#they all had only antique magazines like nothing past 2005

Text

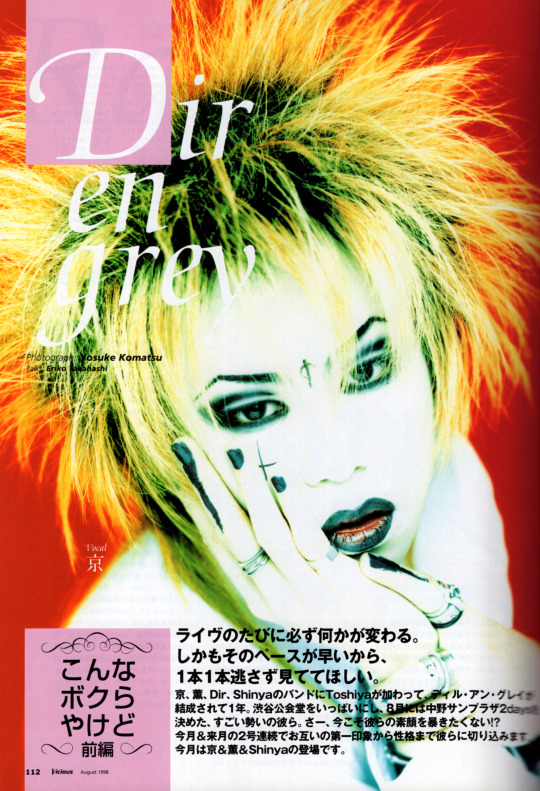

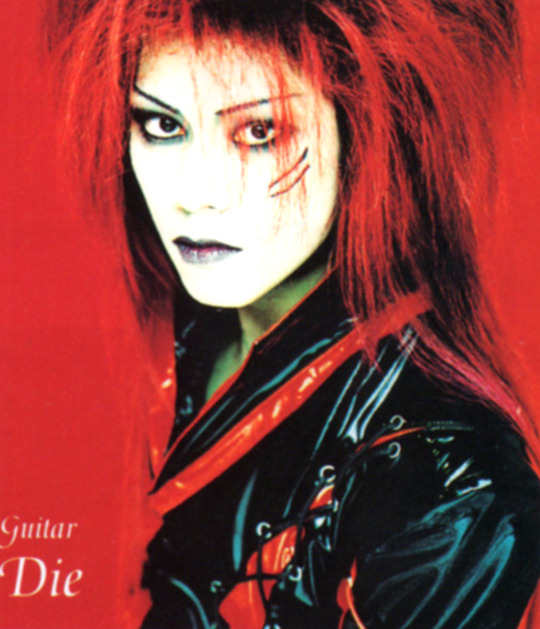

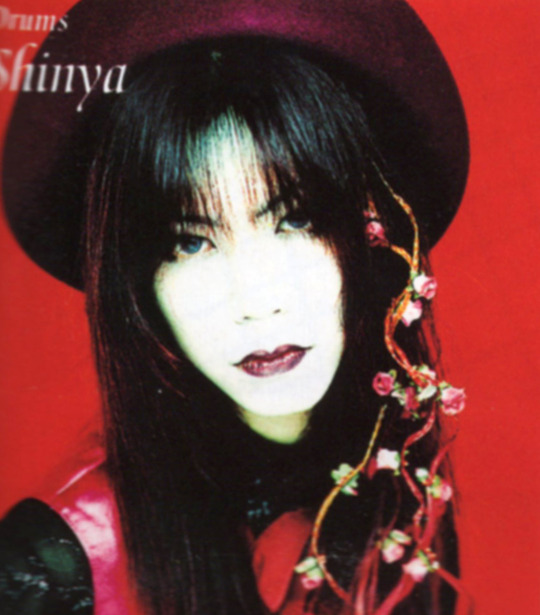

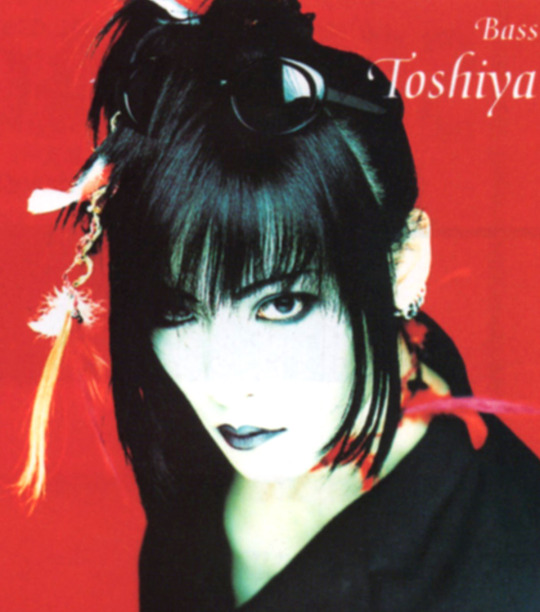

Vicious August 1998

#I know!#a rare post of old visual kei stuff from me!#the context for this is that on one of my trips after COVID-19#I tried to find a substitute store for Trio2 which had shut down in Nakano Broadway#I had read that there were some magazine shops at least in Ochanomizu#I didn't have data and tried to navigate with my geolocation skills but ended up asking a sort of old officer just to be sure#he said something along the lines of 'but I'm just an old man...'#so a younger man came to his and my rescue and offered to help me#he understood little English and used Google Translate to communicate with me for the most#turned out he was a magazine enthusiast himself and he took me to a couple of stores#they all had only antique magazines like nothing past 2005#he found everything that had Dir en grey at each of those stores#I felt bad after a while because it was not at all what I was looking for#so I ended up buying the Xth magazine that he showed me#see above hah#just so you know I was really close to the store just with my skills#Dir en grey#young#scans#magazine#visual kei#vkei#Kyo#Kaoru#Die#Shinya#Toshiya#makeup#I'm not sure why I'm such a fan of that middle finger nail paint

469 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another never-published travel story from the vaults, this one commissioned — but the magazine, an AAA publication, folded before my story ran. It’s safe to assume the over-the-top Indiana Theater in Terre Haute has landmark protection and the Frank Lloyd Wright house in Springfield, Ohio, is in fine shape, but re-reading this piece a decade later makes me wonder: Are those antiques shops filled with Midwestern glass and pottery still open, or have they gone the way of eBay? Did Richmond, Indiana’s Depot District ever take off? I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s all still more or less as described here.

The Historic National Road contains multitudes, from faded movie palaces and picturesque “pike towns” to cornfields and 1940s motor courts

A ROAD IS A ROAD IS A ROAD, some might say. But when it’s the Historic National Road, a 2002 Federal designation for that ribbon of highway conceived by Thomas Jefferson to open up the West, it’s nothing less than the road that built America.

Once the only road from the Eastern seaboard to the frontier, the National Road was begun in 1811 in Cumberland, Md., as a log-reinforced trail for pioneers’ wagons. It reached Vandalia, Il., by the 1830s, just in time to be superseded by rail travel. Later, that same road was used by bicycles and early automobiles, then partially paved with brick in 1914 to bear the weight of Army trucks on their way to war.

