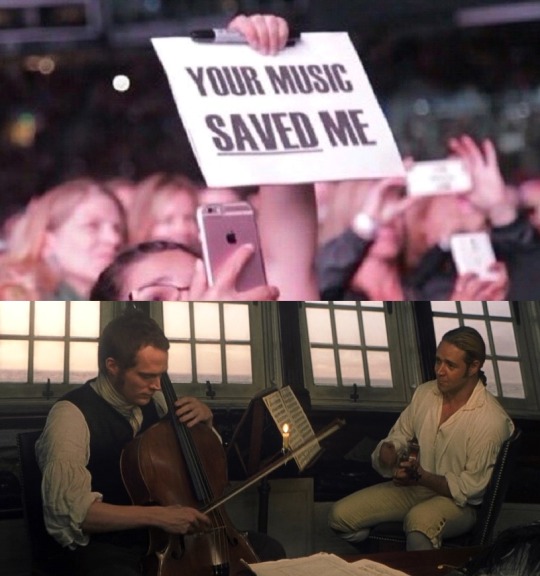

#this movie and the books introduced me to the beauty of baroque music

Text

#no matter how low i feel or how bad day i had this boccherini piece always brings me peace#this movie and the books introduced me to the beauty of baroque music#if is there ever was any positive influence that any piece of fiction had on my life that it is this#now i am going to a concert to hear some Handel and it is a first thing in a few weeks i am really excited about#master and commander#aubreyad#stephen maturin#jack aubrey#aubreyad memes

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

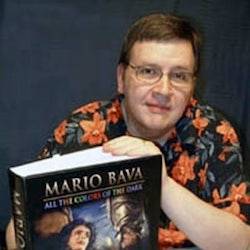

The Chiseler Interviews Tim Lucas

Born in 1956, film historian, novelist and screenwriter Tim Lucas is the author of several books, including the award-winning Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, The Book of Renfield: A Gospel of Dracula, and Throat Sprockets. He launched Video Watchdog magazine in 1990, and his screenplay, The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes, has been optioned by Joe Dante. He lives in Cincinnati with his wife Donna.

The following interview was conducted via email.

*

THE CHISELER: You're known for your longstanding love affair with horror films. Could you perhaps explain this allure they hold for you?

Tim Lucas: I suppose they’ve meant different things to me at different times of my life. When I was very young (and I started going to movies at my local theater alone, when I was about six), I was attracted to them as something fun but also as a means of overcoming my fears - I would sometimes go to see the same movie again until I could stop hiding my eyes, and I would often find out they showed me a good deal less than I saw behind my hands, so I learned that when I was hiding my eyes my own imagination took over. This encouraged me to look, but also to impose my own imagination on what I was seeing. Similarly, I remember flinching at pictures of various monsters in FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND magazine, then realizing that, as I became able to stop flinching, to look more deeply into the pictures, I began to feel compassion for Karloff’s Frankenstein Monster and admiration for Jack Pierce’s makeup. You could say that I learned some valuable life lessons from this: not to make snap judgements, not to hate or fear someone else because they looked different. I should also point out that beauty had the same intense effect on me as ugliness, in those early days at the movies. I was as frightened by the glowing light promising another appearance by the Blue Fairy in PINOCCHIO as I was by Stromboli or Monstro the Whale. I also covered my eyes when things, even colors, became too beautiful to bear.

As I got older, I found out that horror, science fiction, and fantasy films often told the unpleasant truths about our world, our government, our politics, and other people, before such things could be openly confronted in straightforward drama. So I’m not one of those people who are drawn to horror by gore or some other superficial incentive; I have always responded to them because they made me aware of unpopular truths, because they made me a more empathic person, and because they sometimes encompass a very unusual form of beauty that you can’t find in reality or in any other kind of film.

THE CHISELER: I'm fascinated by what you term "a very specific hybrid of beauty that you can’t find in reality or in any other kind of film.” Please develop that point.

Tim Lucas: For example, the aesthetic put forward by the films of David Lynch... or Tim Burton... or Mario Bava... or Roger Corman... or Val Lewton... or James Whale... or F.W. Murnau. It's incredibly varied, really; too varied to be summarized by a single name, but it's dark and baroque with a broader, deeper spectrum of color. I’ll give you an example: there is a Sax Rohmer novel called YELLOW SHADOWS - and only in a horror film can you see truly yellow shadows. Or green shadows. Or a fleck of red light on a vine somewhere out of doors. It’s a painterly version of reality, akin to what people see in film noir but even more psychological. It might be described as a visible confirmation of how the past survives in everything - we can see new artists quoting from a past master, making their essence their own.

THE CHISELER: Your definition of horror, to me, goes straight to the heart of cinema as an almost metaphysical phenomenon. My friend and frequent co-writer, Jennifer Matsui, once wrote: "Celluloid preserves the dead better than any embalming fluid. Like amber preserved holograms, they flit in and out of its parameters, reciting their own epitaphs in pantomime; revenant moths trapped in perpetual motion." Do Italian directors have what I guess you can call special epiphanies to offer? If so, does this help explain your Bava book?

Tim Lucas: The epiphanies of Italian horror all arise from the culture that was inculcated into those filmmakers as young people - the awareness of architecture, painting, writing, myth, legend, music, sculpture that they all grow up with. It's so much richer than any films that can be made by people with no foundation in the other art forms, people who makes movies just because they've seen a few - and maybe cannot even be bothered to watch any in black and white. I imagine many people go into the film business for reasons having to do with sex or power rather than having something deep down they need to express. The most stupid Italian and French directors have infinitely more in their artistic arsenals than directors from the USA, because they are brought up with an awareness of the importance of the Arts. No one gets this in America, where we slash arts and education budgets and many parents just sit their children in front of a television. Without supervision, without a sense of context, they will inevitably be drawn to whatever is loudest or most colorful or whatever has the most edits per minute. And those kids are now making blockbusters. They make money, so why screw with the formula? When I was a kid, it was still possible to find important, nurturing material on TV - fortunately!

Does it explain my Bava book? I don't know, but Bava's films somehow encouraged and sustained the passion that saw me through the researching and writing of that book, which took 32 years. When my book first came out, some people took me to task for its presumed excess - on the grounds that “our great directors” like John Ford and Orson Welles, for all their greatness, had never inspired a book of such size or magnitude. I could only answer that my love for my subject must be greater. But the thing about the Bava book, really, was that - at that time - the playing field was pretty much virgin territory in English, and Bava as a worker in the Italian film industry touched just about everything that industry had encompassed. All of those relationships needed charting. It would have been an insult to merely pigeonhole him as a horror director.

THE CHISELER: I discovered your publication, Video Watchdog, back in 2000 when Kim's Video was something of an underground institution here in NYC. I mean, they openly hawked bootlegs. There was a real sense of finding the unexpected which gave the place a genuine mystique. Now that you've had some time to reflect on its heyday, what are your thoughts, generally, on VW?

Tim Lucas: It's hard to explain to someone who just caught on in 2000, when things were already very different and more incorporated. VIDEO WATCHDOG began in 1990 as a magazine, but before that it was a feature in other magazines of different sorts that began in 1986. At that time, I was reviewing VHS releases for a Chicago-based magazine called VIDEO MOVIES, which then had a title change to VIDEO TIMES. I pointed out to my editor that his writers were reviewing the films and not saying anything about their presentation on video, and urged him to make more of a mandate about discussing aspect ratios, missing scenes (or added scenes) and such. I proposed that I write a column that would start collecting such information and that column was called "The Video Watchdog.”

In 2000, VW's origins in Beta and VHS and LaserDisc had evolved to DVD and Blu-ray was on the point of being introduced, so by then most of the battles we identified and fought had already been won and assimilated into the way movies were being presented on video. But in our early days, my fellow writers and I - were making our readers aware of filmmakers like Bava, Argento, Avati, Franco, Rollin, Ptushko, Zuławski - and the conversation we started led to people seeking out these films through non-official channels, even forming those non-official channels, until the larger companies began to realize there was an exploitable market there. Our coverage was never limited to horror - horror was sort of the hub of our interest, which radiated out into the works of any filmmaker whose work seemed in some way paranormal - everyone from Powell and Pressburger to Ishiro Honda to Krzystof Kiesłowski.

Now that the magazine is behind me, I can see more easily that we were part of a process, perhaps an integral part, of identifying and disseminating some very arcane information and, by sharing our own processes of discovery, raising the general consciousness about innumerable marginal and maverick filmmakers. A lot of our readers went on to become filmmakers (some already were) and many also went on to form home video companies or work in the business.

I'm proud of what we were able to achieve, and that what were written as timely reports have endured as still useful, still relevant criticism. Magazines tend to be snapshots of the present, and our back issues have that aspect, but our readers still tell me that the work is holding up, it’s not getting old.

