#nor the ins and outs of the social implications of such things

Note

Hi I don’t know if anyone has asked you this already, but do you find it strange that we are never given either of the Nie brothers’ given names nor Jin ZiXuan’s, when it’s common practice (at least in the show) to address yourself by your given and courtesy names?

Hey there! :D No, no one has asked me this yet, ahaha.

To be honest, I don’t find it strange, but that’s mostly because I think MXTX assigned names as it was convenient/as it suited her. I do think in some cases, you can try to find textual reasons, like limited POV (@hunxi-guilai made a post about how that might explain why Jiang Cheng is disproportionately referred to by birth instead of courtesy name here).

In the case of Jin Zixuan, I think that makes a lot of sense. Since mdzs and cql are largely from Wei Wuxian’s POV, and he clearly already knows Jin Zixuan, there’s no need for him to reintroduce himself, which is usually where we get people mentioning both their names. I don’t have any textual reasoning for the Nie bros’ lack of birth names ahahaha.

I will, however, use this as a springboard to mention a few things I find generally interesting about the way naming conventions appear to vary between sects/interesting points about address in general. There’s like no deep meta here, just like. “I noticed this thing, and I think it’s interesting”. (hope that’s okay /o\)

One: The Jin sect is the only sect that uses generational character markers (Guang, Zi, Ru). Establishing that convention makes Jin Guangyao’s courtesy name a massive slap in the face I think. (a, for giving him the wrong generational marker, which implies that he’s never actually going to be recognized as a son/that jgs really just didn’t care to even get it right, and b, for reusing his birth character instead of bothering to give him something new–every other character who has a birth and courtesy name gets two entirely unique names, but not jgy.) It’s a cool way of implying certain things about his status, how his father regards him without stating it outright, how others might see him because of that etc.

Two: The Wen sect appears to almost exclusively use birth name–in fact, the only two characters from the Wen sect revealed to have courtesy names are Wen Ning (Wen Qionglin) and…. Wen Ruohan. Well, and Wen Zhuliu, but he was originally Zhao Zhuliu, so idk if that really counts, since his courtesy name predates his induction into the Wen sect. Wen Qing, Wen Chao, and Wen Xu are referred to by birth name only by both themselves and everyone around them for the entirety of the story, which seems rather strange, given that all of them are high-ranking members of the family (Wen Xu is the heir??). Sizhui is not given a courtesy name by his birth family, but by Lan Wangji.

(an aside, it’s been mentioned before by others, but historically, courtesy names were bestowed upon adulthood; however, in CQL, we see Wei Wuxian picking out Jin Ling’s courtesy name before he’s born. it’s possible this is a practice that differs from sect to sect, but again, very little to no textual support for that speculation ahahaha)

Wen Ning’s courtesy name is used only once by Wei Wuxian in a moment of extreme distress at the Guanyin temple. It reads, to me, like switching registers to indicate the high emotional levels of the situation rather than anything about respect/social relations, in the same way that like, lwj switching between “wei ying/wei wuxian” can indicate moments where emotions are running high. I hc that the intimacy/distance of birth/courtesy names are switched in the case of Wen Ning/Wen Qionglin (ie, only people who are intimate with him would be expected use Qionglin) but that has absolutely zero basis in any fact, cultural convention, or textual evidence. I just like it because it warms my heart. feel free to roast me for it, i can accept that criticism.

Three: Both the Lan sect and the Nie sect address by courtesy name, even within their own family. (Lan Qiren calls his nephews “Wangji” and “Xichen”. Sizhui and Jingyi call each other by courtesy name. Nie Mingjue calls his brother “Huaisang”.) Why? we don’t know! We could maybe try and meta about it in the case of the Lan sect, I think (they’re more formal in general etc.), but we have so little knowledge of the Nie sect that I think it’s functionally pointless to try and dig there. I feel like trying to come up with any plausibly supported reason is going to be a stretch.

Four: A’Cheng vs A’Xian. Jiang Yanli uses Jiang Cheng’s birth name to form his diminutive, but uses Wei Wuxian’s courtesy name to form his. I’ve seen people ask why she doesn’t call him A’Ying, which would be more consistent, but I hc that this is because “Wuxian” was given by her father, so her using “A’Xian” is meant to strengthen that familial tie. “Ying” is from before he was part of their family. “Wuxian” is something given to him by the Jiang family, so using it, I think, is a subtle way of emphasizing how much she really considers him to be her brother. (If you’re curious, in the flashback when he first arrives at Lotus Pier, the audio drama has her calling for him as “A’Ying”.)

Five: Yu-fu’ren. I mentioned this on an addition to another post a while ago, but I’ll copy the relevant passage from chapter 51 here again:

虞夫人就是江澄的母亲,虞紫鸢。当然,也是江枫眠的夫人,当初还曾是他的同修。照理说,应该叫她江夫人,可不知道为什么,所有人一直都是叫她虞夫人。有人猜是不是虞夫人性格强势,不喜冠夫姓。对此,夫妇二人也并无异议。

Yu-fu’ren was Jiang Cheng’s mother, Yu Ziyuan. Of course, she was also Jiang Fengmian’s wife [fu’ren], and once cultivated with him as well. By all reason, she should be called Jiang-fu’ren, but for some unknown reason, everyone had always called her Yu-fu’ren. Some guessed that perhaps because Yu-fu’ren had a forceful temperament, she disliked taking her husband’s name. Neither husband nor wife raised any objections to this.

I think this is actually a pretty interesting microcosm of the themes of mdzs. We don’t actually know why Yu Ziyuan is called Yu-fu’ren; we’re given the equivalent of a rundown on local gossip and that’s it. I feel like it embodies a little bit of the “what people say about you becomes the truth and then influences your fate” theme that runs through mdzs. Did Yu Ziyuan WANT to be called Yu-fu’ren? Did she request it? Is her husband actually fine with it? The audience doesn’t get any of their internal landscape and is instead given a leading interpretation of the situation. How is our opinion of her then influenced?

