellis Larkins, Shelly Manne, Marian McPartland (duets in 1970), Gerry Mulligan, Ray Nance, Oscar Peterson (duets in 1968), Russell Procope, Pee Wee Russell, Jimmy Rushing, Stuff Smith, Rex Stewart, Maxine Sullivan, Buddy Tate, Jack Teagarden, Clark Terry, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Venuti, Earle Warren, Ben Webster, Teddy Wilson (duets in 1965 and 1970), Jimmy Witherspoon, Jimmy Woode and Lester Young. Possibly more surprising were Alvin Batiste, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Teresa Brewer, Barbara Dane, Richard Davis, Elvin Jones, Etta Jones, the Ink Spots, Peggy Lee, Helen Merrill, Charles Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Vi Redd, Betty Roché, Caterina Valente, Dinah Washington, and Ry Cooder (on the song "Ditty Wah Ditty").

But the most highly regarded recordings of this period are his solo performances, "a whole orchestra by himself". Whitney Balliett wrote of his solo recordings and performances of this time:

Hines will be sixty-seven this year and his style has become involuted, rococo, and subtle to the point of elusiveness. It unfolds in orchestral layers and it demands intense listening. Despite the sheer mass of notes he now uses, his playing is never fatty. Hines may go along like this in a medium tempo blues. He will play the first two choruses softly and out of tempo, unreeling placid chords that safely hold the kernel of the melody. By the third chorus, he will have slid into a steady but implied beat and raised his volume. Then, using steady tenths in his left hand, he will stamp out a whole chorus of right-hand chords in between beats. He will vault into the upper register in the next chorus and wind through irregularly placed notes, while his left hand plays descending, on-the-beat, chords that pass through a forest of harmonic changes. (There are so many push-me, pull-you contrasts going on in such a chorus that it is impossible to grasp it one time through.) In the next chorus—bang!—up goes the volume again and Hines breaks into a crazy-legged double-time-and-a-half run that may make several sweeps up and down the keyboard and that are punctuated by offbeat single notes in the left hand. Then he will throw in several fast descending two-fingered glissandos, go abruptly into an arrhythmic swirl of chords and short, broken, runs and, as abruptly as he began it all, ease into an interlude of relaxed chords and poling single notes. But these choruses, which may be followed by eight or ten more before Hines has finished what he has to say, are irresistible in other ways. Each is a complete creation in itself, and yet each is lashed tightly to the next.

Solo tributes to Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Ellington, George Gershwin and Cole Porter were all put on record in the 1970s, sometimes on the 1904 12-legged Steinway given to him in 1969 by Scott Newhall, the managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1974, when he was in his seventies, Hines recorded sixteen LPs. "A spate of solo recording meant that, in his old age, Hines was being comprehensively documented at last, and he rose to the challenge with consistent inspirational force". From his 1964 "comeback" until his death, Hines recorded over 100 LPs all over the world. Within the industry, he became legendary for going into a studio and coming out an hour and a half later having recorded an unplanned solo LP. Retakes were almost unheard of except when Hines wanted to try a tune again in some other way, often completely different.

From 1964 on, Hines often toured Europe, especially France. He toured South America in 1968. He performed in Asia, Australia, Japan and, in 1966, the Soviet Union, in tours funded by the U.S. State Department. During his six-week tour of the Soviet Union, in which he performed 35 concerts, the 10,000-seat Kiev Sports Palace was sold out. As a result, the Kremlin cancelled his Moscow and Leningrad concerts as being "too culturally dangerous".

Final years

Arguably still playing as well as he ever had, Hines displayed individualistic quirks (including grunts) in these performances. He sometimes sang as he played, especially his own "They Didn't Believe I Could Do It ... Neither Did I". In 1975, Hines was the subject of an hour-long television documentary film made by ATV (for Britain's commercial ITV channel), out-of-hours at the Blues Alley nightclub in Washington, DC. The International Herald Tribune described it as "the greatest jazz film ever made". In the film, Hines said, "The way I like to play is that ... I'm an explorer, if I might use that expression, I'm looking for something all the time ... almost like I'm trying to talk." In 1979, Hines was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. He played solo at Duke Ellington's funeral, played solo twice at the White House, for the President of France and for the Pope. Of this acclaim, Hines said, "Usually they give people credit when they're dead. I got my flowers while I was living".

Hines's last show took place in San Francisco a few days before he died in Oakland. As he had wished, his Steinway was auctioned for the benefit of gifted low-income music students, still bearing its silver plaque:

presented by jazz lovers from all over the world. this piano is the only one of its kind in the world and expresses the great genius of a man who has never played a melancholy note in his lifetime on a planet that has often succumbed to despair.

Hines was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Earl Hines among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.

Style

The Oxford Companion to Jazz describes Hines as "the most important pianist in the transition from stride to swing" and continues: