#process theology

Text

Slay the Princess and Process Theology

“You’re on a path in the woods. And at the end of that path is a cabin. And in the basement of that cabin is a princess. You’re here to slay her. If you don’t, it’ll be the end of the world.”

“Go and learn what this means: I desire mercy, not sacrifice.” -Matthew 9:13

I recently listened to a sermon about “process theology,” a subject of which I know little. The shortest summary I can give is that it holds God is not absolutely constant but changes in response to actions of humans and the wider world. This idea has quite a bit of biblical support- both Moses and Abraham successfully argue God into changing his mind, and Jesus at one point appears racist, calling a foreign woman a “dog” before being argued out of it. The preacher kept apologizing for the subject being dry and esoteric, but I was on the edge of my seat. He stated that people often see the God they expect to see, and that got me thinking about Slay the Princess. StP is a game I have played through several times over the past few months. I don’t want to get overly specific in case anyone reading wants to give it a shot, and its meaning is vague enough that each player will see it their own way. It’s a pretty easy game to play; there’s no real challenge, it’s more like a Choose Your Own Adventure book where the story unfolds and frequently stops to give you a list of options for how it should proceed.* What is interesting is that the Princess acts in response to your actions even if she couldn’t know what they were. For instance, if you approach her with a knife in hand, she is suspicious and cold, whereas if you approach unarmed she is hopeful and warm. This is not because she sees what you are doing, but because your own expectations color how you see her.

Through multiple replays, it becomes clear that the Princess is not one thing, but that she shifts between different appearances based on your own choices. There is a give and take between Player and Princess where each affects the other and is affected in turn. The third actor is the mysterious Narrator who instructs you to slay the princess with the claim that doing so will “save the world.” While he can occasionally force you to act, for the most part he is limited to trying to talk you into seeing things his way, and the Princess conversely tries to talk you out of killing her. The power of “persuasion” is, to my understanding, a major part of Process Theology. Each time you play the game, the Princess will seem different. It becomes clear that she is not a mere person, but something greater that you can only see one aspect of at a time.

“We are oceans reduced to shallow creeks.”

Am I saying the Princess is God? Maybe? There are a lot of valid interpretations, but this one might track. You’d have to play the game to decide for yourself, but what it comes down to is that her existence is only meaningful in relation to the player. These contrasts fill our lives. In Genesis, God separates the water from the land, yet the two are never truly separate. The world is full of these contrasts that aren’t really in conflict. Matter and energy. Particles and waves. The holy and the broken. The philosopher Heraclitus (thought to be an inspiration for the Gospel of John) was taken by the idea of “unity of opposites.” The player and the Princess are constantly at odds, yet their conflict defines each other.

“There is no constant! There is no center! Everything that is exists only in relation to everything that isn’t!”

And the world around you both also changes depending on how your relationship develops. Sometimes she is powerful and godlike and the cabin becomes a temple, sometimes she is vicious and feral and it becomes a cave. Sometimes you close yourself off to her, sometimes you become so close as to be inseparable.

“Does it matter where one thing begins and another ends?”

There is in fact a sort of theology in the game, a conflict between the Shifting Mound and the Long Quiet. The former is dynamic and impermanent, the latter static and immortal. You have the option of choosing between the two at the end, and neither can be reduced to good or evil. The Quiet is the traditional Platonic view of God as “immortal, unchanging,” while the Mound is the relational God of Process Theology. But the Mound allows for change and growth, while the Quiet promises a sort of eternal dullness. And if God values relationships and growth, the same must be true of us.

*https://www.slaytheprincess.com/ for a trailer and information about how to play. It’s available on Steam now.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whitehead, God, and Eternal Objects (Dialoguing with Darren Iammarino)

Darren and I had an intense geek out session exploring some of Whitehead’s categoreal scheme. Key points include:

The complex nature of eternal objects in Whitehead’s philosophy and the lack of consensus on the subject among scholars.

The interaction between eternal objects and actual occasions, and how this relates to the primordial and consequent natures of God.