When I say "we," I mean numerous writers who shared my pretentious ethic and were able to push genre criticism beyond the dismissive critical writing about genre film that was standard in 1990. I mentioned this state of things in my first editorial, that the gore approach wasn’t encouraging anyone to take horror as a genre more seriously, and I do think horror became more respectable over the years we were publishing.

THE CHISELER: My own personal touchstone, Raymond Durgnat, drilled deep into genre — particularly horror films — while pushing back instinctively against the Auteur Theory. No critic will ever write with more infatuated precision about Barbara Steele, whose image graces the cover of your Bava tome. Do you have any personal favorites in that regard; any individual author or works that acted as a kind of Virgil for you?

Tim Lucas: I haven't read Durgnat extensively, but when I discovered him in the 1970s his books FRANJU and A MIRROR FOR ENGLAND were gospel to me. Tom Milne's genre reviews for MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN were always intelligent and well-informed. Ivan Butler’s HORROR IN THE CINEMA was the first real book I read on the subject, along with HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT - and I remember focusing on Butler’s chapter on REPULSION, an entire fascinating chapter on a single film, which I hadn’t actually seen. It showed me the film and also how to watch it, so that when it finally came to my local television station, I was ready to meet it head on. David Pirie’s books A HERITAGE OF HORROR and THE VAMPIRE CINEMA I read to pieces. But it was Joe Dante's sometimes uncredited writing in CASTLE OF FRANKENSTEIN magazine that first hooked my interest in this direction - followed by the earliest issues of CINEFANTASTIQUE, which I discovered with their third issue and for which I became a regular reviewer and correspondent in 1972. I continued to write for them for the next 11 years.

THE CHISELER: I was wondering how you responded to these periodic shifts in taste and sexual politics, especially as they address horror movies — or even something like feminist critiques of the promiscuity of rage against women evident all throughout Giallo; the fear of female agency and power which is never too far from the surface. Are sexism, and even homophobia, simply inherent to the genre?

Tim Lucas: None of that really matters very much to me. I've been around so long now, I can see these recurring waves of people trying to catch their own wave of time, to make an imprint on it in some way. For some reason, I find myself annoyed by newish labels like "folk horror" and "J-horror" because such films have been with us forever; they didn't need such identification before and they have only been invented to get us more quickly to a point, and sometimes these au courant labels simply rebrand work without bringing anything substantially new to the discussion. Every time I read an article about the giallo film, I have to suffer through another explanation of what it is - and this is a genre whose busiest time frame was half a century ago. Sexism and homophobia are things people generally only understand in terms of the now, and I don’t know how fair it is to apply such concepts to films made so long ago. Think of Maria’s torrid dance in METROPOLIS and all those ravenous young men in tuxedos eating her with their eyes. Sexist, yes - but that’s not the point Lang was making.

I don’t particularly see myself as normal, but I suppose I am centrist in most ways. I don’t bring an agenda to the films I write about, other than wanting them to be as complete and beautifully restored as possible. That said, I am interested in, say, feminist takes on giallo films or homosexual readings of Herman Cohen films because - after all - we all bring ourselves to the movies, and if there’s more to be learned about a film I admire, from outside my own experience, that can be precious information. I want to know it and see if I can agree with it, or even if it causes me to feel something new and unfamiliar about it.

My only real concern is that genre criticism tends to be either academic or conversational (even colloquial), and we’re now at a point where the points made by articles published 20 or more years ago are coming back presented as new information, without any idea (or concern) that these things have already been said. As magazines are going by the wayside, taking their place is talk on social media, which is not really disciplined or constructive, nor indeed easily retrievable for reference. There are also audio commentaries on DVD and Blu-ray discs. Fortunately, there are a number of good and serious people doing these, but even when you get very intelligent or intellectual commentators, they often work best with the movie image turned off, because it’s a distraction from what’s being said. Is that true commentary? I'm not an academic; I’m an autodidact, so I don't have the educational background to qualify as a true intellectual, and I feel left out by a lot of academic writing. I do read a good deal and have familiarity with a fair range of topics, so I tend to frame myself somewhere between the vox populist and academia. That's the area we pursued in VW.

THE CHISELER: David Cairns and I once published a critical appreciation of Giallo, using fundamentally Roman Catholic misogyny — and, to a lesser extent, fear of gay men — as an intriguing lens. For example, lesbians are invariably sinister figures in these movies, while straight women ultimately function as nothing more than cinematographic objects: very fetishized, very well-lit corpses, you might say.