In the 1920s, the National Road was straightened, paved once more, and re-named U.S. Route 40. So it remains, a more tranquil alternative to I-70, the truck-jammed interstate that runs roughly parallel.

In some places, Route 40 is two lanes through cornfields and cow pastures. Elsewhere, brash 21st century commerce obscures the layers of history that lie in wait for those willing to slow down and look.

Girl Detective ISO History

In the spirit of a detective seeking the past behind the present, I set off with a friend from Terre Haute, Ind., to travel a 340-mile swatch of this once-vital artery through the hearts of Indiana and Ohio.

Over two days, we bounced around in time, encountering architectural gems from the Federal era to the Post-Modern. Here and there, where signs indicated, we turned off onto untouched sections of original early-19th century road, lopped off when 1920s builders chose a more direct course for Route 40. These eerily quiet, often overgrown stretches are the stuff of a road aficionado’s dreams, invariably worth the detour.

In once-glittering Terre Haute, a town built on breweries and baking powder, we got a closeup view of the 1922 Indiana Theater, a 2,000-seat movie palace dripping with ornamentation in Hollywood Baroque style. Precious few such intact theaters remain. This one, designed by John Eberson, the premier movie-house architect of his day, retains all its elaborate plaster work, including robust nudes holding up the lobby’s coffered ceiling.

Inspecting a framed pastel in the lobby, I communed with the swells in top hats and boas who flocked to the floodlit Indiana in its heyday. Built for vaudeville as well as films, the theater had its own orchestra, a Wurlitzer organ and live peacocks onstage. Today, it shows second-run films and rents itself out for theme weddings — but at least it’s still standing.

The National Road really sprang to life for me at Rising Hall, an imposing brick farmhouse in Stilesville, In., where we met 83-year-old homeowner Walt Prosser. Prosser remembers being taken, as a small child in the late 1920s, on a family outing to see this astonishing road with its double lanes of traffic. “It was miraculous,” he recalled. “Some cars going one way, and some the other!”

Rising Hall was built by Melville F. McHaffie in the late 1860s on land given to Civil War veterans in lieu of money. Prosser, a retired engineer, and his wife June, bought the house and its vintage barn in the 1980s. Long abandoned, except by marauding hogs and goats, they spend a decade restoring it and now give tours by appointment. With its arched windows and other Italianate details, it was and is the finest house around.