The idea that the Eternal is…

View On WordPress

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The notion of God as Cosmic Moralist has suggested that God is primarily interested in order. The notion of God as Unchangeable Absolute has suggested God’s establishment of an unchangeable order for the world. And the notion of God as Controlling Power has suggested that the present order exists because God wills its existence. In that case, to be obedient to God is to preserve the status quo. Process theology denies the existence of this God.” - John Cobb; Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition; emphasis my own

#progressive christianity#christian#process theology#theology#john cobb#process#process philosophy#radical christianity#progressive christian#radical christian#christian socialism#christian communism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Mysticism means, as the word itself hints, not primarily special experiences or esoteric gifts, but a persistent attunement to the mystery. Every religion has its mystical tradition, its language of mystery, where words point towards the silence...These traditions cultivate discernment of the unknowable God -- or of what in other traditions does not bear the name God. As Lao Tzu, the great Chinese mystic of the Dao, the name for 'way,' put it over 2,500 years ago, the Dao that can be spoken is not the true Dao. All language is finite and creaturely, however inspired. Mystics groove on inspiration. But they rigorously negate, or as we say now, deconstruct, the absolutism that presumes to name the infinite like some person or entity over there; that knows God with any certainty, abstract or literal."

-Catherine Keller-

#catherine keller#quote#mysticism#process theology#daoism#taoism#god#theology#mystery#infinity#panentheism#pantheism

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that is so strange to me now after all these years is how people view scripture as like, a list of rules/beliefs rather than just like... a compilation of ancient documents (of stories, myths, culture) with the potential to inspire us spiritually.

Scripture should be just the starting point. You can read about people from an ancient culture that had a relationship with God (sometimes good sometimes bad) and build upon/improve what they started using your own experiences.

#why i also find it important to go beyond the Bible in finding wisdom too because it's everywhere!!!#but I'm most attracted to the Bible because I like Jesus and it gives context for his tradition and what formed after#progressive christian#process theology

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fusion of Horizons and the Cobb Institute

The Fusion of Horizons and the Cobb Institute

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” custom_margin=”||||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||||false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_image…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Panentheism and Process Theology:

At the theologate in Chicago where I studied theology, social ethics and pastoral ministry I had a Franciscan professor who was a brilliant theologian, Fr. Zachary Hayes. His own academic mentor was Cardinal Ratzinger at the University of Tubingen. It was through Fr. Zack that I learned about Process Theology. He wrote a fascinating book called "A Window to the Divine: Creation Theology" where he tells us,

Our tradition is rooted in the belief that, however the universe may look empirically, it is precisely this universe described to us at the empirical level by the sciences that our faith holds to be the fruit of God's creative knowledge and love.

Process theology teaches that everything that exists—including God—is in an eternal process of growing and becoming. This accepts the premise that we are all one with God and that God and the world exist in mutual interdependence. God then can be more clearly understood as the mens (mind) that St. Augustine was talking about when he attempted to define God the creator in relation to the Trinity. God is the creational intelligence that is constantly luring the world to good values and draws us to relationships with himself and all of creation (which he subsists in).

This graph below and the video above highlight the distinction between panentheism, typical theism, and atheism/pantheism.

This is consistent with what I learned as a thomistic understanding of God as one that is the self-subsisting process of existence (Deus sit ipsum esse subsistens). This is the notion that God is not a supreme being but the intelligence that motivates and moves creation. The God that we typically imagine, and the one that atheist rails against, is the image of God that exists as an entity outside of creation. He creates it and influences it, but he exists somewhere outside of it. This is not the God of Augustine, Aquinas and Process Theology.

It is precisely this image of the cosmic Christ that St. Paul tells us about when he says "Christ is all and in all" (Col. 3:11). It is with this understanding that St. Paul invites us to "let the word of Christ dwell in you richly." a few verses later. Panentheism is not some nouveau spirituality that competes with traditional Christianity, it is the way the early Christian community understood God as they accepted the concept of divinization and taught us that "God became human so that humans could become God."

This is how the famed Franciscan mystic, Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM, identifies the basis of Christian Spirituality in his book, “The Universal Christ.” Here he reflects on St. Paul’s notion of the Body of Christ as the “collective unconscious” where we enjoy a shared “common identity, already in place, that is driving and guiding us forward” (Rohr, Ch. 3).

Paul merely took incarnationalism to its universal and logical conclusions. We see this in his bold exclamation, “There is only Christ. He is everything and he is in everything” (Colossians 3:11). If I were to write that today, people would call me a pantheist (the universe is God), whereas I am really a panentheist (God lies within all things, but also transcends them), exactly like both Jesus and Paul. (Rohr, Ch. 3)

Fr. Rohr will have us Christians really delve into the idea of the cosmic Christ based on the early Church's notion of existing "in Christ." To make this case, he reminds us that in Galatians 1:16 St. Paul tells us that "God revealed his Son in me." If St. Paul understood Christ as one who alone is divine in a way that is not relevant to our entire humanity, as many of us do, why would he not say "God revealed his Son to me" instead. The invitation here is for us Christians to once again reconcile with the cosmic Christ and to identify with our panentheism theology. This will have tremendous spiritual repercussions for us and our Worldview.