To be clear, I don’t necessarily think that was necessarily the intention of this passage (maybe it was! or maybe mxtx just wanted to call her yu-fu’ren and realized she had to come up with some justification for it. i really couldn’t tell you); I just think that regardless of intention, its existence in relation to the larger themes of the novel can present a cool juxtaposition, if you dig a little bit.

Six: Song Lan, a respected cultivator, is more often referred to by his birth name, including people who are not intimate with him (normally, this would be rude), while Xiao Xingchen (who is intimate with him) calls him by courtesy name. Why?? We also don’t know. Does this lend support to my earlier headcanon about Wen Ning/Qionglin having a reversed intimacy/distance implication?? not… not really, but I like to think it at least kind of shows a precedent….. orz.

Seven: I find Xue Yang’s courtesy name, Xue Chengmei (成美), really fun ahaha. It comes from the phrase, 君子成人之美, an idiom that essentially means, “a gentleman always helps others attain their wishes”. Jin Guangyao gave it to him (not sure if this is canonical or extracanonical–i heard about it in an audio drama extra, much like how i get all my information orz) which I think is greatly amusing for obvious reasons.

Eight: Lan Wangji actually changes Sizhui’s birth name, even though you wouldn’t be able to tell just from hearing it. His original birth name is 苑, an imperial garden, but Lan Wangji changes it to 愿, as in wish (愿望) and to be willing (愿意), among other very beautiful sentiments. partially im sure to protect his identity, but also because. you know.

Basically all this is just to say, I think the naming/address conventions in mdzs are pretty weakly conceived, but you can find interesting things in them if you go looking! and we all know i love to go looking /o\

#the untamed#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#mdzs meta#the untamed meta#cql meta#mine#mymeta#wow this got long who's surprised -_-#sorry this isn't very coherent or like#well-thought out#it's just a jumbled collection of my thoughts#i didn't mean to spend too long on it but here we are#to be clear i am not an expert in chinese naming conventions#nor the ins and outs of the social implications of such things#so please take everything i say with a grain of salt#aaaahhh#Anonymous#asks and replies

828 notes

·

View notes

Text

Defending Green Book

Green Book, winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture, has had some run-ins with the press:

I want to look at some of these reviews and think pieces, talk about the arguments being made and try to defend Green Book. I’m not planning on talking about the plot or actors or any of the various scandals involving writer Nick Vallelonga. I could write a review saying that it’s funny, the music is beautiful, that it’s hammy at times but generally pretty nice and try to defend it that way, but I didn’t love Green Book - it didn’t suck, but there are other films from 2018 that had burly, surprisingly supple stories, brawny imagery, shredded performances, super jacked action, rippling jokes, rugged special effects, muscle bound implications (i.e. they were very sexy) which I would commend way more highly: Loveless, Widows, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Can You Ever Forgive Me, Burning, etc. Loveless in particular is a film I’ve thought about at least once a week since I saw it (around a year ago). Probably any of these films is more deserving of Best Picture - but I think the level of negative coverage Green Book has received is unfair and I want to try to rebut some of that.

ONE ARGUMENT: Green Book flopped because it’s not the kind of movie people want any more

While sniffing around for content, I noticed the URL for Vulture’s write up on Green Book’s box office performance refers to the film as a flop - a word which doesn’t appear anywhere in the article itself:

I checked the history of the article using the Wayback Machine and found that when the article was initially published in November 2018 it had this title:

How interesting.

By December 15 the title of the article had been edited:

The actual content of the article hasn’t changed since it was published so this is likely not the writer’s doing and is just some sneaky shit from Vulture. (The writer is Mark Harris - who, just quietly, is a pretty big deal and generally seems like a nice guy. I know it’s wrong to define people based on who they’re married to... but dude is married to Tony Kushner!!)

I imagine when the film ceased to be a flop, Vulture didn’t want to look like they were wrong. I’m not a journalist so I don’t know what standard operating procedure is in these cases, but from my time reading articles online I’ve observed that when a correction or change is made to a published article, some small text down the bottom of the page says something like “This article was originally published under the title...” or “This article originally misstated the number of fries served with...” or whatever.

Anyway - here’s what Harris had to say:

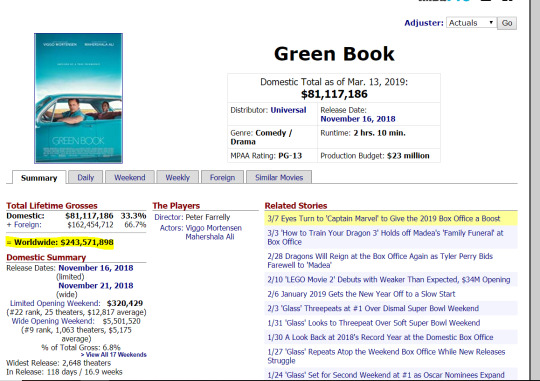

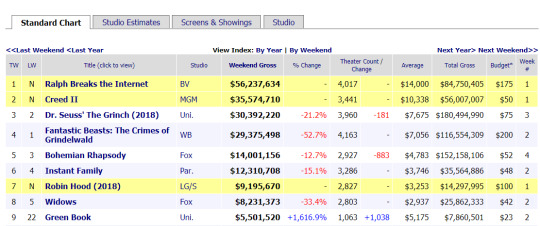

Two weeks ago, the movie arrived. The crowds did not. Following a disappointing opening on 25 screens, Green Book expanded to 1,000 for Thanksgiving weekend and finished a somewhat wan ninth. According to IndieWire box-office analyst Tom Brueggemann, its cumulative gross of under $8 million makes it “a work in progress, with a struggle ahead.” That struggle may offer a lesson that after 50 years, a particular kind of movie about black and white America has, at long last, run its course.

This is the top 9 in American cinemas for the weekend of Green Book’s wide release:

Was Green Book expected to compete with Ralph Breaks The Internet or Fantastic Beasts? Considering Green Book’s budget, I don’t think is such a bad showing. Especially considering this is the type of film which typically relies on word of mouth to generate interest - it’s a gentle human interest story. Parents will recommend it to their kids. Kids will recommend it to their grandparents. Families will watch it at home on their sectional sofas with their golden retrievers and one of those 70s wooden bowls full of kettle cooked chips. The awards and nominations may not have been expected (Farrelly’s last film was Dumb and Dumber To), but they helped generate interest as they nudged the film into prestige territory.

Besides, you can see that Green Book’s per theatre average is $5,000 which is better than Widows, Robin Hood, Instant Family and Bohemian Rhapsody. If we’re talking about flops on this weekend, Robin Hood is the obvious candidate - it opened at #7 and grossed ~$14 million internationally against a $100 million budget! Based on Harris’ logic, this is the type of film that audiences are really saying they don’t want anymore: modern takes on heroes from the Late Middle Ages (sounds kind of obvious when you put it like that).

No one should have expected Green Book to be a box office juggernaut, it’s an indie racial politics road trip movie produced by (amongst others) Participant Media - a film studio which produces work intended as ‘social impact entertainment’. That is, films creating a conversation and maybe even spurring reflection and change around current social issues. Other recent films produced by Participant Media include Roma, Spotlight, Deepwater Horizon, RBG, Beasts of No Nation, He Named Me Malala, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, and The Cove. A wide range of movies - I’m guessing the social impact element of Deepwater Horizon is that you can have too much of a good thing (when that good thing is millions of barrels of oil tumbling into the ocean, suffocating and poisoning everything it touches). Plus Deepwater is interested in OHS (Did you know BP pleaded guilty to 11 counts of manslaughter?)

Participant Media occasionally delivers surprise hits (like The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel) but produces a lot of smaller budget movies (<$30 million) which barely make their money back. Haha even Deepwater Horizon failed to break even (budget including marketing, etc. was $156 million, box office was ~$120 million). When a Participant film gets awards recognition (see: Spotlight) their investment in the film multiplies well. Looking at their 2018 films (including Roma and Green Book) this may well be their strategy moving forward. The point I’m trying to make is that not even the people who made Green Book were expecting it to be a box office hit.

In the Vulture article, Harris’ general argument is that Green Book’s ‘disappointing’ box office showing on its opening weekend indicates that America is over this type of movie. Harris states that there are two types of audience member: white and nonwhite (I’m sure there are lots of people who would take umbrage with being defined as nonwhite but Harris has a point to make about how progressive and non-racist he is so get out of his way), and that of those groups:

The portion of the white moviegoing audience that needs to be handled with this much care and flattery is getting smaller every year, and the nonwhite audience, at this point, seems justifiably wary of buying a version of someone else’s fantasy that it has been sold many, many times before...

As one person commented on the article on Vulture:

More from Harris:

There were loud critical complaints that in Three Billboards, the black characters were plot devices, abstractions designed to facilitate the growth curve of the white protagonists. That didn’t matter to Academy voters, nor will it matter to some of them that Green Book is a movie that could have been made 30 years ago. But Academy voters themselves, almost 30 percent of whom have joined only in the last four years, are changing, too, so who knows? It used to be a certainty that you’d never go broke selling white people stories of their own redemption — and that may still be true. But in 2018, it suddenly seems possible that you’ll never get rich that way either.

Should Harris disclose here that he is a white person? And isn’t a white person like Harris rejecting a trite tale of white redemption itself a tale of white redemption? Indeed, Harris’ prescient savviness to not be fooled by ‘a film which could have been made 30 years ago’ is a stirring tale of white redemption to rival Green Book itself.

(I got all raged up about the coverage of Three Billboards last year as well - you can check that out here.)

ANOTHER ARGUMENT: gReN bOOk iS JusT aN iNVerSioN oF dRivInG miSS dAiSy (and that makes it bad - obviously)

From The New Yorker:

From The Telegraph:

From sore loser Spike Lee:

Green Book, like Driving Miss Daisy before it, tells the story of a black character and a white character who forge a friendship in the face of racial hostility while behind the wheel. (In Driving Miss Daisy, the driver is black, and the rider is white; in Green Book, it’s the other way around.) “I’m snakebit,” Lee continued in the press room. “Every time somebody’s driving somebody I lose.” He paused dramatically. “But they changed the seating arrangement this time.”

(Side note: one criticism of Green Book that’s pretty solid is that the story in the film may not be as truthful as Nick Vallelonga and Farrelly insist it is. These arguments could also be made about BlacKkKlansman, so. Provided I’m not watching a documentary, I don’t care how accurate a ‘based on a true story’ film is. See also: The Favourite.)

From The New York Times:

In the above, Wesley Morris (one of the only black writers I’ve seen cover this in a major publication) makes a really strong argument for the issues with Green Book and other films from the interracial friendship genre:

Not knowing what these movies were “about” didn’t mean it wasn’t clear what they were about. They symbolize a style of American storytelling in which the wheels of interracial friendship are greased by employment, in which prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of his white, frequently racist counterpart. All the optimism of racial progress — from desegregation to integration to equality to something like true companionship — is stipulated by terms of service. Thirty years separate “Driving Miss Daisy” from these two new films, but how much time has passed, really? The bond in all three is conditionally transactional, possible only if it’s mediated by money.

(FYI, the third film he’s talking about above is The Upside.) Morris actually seems to like Driving Miss Daisy - but he is openly disgusted by Green Book:

The movie’s tagline is “based on a true friendship.” But the transactional nature of it makes the friendship seem less true than sponsored. So what does the money do, exactly? The white characters — the biological ones and somebody supposedly not black enough, like fictional Don — are lonely people in these pay-a-pal movies. The money is ostensibly for legitimate assistance, but it also seems to paper over all that’s potentially fraught about race. The relationship is entirely conscripted as service and bound by capitalism and the fantastically presumptive leap is, The money doesn’t matter because I like working for you. And if you’re the racist in the relationship: I can’t be horrible because we’re friends now.

As a plot device, I think the point of the money or the job is that IRL people from different worlds and communities just tend not to meet. That’s true now - in what other context aside from work, dating apps or maybe sports would you meet people even from a different suburb? Logistically, how do you get them in a room together? There are still real class divides in the world - I went to a very fancy private school with an indoor pool, an equestrian centre, a ‘wellbeing centre’, etc. which is based in Corio, one of the most disadvantaged suburbs in the state. Very few (no?) families in Corio could afford to send their kids to our school. I have no friends from Corio. Probably no friends from ‘working class’ families at all. I work a white collar office job so I don’t meet working class or long-term jobless people at work. I live in a gentrified inner-city suburb. What would be the set-up to get me in a room with a person from a disadvantaged background? Would I be doing volunteer work with elderly people? Serving lunch to the homeless? A school teacher at an inner city school attended by refugee children? Would I be a psychiatrist working with a bright, but angry and confused young man? (Hey, Will Hunting!)

In Green Book, our protagonist Tony Lip (Mortensen) is initially v racist, as are most of the people around him - we hear them use slurs, and we see Tony throw out glasses because black men drank from them. As Tony works for Dr. Shirley, they chat in the car - this is really the only black man he’s every had a one-on-one conversation with. Tony also observes the more extreme racism of the South. All of this undoes his prejudices. And Tony and Dr. Shirley learn from each other along the way: Tony to be a more considerate husband, more restrained in dealing with conflict, and more warm and open-minded with people who are different from those he knows - and Dr. Shirley learns to open up, have some fun rather than protecting his pride, etc. Morris is right, initially “[t]he relationship is entirely conscripted as service and bound by capitalism.” Tony took a job. Which is not a bad or unusual thing to do. Morris makes it sound sinister - ‘conscripted’, ‘bound by capitalism’. But working for someone is pretty normal - Morris himself works for The New York Times, bound by capitalism to be a critic for a great publication! It’s not so bad.

The common criticism is that Tony only changes through exposure to an exceptional black man, a piano virtuoso with a psychology degree, who is, in the film’s portrayal of him, not ‘typically’ black because he doesn’t like fried chicken or popular music. Critics argue that this microcosm doesn’t prove that Tony won’t be racist towards other black people, it doesn’t deal with larger issues of race throughout America - and worst of all, it depicts Dr. Shirley as so lost, lonely, and broken as a person that he chooses to settle for Tony, a recently and possibly only partly reformed racist, as his new best friend.

Sure! Okay! I think when people are from different races, communities, socio-economic backgrounds, etc. are put together, it’s easy for someone who studied post-colonial literature at uni to get into battle mode. But there has to be a non-offensive way to tell a story about people from different backgrounds being in a situation and getting along. Because those situations happen all the time and it’s a good thing they do. That’s why people talk about the value of diversity. And it’s not bullshit. When people who are different get together, it can work and they can learn important lessons from each other.

Morris also talks about Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing:

Closure is impossible because the blood is too bad, too historically American. Lee had conjured a social environment that’s the opposite of what “The Upside,” “Green Book,” and “Driving Miss Daisy” believe. In one of the very last scenes, after Sal’s place is destroyed, Mookie still demands to be paid. To this day, Sal’s tossing balled-up bills at Mookie, one by one, shocks me. He’s mortally offended. Mookie’s unmoved. They’re at a harsh, anti-romantic impasse. We’d all been reared on racial-reconciliation fantasies. Why can’t Mookie and Sal be friends? The answer’s too long and too raw. Sal can pay Mookie to deliver pizzas ‘til kingdom come. But he could never pay him enough to be his friend.

Maybe there’s something innately American about race relations and black history that I’ll never understand, but - is Morris arguing that black and white people in America can’t get on? Closure is impossible?

In this interview with the Associated Press, Mahershala Ali, as the only black person involved in Green Book, clearly felt pressure to defend it:

Ali grants “Green Book” is a portrait of race in America unlike one by Jenkins or Amma Asante or Ava DuVernay. But he believes the film’s uplifting approach has value.

“It’s approached in a way that’s perhaps more palatable than some of those other projects. But I think it’s a legitimate offering. Don Shirley is really complex considering it’s 1962. He’s the one in power in that car. He doesn’t have to go on that trip. I think embodied in him is somebody that we haven’t seen. That alone makes the story worthy of being told,” says Ali. “Anytime, whether it’s white writers or black writers, I can play a character with dimensionality, that’s attractive to me.”

...

“A couple of times I’ve seen ‘white savior’ comments and I don’t think that’s true. Or the ‘reverse “Driving Miss Daisy’” thing, I don’t agree with,” he says. “If you were to call this film a ‘reverse “Driving Miss Daisy,’” then you would have to reverse the history of slavery and colonialism. It would have to be all black presidents and all white slaves.”

Yet the debates over “Green Book” have put Ali in a plainly awkward position, particularly when Mortensen used the n-word at a Q&A for the film while discussing the slur’s prevalence in 1962. Mortensen quickly apologized , saying he had no right, in any context to use the word. Ali issued a statement, too, in support of Mortensen while firmly noting the word’s wrongness.

I don’t want to wade into that whole mess - but it does feel like a kind of ouroboros trap where you want to condemn a word and the people who used it but can’t say the word, so your condemnation and discussion of the word is really neutered. Like when people talk about ‘You-Know-Who’ in Harry Potter. The word still flashes through your mind.

Gah so Ali had to go on The View covering for Mortensen and explaining why we should forgive him for his just-shy-of-unforgiveable mistake so we could all still go see the film without feeling weird. What a horrible position to be in.

A lot of the coverage of Greek Book is from critics who are saying the film is regressive and offensive, that it uses black people as props, that America should be better able to handle its history by now - they don’t even hate it, they feel ick about it. And it’s so unfortunate that Ali has had to hear all of this. In various interviews, Ali has spoken about how long it took him to break out in Hollywood:

“I was exhausted by . . . I don’t want to say the lack of opportunity, but the type of opportunity,” Ali says. “I’d get offers to do two or three scenes, with a nice note from the director. But I felt like I had more to say.”

From a different article:

“Dr. Shirley was the best opportunity that had ever come my way at that point,” Ali said. “You gotta think, a year-and-a-half ago, coming off of Moonlight, which was an amazing experience, but I'm present in that movie for the first third of it. And that had sort of been my largest and most profound experience in my 25 years of working.”