We got a vivid sense of what life was like in the 19th century for stagecoach passengers, pioneer families in their Conestoga wagons, livestock drovers and other travelers along the National Road at Huddleston Farm near Cambridge City, Ind. Now a museum, the three-story white brick inn and its outbuildings were among the many establishments that sprung up to take advantage of passing traffic. “This was the interstate of the 1940s,” said Joe Jarzen, executive director for the Indiana National Road Association, whose headquarters is at Huddleston Farm. “Several hundred wagons a day passed by here.”

Furnished rooms and an exhibit in the barn tell the story of John and Susannah Huddleston and their eleven children, who played all the angles: boarding weary travelers and their animals, providing blacksmithing and wagon repairs, selling brooms, cheese, flour and ammunition. “No liquor — they were Quakers,” Jarzen said.

If you time it right, you can attend a Civil War camp reenactment at Huddleston Farm of participate in one of the popular harvest suppers, where guests help prepare meals on an open hearth.

Centerville, Ind., is the region’s outstanding “pike town,” the term used for communities that developed and thrived because of their location along the National Road. Many of its lovingly restored brick rowhouses, separated by arched alleyways, are now used as guest houses, cafes or antique shops. The town bills itself as “the hub of Antique Alley,” some 1,300 dealers in a 33-mile stretch of eastern Indiana. A thousand of them, at least, are in behemoth antiques malls, where you’ll be overwhelmed by showcases full of made-in-Indiana glassware like Carnival, Fostoria and Heisey.

Off Route 40 in Richmond, on the Indiana-Ohio border, the ongoing rehab of the majestic brick-columned Pennsylvania Railroad Station, designed in 1906 by the Chicago firm of Daniel Burnham, is sparking positive change in the surrounding Depot District. The city is proud of its origins as an early center of jazz recording: Louis Armstrong and Hoagy Carmichael were among the musicians who got off the train at Richmond to record at the seminal Starr-Gennett studio. Elegant Victorian storefronts once housed barber shops, newsstands, cafes and bars for the convenience of fail passengers. Now there’s a gourmet Italian deli and kitchenware emporium, antiques shops, upstairs blues clubs and local eateries.

Our first stop in Ohio was the glorious Westcott House, a newly restored Frank Lloyd Wright masterwork just off Route 40 as it passes through Springfield. “Fallingwater gets all the attention,” grumbled Andrea Rossow, the operations coordinator. Maybe so, but the less well-known Westcott House was one of the architect’s own favorites, and it’s far less crowded.

Opened to the public in 2005 after a five-year, $5.8million restoration, the Prairie Style house was commissioned by Burton Westcott, who made his fortune in seeding machines and auto manufacturing, and his wife Orpha, in 1906. Designed after Wright’s first trip to Japan and steeped in Japanese influence, the house is set into a sculpted hillside, with a reflecting pool flanked by monumental urns, and small paned windows reminiscent of shoji screens. Inside, walls are trimmed with oak, and stained glass skylights suffuse the rooms with amber light. Just how ahead of his time the architect was is most evident in the kitchen, where the original cast-iron stove, decorated with Victorian scrollwork, looks incongruous against the building’s understated modernist lines.

Past Zanesville, a faded industrial town whose antique shops are crammed with highly collectible local pottery (Roseville, McCoy, Shawnee, Weller et al), several sandstone “S-bridges,” unique to the National Road, have been stabilized and preserved. So called because they zig-zag over streams, the 1820s S-bridges at Salt Fork, Peter’s Creek and Fox Run, which sheltered runaway slaves in their time, have been turned into small parks that make handy off-road picnic spots.

For our final foray before picking up the interstate to make time back to New York, we turned onto the most evocative remnant of original road yet. Peacock Road, paved with mossy brick, skirts a forest as it winds gently uphill past a clapboard farmhouse. The feeling of days gone by is palpable here and in nearby Old Washington, a town bypassed in the 1920s road re-construction and seemingly stuck in time, its deserted main street elevated by the presence of several grand pre-Civil War mansions.

Nostalgia gripped me time and again as we traveled the National Road and took its tempting detours. A turn of the steering wheel and you’re in the back of beyond, far removed from the rush of modern life.

Drive Slowly, Look Closely: Thru Indiana and Ohio on the Historic National Road Another never-published travel story from the vaults, this one commissioned -- but the magazine, an AAA publication, folded before my story ran.

#Antique Alley#Depot District#Historic National Road#Huddleston Farm#Indiana Theater#Peacock Road#pike towns#Rising Hall#Route 40#S-bridges#Starr-Gennett#Westcott House

1 note

·

View note