I hope that you will and enjoy the full meaning of that short, brilliant phrase (en Cristo), because it is crucial for the future of Christianity, which is still trapped in a highly individualistic notion of salvation that ends up not looking much like salvation at all. All of us, without exception, are living inside of a common identity, already in place, that is driving and guiding us forward. Paul calls this bigger Divine identity the "mystery of his purpose, the hidden plan he so kindly made en Cristo from the very beginning" (Ephesians 1:9-10). Today, we might call it the "collective unconscious."

The beauty of this wisdom is shared by Fr. Rohr in the comment he offers as he contemplates the theological mystery of quantum entanglement:

God is not “in” heaven nearly as much as God is the force field that allows us to create heaven through our intentions and actions.

Contemporary mystic, Eckhart Tolle, takes this belief and wonderfully integrates it within an interfaith spirituality. In the following quote, he agrees with Fr. Rohr's insights on the fundamental teachings of Jesus and his identity as the cosmic Christ, but then he also adds a broader spiritual perspective from other faith traditions. You can find this in his appropriately titled book "Oneness with All Life."

The Truth is inseparable from who you are. Yes, you are the Truth. The very Being that you are is Truth. Jesus tried to convey that when he said, "I am the way and the truth and the life." These words are one of the most powerful and direct pointers to the Truth, if understood correctly. Jesus speaks of the innermost I Am, the essence identity of every man and woman, every life-form, in fact. He speaks of the life that you are. Some Christian mystics have called it the Christ within; Buddhists call it your Buddha nature; for Hindus, it is Atman, the indwelling God. When you are in touch with that dimension within yourself - and being in touch with it is your natural state, not some miraculous achievement - all your actions and relationships will reflect the Oneness with All Life that you sense deep within. This is love.

The only disagreement I would have with this awesome insight is the lack of the miraculous. To enter into Christ is to transcend oneself into the divine. To achieve this requires us to go beyond ourselves and to submit to the divine that we have corrupted within our nature. This requires the miracle of grace, our partner in this dance.

That, for me, is the fundamental truth of Christian Panentheism and the recognition of process theology.

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

“Everything Is Good” based on Zephaniah 3:14-20 and 1 Timothy 4:1-6, 9-10

I was trained in process theology, which focuses on genuine free-will and understands God to be all-good and all-knowing, but NOT all powerful (because that would defy free will). These days I mostly don't think about process theology, it just sort of flows through me without awareness. But then I came upon the line from 1 Timothy, “For everything created by God is good, and nothing for rejection, rather received with thanksgiving.”1

Reading that, my heart leapt for joy! An affirmation of the goodness of creation! YES! A reminder to focus on the good! YES! A move towards gratitude, as spiritual practice, YES!

And about that far into my excitement, I found the counter-narrative building up in me. Because there are weapons of mass destruction and addictive recreational drugs and I'm not willing to go so far as to claim they are good. Now, if you want an easy way out of this, you can say simply that “everything created by GOD is good” and not everything created by humans. Truthfully, that's probably a good distinction.

But, this is where I find I'm truly a process theologian. Process theology says that any capacity that exists can be used for good or for evil, and that as capacity increases so too does the capacity for good and in equal measure the capacity for evil. So, power. Any given power can be used for good, or for evil. To go back to my prior examples, we might think of the scientific and engineering minds as well as the money that was used to create weapons of mass destruction and that those resources could have been used quite differently – maybe to modernize the electrical grid or enable tree planting to fight climate change or... all sorts of things. The capacities can be used for God. God intends them for good. But we are free to choose how we use them.

Unfortunately, quite often, people choose to use power and capacity for evil. The reasons are wise ranging, and quite often those doing great harm are doing so because they were also harmed, but the truth is that there is a lot of bad stuff out there. And society is rife with collective horrible decisions.

And, I think there is wisdom still in 1 Timothy's “For everything created by God is good, and nothing for rejection, rather received with thanksgiving.” Because I think God did create everything for good, and nothing for rejection – and WE have choices about how we use stuff.