“So to be presented Green Book and have Dr. Shirley, a multidimensional character who had agency, who chose...no one else was doing that in this time,” he continued. “He didn't have to hire a white driver, he chose to hire a white driver in 1962 to be in the south and have a white man opening your door and carrying your bags and for him to be in that relationship, to be the person in power, for him to be as talented and as intelligent as he was, the dignity in which he carried himself with, his own personal struggle to keep his life and things about his life private because for those things to be public, it would not have been embraced.”

Does it sound to you like Ali is trying to convince himself that it was okay to do this job?

Conscripted as service and bound by capitalism.

About a month after Morris’ article Why Do the Oscars Keep Falling for Racial Reconciliation Fantasies? was published, Green Book won the Oscar and he reflected on the film again, sounding more resigned and sad:

First, for all the changing that’s been reported about the academy’s membership — it’s getting less white and less male every year — it’s not yet entirely reflective of all that change: white and male and, at this point, capable of feeling better about a movie like “Green Book” more than, say, a movie like “Vice,” a fever dream about Dick Cheney... Peter Farrelly makes comedies and this movie, if you’re inclined to find laughs at the friendship at the film’s center, is funny. And the last line is so good and right and pleasing that I actually went for a third helping just to make sure I wasn’t wrong about it all. Only once I start thinking about what and who I’m laughing at do I get depressed...

For reference:

youtube

That is toasty warm.

As I said at the top, I don’t think Green Book is a fantastic movie - I just think it’s better than the criticism it attracted. The bulk of the criticism seemed to be mean spirited, referring obliquely to the fried chicken scene, and focussed on Peter Farrelly having a career in broad comedies and therefore not being a worthy match-up for Spike Lee, Alfonso Cuarón, etc. - plus also the obvious laughs to be had from Farrelly being forced to apologise for flopping his dick out ‘as a joke’ on the set of There’s Something About Mary (because haha his penis is so small and gross haha that’s the real joke). Hatred of Green Book has become a fun meme for Twitter.

I don’t believe Morris is writing this stuff for his own amusement, or to be contrary, or as some kind of performative wokeness. He seems very genuine - he went to see Green Book again just to check he really disliked it. He seems hurt and troubled by the movie. The best I can get to is that maybe I’m wrong for feeling optimistic and liking the kind of movie where everyone can be friends. I am very open to accepting that there is something I won’t ever really understand about racial politics in America - and if that’s the case I may not be equipped to properly defend Green Book.

(This is someone’s cue to make a movie about an Australian blogger who doesn’t think she’ll ever get American racial politics and then - on a yoga retreat in Texas, in the midst of a bird flu/zombie apocalypse, has to team up with a wheelchair-bound black politician (who was at the retreat to treat herself after a very stressful primary election). And then I the blogger becomes her driver, fleeing the flesh-hungry birds across the Texan plains, heading who knows where, but always squinting into the sun. We’ll They’ll saw the top off a Land Rover and restore a Civil War-era gattling gun to make it a death Jeep and the hair in our their armpits will grow long. It ends with us them howling like wolves and eating raw zombie birds. It will win many awards and annoy much of film twitter because the movie should have been about the black woman’s election and the blogger should have been eaten by the reanimated birds.)

#Green Book#peter farrelly#vigo mortensen#Mahershala Ali#three billboards outside ebbing missouri#mark harris#spike lee#black klansman#driving miss daisy#do the right thing#wesley morris

0 notes

Text

Actors and Spectators, Part 2: Eternally Metaphorical

I recently posted an excerpt from Shuji Terayama, leader of the theatre troupe where Seazer first worked, on the relationship between the actors and audience in terms of the self/other, suggesting that it gave some insight into the Utena’s theatre-related metaphors.

Here’s some more where he proposes that actors, too, are being used as pawns to enforce the narratives of society, having little to no control over the scenarios they are made to enact.

Earlier, he’d brought up the interesting point that marginalized people are often pushed towards “performing” or “entertaining” professions, so there’s the implication that in many cases, they are being coerced into enforcing their own oppression, which of course is a major theme in Utena.

He actually did go to a lot of effort to avoid this in his own troupe, as can be seen with his... flexible scripts, and that’s something I find really intriguing, but my main purpose here is to provide insight into the characters in Utena that are referred to symbolically as “actors”... since Utena was so heavily influenced by this kind of theatre, this is part of the context of those metaphors.

I think also that Akio’s statement that “You are either an actor or a spectator” is closely connected with the binary of Special/Chosen and Not, so you could apply this to more characters than are directly spoken of in these terms.

He does tie this all into the Self/Other analogy at the end.

Macbeth comes to a fictional Scottish castle that is actually a castle of horrible repression. In the real world, all the characters would have to discard language and become mute in order for Shakespeare's words to be distributed among them. The actors would "move according to given circumstances" and "speak the given dialogue." There would be no other way for them to live, other than to reproduce the world of the script. Macbeth may say, "Now I must enter, strike a pose, and cry," but in reality "he is made to strike a pose or cry." The true voice of the actor playing Macbeth never surfaces. In all previous drama, actors were seen merely as "slaves to the dialogue," as magical, talking wax dolls.

A Study of Capitalism and Acting

Manfred Hubricht... sometimes calls actors "emotion whores." They are forbidden their own words, but they try to speak as many of the author's as possible. They tend to be overly emotional; often, everything around them becomes soaked with the emotions that spill forth, as though they were vessels overflowing with words. Actors want to be loved by millions of people; so to earn applause, they sell fake tears and laughter for a cheap price. Therefore, they are both "emotion whores" and "applause whores." Actors sacrifice everyday reality for the satisfaction of imaginary reality. They tend to forget that, although they may have escaped being politicized, they are still chained like prisoners.

There is a wall onstage. The character inside becomes annoyed. The character is irritated, as is the actor playing him. There is a door in the wall. Although the actor's hand is a mere 20 centimeters from the doorknob--a distance that can never be shortened--this fact is an "absurdity." The actor shouts the line from the script, "Let me out of here!" But if we read the last page of the script, we see there is no stage direction for him to open the door and exit. He "will not be saved."