Tim Lucas: See, I admire a lot of giallo films but it would never occur to me to see them through a lens. I do, of course, because personal experience is a lens, but my lens is who I am and I’ve never had to fight for or defend my right to be who I am. I have no particular flag to wave in these matters; I approach everything from the stance of a film historian or as a humanist.

There is a lot of crossdressing and such in giallo, but these are tropes going back to French fin de siècle thrillers of the early 1900s, they don't really have anything to do with homophobia as we perceive it in our time. In the Fantomas novels, Souvestre and Allain (the authors) used to continually deceive their readers by having their characters - the good and the evil ones - change disguises, and sometimes apparently change sexes.

I remember Dario Argento saying that he used homosexual characters in his films because he was interested in their problems. He seldom actually explored their problems, and their portrayal in his earliest films is… quaint, to be kind about it… but it was a positive change as time played out. I think the fact that Argento’s flamboyant style attracted gay fans brought them more into his orbit and the vaguely sinister gay characters of his early films become more three dimensional and sympathetic later on, so in that regard his attention to such characters charts his own gradual embracing of them. So in a sense they chart his own widening embrace of the world, which is surprising considering what a misanthropic view of the world he presents.

THE CHISELER: But Giallo is roughly contemporaneous to the rise of Second Wave Feminism. Like the Michael & Roberta Findlay 'roughies', this is not a fossilized species of extinct male anger we're talking about here. Women's bodies are the energy of pictorial composition; splayed specifically for the delectation of some very confused and pissed off men in the audience. I know of no exceptions. To me it makes perfect sense to recognize the ritualized stabbings, stranglings, the BDSM hijinks in Giallo as rather obvious symptoms of somebody's not-so-latent fear and hatred.

Tim Lucas: I think that’s a modernist attitude that was not all that present at the time. Once the MPAA ratings system was introduced in late 1968, all genres of films got stronger in terms of graphic violence and language, and suspense thrillers were no exception. At the time, women and gay people were feeling freer, freer to be themselves, and were not looking for new ways to be taken out of films, however they might be represented. Neither base really had that power anyway at that time, but at any rate it wasn’t a time for them to appear more conservative. That would come at a later period when they felt more assured and confident in their equality. Throughout the 1960s, even in 1969 films like THE WRECKING CREW and BEYOND THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS, you can see that women are still playthings of a sort in films; there are starting to be more honest portrayals of women in films like HUD, but the prevailing emphasis of them is still decorative, so it makes sense that they would be no different in a thriller setting. There’s no arguing, I don’t think, that the murder scenes become more thrilling when the victim is a beautiful, voluptuous woman. It’s nothing to do with misogyny but rather about wanting to induce excitement from the viewer. If you look back to Janet Leigh’s character arc in PSYCHO, the exact same thing happens to her, but because she’s a well-developed character and time is given to explore that character and her goals and motivations, there is no question that it is a role women would want to play, even now. However, the same simply isn’t true of most giallo victims, which should not be seen as one of their rules but as one of their faults. In BLOOD AND BLACK LACE, I think Mario Bava shows us just enough of the women characters for us to have some investment in their fates - but when the giallo films are in the hands of sausage makers, you’re going to feel a sense of misogyny. It may be real but it may also be misanthropy or a more commercial mandate to pack more into a film and to sex it up. I should add that, because I’m not a woman or gay, I don’t bring personal sensitivities to these things, so I see them as something that just comes with the territory, like shoot-outs in Westerns. If you were to expunge anything that was objectionable from a giallo film, wouldn’t it be just another cop show or Agatha Christie episode? You watch a giallo film because, on some level, you want to see something with the hope of some emotional or aesthetic involvement, or with the hope of being outraged and offended. There is no end of mystery entertainment without giallo tropes, so it’s there if you demand that. Giallo films aren’t really about who done it, only figuratively; they are lessons in how to stage murder scenes and probably would not exist without the master painting of PSYCHO’s shower scene, which they all seek to emulate.

THE CHISELER: You mentioned Val Lewton earlier. Personally, I've never encountered anything like the overall tone of his films. There's always something startling to see and hear. Would you shed a little light on his importance?