In Dr. Gafney's reflections on this text she said, “The Epistle is highlighting how very much opposite of the spirit and teaching of Christ are the false doctrines they are rebuking; doctrines that limit and exclude.”2 Now, this argument is powerful and beautiful, and should be held carefully.

My specific concern is the decision made by the early Church to not require followers of Jesus to follow kosher guidelines. I think that decision was fine, but I also think it it is a faithful choice for Jewish people to be kosher, and for religions to have dietary codes. I'm reminded of a young friend who kept kosher, and was willing to talk about it who said, “It is what I can do to remind myself regularly of God.” Beautiful.

Which I guess is to say that religious dietary codes can be good.

And lack of them can be good.

The capacity of all things to be good makes space for us to consider what it means to use any given thing FOR good. How can we sanctify something in how we choose to use it? 1 Timothy says, “For it is sanctified by God's word and prayer,” but I think there is a little bit more to it.

If everything is made to be good then even the most basic parts of our lives are sanctified. What does it mean to eat with an awareness of the goodness of the food we have, and God's blessings on it? Does that change the pace at which we eat, the presence of prayers of grace, the amount of attention we give to the flavors of our food? Does it impact what we choose to eat when we are thinking of eating itself as a potential moral good for ourselves and the world?

What does it mean to think of sleep as GOOD? How does that impact how we approach it?

Or, this was a recent insight for me, what does it mean to think of exercise as “the opportunity to move with joy?” (Because if I'm honest I have mostly thought of it as “the best way to quickly punish my body for the fact that I sit too much.”) I think maybe thinking of exercise as a good gift from God can create some pretty radical changes for me.

Or, what does it mean to notice the goodness and sanctity of … the chance to sing a hymn together, or the joy of a cup of tea, or a random meeting on the sidewalk? The simple little things that make up our days and our weeks, what if they ARE all meant for good?

There was a line in a commentary on Ezra that I read in preparation for out Bible Study that really stood out for me. The author, Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi who is a Rabbi, points out that Ezra is not focused on the work of heroes but rather on the work of the people as a whole. She says, “Success is not a return to glory but the sanctification of the mundane, 'daily, prose-bound, routine.'”3

Sanctification: making something holy. So “success” is finding the holy in the mundane.

Now, the things that have done great harm to us or others – we need to be clear those were not God's intent – but what if God is working with us to transform them anyway? To bring healing and to make it possible to bring whatever good is able to come out of even great harm. (From Zechariah, “I will change their shame into praise.”)

What if God is up to all kinds of good all the time all around us and all we have to do is notice?

Wouldn't that be wonderful?

Isn't that wonderful?

Amen

1 1 Timothy 4:4,Translation by Wilda Gafney, A Women's Lectionary for the Whole Church (New York, NY: Church Publishing, 2021), p. 49.

2 Wilda Gafney, A Women's Lectionary for the Whole Church, p. 50.

3 Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, In an Age of Prose: A Literary Approach to Ezra-Nehemiah (Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press, 1988), p. 187.

January 29, 2023

#thinking church#progressive christianity#fumc schenectady#schenectady#umc#sorry about the umc#rev sara e baron#pandemic preaching#first umc schenectady#Claremont School of theology#Process Theology#Wonderful#Good#Everything is good#1 Timothy#A Women's Lectionary for the Whole Church#Dr. Wilda Gafney

0 notes

Text

Hanging on to Easter: from "a flailing, dying parish"

Hanging on to Easter: from “a flailing, dying parish”

It has been a lovely, meaningful Holy Week. And I’m looking forward to a beautiful Easter Sunday. This in spite of being told that my church is not only a “flailing, dying parish,” but is also “in schism . . . quite possibly from the Christian faith in general.” Funny, being told that my faith isn’t Lutheran, let alone ‘Christian,’ since the center of every worship service is – well, Christ.

I…

View On WordPress

#Christianity#ELCA#gay lesbian ordination#inclusive church#inclusive langauage#inclusivity#lgbt#Lutheran#post-critical naiveté#Post-modern Bible#Process theology#progressive Christian Christianity#religious left#spiritual but not religious#spirituality#welcome church

0 notes

Text

Open and Relational Christianity

Jonathan Foster invited me on his podcast today. The audio will be released in a few weeks. For now, I’m sharing a rough transcript of our conversation.