The whole thing is a conspiracy formulated on the author's desk, in the quiet of his study. ... The fact that a character is inside or outside the "wall" is not altered by political events or audience reaction. The character who is inside crying, "Let me out!" knows that he will never escape--not tonight or tomorrow night or closing night.

He is like a traitor with a Roman mode of thinking: "Even though I know what will happen tomorrow, I will live nonchalantly today." But if the author is alive, with a single stroke of the pen he can push him outside the wall. His escape is represented by a single stage direction reading, "Man kicks door and exits." The author has absolute power, and the staff and cast faithfully reproduce his desires. Previously, "acting" was structured as a kind of caste system, with dozens of theatre people scurrying east and west in order to serve the imagination of the king in his study. The actors were given words, like peasants who are given grain, like slaves who lived someone else's fantasy. For a long time, I've questioned the role of actors as stand-ins, or actors as puppets for the principle of empathy. It's a bad sign that the first questions we ask are "What is the actor to the audience?" and "What is the actor to the author?" We must start by first asking, "What is the actor to himself?"

Two years ago, at Tokyo University's Komaba Festival, I presented the following lecture on "The Actor."

Me: I'd like to focus on the fact that in the modern period, actors have been used almost as though they were currency. This situation primarily results from the division of labor and exchange. As Marx pointed out, "The division of labour implies from the outset the division of the prerequisites of labour, tools and materials, and thus the partitioning of accumulated capital among different owners. The social division of labor liberated us in terms of time, but it also hindered us from grasping a comprehensive understanding of the world.

Then I quoted two or three examples: how we let the dressmaker make our clothes or the cobbler make our shoes, how labor that can be a medium of exchange tends toward expansion, how these forces aided both the development of society as a commercial enterprise and multilateral exchanges between humans. Adam Smith said such divisions of labor resulted not by chance, but by conscious, rational use of language. I added that he said the motive is "self-interest" rather than "human nature." Of course, this... does not rule out the possibility that "human nature" and "self-interest" might not be in conflict.

Me: We must acknowledge that the diversity of human talent is the result, not the cause, of the division of labor (exchange). Since dogs and monkeys are incapable of exchange, they cannot unite their diverse attributes nor can they pursue the common good of society. For humans, exchange and the division of labor are continuously expanding; they are outward manifestations of value and labor-time. Money emerged as the medium of exchange, and the definition of money is not unlike the definition of the actor.

I quoted some of Marx's ideas on money from his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, including the part that states: "Money, since it has the property of purchasing everything, of appropriating objects to itself, is therefore the object par excellence. The universal character of this property corresponds to the omnipotence of money, which is regarded as an omnipotent essence... money is the pander between need and object, between human life and the means of subsistence. But that which mediates my life, mediates also the existence of other men for me. It is for me the other person..." The meaning of the entire quotation remains the same simply by replacing the word "money" with another word.

"The actor, since he has the property of transforming himself into anything, of appropriating objects to himself, is therefore the object par excellence. The universal character of this property corresponds to the omnipotence of the actor, which is regarded as an omnipotent essence... the actor is the pander between need and object, between human life and the means of subsistence. But that which mediates my life, mediates also the existence of other men for me. It is for me the other person..."

[Note: In his notes for how Heretics should be performed, Terayama quoted the same passage replacing the word money with “the script.” I just think that’s interesting.]

Me: ... In the real world, money can buy an occupation or define individuality, but money can't buy a king's title or a girl's love. However, by becoming an actor, you can play "the king" or become "the girl's fiance."

... Marx said that Shakespeare spoke most eloquently of the essential quality of money. That is natural, for Shakespeare always so both "an exchange of things for things" and "an exchange of humans for humans."

Shakespeare attributes to money two qualities:

It is the visible deity, the transformation of all human and natural qualities into their opposite, the universal confusion and inversion of things; it brings incompatibles into fraternity.

It is... the universal pander between men and nations.

This concept is essentially similar to Shakespeare's theory of actors. If the foundation of the actor's art generally results from a desire to reverse individuality, "a desire to metamorphose" or "to become something else" or to "change places in the world," then the would-be actor will transform himself into his own opposite, with his two personalities in conflict. However, we long ago abandoned the notion that human beings are valuable commodities of "exchange."

The illusion that the actor's physical body has unlimited possibilities is born when the actor's metamorphosis is confined to his external body.

That is to say, the determining factor is the belief that the physical body itself can shorten the distance between the desire "to become" and the object of desire.

Me: However, the actor is composed not only of his general social nature, but also of an alienated independence, a chaotic inner life. It is not easy to become a human stand-in, a pander for value exchange. When an actor plays a character, the confusion of role reversal deprives him of his own personality, making him nothing more than the simple reproduction of another. But putting on a crown does not make you a king--playing a role does not automatically cause an exchange of value, nor does the self cease to be the self. The question is, how can one hold onto the self while playing the king? We must find a way to insure that value is enhanced rather than exchanged.

The Performer as Magician

I have come to think of my "acting technique” as a pathway for actors, so that they can stop being the raw materials (straw dolls and human-shaped objects) that are used for casting spells, and can instead become the magicians by developing a relationship with the participants.

No longer will the actors recite "given dialogue" or represent "given gestures." Rather, they must cultivate the magical ability to create a tornado by imagination alone.

Actors will neither "be seen" nor "be exhibited," but like a tornado, they will stir things up and suck them in.

... Actors must have the power to discover a unique language. They must transcend all that has gone before, they must reject everything previously given, including "the stage," "the dialogue," "the Stanislavski method's total concentration on a role," "Brecht's concept that 'drama can re-create the world," "the border between fiction and reality"--all these "givens" must be transcended. ...

Prelude to Actor Training

I think that the actor's role is to be a "medium of contact." Like Frazer, I define the contact [of contagion] as follows: "...things which have once been in contact continue ever afterwards to act on each other."

The laws of contagion are directly analogous to the laws of the actor's communication. Therefore, I want to create a metonymic relationship between "dramatic action" and "the plague" that can be transmitted by infected actors. ...