Tim Lucas: He's an almost unique figure in film in that he was a producer yet he projected an auteur-like imprint on all his works. The horror films for which he's best known are not quite like any other films of their kind; I remember Telotte's book DREAMS OF DARKNESS using the word "vesperal" to describe the Lewton films' specific atmosphere - a word pertaining to the mood of evening prayer services, which isn't a bad way of putting it. I've always loved them for their delicacy, their poetical sense, their literary quality, and their indirectness - which sometimes co-exists with sources of florid garishness, like the woman with the maracas in THE LEOPARD MAN. In THE SEVENTH VICTIM, one shy character characterizes the heroine's visit to his apartment as her "advent into his world," and when I first saw it, I was struck by the almost spiritual tenderness and vulnerability of that description. Lewton was remarkable because he seems to have worked in horror because it was below the general studio radar, which allowed him to make extremely personal films. As long as they checked the necessary boxes, he could make the films he wanted - and I think Mario Bava learned that exact lesson from him.

THE CHISELER: I've always been fascinated by a question which is probably unanswerable: Why do you think it is that movies based on Edgar Allan Poe stories — even those films that only just pretend to sink roots in Poe, offering glib riffs on his prose at best — invariably bear fruit?

Tim Lucas: Poe's writings predate the study of human psychology and, to an extent, chart it - so he can be credited with founding a wing of science much like Jules Verne's writings were the foundation of science fiction and, later, science fact. Also, from the little we know of Poe's personal life, his writing was extremely personal and autobiographical, which makes it all the more compelling and resonant. It's also remarkably flexible in the way it lends itself to adaptation - there is straight Poe, comic Poe, arty Poe, even Poeless Poe. It helps too that a lot of people familiar with him haven't read him extensively, at least not since school, or think they have read him because they've seen so many Poe movies. The sheer range of approaches taken to his adaptation makes him that much more universal.

It also occurs to me that people are probably much more alike internally than they are externally, so the identification with an internal or first person narrator may be more immediate. But it's true that his work has inspired a fascinating variety of interpretation. You can see this at work in a single film: SPIRITS OF THE DEAD (1968), which I’ve written an entire book about. It’s three stories done by Roger Vadim, Louis Malle, and Federico Fellini - all vastly different, all terribly personal expressions of the men who made them.

THE CHISELER: Speaking of Poe adaptations, I've long thought it's time to confront Roger Corman's legacy; as an artist, a producer, an industrial muse, everything. Sometimes I think he's the single most important figure in cinema history. And if that's a wild overstatement, I could stand my ground somewhat and point out that no one person ever supported independent filmmakers with such profound results. It's as though he used his position at a mainstream Hollywood studio to open a kind of Underground Railroad for two generations of film artists. He gave so many artists a leg up in a business where those kinds of opportunities were never exactly abundant that it's hard to keep track. Entering the subject from any angle you like, what are your thoughts on Corman's overall contribution to cinema?

Tim Lucas: I can think of more important filmmakers than Corman, but there has never been a more important producer or mogul or facilitator of films. I said this while introducing him on the first of our two-night interview at the St. Louis Film Festival’s Vincentennial in 2011. He was largely responsible for every trend in American cinema during its most decisive quarter century - 1955 through 1980, and to some extent a further decade still, which bore an enormous influx of talent he discovered and nurtured. People talk about Irving Thalberg, Darryl F. Zanuck, Steven Spielberg, etc. - but their productions don’t begin to show the sheer diversity of interests that you get from Corman’s output. He has no real counterpart. I’ve spent a lot of the past 20 years musing on him, first as the protagonist of a comedy script I wrote with Charlie Largent called THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES, which Joe Dante has optioned. A few years ago, I decided to turn the script into a novel, which is with my agent now. It’s about the time period before, during, and after the making of THE TRIP (1966). It's a comedy but one with a serious, even philosophical side.

You know, Mario Bava once described himself to someone as “the Italian Roger Corman.” It’s incredible to me that Bava would have said that, not because it’s wrong or even because he was a total filmmaker before Corman made his first picture, but because Bava has been dead for so long! He’s been gone now almost 40 years and Roger is still making movies. And he’s been making movies for the DTV market longer than anybody, so he sort of predicted the current exodus of new movies away from theaters to streaming formats.

THE CHISELER: Are there any other producers/distributors you'd care to acknowledge, anyone that you think has followed in what you might call Corman’s Tradition of Generosity?

Tim Lucas: No, I really think he is incomparable in that respect. I do think it’s important to note, however, that I doubt Roger was ever purely motivated by generosity of spirit. I don’t think he would put money or his trust in anyone merely as a favor. He’s a businessman to his core and his gambles have always been based on projects that are likely to improve on his investment, even if moderately. I have a feeling that the first dollar he ever made is still in circulation, floating around out there bringing something new into being. I also don’t think he would give anyone their big break unless they had earned that break already in some respect. And when he does extend that opportunity, he’s got to know that, when these people graduate from his company, he’ll be sacrificing their talent, their camaraderie, maybe even in some cases their gratitude. So yes, there is some generosity in that aspect - but he also knows from experience that there are always new top students looking to extend their educations on the job. I wish more people in the film business had his selflessness, his ability to recognize and encourage talent. It may be his greatest legacy.

THE CHISELER: You introduced me, many years ago, to Mill of the Stone Women — I'll end on a personal note by thanking you and asking: Would you share an insight or two about this remarkable gem, particularly for readers who may not have seen it?

Tim Lucas: MILL OF THE STONE WOMEN was probably my first exposure to Italian horror; I saw it as a child, more than once, on local television and there were things about it that haunted and disturbed me, though I didn't understand it. Perhaps that's why it haunted and disturbed me, but the image of Helfy's hands clutching the red velvet curtains stayed with me for decades (a black and white memory) until I got to see it on VHS - I paid $59.95 for the privilege because my video store told me they would not be stocking it. It's a very peculiar film because Giorgio Ferroni wasn't a director who favored horror; the "Flemish Tales" that it's supposedly based on is non-existent, a Lovecraftian meta-invention, and it's the only Italian horror filmed in that particular region in the Netherlands. It looks more Germanic than Italian. I’m tempted to believe Bava may have had a hand in doing the special effects shot, which look like his work, but they might also have been done by his father Eugenio, as he was also a wax figure sculptor so would have been good to have on hand. He seldom took screen credit. So it's a film that has stayed with me because it's elusive; it's hard to find the slot where it belongs. It's like an adult fairy tale, or something out of E.T.A. Hoffmann. I can’t tell you how many hours I’ve wasted, trying to find another movie with the unique spell cast by that one.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matilda and Jackass

8/21/17

Greetings from screen, Rose, it’s Ramona!

So I like movies, a lot, as you know. And like any movie buff, I have a few movies that I absolutely love, whether or not they’re actually good. This weekend, I rewatched two of my favorite movies ever – Matilda, and Jackass.

These movies couldn’t be more different.

Matilda is based on a Roald Dahl novel about an intelligent, book-loving girl in a not-so-nice home. Luckily for her, she has telekinetic powers, and she uses them to help get her out of her situation. Jackass, however, is a movie about a group of friends that all do stupid stunts and pranks together for no reason other than making themselves laugh.

Now I don’t want to insinuate I love this movies in the same way, because I don’t. I love Matilda because when I first watched it as a kid, it inspired me to read and learn about the world around me, and introduced me to the idea that as long as you’re a good person and do your best to do good things, you’ll be alright. It’s also, in my opinion, a very well constructed story with beautiful camerawork. I love Jackass because the sheer bravery (and sometimes insanity) of the people doing these things is incredible, and it backfiring constantly is hilarious. But in terms of the actual art of filmmaking, it’s really not doing anything new. And yet, I can include them both in my list of “favorite movies”, much to the anger of some of my snobbier film fanatic friends.

And that’s really what I want to talk about today – the amount of snobbiness in what I’ll call “fandom”. This can refer to any community – gamers, bookworms, whatever. It seems like any time you get past the surface of any community, you get these people that are just obsessed with being “correct” in their opinions. People that only watch French films because they really “embrace the auteur” over there. Or only listen to baroque music because “it’s so much more intellectual than modern music”. Or those people who only read “literary fiction” instead of “genre fiction” (I don’t even know what this one means. Isn’t all literature literary, and don’t all stories fall into some kind of genre?).

I feel like these people miss the point. Not every creative work is made to fit the standards of “high art” or whatever. Sometimes, people just want to make things for the fun of it, or they only want to entertain their friends. And that’s fine. Encouraging that sort of stuff is how we get people making awesome new stuff. Do you think Kevin Smith really expected to become a multimillionaire with a long-running directorial career when he made Clerks? No! He wanted to make a movie because it was fun to do. Same thing with Robert Rodriguez, or the people at the company Rooster Teeth. They all just made things for the sake of it, and that let them be extra creative.

And this blog is kinda like that, isn’t it? I mean, this blog isn’t going to make us a ton of money or launch our careers or win us Pulitzers (I’d love to be proven wrong here). We’re doing this for each other, because we think it’s neat. And we get to break the rules, too! Like I can just end a post mid sen

0 notes