…

Jonathan Foster

Listeners of podcasts and watchers of YouTube’s people out in the internet. Thanks so much for hanging out with us today. We are continuing what I’m calling season eight, where we’re talking about open and relational…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"'God's own life is an adventure, for the novel enjoyments that are promoted among the creatures are then the experiences providing the material for God's own enjoyment. 'The Unity of Adventure includes the Eros which is the living urge towards all possibilities, claiming the goodness of their realization.' (AI 381.) And God's life is also an adventure in the sense of being a risk, since God will feel the discord as well as the beautiful experiences involved in the finite actualizations: 'The Adventure of the Universe starts with the dream and reaps tragic Beauty.'" - John B. Cobb, Jr., David Ray Griffin; Process Theology: an Introductory Exposition

#john cobb#david ray griffin#whitehead#alfred north whitehead#process theology#process philosophy#christian#progressive christianity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 11 of Robert B. Mellert's book What Is Process Theology?

Whitehead himself was somewhat ambiguous on the subject. He does deal with death in a way that is logical and coherent in his theoretical synthesis and in a way that is open to a variety of imagery for pastoral purposes. The question of the afterlife, however, is left unresolved. For Whitehead, dying (or to use his term "perishing") is the antithesis of emerging, and each is continually occurring in every moment in every bit of reality. Only in the constant ebb and flow of emerging and perishing is change and enrichment possible. Perishing, therefore, is just as essential to the world as emerging.

In his essay on "Immortality" Whitehead says that there are two abstract worlds, the "World of Value" and the "World of Activity." Neither is explainable except in terms of the other. Value can only be explained in terms of its realization in concrete actual occasions as they emerge and perish. Thus, "value" is always experienced as "values." Values are concrete, individual and unique contributions to future actualities. The realization of a particular moment of actuality is likewise the realization of a particular value, and this becomes part of the data for the succeeding moments of actuality. Values derived from the past are thus immanently incorporated into each emerging occasion. This is what Whitehead means by "immortality." Nothing that is of value is ultimately lost. Apart from such immanent incorporation, nothing could be preserved, and "value" itself would have no ultimate meaning.

This understanding of value is exactly parallel to Whitehead’s notion of God. God, like every actual entity, is di-polar, reflecting both the mental and the physical, both the World of Value and the World of Activity. These two aspects in the divinity are, as we have seen, called God’s primordial and consequent natures, lust as God, if he is to be actual, must be really related to the world and allow it to be incorporated into himself, so also the World of Value, if it is to be more than pure abstraction, must be realized in the World of Activity. That is why value, in its concrete reality, is none other than the concrete elements of process. God embodies this in himself in his consequent nature, and offers it back to the world in each emerging occasion. To put it another way, the world adds activity to God and God adds value to the world.

The perishing of an actual occasion, therefore, need not be its extinction. Rather, it can be understood as a kind of switching of modes. Whereas in the emerging of an actual occasion God’s immanence is felt in the incorporation of value, in its perishing that actual occasion is felt immanently in God as a fuller realization of the divinity. In this way the occasion continues to be felt in the formation of the future. Death, then, is emphatically not a passing into nothingness. Instead, it is immanent incorporation into God, in whom each actuality is experienced everlastingly for its own uniqueness and individuality. In dying, one "gets out of the way" of the present in order to be available to the future in a new way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I love pretty much every episode I listen to of this podcast but this one is especially worth sharing!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

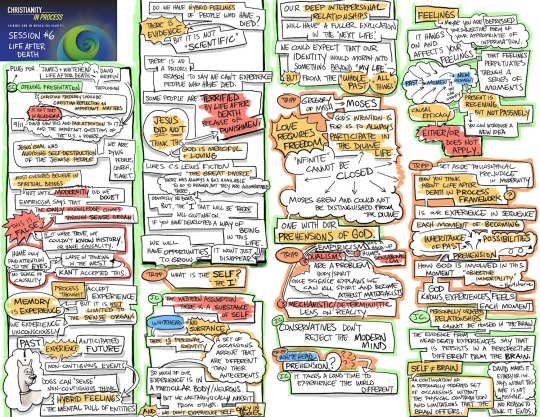

Christianity in Process with John Cobb and Tripp Fuller Session 6 Notes

Christianity in Process with John Cobb and Tripp Fuller Session 6 Notes

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” custom_padding=”2px|||||” global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”…

View On WordPress

0 notes