Importing a dead rat from the outside into "an apparently simple, quiet town" is equivlent to an actor portraying a fictional role. Effective acting depends entirely on the adhesive power of contact, on the creative power of relationships. Pure technique--the ability to re-create facts, to copy or reproduce action, the power of a performer to imitate and demonstrate his insanity--by itself is nothing but an exhibition onstage. It is no better than an ecologically correct exhibition of those human beings called actors. (Of course, there is fun in "doing" this. We enjoy observing monkeys or tigers, just as we like to watch the emotional life of the actor-family of the human species in its natural habitat or ecological setting, exhibited in the cage called Shakespeare or Strindberg, as a way of alleviating boredom. In this situation, acting remains inside its cage, isolated from the everyday reality that is outside the cage.)

Dramaturgy means "making relationships." Dramatic encounters reject class consciousness and create mutually cooperative relationships, thereby organizing chance into collective consciousness.

As Sartre's protagonist says, "Hell is other people."

Even aspects of reality that seem to cut us apart from others prove that we are connected. Take the little articles in the corner of the newspaper... All these things cannot be "other people's problems." At the same time, we cannot accept everything as our own problem. Finding a way to define those circumstances that divide the self from others is what small men call politics. We create a category called "other people's problems" to "set ourselves apart." By keeping our distance, we safeguard our individual territory.

In "an apparently simple, quiet town"... the mere phrase "hell is other people's affairs" is transformed into an actuality. People become indifferent, which means they reject contact and ignore chance encounters. The clear-cut division between fiction and reality offers relative peace. The family watching TV is promised safety in exchange for watching what is guaranteed to be a fictional murder.

One day, from the outside, a dead rat is imported into this everyday reality. This is the beginning of everything. Through the power of imagination, through the chance "encounter" that is the fiction embodied in the rat, this world of fixed, inevitable forms is restored and reorgaized. A single dead rat awakens the whole town, demanding that they bid farewell to "other people's problems."

Drama is chaos. That is why actors can remove the division between the self and others, and mediate indiscriminate contact. I told the members of my drama company:

"Yes. If hell is other people's affairs, then drama is a pilgrimage of other people's hells. You must create a spectacle of fictional 'encounters' in real life, of encounters where truth and lies mingle, where self and others criss-cross. That is the pilgrimage of hells that I ask you to take."

#revolutionary girl utena#j. a. seazer#nanami kiryuu#shuji terayama#shadow play girls#akio ohtori#kyouichi saionji#touga kiryuu#his first duel song has a lot about acting#saionji kyouichi

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

Many people view the call to abolish ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, as an irresponsible act of radicalism. Republicans certainly frame it that way.

But there is nothing inevitable — or even especially long-lived — about ICE. In 2003, Congress detached different components of immigration and customs functions from the Departments of Justice and Treasury to form ICE. Its new home in Department of Homeland Security dictated an institutional posture that all immigration to the United States posed a threat. That reorganization — including the startling proposition that supports it — is at least as radical as its unwinding would be.

Left unchecked, the egregious harms imposed by ICE — deportations that do more to disrupt than protect American communities; the ill-conceived preference for immigration detention executed via a system that is a human rights disgrace — will resolve into a “new normal.”

That is the fate of recent conservative state-building in the United States: Policies and offices do not survive scrutiny so much as simply evade it.

I can say this with confidence because five years ago, I published a book examining the history of the worst policy failure in modern US history: the government’s war on drugs. In light of drug prohibition’s abysmal results, I made several recommendations, including abolishing the Drug Enforcement Administration, the architect and emblem of the government’s war on drugs.

I did so not because I think illicit drugs present trivial dangers, but because I know they carry very real and distressing ones. When evaluated on the basis of its own selected benchmarks, the drug war has driven key performance indicators like illicit drug price and potency in exactly the wrong direction.

But conservative state-building is never judged on the basis of results — a simple point that bears closer inspection. Take, for example, the remarkably similar history and trajectory of ICE and the DEA. Like ICE, the DEA was formed by combining two offices — one from the White House, and one from the Treasury Department. Typically, executive departments are organized around a particular policy portfolio (like education), and they focus on overarching goals, weighing various tools and approaches to meet those goals.

Whether those tools work to advance an agency’s valued objective is a question that the officials in and out of the organization attempt to answer. If found wanting, tools can be modified or abandoned — unless they happen to belong to units dedicated overwhelmingly to enforcement, tucked into executive departments that dramatically misconceptualize the target of their intentions. In that case, no meaningful evaluation takes place at all.

The US government once construed drugs as a trade. The Bureau of Narcotics (the main predecessor agency to the DEA), seated in the Department of Treasury, was armed with sanctions that could diminish the flow of illicit drugs. The formation of the DEA crystallized a very different notion —namely, that illicit drugs were a crime.

In an analogous fashion, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) once sat in the Department of Labor, on the supposition that people came to this country seeking work; it later moved to the Department of Justice. Before the creation of ICE, as the Atlantic’s Franklin Foer points out, “enforcement was housed in an agency devoted to both deportation and naturalization.”

Today these functions belong to an agency predicated on thwarting terrorist threats, and the instruments it deploys have not been shown to deter illegal immigration, nor do terrorist threats concentrate in the migrant communities most subjected to its punitive measures.

Tasked with Sisyphean chores and supplied with counterproductive tools, it is not surprising that the DEA and ICE share some dysfunctions. Their leadership rejects meaningful distinctions — whether between drugs, or between and among undocumented migrants — because drawing them would raise real questions about the implicit premise that resides in their institutional location. The workforce of both ICE and the DEA features agents who harbor a siege mentality, fostered by a culture of secrecy and resentment of oversight, and susceptible to corruption.

Neither is overseen by an official who must weigh the effectiveness, and decide the budget, of enforcement relative to a different approach to the same problem. Both are capable of moderating only the degree of the application of punitive enforcement, and incentivized in the direction of ever-greater amounts. To think differently, to drop one set of tools in favor of another, would amount to an act of institutional self-repudiation.

No matter how many indictments and interdiction efforts the DEA claims as a success, it has no measurable impact on the drugs wending their way through black markets. Inspecting the record, it’s surprising that these misplaced enforcement agencies command much approval at all.

A heroin user. Pictures Ltd./Corbis/Getty Images

That brings us to the second simple but crucial observation regarding conservative state-building: Agencies like the DEA do not draw political strength from defenders so much as they do from a kind of aggressive complacency — a Beltway mindset that treats change as an antagonist.

Unless faced with a committed opposition, an agency like the DEA will easily defeat critics, not because its proponents will mount superior arguments, but because those proponents won’t feel compelled to make any arguments at all. One of the most astonishing things about the DEA’s pervasive, passive support is the way in which policy discussions deemed “serious” omit drug prohibition from the very problems it is most implicated in.

Examinations of the falling rate by which US law enforcement makes an arrest in cases of homicide is one example of this “motivated” silence. Once more than 90 percent, the so-called “clearance rate” for homicides now holds steady at roughly 65 percent; in some places, like Chicago, the clearance rate for homicide in 2017 came in at 17.5 percent.

The reason for this collapse is well known: Other than forensic evidence, witness testimony remains the crucial factor in building a case against a suspect. But in the same neighborhoods that experience the most murders, witnesses have gone silent, unable or unwilling to confide in members of a police force viewed as adversaries.

Rather than consider why the police mission has been discredited in the places where it is most needed, we typically lament “community mistrust,” on the apparent belief that ordinary people have invented some suspicion that was too convenient to resist, too hard to dispel, yet without reason or rationale.

That’s simply not the case: As I discuss in my book, residents of urban black neighborhoods that had long gone unpoliced were first able to regard themselves as clients, not just targets, of law enforcement services in the 1950s. Yet this newfound status of “citizens worthy of service provision” was heavily conditioned by different agendas of social control: Arrests for loitering and public drunkenness were common, for instance.

Among the various police tactics of subjugation, by the 1970s, only the drug war toolkit survived challenges of civil rights jurisprudence and police professionalization. It nurtured a mode of policing that offended onlookers and alienated potential allies.

When combined with the profits made available to criminal gangs via drug prohibition — a policy enshrined in the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 — our drug war has produced a toxic combination: entrenched networks of crime sustained by gun violence, and a legacy of community suspicion of police. Yet we treat both phenomena as ex nihilo, sprung from nothing and out of nowhere.

Other conversations bear the imprint of a failed drug war, though we inspect the tracks as if laid by the mysterious Bigfoot. Drug prohibition drives but is inexplicably absent from analyses of the mounting lethality of the opioid crisis. Few who chide illicit opioid manufacturers for overprescribing opioids recall that a century ago, heroin was among the pain medications they sold.

As reports of misuse mounted, legislators responded by declaring heroin contraband, surrendering the drug to underground production and forfeiting the ability to regulate it in any way. The result is a drug many times more dangerous than its original formulation; with the recent addition of chemical synthetics like fentanyl, illicit heroin now regularly kills its consumers.

The drug war, a creature of our own creation, stalks us with its perverse consequences; still, we report being mugged by a stranger.

To be clear, illicit drug trafficking is now a fact of global trade, not a genie we can put back in the bottle. But to be equally clear, our refusal to acknowledge the drug war’s ever-present failure, including our refusal to consider abolishing the DEA, impoverishes analysis and blinds us to possible alternatives. Instead of trying to arrest and interdict our way out of the program, for instance, we might follow the advice of Sen. Rob Portman, who represents the heavily opioid-afflicted state Ohio, and prioritize the illicit production of fentanyl in trade talks with China.

Worse yet — and similar to a punitive approach to immigration enforcement — in perpetuating meaningless enforcement, we pathologize poverty, criminalize and imprison difference, perpetuate institutional racism, and degrade legal practices long considered essential to our freedom. We cheat ourselves of honest and productive relations with other countries, especially those in Central and South America.

Claiming the right to name and discuss these failures, and confronting conservative state-building of any sort, involves seeing the past in our present; it means grounding our analysis in the problem as it exists, rather than in the terms in which it is typically couched; it demands acknowledging something other than the white experience.

It has never been more important to enrich our perspective in precisely these ways. Typically institutions like the DEA and ICE loiter, like uninvited guests, at the margins of public discussion. Our post-9/11 world makes this neglect untenable. A war on terror, like the one waged against drugs, is both a mindset and a massive proliferation of enforcement policy and institutions — effectively a New Deal for the carceral and surveillance state.

Progressive approaches to recurring problems like terrorism, drugs, or illegal immigration do not suffer from poor evidence; they struggle for narrative context. Our political establishment caricatures progressive designs as extreme even when cautious: It appraises them as costly despite material savings; it judges them according to any failure, no matter how infrequent, unrelated, or trivial; it marginalizes these ideas as eccentric and irrelevant.

The opposite assumptions frame an approach of the “gun and the badge” (my phrase to denote enforcement-centric policy solutions): always treated as reasonable regardless of how radical; absolved of all sins, no matter the gravity or number; and received by serious people as indispensable and efficient, even when ineffective and expensive.

In this light, the call to “abolish ICE” has a place among efforts to expose other kinds of double standards in our world. It may well rank as among the most difficult. A progressive institutional and policy agenda is the ultimate outsider, a perpetual interloper who must do twice the work to garner half the credit. Meanwhile, the “gun and the badge” proves nothing to no one yet is accorded great deference.

And so, in league with other politics intended to challenge privilege, I say again: Abolish the DEA, and abolish ICE. Any redeeming aspect of their respective agencies can be transferred to a place where enforcement must demonstrate its effectiveness when judged against other approaches, operate under an appropriate executive mission, and show a return on investment based on outcomes that improve the lives of ordinary Americans.

Kathleen Frydl has examined conservative state-building in an award-winning book on the GI bill; a book on the drug war; and in articles on the FBI as well as the care of foundlings. Find her on Twitter @kfrydl.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart discussion of the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

Original Source -> Why we should abolish ICE — and the DEA too

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes